Introduction

It has been observed clinically and empirically that a proportion of people receiving psychological therapy experience a ‘sudden gain’ during treatment, in which their symptoms improve rapidly between two consecutive therapy sessions and stabilise thereafter, defined and first reported by Tang and DeRubeis (Reference Tang and DeRubeis1999) in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for depression. They found that up to 50% of the overall response to therapy could be attributed to a sudden gain between consecutive sessions. Further studies also found sudden gains to be associated with better treatment outcomes in CBT for depression (Abel et al., Reference Abel, Hayes, Henley and Kuyken2016; Busch et al., Reference Busch, Kanter, Landes and Kohlenberg2006; Tang et al., Reference Tang, DeRubeis, Beberman and Pham2005), with some evidence that this advantage is maintained at 6- and 18-month follow-up (Tang and DeRubeis, Reference Tang and DeRubeis1999). Studies by Tang et al. (Reference Tang, DeRubeis, Hollon, Amsterdam and Shelton2007) and Abel et al. (Reference Abel, Hayes, Henley and Kuyken2016) also provide evidence that sudden gains were associated with lower rates of depression at follow-up.

Sudden gains have been observed in other therapies for depression including supportive-expressive psychotherapy (Tang et al., Reference Tang, Luborsky and Andrusyna2002) and behavioural activation (Masterson et al. Reference Masterson, Ekers, Gilbody, Richards, Toner-Clewes and McMillian2014). Stiles et al. (Reference Stiles, Leach, Barkham, Lucock, Iveson, Shapiro, Iveson and Hardy2003) and Lutz et al. (Reference Lutz, Ehrlich, Rubel, Hallwachs, Röttger, Jorasz, Mocanu, Vocks, Schulte and Tschitsaz-Stucki2013) reported sudden gains across a range of disorders and therapies in routine out-patient psychotherapy. A few studies have looked at the phenomenon of sudden gains in CBT for anxiety disorders, including social anxiety (Bohn et al., Reference Bohn, Aderka, Schreiber, Stangier and Hofmann2013; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, Schulz, Meuret, Moscovitch and Suvak2006), internet-based CBT for severe health anxiety (Hedman et al., Reference Hedman, Lekander, Ljótsson, Lindefors, Rück, Hofmann, Andersson, Andersson and Schulz2014), obsessive compulsive disorder (Aderka et al., Reference Aderka, Anholt, van Balkom, Smit, Hermesh and van Oppen2012a) and therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Aderka et al., Reference Aderka, Appelbaum-Namdar, Shafran and Gilboa-Schechtman2011; Stines Doane et al., Reference Stines Doane, Feeny and Zoellner2010). However, few studies have investigated sudden gains in the treatment of panic disorder. Clerkin et al. (Reference Clerkin, Teachman and Smith-Janik2008) reported that sudden gains which occurred after session 2 of group-based CBT for panic disorder predicted overall symptom reduction at treatment termination and were associated with changes in cognitive biases at the end of treatment. Nogueira-Arjona et al. (Reference Nogueira-Arjona, Santacana, Montoro, Rosado, Guillamat, Vallès and Fullana2017) also found sudden gains in patients receiving group CBT treatment for panic disorder and these were associated with lower levels of panic severity and functional impairment at the end of treatment and 6-month follow up.

A meta-analysis by Aderka et al. (Reference Aderka, Nickerson, Böe and Hofmann2012b) concluded that sudden gains were associated with post-treatment and long-term improvements in both depression and anxiety and a more recent meta-analysis of 50 studies across a range of treatments, disorders and settings confirmed this finding, with larger effect sizes for sudden gains in anxiety disorders and depression compared with other disorders (Shalom and Aderka, Reference Shalom and Aderka2020). They found that pre-treatment severity did not significantly predict the effects of sudden gains and concluded that sudden gains are ubiquitous in psychotherapy, reflect long-term processes that predict outcome and may have more impact on short-term treatments. They also concluded that more research is needed to understand predictors of sudden gains.

