Competition, in the form of jurisdictional conflict, thrives both between and within professions. As Reference AbbottAbbott's seminal work on the professions suggests, “[t]he stories that need to be told are not stories of professions but of jurisdictions and jurisdictional conflicts” (1986:187). His early writings highlight “jurisdictional disturbances” and how new technologies or organizations create new areas for professional work. As professions shift to serve these emerging areas, other jurisdictions are left weakened. Other professions may then attack those weakened jurisdictions, with disturbances “propagating” elsewhere. Reference AbbottAbbott contends that similarly “technologies and organizations may disappear, leaving professions without functions, on the prowl for work” (1986:187). This interdependent system of professions (Reference AbbottAbbott 1988), or ecology of professions (Reference AbbottAbbott 2005), reveals how professions seek to aggrandize themselves through competition, taking over areas of work and then constituting these areas as “jurisdictions” by means of professional knowledge systems. As Abbott observes:

A variety of forces—both internal and external—perpetually create potentialities for gains and losses of jurisdiction. Professions proact and react by seizing openings and reinforcing or casting off their earlier jurisdictions. Alongside this symbolic constituting of tasks into construed, identified jurisdictions, the various structural apparatuses of professionalization—growing sometimes stronger, sometimes weaker—provide a structural anchoring for professions. Most importantly, each jurisdictional event that happens to one profession leads adjacent professions into new openings or new defeats.

(Reference AbbottAbbott 2005:246)Although numerous studies have explored jurisdictional conflicts between professions (Reference DevineDevine et al. 2000; Reference TimmermansTimmermans 2002), less attention has been directed to understanding intraprofessional competition (although see Reference AbbottAbbott 1981; Reference KenneyKenney 2004). Yet jurisdictional conflicts abound within professions. It has long been observed that “professions consist of a loose amalgamation of segments which are in movement” (Reference Bucher, Strauss, Vollmer and MillsBucher & Strauss 1966:193). This movement is one of jurisdictional flux that may be characterized by harmony, friction, and on occasion invasion. In the case of the legal profession, Reference AbbottAbbott (1988) notes how the emergence of the large law firm enabled the seizure of massive new work for big business and interventionist government. The losers were both solo and small-firm lawyers. Thus, size and bureaucracy confer competitive advantage (Reference AbbottAbbott 1988:152–3). Rapid and profound changes within the profession (e.g., globalization, specializing, multidisciplinary bureaucracies) may also contribute to jurisdictional conflict. These changes reshape the roles of professionals and aggravate tendencies toward stratification, concentration, and marginalization (Reference Arthurs and KreklewichArthurs & Kreklewich 1996).

This study examines intraprofessional conflict in the legal profession in Québec, Canada. In recent years, a dramatic shift in power has transpired, altering the equilibrium between the profession's two streams, the notaires and the avocats. Notaires (Latin notaries), originally the “first” legal profession in Québec and once heralded as “defenders of the Code Civil,” have lost substantial jurisdictional terrain and political influence. The overwhelming majority of law school graduates now pursue careers as avocats (lawyers or litigators) rather than as notaires, and avocats are increasingly the architects of Québec's justice system—determining law school curriculum, leading law as judges and through legislative power, and litigating between evolving forces of corporate business and state regulation in Québec. Notaires seem to be losing the professional competition. This article seeks to understand why, through an investigation of earnings differences.

The literature on both inter- and intraprofessional competition has examined professions' symbolic and political efforts to win “turf” or jurisdictional battles, but little work has examined earnings as part of this process. This article extends research in three ways. First, the bulk of research on the legal profession has tended to focus almost exclusively on lawyers working in law firms (Reference Beckman and PhillipsBeckman & Phillips 2005; Reference Galanter and PalayGalanter & Palay 1991; Reference GormanGorman 2005), to a lesser extent lawyers in solo practice (Reference SeronSeron 1996; Reference Van HoyVan Hoy 1997), and primarily within common law jurisdictions (for exceptions, see Reference Friedman and Pérez-PerdomoFriedman & Pérez-Perdomo 2003; Reference KarpikKarpik 1999). My work broadens analyses to consider, within the tradition of civil law,Footnote 1 legal professionals working across an array of practice settings. Second, while macro-sociological considerations focus attention on the territorial and status struggles between professions (Reference AbbottAbbott 1988; Reference AbelAbel 2003; Reference HallidayHalliday 1987; Reference MoorheadMoorhead et al. 2003), little research has explored dynamics internal to a divided profession. My analysis examines two subgroups within the legal profession during a time of intense jurisdictional contest. Third, to date earnings have been treated simply as an underlying dimension of intraprofessional hierarchies, though the coupling between prestige and earnings is inconsistent (Reference AbbottAbbott 1981:821). However, while jurisdictions between notaires and avocats may influence each group's respective earnings levels, it is also conceivable that jurisdictions shape the processes through which earnings are determined. I therefore extend theoretical perspectives to provide a fuller account of how earnings are generated across competing realms of law practice.

A comparative study of legal careers in Québec cannot be fully understood without a sufficiently nuanced interpretation of the historical and cultural context of civil law legal practice. I therefore begin with an overview of several key distinctions: education and professional training, legal jurisdictions, historical development, and contemporary disputes over governance. I next outline theoretical explanations of earnings determination. The third section then examines these models through analyses of two large-scale surveys of the profession. I conclude in Part IV with a discussion of the contribution offered by these contrasting socioeconomic explanations and directions for advancing understanding of intraprofessional rivalry and earnings.

One Profession, Two Streams of Practice

Canada's legal profession is intriguing and atypical in that both common and civil law traditions coexist within one country. The private law system of Québec operates under civil law originating with the French settlers in the 1600s. The public law system and court structures of Québec are based on a common law system shared with other Canadian provinces. Matters such as constitutional, criminal, and administrative law fall under the rubric of public law (Reference Eliadis, Allard and GallEliadis & Allard 2004:265). This legal hybrid is unique to Québec. Laws in “English” Canada—that is, provinces and territories outside Québec—were established by British colonization and developed as common law jurisdictions (Reference Eliadis, Allard and GallEliadis & Allard 2004; Reference HowesHowes 1987). The structure of the profession also varies across Canada. In English Canada, lawyers operate as “barristers and solicitors,” although they may choose to classify their work as primarily that of a solicitor or as a barrister or litigator. Notaries exist, although in restricted numbers, without the requirement of a law degree, and are largely limited to administering oaths and attesting documents (Reference BrockmanBrockman 1999). In contrast, the Québec notaire (Latin notary) holds a law degree and a far broader jurisdictional mandate than that of the notary public in English Canada and the United States.

The Québec legal system regards both professional groups, avocat(e)s and notaires, as integral members of la profession juridique (the legal profession; Reference LambertLambert 2008).Footnote 2 Moreover, notaires and avocats share common roots through law school education, professional training, and at times overlapping domains of law.

Both notaires and avocats attend law school. The two streams specialize in their third year. Notaire students remain an extra year, leading to a diploma in notarial law, followed by a 32-week articling period (e.g., apprenticeship) under the supervision of La Chambre des notaires du Québec (CNQ), and an evaluation, after which individuals are officially sworn in and admitted to the profession as notaires. By contrast, after their third year of law school, avocats write the bar admissions exam, followed by a four-month period of articles under the supervision of Le Barreau du Québec (BQ) (Reference KayKay 2009a).

The legal positioning of the notaire is uniquely distinct from that of the avocat. As legal counsel, notaires may express opinions in all areas of law. Yet unlike avocats, notaires are public officials, required to exercise neutrality and provide advice to all parties involved (Reference Brierley and MacdonaldBrierley & Macdonald 1993; Reference Kimmel, Landry and CaparrosKimmel 1984). As such, the notaire provides information about rights and obligations attached to various legal actions (La Chambre des Notaires du Québec 1993). For example, the notaire provides confidential legal advice on family affairs, secures charters for joint stock companies, receives oaths and statutory declarations, is entrusted with the management of estates, files reports on titles, negotiates loans, and acts as agent for the sale of real estate (Reference DemersDemers 1985:57–71; Reference VachonVachon 1962:40). Notaires draw up practically all deeds concerning real estate or immovable property, and since 2002, notaires have also held the authority to proclaim marriages and civil unions. By contrast, avocats represent clients in areas of law that typically involve court appearances (e.g., criminal cases, civil litigation, divorce). Litigation and advocacy are reserved for avocats, and it is only avocats who can be appointed judges (Reference Kay and BrockmanKay & Brockman 2000:50). The core distinction between the profession's two groups is perhaps not substantive areas, but rather the distinction between litigation and advising/preparing legal documents.

