Introduction

EU-induced policies in response to the post 2008 global crisis, entailing welfare state entrenchment, flexibilisation of employment relations and de-centralisation of industrial relations have invigorated critique of the demise of ‘social Europe’.Footnote 1 This demise is also viewed as one of the causes of the Union’s potential disintegration.Footnote 2 Indeed, in the last few years the EU has failed to improve working and living conditions for the majority of its population,Footnote 3 in spite of a slow upward trend.Footnote 4

This contradicts the EU’s normative aspirations. These hark back to its origins as European Economic Community (EEC, 1957), which pursued the Common Market in order to promote an ‘accelerated raising of the standard of living’,Footnote 5 relying on the intensification of social interaction as a base for enhanced economic and ultimately human cooperation.Footnote 6 Today’s EU continues to pursue these aims alongside an expanded catalogue of objectives: established for the sake of ‘elimination of barriers that divide Europe’ (Preamble TEU) and the ‘promotion of peace (...) and the well-being of (...) peoples’ (Article 3(1) TEU), it aims at an ever closer union of peoples, not of states, underlining that the Union serves societies, not polities. Its goals combine freedom and solidarity with ecological and socio-economic sustainability (Article 3 TEU). While committed to establishing an internal market (Article 26 TFEU), the Treaty envisages the social market economy (Article 3(3) TEU) among others as an instrument for continuing improvement of living standards EU.Footnote 7 If integration of markets is legitimised by the overarching aim of promoting economic and social progress (Article 3(1) TEU), the EU’s practical failure at improving working and living standards for its citizens epitomises a normative crisis with constitutional dimensions.

This article is part of a larger legal-constitutional academic project developing ways to close the gap between the EU’s normative commitments to socio-economic justice and the practical workings of its integration project. If the EU is to regain social legitimacy while continuing economic integration, it must pursue economic and social integration at European and national levels as an interconnected endeavour. Accordingly, law and politics of social integration (‘social Europe’) will have to attain a veritable EU dimension. To realise this aim, EU level legislation, non-legislative governance and adjudication will have to change, and those changes will have to address shortcomings in the Internal MarketFootnote 8 as well as in the Economic and Monetary Union.Footnote 9

This article focuses on the changes required in the Court’s case law, if the EU is to achieve an EU level dimension of ‘social Europe’ as an intrinsic element of its Internal Market. It argues that after the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (the EU Charter), the EU Internal Market is constitutionally conditioned by social rights as well as by the economic rights guaranteed in the Charter. Instead of conceptualising the relation between those two types of rights as one of contradiction, the constitutionally conditioned Internal Market promotes economic integration, defined as the merging of markets at a transnational level, while respecting and promoting the entire range of EU Charter rights, thus also promoting social integration, which enables citizens to govern their own lives by ensuring sufficient means for surviving and partaking in their polity’s cultural and social achievements. Footnote 10 This approach challenges two alternatives propositions: that the EU is predominantly determined by an economic constitution,Footnote 11 and that the EU constitution is wholly neutral towards different models of economic and social integration.Footnote 12 While the argument moves deliberately within the framework of the existing Treaties,Footnote 13 this is not intended to cast doubt on the value of Treaty reform.

The article first presents the conventional perception of the Internal Market’s challenges for ‘social Europe’ as a three-pronged conceptual matrix of conflicts and tensions. Subsequently, the concept of constitutionally conditioning as an alternative to juxtaposing EU economic integration and social policy is developed, with a focus on rights guarantees contained in the EU Charter. In an ultimate step, the practical potential of the concept is demonstrated by devising an alternative path for judicial decisions taken in the Court’s so-called Laval quartet and the recent AGET Iraklis case.

The EU Internal Market challenges and social rights

A conceptual matrix

The critique of the EU Internal Market’s impact on social policy seems deceptively simple at first sight: constitutionalisation of economic freedoms and competition law initiates a vicious circle: litigation by individual parties or the EU CommissionFootnote 14 may result in judicial findings of inapplicability of social policy measures at national level on grounds of an infringement of EU economic freedoms or competition law. Replacing any such social policy measures at EU levels is encumbered by the complexity of achieving political agreement in a Union of nearly 30 Member States, resulting in a structural imbalance in favour of economic integrationFootnote 15 and the incapacity of the EU to become a social market economy.Footnote 16

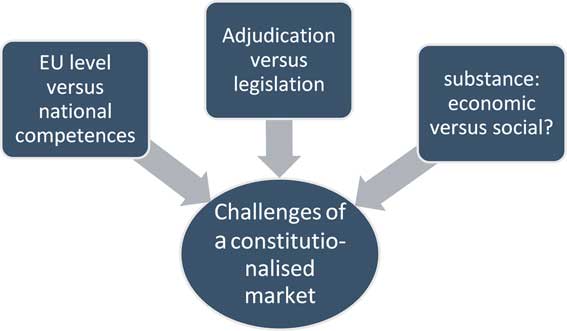

Upon closer inspection, the constitutionalisation of transnational economic integration through direct effect and supremacy of economic freedoms and competition law requires a complex analysis in three dimensions. First, market constitutionalisation can be presented as conflicts between national and EU competences for regulation and/or adjudication. Second, adjudication of (social) policy is perceived as a potentially illegitimate limitation of the democratic legislative process. Third, there is a potential tension in substance between the Internal Market and social policy. All three dimensions influence each other as visualised in the conceptual matrix portrayed below, and further discussed in the remainder of this section.

EU level versus national competences: the demise and resurrection of embedded liberalism

EU level versus national competences: the demise and resurrection of embedded liberalism

There is little doubt that direct effect and supremacy of the legal guarantees of economic freedoms and competition law effectively constitutionalised the Internal Market at EU level.Footnote 17 Decisions on whether and how far to implement the four freedoms have been moved from the national to the supranational level. Nevertheless, the founders of the European Economic Community (EEC, 1957) did not perceive economic integration as isolated from national law and policy. Economic liberalisation at Community level was coupled with national autonomy in the field of social policy. To achieve its overall aims, the EEC depended on sufficient degrees of social integration at national levels, while not offering any legal guarantee to this effect.

