Introduction

Starting university can be an exciting time of change with new learning and the development of new social connections. It can also be challenging and stressful for many students. Some stressors affect both domestic and international students, such as workload and assessment requirements, while other stressors disproportionately affect international students, such as financial strain, language difficulties, and minority group status (Larcombe, Baik, & Finch, Reference Larcombe, Baik and Finch2022). Furthermore, international students commonly experience culture shock, loneliness, homesickness, and prejudice (Arkoudis et al., Reference Arkoudis, Arkoudis, Dollinger, Dollinger, Baik, Baik and Patience2019, Diehl, Jansen, Ishchanova, & Hilger-Kolb, Reference Diehl, Jansen, Ishchanova and Hilger-Kolb2018). In addition to these usual stressors, students’ transitions to university in early 2020 were disrupted when the COVID-19 rapidly became a global pandemic. Many countries attempted to halt the spread of COVID-19 by introducing international and national travel restrictions and mandating quarantine periods for foreign nationals. Many international students who planned to study abroad were not able to enrol (Ziguras & Tran, Reference Ziguras and Tran2020). For the students able to enrol, social distancing restrictions prompted an immediate shift to online learning. This meant that students were not able to attend classes in person or join social clubs and activities on campus. They had fewer opportunities to build relationships with staff and fellow students that naturally develop through informal conversations in class. Research conducted early in the pandemic indicated that such social restrictions led to increased student loneliness (Werner et al., Reference Werner, Tibubos, Mülder, Reichel, Schäfer, Heller and Rigotti2021) and particularly impacted first-year and younger students (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yang, Li, Ren, Mu, Cai and Zhou2021). This, in turn, may have resulted in higher levels of stress and mental health problems in the 2020 cohort.

The notion that social support can buffer against the effects of stress on mental well-being is not new (Cohen & Wills, Reference Cohen and Wills1985), although it remains unclear which type of social connections provides the most reliable stress-buffering effect (see Hare-Duke, Dening, de Oliveira, Milner, & Slade, Reference Hare-Duke, Dening, de Oliveira, Milner and Slade2019, for a review). In this study, we apply social identity theorising (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979) to argue that social group memberships and associated social identities are the basis for psychological resources (such as belonging, support, self-esteem, and so on) that protect mental health and well-being during stressful transitions (Draper & Dingle, Reference Draper and Dingle2021; Haslam, Jetten, Cruwys, Dingle, & Haslam, Reference Haslam, Jetten, Cruwys, Dingle and Haslam2018). The term ‘multiple-group memberships’ has been used in this literature to refer to group memberships with whom people identify — that is, those that are psychologically important and internalised as part of social identity (Jetten et al., Reference Jetten, Branscombe, Haslam, Haslam, Cruwys, Jones and Murphy2015). This could include social groups within and outside of the university setting such as family, friendship, educational/occupational, cultural, faith-based, and extra-curricular groups. Previous research has established that the multiple-group membership is associated with increased self-esteem in a range of populations (Jetten et al., Reference Jetten, Branscombe, Haslam, Haslam, Cruwys, Jones and Murphy2015) and better adjustment in first-year university students (Iyer, Jetten, Tsivrikos, Postmes, & Haslam, Reference Iyer, Jetten, Tsivrikos, Postmes and Haslam2009). Most relevant among university students’ group identities is their university identity.Footnote 1 This sense of belonging at the university and connecting with fellow students is protective of student well-being (Knox, Crawford, Kelder, Carr, & Hawkins, Reference Knox, Crawford, Kelder, Carr and Hawkins2020) and academic outcomes (Zumbrunn, McKim, Buhs, & Hawley, Reference Zumbrunn, McKim, Buhs and Hawley2014). On the other hand, students who lack group memberships and have a weaker sense of belonging at the university are prone to loneliness, which is associated with poorer mental health outcomes such as increased anxiety, depression, and stress (Diehl et al., Reference Diehl, Jansen, Ishchanova and Hilger-Kolb2018).

