When tens of thousands of citizens filled the streets of Russian cities to protest fraudulent parliamentary elections in December 2011, the hopes for resurging civic engagement and imminent democratic change were high. After some first concessions, however, high expectations gave way to frustration. The regime stepped up its repressive response (Gel’man Reference Gel’man2015) and orchestrated a broad legislative and discursive backlash (Laruelle Reference Laruelle2013; Smyth, Sobolev, and Soboleva Reference Smyth, Sobolev and Soboleva2013). Meanwhile, the “For Fair Elections” (FFE) movement fractured: numerous leaders and activists emigrated, others undertook fruitless attempts at entering the tightly controlled political arena (Lasnier Reference Lasnier2018), and many simply retracted from the public sphere.

I set aside these normative perspectives—the enthusiasm and the frustration—and assess their empirical implications for local activism, asking under what conditions nation-wide protests in an electoral authoritarian setting can produce new local activist organizations. While classical social movement scholarship assumes that protest cycles produce new organizations (McAdam Reference McAdam1999) that can form the backbone of renewed mobilization (Taylor Reference Taylor1989), Robertson (Reference Robertson2011) argues that in hybrid regimes, there may be much protest without accompanying civil society growth. The specific conditions under which protest does lead to organization building in authoritarian regimes, meanwhile, are highly under-theorized (Lasnier Reference Lasnier2017).

Drawing on sixty-five semi-structured interviews, over a thousand media reports, and over one hundred internal documents and social media posts, I trace the organization-building process during the Russian “For Fair Elections” (FFE) protests of 2011–2012 across four subnational cases, proposing a novel argument that proceeds in three steps: First, in the years preceding the onset of a wave of mass protest, local activists develop distinct repertoires (Tilly Reference Tilly2008; Clemens Reference Clemens1997), the shape of which depends on activists’ local political conditions. More open, more resourceful, and less repressive political climates tend to generate broader tactical and more inclusive organizational repertoires than do less pluralist, less resourceful, and more repressive contexts. Second, where established activists perceive an opportunity to employ the erupting mobilization for their local struggles, this increases the likelihood that mass protests produce new local social movement organizations (SMOs). Third, how the new SMOs are structured depends on the repertoires from earlier episodes of contention that established activists use as templates for their organizational choices.

The argument speaks to several strands of literature. First, it illuminates within-country differences in opposition action and the functioning of modern authoritarian regimes (Giraudy, Moncada, and Snyder Reference Giraudy, Moncada, Snyder, Giraudy, Moncada and Snyder2019). Second, it contributes to the underdeveloped research program on protest institutionalization in non-democratic settings (Lasnier Reference Lasnier2017), highlighting the importance of varieties of authoritarianism (e.g., Howard and Roessler Reference Howard and Roessler2006) for social movement theory. Third, by substantiating the research agenda that understands protests as critical junctures (Blee Reference Blee2012; della Porta Reference della Porta2018), it provides an interactive model of structure and agency (Fligstein and McAdam Reference Fligstein and McAdam2011).

There are three reasons why the Russian case is well suited to yield results of more general relevance. First, it is an exemplary case of an electoral authoritarian system, in which national elections are controlled to an extent that precludes any real uncertainty (Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010), but nevertheless produce “focal points” (Tucker Reference Tucker2007) for opposition to mobilize around. Second, the FFE protests, though not successful at bringing about democratic change, share many other attributes with “urban civic revolutions” (Beissinger Reference Beissinger2013): They were triggered by fraudulent parliamentary elections, they proceeded mainly in urban spaces, and they brought together citizens with great ideological differences, pressing demands for free and fair elections without articulating a specific political program or social vision (see also Bunce and Wolchik Reference Bunce and Wolchik2010). Finally, Russia displays large structural variations on the subnational level that amount to the difference between competitive and hegemonic authoritarian regimes (Libman Reference Libman2017; Ross and Panov Reference Ross and Panov2019). Leveraging this within-country variation allows for a comparison of cross-nationally meaningful structural differences while simultaneously controlling for factors that confound cross-country comparisons.

Diffusion and Institutionalization of Protest

Resource Mobilization Theory (RMT) has long argued that SMOs are important for protest mobilization, because they are “bundlers and spenders” of resources like finances, connections, and knowledge (Earl Reference Earl2015; see also McAdam Reference McAdam1986; Greene Reference Greene2013). Moreover, RMT has convincingly shown that organizations are vital to uphold a movement in times of low societal mobilization through conserving frames, identities, and tactics (Taylor Reference Taylor1989; Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1998; see also Earl Reference Earl2015).

The empirical record on the reverse—the impact of protest on organization building—so far is inconclusive (Soule and Roggeband Reference Soule, Roggeband, Snow, Soule, Kriesi and McCammon2018). On the one hand, McAdam expects protest cycles to produce formal organizations due to their greater organizational capacities compared to grass-roots groups (McAdam Reference McAdam1999, 147). On the other hand, there is evidence that with rising protest levels the rate of organization building declines (Minkoff Reference Minkoff1997; Meyer and Minkoff Reference Meyer and Minkoff2004).

Systematically addressing this question in an electoral authoritarian context can help to close a persisting gap in the literature on protest institutionalization. This process is seldom studied outside of Western liberal democracies. Moreover, the few existing comparative works (e.g., Tarrow and Tilly Reference Tarrow, Tilly, Boix and Stokes2007) have not embraced the diversity of authoritarian regimes and thus often equate non-democratic rule with closed authoritarianism (Moss Reference Moss2014), glossing over more subtle but causally important differences. Bringing in the framework of varieties of authoritarianism can thus help to move the debate forward.

A Theory of Organization Building in Diffusing Mass Protest

In defining the dependent variable, I make use of Ahrne and Brunsson’s (Reference Ahrne and Brunsson2011) concept of “partial organizing,” since it adequately captures the varieties of meaningful formalization for SMOs that do not officially register as judicial entities. Its flexibility makes the concept particularly useful for non-democratic contexts, where registration often exposes organizations to repression or obstruction, and is thus sometimes avoided (Moser and Skripchenko Reference Moser and Skripchenko2018). In this study, I define organization building as the founding of a new SMO that is visible to the outside and entails clear decisions on membership (Ahrne and Brunsson Reference Ahrne and Brunsson2011, 85–87).Footnote 1

The argument proposed later will be embedded in an analytical framework that treats protests as critical junctures (Blee Reference Blee2012; della Porta Reference della Porta2018). These are moments of uncertainty, in which agents’ choices have great consequences: “Once a particular option is selected it becomes progressively more difficult to return to the initial point when multiple alternatives were still available” (Mahoney Reference Mahoney2000, 513). However, contingency at the time of a decision does not mean a structural blank slate (Thelen Reference Thelen, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003). Instead, critical antecedents that precede a critical juncture constrain the choice of agents (Capoccia Reference Capoccia, Mahoney and Thelen2015), “combin[ing] in a causal sequence with factors during a critical juncture to produce divergent long-term outcomes” (Slater and Simmons Reference Slater and Simmons2010, 887). Following this reasoning, mass protests that diffuse to different localities are conceptualized here as critical junctures during which actors make choices for or against organization building and the inner structure of new SMOs—choices that are constrained by their local preconditions. In the following, I present this argument in three steps that match the constituent elements of the analytical framework: the critical antecedents, the critical juncture, and the outcome.

