Introduction

Vietnamʼs first labour code since the countryʼs reunification was issued in 1994. There have been several revised versions of the code since then. However, the 2012 Labour Code is considered ‘groundbreaking’ in the nationʼs industrial relations history because it creates a mechanism for social dialogue between worker/management committees, and regulates all firms and industrial sectors covering about eight to ten million workers (Better Work 2013). The Code, which is considered the ‘mother law’ in the field of labour, provides a relatively complete range of contents related to the management and use of labour, the work of employees, and the adjustment of labour and other social relations in response to practical needs. According to the International Labour Organization, Vietnamʼs labour legal framework, including the 2012 Labour Code and its detailed documents and implementation guidelines, is one of Asiaʼs progressive labour law corridors. Compared to previous versions, one of the essential novelties of the new code is the provisions related to labour contracts (MOLISA 2018).

This paper focuses on assessing the influence of the code on the labour outcomes of different groups of workers disaggregated by location and migration status. Urbanisation and migration issues are crucial because they are the main focuses of labour policies. As suggested by the World Bank, labour policy should avoid distortionary interventions that prevent job creation in urban areas and global value chains and provide a mechanism to protect the most vulnerable workers, such as rural and migrant workers. A distortionary intervention may impair the advantages of agglomeration and global integration, while a lack of protection mechanisms may reduce living standards and cause a social cohesion limitation (World Bank 2013). Additionally, two contrasting trends exist between demographic and physical urbanisation in Vietnam. This fact reveals that labour force growth is slowing down, and labour mobility is limited. It implies a failure of realising agglomeration economies and a slow productivity growth. The migrant workers group is a vital determinant of the problems. However, this group of workers suffers from many disadvantages regarding the accessibility of critical public services, economic opportunities, and the social security system. The economy must continuously improve its productivity and efficiency to achieve its goal of becoming an advanced economy in the next generations. The pattern of urbanisation is the decisive factor for this improvement (World Bank 2020).

Several studies have explored the impact of labour laws in Vietnam, but most are from non-economic perspectives. This paper uses the Vietnam Labour Force Survey (VLFS) to evaluate the economic effects of the 2012 Labour Code introduction. VLFS was chosen because it contains nationally representative data on employment, contract types, income, location, and migration status. Both difference-in-differences (DID) and fixed-effect (FE) models are used to investigate the effects of the promulgation. The innovation of our study includes: (i) this is the first paper that, to our knowledge, comprehensively examines the impact of a labour law enactment disaggregated by workers’ location and migration status in this country, and (ii) it combines DID and FE methods to measure effects of the enactment for both cross-sectional and short-panel data.

Institutional settings

The 2012 Labour Code was developed to provide regulations on the rights and obligations of employees and employers, labour standards, and principles of labour use and management to protect the rights and interests of both sides in the labour relations, to construct harmonious and stable labour relations, and to contribute to the promotion of productivity, quality and progress in the labour sector, and efficiency in the utilisation and management of labour. This version of the Code was expected to institutionalise further the Communist Partyʼs goals, views, and orientations as reflected in the Partyʼs recent documents, to strengthen and continue to advance state management in the labour sector, to respect the autonomy of enterprises in production and business, to enable the right to negotiate and self-determination of the parties in labour relations following the labour legislation, to codify, amend, and supplement provisions in the current legal system on labour and labour management to suit the market economy, and to consult and selectively absorb the experience of developing labour laws of other countries and integrate the content of international treaties that Vietnam has ratified or acceded to (MOLISA 2012).

Evaluating the formation and implementation of the law, the CMinistry of Labour, Invalids and Social Affairs (MOLISA) stated that the Code covered matters related to the management and use of labour and employment of employees, and reasonable adjustment of labour, as well as other social relations such as employment contracts, collective bargaining agreements, wages, insurance social insurance, labour disputes, and dispute settlement mechanisms. It also clearly defines the roles, responsibilities, and powers of state management agencies and other labour-related organisations (MOLISA 2018). However, the Code also has some limitations: (i) it has not yet institutionalised the contents connected to the rights and obligations of workers, labour relations, and the labour market of legal documents ratified after it, such as the 2013 Constitution and many other laws and policies; (ii) some of its provisions have not yet kept pace with the transition to a market economy such as regulations related to labour contracts, wages, working hours, employment, and severance pay, or have not yet met the requirements of international trade integration, including regulations on collective bargaining, settlement of labour disputes, and strikes,; there is also no equality between different types of enterprises, and moreover, there is have no specific guidance document to implement processes and regulations in practice; and (iii) some of its provisions are ambiguous and abstruse, making it difficult to enforce. The guidance to apply it in localities also still needs to be improved. Its dissemination to employers, employees, and local labour management agencies still needs to be made more robust (MOLISA 2018).

