Introduction

When sentencing former police officer James Forcillo for the police shooting that killed Sammy Yatim on a Toronto streetcar, Justice Then noted: “when a police officer has committed a serious crime of violence by breaking the law which the officer is sworn to uphold it is the duty of the court to firmly denounce that conduct in an effort to repair and to affirm the trust that must exist between the community and the police” (R v. Forcillo, 2016, para. 95). Community trust and confidence in law enforcement are put to the ultimate test when officers act or appear to act outside the boundaries of the criminal law, and these tensions are even more pronounced for communities that have a history of strained relations and distrust of law enforcement. External and civilian oversight of the police can be essential to investigate and respond to allegations of police criminality and impropriety. Ontario relies on the Special Investigations Unit (SIU), a civilian law enforcement agency, to investigate and, where necessary, lay criminal charges against the police. Although the SIU reports how often charges are laid, little is known about the nature of the offences committed; nor do we have an understanding of the prosecution, trial process, and sentencing for police officers, and how this mechanism of police oversight functions in practice.

In this paper, we analyze SIU investigations over a fifteen-year period, tracing each investigation through the justice system. Along with providing an empirically grounded assessment of civilian oversight, we examine 159 SIU investigations where criminal charges were laid against police officers in Ontario. We assess what happens after charges are laid, including conviction and sentencing, and the trends associated with the corresponding data. We find that approximately one-third of all charges laid by the SIU are withdrawn by the Crown prosecution and the most common disposition following trial is an acquittal. Our results indicate that the offence matters—officers charged and prosecuted for driving-related offences are more likely to plead or be found guilty compared with other offences, and officers found guilty of sexual assault will receive a more severe sentence. We also examine the many challenges unique to investigating and prosecuting police officers for criminal activity. We consider what these outcomes mean for the criminal justice system, public confidence in the administration of justice, and police oversight.

Literature Review and Context

Law enforcement requires public confidence and community support to be legitimate and effective. When police officers act (or appear to act) outside of the law, it creates tension in the relationship with the community, ultimately weakening public trust (Tulloch Reference Tulloch2017). When a member of the public dies or is seriously injured during an interaction with the police, public confidence in law enforcement is put to the test and the legitimacy of the police can hang in the balance (Wood v. Schaeffer, 2013, para. 2). These tensions are most pressing for communities that have a legacy of strained relations, distrust, and disproportionately violent interactions with the police, in particular Black and Indigenous communities (OHRC 2018; OIPRD 2018; Tulloch Reference Tulloch2017; Black Experience Project 2014; Wortley Reference Wortley2007; Landau Reference Landau1996). Police oversight and accountability are essential to investigate allegations of wrongdoing and to provide consequences when police have acted in a manner that is improper, inappropriate, and in some cases, criminal.

Canadian police are subject to a variety of accountability mechanisms, ranging from internal oversight, such as governance from police management, codes of conduct, performance and disciplinary measures, to external measures, including civil and criminal legal oversight, police service boards, and civilian complaint and oversight agencies (Roach Reference Roach2014, Reference Roach2018; Scott Reference Scott and Scott2014; Sossin Reference Sossin, Beare and Murray2007; Martin Reference Martin, Beare and Murray2007; Ferdik, Rojek, and Alpert Reference Ferdik, Rojek and Alpert2013; Murphy and McKenna Reference Murphy and McKenna2007). While the importance of internal oversight and how it might contribute to better outcomes for external oversight mechanisms should not be overlooked, our analysis is concerned with external methods of police oversight and accountability. External and public oversight helps to foster good governance by demonstrating that police structures are answerable to democratically elected political actors and ultimately the public (Rowe and Lister Reference Rowe, Lister, Rowe and Lister2015, 6). When responding to allegations of serious police misconduct, like unjustified use of force or sexual assault, internal oversight mechanisms will be viewed by the public with suspicion and as unsatisfactory (Ferdik, Rojek, and Alpert Reference Ferdik, Rojek and Alpert2013; Prenzler and Ronken Reference Prenzler and Ronken2001). Simply put, the public lacks confidence in the ability for police officers to investigate other officers, believing that investigations into complaints will not be fulsome and will be subject to a pro-police bias (Landau Reference Landau1996; Prenzler and Ronken Reference Prenzler and Ronken2001). Methods of external oversight are essential to ensure legitimacy and transparency of the process for the public, the integrity of the outcomes, and to protect the rule of law.

The civilian model of police oversight addresses many of the limits of other methods of oversight, and because it is not directly answerable to the political executive, civilian oversight is independent. Civilian oversight refers to any process that allows individuals who are not currently police officers to participate in and direct complaints about the police (Walker Reference Walker2001). Civilian oversight can be a means to “equalize the balance of power between public officials and citizens” (Ferdik, Rojek, and Alpert Reference Ferdik, Rojek and Alpert2013, 104). Because Canadian policing is founded on citizen consent, civilian oversight can help to restore the balance of power between the police and the community by providing a role for civilians in monitoring police misconduct and, in some instances, directing police practice and addressing systemic issues. One of the central goals of civilian oversight is to increase the public’s confidence in the police and in the institutions tasked with holding the police accountable (Goldsmith Reference Goldsmith and Stenning1995; Prenzler Reference Prenzler, Prenzler and Heyer2016; Ferdik, Rojek, and Alpert Reference Ferdik, Rojek and Alpert2013; Tulloch Reference Tulloch2017). Civilian oversight bodies were created in the United States and Canada in response to a community outcry regarding police activity and practices with racialized communities, in particular Black communities. In the United States, civil unrest in the 1960s and 1970s reinvigorated calls for civilian police oversight, resulting in many jurisdictions adopting some variation of the civilian model, many of which persist to the present day (Ferdik, Rojek, and Alpert Reference Ferdik, Rojek and Alpert2013). In Canada, the creation of the first civilian oversight body occurred in response to community organization and protests in reaction to the police killing of young Black men in Toronto (Lewis Reference Lewis1992).Footnote 1 Importantly, because civilian oversight must represent and respond to many different communities, increasing confidence (for all members of the public) in police oversight is a key challenge for the civilian model (Roach Reference Roach2014; De Angelis Reference De Angelis2016; Kwon and Wortley Reference Kwon and Wortley2020).

There are several variations of the civilian oversight model with respect to powers, process, and relationship with the police service; however, most can be labeled as either a civilian review model or a civilian control model. Civilian review includes models where investigations are completed internally by a police agency or by a neighbouring police agency, which is then reviewed by a civilian auditor (Ferdik, Rojek, and Alpert Reference Ferdik, Rojek and Alpert2013; Walker Reference Walker2001). In this model, consequences for credible complaints are often determined by the police agency, subject to review by the civilian auditor (Prenzler and Ronken Reference Prenzler and Ronken2001). One of the advantages of the civilian review model is that it is generally perceived as more legitimate by police officers, which can promote better cooperation with and response to investigations (Prenzler Reference Prenzler2011; Prenzler and Ronken Reference Prenzler and Ronken2001). From the public’s perception, the fact that this model relies on police investigating other police weakens its legitimacy and investigative independence. In Landau’s study of the Office of the Police Complaints Commissioner,Footnote 2 individuals who had participated in the complaints process were disappointed to learn that the investigations were handled by the police agency and viewed the process with cynicism (1996, 304). Recent work by Kwon and Wortley (Reference Kwon and Wortley2020) confirms that the public prefers complaints against the police to be handled by non-police investigators. Finally, Prenzler and Ronken (Reference Prenzler and Ronken2001, 165) suggest that the civilian review model is perhaps more symbolic than effective in providing control and oversight of police conduct.

