Whether governing parties’ election stances influence subsequent policies that are enacted is a traditional question for scholars of democracy (e.g., Keman Reference Keman2002). In fact, at the core of the responsible party model of democracy is the notion that parties should keep their campaign promises. However, do governing parties actually follow through on their platform policy commitments that they campaign with in elections? It has been reported that citizens believe the answer to this question is “no” (Naurin Reference Naurin2009; Thomson Reference Thomson2011), yet existing research on the connection between manifesto promises and government policy does paint a more optimistic picture. An extensive body of empirical work examines whether the policy preferences of citizens ultimately produce government legislative action (e.g., Erikson et al. Reference Erikson, MacKuen and Stimson2002; Kang and Powell Reference Kang and Powell2010; Soroka and Wlezien Reference Soroka and Wlezien2010). In order for the democratic translation of citizen preferences into policy to occur, parties must commit to the policies that they promote during election campaigns (McDonald and Budge Reference McDonald and Budge2005). Numerous country-specific studies have addressed this pledge-fulfillment nexus, e.g., Thomson (Reference Thomson1999) examines the Netherlands while Naurin (2009, Reference Naurin2011) focuses on Sweden. There is also research on the United States (e.g., David Reference David1971; Elling Reference Elling1979), the United Kingdom (e.g., Bara Reference Bara2005), Australia (e.g., Carson et al. Reference Carson, Gibbons and Martin2019) or Spain (e.g., Artés and Bustos Reference Artés and Bustos2008), among many others. Comparative work is less readily available, although exceptions do exist. Naurin et al. (Reference Naurin, Royed and Thomson2019) provide an edited volume on 12 countries, while Thomson et al. (Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017) offer the arguably most comprehensive cross-national investigation covering over 20,000 pledges made in 57 election campaigns in 12 countries. Most of these and related works, including Thomson et al. (Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017), report evidence that parties follow through on their promises and fulfill their campaign pledges.

We focus on whether parties pursue legislative action that meets their electoral campaign emphasis once in power and shed new light on this aspect of the pledge-fulfillment nexus for one of the most salient policy issues of our time, immigration. Specifically, we evaluate whether governing parties that devoted more space to immigration issues in their manifestos subsequently pass more immigration-related legislation (see Money Reference Money and Denemark2010; Abou-Chadi Reference Abou-Chadi2016; Helbling and Kalkum Reference Helbling and Kalkum2018; Böhmelt Reference Böhmelt2019). And, if so, under what conditions is this relationship amplified or weakened? We offer a comparative analysis that examines these aspects of the pledge-fulfillment nexus in the immigration context across 14 Western democracies, which offers wider coverage than a majority of studies that focus on a single country. Several other contributions are given by our work.

First, while there is extensive evidence that parties do follow-up on their campaign promises (e.g., Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017), it seems that the promises considered more important, or more salient to voters, are less likely to be kept. Mellon et al. (Reference Mellon, Prosser, Urban and Feldman2019) analyse the 2017 manifesto of the UK Conservatives and report that about 69% of their promises were met – yet, those issues deemed more salient by the electorate did not turn into policy action. Pertinent to our work, the Conservatives’ promise to reduce net migration to below 100,000 has not been kept. Indeed, migration is one of the most salient current policy issues, with the movement of people across borders having risen significantly over the last few decades. According to the United Nations International Migration Report 2019, the total population of international migrants, i.e., people residing in a country other than their country of birth, has more than doubled since 2000 to about 272 million. The scale of international migration makes it a global phenomenon, and a “fundamental driver of social, economic and political change” (Cornelius and Rosenblum Reference Cornelius and Rosenblum2005, 99) affecting each state worldwide. What is more, migration is consistently seen as one of the most important policy issues in Europe over the past few decades: using Eurobarometer data, Böhmelt et al. (Reference Böhmelt, Bove and Nussio2020) report that migration was perceived as one of the top policy priorities in several European countries since 2003. In the UK, for example, this figure is particularly high with almost 30% (on average in 2003–2017) of the population reporting that it is one of the two most important issues their country faces. With the previously discussed notion in mind that electoral promises on more salient policy issues are less likely to kept, immigration policy merits special attention.

Second, and related to our emphasis on immigration, the question about citizen preferences, governing policies and pledge fulfillment is usually addressed on (traditional) economic issues such as social spending, foreign aid, welfare state generosity or pension reform (Häusermann Reference Häusermann2010; Kang and Powell Reference Kang and Powell2010; Ezrow et al. Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020). Rarely do studies depart from this focus to more specific issue dimensions, although exceptions do exist. For example, Knill et al. (Reference Knill, Debus and Heichel2010) analyse how governing parties’ policy positions influence environmental policies. Here, we extend existing work by examining immigration policy. Ultimately, we can substantiate the theoretical arguments that governing policy pledges on immigration are ultimately reflected in government policies.

