War is the search for one’s place in the world by military means. It is a way through which states define their relationship with others. The Vietnam War is no exception; it was a process in which two Vietnamese groups – the communists and the nationalists – and three major powers – the United States, China, and the Soviet Union – interacted to advance their own visions of the world and determine Vietnam’s place in it. The war ended with the emergence of the communists as the rulers of a unified Vietnam, the elimination of the nationalists as a political elite, and the termination of US intervention in Indochina. But the struggle to define Vietnam’s relationship with the world did not come to an end. The decades after the war have seen Vietnam chart a twisty trajectory in search of its place in the world. Thirteen years into the postwar period, the same Communist Party that had fought against the United States in the war now sought integration into the US-led international order. Soon, however, this effort was subordinated to an endeavor in the opposite direction. The primacy of the anti-Western direction lasted fourteen years, until Vietnam’s ruling elite clearly recognized that the United States was the paramount power in a unipolar world. In the years that followed, Vietnam accelerated its entrance into the world, and, four decades after the Vietnam War, it completed a journey from an “outpost of socialism in Southeast Asia” and a “spearhead of the world national liberation movement” to a “responsible member of the international community.”Footnote 1 In a little more than three decades, from the mid-1980s to the late 2010s, Vietnam turned from a fierce opponent into a discreet ally of the United States, while still maintaining its communist regime. This chapter will illuminate these puzzling processes. It analyzes the grand strategies of Vietnam in these decades, together with the motives, thinking, and visions behind those grand strategies, and it documents the key events that shaped Vietnam’s strategic trajectories, together with the larger contexts and developments that made those events possible.

The search for a nation’s place in the world is, metaphorically speaking, the interaction between maps and a landscape. The maps guide the search and are based on the leaders’ worldviews, which reflect their historical experiences and result from a complex process of social ideation. The landscape provides the ultimate test for the maps and is changing almost constantly. Guiding Vietnam’s search during the last four decades were two master maps – dubbed “two camps” and “single market” – that contradicted each other fundamentally. It was the struggle between followers of these maps that shaped the search, but this struggle did not occur in a vacuum: it was primarily a response to changes in the geopolitical landscape.

Vietnam’s Strategic Environment in a Long Historical Perspective

Two features that characterized the strategic environment of all states that have existed in the modern Vietnamese territory throughout history are China and the South China Sea – the former as a world center of power and civilization and a giant market, the latter as a main artery of world transportation and a fountain of wealth. During nearly two millennia, from the third century BCE, when China was unified under the Qin, until the sixteenth century CE, when Portugal and Spain respectively seized Malacca and the Philippines, China, including its regional kingdoms when it was in disunity, was the single biggest power in Vietnam’s neighborhood. Major rulers in Southeast Asia regularly sent “tributes” to the Chinese court in order to gain access to the Chinese market and receive diplomatic recognition. Vietnam, particularly its northern part, is unique in Southeast Asia for an important experience that the rest of the region has never had: Chinese rule, which lasted a millennium (111 BCE–938 CE). It owed much of its tradition, in administration, ideology, technology, scholarship, and art, to learning from China. The advent of European empires – the Portuguese, the Spanish, the Dutch, the British, and the French – eclipsed Chinese power but not China’s attraction. A key motive that drove the French conquest of Vietnam in the nineteenth century was to gain access to the backdoor of China through the Mekong River from the south and the Red River from the north in the hope of gaining an edge over the British, which policed China’s front doors.Footnote 2 In the twentieth century, the United States engaged in the Vietnam War because it wanted to contain communist influence flowing from China.

The South China Sea has always been the heart of a trade zone that connected different parts of the region as well as the final – or initial – leg of the maritime routes that linked China and the rest of Afro-Eurasia. These maritime trade routes held the key to the rise and fall of Funan, the first regional power in Southeast Asia (1st–6th centuries) and the earliest state in today’s southern Vietnam. A contemporary of Funan, Giao province of the Chinese empire, in today’s northern Vietnam, was the terminus of these maritime routes and throve on this interregional commerce. Champa, a shifting alliance of principalities along the central Vietnamese coast (3rd–17th centuries), also gained prominence and prosperity mainly from its control of the trade routes passing through the west–central domain of the South China Sea.Footnote 3 In the last half-century, the sea’s oil and gas reserves added immensely to its value for Vietnam.

