Introduction

Government pro tempore is an essential characteristic of democratic governance, which establishes temporal limits on office holding and policy making (Linz Reference Linz1998). Yet, it is still poorly understood whether and how governments’ limited term in office affects the timing of their activities. At the start of their term, office holders attempt to respond to their constituencies in a policy-making environment they are not familiar with yet. Over time, however, they can update their beliefs and consider whether the incentives of potential challengers (due to policy divergence) require activity adaptation. Based on their own abilities (due to power), office holders may then adapt the timing of their further activities to optimize the benefits and costs in a policy-making environment where multiple parties pursue individual policy positions for electoral competition. While such adaptation might follow more complex dynamics—due to election closeness, external events, parliamentary workload, or other experiences—we provide a new account for the temporal dimension of democratic governance that considers the influence of learning on the timing of bill initiation in parliamentary democracies.

Parliamentary democracies, usually ruled by multiple parties under a coalition government, face two major challenges after government formation. In policy making, a dilemma arises when coalition parties pursue divergent policy positions for electoral purposes but can only implement one government bill jointly (Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2005; Reference Martin and Vanberg2014; Reference Martin and Vanberg2020b; Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999). In addition to this dilemma, a temporal challenge exists for the passage of government bills within a term that may limit the implementation of the governmental policy agenda when coalition policy divergence increases the risk of gridlock (Bäck and Carroll Reference Bäck and Carroll2018; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002) with obstruction and delay (Bell Reference Bell2018; Döring Reference Döring and Döring1995; Martin Reference Martin2004). From a principal-agent perspective on coalition government, the office-holding minister enjoys a first-mover advantage for drafting government bills in her portfolio, but strong parliamentary institutions allow coalition partners to scrutinize and amend those bills, which can lengthen the duration of the policy-making process (Becher Reference Becher2010; Carroll and Cox Reference Carroll and Cox2012; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2011).

Taking these two challenges together, we argue that ministers’ first-mover advantage is constrained by the type of their coalition partner—a cooperative type who immediately approves their bills under a parliamentary majority or a competitive type who pursues a vote-maximizing motivation that opens the gate for more scrutiny of those bills in parliament.Footnote 1 At the beginning of the term, ministers may not know the type of their coalition partner in their portfolio, but—after experiencing scrutiny or immediate approval of their bills in parliament—they can learn it and time the initiation of their subsequent bills to prevent defeat, extensive modification, or delay.Footnote 2 In other words, ministers can learn from their experienced scrutiny and use their agenda control to time the initiation of bills within their portfolios over a term. If a minister encounters a cooperative partner, she can implement bills more speedily in her portfolio, which promises electoral benefits by showing responsiveness to her constituency. However, an encounter with a competitive partner might result in late bill initiation, risking partial implementation of the minister’s policy agenda and disappointment among her constituency.

Our argument provides a theoretical foundation for changes in policy agenda, where ministers seek position-taking policy benefits by early initiation of government bills to demonstrate responsiveness to their constituency (e.g., Huber Reference Huber1996; Martin Reference Martin2004; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2005; Reference Martin and Vanberg2011; Powell Reference Powell2004), benefits that late initiation can decrease. Building on existing research on coalition government, we acknowledge that the coalition partner can theoretically constrain ministerial policy making, but our study moves this literature forward, highlighting the consequences of the use of institutional control mechanisms of coalition partners (such as parliamentary scrutiny) and the learning process of ministers in response to experienced scrutiny. We theorize that, over the term, ministers update their beliefs about the partner’s type based on their experiences with parliamentary scrutiny (or immediate approval) of their bills in parliament. We derive novel predictions that (1) ministers initiate their bills later in the term the greater the scrutiny they have experienced and that (2) this effect of experienced scrutiny on the timing of bill initiation is stronger the greater the divergence of policy positions between coalition parties and (3) the fewer the powers ministers have to constrain scrutiny activities in parliament.

Our dynamic temporal perspective on democratic governance also complements the more general literature on legislative obstruction (Bell Reference Bell2018; Fong and Krehbiel Reference Fong and Krehbiel2018; Patty Reference Patty2015),Footnote 3 which is considered a prominent phenomenon in parliamentary democracies (Bücker Reference Bücker1989; Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox, McCubbins, Edwards, Lee and Schickler2011; Döring Reference Döring and Döring1995) and bicameral systems (Tsebelis and Money Reference Tsebelis and Money1997). Our dynamic temporal perspective allows for ministers learning from past policy-making experiences and adapting their behavior in order to reduce the amount of scrutiny and improve the governmental record. Compared with existing static theories, this dynamic temporal perspective improves our understanding of the relative temporal effects of democratic governance. In particular for intermediate and sufficiently low levels of responsiveness, our predictions differ from a one-period perspective without learning. The static and the dynamic perspectives predict early initiation in her portfolio only when the office holder can expect high position-taking benefits for her party.

Instead of providing a more complex theory, we account for such effects empirically. Methodologically, the analysis of periodical and portfolio-specific timing of government bills requires consideration of the temporal structure of the data on legislative cycles in parliamentary democracies. By treating terms as new cycles of policy-making activities, in which ministers can learn about their partner type from experienced scrutiny of their government bills, we account for the cyclical structure of the data using a circular regression analysis (Gill and Hangartner Reference Gill and Hangartner2010) and devise corresponding visualization tools to investigate the timing of bill initiation.Footnote 4 As our explanandum is defined by the relative temporal location of bill initiation within a term, we investigate the agenda control of ministers over the immediate or late initiation of government bills.

The Temporal Dimension of Coalition Policy Making in Parliamentary Democracies

Democratic governance imposes temporal limits on policy making. It limits the duration of office holding and terminates the duration of policy-making processes with the dissolution of parliament, the end of parliamentary sessions, or the conclusion of legislative terms (Döring Reference Döring and Döring1995; Reference Döring2001). For policy making in coalition governments, this temporal dimension may also enhance coalition tensions and restrict policy agenda changes. According to Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2011), for example, early bill initiation gives ministers an opportunity to demonstrate responsiveness to their constituency that they are working hard on their behalf.Footnote 5 When elections approach, Strobl et al. (Reference Strobl, Bäck, Müller and Angelova2021) show that coalition governments are less likely to implement (austerity) policies that risk alienating voters (see also, König and Wenzelburger Reference König and Wenzelburger2017).

More generally, Martin (Reference Martin2004) found that coalition governments usually pursue an accommodating policy agenda, in which government bills with little policy divergence of coalition parties have priority, while others are postponed. Conversely, Sagarzazu and Klüver (Reference Sagarzazu and Klüver2017) showed that at the beginning and at the end of the term the strategy of differentiation between coalition partners predominates, while coalition compromise is more likely in the middle of the term. As coalition participation influences voters’ perceptions of partisan policy positions (Fortunato, Silva, and Williams Reference Fortunato, Silva and Williams2018; Fortunato and Stevenson Reference Fortunato and Stevenson2013), coalition members have incentives to differentiate themselves from their coalition partners to improve their electoral chances (Fortunato Reference Fortunato2019).

These incentives can generate principal-agent problems in government policy making between ministers and their coalition partners, especially when the policy divergence of coalition parties increases (Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2005; Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999; Strøm and Müller Reference Strøm, Müller and Longley2000; Strøm, Müller, and Bergman Reference Strøm, Müller and Bergman2003). These problems continue to exist despite attempts to alleviate them via screening of coalition partners (Kiewiet and McCubbins Reference Kiewiet and McCubbins1991; Saalfeld Reference Saalfeld2000; Strøm Reference Strøm and Döring1995; Reference Strøm2000), ministerial portfolio allocation (Bäck, Debus, and Dumont Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Bassi Reference Bassi2013; Reference Bassi2017; Laver and Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990; Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996; Martin and Stevenson Reference Martin and Stevenson2001), and formal agreements on coalition compromise (Bäck, Müller, and Nyblade Reference Bäck, Müller and Nyblade2017; Bowler et al. Reference Bowler, Indridason, Bräuninger and Debus2016; Indridason and Kristinsson Reference Indridason and Kristinsson2013; Klüver and Bäck Reference Klüver and Bäck2019; Moury Reference Moury2013; Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999; Reference Müller, Strøm, Strøm, Müller and Bergman2008; Strøm and Müller Reference Strøm, Müller and Longley2000; Timmermans Reference Timmermans2017).

According to this literature, higher coalition policy divergence increases the incentives of ministers—who have the task and expertise to draft government bills within their portfolios—to drift from previously agreed upon coalition compromise by proposing “hostile” bills, while it motivates the coalition partner to coalition policing by scrutinizing and amending such proposals in parliament to avoid policy losses (Becher Reference Becher2010; Huber Reference Huber1996; Laver and Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990; Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996; Martin Reference Martin2011; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2005; Reference Martin and Vanberg2020a; Tavits Reference Tavits2008). This, however, risks inaction and delay, with high electoral costs for the responsible parties when the costs for coalition policing exceed the benefits of jointly implementing government bills (Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Fortunato et al. Reference Fortunato, Lin, Stevenson and Tromborg2021).

This dilemma of coalition governance has sparked prolific research on the conditions under which ministers propose “hostile” bills and coalition partners (successfully) scrutinize such bills. From a spatial perspective on policy divergence, Laver and Shepsle’s (Reference Laver and Shepsle1996) prominent model of portfolio allocation suggests that ministers can autonomously implement their policy position within their portfolios when their party holds the median position in parliament. Under a constrained environment, Martin and Vanberg’s (Reference Martin and Vanberg2011) model of coalition bargains also predicts that ministers initiate hostile proposals—government bills representing the policy position of their party instead of the previously agreed upon coalition compromise—for seeking electoral position-taking benefits.