This study thus aimed to evaluate the impact of the pandemic on social connections and mental health in first-year students. We compared data collected from students starting university in Australia across three cohorts: 2019 (pre-pandemic); 2020 (the first wave of COVID-19); and 2021 (after some restrictions had been lifted). We hypothesized that (1) the first wave of the pandemic (2020) would increase loneliness and decrease university belonging and multiple-group memberships compared to the 2019 and 2021 cohorts; (2) this effect would be greater for international than domestic students; (3) loneliness would be associated with a higher number of causes of stress, higher psychological distress symptoms, and lower well-being, and conversely, and (4) university belonging and multiple-group memberships would be associated with a lower number of causes of stress and psychological distress and higher well-being.

Methods

Design and Participants

The study involved 1239 students across the three cohorts and used a 2 (enrolment: domestic and international students) × 3 (cohorts: 2019, 2020, 2021) between-groups design.

Measures

Loneliness

The Three-Item Loneliness Scale (Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, Reference Hughes, Waite, Hawkley and Cacioppo2004; α = .83 in our study) adapted from the UCLA Loneliness Scale. Participants answered items such as ‘how often do you feel left out?’ on a three-point scale from 1 = hardly ever to 3 = often. The item scores are summed to create a total score in the range of 3–9, and scores of 6 and above are a positive screen for loneliness.

University belonging

A single-item measure ‘I identify with students at the University of Queensland’ was adapted from the single-item social identity scale, which has been established as a valid and reliable measure of social group identification (Postmes, Haslam, & Jans, Reference Postmes, Haslam and Jans2013). The term ‘identify with’ was changed to ‘feel a sense of belonging’ to ensure that international students could fully understand the item. This item was rated on a five-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Multiple-group memberships

A two-item version of measurement was adapted to investigate social support in the form of different group memberships (Jetten, Haslam, Pugliese, Tonks, & Haslam, Reference Jetten, Haslam, Pugliese, Tonks and Haslam2010). Items such as ‘I belong to lots of different groups’ and ‘I am friendly with people in lots of different groups’ (r = .55, p < .001, α = .71) were rated on a five-point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, and averaged to create a score in the range of 1–5, with higher scores indicating stronger social support from groups.

Number of causes of stress

Six-items assessing common causes of stress for young people were adapted from the Stress and Well-being in the Australia Survey (Casey & Liang, Reference Casey and Liang2014, α = .71 in our study). Examples included the following: financial issues, friendship issues, the environment and climate change, and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Four additional items (α = .68) were added to assess academic tasks that can cause stress for students: speaking up in class, giving a class presentation, group assignments, and preparing for exams. Participants rated their agreement that each item caused them stress on a five-point scale: 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. A sum of items that participants rated 4 or 5 will be computed as the total number of stressors (out of 10 listed).

Well-being

The seven-item Short Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS, Haver, Akerjordet, Caputi, Furunes, & Magee, Reference Haver, Akerjordet, Caputi, Furunes and Magee2015, α = .84 in our study) assessed students’ mental well-being. Positively worded items included ‘I have been feeling useful’. Participants rated the frequency of symptoms over the last 2 weeks on a five-point scale from 1 = none of the time to 5 = all of the time. The sum of the scores was calculated with higher scores representing better mental health.

Psychological distress

The 20-item PsyCheck Screening measure (Jenner, Cameron, Lee, & Nielsen, Reference Jenner, Cameron, Lee and Nielsen2013, α = .88 in our study) assessed mental health including somatic symptoms, in which research indicates to be relevant to many international student presentations. Participants responded ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ to questions asking whether they have experienced various physical and psychological symptoms in the last 30 days. Example items are ‘do you often have headaches?’ and ‘do you feel unhappy?’. Endorsed items are summed to a score of 20, and a score of 5 and above indicates a positive screen indicating a need for further assessment and management of mental health issues.

