1. Introduction

Like many international lawyers, we sometimes turn to the scholarship of social scientists in search of different perspectives on the legal issues before us. In the work of economists, political scientists and international relations scholars, for example, we have found insights into legal issues that are perhaps best approached by stepping a little outside of the field of public international law. But as lawyers by training, we inevitably engage with social science research at a distance, as outsiders. We sometimes also engage with social science research with a heightened awareness of how different our training is, and the difficulties involved in trying to ‘step into’ disciplines that have their own distinct vocabularies, methods, and theories.Footnote 1

While we have regularly given thought to how we view, and might make use of social science research, we have had relatively few occasions to think about how social scientists view and use the research of international lawyers. After all, opportunities for real time interaction with social scientists have been fairly limited – we have been squared away in different faculties (and buildings) since our days as PhD students, and interdisciplinary conferences or workshops involving lawyers and social scientists seem to be more the exception than the norm. Our professional experiences as lawyers also largely kept us within the legal discipline. We nevertheless think that it is worth pausing to reflect on this alternative perspective – on how social scientists engage with international legal research, and what sort of international legal scholarship social scientists value.Footnote 2

In approaching this question, we have turned to academic grant systems as a proxy for how social scientists perceive international legal scholarship. When lawyers are grouped with social scientists for the purposes of funding schemes, projects on legal topics are evaluated by panels that include social scientists. Such funding schemes therefore provide a natural avenue for exploring the perspective of social scientists on international legal scholarship. By focusing on the international legal projects that have been awarded funding, we hope to gain some insight into what sort of international legal research is valued by social scientists, at least those sitting on the panels of funding bodies. Do panels that include social scientists tend to prefer international legal projects that promise to produce research that looks more like social science scholarship than international legal scholarship? Or do panels also value legal scholarship that remains within the realm of doctrinal legal research?

While research grant systems have attracted some academic scholarship, these particular questions are yet to be addressed in the existing literature.Footnote 3 We hope that this editorial will help to foster more reflection on how researchers trained in different academic disciplines engage with, perceive, and, in some settings, ultimately evaluate the work produced in other disciplines, including the field of law. This editorial begins by setting out our methodology (Section 2) and our findings (Section 3), before offering some reflections on the implications of our findings in the concluding section (Section 4).

2. Methodology

This editorial is motivated by the hypothesis that the panels that evaluate international law projects in the context of grant applications tend to select projects with a non-doctrinal or interdisciplinary approach, or both. In other words, do the panels, which are in part composed of social scientists, prefer international law projects that employ the methods and/or theories of social scientists, rather than purely doctrinal legal approaches to the study of international law?

This editorial focuses on the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (NWO) or Dutch Research Council for reasons of space. But the findings presented in this piece form part of a larger project that also covers the European Research Council (ERC) and the Australian Research Council (ARC). The NWO’s overarching mission is to advance ‘world-class scientific research’ with ‘scientific and societal impact’ by funding ‘excellent, curiosity-driven disciplinary, interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary research’.Footnote 4 Our research focuses on the NWO ‘Talent Programme’, which has operated since 2002. The NWO describes the Talent Programme as a scheme that ‘offers grants to talented, creative researchers’ so that they can conduct the research of their choice. Selection committees are asked to assess project proposals based in part on the projects’ potential ‘knowledge utilisation’, meaning the transfer of knowledge that will be generated with the help of NWO funding. The NWO envisages knowledge being transferred to other scientific disciplines or to ‘users outside of science (industry/society)’.Footnote 5

Like academic grant schemes in other countries, the NWO’s Talent Programme involves individual grants, as opposed to team grants, and it has three tiers. An initial tier consists of ‘Veni’ grants for researchers who recently completed their PhDs (eligibility extends up to three years post-PhD). The next tier consists of ‘Vidi’ grants, which are for more experienced researchers who have conducted several years of research after completing their PhDs (eligibility extends up to eight years post-PhD). The last tier consists of ‘Vici’ grants, which are for senior researchers who have already developed their own lines of research (eligibility extends up to 15 years post-PhD).Footnote 6 These three tiers find equivalents within the individual grants systems of the ERC and ARC.