Third, we shed light on the conditions that drive whether parties with salient immigration platforms pass more immigration-related legislation. This “complements the saliency approach to the mandate model, in which scholars focus on the relative emphases parties place on different policy themes” (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017, 528). On one hand, we concentrate on the political rights of immigrants. These vary significantly across countries and the type of immigration rhetoric and policy governing parties propose is likely influenced by that. On the other hand, we build on the literature that highlights constraints on policy making (e.g., Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002; Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012; Hellwig Reference Hellwig2015) to evaluate whether a state’s economic performance influences governing parties carrying through their election platforms into policy. We report that economic growth has some conditioning effect, with governments in recession being less able to pass legislative action even if there was a commitment on immigration before. Moreover, the relationship between immigration salience in party manifestos and immigration policy is more strongly pronounced when migration law is rather strict to begin with.

Third, these results have crucial implications for the understanding of the relationships between economic performance, democratic representation and immigration policy making. The conclusion that governing parties, even when it comes to salient issues like migration (see Böhmelt et al. Reference Böhmelt, Bove and Nussio2020), implement policies that mirrors the importance of these issues in their election platforms is crucial for traditional theories of democracy and political representation. In elections, parties present a bundle of policies that citizens may find attractive. Presumably, parties would remain committed to their electoral platforms, but there is not always a widespread belief in the electorate that they do (see, e.g., Naurin Reference Naurin2009; Thomson Reference Thomson2011). Our findings show that governing parties are committed to following through on their election pledges, at least in terms of the number of policies mirroring salience of immigration, which is consistent with previous work in different issue areas (Knill et al. Reference Knill, Debus and Heichel2010; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017). However, we depart from earlier results as we extend the validity of the pledge-fulfillment hypothesis to the salient policy area of immigration that has heretofore been overlooked in the (pledge-fulfillment) literature.

Furthermore, there are several factors that could constrain what governments do. For example, Tsebelis’s (Reference Tsebelis2002) veto players framework suggests that political institutions facilitating power sharing may make it difficult for any government to arrive at decisive policy changes (see also Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017).Footnote 1 Here, we follow more recent research on how economic performance shapes the policies that governments can or cannot implement. In particular, Ezrow et al. (Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020) argue and present empirical evidence that governing parties are not as systematically responsive to public opinion on welfare state generosity when economies are in recession. Hence, there are several factors, relating to constraints that could throw off whether administrations follow through on their policy commitments in election campaigns. And, indeed, we find that economic performance as well as the restrictiveness of a country’s immigration policy regime matter in this regard.

Finally, our work has key implications for understanding how immigration policies are implemented across Europe. Leaving a country to live in another state abroad is determined by multiple forces (for overviews, see, e.g., Cornelius and Rosenblum Reference Cornelius and Rosenblum2005; Breunig et al. Reference Breunig, Cao and Luedtke2012) and permanently moving to another state that offers valuable gains for both migrants and their host societies (see, e.g., Cornelius and Rosenblum Reference Cornelius and Rosenblum2005, 103f; Dustmann and Frattini Reference Dustmann and Frattini2014; Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hangartner and Pietrantuono2017). However, governments can also experience a number of challenges related to the supply of goods and services when trying to manage large population inflows, and citizens may prefer policies or instruments for administrations to regulate migration against this background. Examining whether governing parties that have spent more attention to immigration in their manifestos subsequently pass more immigration-related legislation sheds new light on what we know of the drivers behind these immigration policies.

Immigration salience in party manifestos and legislative action

Do governing parties’ campaign pledges on immigration influence legislative action? Our expectations follow from the tradition that the partisanship of government matters. In particular, parties may be policy-, office- or vote-seeking (Müller and Strøm Reference Müller and Strøm1999). If they are indeed policy-seeking, we would expect that the policies parties promote during election campaigns and in their manifestos will be the same policies that they attempt to implement if they join the government. This expectation also remains valid when assuming parties to be office- or vote-seeking (see also Böhmelt et al. Reference Böhmelt, Ezrow, Lehrer and Ward2016, Reference Böhmelt, Ezrow, Lehrer, Schleiter and Ward2017), since they ought to be concerned with implementing the policies on which they campaigned (Downs Reference Downs1957). In fact, Karreth et al. (Reference Karreth, Polk and Allen2013) show that parties moderating their positions by moving away from their core supporters may gain votes in the short-term (see also Adams and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams and Somer-Topcu2009), but then lose votes under longer time horizons. Hence, short-term changes in policy are met with long-term reputational and vote losses (see also Alvarez Reference Alvarez1998). As a result, while in government, parties that are policy-, office- or vote-seeking, ceteris paribus, are expected to emphasise the same issues they focused on in their campaigns.

