Lobby laws are a kind of governance policy. Such policies determine how officials perform their jobs or how government is structured, and not the laws or policies those officials produce. Other examples include campaign finance restrictions, the adoption of direct democracy, term limitations, and tax and expenditure limits.Footnote 1 Although the public generally favors good-government reforms, the laws often restrict policy makers’ autonomy.Footnote 2

Political scientists have sought to understand how these reforms are enacted initially over the objections of legislators and other political elites. Given major agenda-setting events such as political scandals, legislators occasionally approve of limits on their power or personal privileges, including by regulating lobbyists. Otherwise, these reforms are sometimes enacted via citizen initiative. Additional hypothesized causes for reforms include long-term cultural factors such as moralism, ideology, and public opinion.Footnote 3

Narratives of lobby reform from New York, Georgia, and Michigan provide an alternative solution for the dilemma: why would presumably self-interested lawmakers ever enact any regulations on lobbying?Footnote 4 Although new regulations may be initiated and approved by voters, legislators also enact such regulations from time to time. The narratives show that different kinds of lobby regulations (i.e., transparency) are adopted by legislators before other kinds of regulation. When unpredictable agenda-setting events such as political scandals occur, there is public pressure for lobby regulation. Typically, the first form of regulation adopted by legislators is the least harmful for symbiotic relationships between lawmakers and lobbyists. Simple transparency laws do not prevent scandals perfectly, however, and with additional agenda-setting events and public pressure, additional regulations are adopted, including limitations or bans on some lobby activities. Within the individual states, existing sets of laws (regimes) shaped subsequent sets of laws and formal deregulation of lobbying did not occur. Thus, repeated agenda-setting events gradually contributed to lobby regulation in the presence of self-interested lawmakers and lobbyists and absence of popularly initiated regulations.

In addition to providing tentative answers to a paradox of political reform, this study advances scholars’ understanding of lobby regulation by drawing attention to a neglected distinction between two different kinds of regulation: transparency laws and prohibitions on lobby activities. Existing research assumes that disclosure and limitations are equally important for political representation. For instance, Joshua Ozymy identified various factors that help explain the adoption of new lobby laws but treats disclosure laws and limitations of lobbying similarly.Footnote 5 In identifying sources of campaign finance reform, Christopher Witko also places transparency (e.g., reporting requirements) and limits on the same scale.Footnote 6 The two kinds of laws affect lobbyist–legislator relationships in different ways, however, as regulations that limit or prohibit various lobby activities more effectively undermine symbiotic relationships between lawmakers and lobbyists. Legislators have less to lose from the disclosure of lobby activities than from limits or outright bans on lobby activities. In New York, Georgia, and Michigan, once basic transparency laws were adopted, lobbyists or lawmakers actively opposed the adoption of additional laws that would limit or ban some lobby activities. Although events in the three states are not intended to show that legislators will seek to undermine the adoption of lobby regulations everywhere or for all time, they show that different kinds of lobby laws are more credible threats to symbiotic relationships than others are. Mario Cuomo of New York summarized this situation clearly in 1977: “[L]obbying laws are not popular with most office holders. They are regarded as a nuisance and embarrassment. They inevitably irritate some powerful and politically important interest groups. As a result, real reform in the past has been regularly shunned and, when necessary, vigorously resisted by those whose activities it would regulate.”Footnote 7

Lobby Regulation Origins

Regulations on legislative lobbying, including transparency and limitations on various activities, threaten to undermine symbiotic relationships between incumbent legislators and allied advocates. Laws that require lobbyists to register and disclose the details of their activities allow the public to inspect informal exchanges between lawmakers and lobbyists that involve gifts, campaign donations, and legislative activities. Other kinds of regulations limit these activities directly, such as by placing caps on the value of gifts or donations. In general, lobby regulations are argued to reduce lobbyists’ influence over legislators and lead to laws that better reflect the preferences of local voters.Footnote 8

In the case of lobby reform, legislators and lobbyists have strong reason to object to regulations on lobbyists, including their campaign finance activities. Legislators benefit personally from symbiotic relationships with lobbyists. Such relationships often involve personal gifts (historically) and campaign donations given in exchange for meeting time and legislative activities.Footnote 9 For decades, scholars have noted that lobbyists tend to solicit members of Congress who already favor their clients’ interests.Footnote 10 Over years, professional relationships built on trust and shared interests develop, especially in less professional assemblies like state legislatures.Footnote 11 Although there is mixed evidence that campaign donations buy roll-call votes, such donations do appear to affect legislator priorities during committee meetings or lead to more meetings with legislators and high-ranking staff persons, at least in Congress.Footnote 12 The stickiness of relationships helps to steer campaign donations: donations follow members of Congress even when they change committees.Footnote 13

Although lawmakers and lobbyists have reason to object to regulations on lobbying, there are multiple kinds of lobby regulation. The first kind consists of transparency laws. Examples of such laws include registration and reporting requirements. The primary rationale for lobby transparency is the assumption that, in a democracy, the public interest is best served when political information is shared with voters.Footnote 14 Ideally, lobbyists’ activities are disclosed and monitored by members of the public, including the press and good-government organizations. With such monitoring, members of the public determine ethical standards in government (e.g., the sizes of improper gifts or contributions) and react accordingly by punishing lawmakers electorally for committing indiscretions. The second kind of lobby regulation consists of limitations or prohibitions on lobbying activities. As examples, some state laws prevent lobbyists from making campaign contributions during legislative sessions and other laws impose limits on the value of meals or gifts or honoraria for speeches.Footnote 15 Such limitations may also be applied to relationships between lobbyists and their clients, with an example being bans on contingent fee contracting. These limitations delineate ethical standards directly for lobbyists.

