In 2000, Scotland introduced the Adults with Incapacity Act (Scotland), the first legislation in the UK designed specifically to deal with the medicolegal implications of decision-making. It was followed by the Mental Capacity Act 2005 for England and Wales, and there is now similar legislation in Ireland, in the form of the Assisted Decision-Making (Capacity) Act 2015, and in Northern Ireland, with the Mental Capacity Act (Northern Ireland) 2016.

Where an individual (by legal convention named ‘P’) has to make a decision, P's ability to make that decision is referred to as their mental capacity. An individual judging P's capacity and tasked with acting on the results of that deliberation is referred to as the decision maker. For the sake of simplicity, this article will assume that mental capacity is synonymous with other terms such as decisional capacity, mental competence and mental competency. Some authorities argue that the term ‘competence’ is more appropriate in a legal setting, but the reality is that no convention exists and the confusion caused by this alleged distinction is unhelpful.

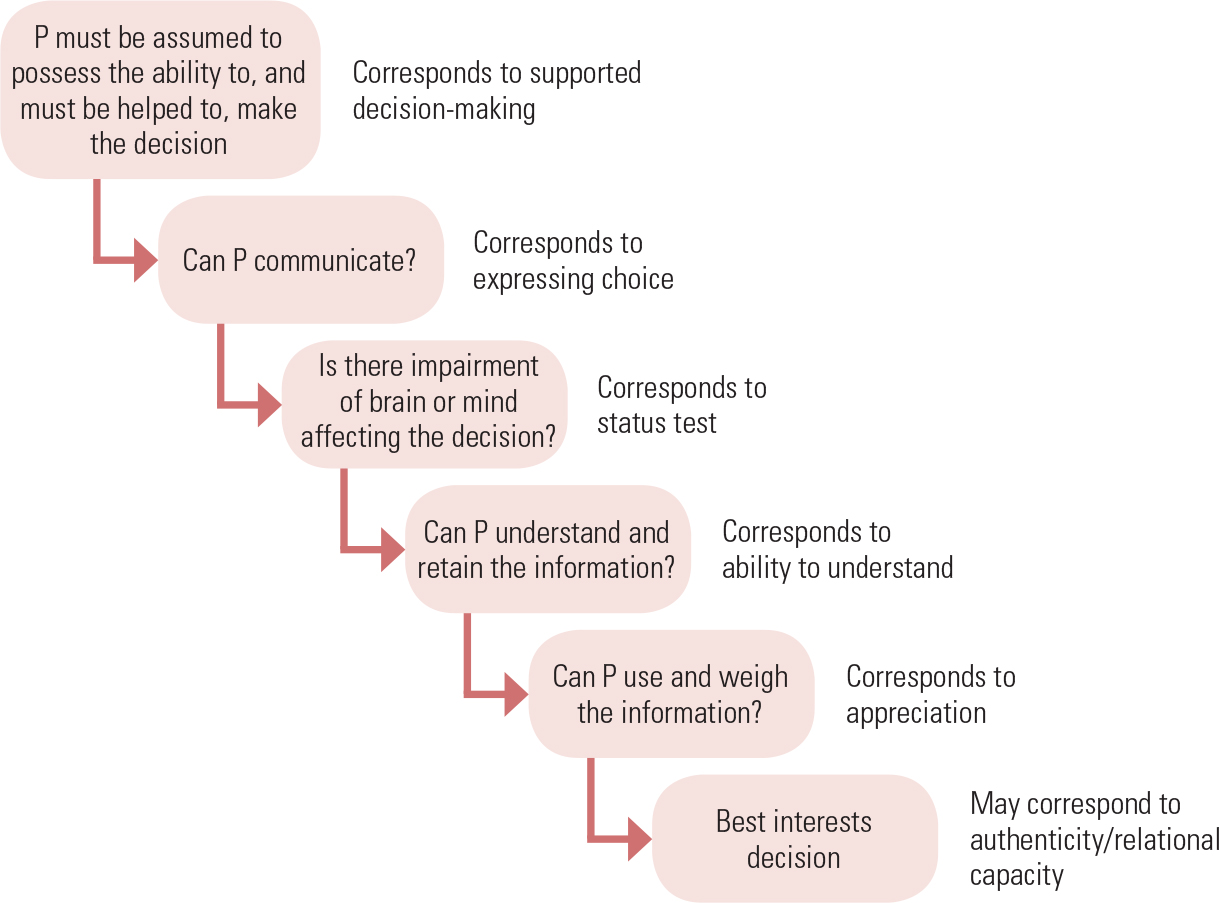

Figure 1 outlines the principles behind the Mental Capacity Act 2005, which will be used as the main example of mental capacity legislation in this article. For a comparison of mental capacity legislation in the UK, see Reference KellyKelly (2015).

