1. INTRODUCTION

Channelization of subglacial meltwater is well documented from the sedimentary and geomorphological record (e.g., Piotrowski, Reference Piotrowski1999; Piotrowski and others, Reference Piotrowski, Geletneky and Vater1999; Jørgensen and Sandersen, Reference Jørgensen and Sandersen2006; Greenwood and others, Reference Greenwood, Clason, Nyberg, Jakobsson and Holmlund2016; Bjarnadóttir and others, Reference Bjarnadóttir, Winsborrow and Andreassen2017; Simkins and others, Reference Simkins2017). Several geophysical investigations support that channelization of subglacial meltwater is an important process under contemporary glaciers and ice sheets (e.g., Hubbard and Nienow, Reference Hubbard and Nienow1997; Winberry and others, Reference Winberry, Anandakrishnan and Alley2009; Horgan and others, Reference Horgan2013; Le Brocq and others, Reference Le Brocq2013; Schroeder and others, Reference Schroeder, Blankenship and Young2013; Gimbert and others, Reference Gimbert, Tsai, Amundson, Bartholomaus and Walter2016; Drews and others, Reference Drews2017). Numerical models of Antarctic ice-stream flow have shown that channelized water flow is necessary for producing sufficient variations in water pressure and subglacial friction, to match observed variations in ice-surface velocity (e.g., Thompson and others, Reference Thompson, Simons and Tsai2014; Rosier and others, Reference Rosier, Gudmundsson and Green2015), and meltwater channelization appears to be necessary for stabilizing ice-stream shear margins (Suckale and others, Reference Suckale, Platt, Perol and Rice2014; Perol and Rice, Reference Perol and Rice2015; Perol and others, Reference Perol, Rice, Platt and Suckale2015; Elsworth and Suckale, Reference Elsworth and Suckale2016). Channelized meltwater flow is especially important for water and ice dynamics during subglacial lake drainage events (e.g., Bartholomew and others, Reference Bartholomew2010; Stevens and others, Reference Stevens2015; Brinkerhoff and others, Reference Brinkerhoff, Meyer, Bueler, Truffer and Bartholomaus2016; Dow and others, Reference Dow, Werder, Nowicki and Walker2016; Fricker and others, Reference Fricker, Siegfried, Carter and Scambos2016; Carter and others, Reference Carter, Fricker and Siegfried2017; Simkins and others, Reference Simkins2017). Recent studies have detailed that the influence of channel dynamics extends downstream of the grounding line, since point release of water through channels at grounding lines greatly enhances basal melt rates through the formation of turbulent buoyant plumes (e.g., Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2011; Xu and others, Reference Xu, Rignot, Menemenlis and Koppes2012; Le Brocq and others, Reference Le Brocq2013; Marsh and others, Reference Marsh2016; Alley and others, Reference Alley, Scambos, Siegfried and Fricker2016; Drews and others, Reference Drews2017).

Channelization is not only relevant for projecting ice fluxes, but also for understanding subglacial landforms as water flow in the channels may be a primary mechanism for eroding and delivering sediment from the ice-sheet or glacier interior to its margin (e.g., Swift and others, Reference Swift, Nienow, Spedding and Hoey2002; Alley and others, Reference Alley, Lawson, Larson, Evenson and Baker2003; Kehew and others, Reference Kehew, Piotrowski and Jørgensen2012; Bjarnadóttir and others, Reference Bjarnadóttir, Winsborrow and Andreassen2017). Recent discoveries of curvilinear and erosive landforms near the last-glacial maximum terminus (Fig. 1) have raised questions on how subglacial drainage systems arrange on soft beds (Lesemann and others, Reference Lesemann, Piotrowski and Wysota2010, Reference Lesemann, Piotrowski and Wysota2014).

Fig. 1. Glacial curvilineations incised into sedimentary plateaus by subglacial meltwater erosion during the last glaciation near Zbójno, Poland, from Lesemann and others (Reference Lesemann, Piotrowski and Wysota2010). Water and ice-sheet flow was generally from the top left (NW) to the lower right (SE).

Glacier beds provide resistive friction to glaciers and ice sheets and limit how fast they flow, and are typically subdivided into hard (rigid and impermeable) or soft (deformable and typically sedimentary) types. The amount of resistance provided by the bed is strongly dependent on subglacial water pressure (e.g., Weertman, Reference Weertman1957; Lliboutry, Reference Lliboutry1968; Budd and others, Reference Budd, Keage and Blundy1979; Iken, Reference Iken1981; Bindschadler, Reference Bindschadler1983; Boulton and Hindmarsh, Reference Boulton and Hindmarsh1987; Fowler, Reference Fowler1987; Kamb, Reference Kamb1991; Hooke and others, Reference Hooke, Hanson, Iverson, Jansson and Fischer1997), and subglacial channels are the most efficient drainage type and water-pressure altering component at the ice–bed interface (e.g., Flowers, Reference Flowers2015). Meltwater evacuation through channels generally decreases pore-water pressure and increases basal strength in the adjacent areas under the ice (e.g., Shoemaker, Reference Shoemaker1986; Boulton and Hindmarsh, Reference Boulton and Hindmarsh1987; Rempel, Reference Rempel2009). Since changes in subglacial water-flow patterns directly affect the glacier stress balance, changes in subglacial hydrology can cause large-scale rearrangement in the flow patterns of ice sheets (e.g., Raymond, Reference Raymond2000; Tulaczyk and others, Reference Tulaczyk, Kamb and Engelhardt2000a,Reference Tulaczyk, Kamb and Engelhardtb; Boulton and others, Reference Boulton, Hagdorn, Maillot and Zatsepin2009; Piotrowski and others, Reference Piotrowski, Hermanowski and Piechota2009; Bougamont and others, Reference Bougamont2015; Elsworth and Suckale, Reference Elsworth and Suckale2016).