Most changes in this version of the Code focused on provisions related to labour contracts. From a firm’s perspective, however, the Code favours workers while limiting the employer’s flexibility. When entering a labour contract, the Code requires the employer and the worker to sign a contract before the work starts. This provision prevents employers from evading their obligation to pay insurance and protects other rights and interests of employees. The law also bans employers from holding identification cards and qualifications of employees during the hiring process. Employers are also not allowed to request employees to pay money or assets to ensure they work under the contract. However, the employer can require employees to sign an agreement to protect business and technology secrets and to pay compensation if they violate that agreement. Regarding the types of labour contracts, the law offers guides on how to move from a definite contract to an indefinite contract and from a contract of less than 1 year to a 2-year fixed-term contract. Probationary work is mentioned for the first time in this law. The employerʼs rights to the unilateral termination of labour contracts are also stipulated. Moreover, the code specifies additional provisions to ensure compliance with labour contracts when a contract becomes totally or partially invalid (Lee and Svanberg Reference Lee and Svanberg2013).

The Code does not distinguish between urban workers and rural workers, nor does it distinguish between local and migrant workers. In 2013, the countryʼs labour force comprised 52.2 million employed workers and one million unemployed. The labour force participation rate in rural areas was higher than in urban areas (81.1% versus 70.3%). However, the proportion of trained workers in urban areas was considerably higher than in rural areas (GSO 2013). Vietnam has the majority of the population residing in rural areas. Industrialisation and modernisation have led to economic restructuring and migration from rural to urban areas. Of more than 5.6 million internal migrants in 2014, 29% were rural-to-urban migrants and only 12.1% were urban-to-rural migrants. Rural-to-urban migration is an essential factor that increases the urbanisation rate. However, in Vietnam, there are still many policy barriers to migration, especially policies on household registration books. Shifting in demographic characteristics also limits migration freedom (UNFPA 2016a).

In principle, all employees are contracted. However, in reality, the rate of signing labour contracts is still low, especially among rural and migrant workers. In 2013, 39.4% of total employees had labour contracts, of which indefinite contracts accounted for 26.2% and term contracts accounted for 13.2%. The percentage of women without a written labour contract (47%) was higher than that of men (30.9%). The incidence of workers with written employment contracts in urban areas was 62.3% compared to 27% in rural areas (GSO 2013). Migrant workers are still more disadvantaged than local workers, in terms of job stability. In 2015, the proportion of salaried migrants with indefinite labour contracts was only two-thirds of that of local workers (30.9% versus 54.4%). Meanwhile, the proportion of migrants with a labour contract of less than 3 months or without a written contract was higher than that of local people (32.2% versus 27.2%). Thus, migrant workers are more vulnerable to employment risks than local workers (UNFPA 2016b).

Enterprises may also enter into wrong contracts to reduce labour costs. The most common types of false contracts include using service contracts instead of labour contracts, using labour supply contracts instead of sub-contracts, using oral agreements or contracts of less than 3 months instead of contracts of 3 months or more, or signing a definite term contract more than twice in a row. Such false signing is mainly aimed at avoiding the obligations of social insurance and health insurance. We can see it by comparing the number of people with mandatory social insurance cards with the number of wage earners in 2014, which was 10.8 million people compared to 18.8 million people, or 57.4%. The wrong contracts can clearly affect the workers’ welfare (MOLISA 2014; MOLISA 2018).

Literature review

This paper evaluates the impact of a Vietnamese labour law on workers’ outcomes. The law can be considered as employment protection legislation (EPL) because it protects workers from firing or relevant welfare loss. Theoretically, labour regulations may affect employment in several ways. Increasing labour costs can challenge the labour supply or serve as a wage floor (Nataraj et al Reference Nataraj, Perez-Arce, Srinivasan and Kumar2014). Moreover, if firms do not provide fairness at work due to the adverse selection effect, dismissal regulation may drive up growth in labour supply (Adams et al Reference Adams, Bishop, Deakin, Fenwick, Garzelli and Rusconi2019). The influence of EPL on earnings is inconclusive. If employers want to compensate for increased firing costs, wages may decline. On the contrary, the insider–outsider theory of employment implies that some provisions of EPL can enhance the bargaining power of a group of insiders, that is, employed workers, which drives an increase in their wages (Lazear Reference Lazear1990; Lindbeck and Snower Reference Lindbeck and Snower1988). Notably, the association between theoretical frameworks on EPL and the empirical literature has been relatively weak. Typical empirical works may consider some theory a rough guide but do not strictly rely on it to determine structural parameters (Holmlund Reference Holmlund2014).

Some economists have attempted to quantify the relationship between labour regulations and urban–rural disparities. In the 1990s, they used to think that labour policies tended to increase labour cost in the formal sector and lower the demand for labour, increasing the labour supply in the urban and informal sectors. This view is based on Harris-Todaroʼs (Reference Harris and Todaro1970) two-sector model, which argued that high urban wages have attracted people to migrate from rural to urban areas, leading to unemployment while seeking employment. Within the model, migration would occur continuously until the unemployment rate brought down the expected urban income (wage multiplied by the likelihood of finding a job) to equal to rural income. Subsequent evidence showed that wages and unemployment have an inverse relationship due to the wage curve (Freeman Reference Freeman, Rodrik and Rosenzweig2010). Besley and Burgess (Reference Besley and Burgess2004) investigated the association between state reforms of the Industrial Disputes Act and manufacturing performance in India. They revealed that enhancing worker protection negatively affected registered or formal firms in terms of output and employment but positively affected unregistered or informal firms in terms of output. The legislation was also seen to hurt the poor in urban areas. Our research also benefits from literature exploring the impact of labour policy on employment and social insurance (Gallagher et al Reference Gallagher, Giles, Park and Wang2015; Cheng et al Reference Cheng, Smyth and Guo2015; McKenzie Reference McKenzie2017) and earnings (Card et al Reference Card, Ibarraran, Regalia, Rosas and Soares2011; Andalon and Pages Reference Andalon and Pages2008; Bosch and Manacorda Reference Bosch and Manacorda2010).

