KINGSTON AND THE MEMORY OF SLAVERY

If you wander down to the waterfront of Kingston's magnificent harbour, you will see no reminder of the most important fact about Kingston's history – that it was the “Ellis Island” of African American life in British America, the place where nearly 900,000 Africans were landed to begin what was usually a miserable existence as mostly plantation slaves and occasionally urban slaves between Kingston's founding in 1692 and the abolition of the slave trade in 1808.Footnote 1 Only Rio de Janeiro – a slave port for a much longer period than Kingston – surpasses Kingston as the American location where most Africans became American slaves. Yet, there is no marker among the docks, banks, and commercial buildings that comprise the Kingston waterfront, where, in the eighteenth century – peaking in the decades after the end of the American Revolution – thousands of Africans arrived every year to be sold into slavery, sometimes immediately after disembarkation. Indeed, reminders of Kingston's slave past are virtually absent from the thriving city of over one million people. The only public monument to slavery in the city is Laura Facey Cooper's impressive but controversial statue in Emancipation Park in the heart of the city's business district, “Redemption Song”, which depicts two naked Afro-Jamaicans looking skyward to celebrate emancipation on 1 August 1834.Footnote 2 For the most part, however, the role that slavery, the slave trade, and slaves played in creating the most dynamic city in the English-speaking Caribbean (Figure 1) is largely ignored in contemporary Kingston.

Figure 1. “A Map of the Middle Part of America”, in William Dampier, A New Voyage around the World … (London, 1697).

Historians, too, have mostly ignored Kingston and its enslaved population. Apart from a series of articles by this author, an article from 1991 by Barry Higman on Jamaican port towns in which Kingston features heavily, a historical geography by Colin Clarke that covers the history of Kingston from 1692 to the late twentieth century, two unpublished theses by graduates of the University of the West Indies (Wilma Bailey and Lorna Simmonds), and an unpublished PhD by Douglas Mann, the history of Kingston has been neglected within British Atlantic historiography.Footnote 3 Despite being the fourth largest town in the British Atlantic before the American Revolution and the town with the largest enslaved population in British America before emancipation, the literature on Kingston is sparse. Indeed, its neighbours – Port Royal and Spanishtown – are better served by historians.Footnote 4 The result of such historiographical neglect is a lacuna in scholarship. We know too little about the role of slavery in shaping Kingston and even less about the lives of the enslaved population who thronged its streets, not least on the waterfront, where in 1832 a large percentage of slaves lived and worked and where, on King Street, near the harbour, every week 10,000 people from town and country attended a “Negro market”.Footnote 5

In this article, I examine one period of the history of slavery in Kingston, from when the slave trade in Jamaica was at its height, from the early 1770s through to the early nineteenth century, and then after the slave trade was abolished but when slavery in the town became especially important. One question I especially want to explore is how Kingston maintained its prosperity even after its major trade – the Atlantic slave trade – was stopped by legislative fiat in 1807. In 1793, a committee set up by the Jamaican House of Assembly to enquire into the effects of a possible abolition of the slave trade declared that the abolition of the slave trade “would gradually diminish the number of white inhabitants in the island, and thereby lessen its security” and “would cause bankruptcies, create discontents” and that in Kingston “such merchants as have already acquired fortunes by trade, seeing no probability of employing their money to advantage in the purchase of lands in Jamaica, would quit the country, and carry away their capitals; and the traders and shopkeepers, being their customers, would not be able to make their annual remittances, either to their correspondents or to the manufacturers in Great-Britain”.Footnote 6 Yet, these grim prognostications did not come to pass.

Among the parishes in Jamaica after 1807, Kingston alone did not suffer economic decline. Indeed, if real estate transactions are one guide, Kingston enjoyed an economic boom before and after the abolition of the slave trade. Ahmed Reid and David B. Ryden show that between 1800 and 1810, the price of land continued to soar in Kingston while property prices in the hinterland collapsed: Kingston land prices increased in this period by nearly a quarter, while prices in the interior fell by over forty per cent, returning to levels not seen since before the 1740s.Footnote 7 Its boom was testimony to the inventiveness of Kingston residents, who moved seemingly painlessly from providing the slave labour that was the lifeblood of the plantation system to being the fulcrum of British trade with Latin America during the Napoleonic wars.Footnote 8 Yet, this move at the top levels of mercantile activity did not reduce the town's commitment to slavery. Indeed, urban slavery, which had been in relative decline in the last years of the eighteenth century, picked up pace after 1807, meaning that by 1815 the percentage of Jamaica's enslaved population that lived in Kingston was higher than at any time since the early eighteenth century.Footnote 9

THE DEMOGRAPHY OF SLAVERY IN KINGSTON

How many enslaved people were there in Kingston and how important were they within the Jamaican slave population? As is often the case for population statistics for this period, the data is confusing and conflicting. There are three ways of establishing the size of the enslaved population: an annual poll tax on slaves for the purposes of revenue collection; occasional censuses (as in 1774 and 1788); and figures derived from the registration of slaves legislation implemented as part of British amelioration of slavery policies from 1817. In most parts of Jamaica, the differences between the numbers of enslaved people enumerated in poll tax records and censuses or slave registration records were not that great. In Jamaica, excluding Kingston, the poll tax numbers of enslaved people enumerated in 1817 were ninety-four per cent of enslaved people registered under the Slave Registration Act of the same year. In Kingston, however, the poll tax recorded only 45.4 per cent of enslaved people resident in the town. In 1788, the percentage was even lower. The number of enslaved people enumerated in the poll tax for that year was just thirty-seven per cent of the enslaved people noted as living in Kingston in a census taken that year.Footnote 10

Edward Long, writing in 1774, claimed that the tax lists were very accurate, arguing that “we have no data so simple, so intelligible, & so certain as the poll Tax returns”. But, as he admitted, a “small and limited number [of whites who were exempted] from the payment of the Taxes and Negroes were left out”, including such people as overseers and people who did not own land but who rented out their slaves to planters. In the countryside, such exempted persons and their slaves were relatively few in number: Having carefully compared the poll tax records with the actual numbers of slaves in Westmoreland Parish in south-west Jamaica, Long estimated that one seventh of the slave population was not accounted for in the tax records (a somewhat higher percentage than in 1817, where 92.8 per cent of Westmoreland slaves were included in poll tax data). From this investigation, he asserted that although the tax lists do “not shew the whole numbers of Negroes actually on the island […] the exemption is uniform and cannot affect the list much more at one period than another”. The problem was that slavery in Kingston did not accord with these assumptions. The large number of men and women who owned just one or two slaves and who were renters rather than owners of land meant that many slave owners and their slaves were exempted from the poll tax. In 1832, 1,843 of 2,557 slave owners in Kingston (72.1 per cent) owned between one and five enslaved people and just 254 slave owners owned more than ten enslaved people.Footnote 11 In addition, as will be discussed below, many enslaved people were kept in merchant yards ready for sale to retail purchasers. It is possible that such enslaved people were not counted as permanent residents of the town. Consequently, as Table 1 shows, the differences in population size between enslaved people listed in poll tax lists and those noted in censuses or under the Slave Registration Act were considerable.