A criticism of sudden gains research is that it is perhaps not surprising that patients who show a marked improvement at some point during treatment are likely to show improvement at the end of treatment. This finding alone is of limited empirical and clinical significance but understanding the moderators of sudden gains may help us to understand change processes in psychotherapy when the gains are due to therapy processes, rather than external events. If sudden gains can be related to therapeutic interventions and short- or long-term therapeutic improvements, then it provides support for the effectiveness of those interventions. For example, Andrusyna et al. (Reference Andrusyna, Luborsky, Pham and Tang2006) investigated sudden gains in supportive-expressive therapy for depression. Following the method proposed by Tang and DeRubeis (Reference Tang and DeRubeis1999), they compared pre-gain sessions with control sessions and found significantly greater therapist interpretation accuracy [defined in the study as the degree of congruence between the therapist’s interpretations and the client’s core conflictual relationship themes (CCRTs; Luborsky, Reference Luborsky1984)], better therapeutic alliance at a trend level, but an almost identical number of cognitive changes. They suggested this supported the notion that sudden gains in different treatments might be associated with different therapy mechanisms. A promising area of research focuses on the relationship between sudden gains and cognitive change. For example, Tang et al. (Reference Tang, DeRubeis, Beberman and Pham2005) found that sudden gains in CBT for depression were preceded by substantial cognitive changes in the pre-gain sessions and a study of transdiagnostic group CBT for anxiety disorders reported greater within-session cognitive change for clients with a sudden gain compared with those without, although only 17% of clients experienced a sudden gain (Norton et al., Reference Norton, Klenck and Barrera2010).

The present study examines sudden gains in individual CBT for panic disorder and investigates the relationship between these gains and prior cognitive change. The cognitive model of panic disorder (Clark, Reference Clark1986; Clark, Reference Clark, Rachman and Maser1988) proposes that panic attacks are the result of catastrophic misinterpretations of bodily symptoms, most of which are symptoms of anxiety. This catastrophic misinterpretation involves perceiving the symptoms as immediately threatening, for example a racing heart indicating an impending heart attack or breathlessness indicating being unable to breath. There is evidence that patients who are prone to panic attacks have unhelpful beliefs about the dangerousness of certain body sensations (Clark, Reference Clark1986; Clark, Reference Clark and Salkovskis1996) so a change in these beliefs is predicted to be an important change process in successful CBT for panic disorder (Salkovskis and Clark, Reference Salkovskis and Clark1991). One might therefore expect a sudden gain to be preceded by a cognitive shift in key catastrophic threat cognitions. The present study investigated the occurrence and timing of sudden gains, and changes in catastrophic cognitions prior to sudden gains.

The study was designed to test two hypotheses: (1) participants who experience a sudden gain during treatment will be more likely to have shown more change in panic symptoms (pre- to post-treatment) than those who do not experience a sudden gain; and (2) greater reductions in the believability of catastrophic cognitions regarding panic symptoms will take place in a session that precedes a sudden gain than in a control treatment session.

Method

Setting

This study was carried out in four NHS Talking Therapies, for anxiety and depression services [formally known as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) Services] in the north of England. CBT was provided either directly following an initial screening or after clients had failed to recover after receiving a brief, low-intensity intervention such as guided self-help. The therapy was provided by qualified cognitive behavioural therapists who were accredited with the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapists (BABCP).

Participants

All participants were adults, aged 18 and above. Inclusion criteria were: (i) that they met DSM-IV criteria for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (the study was carried out prior to publication of DSM-5); (ii) demonstrated a pre-treatment score of 8 or more on the Panic Disorder Severity Scale Self-Report Version (PDSS-SR; Houck et al., Reference Houck, Spiegel, Shear and Rucci2002); (iii) were referred to the participating services for treatment of panic disorder as a primary concern. The exclusion criteria were consistent with those typically used in the clinical services where the research took place and included: (i) current alcohol or substance dependence as determined by the assessing clinician; (ii) a diagnosed learning disability; (iii) a current diagnosis of schizophrenia or a psychotic disorder; (iv) a current diagnosis of dementia. Participants were included in the study if they attended at least five sessions of CBT for panic disorder, considered to be a sufficient ‘dose’ of therapy in which a sudden gain related to the therapy may occur, as prior evidence shows that sudden gains mostly occur during this early phase of treatment (Aderka et al., Reference Aderka, Anholt, van Balkom, Smit, Hermesh and van Oppen2012a). In addition, this minimum number of attended sessions was also required due to the operational definition of sudden gains, which requires this event to be identified based on changes that occur relative to preceding sessions and which is maintained for the subsequent sessions (see technical details below).