The importance of changes in subglacial hydrology on ice flow has sparked efforts to develop and improve mathematical descriptions of subglacial water-pressure evolution in ice-flow models (e.g., Bougamont and others, Reference Bougamont, Price, Christoffersen and Payne2011; van der Wel and others, Reference van der Wel, Christoffersen and Bougamont2013; Werder and others, Reference Werder, Hewitt, Schoof and Flowers2013; de Fleurian and others, Reference de Fleurian2014; Kyrke-Smith and others, Reference Kyrke-Smith, Katz and Fowler2015). Building on the pioneering work of Röthlisberger (Reference Röthlisberger1972), Shreve (Reference Shreve1972), and Nye (Reference Nye1976), which established the mathematical framework of dynamic water flow through channels melted into basal ice (R-channels), recent studies have improved our understanding of subglacial water drainage as a coupled system on hard beds. Differences in drainage properties between distributed and discrete drainage modes hint towards a complex interplay during non-steady drainage (e.g., Schoof, Reference Schoof2010; Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2011, Reference Hewitt2013; Kingslake and Ng, Reference Kingslake and Ng2013; Werder and others, Reference Werder, Hewitt, Schoof and Flowers2013). Schoof (Reference Schoof2010) and Hewitt (Reference Hewitt2013) demonstrated that variability in meltwater input has the potential to cause ice-flow acceleration, because transient increases in meltwater supply overwhelm the water-transport capacity of the subglacial hydrological system. However, the majority of ice in contemporary and past ice sheets moves over soft beds (e.g., Alley and others, Reference Alley, Blankenship, Bentley and Rooney1986; Engelhardt and others, Reference Engelhardt, Humphrey, Kamb and Fahnestock1990; Anandakrishnan and others, Reference Anandakrishnan, Blankenship, Alley and Stoffa1998; Tulaczyk and others, Reference Tulaczyk, Kamb and Engelhardt2000a; Kamb, Reference Kamb2001; Stokes and Clark, Reference Stokes and Clark2001; Piotrowski and others, Reference Piotrowski, Larsen and Junge2004; King and others, Reference King, Hindmarsh and Stokes2009; Christianson and others, Reference Christianson2014; Greenwood and others, Reference Greenwood, Clason, Nyberg, Jakobsson and Holmlund2016; Bjarnadóttir and others, Reference Bjarnadóttir, Winsborrow and Andreassen2017; Kulessa and others, Reference Kulessa2017; Simkins and others, Reference Simkins2017), but soft-bed channelized drainage is not included in current ice-sheet models despite efforts to parameterize the governing characteristics.

At present, our understanding of soft-bed hydrological processes is limited. Shoemaker (Reference Shoemaker1986) presented the first mathematical analysis of subglacial hydrology and sediment stability for a soft-bedded ice sheet drained by a combination of porous (groundwater) flow and channelized drainage. He assumed that erosion of sediment at the channel floor would incise channels into the soft bed, but argued that the increase in effective stress on the channel flanks would increase sediment strength sufficiently to make channels stable at any size.

Alley (Reference Alley1992) investigated the mechanical stability of a simplified channel geometry, and applied analytical relationships for till mechanics, including perfect plasticity and Bingham rheology, in part based on parameter fits by Boulton and Hindmarsh (Reference Boulton and Hindmarsh1987). While offering convenience by uniquely linking stress and strain in mathematical models, the weakly non-linear viscous till rheologies proposed by Boulton and Hindmarsh (Reference Boulton and Hindmarsh1987) disagree with the nearly plastic sediment rheology known from fundamental granular and soil mechanics (e.g., Schofield and Wroth, Reference Schofield and Wroth1968; Nedderman, Reference Nedderman1992; Terzaghi and others, Reference Terzaghi, Peck and Mesri1996; Mitchell and Soga, Reference Mitchell and Soga2005), field measurements on subglacial till deformation (e.g., Hooke and others, Reference Hooke, Hanson, Iverson, Jansson and Fischer1997; Kavanaugh and Clarke, Reference Kavanaugh and Clarke2006), laboratory deformation experiments on till (e.g., Kamb, Reference Kamb1991; Iverson and others, Reference Iverson, Hooyer and Baker1998; Tulaczyk and others, Reference Tulaczyk, Kamb and Engelhardt2000a; Iverson and others, Reference Iverson2007), inversion of subglacial mechanics from ice-surface velocities (e.g., Tulaczyk, Reference Tulaczyk2006; Walker and others, Reference Walker, Christianson, Parizek, Anandakrishnan and Alley2012; Goldberg and others, Reference Goldberg, Schoof and Sergienko2014; Minchew and others, Reference Minchew2016; Gillet-Chaulet and others, Reference Gillet-Chaulet2016), and numerical experiments (e.g., Iverson and Iverson, Reference Iverson and Iverson2001; Kavanaugh and Clarke, Reference Kavanaugh and Clarke2006; Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2013, Reference Damsgaard2016).

Walder and Fowler (Reference Walder and Fowler1994) combined an earlier mathematical formulation of R-channel closure (Nye, Reference Nye1976) with the mildly non-linear viscous closure relationship for conduits in till (Boulton and Hindmarsh, Reference Boulton and Hindmarsh1987; Fowler and Walder, Reference Fowler and Walder1993) and derived a new mathematical model for subglacial channels in soft beds. Contrary to the Bingham visco-plastic relationship applied by Alley (Reference Alley1992), Walder and Fowler (Reference Walder and Fowler1994) ignored sediment yield strength and parameterized till to continuously creep toward the channel and counteract fluvial erosion. In their mathematical framework, they demonstrated that the type of channelized drainage is a function of surface slope. R-channels are likely to form under steep-sloped mountain glaciers, while fluvial incision into the soft bed is hypothesized dominate under relatively flat parts of ice sheets. Ng (Reference Ng2000a) further developed the mathematical theory by Walder and Fowler (Reference Walder and Fowler1994), and demonstrated that sediment erosion and deposition by fluvial transport is more important than creep closure of the idealized viscous sediment. A similar model, also with viscous till rheology and fluvial channel incision into soft beds, was shown to effectively approximate drainage histories of Antarctic subglacial lakes better than a R-channel model with erosion into the ice base (Carter and others, Reference Carter, Fricker and Siegfried2017).

However, the models assuming viscous till rheology provide a continuous flux of sediment towards the channel, and disregard sediment yield strength and associated plastic failure limits. Yet, subglacial till is known to behave like other clastic sediments with a nearly perfect plastic and rate-independent rheology with a yield strength τ y governed by the Mohr–Coulomb constitutive relation, τ y = C + N tan(ϕ u), where C is the effective sediment cohesion, N is the effective stress normal to the shear plane, and ϕ u is the angle of internal friction (e.g., Terzaghi, Reference Terzaghi1943). As a matter of fact, the plastic behavior of sediment beds in general, with or without cohesive forces, is related to the general behavior of granular material (e.g., GDR-MiDi, 2004; Houssais and others, Reference Houssais, Ortiz, Durian and Jerolmack2015; Houssais and Jerolmack, Reference Houssais and Jerolmack2017). In this study, we use numerical simulations of purely granular material (without cohesion) to move one step further in understanding the impact of sediment bed plasticity on the subglacial channel shape dynamics and the subglacial hydrology. In particular, we will study the effect of the effective normal stress at the ice–bed interface, and investigate how strong horizontal pore-pressure gradients toward the channel impact the shape and stability of the channel.

In the next section, we present the physical background of subglacial channel modeling, the simulation method we used, and how simulations of granular material were initialized and performed. Afterwards we present and discuss our results and combine our findings with established approaches for sediment and water in a new continuum formulation for subglacial soft-bed channels.