This model was congruent with ‘embedded liberalism’, as empirically observed and normatively envisioned by John Ruggie:Footnote 18 liberalisation of markets beyond national borders should be contained by national ‘intervention’Footnote 19 aiming, among others, at ‘social protection’.Footnote 20 Ruggie’s original model presupposed state cooperation with the aim of maintaining the potential for intervention while enabling global trade through agreeing on legal instruments. Changes in international economic law and politics initiated the demise of embedded liberalism as a global model.Footnote 21 Accordingly, Abdelal and Ruggie now demand that international organisations should not promote capital liberalisation, but continue to burden national governments with the responsibility of ensuring the social legitimacy of global capitalism.Footnote 22

Constitutionalisation of the EU level rules on the Internal Market challenged embedded liberalism EU style:Footnote 23 once the Court had established a broad notion of the economic freedoms, according to which free movement of goods, freedom of establishment and freedom to provide services could be restricted by any rule (or practice) making economic activities across a border less economically attractive, swathes of national law and policy potentially qualified as restrictions. The economic freedoms could be read as providing scope for Member States to fulfil the national part of the embedded liberalism compromise.Footnote 24 However, the Court of Justice required that national law and policy are justified, while the deregulatory thrust of the economic freedoms had to be accepted without any justification. As far as embedded liberalism was practised within the EU, it lost its equilibrium through this case law.

Parts of the literature decry the demise of embedded liberalism, and devise ways to re-establish its regime. For example, MulderFootnote 25 promotes responsive adjudication, which should safeguard national social policy against overly-intrusive European Court of Justice case law promoting economic integration. This is based on the conceptual doubt of whether links between citizens beyond national borders are sufficiently close to legitimise redistribution.Footnote 26 Inevitably Member States and the EU itself share responsibility for the overall social legitimacy of the EU as a composite polity. Thus, the social compromises found at national levels deserve protection until such time as a European level compromise has been established.Footnote 27 However, relocating the responsibility for social policy to Member States alone would also mean to reinforce the decoupling of economic integration at EU level from social integration at national levels. That same decoupling has been identified as a risk for maintaining the European Social Model early in the 2000s.Footnote 28 Thus, it is highly unlikely that reinstating embedded liberalism, as it was observed in the 1980s, in a more elaborate form is suitable for re-establishing the EU’s social legitimacy in the 21st century.

The Achilles’ Heel of the remaining defenders of the constitutionalised Internal Market in the absence of EU level constitutional guarantees of social rights is the declining capacity of nation states to provide the complementary social policy needed to maintain the social legitimacy of economic integration. It has been argued that the constitutionalised Internal Market itself, and even more so Economic and Monetary Union, endanger this very capacity.Footnote 29 The social embedding of EU economic integration cannot be provided by nation states alone. This consideration gains relevance ever more with the increasing divergence of economies and societies in EU Member States which again is enhanced by EU enlargements and the operation of Economic and Monetary Union. States governing a weaker economy, having lower tax (or other state) revenue and limited regulatory power would not be able to guarantee levels of social integration that would be sufficient to maintain the EU’s aim of constituting a transnational economy in socially responsible ways.Footnote 30 Also, European economic integration going beyond mere state cooperation, as envisaged by traditional international law, has now been in operation for more than 60 years. This has engendered truly transnational economic structures, in which national borders become increasingly irrelevant for business activity. This again means that business is beyond the reach of national social law and policy because the Internal Market increases the ease with which it moves from one regulatory regime to another. As a consequence, if the social embedding of the EU Internal Market is to succeed, it needs to be established at the EU level, where this market is constitutionalised.

Adjudication versus legislation – a limited perspective

The critique of the EU’s imbalanced integration between economic and social realms also constitutes a critique of its Court and its legitimate role. A focus on the disproportionate power of judges in adjudicating the Internal MarketFootnote 31 has led some authors to suggest that direct effects and supremacy of EU law should no longer be recognisedFootnote 32 or that there should be an EU level mechanism for Member States to challenge contentious rulings by the Court of Justice.Footnote 33 While some of these authors demand protection of Member States’ authority (including for social policy) from the European Court of Justice’s adjudication,Footnote 34 the prioritisation of legislation over adjudication is not necessarily linked to a preference for national social policymaking. For example, Grimm promotes a mixed model, demanding that the economic freedoms and competition law are removed from the EU Treaties, to allow changes through the ordinary EU legislative process.Footnote 35 This proposal aims at empowering democratic process at national as well as at EU levels, hoping that this will result in meaningful social integration measures. Vouching for EU level social policy beyond the judicial arena, Sacha Garben promotes changing the EU Treaties to reduce the economic freedoms to mere bans of discrimination, allowing for EU level legislation re-balancing ‘the market’ and ‘the social’.Footnote 36

These positions question the current state of the EU as a constitutional democracy, where legislators at national and EU levels are bound by judicially enforceable rights, protected by a strong constitutional court and not open for amendment by simple parliamentary democracy. Constitutional democracy in European national constitutions was first motivated by the aim to avoid a repetition of the Holocaust’s atrocities, and later by the human rights deficits behind the proverbial iron curtain.Footnote 37 The classical justification of constitutional democracy developed by Ely for nation statesFootnote 38 rests on the need to safeguard the interests of minorities which will be at a structural disadvantage in a majoritarian democracy.

This justification is enhanced through the increasing trans-nationalisation of economies and societies which the EU Internal Market aims to engender. The diversity of a polity such as the EU with nearly 30 Member States does not offer a dense web of social relations that could mitigate the exclusionary tendencies of majoritarian democracies, adding a further argument in favour of juridification. Jo Weiler was one of the first to submit that national legislators and constitutional adjudication may well neglect the interests of non-national EU citizens necessitating specific protection by the European Court of Justice.Footnote 39 Judicial control as a complementary way of governance retains a significant role in protecting citizens against national bias as well as majoritarian bias at EU level.

