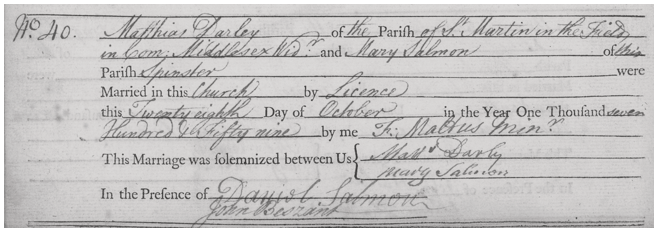

On 28 October 1759 Mary Salmon, aged twenty-three, married Matthias Darly, aged about thirty-eight, at the church of St Mary Magdalene, Bermondsey. She was the daughter of Daniel Salmon, a ferret weaver, and his wife Elizabeth. Ferrets were ribbons or tapes made of silk waste used in furnishings; according to Annabel Westman ferret weaving was a ‘poor man’s trade’.Footnote 1 Four of the Salmons’ children, aged between nine days and fourteen years, had been baptised at St Mary Magdalene on 7 July 1745; Mary’s date of birth was given in the baptismal register as 13 September 1736.Footnote 2 Bermondsey was on the southern edge of London; John Rocque’s 1747 map of London shows that Long Lane where the Salmons lived was flanked on the north side by tanneries (a noxious trade which flourished in the area until the twentieth century) but to the south were market gardens and orchards which would have made life more pleasant. Mary had obviously received at least a basic education: she signed the marriage register with a confident hand (Figure 10.1) while four of the eight brides whose marriages are recorded in the same opening signed only with a cross. The signature allows her hand to be identified plausibly on prints that she was to publish over the next two decades.

Figure 10.1 Marriage record of Matthias Darly and Mary Salmon, St Mary Magdalene, Bermondsey, 28 October 1759.

Matthias, also known as Matthew, Darly is first recorded in September 1735 as the son of the otherwise unknown Thomas Darly of the parish of St Margaret’s Westminster, apprenticed to Umfrevil Sampson in the Clockmakers’ Company;Footnote 3 he would have been about fourteen years old. From the late 1740sFootnote 4 he was working on his own account at addresses west of the City of London around St Martin’s Lane and Charing Cross.Footnote 5

His work always ranged widely: from visiting cards to wallpaper, architectural, and ornament prints, to seals in stone or metal; he also advertised lessons in drawing from early in his career. His best remembered early prints were furniture designs in Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director (1754) and architectural subjects in Isaac Ware’s A Complete Body of Architecture (1755–1757), the latter volume, like other publications at the time, produced with George Edwards.Footnote 6 The suggestion has been made that Matthias might have been responsible for furniture and architectural designs as well as prints, but there is no reason to think this.Footnote 7 In November 1749, he was one of several printsellers who underwent questioning by the legal authorities for selling prints mocking the Duke of Cumberland.Footnote 8 In his statement he mentioned his wife, perhaps referring to Elizabeth Harold whom he actually married later on 28 October 1750 at St George’s Chapel, Mayfair, where clandestine marriages took place before regulations were tightened in 1753; Elizabeth Harold/Darly is not recorded elsewhere. Matthias was clearly not discouraged from publishing further political subjects: evidence discussed in this chapter shows that the political prints that he and Mary published were inspired by conviction, not simply to follow a profitable trend.

Matthias took his freedom of the Clockmakers’ Company in 1759, some seventeen years after he would have been eligible to do so at the end of his apprenticeship. He may have taken his freedom then in order to take on apprentices himself in the Company. Ten apprentices are listed in the Clockmakers’ records as bound to him between 1760 and 1778: Barnabas Mayor, 1760; William Pettit, 1764; John Roberts, 1764; Thomas Scratchley, 1765; John Roe, 1766; William Watts, 1767; John Williams, 1768; William Wellborn, 1771; Thomas Colley, 1772; Thomas, Barrow, 1778.Footnote 9 In 1752 Matthias had paid stamp duty on the fee of £15 that was required for taking William Darling as an apprentice, presumably in some unofficial capacity.Footnote 10

Mary was working with Matthias at least two years before their marriage in 1757 when her name appears as designer and etcher (‘M. Salmon Invt et Sculp’)Footnote 11 on Caesar at New-Market, a print mocking the Duke of Cumberland’s incompetence in his conduct of the war with France. Mary’s name is certainly etched in her own hand, as is the line from the Iliad below the image. These inscriptions are carelessly placed and apparently etched hastily in contrast with the neatly placed title above and the text below, both of which were clearly the work of a trained writing engraver; similar poorly placed lettering is to be seen on a number of later prints in the hand that seems to be Mary’s. Cumberland’s rotund figure and his round featureless face derive from The Recruiting Serjeant,Footnote 12 a caricature published by Matthias in the same year after a design by George Townshend, an aristocratic young military officer who is often credited with introducing the Italian vogue for caricature – the exaggeration of physical features – to political satire in England.

Mary gave birth to their first child on 1 May 1761; three days later the baby was baptised and named after her mother at the church of St Martin in the Fields.Footnote 13 The Baptism Fees Book records the family’s address as Long Acre, the address shown on one of Matthias’s trade cards.Footnote 14 By the time the next two children, Mattina and Matthias, were born in March 1764 and February 1766 the family was resident in the adjacent parish of St Anne Soho.Footnote 15 The move is indicated by a change in the address on a trade card of ‘Darly Engraver’. An early state reads, ‘the Acorn facing Hungerford Strand’, close to St Martin’s church, where Matthias had been recorded in the mid-1750s, but the lettering is altered on a later state to ‘the Corner of Ryders Court, Cranborn Alley, near Leicester Fields’, an address in Soho.Footnote 16

Advertisements for satirical prints to be sold by Mary Darly at the Ryder’s Court address appear in the London newspapers from January 1762 to December 1763. She made it clear that the prints were not only sold at her own shop: they were ‘To be had of Mary Darly, Fun Merchant, in Ryder’s Court, Fleet-Street, and at all the Print and Ballad Merchants in London and Edinburgh. Itinerant Merchants may be served wholesale by the above Caricature Merchant at reasonable Rates.’Footnote 17 Her identity as a publisher was clearly recognised as apart from her husband’s, although Matthias is recorded at the same address. It was normal for women – wives, widows, daughters, sisters, and mothers – to be actively involved in family businesses at the time,Footnote 18 but the fact that Mary’s name is publicised as distinct from Matthias’s is striking. In the case of these early political satires, it may be that Matthias was concerned to avoid prosecution, but this cannot be the explanation for the appearance of Mary’s name as publisher on later prints and in advertisements (see below): it seems reasonable to infer that her role was parallel to that of her husband, that they ran the business in partnership.

The prints attacked the prime minister Lord Bute, and by implication the young George III, and were extraordinarily scurrilous. Their main theme was that Bute was colluding with France and Spain to arrange a peace treaty that would disadvantage Britain, but – like satirists of all periods – Mary added further insults: Bute was accused of corruptly favouring his Scottish countrymen, and it was implied that he had achieved his powerful position because he was the lover of the king’s mother, Princess Augusta. The Princess was likened to powerful women from history whose sexual appetites were believed to have threatened the state: Queen Isabella, who was said to have had her husband Edward II killed so as to take his place with her lover Roger Mortimer; Mary Queen of Scots, accused of intriguing with her lover David Rizzio;Footnote 19 or – in a contemporary example – the promiscuous Catherine of Russia who staged a coup against her husband in July 1762. Parallels are suggested between Bute and historical figures greedy for power from Sejanus who wielded influence over the Roman emperor Tiberius to Macbeth or Cardinal Wolsey. More immediately identifiable as Bute and the Princess were outsize symbols of a boot and a petticoat.