Studies contend that in parliamentary democracies with strong institutions, coalition parties can overcome their dilemma and implement coalition compromise by allowing coalition partners to scrutinize and amend government bills in parliament, even if ministers pursue a maximal position-taking strategy by always introducing hostile proposals (Becher Reference Becher2010; Goodhart Reference Goodhart2013; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2005; Reference Martin and Vanberg2014; Reference Martin and Vanberg2020a).Footnote 6 Yet, scrutinizing government bills in parliament delays government policy making and raises challenging costs for coalition parties (Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2011).Footnote 7 Also, while ministers can only implement a maximal position-taking strategy when the challenging costs of (weak) institutions for scrutiny exceed the policy benefits of the coalition partner, higher ministerial costs of being scrutinized and amended risk delay and gridlock, with crucial electoral costs for both the partner and the office-holding ministerial party (Bäck and Carroll Reference Bäck and Carroll2018; Martin Reference Martin2004; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002).

Parliamentary institutions thus offer an imperfect mechanism for coalition partners to control ministerial discretion (Goodhart Reference Goodhart2013). Empirically, it is difficult (if not impossible) to provide evidence for the level of imperfection as the coalition partner or opposition parties can also use parliamentary institutions to scrutinize and amend government bills (Fortunato Reference Fortunato2019). Yet, the conventional wisdom and empirical evidence of government policy making are that the amount of parliamentary scrutiny increases with the level of policy divergence within coalition governments (Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2014; Reference Martin and Vanberg2020a; Pedrazzani and Zucchini Reference Pedrazzani and Zucchini2013). Furthermore, if a minister could anticipate how much scrutiny her bills will undergo in parliament, she could use her agenda control over the timing of bills to postpone bill initiation when she expects costly scrutiny, or otherwise, to initiate her bills immediately. Although ministers may not know perfectly the type of their partners at the beginning of the term, we can expect adjustments in ministerial policy-making activities over time as ministers get to know better their partners.

Theory: Ministerial Learning and Timing of Bill Initiation

To complement the predominant static perspective on coalition policy making, we introduce a parsimonious dynamic theory of government bill initiation timing.Footnote 8 Even though coalition policy making is a complex procedure, we simplify our argument to the introduction of only two pieces of bills to provide an intuitive and tractable setting for modeling ministerial learning and the timing of bill initiation. For simplicity, we distinguish between a ministerial office holder and a partner within a majority coalition government.Footnote 9

The minister is responsible for drafting two bills in her portfolio over a term.Footnote 10 She introduces the first bill at the beginning of the term and then decides when—early or late in the term—to introduce the second bill.Footnote 11 When the government and parliamentary majorities coincide, the coalition partner plays the role of a parliamentary scrutiny “gatekeeper,” who has the choice of approving immediately or allowing for scrutiny of the bills in parliament.

Because time is a scarce resource for government policy making within a term, scrutiny can impede the policy-making process and constrain the government’s ability to approve its policy agenda (Cox and McCubbins Reference Cox and McCubbins2007; Reference Cox, McCubbins, Edwards, Lee and Schickler2011; Döring Reference Döring and Döring1995; Fong and Krehbiel Reference Fong and Krehbiel2018).Footnote 12 We assume that the coalition partner can be of two types: He can be either a competitive type, who mainly cares about his performance in the next election and has vote-maximizing motivations, or a cooperative type, who is predominantly concerned about the effectiveness of coalition policy making. In other words, the type reflects whether, in addition to policy concerns, the partner has particular individual electoral concerns for the next election.

To understand this concept, it is important to distinguish between the party as a single political actor and affiliated members as current agents of the party. While long-run ideological policy preferences of the party are likely to persist over time, the short-run vote-maximizing motivations of partisan agents might vary across portfolios and from one term to another. That is why even though we model parties as single actors, the underlying assumption is that the partner’s type reflects motivations of the current ministers as party agents and is therefore randomly drawn by nature.Footnote 13

The legislative process develops as follows, whereby stages 1 and 2 reflect the static and stages 3 and 4 add the dynamic perspective:

-

1. The partner’s type (competitive or cooperative) is randomly determined by nature. To capture the information asymmetry of the coalition parties, we assume that the partner knows his own type, whereas the minister has the prior knowledge that the partner is competitive with probability q.

-

2. The minister introduces her first bill, which the partner either immediately approves or allows for scrutiny. If the partner approves, then the bill passes with the support of the parliamentary majority and the bill implements the policy position of the ministerial party.Footnote 14 If the partner does not approve the bill immediately, then the bill undergoes a monitoring process and is passed with amendments at the expense of the policy position of the ministerial party (and more in the interests of the partner’s party).

-

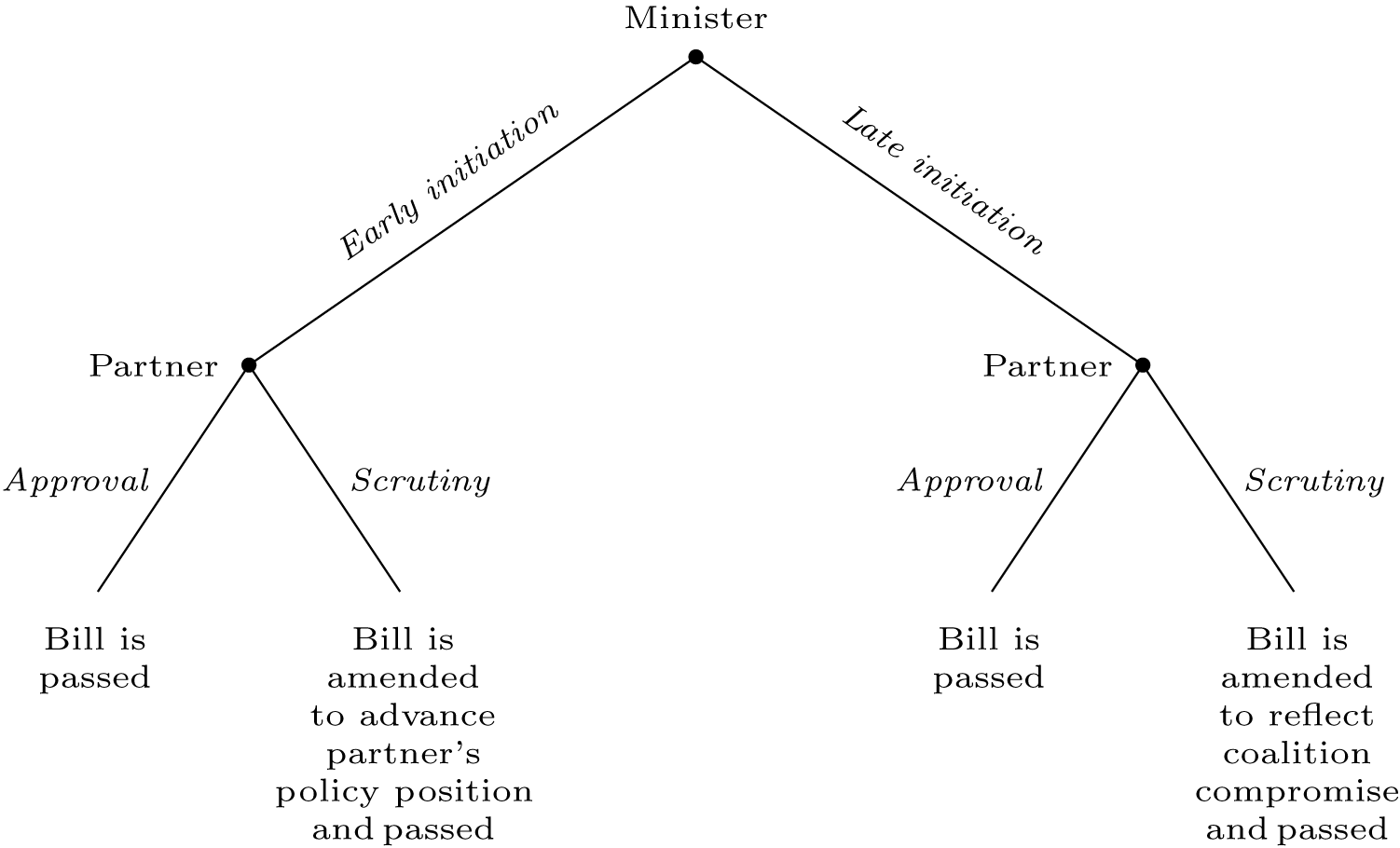

3. The minister observes whether her first bill has been immediately approved or scrutinized and updates her beliefs about the partner’s type. She decides then whether to initiate the second bill early or late in the term. Figure 1 depicts the parties’ choices and outcomes for the second ministerial bill (the complete game tree is presented in Figure B1 of Appendix I: Theory, Data, and Method).