In the EU, whose constitutionalised Internal Market enables transnational market exchange defying national legislation, citizens also need protection against regulatory power by economic actors. While a treatise of the multiple emanations of rulemaking by commercial and non-commercial non-state actors is beyond the scope of this article,Footnote 40 it is worthwhile underlining the potential offered by judicial rights protection to challenge rules made by non-state actors. The European Court of Justice’s doctrine of horizontal effects of economic freedoms has this potential and can thus enhance the constitutional legitimacy of the Internal Market.

Recognising a strong role for a constitutional court also necessitates recognising its political role. Adjudication, especially constitutional adjudication, of necessity goes beyond deriving the one possible answer to a legal question from the positive law,Footnote 41 even though it rests on legal hermeneutics instead of parliamentary discourse. This is reflected in the practice of many courts – continental and otherwise – to allow for minority opinions. Judicial discourse can change, is open to constant challenge, and change should not be viewed as a weakness. On the contrary, the deliberative character of constitutional adjudicationFootnote 42 is a precondition for its legitimacy as one element of democratic governance in complex polities and societies, and indeed of the legitimacy of judicial governance in the EU polity.Footnote 43 Therefore, any court cannot but be a political and social actor in deciding which aspects of an indeterminate norm it allows to prevail.Footnote 44

Accordingly, the Court’s case law will need to be challenged politically as well as academically. The conditions for the case law to change include an attentive public sphere which takes note of the Court’s direction and subjects it to the scrutiny of public discourse, thus enabling the Court to become responsive to the citizenry. This discourse must respect the judicial function, which is to interpret the positive law, and bring it into line with the requirements of justice. Academic legal discourse is an important element of this scrutiny. It is in this spirit that an alternative path for the Court to follow is developed below.

Substance: economic versus social?

The substantive prong of the critique sketched aboveFootnote 45 focuses on the bias of the EU integration project towards a specific economic model, with structural bias against sustaining social values at EU, transnational or national levels. This critique focuses on the ECJ’s jurisprudence on economic freedoms and competition law, the provisions forming the core of the EU’s economic constitution.

Briefly summarised,Footnote 46 the critique asserts that the Court of Justice, by reading the economic freedoms as bans on restricting transnational economic activity as well as transnational trade, classifies any measure rendering the exercise of one of the economic freedoms in another Member State less attractive than the exercise of the same freedom at a mere national level as a restriction of an economic freedom. A restriction does not necessarily constitute an infringement, as it can be justified. While defining the substantive reach of economic freedoms ever more widely, the Court has also expanded the options to justify a restriction beyond those positively enshrined in the Treaty. Any mandatory requirement in the public interest can justify a restriction, as long as the restriction is proportionate to achieve this aim. The jurisprudence on the economic freedoms has wavered between merely enforcing economic freedoms across borders and promoting economic liberty independently of its trans-border character. Recent case law has shown a tendency to become more lenient on the requirement of transnationality, for example in assuming a limitation of cross-border trade in goods if the use of a good is restricted, for example through a ban of using watercrafts on non-commercial waterways or towing trailers behind motorcycles.Footnote 47 If the Court defends not only cross-border economic activity, but the use of market freedoms more widely, it may be accused of lending constitutional authority to one particular approach to economic policy, often portrayed as the basis of ordo-liberal thought.Footnote 48 A wide scope of application for economic freedoms bases the EU economic constitution on economic liberties for entrepreneurs. This narrow perspective is arguably contested within the Treaties, which provide for planned production and price regimes in the agricultural policy, protect EU internal production through a common customs tariff and promote substantive investment through the common transport policy as well as industrial policies.Footnote 49

In the field of EU competition law, the Court shares authority with the EU Commission as EU competition authority. The Commission’s official role here comprises issuing guidelines, and enforcing competition rules such as the prohibition of cartels, of the abuse of a dominant market position or of state aid. The Court and the national courts can be seized not only to challenge the actions of national and EU competition authorities, but also in order to invalidate legislation and challenge behaviour of non-state actors deemed, by European Court of Justice standards, to be economic actors. Again, the competition rules can be interpreted as mainly aimed at protecting the Internal Market from the practices of private economic actors; or more principled as ordaining competitive markets as a principle of organising societies. The Court and the EU Commission have charted a contradictory course in both regards, and this course still awaits a thorough theorisation from critical perspectives on economic and social integration.Footnote 50 Accordingly, the principles of the constitutionally conditioned Internal Market will be developed in relation to economic freedoms below, leaving a thorough discussion of EU competition law for a different occasion.

The Court’s prevailing interpretation of economic freedoms veers towards an economic constitution prioritising the individual rights of economic actors. By placing justifications in the public interest systematically on the proverbial back foot, it also is intrusive on social integration measures. While the process may lead to accepting national social policy choices, more frequently these are invalidated or stymied.Footnote 51 Case law on economic freedoms is not limited to controlling legislation. Instead, the direct horizontal effect of economic freedoms also allows judicial review of market actors’ rules.

Considering the current case law from a legal-realist perspective, Tuori stresses that EU Internal Market law constitutes a strong economic constitution, which is co-original with the European integration project.Footnote 52 This seems to render other constitutional layers of the EU edifice, including the social constitution, less powerful. Kilpatrick and de Witte even portray the economic and the social constitution as mutually exclusive, suggesting that one will be victorious over the other eventually.Footnote 53 For some authors, the layered presentation of the EU’s constitution constitutes the starting point for a critique of EU law and policies, predicting doom for the European integration project because it fails to achieve its promises of improving Europe’s societies.Footnote 54 These strands of substantive critique, in all their diversity, juxtapose the Internal Market as part of the EU’s economic constitution to the demands of other constitutional principles at EU level.

This juxtaposition risks overlooking contradictions and opportunities to drive forward an interpretation of internal market law that would support the social embedding of EU constitutional law not only through national legislation, but at the EU level itself.