Mary took responsibility for publication of these prints: her name appears on some of them, and she advertised many in the newspapers. A comparison with her signature in the marriage register demonstrates that the writing on many prints is hers. But did she design and etch them? The style of the images and the quality of etching, especially in the writing, varies a great deal: the prints cannot all have been the work of one person. Mary had etched Caesar at New-Market in 1757 and in advertisements she describes herself as ‘Etcher and Publisher’. But the designs for her publications were the work of ‘amateurs’: she advertised in the Public Advertiser on 2 September 1762, ‘Gentlemen and Ladies may have any Sketch or Fancy of their own engraved, etched, &c, with the utmost Despatch and Secrecy’. In this Mary was following her husband: from the mid-1750s, when Matthias published prints after Townshend’s sketches, he had encouraged amateurs to provide ideas for caricatures, a ploy which did a great deal to create a market for such prints in circles where there would have been less interest in designs by professional caricaturists. Horace Walpole, always concerned with social status, gave friends small caricatures printed as cards mistakenly believing the format to have been invented by George Townshend (‘My Lady Townshend sends all her messages on the backs of these political cards’); the series of ‘political cards’ was published by Matthias and George Edwards.Footnote 20

Some prints published by Mary from Ryder’s Court were competently drawn and arranged in coherent compositions, while others were crude visualisations of simple-minded ideas. An instance of a well-planned and executed print is The Scotch Broomstick & the Female Besom, advertised in the Public Advertiser on 2 September 1762, where the relationship of Bute and the Princess is depicted in no uncertain terms. Bute flies through the air on a phallic broomstick towards the Princess’s ‘besom’, a bundle of twigs that she holds in front of her; elegant Scots couples watch the encounter with prurient interest. A week later the Public Advertiser carried an advertisement for a print that was, by contrast, clearly devised by someone with no artistic training who had presumably provided a rough sketch to be copied:

Tit for Tat, or Kiss My A[rs]e Is no Treason, etched in the O’Garthian Stile, by the Author of the Political History, from the Year 1756 to 1762, and published by Mary Darly, in Ryder’s Court, Leicester-Fields. Where may be had, complete Sets of all the new Political and Droll Prints that are within the State of Decency and true Humour.

The unknown Lady must excuse the Alteration of the Labels, as the Publisher intends to please, not to offend.Footnote 21

The suggestion is that the ‘Labels’, or speech balloons, in the original sketch by an anonymous ‘Lady’ were even more offensive than those in the print where a Spaniard, a Dutchman, and a Frenchman discuss how they must kiss Bute’s bare buttocks as he bends forward to kiss the Princess who has pulled up her skirts revealing the ‘way to favour’. To the left of the print stands William Hogarth with a painting of a boot and thistle that is to take the place of a portrait of William Pitt who had lost power and influence to Bute.

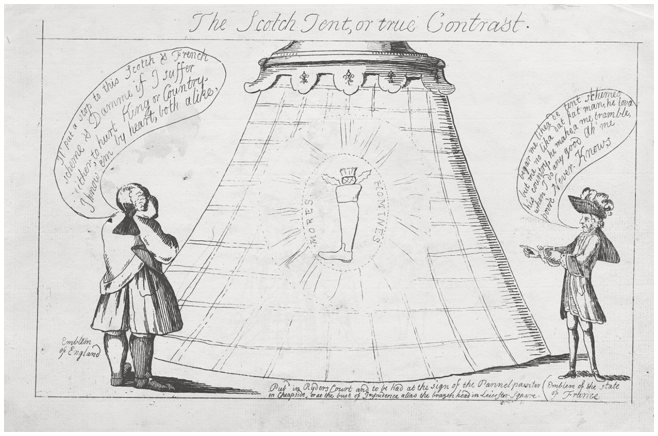

The ‘battle in prints’ extended beyond politics to the art world. William Hogarth, by then an established figure in his sixties, had come into conflict with the younger generation a few years earlier when he opposed their ambitions to found a royal academy. Mary may have been additionally provoked by Hogarth’s long-standing denigration of ‘caricatura’ as opposed to ‘character’.Footnote 22 A new assault on the older artist followed his publication on 7 September 1762 of The Times Plate 1,Footnote 23 a print supporting Bute and the king in their aim to end the war. Mary’s contribution to the attacks on Hogarth included at least three prints: Tit for Tat, described above; The Scotch TentFootnote 24 (Figure 10.2) which was lettered in Mary’s hand, ‘Pubd in Ryders Court and to be had at the sign of the Pannel painter in Cheapside [the print shop of John Smith where the sign was Hogarth’s head], or at the bust of Impudence alias the brazen head in Leicester Square [Hogarth’s home]’; and The Boot & the Block-Head,Footnote 25 where Bute’s boot is suspended from Hogarth’s ‘Line of Beauty’. It is interesting to note that Hogarth’s house was only about 300 yards from Ryder’s Court, and that Princess Augusta lived even closer at Leicester House. Mary’s market for these prints would have been the courtiers and politicians who visited both houses.

Figure 10.2 Mary Darly (publisher), The Scotch Tent, or True Contrast, 1762.

The prints, especially those attacking the Princess, must have caused serious offence. It is possible that Matthias was the ‘famous printseller’ who was indicted at Westminster Quarter Sessions in October 1762 ‘for vending in his shop divers wicked and obscene pictures tending to the corruption of youth and the common nuisance’ and, the following January, was fined £5 and bound over for good behaviour for three years.Footnote 26

Mary took a new commercial approach to caricature at this time by producing the first ‘how-to’ book in English. She advertised in the Public Advertiser on 2 October 1762:

This Day is Published, Price 4s. neatly stitched, Volume I, The Principles of Caricatura Drawing, on sixty Copper Plates, laid down in so pleasing and easy a Manner, that a young Genius may with Pleasure draw any Carick or droll Phiz in a short Time … To be had of Mary Darly, in Ryder’s Court, Cranbourne Alley, Leicester Fields; and at all the Print & Booksellers. Gentlemen & Ladies willing to have any Carick introduced, may send their Sketches as above, for the second Volume, and have them either Engrav’d, Etch’d or Dry-Needled, by their humble Servant.

This was an important change of focus. The images Mary was advocating in this little book were no longer symbols mocking well-known figures, like the round blank face of the Duke of Cumberland, Bute’s boot, or Princess Augusta’s petticoat. She was now directly addressing ‘Gentlemen & Ladies’ and providing guidelines and examples for creating humorous images:

Observe what sort of a line forms the Phiz or Carrick, you want to describe wither its straight lined, Externally circular, internally circular, or Ogeed, when you have found out the line, then take notice of the parts as to their situation, projection & sinking, then by comparing your observations with the samples in the book delineate your Carrick …Footnote 27

These principles can be seen in the innovative prints produced by the Darlys ten years later in their series of ‘Macaronies’ (see below). Meanwhile they continued opposition to government policy, supporting John Wilkes and his campaign against Bute and the peace treaty.Footnote 28 Matthias was a witness to threats on Wilkes’s life from a disgruntled Scottish soldier, Alexander Dun. His letter warning Wilkes of the danger, written on 7 December 1763, was published in the London newspapers over the next few days, and on 16 December 1763 the Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser carried the following advertisement:

This day at Noon will be published, Price 6d. The Scotch Damien;Footnote 29 a True Portrait of a Modern ASASSIN [sic] drawn from the Life at the Parliament Coffee-House, by a GENTLEMAN in Company: To be had of Mary Darly, at the Acorn, in Ryder’s-Court, Leicester Fields.

The dynamic image of the snarling Dun wielding a large knife is one of the most impressive of Mary’s publications, drawn and etched with skill.Footnote 30

The Darlys again rallied to Wilkes’s support four years later when he returned from self-exile in France. In a letter to the Gazetteer and London Daily Advertiser on 21 March 1768 Matthias, proudly declaring his status as ‘Citizen and Clockmaker’, celebrated Wilkes’s stand against general warrants and recalled how he himself had suffered under such a warrant.Footnote 31 Two months later he advertised a large mezzotint portrait of Wilkes,Footnote 32 and on 13 June he published The Scotch Victory showing the shooting of William Allen by Scots Guards in the aftermath of rioting by Wilkes’s supporters in St George’s Fields, Southwark.Footnote 33 In April 1770, Matthias marked Wilkes’s release from prison with ‘A New patriotic Song, to the Tune of Rule Britannia’.Footnote 34

By 3 August 1765 the Darlys had moved back to the parish of St Martin in the Fields: the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser advertised ‘an additional volume’ to Colen Campbell’s Vitruvius Britannicus; subscriptions were to be taken by the authors John Woolfe and James Gandon and ‘at Mr. Darly’s, Engraver, in Castle-Street, Leicester-Fields’.Footnote 35 In 1766, the Darlys moved to No. 39 Strand, on the corner of Buckingham Street, announcing the change of address in the Daily Advertiser on 24 June 1766. Their next child, William, was born on 28 August 1767 and baptised on 12 September 1767, but he lived less than five months and was buried at St Martin in the Fields on 25 January 1768. A daughter, Ann, was born on 21 March 1770 and baptised at St Martin’s on 15 April 1770.

The Darlys remained at this address for nearly fifteen years. Matthias continued, as throughout his career, to engrave and publish a wide range of material. Mary advertised the sort of cards that were essential for elite communications, advertising in the Public Advertiser on 3 April 1767:

To the Nobility. Dignified Message and Compliment Cards, so embellished that the different Degrees of Nobility are expressed in a Series of new invented Ornaments adapted to the Duke or Duchess, and down to the lesser Dignities of Peerage. The common Cards of the Shops being ornamented alike, prevents the necessary Distinction of Quality.

