Alexander's right-hand man

The Alexander Mosaic from the House of the Faun at Pompeii is perhaps the most famous mosaic surviving from Antiquity, depicting Alexander the Great at the head of a cavalry charge, rushing into combat against Darius III and the Persian army.Footnote 1 Although the mosaic itself is dated to the early 1st c. BCE, it is almost universally held to be a copy of a lost battle painting of the Early Hellenistic period. Considerations in favor of this viewpoint include that the mosaic is executed in the four-color palette associated with the great painters of the 5th and 4th c. BCE; that the central figure scheme appears also on artifacts that predate the mosaic itself; and that the depicted militaria closely resemble real armor and military equipment of the late 4th c. BCE.

Much scholarship on the mosaic has focused on who commissioned the missing “source painting” on which it was modeled. An important contribution was made by Andreas Rumpf in 1962.Footnote 2 Rumpf fastened attention on a previously little-discussed aspect of the mosaic's iconography: the surviving sliver of a profile face adjacent to Alexander's right arm, belonging to a figure shown standing immediately behind the Macedonian king, his sarissa, and Boukephalas (Figs. 1–2). He recognized that this figure certainly represents a Macedonian and pointed out that “it is no coincidence that he is directly next to Alexander … that he is shown helmetless, and that his facial features are worked through in detail.”Footnote 3 The importance of this “right-hand man” is further suggested by the fact that he fights on foot alongside cavalry in the Macedonian front line. This artificial placement serves to spotlight him in a striking way.

Fig. 1. Detail from the Alexander Mosaic, showing Alexander riding Boukephalas and the right-hand man standing directly at his side. MANN inv. 10020. (© Carole Raddato/Wikimedia Commons. The file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en]).

Fig. 2. Detail from the Alexander Mosaic, showing the right-hand man's portrait. MANN inv. 10020. (© Carole Raddato/Wikimedia Commons. The file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en]. Photo cropped by author.)

Rumpf identified the right-hand man as the patron of the missing source painting, who fought alongside Alexander at the represented battle, and who, at a later stage, wished to emphasize his special relationship with the king. These conditions best suit one of the protagonists in the power struggle that followed Alexander's death: a figure with the standing of Ptolemy I Soter, Seleukos I Nikator, or Lysimachos. Rumpf tentatively proposed, on iconographic grounds, that the figure might represent Ptolemy.

While several later studies agreed with Rumpf concerning the importance of the right-hand man, most were reluctant to address the question of his identity. An exception was Michel Pfrommer's monograph on the mosaic, published in 1998. Pfrommer likewise suggested that the source painting originated in a Ptolemaic milieu, and entertained the idea that the right-hand man might represent Ptolemy.Footnote 4 But he also argued that the painting was produced in a late 3rd- or 2nd-c. BCE context, and that it served as an allegory for Ptolemaic victories over the Seleukids in the Syrian Wars. This later chronology for the source painting has found few followers, with the result that some of Pfrommer's other important observations concerning the mosaic have been overlooked.

A different conclusion was reached by Bernard Andreae in 2004.Footnote 5 Andreae agreed with Rumpf on the importance of Alexander's right-hand man, even stating that “the longer one thinks about it, the less one can avoid identifying this foot-soldier as the true protagonist of the entire picture.”Footnote 6 This assessment was again founded on the figure's sharp portrait physiognomy, his proximity to Alexander, and his important role within the battle narrative. Unlike Rumpf, however, Andreae doubted that this figure represented Ptolemy. Rather, he presented a series of iconographic and historical observations to identify the figure as Seleukos I Nikator, and proposed that this king might have commissioned the source painting following the Battle of Ipsos in 301 BCE.

In what follows, the right-hand man's identity will be re-evaluated. After a discussion of methodology, we will see that both Ptolemy and Seleukos are credible candidates from an iconographic point of view. The discussion will then highlight some points of intersection between the mosaic's iconography and our surviving textual accounts of the great pitched battles between Alexander and Darius. These points of intersection seem to hinge on the History of Alexander's campaigns composed by Kleitarchos of Alexandria, who worked at the Ptolemaic court. Attention will then turn to the mosaic's display context in the House of the Faun, which offers circumstantial support for the notion of Ptolemaic origins.