Self-interested lawmakers and lobbyists should prefer transparency over limitations or prohibitions for two reasons, regardless of how well lobby regulations are enforced generally. First, even with a wealth of lobby information, members of the public may not be able to process lobby information or may not be able to determine ethical standards collectively. Jana Kunicová and Susan Rose-Ackermann suggest that voters provide oversight of incumbent officials and, in response to corruption, penalize officials electorally.Footnote 16 Such monitoring and penalizing, however, require voters to overcome collective-action problems. With transparency, ethics in government is a public good that is provided by members of the public.Footnote 17 Moreover, even with transparency, voters may not agree collectively regarding the sizes of inappropriate gifts or donations. Second, disclosed lobby information may be unwieldy and not readily indicate which lobbyists achieve influence. Even political scientists measure influence in different ways.Footnote 18 The mere availability of lobby information may prove useful only for preventing the most blatant or outrageous forms of vote buying: lobbyists may exercise influence in more subtle ways such as by giving smaller gifts, or even useful information, to lawmakers on a repeated basis.

Lawmakers and lobbyists’ preference for transparency over limitation persists even if lobby regulations are not enforced generally. Lobbyists may comply with lobby laws voluntarily to enhance their reputations.Footnote 19 Today, lobbyists register on a voluntary basis in the European Union and United Kingdom. Lobbyists may also comply voluntarily with lobby regulations to help dissuade legislators from adopting more burdensome regulations. Alan Rosenthal argues briefly that organizations representing lobbyists or government-affairs professionals published standards for ethical conduct during times when lawmakers were considering enacting regulations.Footnote 20 For the same reasons, lobbyists may comply with limitations or prohibitions that are not enforced. Such laws still delineate ethical standards, and lobbyists seek to preserve their professional reputations or seek to prevent the enactment of stricter regulation.

If lawmakers and lobbyists object less to transparency than to limitations or prohibitions, then what might the historical adoption of lobby regulations look like? As Joshua Ozymy proposes, unpredictable agenda-setting events, among other factors, can lead to reform.Footnote 21 The role of political scandals in bringing about new lobby regulations has been documented well, with the public being said to have demanded reforms in light of salient investigations of political corruption (similar to “policy tragedies,” in the parlance of Daniel Carpenter and Gisela Sin, but with criminal proceedings for one or more officials).Footnote 22 Moving beyond existing accounts, however, legislators first choose to regulate lobbyists via transparency rather than limitations or prohibitions and may try subsequently to undermine those laws once the salience of agenda-setting events dissipates. Such regulatory backsliding may be subtle or hidden from public view, but sets of formal lobby laws (regimes) influence subsequent laws. For formal regulation, every additional step raises the floor for regulation such that legislators cannot weaken the laws and avoid a public backlash. Additional events or other factors such as policy entrepreneurs allow for additional regulations beyond transparency.Footnote 23 This is a narrative of gradual regulation or incrementalism due to elite self-interest.

A seemingly alternative narrative of lobby regulation adoption is that elected officials innovate or respond to how lobbyists influence lawmakers, with lobbyists’ methods changing over time.Footnote 24 Although this narrative downplays the tension between lawmakers’ self-interest and the regulation of lobbyists, it is not mutually exclusive with the narrative of incremental policy change because agenda-setting events or policy entrepreneurs may identify or reveal (for the public) the new methods of influence and additional events or entrepreneurs may be needed for additional policy change (as the scale or nature of lobbying changes). Another narrative of policy change is that states learn from each other and that policies diffuse throughout states gradually based on predictable patterns.Footnote 25 This narrative, too, neglects the self-interested nature of lawmakers and lobbyists. For governance policies where lawmakers and lobbyists may prefer the status quo because of self-interest, policy innovation may be slower. If transparency laws are less threatening to symbiotic relationships than other kinds of lobby regulations, then such laws may diffuse more quickly throughout the states.

An objection to the narrative of incrementalism is that antibribery statutes (i.e., not transparency laws) were among the earliest forms of lobby regulation adopted in the states. However, those laws were typically vague, “incomplete, and ultimately self-defeating.”Footnote 26 They sought to prevent explicit quid pro quo agreements but not the more typical practice in which lobbyists build relationships through gifts or contributions without any explicit vote buying.

