Introduction

Ninety percent of clinicians reported child symptoms are often unrecognized (Skeens et al. Reference Skeens, Cullen and Stanek2019), threatening optimal symptom management and quality of life. The routine use of caregiver proxy and clinician reports, rather than child self-report to solicit children’s symptoms is common in clinical settings (Leahy et al. Reference Leahy, Feudtner and Basch2018). Clinicians assess symptoms by observing children’s behaviors, seeking caregiver perspectives, and less frequently asking the child directly (Linder and Wawrzynski Reference Linder and Wawrzynski2018). Yet, parent and clinician proxy raters often overestimate physical symptoms, while underestimating psychological symptoms (Freyer et al. Reference Freyer, Lin and Mack2022; Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Vos and Raybin2021; Zhukovsky et al. Reference Zhukovsky, Rozmus and Robert2015). Overreliance on proxy raters may mute the child’s voice and yield inaccurate data impacting the communication of potential treatment-related toxicities to children and caregivers (Freyer et al. Reference Freyer, Lin and Mack2022). More concerning, psychological symptoms and emotional needs are commonly unrecognized compared to physical symptoms in children undergoing cancer treatment (Skeens et al. Reference Skeens, Cullen and Stanek2019), leading to long-term negative psychosocial consequences throughout survivorship (Brinkman et al. Reference Brinkman, Recklitis and Michel2018). Integrating patient-reported outcome (PRO) symptom monitoring has been proposed as 1 solution to illuminate the child’s voice in symptom assessment (Leahy et al. Reference Leahy, Feudtner and Basch2018), increase symptom recognition, and optimize symptom management. However, early-adopters of PRO integration describe challenges in navigating discrepant reports between child–caregiver dyads (Leahy et al. Reference Leahy, Feudtner and Basch2018).

The reasons for persistent symptom suffering, disagreement between symptom reports, and lack of symptom recognition are likely complex and remain unknown. Communication is a central tenet of care for children with cancer and their caregivers and is critical to effective symptom assessment and management. Thus communication may underly disagreement (Tomlinson et al. Reference Tomlinson, Plenert and Dadzie2021), and represents a potential target for intervention to enhance agreement in dyad symptom reporting, thereby mitigating symptom suffering. Research examining dyads is necessary to understand discrepancies in symptom reports (Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Wang and He2018). This qualitative research study sought to enhance our understanding of child and caregiver perspectives of cancer symptoms. Specifically, we explored potential factors that may explain the level of agreement and/or disagreement between children’s and caregivers’ reports of 5 priority symptoms. Three physical (pain, fatigue, and nausea) and 2 psychological (anxiety and depression) were selected based on their high prevalence during cancer treatment (Withycombe et al. Reference Withycombe, Haugen and Zupanec2019) and our previous research (Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Vos and Raybin2021). Through soliciting individual perspectives within a child–caregiver dyad, we hope to uncover factors influencing levels of agreement in symptom reports and inform future symptom interventions.

Methods

Study design

This was a single-site exploratory qualitative study grounded in ontological and epistemological positions of relativism and constructivism, or the belief that multiple realities exist, and those realities reflect social constructions of the mind (Guba and Lincoln Reference Guba and Lincoln1989). For purposes of this study, we purport that children and their caregivers experience distinct realities in the context of the child’s cancer treatment and related symptoms. The study was broadly guided by the theory of unpleasant symptoms (TOUS), which acknowledges the importance of using PROs to understand the symptom experience and has been used in pediatric oncology (Lenz et al. Reference Lenz, Pugh and Milligan1997; Silva-Rodrigues et al. Reference Silva-Rodrigues, Hinds and Nascimento2019). The theory also considers factors (physiologic, psychologic, and situational) influencing complex symptom experiences (Silva-Rodrigues et al. Reference Silva-Rodrigues, Hinds and Nascimento2019), making it well-suited for this study.

Setting and participants

Dyads were recruited by clinicians using purposive sampling from a single pediatric cancer center between January and December 2022. Eligible children were aged 8–17, diagnosed with a hematologic malignancy or non-central nervous system solid tumor, undergoing cancer treatment for at least 3 months, and English speaking. The rationale for including children representing school and adolescent age groups was to align with validated PRO symptom measures. Additionally, the inclusion of the 2 age groups allowed us to examine the feasibility of recruiting children in both groups. Caregivers were eligible if they were a primary or co-primary caregiver and able to understand and speak English.