The role of China and of the South China Sea changed significantly with changes in the global context. Until the sixteenth century, Southeast Asia was a “protected zone” in the rimland of the Eurasian continent – protected from the frequent attacks and long-term occupations by “nomadic” powers that roamed the steppes of central Eurasia. This distinguished Southeast Asia from the “exposed zones” such as China, India, and the Middle East, whose history was deeply shaped by Inner Asian invasions. The protected position of Southeast Asia was the reason behind some “strange parallels” between this region and Europe, another “protected zone” at the other end of Eurasia, as observed by Victor Lieberman, who coined the terms “protected zones” and “exposed rimlands” of Eurasia.Footnote 4 Beyond the gaze of Lieberman’s work, however, from the sixteenth century onward Southeast Asia became an “exposed rimland” of Eurasia, this time exposed to the conquests, interventions, and influence of the powers that ruled the waves of the world’s oceans – the European empires mentioned above, the United States, and Japan. This shift moved Southeast Asia from the “end of the world” to the front line of great-power competition. Consequently, a key element of Vietnamese statecraft changed from leveraging the frontier of an empire to navigating the politics between great powers. As a prelude to the alliances of the Vietnam War, the two warring Vietnams of the seventeenth century – the Trinh in the north and the Nguyen in the south – allied with each side of the Dutch–Portuguese rivalry to obtain military resources and diplomatic support. In both cases, an armed conflict between local groups was intricately joined with a strategic rivalry between great powers. Also in both cases, Vietnam was at the peripheries, not the center stage, of great-power competition. The fall of Saigon in 1975 did not substantially affect the final outcome of the Cold War. The United States lost the Vietnam War but won the global contest with the Soviet Union. The rise of China in the last four decades has gradually shifted Vietnam from the peripheries to the central front line of great-power competition. This front line runs through the East China Sea, the Taiwan Strait, and the South China Sea. It is in this context that communist leaders of postwar Vietnam have been navigating their ship of state and endeavoring to “anchor” Vietnam in the world.

Birds of a Feather (1975–86)

The unification of Vietnam in 1975 created a country with the combined territories and populations of North and South Vietnam. The new Vietnam was now the second most populous country in Southeast Asia. Its major natural resources included not just the coalfields of northeastern Vietnam, but also the oil and gas reserves in the South China Sea.Footnote 5 The new territory and new population provided the new country with more options for its role and position in the world. When communist troops entered the presidential palace of the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) on April 30, 1975, they replaced the flag of the fallen regime with that of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Southern Vietnam (PRG), not that of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN). Some options considered for the unified country included a two-state confederation, in which South Vietnam would have its own seat in the United Nations (UN) and stay neutral between the Cold War’s blocs, and a “one state, two systems” arrangement in which the South would maintain its own socioeconomic system. But six months into the new experience, communist leaders rejected these options, not least because they feared that the South could be manipulated by China.Footnote 6 In July 1976, North and South Vietnam were officially merged into the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRVN).

Buoyed and blinded by their defeat of what the late President Hồ Chí Minh called “two big empires” – France in 1954 and the United States in 1975 – communist leaders imposed with an iron fist their neo-Stalinist perspective upon the unified country. In their grand strategy, the central goal was socialist industrialization, and Vietnam’s place in the world – its relations with other countries and with international groupings – was a means in the service of this end. The way that related the means to the end reflected a peculiar belief that combined a neo-Stalinist worldview, Leninist pragmatism, and the pretensions of Hanoi’s self-image. Marxism-Leninism provided the larger map for determining the goal.

Following the spirit of Lenin’s dictum “communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country,” Vietnamese communists envisioned the building of socialism in their country as consisting of two major missions: to establish and maintain Communist Party rule in the whole country and to build it into an industrialized one. They regarded the military takeover of South Vietnam, which they called “liberation,” as the final step in their long march to bring the entire country under Communist Party rule. As this was completed in 1975, the paramount mission now became socialist industrialization. With Leninist pragmatism, Vietnam’s communist leaders were flexible in selecting the means, trying to take advantage of all available opportunities to achieve their goals. However, the lens through which they recognized the opportunities was a neo-Stalinist worldview that saw other countries in three categories – socialist, nationalist, and capitalist – with Vietnam squarely within the first group as an “outpost of socialism” in Southeast Asia and a “spearhead of the world’s national liberation movement.” Accordingly, Hanoi sought ideological, political, and economic relations with the socialist countries; political and economic relations with the nationalist countries; and only economic relations with the capitalist countries.Footnote 7 To capitalize on its role as a “spearhead of the national liberation movement,” it retained the former PRG’s seat in the Nonalignment Movement. Flexibly, socialist Vietnam renewed the fallen Saigon regime’s memberships in the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, which other socialist countries regarded as instruments of Western power and capitalist exploitation.Footnote 8 Hanoi also resisted Moscow’s pressure to join the Soviet-led economic bloc, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON). This positioning reflected a calculated design to obtain maximum economic aid from all over the world while navigating the Sino-Soviet split and hoping for the West’s contribution to Vietnam’s postwar reconstruction.

