In 1782, Singhvi Chainmal, an officer of mercantile caste writing on behalf of the Rathor king of Marwar, sent an order to the governor (hākim) of Pali district reprimanding him for failing to sufficiently punish certain criminals. The crime in question was the use of owl’s meat. The order said, “the mother of Patar Situdi told a visiting “mātmā” from Bikaner to perform a magical ritual to subjugate a person (ādmī rā vaskaraṇ rā ṭānar ṭunar Footnote 1 kar dai).”Footnote 2 A “patar” was a skilled female performer, of slave origin, in a royal or noble domestic household or in a courtesan commercial establishment.Footnote 3 Given the lack of reference to a nobleman in whose household she belonged and her continued connection with her mother, it is likely that the pātar mentioned here was a courtesan. “Mātmā,” a local vernacularization of “mahātmā” or “great soul,” designated Jain yatis (loosely, monks).Footnote 4 Even as yatis took initiation into the monastic community, they may not have taken the Five Great Vows (essential for orthoprax monks) in full-fledged form.Footnote 5 They enjoyed a degree of laxity in adhering to vows such as itinerancy (to prevent worldly attachments) and riding vehicles (to avoid harm to living beings).Footnote 6 While some yatis were householders, others were celibate. Still, they earned deference from lay Jains and others due to their command of ritual as well as worldly knowledge. Yatis worked as teachers, scholars, genealogists, healers, and painters. And, until well into the nineteenth century at least, they were known as practitioners of “jantar-mantar”Footnote 7 or the occult sciences which included the fields of astrology and medicine.Footnote 8

This unnamed monk—whose precise vows and practices are impossible to guess given the variation among yatis—was visiting from outside the Rathor kingdom’s borders and probably was reputed for his knowledge of the occult arts. This is why Patar Situdi’s mother sought him out for the task of helping her, through occult ritual, to bring an unnamed person under her control. The monk agreed and told the woman to bring him an ingredient necessary to perform the ritual: owl’s meat (ghūghū rā mās). The courtesan’s mother procured the owl’s meat but, unfortunately for them, the matter became widely known and attracted the attention of Rathor state officers. Patar Situdi’s mother and the Jain monk were arrested.

While the monk and his client were under arrest at the local magistracy (cauntrā), news of these developments reached the capital, Jodhpur, from where an administrator, Singhvi Chainmal, ordered that the two should be properly punished (purkas gunaigārī karaṇ mai āvsī). He wrote to the governor of Pali, “They have committed such an unambiguous crime (purkas taksīr). Why do we have to send orders for you to punish them? How could you think of releasing them without punishing them? Now the order is: tie both of them to a metal peg in the bazaar for ten–twelve nights and days. Have them beaten for eight pahars [that is, 24 hours] on each of those days with bhaṅgīs’ shoes.Footnote 9 Send a written update on this issue and do as this command states. If there is any negligence (gāphlī) or delay in this matter, you will fall out of favor.”Footnote 10 The order concludes with an instruction to the governor of Pali about the carrier (kāsīd) bearing the command, noting that he will leave Jodhpur two pahars (six hours) after midnight (adhrat) and that if he reaches Pali the following night, he should be given a reward. Singhvi Chainmal’s command then betrays a certain urgency.Footnote 11

Bringing together a Jain monk, a courtesan’s mother, owl’s flesh, the market town of Pali, the kingdom of Bikaner, and the royal court in Jodhpur, this one record from the eighteenth-century archive of the western-Indian kingdom of Marwar knots together many different threads that I will trace in this article. In unraveling this knot, I argue that the occult was not only the tool of imperial politics that we now know it to be from scholarship on the transregional Persianate cosmopolis. Rather, the occult was part of the arsenal of political technologies available to and deployed by non-courtly as well as non-elite actors in early modern South Asia. Every day, localized interactions outside of the patronage of royalty and aristocrats and beyond the compositions of learned initiates formed a site—the popular—for the circulation and mixing between bodies of knowledge, particularly Islamic occult science and tantra, which are usually studied in distinct historiographies. I suggest that elite investments in the occult were rivalled by those of non-courtly actors. The occult, then, was a site of political contestation, a resource whose use kings tried to restrict through their control of state power. This history overlaps with widespread anxieties about the popular occult as witnessed in the witch trials of early modern Europe and in the outlawing there of magic and sorcery.Footnote 12 If one of the characteristics of early modernity across the globe was the emergence of ideologies of universal empire, as Sanjay Subrahmanyam has argued, then I suggest that this quest for “universal” imperial power heightened courtly sensitivities vis-à-vis access to technologies of power. One such technology of power was occult expertise. Early modern kings and courts were invested in regulating access to it as well as to the substances and materials required for its successful deployment, materials such as owl’s flesh.Footnote 13

The article also makes a case for the centrality of “marginal,” wild non-human animals, as exemplified by the owl, to this domain of lived occult practice. Whether in the Islamicate or tantric mode, occult practice in early modern South Asia was interlinked with a perception of non-humans not as others but as co-inhabitants of a shared world consisting of visible and invisible truths and circulating forces of good and evil. This imagination, however, encoded certain wild animals—as exemplified by the owl—in ways quite distinct from the kinship and prestige that domesticated animals enjoyed. The owl was a liminal being, associated with the interstices between life and death, day and night, and even human and non-human. This position on the periphery generated for the owl a different order of associations and a different sort of technological power than that connected with animals employed in war and economic production. The owl worked in death and in representation as a bridge to the unseen.

Belief in occult power and of the use of animal flesh in ritual stood at odds with the enthusiasm for Krishna-centered Vaishnav devotion, known for its rejection of animal sacrifice, embrace of non-harm and vegetarianism, and fierce polemical attacks on tantra, a system of theory and practice geared towards becoming god-like or god-minded, with some schools positing such attainment as a means to salvation.Footnote 14 Krishnaite Vaishnavism on the other hand had become a marker of cosmopolitan Rajput kingship in north India in the course of the early modern period.Footnote 15 Episodes such as the one above then represented fissures in eighteenth-century polities as they stood on the cusp of the modern age, fissures that represented differences of opinion on the permissibility of the use of occult knowledges, on who could use the occult knowledges in question, and on the ends to which these knowledges were deployed. The occult, then, was both a means and a site of political contestation.

Early Modernity, the Occult, and Animal Pasts

The past decade has seen an efflorescence of work on Islamicate occult sciences across the early modern Persianate world, spanning the Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Empires, as well as smaller polities such as the Deccan Sultanates in peninsular India. Apart from revealing yet another axis of the interconnections of the Persianate world, this work has also made clear how significant the occult sciences were to the effort to know, interpret, and live in the world. It tells us how the occult sciencesFootnote 16 promised access to that which could not be known through empirical observation alone.Footnote 17 We now know the significance of the occult sciences to the practice and projection of early modern kingship and empire in the Persianate world, including South Asia.Footnote 18

Yet, the study of the occult sciences in the premodern Persianate world remains largely confined to the study of courtly and elite scholarly engagements with experts. In concluding his research on fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Ottoman astrology, for instance, Ahmet Tunç Şen notes the still unsatisfied historiographical need to study the less technical and more popular production and circulation of astrological knowledge in the early modern Ottoman world.Footnote 19 Matthew Melvin-Koushki points to evidence for the unprecedented de-esotericization of the occult through the rise of texts that departed from the earlier emphasis on secrecy, which in turn caused the popularization of the occult sciences.Footnote 20 But precisely what this popular domain of occult practice looked like across different regions in early modern Asia has only begun to be explored, particularly for South Asia. For instance, Shamsur Rahman Faruqi and Pasha M. Khan have highlighted the significance of sorcery, magic, and wonder in early modern Persian stories of the qissah genre.Footnote 21 Khan unearths the ways in which qissahs, enjoyed by rich and poor, testify to an early modern conception of the divine creation and re-creation of sorcerers, conjured worlds, and marvelous creatures.Footnote 22 It is this domain of popular—non-courtly—occult practice that I will further explore in this article.