Civilian control models can remedy many of the concerns relating to the civilian review model because they eschew the use of police agencies for investigations, which can avoid concerns regarding independence. The civilian control model does not rely on seconded police officers, nor does it permit former officers from the agency being investigated to participate in the investigations (Prenzler and Ronken Reference Prenzler and Ronken2001; Ferdik, Rojek, and Alpert Reference Ferdik, Rojek and Alpert2013; Walker Reference Walker2001). While there has been public criticism of employing former police officers by civilian oversight agencies, systemic reviews recognize the forensic and investigatory expertise held by former police officers and have not called for a complete ban on employing them (Tulloch Reference Tulloch2017; Prenzler Reference Prenzler2000).Footnote 3 Civilian control models will be most effective when they possess the necessary investigatory and disciplinary powers, and when the community views the agency as legitimate. Public legitimacy is promoted when the public understands the investigation process and when the agency engages in community outreach (Tulloch Reference Tulloch2017).

While the civilian control model is often considered the optimal model of police oversight, much of the existing literature is primarily normative in nature or is based on a qualitative review of agency powers and structure (Ferdik, Rojek, and Alpert Reference Ferdik, Rojek and Alpert2013; Prenzler and Ronken Reference Prenzler and Ronken2001; Harris Reference Harris2012; Prenzler Reference Prenzler2011). Little is known about individual cases and their disposition (Wortley Reference Wortley2007; Prenzler and Lewis Reference Prenzler and Lewis2005). In measuring the success of civilian oversight bodies, relying on case numbers and substantiation of complaints alone is not ideal because these rates can reflect a high rate of trust in organizations (whereby individuals are more likely to submit complaints) or a high rate of police misconduct—or both (Prenzler and Lewis Reference Prenzler and Lewis2005; Prenzler Reference Prenzler2000). Moreover, the investigations undertaken by civilian oversight bodies are quite difficult compared with routine police investigations, as there are often no witnesses outside of the complainant and the subject officer, and complaints vary widely in terms of quality.

Because some civilian oversight agencies have the power to lay criminal charges against police officers, their work is part of the broader legal oversight framework, which includes prosecution, judicial review, and other legal remedies. Canadian police officers and their investigations are subject to constitutional scrutiny through judicial review of various legal rights of the accused, including the exclusion of improperly obtained evidence, through the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, 1982 (Sossin Reference Sossin, Beare and Murray2007; Scott Reference Scott and Scott2014). In the civil context, litigation has been used both to compel police officers to cooperate with oversight agencies and to promote systemic change (Falconer and Daniel Reference Falconer, Daniel and Scott2014; Roach Reference Roach2014; Wood v. Schaeffer, 2013). Police owe a duty of care to the accused and victims in investigations and can be liable to lawsuit for a variety of matters, such as wrongful death and unlawful arrest (Doe v. Metropolitan Toronto (Municipality) Commissioners of Police, 1990; Hill v. Hamilton-Wentworth Regional Police Services Board, 2007). Legal methods of police oversight can provide complainants with access to remedies that can be both punitive and denunciatory; however, effective use of legal mechanisms often requires that complainants have the necessary financial and legal resources. Legal oversight is reactionary in nature and, importantly, many aspects of police activity do not result in criminal charges and even fewer result in a trial, which limits opportunities for constitutional litigation (Rowe and Lister Reference Rowe, Lister, Rowe and Lister2015).

Although there is no scholarship that examines the outcomes of criminal prosecution of the police in Canada, American scholarship highlights several important trends. Prosecutors are not only hesitant to pursue charges against the police, they frequently fail to do so (Levine Reference Levine2016b, Reference Levine2016c; Colbert Reference Colbert2016; Panwala Reference Panwala2003). One study found that of the thousands of incidents involving fatal police shootings between 2005 and 2015, just over fifty resulted in a charge or indictment (Levine Reference Levine2016c, 763). Of these cases, only the ones involving the most egregious acts of brutality, coupled with strong forensic and witness evidence, led to charges being laid (Levine Reference Levine2016c). At least in part, the low charging rate is reflective of the enhanced protections police suspects receive in the investigative process. Unlike Canada, in approximately twenty states, police officers are protected by Law Enforcement Officer Bills of Rights, legislation that provides police suspects with additional interrogation protections, extending well beyond the regular constitutional rights afforded the criminally accused (Levine and Rushin Reference Levine and Rushin2018). Officers who are prosecuted tend to receive preferential treatment in the trial process (Levine Reference Levine2016a). By virtue of working in law enforcement, police officers are typically viewed as inherently credible by judges and juries (Levine Reference Levine2016b; Freeman, Reference Freeman1996). In contrast, individuals who are the most vulnerable to police brutality commonly have a criminal record, mental health disability, and/or a history with addiction, characteristics which juries typically find to be untrustworthy (Freeman Reference Freeman1996, 725). For this reason, it is unsurprising that the majority of trials involving police result in acquittals (Colbert Reference Colbert2016, 186). The tendency to favour police officers in evaluations of credibility is important to consider when officers are accused of sexual assault, as successful prosecution of sexual assault often hinges on the credibility of the accused compared with the complainant (Taylor and Gassner Reference Taylor and Gassner2010). Officers who are convicted and sentenced generally receive less punitive sanctions than those received by members of the public (Freeman Reference Freeman1996; Levine Reference Levine2016a; Levine Reference Levine2019). Sentencing decisions reveal that judges are often sympathetic to police officers and impose less severe and non-custodial sentences, including for criminal acts that would result in years of imprisonment for a civilian (Freeman Reference Freeman1996; Levine Reference Levine2016a).

The legitimacy of civilian oversight of the police requires public knowledge of and confidence in the process and outcomes. In this paper, we aim to fill the gap in our understanding of police prosecution in Canada by examining the outcomes of investigations by Ontario’s SIU. Our analysis is not an assessment of the SIU per se. Instead, we are primarily concerned with understanding how the justice system responds when an officer is charged with a criminal offence. Created in 1990, the SIU is a civilian law enforcement agency. It does not employ active police officers and it holds the power to lay criminal charges against police officers across the province—approximately 23,000 officers from forty-seven different police services (SIU 2016). The SIU is tasked with investigating instances of police and civilian interactions resulting in serious injury, death, or allegations of sexual assault.Footnote 4 Most often, it investigates on-duty conduct, although it has jurisdiction over off-duty officers when the individual has identified themselves as an officer or invoked police powers, or when the incident involves police equipment or property (Special Investigations Act, 2019, s. 15(2)(b)). The SIU conducted an average of 302 investigations per year from 2005 to 2019. When an investigation is conducted, the SIU Director holds the authority to determine whether the complaint is substantiated, meaning it meets the evidentiary threshold to lay criminal charges (Special Investigations Act, 2019, s. 32). Once the SIU Director lays charges, the Attorney General of Ontario is responsible for prosecution. The SIU is considered a pioneer in civilian oversight, and similar agencies based on the SIU model have since been adopted in five Canadian provinces (Roach Reference Roach2014). The SIU has been subject to several government inquiries;Footnote 5 however, empirical and theoretically informed assessment has been limited (Roach Reference Roach2014). The systematic analyses that do exist are dated (Landau Reference Landau1996) and made in response to a particular incident (Wortley Reference Wortley2007) or are limited to one police force (OHRC 2018).

Methodology

To explore what happens after police officers are criminally charged by the SIU, our study contains all completed SIU investigations between January 1, 2005, and May 31, 2020, where complaints were substantiated. Although the SIU was established in 1990, it only began publishing internal statistics and press releases in 2005, making it a logical starting point for our study. Using this timeframe, our dataset consists of 159 incidents involving 180 charged officers. The vast majority of officers were the subject of one substantiated investigation; however, two officers were charged separately by the SIU twice, and two officers were charged by the SIU in three separate investigations.

