In Medellin v. Texas (2008), the state of Texas enhanced its reputation as a successful litigant before the U.S. Supreme Court. At issue was whether Texas violated the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations when it arrested Jose Medellin and later sentenced him to death (Reference HoHo 2010). Medellin was a Mexican national who lived illegally in Texas since he was a child. After he brutally murdered two teenage girls, the police arrested and Mirandized him. Medellin waived his rights, confessed, and subsequently received a death sentence. Yet, shortly thereafter, he filed for habeas corpus relief, alleging that Texas violated his rights under the Vienna Convention because authorities never told him he could notify the Mexican consulate of his arrest. The case made its way to the Supreme Court, where six justices ultimately sided with Texas. In a nod to the quality of lawyering, even the New York Times—opposed as it was to the Court's decision—noted that Texas Solicitor General Ted Cruz made a persuasive presentation (Reference StoutStout 2008).

On the other hand, in Holmes v. South Carolina (2006), South Carolina added another loss to its poor record before the High Court. The Court held that the state erred when it refused to allow a convicted felon to offer exculpatory evidence supporting his claim that a third party actually committed the murder of which he was convicted. South Carolina argued that the evidence against the defendant was so strong that he could not introduce the exculpatory evidence. South Carolina had won just one out of eight (13 percent) of its cases since the Court's 1990 term—and this case followed the losing pattern. In a unanimous opinion cutting against the state, Justice Alito wrote that South Carolina's position made “no sense.”

At least since the seminal study by Reference GalanterGalanter (1974) on the significance of “repeat players,” scholars of law and politics have considered the importance of legal advocacy and expertise, and the consequences they hold for litigants and legal change in American society. In particular, the ability of repeat players to utilize their multiple legal advantages—expertise, resources, reputations, and the like—to secure more favorable legal outcomes has reinforced the importance of specialized legal institutions. Litigants who do not enjoy the benefits of experienced counsel and other legal resources are subject to significant disadvantages, especially in their ability to generate favorable legal change. And state governments are no different. States that fail to develop specialized litigation institutions will suffer when they defend themselves in federal court. When, on the other hand, a state creates a specialized legal institution that consists of knowledgeable attorneys who direct the state's appellate litigation, it can enhance its chances of success. Such institutional design fosters both expertise to improve performance and a degree of legal credibility that should enhance how the justices view the state's attorneys. Yet, few studies have explicitly examined the role of institutional design—and specialized state solicitors general (SGs) in particular—in shaping the litigation effectiveness of state governments before the U.S. Supreme Court.

In this study, we consider the importance of legal (appellate) expertise and its importance for state governments seeking to defend their policies before the U.S. Supreme Court. What factors lead some states to win before the Court while others seem destined to lose? The answer, we contend, turns on institutional design and the attributes institutions can foster. Specifically, we argue that states with a formal solicitor general office (OSG)—and that use the attorneys within that office to argue their cases—experience systematically greater success before the U.S. Supreme Court because they foster team-based appellate expertise and professionalism.

Using an analytically rigorous matching technique, we review over 400 Supreme Court cases decided between the 1989 and 2007 terms where a state was a party, and examine the conditions under which those states won (or lost) their cases. The empirical results demonstrate that states are more likely to win when they utilize attorneys from a formal state OSG, even after accounting for the general levels of institutional resources that vary across states. Specifically, a state that uses a state OSG attorney to litigate before the U.S. Supreme Court has a 0.24 greater probably of winning its case than a similar state that does not use an OSG attorney. And we retrieve these results even after accounting for contextual features that might be associated with state success, such as state (non-OSG) institutional resources and ideological compatibility with the Court.

These findings make three contributions. First, they answer an important question about whether state efforts to improve their appellate success have actually done so. Legal experts have noted the increasing role of state SGs in Supreme Court litigation, but have not determined whether those solicitors have enhanced state success on the merits. As Mauro states, “whether the trend [in states utilizing a formal solicitor general's office] has resulted in more wins for the states at the Supreme Court is difficult to say” (Reference MauroMauro 2003: 1). Our results suggest that if states want to enhance their batting averages before the Supreme Court, they should create formal, professionalized SG offices with appellate specialists who argue their cases.

Second, and relatedly, the results highlight the importance of institutional design. While a number of scholars have analyzed, for example, the design of constitutions (Reference Miller, Hammond, Grofman and WittmanMiller and Hammond 1989), central banks (Reference Jeong, Miller and SobelJeong, Miller, and Sobel 2009; Reference North and WeingastNorth and Weingast 1989), bureaucratic agencies (Reference LewisLewis 2003), and the effects of such design, little scholarship examines how institutional design can lead to success before the judiciary (but see Reference Black and OwensBlack and Owens 2012; Reference WohlfarthWohlfarth 2009). Our findings target that scholarly paucity. What is more, the results of this study reinforce the importance of specialized litigation institutions and the significant advantages they foster in the federal judiciary (Reference GalanterGalanter 1974).

Third, knowing why states succeed before the Court informs us about a substantial amount of judicial activity. States participate as parties in approximately one quarter of all Supreme Court cases. Understanding this large bloc of cases can enhance scholarly knowledge of Supreme Court behavior generally. And while previous scholars have contributed a number of insightful works on state governments in the federal judiciary (Reference Goelzhauser and VouvalisGoelzhauser and Vouvalis 2013; Spill Reference Spill Solberg and RaySolberg and Ray 2005; Reference Clayton and McGuireClayton and McGuire 2001; Reference Waltenburg and SwinfordWaltenburg and Swinford 1999; Reference ClaytonClayton 1994; Reference Kearney and SheehanKearney and Sheehan 1992; Reference Epstein and O'ConnorEpstein and O'Connor 1988), it is still unclear empirically whether (and how much) state efforts to enhance their success before the U.S. Supreme Court through OSGs have actually paid off.