Another stream of occult knowledge, one that intersected at many historical junctures with Islamicate occult sciences, was that of tantra. Footnote 23 Tantra is hard to define and varied tremendously over place and time. It is a range of practices and beliefs that can be found in Brahmanism, Buddhism, and Jainism. This set of traditions rests upon a particular body of scriptures composed between the fifth and ninth centuries CE, even as they drew upon multi-nodal origins and influences that kept reshaping tantric “tradition.”Footnote 24 These texts, known collectively as the Tantras (with “tantra” literally meaning “loom” and suggesting an interwoven network of ideasFootnote 25), were claimed to be teachings spoken by the gods that stood at a higher plane than the Vedas—whose primacy was central to Brahmanism—in terms of their ability to lead the initiate towards liberation (mukti) from the cycle of birth and rebirth.Footnote 26 They also offered a path towards the acquisition of extraordinary or occult powers.Footnote 27 The history of tantra and of a South Asian demonology that exceeds tantra is itself a trans-Asian history of connection and comparison, tying together South Asia, Tibet, China, Japan, and Southeast Asia through a shared embrace—with varying intensities at different periods of time—of this fluid tradition during the medieval and early modern eras.Footnote 28

Tantra had commanded immense influence in the form of text-centered and court-supported orders on South Asian ritual life in the early medieval period. Even as this complex began to unravel after the twelfth century, scholars have shown that tantric practice persisted in diffuse ways.Footnote 29 Ellen Gough shows that tantra remained key to the Jain path towards liberation and was not inconsistent with the ascetic values of Jainism.Footnote 30 Patton Burchett suggests that, apart from being incorporated into bhakti religiosity, tantra qua tantra, that is, as an embodied practice whose perfection promised the command of divine power in the hands of the practitioner himself, continued to exist in a more popular and less text-centered form in localized settings.Footnote 31 In early modern South Asia, tantra also continued to thrive among lineages of Buddhists in the Himalayas and on the island of Lanka.

As with Islamicate occult sciences, the majority of studies of premodern tantra are based on texts composed by literate initiates, whether theoretical, philosophical, instructional, devotional, or hagiographical.Footnote 32 Many unanswered questions remain about the place of tantra in early modern South Asian political and social history, as also about the lived practice of tantra in a milieu populated by spiritual adepts from many different orders—Naths, Sufis, Dasnamis, Sikhs, Jains—that overlapped on the ground.Footnote 33 In traversing across these bodies of systematized knowledge and practice, I use “occult” as an umbrella term that offers a capacious enough conceptual space to denote and think through the early modern popular engagement with these circulating knowledges.

Tantra and the Islamicate occult sciences have in common the conceptualization of extra-sensory realms. This is an imagination in which the boundary between the human and the non-human is highly porous. Tantra, for instance, posits humans and non-humans as dwelling in that part of the cosmos that was closer to the sphere of operation of a host of lesser deities understood as capricious, in need of ritual propitiation, and given to entering the “container” of any animate or inanimate form’s physical body.Footnote 34 In the Islamicate occult sciences as well, the behavior and calls of animals and birds were considered interlinked with developments in the occult realm. In Europe, too, animals were associated with witchcraft, as “familiars” or companions to witches and as hybrid creatures that were part-demonic and part-animal.Footnote 35

If precolonial and early modern worlds of animals and humans were marked by much greater intimacy between humans and animals, as for instance Alan Mikhail as shown for Ottoman Egypt, then to write a history of people without attention to animals is indeed a kind of forgetting.Footnote 36 I will turn attention away from those laboring animals, particularly those considered prestigious such as horses and elephants, that have until now commanded historiographical attention for premodern South Asia.Footnote 37 I will focus instead on another kind of human-animal relationship, in which certain animals, here the owl, performed other kinds of labor: ritual and political. But the owl did this work as an idea: through its image or its flesh. I will thus argue that intimacies between humans and animals in the early modern world were born not only of physical proximity and shared spaces, as Mikhail shows, but also of distance and inaccessibility.

Portents, Curses, and Talismans

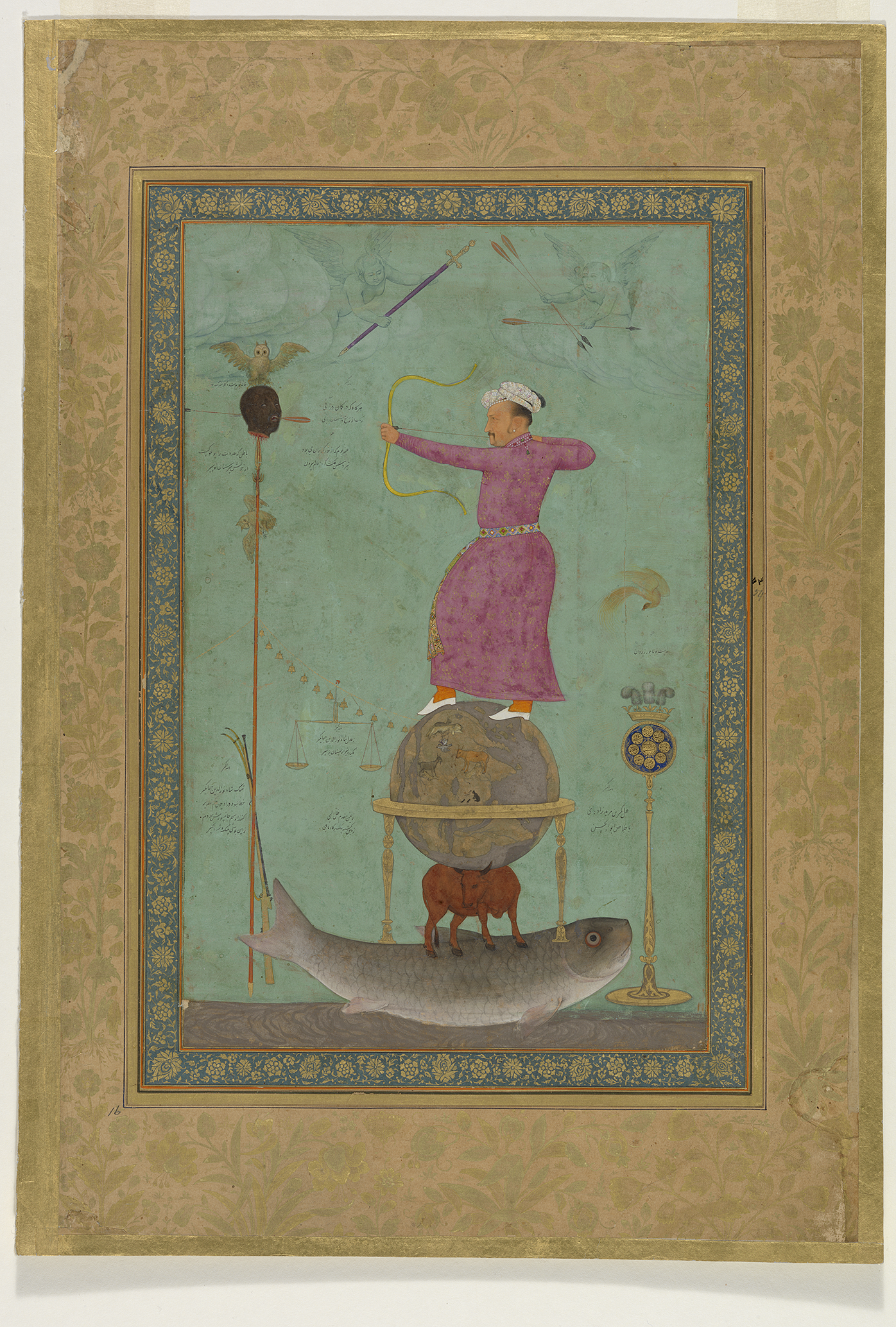

In the well-known painting that the Mughal Emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–1627) commissioned around 1616 that depicted him as the slayer of the Nizamshahi general Malik ‘Ambar (1548–1626), both the image and the inscription on it connect Malik ‘Ambar to the owl (see Image 1). Malik ‘Ambar was of slave origins, born in the Kambata region of Ethiopia, sold into slavery in Baghdad, and brought to the Deccan in 1575. His military and strategic prowess propelled him to the position not only of a leading general but also of the power behind the throne in the Sultanate of Ahmednagar, ruled by the Nizamshahi dynasty. Jahangir’s drive to expand his domain brought him into conflict with the Nizamshahis, whose kingdom in the Deccan was just south of Mughal territory. Despite Jahangir’s best efforts, the Mughals were unable to gain more than a temporary victory over the Nizamshahi forces led by Malik ‘Ambar. The Mughals never succeeded in defeating Malik ‘Ambar, which makes Jahangir’s painting depicting his triumph over Malik ‘Ambar all the more remarkable.