Through a systematic examination of numerous sources of data, including SIU press releases, newspaper archives, and published legal decisions, we identified all cases where the SIU substantiated a criminal charge in all areas of its mandate.Footnote 6 Using SIU press releases allows us to be confident that we have captured the entire population of charged cases within this fifteen-year-period since the SIU always issues a press release when a charge is laid and will provide additional press releases in high profile cases, like the Forcillo case described in the introduction. Typically, a press release will contain information about the officer, the charge(s) being laid, contextual details such as the time and location of the incident, and some information about the complainant(s) and the nature of the injuries or wrongdoing suffered.Footnote 7

After locating the press releases, we used newspaper and legal databases to identify publicly available information about what happened after the SIU laid charges. From this, we were able to locate media coverage on the vast majority of cases and, in some instances, the legal decisions. Once we compiled all available data pertaining to a particular case, we conducted a content analysis on each collected document. The content analysis here was coded by hand, rather than by computer, and was completed by only one of the researchers. We deliberately opted for human coding because computers are less likely to identify and understand the ambiguities, nuances, and wider context surrounding a particular text (Benoit Reference Benoit, Bucy and Holbert2011, 275). Similarly, having only one coder allowed us to eliminate concerns regarding intercoder reliability. The key objective of the content analysis was to identify potential patterns between cases that are substantiated by the SIU and in the legal outcomes for police officers who are criminally prosecuted. For this reason, our coding scheme is comprised of several explanatory variables which catalogue a wide range of information relating to the prosecution of police officers: the incident that led to charges, information about the complainant and their conduct, the subject officer’s policing history, the existence and participation of any civilian or officer witnesses, and details pertaining to the prosecution and case outcome. Our analysis adopts the case categorization used by the SIU, which classifies occurrences as involving an injury, death, or sexual assault allegation. The SIU further specifies injuries and fatalities as resulting from either a vehicle accident, firearm, or a physical interaction involving the police, a categorization we adopt as well. In this way, rather than following the formal sections of the Criminal Code (such as assault causing bodily harm versus assault) to organize our cases, we follow the dispositions used by the SIU, which in turn, allows for our codebook to be mutually exclusive while still reflecting the organizational practice of the SIU.Footnote 8 This method enabled us to trace the process and experience of 143 charged officers within the legal process, including the final outcome of their cases.Footnote 9

Our analysis draws from three interrelated units of analysis: the individual, the incident, and the charge. In presenting our findings, we will begin by using the individual as the unit of analysis, to discuss the demographical and personal details of officers and complainants. From here, we shift towards using the incident as the unit of analysis, where we highlight the circumstances surrounding the underlying events of substantiated cases. Finally, when discussing the various case outcomes, including the procedural outcomes of charged officers, the unit of analysis is the charge(s) laid, because in several cases multiple charges were laid against the officer, occasionally resulting in different outcomes. Put another way, in some cases involving multiple charges against a single officer, the charges were partially withdrawn by the Crown. This focus allows us to effectively capture differences in cases that resulted in a conviction where one or more charges were withdrawn by the Crown. With this in mind, the number of cases reflected throughout our tables do not remain constant—it changes depending on the unit of analysis and because some cases had not completed the legal process at the time of data collection.

Data and Analysis

In the 159 incidents analyzed, the SIU substantiated criminal charges against police officers who are predominantly male (over 97 percent), at the rank of constable/detective (85 percent), with an average of 12.86 years of policing experience, and 16 officers had past Criminal Code and Police Act charges. Typically, the incident was conducted while on duty (86 percent). When we dissected our analysis by type of offence, there were some notable differences in the average profile of officers charged with sexual assault compared with the entire corpus of cases. Officers charged with sexual assault tend to hold a higher policing rank, nearly 30 percent hold the rank of sergeant or higher, and consequently, these officers have more years of policing experience, with the average years of service being 15.47 years. Sexual assault cases frequently occur off duty (44.4 percent), and a quarter of the officers charged had prior charges, often for similar conduct.

Complainants in the SIU investigations are frequently male (63 percent) and under the age of 40 (64 percent), with the greatest proportion being individuals in their twenties. Complainants were noted as having a criminal record in a minority of cases (almost 18 percent), though it is possible that this detail about the complainant is underreported. In 41.5 percent of incidents, complainants were described as engaging in criminal activity, and in almost 30 percent of cases, resisting arrest, while almost 29 percent of complainants were noted as fleeing arrest or being violent towards the police. Less commonly, complainants were characterized as intoxicated (16 percent), and only rarely were complainants reported to be brandishing or using a weapon. In 6.3 percent of incidents, the complainant was described as having a general or suicidal mental health disability. Our analysis attempted to examine the race of the complainant; however, the SIU did not collect or publish race-based data until June 2020, and race was therefore only mentioned in one press release. We identified acute differences when isolating for complainants of sexual assault. In nearly half of these cases, the age of the complainant was unidentified because of privacy restrictions; however, for the complainants whose age we could identify (22 cases), all were under the age of fifty, with 73.9 percent being under the age of thirty, and 93.8 percent were female. Both of these findings are consistent with wider research on sexual assault in Canada, which has found that women are more likely to experience and report sexual assault, and in particular, the rate is considerably high for women aged fifteen to twenty-four (Conroy and Cotter Reference Conroy and Cotter2017).