The end of the Vietnam War gave the victor a sense of invincibility and entitlement. When Vietnam’s central planners drafted the first postwar Five-Year Plan (1976–81), they assumed that the country would face no external security threat, that the socialist countries would maintain the level of their wartime aid to Vietnam, and that the United States would provide $3.25 billion in grant aid and $1.5 billion in commodity aid.Footnote 9 These assumptions would become increasingly ill-founded. The Khmer Rouge, with a bigger sense of invincibility, wasted no time in invading the country and killing Vietnamese citizens along the Cambodia–Vietnam border. The close of the Vietnam War removed a common cause that had forced China and the Soviet Union to compete in supporting Vietnam. After the war, both Beijing and Moscow pressured Hanoi to side with each against the other. As Hanoi refused to take sides, both substantially reduced their assistance. China additionally increased hostility along its border with Vietnam. Believing in socialist solidarity, capitalist greed, and Vietnam’s moral high ground, Hanoi held out the hopes that Cambodia and China would return to friendly terms with Vietnam as moderate factions would prevail in these countries, and a Democratic administration in the United States would resume economic aid to Vietnam. By the spring of 1977, the prospects of an anti-Vietnam Sino-Cambodian alliance loomed large, while Vietnam’s overtures to the West met with reluctance as negotiations on normalization between Hanoi and Washington stalled due to Hanoi’s insistence on war reparations. Soviet–Vietnam relations also deteriorated as Vietnam endeavored to stay outside the Soviet orbit. All these coincided with a growing economic crisis at home. Then came the Khmer Rouge’s heavy attacks into Vietnamese territory on April 30 and, again, on September 24, 1977.Footnote 10

Desperate for massive aid and nearly in a corner, Vietnam took crucial steps that it had tenaciously resisted since 1975 and agreed in principle to join COMECON at an “appropriate time.” In late May 1977, it became a member of two Soviet-sponsored international banks, and in late July a large Soviet military delegation paid an unprecedented trip to Vietnam’s military installations in the south.Footnote 11 As Vietnam’s relations with Cambodia and China turned to open hostility in late 1977, Hanoi concluded that removing the Khmer Rouge by military force was necessary to mitigate this two-front security threat. In January 1978, the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) Politburo decided to prepare for an invasion to “liberate” Cambodia and install a pro-Vietnam government.Footnote 12 As Hanoi needed insurance against the anticipated Chinese retaliation, it dusted off a Soviet proposal tabled in 1975 and, by early June, agreed to sign a “treaty of friendship and cooperation” – a mutual defense pact – with Moscow. On June 28, Vietnam formally joined COMECON, and on November 3, it officially signed a twenty-five-year friendship treaty with the Soviet Union – the best timing thought to deter Chinese military actions against Vietnam.Footnote 13

The Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia on December 25, 1978 started a new period in Vietnam’s history. On February 17, 1979, China launched a massive invasion along their land border to “teach Vietnam a lesson.” In the ensuing decade, Vietnam fought a guerrilla war in Cambodia, a punctuated war along the Sino-Vietnamese border, a deepening economic crisis at home, and an international isolation imposed by most of the world’s governments. Contrary to Hanoi’s worldview, Vietnam’s alignment reflected the great power conflict between the Soviet Union and the Sino-US coalition rather than the ideological struggle between socialism and capitalism. Vietnam’s allies were actually Soviet allies, including also “nationalist” countries such as India, Afghanistan, South Yemen, Ethiopia, Angola, and Nicaragua. The country was at war with communist China and the anti-Vietnamese Cambodian factions, mostly the Khmer Rouge, backed by communist North Korea, the United States, Thailand, and others that feared Soviet and Vietnamese influence. Firmly entrenched in the Soviet camp, Vietnam changed its constitution in 1980 to align its political, economic, and social system and its government structure more closely with those of the Soviet bloc countries. The preamble of the 1980 constitution identifies the “imperialist” United States and the “hegemonist” China as Vietnam’s two chief enemies.

Returning to the Regional Matrix (1986–2003)

Vietnam joined the Soviet bloc when the group was in a brewing crisis. Despite the East–West confrontation, the industrial countries of the East had to rely on the cooperation of the West to obtain some critically needed technology and finance. By the early 1980s, the neo-Stalinist economic model had lost most of its steam, and reform became urgent in most countries of the bloc, including the Soviet Union. The new realities of the previous decades, especially the economic decline of the socialist countries, a new wave of technological revolution, and new developments in world politics fueled in the Soviet bloc a new worldview that fundamentally challenged the neo-Stalinist outlook. The new worldview was not a monolithic system of thoughts, but an evolving “family” of similar views that had various origins. Chief among the “common traits” of this family was the understanding that the world was one, not two. If the old orthodoxy saw the antagonism between two social orders, socialism and capitalism, as the source of the most elemental dynamic of international politics, the new worldview proceeded from the interdependence of countries within a single world community, as the dominant Soviet variant underscored, or a single world market, as a prominent Vietnamese variant emphasized. After Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in March 1985, he elevated the new worldview, known as “new thinking” (novoe myshlenie), to a guiding ideology of the new Soviet domestic and foreign policy.Footnote 14

The new Soviet policy increased pressure on Vietnam to improve its economic efficiency, while signaling an end to the two-camp structure of world politics. Since the late 1970s, Vietnam had tried to reform some aspects of its economic governance, but the general deterioration was not arrested. In July 1986, the succession of Trường Chinh to the deceased Lê Duẩn as CPV General Secretary paved the way for more radical reforms and for a “renovation of thinking” (đổi mới tư duy) in major aspects of Vietnam’s domestic and foreign policy. During the years 1983–6, Chinh turned from a conservative to a reformer by “looking straight at the truth” (nhìn thẳng vào sự thật), a process pressed by burgeoning economic difficulties but primarily facilitated by his son, Đặng Xuân Kỳ, and some of his aides who were new thinkers.Footnote 15

With Chinh at the helm, the 6th Congress of the CPV in December 1986 vowed to “comprehensively reform” (đổi mới toàn diện) the country’s governance. It lifted reform (đổi mới, literally “renovation”) to the status of a grand cause similar to what unification was for the 1954–75 period. None of the subsequent congresses of the CPV demoted reform from this status, but reform ebbed and flowed as a result of the struggle between its opponents, who were plenty in the party, and its proponents, who were often in the minority.