To be had of Mary Darly, the Inventress, at No. 39, facing New Round Court, Strand. Where nobility wanting Quantities for Routs, &c. may be served on the shortest Notice, and on the same Terms as the common printed Cards.

N.B. Ornamental Drawings made for the above Purposes in any Taste, and neatly engraved and printed. Where may be had Variety of Ornaments for Print Rooms.Footnote 36

On 13 June 1769, the Public Advertiser carried an advertisement listing the many sorts of printed material available from Matthias at 39 Strand, with an additional note indicating that Mary had found another way to attract female clients: ‘Ladies Stencils for painting Silks, Linens, Paper, &c. by Mary Darly, with the finest Colours’. Such appeals to a genteel market appeared regularly over the next few years, as well as advertisements for artists’ materials and offers of instruction for amateurs; an example in The Morning Chronicle, 4 April 1775 reads, ‘Mrs. Darly’s best respects wait on the Ladies, to inform them, that she has a new assortment of stencils, for painting silks, linen, &c. for work-bags, toilets, gowns, &c. with fine prepared colours, pencils, and every other article used in the polite arts of drawing, painting, etching, and engraving. N.B. Young ladies and gentlemen, (unacquainted with drawing) taught to paint in a few minutes.’

In the later 1760s the Darlys produced fewer political subjects, concentrating for the most part on decorative prints, but in 1771 they embarked on a venture that was to bring them great success. They returned to caricature, this time mocking individuals rather than as part of a political campaign. It was probably their association with Henry William Bunbury that opened the Darlys’ eyes to a new market for humorous prints. They had long encouraged amateurs to supply designs, but Bunbury was far more talented than most amateur artists and he had returned from a tour of France and Italy with sketches that were undoubtedly marketable: peasants, servants in coaching inns, and people – rich and poor – seen on the streets of Paris. On 1 February 1771, the Darlys published a large print based on a drawing by Bunbury entitled The Kitchen of a French Post House / La cuisine de la poste, noting in the lower margin that they also stocked ‘Mr Bunbury’s other Works’.Footnote 37

On 18 November 1771, the Darlys advertised in the Public Advertiser: ‘In a few Days will be published, the first Volume of 24 Caricatures, neatly stitched in blue Paper, by several Gentlemen, Artists, &c. &c.’ These were small caricatures of individual figures, measuring about six by four inches, sold at sixpence plain and one shilling coloured, while octavo volumes containing twenty-four prints were priced at nine shillings plain or fifteen shillings coloured. There were eventually six such volumes, published over two years.Footnote 38 From 1771 onwards the Darly prints are usually offered ‘plain’ or, at a higher price, ‘coloured’ (sometimes the term ‘illuminated’ is used). Earlier prints, such as The Recruiting Serjeant and Caesar at New-Market, had been coloured using stencilsFootnote 39 but in surviving examples from the later period a wider range of colours has been applied freehand.

The series was by far the most successful of the Darly publications and the prints survive in many impressions, often reprinted. An advertisement in the Public Advertiser, 2 November 1773, boasted that the volumes had received ‘great Encouragement … in France, and other Parts of Europe and America;Footnote 40 besides the kind Reception it has met with in Great-Britain’. One print, at least, was sent as far as China: The Stable Yard Macaroni, a caricature of the Earl of Harrington, was copied in Canton – presumably on commission – as a glass painting.Footnote 41

A number of Bunbury’s French peasants appear in the first volume of the series, but the favourite subjects were ‘Macaronies’, the term that was used for foppish young men who sported effeminate fashions and extravagant hairstyles. Title pages for Volumes II to VI read (with slight variations) Caricatures, Macaronies & Characters by Sundry Ladies Gentlemen Artists &c. Subjects range from the Duke of Grafton (A Turf-Macaroni, vol. I, no. 12) to Joseph Banks (The Fly-Catching Macaroni, vol. V, no. 11) to Christopher Pinchbeck (Pinchee, or the Bauble Macaroni, vol. V, no. 24).Footnote 42 Mary Darly herself was said to be one subject, identified by Horace Walpole in an annotation on his impression of The Female Conoiseur [sic] (vol. II, no. 7).Footnote 43 Although political subjects were avoided there are at least two exceptions that reflect the Darlys’ own views: Alexander Murray, the officer charged with the murder of supporters of John Wilkes in the riots of 1768 (The Tiger Macaroni, or Twenty More, Kill’em, vol. II, no. 2), and Robert Clive (The Madras Tyrant or the Director of Directors. JOS or the Father of Murder, Rapine &c, vol. III, no. 21).

In July 1772, around the time of the publication of the third volume, Edward Topham, a young amateur, designed a street view of 39 Strand with the title The Macaroni Print Shop; passers-by – themselves caricatured – laugh at prints displayed in the window.Footnote 44 Another view of the shop, perhaps by Matthias, shows it in 1775 under attack from William Austin, a rival caricaturist and drawing master.Footnote 45

The success of the octavo ‘Macaroni’ volumes led the Darlys over the next few years to collect their prints into quarto volumes.Footnote 46 A surviving title page, dedicated to David Garrick, has the publication line, ‘Pubd. by Mary Darly Jany. 4 1776, according to Act of Parlt. (39 Strand)’.Footnote 47 Whereas the octavo prints had been conceived as a series, these larger volumes were compilations of prints published at different dates in the 1760s and 1770s, and included small prints printed two or three to a page. In 1778 the Darlys advertised another series: twenty-six so-called Bath Cards at one guinea, coloured, ‘to be had of the print and booksellers in Bath, Bristol, and every city and town in Great Britain and Ireland’.Footnote 48

The Darlys also found a novel way to bring customers to their shop. On 28 April 1774, one column of the Public Advertiser carried three notices of exhibitions: those of the Society of Artists and of the Incorporated Society of Artists of Great Britain, and ‘Darly’s Comic Exhibition’. The two Societies and the Royal Academy had introduced art exhibitions to London in the 1760s, but the Darlys seem to be the first to hold commercial print exhibitions, anticipating those of William Holland and Samuel Fores by fifteen years or more. The advertisements published in 1774 suggest that this was their second exhibition. Admission was ‘One Shilling each Person, with a Catalogue gratis, which entitles the Bearer to any Print not exceeding One Shilling Value. This droll and amusing Collection is the Production of several Ladies and Gentlemen, Artists, &c. &c. and consists of several laughable Subjects, droll Figures, and sundry Characters, Caracatures, &c. taken at Bath, and other watering Places …’Footnote 49 Exhibitions continued for several years: the title page of a catalogue from 1778Footnote 50 states that it included ‘near five hundred paintings and drawings’; 323 items are listed of which 212 were by ‘Artists’, sixty-nine by ‘Gentlemen’ and twenty-six by ‘Ladies’.

The Morning Chronicle listed ‘distinguished personages’ who attended on the opening day in 1774, and later reported ‘the inconvenience arising … from the great concourse of the coaches of those real patrons of the polite arts, who attend [Darly’s] exhibitions …’.Footnote 51 Although such newspaper notices were doubtless puffs, the Darlys were certainly well known in London’s cultural world. In the winter of 1773 Matthias’s name appeared in newspaper articles concerning the long-running theatrical dispute between Charles Macklin and David Garrick,Footnote 52 and among many prints of actors is an etching of Garrick in his famous role as Abel Drugger in The Alchemist, lettered, ‘Mary Darly fc et ext’.Footnote 53 There are references to Darly prints in three of the period’s most successful plays: Oliver Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer (1773), Act IV, ‘I shall be laughed at over the whole town/I shall be stuck up in caricatura in all the print-shops. The Dullissimo Macaroni’; Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The Rivals (1775), Act III, ‘an’ we’ve any luck we shall see the Devon monkeyrony in all the print-shops in Bath!’; George Colman’s prologue to Garrick’s Bon Ton (1775), ‘To-night our Bayes, with bold, but careless tints, /Hits off a sketch or two, like Darly’s prints’.Footnote 54

By the late 1770s there was a new political subject: the American War. The Darlys published a number of satirical prints in a style that by then was conventional,Footnote 55 but they also produced more inventive images. The current fashion for enormous women’s hairstyles was already a subject for satire and they adapted the genre to show hairstyles illustrating events in the war. The Ipswich Journal reported on 11 May 1776 that a lady had been seen ‘with her head dressed agreeable to Darly’s caricature of a head, so enormous, as actually to contain both a plan and model of Boston, and the provincial army on Bunker’s Hill &c.’; this would have been a puff for the Darlys’ recent print, Bunkers Hill or America’s Head Dress.Footnote 56 On 24 October 1776, the Public Advertiser advertised ‘A New Head-Dress, called, Miss Carolina Sullivan, 6d plain, 1s. illuminated’. This was another caricature of an enormous hairstyle decorated with flags, tents, and cannon. Its full title, Miss Carolina Sullivan One of the Obstinate Daughters of America, 1776,Footnote 57 alludes to the unsuccessful attack by the British on Sullivan’s Island near Charleston, South Carolina on 28 June 1776. It was designed by Mattina Darly, then aged twelve, and published on 1 September 1776 by ‘Mary Darly 39 Strand’.