Methodology

Any attempt to identify the right-hand man should be set against previous attempts to identify particular figures in works of art associated with the era of Alexander and his successors. Several approaches have been employed in this context, sometimes with contested results. It will be useful to reflect briefly on these approaches, before outlining the method to be followed here.

A first approach involves connecting a work of art to a composition recorded in our surviving texts. An example is Michael Donderer's reading of a Roman mosaic from Sétif in Algeria depicting Meleager, Atalanta, and two companions hunting the Calydonian Boar.Footnote 7 Donderer suggested that this mosaic may be a copy of the painting of Ptolemy hunting by Antiphilos of Naukratis, mentioned briefly by Pliny the Elder.Footnote 8 According to this interpretation, Antiphilos chose to depict Ptolemy I Soter as Meleager, elevating the theme of the royal hunt to a heroic level. There are, however, difficulties with Donderer's reading. From a textual perspective, Pliny's two-word account of Antiphilos's painting is surely too brief to establish a firm connection with the mosaic. And, from an iconographic standpoint, the subject of the mosaic seems mythological. As Michèle Blanchard-Lemée has argued, the mosaic should probably be dissociated from Antiphilos's painting.Footnote 9

A similar approach has often been applied to the Alexander Mosaic. Indeed, the composition is routinely identified as a copy of an Early Hellenistic court painting mentioned by Pliny the Elder: the battle of Alexander against Darius painted by Philoxenos of Eretria for King Kassandros of Macedonia.Footnote 10 Again, however, the association is problematic. We have seen already that the right-hand man may be the patron of the source painting, who wished to commemorate his own involvement in Alexander's campaigns. This would rule out Kassandros, since he did not take part in the Persian expedition. Furthermore, Pliny's four-word description of Philoxenos's painting is again too brief to permit a connection with the mosaic, especially since two further paintings with similar subject matter are attested: a battle against the Persians painted by Aristeides of Thebes for Mnason of Elateia, mentioned also by Pliny;Footnote 11 and a Battle of Issos by Helen of Egypt, mentioned by Ptolemaios Chennos.Footnote 12 The dangers of associating the Alexander Mosaic with any one of these paintings over the others should be self-evident.

Different criteria have been used to identify figures in the painted frieze of Tomb II at Vergina, an original masterpiece of the 4th c. BCE.Footnote 13 This composition depicts a group of 10 hunters and their dogs pursuing quarry in a (mostly) wild landscape. A hierarchy among the hunters is established by differences in costume, equipment, and the role that each plays in the hunt. Two lion-hunters have usually been identified as protagonists: the youthful rider in the center of the frieze and the bearded rider to the right of the lion readying his attack. Still, there remains no consensus concerning their specific identities. This lack of consensus is bound up with the broader controversy concerning the date of the tomb, and whether it was constructed for Philip II (assassinated in 336 BCE) or for Philip III Arrhidaios (d. 317 BCE). The bearded rider has been identified as Philip II or as Arrhidaios, while the younger rider has been identified variously as Alexander the Great, Arrhidaios, Kassandros, or Alexander IV.Footnote 14 As will be clear from these competing interpretations, neither rider can be identified on objective grounds.

It is because of these difficulties that some commentators have approached the frieze from new directions. Particularly notable are studies by Ada Cohen and Hallie Franks.Footnote 15 Both authors refuse to be drawn into questions such as the date of the tomb, the identity of the tomb occupants, or the precise identities of the hunters depicted in the frieze. Instead they demonstrate how the composition reflects the importance of communal hunting in elite Macedonian identity, irrespective of the precise personalities involved.