The fates of the three leading proponents of reform, Trần Xuân Bách in politics, Võ Vӑn Kiệt in the economy, and Nguyễn Cơ Thạch in foreign policy, neatly illustrate the destinies of reform in these areas. Bach, a potential successor to party chief Nguyễn Vӑn Linh, who replaced Chinh at the 6th Congress, was purged from the CPV Central Committee in March 1990 for his advocacy of political pluralism and made a nonperson until his death in 2006. Kiệt became prime minister after the 7th CPV Congress in June 1991, but his proposals for stronger reform in the spirit of “nation and democracy” were often rejected by the conservative majority in the CPV leadership. Thạch was the architect of Politburo Resolution 13, which was later touted as laying the groundwork for Vietnam’s foreign policy in the Đổi mới (Renovation) era, but he was forced to retire to placate China in 1991 and then kept under tight security watch. His book The World in the Last 50 Years (1945–1995) and the World in the Next 25 Years (1996–2020), which outlines his worldview and the road to industrialization and modernization for Vietnam, was confiscated immediately after release shortly before his death in 1998 and only republished in 2015.

Some elements of the new thinking existed as early as 1973 in a report Thạch wrote, as a deputy foreign minister, on the economic cooperation between the Soviet bloc and the West.Footnote 16 By 1987, they had grown into a relatively coherent worldview capable of providing the theoretical underpinnings for a new grand strategy. In May 1988, despite opposition from the ministry of defense, the CPV Politburo passed Resolution 13 as the main guidance for the country’s foreign and security policy in the new situation. Titled Maintaining the Peace, Developing the Economy, it signals a return to the original aspiration of postwar Vietnam but actually represents a larger turning point in Vietnamese foreign policy, as it fundamentally broke with the worldview that had guided communist Vietnam’s international behavior since the late 1940s. Couched in the language of a struggle between socialism and capitalism, Resolution 13 is nevertheless premised on the assumptions that the world is a single system and a single market where countries big and small are interdependent and compete primarily in the economic realm. Based on this worldview, Resolution 13 outlines what can be seen as the grand strategy of Đổi mới. It states that keeping a peaceful environment in order to focus on economic development is “the highest interest of our Party and people.” Its strategic guidance includes riding the trends of “internationalization” and a “scientific-technical revolution,” finding an optimal position in the international division of labor, and expanding international cooperation to achieve a strong economy and a “strong enough” national defense.Footnote 17

The objectives and key pillars of Vietnamese foreign policy that were introduced in Resolution 13 would be confirmed at every subsequent congress of the CPV. The key pillars include “befriending all countries in the world,” “diversification” (đa dạng hóa), and “multidirectionalization” (đa phương hóa). The intent of the architects of these pillars was: to broaden international cooperation, with priority given to neighboring states, advanced industrial countries, and the major regional and global powers; to extend the concerns of foreign policy from the political and military to the economic, technological, and other aspects; and to cast a wide web of relationships with not only the socialist and traditionally friendly states, but also regional and major capitalist countries.

If the 6th CPV Congress started the Đổi mới era, the 7th Plenum of the 6th Central Committee in August 1989 marks the largest conservative turning point in the period. Fearing the prospects of regime change, at this meeting, which took place in the shadows of the Tiananmen Square protests in China (April–June 1989) and the fall from power of the Communist Party in Poland (August 1989), party chief Nguyễn Vӑn Linh vehemently criticized the new thinkers and outlined a two-camp grand strategy to protect the communist regime. This strategy called for joining hands with anti-Western forces globally and strengthening the totalitarian state at home to combat US and Western influence.Footnote 18

At the 3rd Plenum of the 7th Central Committee in June 1992, its first after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the CPV passed two resolutions to guide foreign and security policy in the post–Cold War era. While the foreign policy resolution shares the pragmatism of Resolution 13 and settles on a compromise between the “single market” and the “two camps” worldviews, the national security resolution is firmly based on the “two camps” worldview and identifies “peaceful evolution,” an imagined plot thought to be sponsored by the United States and the West to subvert the communist regime, as the central threat to Vietnam’s national security. The former resolution sets the foreign policy priority on relations with the remaining socialist countries, the regional countries in the Asia–Pacific, and the advanced industrial countries in the West, in this order. The latter resolution, however, is supplemented by a directive drafted by the anti-Western faction of President Lê Đức Anh, which instructs party cadres on the geopolitical proximity between Vietnam and foreign countries. According to this directive, Vietnam’s closest friends were the four remaining socialist countries – China, Laos, Cuba, and North Korea – plus Cambodia, where the Leninist and Vietnam-friendly Cambodia People’s Party was a coruling party, followed by the former socialist countries in Eastern Europe, where Hanoi hoped for a resurgence of communist parties, and India, a nonaligned major power most friendly to Vietnam. The directive instructs keeping the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries farther than the countries mentioned above, and keeping the United States at the farthest distance.Footnote 19