The Critical Antecedents: Local Political Structures and Activists’ Repertoires

In this first step I argue that structural features of activists’ local political environments do not directly predict whether and how activists will build organizations during protest. However, these local structures—in particular the local political opportunity structures (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Koopmans, Duyvendak and Giugni1992) and the availability of allies and economic resources—do play an important part in the organization building process, because they shape the repertoires that local activists develop before the onset of the critical juncture and that constrain them in their tactical and organizational choices.

Repertoire is defined by Charles Tilly as “the whole set of means that a group has for making claims” (Tilly Reference Tilly1986, 4). In several influential works, Tilly established two basic points, both of which this first step of the argument draws upon. First, the set of options that actors can choose from is quite literally limited in each given moment: “In something like the style of theatrical performers, participants in contention are enacting available scripts,” with innovation happening mostly within or close to these scripts (Tilly Reference Tilly2008, 15; also Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998). Second, repertoires develop in close interaction with the structural environments that activists find themselves in (Oliver and Myers Reference Oliver and Myers2002; Tilly Reference Tilly2008; Robertson Reference Robertson2011). More specifically, pluralist contexts with open political climates and little repression tend to have broad tactical and inclusive organizational repertoires. By contrast, where contact points to authorities are few, resources are sparse, and repression against political contenders, media, and activists is a real possibility, repertoires can be expected to be narrower and less diverse (see also Maloney, Smith, and Stoker Reference Mahoney2000), with higher repression tightening the bonds between those who dare to resist it by nurturing an “‘us’ versus ‘them’ distinction” (Fox Reference Fox1996, 1091).

The concept of repertoire comprises tactics and organizational forms.Footnote 2 Tactics refers to the set of action forms available to local activists—be it direct action like strikes and blockades, symbolic protest forms like demonstrations or petitions, or less contentious tactics like public discussions and roundtables that seek to implement dialogue with authorities. Organizational repertoires are defined as “a type of competence, a set of familiar patterns for ordering social relations and action” (Clemens Reference Clemens1997, 48)—tried-and-tested organizational models available to activists from cultural socialization or earlier periods of contention. These repertoires may concern how different local actors and groups cooperate (e.g., coalitions versus isolated action) or how existing activist groups are structured (e.g., hierarchy versus horizontality). These repertoires evolve slowly and are shaped by activists’ structural environments and thus vary across states, and—to the extent that regime features vary subnationally (see Fox Reference Fox1996)—also across regions and cities.

The Critical Juncture: Diffusing Mass Protest

The second step of the argument concerns the critical juncture itself. A critical juncture here is conceptualized as the high mobilization phase of a broad and inclusive protest cycle. It is a critical juncture because it brings together an unusual diversity of actors in unexpected quantities—parties, NGOs, and trade unions, but also unaffiliated citizens of various ideological and motivational backgrounds—that jointly constitute and shape “structurally underdetermined [events] characterized by high levels of uncertainty” (della Porta Reference della Porta2018, 7). Decisions taken during such times can have a lasting impact (see also Sewell Reference Sewell1996; Blee Reference Blee2012), also on local civil society. The FFE protests clearly conformed to this definition; they rapidly diffused from Moscow through the country’s urban spaces, mobilizing activists with an unusually broad ideological spectrum and bringing a large number of first-time protesters to the streets (e.g., Bikbov Reference Bikbov2012; Gabowitsch Reference Gabowitsch2016).

The Outcome: Building Protest Organizations

Local organization building during the high phase of diffusing protest is more likely, I argue, when the local and the national interact, i.e., when long-standing local activistsFootnote 3 attempt to employ the diverse, energetic, and resourceful mobilization in their ongoing local struggles.

Whether or not protests produce local organizations,Footnote 4 then, depends on whether the innovation of organization building is perceived as an opportunity to provide established local activists with advantages vis-à-vis their authorities, e.g., as a bargaining tool, for signaling societal support, or for conducting work in their ongoing projects (on perceived opportunities see Kurzman Reference Kurzman1996; Gamson and Meyer Reference Gamson, Meyer, McAdam, McCarthy and Zald1996). While the particular expected use of such an organization is a function of the specifics of the local interactions and thus again depends to a great extent on the political environment in place, a necessary condition for local actors to perceive a diffusing protest wave as an opportunity to further their local goals is that such local goals exist in the first place. Where activists are not currently engaged in local battles when the critical juncture opens up, they will have less interest in organization building.Footnote 5

Finally, in cases when new organizations are founded, I draw on the idea of critical antecedents (Slater and Simmons Reference Slater and Simmons2010) as conditions that allow contingent innovation but constrain actors’ palettes of available choices. Tilly’s concept of repertoire fills this conceptual tool with theoretical content. I argue that even in cases where actors substantially innovate, they will do so by drawing on tactical and organizational templates available from earlier periods of contention. For instance, if the tactical repertoire is confined to conducting demonstrations, the new organization will likely not substantially expand this area of activity; if organizational repertoires include broad coalition building, a new protest SMO will likely be more inclusive than in places dominated by a close-knit group of activists; if existing organizations and activist groups function according to rigid formal or informal hierarchies, a new protest SMO will likely follow their example, and so forth.