Procedure and materials

Following consent and assent procedures, a research team member extracted child demographic and disease information from the medical record. A date and time for data collection was coordinated with the dyad and based on the total estimated time (75 minutes) needed to complete a sociodemographic questionnaire (caregiver; 5 minutes), an abbreviated 5-item Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS), including pain, nausea, fatigue, worry, and sadness (5 minutes), and a semi-structured qualitative interview (30 minutes). Five-items from the MSAS 10–18 and MSAS 7–12 versions (Collins et al. Reference Collins, Byrnes and Dunkel2000, Reference Collins, Devine and Dick2002) were selected for ease of integrating into the participant interviews. Child and caregiver participants were interviewed individually in separate physical spaces in the clinical or home setting. The sociodemographic questionnaire and MSAS data were collected and managed using research electronic data capture (REDCap) tools hosted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health (Harris et al. Reference Harris, Taylor and Thielke2009). Completed MSAS items were reviewed in real time by a research team member and incorporated into the semi-structure interview for all participants. A trained research team member completed all interviews using a 5-question interview guide with additional prompts. Using participant MSAS responses, interviewers asked about (1) clues that help children know they are experiencing a symptom, (2) how children think their caregiver knows they are experiencing a symptom, (3) advice for other kids when talking about symptoms or feelings with their caregivers, (4) advice for other kids when talking with their healthcare team, and (5) anything else participants wanted to share. Caregivers were asked similar questions, but from the perspective of their child’s symptoms and symptom intensity. Participants could complete the interview virtually using the online platform Webex by Cisco or in-person. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed using the NVivo transcription module, and de-identified and checked for accuracy by 2 research team members (NA, MB, EG, LN) prior to analysis.

Data analysis

Qualitative interview data were stored and managed using NVivo 13 (2020, R1) and analyzed using a 3-phase content inductive analysis technique (McLauglin & Marascuilo, Reference McLaughlin and Marascuilo1990). The first 3 interviews from the child group and 2 interviews from the caregiver group were analyzed using open coding by the team to identify individual units of analysis. The remaining 29 interviews were independently analyzed by at least 2 trained research team members (NA, MB, EG, and LN). After the open coding was completed, inter-rated reliability (IRR) was calculated between independent coders, and the team members met to reconcile any major discrepancies and note any new codes. Next, 3 team members (KEM, NA, and MB) independently generated themes and organized codes into the themes. The team met to discuss themes and determine the best fit for each code. Finally, the team developed names and definitions for each theme and selected exemplar quotes from dyads representing different levels of agreement (low, moderate, or high). Qualitative data corresponding to the advice questions from the interview guide were analyzed separately because participants reflected on actions or behaviors that may not have represented their experiences.

Several techniques were employed to enhance trustworthiness during qualitative data analysis. First, member checking was used to operationalize credibility. After the analysis, a summary of results was shared with one participating child–caregiver dyad. Second, dependability was ensured by creating a standard operating procedure manual for all study procedures and conducting a team review of the first 3 participants whom data were collected. Confirmability was established by ensuring accessibility of audit trails within REDcap and NVivo for quantitative and qualitative data respectively. Further, interviewer field notes were captured for each participant interview within REDcap to facilitate reflexivity through the study period.

Quantitative symptom data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Dyads were assigned an agreement category based on matched child and caregiver responses to the presence of each of the 5 symptoms assessed. Dyads were categorized as having a high level of agreement (5 symptoms), moderate level of agreement (3–4 symptoms), or low level of agreement (0–2 symptoms).

Results

Twenty-eight child–caregiver dyads were eligible during the study period. Of those, 5 dyads were not approached due to healthcare team deferment for psychosocial (n = 2) or medical reasons (n = 3). Twenty-three dyads were approached for consent and 3 declined study participation (no reason offered) and 3 were lost to follow up. Seventeen dyads were consented and completed data collection. One child participant’s interview yielded insufficient data and was excluded from the analysis. A final sample of 16 dyads (32 matched child and caregiver participants) was analyzed. Demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Notably, there was an equal representation of children in the 8–12 (n = 8) and 13–17 (n = 8) age groups.