2. BACKGROUND AND METHODS

2.1. Continuum modeling of subglacial channels

Mathematical models of subglacial hydrology contain several balance equations, related to conservation of water mass, transients in hydraulic properties related to conduit opening and closure, and conservation of water momentum and energy (e.g., Nye, Reference Nye1976; Walder and Fowler, Reference Walder and Fowler1994; Clarke, Reference Clarke2005; Schoof, Reference Schoof2010; Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2011; Kingslake and Ng, Reference Kingslake and Ng2013; Werder and others, Reference Werder, Hewitt, Schoof and Flowers2013; Flowers, Reference Flowers2015). The cross-sectional size of a soft-bed subglacial channel evolves by the combined effect of melting and creep closure of the channel roof, and fluvial sediment erosion and deposition at the channel base. Here, we assume that the channel is governed by sediment flux alone, implying that the ice interface remains planar. Simultaneous incision of both the ice roof and sedimentary bed, may occur under more energetic conditions (e.g., Alley, Reference Alley1989; Walder and Fowler, Reference Walder and Fowler1994; Carter and others, Reference Carter, Fricker and Siegfried2017). Changes in the channel cross-sectional area over time ∂S/∂t are balanced by the along-channel gradient of fluvial sediment flux Q s through the Exner equation with a representative bed porosity Φ (e.g., Ng, Reference Ng2000a):

where s is the channel streamwise dimension. Significant effort has been devoted to constraining the relationships behind sediment transport in fluvial settings, and this is an ongoing topic of research (e.g., Lajeunesse and others, Reference Lajeunesse, Malverti and Charru2010). As a result there are numerous propositions for parameterizing the sediment transport, Q s (e.g., Shields, Reference Shields1936; Meyer-Peter and Müller, Reference Meyer-Peter and Müller1948; Einstein, Reference Einstein1950; Parker, Reference Parker1978; Stock and Montgomery, Reference Stock and Montgomery1999; Whipple and Tucker, Reference Whipple and Tucker1999; Ng, Reference Ng2000a; Davy and Lague, Reference Davy and Lague2009; Lajeunesse and others, Reference Lajeunesse, Malverti and Charru2010). The commonly used empirical relationships for sediment transport are a function of the shear stress generated by fluid flow near the bed, τ, generally reported as the dimensionless Shields number, τ* = τ/[(ρ g − ρ w)gD] where ρ g, ρ w , g, and D are the particle density, fluid density, gravity, and particle diameter, respectively. The onset of sediment transport is classically associated with a critical Shields number, τ*c, that is required to overcome grain friction (Shields, Reference Shields1936). Meyer-Peter and Müller (Reference Meyer-Peter and Müller1948) is a well-supported sediment transport relationship describing bed-load transport in a turbulent flow:

$$ Q_{\rm s} = 8 \max \lpar 0\comma \tau^{\ast} - \tau_{\rm c}^{\ast} \rpar ^{3/2} W \sqrt{{\rho_{\rm g} - \rho_{\rm w} \over \rho_{\rm w}}gD^3} $$

$$ Q_{\rm s} = 8 \max \lpar 0\comma \tau^{\ast} - \tau_{\rm c}^{\ast} \rpar ^{3/2} W \sqrt{{\rho_{\rm g} - \rho_{\rm w} \over \rho_{\rm w}}gD^3} $$

where W is the channel width. Importantly, τ*c is highly material dependent, and, in particular, increases as particle sizes become small enough that cohesion forces become significant. We note that the sediment–flux relationship presented above may fall short for very clay-rich or multimodal beds (e.g., Wilcock, Reference Wilcock1998; Houssais and Lajeunesse, Reference Houssais and Lajeunesse2012). The fluid shear stress τ along the hydraulic perimeter can be inferred through the Darcy–Weisbach formula (e.g., Henderson, Reference Henderson1966; Walder and Fowler, Reference Walder and Fowler1994; Ng, Reference Ng2000a; Creyts and Clarke, Reference Creyts and Clarke2010; Carter and others, Reference Carter, Fricker and Siegfried2017),

![]() $\tau = 0.125 f^{\prime} \rho _{\rm w} \left(QS^{-1} \right)^2$

, where f′ is a dimensionless friction factor.

$\tau = 0.125 f^{\prime} \rho _{\rm w} \left(QS^{-1} \right)^2$

, where f′ is a dimensionless friction factor.

As for hard-bed channel models the water flux Q along the channel length axis s can be described by a turbulent flow law (Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2011):

$$ Q = \sqrt{F^{-1} S^{8/3} \left(\psi - {\partial P_{\rm c} \over \partial s}\right)}\comma $$

$$ Q = \sqrt{F^{-1} S^{8/3} \left(\psi - {\partial P_{\rm c} \over \partial s}\right)}\comma $$

where P c is the averaged effective pressure in the channel, and ψ is the topographically constrained pressure gradient:

Here, b is the bed topography and H is the ice thickness (e.g., Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2011), and F is a function of conduit geometry and the Manning friction coefficient n′: F = ρ w gn′[2(π + 2)2/π]2/3. The water-flow law (Eqn 3) is typically rearranged to solve for along-channel change in effective pressure P c (e.g., Ng, Reference Ng2000b; Kingslake and Ng, Reference Kingslake and Ng2013; Carter and others, Reference Carter, Fricker and Siegfried2017):

The water flux Q in the above equation is usually found from an equation of water conservation, often by assuming water incompressibility, negligible change in water storage along the flow path, and negligible sediment fluxes relative to the water discharge. The change in water flux downstream is given by a local source term,

![]() ${\dot m}$

(e.g., Schoof, Reference Schoof2010):

${\dot m}$

(e.g., Schoof, Reference Schoof2010):

The source term

![]() ${\dot m}$

can be comprised several contributions, including influx from the surrounding bed through groundwater seepage, inflow along the ice–bed interface, and input from englacial storage. In the following, we apply a numerical model of granular deformation to explore the conditional sediment stability a channel, and tweak the above formulation for channel size (Eqn 1) to capture the essential behavior associated with Mohr–Coulomb plasticity of the subglacial sediment.

${\dot m}$

can be comprised several contributions, including influx from the surrounding bed through groundwater seepage, inflow along the ice–bed interface, and input from englacial storage. In the following, we apply a numerical model of granular deformation to explore the conditional sediment stability a channel, and tweak the above formulation for channel size (Eqn 1) to capture the essential behavior associated with Mohr–Coulomb plasticity of the subglacial sediment.

