Introduction

Reviews capturing several decades of qualitative research highlight consistently that lonely older adults living with dementia experience suffering and poor quality of life (Bradshaw, Playford, & Riazi, Reference Bradshaw, Playford and Riazi2012; O’Rourke, Duggleby, Fraser, & Jerke, Reference O’Rourke, Duggleby, Fraser and Jerke2015). At least 10 per cent of Canadians in the general population report feeling always or often lonely (Statistics Canada, 2021). We have long known that a significant percentage of older people experience loneliness, and that older adults living with dementia are at particular risk: 25 per cent of community-dwelling older adults (Perlman, Reference Perlman2004), 42 per cent of those living in long-term care homes (Victor, Reference Victor2012), and 62 per cent of older adults living with dementia experience loneliness (Alzheimer’s Society, 2013). These painful feelings include emotional loneliness, which is feeling alone or that you are not cared about, and social loneliness, which is feeling that you do not belong (Ashida & Heaney, Reference Ashida and Heaney2008; Weiss, Reference Weiss1973). To address loneliness experienced by older adults living with dementia, gerontologists must determine how to promote feelings of social connectedness.

The opposite of loneliness, social connectedness, is subjective and indicated by feelings of reciprocal caring and belonging (O’Rourke & Sidani, Reference O’Rourke and Sidani2017). While there is little research establishing the prevalence of loneliness in care homes, many assert that loneliness remains a significant public health issue today (Gerst-Emerson & Jayawardhana, Reference Gerst-Emerson and Jayawardhana2015). Yet, we lack effective interventions to address this problem in care home populations (Brimelow & Wollin, Reference Brimelow and Wollin2017). Systematic reviews of the effects of interventions aimed to address loneliness among older adults demonstrate systematic exclusion of people living with dementia from empirical work evaluating the effects of loneliness interventions (Cohen-Mansfield & Perach, Reference Cohen-Mansfield and Perach2015; O’Rourke, Collins, & Sidani, Reference O’Rourke, Collins and Sidani2018; Quan, Lohman, Resciniti, & Friedman, Reference Quan, Lohman, Resciniti and Friedman2019), even when conducted in long-term care homes (Quan et al., Reference Quan, Lohman, Resciniti and Friedman2019), where the majority of residents live with cognitive impairment (Canadian Insitute for Health Information, 2020). The purpose of this study was to assess family members’, friends’, and health care providers’ perceived acceptability of an intervention (group leisure activity) for use to address loneliness among people living with dementia.

Group Leisure Activity Interventions

The term intervention refers to an action, strategy, or program that is specifically designed and delivered by someone (e.g., a researcher or a service provider) to address clearly defined problems (e.g., loneliness) or outcomes (e.g., quality of life) (Sidani, Reference Sidani2015). Group leisure activities have many possible goals, but those used in research studies as an intervention to affect loneliness have aimed to do so through the promotion of social participation and social contact via two main components: engagement in an activity and engagement with others in a group setting (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Collins and Sidani2018). When group leisure activity interventions are delivered in research studies, they can be considered a type of formal leisure opportunity, similar to participation in clubs or organizations (vs. informal leisure, such as visiting or socializing with friends) (Janke, Davey, & Kleiber, Reference Janke, Davey and Kleiber2006).

Group leisure activity interventions, which were designed to address loneliness, have primarily been evaluated in research with cognitively intact older adults (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Parpura-Gill, Kotler, Vass, MacLennan and Rosenberg2007; Winstead, Yost, Cotten, Berkowsky, & Anderson, Reference Winstead, Yost, Cotten, Berkowsky and Anderson2014). While many group leisure activities exist in practice (e.g., group exercise programs, playing Bingo), there is a very limited number of small studies that have focused specifically on group leisure activity interventions to address loneliness among people living with dementia. These include a study of cognitive stimulation therapy in groups (Capotosto et al., Reference Capotosto, Belacchi, Gardini, Faggian, Piras and Mantoan2017), a study of an art-viewing and art-making activity group (Windle et al., Reference Windle, Joling, Howson-Griffiths, Woods, Jones and Van De Ven2018, Reference Windle, Newman, Burholt, Woods, O’Brien and Baber2016), and a study of an intergenerational play group (Skropeta, Colvin, & Sladen, Reference Skropeta, Colvin and Sladen2014). In the cognitive stimulation therapy program, the authors proposed that social interaction in a group setting would alleviate loneliness among people living with mild to moderate dementia (Capotosto et al., Reference Capotosto, Belacchi, Gardini, Faggian, Piras and Mantoan2017). Emotional loneliness (i.e., feelings of intimacy) improved in the intervention group, yet social loneliness (i.e., feelings of belonging) worsened (Capotosto et al., Reference Capotosto, Belacchi, Gardini, Faggian, Piras and Mantoan2017). The authors did not assess whether positive, meaningful social interactions occurred in the group, which would have helped explain these mixed findings. In the study of art viewing and making, the findings did not support a statistically significant reduction in loneliness among community-dwelling people with mild, moderate, and severe dementia (in a sub-sample that completed outcome measures at two time points, n = 28) (Windle et al., Reference Windle, Joling, Howson-Griffiths, Woods, Jones and Van De Ven2018). However, qualitative data from the full sample (n = 63) supported that the group members’ interactions led to feelings of companionship (Windle et al., Reference Windle, Joling, Howson-Griffiths, Woods, Jones and Van De Ven2018). In the study of an intergenerational playgroup, which included people living with all stages of dementia, qualitative data supported that friendships were developed, suggesting that the intervention holds promise to promote feelings of social connectedness (Skropeta et al., Reference Skropeta, Colvin and Sladen2014). Overall, these results were mixed, but they do show that group leisure activity interventions hold promise to address loneliness experienced by people living with dementia. Further research is needed to explore the use of group leisure activity interventions specifically to address loneliness among older adults living with dementia, to determine the optimal frequency and duration of sessions, and select appropriate activities and facilitation approaches.