Table 1. Sample characteristics for N = 16 dyads

Abbreviation: USD, United States dollar

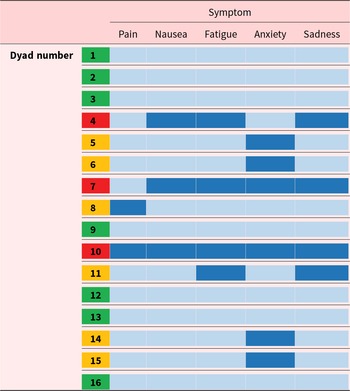

All participants completed the abbreviated symptom measure. Nearly half (n = 7, 43.75%) of child–caregiver dyads had a high level of agreement across all symptoms. The remaining dyads had either a moderate level of agreement (n = 6, 37.5%) or a low level of agreement (n = 3, 18.75%). Disagreement between child and caregivers was highest for the symptoms of anxiety, sadness, and fatigue (Table 2). There was no difference in age groups across levels of agreement.

Table 2. Level of agreement between symptom reports by child–caregiver dyad

Note: Light-blue boxes indicate agreement in the presence of the symptom, green boxes indicate a high level of agreement across 5 symptoms, orange boxes indicate a moderate level of agreement across 3–4 symptoms, red boxes indicate a low level of agreement across 0–2 symptoms.

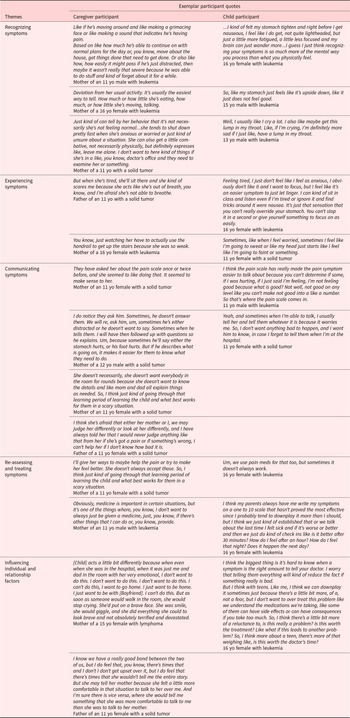

Thirty-two interviews from 16 child–caregivers were analyzed. The median interview was 14 minutes (range 9–23) for child participants and 19.5 minutes (range 11–35) for caregiver participants. A total of 38 unique open codes were referenced 1,235 instances across child and caregiver interviews. The IRR was ≥0.94 for all open codes. Five themes emerged from the data: (1) recognizing symptoms, (2) experiencing symptoms, (3) communicating symptoms, (4) re-assessing and treating symptoms, and (5) influencing individual and relationship factors. In Figure 1, the themes are illustrated, showcasing the notable intersections observed between these thematic elements conveyed by both children and caregivers. The highest number of references came from theme 3 (n = 327, 27%), followed by themes 2 (n = 282, 23%), 1 (n = 265, 21%), 4 (n = 222, 18%), and 5 (n = 139, 11%). Participants shared stories representing their individual perspectives with their/their child’s symptoms. Exemplar quotes are in Table 3 and matched comparative quotes child–caregiver participants scoring quantitatively low, moderate, or high levels of agreement are displayed in Table 4.

Figure 1. Observed Cycle of Qualitative Themes.

Table 3. Themes and exemplar participant quotes

Table 4. Matched comparative child–caregiver exemplar quotes

Recognizing symptoms

Dyads described how they recognize symptoms. Children shared vivid memories of a symptom-onset and described, in detail, the initial physical and mental changes. Children perceived that their caregiver recognizes when a symptom is occurring by their instinct and by looking. Caregivers echoed children’s perceptions by describing how their child’s deviation from normal behavior patterns or emotional states is a major cue that a symptom is occurring. Caregivers conveyed a sense of pride in monitoring for and observing for any magnitude of change in their child’s behavior and emotions. However, this was juxtaposed with several caregivers expressing challenges to recognizing their child’s symptoms, especially regarding the child’s developmental level.

Experiencing symptoms

Children depicted experiencing physical and psychological symptoms and enduring physical and mental changes beyond symptom onset. They also shared how engaging in everyday activities or hobbies were disrupted when symptoms werefrequent, severe, or distressing. Caregivers recalled detailed situations when their child experienced intense physical or psychological symptoms, resulting in uncertainty and fear.