Image 1. “Jahangir Shoots Malik ‘Ambar,” by Abu’l Hasan, Folio from the Minto Album, ca. 1616, Chester Beatty Library, Dublin (accession number 07A.15).

The painting depicts Malik ‘Ambar’s severed head, shown impaled on a spear that also pierces the carcass of an owl. As Jahangir’s arrow pierces Malik ‘Ambar’s skull, another owl, this one living, alights on the head. Writing near the decapitated head of Malik ‘Ambar and the owl alighting on it refers to Malik ‘Ambar as “’anbar-i būm” or “‘Ambar’s owl,” stating: “’anbar-i būm ki az nūr gurīzān mībūd/tīr-i dushman fikanat kard zi ‘ālam birūn” (Your enemy-overthrowing arrow put the ‘Ambar’s owl, who was fleeing from the light, outside of the world).Footnote 38 Another inscription, this one near the feet of the owl perched on ‘Ambar’s head, states, “The face of the night-colored one has become the house of the owl ( khāna-ye būm shuda kala-e shabrang ghā… [inscription trails off].”Footnote 39 For Jahangir, reference to ‘Ambar’s dark skin (“night-colored/shabrang”) was significant to his portrayal not just as an enemy of the Mughals but also as one who stood with darkness, evil, and injustice.Footnote 40 This portrait visualized that association of Malik ‘Ambar with metaphorical darkness through the device of the owl, a creature of the night.

In his memoir and in connection with the campaign against Malik ‘Ambar, Jahangir mentions the inauspicious nature of the owl when he recounts an incident that occurred in Ajmer—on the frontier of the Jodhpur polity—in 1617, where the emperor was based at the time. An owl landed near him in the evening, just hours before Prince Khurram, the future Emperor Shahjahan, was to head out for an expedition against Malik ‘Ambar’s forces. Without a moment’s hesitation, Jahangir shot the creature, an “ill-omened bird,” killing it as if “by a decree from heaven.”Footnote 41 Clearly, Jahangir considered the episode significant enough to record for posterity. Azfar Moin draws a connection between the painting and this episode in the Jahangirnama, reading the gun that leans against the spear on which Malik ‘Ambar’s head is impaled as a gesture towards this event.Footnote 42 Yael Rice too sees a link between the image and the recorded episode, arguing that the memoir’s documentation of the actual appearance of the owl served to demonstrate the prophetic nature of Jahangir’s visions, in itself a sign of his exalted spiritual and temporal status.Footnote 43

In Islamic traditions, a talisman is a device that “conjuncts celestial influences with terrestrial objects in order to produce a strange ( gharīb) effect according to the will (niyya, himma) of the practitioner.”Footnote 44 Moin argues that the painting was talismanic, one of a series of talismanic paintings that Jahangir commissioned between 1615 and 1618.Footnote 45 To Mughal Emperors, painting was a “mighty magical operation (jādūkārī shigarf),” akin though inferior to the power of letters.Footnote 46 Building on these insights, I argue that the inscriptions on the painting were more than aides to decipherment. They also served as formulae channeling occult power against a formidable foe.Footnote 47 By commissioning the painting in the heat of his struggle with Malik ‘Ambar, Jahangir sought to deploy occult power through this painted image as well as the words inscribed upon it.

The arrival and slaying of the real-life owl at a key moment in the Mughal struggle against Malik ‘Ambar, then, was portentous. Jahangir had tamed the ill omen of the owl with ease but Malik ‘Ambar had not been quite as easy to subdue. With the aid of the talismanic painting linking the omen and the enemy, Jahangir sought to manifest ill effects, defeat, and death upon Malik ‘Ambar. As Moin has pointed out, the painting is divided visually into two halves. On the right half of the painting, Jahangir is astride upon a globe in which, evoking the Biblical and Quranic King-Prophet Solomon’s kingdom, predators and prey not only live together in peace but suckle tamely on each other’s teats, thereby establishing a milk-grounded kinship. The figure of Solomon appeared frequently in Mughal literature, art, and architecture to configure each Mughal Emperor as a second Solomon.Footnote 48

But King Solomon was not only renowned for his peace-bestowing justice. From the Early Middle Ages, Jewish and Muslim thinkers understood Solomon as not only possessing a close understanding of plants and animals but also being able to enter into dialog with birds and other creatures.Footnote 49 As a talisman for directing death and devastation towards Malik ‘Ambar, the evocation of Solomon in Jahangir increased the painting’s power, imparting to the emperor a mystical understanding of and command over birds like the owls in the painting. It channeled this second Solomon’s magical-medical powers toward eliminating a figure he considered to be a source of injustice and darkness.Footnote 50

The inclusion of the mythical humā bird in the painting heightens the contrast with the owl, for the nobility and blessed nature of the humā were frequently opposed in Persian poetry since the medieval period with the greed and ill-omened qualities of the owl.Footnote 51 The humā was associated with sovereignty, even its shadow bestowing upon a man kingship. Moin suggests that while the dead owl may be a metaphor for Malik ‘Ambar himself, the owl shown alighting on him may have been a means of directing bad luck towards him even in death.Footnote 52 In yet another contrast, Jahangir’s head is turbaned, bejeweled, and well-groomed. Instead of a turban, a symbol of manly honor, Malik ‘Ambar’s bare head is a perch for a bird, one that was a bearer of bad things.Footnote 53 At the time, honor was essential to political participation and social status, and, in Mughal conceptions of the body, it was most concentrated in the head. The decapitation of the head, then, brought not only death but also dishonor.Footnote 54 The wishful representation of the impaled head of Malik ‘Ambar directed dishonor and indignity toward him.

A careful copy of the painting, although one that falls short of the skill of ‘Abul Hasan, was made in the early nineteenth century and the inscriptions on it, while they depart from the wording of the original, retain the comparison of Malik ‘Ambar to an owl.Footnote 55 But the owl was more than just a bad omen, an agent of darkness, and a bearer of bad luck. We know from other encounters with owls in early modern sources that the owl’s body and therefore perhaps also its image, as in this talismanic painting, could be a potent ingredient for the activation of occult power. For these encounters, I turn now to the eighteenth-century administrative documents of the Rathor state in Marwar.

The Significance of Pali

The Rathors were a dynasty of Rajputs (hereditary warriors and landed elites) whose rule in Marwar dated back to the thirteenth century. Over the centuries, the contours of their kingdom had expanded and shrunk and the drive toward monarchy had faced stubborn challenges from the fraternal ethos of the clan-based polity. In the sixteenth century, Rathor king Mota Raja Udai Singh accepted Mughal suzerainty and the kingdom became incorporated into the Mughal Empire. Alliance and kinship with the Mughals and the immense wealth and new cultures of cosmopolitanism that the imperial formation brought strengthened the ruling Rathor lineage’s command over the regional polity. By the mid-eighteenth century, the Mughals had only a nominal command over Marwar, and it was the Marathas, an expanding power from the south, who loomed large over the sub-continent. Despite the political instability of the eighteenth century, Rathor Maharaja Vijai Singh managed to rule Marwar for more than forty years (1752–1793), introducing innovations in record keeping, military organization, coinage, and the practice of royal authority.Footnote 56

The town of Pali lay in the southeastern quadrant of the Rathor kingdom and had emerged as a trading hub in the medieval period. A trade route to and from the ports of Gujarat passed through Pali and a community of Brahmin traders, Palliwal Brahmins, emerged there. The founding myth of the Rathor dynasty in Marwar, preserved in court-commissioned chronicles in the seventeenth century, is centered on the town of Pali. It was here, early modern courtly narratives held, that the wandering prince Asthan (d. 1291) came to the rescue of a community of Brahmin traders. One such chronicle, the Mārvāḍ rā Parganāṁ rī Vigat [Account of the districts of Marwar], compiled around 1664 CE for the Rathor court, says that Asthan was a son of king Siho of Kannauj (in modern-day Uttar Pradesh), and upon reaching adulthood, set off to carve a place for himself in the world.Footnote 57 Asthan and his ten followers made camp near the town of Pali in Marwar. The town was home to Palliwal Brahmins, teachers and advisors to the kings of Udaipur (rāṇe rā gur), and to very wealthy men (“lākhesurī koḍīdhaj dhanvant lok rahai chai” or “rich men possessing lakhs and crores in currency live there”).Footnote 58 Just as Asthan and his retainers were settling in, a thundering band of hill-dwelling Mers on horseback descended upon them and took off with three horses. Asthan and his ten Rajput retainers had no trouble in catching up with the Mer bandits, killing forty of them while suffering no losses themselves. The people of Pali were awestruck, Nainsi tells us. They asked Asthan who he was and upon learning of his princely pedigree, they thanked their lucky stars. “Without lifting a finger, a hungry Rajput boy of a great house has come to us!” they said, and decided to ask him to stay.Footnote 59 They were looking to put an end to the theft and banditry that the chronicle claims plagued their town and its vicinity.