We gathered information about all law projects selected through the Talent Programme during the 19-year period running from 2002 to 2020.Footnote 7 The decision to cover this entire timeframe was motivated by questions about whether the preferences of panels have shifted over time. For example, are non-doctrinal approaches to international law or particular areas of international law more or less in favour than they were 15 years ago? This editorial focuses on projects within the field of international law, a category that we have defined as excluding European Union law projects. Projects that cover both European Union law and international law have, however, been classified as international law projects for the purpose of this study.

We relied on publicly available information, in particular the NWO’s annual reports, which are available for most but not all years, as well as its project database.Footnote 8 The data was supplemented by a freedom of information request (Wob-verzoek) that we submitted to the NWO. The available information allowed us to gather a range of data concerning selected projects, namely the titles and field of law; basic information about the disciplinary approach and methodology; the year the project was selected; the name, nationality, and gender of the lead researcher; and his or her institutional affiliation.Footnote 9 Our freedom of information request also enabled us to obtain the titles of rejected law projects, but without further information concerning the approaches of the rejected law projects. Because we lack the project summaries of the rejected proposals on legal subjects, this study has its limitations, as we discuss below.

When coding the ‘approach’ of the selected international law projects, we relied on the publicly available summaries of each project, which are contained in the NWO’s project database. These summaries are short (approximately 250 words each) and are written by the lead researchers of the selected projects at the time of application. The brevity of the summaries means that we typically coded the approach of the selected projects on the basis of two or three relevant sentences that addressed methodology and/or interdisciplinarity. The panelists, of course, made their selection decisions on the basis of more detailed information contained in the full project proposals, which are not available to the public. Although the summaries describe the projects’ approaches briefly and with varying levels of clarity, the available information provided sufficient support for the coding that we undertook. On the whole, we found that it was more difficult to code projects with predominantly legal approaches because the applicants sometimes did not describe their methods or perspectives in explicit terms. By contrast, applicants that approach international legal topics from the perspective of other academic disciplines, or through the use of non-legal methods, typically highlighted this in their project summaries.

We did not take into consideration the ‘research outputs’ of these projects, which the project database lists for completed projects. Because some projects are ongoing, this would not have been a feasible method for identifying the approaches of all projects. In addition, our focus on the project summaries, as opposed to the research outputs, is in keeping with our interest in how panellists perceived these projects at the time of application, rather than after the completion of the projects. This also meant that we did not investigate whether the methodology actually employed in the project corresponded with that described in the proposal.

On the basis of the information contained in the project summaries, we coded the projects according to whether they involve the use of doctrinal legal methods; non-doctrinal methods; and whether they approach the subject of international law from an interdisciplinary perspective. The term ‘doctrinal legal methods’ refers to methods of inquiry that focus on ‘what the law says on a particular issue and why it says it’.Footnote 10 Doctrinal legal methods can, for example, involve analyses of what the law means, how judges have interpreted and applied the law, and how different bodies of law interact with each other. Doctrinal legal research can also involve efforts to ‘identify the principles underpinning’ a body of rules, for the purpose of explaining (and/or critiquing) the function of those rules.Footnote 11

For the purposes of this editorial, the term ‘non-doctrinal methods’ refers to ‘the use of methodological tools to assess how, and under what conditions, international law works in practice’.Footnote 12 Non-doctrinal methods may, for example, facilitate the testing of theories or hypotheses through empirical research, which may be qualitative or quantitative in character.Footnote 13 Examples of non-doctrinal methods include interviews, participant observation, content analysis, process tracing, and statistical analysis.

Finally, the term ‘interdisciplinary’, for the purposes of this editorial, refers to the study of international law either partly or entirely from the perspective of another, non-legal academic discipline, such as international relations, political science, philosophy, sociology, economics, and anthropology. The interdisciplinary character of a project may or may not correspond to the academic background of the lead researcher. Some lead researchers who approach their subjects from an interdisciplinary perspective have an academic background in a social science discipline, while others have academic backgrounds in both law and a social science, or only law.