Communicating symptoms

Children shared instances when they communicated openly with their caregivers about symptoms, particularly physical symptoms. The child’s intention to share their feelings was connected to influencing relationship factors and the belief a caregiver could help. The child frequently engaged in open communication when caregivers directly inquired about their symptoms, emphasizing the child’s belief in their understanding of their symptoms.

Challenges with child–caregiver symptom communication corresponded with the child intentionally or unintentionally withholding information about symptoms. The child’s motivation for withholding information was not always clear, however children expressed forgetfulness, not wanting to bother their caregiver or clinician, and desire to deal with the symptom on their own as reasons for not communicating.

Re-assessing and treating symptoms

Dyads endorsed using numeric scales to assess and reassess symptoms, and to guide when interventions were needed. Participants discussed using pharmacologic interventions, but also noted limitations with medicine and/or a desire for non-pharmacologic strategies. Children described engaging in developmentally appropriate play or using breathing techniques to distract from and manage symptoms. Caregivers also referred to a learning period, during which they acquired an understanding of their child’s responses to various aspects of treatments.

Individual and relationship influencing factors

Individual and relationship influencing factors was present throughout, encompassing all the aforementioned themes. Children acknowledged their tendencies to ignore or downplay symptoms, influencing their symptom recognition and experiences. These tendencies were attributed to personality traits or preferences, a willingness to tolerate a symptom, or perceiving experiences as less important compared to what other children may be experiencing. The tendencies were thematized as individual influencing factors because of their subsequent impact on the child’s symptom perceptions and decision to communicate, or not, their symptoms to their caregiver or clinician.

Caregivers also perceived similar child-specific tendencies as reasons for the child’s blunted physical or mental changes to symptoms or motivation for communicating or withholding information about symptoms. Caregivers and children also identified child–caregiver connectedness as a relationship factor that affected symptom communication. Caregivers who perceived being emotionally close with their child, often felt the child communicated more openly about symptoms. In contrast, children described natural changes in their child–caregiver connectedness, resulting in growing apart and a lack of communication with a caregiver.

Advice for other children and caregivers

Inquiry into the advice children and caregivers might offer to peers was assessed independently, as many participants shared guidance rather than reflecting on personal experiences. Children emphasized the importance of trusting, not downplaying what you feel, and not being afraid to communicate symptoms to a caregiver or clinician.

I would say just don’t be afraid to tell the truth to your parents. 11yo male, leukemia

But I guess my advice would be that, just communicate that you don’t think it’s that big of a deal versus saying nothing, because sometimes I think, oh, I shouldn’t make a big deal about this. 16yo female, leukemia

Children discussed how talking about their symptoms with someone is the best way to get help for those symptoms.

I know there’s probably some symptoms that people like kids don’t want to talk to their doctors about, but they should because it helps them. 15yo male, leukemia

Finally, children acknowledged the individual with whom they discuss their symptoms may not always be a parent or caregiver. Suggesting children should seek someone they trust to share their feelings with.

Tell them, you know, everything you feel comfortable with, and if not, there’s things you don’t feel comfortable telling them. Tell someone. Because not everyone unfortunately is super close with their parents, so as long as they tell someone they can trust. 17yo female, leukemia

Caregivers expressed similar sentiments as children, emphasizing the need to monitor your child, trust your gut, and avoid dismissing small changes in their child.

I guess the big ones are to watch and listen, I mean. You know, most parents know how their children act normally. You just got to watch for the subtle hints, sort of subtle changes that they may make or start to make. Father of an 11yo female, leukemia

Additionally, caregivers shared advice for how to ask children about symptoms, highlighting the need to be transparent about your motivation for asking questions.

I think to find out to know more, you know, make them feel comfortable, make them understand that you’re asking a question because you want to make sure they feel good and you don’t want them to be upset and that you’re not trying to just pry into their business. Father of an 11yo female, solid tumor

Caregivers discussed the importance of open communication, role modeling active listening, and validating your child’s feelings.

Make sure you’re listening, and if they don’t have the vocabulary to describe how they’re feeling. Give them some options because then it might kind of make sense to them and make it easier for them to describe how they’re feeling to their parents and their caregivers or providers. Father of a 15yo male, leukemia

Finally, caregivers recognized the importance of being receptive to the possibility that children may not be willing to discuss certain emotions with them and may need another trusted adult to confide in.