Three Histories of Lobby Regulation

The histories of regulation in New York, Georgia, and Michigan provide examples of lobby laws, including both registration requirements and limitations, being vigorously opposed or undermined by legislators or lobbyists. These three states were not randomly selected but reflect different political cultures, institutions, and partisan contexts. Daniel Elazar argued that New York contains an individualistic culture in which voters expect government to solve the problems of individual people and care less about political patronage or corruption.Footnote 27 In contrast, in states with moralistic political cultures, such as Michigan, voters are argued to see government as a means for solving collective problems and care more about preventing corruption. Georgia was argued to have a traditionalistic culture in which voters see government as a means of reinforcing social order and hierarchy and where voters are less concerned with political participation than voters elsewhere. Moreover, the legislatures in the three states varied substantially in terms of legislative staff resources and party control. Whereas New York and Michigan contained relatively professional legislatures throughout the period of lobby law implementation, Georgia’s legislature was amateurish.Footnote 28 In New York, the legislature was traditionally dominated by Republicans but split by the mid-twentieth century. Michigan’s legislature was dominated even more so by Republicans but became competitive over time. Georgia’s was a one-party legislature dominated by Democrats until the late twentieth century.Footnote 29 The purpose of choosing such varied states is to show that lobby regulations incurred opposition from lawmakers and legislators across diverse contexts, including in states where voters presumably would care more about political corruption and where transparency laws would accordingly limit influence more effectively.

If legislators and lobbyists prefer transparency over limitations and prohibitions, then the adoption of lobby regulations in New York, Georgia, and Michigan should reflect this preference. Transparency should have been adopted before other kinds of laws, but legislators and lobbyists may have nevertheless sought to undermine any kind of lobby law once it was enacted. The three histories of lobby reform present evidence for an incremental policy process that may explain and describe how lobby laws were adopted elsewhere.

New York

New York’s first lobby law was enacted due to political scandal. Internal dissensions within the Equitable Life Insurance Company had been publicized in major newspapers, and related investigations revealed a variety of unethical business practices. Under popular pressure, Governor Frank Higgins encouraged the legislature, in July 1905, to form a committee to investigate the activities of all insurance companies headquartered in the state. Named after its chairman, the Armstrong joint legislative committee was formed in September 1905 and organized a series of public hearings into corporate governance and political activities, especially those of life insurance companies. The hearings, in which Charles Evans Hughes served as chief counsel for the state and questioned witnesses, attracted widespread attention from the press and public.Footnote 30 The hearings found that insurance companies had made large political contributions to state and national campaigns using funds earmarked for policyholders. This news produced great interest and consternation among members of the public. Ultimately, the committee recommended various changes in how insurance companies were structured and regulated, prohibitions on political contributions from incorporated firms, and registration requirements for lobbyists. Among the earliest laws adopted in response to the report, legislators enacted a lobbyist registration law in 1906.Footnote 31 The committee’s report is best remembered, however, for helping to spur national interest in campaign finance, with Congress enacting its first ban on corporate campaign contributions: the Tillman Act of 1907. Following developments in Congress, the New York legislature also enacted a similar ban, but this law targeted the contributions of corporations and not lobbyists per se.

Regarding lobbyists, the 1906 act required the secretary of state to maintain a docket in which everyone who was being paid to lobby or testify before committees had to register (i.e., record their names and clients). Lobbyists also had to record the subject matter of their efforts. Moreover, the employers of lobbyists had to produce statements detailing the expenses incurred in connection to promoting or defeating legislation. Such statements were to be sent to the Secretary within thirty days of the legislature adjourning. Violating the act would incur a misdemeanor, a fine of not more than $1,000, and disbarment from lobbying for a period of three years. The employer would also have to pay $100 for every day beyond the filing deadline that its expense report was late. Although these penalties were clearly outlined, the act did not specify which agency was responsible for the law’s enforcement. The law was effectively voluntary but addressed ephemeral concerns over political corruption.