In total, 133 patients who potentially met the study criteria provided consent to take part in suitability assessments. Of these, 63 attended the assessment session and 62 of these were confirmed as meeting criteria for the study (one individual was excluded because they no longer scored above the clinical cut-off for a diagnosis of panic disorder before starting treatment). Some potential participants were not recruited into the study because they failed to attend screening appointments, or because it was not feasible for them to attend appointments with a study therapist for practical reasons (i.e. location of the therapist’s office, or availability of more convenient appointments). A further nine patients were excluded from the analysis because they attended fewer than five sessions, so 53 were included in the analysis.

Recruitment

A lead research clinician was identified at each participating service, together with a number of CBT therapists who had chosen to participate in the research (participating therapists). Potential participants were identified in one of three ways: (i) via routine clinical assessments following referral to the service; (ii) from the therapy waiting list after having been assessed as meeting criteria for panic disorder; or (iii) through case discussions with colleagues/supervisees who undertook routine assessments with new patients. Potentially eligible participants were sent a study information sheet and consent form in the post. Patients who provided written consent were allocated to a participating therapist and invited to a screening interview conducted by telephone or in person. During this interview, the therapist administered the panic disorder and agoraphobia sections of the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar1998), in order to determine whether the individual met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for panic disorder.

Measures

Assessment of panic disorder diagnosis

The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI; Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar1998) is a structured diagnostic interview to assess the presence of DSM-IV and ICD-10 psychiatric disorders. It was designed to be short, structured and administered by non-specialists. Good test–re–test and inter-rater reliabilities have been reported (Lecrubier et al., Reference Lecrubier, Sheehan, Weiller, Amorim, Bonora, Sheehan, Janavs and Dunbar1997; Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar1998) and it has been validated against the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Lecrubier et al., Reference Lecrubier, Sheehan, Weiller, Amorim, Bonora, Sheehan, Janavs and Dunbar1997) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IH-R patients (SCID; Sheehan et al., Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker and Dunbar1998).

Assessment of sudden gains in panic symptoms

The Panic Disorder Severity Scale Self-Report Version (PDSS-SR; Houck et al., Reference Houck, Spiegel, Shear and Rucci2002) was administered at the start of each therapy session in order to measure the severity of panic symptoms and to identify sudden gains. The PDSS–SR consists of seven items, scored from 0 to 4, which assess the frequency of panic symptoms and related distress and impairment during the previous week. A total score is then computed by summing the individual items. The total score ranges from 0 to 28, with a score of 8 and above indicating the presence of clinically significant panic symptoms. The PDSS-SR was developed from the Panic Disorder Severity Scale (PDSS; Shear et al., Reference Shear, Brown, Barlow, Money, Sholomskas, Woods, Gorman and Papp1997), a clinician-administered assessment tool. Houck et al. (Reference Houck, Spiegel, Shear and Rucci2002) compared the reliability of the PDSS-SR with that of the PDSS. They reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.917 for the PDSS-SR, compared with 0.923 for the PDSS, suggesting a similar level of internal consistency. The test–re–test reliability of the PDSS-SR was good (ICC=0.81) and it was also found to be sensitive to change during a course of CBT, demonstrating a mean decrease of 7.3 (SD=5.1). Wuyek et al. (Reference Wuyek, Antony and McCabe2011) compared the PDSS and the PDSS-SR and found that the PDSS and the PDSS-SR have acceptable reliability, with the PDSS having acceptable validity and the PDSS-SR having promising validity. Wuyek et al. (Reference Wuyek, Antony and McCabe2011) concluded that total scores on both the PDSS and the PDSS-SR provide a useful indicator of the severity of panic-related symptoms.

