After I die, immediately shave my head and wash my body, dress me in an old long hempen gown and a pair of old hempen trousers, top that with an ancestral robe of tea-colored cloth covering both shoulders, then place me into the casket. Use a casket made from very thin fir and there is no need to expend any craft as it is only to cover my form temporarily. After putting my body into the casket, do not keep the casket in the temple, do not set up the altar for worship or invite eminent monks to light the funeral pyre. My attendants shall raise [the image of] Vairocana Buddha and cry ten times, then light the fire. Collect the bones the next morning—don’t bother with holding them in an urn—and scatter them over deep and clear water anywhere. Do not set up an altar for the seven-day mourning, and attendants may leave as they wish at this point. Those who go to Lingnan will carry my will and call upon the venerable Monk Jingcheng; those heading to the Danxia and Haichuang monasteries should report this news.

吾去世後, 即剃髮澡身, 外衣舊葛布長衫, 內衣舊葛布褲, 披茶褐布通肩祖衣, 便入龕。龕取舊杉木板極薄者, 不用費工, 足以蔽形一時而已。入龕訖, 不停龕, 不設供, 不請尊宿舉火。侍者舉毘廬遮那如來嚎十聲, 即下火。次早撿骨, 不用壇盛, 隨所在水清深處, 散投其中。不設靈位, 不守七, 侍者即日各隨緣好去。其入嶺南者, 持吾遺命, 謁淨成老和尚及丹霞、海幢諸剎, 即此報聞矣。Footnote 1

Shortly before his death, Dangui 澹歸, shorthand for Jinshi Dangui 今釋澹歸 (aka Jin Bao 金堡, 1614–80; see Figure 1) left these instructions for his funeral and burial. He then distributed belongings among the attendants. Having traveled constantly in southern China during his earlier years and having been a monk for three decades, he was now seriously ill during his stay in Jiaxing, Zhejiang, on a journey to collect the Tripiṭaka, the Buddhist canon. While ready for his extinction, he was keenly aware that the disciples would endeavor to enshrine his remains at Danxia 丹霞 Monastery, Guangdong, where he had served as abbot for more than a decade. To warn them against doing so, Dangui concluded his final instructions:

You shall not keep my smelly skin bag just to escort it back to the [Danxia] Mountain and pick a site for the stupa internment, incurring troubles for our dharma protectors. “Wherever one dies, there one should be cremated and his bones dispersed into the waters nearby.” I have already said these words since the time I left Lingnan—not just from today. Whoever violates these words, his bad deeds equal those of a malefactor.

Figure 1. Portrait of Jinshi Dangui 今釋澹歸 (1614–80), Qing dynasty. Courtesy of Master Guangxiu 光秀, Haichuang Monastery, Guangzhou.

汝等不得留吾臭皮囊, 作扶龕回山, 擇地建塔之局, 累諸護法。“隨處死, 隨處燒, 隨處散骨水中。”吾出嶺時, 便有此語, 非今日始作此語也。若違此語, 惡同凶逆。Footnote 2

The disciples cremated Master Dangui’s body as instructed, but they did not scatter the ashes and bones over water. Indeed, they collected the beloved monk’s cremated remains in an urn, which they would later transport back to Danxia Mountain in Shaozhou (present day Shaoguan), Guangdong. There, they chose a scenic site for the enshrinement of Dangui’s relics in a stupa, as they did for other abbots and eminent monks.Footnote 3

Monk Dangui’s remains would rest in the red-colored sandstone of Danxia for nearly a century before they entered the political limelight. The circumstances of this incident are shadowy. What we know for sure is that, in 1775, amidst tightening censorship measures throughout the Qing empire, a military commissioner (rank 4a to 5a)Footnote 4 of the Shaozhou region stumbled onto one curious case. On an official visit to Danxia Monastery, the commissioner surnamed Li took notice of a cabinet that was locked up and heavily sealed. He inquired of the monks, and they claimed no knowledge of its contents except that every abbot had affixed a new seal on it since the Kangxi reign (1661–1722). Growing more suspicious, the commissioner ordered the opening of the cabinet and found a book defaming the Manchu dynasty by the monk Jinshi Dangui. Sensing that this discovery would tap well into the rising tide of government censorship, Li’s son urged him to report the case, anticipating the prospect of getting on the fast track for a promotion. Commissioner Li had been promoted from Hainan several years back; deliberating the matter, he reported it to the highest-ranking regional official, the Governor-general of Guangdong and Guangxi (rank 2a).Footnote 5

The Case

This case quickly snowballed into a full-blown posthumous prosecution. By the end of 1775, the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736–96) issued a massive posthumous fulmination against the monk Dangui. Empire-wide bans were imposed on his surviving works, concurrent with the compilation and collection of the Siku quanshu 四庫全書 (Complete library of four treasuries). The two aforementioned officials, the Governor-general of Guangdong and Guangxi, Li Shiyao 李侍堯 (d. 1788), and the military commissioner of Shaozhou, Li Huang 李璜 (d. 1777), were assigned to search for the traces of the monk in Danxia Monastery and nearby monastic communities.Footnote 6 They displaced the clergy from the monk’s lineage in several monasteries, staffing them with those directly appointed by the government; they destroyed all the monk’s books and writing, together with his remaining calligraphy, paintings, and inscriptions.Footnote 7 They allegedly also burned down the monastery and ground the monk’s ashes and bones after disinterring them from the stupa.Footnote 8

As the inquisition of Dangui unfolded, the trials sprawled from Beijing and Tianjin to Guangdong and Jiangnan, implicating wider connections far beyond the monastic community. In the process of seizing the anthology of Dangui’s writings, Qianlong learned that a former prefect of Shaozhou, a Han bannerman, had helped publish a recent edition. Deeming this an act of treason, the infuriated emperor could nonetheless not have the bannerman tried as he was already deceased at the time. Consequently, in his stead, his surviving children, grandchildren, and in-laws were investigated and would see their wealth confiscated before the trials ended.

Why did a deceased monk become the subject of a high-profile censorship case? Indeed, the High Qing literary inquisitions involved some cases of posthumous prosecution.Footnote 9 This political storm of the Dangui censorship centered around his remains—not only his works but the ashes and bones that his friends and disciples had determined to preserve against his will. Who would have foreseen the 1775 trials in the monk’s name, followed by the mobilization of multilevel investigative resources conglomerated around those who were tangentially connected to his legacy? What’s more, near the conclusion of the trial, the Qianlong emperor issued a series of edicts calling out the monk, fulminating against him as a despicable coward in imperially commissioned historical projects. Why did the emperor bother to inflict damage on a long-dead monk, a seemingly obscure historic figure on a faraway mountain? The messy outcome of this case certainly seems disproportionate to the purported crime.