Procedure

The survey was developed in consultation with an international student administrator and a group of international students. The survey was advertised as a ‘University Student Wellbeing Project’ and was open to any student enrolled in a first-year course at the university. There were no other inclusion or exclusion criteria. Recruitment occurred via several purposive sampling methods, including advertising through talks given to large first-year lectures, advertising on student social media sites, and advertising on the university research participation scheme. After giving informed consent, participants were given access to the anonymous survey online. Following completion, participants were presented with debriefing information about the study and the choice of obtaining a course credit (for first-year Psychology students) or entering a prize draw to win a $30 voucher. All methods were approved by the institutional ethics committee (2019/HE001150).

Results

A total of 1239 students were recruited across the three cohorts. The proportion of participants of each gender, citizenship/cultural category, relationship status, and living situation category is shown in Table 1. Although between-cohort analyses of demographics were not in the scope of the study, it is clear from Table 1 that a greater proportion of students were domestic in 2020 and 2021 than in 2019 due to the impact of COVID-19 on international students’ enrolments. Also, a larger proportion of students were living at home with family in 2020 and 2021 than in 2019.

Table 1. Participant Characteristics of Australian First-Year University Students in the 2019–2021 Cohorts

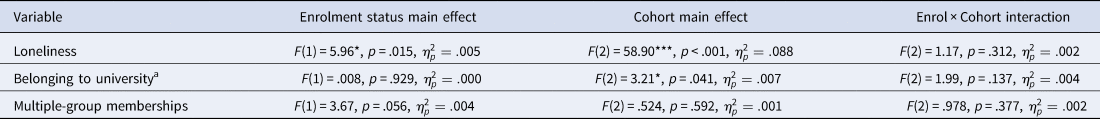

To test the hypotheses (i and ii), a series of 3 (cohorts: 2019, 2020, 2021) × 2 (enrolment status: domestic, international) analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed on the following three outcomes: loneliness, university belonging, and multiple-group memberships (see results in Table 2). There was a main effect of cohort on loneliness, and least significant difference (LSD) post-hoc tests confirmed that loneliness in the 2020 cohort (M = 6.25, SD = 1.78) was significantly higher than that in 2019 (M = 5.83, SD = 1.78, p = .001) and in 2021 (M = 4.77, SD = 1.63, p < .001) (Figure 1a). Additionally, loneliness in the 2019 cohort was also significantly higher than that in the 2021 cohort (p < .001). This pattern was consistent with hypothesis (i). There was also a main effect of enrolment status on loneliness in the opposite direction to our hypothesis (ii), where domestic students reported higher loneliness than international students in all cohorts. There was no interaction between cohort and enrolment status.

Figure 1. Level of loneliness (a), university belonging (b), multiple-group memberships (c), numbers of stressors (d), psychological distress (e), and well-being (f) for first-year domestic and international students at a metropolitan university in Australia in 2019–2021.

Note: In 2019, questions related to university belonging were only shown to respondents who had relocated to attend university (N = 100 domestic, N = 88 international students). All respondents in 2020 and 2021 were shown this variable. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Table 2. Results of 3 (Cohorts: 2019, 2020, and 2021) × 2 (Enrolment Status: International and Domestic) ANOVAs on Loneliness, Belonging to University, and Multiple-Group Memberships

Note: aIn 2019, these questions were only shown to respondents who had relocated to attend university (N = 100 domestic, N = 88 international students). All respondents in 2020 and 2021 were shown as variables.

*p < .05; ***p < .001.

In a similar pattern to the loneliness results, a main effect of cohort was found on university belonging (Figure 1b). The LSD post-hoc test confirmed that the 2020 cohort (M = 3.22, SD = 1.08) had a significantly lower sense of belonging to university than their 2019 (M = 3.47, SD = 0.96, p = .004) and 2021 counterparts (M = 3.39, SD = 0.93, p = .015). There was no difference between the 2019 and 2021 cohorts. There was no main effect of enrolment status and no interaction between cohort and enrolment status for university belonging. For multiple-group memberships, there were no significant effects of cohort or enrolment status (Figure 1c).