The Nature of Charges and Substantiated Incidents

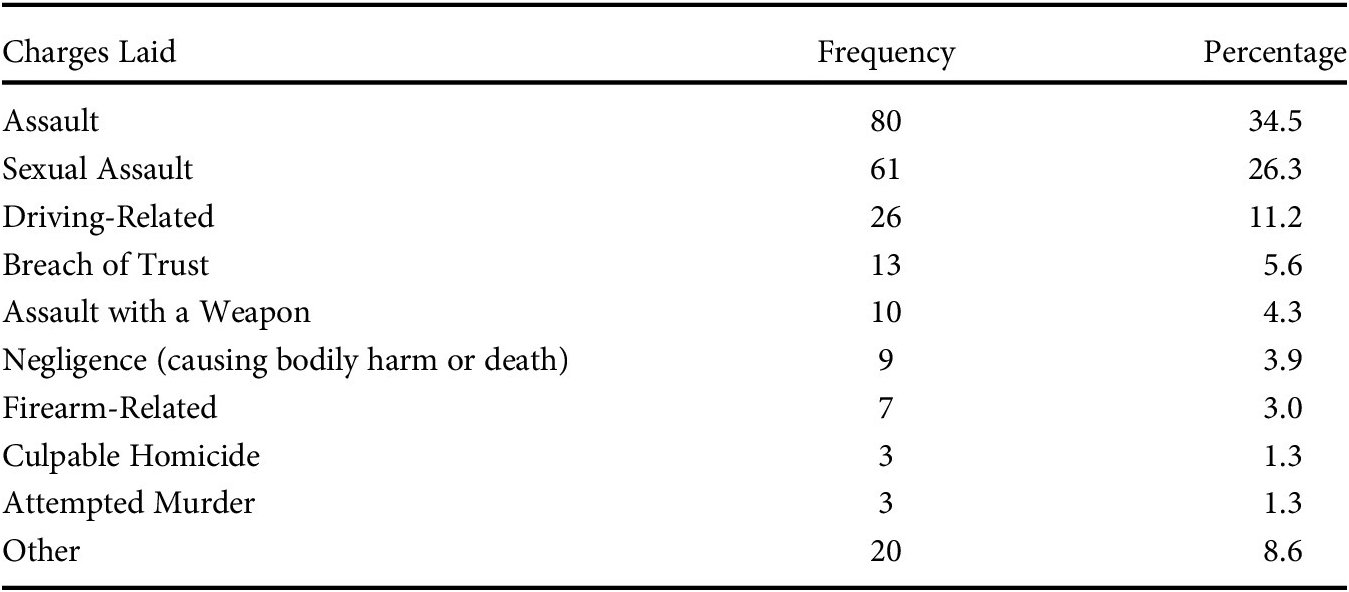

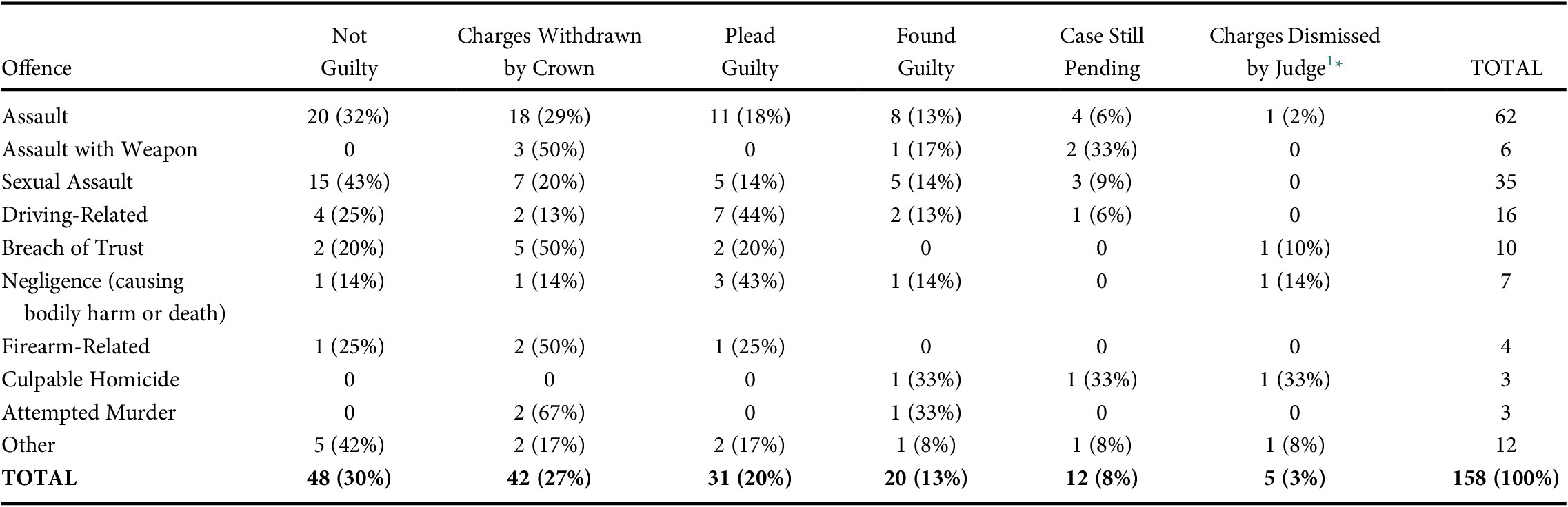

Special Investigations Unit investigations most often result in a single criminal charge, though in approximately one-third of cases, multiple criminal charges were laid. The most common charge laid by the SIU is assault (Table 1). Section 25(1) of the Criminal Code provides that police officers are justified to use as much force as necessary in the execution of their duty. Police use of force is not unlimited. Rather, it is restricted within the confines of what is reasonable for the particular situation at hand. The SIU is guided by legislation and Supreme Court of Canada rulings to make determinations on whether an officer has acted within the bounds of section 25(1). When the SIU charges an officer with assault, it has been determined that the officer has exceeded the amount of force that is proportionate to the circumstances and necessary for making a lawful arrest, keeping the peace, or to perform any other authorized police duties.

Table 1 Nature of Charges (Unit of Analysis: Charge)

In more than 90 percent of cases where police officers are charged with assault, the underlying incident occurs on duty, and typically while the officer is responding to a call for service. For example, in 2016, a sergeant with the Niagara Regional Police was dispatched to a drugstore to investigate an alleged assault. Within a minute of arriving at the scene, the officer attempted to arrest the complainant, and CCTV footage recorded the officer shoving the complainant into a fence. Reviewing the officer’s conduct, the presiding judge noted, “the most apt description of [the complainant] without meaning any disrespect, is that he looks like a rag doll” (R v. Baxter, 2018, para. 43). From this incident, the officer was charged by the SIU for assault causing bodily harm. The SIU determined that the use of force was excessive and beyond what was necessary to conduct the arrest. Other substantiated assault cases commonly arise from calls for service to domestic disputes, as well as in the context of conducting traffic stops. In contrast, the SIU has rarely laid charges for assaults that occur while off duty and has only done so four times, including the highly publicized case of Toronto police officer Michael Theriault (Gillis Reference Gillis2020).

Sexual assault is the second most common offence for which officers are prosecuted (Table 1). The context surrounding these incidents is much more varied than in the use of force cases. Sexual assaults occur on duty and off duty at an almost equal frequency. On-duty incidents frequently occur in police vehicles. For example, a former York Regional Police officer was charged in two separate SIU investigations (and eventually convicted) for sexual assaults that were committed during traffic stops. In one incident in 2015, the officer pulled over the complainant and forced her into the rear of his police vehicle where the officer assaulted the complainant and exposed himself. Similarly, in 2004, a Niagara Regional Police officer performed a breathalyzer test and the complainant was found to have a small trace of alcohol. The officer then coerced the complainant into performing oral sex on him in exchange for not laying charges. Other on-duty sexual assaults have occurred while arresting and transporting women who are in custody, as well as when attending to calls for service from the complainant.

The SIU has also charged a number of officers for sexual assaults committed while off duty (44.4 percent). In these cases, 21.7 percent of the complainants are under the age of nineteen, and the assaults frequently occur inside the complainant and/or the officer’s home. In these cases, the officer is usually also charged with breach of trust. Off-duty officers have also sexually assaulted individuals they previously assisted while on duty. For instance, in 2010, an Ontario Provincial Police constable assisted a teenage girl who was experiencing domestic violence. While off duty, the officer invited the girl and her friend to his home, where he allegedly gave them alcohol and sexually assaulted them.

Following assault and sexual assault, driving-related incidents are the most common charges against Ontario police officers. Police officers have only been charged for on-duty driving incidents, ranging from accidents that have caused serious injury to, far less frequently, ones that resulted in fatalities.Footnote 10 In fact, during the period of our study, the SIU only charged officers on five occasions for fatal driving-related incidents. In both fatal and non-fatal cases, the collisions are most commonly the result of a police pursuit. In some instances, the police pursuit leads to bystanders being struck by either the police vehicle or the suspect’s vehicle. In other cases, police pursuits have caused major vehicle collisions between the police, suspect, and other vehicles.

Outside of incidents involving vehicles, the SIU has very rarely laid charges for police interactions resulting in the death or near-death of a member of the public. In fact, only eight officers have been prosecuted for charges ranging from attempted murder to criminal negligence causing death, failing to provide the necessaries of life, manslaughter, and second-degree murder. All of these cases occurred while the officer was on duty, and in half of them, officers discharged their firearm, resulting in two fatalities and two life-threatening injuries. In other incidents, police officers have been charged for inaction in fatal situations. For example, in 2016, a Toronto police constable failed to act on a call he received about a man who was in the process of completing suicide in a public park. That same year, two London officers were charged for failing to get timely medical help for an Indigenous woman who died while in police custody. Although these cases are rare, they tend to receive significant media coverage, shaping how the public ultimately perceives the legitimacy of SIU investigations.