Each project was separately coded with respect to its use of doctrinal legal methods, non-doctrinal methods, and interdisciplinarity. On the basis of this coding, each project falls into one of three categories: first, projects involving only legal doctrinal methods; second, projects involving legal doctrinal methods and either non-doctrinal methods or an interdisciplinary perspective, or both; and finally, projects involving only non-doctrinal methods and an interdisciplinary perspective, with no use of legal doctrinal methods.

3. Findings

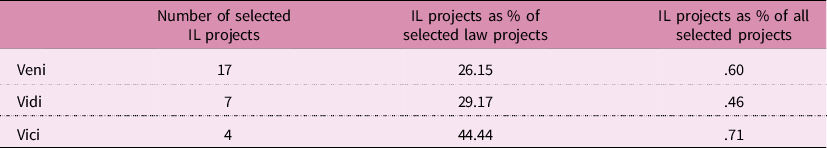

Before delving into the approaches of the selected international law projects, this section first presents some basic information on how many international law projects have been selected by NWO panels during the 19-year period covered in this study. These figures give a sense of how international law projects fare overall in the NWO Talent Programme, and relative to law projects in general. First, in absolute terms, relatively few international law projects have been selected by NWO panels since 2002. In the 19-year period covered in this study, NWO panels selected 17 Veni projects, seven Vidi projects, and four Vici projects concerning international law (28 in total) (Table 1). The international law projects that have been selected through the Veni and Vidi rounds represent more than a quarter of all law projects selected (26.15 per cent and 29.17 per cent, respectively). The four international law projects that have been selected through Vici rounds represent 44.44 per cent of all Vici law projects.

Table 1. Selected International Law (IL) Projects, 2002–2020

Because we do not have complete data on the total number of applications (selected and rejected applications), we are unfortunately unable to determine how successful international law projects are in relation to all applications, or in relation to all applications on legal topics.Footnote 14 These 28 projects represent a limited sample set for this study, and our findings cannot be considered to be generalizable beyond the bounds of this sample; our broader research project, which includes both the ERC and ARC, will provide us with sufficient data to draw more general conclusion. In addition, these 28 projects are not associated with 28 different lead researchers. Ten of these projects have been or are being carried out by five different lead researchers, who were successful applicants at two different tiers of the Talent Programme (e.g., a Veni and a Vidi). The present study does not account for successful NWO applicants who went on to win ERC grants, or vice versa.

The international law projects that have been selected represent a very small portion of the total number of all projects selected through the Talent Programme, at well below 1 per cent (Table 1). Compared to other legal fields, however, international law projects fare quite well.Footnote 15 The data show that international law projects represent a significant portion of the total number of selected law projects, which increases progressively from the Veni, to the Vidi and finally the Vici. The selection of international law projects has been somewhat periodic in character, insofar as one or more years sometimes go by without the selection of an international law project. This observation holds true for all three tiers of the Talent Programme, but is most evident with respect to the Vidi and the Vici. Vidi panels have notably not selected an international law project since 2014.

