1. Rethinking peasant vulnerability and resilience

In the last few years, public concern over sustainable development, food security, and peasant and indigenous rights has pushed community lands back on the global development agenda.Footnote 1 Recent findings estimate that local and indigenous communities hold up to 65 per cent of the world's land area under customary systems.Footnote 2 Although no reliable quantifiable information exists on how collective lands are distributed among different types of rural communities, a significant proportion of these lands are managed by what we can define as peasant communities.Footnote 3 Ground-breaking economic and historical research has underscored the cohesive role of common pool resource governance in communities’ strategies to deal with uncertainty and disasters.Footnote 4 These insights have led policy-makers and researchers alike to explore community lands as local buffers to ward off the effects of climate change and biodiversity loss at a regional and global level.Footnote 5 However, policy responses to secure those buffers are often translated into a technological and institutional ‘fix’ aimed at solving contemporary moments of turbulence. We argue that the efforts of making a case for community lands as part of a global strategy for sustainable development and climate resilience lack a deeper historical understanding of sustainability in general and of the resilience of communal institutions in particular.

This paper presents a research strategy to critically assess vulnerability and resilience in peasant communities not as a mere outcome, but as a constitutive element of trajectories of peasant transformation. We unpack processes of vulnerability and resilience within peasant communities in the context of centralising land regimes and globalising commodity markets. Peasant communities’ resilience is the outcome of a historical balancing between autonomy and participation within an encroaching market-based world-economic system.Footnote 6 To grasp this versatile relationship we centre our research strategy on the notion of frontier. Frontier and frontier zones serve as powerful analytical tools to elucidate how capitalism as an historical system has been able to persist by only partially incorporating its social and ecological costs. The notion of peasant frontier refers to the historical processes of social and spatial reorganisation of rural communities and to the incomplete appropriation of the supplies of nature, land and labour that they control.

The reproduction of common land rights in a context of political and commercial integration is a prime expression of the reorganisation of the peasant frontier. To illustrate this, we compare two distinct peasant communities that relied upon common land rights during periods of profound social change and stress, particularly related to the attempted commodification of rural land. We selected two case areas where peasant communities displayed a relatively strong continuity in common land rights management while being integrated in expanding market networks. These communities deployed common land rights as an economic or political negotiation tool and as a strategy of survival and adaptation to mounting demographic, economic and ecological pressures. As we argue in this paper, we focus on two cases in distinct parts of the world to substantiate our argument that these specific frontier processes have a world-historical significance. Given the regional expertise of our research team, we focus on peasant communities in Western Europe and Latin America.

The selected cases focus on the preservation and transformation of communal land tenure practices in eighteenth-century Ardennes in the Southern Low Countries (contemporary Belgium), and in nineteenth-century Carangas on the Andean high plateau of Bolivia. These two empirical cases of communal land systems and their responses to intensifying pressures of commodification expose the diverse stance of peasantries toward the management of land and to rural change in general. Rural communities in both areas had a strong communal land base compared to neighbouring regions where common land rights had been severely weakened or had already disappeared. While both regions were remotely located from major urban centres and markets, they comprised local and regional economic centres and were embedded in interregional trade and transport networks. We challenge the assertion that the exceptional trajectory of both cases, safeguarding common land rights while these disintegrated in surrounding regions, can be explained exclusively by their remote location and marginal connection to markets, and by a distinct ecology of forests and semi-arid pasturelands.

Instead of a classic comparative approach, we selected two cases in a different time frame and regional setting, tied together within an analytical framework to assess temporal and spatial variations in global social change. This way we are able to demonstrate a more complex story in which the continuity or dissolution of local common land systems do not simply derive from pre-existing landscape conditions or state and market interventions. We argue that the rural communities in the Ardennes and Carangas employed their common land systems as strategies of resistance and adaptation to the rising pressures of the commodification of land rights. Hence, these communities actively shaped the local materialisation of capitalist expansion in seemingly peripheral regions. New empirical research demonstrates that communal control over resources presents far from a linear story; it is the product of shifting community strategies and internal power relations. Wherever you look, the struggles about common land rights expose peasant strategies of adaptation and resistance; they expose the peasant frontier at work.

In the next section, we unpack our approach towards peasant transformation within a context of a growing impact of state and market forces. We introduce the concept of peasant frontier as an analytical tool for world-historical research to critically assess concepts of social vulnerability and resilience. In the third section, we explore the peasant frontier through the reproduction of communal land rights in two case studies. By juxtaposing the historical trajectories of peasant communities of the Low Countries and the Andes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, we demonstrate how the renegotiation and diverging deployment of common land rights was part and parcel of strategies of peasant resilience.

2. Understanding peasant transformation through peasant frontiers

The standard narrative of peasant transformation confronts us with the flaws of traditional development theories that frame ‘the end of peasantries’ as a temporary phase in the inevitable transition towards a capitalist world.Footnote 7 Agrarian change and peasant transformation became moulded in dichotomous and largely a-historical models. However, a myriad of studies on rural societies shows time and again that the transformation of agrarian and peasant societies cannot be predicted from linear models or environmental, demographic or evolutionary contexts. Although many European peasant societies dissolved within expanding industrial and welfare economies, recent historiography has shown that these experiences do not prescribe a general trajectory for the global countryside.Footnote 8 Recent development policies have re-evaluated the position of peasant societies, amongst others by incorporating communal resilience and common land rights to promote sustainability as a global ambition. However, this remains problematic for at least two reasons. First, as Tim Soens has argued, discussions on vulnerability and resilience too often adopt a macro approach on the level of societies and systems.Footnote 9 By contrast, in this paper we take the position that vulnerability and resilience must be understood in the first place on the level of local and trans-local communities.Footnote 10 Vulnerability and resilience are characteristics not of systems but of communities, linking the question of sustainability to social and ecological inequalities. That is why we talk about vulnerability and resilience within communities, taking into account unequal power relations and skewed access to natural resources, and to means of production and consumption.Footnote 11

A second objection to reductionist global approaches is that they tend to confine the problem of competing interests over land, resources and nature to issues of ‘property’ and ‘security’. As De Schutter and Rajagopal have stated, this response problematically ignores how grassroots land struggles continuously question the very institution of property itself.Footnote 12 We understand declining local resilience or diminishing adaptability of communities to crises within a context of proliferating capitalist production relations that become manifest, amongst others, in asymmetric processes of commodification of land and the establishment of private property rights. Increasing peasant vulnerability is part of the capitalist transformation of the countryside, and cannot be overcome by external ‘institutional fixes’ forged around an univocal definition of property. Communal practices of access to, and use and control of land are rooted in multiple forms of self-governance that defy and exceed a neat division between private and public, and individual and collective property.Footnote 13 This paper approaches the wide array of communal land practices that still exists today not as a remnant of the past but as the outcome of a long messy history of participation, negotiation, resistance and reinvention within an increasingly interconnected world.