The respective practices of avocats and notaires occasionally overlap, and territorial disputes are inevitable. For example, while avocats hold a general monopoly on litigation, notaires are allowed to appear before the courts in noncontentious civil law matters. During the 1990s, in response to the perception of growing judicialization in legislative processes, the CNQ sought to promote the expertise of its members in nonjudicial dispute resolution (Reference Brierley and MacdonaldBrierley & Macdonald 1993; Reference NoreauNoreau 1992), and notaires came to play an important role in family mediation, a process required by Québec law prior to divorce. Yet competition between the two professional groups is most contentious when it comes to the Code Civil.

The Code Civil embodies the “articulation of normative rules as an expression of a society's principles and values” (Reference GallGall 2004:264). The profession that is positioned to design, communicate, and implement the Code assures itself of social and legal authority (Reference Brierley and MacdonaldBrierley & Macdonald 1993). Not surprisingly, therefore, the Code Civil retains an iconic stature in the official discourses of the BQ and the CNQ. These two associations bring each group together in forums where their boundary disputes can be recognized and decided (Reference AbbottAbbott 1988:165). These associations also protect claims to knowledge expertise (Reference LarsonLarson 1977) via control of recruitment and training of new entrants and conduct and standards of work by individual professionals (Reference DevineDevine et al. 2000:522). In part, motivated by the desire to guard jurisdictions of practice, these associations vigorously debate proposed governmental reforms to the Code Civil, each publishes a periodical journal featuring civil law commentaries, both fund civil law research, and each strives to determine law school curriculum (Reference Brierley and MacdonaldBrierley & Macdonald 1993).

Similar to the legal profession in France, professional jurisdictions and professional structure in Québec were formalized through legislation or decree (Reference AbbottAbbott 1988:27). Notaires were by law and culture the first and more prestigious profession of law in la Nouvelle France and remained throughout their history more evenly represented than avocats across the province (Reference MorinMorin 1998). Historically, the situation of the notaires was certainly more enviable than that of their colleagues in the bar. Prior to Confederation (1867), the number of notaires outnumbered avocats by at least a narrow margin (1,355 compared with 1,322 for the period 1760 to 1867; Reference MorinMorin 1998:311). Yet in recent years the centrality and influence of notarial practice have eroded, with avocats staking claim to the helm of governance over Québec legal professionals. Today it is the avocats who dominate the legal profession through their legislative roles and sheer numeric majority. Currently, avocats represent 87%, and notaires just 13%, of Québec's legal profession.

In contemporary Québec, both notaires and avocats share a growing concern over falling prestige, encroachment by other professions, reduced access to law among the poor, and shifting markets for legal services. However, notaires face tougher challenges as a result of declining numbers, changing fee structures, and the realization of slipping under the shadow of the BQ when it comes to law reform and political power (Reference KayKay 2009b; Reference ThomassetThomasset 2000). Scholars know very little about the place of earnings within these “jurisdictional disturbances” (Reference AbbottAbbott 1986:187). Yet Reference AbbottAbbott contends that “[j]urisdictional claims furnish the impetus and the pattern to organizational developments” (1988:2), possibly including the generation of earnings.

Explanations of Earnings Inequalities: Theoretical Expectations

The perception that avocats generally make more money than notaires is well known among legal professionals in Québec. The task is to investigate and explain this disparity. This task raises three questions. First, do notaires tend to have lower levels of the factors that are expected to increase earnings? Why? Second, if so, do these differences explain the full earnings gap, or is there a residual negative effect of practicing law as a notaire? And third, if there is a residual effect, does some of it arise because notaires obtain lower “returns” on their levels of key factors? Why might notaires suffer diminished earnings for similar professional investments and parallel work settings?

The literature on earnings offers three dominant explanatory models that shed light on the earnings gap between notaires and avocats. The first approach, derived from the discipline of economics, is that of human capital and emphasizes the impact of education and professional training on productivity and efficiency in the workplace. The second perspective, originating in sociology, I call “social-symbolic” capital. This approach highlights the import of relational and symbolic processes to earnings. The third approach, an organizational-structural model, underscores the role of organizational segmentation in generating earnings. Yet these models explain earnings differences across individuals, rather than across subgroups of a profession. I therefore extend theorizing by developing expectations for differences in the effects of these three sets of factors across the two professional groups.

Human Capital

The human capital model has become a baseline model for nearly all investigations of earnings inequalities (Reference Tomaskovic-DeveyTomaskovic-Devey et al. 2005:58). Human capital refers to human competence that is acquired through investments in education, job experience, and skills that generate earnings returns in the labor market (Reference BeckerBecker 1994). The theory contends that in the absence of more direct measures of productivity, employers use these various indicators to gauge the potential of an employee. Hence, employees with more and superior-quality education are expected to have both advanced skills and a higher capacity to learn new skills (Reference Brown and JonesBrown & Jones 2004). According to human capital theory, employers recognize these skills and compensate those possessing skills with higher earnings (Reference BeckerBecker 1994) in an effort to retain them.

This process may prove relevant to understanding the earnings gap between notaires and avocats. In some respects notaires have a professional edge, with more years of university education and an extended articling phase. Yet their human capital acquisition of a diploma in notarial law may not hold the symbolic value of entry to the bar or the career opportunities that are specific to law firms and litigation practice, traditional routes of avocats.

Social-Symbolic Capital

This brings me to the second explanatory model: social-symbolic capital.Footnote 3 This model incorporates a trilogy of social capital, symbolic capital, and dispositional qualities. The first element, social capital, posits that individuals acquire resources that embody a network of relationships. These connections are vital to attract clientele (Reference KayKay & Hagan 1998), access information, invite career sponsorship (Reference Sagas and CunninghamSagas & Cunningham 2004), and impress employers to offer income rewards (Reference DinovitzerDinovitzer 2006; Reference Kay and HaganKay & Hagan 1995; Reference Sandefur and LaumannSandefur & Laumann 1998). In addition, participation in diffuse social networks enables legal professionals to build reputations (Reference BurtBurt 2005). Thus legal professionals are able “to get ahead by managing impressions, developing positive local reputations, impressing gatekeepers, and constructing social networks” that prove instrumental to earnings attainment (Reference DiMaggio and MohrDiMaggio & Mohr 1985:1235–6).

A second element of the social-symbolic capital explanation is symbolic capital, which represents a form of capital that lends legitimacy and status. Graduation from an elite educational institute (Reference BourdieuBourdieu 1980) and the prestige of legal specializations (Reference Dezalay and GarthDezalay & Garth 1996:18) constitute such capital. However, both are difficult to gauge because prestige “exists only, and through, the circular relations of reciprocal recognition among peers” (Reference BourdieuBourdieu 1985:19). Symbolic capital is thus dependent on its affirmation by communicative practices and in this regard is merely a subjective reflection of a worthy endowment of capitals (Reference BourdieuBourdieu 1985:19; Reference JoppkeJoppke 1986:60).

A third and final element of social-symbolic capital is dispositions, a system of thought that makes possible expressions and actions “whose limits are set by the historically and socially situated conditions of its production” (Reference BourdieuBourdieu 1980:55). For Reference BourdieuBourdieu (1990), social origin and past experience provide a platform for possibilities and responses to career opportunities and obstacles. Through education and mentorship, legal professionals refine repertoires of knowledge that foster familiarity and skill in negotiating opportunities for elevated earnings. Individuals, directed in part by dispositions, thus invest and convert human and social-symbolic capitals to maximize their earnings (Reference BourdieuBourdieu 1990; Reference Lamont and LareauLamont & Lareau 1988).