Any intervention aimed to address feelings of loneliness must consider the needs of subpopulations of older adults, such as people living with dementia. People living with dementia may require important adaptations to support their full participation and engagement to benefit from group leisure activity (Dattilo et al., Reference Dattilo, Siperstein, McDowell, Schleien, Whitaker and Block2019). The features of group leisure activity interventions align with growing knowledge about the possible (general) benefits and mechanisms of leisure, which have been observed among older adults living with dementia (Fortune & Dupuis, Reference Fortune and Dupuis2018; Genoe & Dupuis, Reference Genoe and Dupuis2014; Kleiber, Hutchinson, & Williams, Reference Kleiber, Hutchinson and Williams2002; Kleiber, Reel, & Hutchinson, Reference Kleiber, Reel and Hutchinson2008; Pedlar, Dupuis, & Gilbert, Reference Pedlar, Dupuis and Gilbert1996). To date, there is very little known about key stakeholders’, including family members’, friends’, and health care providers’, perspectives of the acceptability of group leisure activity interventions to (specifically) address loneliness among older adults living with dementia.

Intervention Acceptability

Understanding acceptability is a critical step to designing and evaluating a complex intervention (Skivington et al., Reference Skivington, Matthews, Simpson, Craig, Baird and Blazeby2021). Acceptability can be defined as a multidimensional construct that refers to key stakeholders’ perspectives of whether an intervention is appropriate, and perceived as useful, helpful, and easy to apply in everyday life (Sekhon, Cartwright, & Francis, Reference Sekhon, Cartwright and Francis2017). Acceptability refers to recipients and providers’ perceptions of an intervention either before, during, or after they participate in it, and whether they judge it to meet their needs or the needs of the target population (Sidani, Reference Sidani2015). Failure to assess intervention acceptability can result in resources being invested into an intervention that will not or cannot actually be used in everyday practice and will thus have a low likelihood of being used effectively to address the target outcome (Sidani & Fox, Reference Sidani and Fox2020).

It is important to understand intervention acceptability from the perspectives of those who will deliver it in practice (e.g., health care professionals) and those who may participate in it (e.g., people living with dementia and their care partners, family members, or friends) (Sekhon et al., Reference Sekhon, Cartwright and Francis2017). Participation in interventions and in large evaluation studies, which are needed to build the knowledge base, requires buy-in from health care providers and family and friends of people living with dementia. These individuals influence the participation of people living with dementia in interventions and research studies because their support is often needed to recruit participants, to obtain informed consent, and to assist with some aspects of intervention delivery (e.g., providing space, time, or transportation for sessions) (Sidani, Reference Sidani2015). In this study, we explored acceptability of group leisure activity interventions used to address loneliness experienced by people living with dementia, from the perspectives of health care providers, and significant others of people living with dementia in long-term care or community-based settings.

Methods

Design

Our purpose was descriptive and exploratory, and we used a cross-sectional mixed-methods complementarity design. In a complementarity design (as compared to another design such as expansion or initiation, for example), the qualitative and quantitative results are considered together to enhance interpretability of the results by capitalizing on the different strengths of each method (Greene, Caracelli, & Graham, Reference Greene, Caracelli and Graham1989). Qualitative and quantitative data were given equal weight in the interpretation of the results (Creswell & Plano Clark, Reference Creswell and Clark2018), where the qualitative results helped elaborate, illustrate, and clarify the quantitative ratings (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Caracelli and Graham1989). We completed data collection from June 2016 to April 2017. In each interview, we collected (quantitative) questionnaire data to describe how participants rated intervention acceptability, and (qualitative) semi-structured interview data to explore participants’ perceptions of the group activity interventions in more depth. In the findings section, we integrated the qualitative and quantitative results, describing the quantitative results immediately before each theme that helps explain it.

Intervention Theory for Group Leisure Activities Used to Address Loneliness

An intervention theory reflects an integrated description of how an intervention (e.g., group leisure activity) addresses a particular problem (e.g., loneliness) within a particular context (e.g., older people living with dementia) to promote specific outcomes (e.g., feelings of social connectedness and quality of life) (Sidani & Braden, Reference Sidani and Braden2021). Our intervention theory was derived from a scoping review of the features of loneliness interventions, which were designed for use with older adults (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Collins and Sidani2018), because of the limited literature on group leisure activity interventions aimed to address loneliness specifically among people living with dementia. Our analysis of existing empirical work defined how group leisure activity interventions may work (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Collins and Sidani2018; O’Rourke & Sidani, Reference O’Rourke and Sidani2017). Group leisure activities aim to address loneliness by targeting two of its modifiable influencing factors: social isolation and limited social participation (Ashida & Heaney, Reference Ashida and Heaney2008; Bethell et al., Reference Bethell, Aelick, Babineau, Bretzlaff, Edwards and Gibson2021; O’Rourke & Sidani, Reference O’Rourke and Sidani2017). Social isolation is more objective (as compared to loneliness) and refers to the amount or type of social interaction that a person may experience (Ashida & Heaney, Reference Ashida and Heaney2008). Social participation refers to meaningful activities that are chosen by a person and may (or may not) bring one into contact with others (Zelenka, Reference Zelenka2011).

Our scoping review demonstrated how group leisure activity interventions are defined by two main components or “active ingredients”: interactions between group members (addressing social isolation) and participation in a leisure activity such as the arts, music, exercise, or gardening (addressing social participation) (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Collins and Sidani2018). An intervention theory also specifies the mode of delivery and dose of an intervention. Empirical studies of group leisure activities used to address loneliness among older adults were delivered to groups of five to nine people, tended to be offered face to face once or twice per week, and were facilitated by a health care provider, researcher, or artist; these group leisure activities varied widely in their length per session (e.g., 90 minutes to 6 hours per session) and duration (e.g., 3 to 72 weeks) (Andersson, Reference Andersson1985; Baker & Ballantyne, Reference Baker and Ballantyne2013; Brown, Allen, Dwozan, Mercer, & Warren, Reference Brown, Allen, Dwozan, Mercer and Warren2004; Cohen, Reference Cohen2006; Cohen-Mansfield et al., Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Parpura-Gill, Kotler, Vass, MacLennan and Rosenberg2007; Routasalo, Tilvis, Kautiainen, & Pitkala, Reference Routasalo, Tilvis, Kautiainen and Pitkala2009; Winstead et al., Reference Winstead, Yost, Cotten, Berkowsky and Anderson2014).