So it was that Asthan gained a foothold (pagṭhor) in Marwar, amassing land and enlarging his sāṭh, or body of military retainers. With time, according to Rathor narratives, Asthan expanded his territories in the Marwar region. Pali and its wealthy community of Brahmins, who likely made their fortunes in trade, and mountain-dwelling Mers were thus central to the Rathor founding myth as it was recited and recorded in the early modern period. Pali continued to be a parganā (district) headquarter for Rathor government, with the district’s governor (hākim) and his office (kacaiḍi) as well as the magistrate (koṭvāl) and his office (cauntrā) being located in the town.

Alongside, Pali continued to be a hub for trade and early nineteenth-century sources observe it to be a burgeoning commercial center.Footnote 60 English East India Company officer James Tod, who traveled through western India from 1818 to 1822, observed Pali to be preeminent among all the trading centers of the region, a market where sea- and land-based routes converged.Footnote 61 Since India’s trading relationship with the rest of the world had only grown more intense in the early modern period, Pali’s bustling markets, too, were a distinctly early modern phenomenon. Pali was the kind of place in which people converged from lands far afield from Marwar. It is, then, perhaps not a coincidence that most of the episodes involving the use of owl’s flesh in Rathor Marwar unfolded in Pali. As a market town, it was not just copper, dates, ivory, silks, sandalwood, coffee, chintzes, and shawls that one could find in Pali’s bazaars. More obscure items, like owl’s flesh, too, could be more easily and anonymously bought there.

Owl’s Flesh and Mind Control

Earlier I noted the urgency that crown authorities in Jodhpur expected from administrators on the ground in Pali in response to the courtesan Situdi’s mother commissioning a monk’s use of owl flesh. What was the rush? Why was crown officer Singhvi Chainmal so exercised about the courtesan and the Jain adept’s use of owl’s flesh? What was so grave about the crime that the Jodhpur-based administrator felt deserved a far more extreme and public punishment from the state than the few days’ imprisonment that district authorities had originally deemed fit for the two? Chainmal’s order points squarely to the nature of the ritual in which the owl’s meat was used and the ends to which the ritual was directed. This was an occult ritual, named in this document as vaśīkaraṇ (subjugation), meant to control the victim: in this case, the monk would use his knowledge of the occult sciences to bring someone under the control of courtesan Situdi’s mother. The vector for creating this new power relationship—of Situdi’s mother coming to possess power over the mind of the targeted person—would be the flesh of an owl.

This association between the owl, the occult, and the town of Pali was not just a one-off. Just two years later, in 1784, another officer in the Rathor capital of Jodhpur, Pancholi Bansidhar sent off an order to the governor of Pali. The news writers’ dispatches (uvākāṁ rī phardāṁ) to the king (śrī hajūr) had contained a report that merited a response. Once more, the Pali governor had failed, in the eyes of Jodhpur administrators, to fully prosecute a crime. A Swami (ascetic) Gaibgir had killed an owl and the bird’s carcass had been used towards occult ends. Both acts clearly did not remain secret. This ascetic’s given name, “Gaibgir,” could have been a Marwari vernacularization either of “Ghā’ibgiri” or of “Ghā’ibgīr.” If the former, he can easily be identified as belonging to the Dasnami order, discussed further on, even as one half of his name, “ ghā’ib,” meant “the unseen” in Arabic and was a central concept in Islamic occult sciences. If the latter, the name was a Marwari vernacularization of the Persian “Ghā’ibgīr,” meaning “possessed of the unseen.” In either case, this ascetic’s name alone points to the inextricably mixed world of tantric and Islamicate occult practitioners on the ground in early modern north India.

When asked, presumably by local authorities, at whose behest he had done these deeds, Swami Gaibgir pointed to Swamis Bhairunath and Mangalbharathi and to one Muhnot Simbhu, identifiable by his name as an Osval Jain. All three of these men were residents of Sojhat, the headquarter of another district in Marwar. For those interested or adept in the occult sciences, sharing ritual technologies meant sharing the ingredients needed for their success. Situated in Sojhat, the Dasnami and Nath ascetics and the Jain expert recognized that procuring owl’s meat required traveling to Pali. Among them, it was Swami Gaibgiri who made the trip there to do so. But once back in Sojhat, Gaibgiri was unwilling to simply pass on the whole carcass to the others but preferred to keep half of it for himself. This suggests the value and relative scarcity of the material, which in turn underscores the significance of Pali as a market town in which rare materials could be found.

Administrators in Jodhpur ordered the magistrate (koṭvāl) of Sojhat to send the three remaining men—Swamis Bhairunath and Mangalbharathi and the Jain Muhnot Simbhu—back to Pali where they were to be interrogated separately. Their testimonies were:

Bhairunath and Mangalbharathi: “Muhnot Simbhu read from a book (pothī) and said, “Wherever there is owl’s meat, human bodies can be controled (pothī vāc nai kayo gūghū ro māṁs kaṭhaiī huvai to mānav deh bas huvai).” In response, Bhairunath had said, “I’m headed towards Pali. If I can get my hands on it, I’ll bring it.” Muhnot Simbhu had responded, “Give some to me too.” Then I [presumably Mangalbharathi] met Svāmī Gaibgiri of our segment (bhāg) to whom I told the method (vidh). Gaibgiri killed and brought it over. Gaibgiri kept half of it and gave half to me.”

Muhnot Simbhu: “I did read the book (pothī) and tell them the details of the method…. I copied the manuscript and gave it to them.”

Writing on behalf of the crown in Jodhpur, an administrator Pancholi Bansidhar reprimanded Pali’s governor for letting the Jain, Muhnot Simbhu, off too easy despite this recorded confession. While the Pali governor had imprisoned the two ascetics, he had released the Jain on bail (jāmaṇ). Finding the Jain’s punishment too light, Jodhpur officers commanded the governor of Pali to now put Muhnot Simbhu in shackles (beḍīyā) and send him, with an escort of guards, to the capital Jodhpur immediately.Footnote 62 It is unclear what fate Muhnot Simbhu met with after reaching Jodhpur. A year later, however, a review of the inmates (bandīvān) housed in Pali’s prison listed the three swamis among those who were to remain behind bars. This was in contrast to sixteen others who were released in order to reduce prison costs.Footnote 63

The suffixes of one of the three swamis’ names, that is “-bhāratī,” along with the possibility of “Gaibgir” being a vernacularization of “Ghaibgiri” with a “-giri” suffix, indicate that these men were Dasnamis.Footnote 64 The Dasnamis, often known as gosāiṁs (gosains) or saṁnyāsīs (sanyasis) were a Shaivite ascetic community that, current research holds, emerged around the late sixteenth century.Footnote 65 The Dasnamis drew widely from the mixed milieu, including Sufi influence, in which they emerged. The Persianate “Swami Ghaibgir” then personifies the richly interwoven world of popular religion and occult practice in early modern South Asia. The third swami, Bhairunath, as suggested by the suffix “nāth” in his name, was likely part of a Nath order of yogis.

