People with severe mental illness (SMI), including those with schizophrenia, schizophrenia-like disorders, bipolar disorder and severe affective disorders, on average die at a younger age compared with the general population. Reference Chang, Hayes, Perera, Broadbent, Fernandes and Lee1–Reference Chesney, Goodwin and Fazel4 In the UK men with SMI die 8–15 years and women 7–18 years earlier than those without mental disorders. Reference Chang, Hayes, Perera, Broadbent, Fernandes and Lee1 This life expectancy gap is increasing. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely2 Although suicide is an important cause of death in those with SMI, the majority of preventable deaths are due to chronic disease, primarily cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and respiratory diseases. Reference Lawrence, Hancock and Kisely2,Reference Brown, Kim, Mitchell and Inskip5 In England and Wales people with schizophrenia have a three-fold risk of premature mortality compared with the general population; Brown et al found that risk of unnatural death (violent deaths and suicide) declined significantly between 1982 and 2006, whereas the risk of premature death due to cardiovascular disease more than doubled in comparison with the general population. Reference Brown, Kim, Mitchell and Inskip5 A complex web of factors contributes to this life expectancy gap. The side-effects of psychotropic medications, particularly weight gain and impaired glucose tolerance, increase the risk of excess mortality in people with SMI directly through obesity and diabetes. Reference De Hert, Detraux, van Winkel, Yu and Correll6 Unhealthy lifestyles include inactivity and diets that are high in fat and low in fruit and vegetables; these lifestyle factors may be consequences of negative symptoms of mental illness as well as poor emotional regulation. Reference Scott, Wu, Saunders, Benjet, He, Lepine, Alonso, Chatterji and He7 In addition, there is a growing body of evidence that unequal healthcare provision contributes to the life expectancy gap. Reference Lawrence and Kisely8 Mental disorders are associated with poorer clinical management of disease. People with SMI are less likely to receive timely and precise diagnosis because of ‘diagnostic overshadowing’ – that is, physical complaints are overlooked and partially or totally attributed to psychological and psychiatric factors. Reference Bailey, Thorpe and Smith9 Differential access to effective care leads to poorer outcomes including preventable deaths, Reference Liao, Shen, Chang, Chang and Chen10 and incurs high costs in healthcare provision. 11 Although evidence-based interventions for improving chronic disease outcomes are available there is little evidence of committed implementation for people with SMI. This may be driven by a lack of awareness of gaps in healthcare by the service providers, and poor knowledge about the strength of the evidence for specific interventions. Reference Bailey, Thorpe and Smith9 Despite extensive research showing reduced life expectancy for people with severe mental illness, a comprehensive synthesis of existing evidence on interventions that might reduce mortality has not been attempted. This is necessary to guide practitioners and commissioners.

This meta-review aimed to assess the evidence for the impact of health interventions in reducing excess mortality in people with severe mental illness. Reviews were sought that examined trials reporting mortality or physical health outcomes in people with SMI compared with those receiving ‘usual care’. As the major causes of excess deaths in these people are chronic diseases, we focused on interventions that might have an impact on physiological health indicators for these conditions. There is no single definition of chronic disease, Reference Goodman, Posner, Huang, Parekh and Koh12 so for consistency we decided to focus on physiological markers for common cardiometabolic diseases.

Method

The review was conducted in 2014 according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and Group13 We focused on existing syntheses of the literature in which authors had looked at the effects of health interventions in people with SMI, generally defined in the mental and physical health literature as psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective and schizophrenia-like illnesses), bipolar disorder and severe major depression, Reference De Hert, Correll, Bobes, Cetkovich-Bakmas, Cohen and Asai14 and where mortality or physiological health parameters were reported as a primary outcome. We used a broad search string (e.g. [‘mental disorders’ OR schizo* OR depress* OR bipolar*] AND [interventions OR treatment] AND [mortality OR survival]) to search the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), the Campbell Collaboration database of systematic reviews and the Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews (DoPHER). We conducted additional searches of citation lists from research papers and reports to identify additional reviews. Specific databases searched and the search strings used are reported in the online data supplement.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Systematic reviews were accepted if they included studies that compared an intervention with a control group for people with SMI. Because reviews that included mortality or survival outcomes were scarce, secondary physiological outcomes associated with chronic disease were also included: metabolic factors such as glycaemic control, dyslipidaemia and weight gain. Reviews of studies that reported only measures of behavioural change were not captured as the aim was to draw a stronger link between interventions and their potential to reduce premature mortality. We accepted any review that reported results of randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies and observational studies. Only reviews that employed systematic search methods and reported effect sizes were included. No limitation was placed on language, date of publication or publication status. Reviews that considered only studies of individuals with pre-existing physical conditions such as cardiac disease were excluded. Although this is an important area of research, causal direction is distinct in these patients compared with people with SMI who develop chronic disease.