Assessment of catastrophic misinterpretations of bodily sensations

A modified version of the Agoraphobia Cognitions Questionnaire (ACQ; Chambless et al., Reference Chambless, Caputo, Bright and Gallagher1984) was administered at the start and end of each therapy session in order to identify changes in key catastrophic cognitions associated with panic attacks. The original ACQ consists of 14 cognitions that might pass through a person’s mind when feeling nervous or frightened in relation to threat from bodily symptoms, e.g. ‘I am going to pass out’ and ‘I must have a brain tumour’ together with an option to add two further idiosyncratic cognitions. Respondents are required to rate how frequently the cognitions occur on a 5–point Likert scale from 1 (‘thought never occurs’) to 5 (‘thought always occurs’). David Clark, who proposed the cognitive behavioural model of panic disorder (Clark, Reference Clark1986), and colleagues developed a modified ACQ, the ACQm, which includes an additional scale in which respondents are asked to rate how strongly the cognition was believed when experiencing panic symptoms. Belief ratings for each cognition range from 0 to 100%, with anchor points of 0 (‘I do not believe this thought at all’) and 100 (‘I am completely convinced this thought is true’). The ACQm also includes four additional cognitions. The ACQm was used clinically by David Clark and the team at the Oxford Centre for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma, an internationally recognised clinical and research setting, as well as other CBT therapists, in order to assess key cognitions and changes in cognitions over time during CBT for panic disorder, guide the process of therapy and identify targets for treatment. As the ACQm has clinical utility to detect changes in cognitions, it was considered to be the best option for this study of CBT for panic disorder in routine NHS settings. The original ACQ has been shown to be internally consistent, have adequate test–re–test reliability for periods of up to one month and to have construct validity in relation to fear of fear analyses (Chambless et al., Reference Chambless, Caputo, Bright and Gallagher1984; Chambless and Gracely, Reference Chambless and Gracely1989).

Assessment of depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke and Spitzer, Reference Kroenke and Spitzer2002) is a 9–item self-report questionnaire which measures depressive symptomatology. Scores range from 0 to 27, and are categorised as follows: 0–4, no depression; 5–9, mild depression; 10–14, moderate depression; 15–19, moderately severe depression; 20–27, severe depression.

Assessment of anxiety

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Reference Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams and Löwe2006) consists of seven items. It is a self-report questionnaire that is used to measure change in anxiety symptomatology at each session. Scores range from 0 to 21 and are categorised as follows: 0–4, no anxiety; 5–9, mild anxiety; 10–14, moderate anxiety; 15–21, severe anxiety.

Participants completed the PDSS-SR prior to each therapy session and the modified ACQ prior to and at the end of each therapy session.

Treatment

All clients received face-to-face individual CBT for panic disorder, based on the Salkovskis and Clark treatment manual (Salkovskis and Clark, Reference Salkovskis and Clark1991), with first therapy sessions taking place between January 2012 and June 2014. All therapists were trained in cognitive behavioural psychotherapy and accredited by the British Association of Cognitive and Behavioural Psychotherapists (BABCP). Booster training and supervision workshops were provided by an expert CBT therapist and trainer who co-authored the treatment manual.

Statistical analysis

Definition of sudden gains

The PDSS-SR was used to measure sudden gains. We used a definition of sudden gains based on Tang and DeRubeis (Reference Tang and DeRubeis1999): (i) the gain had to be large in absolute terms which we operationalised as a change large enough to meet the definition of reliable change (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991), using the standard deviation of a pre-treatment clinical group on the measure to calculate the reliability of the measure. In keeping with the recommendations of Lambert and Ogles (Reference Lambert and Ogles2009), we used the estimate of internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) rather than test–re-test reliability to make this calculation; (ii) the improvement had to be large relative to symptom severity before the gain. We used the Tang and DeRubeis (Reference Tang and DeRubeis1999) criterion of an improvement that was at least 25% of the score in the pre-gain session; (iii) the improvement must be large relative to symptom fluctuation before and after the gain. The Tang and DeRubeis (Reference Tang and DeRubeis1999) definition used a t-test to establish that the three scores before the sudden gain were significantly higher than the three scores after the sudden gain. However, it has been pointed out that this prevents the examination of very early or very late sudden gains and subsequent definitions have required only two sessions before or after the gain to allow the examination of early and late gains (Tang et al., Reference Tang, DeRubeis, Beberman and Pham2005). This strategy is supported by the evidence that early gains may be especially predictive of outcome (Lutz et al., Reference Lutz, Stulz and Köck2009; Stulz et al., Reference Stulz, Lutz, Leach, Lucock and Barkham2007). The use of a t-test for this criterion has also been criticised because the comparison is based on repeated measurement of the same person over time, which violates the assumption of independence of errors. Subsequent definitions have instead required that the mean score of the three sessions before the sudden gain (or two for early sudden gains) is higher than the mean of the three sessions after the sudden gain (or two for late sudden gains), where higher is defined as at least 2.78 times the pooled standard deviation (Tang et al., Reference Tang, DeRubeis, Beberman and Pham2005). We used this re-worked form of Tang and DeRubeis’ stability criterion in the current study.

Descriptive characteristics

For differences between the two groups on descriptive characteristics, independent t–tests were used for continuous outcomes if parametric assumptions were met. For the t–tests, data were examined for outliers, normality and homogeneity of variance. The Mann–Whitney U–test was used if the assumptions were not met. Fisher’s exact test was used for dichotomous data; it was used in preference to chi square because of low expected cell sizes.