Our study unfolds in five parts. First, we establish the importance of studying states and their success before the Supreme Court. Second, we theorize the conditions under which states will be more likely to succeed on the merits before the Court. Third, we explain our data, our analytical matching strategy, and our empirical measures. Fourth, we discuss our methods and results. Fifth, we discuss the implications of our findings.

Critical Players: The States as Litigants Before the U.S. Supreme Court

State governments appear collectively before the U.S. Supreme Court more than any other party aside from the federal government. Footnote 1 As Figure 1 shows, states have been regular parties before the Court since at least 1946. Their involvement, of course, has fluctuated over time. In the 1940s and 1950s, they participated in 15–25 cases per term (roughly 15–20 percent of the Court's docket). Yet, in the 1960s and 1970s, state participation increased to 30 percent of the Court's docket. In recent decades, state party participation has dropped below 20 percent in a mere five terms. Even after the Court's docket shrunk in the 1990s (Reference Owens and SimonOwens and Simon 2012), states retained their status as frequent parties before the Court, participating in 23 percent of the Court's cases on average. In 2004 alone, state governments litigated 33 percent of the Court's cases.

Figure 1. Scatterplot of the Proportion of the Supreme Court's Docket Involving States as Parties per Term (Left Figure), and the Number of Supreme Court Cases per Term Involving States as Parties (Right Figure), 1946–2010. Dotted Lines Represent the Average Value Over Time Using a Lowess Smoother.

Not only do states appear frequently before the Court, they often litigate cases with substantial policy consequences. Roughly 38 percent of cases involving the state governments between the 1946 and 2010 terms turned on issues of criminal procedure. Civil rights issues comprised 17 percent of the cases in which states were parties. What is more, many of the states' cases have attracted substantial interest group participation, further signifying their political and legal salience. For example, the Court received 78 amicus curiae briefs in Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989), 54 amicus briefs in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), and 53 amicus briefs in Washington v. Glucksberg (1997) (Reference CollinsCollins 2008).

While states, overall, have performed fairly well before the Supreme Court (winning 52 percent of their cases on average), significant variation exists in state success by year and across states.Footnote 2 As Figure 2 shows, from 1959 to 1969, the states never won more than half their cases. Since then, however, states have won roughly 56 percent of the time. Perhaps more important for our purposes, though, is the variation among the states. The right-hand portion of Figure 2 shows the variation in success among states that litigated 10 or more cases between the Court's 1946 and 2010 terms. The variation is marked. Massachusetts, for example, won 72 percent of the 47 cases it litigated. Of the 35 cases Oregon litigated, it won 25 (71 percent). Furthermore, California won 66 percent of its 225 cases and Michigan won 65 percent of its 52 cases. On the other hand, South Carolina won only 32 percent of its 25 cases, and Mississippi won a mere 28 percent of its 39 cases.

Figure 2. Scatterplot of the Percentage of Victories for States as Parties to Supreme Court Cases per Term (Left Figure), and the Percentage of Victories per State, Among Those States Arguing Ten or More Cases Before the Court (Right Figure), 1946–2010. The Dotted Line on the Left Panel Represents the Average Value Over Time Using a Lowess Smoother. The Solid Horizontal Line Reflects 50% Success.

Though it is possible to attribute states' varying success to political factors, region, or other contextual features, we believe there is a more systematic component at work. We contend that some states win more than others because they have created, and rely on, state SG offices with appellate specialists to litigate cases. As we explain below, such institutions foster team-based appellate expertise within an office that generates professionalism and, in turn, success.

The Importance of Institutional Design

Institutional design influences legal and policy outcomes. Reference LewisLewis (2003) finds that presidents, under certain conditions, create agencies that generate more favorable policies. Presidents with strong public support—or who face a politically divided Congress—create new agencies that are placed under executive control, which makes it easier for them to ensure that subordinates follow their commands. Congress, likewise, structures bureaucratic institutions so as to expand its influence and limit presidential control (Reference LewisLewis 2003; Reference Snyder and WeingastSnyder and Weingast 2000). Reference McCubbins, Noll and WeingastMcCubbins, Noll, and Weingast (1987) argue that majority coalitions use agency design to protect their policies and ensure that certain agency outcomes are more likely to occur in the future than others. On a more historical note, Reference MillerMiller (1989) notes how the eradication of boss politics and the spoils system led to a change in policies. With experts now manning the helm, business could invest and grow with more certainty and stability. In each instance, the design of an institution and its rules had a direct effect on policy outcomes.

In a similar vein, scholars are increasingly exploring the importance of institutions and state appellate behavior (see, e.g., Reference HoHo 2010; Reference LaytonLayton 2001; Reference MillerMiller 2010; Reference ProvostProvost 2003, Reference Provost2006). For example, Reference Clayton and McGuireClayton and McGuire (2001) and Reference ClaytonClayton (1994) suggest that greater resources might drive the success of state governments before the Court. Reference Kearney and SheehanKearney and Sheehan (1992) find that ideological agreement between a state and the Court leads to greater state success. Reference Waltenburg and SwinfordWaltenburg and Swinford (1999) argue that states have become more capable litigators in recent years, and that the prostates' rights Rehnquist Court encouraged increased state activity (and productivity). That is, as a result of having to defend their policies in the Supreme Court, state Attorney General offices grew in importance, acquired more resources, and became more capable litigators before the High Court.Footnote 3 And Reference MillerMiller (2010) provides a detailed account of state SGs and their roles before state supreme courts.