Table 1. Estimates of Jamaica's Slave Population, 1745–1834.

NB. Between 1797 and 1815, it is assumed that the poll tax accounted for ninety-four per cent of Jamaican slaves and forty-six per cent of slaves in Kingston. Between 1740 and 1774, it is assumed that the poll tax accounted for sixty per cent of slaves in Kingston. Figures have been adjusted accordingly.

Sources: Higman, Slave Population and Economy, pp. 255–256; Burnard, “Crucible of Modernity”, p. 127; Ryden, West Indian Slavery and British Abolition, p. 301.

It needs to be noted that although Table 1 looks authoritative, the figures are based on very weak data. I have extrapolated from Long's assessment of the accuracy of the poll tax to make assumptions regarding the total enslaved population both in Kingston and in Jamaica, applying that dubious measure called “common sense” in order to determine some ratios and using the data from 1788 and 1817 as controls over any wild inferences. The figures need further rationalization and should be treated as extremely tentative. Nevertheless, they do provide a rough guide to population patterns in Kingston over nearly a century.

From this imperfect data, we can make some assumptions about trends in the enslaved population of Kingston over time. Firstly, the enslaved population was considerable by British Atlantic standards. Indeed, Kingston had more slaves and free people of colour than any town in eighteenth-century British America. Between them Boston, Philadelphia, and New York contained 5,343 black people in the 1770s, accounting for less than seven per cent of the total population. Charleston had 6,300 black people, almost all slaves, amounting to fifty-five per cent of the population. Kingston had around 9,000 slaves in 1774 from a population of 14,200, and 16,659 slaves from a population of 26,478 in 1788 (nearly sixty-three per cent of the total population). There were also more enslaved people in Kingston than in Bridgetown, Barbados, by the start of the American Revolution. Bridgetown had 5,600 enslaved residents in 1773, which was forty per cent of a total population estimated at 14,000.Footnote 12

Secondly, the size of the enslaved population in Kingston varied over time, changing in accord with developments in the wider society. Overall, the enslaved population in Kingston increased in line with Jamaica's population growth, reaching a peak of 17,940 in 1817, when it was 5.2 per cent of the enslaved population. It was nearly as large in 1805, when there were 17,460 enslaved people in Kingston. If we take the difference between the numbers of slaves enumerated in the poll tax and the real numbers listed in 1788 to be indicative of numbers in 1805 rather than the preferred ratio from 1817, then the actual numbers in 1805 might have been as high as 18,876. Usually, the enslaved population in Kingston was between 4.5 and 5.5 per cent of the Jamaican enslaved population. There was a spike in 1788, when Kingston accounted for 7.4 per cent of Jamaica's slave population. This spike was probably due to the influx of loyalists and their slaves from the newly independent United States.Footnote 13 Most of these loyalists settled in Kingston. A report in 1784 to the Assembly of Jamaica noted that of 877 certificates of freedom offered to white foreigners between 1777 and 1784, 495 went to people living in Kingston.Footnote 14 A further spike after 1800 probably reflects the influx of refugees and their slaves from Saint-Domingue, most bound by their certificates of residence to remain in Kingston.Footnote 15 Possibly, although the population data for 1774 is very much guesswork, the lowest percentage of slaves in Jamaica living in Kingston may have been just before the American Revolution, when the plantation economy was especially prosperous.

Thirdly, enslaved people were always a majority of Kingston's population. Detailed figures from 1788 recorded in the local vestry minutes and tabulated in Tables 2, 3, and 4 show that enslaved people made up 62.9 per cent of the total population. Although, as was true in the Jamaican slave population overall, male slaves made up a slight majority of the enslaved population (52.3 per cent), female slaves were a greater proportion of all females in Kingston than male slaves were of all males. Female slaves were 69.8 per cent of the female population in 1788 and if we include free women of colour in this group, then this percentage increases to 84.6. By contrast, reflecting the disproportionate number of white males in the white population, male slaves made up 57.7 per cent of all males and, when free males of colour are included, 68.3 per cent of all males.Footnote 16

Table 2. Kingston's Slave Population by Sex and Colour, 1788.

Source: Kingston Vestry Minutes, 28 February 1788, Jamaica Archives.

Table 3. Kingston's Population by Status, 1788.

Source: Kingston Vestry Minutes, 28 February 1788, Jamaica Archives.

Table 4. Kingston's Population by Colour, 1788.

Source: Kingston Vestry Minutes, 28 February 1788, Jamaica Archives.

The large numbers of black and coloured women over white women may have contributed to a distinctive feature of life in Kingston, which is the extensive and open practice of concubinage of white men with black or coloured mistresses. Concubinage is too benign a word for what was often sexual exploitation. J.B. Moreton was most open on the matter, declaring in 1790 that even the most “honourable gentlemen” had slaves and even coloured daughters who were “lamblike lasses” available for “sport” after social occasions. He made the ribald comment that “when the ball or rigadoon is over” then a man can “escort her to your house or lodging and taste all the wanton and warm endearments she can yield before morning”. He also expanded upon the common trope of overtly lascivious coloured women, arguing that such women would be very upset if their male lovers showed restraint in their dealings with them.Footnote 17 There was a practical reason, also, why white men preferred concubinage with black or coloured women rather than entering into marriage with a white woman. Christer Petley argues that choosing a white wife was costly, as it meant having to provide the wife with an expensively equipped household in order to keep up “appearances”. “Keeping” a black or coloured “housekeeper” was cheaper, allowing a white man to live a more relaxed and moderate lifestyle in a less properly appointed house.Footnote 18