Beyond the impasse

In order to overcome the EU’s normative impasse as sketched initially, it is necessary to move beyond juxtaposing the EU’s economic constitution on the one hand and its social values on the other. This substantive starting point will invite confusing the protection of Member States’ sovereignty with the pursuit of social policy within the European Union. This again neglects the potential for protecting and promoting social rights at EU level, which again is a precondition of overcoming the stated imbalance between the EU’s economic and social constitution.

The Treaties and their predecessors themselves have never merely juxtaposed pure economic integration with other forms of integration. Instead, they combine free movement of goods and services, as well as competition rules with guarantees of free movement of persons and capital. By guaranteeing free movement of persons, especially of workers, under the condition of equal treatment alongside economic freedoms for producers and service providers, the EU’s unique socio-economic model of regional integration holds out the promise of participative inclusion.

Accordingly, the much criticised European Court of Justice case law also is inconsistent. For example, the horizontal effect of economic freedoms has contradictory effects: it may protect weaker parties such as free-moving workers from discrimination by employers, but may also be utilised by those in a position of economic power, such as the members of the Swedish building sector employers’ association, against the claims of workers posted to Sweden.Footnote 55

The ambiguous character of EU constitutional law does not merely suggest that the EU constitution refrains from determining a certain model of economic integration.Footnote 56 Going beyond this, it is necessary and possible to derive a normative frame supporting rather than obstructing the social embedding of market constitutionalisation at EU level.Footnote 57 The concept of constitutionally conditioning the Internal Market ensures that constitutionalisation through rights guarantees can provide a basis for strengthening ‘social Europe’. When the European Court of Justice’s case law eventually changes to embrace this concept, this will also facilitate legislative projects such as implementing the European Pillar of Social Rights.Footnote 58

Constitutionally conditioned Internal Market: enhancing social rights effectively

In developing the constitutionally conditioned Internal Market, this section first introduces the concept, and subsequently argues that a purposive interpretation of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights points to constitutional conditioning as its normative demand.

Constitutional conditioning – the concept

The notion of a constitutionally conditioned market is inspired by the Polanyian idea that markets, if based on unlimited liberties, risk endangering society and thus their own basis.Footnote 59 Polanyi predicted that societies would eventually produce counter-movements to contain the destructive tendencies of pure egotism,Footnote 60 describing this process by the term ‘embedding’, whose often criticised imprecisionFootnote 61 invited re-interpretation. Ruggie’s embedded liberalismFootnote 62 constituted such a re-interpretation, in that it proposed embedding global economic integration through national institutions. The implicit decoupling of trade liberalisation (at international levels) from social integration (at national levels) constitutes this model’s central weakness.

Sharing the principle that trade is conditional upon respecting social constitutions, the concept of ‘constitutional conditioning’ proposes to overcome this weakness by demanding a re-embedding of the EU Internal Market through legal guarantees at EU levels. For a society to survive, competitiveness is not sufficient. Competitiveness does nothing to engender cooperation, which is the vital basis for societies. Nevertheless, markets are not only social constructs, but also constitute spheres of interaction between people. Such market cooperation harbours the potential to further social cohesion, as has been recognised by the EEC’s founding idea of utilising market-based cooperation to gradually bring the people of Europe closer together. Harking back to European classics of political sociology, the dichotomy between Weberian and Durkheimian (Parsonian) approachesFootnote 63 allows theorising the conditions of social cohesion through market integration in the EU: the former demands a certain degree of homogeneity for societies to integrate, while the latter relies on solidarity derived from performing distinct roles in diverse societies. Only the latter version allows a positive vision of ‘unity in diversity’, which is the EU’s motto.

However, solidarity based on a market-based division of labour is not an automatic process. It requires a civilising frame,Footnote 64 embedding economically motivated interaction and thus facilitating social integration. Such a frame can be engendered through rules and ultimately law.Footnote 65 Comprehensive notions of human rights are well suited to function as a civilising frame for markets. They safeguard the ability of citizens to self-govern their lives, which of course pre-supposes cooperation with and respecting the rights of others. This means that human rights should offer protection against overbearing regulation by states or the EU as well as by overbearing private actors.Footnote 66 Read in this way, human rights become preconditions for markets, constituting them, and their protection cannot be interpreted as a limitation or restriction of markets.

The EU integration project, based on the progressive expansion of economic integration as an instrument to achieve an ever closer union of peoples, can only remain politically sustainable if its Internal Market is embedded in such a civilising frame. The next section argues that the EU, by accepting the binding legal character of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, has also accepted that the Internal Market is constitutionally conditioned, particularly by social rights.Footnote 67

The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights: a specifically ‘social’ constitutional condition of the Internal Market

By giving the Charter the same status as the Treaties (Article 6 TEU), the Member States have endowed the EU with a meta-layer of rights enjoying priority over other law.Footnote 68 This emerges from the priority of human dignity as the ‘real basis of fundamental rights’ (Explanatory text to Article 1 Charter), which does not lend itself to accepting the constitutional protection of markets as such, or economic actors who are not human beings. Under Article 1 Charter, human dignity ‘is inviolable (and) must be respected and protected.’ According to Article 51, the Union and its Member States (when implementing Union law) ‘shall (...) respect the rights, observe the principles and promote the application thereof’. Taken together, these provisions reflect a comprehensive human rights doctrine, as in particular endorsed by the European Court of Human Rights, according to which public authorities must respect, protect and promote human rights.Footnote 69 The Charter thus moves beyond a merely defensive towards a comprehensive conception of human rights.