Hypothesis testing

Hypothesis 1

Participants who experience a sudden gain during treatment will be more likely to have shown more change in panic symptoms (pre- to post-treatment) than those who do not experience a sudden gain. This was assessed with a repeated measures ANOVA (sudden gain vs no-gain group × time). The assumption of the repeated measures ANOVA (e.g. normality, sphericity) were checked. In addition, an odds ratio with 95% confidence interval was also calculated to assess the relationship between group status (sudden gain vs no gain) and whether a participant scored in the non-clinical (<8) or clinical range (≥8) on the PDSS-SR at post-treatment.

Hypothesis 2

Greater reductions in the believability of catastrophic cognitions regarding panic symptoms will take place in a session that precedes a sudden gain than in a control treatment session. For those participants who did experience a sudden gain, the amount of within-session change on the panic cognitions in the pre-gain session was compared with the within-session change in a control session (the session before the pre-gain session) to examine the relationship between within-session cognitive change and the occurrence of sudden gains. This was the approach taken by Tang and DeRubeis (Reference Tang and DeRubeis1999). We calculated this based on using the highest ACQ item score in the pre-gain session as the reference score on the assumption that the most strongly held catastrophic cognitions would be most likely involved in the maintenance of panic and most likely to lead to improvement if they were modified. This is consistent with the cognitive model of panic disorder. Within-session cognitive change was calculated as a change score (pre-session belief ratings minus post-session belief ratings). A paired samples t–test was used to compare the cognitive change scores for the two sessions.

All analyses were conducted in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 23.

Results

Characteristics of the sudden gain and no-gain groups

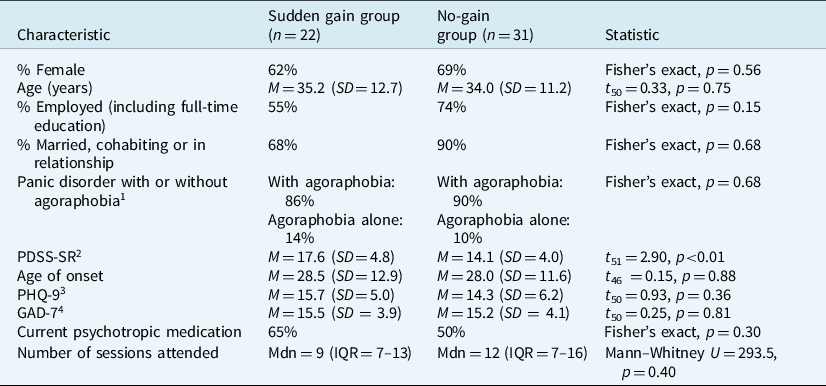

Of the 53 participants who met inclusion criteria and attended at least five therapy sessions, 22 (42%) experienced a sudden gain during the course of treatment; the remaining 31 (the no-gain group) did not experience a sudden gain. As Table 1 summarises, the two groups were broadly comparable on demographic characteristics, pre-treatment indices of panic disorder and broader indices of psychological symptoms, with the exception of pre-treatment scores on the PDSS-SR, on which the sudden gain group had a significantly higher pre-treatment score. Although the sudden gain group had fewer sessions than the no-gain group, the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 1. Characteristics of the sudden gain and no-gain groups

1 Based on Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview rating;

2 Panic Disorder Severity Scale – Self Rating Version;

3 Patient Health Questionnaire-9 scale;

4 Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale.

Description of sudden gains

Of the 22 participants who experienced a sudden gain, three experienced more than one gain during treatment, with all three experiencing two gains. The majority of sudden gains occurred in the early part of treatment, with the median pre-gain session occurring at session 3 (IQR=3–6). The pre-gain session for 18 (82%) of the sudden gains (first sudden gain for those experiencing more than one gain during treatment) occurred at session 6 or earlier. There was a reversal of the gain for four of the 22 participants (i.e. 50% or more of the gain was reversed at any point during the subsequent treatment).