Sample

Purposive sampling was used to recruit significant others and health care providers of a person living with dementia (who may have lived in any care home or community-based setting). Significant others were eligible to participate if they were: (a) a family member or a friend of a person living with dementia, (b) adults defined as > 21 years of age, and (c) able to read and write in English. Health care providers were eligible to participate if they were: (a) working in any paid position to provide care/services to older adults with dementia, (b) an adult (defined as > 21 years of age), and (c) able to read and write in English. This sample was selected because of their experiences caring for or interacting with the target population. Our sampling strategy also included an element of convenience sampling, as the study was advertised near the researchers’ institution (e.g., in flyers posted in the downtown area). The researchers did not have any previous relationships with participants or the institutions they were recruited from.

Participant Recruitment Strategies

We used three participant recruitment strategies: (a) placing advertisements in local newspapers and newsletters, (b) posting flyers in public spaces (e.g., community centres) and on bulletin boards at the participating university, and (c) word-of-mouth, where information about the study was spread by leaders of community-based organizations (e.g., the Alzheimer’s Society) and by study participants. Health care providers were also recruited by posting flyers in the public spaces of one large long-term care home in Toronto, ON. Advertisements and flyers stated that participation was voluntary, listed the eligibility criteria, and directed participants to call the research study office for more information.

Sample Size

Our final sample size was 25 participants, which addressed our exploratory aims in this complementarity design. With the needs of both the quantitative and qualitative analyses in mind, we aimed to recruit 25 to 30 participants. We aimed to generate some initial estimates of the proportion endorsing different items included in the quantitative questionnaire within several points of accuracy, and this can be accomplished with a relatively small sample (e.g., n = 20) (Hertzog, Reference Hertzog2008). We also did not want to recruit a sample so large that it would prohibit our ability to follow up on these ratings with the same participants in more depth in qualitative interviews (and to analyse those interviews). Previous qualitative interview-based studies have described that samples of about 20 tend to achieve some level of information redundancy, while samples over 50 can complicate the analysis (Vasileiou, Barnett, Thorpe, & Young, Reference Vasileiou, Barnett, Thorpe and Young2018). The final sample size was determined by logistics (we continued to collect data throughout the funded period), but we also observed significant information redundancy during our qualitative analysis and generated few new codes after the first 15 interviews, suggesting that our qualitative analysis could have been completed with fewer interviews (Saunders et al., Reference Saunders, Sim, Kingstone, Baker, Waterfield and Bartlam2018). We concur with recent critiques and recognize that complete saturation is likely not possible; the ability to generate new insights is not simply a function of the data but also of the individual completing the analysis (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2021).

Informed Consent and Ethical Approval

Participants talked to the research assistant (RA), to confirm their interest and eligibility, and to schedule an interview at the research office. Written informed consent was obtained at the research office before the interview. The RA reviewed the study details (i.e., purpose, activities, risks, benefits) and the consent form, and addressed questions. All people who arrived for an in-person interview were given $60 to offset transportation costs. The Toronto Metropolitan University (REB 2016-100) and University of Alberta Research Ethics Board (PRO 00126840) approved this study, and we received operational approval from the care home that we approached to assist us with recruitment.

Data Collection

Interviews were conducted by two researchers, HMO and NJ, in-person at the research office, and were completed in individual or small-group sessions of two or three individuals, according to the preferences of the participant. Most (n = 17) chose to complete individual interviews. We did not notice obvious differences between the information provided in individual as compared to group sessions. Light refreshments (water and cookies) were provided.

Demographics

Participants were asked their age (in years), gender (man, woman, or other gender), and cultural or ethnic background (open-ended). Health care providers were also asked to identify their professional title and their work setting with older adults living with dementia.