Synthesis method

Titles and abstracts of all reviews were screened; relevant reviews were subjected to full text examination and were evaluated against the study criteria. Where multiple iterations of a review were found (e.g. a 2014 update was found for a 2010 Cochrane review), Reference Tosh, Clifton, Mala and Bachner15,Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White16 only the most up-to-date review was included. All reviews entering the study were downloaded into an EndNote database and duplicates were removed. Information describing study design, sample and comparison groups, interventions and outcome data were extracted from the full text. Two researchers (A.J.B. and Y.K.) independently extracted the data, and where discrepancies were found a third reviewer (M.G.H.) adjudicated differences. Types of interventions were identified and grouped into broad categories. Given that meta-analyses were not possible owing to heterogeneity in study design and focus, study findings were synthesised narratively to explore the impact of different types of interventions.

Quality assessment

Review quality was assessed using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) measurement tool, developed specifically to assess the quality of systematic reviews with reference to the methodological and systematic rigour and synthesis of the evidence. Reference Shea, Grimshaw, Wells, Boers, Andersson and Hamel17 This enables the quality of a systematic review to be scored on the following 11 items (scored as yes, 1; no, can't answer or not applicable, 0):

-

(a) Was an a priori design provided?

-

(b) Were there duplicate study selection and data extraction?

-

(c) Was a comprehensive literature search performed?

-

(d) Was the status of publication (i.e. grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion?

-

(e) Was a list of studies (included and excluded) provided?

-

(f) Were the characteristics of the included studies provided?

-

(g) Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented?

-

(h) Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions?

-

(i) Were the methods used to combine the findings of the studies appropriate?

-

(j) Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed?

-

(k) Was the conflict of interest stated?

The authors of AMSTAR provide guidance notes as to how each item is scored. This guidance was followed with the exception of the final item, where clear acknowledgement of potential sources of support in the systematic review – rather than ‘the review and the included studies’ – sufficed to be scored as ‘yes’. The validity and reliability of AMSTAR have been established. Reference Shea, Grimshaw, Wells, Boers, Andersson and Hamel17,Reference Shea, Hamel, Wells, Bouter, Kristjansson and Grimshaw18