Only two studies, to our knowledge, touch on whether the creation of state OSGs has led to more success for states before the U.S. Supreme Court. Reference Epstein and O'ConnorEpstein and O'Connor (1988) analyzed all criminal cases decided between 1969 and 1985 to determine which states won their cases and why. They concluded that states with specialized offices (not OSGs though) to handle criminal litigation at the Supreme Court were 19 percent more likely to win their cases than states without such offices. They also discovered that such offices were more important to southern states than to northern states because “the southern states [were] starting from a lower baseline” than nonsouthern states (Reference Epstein and O'ConnorEpstein and O'Connor 1988: 672). Despite the study's suggestion that specialized litigators enhance success, it cannot definitively tell us whether the recent rise in the adoption of state OSGs has led to increased state success. The data employed by Reference Epstein and O'ConnorEpstein and O'Connor (1988) focus only on criminal cases and end just before Chief Justice Rehnquist initiated his federalism push. Further, the study examines decisions before states created their OSGs in the last two waves of adoption. According to Reference MillerMiller (2010), there have been three waves of states adopting OSGs. The first wave began before 1995. The second took place in the late 1990s, and the third occurred after 2003. Because the Reference Epstein and O'ConnorEpstein and O'Connor (1988) data predate these last two waves, it is unclear whether we can make inferences from the study about the impact of state OSGs as institutions.

Reference Goelzhauser and VouvalisGoelzhauser and Vouvalis (2013) suggest that state OSGs may lead to success for state governments. The authors focus specifically on the role of state SGs at the Supreme Court's agenda stage. They find that the presence of a state OSG in a case leads to a 0.07 increase in the probability that the Court grants review to a state's case. The involvement of state SGs improves the odds of review because they are highly qualified lawyers who specialize in Supreme Court litigation and, likewise, know how to screen cases to ensure the state seeks review of only the most meritorious cases. As a consequence, state SG participation drives up the probability of Supreme Court review. Still, even though state OSGs can increase the odds that the Supreme Court hears a state's case, it remains unclear whether state OSG success carries over to the merits stage amidst the numerous competing influences that shape justices' merits decisions. It is possible (though unlikely) that state SG expertise comes exclusively in the form of knowing which cases are most certworthy. Thus, we return to the question that motivates our study: whether state governments that utilize SG offices experience greater success before the Supreme Court than states that fail to create and utilize such offices.

Expertise, State SGs, and Success at the U.S. Supreme Court

We argue that a state SG office will lead states to heightened success before the Court. This is the case for two reasons. First, OSGs foster team-based appellate expertise (Reference Goelzhauser and VouvalisGoelzhauser and Vouvalis 2013). The attorneys within these offices have and use substantial expertise in appellate matters. Second, the office exudes greater professionalism, which leads to enhanced credibility among decision makers. For these two reasons, state OSGs should outperform other attorneys.

The Importance of Appellate Expertise to State OSG Success

State OSGs vary in terms of structure and duties (see, e.g., Symposium 2010: 635–637) but they are all generally charged with applying their appellate expertise toward prevailing in court (Reference HoHo 2010: 474–475). James Layton, Solicitor General of Missouri, argues that there are four broad categories of state SGs (Symposium 2010: 640–641). First, in some states, the SG retains and oversees a group of his or her own appellate specialists. Second, in other states, there is one SG (and perhaps a small number of staff attorneys) who supervises an existing appellate infrastructure of agency attorneys. Third, some states use a mixture of the first two models, with a state OSG and staff that can handle many civil appeals but not all of them. In essence, the state OSG takes the most important appeals and leaves (but oversees) the remainder for agency attorneys. Finally, in some states, the SG simply acts as a consultant to the Attorney General. Yet, even these SGs have considerable appellate expertise and may handle the most sensitive and complex Supreme Court cases (Symposium 2010: 641).

State SGs themselves tell us that state governments employ them precisely because of their appellate expertise (Reference LaytonLayton 2001). States have moved toward OSGs because “[a]ppellate advocacy is specialized work. It draws upon talents and skills which are far different from those utilized in other facets of practicing law” (Reference HoHo 2010: 472). As Dan Schweitzer, Supreme Court Counsel for the National Association of Attorneys General, once stated: “there is a particular skill set to being an appellate lawyer;” state governments “want someone with that skill set to have some role to play in the appellate products that go to the courts” (Symposium 2010: 647). Given their important roles and frequent participation before the Court, some states have sought better representation.

State SGs can employ their expertise in appellate procedure to enhance state success. Appeals courts have unique rules, filing procedures, and institutional quirks that can be difficult to navigate. Actors who specialize in those courts enjoy an immediate advantage over those who do not (Reference NordbyNordby 2009). For example, one reason Texas Attorney General (now U.S. Senator) John Cornyn created his state's OSG was because the attorneys in that office missed important deadlines to file Supreme Court appeals (Symposium 2010: 652). Cornyn wanted to ensure that Texas would have attorneys conversant in appellate procedure, and thus created the Texas OSG.

The heightened appellate expertise fostered by state SG offices also affords them an advantage in terms of deciding whether to pursue an appeal in the first place (Reference Goelzhauser and VouvalisGoelzhauser and Vouvalis 2013). An appellate expert who frequently appears before the Supreme Court is likely to know what types of cases the justices are likely to hear—and how it might decide those cases—better than a line attorney in an agency or in the Attorney General's office who rarely, if ever, argues before the Supreme Court. Knowing the key issues that can attract the Court's attention at the agenda stage can help a case move forward. And making accurate predictions about how the Court will decide a case on the merits can determine whether to appeal at all. As Kenneth Geller, a one-time principal deputy for U.S. Solicitor General Rex Lee, once stated: “In an average year we may only appeal 80 cases; that means another 420 won't be appealed. We want the Court to hear those cases that are the most important to the government …” (quoted in Reference JenkinsJenkins 1983: 736).