FIG 1 Outline of sections 1–4 of Part I of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (England and Wales). ‘P’ refers to the person making or being assisted to make the decision in question.

The important phrase in the wording of the Mental Capacity Act is ‘for the purposes of the Act’; in other words, the test of mental capacity outlined in Fig. 1 is limited to the Mental Capacity Act. There exist other laws that deal with decision-making ability and, where these are applied, other tests of decision-making ability may be used. For instance, the ability to consent to sexual intercourse is a matter for the Sexual Offences Act 2003, although that Act does not give a precise definition of ‘consent’. The Mental Health Act 1983 (as amended in 2007) uses a status test of mental capacity to judge whether an individual should be detained and treated against their apparent will. In a status test of mental capacity, a proxy measure is used to judge whether an individual is legally competent to make a decision or participate in a legal activity. Status tests can be useful where speed and simplicity are required across a population, for example using age to judge whether an individual may vote. In the case of the Mental Health Act, the proxy measure is the presence of a mental illness. However, the Law Commission quickly rejected a status test as an unfair and stigmatising basis on which to test mental capacity for the purposes of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Law Commission 1995). Instead, it opted for a functional test of mental capacity, in which understanding and the process of decision-making are the criteria by which mental capacity is judged. A functional test is only concerned with P's ability to make a particular decision at the material time that it needs to be made. This specificity is often seen as more conducive to P's autonomy. The ‘status’ and ‘functional’ tests are just two examples of a range of methods of judging decision-making ability. The purpose of this article is to discuss the range of tests of mental capacity that exist and to explain their relevance in an era of mental capacity legislation.

It is useful to consider that a subtle but important difference exists between a definition of mental capacity and a test of mental capacity. A definition of mental capacity should be universal and would, bar linguistics, be acceptable to most parties. Definitions of mental capacity should therefore be broad, and examples include:

‘The ability to comprehend the nature of the particular conduct in question and to understand its quality and its consequences’ (Reference Roth, Meisel and LidzRoth 1977).

‘[Incompetence] constitutes a status of the individual that is defined by functional deficits (due to mental illness, mental retardation, or other mental conditions) judged to be sufficiently great that the person currently cannot meet the demands of a specific decision-making situation, weighed in light of its potential consequences’ (Reference Grisso and AppelbaumGrisso 1998).

These definitions have similar principles, but even a universal definition of mental capacity would allow for different ways in which one might evidence it. In a seminal paper in 1977, Roth et al listed a variety of measures of mental capacity, suggesting that different tests might be used in different settings according to the risk–benefit profile of the outcome of the decision. In fact, they concluded that ‘the search for a single test of competency is a search for a Holy Grail’ (Reference Roth, Meisel and LidzRoth 1977).

Nowadays, clinicians suffer the opposite problem: the predominance of functional tests of mental capacity has robbed many clinicians of an understanding of the various ways they might judge an individual's decision-making ability. In exploring these nuances, this article will look at some of the history behind the development of the tests used in modern legislation. Many of these ‘historical’ tests appear in surprising places in modern legislation and a deeper understanding should be useful to mental health practitioners in their everyday practice.

What are the desirable characteristics of a test of mental capacity?

Reference Roth, Meisel and LidzRoth et al (1977) suggested that a test of mental capacity has to meet three criteria:

-

• it must be reliably applied (with an implication that mental capacity should be easy to evidence)

-

• it must be mutually acceptable to, or at least understandable by, all affected parties

-

• it should strike a balance between promoting the patient's autonomy and safeguarding the rights and needs of vulnerable individuals.

To these three, Reference Charland, Zalta, Nodelman and AllenCharland (2011) has added a respect for individual values.

Evidencing choice

This could be seen as the crudest form of mental capacity test, requiring simply that the individual demonstrates a preference for an option. Roth et al described it as a test where no reasoning or justification is required, so that only someone who is incapable of evidencing a choice is deemed to lack mental capacity. One advantage of this approach is that the choice may be demonstrated by a physical behaviour in someone who may otherwise be unable to communicate their reasoning. The risk arises that any professional using ‘evidencing choice’ as a test is more likely to assume that an acquiescent but uncommunicative individual has ‘consented’ if the course of action is preferred by that professional (known as ‘treatment bias’).