Substantial literature has been conducted on the links between labour regulations and immigration or internal migration. For example, Sá (Reference Sá2011) insisted that immigrants are less aware of their rights than natives because they are less familiar with the new country than natives. Therefore, although EPL does not differentiate between natives and legal immigrants, the second group may be less affected by the legislation. An explanation for the lesser awareness is their lower incidence of union participation. Skedinger (Reference Skedinger2010) stressed that, in principle, permanent workers are protected better than vulnerable workers such as immigrants. Other valuable works investigate the impacts of EPL in OECD countries (Causa and Jean Reference Causa and Jean2007; Kahn Reference Kahn2007) and China (Li and Freeman Reference Li and Freeman2015; Meng Reference Meng2017).

Other scholarly literature involves the short-run effects of labour regulations. Theoretically, labour laws may affect employment in the short run. A stricter working time protection may result in unemployment because firms lay off workers in response to the legislation. However, this effect cannot last in the medium and long term as firms invest more in firm-specific human capital and enhance their organisation and technology as an adjustment to the regulation (Deakin et al Reference Deakin, Malmberg and Sarkar2014). Cacciatore et al (Reference Cacciatore, Duval and Fiori2012) stressed that reducing job protection lowers firmsʼ firing costs in the short run. Consequently, low-productive job matches become less profitable, which leads to the firing of low-productive employees. Other notable works on this topic include Bassanini and Duval (Reference Bassanini and Duval2007), Guillermo and Montoya (Reference Guillermo, Montoya, Heckman and Pagés2004), and Cheng et al (Reference Cheng, Smyth and Guo2015).

Literature on the impacts of Vietnamese labour legislation is scant but also provides valuable insights. The closest to our study is Nguyen et al (Reference Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen and Tran2021a). Our paper also uses VLFS data to measure the impact of the labour code on labour market outcomes, like Nguyen et al (Reference Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen and Tran2021a). However, the two papers investigated different issues. While Nguyen et al focused on analysing the impact of the code on workersʼ welfare with different types of labour contracts (short-term contracts, medium-term contracts, and indefinite-term contracts), we disaggregated the effect of the code by location (urban and rural areas) and migration status (short-term migration, long-term migration, and non-migration). Regarding empirical strategy, our study outperformed theirs because we conducted some rigorous tests, including graphical diagnostics, parallel trend test, and Granger-type causality test for non-anticipatory treatment effects to verify the primary assumption of the strategy: the parallel trend assumption. Some other studies have also investigated the labour code from the perspective of other social science fields. For example, Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2018) tried to capture the relevance and importance of the Labour Code from the perspective of workers, their common language and explanations of their workplace experiences. The paper can thus reveal how the Code penetrates directly and indirectly into workersʼ assessments, complaints, and expectations. Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2019) briefly discussed the most crucial provisions of the Code, its development and importance in the countryʼs labour relations, provided an example of strike settlement and prevention, and discussed legal support activities and other issues. Buckley (Reference Buckley2023) argued that there are two streams of literature about the increase in formalisation of labour and the increase in informalisation of labour in Vietnam, and both are true. In addition, formal labour has been simultaneously expanded and informalised. Literature exploring other labour regulations also attracted our attention. Thus, Kim (Reference Kim2013) examined how private labour standards regulations in apparel and footwear factories can generate conflicts between factory managers and social auditors or workers. Schmillen and Packard (Reference Schmillen and Packard2016) argued that worker protection policies that admit creative destruction and encourage regular employment should be in place to promote a transition in the national economic structure. Recently, Nguyen et al (Reference Nguyen, Tran and Nguyen2021b) and Tran et al (Reference Tran, Nguyen, Nguyen and Nguyen2023) detected an absenteeism impact of social insurance on workers and their spouses. However, none of them profoundly gauged the influence of the Labour Code on labour market outcomes by location or migration status. Our research intends to fill the gap in the labour literature.

Identification and data

Identification method

In this study, we evaluate whether a labour code reform (LCR) has affected three types of outcomes: labour supply, income, and social protection using the DID technique. We need data from treatment and control groups prior and after the reform to use the technique. DID estimations compare changes in outcomes of the two groups pre- and post-reform. In this research, the treatment group includes workers with written labour contracts, and the control group includes those without written contracts. The DID equation for this study is the follows:

where O it presents outcomes (i.e., work hours, overtime status, income, benefit, and social and health insurance statuses) of worker i at time t, LCR denotes the reform dummy, Treat denotes the treatment group dummy, LCR*Treat is the reform effect, X stands for the vector of exogenous variables (including personal characteristics, work characteristics, time, and regional FEs), and ϵ is the error terms. δ denotes the coefficient of interest. The outcomes are quantified for different worker groups based on location and migration status.