Figure 1. Second Bill: Parties’ Choices and Outcomes

-

4. Once the second bill is introduced, the partner either immediately approves or allows for scrutiny. If the partner approves, then the bill passes with the support of the parliamentary majority and implements the policy position of the ministerial party. If the partner does not approve the bill immediately, then the outcome depends on whether the minister has initiated the second bill early or late in the term. An early-initiated scrutinized bill is passed with amendments at the expense of the policy position of the ministerial party (and in the interests of the partner’s party). Scrutiny of a late-initiated bill cannot be—due to time constraints—completed by the end of the term to advance the policy position of the partner’s party but rather results in the passage of a compromise bill.Footnote 15

We next formalize the payoffs of the coalition parties that account for their dilemma. Following the (spatial) literature on policy divergence of coalition partners, the parties have different policy positions that create principal-agent problems, as they can only implement government bills jointly. If a government bill passes without scrutiny, then the policy payoffs change from coalition compromise 0 toward +X for the minister and –X for the partner, where X > 0.Footnote

16 However, if an early-initiated bill gets scrutinized and subsequently amended to reflect the partner’s policy position, then the policy payoff to the minister is

![]() $ -\frac{X}{\alpha } $

and the policy payoff to the partner is

$ -\frac{X}{\alpha } $

and the policy payoff to the partner is

![]() $ \frac{X}{\alpha } $

, where

$ \frac{X}{\alpha } $

, where

![]() $ \alpha \ge 1 $

denotes the minister’s power to constrain scrutiny activities (e.g., by holding the median position, having a large seat share in parliament, etc.). In turn, the policy payoffs to both coalition parties from implementing the coalition compromise are normalized to 0.Footnote

17 Therefore, if a bill is initiated late, subsequently scrutinized, and then amended to reflect the coalition compromise, then the parties’ policy payoffs amount to 0.

$ \alpha \ge 1 $

denotes the minister’s power to constrain scrutiny activities (e.g., by holding the median position, having a large seat share in parliament, etc.). In turn, the policy payoffs to both coalition parties from implementing the coalition compromise are normalized to 0.Footnote

17 Therefore, if a bill is initiated late, subsequently scrutinized, and then amended to reflect the coalition compromise, then the parties’ policy payoffs amount to 0.

According to Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2011), early bill initiation allows the minister to demonstrate responsiveness to her constituency, that she is working hard on their behalf; thus, she generates position-taking benefits B > 0 for herself. Late initiation, in turn, is associated with temporary inaction and so generates no position-taking benefits.Footnote

18 As for the partner, the process of scrutinizing government bills imposes challenging costs. However, the competitive partner derives individual electoral benefits from scrutinized bills. We assume that these benefits compensate him for the challenging costs. In other words, for the competitive partner, the costs are offset by the individual electoral benefits he receives as a result of scrutinized bills. The cooperative partner type does not have vote-maximizing motivations but incurs the challenging costs of scrutinized bills, which we denote by C. To highlight the incentive divergence between the two types, we posit that challenging costs C are large enough that they exceed the partner’s policy benefit

![]() $ X+\frac{X}{\alpha } $

from the passage of the amended bill that advances his policy position instead of the initial bill.

$ X+\frac{X}{\alpha } $

from the passage of the amended bill that advances his policy position instead of the initial bill.

To find a solution for our dynamic perspective on bill initiation timing, we search for a perfect Bayesian equilibrium that consists of the partner’s reactions to the first and second bills, the minister’s beliefs about the partner’s type, and the minister’s subsequent decision about early or late initiation of the second bill. Specifically, the partner’s decisions to approve the bill immediately or allow it for scrutiny are optimal given his type, incentives, and expectations about early or late initiation of the second bill. In turn, the minister uses the partner’s reaction to her first bill to draw inferences about the partner’s (competitive or cooperative) type. Given these inferences and her incentives, the minister optimally decides whether to initiate the second bill early or late.

In Appendix B, we present the formal analysis and prove that there exists a perfect Bayesian equilibrium such that the competitive partner type allows for scrutiny of both bills, but the cooperative partner type approves both bills immediately. The minister learns that she faces a competitive (cooperative) partner after her first bill has been scrutinized (immediately approved). For

![]() $ B>\frac{X}{\alpha } $

, the minister initiates the second bill early in the term. Intuitively, when the minister’s policy loss

$ B>\frac{X}{\alpha } $

, the minister initiates the second bill early in the term. Intuitively, when the minister’s policy loss

![]() $ \frac{X}{\alpha } $

is relatively low compared with her position-taking benefit B, then she has incentives for early initiation even if she learns that her partner is a competitive type who will allow for scrutiny of the second bill. However, for

$ \frac{X}{\alpha } $

is relatively low compared with her position-taking benefit B, then she has incentives for early initiation even if she learns that her partner is a competitive type who will allow for scrutiny of the second bill. However, for

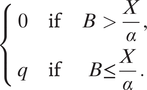

![]() $ B\le \frac{X}{\alpha } $

, the minister opts for late initiation after her first bill has been scrutinized and for early initiation after her first bill has been immediately approved. In this case, the minister’s position-taking benefit B does not outweigh the policy loss

$ B\le \frac{X}{\alpha } $

, the minister opts for late initiation after her first bill has been scrutinized and for early initiation after her first bill has been immediately approved. In this case, the minister’s position-taking benefit B does not outweigh the policy loss

![]() $ \frac{X}{\alpha } $

. As a result, the minister prefers to hinder the scrutiny process by late bill initiation after she learns that her partner is a competitive type who would allow for scrutiny again. It follows that the equilibrium probability of late initiation amounts to

$ \frac{X}{\alpha } $

. As a result, the minister prefers to hinder the scrutiny process by late bill initiation after she learns that her partner is a competitive type who would allow for scrutiny again. It follows that the equilibrium probability of late initiation amounts to

$$ \left\{\begin{array}{ccc}0& \mathrm{if}& B>\frac{X}{\alpha },\\ {}q& \mathrm{if}& B\le \frac{X}{\alpha }.\end{array}\right. $$

$$ \left\{\begin{array}{ccc}0& \mathrm{if}& B>\frac{X}{\alpha },\\ {}q& \mathrm{if}& B\le \frac{X}{\alpha }.\end{array}\right. $$

That is, for

![]() $ B>\frac{X}{\alpha } $

, the second bill is initiated early, whereas for

$ B>\frac{X}{\alpha } $

, the second bill is initiated early, whereas for

![]() $ B\le \frac{X}{\alpha } $

, it is initiated late when the partner is a competitive type (recall that the partner is competitive with probability q).Footnote

19

$ B\le \frac{X}{\alpha } $

, it is initiated late when the partner is a competitive type (recall that the partner is competitive with probability q).Footnote

19

Empirical Implications

Our theory suggests that the minister learns about her policy-making environment after observing whether her past bills have been scrutinized or immediately approved by her partner.Footnote 20 Compared with the one-period static view, our dynamic perspective makes different predictions for intermediate and sufficiently low levels of position-taking benefits. Only when the office holder can expect high position-taking benefits for her party, the static and the dynamic models predict early initiation. Specifically, greater experienced scrutiny reveals to the minister that she faces a competitive partner and that she will be constrained in her attempt to respond to her constituency, giving her incentives for late initiation of government bills. Immediate approval of bills, in turn, indicates to the minister that her partner is a cooperative type, and she has incentives to generate position-taking benefits from early bill initiation. This implies the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. The more scrutiny the minister’s bills have experienced, the later in the term she initiates subsequent bills.

Moreover, our theoretical analysis reveals that the relationship between experienced scrutiny and partner type is affected by the policy payoff X, the size of which depends on the policy divergence of coalition parties. As the policy divergence increases, the policy payoff X also increases. Intuitively, the more divergent the policy positions, the more policy losses the minister incurs from a type that scrutinizes and amends her bills in parliament. Therefore, after having learned that she faces a competitive partner, she has more incentives for late initiation of bills to hinder further scrutiny. This leads to our second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. The higher the policy divergence between the coalition parties, the stronger the positive effect of experienced scrutiny on late initiation of bills.

Furthermore, the relationship between experienced scrutiny and timing of bill initiation is affected by the minister’s power α to constrain scrutiny activities. The more powerful the minister, the less likely parliamentary scrutiny and amendment of her bills are. Consequently, the minister incurs fewer policy losses, reducing her incentives to hinder further scrutiny by late initiation. This implies our third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3. The more powerful the minister is, the weaker the positive effect of experienced scrutiny on late initiation of bills.

Our hypotheses are consistent with intuitions about the dynamics of coalition policy making in light of the trade-offs that the minister and her partner face. Having experienced immediate approval, the minister infers a cooperative partner type. She, thus, anticipates further immediate approval and so initiates subsequent bills early within the term. In turn, when she believes that she faces a competitive partner type who has vote-maximizing motivations at her expense, experienced scrutiny reveals a less supportive policy-making environment. Under the expectation of further scrutiny of her bills and subsequent policy losses from passing amended bills, the minister might opt for late initiation of subsequent bills. However, the more powerful the minister, the more she can counteract further scrutiny in parliament and so the lower her incentives for late initiation of bills after having experienced scrutiny.

Empirical Strategy

Sample Selection and Unit of Analysis

To examine our hypotheses, we have collected data from 11 European parliamentary democracies, covering all government bills from coalition governments available in the following countries’ online parliamentary databases during the period 1981–2014: Belgium (1988–2010), Czech Republic (1993–2013), Denmark (1985–2011), Estonia (2007–2011), Finland (1989–2010), Germany (1981–2012), Hungary (1998–2014), Latvia (2002–2011), the Netherlands (1998–2012), Norway (1989–2013), and Poland (1997–2011). This is the most comprehensive cross-national data set on government bills assembled to date, covering a variety of parliamentary democracies, which differ in size, wealth, culture, history, and democratic foundation but are governed by coalition parties.