The Charter also constitutes a new era of rights constitutionalism in that it views the values of dignity, freedom, equality and solidarity as indivisible,Footnote 70 instead of repeating the traditional compartmentalisations of guarantees into civil, political and socio-economic rights.Footnote 71 For example, social and labour rights are not quarantined into one chapter only containing principles. They are scattered across the Charter: Article 5 banning slavery and Article 12 guaranteeing the right to join a trade union alongside Article 15 guaranteeing the right to engage in work, can be found under the heading ‘freedoms’, while under the heading ‘solidarity’, rights to information and consultation at the place of work (Article 27), to collective bargaining (Article 28), and to fair working conditions respecting health, safety and dignity, as well as providing for annual leave and limits to the daily working time (Article 31) accompany a straight forward prohibition of child labour (Article 32), and the demand of respect for entitlements to social security benefits and social and housing assistance (Article 34). The Charter also guarantees rights for business: for example, Article 15 guarantees the free movement of employeesFootnote 72 as well as entrepreneurs,Footnote 73 though this guarantee is limited to natural persons, and does not encompass corporate actors. Their interests are protected by the Treaties’ economic freedoms, as well as by Articles 16 and 17 of the Charter.Footnote 74 The right to a private life (Article 7) can be relied upon to ward off overzealous scrutiny of business by competition authorities,Footnote 75 while freedom to express an opinion can be relied upon for defending labelling and other marketing strategies.Footnote 76 While Article 21(1) protects against discrimination on grounds such as sex, racial and ethnic origin and disability also in working life,Footnote 77 the second paragraph of this provision protects economic actors as well as employees against discrimination on grounds of nationality.

This de-compartmentalisation of rights refutes the alleged hierarchy between the EU economic constitution and its social constitution (epitomised by the objective to approximate working and living conditions while their improvement is being maintained) in favour of the former. In guaranteeing protections of potentially conflicting interests alongside each other, the Charter confirms that competing interests can and must be reconciled.

Significantly, the Charter establishes a subtle hierarchy between rights through differentiation in the textual guarantees. Some rights are guaranteed with an inherent restriction, for example indicated by the phrase that they are guaranteed ‘in accordance with Union law and national law and practices’, or ‘may be regulated by law in so far as is necessary for the general interest’. For justifying a limitation of rights with such an inherent limitation, EU or national legislators can rely on any general interest, and do not have to identify a specific Charter right which demands the limitation. By contrast, if a right is guaranteed without an inherent limitation, justifications of restrictions must comply with a higher standard. These differences indicate a structured interrelation of Charter rights: rights with inherent limitations must cede more ground to rights without those inherent limitations than vice versa.

Even more radically, the subtle hierarchy thus established accords a slight priority to social rights. It guarantees all business-related rights (Articles 16 and 17), which underpin economic freedoms such as freedom of establishment and freedom to provide services, merely in accordance with Union law and national law and practices, or subject to such limitations as are necessary for safeguarding the public interest. These inherent limitations of business rights confirm the Court’s case law from before the Charter was adopted.Footnote 78 By contrast, some social rights are guaranteed without inherent limitations. This applies, for example, to the right to fair and just working conditions (Article 31) and freedom of association (Article 12), though rights to collective bargaining and action (Article 28) are merely guaranteed in accordance with Union law and national practice. This specific hierarchy constitutes a more favourable position for some social and labour rights in comparison with rights underpinning economic rights. It mirrors the EU socio-economic model,Footnote 79 which allocates a specifically enhanced position to social integration.

Nevertheless, the Charter at times guarantees social rights at the same level as economic rights. For example, both the freedom to conduct a business (Article 16) on the one hand and workers’ rights to information and consultation (Article 27) and entitlements to social security and social assistance (Article 34) on the other hand are guaranteed ‘in accordance with Union law and national law and practices’. Under Article 52(1) of the Charter potential clashes of equally ranked rights are to be resolved through mutual maximisation:Footnote 80 Charter rights can be limited – subject to the principle of subsidiarity – if this is necessary to protect the rights and freedoms of others. Thus, countervailing rights should be realised to the degree that on balance neither is limited any more than necessary. Its effective implementation depends on the bi-directional application of the proportionality principle. For example, if workers’ rights to information and consultation are relied upon to limit freedom to conduct a business, the proportionality principle requires that the restriction of freedom to conduct a business does not go over and above what is necessary to achieve the aim pursued. This may result in limiting the scope for information and consultation of employee representatives. A bidirectional approach requires that the judge scrutinises any such limitations of workers’ rights by assessing whether they go over and above what is necessary to safeguard freedom to conduct a business.

The Court’s case law, if favouring constitutional rights epitomised by economic freedoms, does not always comply with these principles. Restrictions of economic freedoms must safeguard human rights as protected by EU law,Footnote 81 but if Member States rely on human rights for justifying such restrictions, human rights protection is relegated to ‘the second (justification) stage of analysis’.Footnote 82 The bi-directional application of the proportionality principle would correct this imbalance.

What does constitutional conditioning achieve in principle?

Predominantly, the concept of constitutional conditioning perceives of (social) rights guarantees as shaping economic integration. This contrasts with perspectives that perceive of markets as spheres of original liberty, quasi-governed by forces of nature, pre-empting any human rights guarantees. Such liberalist perspectives would utilise human rights guarantees for the defence of market processes against ‘intervention’ by regulation, litigation or policies promoting the general interest, including social policy. What appears as ‘intervention in markets’ from those liberalist perspectives is transformed into the constitutional conditioning of markets under the approach proposed here. Markets must be structured and regulatedFootnote 83 for the sake of realising the constitutional condition in which they are meant to be.

The Charter of Fundamental Rights supports constitutional conditioning in two ways: first, it establishes subtle hierarchies between rights, which weaken those guarantees that underpin economic freedoms, notably the freedom to conduct a business and the right to property. Some social rights are not so limited, which is an expression of constitutional conditionality in favour of social rights. Second, the Charter demands mutual optimisation of those rights guaranteed at equal level, which defies the priority which has been allocated to economic freedoms by the Court so far.

The next section considers some practical applications, discussing in how far the constitutional conditioning provides a template for the European Court of Justice to revise its case law on economic freedoms.

Practical consequences of constitutional conditioning

This section revisits the Court’s much discussed Laval quartet,Footnote 84 and proceeds to analyse the AGET Iraklis ruling of December 2016.Footnote 85 It demonstrates how the constitutional conditioning parameter offers a set of new hermeneutic principles derived from the Charter, by which the Court can decide cases where economic freedoms and social rights seem to clash in line with the EU Treaties’ commitment to social justice.