Finally, the enslaved population of Kingston was lighter skinned and possibly more likely to be native-born than the enslaved population as a whole. Most slaves (93.5 per cent) were listed in 1788 as “black” or of fully African descent. A proportion of enslaved people and a majority of free people of colour were described as “coloured”, meaning that they fitted into the complex hierarchy of various shades of colour that were characterized in Jamaica by terms such as “mulatto”, “sambo”, and “quadroon”.Footnote 19 In 1788, there were 1,079 enslaved persons (6.5 per cent of all slaves) and 2,690 free people of colour (eighty-two per cent in that category) who were coloured, making up 14.2 per cent of the total population and 18.9 per cent of the non-white population. The percentage of enslaved people who were coloured corresponds closely to what Higman and Gisela Eisner believe was the Jamaican norm at the end of slavery – about seven per cent or 23,000 slaves in 1834. Given that the percentage of Jamaican slaves in 1788 who were coloured rather than black would have been appreciably lower than in 1834, as a result of high mortality among slaves and a vibrant Atlantic slave trade, this high figure of coloured enslaved people confirms Higman's contention that slaves of colour were concentrated in Kingston.Footnote 20 If we add in the large numbers of coloured free people, the majority of whom were women, Kingston can be viewed as very much the centre of free coloured life in eighteenth- as well as nineteenth-century Jamaica.Footnote 21

ENSLAVED POPULATIONS

Kingston had two enslaved populations. One was the resident enslaved population who worked as domestics, tradesmen, boatsmen, and petty traders. The other population comprised transient Africans who arrived in Kingston having endured the Middle Passage and who were sold to local merchants and then resold to purchasers, mostly from the countryside, and who were then sent to work on plantations.Footnote 22 These transients may have numbered in their thousands at any one time. New scholarship has altered our views about how these Africans experienced their relatively brief but transformative time spent in Kingston – a period when they underwent the process of being commodified and made into enslaved people. Relatively little attention has customarily been given to this process of transformation, and usually scholars have relied on sensational texts such as that by Alexander Falconbridge, which depicted slave sales as riotous occasions – or “scrambles” – where African captives were the object of a frenzy of over-attention from buyers desperate to acquire their share of human flesh.Footnote 23

In a scramble, the so-called captain or factor set aside the upper deck of the slave ship, sheltered by canvas sails. The Africans stood in rows and, at a signal, prospective buyers rushed the slaves and marked out those they preferred. Falconbridge described purchasers rushing, “with all the ferocity of brutes”, taking hold of Africans with their hands or handkerchiefs or ropes. “It is scarcely possible”, he lamented, “to describe the confusion of which this mode of selling is productive […] The poor astonished negroes were so much terrified by these proceedings, that several of them, through fear, climbed over the walls of the court yard, and ran wild about the town; but were soon hunted down and retaken”.Footnote 24 Falconbridge's account came from the early 1790s, when demand for slaves far outstripped supply. It was, as he suggested, a dangerous way of selling slaves, likely to damage valuable “produce”. John Tailyour, the second largest “Guinea factor” selling slaves in Kingston between 1785 and 1796, told a correspondent that if he allowed a person to choose slaves before the date of the sale, “you have made an agreement which would undoubtedly ruin the sale of your Cargo, and when such a thing was insisted on, I would not choose to sell the Cargo”.Footnote 25 And it never worked in normal times, when ship captains and factors often had to bargain hard with purchasers and work out complicated credit terms to get rid of all their enslaved people. “Refuse” enslaved people – the old, sick, and diseased – were especially difficult to sell and occasionally were unceremoniously dumped on the waterfront, dying without medical attention in front of uncaring spectators.Footnote 26 It was an altogether unedifying process. As Kenneth Morgan notes, “the process involved the commodification of people, selling off the remaining slaves at the end of a sale rather like a shop-owner marking down the price of damaged fruit in order to sell his produce”.Footnote 27

Over time, however, ship captains came to favour selling wholesale to merchants who then sold on enslaved Africans at retail prices from their merchant houses in town. As early as the start of the eighteenth century, the Royal African Company sold slaves in Kingston from a building in the town rather than from the decks of ships. When Olaudah Equiano was delivered to Bridgetown at mid-century this practice was common. Equiano described being taken ashore to “the merchant's yard” where “we were all pent up together without regard to age or sex”.Footnote 28 One way in which we can see the evolution of slave-trading practices is how, by the mid-eighteenth century, most enslaved people were sold to merchants, rather than to planters, and in much larger lots than in the seventeenth century, usually between ten and forty but sometimes as many as 100 or more.Footnote 29 Path-breaking research by Louis Nelson into the architecture of slave traders’ houses, such as Hibbert House, a surviving eighteenth-century house once owned by Kingston's largest slave trader, reveals that the cellars of merchant houses were designed to be containment cells, secured by a single strong door with ventilation from a single barred window opening. Slaves were kept there for some time before being moved from the cellar and paraded in the rear yard and gallery.Footnote 30 These sales were painful. John Tailyour related to his cousin Simon Taylor, who had bought one sister but left the other – “a girl with one eye” – in Tailyour's store, that the girl was “crying most dreadfully” on account of being separated from her sibling.Footnote 31

The move away from selling aboard ship was codified in 1792 by the Assembly of Jamaica, who ordered that the sale of all newly arrived Africans “shall be conducted on shore”.Footnote 32 It made the process a very public one and connected it more closely to the commercial rhythms of Kingston. Buyers purchasing enslaved people at Hibbert's house likely collected their property from the rear piazza and then escorted them out via the side gate and down Duke Street. The newly purchased slaves would then be displayed to the public as they were transferred from town to countryside. Some observers were shocked by the way in which this was done. The editor of the Royal Gazette tut-tutted in 1791 that “the indecency of parading newly purchased Negroes through the streets has been frequently noticed”. He was outraged by a recent parade in which “a full-grown negro fellow in a very infirm state was led along Harbour Street without the least covering”.Footnote 33