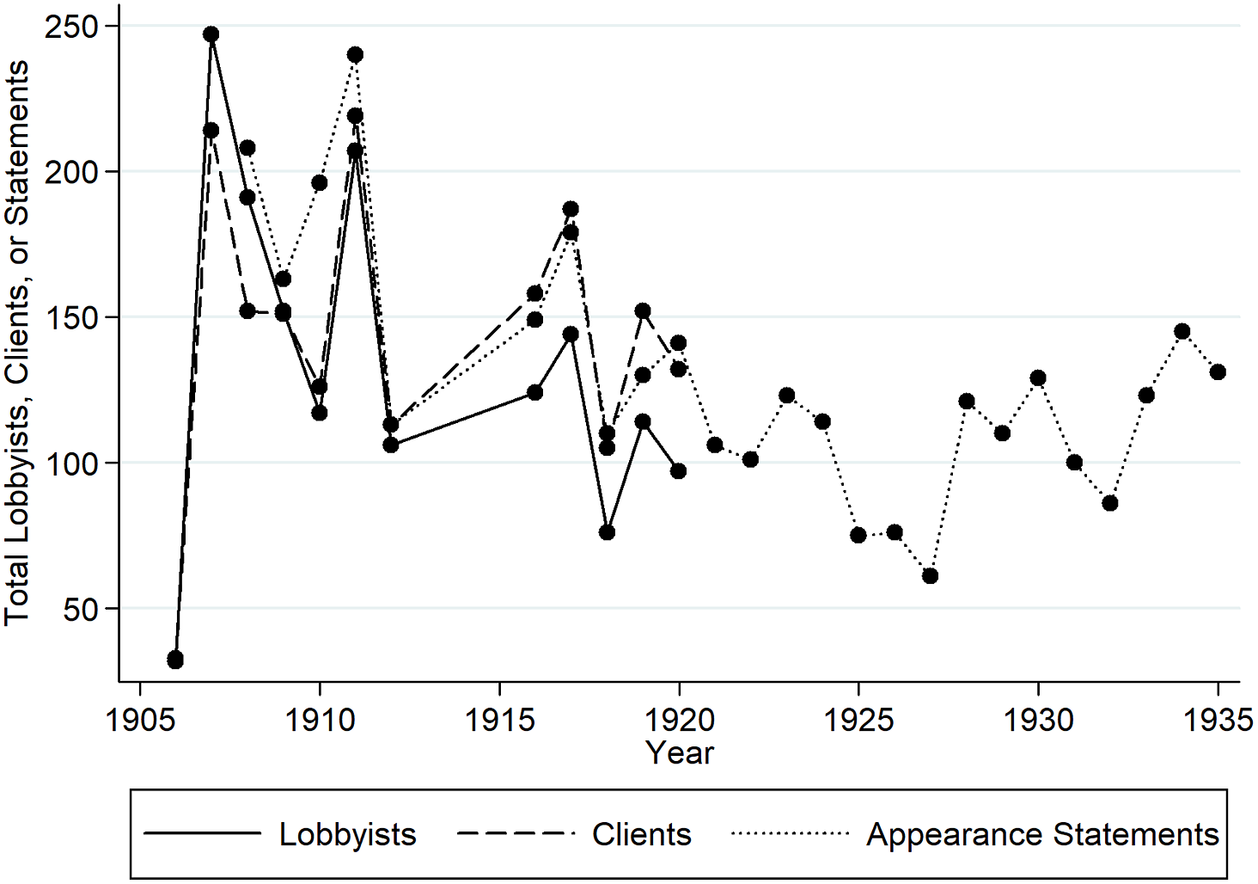

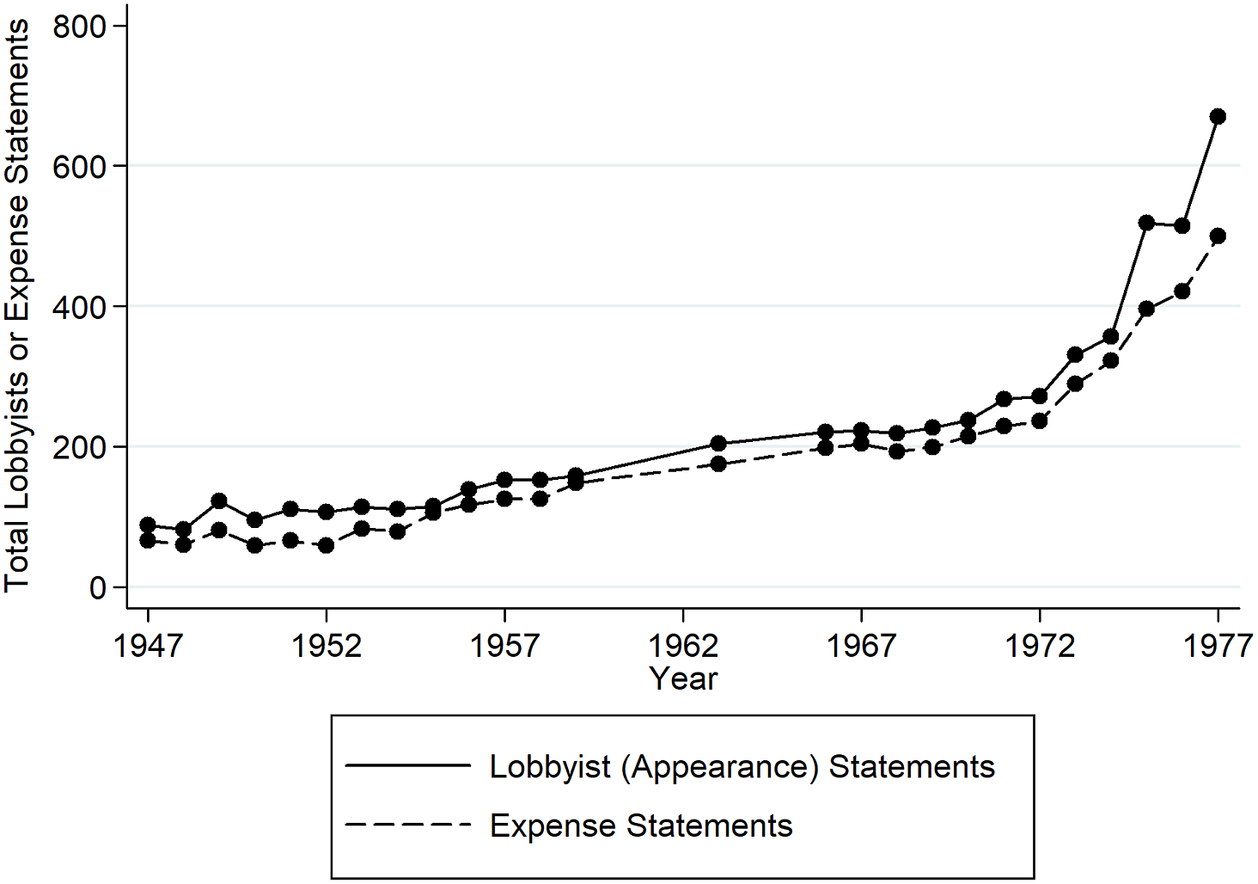

New York’s law compelled few interests to register because it was effectively unenforced prior to 1975. According to Belle Zeller, “the law [was] broken with impunity.”Footnote 32 Even though lobbyists and their employers submitted expense statements, no one verified the timeliness or accuracy of the reports. Zeller found that more than a third of all registered lobbyists in 1931, for instance, either failed to file expense reports or submitted them after the deadline. There were no penalties for those not in compliance, and a similar percentage of registrants failed to submit statements the following year. James Pollock also noted that the law was not “sufficient to cope with the problems … of innumerable lobbyists.”Footnote 33 Figure 1 shows the total numbers of lobbyists and clients who appeared in New York’s legislative docket from 1906 to 1935. The docket is preserved in the state archives. The figure also shows the total lobbyist appearance statements submitted between 1908 and 1935.Footnote 34 Better, Zeller provided the statement totals, originally reported by the secretary of state.Footnote 35 Figure 2 provides the totals for 1947 to 1977. The appearance statements may be treated as approximations for how many individuals registered as lobbyists, and the expense statements may be treated as approximations for client totals.

Figure 1. Lobbyists, Clients, and Appearance Statements in New York, 1906–1935.

Figure 2. Lobbyist and Expense Statements in New York, 1947–1977.

New York’s lobby law was unenforced until March 1975. Riding a wave of anticorruption sentiment (numerous states had begun to reform their lobby laws since the Watergate hearings), newly appointed Secretary of State Mario Cuomo began to enforce the law and call for reform. The secretary’s office returned more than 270 lobbyist (appearance) statements back to filers as containing insufficient information. The office also returned 50 expense statements and forwarded the names of 19 employers who had not filed statements to the attorney general. For the first time, penalties were imposed: a total of $8,100 was collected. The enforcement of New York’s lobby law during the 1975 legislative session explains the jump in lobbyist and expense statements submitted that year.