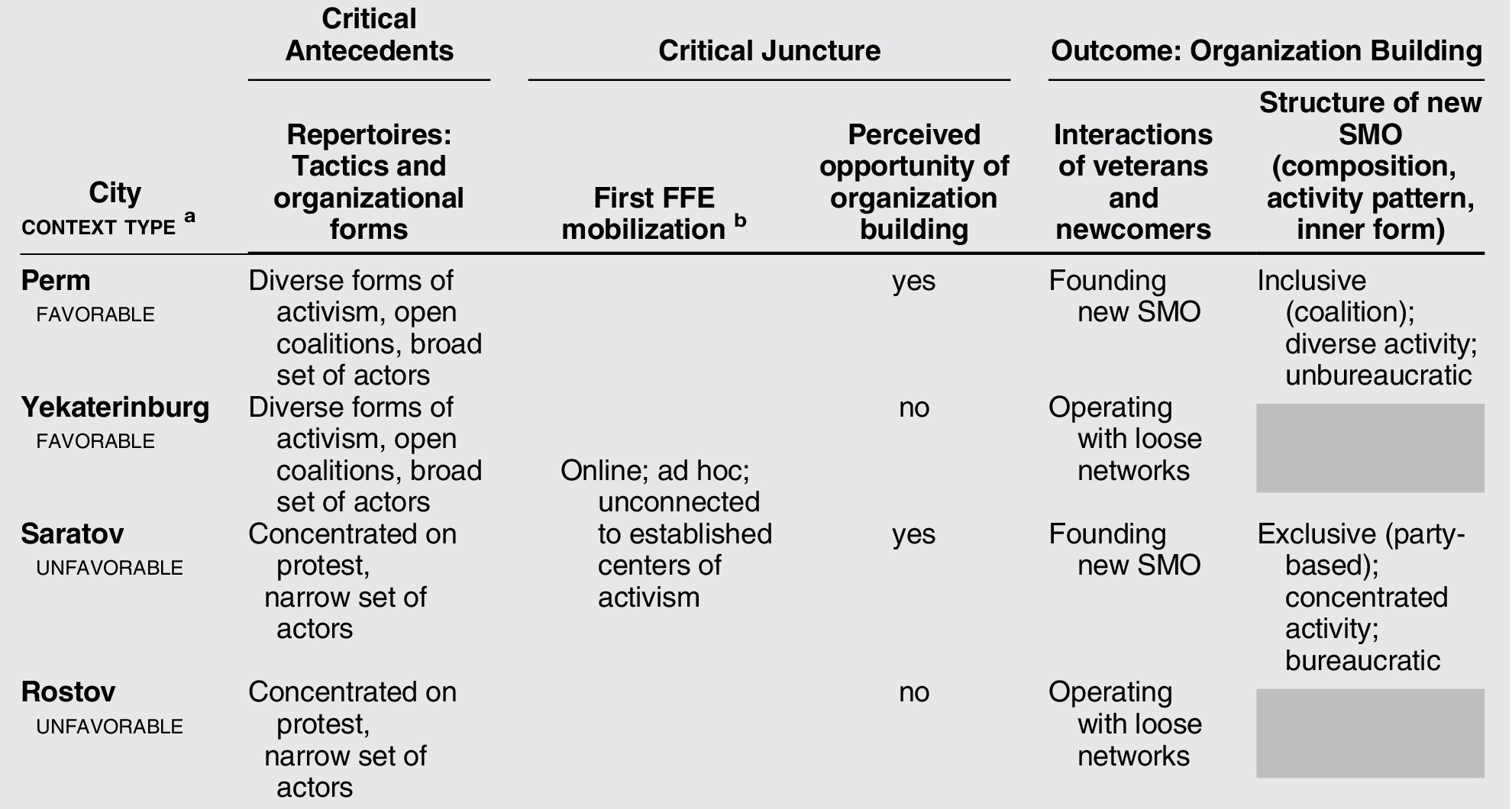

In sum, I propose a meso-level argument that runs from (1) the impact of the structural environment on the development of activists’ repertoires in a particular locality, through (2) diffusing mass protests that present a critical juncture for local organization building, to (3) the formation of new protest SMOs that depends on whether or not established activists perceive the protests as an opportunity to advance their local agendas, and on the existing repertoires that will be mirrored in the newly built organizations. The next sections test this theory, compаring four local instances of the “For Fair Elections” protests.

Case Selection and Operationalization of Structural Variables

My argument will be tested in a within-country comparison. This has the clear methodological advantage that potentially confounding variables, like the reference frames of the protests, can be controlled for by holding them constant (Snyder Reference Snyder2001; Giraudy, Moncada, and Snyder Reference Giraudy, Moncada, Snyder, Giraudy, Moncada and Snyder2019). For the same reason, this design raises questions on the applicability of findings beyond the specific country context. The Russian case, however, displays a profound diversity of subnational political conditions. Because the argument holds that activists’ repertoires are shaped to a great extent in the local political environment, this subnational variance inserts theoretically meaningful context variation and hence allows to claim more general relevance.

Based on a range of empirical indicators, recent studies have argued that the Russian regions represent different electoral authoritarian regime types. In explicit reference to Howard and Roessler’s (Reference Howard and Roessler2006) distinction, Libman (Reference Libman2017, 129) writes that, in the beginning of the 2010s, after ten years of authoritarianization “there still exist[ed] substantial differences in terms of regional politics, which are frequently conceptualized as those between competitive and hegemonic authoritarian regimes” (also Saikkonen Reference Saikkonen2016). Similarly, Ross and Panov identify four regional regime types that span a continuum between “hegemonic authoritarian” regional regimes, where “a dominant actor, usually a governor, is able to dominate the electoral field by controlling the nomination of candidates” and “clearly-competitive authoritarian” regimes, where candidates of the governing party “compete in a genuine struggle for power” (Ross and Panov Reference Ross and Panov2019, 370-71).

To back up this evidence with a cross-national dimension, I use data from the Varieties of Democracy project to demonstrate that Russia in the relevant time period was among the 10% of electoral authoritarian countries with the highest unevenness in the conduct of subnational elections (refer to the online appendix). Based on these findings I argue that, if the selected subnational cases maximize the within-country differences in structural conditions, these provide enough variation in political context for the argument to yield insights that are conceptually relevant beyond Russia’s borders— provided that its application is limited to electoral authoritarian regimes.

Cases are selected in a three-step process. In step one, a universe of cases is defined. I include cities that, first, displayed a minimum of sixFootnote 6 protest events related to the FFE-protests between the parliamentary elections on December 4, 2011, and the demonstration on Moscow’s Bolotnaya square on May 6, 2012, which is widely regarded as the beginning of the protest cycle’s end. Second, I exclude St. Petersburg and Moscow on the one hand, and all cities with less than 500,000 inhabitants on the other, to ensure a minimum of comparability regarding scale effects on protest. Third, only regional capitals (eighty-three at the time) make their way into the universe of cases to control for their special status in the federal administrative hierarchy (Golosov, Gushchina, and Kononenko Reference Golosov, Gushchina and Kononenko2016). This first step produces a set of twenty cities.

Steps two and three specify and operationalize political and economic conditions with the aim to select two cities with a favorable, and two cities with an unfavorable structural environment for protest institutionalization. Focusing on the structural conditions only, organization building during a protest wave is expected to be most likely in the favorable contexts, and least likely in the unfavorable ones. This crucial case logic increases inferential leverage for a proposed theory if a most-likely case fails to produce the outcome, or a least-likely case displays it (Levy Reference Levy2008, 12–13), substantiating the causal weight of other factors (in this study: repertoires and perceived opportunities) that differ between the “passed” and the “failed” cases (see Rohlfing Reference Rohlfing2012, ch. 3). This, however, does not mean that structural conditions are irrelevant: they are a crucial, though mostly indirect, part of the argument since they shape established activists’ repertoires and opportunities.