It appears from this case that at least some Dasnamis, too, pursued the path of occult and transgressive practices. More importantly, it offers an example of Nath yogis and Dasnamis not only collaborating but also transferring knowledge across orders. The literate Jain’s reading and even copying out of a book (pothī) containing ritual prescriptions for the Nath yogi and Dasnamis he was collaborating with, was an act that transferred esoteric knowledge both across sectarian lines and into the popular milieu. Here we have precisely the sort of popular, diffuse tantric practice that Burchett describes as persisting into the early modern era and which Melvin-Koushki suggests occurred after the de-esotericization of Islamic occult science.Footnote 66 The episode also points to the significance of handwritten notebooks as media for the circulation of knowledge outside of courtly, sectarian, and elite intellectual contexts.

In both the episodes I have discussed so far—of the courtesan’s mother and the ascetics—the goal of the ritual that attracted the state’s wrath was vaśīkaraṇ, or subjugation. Vaśīkaraṇ is one of the representative “six acts” (ṣaṭkarmaṇ) of harmful magic associated with tantra, which include utsādan (destruction), vidveṣaṇ (causing enmity), uccāṭan (expulsion), stambhan (causing paralysis), mahāhānī karaṇ (causing great ruin), and māraṇ (killing).Footnote 67 This kind of “practical magic” is, according to scholars such as Michael Ullrey, also rooted in non-elite traditions that were not textualized and cannot simply be collapsed into tantra. Footnote 68 Whether good intentions or bad were behind the effort to control minds, here we have historical examples of Jain counterparts of the “sinister yogis” that David Gordon White writes about on the basis of tales and lore.Footnote 69

When read alongside the larger literature on the courtly use and patronage of occult sciences in South Asia, Rathor state responses to the deployment of occult skills by their non-royal subjects appear, in contrast to courtly usage, to be hostile. Rathor administrators’ response to the use of owl meat in occult ritual tells us that the flesh of this bird was a key ingredient for formulae geared toward subjugating others’ minds, which in turn was not just pragmatic but also harmful magic. Anyone found guilty of this crime faced harsh punishment. Was this response limited to the use of owl’s flesh in rituals geared towards mind control, or did the Rathor state disapprove of its subjects’ use of magic and occult practices more broadly?

Jain Occultism

In the eighteenth-century records of the Jodhpur state, there are at least two other instances of Jain monks being trapped in the crosshairs of the state on the accusation of trying to subjugate minds. In 1787, the governor’s officers in Pali caught a monk of the Tapā Gacch order of Śvetambar Jains,Footnote 70 Yati Bhojvijay, in the act of performing occult rituals on two subsequent days. First, he was found to have thrown needles without eyes onto the terrace (ḍāglā) of the house of a Brahmin, Vyas Rinchhod. With holders of the title ‘vyās’ doing the prestigious work of courtly tutors and diplomats in Rathor territory, this Vyas Rinchhod likely was a respected figure. The very next day, despite being summoned to the governor’s office and made to explain himself, Yati Bhojvijay inscribed “jantar-mantar” (tantric verses and diagrams) on leaves taken from an ākḍā or crown flower shrub, and carried out an unspecified act.Footnote 71 In Marwar and beyond, the ākḍā or āk shrub was and is considered ritually potent, its parts thought able to counter spells and attract evil spirits.Footnote 72 For this, he was caught again, and this time he named another yati as somehow responsible for the act. The governor of Pali summoned both Jain monks, and had them commit in writing (mucalkā) to paying five-hundred rupees if ever caught performing such acts again.

News of these recent incidents and the responses of Pali authorities reached supervising officers in Jodhpur who once more found the punishment to be insufficient for the gravity of the crime. Reprimanding Pali’s governor, crown officer Muhnot Jodhmal, himself a Jain, commanded from the capital that all the yatis of the Tapā Gacch order in Pali were to be summoned by the governor, made to commit to paying five-hundred rupees if caught for such acts again, and forbidden from stepping onto terraces. Muhnot Jodhmal instructed the governor of Pali to take this action immediately and to send written confirmation when it was done.Footnote 73 To authorities in Jodhpur, Yati Bhojmal’s occult activities were not aberrations but rather part of a wider suspicion of Tapā Gacch Jain monks more broadly as practitioners of the occult sciences. This is why they were all punished and a more symbolic, though still harsh, punishment of being prevented from climbing up to terraces was imposed on them.Footnote 74

The next year, in 1788, a monk of the Khandelwal mercantile caste in Nagaur, most likely of the Digambara Jain order, hired a Brahmin to bring two other Khandelwal Jains, a man and his wife, under his control (“bas ūṇ rā karāyā”) through ritual means (“jantar”).Footnote 75 Officers in the magistracy found out that this monk had paid the Brahmin for his services with fifteen rupees in cash, two pearls, and a coral (mūṅgīyā) necklace. Once more, news of this reached Jodhpur and the two heads of the royal chancery (daftar rā darogā donū) ordered that if the yati had indeed commissioned the magic, he should be properly punished such that he never committed such an act again. The Brahmin occultist, interestingly, was not punished for his role in carrying out the mind control ritual.

Hugh Urban has drawn attention to the neglect in scholarly work on tantra of the pursuit of worldly power, arguing that existing scholarship has tended to sweep aside such goals and give primacy instead to such ideals as attaining immortality and liberation from duality. Instead, Urban suggests that transcendence in tantra has always been centered on attaining power in order to achieve this-worldly success.Footnote 76 Elsewhere, he has noted the contrast between the quite abstract content of Sanskrit tantric texts, on the one hand, and the idea of tantra today in the Indian popular imagination as “a dangerous path that leads to this-worldly power and control over the occult forces on the dark side of reality.”Footnote 77 In these references to the activities of Jain monks as occult practitioners, we get a glimpse of what White calls “pragmatic tantric practice” and Burchett calls “practical magic”; that is, the use of tantra not toward such lofty ends as the perpetuation of a royal lineage or the installation of a deity in a temple but rather toward the short-term needs of more “ordinary” actors.Footnote 78

Practitioners of occult sciences were much in demand for everything from intervening in weather to assisting in fertility issues to—as seen in this article—manipulating the minds of nemeses, beloveds, and others. They possessed a resource, occult skills, sought by people from a range of social backgrounds, from merchants to Brahmins to courtesans’ mothers, to surmount the obstacles that stood in the way of their worldly ends. This was a popular politics, here directed not at the state or the sovereign but at other subjects of the crown. The potential uses of this power to upend social order and political hierarchies, however, was likely not lost on kings and their deputies. In the course of the early modern period, state authority expanded and emergent imperial formations projecting universal dominion became more invested in gathering first-hand knowledge about their subjects. In the eighteenth century, new regional state forms emerged in the wake of Mughal decline. Many of these state forms were much more deeply enmeshed in local society and more capable, due in part to an expanding state apparatus, in terms of their ability to know what their subjects were up to.Footnote 79 But this greater knowledge forced kings to confront the question: What if access to the occult, particularly toward harmful ends, was not just the preserve of kings and adepts and instead was widely available?

Weaving Magic

Neither jantar-mantar nor its particular manifestation as the use of owl flesh for mind control were unique to Jain monks. As we saw in the case involving the group of ascetics in Sojhat, Nath and Dasnami mendicants, too, were interested in learning text-based ritual formulae deploying owls’ flesh. Rathor records also mention the role of weavers (julāvās and sālvīs) as bearers of occult skills. These were predominantly non-literate groups that did not have unmediated access to manuscripts, though this does not rule out access to written knowledge through oral circulation. In 1768, a stonemason (silāvaṭ) in Jodhpur died and his son, Mhaimad, fell listless (bechāk chhai). A woman in the affected family said she knew that another stonemason in the countryside had commissioned a julāvā (weaver) to perform magic (jādū karāyā) upon them. As part of the ritual, an effigy had been buried near a lake. The crown’s officers ordered local authorities to have the stonemason dig up the “wish-making effigy” (kāmnā rā putlā), likely as a means of undoing the spell.Footnote 80 In 1776, a weaver (of the sālvī caste, associated with weaving silk) in Jalor was accused of casting a mantra (spell) using clove (lūng mantrāy) and another one using oil (tel mantrāy) on the veil of a woman of the same caste group.Footnote 81

Weavers’ abilities as occultists enjoyed respect even among the region’s more prosperous residents, including those like Jain merchants who had access to Jain occult specialists that were initiates into lineages and were literate. So, in 1784 a Jain named Khandelwal Ratniya in Nagaur hired a weaver named Julava Abdula, whose name suggests he was Muslim, to counter the ill effects of a curse he believed another Jain, Khandelwal Sukhiya, had cast upon him. Ratniya’s body had been listless (ḍīl becāk) and his spirits (cit ūt) were low.Footnote 82 At the suggestion of his friend, Kandoi (“confectioner”) Gangaram, also a Jain, Ratniya consulted Julava Abdula. This weaver occultist came over to the confectioner’s sweetshop and diagnosed Khandelwal Ratniya’s ills as being magical (jādū) in origin. Julava Abdula performed “lālo-pato,” possibly an exorcism through ululations (as suggested by “lālo”), upon Khandelwal Ratniya.