Grisso & Applebaum, by contrast, saw the evidencing of choice as a ‘threshold’ test (Reference Grisso and AppelbaumGrisso 1998): they agree that if P cannot communicate a decision he or she is deemed to lack mental capacity, but, unlike Roth et al, they argue that P may still lack mental capacity even if he or she can communicate, depending on the outcome of further tests. The Roth et al version of expressing choice is the most respectful of autonomy but the least likely to safeguard a vulnerable individual, whereas Grisso & Applebaum's version safeguards P but is more likely to disenfranchise him or her from making decisions. Although the Mental Capacity Act ‘communication’ standard is closest to Grisso & Applebaum's definition, the Act stresses that it only applies when all attempts to facilitate communication have been exhausted: locked-in syndrome is an extreme but illustrative example.

Example 1

A 55-year-old man suffering language variant frontal lobe dementia is admitted to a ward as a result of challenging behaviour and a breakdown in his care at home. He is mute and, as he is resistant to many aspects of his treatment, he is initially detained under section 2 of the Mental Health Act 1983. Over the weeks he settles with minimal medical treatment; he accepts treatment and his section is discharged and he is placed on a Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) authorisation before being discharged to a care home. However, the placement breaks down and he has to be re-admitted to the same ward. This time he enters the ward willingly, walks to his old room and smiles and hugs familiar members of staff with whom he bonded during this previous admission. He accepts all treatment. The staff request a DoLS authorisation but the DoLS assessor declines to authorise.

Anyone reading this example before the introduction of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 would have recognised this as an example of evidencing choice as a means of gauging decision-making ability. Although under the Mental Capacity Act this would no longer be considered sufficient (evidencing choice being a threshold test rather than a complete test of mental capacity), the outcome is still compatible with the Act: (i) P is presumed to have mental capacity; (ii) P's actions here could be seen to be a form of communication appropriate to his circumstances.

Although the Mental Capacity Act does not formally recognise evidencing choice as a test of mental capacity, if P has not left an advance directive and does not have an attorney to act on his or her behalf, a decision must be made in his or her best interests (section 4 in Fig. 1). One of the recommendations is that the decision maker must try to ascertain P's views, which can be ‘expressed verbally, in writing or through behaviour or habits’ (my emphasis) (Department for Constitutional Affairs 2007). Note that this is only after an assessment has been made using a functional test of mental capacity, but it is, in effect, giving the decision-making back to P.

Understanding: actual, potential and appreciation

Understanding is the backbone of functional tests of mental capacity. Reference Roth, Meisel and LidzRoth et al (1977) divided the understanding test into a test of actual understanding and a test of an ability to understand. In the former, P is required to demonstrate that he or she has understood all the information pertaining to a decision. However, the amount of information pertaining to, for example, a complex surgical procedure is virtually infinite. This places a burden on P both intellectually and emotionally: intellectually because P would require a medical degree to understand all the possible outcomes (and perhaps not even then), and emotionally in that P may prefer not to listen to all the gory details of the procedure.

An alternative is a judgement of mental capacity based on the potential to understand. The emphasis is on P's ability to understand rather than a test of his or her grasp of the specifics. This is more respectful of an individual's ability to choose, as it means that P can choose to understand as much or as little of the information relevant to the decision as he or she wishes (Reference JonesJones 2016). In either case, P must retain the relevant information long enough to juggle it and come to a decision – a detailed recollection at a later date is not required.

Example 2

A 72-year-old man with recurrent depression and borderline intellectual disability had built up a good therapeutic relationship with his consultant psychiatrist over the years. At the beginning of one of his relapses, he complained that his medication was no longer working for him and asked his consultant for a change. Having reviewed his medication, the consultant explained that the patient had been on medication from all the major antidepressant subgroups and that the only option she could recommend would be a complicated augmentation regime. The information was given over several consultations, aided by simple written information. The patient was able to outline and agree to the basics of what was being proposed, but was distressed by the amount of information being given and the pressure of the decision. ‘I trust you,’ he told his consultant. ‘Why can't you decide?’ The consultant went ahead with what she saw as the treatment option carrying the lowest risk.

The outcome in Example 2 is, again, compatible with the Mental Capacity Act 2005. A clinician who did not understand the legal and ethical principles underpinning the Act might baulk at taking the final steps to change P's medication, or worse, be tempted to detain P under the Mental Health Act to give themselves legal ‘cover’ to make the necessary changes, but an understanding of the legal arguments that went into the Act would show that this is unnecessary.

