Suboptimal sleep is a major public health burden globally: ‘about 25% of adults are dissatisfied with their sleep, 10–15% report symptoms of insomnia associated with daytime consequences, and 6–10% meet criteria for an insomnia disorder’.Reference Morin and Benca1 For example, in older adults in South Africa, 9.1% reported nocturnal sleep problemsReference Peltzer2 and among older rural South Africans 31.3% of men and 27.2% of women reported nocturnal sleep problems.Reference Stranges, Tigbe, Gómez-Olivé, Thorogood and Kandala3 It would be important to identify modifiable behaviours, such as the intake of fruit and vegetables, that are beneficial to sleep quality to reduce the public health impact.Reference Jansen, She, Rukstalis and Alexander4

A systematic review found that a healthy diet (including fruit, vegetable and milk) was reported to be linked to higher sleep satisfaction.Reference Godos, Grosso, Castellano, Galvano, Caraci and Ferri5 Several cross-sectional studies, for example among mid-life Mexican women,Reference Jansen, Stern, Monge, O'Brien, Lajous and Peterson6 young American adultsReference Jansen, She, Rukstalis and Alexander7 and older adults in China,Reference Lee, Chang, Lee, Shelley and Liu8 showed that a higher intake of fruit and vegetables was beneficial to sleep quality. Among urban adults in China, higher fruit but not vegetable intake was inversely associated with poor sleep quality.Reference Wu, Zhao, Szeto, Wang, Meng and Li9 In Japanese workers, lower vegetable intake increased the odds of poor sleep qualityReference Katagiri, Asakura, Kobayashi, Suga and Sasaki10 and among Brazilian workers, inadequate fruit and vegetable intake was associated in both men and women with poor sleep quality.Reference Hoefelmann, Lopes Ada, Silva, Silva, Cabral and Nahas11 In another cross-sectional study among university students from 28 countries, higher fruit and vegetable intake decreased the odds of poor sleep quality.Reference Pengpid and Peltzer12

A longitudinal study among young adults in Pennsylvania, USA, found that women with chronic insomnia who increased their intake of fruit and vegetables by three servings/day were twice as likely to report symptoms no longer meeting the threshold for chronic insomnia at 3 months.Reference Jansen, She, Rukstalis and Alexander4 It is unclear whether fruit and vegetable intake is associated with incident and persistent poor sleep quality in Africa. Hence, this investigation aimed to evaluate the association between fruit and vegetable intake and incident and persistent poor sleep quality in a longitudinal study in rural South Africa.

Method

Participants and procedures

We analysed longitudinal data from two consecutive waves of ‘Health and Aging in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa’ (HAALSI). Full information on the sampling methodology has been previously detailed.Reference Gómez-Olivé, Montana, Wagner, Kabudula, Rohr and Kahn13 The first survey (November 2014 to November 2015) included 5059 individuals (≥40 years of age) and had a response rate of 85.9%;Reference Gómez-Olivé, Montana, Wagner, Kabudula, Rohr and Kahn13 the second survey (October 2018 to November 2019) included 4176 members of the Wave 1 HAALSI cohort (595 (12%) died during follow-up; 254 (5%) declined participation; 34 (<1%) were not found; response rate: 94%).Reference Kobayashi, Farrell, Langa, Mahlalela, Wagner and Berkman14 The study was conducted by trained field workers in the homes of participants using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI).Reference Gómez-Olivé, Montana, Wagner, Kabudula, Rohr and Kahn13

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human participants/patients were approved by the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (ref. M141159), the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Office of Human Research Administration (ref. C13–1608–02) and the Mpumalanga Provincial Research and Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

Outcome variable

In the first and second survey poor sleep quality was assessed using the Brief Version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (B-PSQI), which includes five domains: self-reported sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency and sleep disturbances during the past month.Reference Sancho-Domingo, Carballo, Coloma-Carmona and Buysse15 Summary scores range from 0 to 15 and a B-PSQI cut-off of ≥5 was used to define poor sleep quality; sensitivity and specificity rates are similar to the original PSQI version.Reference Sancho-Domingo, Carballo, Coloma-Carmona and Buysse15