The secretary of state continued to enforce the 1906 law and insisted that a new lobby law be enacted until the legislature passed the Lobby Registration and Disclosure Act in 1977. The New York Temporary State Commission on Lobbying assumed monitoring and enforcement responsibilities. The six-person Commission was granted both resources and authorization to enforce lobby transparency. It was granted an initial budget of $150,000 and was allowed to conduct investigations, subpoena witnesses and documents, hold hearings, and issue advisory opinions, among other functions. Also, as part of the new law, lobbyists had to report the details of their spending and expenses every three months. Over time, New York’s lobby law was strengthened further with restrictions on lobbyists. By September 2007, as part of the Public Employee Ethics Reform Act, the Commission was combined with the New York State Ethics Commission to form the New York State Commission on Public Integrity. As part of the act, violations for certain penalties were quadrupled and various gift bans were imposed. Legislators were prohibited from accepting personal gifts from lobbyists and “honoraria” for giving speeches.

Georgia

In Georgia, despite the passage of a lobbyist registration act, the legislature discouraged lobbyists from registering by not enforcing the act and imposing a hefty registration fee. For six decades, the lobby law was largely ignored. Original registration records, newspaper accounts, and interviews conducted with various state officials by Calvin Kytle and James Mackay all reveal widespread noncompliance with the statute.Footnote 36

Georgia’s first proposed lobby regulation was introduced in the House of Representatives in 1907. The bill was modeled on a recently enacted law in Missouri that required registration, and a faction of Georgia legislators sought to replicate that state’s success in quelling voters’ concern over lobbying.Footnote 37 The statute, as originally proposed, required every person making a legislative appearance to sign their names in a docket maintained by the secretary of state and record the names of their clients and the subject matters of their lobbying. Within two months of legislative adjournment, lobbyists’ employers were also required to submit “itemized statement[s] … showing in detail all expenses paid or incurred” in connection to their lobbying. The original statute prohibited lobbyists from meeting privately with legislators such that all appearances had to occur in public during committee hearings or be expressed in writing, but this provision was not included the Senate’s version of the bill.Footnote 38 With the House and Senate in disagreement, the bill was reintroduced during subsequent legislative sessions. A version merely requiring registration and expense reporting was eventually approved by both chambers. The only restriction in the bill prevented lobbyists from being on the floors of the House or Senate during legislative sessions. The bill was signed by Governor Hoke Smith on August 19, 1911, as Public Act 269.