The Nature of Prosecution and the Crown

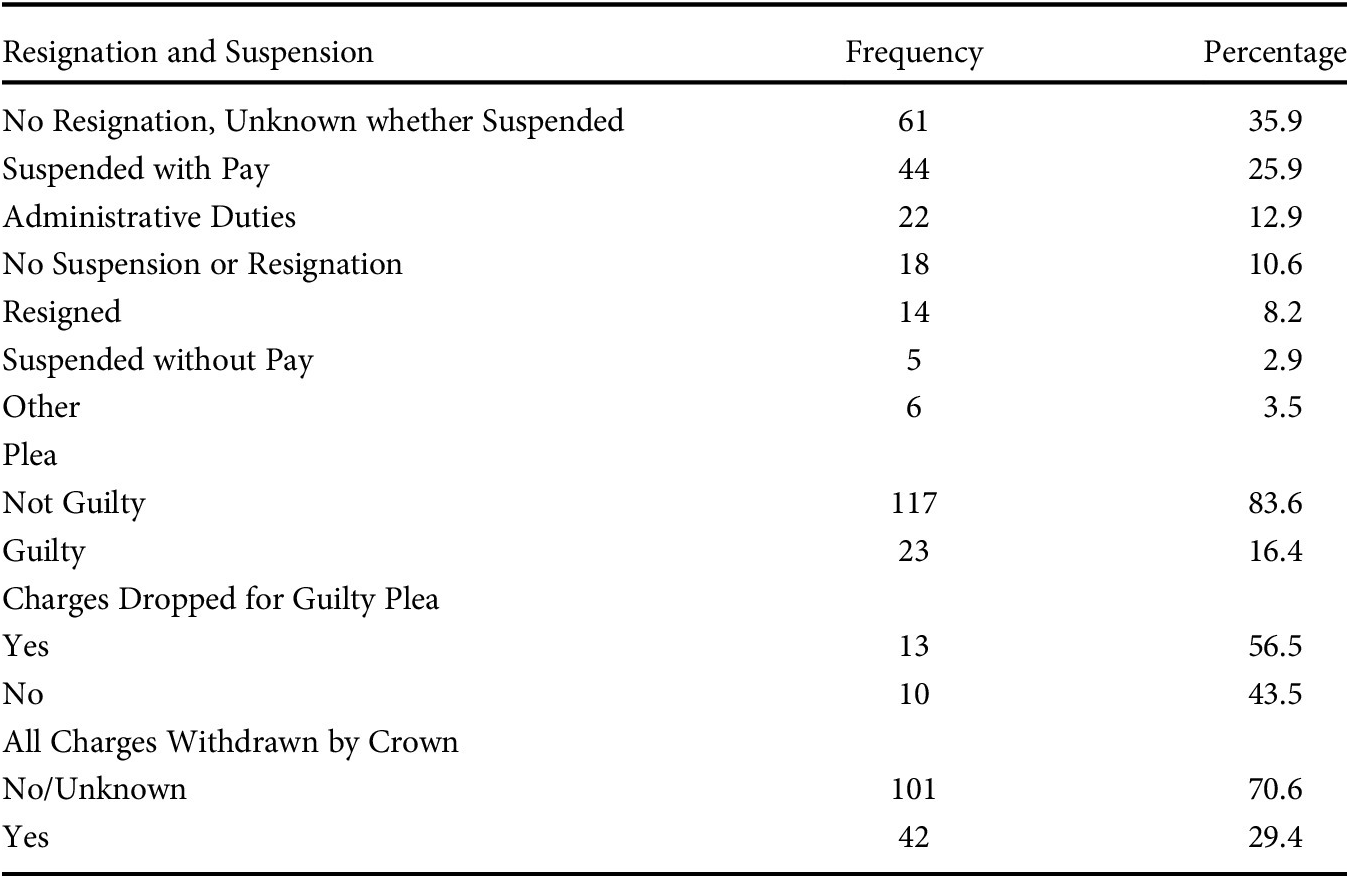

After a police officer is charged by the SIU, the chief of police has the authority to suspend the officer with pay, to reassign them to “desk duty,” or to allow the officer to continue working in their usual capacity. Under the Police Services Act, police officers cannot be suspended without pay until they are convicted of an offence and sentenced to a term of imprisonment (section 89(6)). As seen in Table 2, officers are commonly suspended with pay while awaiting trial. However, almost a quarter of officers are either assigned to administrative duties (12.9 percent) or remain serving in their normal role (10.6 percent). Although rare (8.2 percent), officers have resigned after being charged and/or convicted of a serious offence, such as homicide.

Table 2 Procedures after Being Charged (Unit of Analysis: Subject Officer)

Prosecuting police officers has its own unique set of circumstances when compared with prosecuting other members of the public. While a vast majority of criminal charges in Canada are resolved through a guilty plea (Euvrard and Leclerc Reference Euvrard and Leclerc2017), it is far less common, as Table 2 demonstrates, for officers to plead guilty (16.4 percent). This might explain why nearly 30 percent of charges against officers are withdrawn by the Crown before trial. In part, the high rate of withdrawal could signify the difficulty of prosecuting cases involving the police. There are often no independent witnesses, and sometimes, there is a lack of forensic or video evidence, making it difficult for prosecutors to meet the high evidentiary burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Nonetheless, because the Crown does not need to publicly justify why it chooses to withdraw charges, this practice might fuel public distrust in the police, the legal process, and the wider criminal justice system, highlighting the impact of prosecutorial discretion.

Case and Sentencing Outcomes

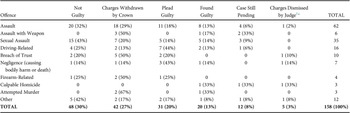

Officers are acquitted in 30 percent of cases. As Table 3 illustrates, acquittals are especially frequent in incidents involving sexual assault. In these cases, judges often credit their finding of not guilty to issues relating to the complainant’s credibility. For example, a former Ontario Provincial Police officer was acquitted of sexual assault for an off-duty incident in which he allegedly forced a woman to perform oral sex. In registering the acquittal, the judge emphasized serious concerns with the credibility of the complainant due to her conduct during the SIU investigation, including contacting potential witnesses after being specifically instructed by the SIU not to do so (R. v. Girard, 2016, para. 31). In acquitting an officer of sexual assault, judges also tend to cite a lack of supporting evidence, such as audio or video recordings and eyewitness accounts.

Table 3 Case Outcome by Charge (Unit of Analysis: Charge)

* This includes instances where judges did not commit charges to trial following a preliminary hearing.

By a small margin, acquittals are the most common outcome in assault cases (Table 3). Similar to sexual assault, part of the judges’ reasoning hinges on the credibility of the complainant and key witnesses, as well as a lack of supporting evidence. However, as described earlier, in 41.5 percent of substantiated incidents, the complainant was in the process of committing a criminal offence, and in 29.6 percent of cases, they were resisting arrest; such factors can inform the judge’s decision to acquit. For instance, a Peel Police constable was acquitted of assault in a case where the complainant was injured in the process of being arrested for public intoxication. The judge noted that because the complainant was intoxicated, the officer and his partner had reasonable grounds “to believe that there was a risk to the [complainant’s] safety or somebody else’s safety” (R. v. Furlotte, 2012, para. 116). For this reason, the judge concluded that the officer had reasonable grounds to arrest the complainant and the force used was appropriate (Furlotte, para. 119).