Relationship to post-treatment outcome

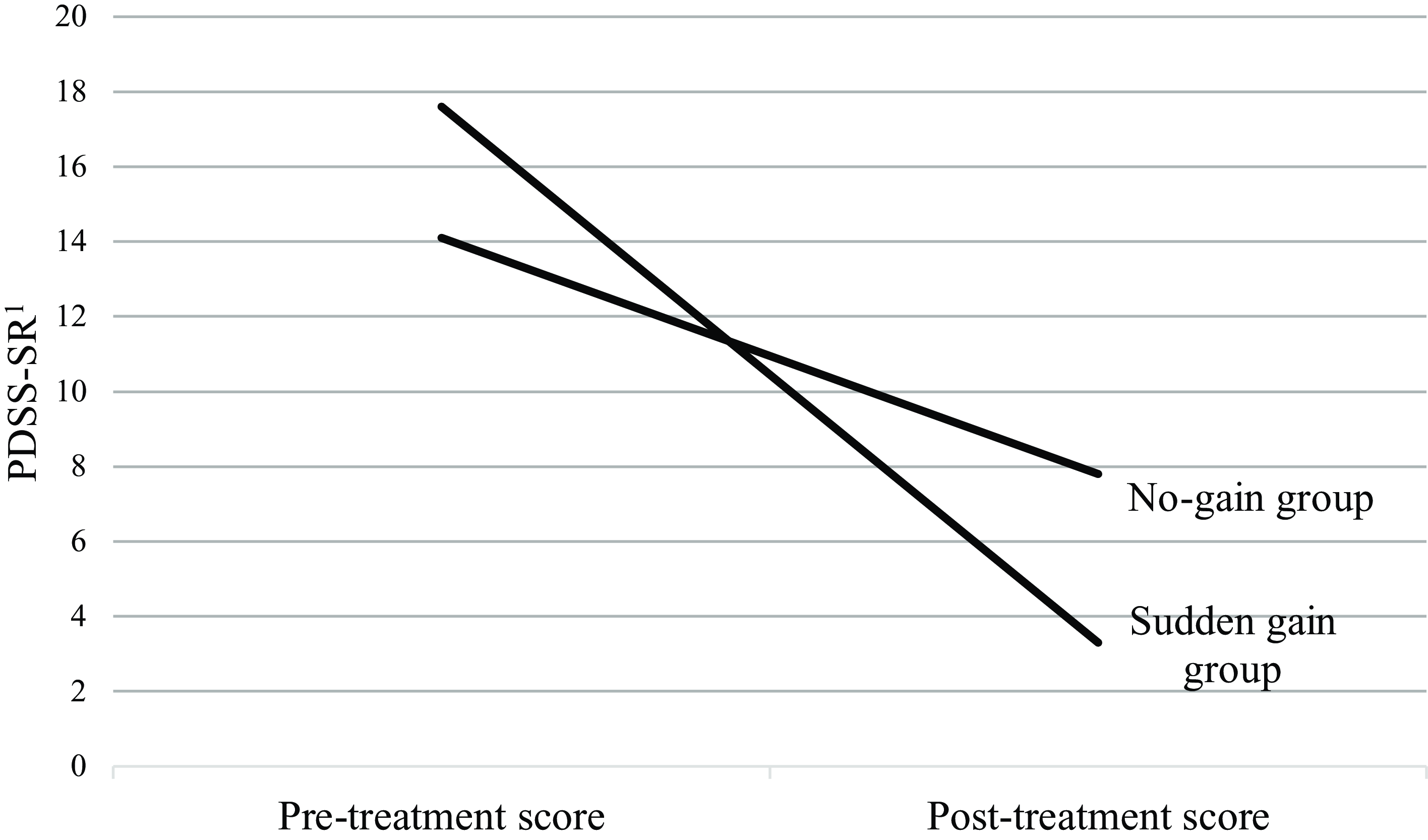

The change in scores from pre-treatment to post-treatment for the two groups is summarised in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Mean pre- and post-treatment scores on the PDSS-SR for the sudden gain and no-gain groups. 1Panic Disorder Severity Scale – Self Rating Version.

Those participants who had experienced a sudden gain had a mean pre-treatment score of 17.6 (SD=4.8) and post-treatment mean of 3.3 (SD=3.8). The group who did not make a sudden gain had a pre-treatment mean of 14.1 (SD=4.0) and a post-treatment mean of 7.8 (SD=4.6). Although there was some non-normality owing to scores of zero at post-treatment, skewness and kurtosis statistics were all within –2 to +2, so a repeated measures ANOVA was used. There was no main effect for group (F 1,49=0.62, p=0.44, partial η2=0.01). There was a main effect for time (F 1,49=168.37, p < 0.001, partial η2=0.78), which indicates that the sample as a whole improved in panic symptoms from pre- to post-treatment. There was also a significant time by group interaction (F 1,49=25.05, p < 0.001, partial η2=0.39), which indicates that the improvement in scores from pre- to post-treatment was greater in the sudden gain group than the no-gain group.