The underlying mechanism for this claim can be illustrated via the procedures of leader selection and gaining political power, which incentivise democratic governments to respond to constituents’ needs (e.g., Bueno de Mesquita et al. Reference Bueno de Mesquita, Smith, Morrow and Siverson2005). Democratic executives can be removed more easily from office than their nondemocratic counterparts due to, e.g., regular elections, and the electoral turnover constrains democratic governments’ policy choices (Breunig et al. Reference Breunig, Cao and Luedtke2012, 830). Democratic administrations thus have more incentives than others to implement policies that favour their voters (Dahl Reference Dahl1971; see also Breunig et al. Reference Breunig, Cao and Luedtke2012). Democratic ideals suggest that citizens influence politics via multiple channels including casting their vote in elections. Politicians then choose their policies accordingly to maximise chances to do well in the next election, and for governing parties this means implementing what they have promised in their campaigns. This leads to the outcome that politicians will adopt policy platforms that are closer to the ideal policies of the public (Downs Reference Downs1957; see also Ezrow Reference Ezrow2010) and for governing parties to strive for a stronger match between their campaign pledges and their legislative actions once in power.

Evidence for the responsiveness of democratic governments to voters’ demands does exist (e.g., Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004). Previous research has also shown that pledge fulfillment is given for “bread and butter issues,” that governing parties do produce polices that are consistent with their platforms generally for the left-right dimension (McDonald and Budge Reference McDonald and Budge2005), fiscal policies (Blais et al. Reference Blais, Blake and Dion1993; Bräuninger Reference Bräuninger2005), social policies (Hicks and Swank Reference Hicks and Swank1992; Huber et al. Reference Huber, Rueschemeyer and Stephens1993) and the environment (Knill et al. Reference Knill, Debus and Heichel2010). Although Mellon et al. (Reference Mellon, Prosser, Urban and Feldman2019) report that particularly salient issues are not characterised by pledge fulfillment (see also Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017), our considerations about parties’ reputational concerns and incentives for governing parties in democracies to keep their promises (see also Böhmelt Reference Böhmelt2019) lead us to formulate the following hypothesis:Footnote 2

Pledge-fulfillment hypothesis

Legislative policy action on immigration will reflect the emphasis on immigration in governing parties’ election manifestos.

The literature also suggests that pledge fulfillment does not remain constant across contexts and, in turn, points to the possibility that political rights would condition the pledge-to-policy effect. For example, the political rights of immigrants vary across countries (e.g., Helbling and Kalkum Reference Helbling and Kalkum2018). Where immigrants are treated more equally and they have more rights, they may be more politically active because the opportunity structures are more permissive for political participation in this context (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1986). Just and Anderson (Reference Just and Anderson2014) analyse the political participation of immigrants in 25 countries and report that immigrants are more likely to be politically active where the public opinion climate favours them. However, this political action only extends to unconventional modes of political participation. Subscribing to this political rights dynamic, politicians protecting political rights would be more likely to carry through pledges on immigration as they anticipate that immigrants will become politically active if campaign pledges are ignored.

By contrast, the immigration issue is more salient in countries that have failed to adopt stronger political rights. Countries with lower levels of political rights, i.e., with more restrictions, will have more “space” to disagree on political rights and related issues. Although there are no clear expectations about the relationship between political rights and immigration pledge fulfillment, it is more plausible to expect that the pledge-to-policy effect on immigration could be more strongly pronounced in countries that have weaker political rights protections because the issue will be more salient in these contexts.

Political-rights hypothesis

Legislative policy action on immigration will reflect the emphasis on immigration in governing parties’ election manifestos more strongly in countries with more restrictive political rights of immigrants.

Related to the arguments above about the importance of context, constraints also matter. Power sharing and institutional checks affect governing policy (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002; Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012) and, more specifically, pledge fulfillment (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017; see also Knill et al. Reference Knill, Debus and Heichel2010). With respect to institutional constraints, in political systems that exhibit more institutional controls with a greater number of veto players, governing parties might find it more difficult to implement their platforms (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002).Footnote 3 The literature on the political economy of the welfare state looks at other important factors (or constraints) to explain governing policies. Stephens (Reference Stephens1979) highlights factors like the power of labor and government partisanship, and “varieties of capitalism” studies feature relations between businesses, financial institutions, workers and governments (Hall and Soskice Reference Hall and Soskice2001). Finally, there is research about how the macro-economy can pressure governments to compensate those adversely affected by globalisation, deindustrialisation and other changes associated with advanced capitalism (Iversen and Cusack Reference Iversen and Cusack2000). More recently, Ezrow et al. (Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020) show that governments’ policy responsiveness to public opinion is conditional on the economy. Poor economic conditions can have an adverse effect on governments’ capacities to respond to citizen preferences.

Similar to the political rights discussion, there are competing arguments as to how to apply the above arguments to immigration policy. On one hand, poor economies may inhibit governments from following through on “bread and butter” economic issues such as welfare state generosity (Ezrow et al. Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020). If this is the case, in the absence of being able to implement policies in costly policy areas, governments potentially search for less expensive policies to claim credit for during hard economic times. Restricting immigration by changing foreign visa rules, although expensive in the long term, is arguably cheaper than traditional economic spending policies in the short-term, e.g., when compared to national spending on health care, policing, education and welfare. Thus, when the economy is not performing well, governments could potentially substitute following through on policy pledges in more traditionally expensive economic areas, with following through on policy pledges in the area of immigration.