In comparison, the majority of driving-related incidents result in a guilty plea or a finding of guilt. In cases involving a guilty plea, the officer either pleads guilty before the case goes to trial, or less commonly, like any other accused, the officer might change their plea to guilty after the trial has commenced. Cases that result in a finding of guilt always follow a completed trial that has been heard by either a judge or jury (though, jury trials only occurred in 4.3 percent of cases). Driving-related incidents likely see a higher rate of guilty pleas when than sexual assault or assault because the sentence upon conviction may be less punitive and physical evidence is often easier to obtain, serving to increase the likelihood of successful prosecution. Knowing this, there is likely an incentive for officers to plead guilty in exchange for a desirable sentencing recommendation.

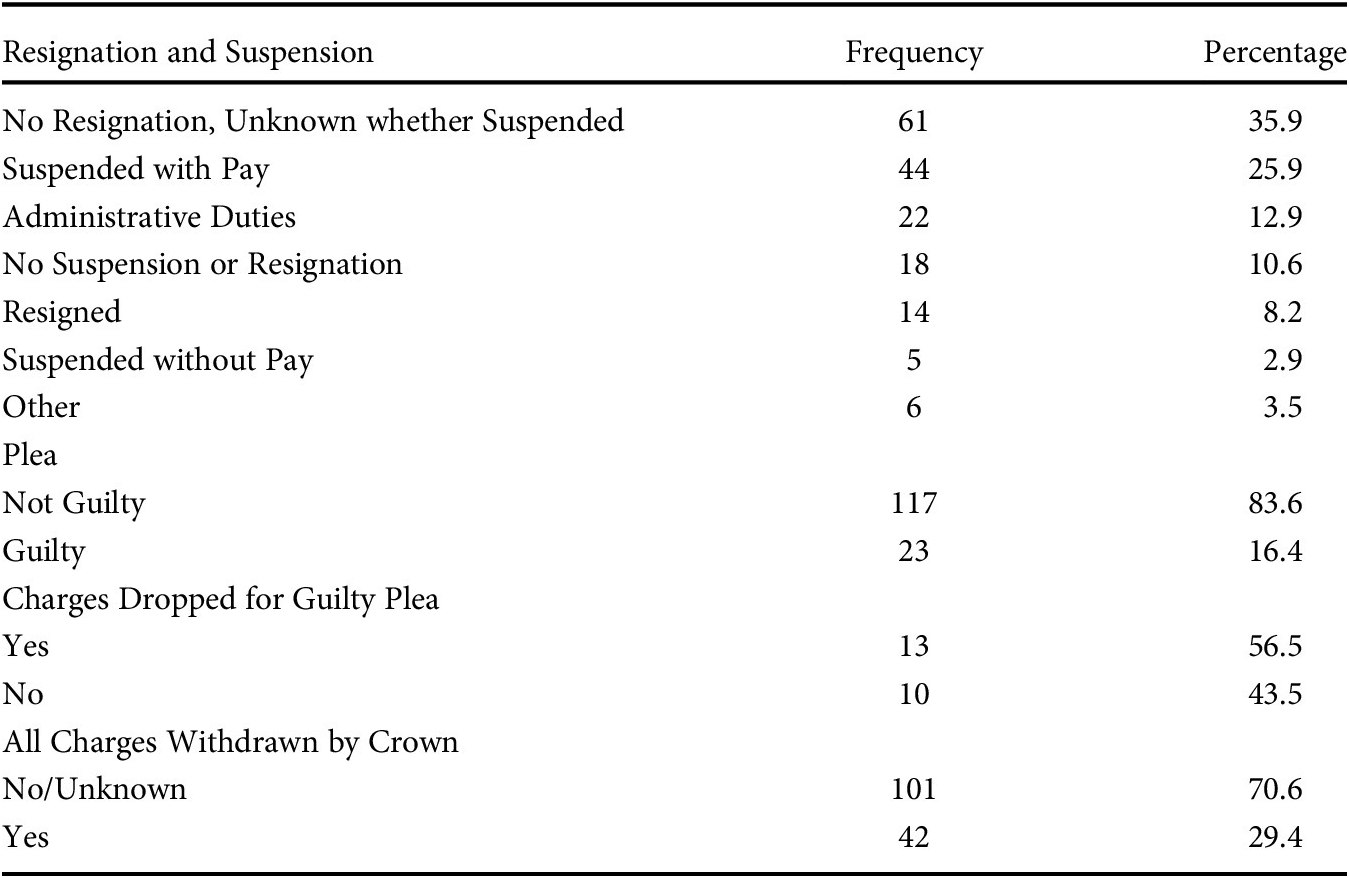

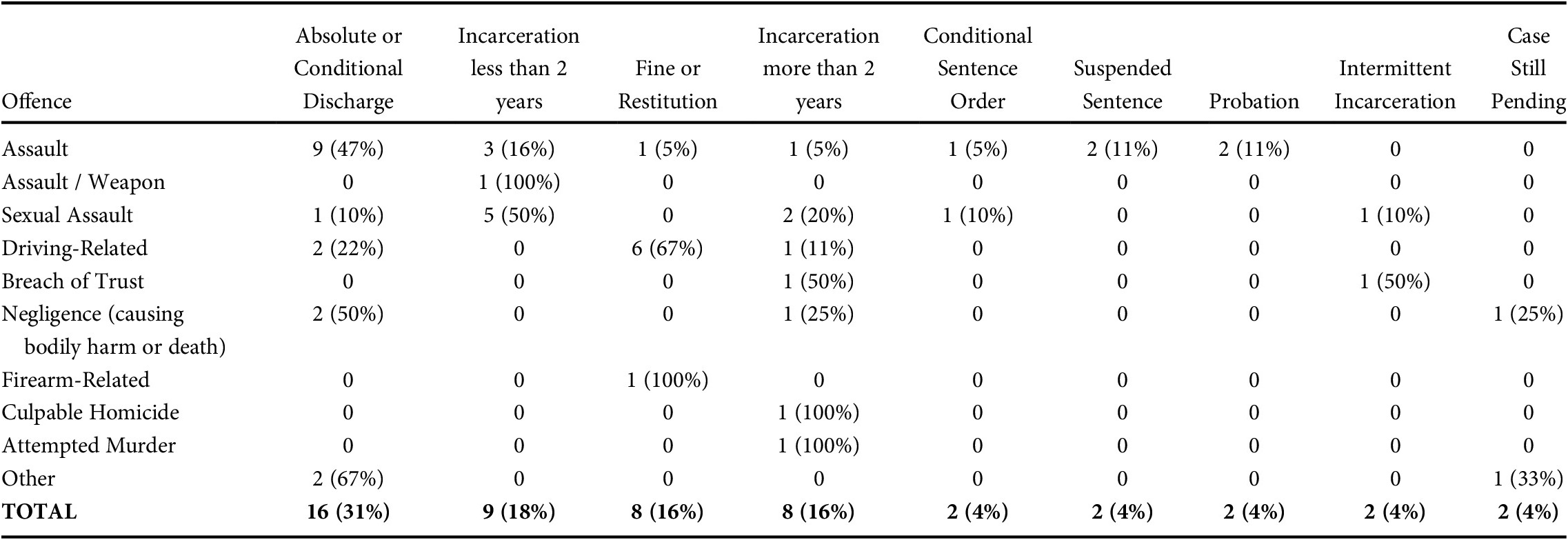

Sentencing is largely an individualistic process, where judges determine an appropriate sanction by assessing the moral culpability of an offender and by weighing any mitigating or aggravating circumstances. Although there is some overlap between the types of considerations judges make in sentencing other members of the general public and those made in the case of the police, such as whether the individual is a first-time offender, there are a number of aggravating and mitigating circumstances unique to sentencing police officers. As shown in Table 4, the majority of sentences handed down by judges are absolute and conditional discharges, the least restrictive sanctions available. This trend is quite salient in assault cases, where officers are given a discharge in nearly half of all sentencing decisions. In cases that result in a discharge, the judge typically draws on a police officer’s past policing record to serve as justification for leniency and judicial restraint. For instance, in sentencing a police officer convicted of assault for breaking the ribs of a man he arrested, the judge emphasized the following:

[the officer] comes to the court prior to this incident with an impressive record. He is one of those people who has done a lot for the rest of us. He has an exemplary background. He uses his time to coach others, to assist others. He is a true hero in one sense for the event where he saved two little girls from drowning and he can use that record today as kind of a bank account. He can draw on it. […] As I look at all of this before me, […] it was a momentary action done in anger and frustration. […] We are not talking about a Rodney King situation. (R. v. Hutchison, 2009, para. 11)

Table 4 Sentencing Outcome by Charge/Conviction (Unit of Analysis- Charge)

The judge suggests that when a police officer has a clean record and a history of helping in the community, they are entitled to use these deeds as a metaphorical “bank account,” exchanging past good behaviour for leniency in sentencing. While judges consider mitigating factors for all offenders, given the nature of police work, there can be ample opportunity for convicted officers to introduce evidence of positive contributions to the community to decrease the severity of the sentence. Moreover, in the case above, the judge justifies imposing an absolute discharge by characterizing the offence as “a momentary action done in anger and frustration,” implying that because the assault did not reach the level of police brutality as in the “Rodney King situation,” it warranted a less severe sanction. In several other cases, judges mitigate an officer’s sentence by finding the officer was provoked to some extent by the conduct of the complainant.

In contrast, custodial sentences of any length (including terms of intermittent incarceration) were imposed in approximately one-third of all cases (Table 4). In these cases, the aggravating factors tend to severely outweigh any mitigation. Perhaps most illustrative is the sentencing of former Toronto police constable James Forcillo for the killing of Sammy Yatim. In sentencing the officer to six years of imprisonment, the judge highlighted that the officer grossly failed in his fundamental duties as a police officer by violating the principle to preserve all life and failing to use deadly force as only a last resort (R. v. Forcillo, 2016, para. 52). The judge highlighted that Forcillo did not follow his police training in de-escalation or on the proper use of his firearm (Forcillo, para. 53), noting that the officer had a lengthy history of drawing his firearm on citizens (Forcillo, para. 62). Additionally, section 718.2(a)(iii) of the Criminal Code instructs judges to consider “evidence that the offender, in committing the offence, abused a position of trust or authority in relation to the victim,” as aggravating. When sentencing Forcillo, the judge noted that the case was most aggravated by constituting an “egregious breach of trust” (Forcillo, para. 92).

Similarly, breach of trust was commonly cited as an aggravating factor in the sentencing decisions for sexual assault cases. In part, this helps to explain that, although police officers are rarely convicted of sexual assault, their sentencing outcomes tend to be more punitive when compared with other offences. In fact, 80 percent of officers convicted of sexual assault are sentenced to a period of imprisonment. To demonstrate, in one sentencing decision involving a former police officer convicted of sexually assaulting a teenage girl, the judge articulated that, because police officers hold a position of trust in society, more punitive sentencing outcomes are required:

Given the privilege (sic) position occupied by police officers and the trust that the community bestows upon them, our courts have generally found that officers are to be treated more severely than ordinary citizens. Although the offences were not committed while Mr. Christiansen was on active duty, I find that he used his position as a police officer to facilitate a relationship with [the complainant]. (R. v. Christiansen, 2019, para. 47)

In this case, the officer was sentenced to thirty months’ imprisonment, making it one of the most punitive sentencing outcomes in our entire dataset. On the other end of the spectrum, in nearly 90 percent of driving-related cases, the officer was sentenced to a non-custodial sanction. Most officers convicted of driving-related offences were ordered to pay a fine or restitution and, less commonly, were sentenced to a conditional or absolute discharge. Only one case resulted in a sentence of incarceration. Recall earlier that officers charged with driving-related offences were the most likely to plead guilty. These findings combined may signal that driving-related cases are frequently resolved through plea bargaining, resulting in lenient sentencing outcomes.

Discussion and Conclusion

Although there is a growing body of American literature on the prosecution of police officers, there is no such scholarship in Canada. For civilian oversight of the police to be effective and legitimate, there must be public knowledge of and trust in the process. Yet in Ontario, where the civilian oversight body is frequently considered the ideal model, little is known about the process by which police officers are investigated, and the consequences and outcomes when charges are laid. This paper sought to rectify this gap through a systematic analysis of legal outcomes for police officers charged by the SIU between 2005 and 2020. It was found that in over 25 percent of cases, charges against the police are withdrawn by the Crown. For the cases which do proceed to trial, the most common outcome is an acquittal; and for officers who are convicted, they are typically sentenced to a conditional or absolute discharge. These legal outcomes are unique when compared with the prosecution of members of the general public. For instance, we found that 33 percent of charged officers were convicted, a figure which is significantly lower than the 56 percent overall rate of guilt for Ontarians tried within the same period of time (Statistics Canada 2020b). There are also notable differences in the sentencing outcomes of police officers. Officers tend to be sentenced less punitively for assault and driving-related offences and are more likely to receive non-custodial sentences than are the general public.

What can account for these differences? Unlike in the United States, Canada does not have bills of rights specifically for police officers. Similar to any other person under criminal investigation, Canadian police officers are afforded legal protections under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. For this reason, police officers under investigation do not have to submit their notes to the SIU; nor do they have to participate in an interview.Footnote 11 While the general public is also entitled to exercise their legal rights, police officers are inherently advantaged by their status as criminal justice insiders. Understanding Charter legal rights is central to the daily duties of police officers, making them well-positioned to protect their rights at all stages of the legal process compared with the average person. Additionally, prosecuted police officers have extra layers of support when compared with the average person charged with an offence. Police officers enjoy support from policing unions, who not only advocate and lobby for the due process interests of police officers as a population, but can also provide support to individually charged officers (Ferdik, Rojek, and Alpert, Reference Ferdik, Rojek and Alpert2013). Police officers also tend to have access to effective counsel. In our study, we found that there were ten high-profile criminal defence lawyers who were repeat players specializing in cases involving police accused; they represented the vast majority of officers charged by the SIU.

Even with all additional supports removed, police officers would likely still be advantaged in the criminal justice process, particularly in cases involving sexual assault. Sexual assault is the most underreported violent crime (Conroy and Cotter Reference Conroy and Cotter2017), and in 2014, only 5 percent of sexual assaults against people over the age of fifteen were reported to the police (Rotenberg Reference Rotenberg2017). The rate of reporting has steadily declined over the past two decades, with the exception of moderate increases following the #MeToo movement (Rotenberg and Cotter Reference Rotenberg and Cotter2018). Factors such as internalized feelings of shame and guilt, the perception of not being believed or treated respectfully by various actors in the criminal justice system, and a lack of confidence in the possibility of conviction all serve as impediments to reporting (Fisher et al. Reference Fisher, Daigle, Cullen and Turner2003; Taylor and Gassner Reference Taylor and Gassner2010; Johnson Reference Johnson and Sheehy2012). Understandably, this reluctance to report is likely more pronounced in cases involving police officers. Rowe and Lister (Reference Rowe, Lister, Rowe and Lister2015) note that integral to police culture is the “blue wall of silence,” the idea that police officers follow an informal code to protect one another from professional or even criminal consequences. Furthermore, recall that police officers are generally privileged in assessments of credibility compared with complainants, a fact that undoubtedly impacts the investigation and prosecution of officers accused of sexual assault. Within this context, people who are sexually assaulted by the police could reasonably perceive that reporting will not lead to charges being pursued, and instead, could result in serious repercussions or stigma in future interactions with the police.