Re-drafting Viking and Laval

The roots of the widely debatedFootnote 86 set of cases known as the ‘Laval quartet’ lie in the purported clash between effective collective bargaining and collective industrial action and the EU economic freedoms; the perception that this conflict can only be resolved by limiting either collective bargaining rights (as social rights) or economic freedoms; and the ‘solution’ offered by the Court affirming the priority of the latter.

In the 1970s, the Court first established that collective agreements may constitute a restriction of today’s Article 56 TFEU.Footnote 87 In 1997 the Court found that a Member State refusing to commit police forces to curb social protests against the Internal Market in goods infringed what is today Article 34 TFEU.Footnote 88 From then on, it was easy to predict that the Court would target as an infringement of economic freedoms any collective industrial action that would make the cross-border provision of services or re-establishment of a company less attractive.Footnote 89 However, the rulings in Laval and Viking Footnote 90 further elaborated this past case law, and brought home the implications of applying the economic freedoms largely unfettered by effective protection of social rights in an Internal Market with vastly diverging in wage levels.

The Laval case has its origins in a claim lodged by Laval, a Latvian company and owner of the Swedish company Baltic Bydd,Footnote 91 before Swedish courts. Laval challenged the legality of a blockade and other modes of industrial action staged by BYGNADS, the Swedish builders’ trade union with the aim of concluding a collective agreement between BYGNADS and the Swedish company which would guarantee that pay was governed by the same framework for all workers working side by side on the same building site. Baltic Bydd used workers posted by its Latvian owners, and did not intend to pay these Latvian workers at levels usual in Sweden. There are some indications that the case was staged from Sweden to break the hold of BYGNADS on wages in the building sector.Footnote 92 The Viking case emerged from an employer’s claim against the Finnish Seamen’s Union and the International Transport Workers Federation, raised before a British court because the International Transport Workers Federation is registered in London. The employer had re-registered a vessel under the Estonian flag, with the aim of enhancing the profitability of a ferry between Tallinn and Helsinki by lowering wages paid to seafarers. The Finnish Seamen’s Union threatened collective action, and the International Transport Workers Federation issued a circulaire to its members asking them not to enter into negotiations with Viking Line ABP while the industrial dispute was ongoing. The combination of these activities had effectively hindered the employer from lowering wages until Estonia joined the EU. At this point, the employer decided to litigate, relying on its EU economic freedoms to achieve the aim it failed to accomplish through negotiation.

In both cases the Court held that the right to collective bargaining and collective industrial action was guaranteed under EU law in principle, and that collective industrial action aiming to improve working conditions could in principle justify the restriction of economic freedoms by efficient collective industrial action. However, collective industrial action would only be proportionate to achieving that aim if it was absolutely necessary for this purpose. For the Viking case, that judgment was left to the national court. However, the European Court of Justice held that boycotts and strikes would only be legal if necessary to protect the Finnish workers’ posts or working conditions, and that the employers’ legally non-binding commitment to refrain from dismissing the Finnish crew would render the action unnecessary. In the Laval case, the Court found the industrial action of a Swedish trade union aiming to force an employer posting Latvian workers to sign an association agreement with them to be unjustifiable. Much of the case turned on the interpretation of Directive 96/71,Footnote 93 which, however, was interpreted as mere specification of Article 56 TFEU on freedom to provide services. That provision, the Court held, prevented the trade union from fighting for a higher level of protection than was guaranteed by EU legislation and required that the trade union disclose its red lines before any negotiation even started. There was no margin of appreciation for the trade unions in justifying their action, which would ensure that economic freedoms and fundamental constitutional rights were adequately balanced, resulting in critical assessment by international human rights bodies.Footnote 94

Under the principles of a constitutionally conditioned Internal Market this line of case law is untenable. This derives from the specific hierarchy established by the Charter between collective labour rights and constitutional equivalents of economic freedoms.

Collective labour rights such as the right of freedom of association (in Article 12) and the right to collective bargaining and collective industrial action (in Article 28) are inextricably linked, though guaranteed in discrete provisions of the Charter. This is particularly well established by the European Court of Human Rights case law on Article 11 ECHR, which clarifies that a guarantee of freedom of association for trade unions includes constitutional protection of collective bargaining and collective industrial action.Footnote 95 To maintain congruence of the European Convention on Human Rights and the Charter, as demanded by Article 52(3) of the Charter, Article 12 must be read – in line with this European Court of Human Rights case law – as embodying rights to collective bargaining and collective industrial action.Footnote 96 Article 12 thus forms the basis for collective labour rights in the Charter, while Articles 27 and 28 provide specifications. Accordingly, collective labour rights are guaranteed as rights that can be restricted only with reference to Article 52 of the Charter, i.e. to protect the general interest or competing rights. The reference to national traditions in Article 28 retains its relevance in that the Union guarantees must account for the diversity of national traditions in industrial relations. Any limitation of the rights to collective bargaining and collective industrial action must not deprive these rights of their essence. Further, the limitation must be proportionate to achieve its aim. Hence, the question must be asked whether curtailing collective bargaining and industrial action is unavoidable for enabling the exercise of the economic freedoms.

The economic freedoms of corporations can be underpinned by Article 16 of the Charter, and are thus only guaranteed in accordance with Union law and national law. Since the Charter is part of Union law, Article 16 rights are only guaranteed in line with Article 12 rights. Accordingly, business in the EU must occasionally expect to be subjected to industrial action as well as to be bound by collective bargaining agreements.

To comply with the Charter, the Court would have to assume that collective industrial action is nothing unusual. Accordingly, strikes or blockades would not automatically qualify as restrictions of economic freedoms. If a Swedish business operating in Sweden that is evading its obligations under collective labour agreements is subjected to collective industrial action, a Latvian business evading that same obligation would have to expect the same treatment. Thus, the strike action suffered by Laval un Partneri would not constitute any specific detriment to transnational business, and hence no restriction of freedom to provide services. Similarly, since trade unions oppose companies moving to escape the binding force of a collective agreement, collective industrial action undertaken with that purpose is admissible in principle.Footnote 97 The same activity directed against an employer that aims to establish itself in another EU Member State can hardly be viewed as restriction of freedom of establishment.