Results

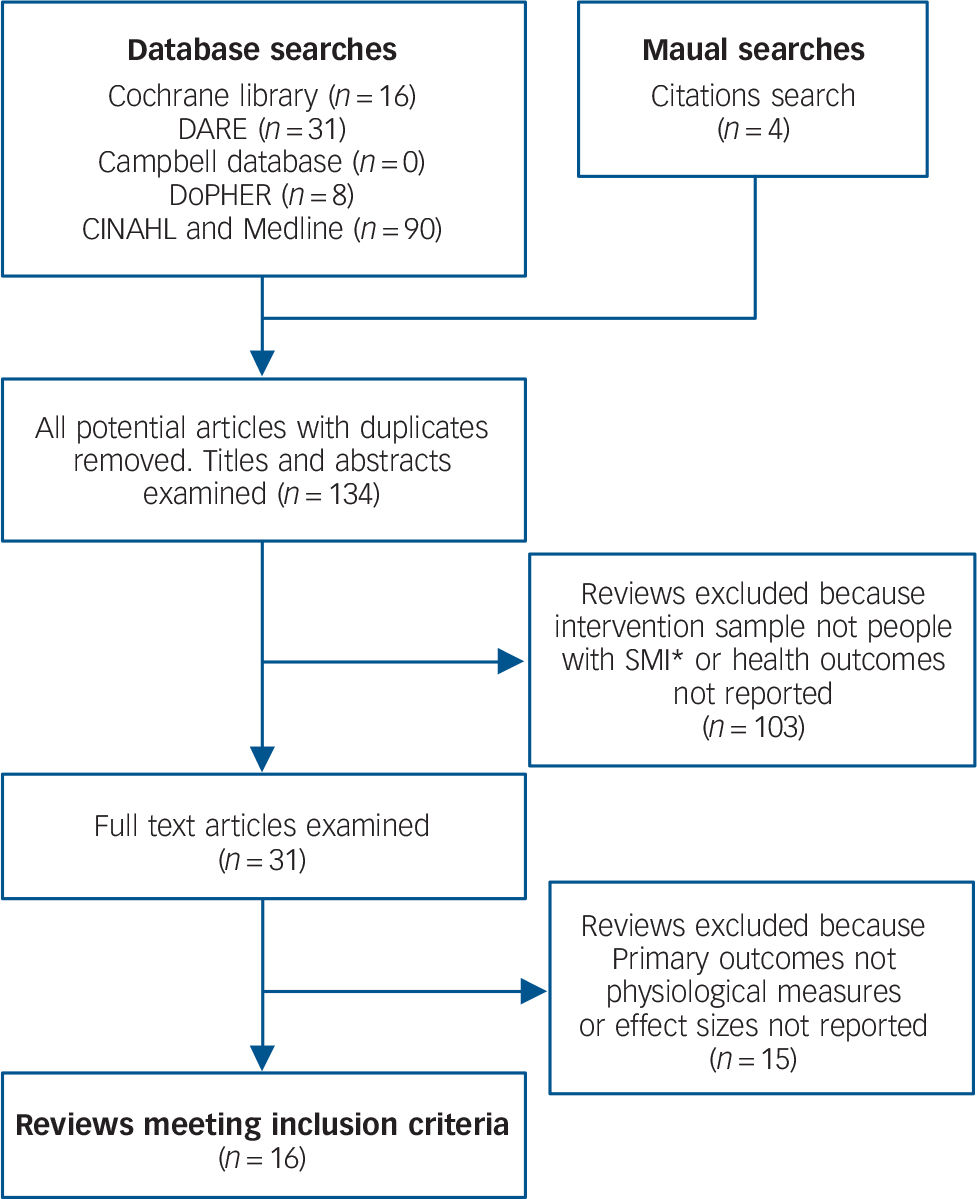

The database and citation searches yielded a total of 134 unique reviews. In total, 16 systematic reviews met the study criteria and entered the review (Fig. 1). The reviews showed substantial heterogeneity in terms of target groups, implementation strategy and outcome measures for the different categories of intervention. Of the 16 reviews included, eight identified mortality as an outcome of interest, including four that looked at both mortality and physiological health parameters, and another eight identified only physiological health parameters as outcomes. The quality of the included studies varied: out of a total score of 11 on the AMSTAR, six reviews achieved scores of 9 or above, six achieved scores between 6 and 8, and four achieved scores of 5 or lower. As there is no recommended cut-off for the AMSTAR, we refer to reviews scoring 9 or above as ‘high quality’, those scoring 6–8 as ‘medium quality’ and those scoring 5 or lower as ‘low quality’.

Fig. 1 Results of systematic search of the literature.

SMI, severe mental illness.

Overview of interventions

To facilitate comparison we grouped interventions into four categories: mental health interventions, integrative community care, interventions for lifestyle factors, and screening and monitoring of health parameters. Mental health interventions included psychiatric medications and psychological interventions including psychoeducational and behavioural therapies such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). Psychotherapies such as CBT are becoming increasingly available for people with SMI. These treatments can help link the person's distress and problem behaviours to underlying patterns of thinking with the aim of enhancing coping strategies and general problem-solving skills. 19 We defined integrative community care as multiprofessional team-based approaches to patient care, which aimed to improve mental and physical health outcomes in people with SMI. Components of care include scheduled patient follow-up and interprofessional communication between team members. Interventions aimed at improving lifestyle-related risk factors in people with SMI can take a variety of forms. We broadly categorised these reviews as having a primary outcome of reducing risky lifestyle factors. Interventions included pharmaceutical treatments and/or psychoeducational or behavioural approaches. These latter incorporate techniques such as problem-solving, goal-setting and self-monitoring, sometimes with a practical component in terms of an exercise regimen or dietary counselling. These are generally informed and adapted from existing lifestyle programmes developed for use in the general population. Findings of the reviews are summarised below by intervention category. Study characteristics and findings are summarised in online Table DS1 and AMSTAR quality ratings for each of the reviews included are given in online Table DS2.

Mental health interventions

We found two systematic reviews that focused on mortality-related outcomes associated with use of psychiatric medications, specifically antipsychotics and antidepressants. Reference Weinmann, Read and Aderhold20,Reference Von Ruden, Adson and Kotlyar21 Our search found one additional review that reported health outcomes of groups receiving psychological therapies. Reference Jones, Hacker, Cormac, Meaden and Irving22 The studies included in the two reviews looking at excess mortality and use of psychiatric medications varied enormously in terms of study design (including RCTs, data linkage studies, observational secondary analyses and cohort studies), follow-up periods, control groups and consideration of comorbidities and other risk factors. Reference Weinmann, Read and Aderhold20,Reference Von Ruden, Adson and Kotlyar21 In a medium-quality review Weinmann et al examined outcomes from 12 studies that looked at the risk of excess death in patients with schizophrenia prescribed antipsychotic medication. The majority of the studies included in their review showed that patients using antipsychotics were more likely to die prematurely compared with the general population. Reference Weinmann, Read and Aderhold20 In a comparison of patients using antipsychotics with those not using antipsychotics, however, there was increased mortality only where several antipsychotic drugs were prescribed (polypharmacy), with deaths increasing in relation to the number of medications (incremental relative risk (RR) per additional antipsychotic 2.50, 95% CI 1.46–3.40) or where patients had discontinued medication; Reference Joukamaa, Heliovaara, Knekt, Aromaa, Raitasalo and Lehtinen23,Reference Haukka, Tiihonen, Harkanen and Lonnqvist24 cited by Weinmann et al. Reference Weinmann, Read and Aderhold20 Two retrospective cohort studies reported a protective effect of antipsychotic use and these found a two-fold to ten-fold reduction in mortality for patients who used antipsychotics compared with those who did not; Reference Haukka, Tiihonen, Harkanen and Lonnqvist24,Reference Tiihonen, Walhbeck, Lonnqvist, Klaukka, Loannidis and Volavka25 cited by Weinmann et al. Reference Weinmann, Read and Aderhold20 However, observational studies may not adequately control for confounding variables such as disease severity and preferential prescribing. Reference Weinmann, Read and Aderhold20