State SGs and their teams of appellate experts also can use their expertise to persuade the Supreme Court to support their legal position on the merits of the case. Judges and justices respect high-quality work and are more inclined to give an appellate specialist the benefit of the doubt. Briefs by these specialists “start being read with the presumption that what's being said in there is accurate” (Symposium 2010: 649). For example, numerous commentators argue that the federal SG office is successful because its attorneys are effective at crafting the “right” arguments that appeal to justices specifically and collectively. The familiarity with the Court leads these attorneys to provide justices with the precise information they seek. In short, because they have expertise about appellate procedure, the prospect of prevailing on the merits, and a greater ability to persuade the justices, state SGs can lead their states to greater success before the Supreme Court.

The Importance of Professionalism to State SG Success

At the same time, state OSG attorneys are also likely to win because they are professionals who possess credibility in the eyes of the Court. Research shows that entities run by professionals are more likely to exude the impression of political neutrality, objectivity, and stability. In other words, the justices should take the arguments of professionals more seriously than they do with nonprofessionals with less legal credibility (Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995). And professionals often do, in fact, foster increased stability. For example, Reference Jeong, Miller and SobelJeong et al. (2009) discuss how creating a professionalized central bank allowed the United States to manage its economy more effectively. By creating an independent federal bank consisting of professionals with interests unaligned with politicians (i.e., their interests were to create and stabilize a strong economy), the economy could find stability. In a similar vein, the use of professionals in the early twentieth century helped eradicate boss rule and generated a more efficient distribution of public services (Reference Knott and MillerKnott and Miller 1987; Reference MillerMiller 1989). As Reference MillerMiller (1989) states, business could now invest “without having to worry that the next change in party control in their city government would result in a new round of extortion or elimination of their property rights …” (691). Professionals, with incentives beyond short-term political gains, signaled long-term stability.Footnote 4

Certainly, we know that state SGs have made a concerted effort to be professional and credible. Gregory Coleman, the first Solicitor General of Texas, once explained that he went out of his way to ensure that his actions were credible and professional when he assumed the office, knowing that his actions would set precedent for how all later SGs would be expected to behave. As he stated: “We wanted the briefs, both in substance and in style, to look professional [and] to look like we had put our very, very best into it” (Symposium 2010: 656). He stated further: “After a period of ten years, I think the office is well-known for the quality and the performance of the advocacy in representing the state. I was very pleased to be a part of that” (Symposium 2010: 656). Other state SGs agree. Florida Solicitor General Scott Makar once stated: “the office has a higher duty to the state, its [citizens], and agencies to not merely advance a political, agenda-driven position” (Reference NordbyNordby 2009: 242).

And judges have in fact noticed state OSG professionalism. In a recent symposium on state OSGs, Fifth Circuit Judge Carolyn Dineen King stated: “we understand the lawyers for the state have an institutional role that transcends the politics of the moment. They, no less than we, serve the cause of fidelity to the rule of law … I must say, I applaud the development of excellent SG offices. They are an enormous aid to our court” (Symposium 2010: 680). Her colleague, Judge Priscilla Owen, echoed those remarks when she declared that state SGs take “the longer view,” refuse to “take inconsistent positions,” and do “what is responsible for the big picture” (Symposium 2010: 681). Both judges agreed that they have developed the same relationship with the Texas OSG as they have with the U.S. Solicitor General Office (Symposium 2010: 695).

Perhaps the most vocal judicial recognition of state SG quality—and their abilities to generate success before the Supreme Court—comes from a recent interview Justice Scalia gave to the New York Magazine (Reference SeniorSenior 2013). In his interview, Scalia commented that having good attorneys makes his job easier. He and his colleagues, he said, depend on lawyers to clarify the facts and the law, and that justices listen to them because they know more about the case and the subject than the justices. Importantly, he singled out state SGs as particularly helpful, noting that the creation and use of these SGs has been a major improvement:

Another change is that many of the states have adopted a new office of the solicitor general, so that the people who come to argue from the states are people who know how to conduct appellate argument. In the old days, it would be the attorney general—usually an elected attorney general… Some of them were just disasters. They were throwing away important points of law, not just for their state, but for the other 49. (Reference SeniorSenior 2013)

As Scalia's comment suggests, states that fail to create and rely on an OSG do not reap the same benefits of appellate expertise and professionalism. To be sure, this is not to say that states without an OSG employ unqualified attorneys with no experience and little professionalism. Rather, we claim that, on average, there will be a greater collective appellate expertise and professionalism among OSG attorneys than others. In states without an OSG, the line attorney in the state agency that litigated the case will make a decision to appeal to the Supreme Court, and in some non-OSG states, the attorney who litigated the case in the lower courts may litigate in the U.S. Supreme Court (Reference Epstein and O'ConnorEpstein and O'Connor 1988: 665). And while the Attorney General may oversee the criminal appellate docket and some noncriminal matters, there is little centralization and maximization of collective appellate expertise. It may even be possible that none of the attorneys involved have any appellate experience at all. Given the importance of appellate expertise and professionalism—and the fact that state SGs tend to have both—we expect that state SGs (or deputy SGs) will be more likely to win their cases in the Supreme Court than non-OSG attorneys who argue for states.