The sudden gain group were more likely to be in the non-clinical range on the PDSS–SR (score of < 8) at post-treatment. Approximately 82% (18/22) of the sudden gain group were in the non-clinical range compared with 42% (13/31) of the no-gain group (OR=6.2; 95% CI=1.6–22.8).

Relationship between sudden gain and within-session cognitive change

The relationship between cognitive change and the occurrence of sudden gains was examined using the highest ACQ score in the pre-gain session as the reference score. The within-session change score in the pre-gain session (M=21.9, SD=25.1) was greater than in the pre-pre-gain session (M=2.1, SD=14.0). A paired t–test indicated a significant difference in change in the two sessions (t 18=3.57, p < 0.01).

Discussion

The finding that patients who experienced a sudden gain tended to experience significantly better post-treatment outcomes is consistent with previous studies (reviewed by Shalom and Aderka, Reference Shalom and Aderka2020), which suggests that sudden gains are significant events, contributing to a positive treatment outcome. Despite the large number of studies in this field, this is the first study to investigate sudden gains in individual CBT for panic disorder.

As we pointed out in the introduction, this finding has limited clinical and empirical significance unless evidence is provided on factors associated with sudden gains. We addressed this by investigating the relationship between sudden gains and prior cognitive change and our study suggests that, in CBT for panic disorder, sudden gains may at least in part reflect cognitive change which occurred in the preceding session. It is noteworthy that we found an association between prior cognitive change and a sudden gain, whilst the Clerkin et al. (Reference Clerkin, Teachman and Smith-Janik2008) study with group-based CBT for panic disorder found sudden gains predicted changes in cognitive biases at the end of treatment. Shalom and Aderka (Reference Shalom and Aderka2020) report inconsistent findings of cognitive change preceding sudden gains (from studies of a range of disorders) and of methodological issues such as different types of measure and different sudden gains criteria. However, given that it is likely that the causes of sudden gains are varied (and they could also be influenced by life events), it is likely that cognitive changes are more likely to contribute to sudden gains in some treatments and some disorders than others. Our prediction of cognitive change was taken from a cognitive model of panic disorder (Clark, Reference Clark1986), which predicts that a key change process leading to successful therapy would be a weakening of catastrophic misinterpretations of panic symptoms and which are addressed in CBT for panic disorder (Salkovskis and Clark, Reference Salkovskis and Clark1991). The clinical implication is that our findings support the view that CBT based on the cognitive model of panic disorder does weaken catastrophic misinterpretations of symptoms which then leads to reductions in panic severity which are maintained over time. This association between prior cognitive change and sudden gains may apply more to CBT for panic disorder but not necessarily to other disorders and treatments, for example Bohn et al. (Reference Bohn, Aderka, Schreiber, Stangier and Hofmann2013) found no significant changes in cognitions before sudden gains in cognitive therapy and interpersonal therapy for social anxiety disorder.

Although this study suggests that cognitive change contributed to the sudden gain, other factors will have contributed to the therapy outcome. For example, Aderka and Shalom (Reference Aderka and Shalom2021) highlight not only predictors of sudden gains but also the consequences of sudden gains, and there is evidence that sudden gains lead to improvements in the therapeutic alliance (Lutz et al., Reference Lutz, Ehrlich, Rubel, Hallwachs, Röttger, Jorasz, Mocanu, Vocks, Schulte and Tschitsaz-Stucki2013; Zilcha-Mano et al., Reference Zilcha-Mano, Errazuriz, Yaffe-Herbst, German and DeRubeis2019). Aderka and Shalom (Reference Aderka and Shalom2021) suggest that sudden gains are due to natural symptom fluctuations as well as treatment-specific factors, which then lead to processes that improve outcomes such as an improved alliance or treatment outcome expectations. This is similar to the suggestion by Tang and DeRubeis (Reference Tang and DeRubeis1999) that sudden gains may be part of an ‘upward spiral’, in which they lead to subsequent cognitive changes and then to further reductions in symptoms. Current evidence indicates that early response during the first month of treatment is associated with better outcomes across CBT and other types of psychological interventions, which is plausibly influenced by common factors such as the enhancement of hope and positive expectations (Beard and Delgadillo, Reference Beard and Delgadillo2019). Sudden gains most often occur during the early phase of treatment (Aderka et al., Reference Aderka, Anholt, van Balkom, Smit, Hermesh and van Oppen2012a). It is still unclear if improved outcomes in patients with sudden gains may be an epiphenomenon of common factors, a specific change mechanism attributable to cognitive change (as suggested by our results), or some complex combination of common and specific factors. Future research in this area could aim to understand the relationships between common factors (e.g. expectancy, alliance) and specific factors (e.g. cognitive change) using time-series methods such as cross-lagged panel designs or dynamic structural equation modelling of these variables collected on a session-by-session basis.