2.2. Grain-scale sediment modeling

2.2.1. Model description

We use a discrete element method (DEM, e.g. Cundall and Strack, Reference Cundall and Strack1979; Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2013) in order to resolve the sediment mechanics in the bed surrounding an idealized subglacial channel. The DEM is a Lagrangian-type numerical approach of multi-body classical mechanics. Newton's Second Law of motion is explicitly integrated to find translational and rotational acceleration, velocity, and position for each grain through time. For a grain i in contact with j∈N other grains, the sum of forces consists of gravitational pull ( f g), grain-to-grain elastic-frictional contact forces ( f n and f t), and the fluid-pressure force ( f f),

$$ {\partial^2 {\bf x}^i \over \partial t^2} m^i = {\bi f}_{\rm g}^i + \sum_{\,j \in N} \left({\bi f}_{\rm n}^{i\comma j} + {\bi f}_{{\rm t}}^{i\comma j} \right)+ {\bi f}_{{\rm f}}^i\comma $$

$$ {\partial^2 {\bf x}^i \over \partial t^2} m^i = {\bi f}_{\rm g}^i + \sum_{\,j \in N} \left({\bi f}_{\rm n}^{i\comma j} + {\bi f}_{{\rm t}}^{i\comma j} \right)+ {\bi f}_{{\rm f}}^i\comma $$

where x is the grain center position, m is the grain mass, and t is the time. A similar equation conserves angular momentum:

$$ {\partial^2 {\bf \Omega}^i\over \partial t^2} I^i = \sum_{\,j \in N} \left(-\left(r^i {\bi n}^{i\comma j} \times \ {\bi f}_{\rm t}^{i\comma j} \right)\right)$$

$$ {\partial^2 {\bf \Omega}^i\over \partial t^2} I^i = \sum_{\,j \in N} \left(-\left(r^i {\bi n}^{i\comma j} \times \ {\bi f}_{\rm t}^{i\comma j} \right)\right)$$

where n is the grain-contact normal vector, Ω is the angular particle position, and I is the grain rotational inertia.

The forces from grain interactions ( f n and f t) are determined by a Hookean (linear elastic) rheology. The contact-normal interaction force is found from the contact-normal component of the inter-grain overlap distance vector δ :

The tangential (contact-parallel) interaction force is similarly found from the contact-tangential component of the overlap distance vector, but is in magnitude limited by the Coulomb frictional coefficient μ:

$$ {\bi f}_{\rm t}^{ij} = - \min \left[k_{\rm t} {\bi \delta}_{\rm t}^{i\comma j}\comma \,\,\mu \Vert {\bi f}_{\rm n}^{i\comma j}\Vert \right]{{\bi \delta}_{\rm t}^{i\comma j}\over \Vert {\bi \delta}_{\rm t}^{i\comma j}\Vert }. $$

$$ {\bi f}_{\rm t}^{ij} = - \min \left[k_{\rm t} {\bi \delta}_{\rm t}^{i\comma j}\comma \,\,\mu \Vert {\bi f}_{\rm n}^{i\comma j}\Vert \right]{{\bi \delta}_{\rm t}^{i\comma j}\over \Vert {\bi \delta}_{\rm t}^{i\comma j}\Vert }. $$

The contact-normal and tangential travel vectors ( δ n and δ t) are incrementally adjusted over the duration of a grain-to-grain interaction, and continuously corrected in the case of contact rotation. If Coulomb failure occurs at the contact, the tangential travel is readjusted to correspond to a length consistent with Coulomb's condition (|| δ t|| = μ|| f n||k −1 t, e.g. Luding, Reference Luding2008; Radjaï and Dubois, Reference Radjaï and Dubois2011). The contact stiffnesses for the elastic interactions (k n and k t) are, contrary to our previous study using this model (e.g., Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2015), determined by scaling against a macroscopic elasticity:

where E is the Young's modulus, and r i and r j are the radii of two interacting grains. This approach makes the bulk elastoplastic behavior independent of the chosen grain size (Ergenzinger and others, Reference Ergenzinger, Seifried and Eberhard2011; Obermayr and others, Reference Obermayr, Dressler, Vrettos and Eberhard2013).

The fluid-pressure force on each grain is determined by the local gradient of the water-pressure field (p f), as well as buoyant uplift from the weight of displaced fluid (Goren and others, Reference Goren, Aharonov, Sparks and Toussaint2011; Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2015):

where V is the grain volume, ρ f is the fluid density, and g is the gravitational acceleration vector. We ignore other and weaker fluid-interaction forces (Stokes drag, Saffman force, Magnus force, virtual mass force) (e.g., Zhu and others, Reference Zhu, Zhou, Yang and Yu2007; Zhou and others, Reference Zhou, Kuang, Chu and Yu2010), which become important with faster fluid flow and associated larger Reynolds numbers.

Once the sum of forces (right-hand side of Eqn 7) and torques (right-hand side of Eqn 8) have been determined, we perform explicit and third-order temporal integrations with Taylor expansions in order to determine the new kinematic state (e.g., Kruggel-Emden and others, Reference Kruggel-Emden, Sturm, Wirtz and Scherer2008). The maximum admissible time step is tied to the propagation of seismic (elastic) waves through the granular assemblage, and is determined by the density, size, and elastic stiffnesses in the granular system (e.g., Radjaï and Dubois, Reference Radjaï and Dubois2011):

with a constant safety factor (ε = 0.07).

2.2.2. Meltwater in sediment and channel

We describe pore-water pressure in the sediment by a time-dependent diffusion equation with a forcing term related to porosity change. The rate of pressure diffusion scales according to Darcy's law in heterogeneous materials:

where p

f is the fluid-pressure deviation from the hydrostatic pressure, β

f is the adiabatic fluid compressibility, and μ

f is the fluid dynamic viscosity. The locally averaged grain velocity is denoted

![]() ${\bar {\bi v}}$

. The local permeability is denoted k and is determined by empirical relations as a function of local porosity ϕ (Goren and others, Reference Goren, Aharonov, Sparks and Toussaint2011; Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2015). The second term on the right-hand side forces a response in water pressure as local porosity changes, and is corrected for advection of porosity. For the sake of simplicity, the fluid-flow model considers the whole domain as porous, with a very high porosity and permeability in the channel (see Fig. 2). The above equation is not adequate for simulating turbulent water flow and sediment in bedload inside the channel.

${\bar {\bi v}}$

. The local permeability is denoted k and is determined by empirical relations as a function of local porosity ϕ (Goren and others, Reference Goren, Aharonov, Sparks and Toussaint2011; Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2015). The second term on the right-hand side forces a response in water pressure as local porosity changes, and is corrected for advection of porosity. For the sake of simplicity, the fluid-flow model considers the whole domain as porous, with a very high porosity and permeability in the channel (see Fig. 2). The above equation is not adequate for simulating turbulent water flow and sediment in bedload inside the channel.

Fig. 2. Overview of the granular assemblage of 58 000 particles and the discretization of the fluid grid. We assume symmetry around the channel center (+x) and limit our simulation domain to one of the sides. The model domains of the two phases are superimposed during the simulations.