Other prints by Mattina include two satires on the historian Catherine Macaulay and her friend Dr Thomas Wilson both published on 1 May 1777,Footnote 58 and, according to an advertisement in the Public Advertiser on 16 June 1778, ‘Etruscan Profiles … being the Remains of a few sent sometime past to America, and is reckoned a strong Likeness of the great Earl of Chatham, the larger Size at 5s. another at 2s.6d. and an inferior Sort at 1s’.Footnote 59

A print published on 20 February 1779, Banyan Day or the Knight Befoul’d, showing the unpopular Sir Hugh Palliser being thrust into a cooking pot by disgruntled British sailors is lettered, ‘Pub by Tho[ma]s Gra[ham]. Colley at MDarly’s 39 Strand’. Colley had been bound as an apprentice to Matthias on 7 July 1772 and in 1779 he would have been barely out of his apprenticeship, but the previous October he had married Mattina, his master’s daughter, by then fourteen years old; their first child was born the following May.

By now the careers of Mary and Matthias were drawing to an end: Matthias was gravely ill. On 14 June 1779 the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser carried an advertisement for a sale to be held on 29–30 June at 39 Strand of the ‘extensive stock of prints and drawings, together with twelve hundred copper plates … also, the household furniture, fixtures and various effects, late the property of the well-known ingenious Mr Matt. Darly, Printseller. At twelve o’clock the first day will be sold, the leasehold premises, held for an unexpired term of 19 years, at a moderate rent.’ Three weeks after the sale, ‘The original Sketches from Nature, and high-finished drawings by ladies and gentlemen artists, purchased at Darly’s sale’ were exhibited at 108 Oxford Street.Footnote 60 Later states of Darly prints that carry the publication lines of other publishers would have been made from plates purchased at the sale: an example is, Mr Sharp and Mr Blunt, first published by the Darlys on 1 July 1773 but appearing with the publication line of the partnership of Robert Sayer and John Bennett at some time before 1784.Footnote 61

Matthias died of consumption on 25 January 1780.Footnote 62 However the family did not leave 39 Strand immediately after the sale. Matthias was reported to have died there, and the address continued to be recorded on prints until at least October 1780. Later in 1780 and in 1781 Mary also published a few prints from 159 Fleet Street.Footnote 63

Domestic politics were again a subject for prints with the campaign of Lord George Gordon and the Protestant Association against the relaxation of anti-Catholic laws. The Royal AssFootnote 64 which has a publication line in Mary’s hand, ‘Pub accg. to act May 20.1780. by M Darly (39) Strand’, appeared two weeks before London erupted in the violence of the Gordon Riots. In Lord Amherst on Duty,Footnote 65 published on 12 June, she attacked the lethal military response to the rioting. Amherst’s cry, ‘If I had Power, I’d kill 20 in a Hour’ echoes the caricature of Alexander Murray (‘Macaronies’, vol. II, no. 2, see above).

The fact that Mary continued to publish political prints after Matthias’s death indicates that she was as concerned with the business and with public events as her husband had been. The Darly enterprise was always a joint one. Mary’s name appears frequently in advertisements and publication lines: her role was not merely to ‘mind the shop’. The varied style of images and lettering indicates that many hands were involved in the production of the Darlys’ prints: Mary, Matthias, their apprentices, the journeymen who would have been employed from time to time, and the Darly children as they grew up.Footnote 66 It can be assumed that Matthias and his trained apprentices were skilled printmakers, but the clumsy drawing and lettering of some prints shows that they were etched by untrained hands. The 1779 sale included 1200 copperplates. Although these were not the sort of intricately engraved plates that took weeks or months to produce, the number nevertheless indicates a huge output. Many hands would have been involved in engraving and etching the run-of-the-mill decorative material that made up a large proportion of their work (see advertisements referred to above as well as Matthias’s trade cards, for instance British Museum, 2011,7084.68 and D,2.3238), while the need to produce topical subjects at speed meant that less able printmakers sometimes assisted with the production of caricatures and political prints.

The prints never approach the quality of those produced by the next generation in the 1780s and 1790s when satirical printmaking reached its apogee. However, the Darlys’ role in the development of the genre and its market was crucial. Dorothy George gave them credit as the pioneers: ‘The transition that outmoded the emblematical print and prepared the way for Gillray and Rowlandson was due chiefly to Matthew Darly and his wife. From 1770 to 1777 or 1778 they dominate the print-selling world with caricatures in the newer manner’.Footnote 67 The Darlys’ use of colour on satirical prints also heralded what was to become the norm by the mid-1790s.

In the early 1780s Mary’s circumstances declined rapidly as business collapsed. On 18 December 1783 she applied for poor relief from the parish. The official record of her application makes sad reading:

Mary Darley [sic] aged 44 years lodging at Mr. Green’s No.55 Bear Yard by Lincolns Inn Fields On her Oath saith That she is the Widow of Mathias Darley who died four years ago, That since the death of her said husband she this Examinant lived in and rented an house the corner of Newton’s Court in Round Court in the Parish of St Martin in the Fields for the space of Six months at the yearly rent of twenty four pounds besides taxes, quitted the same about one year and an half ago, That she hath not kept house rented a tenement of ten pounds by the year nor paid any Parish taxes since, That she hath one child living by her said Husband to wit Ann aged thirteen years and upwards now with this Examinant which said Ann never was bound an Apprentice nor was a yearly hired servant in any one place for twelve months together.Footnote 68

Five years later, on 23 February 1789 Mary was admitted to St Martin in the Fields workhouse where she remained until her death on 26 February 1791.Footnote 69 She was buried in the churchyard of St Martin’s on 1 March. According to Jeremy Boulton it was extremely unusual for workhouse residents to be buried there and this indicates some element of status and financial support. A fee of £1.18s.10d. was paid for the burial, as it had been for that of Matthias’s burial eleven years earlier.Footnote 70 It seems likely that Matthias junior, aged twenty-five and now in business as an engraver in nearby Chandois Street,Footnote 71 and Mattina, aged twenty-six and living with Thomas Colley and their children in Portsea, had paid for the long-term medical care that would be available to their mother in the workhouse. The cause of Mary’s death, recorded as ‘Decline’, suggests a lengthy illness.

Mattina’s will dated 6 February 1840Footnote 72 indicates that she and Thomas Colley prospered: by then widowed and living in George Street, Plymouth, she left a house near Portland Square, Plymouth, and sums of several hundred pounds each to her sons John Long Colley and Thomas Graham Colley and her daughter Mary Colley. John and Thomas junior had been established in the trade of their parents and grandparents since at least 1823 when they were recorded as ‘engravers and copperplate printers’ at 4 Union Street, Plymouth.Footnote 73

A month before her death, the prolific British print publisher Hannah Humphrey took stock of her long life and successful career. On 12 January 1818, she hired an attorney to help write her will, a document that stretched to nine pages and left generous bequests to her many nieces and nephews.Footnote 1 The attorney, or his clerk, made an error, however. In the second line of the document, he incorrectly identified Humphrey as a ‘widow’. Realising his mistake, the clerk changed this description to ‘Print Seller’, and Humphrey inscribed her initials purposefully beside the correction, preserving for posterity her professional identity.

In modern histories of print publishing in eighteenth-century London, two women – Mary Darly and Hannah Humphrey – are routinely recognised for their achievements in graphic culture.Footnote 2 While these two publishers made significant contributions to the development of eighteenth-century British prints, they were not the only women to do so. Between 1740 and 1800, no fewer than twelve women in London independently managed businesses that published or retailed prints: Elizabeth Bartlet Bakewell (c. 1710–1770), Ann Harper Bryer (c. 1745–c. 1795), Elizabeth Lyfe d’Achery (1754–after 1783), Mary Salmon Darly (1736–1791), Elizabeth Griffin (c. 1706–1752), Hannah Humphrey (1750–1818), Dorothy Clapham Mercier (before 1720–after 1768), Hester Griffin Jackson Pulley (1727–1784), Mary Brown Ryland (c. 1737–c. 1814), Mary Baker Overton Sayer (1713–1752), Susanna Sledge (c. 1726–after 1790), and Susanna Parker Vivares (1734–1792).