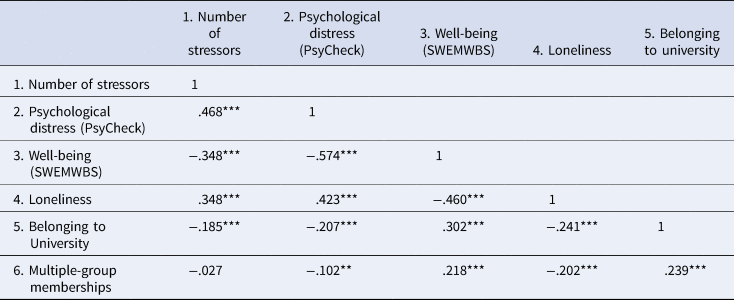

To test hypotheses (iii and iv), Pearson's correlations were conducted between the loneliness, sense of belonging to the university, and multiple-group memberships with the mental health measures (number of stressors, psychological distress symptoms, and well-being) (Table 3). In line with the hypothesis (iii), loneliness was correlated with a higher number of stressors, a higher number of mental health symptoms on the PsyCheck, and lower well-being on the SWEMWBS. Supporting hypothesis (iv), higher university belonging was correlated with fewer causes of stress, lower psychological distress, and higher well-being, whereas multiple-group membership was correlated with lower psychological distress and higher well-being. Also, university belonging was positively related to multiple-group memberships and negatively related to loneliness.

Table 3. Correlations Between the Number of Stressors, Psychological Distress, Well-Being, Sense of Belonging to the University, Loneliness, and Multiple-Group Memberships in First-Year Students From 2019 To 2021 Cohorts (1239 Students in Total)

Note: **p < .01; ***p < .001.