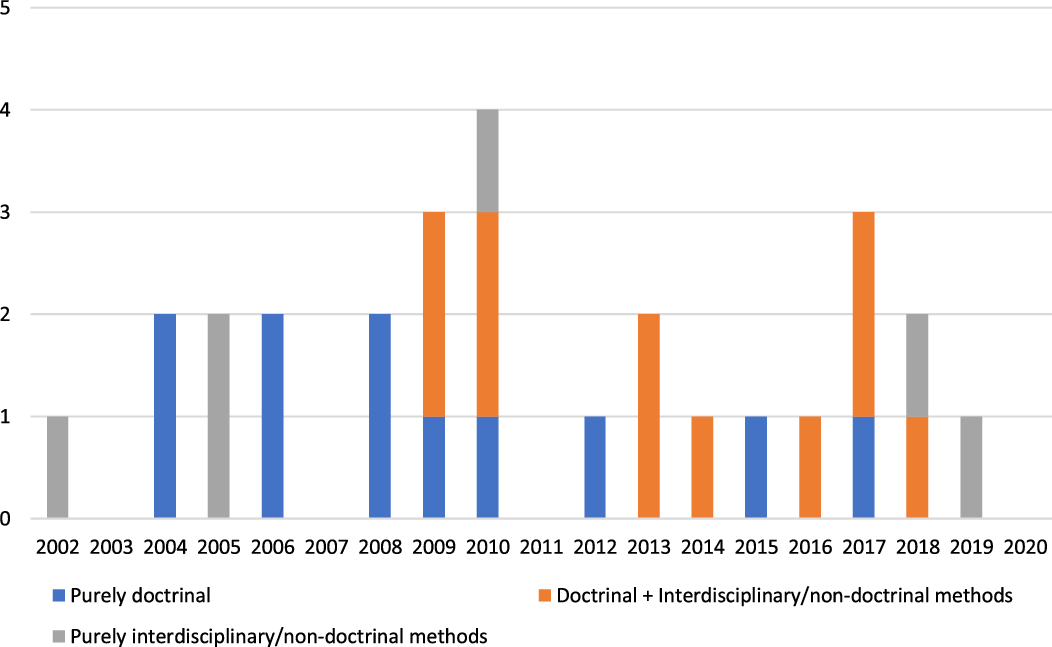

The data could be seen as suggesting that panels favour projects that involve non-doctrinal methods or an interdisciplinary perspective, though other explanations are also possible and plausible. Seventeen out of the 28 selected international law projects involve the use of non-doctrinal methods or an interdisciplinary perspective, and six of the 17 do not involve legal doctrinal methods at all. In other words, approximately 60 per cent of the international law projects adopt approaches that involve either non-doctrinal methods, or an interdisciplinary perspective, or both. The data therefore suggests that panels tend to prefer projects with a non-doctrinal or interdisciplinary approach, but the data do not prove that this is the case. The only way to prove whether this explanation has merit would be to analyse all project summaries, including those for projects that were rejected. Because we lack sufficient data concerning rejected applications, as noted above, we cannot persuasively reach the conclusion that panels prefer such projects, however tempting it might be for us, as lawyers, to try to ‘argue our case’.Footnote 16

An alternative explanation for our findings could be that the approaches of the selected projects mirror the approaches of the applications in general. In other words, it could be the case that approximately 60 per cent of applicants proposing international law projects adopt either non-doctrinal methods or interdisciplinary perspectives or both. It could even be the case that (significantly) more than 60 per cent of the applicant pool plans to pursue non-doctrinal methods and/or interdisciplinary perspectives, in which case project proposals involving doctrinal legal methods have, relatively speaking, outperformed those involving non-doctrinal methods and/or interdisciplinary perspectives. If it is the case that 60 per cent or more of the proposed international law projects involve non-doctrinal methods and/or interdisciplinary perspectives, then this would beg the question: Have researchers adopted non-doctrinal methods and interdisciplinary perspectives only for the purposes of NWO funding applications, or do such approaches reflect their research in general? It is conceivable, for example, that the Talent Programme’s focus on ‘knowledge utilisation’ has encouraged international legal researchers to adopt methods and perspectives, for the purposes of their funding applications, that could potentially enable the ‘transfer’ of their research output to other disciplines, such as the social sciences. As for whether international legal research in the Netherlands involves non-doctrinal methods and/or interdisciplinary perspectives to the extent represented in the projects submitted to and funded by the NWO – this remains a big and, as of yet, unanswered question. The data further show that there has been a shift over time, as the selected international law projects increasingly tend to involve non-doctrinal methods or interdisciplinary perspectives, while projects involving only legal doctrinal methods have become less common (Figure 1). In the first nine years of the Talent Programme (2002–2010), half (eight out of 16) of the selected international law projects involved purely legal doctrinal methods, with no use of non-doctrinal methods or an interdisciplinary perspective – at least according to the project summaries. During this time period, the other half of the selected international law projects involved either non-doctrinal methods or an interdisciplinary perspective, or both (eight out of 16). In the last ten years (2011–2020), however, the vast majority of selected international law projects have involved non-doctrinal methods or interdisciplinary perspectives (nine out of 12). Only three selected international law projects have been entirely legal in their approach, meaning that they involved only the use of legal doctrinal methods.