Our unit of analysis is an individual proposal of a “government bill” introduced into the lower house of parliaments. We have 25,477 such observations in total. For each bill, we use legal documents to identify which ministry has proposed it and, based on this, its policy area.Footnote 21

Variables and Measurement

Dependent variable

Our dependent variable captures the relative temporal location of bill initiation within a term.Footnote 22 To make the measurement of bill initiation comparable across coalition governments with different duration, we divide the number of days from the start date of government to the date of bill initiation by the number of days of the overall observed government duration. For example, if a government started on January 1, 2010, and ended on December 31, 2013, lasting for a total government duration of four years or 1,460 days, a government bill initiated on January 1, 2011, (365 days after the government formation) is located at the 25th percentile (365/1,460) of the term. The resulting measure ranges from 0th percentile to 100th percentile, where the first days of government fall in the 0th percentile and the last days of government fall in the 100th percentile of the term.

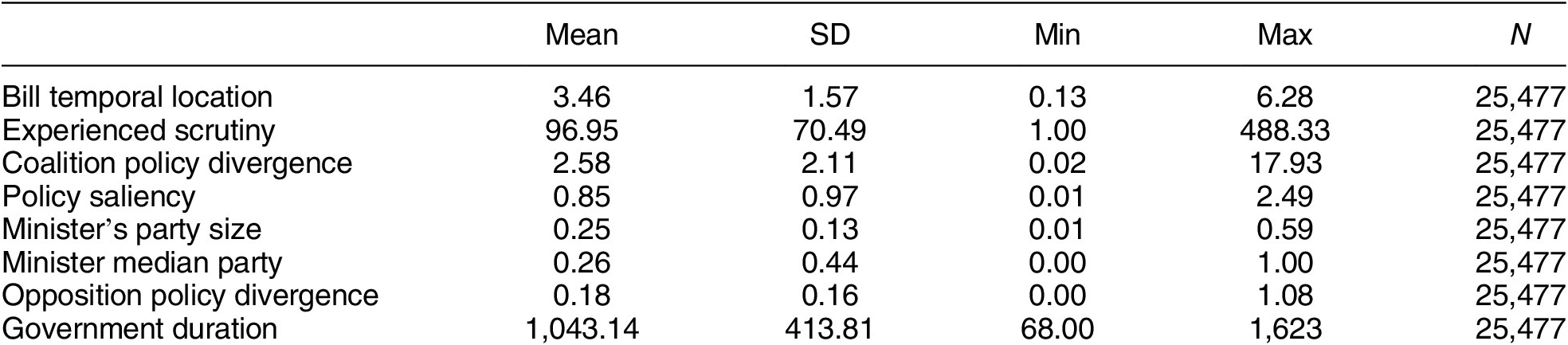

To map percentiles into cycles of terms, we transform the percentage rate into a radius measure using the formula r = 2π, which maps from [0%,100%] to [0, 2π] on a circle. Therefore, our dependent variable can theoretically range from 0 to 2π. As presented in Table 1, our dependent variable bill temporal location empirically varies from 0.13 to 6.28 in our data, with small values indicating early initiations and high values indicating late initiations.Footnote 23 In substantive terms, the minimum value of 0.13 represents the first and earliest government bill, the maximum value of 6.28 (2π) the last bill initiated within the longest term in our dataset.

Table 1. Variables and Descriptive Statistics

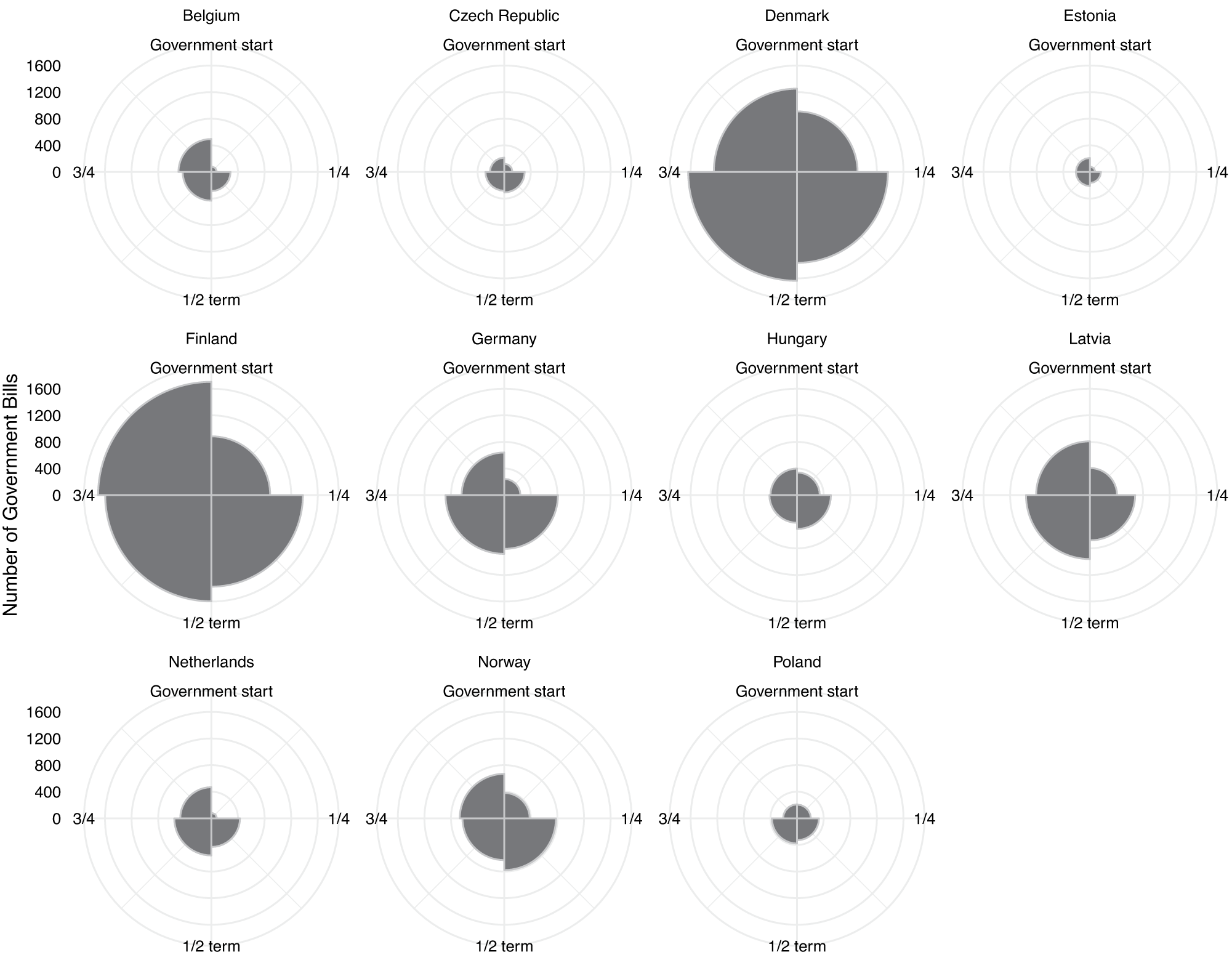

Figure 2 depicts the relative timing and number of government bills from the 11 parliamentary democracies to illustrate our circular outcomes in terms of timing of bill initiation. In this descriptive plot, we distinguish between four periods of a term: the first, second, third, and fourth periods. The circular plots show that the number of government bills differs across countries and across different periods of the terms. Countries such as Denmark, Finland, and Latvia have a larger number of government bills initiated than the other countries included in our data. In countries such as Denmark, Germany, Latvia, and the Netherlands, most government bills are initiated in the third period of the term, while in countries such as Belgium, Finland, and Norway, most government bills are introduced at the end of the term. Furthermore, the Czech Republic, Estonia, and Poland experience fewer government bills, most of which are equally distributed in the second and third periods of the term. The descriptive statistics suggest that we cover a variety of temporal decisions on government bill initiation of coalition governments.

Figure 2. Relative Timing and Number of Government Bills within Terms

Independent variables

Our first hypothesis postulates that greater experienced scrutiny of previous bills leads to late initiation of subsequent bills within the term. To measure experienced scrutiny of government bills, building on Martin and Vanberg (Reference Martin and Vanberg2004) we consider the duration (in days) that a bill takes to be enacted from the date of bill introduction. Bills that are scrutinized tend to require more time in the parliamentary policy-making process than bills that are not subject to scrutiny. Given the circular nature of our data structure, our measurement is calculated as follows: for bill i initiated at time T in term A in policy area K, duration

![]() $ {}_i $

= mean(duration of passed bills initiated in term A, concluded before T, in area K). In other words, for any observation experienced scrutiny is based on the average duration of past bills in that policy area adopted up until the date of the new bill. In our dataset, experienced scrutiny ranges from 1 to 488,Footnote

24 with a mean of 97 days and a standard deviation of 70 days.Footnote

25

$ {}_i $

= mean(duration of passed bills initiated in term A, concluded before T, in area K). In other words, for any observation experienced scrutiny is based on the average duration of past bills in that policy area adopted up until the date of the new bill. In our dataset, experienced scrutiny ranges from 1 to 488,Footnote

24 with a mean of 97 days and a standard deviation of 70 days.Footnote

25

According to our second hypothesis, we expect the effect of experienced scrutiny on late bill initiation to be stronger under higher policy divergence among coalition parties. Measuring policy divergence of coalition parties requires knowledge of the policy positions of the ministerial party in charge of the government bill and the partner parties in the coalition. To measure these area-specific policy positions, we rely on the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) data that cover parliamentary parties since 1945 (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens, Krause, Lehmann, Theres, Merz, Regel and Weßels2019). The CMP splits raw data of party manifestos into quasi-sentences categorized into 56 categories that are used to construct party positions in those categories. Thus, given the availability of manifestos, the CMP data provides term-varying measures of partisan policy positions that parties report themselves.