A long tradition of bottom-up research demonstrates that peasant histories can only be understood within a wide variety of reciprocal exchanges and redistributions, regional and extra-regional market transactions and public retributions. Andean ethnohistorical scholarship for example has drawn attention to the ways in which Andean rural populations coped with and mediated colonial and post-colonial market and state transformations rather than undergo them.Footnote 14 The study of everyday practices reveals how peasants, by participating in markets without completely assimilating to these spheres of exchange, at the same time exerted a form of resistance against the market.Footnote 15 These and many other stories challenge historical determinist narratives of global capitalist forces restructuring colonial hinterlands, however without ‘implicitly celebrating Andean commercial ingenuity (the homo economicus of the mountains) or reifying peasant resistance.’Footnote 16 In recent times and closer to the cradle of orthodox Western development thinking, we equally observe transformations that challenge linear models, for instance in the emergence of ‘new peasantries’ in twenty-first-century Europe through a diversity of old and new coping and resistance strategies.Footnote 17

The question of access to land remains central in these debates. For peasantries, land has been and still is the primary basis of negotiation and interaction with other sectors of society because its use has direct implications for their exchange and power relations.Footnote 18 Just like the struggles for indigenous rights, peasant claims to land, territory and resources usually have a communal rather than an individual nature. The combination of safeguarding a minimum of autonomous control over vital resources and securing a minimum of involvement in broader socio-political structures accounts for the peasant communities’ multifaceted, apparently contradictory, but above all, alert attitude towards incorporation processes. The reproduction of communal logics and practices has allowed peasantries to develop divergent repertoires of accommodation, adaptation and resistance to market and state integration. These strategies triggered different processes of peasantisation, de-peasantisation and re-peasantisation across the world and across time.

Understanding these multiple trajectories of peasant transformation requires new historical knowledge about the role of peasantries and peasant community organisation. Throughout its development over the past 600 years, global capitalism generated growing social and ecological costs, and put increasing pressure on its peripheries, including indigenous and peasant societies. This has prompted historians to revisit agrarian movements through an environmental lens and a frontier perspective.Footnote 19 Frontiers have emerged as an analytical device in the work of historians and social scientists to rethink how societies coped with environmental scarcities or crises.Footnote 20 Environmental historian and historical geographer Jason W. Moore made a crucial intervention in the debates on capitalism by defining it as a world-ecological system.Footnote 21 The rise of capitalism has instigated a radical new way of organising land and nature, by mobilising new inputs of labour and energy to fuel the rise of labour productivity. This could only occur to the extent that new bundles of uncapitalised nature, work, and energy were mobilised and secured through successive waves of incorporation and appropriation. This resource-driven growth enabled the internalisation of new spaces for the appropriation of new inputs and the externalisation of new costs. Thus, frontiers are not fixed geographical places but socio-ecological relations ‘that unleash a new stream of nature's bounty to capital: cheap food, cheap energy, cheap raw materials, and cheap labour.’Footnote 22 As the limits of social, economic and ecological resilience are challenged, frontiers continually shift in time and space, providing new sources of nature, land and labour, creating new supplies, reducing production costs and increasing profitability. Local activities are reorganised to secure access to labour and land, and to facilitate the extra-local production of agricultural, forest and mineral commodities. The sites where this happens become frontier zones; mobile and mutable constructs, where a new order is created of which the outlook is still wavering. Frontiers reflect the irregular rhythm of historical capitalism; how its ‘profit-centred rationality’ is being ‘contaminated, consolidated, and continuously interrupted by other logics.’Footnote 23 Cumulative processes of incorporation put in motion escalating waves of spatial expansion and societal reorganisation in search of new reserves of labour, land and nature.Footnote 24 The multiple actions of negotiation and contestation within these frontier movements emphasise agency outside core regions, and challenge the image of the margins as either disconnected or passively assimilated vis-a-vis state and market dynamics.Footnote 25

Throughout history, peasant communities have been a central space for organisation, self-determination, negotiation and resistance, and they have been the gateway to larger and incorporative systems. The frontier concept demonstrates the diversity and unevenness within an apparently singular and teleological transformation of the global countryside. It addresses the paradoxical nature of capitalist expansion and peasant resilience, which this article exemplifies by examining the reproduction of communal land rights and land management practices in two distinct regions since the mid-eighteenth century.

The rights to access and to use land have been determinative in peasants’ frontier position and the ability to ensure their survival within a capitalist world-ecology. Capitalism as an historical process thoroughly reshuffled labour, legal, fiscal and spiritual ties to the land, separating people living from the land, from people living from the property of the land.Footnote 26 Enclosure processes increasingly incorporated rural zones into larger political and economic frameworks, especially from the eighteenth century onwards. The outcome is a modern private property regime that links land to capital and that is consolidated and expanded through state power.Footnote 27 As a result, land rights remain a major point of friction between state authorities and peripheral groups that manage their land under communal systems, at the same time defying universal aspirations of private property. A frontier perspective reveals how common lands have always been hybrid social spaces, both in relation to nature and to forces that promote land rights commodification. Communal practices did not survive through isolation or expulsion, but have been shaped by communities’ participation in expansive state and market processes. As Diez has stated, these institutional formations are in constant change, they ‘are transformed while they remain.’Footnote 28 In the words of Peluso and Lund, communal land systems are the product of the constant (re)creation of ‘new frontiers of land control,’ which ‘are sites where authorities, sovereignties, and hegemonies of the recent past have been or are currently being challenged by new enclosures, territorialisations, and property regimes.’Footnote 29

3. Vulnerability, resilience and the reproduction of common land rights in peasant communities in the Low Countries and the Andes

Instead of comparing two cases situated in the same time and/or regional frame, we draw on an innovative take on the classic comparative approach. By pairing two case studies set in substantially different regions and historical contexts, we bring together diverse geographies and chronologies of a common global phenomenon. This method of ‘incorporated comparison’ was coined by Philip McMichael to compare specific cases as ‘relational parts of a singular (historically forming) phenomenon.’Footnote 30 We juxtapose distant places and moments within a shared world-historical transformation, the commodification of land rights. Through this single historical project, different periods and regions become conceptually interconnected. A well-known example of this method is Harriet Friedman's and Philip McMichael's use of the concept of food regime to juxtapose contemporary globalisation to the free trade rule in nineteenth-century British imperialism.Footnote 31