On the other hand, the claims about traditional spending policies may simply spillover to immigration and recessions will inhibit governing administrations with fulfilling their pledges with respect to immigration policy. Indeed, immigration policies, especially more restrictive ones, can be costly. Restricting migration can reduce a country’s overall economic growth (Dustmann and Frattini Reference Dustmann and Frattini2014; Bove and Elia Reference Bove and Elia2017), while implementing more severe border controls, hiring more personnel to guard a country’s territory, as well as restrictive customs checks impose costs on a state that it may find difficult to cope with when the economy performs poorly. And even less restrictive policies can have negative implications for the economy as several important distributional effects may lower wages in specific segments of a host country’s labor force (Borjas Reference Borjas2014). Thus, the arguments that have been made about poor economies restricting the range of policies of governments are likely to spillover and/or apply across a range of issues, including immigration, suggest that immigration pledges would similarly go unfulfilled in poorly performing economies. This discussion forms the basis for the second hypothesis:

Economic-conditions hypothesis

Governing party platforms on immigration are more (less) readily implemented when the economy performs well (poorly).

Research design

We make use of a unique and recent data set that has been released by Lehmann and Zobel (Reference Lehmann and Zobel2018) who compiled information on party manifesto saliency estimates on immigration in 14 countries and 43 elections between 1998 and 2013.Footnote 4 The data we employ have two key advantages. First, Lehmann and Zobel (Reference Lehmann and Zobel2018) derive the data from manifestos to provide parties’ “unified and unfiltered” immigration positions for countries and time points not covered in expert surveys and media studies. Second, the authors also rely on the new method of crowd coding, which, as discussed thoroughly in their article, allows for a fast manual coding of political texts. The data from Lehmann and Zobel (Reference Lehmann and Zobel2018) ultimately govern the country and time coverage of our analysis.

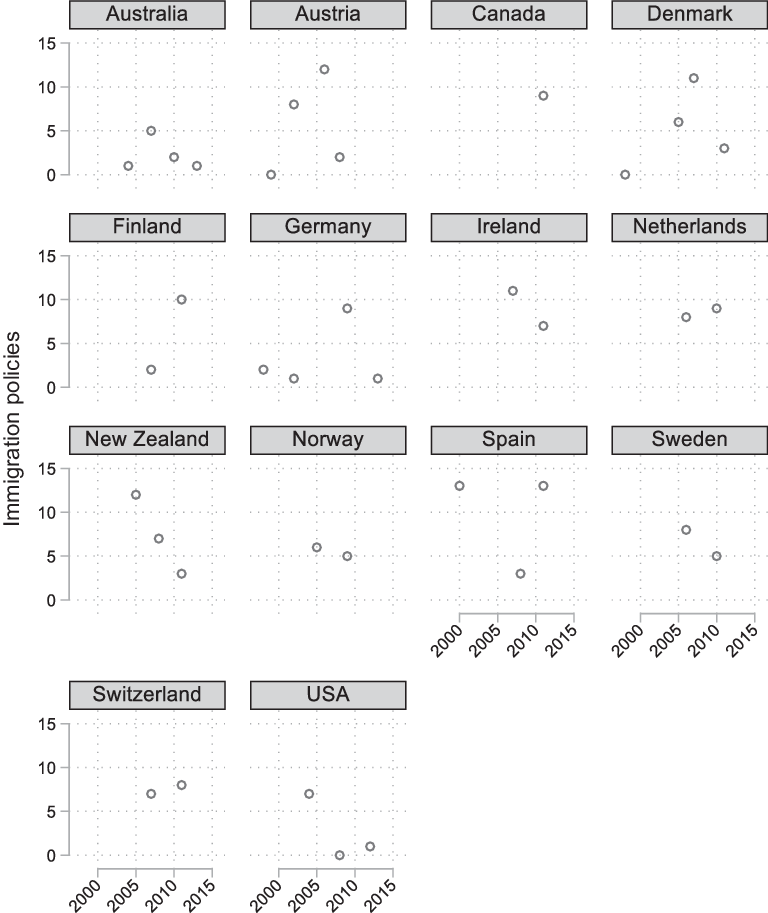

We employ the country/cabinet-year as our unit of analysis and the dependent variable is based on the Determinants of International Migration (DEMIG) Policy Database (Haas et al. Reference Haas, Natter and Vezzoli2014).Footnote 5 These data track policy changes in migration laws in the post-World War II period, with a larger spatial and temporal scope than most other data sets on migration policies.Footnote 6 Each policy measure is coded via four variables – two items on the issue (policy area and tool) and two coding the group targeted (migrant category and geographic origin).Footnote 7 We focus on the number of immigration policy measures implemented in a given country-year (cabinet-year) as our outcome. Figure 1 plots this information for the 14 states included in the analysis. There is a significant amount of variation in the legislative action on immigration policy every year – both across countries as well as within each state over time. We use negative binomial regression models that incorporate a lagged dependent variable as well as fixed effects for countries and years. Intra-group, i.e., country-specific path dependencies and correlations are further captured by clustering the standard errors at this level. The appendix presents analyses based on alternative measures and operationalisations for the dependent variable.