Analytical Matching Strategy and Data

To examine whether the presence of a state OSG systematically leads to greater state success before the Court, we are essentially asking a “but for” question—but for the presence of the state SG, would the state have won its case? The most appropriate way to make this determination, of course, would be to observe what happens in a case without a state SG, and then, after the case is decided, rerun history and have the same justices decide the same case but with the state having created and employed an OSG attorney (Reference EpsteinEpstein et al. 2005). Since we cannot do this, we turn to matching analysis.Footnote 5

Matching methods have taken on increasing importance in political science research. In a recent book-length treatment of the U.S. Solicitor General, Reference Black and OwensBlack and Owens (2012) examine whether the federal OSG influences Supreme Court justices to behave in ways they otherwise would not. Reference Boyd, Epstein and MartinBoyd, Epstein, and Martin (2010) use matching methods to determine that the presence of a female judge on a circuit court panel leads the two male judges to vote more liberally in sex discrimination cases than they otherwise would. And Reference EpsteinEpstein et al. (2005) find that war causes justices to vote differently than they do in peacetime.

Matching is a way for researchers to “prune” their data and remove “imbalance” between the treatment and control groups that might otherwise lead to inappropriate inferences (Reference Black and OwensBlack and Owens 2012). Stated more plainly, matching removes observations in which the treatment and control groups have dramatically different characteristics; it retains observations that are as similar as possible, save for the fact that one group observes the treatment effect and the other does not. The analyst takes the data he or she has collected on the topic of interest and matches observations such that the values of covariates in the control group and treatment group are as close as possible to one another. Observations that do not match across groups are discarded. Failure to match the data could result in erroneous inferences about the effects of the independent variable on the dependent variable.

For our purposes, we want a treatment group and a control group that are similar in all relevant features save for the presence of a state OSG attorney litigating on behalf of the state. That is, our treatment is whether a state OSG attorney argued the case. If we observe differences in the probability of victory between the treatment group (an attorney from a state OSG argued the case) and the control group (a non-OSG attorney argued the case), we can infer that the presence of a state SG led to the change.

While it is difficult to obtain perfect balance between the treatment and control group, scholars can nevertheless minimize that imbalance and achieve “approximate balance.”Footnote 6 Once the data are approximately balanced, researchers can fit standard parametric models to the data. As Reference HoHo et al. (2007) state, approximately balanced data lead to stronger statistical estimates and less model dependence. “The only inferences necessary [after approximately balancing the data] are those relatively close to the data, leading to less model dependence and reduced statistical bias than without matching” (Reference Iacus, King and PorroIacus, King, and Porro 2009: 1).

Using a recent innovation called coarsened exact matching (CEM) (Reference Iacus, King and PorroIacus, King, and Porro 2009, Reference Iacus, King and Porro2010, Reference Iacus, King and Porro2012), we matched our treatment and control groups on an “institutional score” (which we define below) that reflects the general degree of institutionalization (apart from a formal state OSG) that varies across states.Footnote 7 We did so because we expect that different states with varying degrees of resources and commitment toward supporting their governmental institutions have consequences for both their litigation success and proclivity to institute a formal OSG. When a state has increased resources overall, it may succeed more in Court (Reference ClaytonClayton 1994; Reference Clayton and McGuireClayton and McGuire 2001). Because some states have a more professionalized legislative and judicial apparatus, they might be better able to win before the Court. A more professionalized legislature, for example, might pass better laws than a part-time legislature, making the state SG's defense of the law easier. Additionally, states with greater resources and institutional commitment should also be better equipped to adopt a formal OSG. Thus, we wish to identify state governments with similar levels of institutional resources and professionalism, thereby providing greater analytical leverage over the independent impact of the presence of an OSG attorney on state success. In other words, we first isolate those states with similar levels of institutionalization, and then divide them into those that employed a formal OSG and those that have not. And then we can estimate those states' (marginal) probability of success based on whether they adopted (and utilized) a formal OSG to argue the case before the Court.

We match on a composite of features that combine to create an “institutional resource” score for each state. By matching on an institutional resource score, we aim to balance our treatment and control groups on relevant traits that identify the sophistication of each state. For example, Reference Epstein and O'ConnorEpstein and O'Connor (1988) find that some states, because of their broader policies, have better reputations and operate from stronger starting points. These state traits “represent microcosms that Supreme Court Justices may perceive as negative or positive” (664). Thus, to create a “General Policy Score” variable, Reference Epstein and O'ConnorEpstein and O'Connor (1988) combined a number of scales such as innovativeness, antidiscrimination and consumer protection statutes, and the amount of money allocated to social welfare programs.Footnote 8

Following Reference McGuireMcGuire's (2004) work on the evolutionary institutionalization of the Supreme Court, we conduct a principal components factor analysis on four variables to create a state institutional resource measure. First, we account for the general professionalism of the state's court of last resort, as measured by the degree of its docket control (Reference SquireSquire 2008). Specifically, the proportion of each state court's docket that is composed of discretionary cases represents the degree of that court's docket control. Second, and relatedly, we account for the general professionalism of the state's court of last resort, as measured by its jurisdictional authority. Reference SquireSquire (2008) measures jurisdictional authority using a count of the number of issue areas where the state court may exercise discretion over the decision to review cases, among seven primary issue areas—administrative agency, civil, disciplinary, juvenile, interlocutory, noncapital crime, and original proceeding. Third, we measure the professionalization of the state's legislature to account for the potential that a more professionalized legislature may be better equipped to pass laws that can withstand judicial scrutiny. State legislative professionalism reflects a composite of legislator salary and benefits, service demands (i.e., length of the legislative session), and total staff size for the average legislator.Footnote 9 Last, we account for the monetary resources that each state allocates to its judiciary using annual budget appropriations. To code this variable, we rely on the annual amount of direct expenditures each state allocates to its judicial system, as reported by the U.S. Census.Footnote 10 Thus, for each state and each year, we retrieve one institutional resource score that is a function of the common variance in state court professionalism, state legislative professionalism, and the state's expenditure on its judiciary.