For short-term regressions, we can also use a FE model for panel data as follows (Khandker et al Reference Khandker, Koolwal and Samad2010; Nguyen et al Reference Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen and Tran2021a):

where λ t denotes time-variant factors, τ i denotes time-invariant factors that may correlate with the treatment variable and error term, Ω it stands for new treatment variable, and δ denotes the coefficient of interest. Differencing terms in both sides of the equation (2) with their average values, the result is as follows:

where

![]() $\bar Z$

represents the average value of Z (i.e., O

it, λ

t

, Ω

it

, X

it

, and ϵ

it

). In brief, we get

$\bar Z$

represents the average value of Z (i.e., O

it, λ

t

, Ω

it

, X

it

, and ϵ

it

). In brief, we get

The source of endogeneity is eliminated from the differencing. This model provides us with the unbiased impact of the reform. The coefficients of OLS and FE estimations are equivalent for two time periods. Therefore, we can use the findings of the FE model to refine those of the ordinary least squares (OLS) one. However, for more than two time periods, the coefficients may be different.

Data description

This study uses data from the VLFS. This survey offers data on labour and employment of households across the country conducted by the Vietnam General Statistics Office since 2007. The purpose of the survey is to gather monthly and yearly information on the quantity and quality of the labour force in the labour market. VLFS collects information mainly on key labour market-related activities for people aged 15 years and more. The main users of these surveys are public managers, policymakers, business owners, and research institutions. The survey’s data represent the entire country, urban and rural areas, and six regions. As the 2012 Labour Code took effect in May 2013, our research uses data from the wave 2013 of VLFS to assess the impact of the law introduction using the DID technique. This wave has around 747,800 observations. Since VLFS allows us to extract short panel data with two periods and two groups from this wave, we can quantify the impact of the introduction using the FE model.

VLFS divides the observations of each wave into two groups: urban and rural. An urban (rural) migrant is a person who moves to the current ward (town or commune) from another place. The survey also lets us know how long a person has resided in the current ward/town or commune. We can, therefore, classify workers into three groups based on their migration status: short-term migrants (i.e., individuals migrated to the current place for 1 year or less), long-term migrants (i.e., individuals migrated to the current place for more than 1 year), and non-migrant workers (or local workers). The sample only includes people in their statutory working age (i.e., between 15 and 55 years old for women and 15 to 60 years old for men) residing in Vietnam during the survey period. A worker’s age is computed by the difference between the survey year and their birth year. In addition, those included in the sample must be employed. Since we use labour contract status to classify workers into the treatment or control groups, the sample did not include observations without labour contract information.

Results and discussions

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the average work hours in urban and rural areas for three different worker groups: short-term migrants, long-term migrants, and non-migrant workers from 2012 to 2014. As shown in the figure, urban workers worked significantly more hours than rural workers for all three groups. Short-term migrants worked harder than the other two worker groups in both urban and rural areas. Rural long-term migrants had more work hours than rural non-migrants, while the opposite is found in urban areas.

Figure 1. Weekly work hours by migration status.

Figure 2 presents the average monthly income for the three worker groups during the same period. Workers in rural areas had notably lower monthly incomes than urban workers in all three groups. Interestingly, the long-term migrant group has the largest income, while the short-term migrant group has the smallest income in urban and rural areas. However, this wage gap gradually decreases over time. In 2012, the wage difference between the two groups was VND 1.1 million and VND 0.9 million for urban and rural areas, respectively. Two years later, the disparities were only VND 0.4 million for urban and rural areas.

Figure 2. Monthly Income by migration status (million VND).

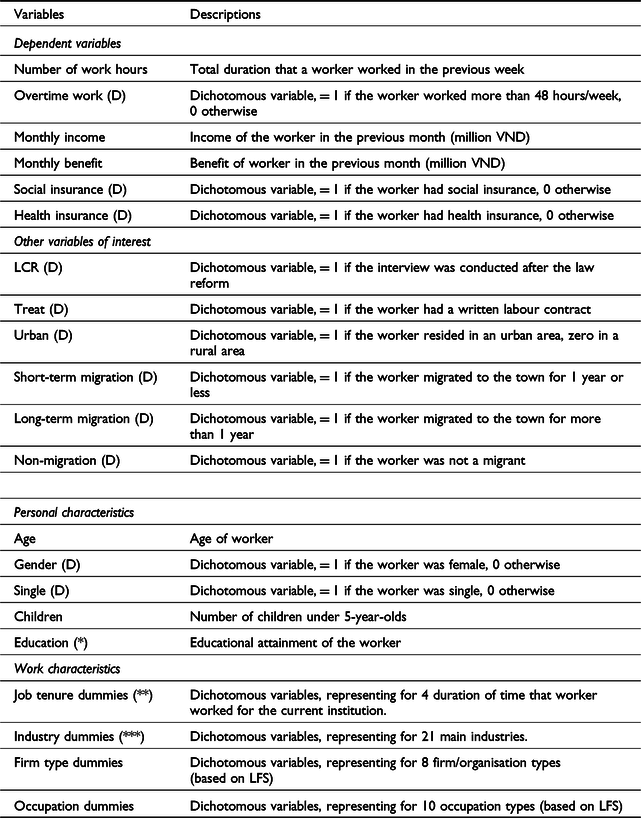

Table 1 describes the variables used in this research. We consider six outcomes: number of work hours, a dummy for overtime work, monthly income, monthly benefit, and two dummies for social insurance and health insurance participation. Forty-eight hours is the statutory standard number of work hours per week. Therefore, if someone works more than this amount of time, then s/he has overtime work. Personal characteristics include worker’s age, dummy for gender, dummy for married status, education attainment level, and number of children under five. We use the variable number of children under 5 years instead of the number of children under 18 years because very young children need more care than older children, which influences the work duration and the income of their parents. Work characteristics include dummies for job tenure, dummies for industries, dummies for occupations, and dummies for firm types.