Given that this approach has been applied so productively to the Vergina frieze, any attempt to identify specific figures in the Alexander Mosaic might risk seeming démodé. There are, however, important differences between these compositions that justify the continued search for historical detail in the mosaic. We have seen already that none of the figures in the Vergina frieze can be identified with confidence, whereas Alexander and Darius are recognizable in the mosaic. This brings us to a second difference, which concerns the historicity of the represented events. In the case of the Vergina frieze, it remains unclear whether a real, historical hunt is shown. Several factors contribute to this uncertainty, not least the nudity of many of the hunters. By contrast, a much stronger case can be made that the Alexander Mosaic depicts one of the great pitched battles during the Macedonian conquest of the Persian Empire. This is not to suggest that the composition aims at “factual” documentation of a specific battle in the manner of, say, a modern photograph. Rather, we should follow Tonio Hölscher in supposing that it reproduces the “conceptual reality” of the battle concerned.Footnote 16 According to this view, the mosaic combines references to a specific historical event with broader ideological concerns and iconographic conventions borrowed from earlier Greek art. It is because of this comparatively tight historical context that questions of identification may be posed with the possibility of productive results.Footnote 17

The continued value of this line of enquiry is demonstrated by William Wootton's analysis of a mosaic from Palermo.Footnote 18 This composition is likewise a later copy of an earlier court painting, and depicts a hunt featuring a protagonist on horseback aiming his spear at a lion. Whereas this lion-hunter had previously been identified as Krateros,Footnote 19 Wootton argued for Alexander the Great.Footnote 20 From an iconographic perspective, the key is the off-center anastolē in the hunter's hair, recalling this aspect of Alexander's appearance. Further support is offered by the inclusion of a Persian hunter, since references to Persians at court are most frequent during Alexander's reign. The following examination of the right-hand man will progress according to a similar logic, focusing first on iconographic and then on broader historical and contextual considerations.

The right-hand man's portrait

We may first consider the right-hand man's portrait in detail (Fig. 2). The figure wears a deep red kausia – the Macedonian national cap – on his head, and a pale red chlamys – a garment associated with hunting and warfare – around his shoulders. His face is not quite in full profile, since his left eyebrow, eyelid, and eyelashes are partly visible, but we still receive a strong impression of his distinctive physiognomy. His prominent nose has a slightly curving ridge ending in a straight tip. Beneath, he has a remarkably expressive mouth, with thick red lips slightly parted and turned down at the corners. In Hellenistic portrait vocabulary, this kind of mouth expressed positive qualities like energy, sympathy, and concern.Footnote 21 A pocket of shadow beneath the lower lip suggests a prominent chin. The chin itself and the upper lip are rendered in darker tesserae than the nose, indicating a light growth of stubble. This is the five o'clock shadow of the tireless campaigner whose commitment to his military responsibilities means that he has no time to shave.

Both Rumpf and Andreae attempted to identify the figure through comparison with Hellenistic royal portraits surviving in other media. Rumpf stated simply: “maybe I am wrong, but it [the portrait] reminds me of the coins of Ptolemy Soter.”Footnote 22 Andreae, meanwhile, identified the figure as Seleukos based on comparisons with the bronze bust from the Villa of the Papyri and posthumous coin portraits minted by Philetairos of Pergamon. For Andreae, these portraits all share the same profile, seen most clearly in the shape of the nose, the form of the mouth, and the prominence of the chin.Footnote 23

While these physiognomic similarities are interesting, they are insufficient to support a firm identification of the right-hand man. This is because the figure's portrait is not typologically connected to any of our surviving portraits of either Ptolemy I Soter or Seleukos I Nikator, in the sense of both being versions of the same original portrait type. That is, the portraits do not share a sufficient number of closely observed physiognomic details to indicate that they certainly represent the same person.Footnote 24 Still, this need not contradict the notion that the right-hand man represents a known historical figure. After all, Alexander's own appearance in the mosaic differs sharply both from his posthumous coin portraits and from the late 4th-c. and early 3rd-c. BCE sculpted portraits surviving in the Roman copy record.

There is, then, no secure, scientific basis for identifying the right-hand man on iconographic grounds alone. The most we can say is that this figure's mature, militaristic physiognomy would have been well suited to the representation of an experienced campaigner such as Ptolemy or Seleukos.