Because not all categories are informative and distinct, Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) developed a scaling method based on log odds ratios of quantities of quasi-sentences. The scaled policy positions are shown to be superior to the raw measures of the Comparative Manifesto Project. We adopt this scaling approach and recalculate partisan policy positions in 13 ministerial portfolios as in Bäck, Debus, and Dumont (Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011). For each term and each ministerial portfolio, the policy divergence of coalition parties is measured as the sum of portfolio-specific differences between the ministerial party and its coalition partners.Footnote 26 The greater the policy distance between the minister-proponent and her partners, the higher the policy divergence among coalition parties. In our data, the variable coalition policy divergence ranges from a minimum value of 0.02 (almost no divergence) to a maximum divergence of 17.93.

To examine our third hypothesis, according to which we expect a weaker effect of experienced scrutiny on late bill initiation in the face of powerful ministers, we include two new variables: whether the minister’s party holds the median policy position in parliament and the relative size of the minister’s party in parliament. From the other parties’ point of view, these variables approximate the constraints on their capability to scrutinize and amend ministerial bills. According to spatial models, government policy making is highly influenced by the position of the median party in parliament, as long as the median party approximates the median voter’s position (Baron Reference Baron1991; Laver and Schofield Reference Laver and Schofield1990; Morelli Reference Morelli1999). In this sense, a minister holding the median position in parliament should have a greater ability to avoid amendments and bring the government bill closer to her ideal policy position compared with an off-median partner (Laver and Shepsle Reference Laver and Shepsle1996). To capture whether ministers take the median position in parliament, we consider the ordered area-specific positions of coalition parties and code minister median party as 1 if the minister takes the area-specific median position in parliament.

When compared with smaller parties, larger parties in parliamentary systems are usually in a privileged position to scrutinize bills and have a greater floor time for speeches in parliament (Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2008). In several parliamentary democracies, a larger seat share translates into control of more legislative committee chairs, which leads to powers to schedule public hearings and to consult policy experts and societal groups, as well as a privileged position in terms of extracting policy information (Kim and Loewenberg Reference Kim and Loewenberg2005; Martin and Vanberg Reference Martin and Vanberg2004; Reference Martin and Vanberg2005; Mattson and Strøm Reference Mattson, Strøm and Döring1995). As a consequence, larger ministerial parties should be more able to avoid scrutiny and amendments to their bills. We measure the relative size of the minister’s party by her party’s seat share in parliament.

Control variables

Coalition parties may attach different saliency across policy areas that can facilitate coalition formation, portfolio allocation, and common policy making (Bäck, Debus, and Dumont Reference Bäck, Debus and Dumont2011; Klüver and Spoon Reference Klüver and Spoon2020; Klüver and Sagarzazu Reference Klüver and Sagarzazu2016). We use saliency to approximate the incentives to generate position-taking benefits from early bill initiation. When a government bill represents a policy in an area that is more salient to the party of the minister, we expect an early timing of bill initiation; otherwise, when the minister initiates the bill late in the term, she risks forgoing considerable position-taking benefits. Therefore, we control for area-specific saliency based on counting relative mentions of a specific policy category in a given party’s manifesto related to a portfolio that the bill belongs. Following Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011), we log transform the counts so that the measure is robust to extreme values.

Given that opposition parties may also vary in their incentives to scrutinize government bills and thus affect their duration when they collaborate in parliament, we control for the cohesiveness of their policy positions. Specifically, we calculate the variance of the policy positions of opposition parties in parliament. To further account for their party size and policy saliency, we weight the policy positions of opposition parties with their seat shares and the saliency opposition parties attach to different policy areas.Footnote 27 Because the length of terms differs across elections and countries, we also control for observed government duration, measured in days. In Table 1, we show the descriptive statistics of the variables included in our analyses.

Method

To empirically examine the timing of government bills in the cycle of a term, we consider the circular nature of our data.Footnote 28 Following our theory, we treat terms as new cycles of legislative activities, which avoids counting bills from previous terms as bills from a new term. Following Woldendorp, Keman, and Budge (Reference Woldendorp, Keman and Budge2000) and Seki and Williams (Reference Seki and Williams2014), we define a new term by changes in the composition of the coalition government (either by a change in party composition or prime minister).Footnote 29 Unlike linear regression estimators, which ignore the bounds of the dependent variable, and aggregated measures such as counts of bills within a certain period, which risk ecological fallacy, a promising way to analyze our type of data is to use circular regression (Gill and Hangartner Reference Gill and Hangartner2010; Mulder and Klugkist Reference Mulder and Klugkist2017).Footnote 30 Circular regression considers the relative temporal location of government bills within a term when estimating how and to what extent a variable influences the timing of an event (e.g., early or late event) within a cycle.

In our analysis, circular regression enables examining the timing of bill initiation at the government level. To draw inference and quantify the uncertainty of the estimates, we apply a Bayesian version of circular regression, which incorporates priors for posterior sampling using the Metropolis–Hastings sampler (Mulder and Klugkist Reference Mulder and Klugkist2017). Our dependent variable bill timing is a continuous variable on a unit circle ranging from 0 to 2π, which indicates the relative temporal location of a bill on the circle of a term. Our statistical model takes the following form for the estimation of model 1, which examines our first hypothesis on late government bill initiation when the minister has experienced greater scrutiny of her previous bills:

where

![]() $ {\mu}_0 $

on the right-hand side of the equation measures circular intercepts and

$ {\mu}_0 $

on the right-hand side of the equation measures circular intercepts and

![]() $ {g}^{-1}\left(\cdot \right) $

is a transformation function mapping values to the circular space. Although there are multiple choices available for

$ {g}^{-1}\left(\cdot \right) $

is a transformation function mapping values to the circular space. Although there are multiple choices available for

![]() $ {g}^{-1}\left(\cdot \right) $

(see e.g., Fisher and Lee Reference Fisher and Lee1992), we follow the most common practice and assume that

$ {g}^{-1}\left(\cdot \right) $

(see e.g., Fisher and Lee Reference Fisher and Lee1992), we follow the most common practice and assume that

![]() $ {g}^{-1}\left(\cdot \right) $

takes the form of

$ {g}^{-1}\left(\cdot \right) $

takes the form of

![]() $ 2\arctan \left(\cdot \right) $

, with βs as the coefficients to be estimated (Gill and Hangartner Reference Gill and Hangartner2010). X is a matrix of observations on our control variables with parameter estimates vector

$ 2\arctan \left(\cdot \right) $

, with βs as the coefficients to be estimated (Gill and Hangartner Reference Gill and Hangartner2010). X is a matrix of observations on our control variables with parameter estimates vector

![]() $ \boldsymbol{\phi} $

, and

$ \boldsymbol{\phi} $

, and

![]() $ \varepsilon $

is the error term.

$ \varepsilon $

is the error term.

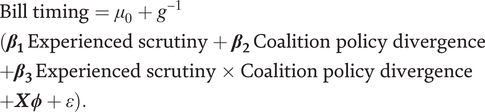

To account for the heterogeneity of the positive effect of experienced scrutiny on late bill initiation by the level of policy divergence between the coalition parties, we consider the interaction between experienced scrutiny and coalition policy divergence. The corresponding estimation examines our second hypothesis with the following specification (model 2):

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\mathrm{Bill}\ \mathrm{timing}={\mu}_0+{g}^{-1}\\ {}({\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{1}}\;\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}+{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{2}}\;\mathrm{Coalition}\ \mathrm{policy}\ \mathrm{divergence}\\ {}+{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{3}}\;\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}\times \mathrm{Coalition}\ \mathrm{policy}\ \mathrm{divergence}\\ {}+\boldsymbol{X}\boldsymbol{\phi } +\varepsilon ).\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\mathrm{Bill}\ \mathrm{timing}={\mu}_0+{g}^{-1}\\ {}({\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{1}}\;\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}+{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{2}}\;\mathrm{Coalition}\ \mathrm{policy}\ \mathrm{divergence}\\ {}+{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{3}}\;\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}\times \mathrm{Coalition}\ \mathrm{policy}\ \mathrm{divergence}\\ {}+\boldsymbol{X}\boldsymbol{\phi } +\varepsilon ).\end{array}} $$