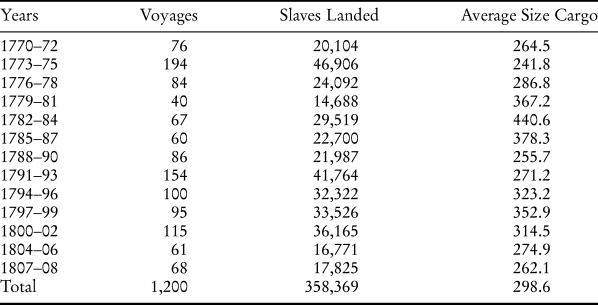

The Atlantic slave trade to Kingston reached its peak in the thirty years before abolition took effect in 1808. As Table 5 shows, Kingston received 358,369 slaves through 1,200 slave voyages between 1770 and 1808. This accounted for 40.5 per cent of the 885,545 Africans sent to the British Caribbean in this period and 34.8 per cent of all British slave voyages. Kingston was far and away the largest port of slave importation in Jamaica, accounting for eighty-nine per cent of all shipments.Footnote 34 “Guinea merchants” were doubtful that other ports in Jamaica had the infrastructure necessary to sell enslaved people. John Tailyour warned a correspondent not to sell except at Kingston for “experience has shown the danger of making sales at the outports, and I would not wish to make the trial myself […] I would not sell at Port Morant as no-one would come to a trade there”.Footnote 35 Only a proportion of these African captives remained in Jamaica. Many slaves were re-exported in the 1780s and 1790s, notably to Cuba, but also to Saint-Domingue, Louisiana, Savanna, Providence, Cartagena, and Trinidad. Between 1786 and 1788, Alexandre Lindo, the leading slave broker in Kingston, brought in 7,873 Africans and sold 7,510 as slaves, with 4,780 (73.6 per cent) re-exported. The percentage of enslaved people who died between arrival and sale was 4.6, close to mortality in the Middle Passage by the 1780s.Footnote 36 The percentages re-exported varied per ship, with all 180 slaves on the Snow John, which arrived in Kingston on 9 April 1787, being sold off the island. Similarly, in the 1790s, the numbers of slaves re-exported varied widely from year to year. Overall, 11,616 slaves, from among 85,258 Africans arriving in Kingston between November 1792 and November 1799, were sold to foreign buyers, mostly Cuban. But while virtually no enslaved people were re-exported in the booming years of 1793 and 1798 (215 and 655 respectively), many enslaved people were sold off the island between 1795 and 1797. In 1795, 4,214 slaves or 36.8 per cent of all enslaved people imported into Kingston were sent off the island on ninety-five ships.Footnote 37

Table 5. The Atlantic Slave Trade to Kingston, 1770–1808.

Source: Transatlantic Slave Trade Database. Available at: http://slavevoyages.org/; last accessed 25 November 2019.

Africans arriving in Kingston came from every slave exporting region of Africa, except the southern tip of the continent. The biggest region of exportation was the Bight of Biafra, which accounted for 43.8 per cent of enslaved people landed in Jamaica between 1776 and 1800 and 51.2 per cent between 1801 and 1808. The Gold Coast and Angola were sizeable areas of exportation to Jamaica, comprising nearly a quarter of slaves landed in the case of the Gold Coast between 1776 and 1800 and 17.6 per cent in the case of Angola. But enslaved people also came from Benin, the Windward Coast, Sierra Leone, and Senegambia.Footnote 38 Thus, the ethnic origins of enslaved people arriving in Kingston were diverse. That diversity was enhanced by how enslaved people were sold, gathered together from many nations in merchant yards and containment cells. It is thought that Jamaicans had strong preferences in favour of slaves from the Gold Coast and the Bight of Benin and were antagonistic to slaves from Old Calabar (Biafra), but slave price data from merchants’ accounts does not support such claims.Footnote 39 Winde and Allardyce (1773–1775) and Watt and Allardyce (1775–1776) opened up to the House of Assembly their records of twenty-nine slave shipments from six regions of Africa. As Table 6 shows, slaves from Benin, Senegambia, and the Gold Coast fetched a premium over slaves from Biafra and Sierra Leone. Nevertheless, the differences in price by ethnicity must be calibrated against a greater price differential by year. The seven slave shipments that they brokered in 1773 and 1774 (including two from the Gold Coast and three from Benin) fetched an average price of £58.79, but that price fell to £54.94 for seven shipments in 1775 and plummeted to £46.30 per slave for twelve slave sales in the war-plagued year of 1776. After war broke out between Britain and America in July 1776, Watt and Allardyce did not receive more than £48.11 per slave for any shipment and had four shipments that had “average prices” below, sometimes well below their average for the three years recorded of £47.31.Footnote 40

Table 6. Slave Sales by Year and Ethnicity, 1773–1776, Winde and Allardyce, Watt and Allardyce.

NB. Jamaica currency converts to sterling at a rate of 1.4:1.

Source: Journals of the Assembly of Jamaica, 1793, 9:149.

An even more pronounced pattern of relatively small differences by ethnicity and great differences by year can be found for thirty slave sales brokered by Barrett and Parkinson, William Ross, Allan and White, and William Daggers between 1789 and 1792. Between 1789 and 1791, slaves from the Gold Coast (1,355 slaves sold for an average price of £67.27) and Sierra Leone (131 slaves at £68.42) were more expensive than slaves from Biafra (3,826 at £65.72) and from the Windward Coast (£64.20). But these differences were much less than the differences between sales made between 1789 and 1791, when slaves were bought at an average price of £65.94 currency (£47.13 sterling) and seven slave sales made in 1792 (three from Biafra and three from the Gold Coast), when the price jumped by 26.7 per cent from the previous three years to reach £83.43 or £59.59 sterling per slave.Footnote 41 In other words, differences in price were more significant over time than differences in the ethnicity of captives. An enslaved person from the Bight of Biafra cost more to purchase in 1792 than an enslaved person from the Gold Coast did two years previously, even though Gold Coast slaves appear to have been more desirable to purchase than enslaved people from the Bight of Biafra.

All parties involved in the complex business of the Atlantic slave trade were highly sensitive to trade conditions, such as war, or the availability of credit, or the prices fetched for enslaved people at certain ports. There were surges and collapses in the slave trade to individual colonies based on merchants’ reaction to a host of separate pieces of business information.Footnote 42 They were especially sensitive to price changes. It is not accidental that high prices in 1773 and 1774 led to a surge in shipments to Kingston between 1774 and 1776. And a rapid decline in prices once the American War of Independence had broken out contributed to the number of slave voyages to Kingston reducing from an average of sixty-five between 1774 and 1776 to just fourteen per annum between 1777 and 1782. The extraordinary jump in prices after the Saint-Domingue revolt, started in 1792, made Kingston an attractive destination for slaving captains, especially as sugar prices increased and as planters made large excess profits. The wealthy Kingston-based planter Simon Taylor, for example, saw his net profits from sugar jump following the start of the French Revolution from £17,639 in 1788 to an average of £32,635 per annum between 1789 and 1792, with a peak of £42,555.65 net profit in 1791.Footnote 43 To cater to this growing wealth, the number of slave voyages into Kingston increased from thirty-five to seventy-five from 1792 to 1793 while the numbers of the enslaved landed jumped from 9,791 to 20,507. Similarly, slave imports jumped from 13,384 in 1799 to 19,019 in 1800 when slave prices increased from £58.54 in 1798 to £72.24 in 1799, according to data from the books of Aspinall and Hardy and Hardy, Pennock and Brittan.Footnote 44