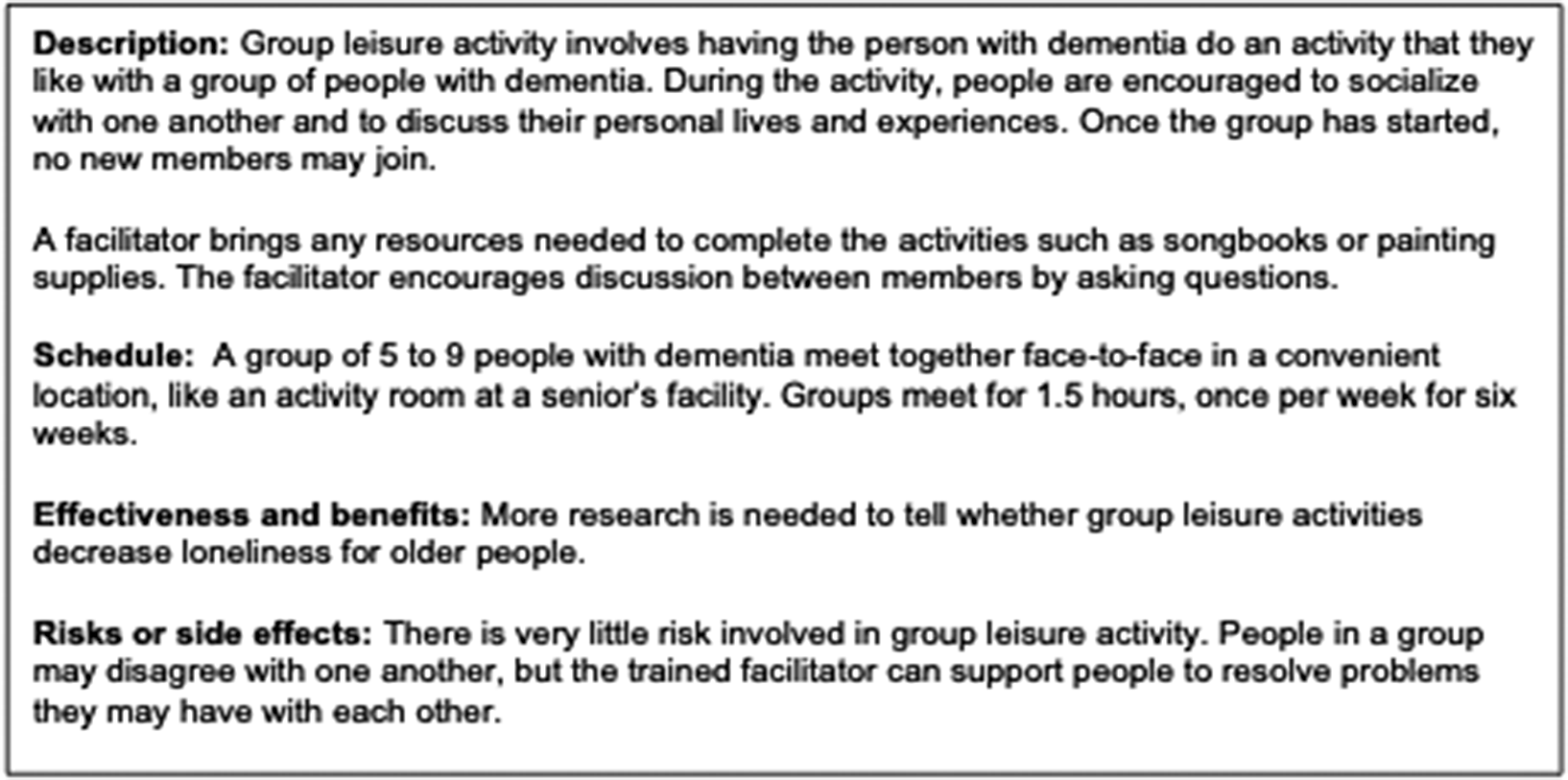

Questionnaire

We used the Treatment Perception and Preference (TPP) scale (Sidani, Epstein, Fox, & Miranda, Reference Sidani, Epstein, Fox and Miranda2016). The TPP is internally consistent (α > .85) and correlates as expected with people’s stated treatment preferences, supporting construct validity (Sidani et al., Reference Sidani, Epstein, Fox and Miranda2016). Six items followed the description of the group leisure activities intervention, to rate its acceptability as a strategy to address loneliness experienced by people living with dementia. The items covered its perceived benefits (i.e., effects in improving loneliness), appropriateness in addressing loneliness, ease of use, and risks when used with people living with dementia, on a 5-point scale. For example, in terms of benefits/effects, participants rated group activities as “Not effective at all” (0), “Somewhat effective” (1), “Effective” (2), “Very effective” (3), or “Very much effective” (4). After recoding the risk item, the total scale score can be computed as the mean of the respective items’ scores, ranging from 0 to 4. In this study, we did not compute the total score as our findings focused on our analysis of each individual item in relation to the qualitative data. In this study, the TPP questionnaire started with a lay description of group leisure activities to inform participants of the intervention, as per the scale developers’ recommendation (Figure 1). The intervention description was derived from a review of literature among older adults; it delineated the group leisure activity intervention’s goals, activities, mode, and dose of delivery as well as risks and benefit (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Collins and Sidani2018).

Figure 1. Description of group leisure activities provided to participants.

Interview guide

We completed the interviews immediately following the ratings, and these were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The semi-structured interview guide explored participants’ perspectives on the type of group leisure activities, how to support communication, use of focused topics versus informal socializing, activity duration, group composition, family and friends’ willingness to participate, and health care provider willingness to offer group leisure activities (see Supplementary File 1).

Analysis

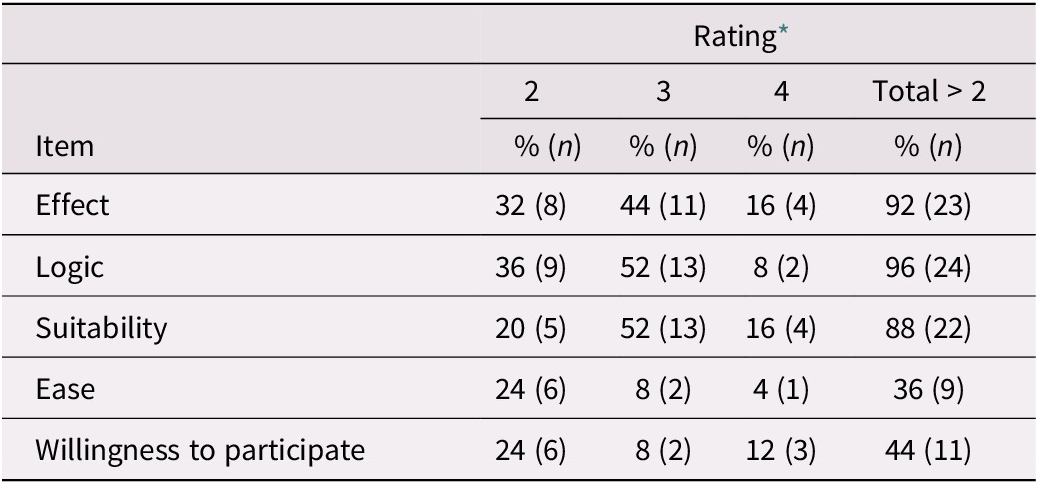

Quantitative and qualitative data were analysed separately, and the results were compared and integrated to generate the final themes. The percentage of participants who rated each item as > 2 (e.g., effective, logical, suitable), indicating acceptability, was identified using descriptive statistics (SPSS version 22.0). This step raised questions that could be further explored with the qualitative data, for example, ease of delivery seems to be rated lower than other areas. Do the qualitative findings offer insight into why this might be the case? Descriptive rather than inferential statistics were used in this phase because the purpose of this study was to explore stakeholders’ perceptions of acceptability and to generate understanding of their perspectives by integrating complementary (qualitative and quantitative) descriptive data sources.

A qualitative descriptive approach was used to analyse participants’ responses to the interview questions. This involves a lower level of interpretation (i.e., stays closer to participants’ intended meanings) as compared to other qualitative methodologies, although there is always a level of interpretation present in generating codes, categories, and themes to represent the results (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000). The qualitative data were synthesized using conventional content analysis, which aligns with a qualitative descriptive approach as it aims to generate codes that closely reflected participant’s understandings and views (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). A qualitative content analysis involved systematic coding of textual data and categorization of codes to identify thematic patterns (Hsieh & Shannon, Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005). Two qualitative analysts (BW and SQ) used the comments function in Word to highlight meaningful phrases (i.e., meaning units) and attach a code (one or a few words that summarized the meaning unit). BW grouped together similar codes into broader categories and named the categories. Categories were organized within more abstract, overarching themes that described core patterns interpreted from the data. At each step, we aimed to represent participants’ intended meanings. The steps are described below.