Figure 1. Immigration Policy Legislative ActionDots depict the number of immigration policies per year (horizontal axes) and country. The plot is based on the Determinants of International Migration (DEMIG) Policy Database (Haas et al. Reference Haas, Natter and Vezzoli2014), which is the dependent variable.

Our main explanatory variable captures governing parties’ immigration saliency position. As a first step, using Döring and Manow (Reference Döring and Manow2012), we identified for each country cabinet year in our sample the parties participating in government. In turn, employing the data from Lehmann and Zobel (Reference Lehmann and Zobel2018), we determined each party’s saliency position on immigration. According to their codebook, salience is calculated as the proportion of immigration and integration related quasi-sentences to the total number of quasi-sentences in party manifestos. This item thus varies between 0 and 100% for each governing party and we calculate the average across government parties to arrive at a final, averaged score of immigration salience per cabinet-year (our unit of analysis). Inter-election years are interpolated with the immigration-salience value from the last election. The core explanatory item, Immigration Salience, varies between 0.000 and 16.045% with this approach.

In light of the Political-Rights Hypothesis, we draw on the Immigration Policies in Comparison (IMPIC) project (Helbling et al. Reference Helbling, Bjerre, Römer and Zobel2017) that offers a detailed conceptualisation of the level of immigration policy restrictions in OECD countries. The data set makes a broad distinction between regulations and control mechanisms, internally and externally, while regulations refer to eligibility, conditions, status and rights. In each area, the IMPIC project measures on a quasi-continuous scale between 0 and 1 how restrictive a policy is and there is an aggregated variable, i.e., an average across all items in the data set to capture the total level of restrictiveness of immigration policies in a country. We rely on this variable, which receives higher values for more restrictive migration regimes in place, and interact it with Immigration Salience. Given the Economic-Conditions Hypothesis, we also multiply Immigration Salience with a variable capturing a country’s economic growth to model the postulated interaction effect. We use data from Armingeon et al. (Reference Armingeon, Wenger, Wiedemeier, Isler, Knöpfel, Weisstanner and Engler2019) who compiled information on the yearly change (in percent) in a country’s nominal GDP, i.e., at current market prices.

We consider a series of controls and follow earlier studies that have a similar focus as our work (see, e.g., Joppke Reference Joppke2003; Cornelius and Rosenblum Reference Cornelius and Rosenblum2005; Givens and Luedtke Reference Givens and Luedtke2005; Hansen and Köhler Reference Hansen and Köhler2005; Howard Reference Howard2010; Abou-Chadi Reference Abou-Chadi2016). We identified numerous variables that are arguably exogenous to the dependent variable in order to control for alternative mechanisms that influence the implementation of migration policies. First, based on data from the World Bank Development Indicators, we control for the total population size (or stock) of international migrants and refugees in a country. The World Bank defines the international migrant and refugee stock as “the number of people born in a country other than that in which they live. It also includes refugees.” The data underlying this item were originally obtained from national population censuses as well as states’ statistics on foreign-born (people who have residence in one country, but were born in another country) or foreign populations (people who are citizens of a country other than the country in which they reside). Hence, this item captures the entire population of foreign-born individuals in a state, and we log-transform it due to its rather skewed distribution.

Second, we include three other variables that are taken from the World Bank Development Indicators. On one hand, not only may the economy matter for a conditional effect, but countries’ migration policies are often strongly linked to the economic development directly (e.g., Freeman Reference Freeman1995, 886). We employ the log-transformed GDP per capita (in current US Dollars) to this end, which is defined as the gross domestic product divided by midyear population. GDP is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products. We also control for unemployment in the form of its percent of the total labor force. On the other hand, population size is likely to be linked to the degree of preference heterogeneity in a society, which in turn could affect the public’s demand for migration policies (see Böhmelt Reference Böhmelt2019). We rely on a country’s midyear total population (also log-transformed), which counts all residents regardless of legal status or citizenship (except for refugees not permanently settled).

Finally, we incorporate a variable to address the number of veto players that potentially constrain policy. We use Henisz’s (Reference Henisz2002) item on political constraints, which, according to the author’s codebook, “estimates the feasibility of policy change (the extent to which a change in the preferences of any one actor may lead to a change in government policy) […]. [E]xtracting data from political science databases, it identifies the number of independent branches of government (executive, lower and upper legislative chambers) with veto power over policy change. The preferences of each of these branches and the status quo policy are then assumed to be independently and identically drawn from a uniform, unidimensional policy space. This assumption allows for the derivation of a quantitative measure of institutional hazards using a simple spatial model of political interaction.” Table 1 summarises the descriptive statistics of the variables we have discussed in the research design.

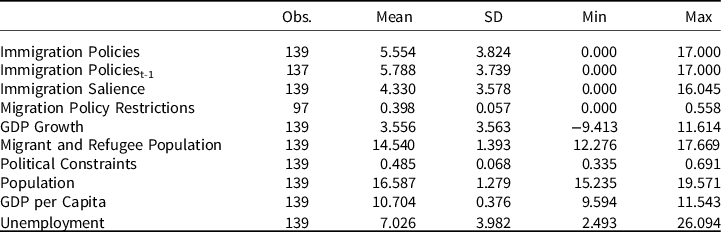

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Interaction variables are omitted from the table.