Yet, it is untenable to reduce the censorship to an instance of Manchu–Chinese conflicts or to attribute it to Qianlong’s wrath or personality flaws. Consider how the case advanced—the reports, arrests, investigations, and trials—the bureaucracies involved comprised of officials from different regional and local offices to central government, Manchu and Chinese alike. Qianlong’s decision-making might have affected their actions but could not have dictated their motivations. What inspired the discovery of this case and impelled its progression deserves attention.

This study proposes to make sense of the case against Monk Dangui by exploring its political implications. Cross-examining sources including imperial archives and records, official and mountain gazetteers, anthologies, private histories, and jottings,Footnote 10 the following section first reconstructs the case within the context of the 1770s to explore Qianlong’s attendant concerns. The second section, by delineating the life and social networks of Jinshi Dangui, addresses the functions of religious organizations during the Ming–Qing transition. Specifically, the gentrified Buddhist monastery communities, as we will see by following those in Guangdong, had fostered interregional networks that were highly socially engaged, potentially even lending themselves to political activism—a force that would become problematic for the consolidated Qing state. This study rethinks the history and historiography of the early Qing period and contributes to two larger interdisciplinary themes. First, it reconstructs scenes of the Dangui trials from archives and other sources to show what the trials were like and what they achieved and to delineate the power dynamics between the Manchu monarch, his officials at the central and local levels, and those who were involuntarily involved. Second, through the life and network of Jin Bao/Monk Dangui it explores the phenomenon of taochan 逃禪 (escape into Chan Buddhism), often used to describe a common sociocultural experience of those displaced literati who lived through the Ming–Qing transition.Footnote 11 Uncovered here, the twists and turns of their stories challenge oversimplified narratives that seek to equate early Qing literati monasticism with Ming loyalism and offer useful insights into the obscure moments of the Qing formation.

The Censorship

The unfolding of the Dangui case exemplifies the changing dynamics between the imperial court and local offices. While early Qing censorship cases frequently started with local reports driven by petty quarrels or personal preservation needs, the court dealt with these cases when they had already emerged and was less interested in soliciting cases for prosecution.Footnote 12 That changed after the 1760s; since the Qing empire was at the zenith of its military might, the Qianlong emperor was concerned with holding his realm together. As the disturbances had become too frequent to trust that they would calm down by themselves, he demanded provincial officials to report and deal with minor revolt cases in the countryside.Footnote 13 He also took a more proactive role in the cultural realm, attempting to exert soft power over all the ethnic groups he ruled.Footnote 14 To his Chinese audience, he invented for himself the persona of a renaissance man immersed in all branches of Chinese culture. The compilation of the Siku quanshu epitomizes this enterprise. It was conceivably also motivated by the desire to control all the texts that might be considered seditious or threatening to the Manchu rule. In the process of collecting the books and manuscripts for the project starting from 1773, Qianlong ordered the local offices to turn in any questionable literature or unauthorized historical accounts. This larger context facilitated the disclosure of the hidden book by Dangui.

Li Huang, the military commissioner who reported the case, was not a prominent figure in subsequent investigations according to official archives. Sources in local records and gazetteers indicate that his family did achieve some good fortune afterward. A native of Xiushui, northern Zhejiang, Li Huang resided in the neighboring county of Wujiang, Jiangsu, with his and his younger brother’s families. When he was promoted to Shaozhou in 1769, his son Li Dahan 李大翰 and brother Li Zhang 李璋 accompanied him, assisting with advising and accounting matters. After the case, in 1777, the commissioner was summoned to Beijing for an audience with the emperor; he died in the same year, during his stay in the capital. His brother, Li Zhang, had been a devoted Buddhist and later became a major patron of the local Guanyin temple. He received an imperial title in 1785 thanks to the honor of his nephew, Dahan, but continued undertaking hard physical labor and seemed to have enjoyed his last days.Footnote 15 As to Dahan, who allegedly urged his father to report the case, he embarked on a brilliant if short-lived career. He obtained the jiansheng status to study in the Imperial School in 1775, graduating with an appointment to the Ministry of Punishment and subsequently positions first in the newly incorporated city of Urumqi and then in the provinces of Henan and Hubei. He garnered imperial honors for his extended family.Footnote 16 Yet he died from a mysterious, acute illness while serving as the prefect of Hanyang in Hubei. Anecdotes from home have it that he saw a monk in a vermilion-colored robe before falling sick. There must have been some form of cosmic retribution, the rumor insinuates, because not only Dahan’s ambitions were cut short, but all the bright sons of the Li family ended up dying young after this incident, seeing the same monk in vermilion at their deathbeds.Footnote 17

Who could the monk be alluding to? Presumably—though it need not be—the persecuted monk Dangui, as he was known to be a loyalist to the Ming dynasty, whose ruling house had the surname Zhu 朱, which means vermilion. Authentic or not, this record illustrates an undercurrent to the power dynamics among Chinese scholars amid High Qing literary inquisitions, in which some ambitious local officials eagerly proved their worth to the imperial court by trading hidden information, while others observed in silence and documented the political theater. After all, Li Huang and his son were but two of the forgotten tens of thousands who had facilitated High Qing censorship.

When Li Huang’s report moved up to the office of Li Shiyao, he was serving his second tenure as the governor-general of Guangdong and Guangxi and was one of the highest-ranking officials within the empire.Footnote 18 A member of the Hanjun Bordered Yellow Banner, he came from a well-established family descended from Li Yongfang 李永芳 (d. 1634), the first Chinese general to have surrendered to the Manchus in 1618.Footnote 19 Over his long and distinguished career, Li Shiyao was one of the emperor’s most trusted officials. In the spring of 1774, he was first appointed as a grand councilor and held concurrently the position of the Minister of War; in the subsequent capital evaluations, he ranked among the best, together with three other top-tier officials. Regardless of these glories and honors, a seasoned high-ranking official like him would know well that his performance was always assessed, evident in the hundreds of memorials he sent to the palace year after year.Footnote 20 In return for his diligence, the emperor nurtured a warm personal relationship with him. In that year, the governor-general was excused for matters such as occasional illness, his attendants’ unlawful activities, and even the withdrawal of his daughter from a list of girls to be sent into the palace.Footnote 21