First, the two independent reviewers, BW and SQ, reviewed three transcripts to become familiar with the data and then coded meaning units, generating a code list. A brief definition was added to each code in the list. They reviewed one another’s code lists and coded transcripts and shared these with a third member of the analytic team, HMO, for feedback. After the three members of the analytic team had agreed upon a preliminary code list, the two independent reviewers, BW and SQ, coded the remaining transcripts (adding new codes to the shared code list as needed) and met regularly with each other and the third reviewer, HMO. Both analysts coded all transcripts to support an in-depth discussion of the emerging findings during our meetings and to support a broader interrogation of our final results. During the meetings, we reviewed and discussed tables that linked all themes, categories, codes, and their supporting data (i.e., the audit trail). The audit trail that we discussed at these meetings was based on the analysis completed by one of the two analysts, SQ, because we did not expect their coding to match exactly nor seek to achieve agreement on every coded data element.

The themes were finalized during integration; the first author, HMO, integrated the quantitative and qualitative findings. This process involved an additional qualitative analysis at the level of reorganizing some categories and finalizing the descriptions of each theme in order to use the qualitative findings to help explain or contextualize the quantitative findings. Building on the questions generated from the descriptive quantitative results (e.g., why is logic rated more positively than ease of delivery or risks?), HMO reviewed the qualitative themes, categories, and codes. HMO re-organized several categories and revised the description of the themes. She updated the audit trail throughout this process, to verify that any revisions to the theme definitions were well-supported by the categories, codes, and data. The findings and audit trail were shared with the analytic team to ensure that the results reflected each team members’ understandings of the data. We found that the qualitative results complemented and explained the quantitative ratings; these are described together below to support a rich understanding of participants’ acceptability of the use of group leisure activities to address loneliness among people living with dementia.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Twenty-five individuals, ages 23 to 65 (mean 41.76 years + 12.03), participated in the study. Eleven (44%) were men. The sample included 16 significant others (i.e., family or friends [FF]) and 9 health care providers (HCP). The HCPs were health care aides (n = 3), registered nurses (n = 2), and licensed practice nurses (n = 4) employed in long-term care (n = 7) and home care settings (n = 2). The sample reflected the ethnocultural diversity of the Greater Toronto Area from which participants were recruited. Respondents identified themselves as “Ugandan” (n = 1), “Arab” (n = 1), “Asian” (n = 1), “Portuguese” (n = 1), “white European” (n = 1), Canadian of Greek background” (n = 1), “of Japanese descent” (n = 1), “Eastern European” (n = 2), and as “Filipino” (n = 3), and “Canadian” (n = 3). One participant described a mixed background, “black and Spanish,” and two participants (8%) chose not to describe their ethnic background.

Benefits of Group Leisure Activities

The quantitative results showed that high percentages of participants viewed group leisure activities as potentially effective (92%) and logical (96%) as a strategy to address loneliness among people living with dementia (Table 1), and this was supported by the perceived benefits of group leisure activities described in the qualitative data. The most important benefit of group activities was that interaction within a group setting could promote bonding and feelings of belonging, supporting that those participants found this intervention to be logically aligned with the intended outcomes of group leisure activities: I think it’s important for people with dementia to realize that they’re not alone and it’s like when you’re in a group setting like that with other people with the same affliction, there’s a common bond… (FF2). Participants noted benefits to physical and mental health of people living with dementia: …when they come out after the group activities, they are all happy, everything is different and they make friends (HCP5). This improved mental health could make staffs’ jobs easier: The residents who are more involved in activities will take their medication so easily (HCP5). Family and friends may also benefit from group leisure activities, for example, by being able to socialize, enjoy an activity, or see their loved one smiling or engaging in an activity: I think it’s a very warm feeling seeing your loved ones smiling with that activity (HCP4). Experiencing respite may be an additional benefit for family and friends who are caregivers: I think the value of this type of group is that you have time – like it’s another period of relief basically (FF4).

Table 1. Frequency of acceptability ratings of ≥ 2 for group leisure activities (n = 25)

* 2 = effective, logical, suitable, easy, willing to participate; 3 = very effective, very logical, very suitable, very easy, very willing to participate; 4 = very much effective, very much logical, very much suitable, very much easy, very much willing to participate.

Beliefs About Social Interaction and Dementia

The quantitative results indicated that most participants rated group leisure activities as suitable (88%); however, the qualitative data identified two contrasting beliefs that need to be addressed to ensure suitability of group leisure activity interventions for people living with dementia. First, many participants, and family and friends in particular, were unsure about the suitability of having an external facilitator support the group interaction, believing that people will interact anyway, given the existing care home environment: But like having someone come to a care facility which already has, you know, like people that know each other and interact with each other and that are already in group leisure activities, like that kind of seems redundant… (FF8). In contrast, other participants emphasized verbal communication abilities, which lead many family and friends to believe that people living with dementia would not be able to connect with one another once their ability to communicate verbally was substantially affected: I mean, again, if they’re not capable of speaking and expressing their mind, what good would this do? (FF11).

Flexible Approaches to Program Delivery

Although participants rated group leisure activities as suitable overall, the qualitative findings identified advantages and disadvantages related to the suggested time frame for group leisure activities (90 minutes, once per week, for 6 weeks). The variation in responses supported that group leisure activities should be designed for flexible delivery and that sustainability of programs be carefully considered. Participants were split in relation to session length. Some felt that the session would be too long, leading to feelings of boredom and problems with attention and focus. Others felt that 90 minutes was about the right amount of time to fit abilities and prevent fatigue, with very few suggesting that the session should be longer: An hour a half a week. That’s probably, like, about right, I would say, you know, because it confuses them, their mind is not set for that (FF612).

Several participants discussed that trial and error in group size, composition, activity type, and the level and nature of family involvement may be required: Think you would have to do a lot of trial around this to see how it goes, you know, right down to, like, how many people in a room, right? (FF6). Participants frequently suggested that the duration of the group leisure activity intervention should extend beyond six weeks so that participants could experience long-term benefits. Participants described how this may be the only activity that the person would be involved in, and termination at six weeks could contribute to loneliness: But the idea of ongoing I think is vital. Because otherwise it seems like such a short-term benefit (FF13).