The commodification of land rights, as a concrete expression of capitalist expansion in rural territories, proceeds through spatially and temporarily uneven and divergent trajectories of peasant incorporation. Araghi and Karides unpack this process as the emergence and convergence of standardised land rights regimes, based on the principle of state-guaranteed land ownership.Footnote 32 Tracing this process back over five centuries, they identify the formalisation, fixation, rationalisation and privatisation of land rights as its key drivers. The diffusion of Western notions of private property rights accelerated from the eighteenth century when private property became directly associated with agricultural modernisation and productivity progress, while common lands and rights were explicitly targeted as harmful.Footnote 33 The perceived incompatibility between private and collective property led to the promulgation of land reforms and new legislations that aimed to speed up the commodification of land rights.Footnote 34 These efforts first materialised in Europe, as we will see in the Ardennes, and later, in the second half of the nineteenth century, in Latin America, as we will illustrate with the case of Carangas. On paper, land reforms subjected land to the law of value, but in practice financial constraints, disagreement among local authorities and popular unrest in rural societies thwarted that ambition.Footnote 35 The attempted erasure of plural customary land systems across Latin America, just as in several parts of Europe, was contested by the landlord class as well as by rural communities. While in some cases leading to protracted violence, diverse opposition tactics often managed to hinder the restructuring of local land systems and the organisation of a more standardised land market. As a result, the enclosure of communally held lands both in Western Europe and in Latin America materialised in a fluctuating movement between failure and success.Footnote 36

The study of rural societies in the Ardennes and Carangas is rooted in a long and rich research tradition on local peasant communities and their land rights in the Low Countries and the Andes.Footnote 37 Yet, until today, there exists little dialogue between both research traditions. By developing an incorporated comparison of two case studies on common land rights, we integrate these seemingly distinct research traditions within a global approach, demonstrating how a world-historical transformation in land rights commodification is woven together by disparate but comparable historical trajectories. Generally depicted as remote from commodity markets and state power, peasants in both areas participated intensely in expanding markets and actively confronted new demographic, socio-economic and political challenges, while pragmatically relying on (and reinventing) common land rights. In both cases, common land systems were deployed as a resilience strategy in times of crisis and stress, a strategy that pushed the reconfiguration of internal social power relations.

3.1 The reproduction of common land rights in eighteenth-century Ardennes

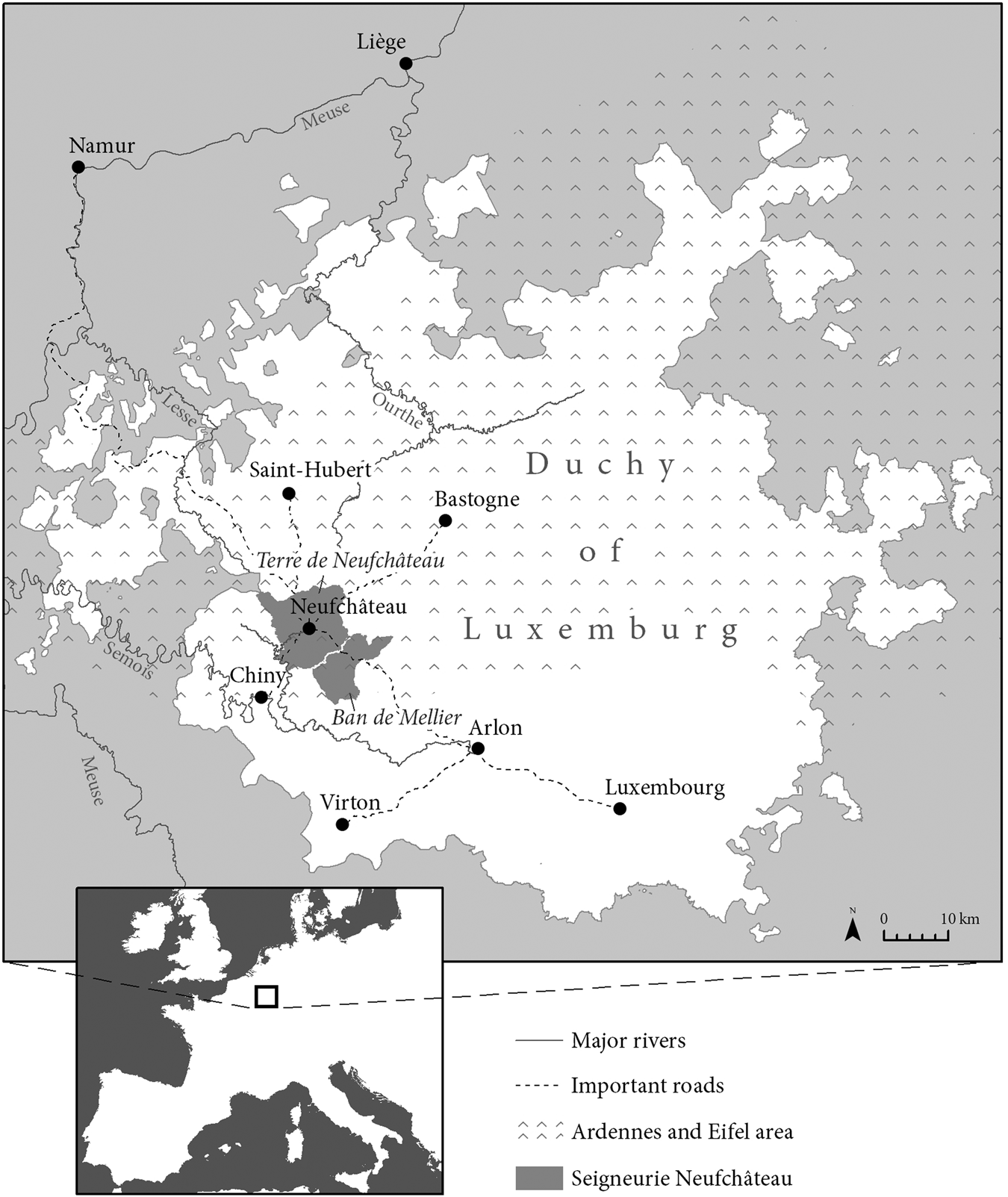

This case study relies on in-depth research on the seigneurie of Neufchâteau, an area that boasts all the typical characteristics of the regional agro-system of the Ardennes (Figure 1).Footnote 38 The eighteenth-century property regime differed substantially from that of Flanders and other well-studied regions of the Low Countries.Footnote 39 The most distinctive characteristic was that a major part of the income of local peasants came from land that was used in common for at least part of the year. This strong communal character was central to the role of the Ardennes as a driver of international livestock trade and supplier of wood resources for industrialisation and urbanisation.Footnote 40

Figure 1. Map of the Duchy of Luxemburg in the second half of the eighteenth century showing the region of the Ardennes and the seigneurie of Neufchâteau.