Across the trilogy of capitals, avocats and notaires may differ in both quality and quantity of stocks. With reference to social capital, avocats accumulate elite networks through corporate clients and international business, whereas notaires are likely to serve individual clients and small businesses in their local communities. Yet in terms of symbolic capital, one might expect notaires to be advantaged through their cultural status within Québec. Reference AbbottAbbott argues that the “cultural structure of professional work” (1981:827) is poignantly important to intraprofessional status. Within Québec society, the notaire has held special legal and cultural significance as the province's first legal profession. Yet my expectation is closer to Reference AbbottAbbott's take on the English legal profession: “The barrister stands over the solicitor because he works in a purely legal context with purely legal concepts; the solicitor links the law to immediate human concerns” (1981:824). Similarly, avocats litigate in court, while notaires are viewed as accessible counsel to the general public, often dealing with more mundane legal matters such as real estate transactions, trusts, and contracts. Finally, in terms of dispositions, the work of avocats is by nature more adversarial, whereas notaires are engaged in a more open and cooperative venture. The former style and structure of legal work is more costly to clients and remunerative for avocats.

Organizational-Structural Model

A third explanation focuses on the impact of organizational structure on earnings. This approach traces how earnings vary across work settings and individuals' placement within work settings. Early versions (Reference Baron and BielbyBaron & Bielby 1984; Reference Hodson and KaufmanHodson & Kaufman 1982) differentiated organizations by their characteristics and also by the degree to which the employment relationship resulted in “good” or “bad” jobs. Jobs with direct monetary value (Reference KallebergKalleberg et al. 2000) as well as nonmonetary features (Reference JencksJencks et al. 1988), such as workplace benefits, autonomy, and variety of tasks, constituted the good jobs within occupational groupings. Recent studies have elaborated organizational differences in work settings, employment relationships within these settings, and their relationship to earnings (Reference Dixon and SeronDixon & Seron 1995; Reference Mueller and McDuffMueller & McDuff 2002; Reference Wallace and KayWallace & Kay 2009).

Most well known is the dual-hemisphere argument proposed by Reference Heinz and LaumannHeinz and Laumann (1982). Heinz and Laumann demarcated two hemispheres of law practice: elite lawyers who represent large corporations, and those who represent individuals. Lawyers within each sector differ systematically in terms of the prestige of the law schools they attended, career histories, differential likelihood of engaging in litigation, different forums of litigation, social and political values, and social networks (Reference Heinz and LaumannHeinz & Laumann 1982). More recently, Reference Heinz and NelsonHeinz, Nelson, and colleagues (2005:35) have contended that the contemporary organization of work is subdivided into smaller, more highly specialized clusters that are less visibly separated by the distinction between corporate and personal client types. Yet increasing differentiation of lawyers' roles has resulted in fortified internal boundaries that are “more well-defined and difficult to cross” (Reference Heinz and NelsonHeinz, Nelson, et al. 2005:317). Organizational type also plays an increasingly strong role in determining lawyers' earnings. In particular, solo practice and government employment have come to pay substantially less than small and medium-sized firms, while the largest firms increasingly offer the most lucrative salaries (Reference Heinz and NelsonHeinz, Nelson, et al. 2005:174).

This model is particularly fitting to the duality of Québec's legal profession. Clearly, a system of billable hours shapes the earnings of avocats working in private practice, while a fee-for-service structure characterizes the earnings of notaires. Notaires typically work in small offices and in general law practice rather than in large firms and in specializations. The clientele of notaires is also more often made up of individuals rather than corporations. In many respects these two professional groups resemble the two hemispheres that Heinz, Nelson, et al. depict as characterizing the Chicago bar. Reference Heinz and NelsonHeinz, Nelson, et al. (2005:318) note that: “Social stratification divides the bar and weakens its coherence—lawyers with differing personal characteristics live in different social worlds and play different roles both in the bar and outside it. Moreover, the growing specialization of lawyers' work is increasingly the separation among those roles.” This image of contrasting worlds applies aptly to the Québec legal profession, with consequences for earnings levels across the two groups.

Earnings of Québec Legal Practitioners

Data

The study is based on data collected through two surveys and in-person interviews with a sample of notaires and avocats. The notaire survey was mailed in November 1998 to a random sample of 1,000 notaires with the cooperation of the CNQ. A stratified simple random sample was selected using the membership records of the CNQ to obtain equal numbers of men and women notaires. The avocat survey was conducted in January 1999 with the cooperation of the BQ. Again, a stratified simple random sample was generated using the membership records, this time, of the BQ. The survey was mailed to 1,000 avocats, with equal numbers of women and men to facilitate gender comparisons. Questionnaires were produced in French and were accompanied by letters of endorsement from the two professional associations. Avocats and notaires received an introductory letter and 28-page questionnaire, and after two weeks received a postcard reminder. A follow-up letter of encouragement together with a second questionnaire was sent to nonrespondents after one month, and a second postcard reminder after another two weeks. These extensive follow-up efforts served to enhance the response rates.

In total, 608 usable surveys were returned in the survey of notaires. A total of 580 surveys were returned in the survey of avocats. Taking into account the number of legal professionals who had departed from law practice and deceased members of the profession, the adjusted rate of response was 62% among notaires and 60% among avocats.

In addition, interviews were conducted with a sample of 20 avocats and 10 notaires in Montréal and surrounding communities during May to July 1999. Participants in the interviews were contacted through snowball sampling techniques, and individuals were selected to represent an array of practice settings. The semi-structured interviews explored four central themes: professional context, career satisfaction, family responsibilities, and dynamics of change in the Québec legal profession. Interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed and lasted between 70 minutes and two and half hours. All but two interviews were conducted in French.

Measures

The variables used in this analysis were grouped into six broad categories: demographic, human capital, symbolic capital, social capital, organizational context, and dispositions. I begin with the measurement of the dependent variable, annual earnings. I then work back through a series of endogenous to exogenous concepts and indicators.

Log of Annual Earnings

The measure of income (log) was respondents' total annual earnings from the practice of law before taxes and other deductions made for 1998. The natural logarithm was used to account for a skewed distribution and reduce the impact of outliers (Reference Aguilera and MasseyAguilera & Massey 2003:697).

Demographics

Respondents were asked to indicate whether they work as a notaire or avocat (notaire=1), their gender (male=1), marital status (married and cohabiting=1), and parental status (parent=1). The treatment of cohabitation as equivalent to marriage is appropriate in the context of Québec society, where the prevalence of cohabitation far exceeds rates elsewhere in North America (Reference KerrKerr et al. 2006; Reference LeBourdais and LaPierre-AdamcykLeBourdais & LaPierre-Adamcyk 2004).Footnote 4 My measure of minority was inclusive of both ethnic/racial groups as well as several other traditionally underrepresented communities within the legal profession. Respondents who self-identified as a member of a minority group by virtue of ethnicity or race, religion, physical disability, language, or sexual orientation were coded as minority status (minority=1).

Human Capital

I also considered individual investment and productivity characteristics emphasized in the human capital perspective (Reference BeckerBecker 1994; Reference Brown and JonesBrown & Jones 2004). Respondents self-reported their overall academic performance in law school on a scale: (1) high A (A+) [90=100%], (2) A [80–89%], (3) high B (B+) [75–79%], (4) B [70–74%], (5) high C [65–69%], (6) C [60–64%], (7) D [50–59%]. Categories were then reverse-coded. Experience was measured as years since admission to the practice of law. Hours worked were measured as hours worked per weekday (multiplied by a factor of 5) plus the total hours worked each weekend.

Symbolic Capital

I used two measures of prestige and reputation to capture the symbolic capital that “tacitly privileges” select legal professionals: law school and area of law. Although law schools have a less attenuated hierarchy of status and prestige in Canada (Reference Stager and ArthursStager & Arthurs 1990) than in the United States (Reference Heinz and LaumannHeinz, Laumann, et al. 1997), distinctions exist. McGill University and Université de Montréal are defined as elite law schools (elite education=1).Footnote 5

Prestige of area of law was the second dimension of symbolic capital. Respondents reported their main area of practice and also assessed each area of law on a 10-point scale of prestige (Reference KayKay & Hagan 1998). Respondents were then assigned a score to their primary area based on their professional group's mean assessment of that area. To make these two sets of prestige values comparable, I standardized them around the mean for each group within the regression analyses. Thus each individual prestige value was measured in standard deviations from the relevant mean.