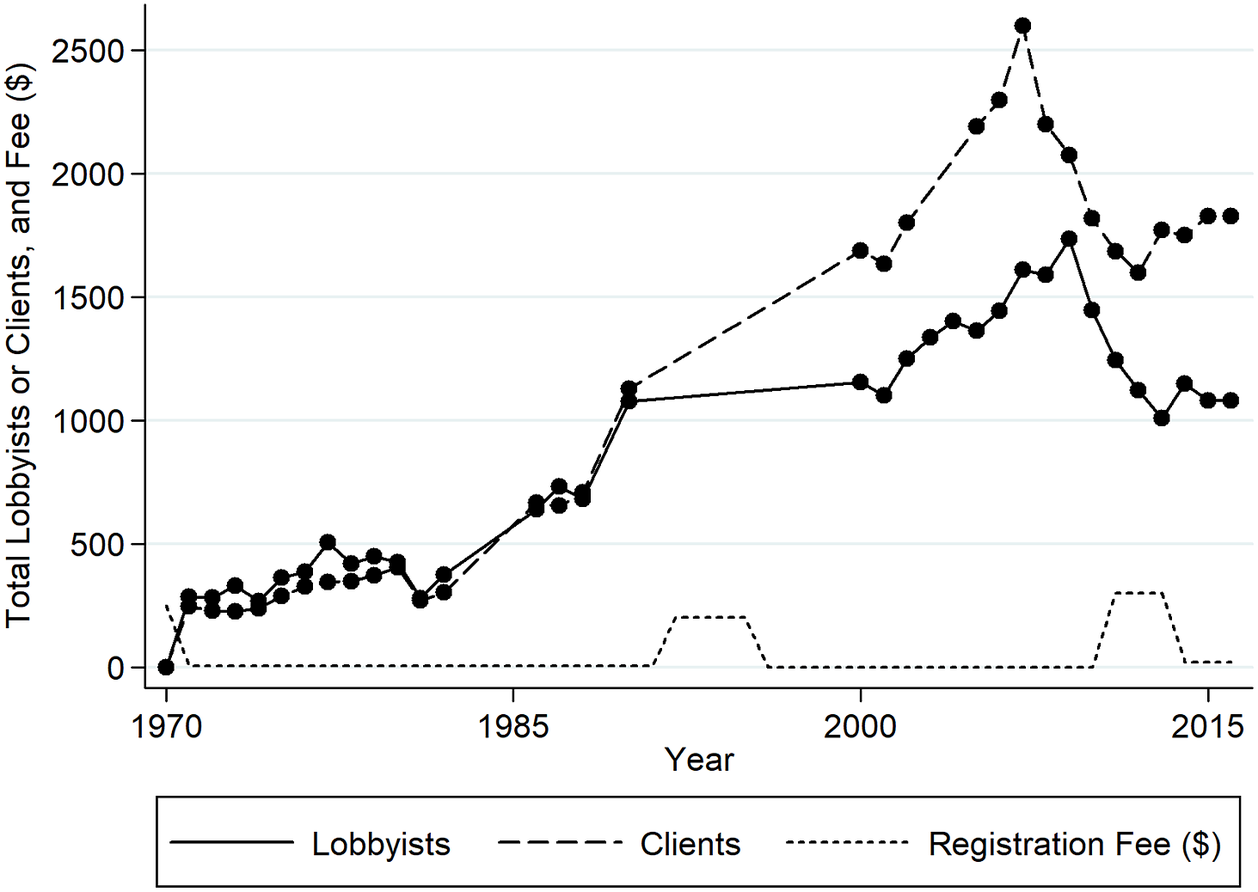

Initially, more than 200 lobbyists representing roughly 125 unique interests registered in the secretary’s docket. Registrations plummeted as the legislature did not seek to enforce the act and instead required registrants to pay a hefty fee. The state’s constitution from 1877 had declared “lobbying” a crime and granted the legislature the ability to define which lobby activities were criminal in nature and to determine appropriate penalties. The legislature subsequently defined lobbying as appeals to legislators based “on corrupt means” (i.e., bribery, or appeals not based on reason or argument). A representative argued in 1918, however, that the provisions of the constitution and those of the 1911 act were irreconcilable. The legislature subsequently included a tax of $25 on registered “legislative agents” in a set of amendments to the tax code.Footnote 39 Figure 3 shows the total number of individuals who registered as lobbyists, the number of client organizations they claimed to represent, and the registration fee in nominal dollars, for years 1912 to 1970. The docket reveals that many of the registrants for 1912 were citizen activists who registered for various purposes such as the creation of new counties, changes of jurisdiction for local courts, and for a bill banning child labor. The tax amendments enacted in 1918 required lobbyists to pay $25 when registering. This fee was increased to $100 in 1922. With the 1929 session, registered agents had to pay $250. As the fee increased, both the totals of lobbyists and the variety of clients registered decreased precipitously. In 1941, only four lobbyists registered. No more lobbyists registered until 1970. The fee did not deter lobbyists. Instead, lobbyists avoided registering because of poor enforcement. During a 1947 interview, Georgia Attorney General Eugene Cook indicated that he did not “think more than one-tenth of one percent of [all] lobbyists were ever registered, even when the fee was practically nothing.”Footnote 40 As of 1947, there had been no convictions under the state’s lobby law.Footnote 41

Figure 3. Lobbyists, Clients, and Fee in Georgia, 1912–1970.

In 1967, Representative James Westlake began drafting new legislation when he spotted a lobbyist using the desk of an absent legislator. At first, lobbyists opposed his measure, but Westlake met with them and “pointed out that [his] bill would stop ‘shadow operators’ from getting started.”Footnote 42 The measure was eventually approved and ultimately signed by the governor on March 24, 1970, as Public Act 1294. As with the old law, lobbyists were still required to register with the secretary of state. The prior tax on registered lobbyists was repealed. A new fee of $5 was imposed, and lobbyists were obligated to wear name tags while in the Capitol (signaling that they were registered). Violations of the law were punishable as misdemeanors. The secretary of state was delegated with reporting violations to members of the Rules Committees. The new law took effect on July 1, 1970. Figure 4 shows the gradual increase in registration totals among lobbyists and clients after 1970. Unlike during prior years, hundreds of lobbyists and employers registered every year. These statistics were generated from lists of registered lobbyists published by the secretary of state and other agencies.