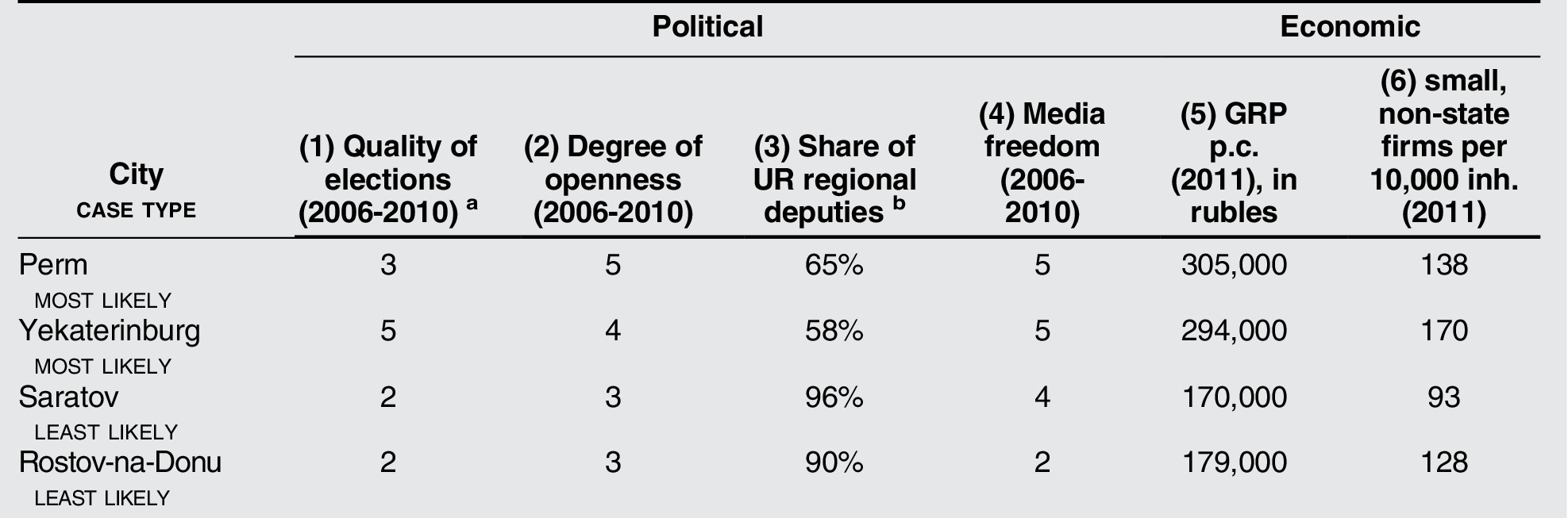

Step two. For selecting cases on political context conditions, I partly draw from Petrov and Titkov’s (Reference Petrov and Titkov2013) widely used index that uses expert ratings to assess ten dimensions of regional democracy between 2006 and 2010 on five-point scales. Since the index covers five-year periods, its accuracy is naturally limited. However, in their summary of several recent findings, Lankina, Libman, and Obydenkova (Reference Lankina, Libman and Obydenkova2016) conclude that, despite its weaknesses, the index is a valid approximation of important structural features: its experts ratings show strong correlations with hard indicators, and several case studies (including the present one) report congruence with the index’s assessments. While I do not expect the index to give precise accounts, I therefore argue that it is a useful heuristic to approximate general patterns.

A favorable political environment is conceptualized to comprise, first, relatively open political opportunity structures, defined by Kriesi et al. (Reference Kriesi, Koopmans, Duyvendak and Giugni1992) as consisting of a formal dimension (the functioning of political institutions such as elections) and an informal one (strategies of authorities to deal with outsiders). Where channels of bottom-up influence exist and function reliably without excessive obstruction and repression of challengers, activist groups find better working conditions, which enhances efficacy and should thus incentivize organization building. Two indicators from the Petrov/Titkov index are employed to operationalize the formal and informal openness of regional political systems: the overall quality of elections and the openness of political processes.

Second, research from Western Europe shows that, if movements are able to attract resourceful allies such as parties or individual politicians, the chance to institutionalize increases (Kriesi, Koopmans, and Duyvendak Reference Kriesi, Koopmans and Duyvendak1995). The availability of allies is operationalized negatively through the share of seats in the regional legislature controlled by the governing party United Russia (UR). More seats controlled by other forces than UR mean a higher chance that individual politicians are present who, for instance, can supply resources like finances, infrastructure, and contacts to authorities (Tarrow and Tilly Reference Tarrow, Tilly, Boix and Stokes2007; on Russia see White Reference White2015).

Finally, I assume that the presence of politically independent media that can report on the FFE protests and the organizations that emerge from them without having to fear repression are important resources for the institutionalization process, since coverage can increase efficacy of groups’ actions and helps to attract new activists. The availability of favorable media coverage is operationalized through Petrov and Titkov’s indicator for regional media freedom. Footnote 7

Step three. Since variation in economic conditions has a strong impact on political developments across the Russian regions (e.g., Gel’man et al. Reference Gel’man, Ryzhenkov, Belokurova and Borisova2008), the third step operationalizes the availability of economic resources. For this, I rely on two variables—Gross Regional Product per capita and the number of small, non-stateFootnote 8 enterprises per 10,000 inhabitants—that are both taken from Rosstat, the official Russian state statistics service. The reasoning behind the former is that in richer regions, more resources may potentially be channeled to activist groups, which is essential for sustaining their activity (see, e.g., Davenport Reference Davenport2014). The choice of the latter variable reflects that both firm size and state ownership are strong predictors of political loyalty of employers (Frye, Reuter, and Szakonyi Reference Frye, Reuter and Szakonyi2014), suggesting that small, private firms are the most likely sponsors for oppositional activity (thus making regional politics less dependent on politically controlled clientelist structures). In addition, both higher income levels and a larger non-state sector may increase the supply of available activists (Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2017).

To identify two most-likely and two least-likely cases, I select regions from the universe of cases that constantly feature at the top of the list on both dimensions (Perm and Yekaterinburg) and two that constantly feature at the lower end (Saratov and Rostov-na-Donu). Table 1 summarizes the structural indicators in the four cases. The online appendix demonstrates that the selected cities maximize the variation of context conditions.

Table 1 Structural factors used for case selection

Notes: UR = United Russia. a On (1), (2), and (4), scales are 1 to 5, see Petrov and Titkov Reference Petrov and Titkov2013. b Share of seats in regional legislatures according to the latest regional election preceding the beginning of the protests in December 2011, based on Kynev Reference Kynev2009, Reference Kynev2014. Economic factors based on Rosstat, see ICSID n.d.

Data and Methods

To facilitate triangulation in reconstructing the organization building process during the protest cycles, several data types are combined. The first data source is sixty-five semi-structured interviews with participants and observers of the protest cycles (14–22 per city) mostly carried out between September and November 2017 (refer to the online appendix). Interview partners were not selected to obtain a representative sample of the protest participants, but to gain insights into the organizational processes during and after the peak of mobilization.

The second data source is a base of 1,087 local media reports, which were assembled using the Integrum database and were subsequently coded. The first component (corpus A) features 315 reports on forms, actors, and claims of protests between January and November 2011, i.e., before the outbreak of the FFE protests in December. The second component (corpus B) contains 772 reportsFootnote 9 on the local FFE protests in all four selected cities and, where new SMOs were founded during the protests, on their activities (refer to the online appendix for detailed information on the interviews, a discussion of the selection of press sources, and coding rules). Finally, a third data source is documents like charters of new SMOs and meeting minutes that were obtained directly from activists, and social media posts (110 in total), public reports, and mobilizational materials that were accessed online (refer to n. 10 for a guide to the labeling of interview sources).Footnote 10

I now present the four case studies as structured analytical narratives. The first section of each case study outlines the political context factors–political opportunities and resources—that were available to activists prior to the onset of the critical juncture and then specifies the tactical and organizational repertoires (i.e., the critical antecedents) that evolved within these structural environments. The second section details the interaction of agents during the critical juncture, focusing on the decision for or against organization building, and, if new SMOs were founded, their composition, their inner form, and their activity pattern.

Case Study I: Perm

Structures and Repertoires

In the 1990s and early 2000s, political pluralism and electoral results for liberal parties were higher than the national average (S05P). Although elections in Perm were never subject to much falsification or abuse of administrative resources (S05P), in the beginning of the 2000s, a process of elite consolidation set in, during which formal political competition was gradually reduced and the regional level began to establish control over the municipal one (Kovin Reference Kovin and Tregubova2013). The gradual closure of formal opportunities was, however, partly compensated by an unusual informal openness of regional and local authorities and the continuing presence of allies in the form of independent politicians and business people with their own resource bases, who were ready to collaborate with civic activists and to develop alternative policy proposals (Kovin Reference Kovin and Tregubova2013; A08P; S03P).