Empirical results

We begin the empirical analysis with a set of unconditional models that focus on testing the first hypothesis. Table 2 presents three models: the first one only includes the Immigration Salience variable next to the lagged dependent variable and fixed effects, and we omit all substantive controls. We introduce the latter to the estimation in Model 2, but discard our core predictor. Model 3 incorporates all explanatory variables we have discussed above except for the interactions including Migration Policy Restrictions or economic growth. The coefficients in the models can be interpreted as expected log-counts, i.e., for a one unit change in the predictor variable, the difference in the logs of expected counts is predicted to change by the respective regression coefficient, given the other predictor variables in the model are held constant.

Table 2. Analyzing Immigration Policies: The Pledge-Fulfillment Hypothesis

Table entries are coefficients, and robust standard errors clustered on country are in parentheses. The dependent variable is Immigration Policies, which is based on the amount of attention devoted to immigration policies in the governing parties’ election manifestos. Constants are included in all models, but omitted from presentation.

*p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

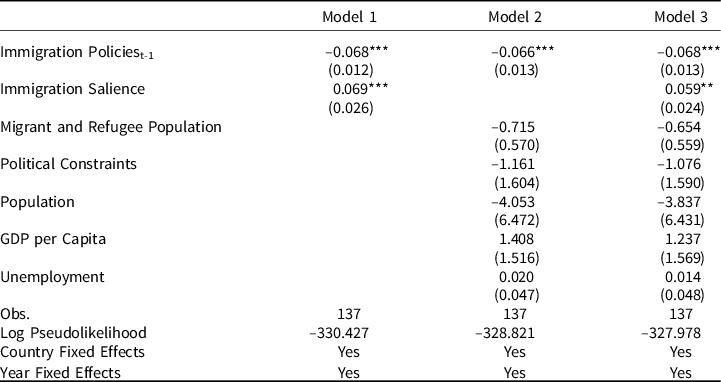

Most importantly for our argument, Immigration Salience is positively signed and significant at conventional levels. That is, the higher the salience of immigration as a policy issue for the parties that have formed a cabinet, the more immigration policies are likely to be implemented in turn. Including or excluding the controls does not substantively affect the size of the coefficient of Immigration Salience. Interpreted, the coefficient estimate of 0.069 translates into an expected increase of 1.071 in the number of immigration policies being implemented for a 1 percentage-point rise in Immigration Salience. Thus, our finding is not only statistically significant but also substantively important as the size of the estimated effect is large. Figure 2 sheds additional light on the substantive effects in which we plot the expected number of policies for each value of Immigration Salience. As demonstrated, the number of policies swiftly increases from about 3.7 policies for a value of 0 in Immigration Salience to about 10 policies when our main predictor is at its maximum. In sum, linking these results back to our theory, we do indeed obtain support for the claim that governing parties that devoted more space to immigration issues in their manifestos subsequently pass more immigration-related legislation – with immigration being one of the most salient policy areas of our time. The results for the controls are rather inconclusive as the variables fail to reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

Figure 2. Immigration Salience and the Predicted Number of Immigration PoliciesDashed lines depict 90 percent confidence intervals. Rug plot along the horizontal axis indicates the distribution of Immigration Salience. The calculations are based on Model 3 (while holding all other variables constant at their means).