The resulting institutionalization score represents the general degree of resources and commitment that each state devotes toward its governing apparatus. A low score means the state has devoted few resources to its judiciary, has a part-time legislature, and a less professionalized state supreme court. A larger score, on the other hand, highlights a state that has devoted considerably greater resources to its institutions. The principal components analysis resulted in one principal axis with an eigenvalue greater than 1, which accounted for 71 percent of the common variance. Figure 3 provides a visual representation of the states' institutional resource score for the terms in which they litigated a case before the Court.

Figure 3. Institutional Resource Scores for States During Years in Which They Litigated a Case Before the Supreme Court, 1989–2005.

With our matching strategy on hand, we move to our dependent variable and main covariate of interest. We started with 446 cases decided by the Supreme Court between the 1989 and 2005 terms in which a state government was a party to the case.Footnote 11 We began our sample in 1989 because that is roughly when scholars have been able to obtain more reliable data on state SGs. There is little agreement among scholars as to when various state OSGs were created. As Reference MillerMiller (2010) states: “it is exceedingly difficult to determine the exact dates of establishment” of these offices (241). With the increase in scholarship on states as litigants, and the consistency with which Lexis has named attorneys providing oral argument since the late 1980s, we selected this time period for our examination. The more recent time period also allowed us to conduct online searches to verify the identity of the attorneys Lexis identified in the cases. We examine all orally argued opinions, per curiam, and judgments of the Court in cases brought to the Court through certiorari or appeal by a state as a litigant. We ignore cases in which two states challenged each other as parties.

Our dependent variable reflects whether the final disposition in each case supports the state's position. We code the dependent variable as 1 if the state won on the merits and 0 if not.Footnote 12 Our main covariate of interest (i.e., the treatment effect) is whether the attorney who argued for the state was from a state SG office.Footnote 13 We code State SG Office as 1 if the state attorney who orally argued before the Court was from a state OSG; 0 otherwise. To determine whether the arguing attorney hailed from a state OSG, we obtained the name and title of each attorney who provided oral argument to the Court. If the attorney's title was “Solicitor General” (N = 42), “Solicitor General Assistant” (N = 4), or “Solicitor General Deputy” (N = 3), we coded State SG Office as 1.Footnote 14

While we expect that states will be more likely to win on the merits when they are represented by an OSG attorney, we control for a host of features that may also lead them to success.Footnote 15 We start with whether the state is the petitioner in the case. We do so to control for the Court's well-known proclivity to reverse cases it reviews (Reference PerryPerry 1991). We code State Petitioner as 1 if the state was the petitioner in the case and 0 if it was the respondent. Next, there is considerable evidence to suggest that the U.S. Solicitor General influences justices to vote in favor of the federal government (Reference Black and OwensBlack and Owens 2012; Reference WohlfarthWohlfarth 2009). To measure whether the U.S. Solicitor General supported the state in a case, we created Solicitor General Support. If the U.S. Solicitor General's office filed an amicus curiae brief on the merits of the case supporting the state, we coded Solicitor General Support as 1. If the state challenged the United States, or if the United States filed an amicus brief in opposition to the state's position, we coded Solicitor General Support as −1. In all instances when the United States did not take a position, we coded Solicitor General Support as 0.Footnote 16

We also control for the Supreme Court's ideological proclivity to support a state's position on the merits. One might expect a liberal (conservative) Court to be more likely to support the state's position if it also reflects a liberal (conservative) argument, whereas the Court should be less likely to favor the state when it pushes an ideologically divergent position. To measure how the ideological content of the state's position aligns with the ideological composition of the Court, we follow Reference Johnson, Wahlbeck and SpriggsJohnson, Wahlbeck, and Spriggs (2006) and Reference Black and OwensBlack and Owens (2012). We first determine the ideological direction of the lower court decision as reported in the Supreme Court Database. If the lower court decision was liberal (conservative), we code a state petitioner as making a conservative (liberal) argument. If the state's argument was conservative, we coded our Ideological Distance variable as the Reference Martin and QuinnMartin and Quinn (2002) value of the median member in the majority coalition. If the argument was liberal, we coded our variable by multiplying the median majority member's Martin–Quinn score by −1.Footnote 17

We further control for the net number of amicus curiae briefs filed in favor of the state government. When more briefs are filed in support of the state than its opponent, the Supreme Court may see that as a signal of the general popularity for, or strength of, the state's position. Alternatively, the briefs may provide justices with supportive information. We have strong reason to believe that a state with more outside groups on its side is, on average, more likely to win its case (Reference CollinsCollins 2004; Reference CollinsCollins 2008). Thus, we create a variable—Net Amici Support—that measures the net number of amicus briefs filed in favor of the state's position.Footnote 18 Next, we account for the potential that state success varies systematically depending on the primary issue context of each case. In particular, we specify a separate dichotomous predictor for Criminal Procedure, Civil Rights, First Amendment, and Federalism cases. Each issue predictor takes on a value of 1 if the case primarily involves the designated issue area; 0 otherwise.Footnote 19 Last, we account for each state's Population (in millions) at the time of the Court's decision.Footnote 20

Methods and Results

Recall that the purpose of matching is to balance the treatment and control groups such that the two are as similar as possible but for the presence of the treatment effect. We summarize balance using L1, a measure built into the CEM program that provides an easy-to-interpret index of the degree of imbalance across all multivariate combinations of pretreatment variables in a data set (Reference Iacus, King and PorroIacus, King, and Porro 2010).Footnote 21 A value of 0, which is the minimum possible value taken by L1, corresponds to perfect balance between the treatment and control groups. L1's theoretical maximum of 1 indicates that no overlap exists between the two groups. Our post-matching value of L1 (0.078) is roughly 70 percent smaller than its unmatched value (0.26).