Figure 4. Lobbyists, Clients, and Fee in Georgia, 1970–2016.

The legislature continued to tinker with its lobby law, sometimes inviting lawsuits. Throughout 1991 and 1992, Secretary of State Max Cleland and prominent Atlanta newspapers campaigned for an improved law.Footnote 43 Among other changes, the Public Officials Conduct and Lobbyist Disclosure Act of 1992 transferred lobbyist delegation to a newly created State Ethics Commission. Lobbyists were also required to file expense reports for each month of the legislative session. The Commission was granted responsibility for enforcing the act, including using subpoenas, fines, and rule making. As part of an ethics reform measure, lobbyists were required to pay a fee of $200 to register. Nonprofit organizations were charged $25. In January 1994, the Georgia State AFL-CIO and affiliated labor organizations filed a complaint in a federal court seeking a permanent injunction against the collection of the fee. Because the AFL-CIO did not qualify as a nonprofit organization, it objected to paying to register multiple lobbyists. The organization challenged the fee on the grounds that it violated the First Amendment clause protecting freedom of petition, the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and provisions of the National Labor Relations Act. In September 1995, Judge Marvin Shoob agreed with the union and struck down the collection of the fee. In 2010, Governor Sonny Perdue signed into law Senate Bill 17, which revised the jurisdiction of the State Ethics Commission. The Commission was renamed the Georgia Government Transparency and Campaign Finance Commission, and it was allowed to issue larger penalties (up to $10,000) for violations. Importantly, a new registration fee of $300 was levied on lobbyists, who also had to report their expenses twice per month. This law was further amended in 2013 by House Bill 142. The initial registration fee was lowered to a $20 badge fee, and lobbyist gifts were limited in value to $75. Figure four illustrates numbers of lobbyists and clients over time, and the evolution of the fee.

Michigan

Until early 1946, Kim Sigler served as a special prosecutor in a grand jury investigation of legislative corruption. With the acquittal of a businessman accused of bribery, Sigler’s activities as special prosecutor were investigated by the state Senate and he was subsequently fired by a circuit court judge. Sigler ran for governor as an outsider seeking vindication. He was dubbed the “maddest man in America” by a national magazine and campaigned on a promise to “clean up” state government.Footnote 44 Upon winning office, Sigler brought an air of good-government-reform mindedness. In his inaugural address, he demanded that the legislature enact a law controlling “unethical” lobbyist activities. Michigan had no lobbyist statute at the time.

Ultimately, the legislature approved a “Legislative Agents Act,” which the governor signed into law as Public Act 214 on June 17, 1947. The act required lobbyists in Michigan to register with the secretary of state. Like the early laws in New York and Georgia, the Michigan act required lobbyists to register. Unlike those other laws, however, Michigan lobbyists were not required to file expense reports. Throughout the 1950s, multiple amendments were proposed, including one that would require lobbyists to report expenses. All the amendments failed except one (Public Act 157, approved on April 18, 1958) that required lobbyists to register every year instead of every two years.Footnote 45 The only limitation or prohibition in the act was a ban on contingency-fee arrangements.

By the 1960s, the inadequate nature of the lobby act was becoming more apparent. The secretary of state had no enforcement or investigatory powers. Despite eyewitness accounts claiming that lobbyists were spending thousands of dollars on gifts, meals, and lodging for legislators during the 1959 legislative budget impasse and 1962 tax reform debate, Attorneys General Paul Adams and Frank Kelley noted that nothing within the statute prevented such abuses from occurring. Walter de Vries noted that numerous interests typically did not register, and that no lobbyist had ever been prosecuted under the law.Footnote 46 Additional unsuccessful attempts were made throughout the 1960s to amend the law. These attempts included requiring lobbyists to report expenses and pay a higher registration fee. Even though the legislature passed a wide-ranging campaign finance reform in 1975 that included some provisions affecting lobbyists, the state’s Supreme Court ruled the bill unconstitutional as having pertained to too many issues at once.Footnote 47 A new lobby reform bill emerged out of the legislature’s attempt to mend the prior lobby law.

At the urging of the Michigan Citizens Lobby and Common Cause, Senator Gary Corbin introduced Senate Bill 674 on June 6, 1977.Footnote 48 After passing through the legislature, the bill was signed by Governor William Milliken as Public Act 472 on October 19, 1978. Among other provisions, the act included more specific registration criteria for lobbyists and numerous bans on gifts. The law also required lobbyists to report the details of their expenses after every legislative session. The act empowered the secretary of state to forward suspected violations to the attorney general’s office for prosecution.

Public Act 472 was not implemented immediately due to litigation. Implementation could not occur until the secretary of state drafted rules for implementation and a joint legislative committee approved of the rules.Footnote 49 An initial draft was not approved by the committee and numerous lawsuits delayed implementation.Footnote 50 Even though a joint committee eventually approved of a new set of rules in November 1980, the Michigan Chamber of Commerce spearheaded a fund-raiser for litigation. A coalition of more than 100 interest groups filed a lawsuit to stop the act from going into effect.Footnote 51 The coalition branded itself the Committee to Protect the First Amendment Right to Lobby. The lobby law was deemed an infringement on free speech by Ingham County Circuit Judge Robert Bell in October 1981. In the absence of a new law, the old statute from 1947 was back in effect. Doug Ross, the founder of the Michigan Citizens Lobby, had been elected to the state Senate and began to introduce new lobby legislation.Footnote 52 Within a year of Bell’s decision, however, the Michigan Court of Appeals had reversed the ruling (in Pletz v. Secretary of State), and in September 1983 the Michigan Supreme Court refused to hear a second appeal. Although the reporting requirements of the lobby law had been weakened by rulings, most aspects of the law remained intact. The law went into effect on January 1, 1984, despite jeers and snickers from lobbyists.Footnote 53 Figure 5 shows totals of lobbyist and employer registrations in Michigan from 1951 until 2016. There was a marked increase in their numbers after 1975 when lobbyists were aware that regulatory changes were being drafted.