But the emperor’s patience certainly had its limits, especially in the second half of that year. While in the summer palace, Qianlong was informed of the circulation of classified palace memorials with his vermillion ink comments in the provinces. Investigations showed that the eunuch Gao Yuncong 高雲從 (d. 1774) had been utilizing his access to the inner court to disclose classified documents in return for favors from officials. Through these exchanges, he was able to place his brothers in provincial offices, including one in Linqing, Shandong, and another in the Canton Customs Office.Footnote 22 Unsettled by this discovery, the emperor reprimanded and punished several court officials, including the grand councilor Yu Minzhong 于敏中 (1714–79).Footnote 23 Couriers were dispatched immediately to Guangdong, ordering Li Shiyao to assist in the removal and arrest of the imperial commissioner of the Canton Customs Office; Li was entrusted as its interim commissioner.Footnote 24 Another decree was sent to the governor of Shandong, ordering the follow-up investigations in Linqing.Footnote 25 In Shandong, two involved officials were stripped of official titles; one was kept in service and had his honor restored only after subsequent contributions in managing the Wang Lun 王倫 (d. 1774) uprising and in a major repair work on the Yellow River dikes in Henan that year.Footnote 26

It was a busy year for the Qing government and its officials. Provincial officials constantly faced the pressure to perform or outperform their colleagues, as they were measured by their efficiencies for reward and punishment. Xu Ji 徐績 (d. 1811), the governor of Shandong, probably felt this most profoundly. Before the conclusion of the Gao Yuncong case, Wan Lun rebelled in eastern Shandong and took over part of Linqing. Though the revolt was quickly quelled, Governor Xu was blamed for being unable to contain the revolt from the beginning, for which he bore both symbolic and financial damages. Though his career did not suffer for long, that prospect only became apparent after he proved his capacities in the ensuing Yellow River repair works and later as the governor of Henan.Footnote 27

Aware of these circumstances, Li Shiyao duly complied with the imperial order to search and collect rare and remnant books. In November 1774, two county magistrates recovered the books by the poet Qu Dajun 屈大均 (1630–96), whose books had been suggested for censorship during the Yongzheng reign (1722-35).Footnote 28 Li Shiyao detailed the follow-up, affixing notes on the confiscated books he sent to the palace.Footnote 29 The emperor therefore revisited the Lu Liuliang case, which resurfaced in another report, in the subsequent months and reviewed the histories of the Ming–Qing transition. With the compilation of the early Qing history project ongoing, he also set the organizing principles for the historiographical project Mingji gangmu 明紀綱目 (Outline and details of the chronicle of Ming), instructing the editors to review the official Mingshi 明史 and the histories of previous foreign dynasties of the Liao, Jin, and Yuan.Footnote 30

In November 1775, as the collection of books was ongoing, Qianlong castigated a governor for failing to send confiscated books to the capital but instead returning them to the bookshops from which these books had been collected.Footnote 31 When the emperor continued to review provincial reports about collected books, he noticed Monk Dangui’s book, Bianxing tang ji 徧行堂集 (Collection from the hall of going everywhere).Footnote 32 Dangui’s offensive language doubtless outraged the emperor, but more so were the ramifications of his legacy. The monk was viewed as the founder of the Danxia Monastery, and a former prefect of Shaozhou, Gao Gang 高綱 (fl. 1730s), had helped publish one edition of his Bianxing tang ji. A native of Gaomi, Shandong, Gao Gang was a Chinese Bordered Yellow Banner member. His pedigree is traced back to his father Qipei 其佩, a famous painter and official, and his grandfather Tianjue 天爵, who died and was imperially honored as a martyr during the Revolt of the Three Feudatories.Footnote 33 The lustrous lineage of Gao Gang indeed includes several high ministers during the Yongzheng and early Qianlong reigns. Yet Gao Gang, after being appointed prefect of Shaozhou in 1737, sponsored and wrote a preface to help raise funds for the publication of Dangui’s anthology. How could Gao Gang repay the grace this dynasty had bestowed on his family by hiding—even enabling—a treasonous book like this, the emperor remarked. Gao Gang would have deserved severe punishment had he been alive; but since he was dead, only his sons should be investigated for their involvement.Footnote 34

In Beijing, the grand councilor Fulong’an (1746–1784) thoroughly searched the Gao family compound, where Gao Gang’s second son, Gao Bing 高秉, was the occupant. The initial search did not yield the banned book. During the interrogation, Gao Bing claimed that his father only helped publish the new edition of the book under request from the monks of Danxia Monastery. Still, he denied possession of either copies of the book or its woodblocks. A continual search of the compound made a breakthrough by the discovery of two other banned materials: the first was the scholar-poet and Buddhist patron Qian Qianyi’s 錢謙益 (1582–1664) Chuxue ji 初學集 (Collection of preliminary learning) and the second was Monk Hanke’s 函可 (1612–60) poetry.Footnote 35 All the books and manuscripts were examined for potential unlawful writings to decide if this implied a deeper involvement. The investigations then extended to two other households in Beijing, arresting four Gaos, including a brother of Gao Bing, Gao Shuang 高![]() .Footnote 36 Gao Bing’s three other brothers reportedly resided in Tianjin, so Fulong’an dispatched couriers for Tianjin, summoning the prefect to make immediate arrests.Footnote 37

.Footnote 36 Gao Bing’s three other brothers reportedly resided in Tianjin, so Fulong’an dispatched couriers for Tianjin, summoning the prefect to make immediate arrests.Footnote 37

The emperor read the report and instructed on the next steps. He mandated the four top officials in Guangdong and Jiangsu on December 10 that all copies and woodblocks of Bianxing tang ji be seized and destroyed, together with other writing, calligraphy, or inscriptions by Dangui. This task was primarily assigned to Li Shiyao in Guangdong. Still, the Jiangsu officials were also asked to inspect publishers in Jiangning and Suzhou to make sure that the censored books and their woodblocks would not continue to exist. Gao Bing was punished for harboring banned materials.Footnote 38

In Jiangsu, officials confiscated different editions of Bianxing tang ji and other seditious books and woodblocks. In addition, they arrested two members of the Gao family in Suzhou. First was the oldest brother, Gao Hua 高䅿, who had left Tianjin earlier. He would be sent to the military tribunal in Jiangsu. The second was the wife of the earlier arrested Gao Shuang, who was sent to the Banner garrison.Footnote 39