Table 1. Variables used in estimations

(D): Dichotomous variable. (*) Seven educational levels based on LFS: (i) never attended school; (ii) not finished primary school; (iii) primary school completion; (iv) lower secondary school or vocational school; (v) Upper secondary school, mid-term vocational school, or professional school, (vi) vocational college or professional college; (vii) college or higher (Nguyen et al, Reference Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen and Tran2021a). (**) Four job tenure levels: (i) <1 year; (ii) 1–5 years; (iii) 5–10 years; (iv) ≥10 years. (***) 21 primary industries (i.e., economic sectors) based on VLFS.

We begin our analysis by measuring the effects of law reform on labour supply. We use the 2013 wave of VLFS because the new labour code took effect in May of that year. Firstly, the main sample is treated as a repeated cross-sectional data sample. We use the ‘didregress’ command of STATA 17 for estimation. Standard errors are clustered at enumeration area (‘dia ban’ in Vietnamese) levels. The most critical assumption of the DID approach is the assumption of parallel trends, which requires that, in the absence of legislation reform, the trends of the treatment group and control group should be parallel. This version of STATA also provides us two ways to test parallel trends assumptions (by plotting the means of the outcome over time for both groups and by performing a test to see if the trajectories are parallel before the law reform, using the commands ‘estat trendplots’ and ‘estat ptrends’, respectively). In addition, the User Manual of this version suggests that we may consider ‘nonparallel as an indication of an anticipatory treatment effect’. The fact that the trajectories of the two groups were not parallel before the law was implemented might reveal a treatment effect even before the actual commencement of the new law. Therefore, we can use a Granger-type causality model to test non-anticipatory treatment effects as another way to test parallel trends (i.e., using the command ‘estat granger’). The Appendix presented graphical diagnostics for estimations that satisfied both the assumptions of parallel trends and non-anticipatory treatment effects. For estimations that give non-significant results, no testing is needed.

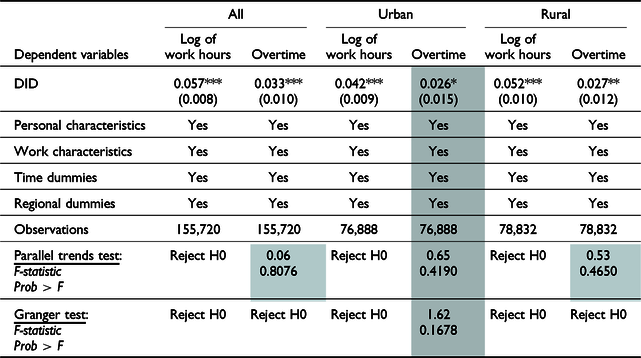

Estimations in Table 2 were based on equation (1). DID implied the coefficient of interest δ. All regressions control for the personal and work characteristics, time, and regional dummies. We use the survey weights in the estimations. The findings showed the reformʼs positive impact on work hours and overtime among contracted workers in rural and urban areas. However, only the overtime effect on urban workers passed both tests on parallel trends and Granger causality. A graphical diagnostic for the parallel trends assumption was presented in the Appendix. The pre-reform trajectories in the estimation appeared to be the same. The parallel trends test was satisfied for rural workers, but the Granger test was not.

Table 2. Effects of reform on labour supply by location

All columns control for personal and work characteristics, regional and time dummies. Standard errors in parenthesis are clustered at enumeration area levels. *, **, ***: significant at P = 10%, 5%, 1%, respectively. Estimations that pass both the parallel trends test and the Granger test have a grey background.

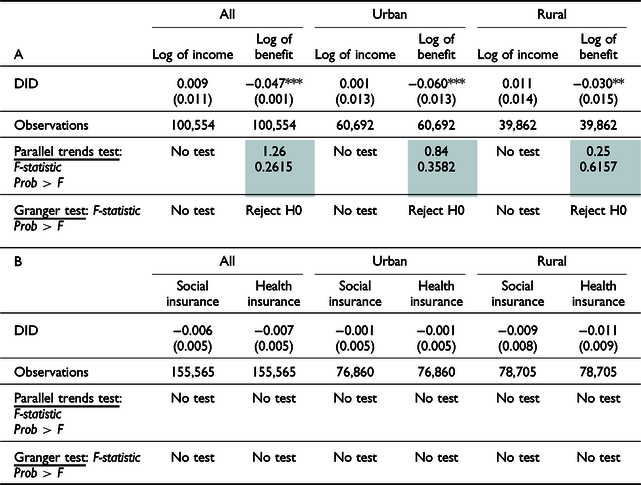

Table 3 is conducted similarly to Table 2, but the dependent variables are earnings- and social protection-related variables. As reported in Panel A of the table, both beneficial effects of the reform on rural and urban contracted workers satisfied the assumption of parallel trends but not the assumption of non-anticipatory effects. For results that are not significant, no testing is needed. Concerning Panel B, both urban and rural contracted workers did not significantly respond to the reform regarding social insurance and health insurance participation.