A lower-quality review by Von Ruden et al identified three studies that looked at the association between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and mortality, all of which defined SSRI use as ‘exposure’ without providing information on period since treatment, mental health status or presence of other risk factors. Reference Von Ruden, Adson and Kotlyar21 Findings were heterogeneous, with the first study reporting a positive association between SSRI exposure and hospital admission or death (hazard ratio 1.47, 95% CI 1.26–1.70), the second reporting an inverse association with cardiovascular disease mortality (relative risk 0.37, 95% CI 0.17–0.78) and the third finding no relationship with subsequent cardiac mortality or morbidity; Reference Cohen, Gibson and Alderman26–Reference Tiihonen, Lonnqvist, Wahlbeck, Klaukka, Tanskanen and Haukka28 cited by Von Ruden et al. Reference Von Ruden, Adson and Kotlyar21

A third high-quality review looking at mental health interventions and their effect on mortality reduction examined the long-term effects of CBT in people with schizophrenia. Reference Jones, Hacker, Cormac, Meaden and Irving22 The authors identified two trials reporting mortality as an outcome, neither of which found a significant association between CBT and risk of excess mortality. We were unable to find any review that looked at the effect of psychotherapies (aimed at improving symptoms of mental disorders) on physiological health outcomes in people with depression or bipolar disorder.

Integrative community care

Two Cochrane reviews evaluated health outcomes in people with SMI allocated to integrative community care management or intensive case management. Reference Malone, Marriott, Newton-Howes, Simmonds and Tyrer29,Reference Dieterich, Irving, Park and Marshall30 In total the reviews identified 20 non-overlapping RCTs where all-cause and/or suicide deaths were reported as primary outcomes. In a high-quality review Dieterich et al pooled results from 14 RCTs comparing all-cause death for intensive case management v. standard care and results from 7 RCTs that evaluated mortality in intensive case management groups v. non-intensive management, and found no significant difference in risk of death. Reference Dieterich, Irving, Park and Marshall30 Malone et al found three RCTs that compared collaborative community health interventions v. standard care, producing a pooled RR of 0.47 (95% CI 0.17–1.34) for all-cause mortality. Reference Malone, Marriott, Newton-Howes, Simmonds and Tyrer29 Although no result in either review was statistically significant, the authors reported a general trend across the studies suggesting fewer deaths due to suicide or suspicious circumstances and few deaths overall in treatment groups. Neither study reported physical health markers as outcomes of interest.

Interventions for lifestyle factors

We found ten systematic reviews that measured health outcomes associated with lifestyle and behavioural interventions in people with SMI. Three reviews reported mortality as an outcome of interest, all of which scored highly on the AMSTAR scale. Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White31–Reference Hunt, Siegfried, Morley, Sitharthan and Cleary33 A Cochrane review by Tosh et al looked at interventions providing general health advice for people with SMI, reporting a broad range of outcomes including social and psychological health; physical health, awareness and behaviours; and adverse events such as death. Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White31 Of the seven studies identified in the review two measured all-cause mortality, Reference Danavall and Druss34,Reference Druss, von Esenwein, Compton, Rask, Zhao and Parker35 cited by Tosh et al, Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White31 and found no significant difference for reduced mortality in those receiving the intervention compared with treatment as usual (RR = 0.98, 95% CI 0.27–3.56). Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White31 A third study looking at fatal cardiovascular disease as an outcome found no significant reduction in cardiac fatalities; Reference Forsberg, Bjorkman, Sandman and Sandlund36 cited by Tosh et al. Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White31

Hunt et al identified 32 studies in a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs that looked at psychosocial interventions for treatment of substance use, seven of which considered mortality. Reference Hunt, Siegfried, Morley, Sitharthan and Cleary33 Analyses found no change in mortality risk associated with either intensive case management, integrated models of care or motivational interviewing alone. However, follow-up periods were short (the longest being 3 years) and there were few deaths in either case or control groups. Reference Hunt, Siegfried, Morley, Sitharthan and Cleary33 A third review, by Gierisch et al, found 32 RCTs that evaluated the effect of behavioural and/or pharmaceutical interventions aimed at reducing cardiovascular disease risk, including metabolic factors (weight, glycaemic control or dyslipidaemia). Reference Gierisch, Nieuwsma, Bradford, Wilder, Mann-Wrobel and McBroom32 This review also intended to examine mortality, but no death was reported in the included studies.