Exposure variable

Fruit and vegetable intake was identified using the following items:

(a) ‘In a typical week, on how many days do you eat fruit? (… days)’

(b) ‘How many servings of fruit do you eat on a typical day? (on any one day) (… servings)’ [use of show cards, one standard serving equals 80 g, 1 medium-size piece of apple, banana, orange, etc.; half a cup of chopped, cooked, canned fruit, etc.; half a cup of fruit juice (juice from fruit, not artificially flavoured)]

(c) ‘In a typical week, on how many days do you eat vegetables? (… days)’

(d) ‘How many servings of vegetables do you eat on a typical day? (on any one day) (… servings)’ [use of show cards, one standard serving equals 80 g, 1 cup of raw green leafy vegetables (spinach, salad, etc.), half a cup of tomatoes, carrots, pumpkin, corn, Chinese cabbage, fresh beans, onion, etc., half a cup of vegetable juice].Reference Gómez-Olivé, Montana, Wagner, Kabudula, Rohr and Kahn13

Covariates

(a) Sociodemographic information, including education, age, marital and migration status, and asset-based household wealth status.Reference Gómez-Olivé, Montana, Wagner, Kabudula, Rohr and Kahn13

(b) Current tobacco use, defined as current non-smoking and/or current tobacco smoking.Reference Gómez-Olivé, Montana, Wagner, Kabudula, Rohr and Kahn13

(c) Alcohol dependence, assessed using the four-item CAGE questionnaireReference Ewing16 (Cronbach's alpha was 0.82).

(d) Body mass index (BMI), classified according to World Health Organization criteria.17

(e) Hypertension, defined based on Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure criteria.Reference Chobanian, Bakris, Black, Cushman, Green and Izzo18

(f) Dyslipidaemia, defined as total cholesterol >6.21 mmol/L, HDL-C <1.19 mmol/L, LDL-C >4.1 mmol/L, triglycerides >2.25 mmol/L, or ever diagnosed or medication use for high cholesterol.Reference Gómez-Olivé, Montana, Wagner, Kabudula, Rohr and Kahn13

(g) Diabetes, classified as fasting glucose (defined as >8 h) >7 mmol/L (126 mg/dL), or ever diagnosed or medication use for diabetes.Reference Gómez-Olivé, Montana, Wagner, Kabudula, Rohr and Kahn13

(h) Physical activity and its levels, classified using the General Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ).Reference Armstrong and Bull19,20

(i) Sedentary behaviour, identified using one question on the GPAQ – ‘time usually spend sitting or reclining on a typical day?’Reference Armstrong and Bull19 – and grouped into <4 h, 4 to <8 h and >8 h per day.Reference van der Ploeg, Chey, Korda, Banks and Bauman21

(j) Depressive symptoms, defined as scores ≥3 on the eight-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D 8)Reference Radloff22 (Cronbach's alpha 0.66).

(k) Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, defined as ≥4 symptoms identified using a short screening scale for DSM-IV PTSDReference Breslau, Peterson, Kessler and Schultz23 (Cronbach's alpha 0.83).

Data analysis

The proportion of participants with incident and persistent poor sleep quality was calculated and described. The first longitudinal logistic regression analysis excluded those with poor sleep quality at baseline, leaving a sample of 3904 individuals, to estimate incident poor sleep quality (using scores ≥5 as the cut-off), and the second logistic regression analysis estimated longitudinal persistent poor sleep quality (using scores ≥4 as the cut-off). Fruit and vegetable intake was the main predictor, controlled for sociodemographics, substance use, physical activity, sedentary behaviour, BMI and chronic health conditions. Levels of P < 0.05 were accepted as statistically significant. Logistic regression models included inverse probability weights that accounted for the probabilities of mortality and attrition during follow-up.Reference Kobayashi, Morris, Harling, Farrell, Kabeto and Wagner24 All analyses were performed using Stata SE 15.0 for Windows (College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Sample characteristics by incident and persistent poor sleep quality