Table 3. Effects of reform on earnings and social protection by location

All columns control for personal and work characteristics, regional and time dummies. Standard errors in parenthesis are clustered at enumeration area levels. *, **, ***: significant at P = 10%, 5%, 1%, respectively. Estimations that pass both the parallel trends test and the Granger test have a grey background.

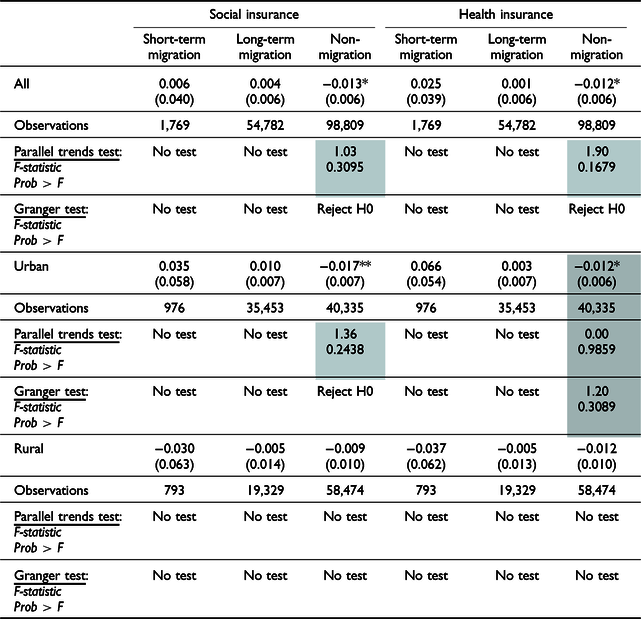

Table 4 presents estimations for different groups of migration status regarding labour supply and earnings. All regressions were controlled similarly to those of Table 2. For overtime work participation, only estimations on long-term urban migrants and short-term rural migrants passed tests on parallel trends and non-anticipatory pre-reform effects. However, looking at the diagnostic graph of short-term rural migrants in the Appendix, the outcome trajectories in the two groups before the reform are notably different. The fact that the number of observations of the estimation is relatively small may lead to the disparity of the two trajectories. Thus, the parallel trends assumption may not hold for the short-term rural migrants. Furthermore, only the income effects of long-term contracted migrants satisfied both assumptions on parallel trends and non-anticipatory effects. Table 5 indicated that health insurance participation decreased significantly for non-migrant contracted workers in urban areas. This estimation also passed both tests for the two mentioned assumptions.

Table 4. Effects of reform by migration status and location: labour supply and earnings

All columns control for personal and work characteristics, regional and time dummies. Standard errors in parenthesis are clustered at enumeration area levels. *, **, ***: significant at P = 10%, 5%, 1%, respectively. Estimations that pass both the parallel trends test and the Granger test have a grey background.

Table 5. Effects of reform by migration status and location: social protection

All columns control for personal and work characteristics, regional and time dummies. Standard errors in parenthesis are clustered at enumeration area levels. *, **, ***: significant at P = 10%, 5%, 1%, respectively. Estimations that pass both the parallel trends test and the Granger test have a grey background.

2-by-2 DID model

For each VLFS wave, each household was interviewed twice. Hence, we can extract a short panel with two periods and two groups (2-by-2) and use DID for estimation. (Individual household identifiers are not maintained yearly, so we cannot extract a data panel with three or more periods.) STATA 17 allows us to fit a 2-by-2 DID for panel data using the ‘xtdidregress’ command. However, we cannot test the assumption of parallel trends because there is only one period before the reform.

In Table 6, we replicated the estimations in Tables 2–5 but for panel data. All the estimations were based on Equation (4). As there are too few observations for short-term migrants, we do not report results for this group of workers.

Table 6. 2-by-2 DID estimations (panel data)

All columns control for personal and work characteristics, regional and time dummies. Standard errors in parenthesis are clustered at enumeration area levels. *, **, ***: significant at P = 10%, 5%, 1%, respectively.

As shown in Panel A, contracted rural workers positively responded to the reform regarding log of work hours. Also, the effects in terms of log of benefit were negatively significant for both urban and rural contracted workers. However, only urban workers responded significantly regarding income, social insurance, and health insurance participation. Panel B of the table presents the estimated findings based on migration status. The effects on long-term contracted migrants were detectable regarding work hours and overtime in rural areas. Contracted non-migrants in urban areas significantly responded to the reform regarding work hours. Concerning earnings and social protection, non-migrant and long-term migrant contracted workers in urban areas were adversely affected by the legislation in terms of income, benefit, and social and health insurance participation, except for the participation in health insurance of long-term migrant contracted workers.