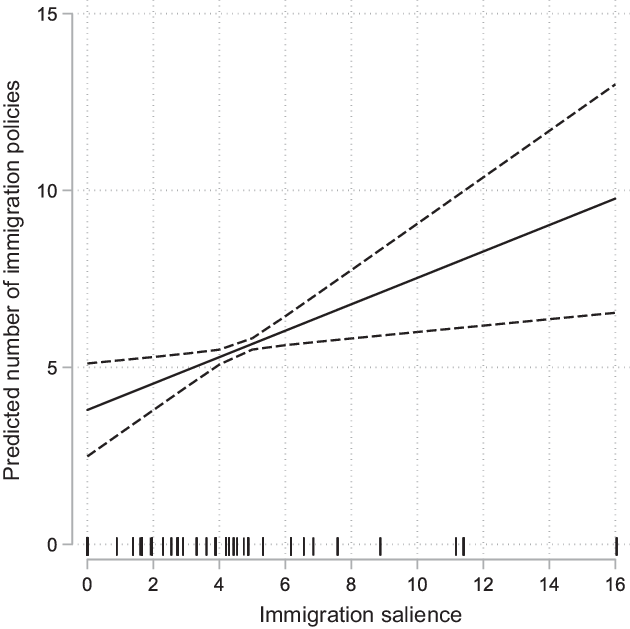

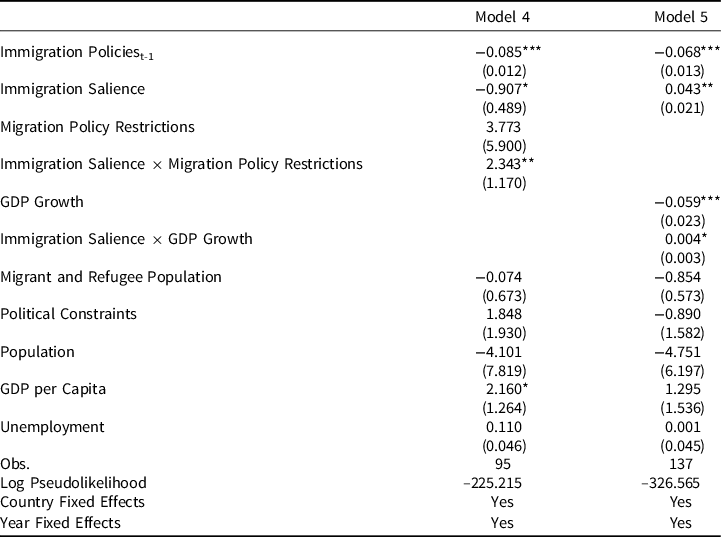

We also propose that certain conditions may influence the relationship of our core variables of interest. First, there is the Political-Rights Hypothesis, which states that legislative policy action on immigration will reflect the emphasis on immigration in governing parties’ election manifestos more strongly in countries with more restrictive political rights of immigrants. Also, the Economic-Conditions Hypothesis states that governments follow their campaign pledges when economic performance improves. To test the expectations linked to these hypotheses, we have modified Model 3 by including Migration Policy Restrictions or GDP Growth and their respective interactions with Immigration Salience. Table 3 presents our results.

Table 3. Analyzing Immigration Policies: Conditional Effects

Table entries are coefficients, and robust standard errors clustered on country are in parentheses. The dependent variable is Immigration Policies, which is based on the amount of attention devoted to immigration policies in the governing parties’ election manifestos. Constant is included, but omitted from presentation.

*p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

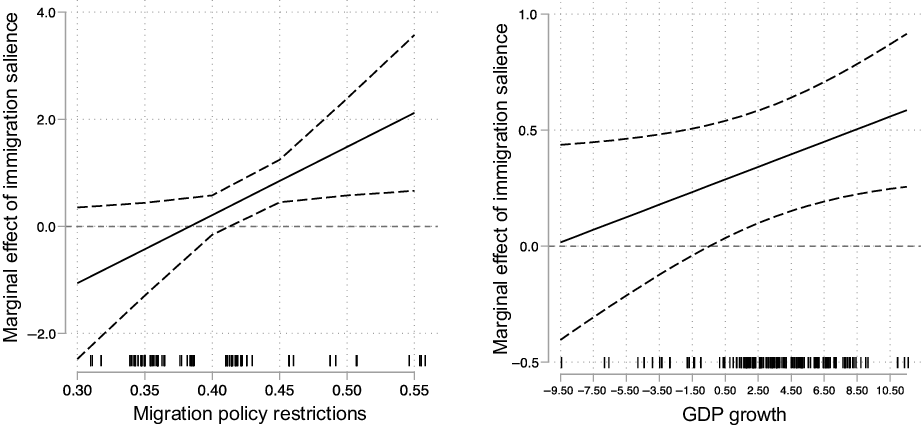

The interaction terms are positively signed and significant at least at the 10% level in both Model 4 and Model 5. Brambor et al. (Reference Brambor, Clark and Golder2006) remind us, however, that it is difficult to interpret signs, size and statistical significance of many interaction models directly and, thus, we plot the marginal effects of Immigration Salience for different values of Migration Policy Restrictions and GDP Growth in Figure 3. First, this graph depicts a positive and significant marginal effect for Immigration Salience only for positive values of GDP Growth, i.e., when the economic power of a country increases. In case of economic stagnation or decline, the results are inconclusive, suggesting that governments – even if their campaign pledges may have emphasised immigration – are less likely to follow-up on their promises and to implement more immigration-related policies. Figure 3 demonstrates, in more substantive terms, that a 4-percentage point rise in Immigration Salience is linked to about one more immigration policy when the economy grows by 0.5%.

Figure 3. Marginal Effects of Immigration Salience – Conditional EffectsDashed lines depict 90 percent confidence intervals. Rug plots on the horizontal axes indicate the distribution of Migration Policy Restrictions. The calculations are based on Model 4 (while holding all other variables constant at their means). The marginal effect of zero is marked by the dotted horizontal line.

Second, governing parties are more likely to pursue legislative action on immigration policies when they have emphasised this issue in their election campaigns and if policy restrictions are comparatively restrictive already. The left panel in Figure 3 shows that the positive and significant effect of Immigration Salience we report in Table 2 above only holds when Migration Policy Restrictions is above a value of about 0.4. In other words, more restrictive environments seem to reinforce the effect of Immigration Salience we identified before. As in the unconditional models, the control variables are statistically insignificant.

