Introduction

Tonsillectomy is a common operation performed on a paediatric population by Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) surgeons across different stages of training. Cold dissection remains a frequently used technique. The National Prospective Tonsillectomy Audit in 2005 recommended that trainee surgeons should develop expertise in using cold dissection techniques to perform tonsillectomies.1 Part of this technique includes tying ligatures to achieve homeostasis at the inferior pole of the tonsils. This is a technically challenging skill to learn, particularly in younger paediatric patients, given the more restricted anatomy.

The use of simulators in ENT surgery has long been a valuable adjunct in the training of surgeons. Simulators enable trainees to develop surgical skills independently from clinical practice in a safe and well-controlled environment.Reference Duodu and Lesser2 Recently, the simulated environment has been utilised more frequently to combat the effect of the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic on training, which highlighted the need for low-cost and easily available simulators.

Several tonsillectomy tie simulators, with simulated tonsils which can be tied off and removed, have been designed and published.Reference Duodu and Lesser2–Reference Wasson, De Zoysa and Stephens7 Low-fidelity models have been described that can be constructed using easily accessible supplies such as a tissue box, a shoe, or plastic tubes with gauze. However, it is not known if the dimensions of these simulators are accurate, which detracts significantly from their realism and decreases their educational value. Only one published paper has attempted to provide a recommended size for the simulating model based on the distance from the incisor teeth to the lower tonsil pole from actual patients.Reference Street, Beech and Jennings6 The sample size of this study was small, and the data were taken from adult patients.

The aim of this study is to measure the distance from the midline of the upper incisors to the lower pole of the tonsils in paediatric patients of varying ages. This will enable the design of accurately sized simulators for ligating the lower tonsillar pole in the paediatric population.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This is a prospective observational study. The participants were recruited from patients who had been listed to undergo a tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy. We adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for reporting observational studies as closely as possible. This study was conducted by the ENT department at Alder Hey Children's Hospital, Liverpool, UK.

Participants

The patients were recruited by purposive sampling. All participants between 1 year and 16 years old (including the day of their 16th birthday) who had been referred to the ENT department for the management of a condition for which tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy was the preferred management option were invited to be included. The patients were presented with the possibility of participating in this study after consent for the operation was completed and they fulfilled the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The following criteria were used to evaluate patients for inclusion in the study: (1) patients or patients with parents able to give consent; (2) patients who were fit for general anaesthesia; and (3) patients suffering from recurrent tonsillitis, which requires elective bilateral tonsillectomy, or patients suffering from a recurrent peritonsillar abscess (‘quinsy’), which requires elective bilateral tonsillectomy, or patients suffering from sleep disordered breathing symptoms justifying an elective bilateral tonsillectomy.

The following criteria were used to determine exclusion of patients in the study: (1) patients with congenital or acquired oral defects, anatomical abnormalities or both; (2) patients undergoing tonsillectomy as an emergency; (3) patients undergoing tonsillectomy for a suspected malignancy; (4) patients undergoing unilateral tonsillectomy; and (5) patients undergoing intracapsular tonsillectomy

The participants, 100 females and 100 males, were recruited to ensure a reasonable spread of ages and gender. The participants were followed up as per the standard follow-up policy for tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy. There was no additional follow up relating to the study.

Main outcome measures

Measurements took place following general anaesthesia and at the end of the planned operation. A blunt dissecting instrument was placed between the upper front teeth and the lower tonsillar pole to measure the distance from the midline of the upper teeth to the lower extremity of the tonsils. The distance between these two points was marked with a disposable pen and then measured with a disposable paper ruler. The measurement was repeated for the opposite tonsil.

Data management and analysis

The data collected included the participant's age (digitalised), gender, the distance from the midline between the upper incisors to the left lower tonsillar pole, and the distance from the midline between the upper incisors to the right lower tonsillar pole. Data were anonymised and entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet which was stored on a password-protected file on a local drive of a National Health Service computer within Alder Hey Children's Hospital. The data were plotted in a scatter plot and the line of best fit was calculated using Microsoft Excel.

Ethical considerations

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the national and institutional guidelines on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. This study was approved by the North West – Greater Manchester Central Research Ethics Committee (REC reference: 18/NW/0864). Identification of patients suitable for inclusion in the study occurred when the participants were referred to the ENT outpatient clinic. If a tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy operation was indicated, patients and their parents were invited to participate in this study. They were given information about the study at that stage so that informed consent for participation could be given. There was a wait of at least two weeks before the patients had their operation, which allowed time for them and their families to further consider the information given. On the day of the operation, researchers confirmed consent to participate in the study. Participants could withdraw at any point.