Discussions

Some previous studies have also investigated the relationship between labour regulations and employment. Cheng et al (Reference Cheng, Smyth and Guo2015) indicated that China’s 2008 Labour Contract Law did not cause a greater labour supply impact on urban employees than migrant employees. They explained this result as the employers’ reaction to a surge in the hiring cost for migrant employees through a minimum wage increase by lowering employment. Gallagher et al (Reference Gallagher, Giles, Park and Wang2015) found that the labour contract law enhanced the protection for rural migrant employees. Also, a substantial employment expansion and low unemployment were detected in the country’s urban labour market. McKenzie (Reference McKenzie2017) reviewed recent documents on active labour market policies and did not find a clear effect on employment in many of them. He suggested that there were fewer failures in the urban labour market than policymakers expected. The findings of previous works did not directly explain our results, but they are still helpful. For example, an implication from McKenzie’s work for our case is that rural labour markets do not respond to legal changes. As our investigations mainly focused on the effect of the reform in 1 year, literature on the short-term impacts of EPL is of interest. Deakin et al (Reference Deakin, Malmberg and Sarkar2014) did not find a clear short-term effect on unemployment. However, a positive association between a labour law change and a labour share was detected in the short run. Bassanini and Duval (Reference Bassanini and Duval2007) suggested that a stricter EPL may lower the short-term unemployment impacts of shocks (e.g. productivity or labour demand shocks). The time required for unemployment to adjust back to the initial level is also longer. Guillermo and Montoya (Reference Guillermo, Montoya, Heckman and Pagés2004) insisted that firms significantly reduce their labour demand to respond to severance payment regulations in the short and long run. The decline in labour demand is partly responsible for reductions in earnings and employment.

Concerning earnings, the association between labour policies and the urban–rural wage gap was mentioned previously, although little directly related to our study. Bosch and Manacorda (Reference Bosch and Manacorda2010) showed that a sharp reduction in the minimum wage increased inequality in Mexico. Also investigating minimum wage, Andalon and Pages (Reference Andalon and Pages2008) found that enforcing Kenya’s minimum wages was better in the non-farming urban sector. Besley and Burgess (Reference Besley and Burgess2004) indicated that the amendments of the Industrial Disputes Act 1947 positively linked with a growth in Indian urban poverty. Card et al (Reference Card, Ibarraran, Regalia, Rosas and Soares2011) evaluated a job training programme in the Dominican Republic. They found a weak relationship between the training programme and wages and health insurance coverage among young workers in urban areas. Concerning labour contract law, migrant workers in China were less affected by the law introduction than local workers in terms of receipt of social benefits and wages. Moreover, having labour contracts positively influenced their wages and social insurance participation (Cheng et al Reference Cheng, Smyth and Guo2015). Our work thus contributes to the existing literature on urban–rural disparities in another Asian country.

Regarding migration, internal migrants are often not the subject of EPL studies in Europe, but immigrants are. Arguments for the second group may be applied to the first group. Some past studies compared the impact of the legislation on outcomes between natives and immigrants. Sá (Reference Sá2011) indicated that a stricter EPL lowered employment and diminished hiring and firing rates for natives but had a negligible impact on immigrants. Causa and Jean (Reference Causa and Jean2007) found that a stronger disparity in stringency between permanent and temporary contracts reduced the employment disparity but raised the wage disparity between two groups of workers. Kahn (Reference Kahn2007) suggested that a stricter EPL decreased employment among young and immigrant workers compared to other groups. Some analyses explored the influences of a Chinese labour contract law and revealed that the law negatively affected wages and hours but positively affected social insurance coverage among migrant workers (Li and Freeman Reference Li and Freeman2015; Meng Reference Meng2017). Cheng et al (Reference Cheng, Smyth and Guo2015) is a scant work comparing the short-term effects of a labour contract law between local and migrant workers. They found that the law affected the first group stronger than the second group regarding receiving social benefits and wages, but not work hours. Similar to Cheng et al, we found that the impact of the Labour Code was weaker on local workers than on long-term migrants in rural areas in terms of labour supply. The research results on Chinese contract law are highly useful to us, thanks to the similarity in political institutions and labour markets between the two countries.

Conclusion

This study has investigated how Vietnam’s 2012 Labour Code affected workers’ outcomes, in which workers’ location and migration status were used as classifications. Investigating a cross-sectional data sample, we found a positive relationship between the law reform and overtime work participation of urban contracted workers. This finding can be explained by the significant response of long-term migrant workers in urban areas to the reform. In addition, there is a link between the reform and the log of income of long-term migrant contracted workers. Concerning social participation, the paper highlights that health insurance participation is considerably reduced among non-migrant contract workers in urban areas. These estimations passed the assumption tests of parallel trends and non-anticipatory effects. We also performed estimations using a short 2-by-2 panel sample and found some association between the reform and workers’ outcomes regarding labour supply, earnings, and social protection. However, we could not test the assumption of parallel trends of these estimations because there was only one period before the reform. Besides, the paper indicated that short-term migrant workers worked harder than their long-term migrant and their local counterparts in urban and rural areas. Rural workers earned significantly less than urban workers, regardless of their migration status.