Weight loss or obesity management were the most commonly measured health indicators (nine studies), Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White31,Reference Gierisch, Nieuwsma, Bradford, Wilder, Mann-Wrobel and McBroom32,Reference Caemmerer, Correll, Christoph and Maayan37–Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington43 followed by metabolic risk factors such as glucose levels, lipid profiles and/or blood pressure (five studies), Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White31,Reference Gierisch, Nieuwsma, Bradford, Wilder, Mann-Wrobel and McBroom32,Reference Caemmerer, Correll, Christoph and Maayan37,Reference Van Hasselt, Krabbe, van Ittersum, Postma and Loonen40,Reference Cabassa, Ezell and Lewis-Fernandez41 and harmful substance use (two studies). Reference Hunt, Siegfried, Morley, Sitharthan and Cleary33,Reference Van Hasselt, Krabbe, van Ittersum, Postma and Loonen40,Reference Kisely and Campbell44 Studies identified in these reviews varied in terms of intervention types and outcome measures, and this hampered the ability to synthesise results; overall only four of the 11 reviews were able to report pooled effect sizes. Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White31–Reference Hunt, Siegfried, Morley, Sitharthan and Cleary33,Reference Caemmerer, Correll, Christoph and Maayan37 Overall, the reviews were consistent that interventions aimed at improving lifestyle factors can achieve modest but significant improvements in physical activity and eating habits. Reference Verhaeghe, De Maeseneer, Maes, Van Heeringen and Annemans39,Reference Van Hasselt, Krabbe, van Ittersum, Postma and Loonen40 They showed that interventions could effectively reduce antipsychotic-induced weight gain, Reference Gierisch, Nieuwsma, Bradford, Wilder, Mann-Wrobel and McBroom32,Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Hetrick, Gonzalez-Blanch, Gleeson and McGorry42,Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington43 and achieve weight loss or body mass index (BMI) reduction in those already overweight. Reference Gierisch, Nieuwsma, Bradford, Wilder, Mann-Wrobel and McBroom32,Reference Caemmerer, Correll, Christoph and Maayan37–Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington43 Where reviews looked at both pharmacological treatment and behavioural interventions, both approaches were associated with a similar magnitude of improvement in weight and/or BMI control. Reference Gierisch, Nieuwsma, Bradford, Wilder, Mann-Wrobel and McBroom32,Reference Alvarez-Jimenez, Hetrick, Gonzalez-Blanch, Gleeson and McGorry42,Reference Faulkner, Cohn and Remington43 Few studies evaluated interventions specifically designed to address outcomes such as metabolic syndrome, glycaemic control, dyslipidaemia, blood pressure or other physiological markers of disease; these were considered as secondary measures to other outcomes and so analyses were often underpowered. The review by Tosh et al cited one study that specifically evaluated a lifestyle programme and its effect on physical health. Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White31,Reference Forsberg, Bjorkman, Sandman and Sandlund36 Although no effect was found for mediation of metabolic syndrome in people with SMI, there was a trend for fewer metabolic risks, from 13 to 10, after 1 year of follow-up. Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White31

A review by Gierisch et al found two out of the seven studies with glycaemic control as an outcome showed a significant improvement in the invention group over the control group; in both cases metformin was prescribed as treatment. Reference Gierisch, Nieuwsma, Bradford, Wilder, Mann-Wrobel and McBroom32 More positively, of the 15 trials that measured blood lipid levels, six found significant improvement in treatment groups (in each case treatment was pharmacological). Reference Gierisch, Nieuwsma, Bradford, Wilder, Mann-Wrobel and McBroom32 Caemmerer et al conducted a meta-analysis focusing on effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions. Reference Caemmerer, Correll, Christoph and Maayan37 This medium-quality study showed treatment was associated with a significant improvement in insulin levels (three RCTs; weighted mean difference (WMD) −4.93 μIU/mL, P<0.001) and fasting glucose levels (six RCTs; WMD = −5.79 mg/dL, P<0.001). Reference Caemmerer, Correll, Christoph and Maayan37 Interventions were also significantly associated with improved profiles for total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglyceride levels, but the same was not found for high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol or systolic blood pressure. Reference Caemmerer, Correll, Christoph and Maayan37 A brief medium-quality review by Cabassa found 13 studies reporting metabolic risk measures, of which seven found statistically significant improvements in at least one physiological measure. Reference Cabassa, Ezell and Lewis-Fernandez41

Screening and monitoring of health parameters

We identified only one review meeting our criteria that looked at screening and/or monitoring of physical health parameters in people with SMI. Tosh et al found no trial reporting the effects of healthcare monitoring (either self-monitoring or by a healthcare professional). Reference Tosh, Clifton, Xia and White16 The low AMSTAR score for this review reflects the lack of data available on the impact on health outcomes of physical health screening in people with SMI.

Discussion

We sought to synthesise the current scientific evidence on interventions that may reduce excess mortality or improve physical health indicators of chronic disease in people with SMI. We evaluated the evidence relating to four broad intervention categories: mental health interventions, collaborative care interventions, interventions for risky lifestyle factors, and screening and monitoring of physical health parameters. Reviews suggest that psychiatric medications (antipsychotics and antidepressants) have some protective effect against excess mortality, but this is dependent on treatment adherence. Integrative community care programmes may reduce physical morbidity and excess mortality associated with SMI, but the effective ingredients of the interventions need to be identified. Interventions to improve risky lifestyle behaviours can reduce the profile of risk factors, but studies with long-term outcomes are lacking. Screening and preventive interventions and improved care in those with comorbid chronic disease are expected to reduce excess mortality, but there are currently no data available to support this. These findings highlight areas for policy, practice and research development. Below we explore the implications of our meta-review within the context of other research findings for each intervention category, taking into account a small number of studies post-dating the included systematic reviews.