Table 5 shows frequent surges and slumps in the slave trade: it was buoyant before the American Revolution and then experienced a dramatic drop during the American War of Independence. 1780 marked the nadir, with just 4,091 slaves arriving on the island. War-related problems were one reason for the decline. Another problem reducing slave traffic to Jamaica was extremely low prices. In 1779, for example, 258 enslaved people from the Gold Coast on board the Rumbold fetched just £32.75 per slave, a decline of eighty-five per cent from what Winde and Allardyce had received for 410 Gold Coast enslaved people arriving in 1775.Footnote 45 Slave traders tried to deal with war problems by sending enslaved people in much larger shipments – the average size of slave shipments was 440 slaves between 1782 and 1784, compared with 241 between 1773 and 1775. The end of the war saw a spurt in slave voyages, with 14,654 enslaved people landed in 1784. This was followed by a decline as competition for slaves from Saint-Domingue in the late 1780s proved too intense for Jamaicans to cope with. Between 1786 and 1790, the prices that traders achieved in Saint-Domingue – prime adult male slaves fetched 40.8 per cent more than in Jamaica – reached levels that were not to be surpassed until the mid-1840s in Cuba.Footnote 46 Consequently, the supply of enslaved people to Kingston reached a post-Seven Years’ War low in 1788 when only 3,613 enslaved people were landed. Nevertheless, slave prices were very high, perhaps because supply was so short, especially in 1792. A trader commented that “even indifferent negroes command very high prices” and that slave prices were at their highest point for seventy-five years.Footnote 47

The response to high prices in 1792, as we have seen, was a spurt in slave trade numbers in 1793. This boom resulted from three interrelated things – turbulence in the Saint-Domingue coffee and sugar markets as slave rebellion threatened white control; the sudden emergence of abolitionism as a political force, making fearful planters stock up on enslaved people in case the trade was suddenly stopped; and, most of all, booming sugar prices, as Britain took advantage of French disarray by opening up re-exportation to foreign markets. But the boom ended almost as soon as it started. The immense importation of enslaved people into Kingston led to a glut, and by July 1793 “the rage for selling Guinea cargoes” had “considerably subsided”. Moreover, slave-trading merchants in Britain were afflicted by a major credit crunch in Britain beginning in February 1793. The outbreak of the French Revolution also raised costs of shipping and insurance from Africa, while yellow fever raged throughout the island and throughout the Americas. Slave sale prices quickly declined. Nevertheless, the numbers of enslaved people entering Kingston only fell slightly, to an average of 12,124 enslaved people imported per annum between 1794 and 1800.Footnote 48

Planters continued to prosper in the 1790s thanks to high sugar prices and beneficial trade investments. The boom led planters to invest heavily in land, machinery, and enslaved people to take advantage of rising prices through dramatically increasing productivity. At the same time, foreign powers, notably Spanish Cuba (the principal beneficiary of Saint-Domingue's collapse), took advantage of high sugar prices and more extensive and more fertile lands as well as investment in industrial plant to ramp up their sugar-producing capacity. Kingston merchants benefited for a time, as we have seen, exporting increasing numbers of enslaved people to Cuba and other foreign places. But rising Cuban sugar output eventually led to falling prices for overextended Jamaican planters who, David Ryden argues, were trapped in an upward cycle of “irrational exuberance” in the 1790s. Economic reality, however, caught up with overproducing and over-indebted planters, who were paying over the odds for fresh inputs of African workers to grow more sugar than a glutted British market could handle. Jamaican planters, who specialized in low-grade sugar, were especially badly affected by the end of the sugar boom. A crash in the speculative market for sugar in Hamburg in 1799 led to a bust in sugar prices and the collapse of European sugar markets. Planter income plummeted and many could no longer afford slaves. Between 1804 and 1806, annual slave sales were just 5,590, with only 4,473 slaves landing in Kingston in 1805. The imminent abolition of the slave trade meant that sales picked up in 1806 and especially in 1807, as planters took their last opportunity to buy enslaved people before such purchases became impossible. Jamaican estates were still profitable if well run, but the overextension of the 1790s led to many planters struggling in the 1800s. One indication of their struggles was a decline in land prices outside Kingston, which reduced by seventeen per cent between 1800 and 1805 and by a calamitous twenty-nine per cent between 1805 and 1810.Footnote 49

THE PROFITABILITY OF SLAVE TRADING

The slave trade was large and very lucrative for those involved. Morgan notes that the commissions that John Tailyour received from “Guinea trading” were £36,792 sterling between 1785 and 1792, allowing him to retire in comfort to his native Scotland, where he died on 11 February 1816 with a net worth of nearly £100,000. He made an annual profit of between £5,000 and £6,000 sterling. His partners, Peter Ballantine and James Fairlie, died around the same time, with £26,025 and £46,294 respectively in non-landed property.Footnote 50 Tailyour's peak years of slave trading were in 1793 and 1794, when he was factor for twenty-eight slave voyages and 9,262 slaves. In these years, his firm sold twenty-two per cent of all slaves landed in Jamaica. Between 1786 and 1796, they sold eleven per cent of Jamaican slave cargoes.Footnote 51 Alexandre Lindo, the most substantial slave trader in Kingston, was so wealthy that he could arrange to lend the amazing sum (most of it gained through credit, of course, which was to be a problem when Napoleon reneged on the deal) of £500,000 to Napoleon for his campaign in Haiti in 1802 and 1803. Thomas Hibbert, Lindo's predecessor as Kingston's biggest slave trader, rose from nothing (his family had been weavers in Manchester) to great wealth during his forty-six-year residence in Kingston. When he died, he left three nephews £215,000 each. They later also became involved in slave trading.Footnote 52

Yet, in 1788, Kingston merchants realized that there was a growing abolitionist movement in Britain with massive public support whose adherents were determined to abolish the trade in slaves with Africa. Taylor was appalled that Britain could even consider ending the slave trade, thinking in 1788 that the discussion about this matter showed that a “general madness has pervaded all ranks of People in Britain”, encouraging them to “interfere with a Trade they seem not to understand and to pass laws to Rob their fellow subjects in the West Indies of their property”. Writing on the eve of the fall of the Bastille in Paris, he lamented that “I cannot think it possible a trade so profitable to Britain and necessary to the Colony's can be thrown away to please a parcel of Rogues and Fools”. Abolitionist actions, he noted, had an unintended effect. News of movements to abolish the slave trade alarmed planters and “the fear of it makes Slaves in very great demand and greater averages are made now than were ever known before”.Footnote 53