Tactical and organizational repertoire. In this comparatively open and resource-rich environment, activists developed a diverse repertoire. Most action was geared towards pragmatic cooperation. Igor Averkiev, a central NGO activist, drew up a list of “rules for dealing with authorities” in 2004 (Averkiev Reference Averkiev2004). This model entailed frequent public discussions, roundtables, and working groups that brought together NGO activists, local academics, and representatives of authorities. The application of this model resulted in several constructive interactions that even led to the adoption of bills drafted by civic actors, sometimes in collaboration with the region’s Human Rights Ombudsman (Kovin Reference Kovin and Tregubova2013). But activists also knew to pressure authorities with more contentious tactics. For instance, on November 19, 2011, shortly before the FFE protests broke out, a large rally was organized by civic activists of various ideological convictions, jointly demanding Governor Oleg Chirkunov’s resignation (N78). One newspaper reported that the event assembled “cultural workers, members of the intelligentsia, … human rights activists, … deputies and those who never heard these deputies’ names” (N78). While this may be an over-enthusiastic depiction, the resolution that was adopted at the event clearly shows the breadth of demands ranging from an end to Chirkunov’s controversial cultural policyFootnote 11 over housing problems and welfare claims to criticism of excessive regional influence on the municipal level (Nesekretno 2011), proving a successful instance of frame bridging that culminated in a shared anti-gubernatorial stance.

Organized activism was thus frequently characterized by broad coalitions of various NGOs, individual parliamentary deputies, and single activists. At the center usually stood four human rights groups that had formed in the 1990s and had gained a strong local reputation (P01P; S02P). These coalitions sometimes endured over months or even years, as was the case in a campaign against the planned abolishment of direct mayoral elections in 2009–2010 (A08P; P02P; S05P) and were supported by and connected to a significant share of the urban populace.

Organization Building during the Protest Cycle

In Perm, just like in the following cases, none of the described groups, coalitions, or individuals stood at the outset of the local protest cycle. Instead, the protests began in online discussions on the Facebook equivalent VKontakte (VK), where people received news about the electoral falsifications and the beginning protests in Moscow and called for action in their hometown. Two young activists with some experience found their way into these discussions and helped to set up the first improvised protest action, followed by another, larger event a few days later (A04P; A10P).

Founding a new protest SMO. The long-standing civil society activists at first perceived the erupting protests in Moscow as “fashion” (P02P), “not our protest” (A08P), “unimportant” (S05P), something detached from their local concerns—especially since electoral falsifications in Perm had not been extensive. But when the protests diffused to Perm and gained momentum, the veterans seized the initiative from the newcomers, called a meeting in a downtown restaurant and, together with several activists from the VK group, laid the foundation for a new SMO—the Council of 24th December (named after the day on which it came into existence).

I argue that the main reason for investing in organization building was that the established activists saw this emerging movement as a chance to propel their long-standing campaign against the governor. In the discussions in the new organization, the digitally mobilized first-time activists focused on the national agenda, demanding free elections and more honesty in politics, while the veteran activists pushed their regional agenda that included Chirkunov’s resignation (P01P; A09P; A10P). A newcomer recalled that “at the first stage there was a conflict: ‘Who are we up against: [Governor] Chirkunov or [Prime Minister] Putin?’ For the youth, it was important to be against Putin, and for the civic activists and politicians to be against Chirkunov. Some of [the latter] joined just because of that” (P01P). Another newcomer confirmed that “they [the veterans] had an exclusively local agenda. On all protests they [agitated for the resignation of] Chirkunov. And we: ‘we need to change the country, why are you so fixed on him?’” (A09P).

The change of agenda as a result of the established activists’ increased engagement is further corroborated when comparing the list of demands of the demonstrations of December 11 and 24 respectively; the latter included Chirkunov’s resignation (N908), while the former, where established activists played almost no role, did not (SM81). Moreover, brokered by the Human Rights Ombudsman, the Council organized a closed-door meeting with Chirkunov in January 2012, where they pressed different demands concerning regional and local elections, referenda, and the protests’ resolutions (P01P; A08P; S04P). The available evidence therefore strongly suggests that it was the perceived opportunity to increase their standing and their bargaining power vis-à-vis the authorities that brought veteran activists to engage in the protests and to invest in organization building.

Structuring the new SMO. The established activists understood that the organizers of the first events needed to be included in any new initiative, because they commanded the mobilizational resources through the VK group (A04P). So, the Council was divided into three factions of seven members each: (1) long-standing civic activists, (2) politicians, and (3) so-called “online activists” (S03P; ID01P), with the latter faction being composed largely of young people without prior connections to the members of faction (1) and (2). The Council’s internal structure was designed to facilitate understanding and to create balance between the camps: Decisions were to be taken by simple majority (ID04P), and two Council members, one veteran and one newcomer, were made director and press secretary, paid by funds provided by two member politicians, as a “measure to keep these different people together for longer” (S05P).

These measures usually allowed consensus across the veteran/newcomer divide (A04P; A09P), although the structural majority that veterans had formed by making up two of the three factions meant that newcomers could not prevent the local agenda from being introduced, which frustrated two of them, leading to their withdrawal from the political activist scene in subsequent months (A10S).

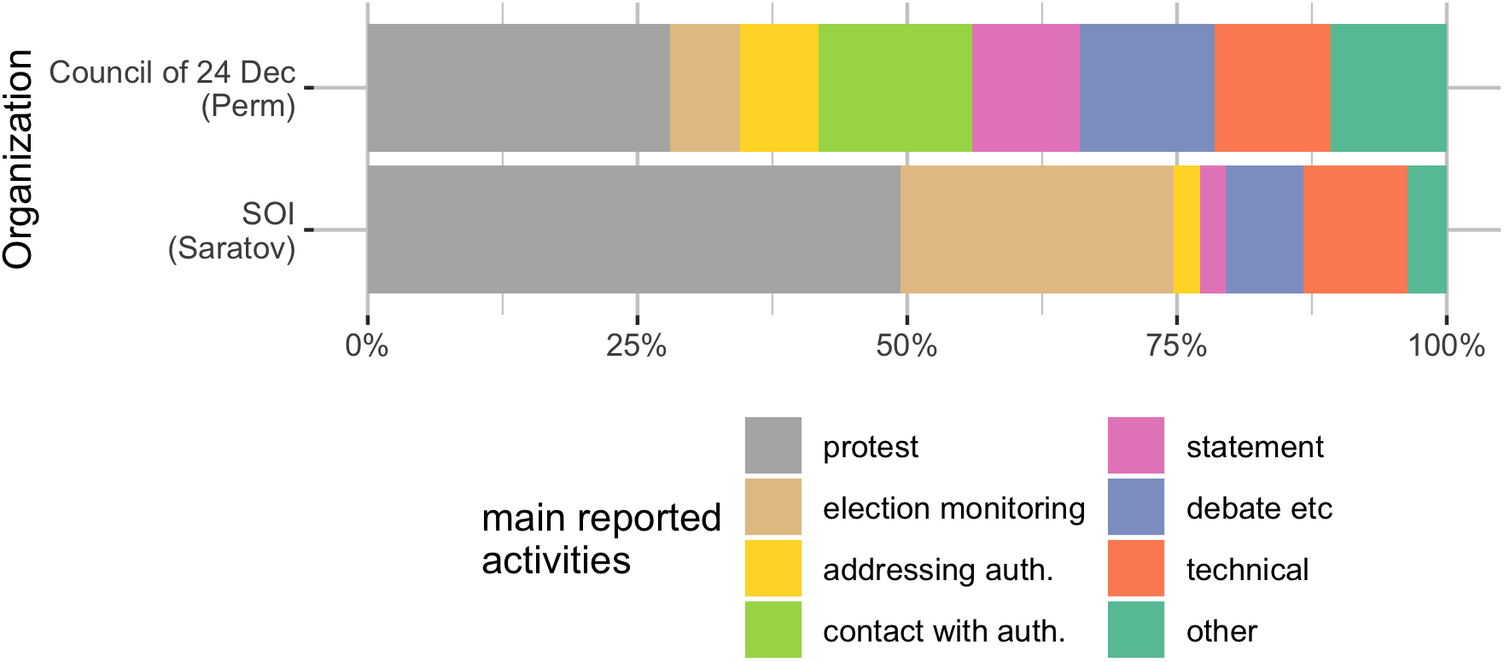

Although the new SMO was an innovation, actors’ organizational repertoire clearly shines through: At the core of the Council stood a group of activists and politicians with diverse organizational affiliations and political outlooks but with overlapping local agendas, who knew each other from the numerous previous coalitions. Likewise, the Council’s activities closely resembled the existing, diverse tactical repertoire (refer to figure 1). Its activities included contentious practices like the organization of protests and electoral monitoring, but also continued the cooperative traditions, manifesting in several debates and roundtables and the meeting with governor Chirkunov. In sum, therefore, I argue that the outcome in the first case was caused by an interplay of a perceived opportunity and existing templates of action and organization available from pre-FFE times.