Mental health interventions

We found the evidence on the effects of medication on mortality was equivocal. However, a number of trials published subsequent to these reviews suggest that antipsychotics and antidepressants may be effective in reducing excess mortality, but this is mediated by treatment adherence. Reference Cullen, McGinty, Zhang, dosReis, Steinwachs and Guallar45–Reference Scherrer, Garfield, Lustman, Hauptman, Chrusciel and Zeringue47 In Finland, Tiihonen et al found that long-term use (7–11 years) of any antipsychotic treatment was associated with lower mortality compared with no drug use (adjusted HR = 0.81, 95% CI 0.77–0.84). Reference Tiihonen, Lönnqvist, Wahlbeck, Klaukka, Niskanen and Tanskanen46 It has been noted, however, that methodological aspects of this study such as the exclusion of deaths occurring in hospital and the possibility of survivor bias mean these findings should be interpreted with caution. Reference De Hert, Correll and Cohen48 In apparent support of the findings from Finland, a recent study from North America by Cullen et al showed that those with most consistent adherence to antipsychotic medications had a 25% lower risk of excess mortality compared with those with the poorest adherence, after controlling for medical comorbidities. Reference Cullen, McGinty, Zhang, dosReis, Steinwachs and Guallar45 A study of antidepressant use found that depressed patients receiving 12 or more weeks of antidepressant treatment had decreased risk of all-cause mortality across all drug classes compared with those taking antidepressants for 0–11 weeks. Reference Scherrer, Garfield, Lustman, Hauptman, Chrusciel and Zeringue47 Effect sizes ranged from HR = 0.51 (95% CI 0.48–0.54) for serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) to HR = 0.66 (95% CI 0.62–0.71) for tricyclic antidepressants. Reference Scherrer, Garfield, Lustman, Hauptman, Chrusciel and Zeringue47

There are several pathways by which psychiatric medications may reduce risk of chronic disease and excess mortality. Medications can affect physical health directly through biochemical mechanisms and indirectly by reducing the duration and severity of symptoms. Although there are known cardiotoxic effects associated with some older antidepressants there is evidence that newer classes of antidepressants – specifically SSRIs and SNRIs – may normalise platelet activity, Reference Wozniak, Toska, Saridi and Mouzas49 improve cardiac risk markers, Reference Tecco, Monreal and Staner50,Reference Tseng, Chiang, Huang, Su, Lane and Lai51 and reduce the risk of cardiac events. Reference Scherrer, Garfield, Lustman, Hauptman, Chrusciel and Zeringue47,Reference Sauer, Berlin and Kimmel52–Reference Schlienger, Fischer and Jick54 Antidepressant medication may have a direct positive impact on biological factors shared by depression and cardiovascular disease, including overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, platelet activation and vasoconstriction. Reference Charlson, Stapelberg, Baxter and Whiteford55 For both antipsychotic and antidepressant medications mitigation of psychiatric symptoms may be important, because reduced severity of mental disorders leads to better health behaviours, such as reduced smoking and alcohol intake, Reference Strine, Mokdad, Dube, Balluz, Gonzalez and Berry56 and more proactive physical healthcare seeking. Reference Cullen, McGinty, Zhang, dosReis, Steinwachs and Guallar45 Comparison of long-term health outcomes at this stage, however, is obscured by heterogeneity in the drug class, Reference Von Ruden, Adson and Kotlyar21 and by underlying comorbidities and risk factors for chronic disease. Reference Smoller, Allison, Cochrane, Curb, Perlis and Robinson57

Integrative community care

Existing summaries of the literature on integrative community care programmes were unable to show a significant impact on excess mortality in treatment groups, although a general trend for reduced deaths was noted across studies. Study authors reported few deaths in either treatment or sample groups in the short periods of follow-up (median 18 months). The recently published Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT) provides support for the efficacy of integrative care management strategies when longer intervention and follow-up periods apply. Reference Gallo, Morales, Bogner, Raue, Zee and Bruce58 During 9 years of follow-up people with major depression, when allocated a mental-health specialist case manager to work with their regular general practitioner, were 24% less likely to have died, particularly from chronic disease, compared with those receiving usual care. Reference Gallo, Morales, Bogner, Raue, Zee and Bruce58 The use of integrative care models to improve physical health in people with SMI is burgeoning in countries such as Canada and the USA, and this has become even more important in light of the Affordable Care Act. Although preventing excess mortality has been used as a key rationale for these models, there is little information as yet on survival as an outcome. However, trials published subsequent to these reviews have demonstrated a range of other positive, short-term outcomes including improved cardiovascular risk profiles. Reference Druss, von Esenwein, Compton, Rask, Zhao and Parker35 A number of RCTs are currently under way to address physical comorbidity outcomes in SMI, including the serious mental illness Health Improvement Profile (HIP) study, the Improving Physical Health and Reducing Substance Use in Psychosis (IMPACT) therapy trial and the Health Outcomes Management and Evaluation (HOME) study. Reference White, Gray, Swift, Barton and Jones59–Reference Druss61

Taking into account our findings, together with other research, we recommend further work to identify the specific aspects of this approach that positively influence physical health. Researchers propose that the benefits of care management are probably multifactorial: clinicians may become more sensitive to changes in physical health outside the filter of the mental disorder diagnosis and patients may be more aware of health issues, have more frequent contact with health services and be primed to seek treatment; Reference Gallo, Morales, Bogner, Raue, Zee and Bruce58 however, evidence is lacking. Furthermore, as short-term research funding tends to preclude robust investigation of mortality as an outcome, researchers and funding bodies need to invest in longer periods of intervention and follow-up of health outcomes.