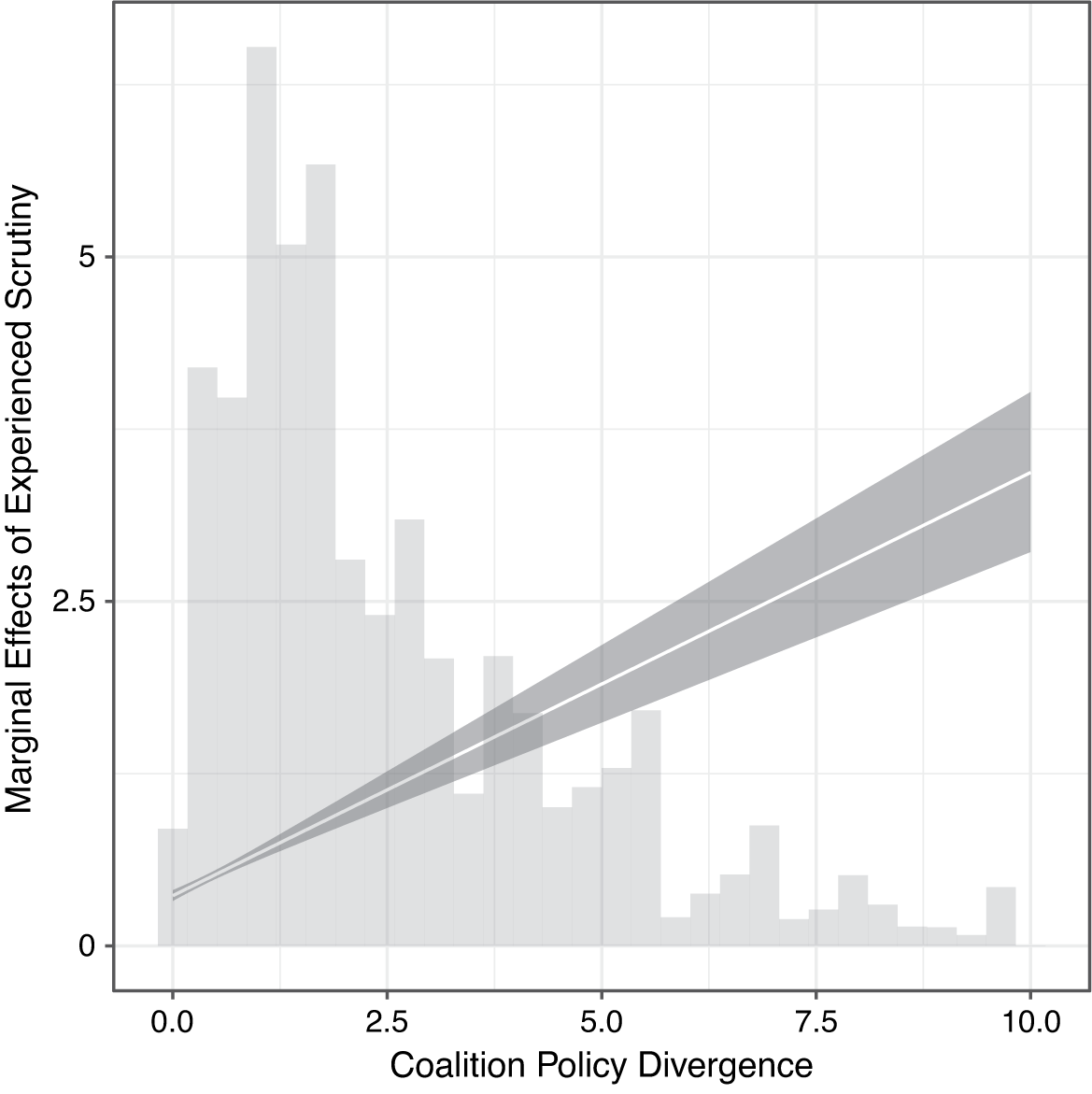

Following our theoretical model and disentangling each effect of interest, we examine hypotheses 2 and 3 separately because policy divergence and ministerial power might affect the relationship between parliamentary scrutiny and timing of bill initiation through different channels: the former directly affects the policy payoffs, whereas the latter determines extent to which the scrutiny action can be executed.Footnote 31 Although policy divergence between the coalition parties magnifies the policy losses the minister incurs in case of scrutiny, the minister’s powers allow her to constrain scrutiny activities to some extent. To examine our third hypothesis on the power of the minister to constrain scrutiny activities, we use two measures of parliamentary powers: minister’s party holding the median policy position in parliament (minister median party) and the size of the minister’s party in terms of their relative seat share in parliament (minister’s party size). This results in the following model 3:

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\mathrm{Bill}\ \mathrm{timing}={\mu}_0+{g}^{-1}({\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{1}}\;\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}+\\ {}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{2}}\;\mathrm{Minister}'\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{party}\ \mathrm{size}+{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{3}}\;\mathrm{Minister}\ \mathrm{median}\ \mathrm{party}+\\ {}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{4}}\;\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}\times \mathrm{Minister}'\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{party}\ \mathrm{size}+\\ {}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{5}}\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}\times \mathrm{Minister}\ \mathrm{median}\ \mathrm{party}+\\ {}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{6}}\;\mathrm{Minister}'\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{party}\ \mathrm{size}\times \mathrm{Minister}\ \mathrm{median}\ \mathrm{party}+\\ {}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{7}}\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}\times \mathrm{Minister}'\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{party}\ \mathrm{size}\times \\ {}\mathrm{Minister}\ \mathrm{median}\ \mathrm{party}+\boldsymbol{X}\boldsymbol{\phi } +\varepsilon ).\end{array}} $$

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}\mathrm{Bill}\ \mathrm{timing}={\mu}_0+{g}^{-1}({\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{1}}\;\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}+\\ {}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{2}}\;\mathrm{Minister}'\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{party}\ \mathrm{size}+{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{3}}\;\mathrm{Minister}\ \mathrm{median}\ \mathrm{party}+\\ {}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{4}}\;\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}\times \mathrm{Minister}'\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{party}\ \mathrm{size}+\\ {}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{5}}\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}\times \mathrm{Minister}\ \mathrm{median}\ \mathrm{party}+\\ {}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{6}}\;\mathrm{Minister}'\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{party}\ \mathrm{size}\times \mathrm{Minister}\ \mathrm{median}\ \mathrm{party}+\\ {}{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathbf{7}}\mathrm{Experienced}\ \mathrm{scrutiny}\times \mathrm{Minister}'\mathrm{s}\;\mathrm{party}\ \mathrm{size}\times \\ {}\mathrm{Minister}\ \mathrm{median}\ \mathrm{party}+\boldsymbol{X}\boldsymbol{\phi } +\varepsilon ).\end{array}} $$

To estimate the models, we run 100,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) iterations and take the first 1,000 iterations as burn-ins. The convergence diagnostics presented in Appendix G make us confident that all chains have appropriately converged.Footnote 32

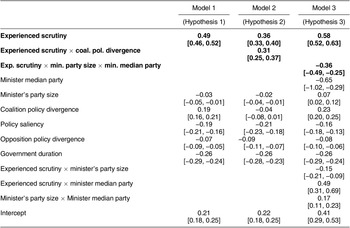

Results and Discussion

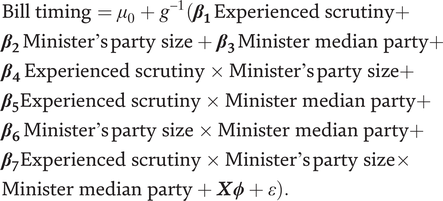

In Table 2, we present the results of our model estimations. The estimates for the independent variables depict the effect of each variable on the timing of the bill initiation (earlier or later in a term), holding all other variables constant. Positive estimates indicate that government bills are introduced later within a term, whereas negative estimates mean that they are introduced earlier within a term.

Table 2. The Effects of Experienced Scrutiny, Coalition Policy Divergence, and Powerful Ministers on Timing of Bill Initiation

Note: Dependent Variable: Temporal location of bill initiations within a term. MCMC run for 100,000 iterations; first 1,000 iterations as burn−ins. Lower and upper bounds of 95% credible intervals in brackets. N: 25,477 government bills.

According to our hypothesis 1, we expect late initiation of government bills the greater the experienced scrutiny of previous bills within a minister’s portfolio. This expectation is supported by the results depicted in model 1 of Table 2. As indicated by the estimate for experienced scrutiny, holding all control variables constant, the greater the experienced scrutiny of their previous bills, the later ministers introduce subsequent bills within the term. This estimate is positive and significant (as the range of values of the estimate does not cross the value of zero between the lower and upper bounds of the 95% credible intervals within brackets). Following our theory, after ministers experience scrutiny and learn that they face a competitive partner type, they are more likely to initiate new government bills late in the term.