At the time of arrest, Madame Gao, née Zhai 翟, lived in one compartment of the Zhai family compound with her children, mother, and maids. Her three brothers, all licentiates, and their families lived in other parts of the compound. Madame Gao had previously accompanied her husband to Zhaoqing, Guangdong, but the couple left Lingnan one year earlier when he was assigned a duty to return to Beijing. She fell sick halfway and later set out for her family in Jiangsu to recover. Some pawn receipts and a money order were discovered in the search. It turned out that Madame Gao had to pawn her valuables to get by after her return, as her three brothers had no means to support her. Furthermore, her husband, Gao Shuang, had recently asked her to borrow money to purchase an office. Madame Gao could only get some money from her younger sister in private.Footnote 40 Also found were a range of books from the Four Books, classics, dramas, to ledgers and geomancy books. When questioned about the banned book, all claimed they had no idea about it, much less a copy to hide.Footnote 41

In Tianjin, the search supervised by Yu Minzhong yielded fruitful results. The confiscated items include calligraphy from Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong, and a large collection of books. The book Bianxing tang ji, in forty-four volumes, and Monk Dangui’s calligraphy, turned up in the search. Two other books, a collection of Ming dynasty poetry and a prefectural gazetteer of Shaozhou, also contained the monk’s deeds and writings which were recommended for removal.Footnote 42

By the end of 1775, the last interrogation was concluded. Gao Hua, the oldest son of Gao Gang, had previously been staffed in a country office of Guizhou and then a tutor in Beijing. He lost his job in the spring of 1775 and traveled from Tianjin to Suzhou to seek job opportunities through a cousin but was stranded there due to a series of misfortunes. Claiming no knowledge of the edition of Bianxing tang ji, he only recalled another anthology his father had helped publish, which, if extant, would be in Tianjin with his brothers.Footnote 43 And so closed the trials of the Gao—after all their possessions and connections were inspected and scrutinized. Despite the family’s former standing, most of the Gaos at the time were serving as local staff, managing just to make ends meet through family connections. Their prospect after these trials was even grimmer. Pronounced as accomplices of treason by the emperor, several of them were stripped of their hereditary privileges and sentenced to banishment, only to be granted amnesty by the next emperor.Footnote 44

As the trials unfolded, the emperor learned more about Monk Dangui, his work, and his lingering influence. After the search in Guangdong, Li Shiyao reported that some books and calligraphy bearing the name Jin Bao—Dangui’s lay name—were still circulating in local monasteries and bookstores. Li remarked on Dangui’s connections with powerful early Qing figures, including the feudal princes Shang Kexi 尚可喜 (1604–76) and Geng Jimao 耿繼茂 (1651–71), as well as the scholar-official Xu Qianxue 徐乾學 (1631–94; jinshi 1670). Clearly Monk Dangui had been busy building regional networks rather than living quietly in seclusion. Li Shiyao thus suggested that the reciprocal writings, inscriptions, and the stupa containing the monk’s remains should all be eliminated, so that people would not continue to be under the influence of the monk’s sham reputation. On this proposal, Qianlong commented with a brief approval, “I’m aware of it.”Footnote 45

The emperor learned by now that Dangui’s dharma name, Jinshi, appeared frequently in the Buddhist scriptures compiled during the early Qing. Moreover, some of these scriptures had already been included in the Qianlong Tripitaka—and issued by none other than the Imperial Household, with more than one hundred copies subsequently distributed as gifts to prestigious monasteries empire-wide. To remedy this, the Grand Council concluded that only Jinshi’s name and his writings needed to be removed, but the scriptures could continue to exist. As to the fact that censored contents were found within publications printed by the imperial court, the Wuyingdian printing workshop should be notified to destroy such contents in the Qianlong Tripitaka and their woodblocks.Footnote 46

The Dangui case had more political implications. Halfway into the case, Qianlong must have realized the futility of censorship and proscriptions. More importantly, some Ming loyalist networks were probably entrenched within the early Qing Buddhist community. Jin Bao and his many names are visible in various early Qing sources ranging from poetry anthologies to mountain gazetteers. In several poetry collections valorizing Ming loyalists, he was occasionally referred to by his style name Daoyin 道隱 (the Way [is] hidden) and associated with Qian Qianyi and Qu Dajun, two other poets targeted for censorship previously. The connections between the three were indisputable: all had close ties with a Guangzhou Buddhist community that was involved in compiling the anthology of the eminent monk Hanshan Deqing 憨山德清 (1546–1623).

During this period, Qianlong instructed court historians to rewrite the history of the Ming–Qing transition and to recognize the Southern Ming remnant courts, viewing them as the Qing rule’s legitimate contenders during its consolidation.Footnote 47 The emperor noted that those who died for the sake of these rules ought to be honored as martyrs for their demonstrated virtue of loyalty. At the same time, Jin Bao, known as one of the “Five Tigers” of the Yongli court, out to be made clear as a representation of the political dysfunction of the Southern Ming.Footnote 48 He ordered to officially honor the Ming loyalist martyrs, including those who died during the fall of Beijing and after the demises of the Southern Ming courts. His decree ends with a fulmination against Qian Qianyi, Jin Bao, and Qu Dajun, who are called out as shameless cowards who could not die for their cause, had no real understanding of Buddhism, but gratuitously used writings to excuse themselves.Footnote 49 To ensure that his judgment was final, the emperor’s edict would be set as preface to a series of imperial projects, including the newly commenced Shengchao xunjie zhuchen lu 勝朝殉節諸臣錄 (Records of the officials who died out of loyalty to the fallen [Ming] dynasty). The ideological antithesis of those martyrs, those Ming officials who surrendered to the Qing during the course of its political consolidation, should be written into the Erchen zhuan 貳臣傳 (Biographies of twice-serving ministers).Footnote 50

By so doing, Qianlong asserted the position of a universal ruler and judge to grant recognition to the Chinese martyrs of the Ming–Qing transition while condemning those who chose to survive it. This dichotomy was meant to be a historical lesson for posterity. The Manchu ruler coopted the practice of praise and blame in Chinese historiography championed by the Song Confucians, an endeavor he could only have achieved after the early Manchu rule’s appropriation of Cheng-Zhu Confucian loyalism.Footnote 51 The vision of absolute loyalty represented in these historiographical projects—Qianlong’s governing concerns in the 1770s—has concealed the reality of the early Qing conquest, during which political allegiances were constantly in flux, but social affinities often remained more durable. A close look at Dangui’s life trajectory and social networks will demonstrate this in the following.