Maybe leave some doors open as far as communication with other adults and in the child’s life, too, if possible. Mother of a 15yo male, leukemia

Discussion

Findings from this exploratory qualitative study provided valuable insights into child–caregiver experiences and level of agreement with cancer-related symptoms. The study’s findings suggest children undergo a symptom cycle, described by dyads as encompassing the stages of symptom recognition, lived experiences, communication, and management. While caregivers and children endorsed these themes, in-depth analyses revealed that individual and relationship factors may influence children’s symptom cycle, including their communication with caregivers and clinicians, resulting in altered perceptions and open or disrupted communication. Children and caregivers reported how individual and relationship factors, like a child’s willingness to tolerate a symptom and child–caregiver connectedness, affect the child’s symptom experiences and subsequent communication with a caregiver and clinicians. Disrupted or closed communication was more prevalent among child–caregiver dyads with moderate or low levels of agreement. The concept of child–caregiver communication is not new to pediatric oncology (Son and Kim Reference Son and Kim2024), however the lack of communication between child and caregiver dyads in the context of symptom reporting has only recently been documented as a possible reason for disagreement in reports (Tomlinson et al. Reference Tomlinson, Plenert and Dadzie2021). Children and caregivers also described how their dyadic relationship helped to facilitate or hindered symptom communication. Literature describing child–caregiver communication is limited, exclusive of the child’s voice, and focused on sharing information about a cancer diagnosis (Son et al. Reference Son, Haase and Docherty2019).

Child and caregiver descriptions of the symptom cycle also reflect the intersection of the child’s age and developmental level and cancer treatment. We have a better understanding of how age and developmental level may influence symptoms and symptom management (Jibb et al. Reference Jibb, Ameringer and Macpherson2022), but less is known about how such factors influence child–caregiver communication (Son and Kim Reference Son and Kim2024). Findings of this study, coupled with child cognitive developmental theory, suggest age and developmental level could be further explored as factors influencing the child’s symptom cycle. Based on Piaget’s theory (Piaget Reference Piaget, Green, Ford and Flamer1971), children begin to decenter but still have difficulties with abstract thinking compared to children and adolescents in the formal operational stage, and thus may experience their symptom cycle differently.

The results of the quantitative symptom analysis revealed the study included a diversity of perspectives, representing dyads with low, moderate, and high levels of agreement. This variance in agreement levels quantitatively, yet qualitative congruence underscores the complexity of symptom communication and recognition within these relationships. Furthermore, an interesting finding emerged concerning the specific symptoms where disagreement and subsequent qualitative descriptions between children and caregivers was most pronounced. Perceptions varied notably in symptoms such as anxiety, sadness, and fatigue. This dissonance in interpretation could stem from differences in how children and caregivers express and perceive emotional and psychological aspects. It may also reflect the unique challenges in accurately capturing and communicating subjective symptoms related to emotional well-being and energy levels (Mack et al. Reference Mack, McFatrich and Withycombe2020).

Limitations

The study’s primary limitation is the inability to generalize the findings to the broader pediatric oncology population given the single-site and, primarily, qualitative design. The role of the quantitative symptom data was to describe the level of dyad agreement among the sample and enable in-depth qualitative exploration of the level of agreement for the presence of a symptom, and, thus, should be interpreted with caution. Exploration of agreement between different symptom attributes, including severity and level of distress may support future clinical application. White participants and female caregivers dominated our sample, limiting the perspectives of underrepresented gender and racial groups. Despite equal representation of children from different age groups, we did not conduct our analysis by age group, which could be addressed in future research. Although we used current symptom reports to guide the participant interviews, some participants may rely on memory recall during interviews, introducing the possibility of recall bias. Finally, the study was cross-sectional, and the fixed nature of the interviews may have restricted the exploration of emergent or unanticipated themes that could arise in a longitudinal design.

Research and clinical implications

Disagreement between reporters is well documented (Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Vos and Raybin2021; Tomlinson et al. Reference Tomlinson, Plenert and Dadzie2020; Weaver et al. Reference Weaver, Wang and Reeve2024), however the clinical impact of disagreement about a child’s symptoms is less clear (Weaver et al. Reference Weaver, Jacobs and Withycombe2022; Porter et al. Reference Porter, Hinds and Wiener2023). Symptom assessment may be more complex than administering patient- and proxy-reported symptom questionnaires, and researchers have proposed sharing symptom reports as one way to promote open communication between the patient and family members (Porter et al. Reference Porter, Hinds and Wiener2023). It prompts an exploration into the factors influencing these differences, including communication dynamics, individual perspectives, and potentially varied coping mechanisms adopted by children and caregivers.