Even when sexual assault charges are laid by the SIU, the Crown withdraws charges in 20 percent of cases, and judges and jury acquit 43 percent of the time. While withdrawn charges and acquittals are not unique to sexual assaults involving police, the guilty rate is nearly 15 percent lower than that of the general Canadian population (Statistics Canada 2020a). In part, this may be explained by the difficulty of obtaining reliable evidence to substantiate sexual assault complaints in cases involving police officers. For instance, it is unusual for these cases to have independent witnesses or to have forensic and video evidence. In some cases, reports were not made to the SIU until decades later, exacerbating evidentiary limitations even further.

Interestingly, although it is more likely for the general public to be found guilty of sexual assault, we found that convicted police officers tend to be sentenced more punitively. Police officers in our study were 29 percent more likely to be given a custodial sentence when compared with all Ontarians convicted of sexual assault during the same period (Statistics Canada 2020c). Considering the high rate of attrition for cases of sexual assault, severity in sentencing might reflect that the cases which make it to the sentencing stage have the most clear-cut incidents of abuse supported by compelling evidence. Furthermore, convicted officers are sentenced more harshly because they are typically co-charged with breach of trust, which judges consider to be extremely aggravating.

The sentencing discussions examined in this study demonstrate that in weighing mitigation and aggravation, judges tend to focus on three factors: the nature of police work and training, the nature of the offence committed, and the public response. Judges have noted that, while police work is high-risk, this fact alone is not necessarily mitigating because officers are trained to respond to danger and provocation. Relying on guidance from the Supreme Court in R v. Nasogaluak, judges at sentencing and the SIU when laying charges make clear that an officer’s actions should be reviewed with some latitude and not against a standard of perfection (2010, para. 35). This latitude is balanced with an appreciation that officers have considerable knowledge of the justice system and an understanding that their actions will be subject to greater scrutiny than a non-police officer’s (R v. Sandhu, 2015; R v. Heard, 2018).

Here, we find a divergence between the Canadian and American approaches to dealing with police offenders accused and convicted of criminal offences. While several American jurisdictions provide enhanced rights protection for police officers and studies of the American process find that police officers receive less punitive sentences than non-police officers (Freeman Reference Freeman1996; Levine Reference Levine2016a; Levine Reference Levine2019), this is not the case in Ontario. Instead, because of their knowledge and experience, judges have found the culpability and moral blameworthiness of officers to be quite high, requiring a more severe sentence, especially when a firearm is used (R v. Forcillo, 2016). In a similar vein, the officer’s actions are strongly aggravating when they are not in accordance with training or policy (Forcillo, 2016). That said, judges are sensitive to the collateral consequences unique to convicted officers that can mitigate the sentence, such as loss of employment and professional conduct charges under the Police Services Act. Sentencing judges also consider that custodial sentences for former police officers are likely to be served in solitary confinement or protective custody. Moreover, we found that across the sentencing decisions, many officers are noted to have impressive records of community service (unrelated to the offence at hand) that can demonstrate good character and provide mitigation of the sentence (for example in R v. Hutchison, 2009; R v. Thomas, 2012; and R v. Andalib-Goortani, 2015).

One of the unique challenges in sentencing a police officer for an offence committed while on duty, is the fact that some offences only arise because the complainant was engaged in criminal activity or activity that warranted police attention. Though judges do not use this fact to explicitly mitigate the sentence, the criminal activity and record of the complainant appear to influence judicial reasoning and are occasionally juxtaposed with the service record of the offender. For example, in sentencing an officer for assault, the judge in R v. Hutchison reminded the complainant (the victim of the assault) that he “is largely responsible for […] why this whole event happened. What happened to him on that night is his responsibility” (2009, para 10). Comparatively, in the case of offences where the officer abused their position and authority to commit the act, like a sexual assault, courts view the conduct much more harshly. Officers committing such crimes have done so in violation of police policy and practice and are often charged with an additional criminal offence of breach of trust in section 122 of the Criminal Code. As noted above, such instances are viewed as aggravating and call for a more severe sanction compared with cases involving non-officer offenders (R v. Christiansen, 2019). In these cases, judges will prioritize the goals of denunciation and deterrence in sentencing because these principles increase the severity of sentencing and send a message to the public.

Judges are sensitive to the impact that sentencing a police officer for a criminal offence can have on the public’s perception of, and confidence in, the justice system. While public confidence in the justice system is routinely considered by judges in sentencing, it is a greater concern when the offender is a police officer. Criminal activities committed by police officers undermine the trust and respect for law enforcement that are integral to effective policing, and the public will be attentive to differential treatment of officers, real or perceived (R v. Zarafonitis, 2013). That said, some judges consider the heightened public attention to police offenders, especially in smaller communities, and consider this a mitigating factor (Christiansen, 2019). Public confidence in the process and outcomes of police oversight is a noted challenge for civilian oversight in general and it is a particular challenge when considering the diverse range of communities and competing interests to which police oversight must respond (Tulloch Reference Tulloch2017). The emphasis placed on deterrence and denunciation when sentencing officers as it relates to public confidence demonstrates that justice system actors are sensitive to these concerns. However, we did not find evidence that justice system actors explicitly considered how concerns of public confidence might intersect with other issues such as gender-based violence, race, and systemic discrimination.

In considering the broader context of police oversight and accountability, public confidence and trust in the process should be a key focus when responding to officers charged and convicted of criminal offences. The public cannot have trust in a process that suffers from a lack of transparency. While there are difficulties in making direct comparisons between how the justice system responds to the criminality of police officers and that of non-officers, there is value in understanding the extent and nature of that response. By tracking the prosecution, conviction, and sentencing of cases, this paper moves beyond the rate of substantiation by the oversight agency. Importantly, substantiation rates alone do not detail how the justice system responds to cases of criminal conduct by police officers; rather, they are largely an indication of the volume and quality of complaints sent to the oversight agency (Prenzler and Lewis Reference Prenzler and Lewis2005; Prenzler Reference Prenzler2000). In tracing charges laid by the SIU to the prosecution, conviction, and sentencing, the data detailed here provides a variety of indicators of how the civilian oversight system in Ontario functions. The investigation and prosecution of criminal activity committed by police officers present a wide range of unique challenges; however, our research suggests that, in some cases, there can be significant consequences for officers brought to bear by civilian and legal oversight mechanisms.

This study uncovers previously unknown aspects of civilian and legal oversight mechanisms, providing insight regarding the performance of the system, with the goal of increasing public knowledge about the oversight system and its outcomes (Filstad and Gottschalk Reference Filstad and Gottschalk2011). Public understanding of the oversight system is essential to foster trust and to increase confidence in the system’s legitimacy. Public perception of police oversight has been primarily concerned with bottom-line outcomes—exclusively focusing on conviction and sentencing, without an appreciation for the process, evidence, and greater context relevant to the case. However, there is an indication that public interest in and scrutiny of policing practices and civilian oversight may be increasing. For example, recently in a rare livestreamed proceeding, over 20,000 people watched a judgement rendered in an Ontario case of an assault committed by an off-duty police officer (Hasham Reference Hasham2020). This public access allowed viewers to assess the process, including the work of the SIU and the legal system as they unfolded in this particular case. This study provides an empirical record to enhance this growing public conversation, as greater public attention is vitally important for the functioning of police oversight and public confidence in the process.