Carefully Facilitating Sessions and Selecting an Activity

Quantitative results demonstrated that just over a third (36%) of participants rated group leisure activities as being easy to deliver. Most participants thought that group leisure activities required a trained, skilled facilitator. They felt that it was important that the facilitator have knowledge of dementia, the ability to react to the tone of the group (i.e., “read the group”), and support the needs of people living with dementia. The characteristics of the facilitator were someone who was knowledgeable about dementia, comfortable with a flexible approach to guiding the group leisure activities, and who was authentic in their presentation of themselves and in their interactions with others: Again, I think it’ll come down to like the training of the facilitator and are they comfortable just kind of reacting to the mood of the room (FF4).

Participants did not support a rigid approach to discussion topics. Instead, facilitated sessions would have a loose structure based on a topic of interest or derived from the activity that people were engaged in to help focus and prompt the interactions, and to guide people with different kinds of abilities to participate: From my opinion it’s much better informal. So like why don’t you give them an informal topic that they can express themselves? (HCP4). Similarly, when selecting the group leisure activity, one should consider diverse needs and interests: Like there’s just so many variables and human factors, so like I can’t think of like one activity that I think everyone is going to be keen on (FF8). Participants thought activities should fit physical and cognitive abilities to comprehend and retain information and to remain attentive, focused, and interested: Anything that’s not challenging, yeah, for them. It depends on the individual, right, which is okay with them (FF7).

Familiar activities, like cooking, painting, dancing, music, and playing games, were proposed as something that the person may remember or like to do, promoting continued participation: My mom was a very good cook, so I would think things like meal preparation, that sort of thing…she would really enjoy that (FF3). Participants also spoke positively about the use of creative activities, such as painting, music, dance and art, and activities that supported physical and mental function: I’ll say a class, like maybe I should say painting or a dance class, or just something to keep them active, like swimming (HCP3). For residents living in care homes, activities to connect with the outside world were identified as particularly important: …like you need the person to get outside of that realm too and feel they’re still valued in the world and they still have some, some existence outside of their sickness (FF8).

Building a Group, Everyone’s Different

Despite the favourable perception of group leisure activities, the quantitative results revealed that only 44 per cent of participants were willing to participate in group leisure activities along with people living with dementia. This can be explained by participants’ uncertainty related to what group size and composition would be in the best interest of people living with different stages of dementia. Participants perceived that one’s cognitive abilities, and specifically retention, comprehension, and focus, could affect group size and composition: …it would depend on the stages of their dementia, the behavioral tendencies of the person, too, how many should be in the group (FF3). Smaller groups were recommended for people living with more advanced cognitive impairment: Four to five. Sometimes we have only three (HCP9).

People living with mild dementia were seen as requiring less facilitation, able to complete more complex activities, and potentially not wanting to participate in a group with people with more severe dementia. Several participants identified that it may not be appropriate to invite all people to participate in group leisure activities: …depending on the person’s personality or are they going to be nasty, are they going to cry or are they going to lash out somehow, because there’s this one lady who tells everybody they’re stupid (FF10). Some felt that group membership should be limited to people living with dementia to promote connection between people who may share similar challenges, promoting feelings of comfort and bonding: That way they can relate with each other what they’re going through… (FF5). Other participants wondered whether family members would be a distraction during sessions, or were unclear as to why people without dementia would want to participate: I just don’t know why people without dementia would be partaking in that group (FF2).

Others thought having family or friends present for at least some sessions (e.g., the first few sessions) may help the person with dementia feel more comfortable: …some of the patients feel comfortable if they have somebody they are used to close to them, other than going by themselves… (HCP7). Others suggested a mixed composition group as a way of adding diversity and to expand the type of activity the group could participate in: I think like a mixed group might have more benefit …and maybe with more people just with more diverse backgrounds …I think it might feel more natural for that person or they might feel more included and not as stigmatized, not as isolated (FF8).

Time was cited as a key barrier to participation of family and friends in these groups given other commitments like work, travel distance, and other personal and family commitments: I would say yeah, commitments, personal commitments, because umm, you know, if everyone is working and if it’s during the daytime versus evening (FF3). The relationship between the family member and the person living with dementia, as well as the family member’s beliefs about dementia, was also a key consideration; family members who already visited often were seen as more likely to attend: I think you get two kinds of caregivers that I’ve seen. You see some caregivers who are largely absent because of the stigma associated with or for distance or for other commitments. And then you have some people who are more involved and engaged as far as their family member is concerned (FF13). Many participants thought that health care providers may want to be involved, but key barriers were identified, including workload, and that such activities are not a current part of their role: We are willing, if we have time (HCP6).

The Risks Posed by Dementia-Related Stigma

The quantitative results demonstrated that group leisure activity was viewed as low risk, with 64 per cent rating the risks as not bad at all; however, 32 per cent did consider the risks to be somewhat bad. One risk, discussed in the previous section, was related to the way that some people communicate, which may be influenced by the disease process; it can result in mistreatment by other group members (e.g., calling names or physical altercations). A key strategy to address this issue is to limit the group size to less than five and ensure that the facilitator is skilled to support positive, productive interactions. The primary risk of group leisure activities described by participants was the potentially stigmatizing effect of placing people into a group simply because they had dementia. The concern was that this approach might perpetuate a view that people are defined by their dementia disease: I mean that’s a challenge with my father in terms of like he doesn’t want to let the condition define his life and we tend to ignore it, but if you start grouping everything into dementia like categories…then they kind of actually can revert back to this person feeling isolated and alone… (FF8).

Many participants raised the issue of stigma, and those negative views of dementia could influence participation in group leisure activities: I’d say most of the time those people who are able and for whom dementia is not a stigma, would be willing to participate (FF13). Some participants described their own negative perceptions of people living with dementia and suggested that this lessened their interest in such activities: It’s like baby talk like one baby to another. It’s not really something that a normal person like myself would be able to talk to somebody like (FF11). The idea of being around other people living with dementia was therefore not always valued and was seen by some as potentially harmful by highlighting the person’s disease status, perpetuating stigma: …is it really healthy or productive or progressive to get them all together in a group, like what benefit is that going to have necessarily. It can have actually an adverse consequence of stigmatizing them even more, or like, you know, I can only be put in dementia like groups (FF8).