The finding that most of the sudden gains occurred in the early part of treatment, suggesting that cognitive change occurred early on, is consistent with the finding that early change predicts outcome in psychotherapy (Lutz et al., Reference Lutz, Lambert, Harmon, Stultz, Tschitsaz and Schurch2006; Lutz et al., Reference Lutz, Stulz and Köck2009; Stulz et al., Reference Stulz, Lutz, Leach, Lucock and Barkham2007) and with a study by Lutz et al. (Reference Lutz, Hofmann, Rubel, Boswell, Shear, Gorman, Woods and Barlow2014) which identified a group of panic disorder patients whose symptoms decreased early in CBT and went on to experience the best outcomes. It is still highly plausible that early sudden gains are due at least in part to cognitive change in the previous session, because this is consistent with clinical experience where catastrophic cognitions are often identified and addressed early in CBT for panic disorder and patients are often relieved to learn an alternative explanation for their panic-related symptoms. A possible clinical implication of the study is therefore that an early focus on catastrophic cognitions is effective.

The finding that the sudden gain group had a significantly higher PDSS score pre-treatment raises the possibility that the results could be influenced by methodological artefacts. The sudden gain criteria, including a large enough drop in symptoms, constrains the analysis to cases with more severe symptoms, where a large enough drop can be detected. It is plausible that cases with lower severity could also have clinically important shifts in cognitions and symptoms, but we could not detect these using the conventional criteria for a sudden gain. We are therefore not concluding that sudden gains are more likely in severe cases, it just means that our current methods constrain us to only be able to detect these sudden gains in cases that have more room for improvement (e.g. the floor effect problem). This limitation applies to other studies of sudden gains in psychotherapy.

There are a number of other limitations of this study. Although we found a relationship between sudden gains and preceding cognitive change, we cannot be sure that this is a causal relationship. The relationship between cognitive change, behaviour change and symptom reduction will be complex and occur over time and sudden gains can only provide a ‘snapshot’ of a particular part of the therapy process. Another possible limitation of our study is our measure of cognition, a self-rating of the degree of belief in the highest rated cognition on the ACQ associated with a panic attack. Although there are alternative ways of measuring cognitive change, our approach has very strong clinical relevance in that it reflects the therapy itself, where the key panic-related cognitions are identified, rated for their strength, evaluated and modified. It is also relevant to the cognitive model of panic which predicts that the most strongly held catastrophic cognitions would be most potent in maintaining the panic cycle. Another limitation is that we were unable to provide detailed information on the content of the pre-gain sessions. We suggest this as an implication for future research, to shed light on which components of CBT are associated with sudden gains.

In conclusion, this study is the first to identify sudden gains in individual CBT for panic disorder, provides evidence for a relationship between prior cognitive change and improvement in panic symptoms and supports the targeting of catastrophic cognitions in CBT for panic disorder. We believe this study also highlights the value of studying sudden gains as indicators of key change processes in psychotherapy.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, M.L., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the patients, therapists and service managers who supported the study. Thanks also to Professor Paul Salkovskis who provided training and supervision workshops for the participating therapists.

Author contributions

Rachel Lee: Conceptualization (equal), Funding acquisition (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Dean McMillan: Conceptualization (equal), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting); Jaime Delgadillo: Investigation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – review & editing (supporting); Rachael Alexander: Investigation (supporting), Project administration (supporting), Resources (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting); Michael Lucock: Conceptualization (equal), Investigation (equal), Methodology (equal), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (lead).

Financial support

This work was supported by a grant from the British Association of Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The study was reviewed and approved by an NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 11/YH/0268) and all participants provided informed consent. Organisational approval was granted by all participating organisations providing the NHS talking therapy services from which participants were recruited. The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.