But this weaver Abdula appeared to be of some renown locally and it turned out that he was also working as an occultist for Khandelwal Jain Sukhiya, the very same man Khandelwal Ratniya had suspected of having commissioned the magic that had made his spirits low. Ratniya realized this when the weaver Abdula offered to excavate an effigy (putlā) that Sukhiya had deployed and bring it over to Ratniya in exchange for some prasād (blessed food offerings) and money. It appears, then, that Julava Abdula had been part of the occult ritual performed on the effigy for Sukhiya and this is how he knew where it was buried. Perhaps concerned by Julava Abdula’s wide and overlapping network of rival clients, Ratniya reported the matter to the magistracy in Nagaur.

Matters escalated quickly, with the magistracy arresting all four men—the two rival Khandelwal Jains, the weaver Abdula (the occultist), and the confectioner friend. The Nagaur magistrate had the weaver and the confectioner tied to a post by their necks and beaten in order to get to the truth of the matter. Eventually, the confectioner Kandoi Gangaram managed to send an appeal to Jodhpur administrators for help. An officer at the capital, Singhvi Chainmal, sympathized, dispatching an order to Nagaur’s magistrate that intervened in the investigation. The order accused the Nagaur magistrate of botching the investigation and reprimanded him for the extreme punishment heaped on the confectioner and the weaver without sufficient cause. It ordered that the matter should be investigated again and whoever was found guilty should then be fined.Footnote 83 An entry in Rathor records dated to a month later notes that all four men—the three Jains and the weaver—remained imprisoned in Nagaur, specifically charged with making an effigy (putlā), and were now to be sent to the capital.Footnote 84 As is often the case with these records, we do not know how officers in the capital allocated blame or resolved the matter, but what stands out is the willingness of the state to carefully investigate before arriving at a judgment or punishment. This is in contrast to its response to the allegations against Jain monks discussed earlier, in which Rathor officers express a hurry to immediately and harshly punish the monks accused of magic.

At the same time, the practice of magic—jādū-ṭunā, jantar-mantar, or ṭānar-ṭunar—was not safe for most ordinary or non-courtly actors. All the non-courtly practitioners described in Rathor records appeared to operate through word of mouth and behind closed doors (or on rooftops). Accusations of knowing or performing magic could be threatening as is also made clear by an episode in which a Sipahi, from a Muslim caste of Rajputs, tried to scare a qāẓī (Islamic judge) in Nagaur by telling him that he was aware of a royal order stating that the qāẓī knew magic (tū jādū ṭunā kar jānai chai). The Sipahi flew into a rage when the qāẓī did not take him as seriously as he liked. The Sipahi hurled abuses at the qāẓī, threatened him with his sword, and created a ruckus. Hearing of this in Jodhpur through news writers, the crown’s officers commanded Nagaur authorities to deny the Sipahi a month’s salary as punishment. Once guilt was established, punishment for practicing magic could be harsh, as is clear from a 1776 order to expel the weaver of Jalor, discussed earlier, who had been accused of casting spells on a woman of his caste using cloves and oil as magical media.Footnote 85

What was it about weavers that led others to consider them skilled practitioners of magic? Given the mere glimpse of the magical practices of weavers that these sources provide, and with little insight from other parts of South Asia, it is only possible to offer some preliminary speculations. From the early seventeenth century onward, South Asian textiles had found new markets all over the world, with traders carrying them to Europe, the North Atlantic, Africa, and Southeast Asia. With Marwar being just north of Gujarat and with Pali being the hub for trade that it was, the weaving sector in Rathor territories may have experienced an expansion. Printed textiles from Pali were appreciated for the exceptional vividness of their colors. Could skillful transformation of yarn into bales of fabric lapped up by eager merchants have facilitated the association of magical power with weavers? Or did weavers’ regular interaction with merchants—who lent money, provided raw material under the putting-out system, and bought goods in exchange for currency—draw weavers closer into the world of moneyed patrons looking to harness any and every kind of magic toward their worldly goals? Perhaps a range of different caste groups and communities had their own tradition of magical practice but weavers’ interactions with the region’s commercial classes brought their magical skills into greater circulation than others. Weavers also circulated through pilgrimage networks that were an anchor of the popular practice of Islam in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century north India.Footnote 86

Alternatively, or perhaps alongside, the immense symbolic and ritual power of cloth in South Asian culture and society imbued to its makers—the weavers—a special ritual status of their own. Cloth was said to be able to influence the substance and spirit of its wearer, based on who and what it had touched before, its color, and its material. It could also acquire qualities from those that had touched or worn it before.Footnote 87 Cloth served as a medium for the forging of relations, with ritually potent gifts of cloth being made between husbands and wives, devotees and temples, and kings and their subjects. Weavers navigated a liminal location in this context: as non-agrarian, artisanal producers they held a low caste rank, but as creators they were regarded as laudable.Footnote 88 They were thus both lowly and valued makers of ritually significant materials that, in turn, wove together the social, political, and ritual order.

From the aforementioned cases recorded in Rathor documents, it appears that weavers’ magic was reputed to subjugate minds and to weaken bodies (victims reported “bechāk ḍīl”/a listless body or a sad “chit-ūt”/spirit). The attribution of magical prowess to weavers persisted into the modern period and a late nineteenth-century census and ethnographic survey of Marwar, the Mardumshumari Raj Marwar of 1891, reports that julāvās as a community were associated with the practice of “jantra-mantra.” The survey notes that julāvās were even then associated with the practice of exorcism (jhāḍā phūṅk) and with having performed astonishing miracles in the remembered past, countering “even” the powers of Jain monks.Footnote 89 In a context in which performing everyday magic attracted state punishment, eighteenth-century Rathor orders responding to weavers’ spells testify to the enduring popularity of occult skills in the face of state opprobrium. For a non-elite community such as that of weavers to continue to practice occult skills in eighteenth-century Marwar, despite the threat of state punishment, suggests that despite prohibitions and disapproval from an expanding Vaishnav devotional sphere, a clientele for occultists continued to exist.

Variations: Rituals and Responses

A clue to understanding Rathor punishment of the occult use of owl’s flesh may lie in assessing how the Rathor state treated these other reports of occult practices not involving owls or other animal flesh. As discussed, the media used by yatis and weavers in such rituals included effigies, needles without eyes, oil, cloves, and mantras (verbal enunciations). In response to all of the reports of occult rituals, even when they did not deploy animal flesh, the crown and its provincial officers reacted with punishment, usually arrest and in one case expulsion from the town. Clearly, the Rathor state disapproved of occult practices—whether jantar-mantar, ṭānar-ṭunar, or jādū—and used its surveillance machinery and punitive weight in an effort to stamp it out.

Two groups emerge as prominent in the accusations of magic and occultism that made it into the administrative records of the Rathor court: ascetics, particularly Jain monks, and Muslim weavers. A Brahmin was involved in one allegation, but the state did not punish him. A qāẓī was accused in another case but the state appears to have considered this an entirely false accusation. Looking at these documentations of Jain and weaver magic, some contrasts emerge. As noted above, Jain monks faced quick and harsh punishment by the state for occult practice. Weavers faced harsh punishment, too, but it was usually handed out only after an investigation.

Another contrast emerges between the two groups: the monks were accused of carrying out rituals that could result in the subjugation of minds whereas the weavers tended to be accused of casting spells that weakened the body and lowered spirits. These appear to be distinct specializations, likely drawing upon different bodies of knowledge. Another difference is that while the weavers used media like effigies, oil, and clove in their rituals of healing and illness, Jain monks promised mind control through the use of devices (jantar), verbal or written spells (mantar), and textually derived prescriptions, each of which could be applied upon materials considered fecund in terms of occult potential. From Rathor records we know that these materials included lemons, metal needles without eyes, parts of the āk shrub, and owl’s flesh.