The Life Lived: From Jin Bao to Jinshi Dangui

Who was the intended target of this censorship case—Abbot Dangui? Monk Jinshi? The Ming loyalist Jin Bao? Or the Chinese literatus Jin Daoyin who encoded his laments in his name during a cataclysm? The 1775 trials revealed to the Qianlong emperor indeed someone accustomed to weathering political storms and taking on new identities. Someone who had attested in his names the self-reinventions mirroring the upheavals of his time.

A native of Renhe, Hangzhou, Jin Bao had gone through a long journey before he settled on the Danxia Mountain as Abbot Dangui. Surprisingly little has been said about his early life, likely due to his own silence on this topic. Though his father had obtained examination degrees and served as a supervising censor (rank 7b) at one of the Ministries, the family had been impoverished by Jin Bao’s youth, so he had to borrow the travel cost for the examinations.Footnote 52 He passed the 1640 jinshi examination at twenty-seven sui and engaged in several publishing projects afterward (Figure 2).Footnote 53 Briefly appointed a magistrate in Linqing, Shandong, a long-established commercial center in northern China, he witnessed ordinary people being forced into exile or banditry to escape excessive taxation. He resigned and earned recommendations for new positions at court, but his plan to travel to Beijing was interrupted by war.Footnote 54 In late spring of 1644, the Ming capital fell to a popular uprising army led by Li Zicheng 李自成 (1606-44), and the last Ming emperor, Chongzhen 崇禎 (r. 1628-44) committed suicide in the Forbidden City after losing all hope. Within six weeks, the Manchu forces drove Li Zicheng’s army out of Beijing and established Qing rule in China.

Figure 2. Preface to Lu shi 路史 by Jin Bao 金堡 (left) page 1a and (right) page 4b. Late Ming reprint of the 1603 edition, ca. 1640. Courtesy of Mr. Jacky Li of the Fung Ping Shan Library, University of Hong Kong.

Thus, Jin Bao traveled back to his hometown, which was soon also engulfed in war. Having taken over Beijing in the summer, Qing forces went on to conquer Nanjing and Hangzhou within a year. Meanwhile, Jin Bao’s parents both passed away during this period. For the next four years, he traveled constantly in Zhejiang, Fujian, and Hunan to mourn for his parents, communicate with various anti-Qing forces, and escape from the Qing army and powerful political foes within the anti-Qing resistance.Footnote 55 He also started to become interested in Buddhist teaching and lifestyle.

In 1648, Jin Bao went to Zhaoqing, Guangdong, serving as supervising censor at the Yongli (r. 1646–61) court under the recommendation of Qu Shisi 瞿式耜 (1590–1651; jinshi 1616). It was a promising year for the Yongli forces: before the summer, the defected Qing general Li Chengdong 李成棟 (d. 1649) brought Guangdong under Yongli’s rule; in the fall, the pro-Ming maritime general Koxinga (aka Zheng Chenggong 鄭成功, 1624–1662) sent messengers from Namoa Island on the border of Fujian.Footnote 56 Jin Bao became very hopeful about the military prospect and submitted a series of memorials, urging Yongli to consolidate power by restricting the hereditary military elite at court.Footnote 57

Jin Bao’s distrust of the military elite epitomizes the alienation between the political and military cultures in seventeenth-century China. Though the early Ming state valorized the spirit of military prowess, by the early sixteenth century the status of the army elite had declined along with their colonies and garrisons. Civil officials became increasingly dominant in the Ministry of War and military affairs following the deterioration of the military establishment.Footnote 58 Jin Bao took the trajectory of the traditional cultural elite; he represented the group most invested in the civil service examinations and the prestige they conferred—the successful ones gained access to various resources associated with officialdom. Through the examination system, they formed long-term connections such as teacher–students, friendship, and marital alliances—relationships that continued to further their personal, career, and family developments. While the late Ming warfare against the Qing forces and the rebel armies underscored the moment of military commanders, the Ming court and its civil officials, however dependent on the military generals for frontier defense, were nevertheless not confident about their loyalty. This is shown most starkly in the execution of Liaodong military commander Yuan Chonghuan 袁崇煥 (1584–1630; jinshi in 1619)—who was ironically from a civilian background—under the accusation of treason. Indeed, during these treacherous times, the allegiance of those who held military power was not always reliable. One notable example is Wu Sangui 吳三桂 (1612–78), the Ming commander of Liaodong, who collaborated with the Manchu army in the 1644 takeover of Beijing and was rewarded with a fiefdom in Yunnan, helped eliminate the last Ming remnant rule by capturing the Yongli emperor in Burma, only to rebel later against the Qing rule in 1673.

Jin Bao advocated a supreme commander-ruler over both civil bureaucracy and military establishment. He had earlier urged the Longwu emperor (r.1645-47), and later Yongli, to personally command the army, imagining that the monarch-commander would inspire and unite disparate local forces.Footnote 59 His desirable alternative would be a supreme commander with shared ethical convictions and political allegiance, such as those civil officials taking on military commandership. In reality, the Yongli court consisted of various networks of regional groups and interregional military allegiances. Group affiliations and personal loyalties nurtured comradeship and factionalism within the court, whose very existence depended on the support of regional and transregional military powers. Jin Bao’s outspoken and unabashed distaste for strongman politics again stirred up divisions and provoked hostility from powerful court figures. Intensified factionalism inevitably diminished the foundation of the Yongli court and Jin Bao suffered political demise in 1650 when Yongli forsook Guangdong after a series of military defeats. Stripped of his official title, beaten at court, and tortured in prison, he was only exempted from capital punishment because of the plea of Qu Shisi and was sentenced to exile in Guizhou. The beatings and torture had rendered Jin Bao’s left leg crippled; when the warfare again interrupted the traffic en route, he took the tonsure and became a monk in Guilin.Footnote 60

Later in the year, the Qing army took over Guilin, capturing the two generals, Qu Shisi and Zhang Tongchang 張同敞 (1608-51); both were executed in early 1651 after refusing to surrender. Jin Bao, now tonsured and bearing the dharma name Xingyin 性因 (“antecedent nature as the cause”), sent a letter to the Qing commander, Kong Youde 孔有德 (d. 1651), requesting to collect the remains and writings of Qu and Zhang for a proper burial.Footnote 61 The monk Xingyin then traveled to Guangzhou, receiving ordination from the eminent Chan monk Tianran Hanshi, abbot of Haiyun Monastery, who gave him his new dharma name Jinshi, meaning “now a monk.” Two former colleagues from the Yongli court also joined as lay disciples.Footnote 62 To restrain the intense temperament of this newly ordained dharma heir, the Chan master made him wash dishes in the kitchen. Thus, the ordained Jinshi settled in Guangzhou and assumed another courtesy name, Dangui (“detached about returning”), which he and his friends frequently used.