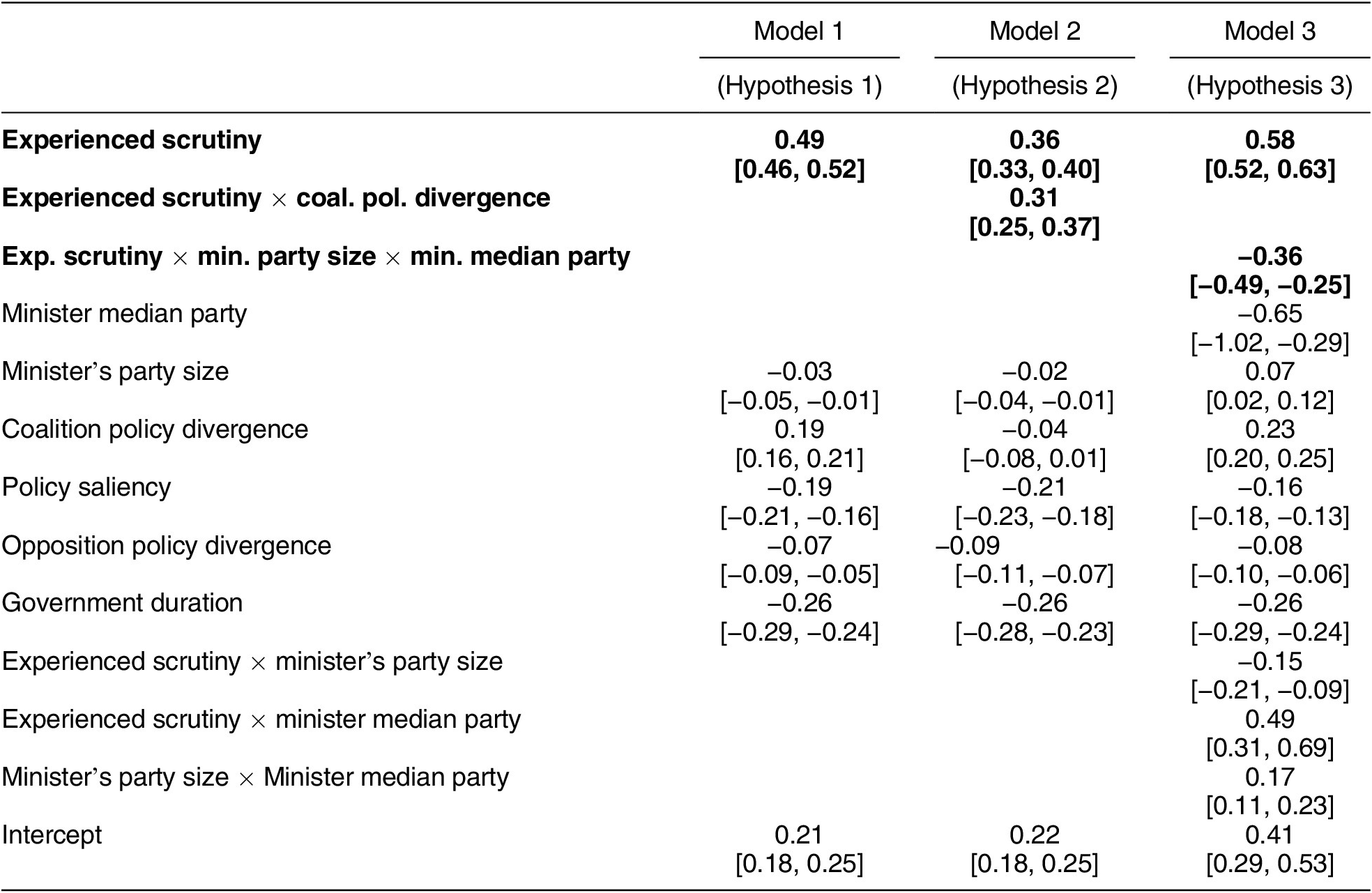

The substantive effect of experienced scrutiny on the timing of bill initiation (as estimated in model 1 of Table 2) is depicted graphically in Figure 3. Within the circle of Figure 3, the periods of the term are represented as percentages (from 0% at the beginning to 100% at the end of the term). The range in the figure goes from 1 to 60—that is, from the minimum to approximately the median value of experienced scrutiny. This range is depicted by the vertical line from the small circle to the larger circle in Figure 3. The blue curve inside the circle shows the predicted value (with a 95% credible interval) of the effect of our covariate on the timing of bill initiation, holding all other variables constant. From the fitted blue curve, we can observe that, on average, an increase in experienced scrutiny from 1 day to 60 days (median value) leads to later initiation of new bills by about 50% within a term.

Figure 3. The Effect of Experienced Scrutiny on the Timing of Bill Initiation

Note: Results based on the estimates presented in model 1 of Table 2. The figure shows that, on average, an increase in experienced scrutiny from 1 day to 60 days (median value) leads to a later initiation by about 50% within a term.

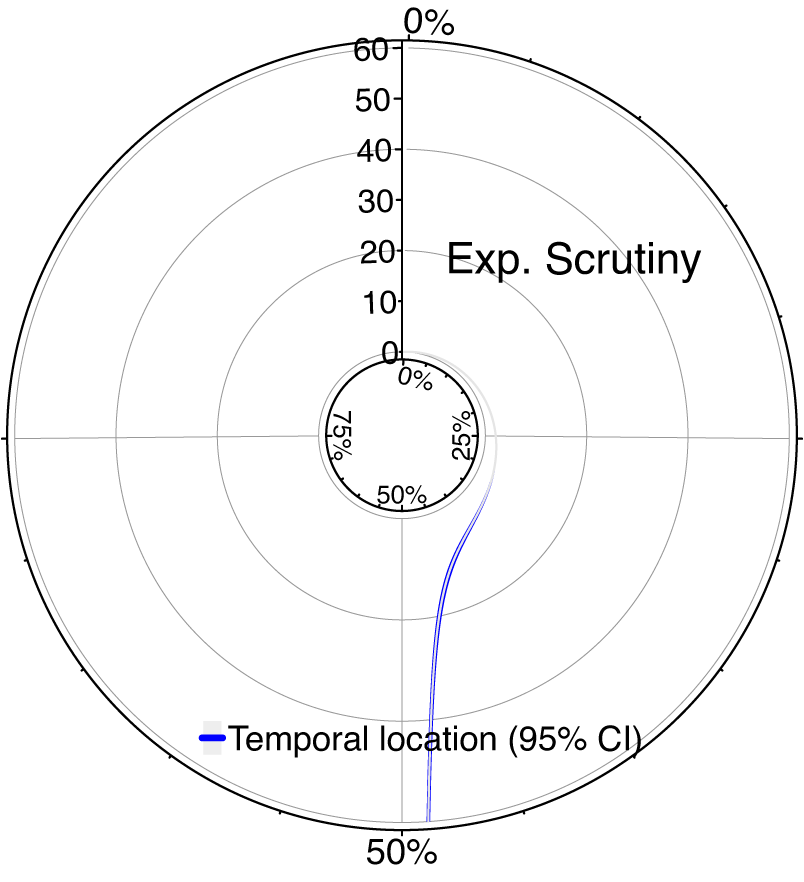

Our analysis so far has supported our first hypothesis, according to which greater experienced scrutiny of government bills results in late initiation of new bills. Based on our second hypothesis, this positive effect of experienced scrutiny on late bill initiation should be stronger the higher the policy divergence between the coalition parties. The result presented in model 2 of Table 2 supports this prediction. The substantive effect of this positive relationship between experienced scrutiny and coalition policy divergence is depicted with a graphical illustration of the marginal effects of experienced scrutiny on the timing of bill initiation (y-axis), conditional on the variation of coalition policy divergence (x-axis) in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Marginal Effects of Experienced Scrutiny on Bill Initiation Timing, Conditional on Coalition Policy Divergence

Note: The higher the coalition policy divergence, the greater the effect of experienced scrutiny on late bill initiation. Results based on the estimates presented in model 2 of Table 2. The vertical bars in the background of the figure depict the distribution of the variable coalition policy divergence.

Figure 4 highlights our finding that the effect of experienced scrutiny on late bill initiation (based on the positive fitted line with a 95% credible interval) is enhanced by a higher policy divergence within the coalition government, holding all control variables constant.Footnote 33 The positive slope depicted in Figure 4 suggests that in an environment comprised of competitive partners, late initiation of government bills becomes more predictable the higher the policy divergence among the parties that comprise the coalition government.