The two worldviews and their contradicting grand strategies created two divergent policy currents in post–Cold War Vietnam – the anti-Westerners and the integrationists. Their domestic struggle and the meeting of their strategies with the realities resulted in a dogged quest for a strategic alliance with China, a cautious opening to the surrounding region, and half-steps in integration with the larger world during the “long 1990s,” a period bracketed by the collapse of communist regimes in Eastern Europe in 1989 and the US invasion of Iraq in 2003.

A strategic alliance with China based on ideology was the key element of the foreign policy agenda of anti-Westerners, who dominated the highest echelons of Vietnam’s politics throughout this period. As Lê Đức Anh, then minister of defense, succinctly explained in 1990, “The United States and the West want to wipe out communism from the entire world. Clearly, they are our immediate and dangerous enemies. We have to seek an ally. This ally is China.”Footnote 20 Initiated by party chief Linh and Anh in 1990, the quest for a strategic alliance with China, although consistently met with Beijing’s rejection, was renewed by every successive General Secretary of the CPV in the “long 1990s,” from Đỗ Mười in 1991 to Lê Khả Phiêu in 1999 and Nông Đức Mạnh in 2001. What Beijing wanted with Hanoi was not an alliance, but a neo-tributary relationship. As Hanoi was far more eager than Beijing to mend their relationship, the result was an asymmetric one whose main feature was Vietnam’s deference to China. Throughout this period, party cadres in Vietnam were instructed orally that China was the strategic ally and the United States the strategic enemy.Footnote 21

A cooperative relationship with the United States and membership in ASEAN were the key elements of the integrationist agenda. These arose from the perceptions that the United States was the most technologically advanced country, the largest external market, and the political–military leader of the West, while ASEAN was the main bridge on the road to joining the world. Efforts in these directions were, however, severely torpedoed by the dominant anti-Westerners. The signing of the comprehensive US–Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement was delayed from 1999 to 2000, costing Vietnam billions of US dollars in exports, whereas the conclusion of two historic treaties to delineate the Sino-Vietnamese borders on land and in the Tonkin Gulf was hurried to meet the deadlines proposed by China, 1999 and 2000, resulting in substantial Vietnamese losses. In both cases, party chief Lê Khả Phiêu played a central role, which his opponents cited to charge him when trying to oust him, successfully, at the 9th CPV Congress in April 2001.Footnote 22 The timing of the other landmarks in Vietnam’s relations with the two major powers, the restoration of Sino-Vietnamese and US–Vietnamese relations in 1991 and 1995, respectively, reflected both the Vietnamese tilt toward China and the US approach to Vietnam. Washington stayed one or more steps behind China and ASEAN in engagement with its former enemy. It waited a week after the Chengdu Summit between Chinese and Vietnamese leaders in September 1990 to agree to talk on normalization with Hanoi, and it announced the normalization of their diplomatic relations a year after ASEAN approved Vietnam’s accession to the group.

In the spirit of Resolution 13, party chief Linh told visiting Philippine Foreign Minister Raul Manglapus in November 1988 that Vietnam was “eager to join ASEAN,” but after the fall of Eastern European communist regimes in late 1989, he reverted to his previous conviction that the world was structured as “two camps,” and saw ASEAN as a disguised Western group and a tool of “US imperialism.”Footnote 23 In the subsequent years, while integrationists such as Prime Minister Võ Vӑn Kiệt, who ranked third in the party nomenclature, and the foreign ministry leaders tried hard to join ASEAN, anti-Westerners such as party chief Đỗ Mười, President Anh, and CPV Executive Secretary Đào Duy Tùng, who ranked first, second, and fourth in the leadership, persistently braked the process. Mười and Anh only changed their minds after their respective visits to ASEAN countries in October 1993 and April 1994.Footnote 24

During the long 1990s, Vietnam pursued an asymmetric two-headed grand strategy in which international integration was subordinated to anti-Westernism. Even after it became an ASEAN member in 1995, its attitude continued to combine a larger dose of anti-Western wariness and a smaller dose of integrationist enthusiasm. Although Vietnam’s leverage of its ties with ASEAN and the United States was instrumental in forcing China to deescalate in the Kantan-III oil rig crisis of March 1997, Phiêu, who became CPV General Secretary in December 1997, preferred bilateralism in dealing with China, arguing that Vietnam would lose sovereignty if its issues in the South China Sea were multilateralized. In December 2001, two months after the US invasion of Afghanistan, party chief Nông Đức Mạnh, who replaced Phiêu at the 9th CPV Congress, agreed to “strongly condemn hegemonism by political superpowers in international affairs” in the joint statement issued on his inaugural visit to China. This was the first time ever that Hanoi publicly took Beijing’s side against another great power’s “hegemonism” – but it was also the last.Footnote 25