When Dangui worked as a novice in the kitchen of Haiyun Monastery, it was said, he pawned his clothes to pay for the bowls he broke. At one point, a Qing official visited the monastery and recognized him in shock, as the monk had previously been the very chief examiner to have selected the official as a graduate. The official pleaded to offer the monk anything he could think of, but he only asked for some rice bowls, for the number of monks had increased so much that there was a shortage of utensils. The official indeed sent an order to Jingdezhen and had one thousand bowls made in the monk’s name as a gift to the monastery.Footnote 63 Because of their association with the monk, these bowls—known as the “Dangui bowls”—circulated in the black market throughout the Qing period and were still available in the Guangdong art market as late as the 1940s.Footnote 64

The displaced monk Jinshi Dangui found his sanctuary in the Lingnan Buddhist community. Interconnected monk–literati networks have existed as a cultural phenomenon in the development of Chan Buddhism since the Song period. The Chan master Tianran Hanshi’s career trajectory embodied such a trend. A native of Guangzhou, he had immersed himself in the classical tradition and passed the provincial examination before taking monastic vows.Footnote 65 This background allowed him to attract a large new following in post-conquest Guangzhou; his monastery became a sanctuary for literati who sought refuge amidst war and destruction.

As a dharma heir of the Chan master, the literatus-turned-monk Dangui undertook the role of a secretary to the master and managed his correspondences, becoming an inseparable presence in the local Buddhist community organized around him and in the trans-local networks he occupied as a center. Their friendship has manifested in their reciprocal poetry over the next decades. From 1652 to 1655, Dangui traveled to Fujian and Jiangsu under Hanshi’s instruction, taking the occasion to sojourn in Suzhou and reconnect with the local literati circle, with acquaintances from his earlier days and his new Lingnan network. On the return journey, he stayed in Mt. Lu to accompany Hanshi, who traveled there for a retirement plan.Footnote 66 When they returned to Lingnan in 1655, Hanshi led the Guangzhou Buddhist community to collaborate with the prominent Jiangsu scholar Qian Qianyi on a new anthology of the late Ming monk Hanshan Deqing.

Qian Qianyi had long asserted the role of a dharma protector in the Jiangnan region. In 1655, he entrusted his close friend Gong Dingzi 龔鼎孳 (1615–73, jinshi 1634), now taking a new office in Guangdong, to personally deliver a letter to Abbot Hanshi. It was a proposal of a project to compile the manuscripts Deqing left behind in Lingnan. This project excited Hanshi, who immediately connected with the monastic communities in Guangzhou and Zhaoqing to gather the manuscripts. His two dharma heirs, Monks Jinshi and Jinzhong 今種, formerly Jin Bao and Qu Dajun respectively, assisted in the communications.Footnote 67 Finally, after assembling the manuscripts, two other associates of Qian Qianyi, his kinsman Qian Chaoding 錢朝鼎 (jinshi 1647), then provincial educational commissioner of Guangdong, and Cao Rong 曹溶 (1613–85; jinshi 1637), Governor of Guangdong and Qian’s former colleague, funded the cost of transcribing the manuscript. In 1657, they took advantage of their official roles to enlist the provincial examination candidates in Guangzhou for the transcription of the text inside Guangxiao Monastery, temporarily used as the examination hall and at which Hanshi had been serving as abbot since the early 1650s. According to Qian Qianyi, while transcribing the manuscripts, one of the candidates was so inspired that he took the Buddhist vow and was ordained as a monk then and there.Footnote 68

The project, Hanshan laoren mengyou ji 憨山老人夢遊集 (The dream travels of the Venerable Hanshan) was accomplished in 1660 by the collaboration of literati–official networks and major Chan Buddhist communities from Jiangnan to Guangdong. The project’s operation owed as much to the transregional Buddhist networks as to the officials serving in the bureaucratic system under Qing rule. In the prefaces of the anthology, Qian Qianyi and Monk Jinshi Dangui meticulously documented those individuals involved in this communal endeavor.Footnote 69 Both frequently referred to the Buddhist network involved in this project years later in their correspondence. In a letter to Dangui, Qian Qianyi could not help but emphatically eulogize what he saw as loyalism embodied by the Lingnan Buddhists.Footnote 70 What he implicitly suggested leaves his reader clues, while circumstantial, as to the political undercurrents of the compilation of the Hanshan anthology.Footnote 71

A further look into the connections between Dangui and the Qing general Shang Kexi, a Chinese bannerman and the feudal lord of Guangdong, demonstrates how Dangui interacted with the early Qing bureaucracy to sustain his community. In 1650, Shang Kexi commanded the Qing troops to conquer Guangzhou. The bitter siege of the city lasted for ten months before the general released his army to carry out a massacre as retaliation. Following that, in a gesture to show repentance for his past deeds and to bring purification, Shang became a devoted patron of Buddhism. Dangui connected with the feudal lord through his aide, Jin Guang 金光 (1609–76), a native of Zhejiang. From the 1650s to the 1670s, Shang Kexi continuously funded the restoration and expansion of major Buddhist temples in the region, including Haichuang Monastery, where Tianran Hanshi and his dharma heirs served as abbots. The feudal prince also donated his salary to build within the old city of Guangzhou the Dafo Monastery, where Monk Tianran held a universal salvation ritual on his behalf in 1667. When the feudal prince retired in 1673, Monk Jinshi compiled for him a chronological biography.Footnote 72

Some literati hence condemned Dangui as morally decadent. Wang Fuzhi 王夫之 (1619–92), a former colleague at the Yongli court who had held him in high regard, was an example. Wang would later develop an anti-Manchu ethic and denounce Dangui as someone who completely forsook moral principles for Qing officials’ patronage.Footnote 73 Wang Fuzhi regarded Jin Guang, the aide of Shang Kexi, as a worthless scoundrel and Dangui’s friendship with him as evidence of the monk’s sycophancy and practical networking. Jin Guang was nevertheless a very different person from what Wang Fuzhi imagined him to be.