We calculate the fluid-phase dynamics (Eqn 14) on an Eulerian and regular grid, superimposed over the granular assemblage. The fluid is fully two-way coupled to the granular phase. The fluid forces the sediment through spatial pressure gradients different from the hydrostatic pressure distribution, and the sediment forces the fluid phase by local changes in porosity (e.g., McNamara and others, Reference McNamara, Flekkøy and Måløy2000; Goren and others, Reference Goren, Aharonov, Sparks and Toussaint2011; Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2015). Contrary to our previous two-phase modeling studies (Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2015, Reference Damsgaard2016), the fluid grid is adjusted in size to the spatial domain of the granular phase during the simulations in order to correctly resolve the dynamics during volumetric changes, without requiring a constant-pressure boundary condition at the top.

2.3. Design of numerical experiments

The purpose of our numerical experiments is to test the hypothesis that sediment dynamics plays an important role in shaping subglacial channels. We design our experiments to simulate the sediment surrounding a channel cavity, which is stressed by a virtual ice–bed interface modeled as a horizontal wall with a pre-defined normal stress. The model is three dimensional in order to correctly resolve grain rotation and interlocking, but the simulation domain is shortened in the along-flow dimension (y) in order to reduce the computational overhead.

We perform dry (water-free) and wet (water-saturated) simulations, with the hypothesis that the presence of water without large pressure gradients does not influence sediment stability, as long as the effective normal stress is equal. The dry simulations (Fig. 3) are designed to inform about steady-state channel geometries under a constant normal stress on the top boundary, which spans the ice–sediment interface and the channel conduit. We perform these simulations without water in order to illustrate pure granular mechanics without transient hardening or softening associated with a pore-fluid pressurization (e.g., Iverson and others, Reference Iverson, Hooyer and Baker1998; Moore and Iverson, Reference Moore and Iverson2002; Goren and others, Reference Goren, Aharonov, Sparks and Toussaint2011; Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2015). The omission of fluid in these simulations additionally serves to reduce the required computational time.

Fig. 3. Boundary conditions and initial state in the presented simulations for the granular phase in the dry experiments. The frictionless lateral boundaries imply no boundary-parallel movement.

For the second set of experiments, we employ wet (water-saturated) simulations (Fig. 4) to investigate sediment stability under various defined water-pressure gradients. The water pressures are kept constant at the channel and at the far-away lateral boundary (x = 0 m in Fig. 2), and water pressures are inside the sediment initialized according to a linear interpolation between these Dirichlet boundary conditions. After the initialization procedure, described below, the porosity at the top of the sediment is naturally larger because of the flat ice–bed interface. Additionally, the porosity generally tends to slightly decrease with depth as lithostatic pressure and packing density increases. Local deviations in water pressure from the hydrostatic pressure distribution directly affect the stress balance inside the sediment and at the upper boundary.

Fig. 4. Boundary conditions and initial state in the presented simulations for the granular and fluid phases in the wet experiments.

The granular assemblage is prepared by letting 1000 uniformly distributed and spherical particles settle in a small cubic volume under the influence of gravity. Afterwards the assemblage is duplicated and repositioned 58 times in space to construct the desired geometry for a total of 58 000 grains. We assume that the channel is horizontally symmetrical around its center and simulate half of the channel width. Before proceeding with our main experiments we perform a relaxation step where we allow the grains to settle and adjust their arrangement to the new geometry. Figures 3, 4 show the boundary conditions, as well as the geometry of the simulated sediment at the beginning of the experiments. Table 1 lists the values of the relevant geometrical, mechanical, and temporal parameters.

Table 1. Simulation parameters and their values for the granular experiments

* Simulation time and time-dependent parameters are listed in scaled model time, see Damsgaard and others (Reference Damsgaard2015, Reference Damsgaard2016).

The governing equation for fluid dynamics (Eqn 14) is in its standard form singular for areas that do not contain grains (ϕ = 1), such as the channel cavity. We therefore impose an upper limit on porosity of ϕ = 0.9 in Eqn (14) and the other fluid-related equations in order to allow our fluid-phase formulation to work for the channel conduit. Nonetheless, the strong non-linearity of the permeability relation (k = 3.5 × 10−13m2 ϕ 3(1 − ϕ)−2) causes much faster diffusion of fluid pressures in the conduit than internally in the sediment, consistent with our expectations of how the hydraulic system should behave. However, we are for the purposes of this study mainly interested in the mechanical behavior of the sediment surrounding the channel. Similarly, we do not resolve water flow along the channel length axis, but focus our experimental analysis of grain-fluid interaction inside of the sediment with the channel cavity acting more as a boundary condition.

We choose a relatively low value for Young's modulus in Eqn (11) in order to increase the computational time step (Eqn 13 and Table 1), but the resultant elastic softening has negligible effect on porosity and mechanical behavior. Compressive strain on grain contacts is in our model due to the softening expected to be a hundred times greater than theoretical values for quartz, but the actual strains remain very small (2 × 10−3% of the grain radius under a compressive stress of 10 kPa). Furthermore, we chose a relatively large grain size and narrow grain-size distribution to increase computational efficiency during the grain-to-grain contact searches. At the same time, the hydraulic properties are decoupled from sediment size to allow for low-permeability simulations with relatively large grains (Goren and others, Reference Goren, Aharonov, Sparks and Toussaint2011; Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2015). We do note that the simplification in grain size, shape, and morphology will influence granular deformation patterns and sediment frictional properties (e.g., Iverson and others, Reference Iverson, Hooyer and Baker1998; Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2013). We also omit tensile interactions between grains giving cohesionless behavior. However, apparent cohesion observed in laboratory shear tests on real geological materials often vanishes at very low normal stresses (e.g., Schellart, Reference Schellart2000), making grain-tension less important at free sediment surfaces.

We assume that channels in subglacial beds inherently form due to flow instabilities by differential erosion, similar to the processes driving distributed flow to R-channel drainage on hard beds. Intrinsic channelization during fluid flow has been demonstrated in physical dam-breach experiments (e.g., Walder and others, Reference Walder, Iverson, Godt, Logan and Solovitz2015) and in smaller experimental studies (e.g., Catania and Paola, Reference Catania and Paola2001; Mahadevan and others, Reference Mahadevan, Orpe, Kudrolli and Mahadevan2012; Kudrolli and Clotet, Reference Kudrolli and Clotet2016; Métivier and others, Reference Métivier, Lajeunesse and Devauchelle2017). Channelization occurs when fluid flux is able to erode the porous medium through which it is flowing. In turn, this process reduces local friction against the fluid flux and further enhances flow localization. In this study, we investigate the mechanical state and deformation patterns around an already established channel conduit incised into the sedimentary bed, and are not able to include the process of channel formation itself.

3. RESULTS

We do not observe significant differences in steady-state channel geometry between the dry and wet simulations at equal effective normal stresses, which is expected as the fluid only affects the granular force balance in the presence of water-pressure gradients (Eqn 12). However, the wet simulations take three times longer to complete.