Social Capital

In this analysis, social capital derived from two sources: connections through private schools, club membership, and language acquisition, on the one hand; and contemporary clientele networks, on the other. Respondents indicated whether they had attended private school during either elementary or secondary schools (private school=1). Respondents also reported whether they were members of any clubs (e.g., social clubs, political party, community organizations, sports clubs, etc.; club membership=1).

Clientele dimensions of social capital took on three forms. First, respondents reported the proportion of time spent representing corporate clients during the past 12 months. They also reported the proportion of their clientele who speak as their first language French, English, and other languages. The language variable measured the percentage of English-speaking clientele. Finally, respondents assessed the degree to which their work involved interaction with clients. Response categories ranged from (1) “a great deal,” (2) “considerable,” (3) “some,” and (4) “little,” to (5) “none” (reverse-coded).

Dispositions

Finally, measures of dispositions used in this study tapped three core ideas: drive, trust, and ambitions. Drive encompassed two dimensions: individualism and competition. Individualism was measured by four Likert-style items ranging from “strongly disagree” (coded 1) to “strongly agree” (coded 5). The items were adapted from research on locus of control (Reference LevensonLevenson 1973; Reference WallaceWallace 2001). Statements included: “I am responsible for my own success,”“I can do just about anything I really set my mind to,”“My misfortunes are the result of mistakes I have made” (reverse-coded), and “I am responsible for my failures” (reverse-coded) (alpha reliability=.79). Competitiveness was adapted from research on hierarchic self-interest (Reference HaganHagan et al. 1999). The measure was composed of two statements: “My ambition is always to be better than average” and “I am only satisfied when my performance is above average” (alpha reliability=.71).

Trust embodied a general interpersonal trust and a trust in the justice system. General trust was measured using two items derived from Reference PaxtonPaxton (1999). Statements included “Most people can be trusted” and “Generally speaking, you can't be too careful in dealing with people” (alpha reliability=.67). Judicial trust was measured with a single-item indicator: “On average, our justice system is fair.” Respondents rated these statements with Likert-style responses ranging from “strongly disagree” (coded 1) to “strongly agree” (coded 5).

Finally, ambitions were revealed through two contrasting types of career aspirations: traditional status goals and legal activist goals. These concepts were designed and elaborated from the core ideas of Reference KayKay and Hagan's (1998) study of firm cultures. Avocats and notaires were asked to assess the importance of achieving specific goals for professional advancement. Each goal was ranked on a scale from 1 (not important) to 4 (very important). Traditional status aspirations included seniority in a firm, seniority in a corporate legal department, a strong solo practice, a strong notaire office, leader in a corporation, and financial rewards (alpha reliability=.82). Legal activist goals included leadership in agencies concerned with public administration, politics, community institutions, legal education, law reform, and service to disadvantaged groups in society (alpha reliability=.81).

Organizational-Structural Context

Three aspects of organizational context were incorporated in this study: organizational size, sector of practice, and region. Organizational size was coded into four dummy variables: solo practice, small (two to 10 legal professionals), mid-sized (11–50), and large private firms (50+) (see Reference NelsonNelson 1988; Reference Robson and WallaceRobson & Wallace 2001). This coding captured avocats working in law firms as well as notaires working with other notaires in shared offices. It should be noted that notaires did not speak of firms or partnership, per se; rather they described offices of notaires, keeping independent financial books but sharing administrative personnel and property leases. The sectors of practice were coded as private practice, corporate, and government (Reference Dixon and SeronDixon & Seron 1995). The region (urban=1) in which avocats work was coded as urban (including Montréal and Québec City) in comparison with other regions.

Results

Two Contrasting Worlds

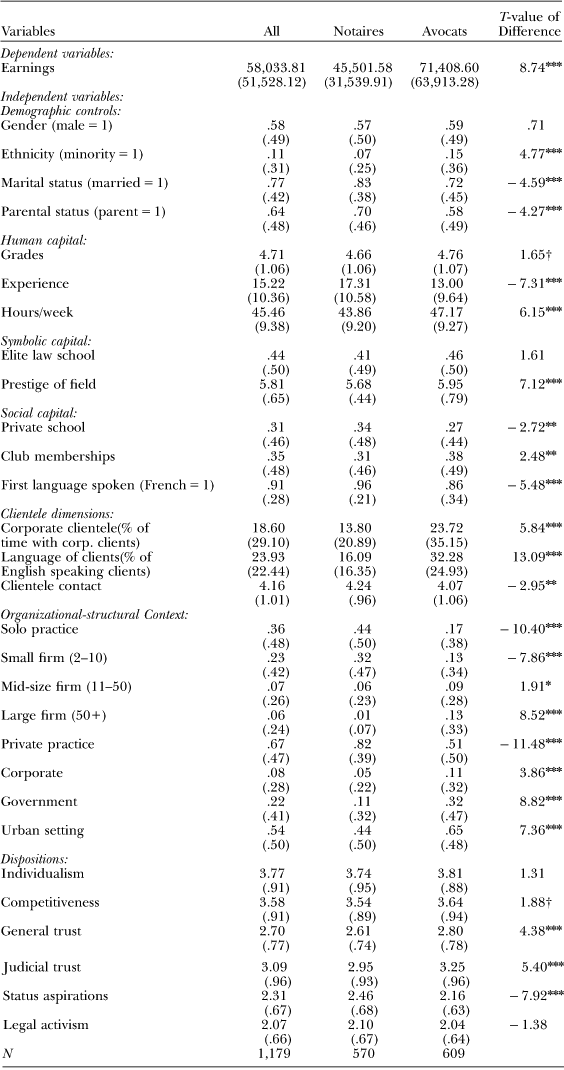

It is useful to briefly examine the contrasting profiles and legal worlds inhabited by these two professional groups (see Table 1). Most striking perhaps is the enormous gap in pay, with notaires averaging just $45,502 annually compared with an average income of $71,409 among avocats (t-test=8.74, p<0.001). The two types of legal practitioners differed in several other important ways.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Legal Professionals in Québec

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. All numbers are rounded to two decimal places.

† p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 (two-tailed tests)

Notaires averaged 17 years' experience, compared with 13 years for avocats (t-test=−7.31, p<0.001). Notaires were more likely to be married or cohabiting (83 percent compared with 72 percent, t-test=−4.59, p<0.001) and to be parents (70 percent compared with 58 percent, t-test=−4.27, p<0.001). Diversity was also higher among avocats. Fifteen percent of avocats identified as minority group members, compared with only 7 percent of notaires (t-test=4.77, p<0.001). These differences likely reflected declining enrollments in notarial law programs and the influx of new graduates to the bar (avocats), together with growing ethnic diversity among recent law school cohorts.

In terms of human capital, avocats on average received only slightly higher grades in law school (t-test=1.65, p<0.10). However, avocats worked on average significantly longer hours than notaires (47 hours per week compared with 44 hours, t-test=6.15, p<0.001). In addition, avocats were slightly more often McGill and Montréal graduates, though it is noteworthy that McGill (an English university) does not offer a notarial program.

When it came to social capital, notaires were significantly more likely to have attended private school (34 percent compared with 27 percent among avocats, t-test=−2.72, p<0.01), while avocats were more likely to hold club memberships (38 percent compared with 31 percent among notaires, t-test=2.48, p<0.01). Notaires were more likely to be francophones: 96 percent of notaires spoke French as their first language, while 86 percent of avocats spoke French as their first language. Among nonfrancophone avocats, most were English-speaking (70 percent), while nonfrancophone notaires were more evenly divided among English (48 percent) and other languages.Footnote 6

There were also important distinctions in terms of clientele responsibilities. Avocats spent on average 24 percent of their time representing corporate clients, compared with 14 percent among notaires (t-test=5.84, p<0.001). Although the vast majority of clients spoke French as their first language (86 percent among clients of notaires and 72 percent among clients of avocats), avocats were more likely to serve anglophones: 32 percent of their clients were anglophones, compared with, on average, 16 percent of notaires' clients (t-test=13.09, p<0.001). However, notaires had, on average, more contact than avocats with their clients (t-test=−2.95, p<0.01).