Source: Map designed by Hans Blomme (UGent) and based on F. Mirguet, Le duché de Luxembourg à la fin de l'ancien régime: Atlas de géographie historique, I, Introduction (Louvain-la-Neuve, 1982); C. de Moreau de Gerbehaye et Pierre Hannick, Le duché de Luxembourg à la fin de l'ancien régime: Atlas de géographie historique, VI, Le quartier de Neufchâteau (Louvain-la-Neuve, 1989).

Before the administrative reforms instigated by the French occupation in 1795 and the region's integration in independent Belgium in 1830, the seigneurie of Neufchâteau was located near the southern borders of the Southern Low Countries in the Duchy of Luxemburg, which belonged to the Austrian Empire in the eighteenth century. With the Eifel mountain range in Germany as its eastern extension, the entire area constitutes a geographical unity, covered with heaths and woods, and marked by rough terrain, hills and ridges.

The seigneurie of Neufchâteau consisted of a town with the same name and 31 small to very small, nucleated rural villages.Footnote 41 Each family performed subsistence-oriented and mixed farming on small peasant holdings mostly exploited as direct property. Already in the medieval period, the ownership titles of these lands had been ceded by the seigneurs of Neufchâteau in exchange for the securement of their seigneurial rights and privileges, including the payment of yearly taxes and the performance of several duties, mainly consisting of compulsory labour to the benefit of the seigneurs.Footnote 42 However, even the private agricultural possessions were incorporated in the Ardennes’ common land system. Arable farming was organised according to an open field system of crop rotation among the resident households of each village community. In between periods of cultivation, these arable lands necessarily lay fallow and were used as common pasture in order to slowly recover.Footnote 43 All resident households owned their livestock individually, but village herders guided the herds collectively over large stretches of common pastureland.Footnote 44 Apart from fallow arable land, this common pasture consisted of natural meadows and especially of extended heath lands that were owned by individual households or by village communities.Footnote 45 As such, the majority of the Ardennes’ lands were open to grazing rights for at least part of the year. Moreover, these grazing rights were not only performed within villages (vaine pâture), but also on the territory of neighbouring villages (parcours).Footnote 46 As the majority of the Ardennes’ surface was subjected to grazing rights while arable agriculture was of little importance, the breeding and trade of livestock was the primary economic activity of the Ardennes peasant communities. This was a highly commercial trade despite its remote location.Footnote 47 In addition to these agricultural activities, every registered household was allowed to gather and cut a share of the communities’ wood resources on an annual basis. The wood was used as building material, agricultural tools and especially as fuel (by means of ‘firewood rights’ or droits de chauffage).Footnote 48 This set of common rights was performed in woodland that was owned by the village communities (bois communaux) or in forests owned by the feudal seigneurs (bois seigneuriaux).Footnote 49

The assemblée vinagère or ‘village council’, composed by all heads of the resident households, was responsible for the management of the common rights and common land.Footnote 50 To be recognised as a resident household, the family head had to be married, widow or widower and own or rent a house.Footnote 51 This means that newcomers gained access to the common lands and rights relatively quickly and easily. Moreover, decisions were made by means of a majority vote, reinforcing the accessibility of the common land system. Although the village communities clearly enjoyed substantial liberties in the management of their common land, they remained under control of the seigneurial officers who organised the local jurisdiction and policing. This was particularly true for the common rights that the inhabitants enjoyed in the forests of their seigneurs.Footnote 52

During the second half of the eighteenth century, profound changes occurred in the Ardennes, with direct implications for the described common land system that had gradually been shaped from the medieval period onward. These changes resonated with societal, demographic and political shifts that characterised eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European rural societies, yet their effects were highly regionally specific. Roughly between 1750 and 1840, the European population doubled, the land ‘brought under the plough’ significantly enlarged, and rural communities were increasingly subjected to national jurisdiction and political control.Footnote 53 From the middle of the eighteenth century, rural societies in the Low Countries started to show signs of economic and demographic growth after a long period of wars and alimentary crises.Footnote 54 Similar to general trends in rural Europe, population growth in the Ardennes was triggered by a gradual productivity increase in agriculture and the introduction of new crops, beginning with the potato. Additionally, demographic behaviour was structured by impoverishment and related to the Ardennes’ common land system. To stimulate further population growth to sustain agricultural development, provincial ordinances in 1772 and 1773 obliged Luxemburg villages to offer small plots of common land to new households to allow them to build their own houses.Footnote 55 While the effect of these ordinances on migration remained modest, in 1788 the government admitted that population growth consisted of particularly poor families that entirely depended on the commons for their daily survival.Footnote 56

As a result, this growing number of families, dependent on the use of commons for their daily survival, generated more pressure on natural resources. Yet at the same time, common land came under attack in intellectual and political milieus throughout Europe. The intensifying exchange of knowledge, skills and technology, and the expansion of a more interventionist state started a so-called ‘Agricultural Enlightenment’.Footnote 57 Particularly during the reign of the Austrian empress Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II, Luxemburg was subjected to policies that aimed for the modernisation of its taxation system, uniformisation of its forest management and the so-called liberalisation of its economy, and most importantly its agriculture.Footnote 58 Informed by capitalist notions of property and production, these reform policies were the product of intense negotiations between the central state and the provincial authorities of Luxemburg.Footnote 59 Exactly because of Luxemburg's far-reaching participation in these negotiations, the general privatisation of community owned land as ordered in the other provinces of the Southern Low Countries made no headway in the Ardennes before the nineteenth century.Footnote 60 Even though no general privatisation was agreed upon, from the 1750s up to the 1780s a series of new legal regulations were promulgated in Luxemburg that attacked the common land system on different fronts, including the reduction of common firewood rights, the introduction of an experimental cadastre, the promotion of the enclosure of open fields, the cultivation of fodder crops and the creation of artificial pastures.Footnote 61

The implementation of each of these legal interventions heavily depended on the participation of local communities and their officers. While similar reforms seriously weakened or altogether abolished common land and use rights in most provinces of the Southern Low Countries after 1750, they largely remained in place in the Luxemburg Ardennes, only starting to erode much later.Footnote 62 In the second half of the eighteenth century, the Ardennes’ common land system was able to absorb demographic growth and successfully ward off more aggressive political attacks. Almost no communal land was sold before the second half of the nineteenth century and common use rights remained the backbone of the Ardennes’ economy for some more generations.Footnote 63 We claim that the preservation of a system of common land use and control during the turmoil of the eighteenth century was not the outcome of prolonged inertia. Rather, behind the remarkable resilience of the commons we discern a story of social differentiation and rising inequality in the use of the commons among and within the Ardennes’ communities. In the past, different social groups relied on the commons in similar ways, performing livestock farming in addition to the common access to the forests. In the eighteenth century, both the poorest and the richest groups started to make use of the commons in increasingly divergent ways, further articulating socio-economic inequalities.