In the dry experiments, we observe that the effective normal stress on the channel flanks results in rapid failure, occurring over a few seconds (Fig. 5). Larger normal stresses result in more deformation. Consistent with sediment plasticity, the deformation stops when a new stress balance has been established. The final and steady-state geometries are shown in Figure 6, where larger normal stresses result in smaller channel cavities. We do expect slow creep in the sediment, especially if there are large fluctuations in water pressure and granular stresses (Pons and others, Reference Pons, Amon, Darnige, Crassous and Clément2015; Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2016) or strong water flow (Houssais and others, Reference Houssais, Ortiz, Durian and Jerolmack2015, Reference Houssais, Ortiz, Durian and Jerolmack2016). However, the associated creep is expected to occur with a significantly more non-linear rheology than previously used for soft-bed channels (e.g., Alley, Reference Alley1992; Walder and Fowler, Reference Walder and Fowler1994; Ng, Reference Ng2000b; Carter and others, Reference Carter, Fricker and Siegfried2017), and we do not detect measurable creep on the timescales considered here (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Averaged grain displacements through time for a range of effective normal stresses, N in the dry granular experiments.

Fig. 6. Channel geometries in the steady state at different effective normal stresses N in dry experiments. Grains are colored according to their cumulative vertical displacement and rendered in an orthogonal projection. The absence of water does not influence the steady-state geometry unless the sediment is flushed by strong water-pressure gradients.

We can describe the relationship between the imposed effective normal stress and observed maximum channel width reasonably well by a linear fit (Fig. 7):

with fitting parameter values a = −0.118 m kPa−1 and b = 4.60 m (associated standard deviations (std dev.) reported in Fig. 7). By assuming a simple geometry where the slope of the channel flanks is given by the sediment angle of repose θ (Fig. 8), we can approximate the limit to channel the cross-sectional area, S max as a function of the channel width:

We constrain the channel size in the continuum channel model (Eqns 1–6) in order to capture the stress-based limits. We do not view extrapolation of the channel width below the tasted range (N = [2.5;40] kPa) as physically meaningful. Geometries with slopes beneath the angle of repose should be stable without load from the ice overburden under events with overpressurized water (N ≤ 0 kPa), allowing for the existence of larger subglacial cavities.

Fig. 7. Observed maximum channel width, W max, under a constant imposed value for effective normal stress, N. Data points are fitted using a non-linear least-squares fit, with fitted parameter values and their corresponding std dev. noted.

Fig. 8. Idealized schematic of effective stress magnitude and till yield strength in a cross-section around a subglacial channel incised in the sedimentary bed. Sediments beneath the channel floor are not stressed by ice weight on the flanks, and comprise a weak channel floor wedge (CFW).

The grain-scale stress balance (Fig. 9) shows that stresses from the ice load on channel flanks are transmitted predominantly downwards, and do not affect the stress balance in the sediment beneath the channel conduit. The sediment beneath the channel conduit is loaded exclusively by its own weight (lithostatic pressure), which increases linearly with depth. This behavior contrasts with viscous till models, that assume that the stress on the channel flanks contributes to till uplift at the bottom of the channel.

Fig. 9. Contact pressure on the grains

![]() $\left(\sum \vert\vert{\bi f}_{\rm n}\vert\vert 4 \pi r^2 \right)$

in the steady state with an effective stress of N = 7 kPa.

$\left(\sum \vert\vert{\bi f}_{\rm n}\vert\vert 4 \pi r^2 \right)$

in the steady state with an effective stress of N = 7 kPa.

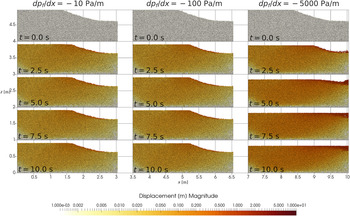

In our wet simulations, forced with water-pressure differences between channel and bed, the pressure-gradients create drag forces on the grains oriented towards the channel (Fig. 10). The presence of smaller water-pressure gradients cause minor sediment rearrangement, but deformation rapidly decays and the channel continues to be stable (Fig. 11, left and center). The channel geometry is not significantly different from the dry experiment under small water-pressure gradients (compare the simulation with N = 10 kPa in Fig. 6 with Fig. 11, left and center). However, when larger pressure gradients are prescribed the sediment flushes into the channel, causing rapid channel infill and closure (Fig. 11, right).

Fig. 10. Fluid-pressure forces (Eqn 12) on the individual sediment grains visualized by arrows. Top: Under low gradients in pore-water pressure (here dp f/dx = −0.1 kPa m−1), the fluid-pressure force primarily contributes weak buoyant uplift on the grains. Bottom: Larger pressure gradients (dp f /dx = − 10 kPa m−1) destabilize the sediment through liquefaction at the channel floor and cause collapse of the sediment with associated chaotic interactions (e.g., large internal forces). Individual force vectors are not representative of the grain ensemble and should not be interpreted directly. Both simulation snapshots are from t = 1.5 s.

Fig. 11. Total per-grain spatial displacements at different times for three wet (water-saturated) simulations with different imposed water-pressure gradients and an effective stress of N = 10 kPa. The water-pressure gradients cause flow and drag forces toward the channel, and destabilize the conduit at higher values.

Figure 12 shows the results of an example implementation of the continuum channel model (Eqns 1–6, with limits to channel size imposed by Eqns 15 and 16). The solution is found iteratively with a Dirichlet boundary condition of P c = 0 Pa at the terminus. Gradients are estimated with upwind finite difference approximations. We assume that channel effective pressure (P c) equals the magnitude of the effective normal stress on the channel flanks (N). In real settings channel effective pressure will most commonly be slightly higher than normal stress on the flanks (P c > || N ||), as water pressure differences cause dominant water flow towards the channel.

Fig. 12. Example run of the soft-bed subglacial channel model outlined in Eqns (1–6, 15 and 16), with a square-root ice geometry and linearly increasing meltwater influx (

![]() ${\dot m}$

) towards +s. Top: Channel effective pressure (P

c), ice-overburden pressure (P

i), water-pressure (P

w) and water flux (Q). Middle: Sediment flux increases non-linearly with water flux (Eqn 2). Bottom: Maximum (S

max) and actual channel cross-sectional size (S), together with channel growth rate (dS/dt). This example is with a constant forcing and t = 2 days. The minimum channel size is set to S = 0.01 m2 for numerical considerations. In this example the sediment yield strength prevents channel existence except near the terminus where effective pressure is relatively low.

${\dot m}$

) towards +s. Top: Channel effective pressure (P

c), ice-overburden pressure (P

i), water-pressure (P

w) and water flux (Q). Middle: Sediment flux increases non-linearly with water flux (Eqn 2). Bottom: Maximum (S

max) and actual channel cross-sectional size (S), together with channel growth rate (dS/dt). This example is with a constant forcing and t = 2 days. The minimum channel size is set to S = 0.01 m2 for numerical considerations. In this example the sediment yield strength prevents channel existence except near the terminus where effective pressure is relatively low.