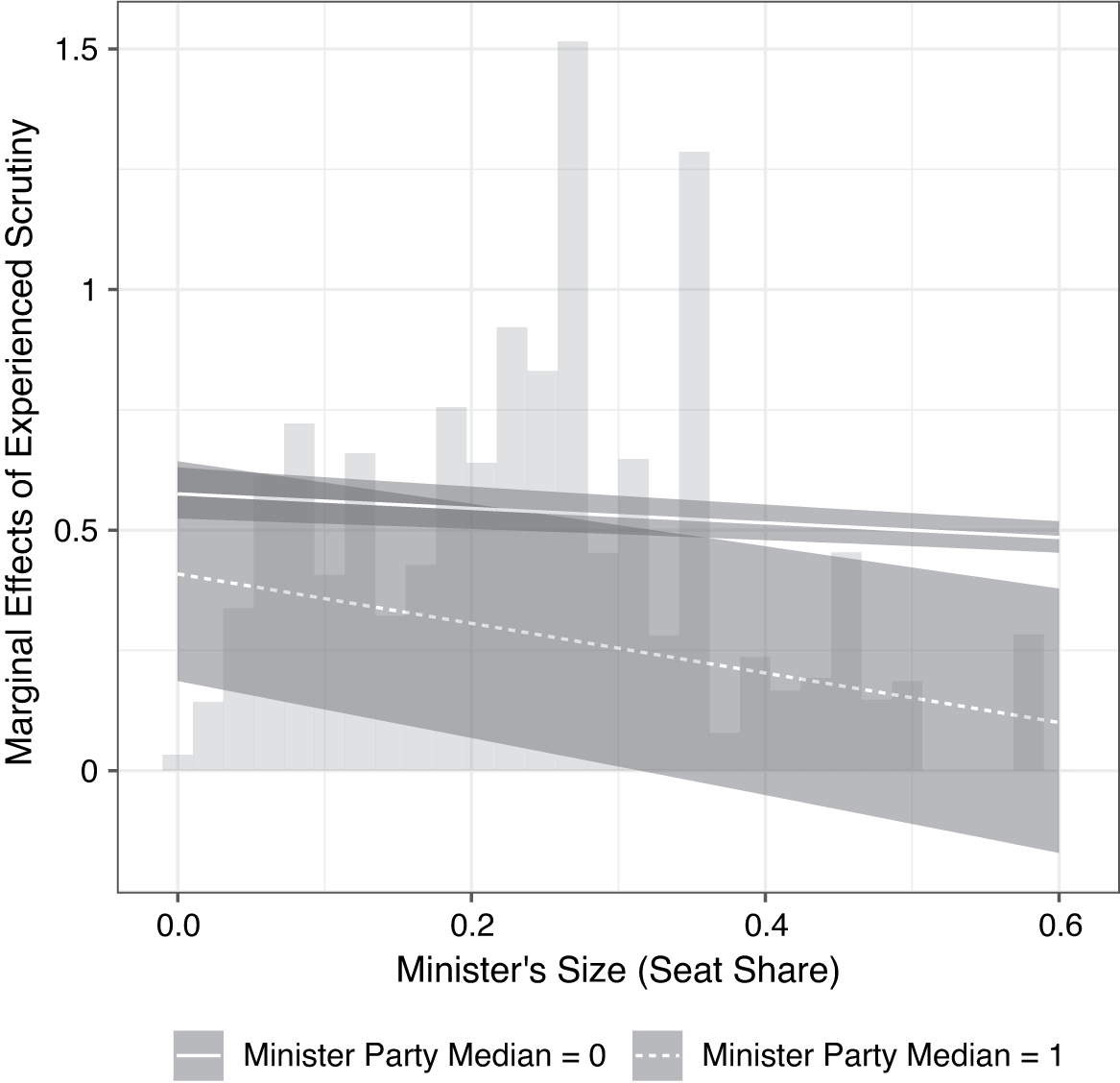

According to our third hypothesis, if the minister has powers to constrain or preclude scrutiny activities in parliament, we should observe a weakening in the positive effect of experienced scrutiny on late bill initiation. To examine this prediction, we approximate the parliamentary powers of the minister by her party holding the median policy position in parliament and by her party’s relative size in terms of parliamentary seat share. In support of hypothesis 3, we can see in model 3 of Table 2 that the effect of experienced scrutiny on late initiation is substantially reduced when we add a triple interaction to our model between experienced scrutiny, minister’s party size, and minister median party. We can better depict this result by interpreting the marginal effects of experienced scrutiny on the timing of bill initiation, conditional on the variation of both minister’s party size and minister median party (see Figure 5 below).Footnote 34

Figure 5. Marginal Effects of Experienced Scrutiny on the Timing of Bill Initiation, Conditional on the Minister’s Party Size and Minister Median Party

Note: The vertical bars in the background of the figure depict the distribution of the variable minister’s size (seat share).

The solid-line slope in Figure 5 depicts the marginal effects of experienced scrutiny on the timing of bill initiation (with a 95% credible interval) when the minister’s party does not hold the median policy position in parliament, conditional on the size of the minister’s party. The dashed-line slope depicts the marginal effects of experienced scrutiny on the timing of bill initiation (with a 95% credible interval) when the minister’s party holds the median position in parliament (i.e., minister median party equals 1), conditional on the size of the minister’s party. As highlighted in Figure 5, the positive effect of experienced scrutiny on late bill initiation becomes weaker the greater the size of the minister’s party in parliament. Moreover, this effect is further weakened when the minister’s party holds the median policy position in parliament. More precisely, when the party of the minister holds the median policy position in parliament, the magnitude of the effect is indistinguishable among small ministerial parties (as indicated by the two predicted lines overlapping for ministerial parties holding less than 35% of the seats). However, as the minister’s party holding the median policy position in parliament becomes larger (in our case, controlling more than 35% of the seats), the positive effect of experienced scrutiny on late bill initiation becomes smaller, eventually nonsignificant when approaching the maximum value for minister’s party size in our sample (0.59). This result supports our hypothesis 3 and reveals the importance of considering both the median policy position and the size of the ministers’ party when examining our expectation that powerful ministers are capable to incur less scrutiny and have fewer incentives to initiate bills late in the term.

The results from our control variables also present interesting and expected patterns. Holding all other variables constant, bills addressing policy areas of high saliency for the ministerial party are, on average, initiated earlier within the term (indicated by the negative and significant estimate for policy saliency). As these bills are probably highly visible to the constituencies of ministerial parties, this underlines their strategy of generating position-taking benefits by early bill initiation. A higher share of parliamentary seats also seems to translate into earlier initiation of bills, as indicated by the negative and significant estimate for minister’s party size in model 1 and model 2 of Table 2. Furthermore, the greater the policy divergence between parties that comprise the opposition (opposition policy divergence), the earlier the minister introduces a government bill. This is also to be expected because a lower cohesiveness of opposition parties reduces the risk of scrutiny and thus allows ministers to generate position-taking benefits. The negative and significant estimate for government duration can be interpreted as constraints of the electoral calendar and voter demands imposed on the minister. The minister cannot delay her bills indefinitely at the risk of not having time before the next election to approve her policy agenda and being penalized by her constituency in the election. Thus, as the term passes by, the likelihood that ministers will initiate government bills increases. Another explanation that we cannot dismiss is that the effect of observed government duration might be driven by very short-lived coalition governments, which inevitably have less time to initiate bills.Footnote 35

To test the consistency of our findings, we have conducted several robustness checks, which are presented in Appendix II: Goodness of Fit and Robustness Checks of the supplementary material. The results from these robustness checks strengthen the main findings (presented in Table 2)Footnote 36 of this study on the dynamic temporal perspective on coalition policy making, giving us confidence that ministers initiate bills later within a term when their past bills have experienced greater scrutiny and that this positive effect of experienced scrutiny on late bill initiation is stronger the greater the coalition parties’ incentives to implement their ideal policy positions (i.e., the higher the policy divergence between the coalition parties) and the less powerful that ministers are to preclude scrutiny activities in parliament.

Conclusion

We developed a conceptual framework to study the temporal dimension of democratic governance and analyzed the timing of government bill initiation in parliamentary democracies. Our dynamic temporal perspective can be applied to other political phenomena and contexts in which policy makers learn about their counterparts from their experiences within a prescribed period such as parliamentary sessions, legislative terms, and other decision-making processes. Compared with the predominant one-shot analyses of their policy-making interactions, we model and examine the temporal interaction between a proposer and the type of her counterpart. We assume that the proposing policy maker does not know whether she is confronted with a competitive or cooperative partner type at the beginning. Over time, however, she may learn the partner’s type from experiencing responses to her proposals and adapt her behavior by timing the initiation of subsequent proposals.

Although our analysis follows the rules of parliamentary democracies by fixing the duration of the term, during which the proposer learns about her partner’s type, our theory can be extended to consider endogenous duration with the partner having an exit option that may trigger the collapse of the partnership. The equilibrium behavior will then depend on costs or benefits incurred from termination and might affect the proposer’s incentives for later initiation. We believe that this topic is a promising avenue for future research on the temporal dimension of democratic governance.

According to our analysis of the timing of government bill initiation, the agenda setter forms a belief about her partner’s type after experiencing scrutiny to her bills and times her further bill initiation based on (1) her belief in facing a specific partner type, (2) the policy incentives her partner has to challenge her bills, and (3) her powers to preclude the scrutiny of her bills.Footnote 37 Compared with existing theories on coalition governance, our dynamic temporal perspective introduces an additional learning channel to derive hypotheses on policy-making experiences of ministers and their responses to the type of partner they face during the term. The empirical results lend support to our predictions based on evidence from 11 parliamentary democracies, demonstrating that proposing ministers learn about the type of their coalition partners from experienced scrutiny and adapt their bill initiation behavior and timing over a term. Our sample differs in size, wealth, culture, history, and democratic foundation of parliamentary democracies under coalition governments. Given a large sample of government bills, our data can be further updated and applied to other political activities that allow for learning over time.

Methodologically, we demonstrate that rather than imposing strong assumptions on linear estimators, we can account for the cyclical structure of our data by using a Bayesian circular regression model. Because democratic governance imposes temporal limits to policy-making activities, we estimated the relative temporal location of observed bill initiation to examine the empirical implications derived from our dynamic theory. We hope that the use of this method encourages further studies adopting a temporal perspective, which we believe is suited for a broader scholarship using data of cyclical nature in political science such as data on electoral, legislative, congressional, and parliamentary terms. Beyond the adequacy of our methodological approach, in the supplementary material we provide model extensions that highlight the stability of our empirical implications theoretically and also conduct several robustness checks that strengthen our main empirical findings on the timing of bill initiation.

In addition to our methodological and empirical contribution, we believe that our theoretical focus on the temporal dimension of policy making can stimulate further research on democratic governance. This temporal dimension implies that policy makers attempt to optimize their behavior by timing their activities, which—in our case, of coalition governments—depends on the type of their partnership. Similar dependencies may exist from other counterparts, such as opposition parties, bicameral actors, presidents, or courts. Furthermore, the optimal behavior of these actors may change over time and differ across policy areas wherein policy makers can experience other types of dependencies such as from the voters, interest groups, or international actors. Apart from additional applications to other phenomena, we hope that our parsimonious dynamic setting will encourage scholars to extend our theory for the study of more complex interactions of democratic governance.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000897.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Replication files, including R code and data, are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/OFCAAE.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For their helpful comments and suggestions, we thank the APSR editorial team, four anonymous reviewers, and the participants of the panel “The Strategy of Coalitions” at the 11th Annual Conference of the European Political Science Association (EPSA). We thank Mariyana Angelova and Frank Marczewski for their help with data collection. We also acknowledge support by the state of Baden-Württemberg through bwHPC computing infrastructure.

The authors contributed equally, and their names are ordered alphabetically.

FUNDING STATEMENT

The authors acknowledge funding support from the German Research Foundation (grant number 139943784) via Collaborative Research Center (SFB) 884, “The Political Economy of Reforms” (Project C1: Legislative Reforms and Party Competition) at the University of Mannheim.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.