Our study complements Nguyen et al (Reference Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen and Tran2021a) because we have shown a different perspective on the impact of the labour code on workerʼs welfare. Besides, our empirical strategy outperforms theirs since we used some rigorous tests to verify the main assumption of the DID method – the parallel trend assumption. Some other previous literature has debated the code and worker outcomes as well. Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2019), for example, introduced and discussed the provisions of the law related to wages, benefits, working hours, and overtime. Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2018) and Buckley (Reference Buckley2023) also discussed these outcomes but focused on different aspects. Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2018) presented complaints in letters from migrant workers about inadequate living wages and from other workers about issues related to overtime, such as reduced rest time due to overtime work, forced overtime, and overtime without extra pay. Buckley (Reference Buckley2023) stated the reasons why workersʼ wages are not enough to live and why they have to work overtime, similar to Nguyen (Reference Nguyen2018). According to Buckley, overtime is quite common in the informal sector. He likewise discussed wages in the formal and informal sectors. He emphasised that one of the most essential benefits of formal employment is social insurance (including pension, unemployment, and health insurance). The findings of our study on the impact of the code on wages (especially wages of migrant workers), working hours, overtime, and social insurance will contribute significantly to the discussions of Nguyen (2018, Reference Nguyen2019) and Buckley (Reference Buckley2023). Our research is also related to studies on the influence of labour legislation on Chinese migrant workers (Cheng et al Reference Cheng, Smyth and Guo2015; Li and Freeman Reference Li and Freeman2015; Gallagher et al Reference Gallagher, Giles, Park and Wang2015; Meng Reference Meng2017). However, we use the laws and data in Vietnam. Other studies on the effect of labour legislation reform on the labour market in other countries can benefit from our empirical methods and results.

Our research’s findings provide evidence of workersʼ reactions to increased protection of their rights through reform of the labour code. These findings are consistent with modern theory. Understanding the influence of increased rights protection on workersʼ welfare is crucial for improving labour relations. Measuring the influence of the reform by location and migration status is vital because Vietnamʼs transition from a command economy to a market economy has exacerbated the urban–rural gap and increased internal migration. Closing this gap is a national priority. In addition, the rate of urbanisation is often seen as a measure of social progress. Internal migration is one of the most critical determinants of the urban–rural disparity and the urbanisation rate (Giang and Nguyen Reference Giang and Nguyen2023). Our research contributes to the literature on the connection between labour legislation reform and workersʼ welfare, especially the analysis of disadvantaged workers (migrant workers and rural workers) in Vietnam. This topic has yet to be well considered in previous studies.

Our findings also provide crucial implications for policymakers because they confirm the importance of urban–rural disparity and migration status in evaluating the impacts of labour regulations. The study further demonstrates that vulnerable worker groups are disadvantaged regarding wages and hours worked. Due to the urban–rural gap and the fragmentation of the labour market, treating workers equally in urban and rural areas will take a lot of work. Labour policy needs to pay attention to that fact. The national labour policies cannot make a distinction between urban and rural workers. However, particular local policies may have incentives to support rural and migrant workers. The study also shows that the law has little impact on rural areas. Rural workers, especially migrants, may be less informed about new labour policies than urban workers. Thus, there is a need for awareness-raising programmes about legal changes and rights for all rural workers. Another problem is law enforcement. Many employers intentionally use the wrong type of labour contract to avoid paying social insurance premiums to reduce labour costs. In addition, there are violations by business owners regarding the dismissal process, the salary system, labour standards, overtime, and compensation. Therefore, it is necessary to enhance the effectiveness of trade unions in protecting workersʼ rights and strengthening the supervision of employers (Ngok Reference Ngok2008; Nguyen et al Reference Nguyen, Nguyen, Nguyen and Tran2021a).

Because of the data inadequacy, we could not utilise the DID model for a panel data sample of three or more periods. Moreover, our findings may need to be validated for other countries. The LCR may not affect the welfare of any group of employees elsewhere. Therefore, other research should be careful when referring them to other economies or groups of employees. Future studies may focus on the reform’s impact on other vulnerable groups, such as elderly workers or ethnic minorities.

Funding statement

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Appendix

Figure A1. Graphical diagnostics for parallel trends.

Dung Kieu Nguyen is a Lecturer and Researcher at FPT School of Business and Technology, FPT University, Hanoi, Vietnam. She received her Ph.D. degree in Economics from the State University of New York, Albany, USA. Her research interests include Labor Economics, Demograpgy, Industrial Organization, Science and Technology, Development Economics, and Public Policy.

Diep Ngoc Nguyen is working at the Institute of Theoretical and Applied Research, Duy Tan University, Hanoi, Vietnam, and School of Business and Economics, Duy Tan University, Da Nang, Vietnam. Her research interests include Labor Economics, Education, Public Health, and Youth and Adolescent performance.

Son The Dao is a Senior lecturer and Researcher of the Center of Science and Technology Research and Development at Thuongmai University, Hanoi, Vietnam. His research interests include Education, Health Policy, Health Economics, and Public Policy.

Trang Phan is an Associate Professor of the Department of Business Administration, Augustana College, IL, USA. Her research interests include Empirical Asset Pricing, Mutual Funds, Performance Measurements, and Labour Economics.