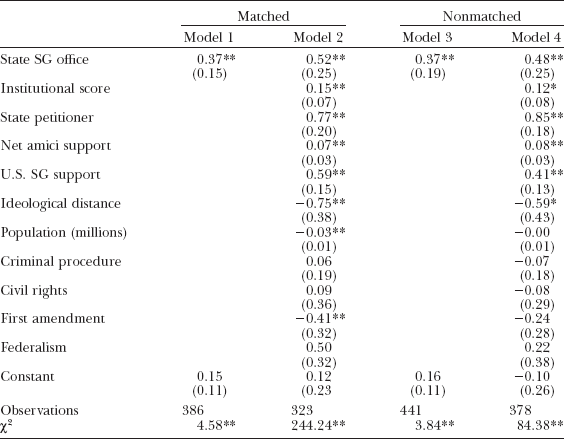

Models 1 and 2 in Table 1 present probit regression results (with robust standard errors clustered on each state) following the CEM approach, while models 3 and 4 present the results of a nonmatched probit regression model.Footnote 22 Models 1 and 3 show the baseline impact of a state OSG by simply regressing whether the state prevailed (on the merits) on whether a state SG argued the case using the matched versus nonmatched data, respectively. Both models show a significant and positive relationship between a state OSG arguing the case and subsequent success on the merits. Models 2 and 4 estimate the impact of a state OSG after adding the relevant control variables using the matched and nonmatched data, respectively. Once again, looking to State SG Office (i.e., the treatment variable), we observe that a state with an OSG attorney who argued the case is much more likely to win compared to an otherwise institutionally similar state that does not utilize such an attorney. What is more, we obtain this result even after matching on our institutional resources score and including statistical controls.Footnote 23

Table 1. The Impact of Institutional Design on State Success Before the U.S. Supreme Court, 1989–2007

Note: Table entries are probit regression coefficients with robust standard errors, clustered on each state, in parentheses. *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05 (one tailed). The dependent variable represents whether a state government won on the merits before the U.S. Supreme Court. Matched observations are matched on institutional score.

Figure 4 illustrates the magnitude of a covariate's impact on state success using the empirical results from the matched, fully specified model 2 in Table 1. We compute predicted probabilities while holding all variables at their mean or modal values (i.e., the state government is the respondent and does not utilize a state SG) and isolate the independent impact of a change in each main covariate.Footnote 24 For instance, the bottom panel of Figure 4 isolates the predicted probability of state success when comparing a case without an OSG attorney to one where an OSG attorney argues the case. We observe that a respondent state that does not use a formal OSG will win its case with an expected 0.38 probability. When, however, a state OSG attorney argues the case, the probability of victory increases to 0.59. This change of 0.21 is not only statistically significant, but also substantively meaningful. If we instead examine the predicted impact of a petitioner state OSG, we still see a positive, though somewhat smaller, effect. A petitioner state OSG can improve the state's already high probability (0.68) of winning by 0.16, raising the expected probability of state success to 0.84.Footnote 25

Figure 4. The Predicted Success of State Governments Before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Dots Represent the Predicted Probability That a State Will Prevail on the Merits Using Results From Model 2 in Table 1, While the Solid Horizontal Lines Represent 95% Confidence Intervals.

One additional way to view the magnitude of the impact of a state OSG on state success is to look at when a state must square off against the U.S. Solicitor General. Figure 5 presents these simulated results, which further underscore the importance of states adopting OSG institutions in order to maximize their chances of prevailing before the Supreme Court. When holding all other variables at their medians (or, where appropriate, modes), we see that a respondent state without an SG's office—that squares off against the U.S. Solicitor General's office—has a 0.19 probability of winning. Yet, when that respondent state has an OSG attorney to argue before the Court, the probability of state victory increases to 0.36, a 17 percent change. The predicted change in the probability of state success is slightly larger when we observe states as petitioners against the U.S. government as the respondent. A petitioner state that does not use an SG's office and that squares off against the U.S. government in this scenario has a 0.45 probability of winning; but when that state petitioner litigates with a state OSG, its probability of winning increases by 0.21 to 0.66. Using a state OSG attorney helps states, especially when they must litigate against an opposing argument by the influential U.S. Solicitor General.

Figure 5. Predicted Success of States in the U.S. Supreme Court When Squaring Off Against the United States, With and Without a State OSG. The Dots Represent the Predicted Probability That a State Will Prevail on the Merits Using Results From Model 2 in Table 1, While the Solid Horizontal Lines Represent 95% Confidence Intervals.