The Alexander Mosaic, Ptolemy, and Kleitarchos

The only other internal evidence that bears on the right-hand man's identity is the wider battle narrative of the scene. Those who agree that the composition refers to a specific battle have favored two possibilities: Issos in 333 BCE or Gaugamela in 331 BCE. Both readings depend, to a large extent, on the ancient textual tradition surrounding these battles. While I find the interpretation as Issos more compelling, I do not wish to reopen the debate.Footnote 25 Rather, it will be useful here to highlight some striking connections between the right-hand man, the ancient texts describing Alexander's victories over Darius, and the account of Alexander's campaigns composed by Kleitarchos of Alexandria – a historian linked to the Ptolemaic court.

As the patron of the source painting, the right-hand man surely claimed to have fought directly alongside Alexander at whichever battle was represented in the composition. It may then be useful to search our textual accounts for evidence of such a claim. In the case of Seleukos, the search yields nothing: he is not mentioned by name in the accounts of Issos or Gaugamela, and appears in our histories only in 326 BCE, serving as commander of the Royal Hypaspists at the Battle of the Hydaspes.Footnote 26 The silence of the texts does not mean that Seleukos did not take part at Issos and Gaugamela, or that he could not claim at a later stage to have charged against Darius as Alexander's loyal wingman. It means simply that there is no hint of such a tradition in our sources. By contrast, we can be certain that Ptolemy actively claimed to have fought directly alongside Alexander at Issos.Footnote 27 This information is contained in Arrian's account of the battle's denouement:

Those of the Persians who died were Arsames, Rheomithres, and Atizytes, who were the leaders of the cavalry at the Granikos. Savakes the satrap of Egypt and Boubakes of the noble Persians also died. There were so many others – around 100,000 died, of which 10,000 were cavalry – that Ptolemy son of Lagos, who was then following together with Alexander [ξυνɛπισπόμɛνος τότɛ Ἀλɛξάνδρωι], says that they and their forces were pursuing Darius and when they came upon a ravine in their pursuit, crossed that ravine over the bodies of the dead.Footnote 28

The source for this passage is certainly Ptolemy's own History of Alexander's campaign, identified by Arrian elsewhere as one of two principal sources for his Anabasis.Footnote 29 That Ptolemy might have exaggerated his own contribution is suggested by the fact that none of the other surviving battle accounts mentions him in any capacity. But his claim to have fought directly alongside Alexander may have implications for the question of the right-hand man's identity, especially if Issos is indeed the represented battle.

There are also interesting connections between the iconography of the mosaic and the History of Alexander's campaigns composed by Kleitarchos of Alexandria. These emerge when we consider the battle narratives preserved in the so-called vulgate tradition, specifically the descriptions of Issos composed by Diodorus Siculus and Quintus Curtius Rufus, and Plutarch's account of Gaugamela.Footnote 30 These highly rhetorical battle narratives all work up the theme of Alexander's personal aristeia to maximum effect, and all incorporate a consistent and memorable set of rhetorical topoi. It has long been recognized that a striking number of these topoi find close visual analogues in the mosaic, and in the present context it will suffice to highlight just two key examples. First, Curtius's vivid description of Oxathres and other Persians positioning themselves between Darius and Alexander before being “slain by a noble death before the eyes of their king” intersects closely with the mosaic. Here we see two Persians throwing themselves in front of Darius's chariot: the nobleman dressed in yellow being skewered by Alexander, and a mounted Persian with a white headband around his headdress. Second, Curtius's reference to Darius escaping from the battlefield on “a horse that followed for that very purpose” explains the boldly foreshortened horse in rear view controlled by a dismounted Persian soldier on the mosaic. This is the spare horse that Darius will use to escape.

Such correspondences do not presuppose a direct relationship between the source painting and our texts, in the sense of one being modeled directly on the other. Rather, they indicate that both the source painting and these textual accounts drew from a common rhetorical tradition concerning Alexander's epochal encounter(s) with Darius. This notion of a common rhetorical tradition is well established in scholarship on the mosaic.Footnote 31 Less often discussed, in the specific context of the mosaic, are the conclusions that emerge from Quellenforschung of the texts preserving the tradition. Indeed, it may be significant that Diodoros's account of the central episode at Issos, Curtius's account of the central episode at Issos, and Plutarch's account of the central episode at Gaugamela are all thought to depend on Kleitarchos's History.Footnote 32