The role of a child’s age or developmental level on their symptom cycle is understudied, especially in relationship to PRO symptom agreement (Porter et al. Reference Porter, Hinds and Wiener2023) and child communication during cancer treatment (Sisk et al. Reference Sisk, Schulz and Blazin2021). Wide age ranges in pediatric symptom and palliative care qualitative research are well-documented (Ghirotto et al. Reference Ghirotto, Busani and Salvati2019; Jibb et al. Reference Jibb, Ameringer and Macpherson2022), leading to an opportunity to stratify samples by age and developmental level. Considering developmental and cancer contexts, future research can identify modifiable- and non-modifiable factors to consider for supportive care intervention development.

Addressing symptoms throughout cancer treatment is a focus in clinical practice and research, necessitating a comprehensive and multifaceted approach. PRO symptom monitoring, guideline-concordant care responsive to PRO symptom data, and comprehensive patient and family symptom education are key building blocks for holistic symptom management. Researchers call for PRO symptom monitoring that prioritizes the child’s voice and includes additional important perspectives of family members (Hinds et al. Reference Hinds, Grossoehme and Reeve2023). A recent study of dyadic symptom reporting found differences in individual symptom scores between child and caregiver dyadic-reports and caregiver-proxy reports, but no significant changes between total symptom scores and report type (Tomlinson et al. Reference Tomlinson, Tardif-Theriault and Schechter2023). This suggests that dyadic symptom reporting may facilitate a unified family voice for reporting symptoms to clinicians. Our limited data from this study suggests a disconnect between dyad-reported quantitative data and what is qualitatively recognized. Further work is needed to better align symptom recognition with reporting and communication.

Responding to PRO symptom data with evidence-based interventions is another key building block to addressing symptom suffering. However, pediatric-specific clinical practice guidelines for commonly experienced symptoms are limited and not yet integrated into routine clinical care (Dupuis et al. Reference Dupuis, Cook and Robinson2019; Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Tomlinson and Beauchemin2021). Educating children and their families about side effects of treatment is a recommended component of new diagnosis education (Landier et al. Reference Landier, Ahern and Barakat2016) and established international nursing-sensitive quality indicator (Sullivan et al. Reference Sullivan, Day and Ivankova2023). Yet, content and interventions that are developmentally tailored and specifically address child–caregiver communication as part of symptom assessment and management are lacking. This content gap was supported by participants’ statements advising peers on how to communicate with a child or caregiver, including tenets of effective communication.

To advance the next generation of symptom interventions, a holistic and contemporary symptom theory is needed (Skeens and Montgomery Reference Skeens and Montgomery2024). The TOUS includes inter-related physiologic, psychologic, and situational factors specific to the individual experiencing a symptom. However, the role of caregivers within the model is absent (Silva-Rodrigues et al. Reference Silva-Rodrigues, Hinds and Nascimento2019), suggesting an opportunity to contemporize the model with new research that reflects the complexity of symptom assessment and management in the context of pediatric cancer. Adding nuanced individual and relationship factors may generate tailored symptom communication interventions to promote the efficacy of symptom management.

This exploratory study revealed congruence in themes despite quantitative disparities, underscoring the complexity of symptom communication and recognition within these relationships. Dyad disagreement prompts an exploration into its clinical impact and suggests the need for more nuanced symptom assessment approaches. Addressing these disparities is crucial for optimizing supportive care for children with cancer, emphasizing the importance of holistic symptom management that considers both physical and emotional dimensions. Findings suggest a symptom cycle in children with cancer, highlighting the influence of individual and relationship factors on symptom experiences and communication with caregivers and clinicians. The study encourages tailored interventions informed by understanding these factors, signaling a need for contemporary symptom theory.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was written by KEM. KEM and MAS contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by KEM, NA, MB, EG, and LN. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript and approved the final version for publication. The authors are grateful for the children and caregivers who shared their experiences through this study.

Funding

This project was supported in part by the UW cancer center support grant (P30CA014520).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Review Board (2021–1121).