Population growth of about 13 per cent between 1766 and 1791 was almost entirely absorbed by the poorest social group of nearly landless households that did not possess any animals to add to the collective herd. In this period, an additional 15 per cent of the households of the seigneurie of Neufchâteau became landless (from four to 19 per cent) and the number of households without any livestock increased from 11 to 17 per cent. Moreover, around two thirds of the landowners were smallholders with less than one hectare of land and maximum two cows for their direct household needs.Footnote 64 Although they officially enjoyed access rights to common grazing fields, these impoverished households did not, or only limitedly, take part in the local livestock economy. Consequently, they could no longer fully enjoy the benefits of the villages’ common pasture area (‘vaine pâture’), which constituted 67 per cent of the surface of the seigneurie of Neufchâteau in 1766.Footnote 65

This growing group of families increasingly relied on the access to forests, and instrumentalised their common firewood rights as a ‘precious but illegal’ commercial resource.Footnote 66 While common firewood rights were legally established to cover household needs, the growth of the metal industry in south-west Luxemburg and the subsequent rise in wood prices offered a commercial opportunity to households with no other access to the market. They secured a cash income source by selling large or all parts of the common firewood they received on a yearly basis. Additionally, these impoverished families performed various labour activities such as tree felling, wood chopping, charcoal burning and transportation related to the local forest economy. As such, they were incorporated in the expanding extractive operations of the metal industry that exported its products to foreign markets and transferred its capital gains to foreign owners.Footnote 67 Over time, the involvement of the rural poor in grazing activities reduced even further as this group of families increasingly developed alternative income strategies.Footnote 68 Heavily problematising the commercial exploitation of firewood by rural inhabitants, the council of Luxemburg repeatedly proclaimed that newcomers attracted by the province's demographic policies were almost all poor dwellers for whom access to the communities’ lands and rights became their most important or only source of income.Footnote 69

On the other side of the social spectrum a small elite of farmers constituting one tenth of the population in 1766, privately owned major parts of land and herds, mounting up to more than 100 animals.Footnote 70 They started to detach themselves from the traditional customs of the common land system in several ways. First, this small group of rich farmers started applying enclosure laws, as they were the only group able to cover the costs of this operation, in contrast to the majority of peasants who possessed small and scattered plots. This way, they increasingly guarded their individual meadows and arable land from common grazing practices. At the same time, they continued enjoying access to the uncultivated common pasture area owned by the village communities and to all individual landholdings that remained unenclosed. The gradual enclosure of the most valuable parts of the common pasture area increased the pressure on the remaining common, while its surface and quality decreased. Moreover, these elites increasingly managed private flocks instead of adding their animals to the common herds, hence avoiding community taxes.Footnote 71 In addition, some rich farmers sought to profit from the simultaneous processes of population growth and social polarisation by building and renting houses on their land in exchange for new families’ yearly part of common firewood.Footnote 72

In the process of resisting growing external political intervention and pragmatically responding to changing market conditions, village communities of the Ardennes witnessed rising internal inequalities. Both at the bottom and at the top of the Ardennes’ society inhabitants started pushing the boundaries of the common land system, seeking commercial opportunities in increasingly divergent ways. Political negotiation and economic adaptation allowed for the reproduction of the common land system, but this came with mounting internal pressure. For the time being, however, a strong and dominant middle group of peasant landholders was able to protect its interests in the commons and kept this twofold pressure in check.

The majority of smallholders and medium sized farmers clung to the traditional system of common pasturing, fiercely defending community wastes and resisting the enclosure of open private fields. They stipulated new local regulations that refuted enclosure laws in order to secure access not only to the communities’ uncultivated wastes, but also to the valuable yet scarce grasse pâture. This stock of arable land and meadows was vital to their livestock breeding and trading activities. In doing so, they forced rich farmers to contribute to the community taxes, instigating a series of juridical procedures on whether a certain plot of land could be enclosed or belonged to the common.Footnote 73 Simultaneously and at the other end of the social spectrum, the commercialisation of common wood resources and the growth of the poorest social group caused irritation among middle and rich farmers who aimed to preserve common forest land as open grassy spaces for pasturing and to safeguard timber to use as construction materials, fencing or as agricultural tools.Footnote 74 Yet subsequent litigations between the communities of Neufchâteau and their seigneurs indicate that, for the time being, the inhabitants could still transcend their differences and unite in their resistance against subsequent provincial forest regulations that reduced the supplies of common firewood.Footnote 75

3.2 The reproduction of common land rights in nineteenth-century Carangas

Our second case study is based on extensive archival research on Carangas, an area covering roughly the size of Belgium and situated entirely above 3600 metres on the Central Andean Plateau or altiplano (Figure 2).Footnote 76 Characterised by a semi-arid cold climate, and by wet and dry grassland and scrubland vegetation, the altiplano ranges from Southern Peru, over the western part of Bolivia to the northern parts of Argentina and Chile. In colonial times, from the sixteenth to nineteenth century, Carangas was incorporated as a province within the Spanish empire, and its communities were drawn into the rhythms of an emerging capitalist world-economy through the colonial Potosí silver trade, profiting from its strategic location between the ports of the Pacific and the mines of the Andean interior.Footnote 77 The decay of the mines since the late eighteenth century left the region in limbo, lacking the infrastructure to play a significant role in the late nineteenth century mining boom. In 1825, the province was integrated in the independent state of Bolivia as part of the Oruro department and remained a single provincial unit until 1951. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Carangas communities continue to own most land collectively, protected by communal land titles that have been incorporated and adjusted under Bolivia's successive land reforms in the twentieth century. Today, over 90 per cent of the Carangas population identifies as Aymara, Bolivia's second largest ethnic group, next to a nearly disappeared minority of Urus.Footnote 78 Carangas is an all rural region where most lands are communally owned and cannot be passed to a third party, except for the land in the ‘urban’ centre of provincial towns and mining sites. The land still is the basis of a pastoralist economy, combined with minimal subsistence farming and (frequently cross-border) commercial and barter exchange. Different from peasant households in eighteenth-century Ardennes, these families have no direct ownership of the land. Rather, the land still is in the hands of the community or ayllu. Indigenous authorities, which rotate on a yearly basis, are in charge of managing and distributing the land with different individual and collective use rights among the comunarios (community members). Lands most suitable for cultivation are distributed to families for small-scale subsistence farming (potatoes and barley, together with small quantities of quinoa, beans, cereals, alfalfa, and some vegetables), but the vast majority of land has been used collectively for open field pasturing through the present day.Footnote 79

Figure 2. Map of the Central Andean Plateau showing the province of Carangas within the Department of Oruro around 1900.