Until recently, it was almost universally held that Kleitarchos wrote in the generation or so following Alexander's campaigns: that is, during the late 4th or very early 3rd c. BCE. This orthodoxy has been challenged by the publication of a 1st- or 2nd-c. CE papyrus text from Oxyrhynchus (P.Oxy 4808), concerning Hellenistic historians.Footnote 33 The section on Kleitarchos records that this author served as royal tutor to Ptolemy IV Philopator (born ca. 244 BCE). If this is true, of course, Kleitarchos's History should be down-dated to the mid-3rd c. But other sources place Kleitarchos in the Early Hellenistic period,Footnote 34 and so some commentators have been reluctant to accept a lower date. It has been suggested, for instance, that the author of P.Oxy 4808 was simply mistaken;Footnote 35 that he accidentally conflated two Kleitarchoi;Footnote 36 or that Kleitarchos was actually tutor to an earlier Ptolemaic king.Footnote 37 Less controversial is where Kleitarchos composed his History, since other sources tie him to Alexandria.Footnote 38

It is surely because of this Alexandrian connection that Kleitarchos reserved special praise for Ptolemy in his History, even if his version of events did not always correspond with the version presented by Ptolemy himself.Footnote 39 Representative is Diodoros's description of Ptolemy's near-death experience when wounded by an arrow at Harmatelia in India, which certainly depends on Kleitarchos. Here we read that, “He [Ptolemy] was loved by all because of his character and his kindnesses to all, and he obtained a succor appropriate to his good deeds.”Footnote 40 It would be interesting to know whether Kleitarchos enjoyed the direct patronage of a Ptolemaic king, as P.Oxy 4808 clearly suggests.

Viewed together, these three things – the common rhetorical tradition encompassed by the source painting and Kleitarchos's History, Kleitarchos's connections with Ptolemaic Alexandria, and his positive presentation of Ptolemy – support the view that the source painting might have been connected with Alexandria. Further support is supplied by the decoration of the House of the Faun, to which we may now turn.

Ptolemaic connections in the House of the Faun

At first sight, it might seem difficult to envisage what the Alexander Mosaic's display context in the House of the Faun can contribute to our assessment of the right-hand man.Footnote 41 After all, this Campanian townhouse was far removed in time and place from the Late Classical or Early Hellenistic milieu in which the source painting was conceived. It is significant, however, that several other mosaics from the house have iconography that can be connected to Alexandria and/or Egypt in some way. The Alexander Mosaic's juxtaposition with these pavements offers important circumstantial evidence for its possible Ptolemaic origins, a conclusion with implications for the identity of the right-hand man. Accordingly, it will be useful to survey briefly these Alexandrian connections.