Figure 1. Approaches of Selected International Law Projects

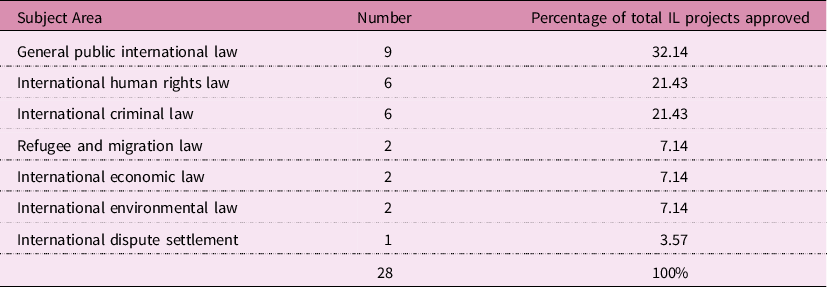

With respect to the subject areas of the selected international law projects, the vast majority of projects have concerned general public international law, human rights law, and international criminal law. To a much lesser extent, panels have selected international law projects in the areas of refugee and migration law, international economic law and environmental law (Table 2). The category ‘general public international law’ captures projects that concern fundamental aspects of international law, such as jurisdiction or law-making, or projects that do not clearly fall into any of the branches of the field, such as human rights law, international criminal law, or international environmental law. A number of significant areas of international law have never been the focus of a selected project, namely international humanitarian law, and the law of international organizations. The data do not reveal any particular shifts with respect to the subject areas of selected international law projects over the 19-year period covered in this study. An open question is the weight that panels assign to the subject matter of proposals, as opposed to the methods and perspectives adopted for the purpose of studying the subject at hand.

Table 2. Selected International Law Projects by Subject Area

Finally, the data show that selected European Union law projects have significantly outnumbered selected international law projects in the last ten years, whereas the reverse was true during the first nine years of the Talent Programme. Between 2002 and 2010, seven European Union law projects and 16 international law projects were selected, whereas between 2011 and 2020, 18 European Union law projects and 12 international law projects were selected.

Our findings show that a significant portion of selected international law projects involve either non-doctrinal methods or an interdisciplinary approach (or both), and that this is increasingly the case. Our data set admittedly has its limitations, however, and does not allow for more than speculation as to what explains this apparent trend towards international law projects with social science dimensions. The trend suggested by this study could have several different explanations, which are not mutually exclusive. It is possible that this trend reflects a change in the application pool, meaning that international lawyers increasingly, or overwhelmingly, submit proposals that entail non-doctrinal methods or a social science approach. It is also possible that the NWO panels, which include social scientists, may prefer international legal research projects that are closer to social science research, because they involve methodologies or theoretical perspectives that are more familiar to them than doctrinal legal work. The data that we have gathered on panel composition will allow us to test, in the context of our larger project, whether a possible correlation exists between panel composition and the approaches of the projects selected.

4. Conclusion

We hope that this editorial will not be seen as implying that international lawyers ought to adopt social science methods, whether to attract funding, or to attract the interest, more generally, of social scientists. While some questions about the law may be answered, in part, by stepping somewhat outside the legal discipline, doctrinal legal research arguably remains mainstream in legal scholarship, as this is what most legal academics have been trained to do, and there is great value in this type of research, both for legal scholars, legal practitioners, and social scientists. Moreover, although international legal projects that involve non-doctrinal methods and perspectives appear to be increasingly attracting NWO funding, our study suggests that NWO panels still value doctrinal legal research projects to an extent. This is shown, in particular, by the fact that projects that combine doctrinal methods with either non-doctrinal methods or interdisciplinary approaches account for a more significant portion of the projects funded than those that take a purely interdisciplinary approach or that adopt solely non-doctrinal methods. In addition, international law projects that employ purely doctrinal legal methods do indeed secure NWO funding, albeit to a lesser extent now that in the past.

The fact remains, however, that most international law projects selected through the NWO between 2002 and 2020 involved social science dimensions. This finding is notable, in part, due to the fact many legal scholars do not have formal training in social science disciplines. Whether our findings reflect the applicant pool or the preferences of panels, or others factors, remains open to speculation. But we hope that our findings will nevertheless encourage legal researchers to reflect on how or whether social scientists engage with legal research, and how lawyers explain their work and their research plans for other audiences, which may view legal scholarship from very different perspectives.