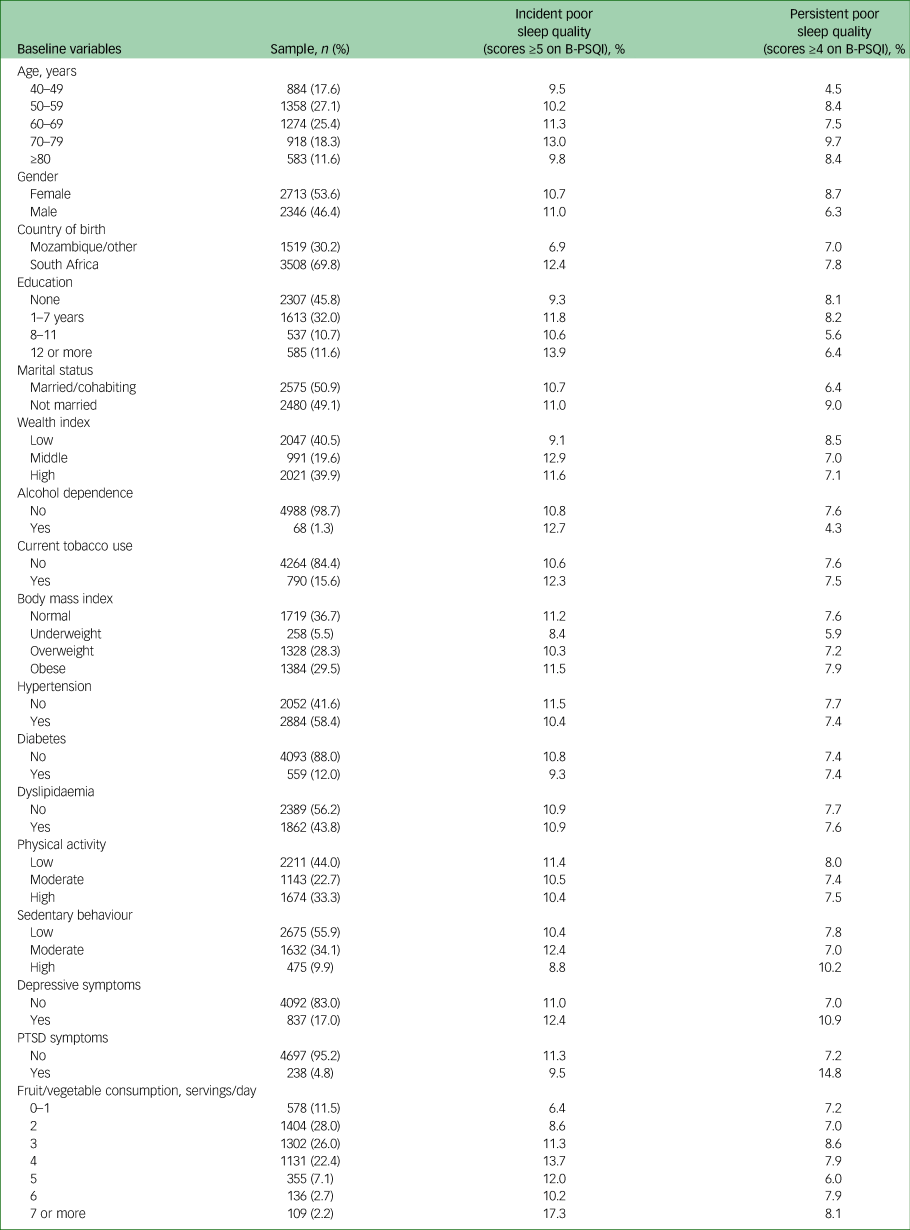

In total, 331 of 2775 participants without poor sleep quality in Wave 1 (11.1%) had incident poor sleep quality in Wave 2 and 270 of 3546 participants who had poor sleep quality in Wave 1 (7.6%) had poor sleep quality in both Wave 1 and 2 (persistent poor sleep quality). The prevalence of poor sleep quality at baseline was 17.2%. Table 1 shows characteristics of participants by incident and persistent poor sleep quality.