Women’s labour and contributions to the print publishing industry, however, are all too frequently hidden in plain sight beneath the names of their male relatives. This chapter contributes to the volume’s recovery efforts by surveying aspects of the lives and careers of these twelve women, who stand as a representative sample of a much larger total number.Footnote 3 Some acted as publishers of prints, working directly with designers, engravers, and printers to coordinate all aspects of the production and wholesale of new prints. Others worked solely as printsellers and focused their businesses strictly retailing new and old prints alike. Spread across two generations, they form a disparate group in terms of their origins, means of entry into the field, aesthetic interests, political beliefs, duration and scale of their firms, and widely varying levels of success. When viewed together, their biographical details offer general conclusions about the experience of working within the print industry while female in eighteenth-century London.

Entering the Industry

As a group, the twelve print publishers and retailers surveyed here participated in broad trends that occurred within the print publishing industry between the 1740s and 1790s. One of these concerns location. The earliest publishers and retailers within the sample – Bakewell, Sayer, Griffin, and Pulley – inherited firms that their families had established prior to the 1750s within the boundaries of the City of London. Beginning in the 1760s, print publishers located their new firms in the borough of Westminster, to the west of the city, rather than in London proper, the so-called Square Mile. Westminster was viewed as safer and healthier, with newly built housing stock. It also enjoyed a reputation for being more modern and fashionable, as the site of the Royal Academy, theatres, and many artists’ studios. But women who worked as print publishers – as well as those in other professions – had an additional reason for moving out of the Square Mile. They were not required to join a livery company or guild to run their businesses in the borough of Westminster, as the statutes of the City of London specified. Women were not prohibited from joining companies or serving seven-year apprenticeships under the tutelage of a master craftsperson.Footnote 4 In practice, however, their presence was vanishingly small during the first half of the eighteenth century: as Amy Louise Erickson has calculated, only one per cent of all apprentices were female.Footnote 5

The group of women print publishers and retailers follows this estimate. None of them is known to have undertaken a formal apprenticeship within a livery company. Instead, Bakewell, Bryer, Darly, Griffin, Mercier, Pulley, Ryland, Sayer, and Vivares – or seventy-five per cent of the group – followed the most common path for both men and women seeking to begin a trade in eighteenth-century London and entered the profession through family connections. Nearly all inherited their husbands’ publishing firms upon becoming widows. They were then faced with a decision among several courses of action: would they sell, employ someone else to run the business for them, or run it themselves? As their biographies demonstrate, the last choice remained popular across two generations. The ease with which these women carried on or expanded their families’ businesses suggests that their involvement in the operation of the firms had not begun with their widowhood.Footnote 6 Instead, they most likely had participated substantially in aspects of the creation, production, and distribution of their publications, even before their names appeared in copyright lines on their prints. They commissioned designs from artists, hired engravers to produce copperplates, determined the number of prints per edition, decided when to print new editions and when to retire worn-out copperplates, and coordinated the advertising, sales, and shipping of the prints.

The two earliest publishers among the sample exemplify this trajectory. Elizabeth Bartlet (c. 1710–1770) had arrived in London from Buckinghamshire by 1732, when she married the print publisher Thomas Bakewell (1704–1749).Footnote 7 Two years later, in 1734, Mary Baker (1713–1752) moved to London from the English Midlands to join her two older sisters. At age twenty-one, she married 53-year-old Philip Overton (c. 1681–1745), a widower who ran a large print publishing firm and who also happened to be her brother-in-law.Footnote 8 Professional networks linked the Bakewells and Overtons. The two print-publishing families had been neighbours on Fleet Street in the 1730s, and they carried a similarly diverse stock of printed materials, with maps, landscapes, and mezzotint portraits of royalty and nobility forming the core of their output.

Both Mary Overton and Elizabeth Bakewell assisted their husbands in the management of their print shops for a decade, learning the principles of publishing and selling prints through direct experience. When their husbands died within a few years of each other in the 1740s, their widows assumed control of the respective families’ firms. Though the women’s time at the helms of their businesses ultimately proved to be short-lived, they achieved success publishing under their own names. Five months after her husband’s death, Elizabeth Bakewell advertised that catalogues could ‘be had at Mrs. Bakewell’s Print Shop in Cornhill …’Footnote 9 She also replaced his name with her own on their trade card and continued selling prints at a rapid clip on her own from 1749 until 1758.Footnote 10 In late May 1758, she placed the first advertisement in partnership with Henry Parker.Footnote 11 The pair continued running their business jointly until 1763, when she sold the firm to Parker and retired.Footnote 12 When she wrote her will on 4 August 1766, she was living on Gracechurch Street, in the parish of St Benet, London. She died on 9 September 1770, at ‘her house on Royal Hill, Greenwich’.Footnote 13

Arguably the most significant print that Bakewell published under her own name was the portrait of Hendrick Theyanoguin (1692–1755), titled The Brave Old Hendrick, the Great Sachem or Chief of the Mohawk Indians.Footnote 14 The only known depiction of the Haudenosaunee leader, this etching was most likely published between 1754, when Theyanoguin played a critical role in maintaining balance of power in North America at the start of the Seven Years’ War, and 1756, shortly after his death at the Battle of Lake George. The specificity of the tattoos and scarring on the sitter’s face suggests this print might have been an accurate, factual portrait and not simply an invented compilation of Native and European clothing and accessories befitting a British ally. However unlikely this claim to veracity might appear, if the portrait was either taken from life or based on first-hand descriptions, it would reveal Elizabeth Bakewell’s position within a network of sources of information, which was aided by the location of her print shop near the Royal Exchange, a hub of North American colonial trade. And even if the portrait was entirely spurious, its publication nonetheless demonstrates Bakewell’s ongoing engagement with imperial politics.

Mary Overton also kept up a rapid pace of business following her husband’s death in February 1745.Footnote 15 She made frequent purchases from the art dealer Arthur Pond and placed no fewer than 85 newspaper advertisements for publications within a span of three years.Footnote 16 She also issued new prints and maps under her own name that responded to current events. For instance, Overton became the sole publisher of a portrait of William IV, Prince of Orange (1711–1751), just weeks after he was named Stadtholder of the United Provinces of the Netherlands.Footnote 17 Overton’s mezzotint bore the prince’s new title and was described, in newspaper advertisements she placed, as being ‘done from an original, painted at the Hague and just brought’ to London.Footnote 18 William IV had married into the British royal family fourteen years earlier. He was, however, of particular interest to Overton’s clientele in 1747 for being named the leader of one of Britain’s closest allies during the War of the Austrian Succession.Footnote 19

In 1747, Mary Overton remarried.Footnote 20 Her second husband, the attorney James Sayer, had a younger brother in search of a career. Mary Baker Overton Sayer introduced Robert Sayer (1726–1794) to the business as they worked alongside each other in her print shop on Fleet Street. But within a year, Mary’s name ceased to be included in any advertisements for what had now fully become Robert’s shop.Footnote 21 Had Mary grown tired of the daily demands and the pressure to make a profit? Or did her husband believe his wife should not be involved directly in a trade? Whatever the reason, Mary ceded her business to her new brother-in-law, under whose management it grew into one of London’s largest publishing firms for the next five decades.

Surviving the Industry

The twelve publishers and retailers surveyed here span two generations, or roughly 100 years. When compared with the numbers of known male print publishers and retailers who worked in London during the same time, this sample represents approximately ten per cent of the total industry. That figure is undoubtedly too low since, as economic historian Amy Louise Erickson argues, ‘the great majority of wives in eighteenth-century London continued to work in the labour force after marriage’.Footnote 22 It also does not take into consideration the very real roles that working-class women played in many aspects of the print publishing and selling industry. For example, the publisher Charles Mosley described in the 1740s that his ‘business of print selling was carried on by his servant maid & that he does not concern himself therein’.Footnote 23 Instead, it prioritizes women of greater economic means. Most of the publishers and retailers discussed here either came from the middling class or above or achieved that status through marriage. Simply put, it required a significant amount of capital to manage a successful publishing firm. At least three women in the group – Sledge, d’Achery, and Humphrey – opened their own firms following the receipt of bequests from deceased relatives. While specific details about the education of these women publishers are not yet known, they were most likely all literate, given the demands of their businesses and the skills required for their management.