Interventions for lifestyle factors

Overall, our meta-review showed that interventions to improve risky lifestyle behaviours can reduce an individual's health risk profile. One major limitation of studies in this intervention category was the shortness of the follow-up periods. This is important for two reasons: first, it prevented us from drawing firm conclusions on the effectiveness of such programmes in reducing mortality, and second, the positive effects of lifestyle interventions tend to deteriorate over time for people with SMI as well as for the general population. Reference Kisely and Campbell44,Reference Allison, Newcomer, Dunn, Blumenthal, Fabricatore and Daumit62 Given the motivational difficulties associated with medication effects and psychopathology, the SMI group faces additional challenges in instituting lifestyle changes. Papers identified in these reviews suggest that more tailored approaches to treatment with continued proactive follow-up by usual mental health clinicians are likely to contribute to more prolonged long-term changes in healthy behaviours.

The 2011 British mental health outcomes strategy No Health without Mental Health sets out six objectives shared at all levels of community and government; it states one of its primary objectives as ensuring that ‘more people with mental health problems will have good physical health’. 63 However, the commitments made to achieve this reflect a passive approach, for instance improving nutritional standards in catering services, improving access to fitness facilities and developing alcohol and tobacco control plans. Given that the literature on lifestyle factors and collaborative care models suggests that proactive approaches tend to be more successful, these policies could be improved by integrating a component that ensured active follow-up by community service providers.

Screening and monitoring of health parameters

Screening, preventive interventions and improved physical healthcare for people with SMI and comorbid chronic disease are expected to reduce excess mortality, but there are currently no data available to support this. Nonetheless, available studies suggest there are inequities in terms of diagnostic timeliness, use of monitoring and provision of physical healthcare interventions; each is considered below along with possible explanations. Despite their increased exposure to chronic disease risk factors, many people with SMI have limited access to general healthcare with less opportunity for metabolic risk factor screening and prevention, Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist64 and lower rates of medical interventions than their counterparts in the general population. Reference Kisely, Smith, Lawrence, Cox, Campbell and Maaten65–Reference Mitchell and Lord68 Crump et al found that, despite their increased risk of mortality due to ischaemic heart disease (IHD) and cancer, people with schizophrenia were less likely to receive diagnoses of IHD, hypertension, abnormal lipid levels, cancer or liver disease compared with those without schizophrenia. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist64 After restricting the analysis to those previously diagnosed with chronic disease, schizophrenia was only modestly associated with IHD mortality and was no longer associated with cancer mortality. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist64 This in turn suggests that reducing the life expectancy gap for people with SMI also requires improvements in the coverage, timeliness and quality of physical healthcare for this group.

Although there is still insufficient information to determine a causal link, indirect evidence supports the hypothesis that mortality in people with SMI may be averted, to some degree, through ensuring better monitoring of physical health by mental health clinicians for chronic disease risk factors. Owing to the known relationship between atypical antipsychotics and metabolic disturbances, guidelines for screening and monitoring patients receiving these drugs have emerged over recent years, particularly in the case of clozapine. Reference Cohn and Sernyak69–Reference Hasnain, Vieweg, Fredrickson, Beatty-Brooks, Fernandez and Pandurangi71 However, uptake and compliance with these guidelines remains poor. Reference Mackin, Bishop and Watkinson72,Reference Morrato, Druss, Hartung, Valuck, Allen and Campagna73 There is no similar guideline for monitoring metabolic risk factors in patients not currently receiving medication or prescribed other drugs. The Service Framework for Mental Health and Wellbeing states that people with SMI should have an annual physical health check, preferably in primary care. 74 However, adherence to guidelines on screening and treatment of chronic disease is poor, and there is little information on why these barriers exist. Reference Mitchell, Delaffon, Vancampfort, Correll and De Hert75 Furthermore, the thresholds at which risk factor intervention is considered to be warranted are often determined by structured tools such as the QRISK2, which underpins the UK National Health Service health checks programme, and the Framingham coronary heart disease risk score, used in the USA. Reference Collins and Altman76,77 There is growing evidence, however, that these tools can underestimate chronic disease risk in those with SMI. Reference Osborn, Hardoon, Omar and Holt78 Trials are urgently required to identify why guidelines are not routinely applied in the case of people with SMI, the extent to which adherence to guidelines can affect health indices and outcomes, and the most appropriate screening tools and guidelines for patients with SMI.