The dispositional differences between the two professional streams were more complex. Notaires and avocats were similarly individualistic, but avocats appeared slightly more competitive than their notaire counterparts (t-test=1.88, p<0.10). Avocats reported higher levels of trust toward the justice system and people generally (p<0.001). Notaires and avocats were similarly inclined toward legal activism, but interestingly traditional status aspirations were more pronounced among notaires (t-test=−7.92, p<0.001).

The organizational contexts of notaires and avocats were much more clearly demarcated. The overwhelming majority of notaires worked in private practice (82 percent), while only half of avocats worked in private practice (51 percent). Meanwhile, avocats were more likely to work in government (32 percent) compared with notaires (11 percent). In addition, a larger percentage of avocats (11 percent) than notaires (5 percent) worked in corporate settings (p<0.001 for all practice setting differences). Within private practice, the largest percentage of notaires worked as solo practitioners (44 percent compared with only 17 percent of avocats, p<0.001). The next largest percentage of notaires worked in small offices of two to 10 notaires (32 percent), while few worked in mid-sized offices of 11 to 50 legal professionals (6 percent), and fewer still in large offices of more than 50 individuals (1 percent). Notaires located in these larger offices were likely working either within law firms (of primarily avocats) or other firms (such as accountancy or other business firms). By contrast, avocats were distributed in a curvilinear fashion across firm sizes, with 13 percent working in small firms (10 or fewer), 9 percent in mid-sized firms (11–50), and 13 percent in the large firms (50+ avocats).Footnote 7

There were even notable differences in the geographic location of these two spheres of legal professionals. Consistent with prior reports (Reference MorierMorier 1997), notaires were significantly more likely to work in rural areas. Sixty-five percent of avocats worked in the two major cities of Québec and Montréal, while only 44 percent of notaires practiced law in these metropolises.

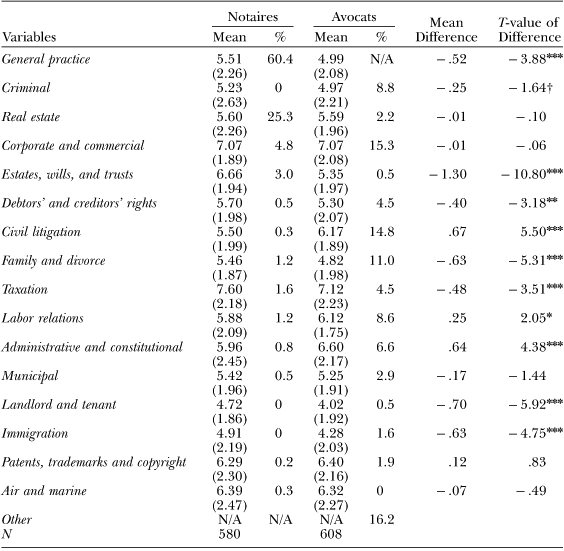

Of particular interest to this study were the areas of law practiced as jurisdictional turf zones. Differences emerged in terms of both prestige ranking and distribution of practitioners across areas. As a first step, I examined the mean average prestige scores assigned by notaires and avocats, respectively, to the 16 areas of law (see Table 2). Some similarities existed. Both notaires and avocats scored the list by placing taxation and corporate and commercial law highest and landlord and tenant and immigration law lowest. Yet striking variations also surfaced. For example, avocats assigned, on average, higher prestige scores to areas commonly in their jurisdiction, such as civil litigation, labor relations, and constitutional law. Meanwhile, notaires awarded, on average, higher prestige scores to areas frequently in their domain: general practice and estates, wills, and trusts (as well as debtors' and creditors' rights, family law, landlord and tenant law, and immigration law).

Table 2. Prestige of Areas of Law Within Québec Legal Practice

Note: Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. All numbers are rounded to two decimal places.

† p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 (two-tailed tests)

There were also sharp contrasts between the areas of law practiced by each group. Most notably, 60 percent of notaires identified general practice as their primary area, while the largest proportions of avocats practiced primarily corporate commercial (15 percent) and civil litigation (15 percent), followed by family/divorce law (11 percent) and criminal law (9 percent). Although the Code Civil specifies exclusive jurisdictions of law, overlap exists. For example, 15 percent of avocats and 5 percent of notaires identified corporate commercial law as their main area of work. Furthermore, both avocats and notaires, in various proportions, each reported as their main practice areas real estate, taxation, family, labor, wills and trusts, patents and trademarks, debtors' and creditors' rights, municipal law, and constitutional law. The overlap would perhaps be even greater had the question been asked about secondary and tertiary areas of law practice.

Unpacking the Earnings Gap

My estimation strategy was to regress the independent variables on levels of earnings attainment on a combined sample of notaires and avocats. First, I used a series of OLS regression steps to assess the contributions of human capital, social-symbolic capital, and structural-organizational context to the earnings of legal professionals. The logical sequencing of independent covariates led me to introduce demographic and human and symbolic capital variables as an early baseline, followed by social capital, then structural-organizational context, and last legal professionals' dispositional characteristics.Footnote 8 Next, I separated out notaires and avocats to compare the different dimensions that explained the sizeable gap in earnings between these professional groups.

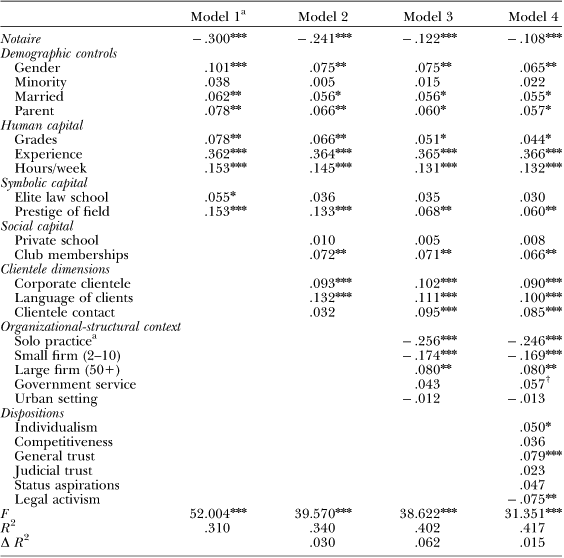

Table 3 examines the earnings gap through reduced form and structural OLS regression equations. The baseline model revealed that, consistent with earlier studies, males, legal professionals who are married, and parents (Reference Dixon and SeronDixon & Seron 1995; Reference Kay and HaganKay & Hagan 1995; Reference Robson and WallaceRobson & Wallace 2001) garnered higher incomes. Inconsistent with prior studies (Reference Huffman and CohenHuffman & Cohen 2004; Reference ReidReid 1998), minorities appeared to make slight income gains; however, this difference was rendered statistically insignificant when measures of symbolic capital (elite law school and area prestige) were incorporated. Recall that minority status included self-identification across several groups. The largest of these was anglophones, a group in the Québec context that was perhaps more likely to attend elite law schools, enter law as avocats, and specialize in prestigious areas with connections to out-of-province and international business.

Table 3. Structural and Reduced Form OLS Equations for Earnings (Logged) of Québec Legal Professionals

a Standardized beta coefficients displayed.

† p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 (two-tailed tests)

Three human capital variables significantly increased income: academic grades, years of experience, and hours worked per week. Most impressive was the role that practice experience played in generating earnings (β=0.362, p<0.001). This is consistent with human capital arguments that the labor market and organizational experiences are vital to the development of knowledge and skills. Yet the failure of human capital theory to explain the fuller variation in incomes across professional groups was evident. Symbolic capital further enhanced earnings. Graduation from an elite law school (β=0.055, p<0.05) and work engaged in prestigious areas of law (β=0.153, p<0.001) also increased earnings. Avocats were more likely to hold these symbolic resources as elite law school graduates working in prestigious areas of law; they also held a human capital edge through investment in longer weekly hours of work.