In this example, the water fluxes are increasing downstream due to the water supply (

![]() ${\dot m}$

). The increasing water flux generally increases the sediment-bedload flux (Q

s) downstream. At s = 0 to 0.8 km the large effective pressures (P

c) inhibit channel development due to sediment failure. Close to the margin (s = 0.8–1.0 km) the effective pressure is sufficiently low to allow for channel existence. The increase in channel cross-sectional size near the margin decreases the fluvial shear stress and causes a rapid drop in fluvial sediment flux Q

s.

${\dot m}$

). The increasing water flux generally increases the sediment-bedload flux (Q

s) downstream. At s = 0 to 0.8 km the large effective pressures (P

c) inhibit channel development due to sediment failure. Close to the margin (s = 0.8–1.0 km) the effective pressure is sufficiently low to allow for channel existence. The increase in channel cross-sectional size near the margin decreases the fluvial shear stress and causes a rapid drop in fluvial sediment flux Q

s.

4. DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that sediment yield strength can prevent collapse of channels. Because of sediment plasticity, channel erosion into subglacial sediments is not balanced by a continuous flux of viscous till deformation into the channel cavity, which was assumed in prior parameterizations (e.g., Fowler and Walder, Reference Fowler and Walder1993; Walder and Fowler, Reference Walder and Fowler1994; Ng, Reference Ng2000b). Instead, channel cross-sectional geometry is governed by fluvial erosive and depositional dynamics until channel size is limited by sediment yield strength.

Infilled fossil subglacial channels seen in field sections along the southern margin of the last Scandinavian Ice Sheet (Fig. 13) show similar geometry to the stable channel conduits observed in our granular experiments (e.g., Figs 6, 11), where the sediment angle of repose is a principal control on channel cross-sectional geometry. The channel sizes observed in the field (Fig. 13) are within the limits observed in our granular experiments (Fig. 7) and the simplified ice-marginal area of our continuum channel model (Fig. 12).

Fig. 13. Examples of infilled subglacial channels in the southern, marginal part of the Scandinavian Ice Sheet from the last glaciation (Piotrowski et al., in prep.). (a) Subglacial channel at Ebeltoft, Djursland, Denmark. The channel is found within a single till unit about 10 km inside the ice margin. It is flat-topped and filled with parallel-bedded outwash sand and gravel intercalated with layers of silt. Single outsized stones, possibly dropped from the channel roof are randomly dispersed in the outwash deposit. Along the channel bottom and on its left-hand side the infill material is deformed into attenuated folds, irregular detached sediment pods and flame structures. Since the flanks of the channel are below the angle of repose of sand, the deformation structures suggest syndepositional sediment intrusion into the channel driven by a pressure gradient oriented toward the channel axis. (b). Subglacial channel at Glaznoty, north-central Poland, about 25 km within the ice limit. The channel occurs at the interface between proglacial outwash deposits (below) and till (above). The channel is distinctly lens-shaped with an upward-convex top suggesting an R-channel incised upward into the ice at a late stage of formation. It is infilled with massive coarse-grained sand and gravel.

While Shoemaker (Reference Shoemaker1986) assumed that the bed would strengthen against failure under high effective stresses, we show that the magnitude of effective stress on the bed surrounding the channel puts an upper limit on channel dimensions. The exact relationship between effective normal stress and channel size (Fig. 7) will be material dependent, and the granular model applied here includes several simplifying assumptions related to grain size and grain shape. The grain angularity and size distribution in subglacial tills might result in slightly larger yield strengths and allow for the existence of larger channels. Overconsolidation of subglacial tills additionally contributes to shear strength (e.g. Tulaczyk and others, Reference Tulaczyk, Kamb and Engelhardt2000a), which will increase stability and limits to channel size. However, the stress–size relationship presented here should be a reasonable approximation for a simple model. While our results are based on numerical experiments on simplistic granular materials, our interpretation stands that it is unlikely for soft-bed channels to exist at effective subglacial normal stresses more than ~100 kPa in magnitude (Fig. 7). We propose that the constrained relationship between channel geometry and effective normal stress makes it theoretically possible to asses water pressure and hydrological conditions under past ice sheets, e.g. when meltwater channels are identified from geomorphological interpretation of subaerial or subaqueous topography (e.g., Lesemann and others, Reference Lesemann, Piotrowski and Wysota2010; Greenwood and others, Reference Greenwood, Clason, Nyberg, Jakobsson and Holmlund2016; Bjarnadóttir and others, Reference Bjarnadóttir, Winsborrow and Andreassen2017), or from channel-sediment geometries in the glaciogeological sedimentary record (e.g., Piotrowski, Reference Piotrowski1999; Tylmann and others, Reference Tylmann, Piotrowski and Wysota2013).

Ice overburden stress does not impact the sediments beneath the channel floor directly; the compressive stress acting on channel-floor sediments is a result of their own weight as lithostatic pressure increases with depth (Fig. 9). Sediment dynamics at the floor of subglacial channels are then similar to those in subaerial rivers, although the drainage system arrangement may differ (Catania and Paola, Reference Catania and Paola2001; Métivier and others, Reference Métivier, Lajeunesse and Devauchelle2017). Due to the plastic rheology of sediment, erosion of the channel floor will be counteracted by an immediate sediment response when the channel is at its size limit, acting to reestablish stress balance in the bed surrounding the channel. If differential sediment advection toward the cavity bends the ice–bed interface downwards progressively, the resultant channel landform of erosive origin is likely to appear wider than the channel cavity itself (Boulton and Hindmarsh, Reference Boulton and Hindmarsh1987; Ng, Reference Ng2000b).

The evolution of subaerial river size is governed by feedbacks and stability limits (e.g. Métivier and others, Reference Métivier, Lajeunesse and Devauchelle2017). We conclude that there are two distinct feedbacks stabilizing subglacial channel size on soft beds: (1) If a channel becomes sufficiently efficient in evacuating subglacial meltwater, the pore-water pressure decreases and the effective normal stress on the surrounding areas of the bed increases. If this stress increase causes the channel size to exceed the stability limit, the channel spontaneously reduces in size which decreases the hydrological transport capacity which, in turn, can increase the water pressure and decrease the effective normal stress. (2) For a given water flux, an increase in channel cross-sectional size due to fluvial erosion decreases the water-driven shear stress on the channel bottom. The decrease in shear stress decreases sediment transport (Eqn 2), which decreases channel growth (decreasing ∂Q s/∂s in Eqn 1). These feedbacks may ultimately lead to stabilization of subglacial sliding and hydrology, tied to the plastic failure limit of the bed and the basal hydraulic transmissivity.