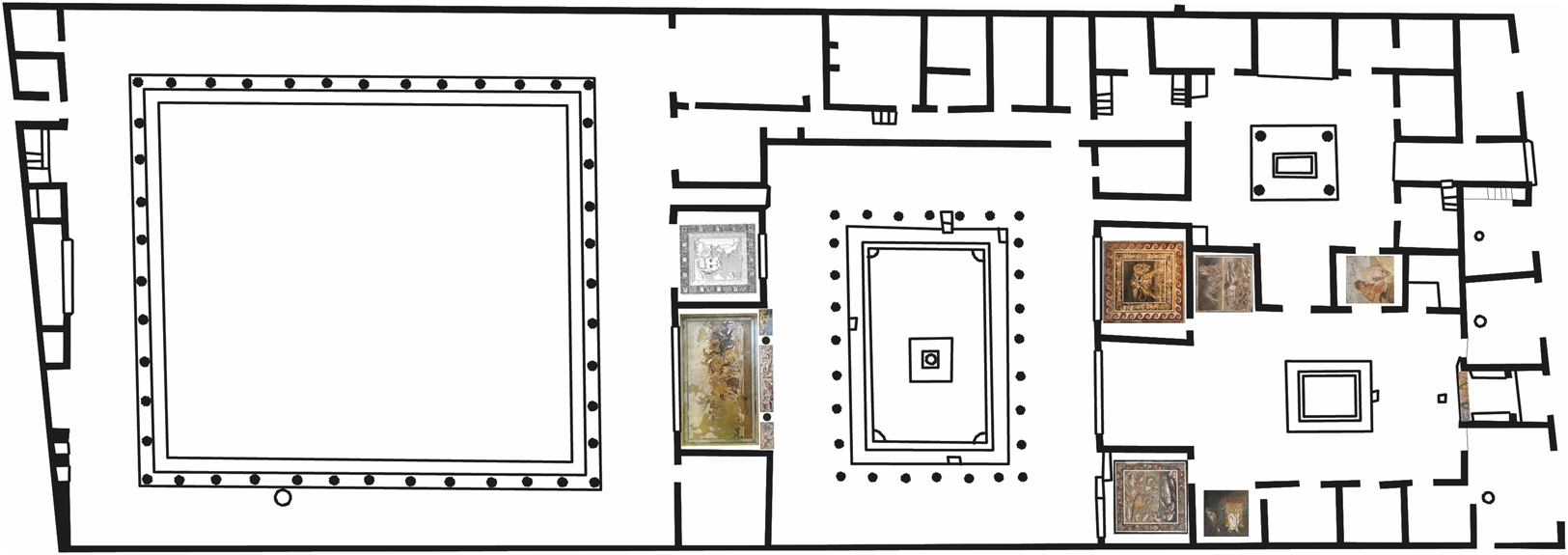

Eight pictorial mosaics were laid in the House of the Faun as part of a major renovation program of the early 1st c. BCE (Fig. 3).Footnote 42 As previous studies have recognized,Footnote 43 several have iconography linking them to Ptolemaic Egypt:

– A mosaic triptych depicting Egyptian animals in a swampy Nilotic landscape (Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli [MANN] inv. 9990) decorated the threshold of the exedra containing the Alexander Mosaic (Fig. 4).Footnote 44 This composition surely carried a specifically Egyptian frame of reference.Footnote 45

– The emblema depicting an erotic encounter between a satyr and nymph laid in cubiculum 17 (MANN inv. 27707) reproduces precisely the same iconographic scheme as an earlier mosaic from Thmuis in the Nile delta (Figs. 5–6).Footnote 46 While it does not automatically follow that this scheme originated in an Egyptian milieu, this is an attractive possibility.

– The fish emblema in triclinium 12 (MANN inv. 9997) is typologically connected to a larger fish mosaic laid in the Antro delle Sorti at Praeneste. A series of iconographic and contextual considerations suggest that the Praeneste mosaic may be a later version of an Alexandrian original. Notably, it formed the sister-piece to the famous Nile Mosaic, decorating the same architectural complex.

– The emblema depicting a cat attacking a bird from ala 15 (Fig. 7; MANN inv. 9993) closely resembles statues with the same theme from Ptolemaic Egypt. As we shall shortly see, recent excavations have shed new light on the significance of this subject in the Ptolemaic kingdom.

– The emblema in triclinium 14 depicting a tiger-riding putto (MANN inv. 9991) recalls limestone sculptures with comparable iconography from the Serapeion at Memphis. Here the case for a specifically Egyptian connection is less clear-cut, since the tiger-rider motif occurs elsewhere, notably on Delos.

Fig. 3. Plan of the House of the Faun, with pictorial mosaics plotted in their original display contexts. (Photo montage by author, using a plan by Johannes Eber).

Fig. 4. Watercolor reproduction of the floor decoration of exedra 29 of the House of the Faun, featuring the Alexander Mosaic and the Nilotic triptych. (Mazois Reference Mazois1838, pl. 48.)

Fig. 5. Symplegma mosaic from cubiculum 17 of the House of the Faun, h. 39.0 cm, w. 37.0 cm. MANN, inv. 27707. (© Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons.)

Fig. 6. Symplegma mosaic from Thmuis (Tell Timai) in the Nile delta. Central panel h. 82.5 cm, w. 84.5 cm. Alexandria, Graeco-Roman Museum, inv. 21738. (Photograph: André Pelle, © CEAlex Archives.)

Fig. 7. Emblema from ala 15 of the House of the Faun, with split-level composition including the cat-and-bird motif, h. 51.0 cm, w. 57.0 cm. MANN, inv. 9993. (© Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons.)