A native of Yiwu, Zhejiang, Jin Guang’s lineage traced back to the late Yuan recluse Jin Juan 金涓, through whom he was connected with Dangui.Footnote 74 During the mid-1620s, the young, poor, and wanderlust Jin Guang traveled to Juehua Island 覺華島, off Liaodong Bay’s coast, and met Shang Kexi, then a Ming general. The general was impressed by Jin’s broad learning, taking him as a retainer when Nurhaci, leader of the Later Jin, seized the island. After several failed attempts to escape, Jin Guang served as a trusted personal assistant to the general—who shifted his allegiance to the Manchus in 1634—for the next four decades. As the general’s aide, Jin Guang used his influence to protect many literati and their families. During the conquest of Guangzhou, unable to stop the massacre, Jin Guang managed to shelter in his residence many of those who had earlier resisted the Qing army. He helped publish Bianxing tang ji. Footnote 75 Through him, Dangui was able to secure generous sponsorship from Shang Kexi and probably also gain access to some classified information, such as learning of the 1770 arrest of Monk Wuke, formerly known as Fang Yizhi.Footnote 76

During the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, Jin Guang was killed by Shang Kexi’s estranged son, Zhixin 之信 (1636-80), for refusing to collaborate with Wu Sangui.Footnote 77 In Jin Guang’s praise, Dangui pictured him as a true hermit who concealed himself in the army of the bloodthirsty general to save lives or the Samantabhadra bodhisattva known for benefitting all sentient beings.Footnote 78 He argued that, in an apocalyptic world, bringing benefits to living beings was more honorable than hiding in the mountains for self-preservation and a good name. In the same spirit, Dangui laboriously requested official patronage for the sangha that had become the haven of many displaced literati families.

In 1661, a patron and former colleague gifted Dangui an entire mountain to establish a new monastery. This is the Danxia Mountain, located in northern Guangdong on its borders with Hunan and Jiangxi; it was bought in 1646 by Li Yongmao 李永茂 (1601–48; jinshi 1637), Governor of Southern Jiangxi of the Longwu court, as a refuge for his extended family and friends. A native of Henan, Li Yongmao named his newly acquired property after a mountain from his hometown. After his death, his younger brother, Chongmao 充茂 inherited the ownership of Danxia. Both Li brothers were former colleagues of Dangui, and Chongmao had been a lay disciple of Hanshi before giving the Danxia property away. He took tonsure from Hanshi and received the dharma name Jindi 今地, becoming a monk in Danxia Monastery.Footnote 79

Mount Danxia includes a scenic mountainous area in the Nanling Mountains, the major mountain range in southern China that separates the Pearl River Basin from the Yangtze Valley. Winding through the Danxia area is the Jin 錦 River, a tributary of the Pearl River, which accommodates inland waterway transport to tributaries of the Yangtze River. Danxia was situated on the outskirts of Renhua 仁化 county, the northmost county in the Shaozhou prefecture, which bordered the Ganzhou prefecture 贛州, Jiangxi, on the southwest and the Chenzhou prefecture 郴州, Hunan, on the southeast. Owing to its history of being a corridor of the north–south travel route along which Chinese migrants moved southward to the Lingnan region, today’s Shaoguan has remained an important homeland for the Hakka population. Mount Danxia is now a UNESCO World Heritage site famous for its landscape of red sedimentary sandstone formations; it encompasses 292 square kilometers and a group of 680 mountains. Its landscape is characterized by sandstone and conglomerate sedimentary beds formed by endogenous upward forces more than a hundred million years ago, and another million years of weathering and erosion formed the landforms of red cliffs and towering rock formations amidst forests, streams, and ravines.

The Li brothers found the mountain an ideal haven because of its scenery and strategic location. They continuously built preliminary staircases, huts, and lodgings there. After Dangui settled in Danxia, he helped raise money and supervise the construction of the monastery complex on Abbot Hanshi’s behalf. The project included trails, staircases, bridges, carving out grottos and chambers, and building halls, towers, and pagodas to accommodate the growing number of monks and lay population.Footnote 80 For the construction of the monastery and the daily necessities of its sangha, Dangui regularly sent requests for patronage to officials in Renhua, Guangzhou, and neighboring counties in Jiangxi and Hunan. He reciprocated their support with writing, painting, and calligraphy. A frugal monk, he was nevertheless entangled in the web of social obligations to ensure the survival of his monastery community. His extraordinary effort to build and maintain Danxia Monastery seemed to have paid off. The gazetteer of Danxia contains a wealth of stories about the monk and his life there. It also includes records of daily gatherings, lectures, and discussions of the sangha community and writings about Danxia by Dangui and others. Often lingering at various mountain sites during different times of the day, he compared Danxia’s spectacular landscape with the writing of Zhuangzi, marvelous and unpredictable, which was his favorite.Footnote 81 Also preserved in the gazetteer is the memory of how the monastery had accommodated those displaced literati and former officials, some along with extended family members.Footnote 82

After the Revolt of the Three Feudatories broke out, however, Guangzhou and Shaozhou were again subject to destruction from military operations. Continuous warfare fostered banditry, leaving Danxia Monastery in dire poverty. During the period, Dangui led the monks to collect and bury the remains of war victims in the neighboring regions of northern Guangdong, southern Hunan, and southwest Jiangxi.Footnote 83 Some tried to probe if he would cooperate with Wu Sangui, who claimed to revolt against the Manchu rule in the name of Ming loyalism. Dangui rebutted Wu’s credentials and refused the proposition. He had accepted the Qing as a legitimate order. He did not consider collaboration with the Manchus as unethical, perceiving the Manchu–Han ethnic distinction as irrelevant in evaluating governance and moral choices.Footnote 84

Now the monk was old and frail, he knew his days were numbered. He decided to journey to Zhejiang to request the Tripitaka formally. In 1678, he passed the abbacy of Danxia on to Jinbian Leshuo 今辯樂說 (d. 1697), a native of Guangzhou, and bid farewell to his dharma teacher Tianran Hanshi, closing the long chapter of his life in Lingnan. He cut off family ties with his adult children. Returning to Zhejiang, he was again connected with a circle of friends and long-term patrons, including Cao Rong, Xu Qianxue, and Lu Shikai 陸世楷, previously a major patron of Danxia Monastery and prefect of Nanxiong, Guangdong. Xu Qianxue and Dangui initially favored Huangshan and Mt. Lu as possible sites for retirement, but neither was possible with the monk’s worsened health condition. He stayed among old friends and attendants in Songjiang and Jiaxing until his death in 1680.Footnote 85

Conclusion

Monk Dangui was an unlikely subject for a posthumous proscription. He did not serve the Qing, his loyalist causes failed, and he eventually changed his attitude toward the Manchu rule before dying and being buried as a monk. What was at stake in the Dangui case? It triggered an empire-wide mobilization of administrative resources, diminished the prospect of an old bannerman family, and set the tone of historiographical projects about the Ming–Qing transition.