Social capital further elevated earnings (see model 2 in Table 3), though it was contemporary club memberships, rather than private school attendance, that contributed to higher earnings. This is perhaps not surprising for two reasons. First, club memberships provide new and attractive opportunities to recruit lucrative clients to law practice, whereas ties from private school may be more dated connections and hence brittle social capital. Furthermore, private school was not defined more precisely in this study than having attended a private school during elementary or secondary school. There is considerable variation between the truly elite private schools in Québec with costly tuitions and smaller, less expensive private schools operated as affiliates of religious denominations. Another interesting dimension of social capital, clientele relations, is introduced in model 2. Legal professionals who spent a greater proportion of their time representing corporate clients and English-speaking clientele made significant income gains. The English-speaking clientele variable likely taps corporate business drawn from the United States and provinces outside Québec—law practice “reaches” more characteristic of avocats, particularly those employed in large law firms.

The organizational-structural model of earnings is introduced in model 3. Work context mediated symbolic and social capitals in important ways. The effect of prestigious areas of law on earnings was dampened with the introduction of organizational size, sector, and region. Firm size accounted for considerable variation in earnings. Large law firms offered the highest earnings advantage compared with other practice settings. Meanwhile, solo practice and small firms yielded reduced earnings compared with mid-sized firms. This organizational divide is typical of the two professional groups. Law firms primarily, almost exclusively, hire avocats, while notaires typically work as solo practitioners and in offices with a few colleagues. The introduction of firm size variables also revealed the significant impact of client contact on earnings, suggesting that the influence of client contact is suppressed by work context variables, particularly firm size. The nature of small firms and solo practice likely offer greater opportunities for regular client contact, but it is the legal practitioners working in large law firms with significant client contact that incur the greatest income gains.

A final layer of social-symbolic capital theory is introduced in model 4, where the contribution of dispositions to earnings is revealed. Individualism, as a form of motivational drive, fueled the attainment of higher earnings (β=0.050, p<0.05). Individualism, a sense of responsibility for one's successes and confidence to succeed, was of greater import to earnings than simply having a will to compete with others. Strong interpersonal trust also enhanced earnings (β=0.079, p<0.001), possibly as a byproduct of active social capital that cultivated new and sustained client representation (Reference KayKay & Hagan 2003). Recall that avocats reported higher levels of both social capital and trust. And finally, the ambitions held by legal professionals offer food for thought. Even when controlling for human capital, social-symbolic capitals, and organizational context, legal professionals who held dear their ambitions to lead through unconventional practice goals incurred a sizeable penalty to their earnings (β=−0.075, p<0.01). That said, notaires tended to hold status or conventional-oriented goals (this inclination perhaps reflects the reduced power of notaires to shape law and social change).

The analysis thus far assumes that there are direct effects of demographics, human and social-symbolic capitals, and structural-organizational context, but that the effects of these variables are the same for notaires and avocats. That is, I have assumed that the variables have an additive, rather than an interactive, effect on the earnings of legal professionals. Yet because none of these three models fully explains the notaire-avocat gap in earnings, it is important to examine the income determination processes separately for notaires and avocats.

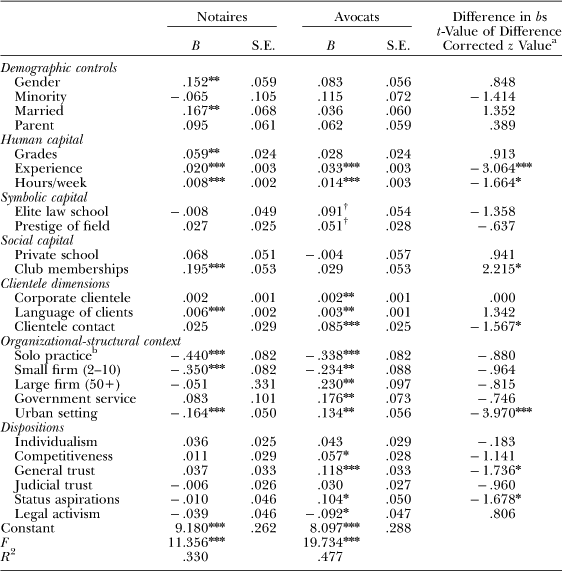

This analysis is presented in Table 4. Some intriguing professional boundary differences emerged. For example, demographic factors appeared more salient to the earnings of notaires, with those male and married making gains on the income ladder. In addition, a number of factors associated with the three competing theoretical perspectives offered differential rewards to each professional group. For instance, years of experience and hours worked per week, two human capital components, both yielded significantly greater income rewards to avocats than to notaires (z=−3.064, p<0.001 and z=−1.664, p<0.05, respectively).Footnote 9 With reference to social-symbolic capital theory, the prestige of one's area of law did not have a significant impact on the earnings of either notaires or avocats in these separated analyses. I calculated a series of reduced models, revealing that initially the prestige of area practiced held statistical significance for both notaires and avocats, net of demographics, human capital, social-symbolic capitals, and clientele dimensions. Prestige of area only fell below statistical significance with the inclusion of organizational context variables (for avocats, prestige of area retained significance at a borderline level: p<0.10, two-tailed). In other words, organizational context mediates the relationship between areas of law and earnings; more prestigious areas of law lead to employment in large law firms, which in turn deliver higher earnings. That prestige of area retains an impact on the earnings of avocats is expected, given the distinct hierarchy of areas of law documented in the literature on lawyers (Reference Heinz and NelsonHeinz, Nelson, et al. 2005; Reference SandefurSandefur 2001) as well as correlation analyses of the present data that revealed that notaires generally practice in less prestigious areas of law than do avocats (r=−0.203, p<0.001, two-tailed). Moreover, areas of law are perhaps less relevant to notarial earnings, given that more than 60 percent of notaires identified general practice as their main area of legal work.

Table 4. OLS Estimates of Earnings (Logged) of Notaires and Avocats (N=1,169)

† p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 (two-tailed tests)

a Compares differences in coefficients of notaires and avocats (one-tailed tests).

b Reference category is firms/offices of 11 to 49 avocats/notaires.

Further differences emerged among social-symbolic capitals. For example, although notaires were more likely to spend time one-on-one with clients, it was avocats who received a substantial earnings advantage through client contact (z=−1.567, p<0.05). Yet club memberships offered income rewards to notaires but not avocats (z=2.215, p<0.05). This finding resonates with interviews conducted with several notaires in the study. These notaires commented on the importance of community involvement, particularly for notaires working in smaller cities and villages where the individual notaire is recognized as both legal consult and an integral member of the community. One notaire, who was president of the village recreational committee, soccer coach, committee member for the local Fête Nationale celebration, and president of the local minor hockey association, explained:

I am not strong at marketing. I don't like those that are, the type that pass out business cards. It's rare that I do that. I don't need to routinely identify myself as a notaire. My first goal is to involve myself in my community… . It gives me the chance to meet people, to make myself known. It's a way to advance my law practice. … It's always the same when one gets involved in local community events: people come to see you are efficient and dedicated, and they seek out your legal services.