Discussion

The benefits of group leisure activities discussed by participations in this study included activity enjoyment and socialization, similar to group leisure activity researchers’ hypotheses that social participation and social contact are core intervention mechanisms that address loneliness (Andersson, Reference Andersson1985; Baker & Ballantyne, Reference Baker and Ballantyne2013; Brown et al., Reference Brown, Allen, Dwozan, Mercer and Warren2004; Cohen, Reference Cohen2006; Cohen-Mansfield et al., Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Parpura-Gill, Kotler, Vass, MacLennan and Rosenberg2007; Routasalo et al., Reference Routasalo, Tilvis, Kautiainen and Pitkala2009; Winstead et al., Reference Winstead, Yost, Cotten, Berkowsky and Anderson2014). This finding supports acceptability, in terms of the perceived logic of group leisure activities, to address loneliness. Descriptive research has also identified that leisure activity engagement can offer older adults and people living with dementia opportunities to be with others (Dupuis et al., Reference Dupuis, Whyte, Carson, Genoe, Meshino and Sadler2012), to promote compassionate relationships (Fortune & Dupuis, Reference Fortune and Dupuis2018; Kleiber et al., Reference Kleiber, Hutchinson and Williams2002), and to participate in society (Lorek, Reference Lorek2017), helping maintain relationships (Fortune, Whyte, & Genoe, Reference Fortune, Whyte and Genoe2021) and increase engagement with the world in a variety of communities (Kleiber et al., Reference Kleiber, Hutchinson and Williams2002; Pedlar et al., Reference Pedlar, Dupuis and Gilbert1996). However, there are several other potential benefits of leisure that participants in our study did not discuss in relation to group leisure activity interventions, including increasing opportunities for personal development and social support (O’Rourke et al., Reference O’Rourke, Collins and Sidani2018), supporting adjustment to illness (Kleiber et al., Reference Kleiber, Reel and Hutchinson2008), promoting identity and knowing oneself and others (Dupuis et al., Reference Dupuis, Whyte, Carson, Genoe, Meshino and Sadler2012; Genoe & Dupuis, Reference Genoe and Dupuis2014; Kleiber et al., Reference Kleiber, Reel and Hutchinson2008), generating meaning and promoting growth (Dupuis et al., Reference Dupuis, Whyte, Carson, Genoe, Meshino and Sadler2012; Fortune & Dupuis, Reference Fortune and Dupuis2018; Kleiber et al., Reference Kleiber, Hutchinson and Williams2002), and offering fun and enjoyment in the moment (Kleiber et al., Reference Kleiber, Hutchinson and Williams2002). These factors also influence experiences of social connectedness and quality of life from the perspectives of people living with dementia (O’Rourke, Duggleby, et al., Reference O’Rourke, Duggleby, Fraser and Jerke2015). Family members and friends who may be making decisions about enrolment in a group leisure activity intervention on behalf of the person living with dementia could be encouraged to think about the full range of potential benefits, which may promote their willingness to consent to the person’s participation. As discussed below, when family members or friends have a narrow view of the possibilities for living well with dementia, this can limit the opportunities available to people living with dementia, to engage in leisure and social activities.

It is particularly important to design group activity interventions for use with people living with dementia who may have fewer leisure opportunities (Kleiber et al., Reference Kleiber, Hutchinson and Williams2002), such as people living with dementia in long-term care (Dupuis & Alzheimer, Reference Dupuis and Alzheimer2008). People living with dementia in long-term care homes are at particularly high risk for social isolation and loneliness because informal leisure opportunities are more limited (Freedman & Nicolle, Reference Freedman and Nicolle2020). Health changes can lead to more social isolation (Janke et al., Reference Janke, Davey and Kleiber2006), care home residents receive 50 per cent fewer visits than those living in the community, and care home residents living with dementia are at highest risk of isolation from family and friends (Port et al., Reference Port, Gruber-Baldini, Burton, Baumgarten, Hebel and Zimmerman2001). Recreation therapists have long implemented formal leisure opportunities in care homes, although there remain many questions about how to design these in ways that effectively address barriers experienced by people living with dementia, such as for active engagement, and which are feasible for implementation within care home environments (Cohen-Mansfield & Jensen, Reference Cohen-Mansfield and Jensen2022). Paradoxically, our findings signal that it may be most difficult to implement group leisure activities to promote continued meaningful relationships with family and friends in groups that need them the most – those at high risk of social isolation, low social participation, and resulting loneliness. While some family and friends in our study highlighted potential benefits to their own participation in a group leisure activity intervention, including enjoying the activity themselves and seeing the person with dementia connecting with others and enjoying themselves, many were reluctant to join a group leisure activity intervention with people living with dementia. While we know that many families and friends may distance themselves from the older adult living with dementia (Vikström et al. Reference Vikström, Josephsson, Neely and Nygard2008), our understanding of why this occurs is underexplored, undertheorized, and the reasons are likely complex. More research is needed to better understand how the experiences and perspectives of family and friends influence their willingness to participate in group leisure activity interventions aimed to support the continuation of meaningful relationships for people living with dementia (Dupuis & Smale, Reference Dupuis and Smale2000).

Stigmatizing perspectives are one factor that likely affected participants’ views of the potential effectiveness of group leisure activities and their ratings of willingness to participate in them. Stigmas identified in our findings were related to perceptions of the (in)abilities of people living with dementia to learn and engage and should be addressed when developing and delivering group leisure activity interventions. Some of the views expressed by participants can perpetuate isolation, for example, when an individual believes that people who experience neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia may need to be excluded from group leisure activities. We have long known that there are societal stigmas related to dementia and to aging that can contribute to disengagement and poor quality of life among older adults (Milne, Reference Milne2010). Our findings show how people’s beliefs about social interaction and dementia can affect families’ and friends’ willingness to participate in and valuation of group leisure activity interventions. In our sample, family and friend participants expressed concerns about using group leisure activities with older adults living with dementia because it was difficult for them to envision how these would work when the dementia disease process constrained the person’s verbal communication abilities. This emphasis on verbal communication was likely in part due to the description of group leisure activities that we gave them, which also emphasized verbal communication. However, this also reflects previous research, which has shown how people’s expectations of older adults can lead to restrictions on available leisure opportunities (Pedlar et al., Reference Pedlar, Dupuis and Gilbert1996). It is important to adapt interventions to support full participation and engagement (Dattilo et al., Reference Dattilo, Siperstein, McDowell, Schleien, Whitaker and Block2019; Genoe & Dupuis, Reference Genoe and Dupuis2014), considering the stage of dementia and selecting activities that will support feelings of connection to others without requiring verbal communication. One way to address this is through use of creative activities, emphasized by participants in our study. We concur with other researchers who highlight the need to understand how to optimize different kinds of creative group leisure activities to promote positive engagement in activities and social interactions among people living with dementia (Clare & Camic, Reference Clare and Camic2019).