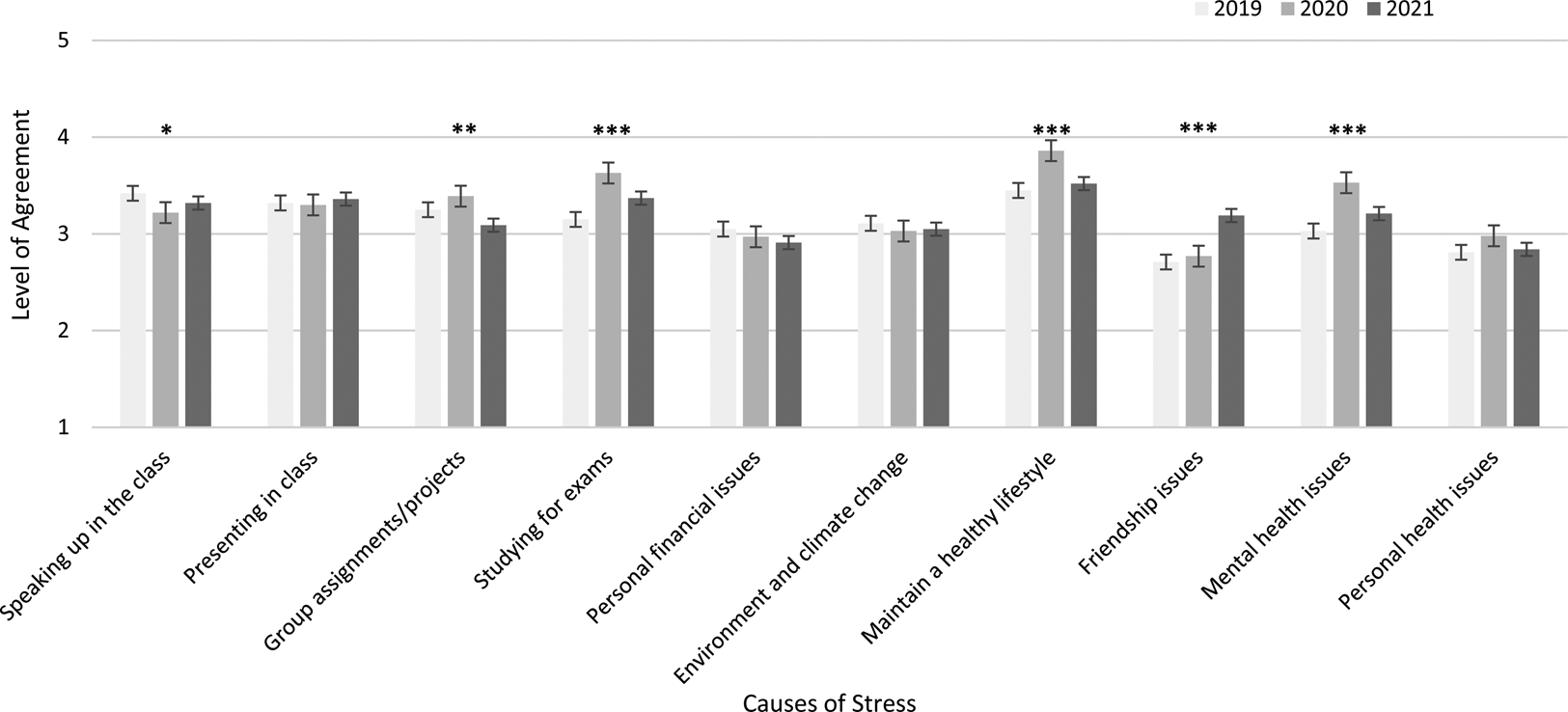

Although this was not part of a specific hypothesis, we explored whether there were significant cohort differences in the types of stressors experienced by the students (Figure 2). One-way ANOVA results showed that among the 10 causes of stress, the cohorts were significantly different in three academic stressors: speaking in class [F(2, 1235) = 3.25, p = .039], group assignments [F(2, 1234) = 6.99, p = .001], and studying for exams [F(2, 1234) = 17.45, p < .001]. Also, significant cohort differences were found in general stressors such as maintaining a healthy lifestyle [F(2, 1234) = 19.69, p < .001], friendship issues [F(2, 1234) = 20.63, p < .001], and mental health issues [F(2, 1233) = 17.90, p < .001].

Figure 2. Causes of stress for first-year university students in 2019–2021.

Note: Rated agreement from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Discussion

The results of this study broadly supported our hypothesis that the move to online learning in the context of COVID-19 social distancing and lockdowns would have a detrimental impact on students’ social connectedness. This was shown in the substantial increase in loneliness seen in 2020 compared to either the pre-pandemic cohort in 2019, or the 2021 cohort when a higher proportion of students were living at home with their families and some restrictions were eased. Our results for loneliness are consistent with those reported in other student studies (Werner et al., Reference Werner, Tibubos, Mülder, Reichel, Schäfer, Heller and Rigotti2021; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Yang, Li, Ren, Mu, Cai and Zhou2021). The reduced opportunities to connect with staff and fellow students during the pandemic was further reflected in the decreased sense of university belonging reported by students in the 2020 cohort compared with the two other cohorts. Unexpectedly, cohort-related differences were not seen in the multiple-group membership measure. This measure was likely to have captured group supports outside of the university, such as friends, family, and other existing groups, which appear to have been less negatively affected by the onset of the pandemic.

Contrary to our second hypothesis, international students reported less loneliness than the domestic students. This may be due to the higher average age of the international students in the pre-COVID cohort (i.e., they may have higher confidence and stronger existing social networks) and the greater proportion of international students living at home with family in the 2020 and 2021 cohorts. Our findings are consistent with another study of international students that found that students whose familial and existing peer supports were maintained during the pandemic showed better adjustment when starting university (Wilczewski, Gorbaniuk, & Giuri, Reference Wilczewski, Gorbaniuk and Giuri2021). The finding that domestic students reported high levels of loneliness highlights that the period between finishing school (or work) and starting university is a key point of social transition and disconnection. Some students may start university with a network of friends from secondary school but that is not the case for all students. Students who move to metropolitan universities from rural or regional areas or are from working class backgrounds and/or are the first in their families to attend university are typically not as well connected socially when they enter university. These students may be disadvantaged in terms of forming a university student identity and sustained well-being (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Jetten, Tsivrikos, Postmes and Haslam2009).