Figure 1 New protest SMOs and their main reported activities in Perm and Saratov between December 2011 and March 2012

Notes: “Technical” refers to media mentions about the composition of the groups, their founding and dissolution. Total media mentions of activities: 232 in Perm, 83 in Saratov.

Source: Newspaper reports (corpus B).

Case Study II: Yekaterinburg

Structures and Repertoires

Throughout its post-Soviet history, politics in the Ural’s capital and the Sverdlovsk region had been characterized by conflict between the local and the regional layer of administration (Il’chenko Reference Il’chenko and Ross2015; A05Y). In contrast to other regional centers, this basic conflict survived the construction of the “power vertical” by President Putin in the 2000s. In addition, strong economic development through the 2000s contributed not only to the emergence of a relatively well-off and educated urban middle class, but also to the establishment of a group of independent business people with vested political interests (A05Y), who aligned with various political actors (Il’chenko Reference Il’chenko and Ross2015). Despite the authoritarianization emanating from the federal center (Kynev Reference Kynev2014, 586–92), the continuing conflict provided for higher degrees of pluralism and more public contestation than in other Russian regions, which was both evident in and perpetuated by a diverse local media landscape (J01Y). In this relatively open pluralist context where dissenting actors did not have to fear substantial repression, tactical and organizational repertoires developed that resembled Perm’s in critical ways.

Tactical and organizational repertoire. The emergence of a diverse tactical repertoire, ranging from relatively frequent and large demonstrations to the organized use of official democratic instruments like public hearings and discussions, was accelerated by the entering of Leonid Volkov into local politics. A young mathematician and programmer, Volkov became popular among the city’s emerging middle class through his blog, begun in 2007. In 2009, without any connections to politics (A03Y), he won a seat in the local parliament. Around the same time, he became the head of the local chapters of the electoral observer organization Golos and the liberal coalition Solidarnost’ Footnote 12 (A02Y; A05Y). In 2010 and 2011, he led three campaigns that all involved large rallies—one against the construction of a cathedral on a central square,Footnote 13 one for the preservation of direct mayoral elections (J02Y; A03Y), and one for granting him access to the regional elections of December 2011, from which he had been excluded on dubious grounds (Ekho Moskvy Reference Moskvy2011). As Lankina’s (Reference Lankina2018) data set suggests, protest had been frequent before, but it had been dominated by social and economic concerns (P03Y). These new campaigns, by contrast, were carried out in defense of moral and political values, bringing a new group of people to the streets and into activism: highly educated, sometimes even affluent urbanites (Il’chenko Reference Il’chenko and Ross2015).

As in Perm, organized activism before the FFE protests was often carried out in broad coalitions that involved actors and groups with different ideological programs but with overlapping local agendas and with firm connections to the wider citizenry. The campaign for retaining mayoral elections, for instance, was coordinated by a group called the “Committee for the Right to Vote” (CRV) composed of several liberal activists, a respected local scholar, a journalist, and a deputy of the Communist Party (CPRF) (P01Y; J02Y). In contrast to Perm, however, there was informal but clear personal leadership, as Volkov was always in the center of mobilization and organization (e.g., P01Y; A05Y; A08Y).

To the extent that Volkov established himself as the center of liberal activism, this left an imprint on the dominant organizational practices. Using digital communication tools, he developed a style of ad hoc coordination— “decisions without meetings,” as one aide put it (A08Y)—without fixed roles, let alone formal organizations: “Everything was communicated on the fly” (A03Y).

Ad hoc Coordination during the Protest Cycle

The protests started out similarly to the other studied cases. A VKontakte group appeared “out of nowhere” (A08Y), where people unknown to the established activists coordinated a flash mob and a spontaneous march to the building of the city administration (P03Y). But after the first actions, a loose organizational committee began to form around Leonid Volkov. It included several members of the CRV (A01Y; A03Y), two young activists from the Communist Party (who used their connections to the party’s follower base and its financial resources for mobilization), an activist of the social liberal Yabloko party, and several people from Volkov’s orbit (P01P; P03P). These established activists worked together with numerous newcomers, registering the planned protest events with authorities and coordinating the online and offline mobilization (P03Y; A06Y).

Coordination during the protests was ad hoc, inclusive and noncommittal. In fact, “anyone could join” (A03Y). The working atmosphere inside the committee was described as good, there was “no internal competition” between political camps (A01Y), and it functioned without fixed roles: at the meetings in Volkov’s deputy reception room people simply took on tasks themselves and effected them (A09Y).

In crucial difference to Perm, this informal coordination never gave way to a phase of organization building, so that the protests petered out in parallel to the national protest wave without leaving behind any new SMOs. What accounts for this non-outcome is, I argue, that the group around Volkov had no ongoing projects that would have benefitted from institutionalizing the protests into a permanently active collective actor: The local battles of 2010 and 2011 had been fought and won or lost: The church was not built, the mayoral elections were retained (albeit with a mayor who was stripped of most of his powers), and Volkov was excluded from the regional ballot without a chance to be reinstated. At this moment, therefore, the central activists were not waging campaigns into which they could usefully channel the FFE mobilization. In addition, even if the protests had appeared as an opportunity to further a local cause, the organizational repertoire of ad hoc coordination established since the late 2010s was not conducive to formalization. Both of these factors—the absence of a perceived opportunity and a specific organizational repertoire—made it highly unlikely for established actors to invest in organization building at the particular time when the critical juncture opened up. As a consequence, the FFE protest cycle did not trigger a break from the established patterns of activism.Footnote 14

Case Study III: Saratov

Structures and Repertoires

As the case selection strategy implies, pre-FFE Saratov presents a stark contrast to the two cases just described. Elections were strongly controlled, with a long history of falsifications and backroom deals instead of open contestation (A02S). Although broad and open repression was infrequent, potential conflict between levels of government had been prevented from fueling public displays of political discontent, while political challengers with independent resource bases were absent, and any formally organized opposition was marginalized with the help of courts, tax authorities, and other instruments (Gel’man et al. Reference Gel’man, Ryzhenkov, Belokurova and Borisova2008). Moreover, even formally independent media operated under the permanent threat of harassment or the cutting of informal payments from authorities (A10S; A12S).

Tactical and organizational repertoire. Given the closed opportunity structures and the lack of allies and contacts to authorities, the repertoire of local agents was—in contrast to the previous two cases—largely confined to symbolic contention like protest demonstrations. Even when conducted by several parties, these rallies hardly gathered more than 200 participants (N197; N207; N227), suggesting that oppositional political society was largely disconnected from the broader urban public.