To be effective, group leisure activities must be designed to do much more than simply deliver an activity to a group of people. Recreation staff have already been trying to shift practice toward smaller groups that support tailored, individualized activities and resident engagement, but this has been challenging within environments that still remain highly task-focused (Ducak, Denton, & Elliot, Reference Ducak, Denton and Elliot2018). Most participants in our study did not view group leisure activities as being easy to deliver. Our qualitative findings highlighted the complexity of group leisure activity intervention design, due to the need for tailoring and flexibility. Similar to other research on leisure interventions designed to address a range of outcomes like agitation, affect, engagement, and quality of life (Han, Radel, McDowd, & Sabata, Reference Han, Radel, McDowd and Sabata2016), our findings about the use of group leisure activity interventions to address loneliness highlight how important it is to tailor interventions to support diverse interests and needs. We know that tailoring is important to the quality of one-on-one interactions between a person living with dementia and a health care provider, but there are also additional considerations for how to tailor activities within congregate care settings, where the norm has been to deliver large group programming (Ducak et al., Reference Ducak, Denton and Elliot2018). Participants discussed how activities should be selected carefully to align with individuals’ preferences, and our themes demonstrated that expert facilitators are needed who can balance attending to people’s differences while also remaining responsive to the shared needs of people living with different stages of dementia disease. Related research has described the importance of identifying and supporting engagement in preferred activities among people living with dementia, which are sometimes simple, everyday activities like cooking or an informal visit (Menne, Johnson, Whitlatch, & Schwartz, Reference Menne, Johnson, Whitlatch and Schwartz2012). We need to be cautious of assuming that simply offering activities to small groups of people will solve issues related to poor engagement in large group activities (Ducak et al., Reference Ducak, Denton and Elliot2018), and the extent to which different kinds of group leisure activity interventions actually promote meaningful and positive engagement between participants, and alleviate loneliness, also requires careful assessment in future research to further develop the evidence base (Cohen-Mansfield & Perach, Reference Cohen-Mansfield and Perach2015). We also did not identify any one “right” amount of time for session length, and participants in our study highlighted the need for flexibility in this regard. While 90 minutes was seen as appropriate by many participants, pilot studies can offer a variety of session lengths (e.g., 30, 60, and 90 minutes) and allow participants to choose how long they would like to participate in an activity. Results from pilot and feasibility studies will help describe a range of possible session lengths and show how flexibility in session length can promote engagement and support the needs of diverse people.

Decisions related to group leisure activities and group composition must fit the needs, abilities, and interests of people living with dementia, while remaining focused on the person not the disease. Participants felt that people’s differences should be protected and honoured, and that being placed in a group simply because one has dementia could undermine individuality. Offering a variety of activities was seen as one way to honour individual differences and was thought to potentially increase family interest and involvement in group leisure activity sessions. To mitigate the risk of perpetuating stigmas related to dementia, it may also be important to identify other reasons for the person with dementia to join a group, focusing on the activity engagement or upon benefits to other people or communities and not only the person living with dementia. For example, in an intergenerational program, children and their caregivers also benefit from interactions with people living with dementia and older adults (Skropeta et al., Reference Skropeta, Colvin and Sladen2014). This also highlights how group leisure activities can be designed that are appropriate for use with people living with dementia, without limiting group membership to those living with dementia. Among people living with dementia, the activity selected should not rely upon memory or cognition as these can be highly exclusionary in this group (Mittner, Reference Mittner2021). Inclusive group leisure activities would support people living with dementia to actively participate, to develop social relationships, to have fun, and to make choices, and may involve helping others and acquiring skills and confidence (Dattilo et al., Reference Dattilo, Siperstein, McDowell, Schleien, Whitaker and Block2019).

Strengths and Limitations

Our sample was culturally diverse, and our analysis of two data sources was rigorous, had a clear audit trail, and benefited from a team approach where we could discuss assumptions and ensure the codes, categories, and themes reflected in the data. The main limitation to this study is that the views of older persons living with dementia were not investigated. Current critiques of the literature (Kane, Murphy, & Kelly, Reference Kane, Murphy and Kelly2020; O’Rourke, Fraser, & Duggleby, Reference O’Rourke, Fraser and Duggleby2015) show how both health care professionals and researchers have held stigmatizing beliefs related to dementia, such as the damaging perspectives that people living with dementia lose their personhood or lack insight into their own experiences. We believe that the views of older adults with dementia are essential to consider, to fully understand intervention acceptability. In our ongoing work to develop interventions that promote social connectedness among people living with dementia, acceptability from the perspective of older adults living with dementia will be assessed during feasibility studies, using both observational and self-report measures (e.g., during and immediately following their participation in these interventions). Another limitation is that there were no recreation therapists who chose to take part, although they fit our inclusion criteria. The perspectives of recreation therapists who are also involved in delivering programming in care homes would be important to explore in future studies.

Conclusion

Our findings support that group leisure activity interventions are seen as potentially beneficial, logical, and low risk by family, friends, and health care providers of a person living with dementia, while ease of delivery and willingness to participate in these interventions are less often endorsed. Our findings support the importance of developing, evaluating, and offering choice from a suite of individualized interventions to best support the needs for social connectedness of people living with dementia. It is a complex, but important, undertaking to develop acceptable group leisure activities that will promote social connectedness for diverse individuals living with dementia, and which will encourage engagement among their families and friends – people who often matter most to the quality of life of the person living with dementia (O’Rourke, Duggleby, et al., Reference O’Rourke, Duggleby, Fraser and Jerke2015).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980823000314.

Funding

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Post-Doctoral Fellowship program and the Faculty of Nursing, University of Alberta Professorship in Dementia Care Interventions (both held by the first author). Funders were not involved in any aspect of the research, in the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interest

None.