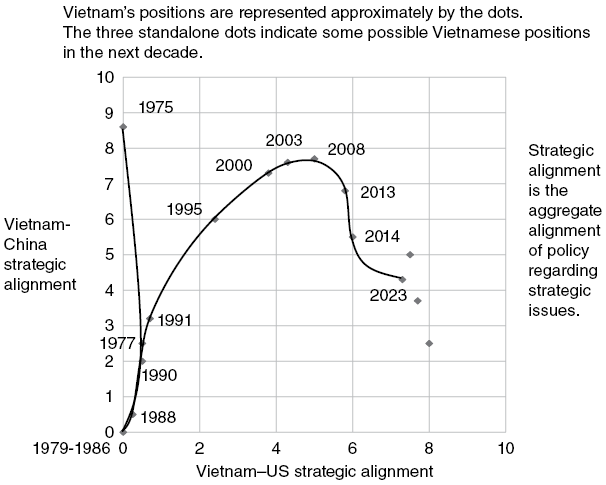

Figure 26.1 Vietnam’s strategic trajectories since 1975. The dots represent the strategic alignment of Vietnam in relation to China and the United States.

Joining the World (2003–24)

The upswing of great-power cooperation after the Cold War, Vietnam’s half-opening to the world, and the introduction of market mechanisms into the economy gradually rendered the integrationists the majority in the ruling class. But unlike the pioneer integrationists of the 1980s, who viewed international integration as a major way to modernize the country, by the late 1990s most integrationists saw it primarily as an opportunity to get rich themselves. These opportunist integrationists supported a wider opening to the world because it made available a larger source of income, but they clung to the Communist Party’s monopoly in politics because it helped them reap hyper-profits.

At its 9th Congress in April 2001, the CPV elevated economic integration with the world into a major long-term policy and vowed to turn Vietnam into an industrialized country by 2020. Its ambition was to replicate the success of the Asian Tigers – South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore – by employing the Leninist state and maintaining Communist Party rule. Yet substantial progress in joining the world had to wait until the 8th Plenum of the 9th Central Committee in July 2003.

Meeting in the aftermath of the US invasion of Iraq (March–April 2003), which vividly demonstrated the reality of a unipolar world, and with the integrationist majority in the Central Committee, the plenum adopted a new foreign and security policy guidance to replace the 1992 resolutions “in the new situation.” Jettisoning ideology as the main criterion for determining international friends and foes, its Resolution 8 marked the largest pragmatic turn in Vietnamese foreign policy since 1989. The new criteria opened the theoretical possibility for Vietnam to move to an equidistance between China and the United States, and even cross it to veer closer to the United States. Resolution 8 practically rehabilitated Resolution 13 and started a new chapter in Vietnam’s international integration.Footnote 26

Negotiations to join the World Trade Organization (WTO), initiated by Prime Minister Kiệt in 1995 but largely stalled by anti-Westerners, were accelerated as a result of Resolution 8. Unlike many other countries, which saw the WTO as little more than a global trade agreement, Vietnam regarded it as one of the most capitalist among the international institutions. Debates about the merits of joining the WTO revolved around not only the impact of lower trade barriers on domestic production, but more fundamentally whether Vietnam was willing to change the way it organized its social, political, and economic life. Symbolizing Vietnam’s full integration into the Western-led international system, its accession to the WTO in 2007 was perceived as the adoption into a new family and a “jump into the ocean.” Its WTO membership triggered a large-scale reorganization of its political and economic institutions that valued international compliance, efficiency, and transparency.Footnote 27

If the WTO epitomized Vietnam’s adopted family at the global level, ASEAN was its adopted family at the regional level. But while acceding to the WTO demanded substantial concessions, joining ASEAN required milder adjustments. By the mid-2000s, it became normal for a Vietnamese leader to call ASEAN a “family,” and by the late 2000s, ASEAN was perceived as the country’s best shelter against the vicissitudes of great-power politics; by the early 2010s, Vietnam felt so wedded to ASEAN that it aspired to play a “core role” (vai trò nòng cốt) in the group. The background of this ambition included the decision made at the 11th Congress of the CPV in January 2011 to advance as a major policy (chủ trương lớn) Vietnam’s “comprehensive integration” with the world, and the US encouragement of Vietnam’s leadership in ASEAN. The policy of comprehensive international integration implicitly acknowledged that the world was one (a single international system), not two (socialism versus capitalism). By urging full participation in the international community’s activities and compliance with the current international rules, laws, and standards, it solidified Vietnam’s new identity as an “engaged and responsible member of the international community” (thành viên tích cực và có trách nhiệm của cộng đồng quốc tế).Footnote 28 Starting in 2014, for example, Vietnam participated in the UN’s peace-keeping operations, which required a change in the constitution about the mission of the Vietnamese military. The change was made in the 2013 constitution, which was revised mainly to adapt to “comprehensive international integration.”