Source: Map designed by Hans Blomme (UGent) and based on Instituto Geográfico Militar, Atlas Digital de Bolivia (La Paz, 2000); ‘Mapa 1. Bolivia: Territorios Indígena Originario Campesinos Titulados’ in Juan Pablo Chumacero, Gonzalo Colque Fernández, Efraín Tinta G., Miguel Urioste Fernández de Córdova, Taller de Iniciativas en Estudios Rurales y Reforma Agraria eds., Informe 2010: territorios indígena originario campesinos en Bolivia entre la Loma Santa y la Pachamama (La Paz, 2011), 27.

According to nineteenth-century Bolivian jurisdiction, Carangas was organised in eight cantons, each roughly coinciding with indigenous administrative units called markas, each comprising a number of ayllus. Different from the Ardennes, common land rights were not attached just to residence, but to a household's fiscal status. Families were represented by an officially registered contribuyente or indigenous taxpayer. All male household members between the ages of eighteen and fifty had to pay a tributo (head tax) every six months. From colonial times into the twentieth century, taxpayers in Carangas had been categorised as originarios, agregados (or forasteros) and Urus. Originarios were full community members and enjoyed strong usufruct rights. Agregados were immigrants who integrated in a community different from their place of birth, had weaker rights to community land, and consequently paid a lower tax quota. Urus was a fiscal category that coincided with an ethnic minority group whose rights to land were being denied on the basis of their identification as so-called ‘people of the water’ (living on and around lakes, which served as a refuge from inter-ethnic discrimination) and who consequently paid very little.Footnote 80 The tributo was a colonially inherited device that drew the state and indigenous communities into a mutually enforcing relationship, coined by Tristan Platt as an implicit reciprocal ‘pact’.Footnote 81 In return for the purchase of land titles and fiscal loyalty, the Spanish Crown guaranteed the protection of indigenous community land and use rights. This asymmetrical relationship constituted an important source of revenue and loyalty for the state, and provided the ayllus with vital fiscal bargaining power.

From the late eighteenth century on, and particularly during the debates at the Cortes de Cádiz (1810–1814), new ideas on land and property started to circulate in Spanish America.Footnote 82 While deeply inspired by developments in Europe, pressures on common land took a more dramatic turn here. Initially, independence in Bolivia came with privatising land decrees, introduced by Bolívar in 1825, targeting Church and indigenous community lands. Yet, soon afterwards, they were abolished due to massive protest. In 1842, the Bolivian state decided to subject community lands to an emphyteusis regime (enfiteusis), in which the state as exclusive landowner leased usufruct rights on cultivation lands in return for taxes.Footnote 83 Despite these attempts at undermining communal land control, Bolivian communities were able to maintain and in some regions even strengthen their control over indigenous land and labour at least into the 1870s. Compared to rural communities in the Low Countries, historical data to reconstruct this process are much scarcer and mainly rely on indigenous taxpayer lists. These fiscal sources allow us to observe a more or less controlled equilibrium in land control between community and hacienda (large private landholding), until that balance broke in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.Footnote 84 Both landholding institutions – the community and the hacienda - were entangled in a complex dialectic relationship in which communal tenure did not straightforwardly regress, but recovered and even thrived in times when private estates declined.Footnote 85 Grieshaber's research into republican taxpayer lists demonstrates a stability in the number of indigenous taxpayers between 1838 and 1877, and even an increase in the case of highland communities.Footnote 86 This is remarkable given that the overall indigenous population in Bolivia declined by 17 per cent during the nineteenth century due to high mortality resulting from epidemic diseases, drought and famine.Footnote 87

The growing proportion of taxpaying comunarios to the overall community population resulted in a rising tax burden. While this was in the interest of the treasury, it was not organised by the government, but by communities themselves. Incorporating more community members in the taxpayer category was part of their adaptive response in order to safeguard their fiscal weight in the face of growing demographic pressures. The definition of contribuyente became more flexible while women and minors also adopted this fiscal status. Rather than a top-down imposition, the status of indigenous taxpayer was actively appropriated as an instrument that could be flexibly used to allow communities to uphold the number of tributaries. As this countered the impact of a demographic decline on the legitimacy of comunarios’ access to community land, this also reveals the status of the indigenous taxpayer as an essential tool in communities’ resilience strategies. This ‘playing’ with fiscal categories was not an exceptional measure but corresponds to a constant strategy that gained importance in times of crisis, as is also observed in Carangas.Footnote 88 As Grieshaber concludes, ‘[d]espite population decline, social discipline was maintained and the government legitimised the process. In essence, the increase in tributaries on the altiplano reflected the Indians’ ability to cope with epidemic disease and retain their communal organisation.’Footnote 89 However, this coping mechanism was increasingly challenged, particularly with the onset of the country's first land reform in 1874.

Grieshaber observes that this ability to protect community land rights and administrative structures was particularly manifest in altiplano pasture zones.Footnote 90 At first sight, this does not seem to apply to Carangas, where fiscal documentation suggests that the demographic effects of epidemics were milder than elsewhere until the end of the 1860s.Footnote 91 Carangas’ taxpayer share did increase, yet at a lower rate than other altiplano provinces. However, what this documentation does not reveal is that Carangas taxpayers had made an additional extraordinary payment in 1866 as part of a negotiation with the central state to protect their common land from new legislation. In that year, president Melgarejo re-launched early-republican liberal plans to privatise indigenous community lands, declaring the state absolute landowner and ending the contribuyentes’ leasehold status. Most communities were unable to pay for full property rights within the established term of 60 days and lost their land.Footnote 92 In Carangas, however, ‘it was said that the communities of the region were so powerful that they could consolidate their lands with regard to the exigencies of the tyrant.’Footnote 93 Carangas was one of the few provinces in the country that managed to lobby for a compensativo (compensation) payment in return for their exemption from the new legislation. Faced with a vital threat and in a context of epidemic-related demographic pressures, all contribuyentes, retired taxpayers (reservados) and widows with access to community lands paid a contribution slightly lower than the annual head tax burden.Footnote 94