Consequently, large civic coalitions of the Perm and Yekaterinburg type were nowhere in sight. Instead, protest in Saratov in the late 2000s was often carried out with the support or within the campaigns of opposition parties (A14S), whose predominance on this field attests to the relative organizational weakness of other civic actorsFootnote 15 and suggests that in the absence of other channels of influence, parties resorted to street protests as a relatively cost-effective way to raise awareness. The press report database (corpus A) confirms the interview accounts: in 2011, more than half of the 43 protest events between January and November 2011 were at least co-organized by a political party (see figure A1 in the online appendix), which is about twice the share of Perm and Rostov and four times the share of Yekaterinburg.

After municipal elections in March 2011, four parties— the CPRF, Yabloko, the social democratic JR and the nationalist LDPR—officially formed a local alliance, whose main intention was to achieve the revocation of the municipal election results (N199) and who cooperated in the organization of small protest rallies on March 18 (N197), April 2 (N207), and May 19 (N227). Shortly before the FFE protests began, therefore, the organizational repertoire was characterized by cooperation between a limited set of decidedly political actors who focused their attention on the electoral process rather than particular policy projects or broader local issues.

Organization Building during the Protest Cycle

As in the other cities, a first colorful rally was organized through VKontakte and held on December 10. During the following month, a critical organizational innovation was undertaken that differed from Perm’s Council in essential ways.

Founding a new protest SMO. Towards the end of December, a heterogeneous committee formed to organize the following rallies. Recruited from this committee, a smaller circle of party and political NGO activists got together to establish a new SMO, the Saratov Association of Voters (SOI in Russian). This body was supposed to unite opposition-minded people from various ideological strands around electoral control, since all opposition parties had suffered from falsifications at the ballot box (A09S; N1364) and sought to gain votes and secure proper vote counting to increase their “political maneuver space” (A09S). In this effort, the local party leader who proposed the idea specifically linked it to the party alliance formed earlier that year. In a VK post, he wrote that “in terms of its public and practical content, SOI is a successor to the inter-party committee ‘Saratov—fair elections!’ (LDPR, CPRF, ‘Just Russia’, ‘Yabloko’), established in the run-up to the elections to the Saratov City Duma in March 2011, as well as the protest movement of Saratov’s citizens” (SM110).

Again, what gave the impulse for organization building during the protests’ early phase was the perceived opportunity of local agents—this time, mostly party activists— to employ the emerging movement in their struggle to improve the local electoral process.

Structuring the new SMO. The way this new SMO was set up resembled the tactical and organizational repertoires available to the involved activists in at least two ways. The first concerned its composition. In inviting potential members for setting up the organization, its founders excluded several participants of the protests’ first loose organizational committee who were not members of established political organizations (A09S; A14S), reducing the circle to activists who “knew each other from before” (A06S). The focus both in the participants’ recollections (A01S; A06S; A13S) and in the public record of this meeting (Kommersant 2012) was clearly on parties, while unaffiliated activists were represented only by the two administrators of the VK group (A11S; A14S). The latter found their position to be too marginal to meaningfully contribute and left the project frustratedly, complaining in the VK group that “it is necessary to say that such a balance of forces [in SOI] reflects society’s real moods even less than the current State Duma [the national parliament]? We fully understand the natural aspiration of our political parties to crush the civil movement, but we reserve the right to expose these aspirations” (SM21).

The focus on a specific subset of agents in forming the new group that—at least in the initial stages—excluded most of the newcomers without clear political affiliations reflects the organizational patterns that dominated local activism before the outbreak of the FFE protests.

The second way in which these patterns revealed themselves concerns SOI’s internal structure. One of the few newcomers who had been invited to the founding meeting but left in frustration, observed about the internal proceedings that “SOI consisted of [the liberal party] PARNAS, Yabloko, the Prokhorov platformFootnote 16; and there were also the communists … Everyone tried to hold round tables … where decisions and memoranda were made. All the time they were voting, accepting something, as parties all like to do” (A11S).

This clearly shows this activist’s disappointment, but the description of the formalistic, bureaucratic process seems accurate, as accounts from involved activists confirm (A02S; A04S; A09S). Indeed, establishing fixed roles and procedures was part of the founder’s strategy to create an organization that would effectively conduct electoral monitoring in the upcoming presidential elections of March 2012, the declared main goal of the new SMO (A09S). He was aware that there were potential drawbacks, but set clear priorities: “the structure may seem bureaucratic, but it is a protection mechanism … . There is a trade-off: on the one hand dry, uninteresting, bureaucratic [work], and on the other hand—if there are no positions prescribed on paper, there is no organization” (A09S).

Internal organizing practices of the dominating parties thus not simply spilt over into the new SMO but were consciously introduced. The effect is clearly visible in SOI’s activity pattern over the high phase of the protest cycle, which is focused on protest and electoral monitoring – much less diverse than in Perm (see figure 1).

Case Study IV: Rostov-na-Donu

Structures and Repertoires

Over the post-Soviet period, Rostov’s political structures, both formally and informally, were closed to outside influence. Opposition parties were hardly represented in the political institutions (the CPRF being a partial exception) and were no reliable allies for oppositional political or civic projects (McFaul and Petrov Reference McFaul, McFaul and Petrov1998; Kynev Reference Kynev2014). Moreover, allies in the form of independent media and resourceful independent political challengers or businesspeople were virtually non-existent (S01R), since the authorities had set clear examples by severely punishing independent business owners’ political activity several times in the 2000s (S01R; A07R). Repression against even small acts of political dissent was on a comparatively high level, as evident in the frequent mentioning of arrests and threats in interviews compared to the other cases.

Tactical and organizational repertoire. In this environment, any form of activism was precarious and marginal. To be sure, Rostov was not devoid of protest. There was mobilization in the coal-mining sector and on environmental issues in the 1990s, while Lankina’s (Reference Lankina2018) data point to several comparatively large protest rallies in the second half of the 2000s, e.g., by veterans of the Chernobyl catastrophe and nationalist youth. However, these events hardly produced any stable activist groups. The only source of permanent contention was a small group of persistent, “non-systemic” oppositionists (i.e., not belonging to a parliamentary opposition party) who tirelessly staged small protest pickets across the city, always risking arrest and obstruction from authorities. Their tactical repertoire was strictly limited to protest, and their pickets attracted even fewer participants than party protest in Saratov—usually about 30–50 (A04R; P01R). These events were exclusively political in nature and usually targeted national developments rather than local issues.

This small activist group displayed a very heterogeneous ideological background, with activists identifying with liberal groups like Solidarnost’ or the United Civic Front, with the Left Front, or with Other Russia—the successor organization of the National Bolshevik Party that had been banned in 2007, whose ideology blended fascism and state socialism (A02R; A04R; A10R; A11R). Members of this informal alliance bridged their political differences by limiting their joint actions to the lowest common denominator of criticizing the national authorities and demanding freedom of assembly. However, this cross-ideological group of battle-hardened activists lacked stable working connections to opposition politics (to the extent that these existed), to actors of social protests, and to the urban population at large. Coalitions of the Perm and Yekaterinburg type were thus, again, not part of the organizational repertoire.