Indeed, in our study, loneliness, and conversely, low university belonging and a lack of multiple-group memberships, was related to a range of negative effects including a greater number of causes of stress, more symptoms of psychological distress, and lower well-being. These results echo findings in earlier research in university students (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Fang, Hou, Han, Xu, Dong and Zheng2020; Werner et al., Reference Werner, Tibubos, Mülder, Reichel, Schäfer, Heller and Rigotti2021) and in broader studies on social groups, identities, and health (Haslam et al., Reference Haslam, Jetten, Cruwys, Dingle and Haslam2018). These findings emphasise the importance of organising meaningful social group activities for university students where they share goals and can develop friendships. According to the social identity theory, group memberships are better placed than other interventions (e.g., peer support, befriending programmes, or individual counselling) to address loneliness and university belonging because we internalise our important group memberships — ‘I'm a University of Queensland student’ or ‘I'm a member of the Humanities Students Association’ — in a way that does not occur in individual relationships (Haslam et al., Reference Haslam, Jetten, Cruwys, Dingle and Haslam2018). Furthermore, on a practical level, a group exists even if one member is unavailable, whereas in an individual relationship all of the social resources rely on the availability of one person.

The authors believe that responsibility for student well-being can be shared between the students themselves, the lecturing staff, and the university administration. Students can take a proactive role in protecting their mental health by finding out where to access help for health and well-being, and by engaging in simple strategies such as socialising with others, eating well, sleeping well, physical activity, study skills, and emotion regulation — particularly in group contexts with other students (Dingle et al., Reference Dingle, Hodges, Hides, McKimmie, Gomersall, Beckman and Alhadad2022). Some research indicates that university students believe that teachers play an influential role in their well-being through being available and supportive and by demonstrating competence and passion for their work (Eloff, O'Neil, & Kanengoni, Reference Eloff, O'Neil and Kanengoni2021). Finally, the university administration can play a role in developing and resourcing university-wide policies that support the development of connections between teaching staff and students, and among students. Examples might include collaborative projects where teams of staff and students work together towards a shared goal that strengthens their disciplinary identity. This could also involve extra-curricular activities such as team sports, trivia or games nights, a departmental band, or choir (e.g., Pearce et al., Reference Pearce, Launay, van Duijn, Rotkirch, David-Barrett and Dunbar2016). Of course, there may be challenges to getting students to join groups if they are already experiencing loneliness. The research is only just beginning to identify these challenges, which include a lack of fit with the group, a lack of confidence (Stuart, Stevenson, Koschate, Cohen, & Levine, Reference Stuart, Stevenson, Koschate, Cohen and Levine2022), low self-worth, fear of being judged by others, and mistrust of others (e.g., Ingram, Kelly, Deane, Baker, & Dingle, Reference Ingram, Kelly, Deane, Baker and Dingle2020). In some cases, a combination of individual therapy to help students overcome such barriers as well as group-based activities would be recommended.

Our study had some limitations, such as the use of cross-sectional data collected at three time points from different participants rather than a repeated-measure experimental design (i.e., the same participants assessed at the three time points). Correlations cannot say anything about the direction of relationships or dynamic changes over time in the variables of interest. A stronger test of our conceptual model would examine the relationship between social group connections and mental health, mediated by psychological resources (such as support). However, this would require data collected from participants at three time points (O'Laughlin, Martin, & Ferrer, Reference O'Laughlin, Martin and Ferrer2018). Furthermore, our study was conducted at a single metropolitan university, so replication at universities in other cities and in regional Australia is required to ensure that the findings are externally reliable. A strength of this study is that we were in the fortunate position of having collected data on the variables of interest prior to the onset of the pandemic. This provided a valid baseline to compare the pandemic cohort data against (whereas most other longitudinal studies have only been able to collect data after the pandemic started).

In summary, the study found that first-year students experienced lower university belonging and higher loneliness during the pandemic and this was detrimental to their mental health. The findings emphasise a need for initiatives that promote student connectedness and prevent mental health problems as the university sector recovers from the effects of COVID-19. The findings underscore the fact that most students do not enrol in university just to learn; they enrol to learn together.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants and the international student advisors for their involvement in this study. We are grateful to Mengxun Hong, Dianna Vidas, and Shaun Hayes for their assistance with the surveys and data collection.

Funding

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council (grant no. LP180100761).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.