Mental capacity tests based on understanding form the basis of the functional tests used in modern legislation. Their advantages have already been outlined, but they are not perfect. Problems include the following:

-

• P's decision relies heavily on what the clinician chooses to reveal

-

• P may change his or her mind with no apparent reasoning to explain why. It may be difficult to prove which, if any, is the ‘authentic’ decision for that person.

A test based on understanding alone is arguably more vulnerable to undue influence than other tests of mental capacity: in other words, P may appear able to understand and retain a choice while in fact being pressed into making that decision in order to please or favour someone who is exerting pressure behind the scenes.

Reference Grisso and AppelbaumGrisso & Appelbaum (1998) felt it helpful to consider appreciation as a subclause of understanding, suggesting that ‘appreciation’ can be regarded as the patient's ability to acknowledge their disorder, to accept its relevance to the decision in hand and relate potential treatment consequences to their own circumstances. P's understanding must go beyond a theoretical understanding of the options: P must understand what they mean for him or her. A man may be able to understand that there are treatments for schizophrenia, but if he does not have insight into the fact that he has the condition he will be unable to conceive that these options apply to him: he would then ‘fail’ the appreciation test. The Re C court case outlined in Box 1 is a good example of appreciation in action: the fact that C was experiencing a psychotic delusion that he was a surgeon did not stop him believing and perceiving the relevance of the information given to him, as demonstrated by his comment that he would prefer to ‘die with two feet than live with one’. Therefore an irrational belief is permissible if it is (a) not seen to be caused by the mental disorder or (b) not influencing the final treatment choice.

BOX 1 The Re C case

C was a patient with chronic schizophrenia detained in a high-security hospital under the Mental Health Act 1983. He declined a potentially life-saving operation to amputate his leg, opting for the more risky option of antibiotic treatment. Although the antibiotic treatment was successful, he sought an injunction to prevent the surgical team from amputating his leg if his condition deteriorated. C's argument was that he would rather ‘die with two feet than live with one’. Despite his delusion that he was a world-class surgeon, C was judged to be capable of understanding, believing and weighing the information given to him. Considerations such as his detention under the Mental Health Act, his illness and the risk to his life were considered secondary to his autonomy to make this decision.

C was considered to have mental capacity because he was able to:

-

• understand, and

-

• retain, and

-

• believe and weigh the information given to him to arrive at a clear choice.

(Re C (Adult refusal of medical treatment) [1994] 1 WLR 290; [1994] 1 All ER 819)

The Law Commission did not explicitly incorporate appreciation into the then draft Mental Capacity Act, preferring, in its own terms, to ‘deflect’ the issue by using the phrase to ‘use and weigh’ (Law Commission 1995). This included (or, by another interpretation, made redundant) the Re C criterion of believing the information given. Instead the Law Commission suggests the following definition of a failure to use and weigh:

‘the person's eventual decision is divorced from his or her ability to understand the relevant information […]. A decision based on a compulsion, the overpowering will of a third party or any other inability to act on relevant information as a result of mental disability is not a decision made by a person with decision-making capacity’ (Law Commission 1995: para 3.17).

All UK mental capacity legislation (except that in Scotland) explicitly states that, to have mental capacity, P must be able to ‘use and weigh’ that information as part of the process of making a decision.

Rationality tests: outcome and process

Reference Roth, Meisel and LidzRoth et al (1977) split rationality tests into reasonable outcome and rational process decisions. In the outcome test, P is regarded as having mental capacity if the outcome of his or her decision is considered ‘rational’ and appropriate. This is clearly open to abuse, as the use of the word ‘rational’ is subject to huge individual variation. As no decision maker would propose a course of action unless they felt it was appropriate, the test becomes as much a test of the clinician's ‘rationality’ as the patient's! Although Roth is no advocate of a rationality approach, he and his colleagues point out that the test is used more often in legal settings than we care to admit – English and Welsh courts frequently use the ‘man on the Clapham omnibus’ test, in which a legal decision is benchmarked against the views of an imaginary reasonable, ordinary member of society. It could be argued that there is a distinction, though: for courts, the ‘reasonable person’ test is used to ascertain socially acceptable responses to recognisable situations (such as reaction to an aggressive threat), but it could not cover the multiplicity of personal decisions that mental capacity is meant to cover.