Patients with SMI are also less likely to undergo standard surgical procedures or be prescribed medication for chronic disease compared with patients without mental disorders, Reference Kisely, Smith, Lawrence, Cox, Campbell and Maaten65–Reference Mitchell and Lord68 and this in turn supports a link between deficits in usual care and higher rates of mortality. Reference Mitchell and Lord68 It is difficult to tell the degree to which this is explained by patient or doctor behaviour, or both. Given the apparent efficacy of case management programmes in reducing IHD mortality, as reported above, it is likely that patient behaviours such as follow-up with healthcare professionals can improve treatment access and increase the likelihood of success of such interventions. However, it is also possible that doctors are reluctant to offer surgical intervention because of concerns about patient capacity or cooperation, comorbid conditions or risk of developing complications post-operatively. This is a valid concern, with higher documented rates of bleeding and septicaemia and 30-day mortality in patients with schizophrenia following surgery. Reference Liao, Shen, Chang, Chang and Chen10

Why might these patterns occur? Chronic diseases are underdiagnosed in people with SMI, and environmental factors such as lower socioeconomic status alone cannot account for this. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist64 Therefore an element of the mental disorder itself (i.e. behaviour of the patient) or barriers to provision of care are responsible for the underdiagnosis and treatment of physical disorders. Although mental health clinicians reported that primary care services should take responsibility for risk factor screening and management, people with SMI favour physical health screening by their mental healthcare providers. Reference Wright, Osborn, Nazareth and King79 Diffusion of responsibility for mental and physical health care is a major barrier to ensuring adequate care for people with SMI and this has implications for the collaborative management and delivery of healthcare services. Additional training of physical healthcare providers to reduce stigma and improve understanding of mental disorders, and of mental health clinicians on the importance of and delivery of care for physical healthcare conditions, and the communication and collaboration of all healthcare providers should be an important goal. The excessive specialisation of healthcare providers and lack of consensus over who should take responsibility for the general healthcare needs of patients with mental illness has resulted in a continuing failure to provide appropriate services. Reference De Hert, Dekker, Wood, Kahl, Holt and Moller80,81 In 2008 the World Health Organization pointed out that, despite the potential of primary prevention and health promotion to prevent as much as 70% of disease burden, resources continued to be targeted at the treatment of physical illnesses once they have already developed. 81 Given that individuals with SMI are more likely to develop chronic disease and experience poorer outcomes, this highly vulnerable group would reap substantial benefit from preventive actions such as screening, monitoring and prompt treatment for chronic disease risk factors. A first step in implementing this approach would be improving adherence to guidelines for monitoring physical health factors in those prescribed antipsychotic medications.

Strengths and weaknesses

Some limitations should be acknowledged when considering these findings. This is a synthesis of reviews, based on systematic reviews published between 2007 and 2014. It therefore did not include some published trials conducted since these reviews were published; however, we considered these when interpreting our findings and they did not alter our conclusions. A degree of judgement was required to classify some interventions into categories. This was because some reviews focused on an intervention strategy (e.g. general medical advice), even though it formed part of a broader programme, whereas others brought together studies where care was delivered through a specific platform (e.g. collaborative community care). The quality of the included reviews varied substantially. Apart from the screening and monitoring of health parameters, however, all categories contained at least two reviews of good to high quality (scores of 8 or higher out of a maximum of 11) and scored on average between 7 and 9. Because of the variability of intervention strategies, outcome parameters, follow-up periods and statistical analyses it was not feasible to conduct statistical analyses necessary for meta-analysis.

A number of reviews could not be included because studies reported behavioural change outcomes but not physiological outcomes, for instance those looking at cancer screening and smoking cessation programmes. Reference Kisely and Campbell44,Reference Barley, Borschmann, Walters and Tylee82–Reference Hartmann-Boyce, Stead, Cahill and Lancaster85 It may be that physiological outcomes are not measured in many cases owing to the length of time it would take for physical health changes to become apparent (for instance, in the case of smoking-related disease). However, to develop an evidence base around programmes that lead to improved health outcomes, physiological markers of change are required to enable us to draw a more direct link between interventions and reduced premature mortality. This gap in our evidence synthesis highlights the importance of longitudinal follow-up of intervention outcomes to permit collection of physiological outcome measures.

Study implications

The findings of this meta-review are important not only for practitioners but also for commissioners and policy-makers who set priorities and allocate resources. The health and financial implications of not intervening to reduce important causes of preventable deaths in people with SMI need recognition and remedy. The excess mortality rate is an important marker of general health among these people. The growing inequity in life expectancy, particularly due to heart disease mortality, underlines the need for better physical healthcare programmes for this group. Two areas that warrant immediate action are improving adherence to psychiatric pharmacological guidelines, and improving adherence to guidelines for monitoring metabolic health. There is an urgent need to improve the inequitable screening, monitoring and treatment of chronic disease in people with SMI. Research efforts should focus on filling major evidence gaps regarding the barriers to provision of physical health monitoring and elucidating the aspects of integrative community care programmes that have a positive impact on long-term health outcomes.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.