Kingston merchants had no reason, therefore, to believe that they would participate in what proponents of the abolition of the slave trade argued was a sensible readjustment of the Jamaican plantation economy to make planters care for their existing enslaved people. Supporters of abolition in the House of Lords, such as the Duke of Gloucester, thought that planters would not be harmed by abolition as they had been lured into bad business practices by their reliance on the slave trade. Without fresh inputs of slave labour encouraging bad behaviour, he argued, planters would be forced to treat their workers more humanely.Footnote 54 In the debates on abolition, however, Kingston slave traders were condemned for their willingness to sell enslaved people in wartime to enemies who were increasing their enslaved populations and plantation output at Britain's expense. The British parliament passed an act in 1806 forbidding merchants from trading enslaved people with foreigners. And, unlike what happened in 1834, when slave owners were compensated for their losses from their property being freed, no Kingston merchant was given money to compensate for the loss of a very lucrative business.Footnote 55 While there was some concern about what would happen to the £2,641,200 that Liverpool reputedly had at stake in the Atlantic slave trade in 1807, the losses of Kingston merchants from slave abolition were not considered.Footnote 56

What happened to Kingston slave factors when the abolition of the slave trade occurred is an unstudied topic. Thus, the conclusions offered below are very tentative. It seems, however, that the ending of the slave trade in 1807 did not dampen economic growth in Kingston. Land prices, as we have noted, continued to rise in the first decade of the 1800s and mansions belonging to merchant princes continued to be built in Kingston's suburbs. The commercial life of Kingston remained buoyant despite the closing of its most significant trade. What seems to have happened is that Kingston merchants used their contacts in Spanish America to whom they had sold enslaved people in the 1790s to undermine Spanish commerce by importing cheap and desirable manufactured goods acquired out of Britain from its initial burst into industrialization. Adrian Pearce calculates that, in 1807, the value of British exports to Spanish America, mostly going through free ports in the Caribbean, of which Jamaica's was by far the most important, was in the region of £3–4 million (or 13 million pesos), making up about six per cent of total British exports. It is difficult to know how much of this money was routed through Kingston, but Pearce suggests that the town was the major entrepôt through which British goods reached Spanish America.

This market was a rich field for British manufactured goods, helping to stimulate industrialization in Britain and providing streams of money, including precious bullion, for Kingston middlemen. As Pearce suggests, this trade was especially important between 1806 and 1808, when exports, legal and illegal, to Spanish America peaked and helped to compensate for the wartime crisis in British trade with Europe in these years. The exact amount of trade and bullion that passed through Kingston to Spanish America is unclear, but it must have been of the order of £1–2 million sterling per annum in the first decade of the 1800s. That amount of money was of an order of magnitude greater than the value of the slave trade, which probably brought in around £1 million in a year only in 1793, when slave imports topped 20,000, and £300,000–400,000 in the dead years of the mid-1800s.Footnote 57 As Reid and Ryden explain, Kingston's “nimble” traders quickly readjusted to the changing imperial economy by transferring their capital from slave-trading ventures into conveying manufactured goods from Britain to Latin America. Thus, they argue, it was not the merchants who organized the slave trade who suffered most from its abolition, but the planter class, whose fixed investment depended upon slavery, who were especially financially affected.Footnote 58

THE ENSLAVED EXPERIENCE

The records that survive from Kingston contain little information about how slaves lived, except when they are written about as accessories or impediments to how whites went about their lives. We have no direct testimony from an enslaved person from Kingston in this period and not much data about how slaves worked, how they spent their relatively limited leisure time, or what they thought or felt. All of the evidence we have about enslaved life in Kingston between 1770 and 1815 comes from white-created sources. These sources tend to be highly negative about black Jamaicans’ capacity. Occasionally, a slave is treated favourably in the white press, as in 1791 when it was noted how “a negro fellow who died last week” had amassed a small fortune of £200 “following the very opposite professions of Bucher and chimney sweep, Cook and Gardener”. The report concluded, however, that the slave had bequeathed this large sum to his mistress – a statement that stretches plausibility.Footnote 59

More often, however, slaves are mentioned only as being public nuisances, such as the slaves who turned up to every funeral procession to “insult the feelings of those who occupy the succeeding chaise” and who disrupt religious services by talking loudly. The author thought that the most suitable punishment for such people would be flagellation.Footnote 60 The underlying tone in which slaves were discussed was one approaching contempt. The Royal Gazette complained that it had been reported that “the body of a negro, in a putrid and offensive state”, had been lying on the road for several days without being removed by legislative fiat. The newspaper expressed little sympathy with the dead man but did think that he should have been removed from the road as he was “offensive to decency”.Footnote 61 Instead, writers to the paper tended to congratulate themselves for taking the amelioration of slavery seriously. One writer noted how a “woman was prosecuted for her severities against her negroes” and concluded from this not that slaves were badly treated but that Jamaicans were willing to prosecute whites when they did not act as they should.Footnote 62 Assumptions about the character of the urban enslaved from white sources, however, show unremitting hostility. White hostility to enslaved people in Kingston was aggravated not only by the constant contact they had with enslaved people, but by the nature of urban slavery, in which enslaved people tended to be relatively well-treated and independent domestics or skilled tradesmen and in which the gap between the enslaved and the free coloured populations was much smaller than on the plantations. The enslaved had more possibilities in Kingston than on the plantation not only to acquire competence through self-hiring, but to challenge, through their comparative affluence and ability to create lives for themselves separate to those imagined for them by their owners, the underlying principles of white supremacy. The Royal Gazette argued ten years earlier, for example, against slaves being able to hire themselves out for wages because they felt slaves would not work for money but instead were satisfied with “Idleness, Drunkenness, Gaming and thievery”.Footnote 63