The ‘process’ or ‘rational reasons’ test is subtler. It requires P to demonstrate that he or she has considered the information in a rational manner, the implication being that the observer can trace a clear path in P's chain of thinking which is logically consistent. Roth et al argue that it is difficult to prove that it is defective reasoning that led to a particular decision; in practice, clinicians will follow their instincts and fall into the trap of treatment bias if the patient agrees, or assume that it is the mental disorder at fault if the patient disagrees.

Reference Grisso and AppelbaumGrisso & Appelbaum (1998) subsequently tried to refine the rational process test by insisting that to fail it there must be evidence of a direct effect of the mental disorder on this logical pathway and that P's reasoning must fail one or more standards (Box 2). Although these criteria are a brave attempt to reduce inter-observer variability, their demands mean that many decisions taken by the general population – the impulsive or the ‘gut’ instinct, for instance – might fail the rational process test. Grisso & Appelbaum concede that P should not have to delineate his or her logic in detail (in the same way that P has the right not to have to understand all the information related to a decision).

BOX 2 Standards for clinical interpretation of ‘rational process’ in decision-making

-

Problem focus – P is able to consider the relevant factors without distraction

-

Considering options – P is able to contemplate the most relevant options equally

-

Considering and imagining consequences – P is able to consider the risks and benefits of each option and their relevance to him- or herself in everyday life

-

Assessing the likelihood of consequences – P is able to assess the probability with which each of these consequences may occur

-

Evaluating consequences – P is able to weigh the consequences against his or her values

-

Deliberating – P is able to apprehend the probability and desirability of the consequences of his or her actions

Although Grisso & Appelbaum argue that appreciation is separate from reasoning, the criteria they give in Box 2 overlap substantially with their own description of the appreciation standard and it is easy to see how, in practice, the distinction between appreciation and reasoning is blurred. Similarly, it is difficult to separate the Mental Capacity Act's using and weighing standard entirely from rational process: both require a judgement of how quanta of information are valued, processed and relate to one other. Therefore, although rationality tests are meant to have been rejected in the development phase of the Mental Capacity Act, the inevitable danger is that they can creep back in when clinicians consider P's ability to use and weigh information. The decision maker's own values can affect how they perceive P's ability to weigh information. This remains the Achilles heel of the Mental Capacity Act. When judging whether P is using or weighing information correctly, clinicians must pause to consider and reflect on their own biases, particularly treatment bias. Is there any evidence that the final decision might have been influenced by the mental disorder, or is it one that P might have made if he or she were well? This may require consultation with family or carers.

Example 3

A 42-year-old woman is admitted to a ward for treatment of severe depression with suicidal ideation. The information from the community team is that she is agreeing to admission in the hope of receiving electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). However, when the ward junior doctor discusses the procedure with her, she informs the doctor that she has heard it might kill her. She explains that she is consenting to ECT not because she thinks it will make her better but because she deserves to die. The junior doctor discusses her reasoning with his consultant: although both agree that ECT is the best treatment for their patient, it is felt inappropriate to continue it on a voluntary basis and ECT is subsequently performed under the Mental Health Act.

In this case the patient has made the ‘right’ decision (a rational outcome), but for the wrong reasons (i.e. she fails to use and weigh the information appropriately), and under current legislation it would be wrong to administer ECT without a proper legal framework to protect her rights. Where P lacks mental capacity but agrees to treatment for a mental disorder, the Mental Health Act Code of Practice suggests that either the Mental Health Act could be used, or the Mental Capacity Act in conjunction with a DoLS authorisation (Department of Health 2015: ch. 13, para. 49).

Hybrid tests of mental capacity

In the Roth view of mental capacity, each of the tests outlined (expressing choice, actual understanding, ability to understand, rational outcome and rational process) is treated as a separate, alternative test. The decision maker uses whichever test they deem appropriate to the situation (Reference Roth, Meisel and LidzRoth 1977). Grisso & Appelbaum created a hybrid test which amalgamates tests of mental capacity and converts each one into a standard within an overarching test of mental capacity (Reference Grisso and AppelbaumGrisso 1998). The result is a universal test which is less vulnerable to the decision maker's choice of test and less affected by the weakness of a single test.

The standards in Grisso & Appelbaum's hybrid test are:

-

• expressing a choice – this is used as a ‘threshold’ test: if P cannot communicate a decision he or she is deemed to lack mental capacity

-

• understanding (the relevant) information – this corresponds to Roth et al's ‘ability to understand’ test

-

• appreciation

-

• reasoning – which corresponds to Roth et al's rational process test.