Under specific circumstances, collective industrial action may still qualify as a restriction of economic freedoms. For example, if trade unions would engage in collective industrial action with the aim of preventing individual persons from exercising their free movement rights – whether as workers or service providers – this would clearly constitute a restriction. Similarly, if trade unions would specifically target foreign companies avoiding collective agreements by exercising their free movement rights, but fail to target national companies avoiding collective agreements in other ways, this might also constitute a restriction. In both cases, the Court would still have to consider potential justifications for collective industrial action by using the bidirectional proportionality test developed earlier.Footnote 98 The Court would have to consider whether limiting options to take collective industrial action is necessary to protect the freedom to provide business across a border, keeping in mind that Article 16 of the Charter is less robust than Article 12.

The concept of the constitutionally conditioned internal market provides a new answer to the conundrum posed by the Laval and Viking conflict; an answer that is also in line with international guarantees of collective labour rights, and that avoids the challenges made before these committees.Footnote 99

The AGET Iraklion case: protecting the freedom to conduct a business versus workers’ participation in collective redundancies

While the Court has not yet revisited its case law on the conflict between collective labour rights and economic freedoms, the AGET Iraklis Footnote 100 case offered an opportunity for the Court to reconsider its contested case law on Article 16 of the Charter, and thus provides another example of the potential use of constitutional conditioning.

The case concerned collective redundancies in Greece, and more particularly the viability of national legislation requiring a ministerial authorisation of any collective redundancy in the absence of an agreement with the workers’ representatives. The case, allocated to the Grand Chamber, had a certain political salience, since it was referred by the Greek Council of State and related to legislation which has been part of the negotiations of the Memorandum of Understanding of August 2015 as well as a subject of debate by the Expert Group established in order to review labour law reforms which Greece undertook under a previous Memorandum of Understanding.Footnote 101

Directive 98/59Footnote 102 on collective redundancies neither requires nor precludes national legislation demanding consent of the works council or the ministry before a collective redundancy can become effective.Footnote 103 While the widely-discussed Alemo Herron case concerned the degree to which the UK legislator had to consider Article 16 of the Charter while implementing Article 3 of Directive 2001/23 on transfers of undertakings,Footnote 104 the Greek legislation at stake in AGET Iraklis went over and above the requirements of Directive 98/59. To the extent that it was not required, the Court found it did not implement Directive 98/59. Thus, in order to be able to use the Charter as a standard, the Court needed to establish that the Greek legislation restricted an economic freedom, in this case Article 49 TFEU.Footnote 105

The Court followed Advocate General Wahl in finding that the national legislation restricted freedom of establishment, that justification of the national measure would also have to satisfy the requirements of Article 16 of the Charter, and that the specific restriction of Article 49 TFEU (read in the light of Article 16 of the Charter) was not justifiable.

In deciding whether there was indeed a restriction of freedom of establishment, the Court relied on its former case law that minimises the level of transnational activity a business needs to engage in to gain the protection of the EU economic freedoms.Footnote 106 Going beyond such reasoning, Advocate General Wahl opened his opinion with the statement ‘The European Union is based on a free market economy, which implies that undertakings must have the freedom to conduct their business as they see fit’. The Court factually endorsed that reasoning without expressly referring to it: it stated that freedom of establishment not only constituted a positive right to establish in another Member State, but also a negative freedom to close down a subsidiary in that other Member State or reduce its activities.Footnote 107 Also, the Court qualified taking on and dismissing employees as a decisive element of the freedom of establishment.Footnote 108 Under this logic, any legislation limiting the employers’ freedom to dismiss employees would constitute a restriction of Article 49 TFEU, which would contrast with the Court’s case law up to then on economic freedoms, according to which employment protection would only constitute a restriction of the free movement of workers if it specifically deterred an employee from moving to another country.Footnote 109 As a result, a Greek company struggling to comply with Greek employment protection law was protected by Article 49 TFEU on the basis that 89% of its shares were held by a French multinational group of companies.Footnote 110

Both the Court and its Advocate General also refer to Charter rights at the justification stage. While Article 16 of the Charter had already been used to extend the scope of freedom of establishment, it made another appearance at this stage, as Member States must protect Charter guarantees of business freedom while limiting TFEU economic freedom. Article 16 was read in a strictly libertarian way as the ‘freedom to exercise an economic or commercial activity, freedom of contract and free competition’,Footnote 111 and thus ran parallel to an unconditioned freedom of establishment. Only social rights are referred to at the justification level.

Advocate General Wahl initially considered that, at the justification level, a balance needs to be struck between business freedom and other Charter rights.Footnote 112 He found that Article 27 of the Charter (workers’ rights to consultation and information) must be given specific expression in EU and national law, which Directive 98/59 does not provide. Thus Article 27 does not provide any protection here. Neither does Article 30, which guarantees the protection of workers in cases of unjustified dismissal, protect against economically motivated redundancies in Wahl’s view. Accordingly, he found no need to balance that provision with business freedom.

The Court made ample reference to the EU’s social objectives,Footnote 113 which feed into aspects of general interest which in principle may justify employment protection legislation (e.g. protection of workers, or the maintenance of employment).Footnote 114 The Court briefly mentioned Article 30 of the Charter in the context of proportionality.Footnote 115 However, the Court only discussed whether the framework for collective redundancies is sufficiently transparent and predictable to avoid violation of Article 16 of the Charter, and did not refer to Article 30.Footnote 116 As a result, a legislative prohibition on effecting collective redundancies was viewed as disproportionate. In effect, Article 30 of the Charter was thus not given substantive weight, and Article 27 was not mentioned. The reference to social policy objectives without linking them to their fundamental rights basis inevitably left the freedom of establishment, bolstered by Article 16 of the Charter as a fundamental right, as the stronger, and victorious, principle. The ‘commendable’Footnote 117 lengthy discussion of social policy objectives in effect legitimised that weakness with its juxtaposition of social policy and economic integration.