The terminology used to denote the occult skills of the Jain monks, too, was distinct from that used for weavers’ magic. So, while weavers were accused of “jādū” or “jādū ṭunā” (roughly magic or magical incantations), Jain yatis were accused of jantar mantar or ṭānar ṭunar, pointing to a knowledge emerging from textual prescriptions of potent diagrams and verbal formulae. The former category—jādū—is also a Persian word meaning “conjuration” or “magic.”Footnote 90 This could point to the association of weavers’ occult skills with Persianate occult science, whereas the terms used for Jain monks’ magic evoke tantra. Weavers and Jain yatis, then, had different specializations, appeared to draw upon different bodies of knowledge, and elicited different responses from the Rathor state’s officers. Jain monks triggered much more alarm and a quicker punitive response.

The Occult as Political Resource

The state punishment of occult practice reflects the Rathor court’s investment in controlling access to the use of occult powers for practical and harmful ends, seeking to monopolize this resource for the king’s use alone. Circling back to the scholarship on the occult as a technology of imperial power in early modern Islamicate empires, the Rathor state’s effort to punish expert practitioners of jantar-mantar and jādū and its disapproval of magic more broadly points to the emergence in the course of the early modern period of the occult as a site for political contestation: the exercise of kingly power extended to the control of occult technologies. The popularization of occult practices when combined with their significance to Persianate kingship, including in its Rathor avatar, could cause, as it did in eighteenth-century, post-Mughal Marwar, an effort to control access to skilled occultists.

A number of other concerns came together, I suggest, to cause the officers of the Rathor state to punish Jain yatis accused of using owl flesh and of occult practice. First, the authors of most of the commands issued on behalf of the Rathor crown were Jains themselves. Since the sixteenth century, successive Rathor kings of Marwar had incorporated men of mercantile castes into their administration in growing numbers. Many of these merchant-caste or Mahajan officers, who by the eighteenth century dominated a much-expanded Rathor bureaucracy, were Jains. Other Mahajans were devout followers of the Krishna-centered Vaishnav devotional order, the Vallabh Sampraday.Footnote 91 The king of Marwar, Maharaja Vijai Singh, took initiation into this order in 1765, inaugurating a few decades of lavish and public investments in Vaishnav devotion in the kingdom.Footnote 92 In the late eighteenth century, the Mahajans of Marwar were in the process of engineering a realignment of the region’s social order so that they could be counted among the most elite.Footnote 93 Leaders of Vaishnav devotional orders, like the Vallabh Sampraday, in turn made a decisive shift in the eighteenth century toward trying to “cleanse” themselves of heterodox practices, including traces of tantra. Footnote 94 Following their lead, devotee kings such as Maharaja Vijai Singh also projected a public image of vegetarian and temple-centric Krishna devotion.Footnote 95

This complex of factors: an aspirant and upwardly mobile mercantile elite, the flourishing of Vaishnav bhakti among merchants, royal enthusiasm for bhakti, the “cleansing” drive in bhakti, and the effort to weed out still persistent occult practices—may have combined to generate a distaste for occult practice among some Jains who were part of this interconnected mercantile world. It is possible, then, that powerful Jain officers at court were swift to punish Jain monks indulging in occult practices now deemed incompatible with elite status. John Cort has noted that by the twentieth century Jain reform movements had nearly eliminated the institution of yatis. Jain reformers also worked in the twentieth century to weed out practices now deemed improper in Jain worship. This included the prohibition of the ritual sacrifice of animals in rites presided over by yatis. Footnote 96 It is possible that in these last decades of the eighteenth century, sections among the Jains were already dissatisfied with the activities of yatis.

The hardening of attitudes towards tantric practice, especially that which involved the use of animal flesh, was part of a wider shift in Marwar toward new forms of religiosity that posited a different relationship with the divine, different bodily regimes and forms of discipline for their practitioners, and a new relationship with non-human beings. This shift entailed a much more extensive implementation of normative codes of non-harm between humans and animals.Footnote 97 Still, even as Marwar was in these same decades in the grip of a state-enforced campaign to protect animal lives and prevent the killing of all creatures, the Rathor response to the killing of owls for use in occult ritual does not appear to stem from the same concern for animal life. All the orders seeking to punish violators of the Rathor ban on animal slaughter label the crime “jīv haṁsyā” (violence upon living beings) but the commands in response to the use of owl flesh in occult ritual do not categorize these acts as jīv haṁsyā. Despite not seeing these cases as instances of violence against animals, it is abundantly clear that the Rathor state had zero tolerance for the killing and use of owls for occult rituals. The reason for this was that occult rituals using owls were a particular type of practical magic and were rituals of this-worldly, interpersonal domination, meant to subjugate a person to another’s will in ways that could bring harm.

Why the Owl?

Since premodern times, the owl has been associated with desolation, death, and dangerous power across many cultures. In Rajasthan, the owl’s association with ruins, thought to be inhabited by dangerous spirits of the deceased, lingers until today. In her ethnographic work on place-making in rural Rajasthan in the 1990s, Ann Grodzins Gold writes about an “Owl Dune,” or ghūgh thaḷā, on the outskirts of a village in Rajasthan that is about 250 kilometers away from Pali.Footnote 98 The Owl Dune was a sandy rise in which the ruins of an abandoned settlement were visible in crumbling walls and stone bricks strewn about. Gold attributes the Dune’s name to the inauspiciousness associated with the owl’s voice, a sign of desolation, abandoned cities, and collapsed kingdoms.Footnote 99 This was not a sacred landscape, but neither was it one devoid of ritual potency. It was home to unknown spirits of the deceased who had not received the identification, enshrinement, and care by living persons that transformed spirits into benign deities and benevolent ancestors. Instead, these unknown spirits, Gold suggests, were potentially threatening.Footnote 100 In Persian poetry as well, the owl was a “sinister” bird, always associated with desolation and ruins.Footnote 101 By naming this space—both alluring due to the treasures that some believed lay buried there and fearsome due to the untamed spirits that dwelt in it—after the owl, the area’s inhabitants signaled this land formation’s dangerous potency.

The owl’s nocturnal habits may have fueled its association with the liminal space between light and darkness and perhaps by extension, between life and death. Its location on the boundaries of the familiar and the “normal,” and the unfamiliar and the “deviant,” may have been the source of the power that was associated with the owl. The owl is a bird of prey and bears the ability to take life and consume flesh. Owls can turn their heads to a degree that is strange to human observers, with some species able to rotate their heads in a range as wide as 270 degrees. Owls have front-facing eyes and a flat face that gives them a more human-like appearance than other non-humans possess. Owls are in that sense on yet another borderland—between human and animal. Being nocturnal and wild creatures, owls entered human spaces and fields of vision at the margins of day and night, on the peripheries between life and the ruins left behind by death and inhabited by spirits, and on borderlands between settlement and wilderness. Jahangir, too, spotted the owl he shot down at dusk. In the historical episodes from eighteenth-century Marwar discussed above, owl’s flesh appears to have been valuable and its procurement took some trouble, suggesting that finding and trapping an owl was not easy.

Going back to the owl, in ritual terms it lies firmly outside the category of animals whose ritual sacrifice is permitted and prescribed by the Vedas. This is because it is a wild animal. While the Vedas and Brāhmaṇas prescribe the sacrifice of domesticated animals, they also emphatically proscribe the sacrifice of wild animals. Tantric ritual, by contrast, demands the sacrifice of wild, undomesticated animals. In this sense, the sacrifice of owls and, by extension, the use of owls’ flesh as recorded in these cases was a deliberately transgressive practice, one that stood in a relationship of tension with Vedic ritual.Footnote 102 Eighteenth-century western India saw the fashioning of a “Vedic” kingship, with Maharaja Jai Singh II (r. 1699–1743) of Jaipur spearheading this new articulation of monarchical authority and extending this vision into the shepherding of leading Vaishnav orders toward greater conformity with practices deemed Vedic.Footnote 103 Transgression of Vedic prescriptions was then not just a violation of distant textual norms but rather, from the perspective of ruling elites aspiring to conformity with a new orthodoxy, a more immediate departure from the vision they had in mind for the polity they were crafting.