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool – Treatment (MacCAT-T), one of the most widely used research tools into mental capacity, is based on this hybrid model. It can be seen that, despite its popularity in the literature, the incorporation of a reasoning standard means that the MacCAT-T does not correlate directly with most mental capacity legislation in the UK.

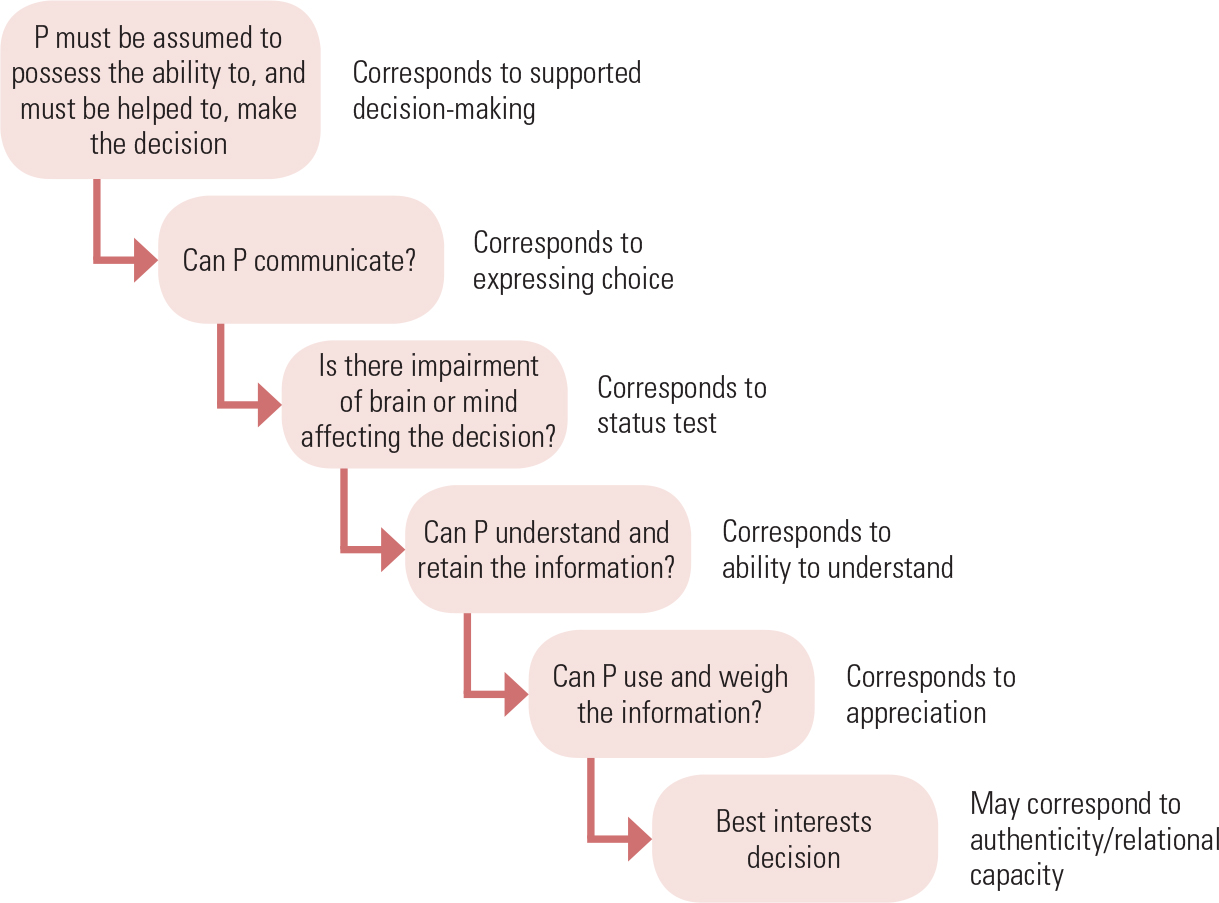

The Mental Capacity Act also uses a hybrid model. As we have seen, it incorporates not one but two threshold tests: a communication and diagnostic threshold, corresponding to expressing choice, and a status test of mental capacity. (Subsequent case law has made the diagnostic threshold a little more sophisticated, clarifying that a ‘causal nexus’ must exist between the mental impairment and the decision in hand.) The remaining tests of mental capacity, outlined in section 3 of the Act (Fig. 1), are functional in nature: ability to understand, and using and weighing. As mentioned above, functional tests are not perfect, and the hybrid nature of the Mental Capacity Act is an attempt to prevent over-reliance on one test of mental capacity alone. However, this hybrid nature is rarely made explicit; instead, the various tests are presented not as alternatives but as part of a seamless process (Fig. 2).