An Alexandrian origin has also been envisaged for the bronze statue of a dancing satyr that stood in the property's Tuscan atrium, based on comparison with another bronze satyr said to be from Tanis in the northeast Nile delta.Footnote 47

It does not necessarily follow, of course, that all these compositions were understood in explicitly “Alexandrian” or “Egyptian” terms by viewers in the House of the Faun. Rather, we should be careful to distinguish between the “true” geographical origins of the motifs on the one hand, and the cultural associations that they carried for Italian viewers on the other. These may not have been identical.Footnote 48 Even so, it will be useful here to present three further observations that lend support to the notion of an Alexandrian connection in the house. Two stem from recent archaeological research in Pompeii and the Nile delta. The third concerns an important find from the house that has often been overlooked.

Exedra 29 and the Nilotic triptych

The Alexander Mosaic was laid in exedra 29, a large room opening off the north wing of the house's southern peristyle. As noted above, a second opus vermiculatum composition decorated the exedra's threshold: a triptych depicting Egyptian fauna in a Nilotic landscape (Fig. 3).Footnote 49 It has traditionally been held that these compositions were laid at different times, the Alexander Mosaic in ca. 110 BCE and the Nilotic triptych in ca. 80 BCE.Footnote 50 This view rests on the observation that the bases of the threshold columns were cut back to accommodate the panels of the triptych, and on a perception that the triptych is technically less accomplished than the Alexander Mosaic.

This relative chronology was cast into doubt by Faber and Hoffmann's reassessment of the house's stratigraphy, which showed that there is no hard archaeological data to suggest that the mosaics were laid at different times. The authors ask, “what kind of demanding and apparently economically highly potent client would have waited three decades for the completion of his project?”Footnote 51 It is therefore likely that the mosaics were contemporary. We might imagine that the column bases were cut back simply because the triptych panels did not quite fit the available space. The stylistic and technical differences between the mosaics would then be determined not by a difference in chronology but by other factors: the available budget for each pavement, the technical ability of the mosaicists, the quality of the artists’ models, and so on.

That the Alexander Mosaic and the Nilotic triptych were laid in the same room at the same time opens up the possibility that they were conceptually related in some way. It has been suggested recently that the triptych functioned in broad terms as “a geographic marker recalling Alexander's conquests.”Footnote 52 This is possible, but we should also entertain the prospect of a more direct connection, focused specifically on Ptolemaic Egypt.

The cat-and-bird emblema and the Alexandrian Boubasteion

The emblema from ala 15 stands out thanks to its unusual two-level composition (Fig. 7). The upper level depicts a cat pinning down a chicken with its left paw. This design was certainly borrowed from a lost archetype, since other mosaics with the same scheme have been found in Rome, Veii, Capri, Ampurias, and elsewhere.Footnote 53 The lower level depicts a still-life scene featuring two ducks (one with an Egyptian lotus in its beak), four passerines, and a selection of fish and shellfish. It may represent a well-stocked larder.

The cat-and-bird theme had a long pedigree in ancient visual culture, with examples surviving from Dynastic Egypt, Minoan Crete, Mycenaean Greece, and Etruscan Italy.Footnote 54 There are, however, strong grounds for supposing that the motif developed specifically Egyptian associations during Hellenistic times. Indeed, the House of the Faun emblema has often been compared to a marble cat-and-bird statue in the Cairo Museum, bought at Damanhur in the western Nile delta in 1895.Footnote 55 Recent research has demonstrated that this was one of seven marble cats found during illicit excavations at Naukratis in the 19th c. (another is illustrated in Fig. 8), and that further cat statues made from limestone and sandstone were excavated at the same time.Footnote 56 Among the finds was a base for a cat statue carrying a dedication to the goddess Boubastis,Footnote 57 the Hellenized version of the Egyptian cat goddess Bastet.

Fig. 8. Marble statue of a cat attacking a bird. Probably excavated in the Boubasteion at Naukratis, h. 23.0 cm, w. 12.0 cm, l. 49.5 cm. British Museum, inv. 1905,0612.5. (© Trustees of the British Museum.)