Safety considerations

Patients participating in this study were listed for a tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy under a general anaesthetic. The main risk of participating in this study was that the patients remained under general anaesthesia for approximately 1 minute longer than if not involved in the study to allow for the measurements to be taken. Additional risk to the participants beyond the tonsillectomy or adenotonsillectomy procedure risk was minimal. Patients and parents/legal guardians were informed of this prior to the procedure. High-risk (emergency) or complex (oral defects/anatomical abnormalities) patients were excluded to minimise potential risk.

Results

Patient demographics

Two hundred participants (100 male and 100 female) were recruited for this study. The ages of the participants ranged from 2 to 16 years. The mean digitalised age for all participants was 6.85 (standard deviation 3.6). The mean digitalised age for the male participants was 6.14 (standard deviation 3.1) years and the mean digitalised age for the female participants was 7.56 (standard deviation 3.9) years. All 200 participants were included in the final analysis of the results.

Main outcome

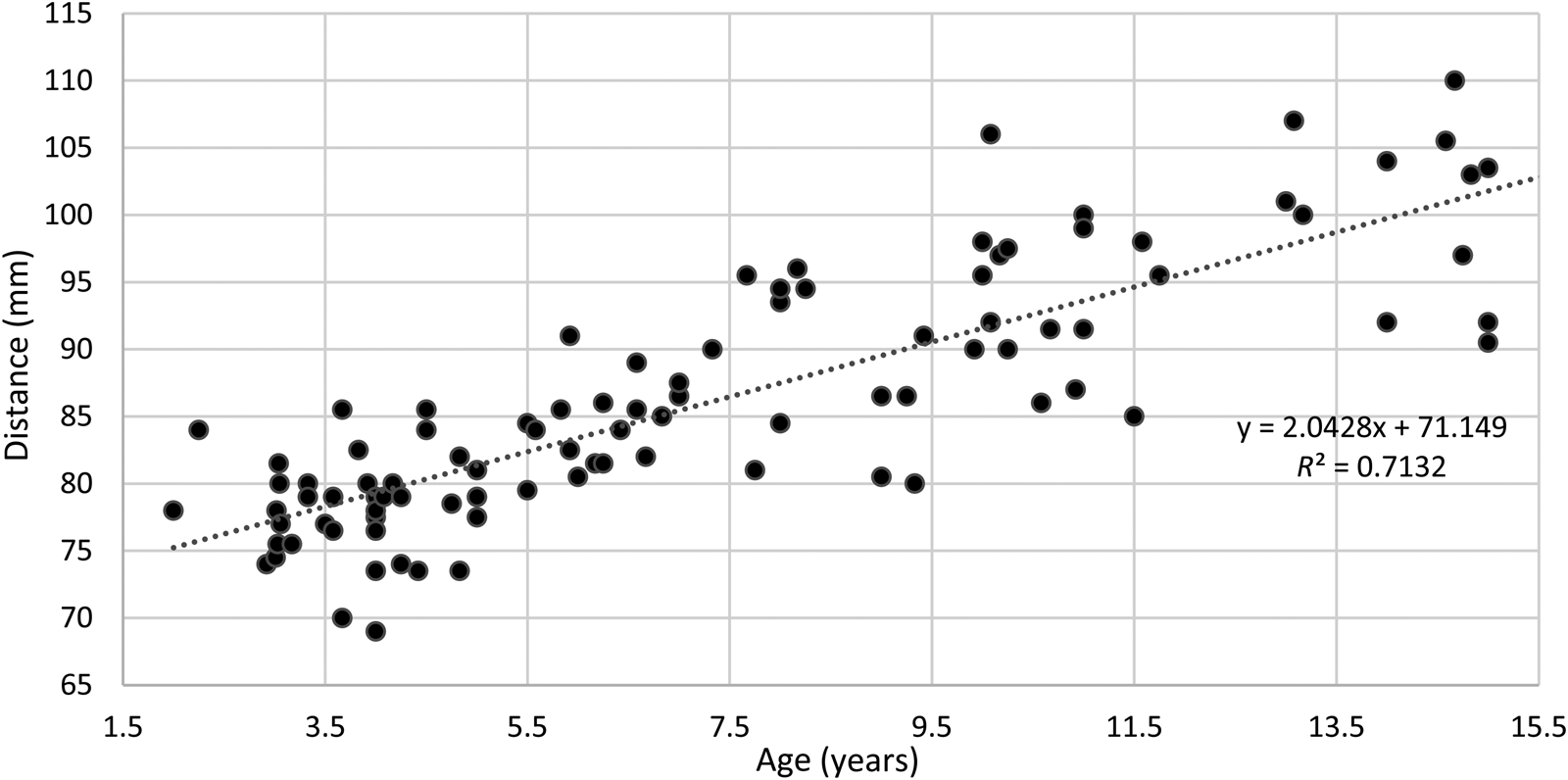

The mean of the distance from the midline between the upper incisors to the left lower tonsillar pole and the right lower tonsillar pole was calculated for each patient. The mean distance was plotted against the participants’ age in a scatter plot (Figure 1). The line of best fit was calculated, and the equation was:

Figure 1. Distance of incisor to inferior tonsillar pole for all participants

The data were further sub-analysed based on the patient's gender and plotted into two scatter plots (male, Figure 2; female, Figure 3). The line of best fit was calculated and the equation for each group was:

Figure 2. Distance of incisor to inferior tonsillar pole for male participants

Figure 3. Distance of incisor to inferior tonsillar pole for female participants

Discussion

This is the first prospective observational study that aims to assist in the design of appropriately sized tonsil tie simulators for paediatric patients by providing actual measurements of the patient's oral/pharyngeal anatomical landmarks. Although several tonsil tie models have been designed and published, the lack of data on the size of the oral and oropharyngeal anatomy prevents accurate sizing of the simulators. As paediatric patients grow, they have increasingly varying sizes of oropharynx, which is a variable of high importance when designing a realistic simulator. Additionally, specific anatomical considerations within the paediatric population pose greater challenges in performing tonsillectomies compared to adults. These factors encompass reduced mouth opening, a smaller oral cavity and oropharynx, a proportionally larger tongue, and loose teeth, among other considerations.

The distance between the midline of the upper incisors to the lower pole of the tonsil, which has been described by Street et al. in an adult population,Reference Street, Beech and Jennings6 provides a standardised method of measuring the depth of the oral anatomy of patients and can be used to set up simulators by measuring and adjusting those to the corresponding depth. We used the same anatomical landmarks in this study, but in a paediatric population. Using data from 200 patients, we created an equation that can be used to estimate the approximate distance from the midline of the upper incisors to the lower pole of the tonsil in paediatric patients based on their age and gender. This equation can subsequently guide the sizes of tonsil tie simulators to increase their accuracy.

• Ligation of the lower pole of a tonsil is a challenging part of cold dissection tonsillectomy, especially in the paediatric population

• Current tonsil tie simulator models may not be accurately sized since no previous objective anatomical studies have been performed, which distracts significantly from their realism and decreases their educational value

• Based on data obtained from 200 paediatric patients, we created an equation that can be used to predict the distance from the incisor teeth to the lower tonsil pole according to the patient's age

• The data were further analysed based on the patient's gender to create two equations for male and female patients, respectively

• The equations can be used to accurately size tonsil tie simulators and assist the surgical training of ENT trainees

The use of simulators in surgical training has increased in popularity due to reduced training hours, increased clinical pressures, and emphasis on the efficacy of operating theatres which decrease teaching opportunities. Simulation provides a means of progression through the three-stage motor skill acquisition described by Fitts and Posner's theory (cognition, integration, automation) in a controlled environment with no risk to patients.Reference Fitts and Posner8 Reznick et al. suggested that the early stages of surgical training should not take place in the operating theatre until automaticity in the surgical skill is attained.Reference Reznick and MacRae9 This will allow the trainee to focus on more complex aspects of the surgery and reduce intra-operative errors. Studies have demonstrated that the use of low-fidelity simulators were associated with significantly improved operative performance in laparoscopic surgery.Reference Seymour, Gallagher, Roman, O'Brien, Bansal and Andersen10,Reference Grantcharov, Kristiansen, Bendix, Bardram, Rosenberg and Funch-Jensen11 We, therefore, accept that practising tonsil tying on a simulator can result in improved training standards and operating outcomes. Sizing the simulator closely to the actual size of the patient enhances its educational value because it is more representative of the motor skill required during the actual operation.

Low-cost simulators in ENT surgery have been published and summarised by Pankhania et al.Reference Pankhania, Pelly, Bowyer, Shanmugathas and Wali12 Several tonsil tie simulators have been proposed using simple supplies such as a shoe, a box of tissue or a plastic tube, ribbon, and gauze.Reference Duodu and Lesser2–Reference Wasson, De Zoysa and Stephens7 These supplies can be adjusted easily to the measurements described in this study to provide a measurement closer to the actual patient on whom the surgical trainee would likely be operating. Our measurements can also be used by more advanced virtual reality simulators and even extend beyond the scope of tonsil tie simulators.

Conclusion

This is the first study to measure the anatomical distance from the upper incisor teeth to the inferior tonsillar pole in a paediatric population. Based on data obtained from 200 patients we created equations that can be used to predict this distance in male and female patients. The equations can be used to size tonsil tie simulators and assist the surgical training of ENT trainees.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the staff at Alder Hey Children's Hospital for their support and the participants who contributed to this study.

Funding

No external funding was secured for this study.

Competing interests

None of the authors has any financial or other relationship that might lead to a conflict of interest.