FIG 2 The process of assessing capacity in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 broken down into its constituent parts.

Reference Ruck Keene, Butler-Cole and AllenRuck Keene et al (2016) have published a practical guide to conducting mental capacity assessments, and detailed assessment tools to guide the assessment of mental capacity are available from the Social Care Institute for Excellence (www.scie.org.uk/mca-directory/assessingcapacity/assessmenttools.asp).

Alternative tests of capacity

There are other ways of considering mental capacity which, although not sufficient to act as tests of mental capacity in their own right, have the power to modify how we perceive mental capacity and can be used to sway difficult judgements of decision-making. These alternative views, again, are skilfully woven into the fabric of the Mental Capacity Act rather than being presented as alternatives tests.

Substituted judgement and authenticity tests

In substituted judgement a surrogate tries to anticipate what P would have wanted by assessing P's past decisions and values. It is most common for substituted judgement to be used after it has been decided that P lacks mental capacity. However, in a difficult situation where the judgement of mental capacity is in doubt, previous wishes and values may become a yardstick by which to measure or correct the decision maker's assessment of P's mental capacity. For instance, Grisso & Appelbaum recognise that some decisions might not pass scrutiny under the appreciation approach; the acid test then becomes whether the decision is consistent with P's prior beliefs and values, such as religious conviction (Reference Grisso and AppelbaumGrisso 1998).

Tests based on whether a given decision is ‘authentic’ for an individual do not have to be based on historic values: Tan and colleagues have questioned the accuracy of tests based on reasoning as a means of gauging mental capacity in a small group of patients with anorexia nervosa, arguing that the anorexia had effectively become part of their personality and many ‘passed’ the MacCAT-T despite being at serious harm from the illness (Reference Tan, Hope and StewartTan 2003). Suppose that, in Example 1, the language difficulties led to the patient very occasionally ‘acting out’, i.e. exhibiting brief periods of aggressive behaviour with spontaneous recovery, interspersed with longer periods of cooperation. There is no firm guidance in the Mental Capacity Act on what to do in such a situation, but the authenticity view would suggest that these episodes do not automatically require a change in management or legal status.

It is improbable that one would have sufficient knowledge of past wishes to cover every decision P has to make. Furthermore, although substituted judgement seems respectful of P's autonomy, problems arise in practice: recall of P's past wishes may be absent or inaccurate, and too much emphasis may be placed on a previously expressed wish (Reference Torke, Alexander and LantosTorke 2008). In other words, people must be given the right to change their minds. Nonetheless, the Mental Capacity Act allows for authenticity tests in the form of advance directives, in which an individual can select which decisions and preferences they wish to have respected, in preparation for a time when they may lose mental capacity. Best interests decisions, too, require the decision maker to at least consider prior expressed wishes and values.

The CRPD and person-centred mental capacity

It has been argued that current measures of mental capacity are based too much on cognition or prior wishes and that this is in itself discriminatory (Reference PostPost 2000). Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) demands equal rights in decision-making for those with intellectual disabilities. This means that any legal framework which seeks to partially or fully replace an individual's ability to make decisions is, in theory, legally challengeable (British Medical Association 2015). A detailed analysis of the CRPD is beyond the scope of this article, but some of the more extreme assumptions about the CRPD need to be clarified. The CRPD deals with ‘legal capacity’ – the ability of an individual to be recognised as an agent in law – and does not directly criticise functional tests of mental capacity. Nor does the CRPD claim that people with cognitive impairment are free to put themselves in harmful situations in the same way that someone with mental capacity can. Despite the ‘person-centred’ rhetoric, the CRPD actually calls for patients who struggle with decision-making to be assisted and empowered to make decisions wherever possible: this is called supported decision-making and is already a guiding principle of the Mental Capacity Act (see section 1 in Fig. 1) and most mental capacity legislation in the UK (Reference KellyKelly 2015).

Reference Martin, Michalowski and JüttenMartin and colleagues (2014) argue that to be CRPD compliant, mental capacity legislation would have to abandon any diagnostic threshold and introduce into the best interests process a presumption that the wishes of P must be followed wherever reasonably ascertainable. This chimes with the greater emphasis on autonomy that is evident in current legal thinking, but as outlined above, there is a tension here, with the need to protect vulnerable individuals. Arguably, clinicians currently do not do enough to engage in decisions patients who lack decision-making ability: this will need to change in a CRPD-compliant future (Reference KellyKelly 2015). In 2014, the Law Commission initiated a consultation exercise into DoLS legislation which acknowledged these challenges. The consultation exercise, which included a submission from the Royal College of Psychiatrists (Reference RandsRands 2016), has culminated in a final report published in March 2017 (Law Commission 2017).