Figure 5. Lobbyists and Clients in Michigan, 1951–2016.

Despite the courts’ rulings, the Michigan legislature did not provide resources for the secretary of state to implement the law fully. Registration totals increased dramatically, but according to Secretary Richard Austin, there was “no money … to interpret the law and receive reports.” The first expense reports were to be collected by August 31, 1984, from more than 2,700 registered lobbyists and employers. The president of Michigan’s Common Cause chapter suspected that lobbyists had persuaded legislators not to allocate additional funds for enforcement, but lawmakers denied this.Footnote 54 Despite the initial lack of enforcement funding, there is evidence that the reporting requirements of the law caused lawmakers to accept fewer and cheaper meals and gifts from lobbyists.Footnote 55

Since the law’s implementation, the Michigan legislature has modified its lobby regulations slightly including by making changes to reporting requirements (including Public Acts 83 of 1986 and 412 of 1994), implementing prohibitions on legislators accepting “honoraria” for speeches or other public appearances (Public Act 385 of 1994), and implementing a short cooling-off period for former legislators looking to lobby (Public Act 383 of 1994). Figure 5 shows the great increase in registration totals that occurred between 1983 and 1994. These statistics were calculated using registration records or statistics published by the secretary of state. Michigan’s improved lobbyist act compelled more lobbyists to register.

Implications

The three histories of lobby reform in the American states present evidence for a generalizable narrative of incremental policy change on matters of governance. The narrative draws attention to a distinction between two kinds of lobby regulations. Lawmakers and lobbyists have less to fear from the imposition of transparency laws than the imposition of limitations or prohibitions on lobbyist conduct. Transparency laws threaten less to undermine symbiotic relationships between lawmakers and lobbyists than limitations or prohibitions on gifts or campaign donations. Consequently, lawmakers in the three states turned generally to transparency before limiting or banning outright lobbyist actions. Unpredictable agenda-setting events, including both within the states and nationally (e.g., Watergate), helped to spur pushes for lobby regulation. Once the salience of these events passed, however, lawmakers and lobbyists had incentives to undermine or skirt lobby regulations.

Others may test these claims in a more systematic manner. If legislators and lobbyists truly resent limitations and prohibitions on lobbyist conduct more than transparency laws, then similar processes of lobby reform may be seen in other political systems. In general, the narrative of incremental policy change would imply that legislatures adopt disclosure laws before truly regulating the activities of lobbyists (e.g., giving gifts and contributions). Simple bans on quid pro quo arrangements, which predate transparency laws for the most part, are not sufficient regulations of lobbyists who develop relationships with lawmakers over time. Testing these claims in a more systematic manner requires collecting data on historical lobby regulation from additional (preferably many) political systems with elected legislatures. Existing studies of policy innovation or diffusion certainly examine policies across many systems, but they neglect to examine how lawmakers’ self-interest may complicate patterns of policy change specifically for governance issues. These studies tend to cast lawmakers more positively as learners, experimenters, neighbors, or (less positively) imitators. Indeed, existing studies of historical adoption of various lobby laws in all the states suggest that registration preceded by many years the adoption of revolving-door laws.Footnote 56

If legislators and lobbyists elsewhere are found to prefer transparency over direct limitation on a consistent basis, then what might be implications for the adoption of other kinds of governance policies? Recall that these policies often counter the interests of political elites such that applying usual narratives of policy innovation or diffusion may be complicated. Agenda-setting events or policy entrepreneurs likely are required for shifting public opinion toward reform, but political elites will stymie reform where possible. Even with more events or entrepreneurs, subsequent policy change may be more difficult on governance issues with seemingly dichotomous outcomes, such as direct democracy or term limitations. Lobby reform lacks this dichotomy because lobbyists may be regulated in multiple ways and members of the public likely comprehend that lobby laws may be strengthened further.

Scholars might verify further whether governance policies truly enjoy a unique immunity from repeal compared with other kinds of policies. The lobby laws in New York, Georgia, and Michigan were circumvented in part by extralegal means: the text of the laws stood unchanged for multiple decades in every state, but legislators were able to undermine these laws by not delegating enforcement clearly or supporting enforcement efforts financially or purposefully imposing taxes on lobbyists who complied with registration requirements. These cases suggest that lobby reform, as a governance issue, enjoyed immunity from formal repeal and that legislators had to find extralegal means to repeal these laws. After all, legislators had the formal abilities to repeal the laws entirely. Attempts to repeal other governance policies such as campaign finance restrictions, direct democracy, legislative term limitations, and tax and expenditure limits may provoke popular backlashes. That may also be the case for lobby regulations.