Urban slavery was different from slavery in general because the jobs that urban enslaved people did were different from those on the plantation. They were engaged in a variety of artisanal activities but were concentrated mainly in ship carpentry, building and road construction, furniture making, coppering, smithing, tailoring and seamstressing, cobbling, and some limited processing of agricultural products. The urban enslaved were much more likely than plantation slaves to be skilled in a number of occupations and described in runaway ads as “jack of all trades”.Footnote 64 An example of the multiple skills the urban enslaved had can be seen in an advertisement by Stephen Prosser in 1780 seeking to sell “a young negroe wench” in which he described his enslaved property as being not only “a good cook”, but as someone who could also “wash and iron, and is a little of a semptress and used to marketing”.Footnote 65 Visitors to Jamaica were occasionally impressed at the skills of urban enslaved people. Johann Waldeck, a German traveller who spent some time in Kingston during the American War of Independence, marvelled at how the nineteen enslaved people owned by his friend, a master carpenter, “finish the finest cabinet work, mostly from mahogany”. They had been trained so well, he asserted, that they did “the most excellent cabinet work”, allowing his German friend to “no longer work” and amass enough money to become a real estate speculator. Waldeck “was surprised at how competent the black slaves could be”.Footnote 66

Some of these jobs brought enslaved people money and made them closer in function to the jobs done by free people of colour. But some jobs were very unpleasant and even less desired than working as a plantation slave. A fairly large number of enslaved people were employed by the government in public works schemes doing hard repetitive work while being organized in gangs under the supervision of slave drivers. For example, in August 1805, enslaved people from the heavily populated Kingston workhouse were engaged in digging “the foundations of the new bridge to be thrown over the town gully”. Some enslaved people were also employed as sailors. A newspaper advertisement in 1800 asked for owners to provide “sailor negroes in such Gangs as may be required with Tickets”. Most enslaved people, however, especially female slaves, worked as domestics. Lorna Simmonds estimates that two thirds of Kingston slaves in the early nineteenth century worked within urban households or in adjoining “negro yards” as housekeepers, in transport or as waiting men or cooks.Footnote 67

What is striking about all these jobs is that they were public facing. Few urban enslaved people experienced the anonymity common in the countryside for most field hands, who could avoid contact with whites most of the time.Footnote 68 Urban enslaved people were constantly present, either as workers or as participants in the flourishing urban slave markets. Such markets were formally regulated in 1781 by an Act of Assembly. They operated daily and were accompanied by hawking or peddling in the street. Enslaved people formed a counterpoint, perhaps an opposition to regular shopkeepers, operating on the fringes of legality. Many lived close to the edge and were thought by white observers to have to resort to thievery out of desperation. A report in the Columbian magazine for 1797 argued that Kingston slaves got so little money or food that they were required “to commit any depredations on the community when the toils of the day are done, for mere subsistence”.Footnote 69 Nevertheless, the real difference between work done by the urban enslaved and plantation slaves was that in Kingston enslaved people had multiple opportunities to self-hire. Indeed, in the essential and lucrative maritime trades, self-hiring by enslaved people was customary practice. The nature of enslaved work in the Kingston port was to enhance the fluidity of enslaved life, as enslaved port workers tended to work for themselves as much as for their owners. A writer noted in 1790 that most work relating to shipping, including that to do with naval ships of war, was “all under the care of negroes”. He concluded that in every case, “one is a chief who has two other negroes, being the property of some of the inhabitants of Kingston or Port Royal”. These masters “let then out to hire to themselves; that is they expect a certain sum from them daily or weekly, for six bitts to a dollar a day for each negro”.Footnote 70 Enslaved workers were thus able to make a bit of money on the side from their self-hire, meaning that urban slavery was more permeable and more variegated than slavery elsewhere on the island.

As in antebellum New York City, Kingston enslaved people developed an oppositional culture to that of whites.Footnote 71 Many whites found slaves’ attitudes to authority worrying. Kingston enslaved people lived violent lives: ninety-five published coroners’ reports in the early nineteenth century detail twenty-four accidental drownings, twenty-two cases of sick Africans thrown overboard when entering Kingston harbour to be sold as slaves, nineteen suicides, and sixteen murders. Whites were concerned that violence might be directed against them. It was not – there were no slave uprisings in the town in the nineteenth century. But there were at least two conspiracies discovered before they could be implemented, as well as a mutiny on 27 May 1808 of fifty-four African recruits to the 2nd Regiment, mainly from the Gold Coast. The mutineers killed two white officers. Retaliation was brutal, with ten mutineers killed and several shot by court martial and others transported to British Honduras. The slaves suspected as plotters in two conspiracies discovered in 1803 and 1809 were also executed. The most dangerous plot appears to have been that of 1809, where “creole boys” were thought to have plotted with Africans, black soldiers, and French and Spanish refugees to “get rid of the whites” and have enslaved people “turn on their masters”. Such plots were extremely dangerous in the immediate aftermath of Haiti. And this plot also resulted in harsh retribution against the ringleaders.Footnote 72