Most of the other variables in Table 1 perform as expected. First, ideological compatibility affects a state government's chances of success on the merits. A state making an ideologically pleasing argument to the Court has a 0.43 probability of winning while a state making an ideologically incongruent argument has only a 0.30 probability of winning. The role of amicus curiae briefs is also an important factor driving state success. Moving from one standard deviation below the mean of the net amicus brief (dis)advantage for the state (i.e., three more briefs filed against the state than for it) to one standard deviation above the mean (i.e., four more briefs filed in support of the state than against it) generates a 0.18 increase in the probability of state victory—shifting the probability of state success from 0.30 to 0.48. When the U.S. Solicitor General's office opposes a state respondent, the state has a mere 0.19 probability of winning. But when the SG's office supports the state as a respondent, that probability jumps to 0.61.Footnote 26 Petitioner status also demonstrates a meaningful (and large) impact. When a state is a respondent before the Court (and there is no state SG office), its probability of victory is 0.38. When it is a petitioner, however, the state's expected probability of success increases substantially to 0.68.Footnote 27

Some institutional design questions remain. Is it enough for a state simply to create an OSG that has loose supervision over state attorneys who then argue on behalf of the state, or does a state need to create a strong OSG that can coordinate and be heavily involved in the cases he or she chooses? In other words, which of the four kinds of SG offices we described above are more successful?Footnote 28 Unfortunately, we cannot answer that question directly, since there are no data on the kinds of SG office each state has used per year over our study. Indeed, even for the most recent years, such data elude us. We can, however, compare our results from above—which looked at whether a state SG argued for the state (and therefore was heavily involved in the case)—with results that look only at whether the state had (but did not necessarily use) the state SG office in the case. That is, we can compare a extensively involved SG to one that does not appear to be extensively involved. To do so, we returned to Reference MillerMiller (2010), who describes whether and when the states adopted SG offices. We took those data and recoded our state SG attorney variable as 1 if the state had an SG office during the dispute (though, again, that office need not have argued before the High Court in the case); 0 otherwise.Footnote 29 In other words, rather than looking at the identity of the attorney arguing for the state, we simply looked at whether the state had an OSG when the Court decided the state's dispute.

We then refit our fully specified model of state success. The data show that simply having an OSG is not enough. The positive coefficient on State SG Office is nowhere near conventional levels of significance in the matched model (p > 0.449). The results are even less supportive in the nonmatched model (p > 0.962). What this suggests to us, then, is that states seeking to design an institution that will lead to heightened success before the High Court should not create toothless OSGs that have little control over the direction and strategy of cases. Rather, they should create more powerful offices that may even look similar to the U.S. Solicitor General's office. In other words, in terms of Layton's four categories of SG offices (Symposium 2010: 640–641), the data suggest the “SG as consultant” model is least useful to states. The first three models, on the other hand, which all observe more extensive SG control, oversight, and visible activity (i.e., arguing before the Supreme Court) appear most useful.

Conclusion

Legal advocacy and legal expertise matter. In an interview on the quality of lawyering, Chief Justice Roberts stated: “[We] may not see your strong case. It's not like judges know what the answer is. I mean we've got to find it out … And so … [without quality lawyering] we may not see that you've got a strong case” (Reference LacovaraLacovara 2008: 285). As Roberts argues, good lawyering can win a case and bad lawyering can lose it. Indeed, a fairly recent study on oral argument confirms as such: Lawyers who make strong oral arguments are more likely to win than those who make weaker arguments (Reference Johnson, Wahlbeck and SpriggsJohnson, Wahlbeck, and Spriggs 2006).

And the effects of lawyering are exacerbated when facing off against a repeat player. Parties that challenge repeat players face considerable difficulties. Repeat players tend to have the resources to stack the deck in their favor, all the way from the trial court to the Supreme Court (e.g., Reference GalanterGalanter 1974). Repeat players, on the other hand, can use their advantages to secure legal change or protect legal positions. They know what arguments justices seek, which issues win, and how to frame cases appropriately. Scholars have known this for years. Still, what remained unclear was how actors can enhance the probability that attorneys have the capacity to make strong arguments. Are there institutions that can channel more effective litigation outcomes?

We set out to demonstrate how states that adopt and use a SG (or OSG attorney) to litigate before the Supreme Court can generate systematically greater success on the merits. Building from existing studies on the success of states before the Court and the role of appellate expertise more generally, we argued that the existence of a state OSG fosters team-based appellate expertise and signals credibility and professionalism to the High Court. Using analytically rigorous matching methods (as well as unmatched probit regression), we demonstrate that state OSG attorneys who argue before the Court experience systematically greater success than non-OSG attorneys. Overall, the results suggest that institutional design can play an integral role in the ability of states to protect and further their policies.

The results also contribute to the study of judicial behavior. The fact that Supreme Court justices are more likely to side with a state OSG attorney than an otherwise similar non-OSG attorney suggests that they can be persuaded by the quality of counsel—and that they pay close attention to who appears before them. At bare minimum, the results suggest that scholars should further examine how resources and expertise influence judicial outcomes.

Perhaps more importantly, these findings answer whether state institutional design—and the creation of OSGs in particular—across the country during the last two decades has been a worthy exercise for states seeking to defend policies before the U.S. Supreme Court. It has. States win when they design formal legal institutions to foster increased appellate litigation expertise and credibility—and then empower those state SGs to argue their cases before the justices. They are better able to protect their interests before the Court and thereby preserve the policies of state legislators. Just as important, they are also better able to shape the broad contours of doctrine the U.S. Supreme Court creates. What is even more remarkable about all this is that it was not long ago that Justice Powell lamented about the generally poor quality of lawyering among state attorneys appearing before the Supreme Court (Reference MorrisMorris 1987). Put plainly, states that want to perform better in the judiciary would be well advised to not only increase their resources generally, but also to consider designing—and empowering—specialized legal institutions to conduct appellate litigation.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Appendix S1. State Solicitors General and Attorneys Before the Supreme Court.

Appendix S2. Data Distribution Following Analytical Matching Strategy.