Already in 1868, the Melgarejo decree was abolished, and a new land legislation was promulgated in 1874, known as the ‘Alienation Act’ (Ley de Exvinculación). It reformulated the same aspiration of a national capitalist transition around liberal notions of property in less drastic terms, but had an equally radical impact. The state unilaterally broke the ‘pact’ with the communities, abolished the head tax and ordered the privatisation of common land. The economic basis for this move was the expanding mining sector, which generated new revenues and liberated the treasury from its dependence on indigenous fiscal loyalty.Footnote 95 While the reform produced regionally diverse outcomes that far from reflected its aspirations, it did seriously undercut communities’ resilience. Between 1880 and 1930, Andean communities witnessed an out-migration in search of work, growing intra- and inter-community inequality, and a violent cycle of (il)legal land dispossessions and rural protest.Footnote 96 The trend of communities growing faster than haciendas was reversed. Particularly in regions with appropriate ecological conditions for agricultural surplus production, numerous communities were absorbed by an expanding semi-feudal hacienda system. However, communities in regions marked by pastoralism, community organisation, communal ethics, or relatively marginal extra-regional market integration such as Carangas, were able to safeguard their community lands.Footnote 97

Carangas’ story is usually told as a region that was ‘overlooked’ because its pasturelands were little attractive to entrepreneurs. However, these communities actively ‘extorted’ concessions that kept the region outside the new land legislation. Central to this strategy were the communities’ fiscal bargaining power and local alliances. Across the Andean departments, increased vulnerability incited a strong and coordinated reaction of indigenous leaders that essentially relied on colonially inherited guarantees and was quite successful in defending key indigenous demands against weak state structures.Footnote 98 In 1883, communities that kept their colonial land titles were formally exempted from the liberal land reform. Nevertheless, pressures to survey and subdivide community lands continued unabated, which incited legal and at times violent protest in Carangas, with letters reminding the state of the exceptional compensativo payment in addition to the authority of its colonial titles.Footnote 99

The reproduction of common land rights in Carangas was rooted in a strategy of fiscal negotiation. Paradoxically, the success of this strategy relied partly on the alliance of non-indigenous elites with the common land system. Provincial non-indigenous elites who acted as representatives were crucial but ambiguous actors in this negotiation strategy. These white and mestizo residents – known as the vecinos - represented hardly four per cent of Carangas’ population, but were able to monopolise the province's connections to the state and the market since the late eighteenth century.Footnote 100 Registered as ‘urban without land’, community land was inaccessible to them. Confronted with a numerical majority of community members and the local legitimacy of indigenous authorities, these elite families sought to consolidate their power base by controlling rural land within the common land system. They started to formally register themselves as indigenous taxpayers. While common land was maintained with the support of these elites, it involved a kind of camouflaged hacienda formation that would slowly unravel through the revolutionary land reform of 1952.Footnote 101

3.3 Survival through differentiation. Safeguarding common land rights

In both areas, common land systems were maintained while they disintegrated in surrounding regions. The reproduction of the commons was constitutive to these regions’ reputation as backwaters. However, as we have stressed, this reproduction was not just a matter of persistence or survival. A frontier perspective offers a historicising response by reading these processes as the outcome of a long history of peasant and indigenous adaptation, resistance and self-reinvention within a changing world. At least for a prolonged time, local communities were successful in destabilising attempts to free up new sources of uncommodified land and nature. Through a varied repertoire of reinterpretation and adaptation of access and use rights, rural inhabitants sought to safeguard and strengthen their economic or political bargaining power. It allowed different social groups to respond pragmatically to increasing social tensions. Within their diversity, the strategies of reproducing land rights sustained - at least for a prolonged period of time - mechanisms of coherence and resilience within the village communities. In the Ardennes, common land rights could be preserved in the wake of rising political attacks in the second half of the eighteenth century primarily because they continued to sustain the commercial interests of diverse social groups. In Carangas, the colonial and fiscal underpinning of common land rights offered communities a paradoxical yet effective lever for negotiation. In both case regions, we notice that communal land systems could not halt increasing social differences. However, they were able to absorb the trends of differentiation to a certain extent. Within both communities, different social groups started to develop their own tactics in which the commons acquired a distinct purpose. Over time, these internal contradictions increased, materialising in greater inequality and more conflict over the use of, access to and control over land. In the long term, this negatively affected social cohesion within and between communities, weakening and even disintegrating the systems of the commons.

In the Ardennes, the common land system remained in place until the late nineteenth century. However, as we have stressed, village communities were increasingly marked by internal economic inequalities. In response to political and demographic pressures, different social groups started to use the commons in a distinct way. Although common land rights continued to support group resilience, social differentiation engendered a slow but enduring process of erosion of local cohesion and solidarities. For example, evidence of the seigneurie of Neufchâteau suggests that low attendances to village boards and hence participation in political decision-making were an increasing problem that affected the legitimacy of local regulations.Footnote 102 Moreover, starting at the end of the 1770s, villages in the seigneurie of Neufchâteau and in other regions in Luxemburg advocated the abolition of the ‘droits de parcours’ with one or more of its neighbouring communities. Consequently, herds of neighbouring communities could no longer cross their immediate borders, increasing tensions between villages with large or small stocks of pastureland and causing a series of border and passage conflicts. We indicated that a growing group of poor peasants that owned few or no animals only marginally benefited from common pasture rights. As the opportunities created by commercialising their common forest rights waned and eventually diminished from the early nineteenth century onward, they lost interest in preserving the commons and started to push for their repartition and privatisation. For some generations, local elites that thrived on the livestock economy were able to prevent sales of common land. However, in the aftermath of the new land legislation of 1847, the Belgian government managed to implement an effective conversion of commons into private land, contributing to the eventual disappearance of common land rights in the Ardennes in the second half of the century. The Ardennes case study demonstrates that the common land system continued to function in the midst of rising external and internal pressures as long as it supported the economic position of the majority of its inhabitants.