Becoming a publisher of prints demanded a large outlay of capital upfront in order to undertake the production of prints. Working as a retailer of prints, however, required a significantly smaller investment. The tragic fate of the Griffin family of publishers underscores the financial uncertainty inherent in running a printselling business at a small scale. Peter Griffin (1726–1749) commissioned a trade card to celebrate the establishment of his own publishing firm on Fleet Street, issuing prints, maps, and books of designs, following the completion of his apprenticeship to Philip Overton.Footnote 24 When Peter died three year later, his mother Elizabeth Griffin (c. 1706–1752) replaced his name with her own on the trade card as she continued to run the business until 1752.Footnote 25 Her daughter Hester Griffin (1727–1784) married the engraver Michael Jackson in 1750; his was the next name to appear on the trade card’s plate as he issued prints of his own design from the Griffin print shop.Footnote 26 He probably died by 1763, when Hester Griffin Jackson placed an advertisement, in which she described herself as a ‘printseller’.Footnote 27 Finally, Hester remarried in 1763 to George Pulley, who then replaced Jackson’s name with his own on the trade card.Footnote 28 The story of its plate ends here – Hester and George Pulley seem to have stopped selling prints after 1766. While no prints survive that Hester published under her own name, women’s labour in family businesses was often subsumed under other names – in this case, first her brother’s, then her mother’s, and then her two husbands’. The tragic end to this story emphasizes the precarity of selling prints at the low end of the market. How Hester Griffin Jackson Pulley spent her next two decades is currently unknown, but in April 1784, she was interviewed in the St Martin in the Fields Pauper Examinations and sentenced to the workhouse, where she died two days later.Footnote 29

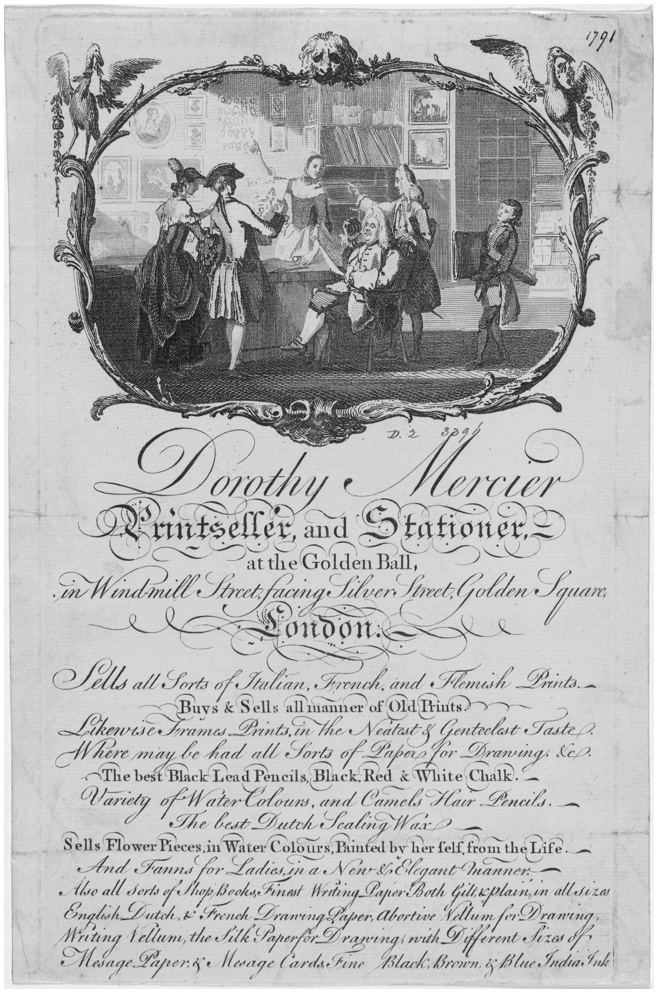

Although Dorothy Clapham Mercier (before 1720–after 1768) did not inherit a business from a family member, her path into the industry was facilitated by her connections within artistic circles. Following the death of her husband, the artist Philippe Mercier (1691–1760), she sought a means of supporting herself and her family. In 1762, she began advertising as a stationer and printseller.Footnote 30 Her remarkable trade card (Figure 11.1) offers a glimpse of her profession: Mercier stands in the midst of print connoisseurs, who peer closely at the sheets they hold and gesture to works that adorn the walls and fill the shelves. She confidently oversees a comfortable environment where civilized men and women of taste can gather – a version of Gersaint’s shop if Watteau had been transplanted to London. The lower half of the trade card lists Mercier’s diverse stock, including ‘flower pieces, in water colours, painted by herself from the Life’. In 1761, she exhibited four miniatures and two watercolours at the annual exhibition of the Society of Artists, and in 1764, she became their official stationer.Footnote 31 However, after a promising six-year career, she ceased to rent her property in Golden Square, Piccadilly, and disappears from the historical record after 1768.Footnote 32

Figure 11.1 Trade card of Dorothy Mercier, c. 1762–1764.

Specialising in the Industry

The print publishing industry experienced significant shifts between the 1740s and 1790s. By 1752, the field had begun to expand significantly, leading one writer to claim hyperbolically that printselling ‘was formerly an inconsiderable business, and very few got their bread by it. But some ingenious persons have of late so greatly extended it, that there are at present almost as many print-shops as there are bakers in this metropolis.’Footnote 33 As the number of firms grew and diversified, so too did their publishing strategies. Many older businesses, such as those overseen by Bakewell and Sayer, offered many genres of prints, maps, and books at a wide range of price points and relied on the variety of their stock to make a profit. Unlike these larger firms, most newcomers to the industry after the 1770s developed a particular corner of the market in which they specialised. For some, this tactic meant specialising in a particular medium, from mezzotints to etchings or stipple engravings. Others invested in specific designers and engravers – Samuel Hieronymus Grimm, James Gillray, or even themselves – who achieved prominence in innovative genres or styles.

The seven publishers in this final group – Darly, Sledge, Ryland, Bryer, Vivares, d’Achery, and Humphrey – issued their prints between 1750 and 1800 from addresses across Westminster, from the Strand to Soho, Covent Garden, and Piccadilly. As the print publishing field grew in numbers, the strategy of specialising also offered a greater variety of paths for entering the industry. Women wishing to publish prints were certainly aided by having family members already within the field. But entry was gradually becoming slightly more porous and open to those attempting to forge their way on a rare, but not impossible, venture.

Though Mary Salmon Darly (1736–1791) managed her print publishing business for a decade after her husband’s death, her entry into the field did not resemble the established pattern for widows. Instead, she entered as an artist herself. The daughter of a silk weaver, Salmon was born in Southwark, London in 1736.Footnote 34 The etching Caesar at New-Market may contain a clue about how she met the engraver and publisher Matthias Darly (1721–1780).Footnote 35 He had started his career as an engraver and print publisher in the 1750s, engraving nearly 100 plates for Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman’s and Cabinet Maker’s Director. In 1757, he turned to publishing single sheet prints, issuing a series of etchings critiquing the actions of British politicians during the Seven Years’ War. These prints represent a landmark in the history of caricature in England, for they were the first time that the exaggeration of facial features was fused with political satire. The engraver of Caesar at New-Market – probably Mary Salmon herself – signed the design: ‘M. Salmon Invt et Sculp’. Whether this caricature came before or after Mary’s and Matthias’s initial meeting, the two printmakers married in 1759 and worked fully as partners as their innovations catalysed the rapid growth of eighteenth-century British caricature.Footnote 36 In 1762, Mary produced a guide for leisured women who wished to produce caricatures; a decade later, the Darlys published multiple sets of so-called Macaroni prints, which inspired a new, lasting genre of social caricature.Footnote 37

A connection with an artist paved the way for Susanna Sledge (c. 1726–after 1790) to take up print publishing. She was born in Piccadilly in c. 1726 to Susanna and Thomas Sledge, who described himself as a gentleman.Footnote 38 Little currently is known about the details of Sledge’s life prior to 1768. In that year, the Swiss watercolour painter Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (1733–1794) immigrated to London and began to rent a room from Sledge.Footnote 39 Working in collaboration with the artist, she started publishing prints after Grimm’s caricatures, quickly becoming known for these so-called mezzotint drolls. Together, between 1771 and 1774, artist and publisher issued at least six drolls, comic mezzotints ridiculing men and women’s pretensions to fashion, that established Grimm as one of the genre’s greatest practitioners.