For the subglacial drainage model presented here, we consider channelized flow alone although it could be significantly improved by coupling it to a diffusive flow model accounting for sheet flow at the ice–bed interface, groundwater flow, and/or R-channel incision (e.g., Creyts and Schoof, Reference Creyts and Schoof2009; Hewitt, Reference Hewitt2011; Werder and others, Reference Werder, Hewitt, Schoof and Flowers2013; Flowers, Reference Flowers2015). Furthermore, the parameterization for water flux in the channel can be improved by including both laminar and turbulent descriptions, dependent on the Reynolds number of the water flow (e.g., van der Wel and others, Reference van der Wel, Christoffersen and Bougamont2013).

With increasing subglacial discharge, we expect a hydraulic transition from distributed drainage to sediment-incised channels (e.g., Mahadevan and others, Reference Mahadevan, Orpe, Kudrolli and Mahadevan2012; Kudrolli and Clotet, Reference Kudrolli and Clotet2016). However, yield failure of the channel flanks imposes a limit to their cross-sectional area and hydraulic transport capacity. If the hydraulic transmissivity becomes insufficient against the water fluxes, we either expect R-channel incision into the ice base, or the formation of multiple parallel drainage channels incised into the sediment. If subglacial soft-bed channels were able to grow without size constraints, it would be thermodynamically more efficient to gather drainage in fewer and larger channels.

An arrangement of closely spaced channel drainage is observed at Glaznoty, north-central Poland, where the channel in Figure 13 is one of a series of small, similar-sized channels occurring at the paleo-ice–bed interface. Parallel sediment landforms (glacial curvilineations) have been observed from under the palao-Scandinavian Ice Sheet (Fig. 1, Lesemann and others, Reference Lesemann, Piotrowski and Wysota2010, Reference Lesemann, Piotrowski and Wysota2014), which may be governed by the channel-size limits described here. Furthermore, radar-echo soundings of the sedimentary bed of Thwaites Glacier, West Antarctica have been interpreted to reflect hydraulic transitions between few to many parallel and closely spaced channelized drainage elements incised into the sedimentary bed (Schroeder and others, Reference Schroeder, Blankenship and Young2013). We do note that the landforms and channel-drainage elements observed in the glacial curvilineations are generally larger than what is predicted from our limits related to plastic failure (Fig. 7). We believe that this discrepancy is mainly related to the fact that the numerical material with spherical and smooth grains is mechanically weaker than subglacial tills with elongated and angular grains.

Liquefaction at the earth surface and in subaqueous environments is known to be initiated by overpressurization in the pore space, effectively reducing the compressive stress to low or even negative values (e.g., Zhang and Campbell, Reference Zhang and Campbell1992; Terzaghi and others, Reference Terzaghi, Peck and Mesri1996; Xu and Yu, Reference Xu and Yu1997; Mitchell and Soga, Reference Mitchell and Soga2005). In situ measurements of subglacial water pressure indicate that water pressures are highly variable through time (e.g., Hooke, Reference Hooke1984; Engelhardt and Kamb, Reference Engelhardt and Kamb1997; Hooke and others, Reference Hooke, Hanson, Iverson, Jansson and Fischer1997; Bartholomaus and others, Reference Bartholomaus, Anderson and Anderson2008; Andrews and others, Reference Andrews2014; Schoof and others, Reference Schoof, Rada, Wilson, Flowers and Haseloff2014). We propose that events of liquefaction in subglacial channels may be common when water-pressure in the channel rapidly decreases, and this process may be able to make significant volumes of weak sediment from the channel-floor wedge available for fluvial transport, especially in sedimentary beds with low permeability that require long timescales to respond to changes in interfacial water pressure.

As previously discussed, we are not able to include the effect of subglacial deformation due to ice movement along the channel length, which might be important for long-term channel stability. We do note that subglacial shear could be included by setting the y boundaries to be periodic (e.g., Damsgaard and others, Reference Damsgaard2013), but the spatial domain length along y in the current setup is too short to allow for shearing without geometrical instabilities. Sediment advection associated with shear deformation causes frictional heating and granular diffusion (e.g., Hooyer and Iverson, Reference Hooyer and Iverson2000; Utter and Behringer, Reference Utter and Behringer2004); these process are likely to drive channel closure with a rate proportional to the shear-strain rate in the sediment. We also assume that the ice–bed interface remains flat and rigid over time, while Ng (Reference Ng2000b) demonstrated that differential ice and till advection toward the channel conduit bends the interface over longer timescales. Our model approach could be improved by simulating a dynamically evolving ice-bed interficial geometry. However, we believe that inclinations in the ice–bed interface are unlikely to fundamentally alter the principal stresses in the surrounding sediment, and assume that the ice is responding elastically over the timescales investigated in the experiments (<1 min).

5. CONCLUSIONS

Current relationships for subglacial channel dynamics incised into sedimentary beds assume linear to mildly non-linear viscous relationships for till rheology, which results in continuous sediment flux toward the channel balancing erosion by water flow. However, sediments are known to be nearly perfect plastic with a yield strength dependent on the confining stress.

We have coupled two separate models to gain a multi-scale understanding between sediment deformation and subglacial channel stability. Our granular model informs about sediment stability under different effective normal stresses and water-pressure forcings. We observe that the channel conduit size is strongly limited by the magnitude of effective normal stress on the channel flanks, and that creep closure is negligible. The compressive stresses from the ice–bed interface on the channel flanks are oriented subvertically instead of being directed towards the channel floor. The channel-flooring sediments are only compacted by their own weight. Strong water-pressure differences between the channel and its surrounding parts can cause horizontal infilling by sediment movement along the ice–bed interface.

We use the results from our granular simulations to include effects of sediment plasticity in a continuum model of soft-bed subglacial channels. The channel size is limited by the yield strength of the sediment, which in turn depends on effective normal stress on the channel flanks. The size limit implies that multiple closely spaced channels are needed for transporting large amounts of water, which corresponds to geophysical observations under contemporary ice sheets and geomorphological signatures from previously glaciated areas. The presented continuum model for channelized drainage, derived from our suite of numerical simulations, increases the realism of hydrology models for ice sheets and glaciers residing on soft beds.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A. Damsgaard was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship by the Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Foundation and NSF-PLR-1543396. A. Damsgaard acknowledges the NVIDIA Corporation for a hardware grant and the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment (XSEDE) for a high-performance computing startup allocation. In preparation for this paper, A. Damsgaard has benefited from discussions with C. W. Elsworth, L. Goren, I. J. Hewitt, S. P. Carter, A. Cabrales-Vargas, and V. Tsai. We thank Jonathan Kingslake and anonymous reviewer for constructive comments, which improved the manuscript and Neil Glasser for handling the editorial process.

APPENDIX A. SOURCE CODE AVAILABILITY

The source code for the grain-fluid model is available at https://github.com/anders-dc/sphere, where the script channel-wet.py can be used as a template for model runs. An example implementation of the subglacial hydrology model built on channelization dynamics is available from https://github.com/anders-dc/granular-channel-hydro/blob/master/1d-channel.py.