Taking due consideration of the constitutionally conditioned Internal Market, the argument would need to proceed along different lines. Since the EU is based on a social market economy (Article 3 TEU), and not merely on a free market economy, cross-border cooperation based on the economic freedoms is constitutionally conditioned. Accordingly, the freedom of establishment as guaranteed by the Treaties would be conditioned by legislation (at EU or national level) protecting against dismissal and thus specifying Article 30 of the Charter, and ensuring that workers are consulted and informed (specifying Article 27 of the Charter). While the Court admits that Article 16 ‘recognises’ the freedom to conduct a business in accordance with Union law and national law and practice, without guaranteeing it unconditionally, its refusal to substantively engage with Articles 30 and 27 as fundamental rights results in the de-recognition of their guarantees as conditions for the Internal Market.

Article 30 of the Charter in particular is not devoid of content: following the Explanations to the Charter, it must be interpreted with reference to Article 24 of the European Social Charter, according to which dismissals may be based on the operational requirements of the business, but mere economic difficulties can arguably not justify collective redundancy.Footnote 118 Under Article 30 of the Charter, protection against dismissals is provided as guaranteed by Union law as well as national law and practice. Union law would comprise secondary legislation (which does not limit the freedom to dismiss employees), as well as Charter rights, including the right to engage in work (Article 15). National laws and practice include the Greek legislation which considers a collective dismissal unjustified in the absence of either agreement with the workers’ representatives or ministerial authorisation. That national law also sets the frame in which the right to business is guaranteed, alongside employees’ right to engage in work and their right to protection in the event of unjustified dismissal. This leads to a different interpretation of Article 49 TFEU than that chosen by the Court. Since Article 49 TFEU is conditioned by the existing legislation in the field (as is, implicitly, Article 16 of the Charter), the mere application of employment protection legislation would not even constitute a restriction of this guarantee. The proportionality test would only be necessary if legislation either treated international employers differently from Greek employers, or factually had a more detrimental effect on international employers than on Greek employers.

Overall, the concept of constitutionally conditioned economic integration allows a reasoned critique of overly libertarian case law and, if applied by the Court, would really make a difference in certain pivotal cases.

Conclusion

This article has developed the constitutionally conditioned Internal Market as a novel approach to EU constitutional law which offers the European Court of Justice an alternative to prioritising EU economic freedoms over social rights in its future case law.

The concept of a constitutionally conditioned Internal Market challenges the dogma that the EU’s economic and social constitutions necessarily stand in juxtaposition to each other. Drawing on the priority of human dignity and a modern human rights concept as embodied in the Charter, this article concludes that the Internal Market is not ‘intervened in’ by protecting social and labour rights, but that it is rather conditioned by adequate respect for, and protection and promotion of, these rights. This concept underlines the necessity for policy change, and at the same time develops innovative ways for warding off challenges posed by socio-economic standards established by legislation or collective agreement.

As stressed above, the concept of a constitutionally conditioned internal market comprises the often rehearsed suggestion that in cases of conflict between economic freedoms and social and labour rights, a bi-directional proportionality test has to be conducted.Footnote 119 The Court should not only ask whether the social right protected by legislation or collective bargaining disproportionately limits the economic freedom, but also consider whether depriving citizens of the specific social or labour right is necessary to safeguard the relevant economic freedom. Similarly, if the aim is merely to redraw the boundaries of the European Court of Justice to control national law (i.e. to move the balance in favour of the Member States), the doctrinal proposal to ‘restrict the restriction’Footnote 120 can achieve some progress in that the Court would exercise less control over national law.

However, these proposals do not raise the question of whether the primacy of economic freedoms over social and labour rights is fundamentally wrong or not. By contrast, the constitutionally conditioned Internal Market establishes that rights, including those derived from the EU’s social constitution, shape rather than restrict EU economic freedoms, effectively challenging the dominance of the latter. Using the example of social and labour rights, the article has demonstrated how these rights can be treated as a condition under which the Internal Market can function, and the economic freedoms implemented. This concept allows some scope for economic freedoms and competition law in so far as these instruments are suitable to overcome national and regional barriers to economic integration. Constitutionally conditioned, economic freedoms are not just drawn back in favour of Member States or public legislators. Instead they are redrafted to accommodate, and incorporate the civilisation of raw market power by accommodating social concerns. This way, the judicial application of Internal Market law can encourage and invigorate discourse on the best shape for the transnational market and society to which the EU aspires.

Just developing these arguments is not, however, sufficient to exchange the ‘free market economy’ –conjured by Advocate General Wahl as the EU’s economic constitution – for the constitutionally conditioned social market economy, as demanded by the Treaties and the Charter of Fundamental Rights for the EU. As the Court must be viewed as a political actor, the preconditions for changes in its case law presuppose the development of a wider discourse on the adequate constitutional frame for the future of EU integration. Such discourse at the European level by a variety of actors would enable the rediscovery of social integration as an endeavour underlying the EU project. The present geo-political situation provides the leverage to develop and strengthen this discourse. While ‘Brexit’ is based on internal UK politics, the fears of increasing EU economic integration suffered by those who feel left behind exist throughout the EU. Those same fears are used to justify a retreat towards protecting work for nationals, and to limit economic integration beyond the EU, particularly with the US. The EU model of socio-economic integration offers, in principle, an alternative to economic integration without any consideration for social concerns. If the EU is to prevent its own disintegration and safeguard its geo-political position, a retreat from its project of integration through rights does not seem a promising avenue. Instead, rebalancing the integration project in a truly European way would require strengthening the social element through reinforcing rights. It seems an appropriate time to engage in this discourse, for example through critical engagement with the European Pillar of Social Rights and its implementation.