The censorship of Dangui’s works in 1775 showcases the extent of control Qianlong intended to claim over his empire’s geography and history. Despite his unprecedented power and influence accomplished over and beyond China, the emperor was always aware that Manchu rule was precarious. Challenges came from within and outside the capital: the Gao Yuncong case in 1774 exposed a network where officials and court eunuchs trafficked power and wealth under the emperor’s nose; following that, the Wang Lun uprising almost took over the city of Linqing. Though quickly dealt with, the two incidents revealed how covert official networks might diminish the imperial authority and how readily religious networks and sectarian movements could lend themselves to leveraging Manchu–Chinese ethnic tensions.

The sociopolitical influence of local and interregional religious communities during the early Qing consolidation of imperial order deserves more attention. Though the Qing government quickly engaged the cultural elite by coopting the civil examinations and Neo-Confucian ideology, the same cannot be said about Buddhist and popular religious communities. They thus become an important window into the history and memory of seventeenth-century China. Monk Dangui exemplifies a case of the close ties Buddhist monasteries had maintained with regional and transregional literati circles, powerful patrons, and bureaucracy. The monasteries are known to have been a shelter for the literati during the Ming–Qing transition; less discussed are the complex stories of those displaced Buddhist networks and their potential political agency. A locus in which names and memories had been kept alive until the mid-Qing period, these monasteries remain a depository of writings and art objects, some of which have been preserved up to this day.

When Gao Gang published the edition of Bianxing tang ji in the 1730s as the prefect of Shaozhou, he probably was following what his predecessors had been doing—maintaining connections with Danxia Monastery and engaging the legacy of its founder. Presumably, it was Monk Dangui’s image as a respected literatus, loyalist, and eminent abbot rather than his outworn anti-Manchu stance that Gao Gang was endorsing as a Han bannerman, given that his grandfather had died defending the Manchu rule and that his family had thrived in part on that honor. There had been a limit to the reach and extent of imperial control. That dynamics changed after the mid-eighteenth century is shown in the growing numbers of regional revolts and trials of literary inquisition directed by the central government. The military commissioner Li Huang’s report of the Dangui case began with a disclosure of a cherished secret of the local community in return for the prospect of ranks and titles at the empire’s center—yet the fortune resulting from that exchange appeared to be short-lived in the eyes of those who were acquainted with the secret.

Less expected was that the Dangui case fostered the historiographical projects of the late 1770s. Based on the local knowledge from this case, Qianlong was able to piece together the threats posed by interreligious networks that had not been previously noticed and historical memory not decoded, both suggested that loyalty was highly at stake, especially that of the Han bannermen outside the imperial center. There was probably no way to tame all the ramifications of memories of Ming loyalism at a myriad of local sites; the emperor thus commissioned official historiographical projects—in particular, Shengchao xunjie zhuchen lu and the Erchen zhuan—to contain and channel historical narratives.

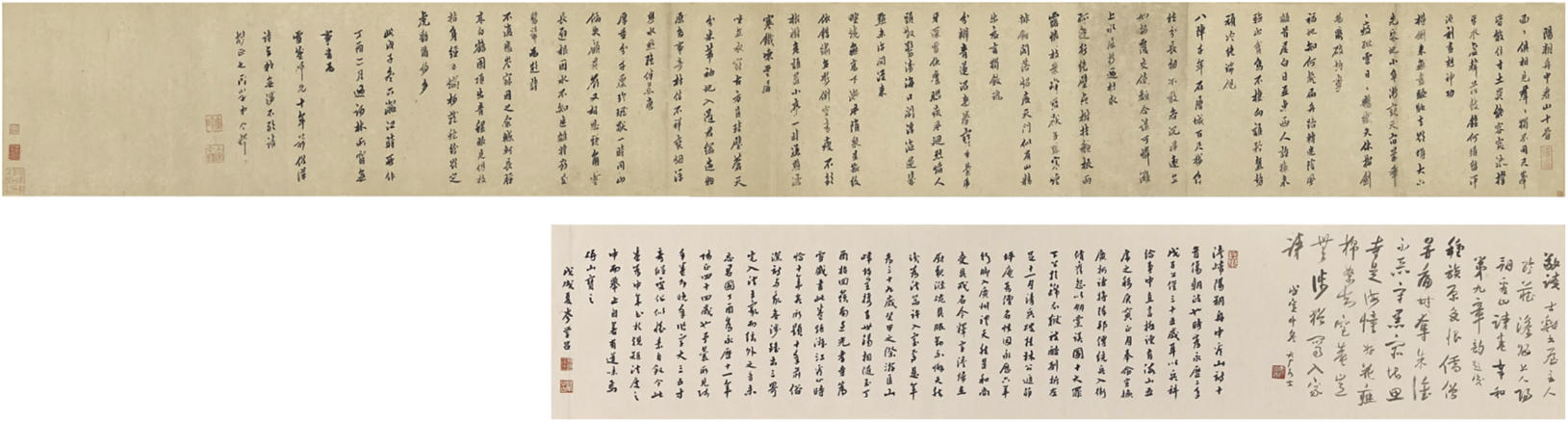

Finally, at the center of this inquisition storm, the cryptic legacy of the monk Jinshi Dangui, or Jin Bao, has proven to be more lasting than the censorship itself. To this day, his writings are still preserved in anthologies and local gazetteers, often under his various names, a copy of his diary manuscript has been preserved in Puji Monastery in Macao, and artworks attributed to him are still circulating in the international art market, including at Sotheby’s (Figure 3). In the end, all these legacies were presumably not essential to the monk Dangui, who was most well-versed in the Zhuangzi and Chan Buddhist teachings. He left them all behind, and probably never minded.

Figure 3. Top: Calligraphy in cursive style. Ten poems titled “In Yangshuo, Watching the Mountains inside the Boat” (陽朔舟中看山). Calligraphy dated 1657 in Guangzhou. The poems were composed during 1648–49 (the winter of the wuzi 戊子 year). Two seals of the author: “Jinshi” and “Dangui.” Bottom: Colophon by the collectors. Cen Xuelu 岑學呂 (1882–1963) provides a biography of Jin Bao/Dangui.