The link between the owl’s liminality and connections to veiled realms points in turn to the association of liminality more generally with occult power. Those configured as liminal were considered fecund in occult power and could be fused together in the occult imagination and that of its critics. So it is that the tantric concept of the yogini, a superhuman female figure able to fly and bring death as well as liberation, could be fused with birds such as the owl. In tracing prehistories of the yogini concept, White points to a verse in the Rig Veda that warns against apsarās, or nymphs, who take the form of an owl: “the “she who ranges about at night like an owl, hiding her body in a hateful disguise.” There is an ambiguity here that we will encounter again with the yoginis: it is difficult to determine whether the sorcerers and sorceresses here are super- or subhuman beings, or simply humans in the guise of birds or animals of various sorts.”Footnote 104

In this worldview, women and wild beings are fused together as possessors of occult energies. This echoes the aforementioned association in early modern Europe between witches and their “familiar” animals. It is worth noting also that the expert occultists I have discussed in this article—itinerant monks and socially marginal weavers—were liminal in terms of their relation to the social order. Being perceived as an outsider, as one who did not quite belong, cemented an association with danger and with occult power. This in turn offers a glimpse of the ways in which occult knowledges and practices interacted with and sometimes replicated social hierarchies of gender and caste. Taken as one in a wide arsenal of occult tantric practices—ranging from the tactile to the abstract—owl’s flesh acted as a medium for channeling into one’s own self that power which lay in the margins and interstices of the normative order, and which had the ability to upend it.Footnote 105

Conclusion

In India today, there is a vibrant trade in owls, albeit one that is conducted illicitly. Hunting and trade of all the owl species of India are prohibited under the country’s Wild Life (Protection) Act of 1972. The greatest reason for the persistence of this trade, according to a 2010 report, is the use of the owls in ritual.Footnote 106 Practitioners of tantra, whether self-styled tāntriks (tantra practitioners) or initiates into orders, prescribe the ritual sacrifice of the owl and the use of its body parts to clients pursuing such goals as greater wealth or the warding off of the “evil eye.” The eight-year study of the owl trade in India recorded over a thousand owl sales, that being only a fraction of the actual number. While the owl market is perennial, demand peaks around the autumn festival of Diwali, and to a lesser extent around Holi in the spring. Sacrificing an owl on the amāvasyā, the moonless night, on which Diwali occurs—celebrating the mythic king Rama’s victorious return to his capital Ayodhya in the epic Ramayana as well as the lunar New Year—is said to greatly enhance the ritual’s efficacy. Further, the owl is also the vāhana or vehicle of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, who is the object of veneration on Diwali and who is said to bestow her blessings upon deserving devotees on the night of Diwali.Footnote 107 This perhaps is an added reason for the connection between the festival and owl sacrifice. In any case, the owl continues to be at the center of a burgeoning trade that spans the Indian subcontinent, one whose routes even traverse international boundaries.Footnote 108

The owl occupies an ambiguous place in India, being considered a harbinger of both good and evil. An owl may be seen as a sign of good things to come—its sitting on a man’s head is a sign of prosperity on the horizon and its perching on a woman’s head is an omen that she will soon be “blessed” with a son. At the same time, the owl is and was also considered to bring ill fortune.Footnote 109 An owl landing on a person’s home may be considered a sign of an imminent death in the family. Despite the occasional positive association, however, the owl in sections of the Indian population today evokes fear and trepidation.Footnote 110

Turning back to the early modern period, paying attention to the owl’s appearances in Mughal and Rathor records tells us of the potency of wildness, of liminality. While horses and elephants were sites of affective response, symbols of prestige and lordship, the owl evoked fear, awe, and among kings, contest. It could not be controlled in life but only in death, the power attributed to it unleashed through the application of verses and ritual upon its flesh. Liminality, both social and spatial, was a source of power in the occult imaginary. In this imagination, liminal beings of different species, such as women and owls, that were considered fecund in occult power could be fused together.

Ethnographies and histories have emphasized the intimacies, relatedness, and affective ties that characterize non-modern modes, past or present, of living with animals. Rohan Deb Roy has warned scholars of human-animal relations to avoid falling into the trap of conjuring an “analytically ‘flat’ world characterized by happy intermingling and happy dialogues” and argues instead for the importance of paying attention to violence, inequality, and extraction as important forces in these co-constituted histories of humans and nonhumans.Footnote 111 An important aspect of those regimes of ontological violence and inequality was the classing by humans of nonhumans into categories that both shaped and were shaped by interspecies interactions. These were not the fabulous fantasies of elite writers of technical manuals and occult grimoires but had real-world impacts on the lives and deaths of nonhumans. For owls, being classed into a liminal space between known and unknown, light and dark, had dire consequences. The traces that the owl has left upon documentary fragments from early modern South Asia make clear that humans responded to owls by deeming them bearers of occult powers and ill omen. This was not just an instrumental use of the owl, but rather a deployment of its power that was grounded in feelings of fear, wonder, and awe towards the creature.

For the burgeoning history of occult knowledges and practices in Asia, whether Islamicate or tantric, this article demonstrates the popular, extra-courtly patronage and use of magical formulae and the deployment of occult practitioners. Not only kings, aristocrats, and adepts but also less-elite actors turned to occult practices as one among the arsenal of “weapons” they could wield in social and interpersonal conflicts. Jain tantric specialists and weavers of a Muslim caste attracted clients seeking to control minds or unleash ill health upon rivals. Magic and counter-magic were interwoven with the fabric not only of elite science and politics, as scholarship on occult science has so far shown, but they were also integral to the negotiation of social conflict and local micro-politics in early modern South Asia. Popular access to occult practices with the potential to do harm and disrupt social order was a cause for concern to kings and states. In Rathor Marwar, occult practitioners and their patrons were harshly punished. Occult science was a tool of imperial power but for this tool to be effective, sovereigns sought to restrict access to it.

Even as scholars of tantra have theorized its continued use, whether as tantra or in other traditions that absorbed its perspectives or techniques, I have shown in this article precise historical examples of this popular use and circulation across religious orders. The administrative records of early modern polities offer new possibilities for histories of the occult in early modern Asia, making possible local, on-the-ground histories of the use of occult technologies and sciences beyond courts and scholarly practitioners. Building on scholarly rejections of Enlightenment separations between “religion,” “science,” and “politics” in premodern societies, centering the occult permits a new perspective upon the political domain in the early modern Persianate world, from the interpersonal to state-subject dynamics. Centering the popular realm points to the continued vitality of a blended tantra-Islamicate world of knowledge despite the rise at the elite levels of Vedic kingships and orthoprax Vaishnavism. A focus on the popular also makes possible a sense of the mechanics of how knowledge flowed between literate and non-literate realms and between religious orders.

The owl, as a potent medium for occult power and as an omen that was rich with symbolic meaning, traversed the seemingly disparate worlds of seventeenth-century Mughal kings and eighteenth-century weavers as a means to worldly power. Recent scholarship on Mughal India has pointed to the role of religion in popular politics, and my findings here suggest that the wider umbrella of “religion” also included branches of occult knowledge that not only emperors but also more ordinary denizens of early modern South Asia deployed toward political ends. A changed relationship with laboring, pet, and prestige animals—marked by new separations and distance from humans and caused by new organizations of land, labor, and state—is a marker of modernity, as Mikhail has argued for Ottoman Egypt. The story of the owl, whose relationship with humans was marked by liminality and deferential fear, points to other kinds of human-animal relations in the Persianate world generated by the effort to discipline the occult away as the eighteenth century came to a close.

Acknowledgments

I thank Joel Bordeaux for a generative early conversation and Shahzad Bashir, Patton Burchett, John Cort, Purnima Dhavan, John S. Hawley, Abhishek Kaicker, Mana Kia, Naveena Naqvi, Hasan Siddiqui, and Holly Shaffer for their comments on earlier drafts. I am grateful to the participants of the Columbia International History Workshop where I presented a version of this paper in March 2022, and to the anonymous CSSH reviewers for their suggestions. Thanks are also due to the Chester Beatty, Dublin for granting me permission to reproduce an image from their collection.