Though Sledge’s entry into the business of print publishing might have been facilitated by her connection to Grimm, her impact on the field was not limited to their collaborations. When the fad for drolls began to wane in the mid-1770s, Sledge turned her attention to another popular subject: prints after recent portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds and George Romney. This corner of the print publishing industry was significantly more competitive, but Sledge succeeded, perhaps due at least in part to her connections within artistic circles. From 1775 to 1779, she worked with British engraver William Dickinson and Austrian printmaker Johann Jacobé to issue seven mezzotints after recent portraits. Most significant among this number was the first print taken after Reynolds’s portrait Omai, scraped by Jacobé and published in 1777.Footnote 40 The previous year at the Royal Academy, Reynolds had exhibited his painting of the Polynesian sitter, who had caused a sensation in London society. By 1780, Sledge (or perhaps Jacobé himself) had sold the mezzotint plate to John Boydell (1720–1804), who had come to dominate the field of reproductive prints after modern paintings.Footnote 41

During the 1770s, and perhaps beyond, Sledge also created profile portraits in pastel and silhouette.Footnote 42 By the 1780s, her involvement in actively issuing new prints seems to have faded. Her house and shop at No. 1 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, however, remained a neighbourhood hub. She rented rooms to artists Laurence J. Cossé, T. Goodman, Richard Crosse, and William Wellings, continued to advertise medicinal and hair products for sale, and hosted the harpsichordist Mr. E. Light, who ran an evening academy out of her shop.Footnote 43 Sledge’s longest tenant was Samuel Hieronymus Grimm, who continued to live with her until at least 1790, when he named her an heir in his will ‘as a grateful acknowledgement for the friendly care she always took of me’.Footnote 44

By the 1770s, the novel technique of stipple engraving, introduced in England by William Wynne Ryland (1733–1783), had risen to challenge the popularity of the mezzotint.Footnote 45 Within the next two decades, his widow, Mary Brown Ryland (c. 1737–c. 1814), Ann Harper Bryer (c. 1745–c. 1795), and Susanna Parker Vivares (1734–1792) devoted their print-publishing businesses to specialising in this reproductive print medium. Each woman had followed the most traditional means of entering the field. Following the deaths of their husbands – print publisher Henry Bryer and engraver-publishers Ryland and François Vivares – between 1778 and 1783, the three widows started to publish and sell prints under their own names. Their businesses had much in common, including their locations near one another in Soho. Early in their independent management, both Vivares and Ryland published line engravings made by their husbands.Footnote 46 But their firms were soon dominated by stipple engravings, primarily by Francesco Bartolozzi, after designs by Angelika Kauffmann and Giovanni Battista Ciprani, among others. Vivares established the largest, most ambitious firm of the three, publishing at least thirty prints between 1781 and 1797. Bryer published about ten known prints between 1779 and 1789, while Ryland achieved a similar output slightly later, from 1786 and 1799.

Though Bryer’s and Ryland’s endeavours were more modest in scale, their publications frequently were not. Ryland, for instance, published a stipple engraving after Kauffmann’s seminal neoclassical painting Cornelia, Mother of the Gracchi in 1788.Footnote 47 Painted in Naples in 1785 for Kauffmann’s greatest patron, George Bowles, Cornelia achieved fame when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy the following year.Footnote 48 To this ambitious print by Bartolozzi, Ryland added a dedication to her ‘much obliged Friend’ Sarah Trimmer (1741–1810), a noted educational reformer, philanthropist, and author and critic of children’s literature. This choice was apt in many ways. It reinforced Kauffmann’s celebration of a mother’s accomplishments as a teacher by linking the painting to Trimmer’s name and simultaneously demonstrated Ryland’s connections within London society.

Finally, during their short and long careers, respectively, Elizabeth Lyfe d’Achery (1754–after 1783) and Hannah Humphrey (1750–1818) both specialised in wildly inventive, frequently biting satires that addressed current political and social subjects.Footnote 49 These etchings came principally, though not exclusively, from the needles of James Gillray and Thomas Rowlandson. D’Achery’s career as a print publisher made up for in impact and intensity what it lacked in length. Born in 1754 in Surrey as Elizabeth Lyfe, she had arrived in London by at least 1773.Footnote 50 There she encountered Nicholas d’Achery, a French citizen who worked in London as a ‘master of languages’, with whom she had a daughter in 1774. Though they never married, upon his death in 1777, he named her co-executor of his estate and left a generous bequest in his will to support her and their daughter.Footnote 51 Between 1782 and 1784, she published at least fifty political caricatures, including such iconic images as Britannia’s Assassination (1782) by Gillray and The Devonshire (1784) by Rowlandson.Footnote 52 She also published many caricatures after anonymous submissions. In a 1783 advertisement, she expressed gratitude ‘to the gentleman who sent the drawing of the Wheelbarrow, which was immediately put in the hands of an engraver’, and for ‘the drawing of the Coalition of Parties, which will be published tomorrow’. She noted with disapproval, however, that ‘the design sent on Tuesday is too indecent for the publisher’s shop’.Footnote 53

If d’Achery had one of the shortest but most consequential careers as a publisher of prints, Hannah Humphrey had one of the longest and most substantial. She gained her introduction to the print publishing industry through her extended family. She was baptized in 1750 in the parish of St John, Wapping Street in east London, where her father, George Humphrey, listed his profession as a grocer.Footnote 54 In 1754, he moved his family to the more affluent parish of St Martin in the Fields. Hannah’s older brother William entered the field of print publishing first, establishing his own firm in the early 1770s.Footnote 55 In 1778, at age twenty-eight, Hannah established her own independent publishing firm, funded perhaps by a bequest she received in the same year from her recently deceased father.Footnote 56 William and Hannah Humphrey ran their businesses simultaneously for nearly a decade, during which time they published prints by a series of artists who ushered in a new era of graphic satire, spearheaded by the contributions of James Gillray (1756–1815). Upon William’s retirement, Gillray began to work exclusively for Hannah. From 1791 to 1815, she issued 650 prints by the artist – or two-thirds of his total output – establishing both of their reputations. By investing in Gillray, as well as Thomas Rowlandson and George Cruikshank, Humphrey built her print publishing firm into one of the most influential tastemakers in London with an international reputation.

In conclusion, between 1740 and 1800, these twelve women print publishers and retailers contributed hundreds of images that circulated throughout London’s visual economy. Some were explicitly political or artistically ambitious, leaving a lasting mark on the history of print publishing. Others fought to survive in a crowded, competitive field. As a group, the heterogeneity of their experiences defies any easy or essentializing characterisations. Ranging from the renowned to the completely unknown, these women’s experiences reveal changes over time within the print publishing industry across different generations and economic classes, and how they took advantage of the expanded access and opportunities. Reconstructing their histories demonstrates women’s ongoing contributions to the business of publishing and selling prints in eighteenth-century London.

I beg you will accept my thanks, for sending me, the enclosed proof, which I have carefully perused. I am sorry to say, that through the whole work, misrepresentation, and error, abounds. It would require a book, to refute, all the Mistakes, that is contained in the work, as well, as Catalogue.–I can only say. As it is not in my power to prevent such Error’s being published [it] is entirely against my Consent.

Jane Hogarth was clearly a formidable adversary – a force to be reckoned with. These words penned in response to John Nichols’s proof for his Biographical Anecdotes written about her husband, the painter and engraver William Hogarth, give a strong idea of her polite yet firm character.Footnote 1 Jane was in her seventies when, in defence of William’s reputation as well as her own, she denounced Nichols’s account with such ease and thoroughness, leaving the author in no doubt that she had ‘carefully perused’ his work. Nichols’s Biographical Anecdotes was published in 1781, the year after Horace Walpole published his own account of Hogarth in his Anecdotes of Painting in England.Footnote 2 According to Walpole, Jane was not pleased with his anecdotes either.Footnote 3

Neither Walpole nor Nichols say much about Jane, the only daughter of the history and decorative painter Sir James Thornhill.Footnote 4 Her mother, Lady Judith Thornhill, receives equivalent treatment, as not much is known about her apart from the obvious fact that she was also married to a celebrated artist. When acknowledged at all, nineteenth-century commentators describe Jane as a mere widow rather than the strong businesswoman she proved to be.Footnote 5 Her vehement objections to Nichols’s biography demonstrate how she strove to protect her husband’s reputation; but she also resolved to safeguard her property – something she achieved through copyright law by obtaining a unique extension to the coverage period of her husband’s prints.

Remarkably, only twice in the history of English copyright has Parliament made an exception to the applicable copyright term: in 1988 when the copyrights to Peter Pan were secured in perpetuity to the Great Ormond Street Hospital, and more than 200 years earlier, in 1767, when Parliament gave Jane Hogarth a twenty-year exclusive right to her husband’s works. Why has this noteworthy achievement mostly been ignored? How did an eighteenth-century woman printseller and widow obtain such a provision and a tailored copyright law? Jane’s involvement with the mechanics of the parliamentary system prompts one to ask if others proceeded in similar ways to protect and defend their property. It turns out that another woman, Elizabeth Blackwell, also set an important milestone in copyright history when, seeking to protect her botanical prints, her case became the first to be tried under the Engravers’ Act of 1735.Footnote 6

This chapter explores the tactics Jane Hogarth employed in managing and protecting the family printselling business throughout years of forceful competition, including her unique copyright extension. A look into satirical prints by contemporaries leads one to hypothesise on her importance and her influence over William as well as on her level of involvement in running the business while he was still alive. This said, could Jane’s apparent clout have aided her in obtaining favourable treatment in the face of the law after his death? What distinguishes her from other women printsellers of this period, and to what extent was her situation determined by William Hogarth’s renown?