In late nineteenth-century Carangas, fiscal arrangements enabled communities to enforce a level of autonomy through successive rounds of negotiation, compelling the Bolivian state to a deliberate policy of oblivion and non-intervention in internal communal land affairs.Footnote 103 Collective land rights have been maintained and renewed until today, but this came with profound implications for Carangas’ position in the wider economy and the internal cohesion of its communities. First, the financial burden on community members to maintain their communal fiscal strength marginalised the nineteenth-century commercial position of indigenous traders and transporters.Footnote 104 Secondly, communities experienced a social and ethnic reconfiguration. At the weakest end of the common land rights spectrum, systemic discrimination led to the dissolution of all but one tiny Uru community, resulting in a domination of Aymara communities. At the other extreme, non-indigenous elites seized the common land system as a basis for power consolidation. They formally adopted the indigenous fiscal status in order to gain access to community lands, and used their non-indigenous privileges to increase their power base. By skillfully combining different identities, they managed to camouflage how they monopolised the best lands and crucial political and economic positions. In the longer term, however, this group gradually dissolved and mixed with the Aymara families, a process accelerated by schooling, universal suffrage and other social changes that broke through with the National Revolution of 1952. The land reform of 1953 restored communal land tenure, yet under a dual (collective versus individual) land rights framework. Carangas and its common land system became increasingly vulnerable to ecological and demographic developments throughout the second half of the twentieth century. The 1953 land reform exacerbated rather than resolved the effects of a rural exodus, jurisdictional fragmentation, minifundismo (extreme small-scale plots), conflict over use and property rights and extreme climate conditions. In recent decades, new land reforms have recognised Carangas’ common land in a more plural way, as ‘Native Community Lands’ and as ‘Native Indigenous Peasant Territories’, although this was more about reaffirming land rights security than about structural reforms.Footnote 105 The Carangas case study demonstrates that the successful defence of common land rights relied at least partially on inter-ethnic reconfigurations and inequalities, and was unable to halt the protracted marginalisation of Aymara communities overall.

The Ardennes and Carangas present fundamental albeit contrasting aspects of a world-historical process of increasing pressure on common land systems. Starting in the eighteenth century, both regions increasingly integrated as peripheral spaces of production, exploitation and recreation in a modern state apparatus and a sweeping commercial economy. This process cannot be explained adequately by the victorious rise of private and secure property rights. The focus on the flexibility and agency of peasant frontiers allows us to observe how local common land rights did not persist as a residue of incomplete supra-local integration. Through their active adjustment, exploitation and reinvention, these rights played a crucial role in organising and reinventing resilient peasant livelihoods at a communal level in times of mounting vulnerability. In both cases, distinct peasant groups deployed the common land system as a resilience strategy in times of crisis and stress, a strategy that energised the reconfiguration of internal social power relations.

In a context of accelerating market expansion, state formation, demographic growth and social differentiation, the common land right systems in the Ardennes and Carangas proved to be remarkably flexible. Different social groups found distinct ways to use the commons as a source of income and bargaining power, revealing a responsive and intelligent understanding of state and market developments. The Ardennes communities relied strategically on their common lands to adapt their economic position to changing contexts, thereby increasing the differences among social groups. The Carangas communities skilfully exploited colonial guarantees that had been vital to the Spanish silver trade. They were able to safeguard a level of autonomy under a new phase of state formation, yet this involved inter-ethnic alliances and the redrawing of internal community relations.

4. Discussion: land rights and peasant frontiers

In this paper, we introduced the notion of peasant frontiers to understand how zones in the margins of state and market power that became part of territorial reorganisations and enclosure movements were able to remain spaces of renegotiation and resistance. This enabled us to question standard narratives of land commodification and rural transformations in the two research areas. Communal resource management that characterised both regions persisted and transformed through a longue durée negotiated history of peasant frontier formation. Increasing state and market pressures to commensurate local land rights with new notions of property in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries did not cause a linear disintegration of peasant communities’ land systems. Responding to internal and external dynamics, communities deployed common land rights as an economic or political negotiation tool in new and flexible ways. We assert that common land systems did not simply ‘outlive’ encroaching codification and commodification, but were increasingly deployed as a vital strategy of survival and adaptation to mounting demographic, economic and ecological pressures.

The reproduction of communal land practices in the historical trajectories of Andean and European peasant communities testifies to the paradoxical nature of capitalist expansion and peasant sustainability. Narratives about common lands circulate through imaginaries of either passive buffers or heroic islands of resistance that kept historical capitalism at bay. These imaginaries simplify the complex patterns through which common lands have been managed. While communities in the Ardennes and Carangas successfully defended common land rights, they witnessed growing levels of inequality both between and within communities. These inequalities could be absorbed in part by the common land system, yet it generated new internal transformations that picked up steam over the longer term. In the Ardennes, the divergence between a growing group of poor, almost landless peasants and a small local elite eventually contributed to the erosion of the common land system. In Carangas, the impact of internal divergence was neutralised as both a discriminated minority and an elite minority dissolved in the Aymara community. The observation of these internal divergences, and how they reshaped not only the management of common resources but also communities as a whole, relates to our introductory comments on vulnerability and resilience. These concepts must be understood at the communal and intra-communal level, taking into account unequal power relations and contested access to natural resources. Both case regions witnessed a decline in local resilience over the long term, linked to communities’ shifting relation to markets and to land reforms that have been centred on a univocal definition of property. Common land rights were a vital part of communities’ and families’ strategies to negotiate, resist and reinvent these changing relations, shattering the course of land rights commodification into multiple messy trajectories.

In this paper, we conceptualised peasant frontier as a research strategy that allows us to understand the rise and the limits of historical capitalism as an intertwined world-economic and world-ecological process, bringing in peasant agency and rural transformations as a central focus. We have argued that a frontier perspective enables us to grasp the imbalances of incorporation processes, emphasising the role of the margins and zones of friction. It invites us to study processes of incorporation and transformation of the countryside in a historical, interconnected and dialectical way and helps us to see that historical capitalism is a process rooted in a profound restructuring of rural societies and their relation to nature. Surplus production from nature has been a precondition for large-scale societal change, and societal change was necessary to group agricultural producers into peasantries. When this world-historical relationship started to disintegrate from the nineteenth century, peasantries shifted from being a driver to a burden with regard to societal progress, at least according to the new modernisation orthodoxy. The invention of private property was a major game-changer in the relationship between peasants and society. Peasant frontiers were thoroughly redefined by new forms of enclosure of land and labour. Direct incorporation radically altered ecological relations, resulting in a greater diversification of systems of access to nature, land and labour, systems of production and reproduction, and survival and coping mechanisms. Uneven incorporation and uneven commodification caused more social and spatial differentiation through divergent processes of de-peasantisation and re-peasantisation, and a concurrent diversification of peasant livelihoods. It is in this context that the concept of resilience should be rethought as the characteristic of social groups and communities, integrating the virtues of flexibility, cooperation, reciprocity, risk spreading and dealing with uncertainty. This approach enables us to rethink peasantries as frontiers and underscores their moral claims such as rights to access land, rights to be peasants, rights to keep their cultural identity, rights to receive a just price and to work for a just income. Bringing the peasant frontier to the centre of social change will deepen our historical and contemporary understanding of vulnerability and resilience. It encompasses a genuine moral discourse, as returning to the land is claimed not as a favour but as a right.