(male notaire, in an office with one other notaire, Bas Saint-Laurent region)Organizational-structural context also shaped earnings among notaires and avocats, with various nuances. Solo practice and small firms/offices held financial struggles for notaires and avocats alike, while avocats garnered higher incomes in large law firms compared with their counterparts in smaller firms. Even for notaires working within large law firms, marginalization occurred. As one avocate acknowledged during her interview:

I think there have been some changes—lawyers are doing more things. I think there is a perception that there is no future in le notariat. With the economic crisis, real estate transactions have declined dramatically, and these factors affected many notaires. I am certain that at the level of salary, it is horrible. At our law firm, we work with notaires on large commercial real estate transactions. In another large law firm, of about the same size and revenues as our firm, there was a partner who was looking for a notaire with at least seven years of experience—and what he offered him as salary was half what the market offers. (female avocate, large law firm, Montréal)

Avocats also made income gains in government service compared with corporate settings and private law practice generally. Interestingly, a lower percentage of avocats in Québec worked in private practice (51 percent) compared with lawyers in the neighboring province of Ontario (71 percent, see Reference KayKay et al. 2004:27) and the United States (67 percent, see Reference DinovitzerDinovitzer et al. 2004:27). By contrast, the vast majority of notaires worked in private practice (82 percent) and there were no statistically significant differences between private practice, corporate, and government settings for notaire earnings. Geographic context did, however, have a sizeable impact on earnings for both notaires and avocats. Avocats made significant income gains working in Montréal and Québec City, while notaires who elected to work in Québec's two major cities suffered a decline in earnings relative to their colleagues in smaller cities and towns (z=−3.970, p<0.001). Given that notaires have reduced access to large firms that serve corporate clients and that cities generally have greater competition among legal practitioners for clients, this finding likely reflects distinct markets for each groups' services. The U.S. literature on the legal profession suggests that urban markets are more competitive than rural legal markets and that competition in urban areas dampens earnings among those who serve individuals more so than those who serve corporate clients (Reference CarlinCarlin 1994; Reference Heinz and NelsonHeinz, Nelson, et al. 1995; Reference SeronSeron 1996; Reference Van HoyVan Hoy 1997). It is possible that different market dynamics, tied both to jurisdictional claims and organizational structure, drive a sizeable portion of the income disparity.

Among dispositional factors, trust made a notable difference to the earnings of avocats over notaires. General interpersonal trust yielded higher earnings among avocats, but not notaires (z=−1.736, p<0.05). The causal direction may be reversed here. After all, avocats have good reason to be trusting. They not only enjoy dramatically higher salaries, on average; avocats also receive greater returns for their parallel investments in experience and hours (human capital), clientele responsibilities (social capital), and organizational context. More telling perhaps is that traditional status aspirations benefited avocats in this analysis but yielded little by way of monetary returns to notaires (z=−1.678, p<0.05).

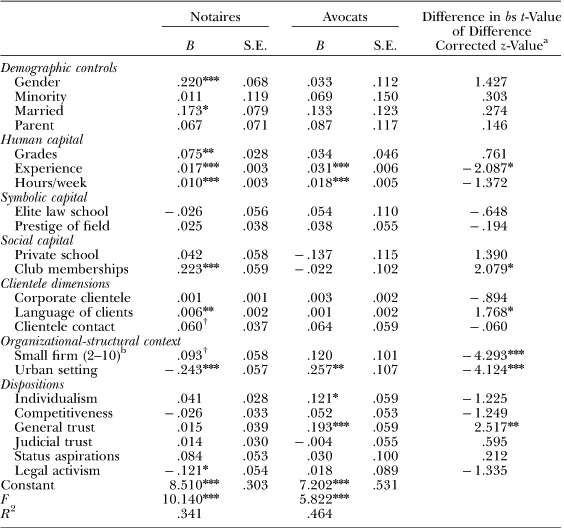

At the heart of this story are the frontiers where jurisdictional skirmishes and tough competition for clientele are prevalent. Reference AbbottAbbott (1986:187) suggests that jurisdictional invasions “should occur first in peripheral areas—peripheral in terms of client status, of economic reward, and possibly in terms of strength of legal jurisdiction.” In the context of Québec legal practice, the domain of contestation perhaps lies at the intersection of jurisdictional fields and organizational structure. Specifically, notaires are very much in competition with solo and small-firm avocats for often the same pool of clients and offering similar legal services. Do notaires and avocats working in these similar organizational structures, competing for the same clientele base, achieve equal returns for their stocks of human, social-symbolic, and dispositional capitals? Table 5 introduces this more refined analysis among solo and small-firm practitioners. The results of this study showed that avocats received greater returns to their human capital investments in years of experience (z=−2.087, p<0.05). However, social capitals of club memberships (z=2.079, p<0.05) and service of francophone clients (z=1.768, p<0.05) were important to earnings among solo and small office notaires. The real erosion of earnings took place in urban settings, where notaires incurred deflated salaries while avocats saw their incomes vastly enhanced (z=−4.124, p<0.001). Perhaps not coincidentally, avocats expressed greater generalized trust, which brought its own financial rewards, while general trust offered no significant financial gain to notaires (z=2.517, p<0.01).

Table 5. OLS Estimates of Earnings (Logged) of Notaires and Avocats in Solo Offices and Small Firms (N=630)

† p<0.10; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001 (two-tailed tests)

a Compares differences in coefficients of notaires and avocats (one-tailed tests).

b Reference category is solo offices of avocats/notaires.

Jurisdictional disruption was clearly linked to deflated revenues by notaires interviewed. These notaires spoke about financial struggles and poaching of clients by both law firm avocats and banking institutions. As one notaire working in a small town observed:

I believe that the debate aroused by Bill 443 has enabled us to determine that avocats want to do it all (particularly separations and real estate) and leave only the lower-paying fields of practice to notaires. In addition, I believe that financial institutions will recruit staff in huge numbers to be able to offer every service, for example, death settlements performed by notaires and not by administrative personnel with only some knowledge of law. At the Université Laval, the number of graduates in business administration will grow substantially over the next few years. By way of the services offered to bank clients, etc … they come directly to look for work done by notaires. When I see the commercials with the lady who works for the [name of bank] and I hear what she says, it bears a strange resemblance to what I say myself as a notaire.

(female notaire, shared office, rural region, Abitibi-Témiscamingue region)During interviews, conversation turned quickly to the difficult struggles facing notaires as solo practitioners and among those working in small offices. Notaires recognized their diminished wages and yearned “to be compensated based on the value of our work,”“to be fairly compensated,” and as one notaire caustically remarked: “We're living in the ‘Walmart’ era—fast service for a low fee.” Another notaire, eight years out of law school and working in a shared office, reflected on his decision to enter le notariat:

It is very difficult because in the case of earnings, it is just not what it used to be. At the time that I started law school, it was not at all the situation it is now. Certainly, after eight years of practice, these are not things that make us profoundly unhappy every day, but it is a reality. So, if I could turn back time, maybe I would do something that would offer more stable remuneration, I would say even higher income. Certainly, I would prefer a greater security with workplace benefits because when you work independently, you have to pay for everything. These costs lower your salary. I love my work, but we are in a system of tough competition where it [is] much more difficult than even just a few years ago—that's for sure.

(male notaire, shared office, rural setting Richelieu region)In both the interviews and surveys, notaires expressed the need “to protect our traditional areas of law, especially real estate” and “to guard our existing areas of practice before they erode beneath us.” Others spoke of expanding jurisdictional terrain. These notaires declared an exigency “to keep and increase our market share” and “to better position ourselves, prepared to seize new areas of practice.” Fundamental to “protected hunting grounds” and expansion of jurisdictions was a deeply held desire to ensure that notaires were not displaced from the legal profession itself. Two notaires explained: “We must fight to retain our rightful place within the legal profession,” and “We must conserve our areas of knowledge in the face of numerous infringing professions that seek to make us disappear.”

Notaires also spoke frequently of a growing urgency to “regroup and help each other,”“to develop solidarity among notaires and promote unity,” and “to organize in order to completely control real estate and banking law.” For some it was imperative “to open the minds of fellow notaires to any association with another professional body that would enable us to combat external threats more forcefully.” Several suggested that a viable strategy was to “unionize and form our own professional association that represents the interests of notaires,” and that “only through unionization can notaires have the power to defend our practice domains.” Solidarity appeared vital to jurisdictional defense as well as to building more remunerative legal careers. As two notaires commented: “As notaires we must build solidarity and confront a competition that is growing more and more fierce,” and “Only through solidarity, we can rebuild the value of notarial services.” However, solidarity was not always identified with the professional association, the CNQ. It was not uncommon for notaires to express disappointment and frustration with the CNQ. As the following notaire recounted:

In the coming years, there will be fewer notaires, our presence will be weaker, and we will no longer be indispensable. We will, therefore, have to recycle ourselves into other jobs or perform other legal work; transaction insurance is coming. A profession without any glamour or pride; it is doomed to failure. A quick look at the number of resignations per year is all it takes to confirm this view. La Chambre des notaires is too preoccupied with protecting its clients to be concerned about protecting its members and soon there will be no members left!