Following its accession to the WTO, Vietnam became an enthusiast of free-trade agreements (FTAs). Its vision was to turn Vietnam into a world crossroads and to enhance the country’s economic attractiveness by joining a large number of free-trade areas, thus making Vietnam a bridge (cầu nối) between different trade blocs. By 2011, Vietnam signed six multilateral FTAs as an ASEAN member and two bilateral FTAs with Japan and Chile. Between 2014 and 2021, it joined seven more free-trade areas, of which only two included ASEAN. With these fifteen FTAs, Vietnam became a commercial hub that connects major free-trade areas spanning from the United Kingdom and the European Union through the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union to India and all substantial economies in the Pacific basin, except the United States, Taiwan, and Colombia. In this regard, only Singapore was better positioned than Vietnam, since it had an FTA with the United States. Although Vietnam joined the negotiations on the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in 2008 at the invitation of the Bush administration, it lost an FTA with the United States when the Trump administration withdrew from the TPP in 2017.

The integrationist majority in the ruling elite and the removal of ideology as a foreign policy litmus test also spurred Vietnam to seek extensive and long-term cooperation with many countries around the world. Most prominently, it sought bilateral commitments to a strategic partnership with important regional countries and global powerhouses. Vietnam’s quest for strategic partnerships advanced in three major phases. Its first strategic partners were Asia’s major powers – Russia in 2001, India in 2007, China in 2008, and Japan in 2009. Its next strategic partners included five major advanced industrial countries – South Korea and Spain in 2009, the United Kingdom in 2010, and Germany and Italy in 2011. The rejection by France and Australia of Vietnam’s bid for a strategic partnership at that time pushed the upgrade with these countries to 2013 and 2018, respectively. In the third phase, five major ASEAN members became Vietnam’s strategic partners – Thailand, Indonesia, and Singapore in 2013, and Malaysia and the Philippines in 2015.

The strategic partnerships were the main threads of the web of partnerships that Vietnam built to maintain its security and propel its prosperity in the post–Cold War era. The top tier of this web consisted of ties with the most important countries in Vietnam’s strategic environment. By the mid-2010s, it included special strategic relationships with Laos and Cambodia, “comprehensive strategic partnerships” with China (established in 2008 with the added attribute “cooperative”), Russia (2012), and India (2016), and an “extensive strategic partnership” with Japan (2014). It tilted markedly toward non-Western powers and showed a clear deference to China, in part due to the anti-Western nature of the ideological, military, and security branches of Vietnam’s Leninist state, in part because deference to China was one of the main components of Hanoi’s approach to foreign policy – the other components being power-balancing, interlocking of interests, and enmeshment in international institutions. The glaring gap in the web was Vietnam’s ties with the United States, which sat on the third tier as just a “comprehensive partner” (2013).

The official designation of a partnership helps to codify commitment, signal the partnership’s importance, and facilitate domestic and bilateral coordination, but it is more deceptive than indicative when it comes to Vietnam’s relations with China and the United States. The year Beijing bestowed on Hanoi the mouthful epithet “comprehensive strategic cooperative partnership” – 2008 – was bracketed by Hanoi’s tacit approval, in 2007, of the first public protests against China since 1989, and a new height of Chinese harassment of Vietnamese fishermen in the South China Sea, in 2009. By the late 2010s, Vietnamese diplomats publicly noted that the US–Vietnam partnership was already “strategic” in content, albeit only “comprehensive” in name.Footnote 29

China’s growing assertiveness in the South China Sea, starting in the late 2000s, gradually pushed Hanoi farther from Beijing and closer to Washington. Hanoi moved past the equidistance line between China and the United States after China crossed Vietnam’s red line by installing a giant oil rig, the HYSY-981, inside waters that Vietnam considered its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) under international law. Seen from Vietnam nearly as an invasion, this sparked the worst crisis in Sino-Vietnamese relations since their bloody clash over the Spratly Islands in 1988. Like the Khmer Rouge’s attacks in 1977, the economic crisis in the mid-1980s, the collapse of Eastern European communist regimes in 1989, and the Iraq War in 2003, the HYSY-981 oil-rig crisis, which lasted seventy-five days in the summer of 2014, was a transformative moment in postunification Vietnamese foreign policy. It shattered trust between Vietnam and China and removed key obstacles in US–Vietnam relations. It caused Washington to lift a decades-old ban on weapons sales to Vietnam in order to aid the country in its feud with China. After these events, the two-camp worldview died out in the Vietnamese leadership, and the anti-Western policy current associated with it reached a final demise.Footnote 30 By 2018, as China stepped up its encroachment on the Vietnamese EEZ and the United States augmented its support for Vietnam’s cause in the South China Sea, Vietnam dusted off an offer that the then US Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton, had tabled in 2010 but Vietnam had resisted ever since – to raise their ties to a “strategic partnership.” As the plan went, CPV General Secretary Nguyễn Phú Trọng and US President Donald Trump would announce the upgrade at Trọng’s second visit to the White House in late 2019. However, this never materialized, owing to Trọng’s inability to travel.Footnote 31 The US–Russia hostility following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 prompted Hanoi to shelve the upgrade of its ties with Washington to demonstrate its commitment to Moscow, among others. In 2023, as Moscow was convinced of Hanoi’s loyalty, Vietnam and the United States elevated their ties to a “comprehensive strategic partnership.”