Relational mental capacity

A report by the Nuffield Council on Bioethics (2009) argued for a more ‘relational’ view of autonomy and, by extension, mental capacity, suggesting that an individual's decision-making can be enhanced by the involvement of family and carers who know them. Where it is difficult to ascertain mental capacity, the Nuffield report recommends ‘joint’ (rather than supported) decision-making, and this may include some allowance for the needs of the family or carers themselves. Best interests decision-making in the Mental Capacity Act already requires the decision maker to ‘have regard’ to family wishes.

Conclusions

Table 1 summarises the tests of mental capacity and best interests decision-making approaches discussed in this article. Roth et al's tests of mental capacity remain the foundation of modern concepts of decision-making. Of these tests, functional tests based on understanding are dominant in mental capacity legislation, as they are ‘nimble’ enough to adjust to changes in P's circumstances and are considered to provide a good balance between safeguarding vulnerable individuals and respecting their autonomy. Views of mental capacity based on authenticity, relational or person-centred models provide a useful prism through which more conventional models of mental capacity may be analysed, but lack completeness as alternative tests of capacity in their own right.

TABLE 1 Summary of tests of mental capacity and approaches to best interests decision-making

A test of mental capacity based on understanding does have some inherent problems: it is reliant on the information given; P's judgement may be swayed by undue influence; and P's mental capacity under this test may fluctuate to an unreasonable extent. Finally, as discussed, the perception of P's ability to weigh the options can be a more subjective measure than proponents of such tests might be prepared to admit.

The saving grace of functional tests of mental capacity may be their ability to live alongside and draw on the best of alternative views of mental capacity. On closer inspection, the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and similar UK legislation have, embedded in them, many of the alternative tests of mental capacity one might have assumed had been rejected. These include evidencing choice, person-centred approaches and authenticity approaches.

The Mental Capacity Act avoids confusion by presenting these alternative views of mental capacity as part of best interests decision-making, leaving the functional test of mental capacity as the undisputed ‘master test’ of mental capacity under the Act. This ‘tiered’ approach reduces confusion: contrast this with the Mental Health Act 1983 (amended 2007), whose Code of Practice requires consent to treatment to be assessed by a functional test, but which is still largely based on a status test of mental capacity (Department of Health 2015).

Given the complexity of issues such as autonomy and the subjective nature of cognitive experience, it is unlikely that we will ever find an objective and uncontroversial measure of mental capacity. Despite its critics, it seems reasonable to view the functional test of mental capacity as the ‘least worst’ test, whose utility can be enhanced if clinicians take a more holistic understanding of its components. This would enable them to understand and communicate better with colleagues, patients and carers on the important ethical issue of decision-making.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Which of the following tests of mental capacity is not found in the Mental Capacity Act 2005?

-

a The functional test

-

b Rational outcomes

-

c The status test

-

d Understanding and appreciation

-

e Using and weighing.

-

-

2 In the Mental Health Act 1983, the main test used to assess mental capacity in relation to the decision to consent to admission is:

-

a the functional test

-

b rational outcomes

-

c the status test

-

d understanding and appreciation

-

e using and weighing.

-

-

3 The appreciation test of mental capacity is best defined as:

-

a P's ability to comprehend the nature of the particular conduct in question and to understand its quality and its consequences

-

b P's ability to understand the significance of the information, choices and consequences involved in the decision

-

c P's ability to understand, retain, use and weigh the information in relation to a particular decision

-

d the assumption of the presence of decision-making ability based on a proxy measure

-

e P's demonstration of a preference for an option.

-

-

4 The standard in the test of mental capacity used in the Re C court case that is not explicitly mentioned in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 is the ability to:

-

a believe the information given

-

b communicate the decision

-

c retain the information given

-

d understand the information

-

e use the information.

-

-

5 Which of the following standards for assessing mental capacity is present in the MacCAT-T but not in the Mental Capacity Act 2005?

-

a Appreciation

-

b Believing information

-

c Expressing choice

-

d Considering consequences

-

e Reasoning.

-

| 1 | b | 2 | c | 3 | b | 4 | a | 5 | e |

Acknowledgement

I am grateful to Dr Ivan Koychev for reading drafts of this article and for his helpful comments.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.