(male notaire, solo practitioner, Montréal)Another notaire, also working as a solo practitioner in Montréal, denounced the CNQ:

La Chambre seems to protect its existence and the work of its employees. It has allowed pride in this profession to fall by the wayside by taking no action on rates or against notaires who engage in questionable practices. I see no future for notaires. Soon we will become the employees of law firms.

(male notaire, solo practitioner, Montréal)Yet the CNQ itself acknowledged nearly 40 years ago the difficult challenges posed by intra- and interprofessional competition, particularly as manifested through the expansion and dilution of notarial work. In an excerpt reminiscent of Reference AbbottAbbott's contention that professional prestige is rooted in the purity of legal practice (1981), the CNQ proclaimed:

We are aware of the compensation structures that drive many notaires to engage in a multitude of extra-legal or paralegal activities in which they compete directly with other professions (for example, insurance, real estate brokerage, etc.). When he engages in these activities, the notaire is no longer a jurist, and the more he diversifies, the less he remains one.

By straying farther from his field of practice, the notaire risks losing a clear idea of this cultural model. Then the model loses its coherence, its borders become blurred, and the profession is taken down a few steps on the social ladder. The main consequence of this weakening of the cultural model, therefore, would appear to be a loss of prestige for the profession. (La Chambre des notaires du Québec 1972:31)

Discussion and Conclusion

Intraprofessional competition, played out through jurisdictional disturbances, makes its presence transparent in the accumulation and conversion of capitals available to each professional group. By way of accumulation, it is the avocats who hold, on average, higher levels of human and social-symbolic capitals and often work in more lucrative organizational contexts (i.e., large law firms). However, the earnings gap between notaires and avocats is not fully explained by notaires' lower levels of human and social-symbolic capitals or their tendency toward solo and small office practices. There remains a residual negative effect of practicing law as a notaire. This lingering penalty is rooted, in large part, through the lower “returns” notaires receive on their levels of human and social-symbolic capitals and across practice settings. In other words, notaires and avocats are not only equipped with differential stocks of capitals, but the conversion rates also differ in important ways. The defining characteristic of capital—whether human, social, or symbolic—is its fungibility, the idea that it may be converted into something of value, such as earnings, prestige, or power (Reference Aguilera and MasseyAguilera & Massey 2003). The findings of this study clearly demonstrate the unique and profitable returns of investment in social-symbolic capital, over and beyond investment in human capital, and taking into account variation across organizational context. Yet it is the avocats who receive greater exchange on parallel investments. These disparities are most pronounced in professional arenas where jurisdictional friction heats up: among notaires and avocats working as solo practitioners and in small firms/offices within intensely competitive urban locales.

Furthermore, the mechanisms generating earnings appear to differ across the professional chasm that separates notaires and avocats. To a large extent, the earnings of avocats are better predicted using conventional socioeconomic theories of earnings attainment.Footnote 10 In the case of notaires, a unique set of factors appears salient: human and social capitals (club memberships and involvement in local community), demographics, and organizational context (solo practice in small towns)—each provides a promising, if partial, explanation of the variation in notaires' earnings.

Several avenues of investigation may shed new light on the earnings gap (and other sources of disparity) across professional divides. One direction is to further refine an understanding of social capital's fabric as it relates to professional groupings. For example, networks within and across professional settings (such as law firms and corporate business) may be salient to avocats as brokers within larger organizational settings; while for notaires, the majority of whom work in solo practice or in offices shared with fewer than 10 notaires, the social networks of value may be more expansive in terms of local community ties and individual clientele networks.

Several other conceptual linkages merit further study. First, both human and social capitals serve as reliable predictors of earnings levels (Reference Sagas and CunninghamSagas & Cunningham 2004), and the interaction of social and human capital is a logical and significant dynamic: Those with strong human capital (e.g., education, training, and work experience) tend to have robust social capital (e.g., larger and more diverse networks and contacts with enhanced human capital; Reference Lin and LinLin 2001). Second, human capital may be closely tied to the symbolic side of social capital. For example, clients may observe the quality of the firm's human capital stocks (e.g., talented and skilled lawyers) only after their business relationship is well advanced. Hence, clients depend upon past experiences and the law firm's reputation to determine the fees they are willing to pay (with direct consequences for the earnings of legal professionals; Reference Morrison and WilhelmMorrison & Wilhelm 2004:1683). Third, different organizational contexts of law practice may foster realms of social capital. For example, Reference GranovetterGranovetter's (1995) analysis of social capital shows that labor markets are embedded in multiple social relations that lead to differential access to resources of power and information that in turn yield income advantages. Finally, even persuasive arguments of the import of organizational context admit that individual factors, including human capital and social resources, play an active role in earnings determination. For example, Reference Heinz and NelsonHeinz, Nelson, and colleagues (2005:168) reveal that while the types of clients a lawyer serves and the type of organization in which he or she works are increasingly important to the determination of incomes, sizeable income inequality exists among lawyers engaged in broadly similar jobs—leaving individual factors considerable latitude to shape earnings outcomes. The present study testifies to the explanatory potential gained through an integrated approach of sociological and economic models of earnings determination. An integrated approach also draws attention to the diverse composition and tactical conversion of various forms of capital (human, social, symbolic) in the growth of financial capital among competing legal professionals.

Yet further factors that influence the earnings of these professional groups remain a puzzle. The distinctions dividing these two spheres of law practice provide only a partial account of the earnings gap. These regression analyses suggest there is more to the story. Notaires, once heralded as “defenders of the Code Civil,” no longer stand at the professional helm to steer law reform and expand jurisdictions of practice. Research needs to explore whether further devaluation of the work of notaires has transpired in recent decades. Are lower earnings a reflection of legal jurisdictions, or less adversarial methods of conflict resolution, or is it the case that the work of notaires is somehow more administrative and characterized by a lower complexity of legal problems? For similar services, do notaires charge less? Do individuals simply expect to pay less for the services of a notaire?

Given the shortfall of earnings, why do law students choose to become notaires? The attraction may be the independence offered by notarial practice, greater control over hours and less pressure to “bill” or be monitored as is the case in many large law firms, a desire to live in regions outside expensive large urban centers, and a commitment to nonadversarial law practice. A further attraction of notarial law practice is possibly reputation. The profession has succeeded in maintaining its noble status and public approval. Compared to all other professions in Québec, notaires have among the highest public opinion ratings, with 90 percent of those polled expressing confidence and trust in notaires (see http://www.cdnq.org/fr/professionNotaire/jeunesse/html/quelques_chiffres.html [accessed 1 July 2009]). The public perception of notaires is surely more favorable than that of avocats. The popularity of le notariat may have important implications. Reference AbbottAbbott, for example, has emphasized the importance of cultural preferences, specifically public opinion, in the determination of professional boundaries and status distinctions (1988:164). Does the public approval of notaires translate into more satisfying and intrinsically rewarding careers for notaires, lower earnings aside? Will notarial law practice continue to attract law students, or will le notariat be outpaced by increasing numbers of avocats?

This study encourages scholars of the legal profession to think in new ways about professional monopolies, intraprofessional competition, the diversity of capital resources at play within legal careers, and the value of comparative work for an understanding of legal cultures. Perhaps competing subprofessions are able to reach an “uneasy truce” (Reference AbbottAbbott 1988:25), each with its own home turf, shared domains of law and clientele, and even collaboration through employment within common organizations (e.g., law firms, government, and private industry). The trend toward multidisciplinary bureaucracies (Reference NnonaNnona 2006) makes the professional workplace contest for jurisdiction “an increasingly important part of the overall competition for control of work” (Reference AbbottAbbott 1988:153). This study also holds broader implications for the study of legal professions within “mixed jurisdictions,” where systems of both civil and common law “have come together into a living community” (Reference DainowDainow 1967:434). Can paired legal professions coexist harmoniously, and when do disputes over jurisdiction, governance, and social and legal influence serve to undermine the economic prosperity, and even survival, of one professional group?