Our knowledge of Boubastis in Hellenistic Egypt has been enhanced by the discovery of the Alexandrian Boubasteion during rescue excavations at Kom-el-Dikka in 2009–10.Footnote 58 The sanctuary was first founded in the late 4th or early 3rd c. BCE, but a series of six foundation plaques record a major renovation by Berenike II, sister-wife of Ptolemy III Euergetes.Footnote 59 This royal initiative accords well with the Canopus Decree of 238 BCE, which reveals that the Boubasteia was moved to coincide with the Euergesia, a Ptolemaic dynastic festival.Footnote 60 Excavations in the sanctuary uncovered a series of pits containing offerings that had been dedicated to Boubastis prior to burial. Three pits contained limestone and/or terracotta cat statuettes comparable to the examples from Naukratis: one with 50 limestone cats and 469 terracotta cat figurines; another with 106 limestone cats; and a third with 13 limestone cats. Many reproduce the cat-and-bird motif familiar from the House of the Faun emblema, further suggesting a specifically Egyptian connection.

A Hellenistic royal portrait?

A carnelian intaglio decorated with the bust of a male figure was excavated in the House of the Faun on March 4, 1831 (Fig. 9).Footnote 61 The figure has portrait physiognomy and wears a flat hemispherical hat – either a petasos or a kausia – at the back of his head, with long curly locks emerging underneath. He also wears a scaly aegis in the manner of a chlamys, with a pair of serpents forming the upper hem.

Fig. 9. Carnelian intaglio from the House of the Faun, with portrait of royal (?) figure wearing hemi-spherical hat and aegis, h. 2.24 cm, w. 1.71 cm. MANN, inv. 26766. (After Pannuti Reference Pannuti1983, fig. 14. Su concessione del Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali e per il Turismo – Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.)

Although the figure does not wear a diadem, the combination of long hair, portrait features and aegis brings to mind Hellenistic royal portraiture – and especially Ptolemaic portraiture, since the aegis was an indicator of power favored particularly by the Ptolemies in Hellenistic times.Footnote 62 In addition to numismatic representations, we are reminded of the royal portraits found among the clay seal impressions at Edfu and Nea Paphos, several of which depict Ptolemaic rulers wearing the aegis together with a kausia pushed to the back of the head to accommodate a diadem just below (the so-called kausia diadēmatophoros; Figs. 10–11).Footnote 63 In the absence of a diadem, of course, any identification of the House of the Faun gem as a royal portrait remains conjectural. But given this possible royal connection, it is notable that intaglios were sometimes used in diplomatic exchanges between East and West in the Later Hellenistic period. For example, Plutarch records that Ptolemy IX Soter II presented a gold ring set with an emerald bearing his own portrait to L. Licinius Lucullus in 85 BCE.Footnote 64

Fig. 10. Clay seal impression from Edfu, depicting Ptolemy I Soter wearing kausia, diadem, and aegis. Allard Pierson Museum, inv. 8177-230. (Photo Allard Pierson – the Collections of the University of Amsterdam.)

Fig. 11. Clay seal impression from Edfu, depicting a Late Ptolemaic ruler wearing kausia, diadem, and aegis, h. 1.40 cm, w. 1.30 cm. Royal Ontario Museum, inv. 906.12.68. (Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum, © ROM.)

The Ptolemy Painting?

The right-hand man in the Alexander Mosaic may never be identified with certainty. We have seen, however, that Ptolemy I Soter is a particularly attractive candidate, for three reasons. First, Ptolemy claimed to have fought directly alongside Alexander during at least one of his famous pitched battles against Darius. Second, the Alexander Mosaic – and so the source painting – incorporates many of the same rhetorical topoi as the History of Alexander's campaign written by Kleitarchos of Alexandria, who was connected to the Ptolemaic court. Third, several other works of art from the House of the Faun have Alexandrian and Egyptian connections. If this hypothesis is correct, the original “Ptolemy Painting” would have formed part of the extensive posthumous commemoration of Alexander orchestrated by Ptolemy I Soter.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Bert Smith for his feedback on an earlier draft, and to Catharine Lorber, Branko van Oppen de Ruiter, and Stelios Ieremias for helpful comments on iconographic matters. I would also like to thank two anonymous readers for their invaluable input.