Table 1 Sample characteristics by incident and persistent depression, Agincourt, South Africa, 2014–2019

B-PSQI, Brief Version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

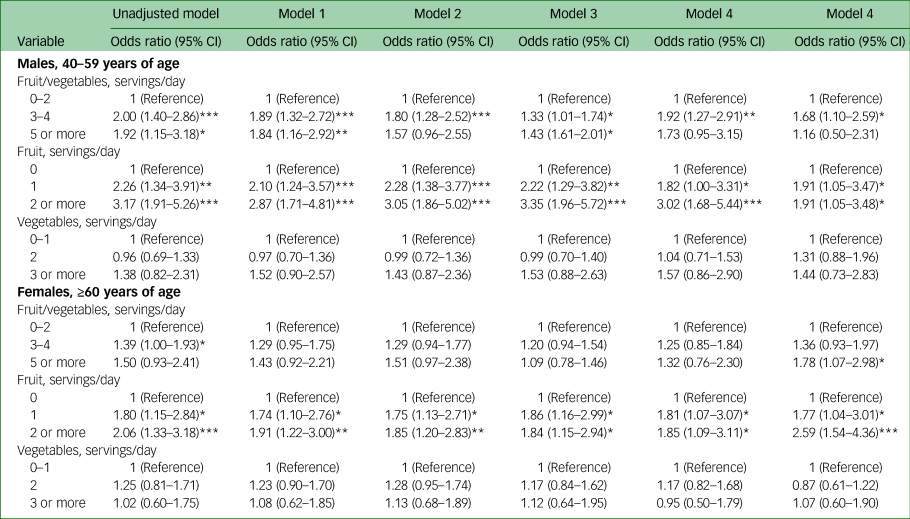

Correlations between fruit and vegetable intake and incident poor sleep quality

In the fully adjusted model for people without poor sleep quality at baseline, higher fruit and vegetable consumption (≥5 servings/day) was positively associated with incident poor sleep quality among men (AOR = 1.43, 95% CI 1.51–2.01) but not among women (AOR = 1.09, 95% CI 0.78–1.46). Two or more servings of fruits were positively associated with incident poor sleep quality among men (AOR = 3.35, 95% CI 1.96–5.72) and among women (AOR = 1.84, 95% CI 1.15–2.94). No models among men or women showed a significant association between vegetable intake and incident poor sleep quality (Table 2).

Table 2 Longitudinal association between fruit and vegetable consumption and incident poor sleep quality (scores ≥5 on B-PSQI), Agincourt, South Africa, 2014–2019a

B-PSQI, Brief Version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

a. Model 1: adjusted for age, education, migration, marital and wealth status. Model 2: adjusted for Model 1 variables, plus substance use, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and body mass index. Model 3: adjusted for Model 1 and 2 variables, plus dyslipidaemia, hypertension and diabetes. Model 4: adjusted for Model 1–3 variables plus depressive symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Associations between fruit and vegetable intake and persistent poor sleep quality

Table 3 shows, based on the longitudinal analysis, associations between fruit and vegetable intake and persistent poor sleep quality. No models for either gender showed a significant association between fruit and vegetable intake and persistent poor sleep quality. Fruit intake (one serving) was positively associated with persistent poor sleep quality among men (AOR = 1.76, 95% CI 1.00–3.08) but not among women (AOR = 1.42, 95% CI 0.93–2.18).