Ad hoc Coordination during the Protest Cycle

The FFE protest cycle in Rostov began with several events that were organized online in an ad hoc fashion and conducted by people unknown to the city’s long-standing protest group. On December 6, a rally of mostly young protesters, holding up blank pieces of paper, was dispersed by riot police with forty-nine people arrested (N166). A second rally was held on December 10—and still one of the major organizers of oppositional protest in Rostov claimed to have no knowledge of those behind the event (A02R). It was only in preparation for the cycle’s major rally on December 24 that the established activists got together with some of the newly mobilized youth to jointly organize the protests. But the central activists still had no full understanding of the protests’ new anonymous youthful base (A04R; A11R). Several interviewees claimed that mobilization to the demonstrations often happened without direct connection to the organizational committee (A04R; A11R; A12R). Spontaneous mobilization overall lasted longer and was less successfully integrated than in the other cases, even compared to the loose organizational committee of Yekaterinburg.

As in all other cases, the established activists hoped that the protests would swell the ranks of their small political organizations, like Solidarnost’ or the Left Front (A02R), but—in contrast to Perm and Saratov, and much like in Yekaterinburg—they made no attempts at organization building. Again, I argue that the primary explanation of this non-outcome is to be found in established activists’ lack of perceived opportunities and their existing repertoires. In contrast to Perm and Saratov, activists had little grounding in local issues and conflicts. This is further illustrated by the fact that they did not introduce local demands into the demonstrations, instead focusing exclusively on the national agenda (A02R; A11R), critiquing the federal elections and prime minister Vladimir Putin. Had activists been more engaged on the local level (which was, however, very difficult given the closed local environment and the ideological heterogeneity of the group), this could have provided them with a stronger impulse towards stabilizing the movement and harnessing it for further battles by channeling it into a new organization. Moreover, the tactical repertoire that was limited to protest pickets did not provide templates for other action, while the habit of organizing in a close-knit circle of committed activists that was fostered by the comparatively high level of repression made the group quite resilient but did not offer scripts for dealing with a sudden influx of new activists.

As a consequence, the protests quickly petered out after the presidential elections in early March 2012, while the composition of remaining small protest gradually came to resemble the old guard of pre-FFE political activism (A02R; A04R; A11R).Footnote 17 Table 2 summarizes the findings of the four case studies and places them in the 3-step analytical model.

Table 2 Organizational outcomes of diffusing protest

Notes: a Structural factors used for defining favorability of context for long-term institutionalization: (1) Formal and (2) informal openness of political opportunity structure, (3) availability of allies in the political institutions, (4) media resources, (5) GRP per capita, (6) small, non-state firms per 10,000 inhabitants. b FFE = For Fair Elections

Discussion and Conclusion

When does diffusing protest in an electoral authoritarian regime produce new local activist organizations? I have argued that organization building in these situations is more likely when the national and the local interact, i.e., when long-standing activists are willing and able to use the protests for their ongoing local struggles. Whether and how they do this depends, in turn, on their accumulated experience of interactions with authorities in their particular political environment.

More specifically, I have proposed three interrelated causal factors—(1) structures, (2) repertoires, and (3) perceived opportunities—that jointly account for the emergence and the form of new local SMOs. As the crucial case design has demonstrated, (1) local opportunity structures, available allies, and resources do not directly predict organization building during a wave of mass protests. Instead, these structural facilitators and constraints contribute over years (and sometimes decades) to the development of (2) distinct sets of repertoires that activists use in their interactions with authorities. When a critical juncture in the form of diffusing mass protests opens up, local organization building is more likelyFootnote 18 in case these established activists (3) perceive the protests as an opportunity to advance their local agendas. In that process of forming new SMOs, established activist then tend to fall back on the tactical and organizational repertoires developed in earlier periods of contention.

Leveraging Russia’s exceptional subnational variability, the case selection has approximated the difference in local political conditions between competitive and hegemonic authoritarian regimes, providing enough contextual variance for the argument to travel. At the same time, the study has controlled for city size, administrative status, the reference frames of the protest cycle, and the national political environment. Holding these factors constant provided a methodological advantage for the case comparisons (Snyder Reference Snyder2001), but a next step should take the theory to a test that includes variation on conditions that the present study has bracketed out. Before that, however, its scope conditions need to be properly defined.

The case selection does not warrant extrapolation beyond the limits of electoral authoritarianism. This concerns more open and democratic contexts, but also fully repressive ones. Where resources abound and the political structures are receptive to various sorts of civic input so that the local activist scene is large and endowed with a multitude of tactical and organizational templates, these might cancel each other out or produce conflict rather than dominating the organizational decisions as they did in the studied cases. But repression also needs to stay below a threshold that precludes the public formation of openly dissenting activist groups. Any applications of the argument must therefore be kept within the confines of electoral authoritarianism (classically, Schedler Reference Schedler2010).

If these boundaries are respected, the study can make a contribution to theory in three distinct ways. First, offering a concrete application of the recent suggestion to understand protest cycles as critical junctures (della Porta Reference della Porta2018), it fuses structure and agency (Blee Reference Blee2012, 38) in one explanatory model that can be utilized in other contexts and even filled with other variables. Second, it highlights the importance of varieties of authoritarianism (e.g., Howard and Roessler Reference Howard and Roessler2006) for social movement theory, which still often operates with a binary distinction between democracy and autocracy. In both types of contexts, the findings suggest, protests can produce new SMOs. However, to the extent that closed, resource-poor, and more repressive environments induce experienced activists to develop narrower and more stringent tactical and organizational templates, the founding processes of SMOs are likely to be characterized by substantially different input across contexts. Finally, the study illuminates within-country differences in the functioning of hybrid regimes and demonstrates how local political conditions indirectly shape protest trajectories and affect opposition action. It thereby supports the recent move in comparative politics to give more systematic attention to the subnational level (Giraudy, Moncada, and Snyder Reference Giraudy, Moncada, Snyder, Giraudy, Moncada and Snyder2019).

I propose the following questions to be addressed in future research. First, understanding that organization building in protest waves is especially relevant under RMT’s assumption that organizations can keep a movement going after the demobilization of protest (Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1998). In the studied cases, there is tentative evidence that the early organization building observed in Perm and Saratov indeed stimulated an abeyance process that was absent in the other two cities. For instance, when the liberal opposition politician Aleksey Navalny conducted his country-wide presidential campaign in 2017–2018, in Perm his campaign office was operated by several activists who had begun their activism in connection to Perm’s Council (Dollbaum Reference Dollbaum2020). In Saratov, an indirect result of the early organization building was the emergence of a new local media source that developed into a new center of liberal activism which supplied Navalny’s activists with judicial help and media coverage. It therefore appears that early organization building can be an important ingredient if protest waves are to incrementally contribute to civil society growth. Further studies should substantiate these findings and systematically compare them to other institutionalization processes.

Second, the findings recall the old oligarchization dilemma postulating that effectiveness comes at the cost of hierarchy (Rucht Reference Rucht1999). From the perspective of organization building, the protests were most successful when veterans seized the initiative, thereby provoking resistance and frustration of some central newcomers (especially in Saratov), while the less structured interactions in Yekaterinburg and Rostov were more harmonious but less productive. Further research could investigate under which conditions this dilemma can be avoided or mitigated by conscious design of rules for membership and decision-making (see, e.g., Sutherland, Land, and Böhm Reference Sutherland, Land and Böhm2014). While such strategies may help activists to overcome conflict and create synergies, this study suggests that repertoires from earlier periods of contention will continue to play a major role.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1. Additional Figures

Appendix 2. Extrapolation of Results beyond the Russian Case

Appendix 3. Interview Sampling Frame

Appendix 4. Gathering and Coding of Newspaper Data

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592720002443.