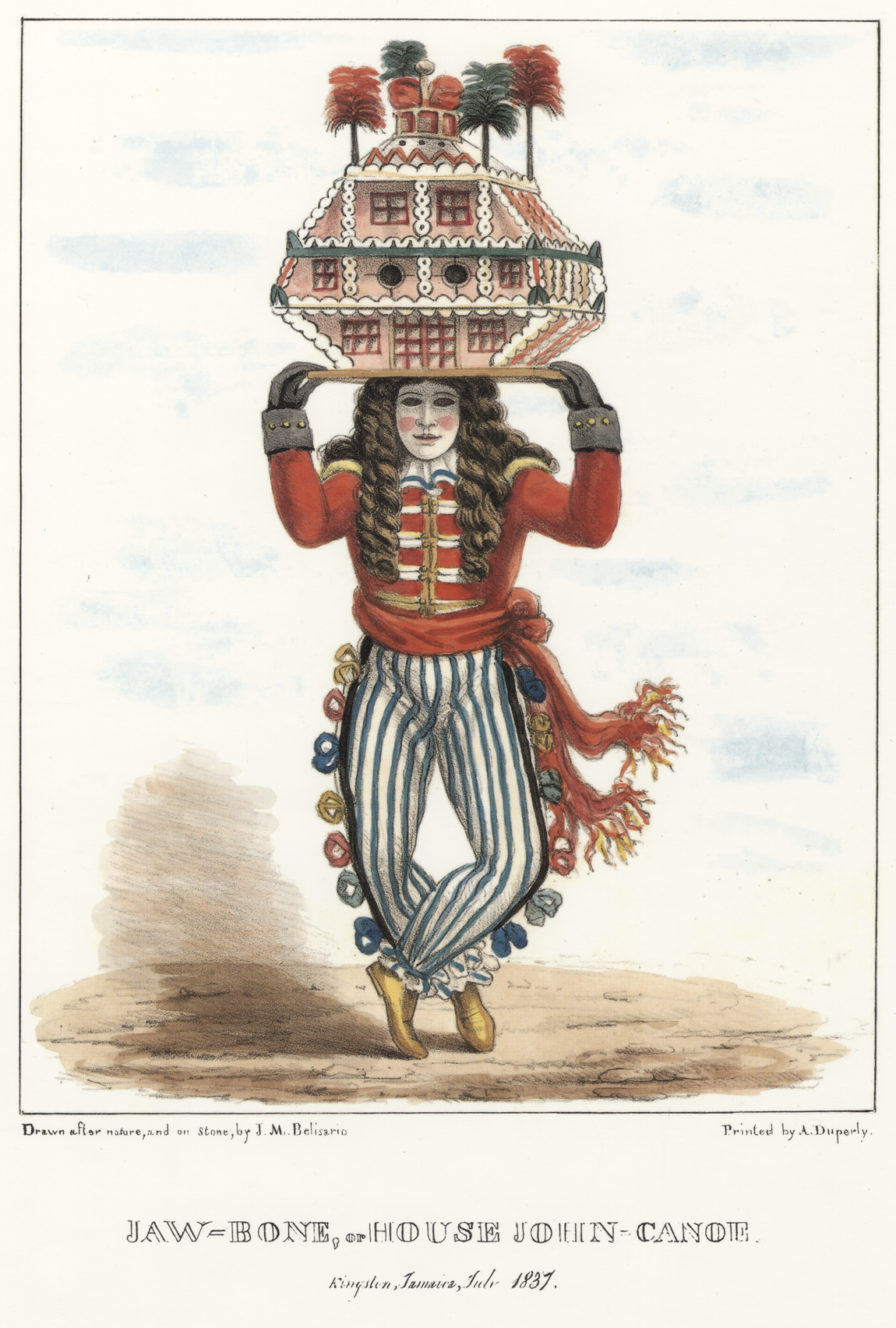

Oppositional culture also featured in what became by the end of slavery one of the most characteristic forms of black culture: the carnivalesque black mimicry of white authority represented in the Jonkonnu or John Canoe ceremonies, held around Christmastime each year (Figure 2).Footnote 73 They are pictured beautifully in Isaac Belisario's Sketches of Character prints published just before the end of the four year period of apprenticeship of ex-slaves in 1838.Footnote 74 John Canoes were popular black entertainers who paraded around Kingston wearing outlandish masks and costumes, which included skirts, wigs, fans, plumes, and whips. As Kay Dian Kriz notes, these “[a]ctor-Boys satirize the very notion of maintaining boundaries in a place like Jamaica”, criss-crossing racial, class, and gender divisions that white creoles usually maintained through force and legislation.Footnote 75 Whites liked to pretend that John Canoes were creatures of fun and harmless entertainers, but written and visual depictions suggest that these performers were often aggressive and faintly menacing. In a popular memoir, Tom Cringle's Log, published in 1833, Michael Scott noted that the Kingston militia was called out “in case any of the John Canoes should take a small fancy to pillage the town, or to rise and cut the throats of their masters, or any innocent recreation of the kind”.

Figure 2. “Jaw-Bone, or House John-Canoe”.

John Canoes and Set Girls were distinctly urban creatures. John Stewart noted in 1823 how “the Negro girls of the town (who conceive themselves far superior to those on the estates, in point of taste, manners and fashion)” joined together in groups called the blues and the reds in their finery, “sometimes at the expense of the white or brown mistress who took a pride in shewing them off to the greatest advantage”.Footnote 76 These “actor-boys” embodied disorder. The first visual depiction of them in William Elmes’ Adventures of Johnny Newcome (1812) is at a “negro ball”. The John Canoe character is ludicrously caricatured as a parody of long-gone British male fashion and is a vaguely menacing figure among grinning, dancing, indolent blacks. Belisario, painting for a middle-class audience at the moment of emancipation, tones down the menace, but even so, his Set Girls and Actor-Boys or John Canoes are decked out in outrageous military garb.Footnote 77

One significant difference between urban enslavement and plantation slavery was that enslaved people in Kingston lived cheek by jowl with white people. Residential segregation was limited until near the end of slavery, when concentrations of enslaved peoples’ residences began appearing at the edge of the town. Enslaved people were often housed with their owners, or in closely adjacent “negro” yards. Whites complained that they could never escape the attention of enslaved people. The black presence was hard to disguise in the town, in ways that made the town more obviously a mixture of black and white than, ironically, the plantation, where enslaved people worked and lived often at quite a distance from the great house. As Ann Appleton Storrow noted in 1792, “the Town of Kingston has some beautiful houses in it, [and] was it uniformly well-built it would be an elegant one, but you often see between two handsome houses, an obscene negro yard, which spoils the effect entirely”. Another writer was more direct in his condemnation of enslaved spatial presence alongside whites: Kingston was “a wretched mixture of handsome and spacious houses, with vile hovels and disgraceful sheds”.Footnote 78

The principal disruption that was practised by John Canoes was to transform the spatial location in which enslaved people resided. Kingston enslaved people often lived with white people but were generally invisible in the homes in which they dwelled: the street was their normal locale. During the Jonkonnu festival, however, a spatial inversion occurred, during which black entertainers invaded the spaces of white authority. Not only did John Canoes and Set Girls dress up and address whites with great familiarity, singing “satirical philippics” against masters that whites may have thought were still within the bounds of “decorum” but which may have had a more spirited edge, they also invaded the houses of white merchants, drinking with the owners in ways that “annihilated the distance” between white and black. Some whites found this threatening. One observer wrote that the performers “completely besieged my room” and that she was then “forced to listen to their rude songs, which I should fancy must be very like the wild yelling and screaming that we read of in African travels”.Footnote 79 The invasion of the house was pointed. The lead performer, as Belisario pictured in an especially fine print, wore an elaborate model of a house on his head (Figure 2) that may have been destroyed (as it is in contemporary re-creations) at the end of festivities. The house on the head of the enslaved person was highly symbolic. Nelson suggests it was a visual representation of what enslaved people believed – that the whole edifice of white power, as represented in merchants’ tall buildings in Kingston, rested on the heads of enslaved people.Footnote 80 Kingston was a wealthy and flourishing town. But black people knew that its prosperity rested squarely upon slavery and the slave trade and, at bottom, upon the bodies of enslaved people.