Business ‘As Usual’ and A New Venture

Following William’s death on 26 October 1764, Jane took control of the printselling business with the help of her cousin Mary Lewis and William’s sister Ann. As William did, Jane opted to sell the prints herself at their dwelling house in Leicester Fields. On 31 January 1765, she reinforces the sense that it was business ‘as usual’: ‘The WORKS of Mr. HOGARTH, in separate Prints or complete Sets, may be had, as usual, at his late Dwelling house, the Golden Head, in Leicester Fields; and NO WHERE ELSE.’Footnote 7

Jane rapidly took the helm and carried on with the daily commercial tasks, indicating both a proficiency with the print business and the self-assurance required to compete within it. She was appointed executrix of her husband’s estate and the principal beneficiary of his property, which included the copperplates.Footnote 8 The bequest stipulated that Jane could not sell these ‘without the consent’ of her sister-in-law Ann and, should his widow remarry, William instructed that the three popular series, Marriage A-la-Mode, A Harlot’s Progress and A Rake’s Progress, ‘shall be Delivered to my said Sister’.Footnote 9 As part of her duties, she was also required to pay Ann an annuity of £80 out of the sale of the prints, in quarterly payments, and the sum of £100 to Jane’s cousin Mary Lewis. Jane never remarried during her long and active life and supported herself from the plates; after Ann’s death in 1771, decisions pertaining to them passed entirely into Jane’s hands.

Many other widows continued to run the family business after their husband’s death. Like Jane Hogarth, Anne Fisher, widow of the mezzotinter Edward Fisher, sold her late husband’s works and lived in Leicester Fields in the 1760s. Contemporaries, Mary Brown Ryland and Elizabeth Bartlet Bakewell, widows of the engravers William Wynne Ryland and Thomas Bakewell, each continued to run their husband’s print business as well.Footnote 10 Bakewell’s trade card indicates that she was a ‘Map & Printseller’ in Cornhill, London, and reveals that she sold ‘all sorts of Maps & Prints for Exportation’ in addition to offering paintings in oil and on glass, and services such as the making of frames.Footnote 11 It was hard to gain a commercial reputation in the highly competitive London print trade and many business owners relied on a diversity of offerings; their stocks included a variety of prints, maps, books, and even remedies.Footnote 12 Importantly, Jane did not resort to selling other such items and focused solely on generating revenue from William’s engravings, but false claims and speculations by her ruthless adversaries compounded difficulties at home and abroad. In 1767, for example, an advertisement in the Boston News-Letter erroneously states in a sensationalist tone: ‘Hogarth’s Prints: at present very scarce, and encreasing [sic] in value every Day: that celebrated Artist having destroyed the Copper Plates some Time before his Death.’Footnote 13 The plates were Jane’s most valuable possession and had not been ‘destroyed’; in fact, Jane went on selling Hogarth’s reprints for twenty-five years after his death.

In the mid 1760s, Jane was seeking new opportunities and agreed to enter into a business partnership with the Reverend John Trusler (1735–1820). The aim was to produce an edition of Hogarth’s works and exploit the moral and didactic content of the prints. This was announced with Jane’s name specifically mentioned and the involvement of ‘a Gentleman’ (presumably Trusler) in the Public Advertiser (31 July 1766); but a description in the Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser (27 May 1765) of a similar undertaking with prints explained and bearing the name Hogarth Moralized suggests that Trusler may have begun the project without her.

The Registry of the Stationers’ Company shows two entries for Hogarth Moralized under Mrs Hogarth and Dr Trusler – on 6 August 1766 ‘for their Property Hogarth Moralized’ and on 4 October 1766 ‘for their copy Hogarth Moralized Sheet D’ – and reveals that on each occasion nine copies were received, but it is not known what these consisted of.Footnote 14 Advertisements in the London newspapers indicate that the freshly engraved prints on a smaller scale were published first in single numbers and later offered as a bound whole.Footnote 15 These were to be had at Mrs Hogarth (Leicester-Fields) as well as M. Hingeston (in the Strand), J. Dodsley (Pall-mall), W. Shropshire (New Bond Street), R. Smith (Holborn), T. Snelling (Fleet-Street), Corbould and Dent (Ball-Alley), S. Hooper (the Strand), and H. Parker (Cornhill), and one advertisement even claimed that they were sold ‘by all Book and Print sellers in Great-Britain’ but made clear that the originals were to be had at Mrs Hogarth’s house.Footnote 16 Undoubtedly, two different market segments were targeted: one from the distribution across Great Britain of Hogarth Moralized priced ‘within the reach of common buyers’; the other from the exclusive sale of William’s collection of fine prints, costing a much higher thirteen guineas and sought after by collectors.Footnote 17

The partnership eventually came to an impasse. Trusler’s unscrupulous practices may have worried Jane; after all, Hogarth’s father had been exploited by publishers, which eventually led to his financial woes, something that neither William nor Jane wanted to repeat.Footnote 18 Further, Trusler’s strong conservative views on women’s roles prompts reflection on how he regarded Jane as an independent businesswoman, especially given that they disagreed on financial matters and on commercial risk and strategy.Footnote 19 When Trusler wanted to expand Hogarth Moralized into other countries, Jane did not agree to ‘follow [him] in a French edition, and having the plates on a larger scale at Paris’.Footnote 20 Presumably, this is because she would have lost control over operations and dealt with a different set of laws in France; however, Jane did not have an aversion to fulfilling international sales. She advertises in the London Chronicle (31 January–2 February 1765) that ‘Commissions from abroad will be carefully executed’.Footnote 21

In the end, Jane acquired full ownership of Hogarth Moralized thus keeping the rights to the letterpress and the plates.Footnote 22 Nichols claims that the transaction ‘amounted to at least 700l [pounds]’, indicating that Jane had sufficient means to buy Trusler’s share.Footnote 23 Her financial ease is highlighted in a letter from an unknown lodger,Footnote 24 and Bank of England ledgers from August 1766 to February 1771 show that she owned a type of government stock known as £3% Consols.Footnote 25 Jane was prosperous enough to keep two households (until her death) and renovate her Chiswick house by adding a kitchen wing and a large dining room. She also continued an annual subscription of half a guinea to the parish school.Footnote 26

An ‘Exclusive Right’

In the mid-1760s, despite her financial stability, Jane Hogarth had been losing considerable income to the sellers of spurious and pirated editions; this not only inflicted ‘a cruel Invasion of her Property, but a great Injury to the Reputation of her late Husband’, as claimed in her advertisements.Footnote 27 At the time, some prints were still under copyright protection but those from the 1730s and 1740s were no longer covered because the Engravers’ Act of 1735, which had been the result of William Hogarth’s efforts to prevent the piracy of his works, provided protection for a term of fourteen years from the date of first publication and this period had now elapsed.Footnote 28

Jane worked in collaboration with the Society of Artists of Great Britain in putting a bill before Parliament intended to better secure the rights of artists. She received the support of John Gwynn, a Society Director, who insisted that

Mr. Hogarth’s works will be always valued and admired, and therefore ought to be as much the property of his widow, as if their value had been laid out in the purchase of an estate, of which it is to be presumed no one could possibly have deprived her, and yet this lady has been compelled to inform the world that her property has been invaded.Footnote 29

These words recognised the unique appeal of Hogarth’s works (which were now hers) while addressing the complexities of the intangible nature of copyright as property. Such difficulties began with the 1735 Act itself which, as pointed out by Mark Rose, was ‘the earliest explicit recognition of the immateriality of the commodity created by intellectual property law’.Footnote 30 The so-called Hogarth Act had proven of limited use. To remedy its inadequacies, the Society’s bill proposed to broaden the scope and duration of copyright protection. It also included a note stating that ‘Mrs Hogarth must petition before a clause can be inserted in her favour’.Footnote 31 She complied, and her petition claims that her

chief Support arises from the Sale of her late Husband’s Works; and that, since his Decease, many Persons have copied, printed, and published, several of those Works, and still continue to do so; and that the Sale of these spurious Copies, both at Home and for Exportation, has already been a great Prejudice to the Petitioner; and, unless timely prevented, will deprive her of her chief Support and Dependence.Footnote 32

Her efforts paid off and the bill, supported by Jane’s connections to influential people such as the American statesman, Benjamin Franklin, received Royal Assent on 29 June 1767.Footnote 33 She was given ‘the sole right and liberty of printing and reprinting all the said prints, etchings, and engravings, of the design and invention of the said William Hogarth, for and during the term of twenty years’.Footnote 34 The Act made clear that, from 1 January 1767, Jane Hogarth would have the sole right to all the prints; therefore, protection applied even to the prints for which the coverage period had already ended and were published as early as 1735, effectively reviving the expired copyrights. The Act also prolonged the duration of copyright protection from fourteen to twenty-eight years.Footnote 35 Thus, at this time, engravers enjoyed a longer period of protection than that granted to authors of literary works, which consisted of fourteen years in the first instance, and an extra fourteen years if the author were still alive.Footnote 36