Vietnam entered a new era of great-power competition with apparent deference to China, a nonexclusive embrace of ASEAN, and a deepening but promiscuous partnership with the other major powers. This architecture was meant to be flexible, to reflect the alignment (as well as incompatibility) between Vietnam’s objectives and those of the others. During the latter half of the 2010s, a non-China tilt replaced the previous non-Western tilt of Vietnam’s web of partnerships. Hanoi paid lip service to China’s epoch-making Belt and Road Initiative, but domestic pressure has prevented the government from participating in this Chinese scheme. Also, Vietnam was one of only four Asian countries that excluded China’s Huawei from their 5G networks – the other three being Japan, Taiwan, and India. On the other hand, by late 2015 Hanoi had made major concessions on labor rights, government procurement, and state-owned enterprises, things that cut to the core of the communist regime, to join the TPP, which was later renamed the “Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership” (CPTPP) after the US withdrawal. Vietnam even doubled down on its free-trade enthusiasm and accepted the noneconomic provisions of the European Union–Vietnam Free Trade Agreement (EVFTA), which was signed in June 2019. Like the CPTPP, the EVFTA went beyond the dismantlement of tariffs and opening of markets: their noneconomic provisions were intended to enforce higher standards of human rights and environmental protection, promote Western values, and make Vietnam more attractive to Western investors.Footnote 32 As Vietnam’s strategic objectives of denying Chinese regional dominance, maintaining a nonhierarchical international order based on neutral rules in the South China Sea, and becoming a manufacturing and high-tech hub in the global supply chains dovetailed with the policies of the United States, Japan, and, to a lesser extent, South Korea and Australia, these countries were elevated to the top tier of Vietnam’s foreign relations by 2023. At the same time, Hanoi took care to nurture its leadership in ASEAN and its partnerships with Russia and the European Union to broaden its international “safety net.” Likened to bamboo by party chief Trọng in December 2021, the ideal Vietnamese approach to foreign policy should, in the eyes of Vietnamese leaders, provide resilience and flexibility in dealing with the vagaries of international relations.Footnote 33 This bamboo approach was put to a severe test when a new Cold War erupted between Russia and China on the one hand and the West on the other following Russia’s full-blown assault on Ukraine, tearing apart Vietnam’s web of partnerships with the major powers. Although the Russia–Ukraine war did not pose a direct threat to Vietnam’s quest for resources, security, and identity, it has triggered the largest transformation in the international order since the (old) Cold War’s end. With the advent of a new Cold War, Vietnam needs a new strategic “map” to replace its “single market” worldview, which is predicated on the assumptions of a bygone era.

Conclusion

Vietnam’s exposed position to Western interventions has placed the country before two long-term choices: to reject the Western-led world order and oppose Western influence or to accept the Western-led world order and adapt Western influence. The anti-Western choice, which was more heroic, emerged victorious from the First and Second Indochina Wars – the wars respectively with France and the United States. Critical factors that enabled its success included the anti-Western sentiment, a Leninist party, and the shared border with China. In a play of historical irony, the same factors were instrumental in leading Vietnam into the Third Indochina War – the war with China and the Khmer Rouge – and throwing it into the worst crisis of the postunification period. It took this war and the crisis, which consisted of an economic collapse coupled with severe international isolation, to revive the choice of integration with the world at large. But the fall of Eastern European communist regimes in 1989 strengthened Vietnam’s anti-Western choice, and the factors mentioned above played important roles again in delaying the country’s joining of the world. Eventually, it took the combination of a massive demonstration of US supremacy – the Iraq War of 2003 – and an extensive territorial dispute with China in the South China Sea to shift Vietnam decisively toward international integration.

The anti-Western choice has put Vietnam on the wrong side of history. Its adoption by the Nguyễn Dynasty in the nineteenth century was a major reason behind Vietnam’s loss of sovereignty and becoming a victim of French colonialism. In the twentieth century, it landed Vietnam on the side of the Soviet Union, the loser of the Cold War, a hegemonic competition between the world’s two superpowers. World politics is settled primarily by the strategic contest among great powers. The next instance of great-power competition is centrally the rivalry between China and the United States. Who will win this contest is a question of the future, but the hint to its answer can be found in geography and history. The geography of the Earth suggests that the dominant power of the world’s oceans has a crucial edge over its rivals in the contest for global hegemony. History also shows that none of the great powers based in the continents of Afro-Eurasia – from Persia, Rome, India, and China in the rimland of Eurasia to the Mongols and Russia in its heartland – has ever become a global hegemon. This dominant position has historically been reserved for “offshore” powers – the United Kingdom and the United States – whose location and resources enabled them to achieve mastery of our planet’s maritime domain.Footnote 34 There is no guarantee that Vietnam will not choose the wrong side of history again. But if it does not sacrifice its interests in the South China Sea, which entail a commitment to denying Chinese primacy in the region and upholding international law as opposed to China’s “nine dash line”Footnote 35 claims, it will likely land on the right side of history – for the first time in two centuries.