Table 3 Longitudinal association between fruit and vegetable consumption and persistent poor sleep quality (scores ≥4 on B-PSQI), Agincourt, South Africa, 2014–2019a

B-PSQI, Brief Version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

a. Model 1: adjusted for age, education, migration, marital and wealth status. Model 2: adjusted for Model 1 variables, plus substance use, physical activity, sedentary behaviour and body mass index. Model 3: adjusted for Model 1 and 2 variables, plus dyslipidaemia, hypertension and diabetes. Model 4: adjusted for Model 1–3 variables plus depressive symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms.

* P < 0.05.

Discussion

In this first longitudinal study on the subject among an ageing population in South Africa, we found that compared with low fruit and vegetable intake, high fruit and vegetable intake was positively associated with incident poor sleep quality 4 years later among men and but not women. Higher fruit intake increased the odds of incident poor sleep quality in both genders. No association was found between vegetable intake and incident and persistent poor sleep quality. Among men only, compared with no serving of fruit, having one fruit serving a day was positively associated with persistent poor sleep quality.

Contrary to these findings, previous cross-sectional and longitudinal studies found an inverse relationship between fruit and vegetable intake, fruit intake and poor sleep quality.Reference Jansen, She, Rukstalis and Alexander4–Reference Jansen, Stern, Monge, O'Brien, Lajous and Peterson6,Reference Lee, Chang, Lee, Shelley and Liu8,Reference Wu, Zhao, Szeto, Wang, Meng and Li9,Reference Hoefelmann, Lopes Ada, Silva, Silva, Cabral and Nahas11,Reference Pengpid and Peltzer12 Similar to the study among Chinese urban adults,Reference Wu, Zhao, Szeto, Wang, Meng and Li9 we found no association between vegetable intake and poor sleep quality, whereas in a study in Japan lower vegetable intake increased the odds of poor sleep quality.Reference Katagiri, Asakura, Kobayashi, Suga and Sasaki10 It is possible that poor sleep quality increases emotional distress, leading to more fruit consumption, potentially reducing negative mood,Reference Finch, Cummings, Lee and Tomiyama25 which points to a possible bidirectional relationship between fruit and vegetable consumption and poor sleep quality.Reference Noorwali, Hardie and Cade26

We found gender differences in the positive relationship between fruit and vegetable intake and incident poor sleep quality and fruit intake and persistent poor sleep quality among ageing men in South Africa, whereas among young American adults higher fruit and vegetable intake decreased incident insomnia among women.Reference Jansen, She, Rukstalis and Alexander4 In the present study higher fruit intake was strongly associated with higher wealth status (P < 0.001, analysis not shown), and higher wealth status may also be associated with high calorie-dense food, which is related to poor sleep quality.Reference Kobayashi, Morris, Harling, Farrell, Kabeto and Wagner24 Further investigations are needed to identify possible reasons for the found gender differences in fruit and vegetable intake in relation to poor sleep quality.

Study limitations

Some data, including sleep quality, were assessed by self-report and not verified by actigraphy or polysomnography, which may have led to an over- or underestimation of poor sleep quality. We were not able to show reasons for poor sleep quality and how this may be related to social or personality characteristics. Furthermore, participants who did not have poor sleep quality in Wave 1 may have had poor sleep quality before. Perceived stress, which might serve as a moderator between fruit intake and poor sleep quality, was not evaluated in this study, and other dietary behaviours that might have contributed to sleep quality, such as calorie-dense food intake, were not measured.

Data availability

The data used in this study are publicly available at the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies (HCPDS) programme website (www.haalsi.org).

Author contributions

Both authors conceived and designed the research, performed statistical analysis, drafted the manuscript and made critical revisions of the manuscript for key intellectual content. Both authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to the authorship and order of authorship.

Funding

HAALSI (Health and Aging in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number 1P01AG041710-01A1) and is conducted by the Harvard Center for Population and Development Studies in partnership with Witwatersrand University. The Agincourt HDSS was supported by the Wellcome Trust, UK (058893/Z/99/A, 069683/Z/02/Z, 085477/Z/08/Z and 085477/B/08/Z), the University of the Witwatersrand and South African Medical Research Council.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.