To put these conditional results into perspective, it is important to consider the recent studies that suggest that the policies viewed as salient by the electorate are less likely to make it into legislative action (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017; Mellon et al. Reference Mellon, Prosser, Urban and Feldman2019). Our findings do not necessarily question this important insight; rather, they show that pledge fulfillment can work for salient policy issues under some conditions. Specifically, more restrictive migration regimes seem to be linked to a rather “salient policy environment” already, and when governments can “afford” policy changes (see Ezrow et al. Reference Ezrow, Hellwig and Fenzl2020), the translation of salient electorate preferences into policy action becomes more likely. To assess the robustness of our results, we changed a series of model specifications and re-estimated our core model in the appendix. These robustness checks focus on the actual level of restrictiveness in migration policy regimes, the disaggregation of our salience variable, a different outcome variable capturing the share of restrictive immigration policies implemented in a given country-year, weighing our main explanatory variable by cabinet parties’ seat sharesFootnote 8 and, finally, estimating the parameters of a simultaneous equations model. All these additional analyses are reported in the appendix and provide further support of our arguments.

Conclusion

Do parties pursue legislative action that meets their electoral campaign emphasis once in office? The motivation behind our article stems from the puzzling observation that administrations have, on average, a rather solid record in fulfilling their pledges. However, this does not apply to the most crucial policy issues (e.g., Mellon et al. Reference Mellon, Prosser, Urban and Feldman2019). Focusing on migration as one of the most salient policy issues of our time, we developed hypotheses that concentrate on how policies are made in this area. First, the Pledge-Fulfillment Hypothesis states that governments are likely to have strong and genuine incentives to implement what they have promised in their election campaigns – and we argue that this should apply for some of the most crucial policy domains such as migration. Ultimately, governing parties that devoted more space to immigration issues in their manifestos are in turn more likely to pass more immigration-related legislation. In the words of Thomson et al. (Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017, 528), this “complements the saliency approach to the mandate model, in which scholars focus on the relative emphases parties place on different policy themes.” Second, we proposed that context matters for pledge fulfillment, by evaluating the conditional effects of political rights and economic performance on pledge fulfillment.

Our findings make crucial contributions to the literatures on democratic representation, economic performance, and (immigration) policy making. Arguably most importantly, we shed light on the ambiguity surrounding the saliency approach in the pledge-fulfillment nexus when it comes to salient policy issues. While previous work does not find support for the notion that cabinets meet their promises with legislative action when it comes to salient electorate preferences, we highlight that it may well be given, but only under some specific circumstances: a growing economy. As a result, we offer a key finding to the study of saliency and pledge fulfillment, and also inform policymakers when legislative action is possible, can be afforded, and perhaps even should be pushed through to ensure political survival. For instance, with an estimated economic growth of 1.4%in the UK 2019 but a projected decline for 2020,Footnote 9 the administration is predicted to successfully implement their campaign pledges on immigration in the short-term – but that their longer-term post-Brexit commitments on immigration will be more difficult to fulfill.

We believe that our empirical findings represent an important step forward for understanding saliency, pledge fulfillment and immigration policy. We conclude that parties with rather salient immigration issues in their manifestos subsequently pass more immigration-related legislation once in power and that the translation of pledges into legislative action is facilitated by a strong economy and more restrictive immigration policy regimes.

However, these conclusions come with three caveats. First, our main analysis focuses on the “volume” of immigration-related content in governing parties’ manifestos and the “volume” of immigration legislation. The appendix provides some evidence to suggest that, for immigration policy, salience in election manifestos and the direction of subsequent policy outputs are related. Data limitations, however, prevent us from conducting a cross-national longitudinal analysis that addresses the specific content of both the governing parties’ immigration promises and the legislation that they subsequently pass. A second, related, limitation of our work is that we do not characterise the correspondence between more specific policy objectives within immigration outlined in party platforms and the laws that are then enacted and issued. Hence, because we do not analyse specific objectives in manifestos and specific laws that are subsequently enacted, the analyses arguably lack precision. Third, endogeneity concerns remain: do parties pass more immigration laws in the aftermath of discussing immigration because they want to demonstrate their ability to follow through on promises as the pledge fulfillment literature suggests? Or are parties devoting more attention to the issue of immigration because they anticipate legislative action on the topic? While we partially address these concerns in the appendix in which the parameters of a simultaneous equations model are estimated, more precise time-related measures could be employed. The above limitations notwithstanding, our analysis sheds light on the saliency approach in the literature as we are confident that the salience of immigration in party platforms corresponds to the overall production of policies (under some circumstances).

There are several important avenues for future research. Unsurprisingly, several of these are related to the limitations discussed in the paragraph above. Scholars may want to compile more detailed and disaggregated data on parties’ campaign promises and subsequent policy action. Thompson et al. (Reference Thomson, Royed, Naurin, Artés, Costello, Ennser-Jedenastik, Ferguson, Kostadinova, Moury, Pétry and Praprotnik2017), among others, suggest that text analysis of the content of party manifestos and laws is likely to be a fruitful approach here, allowing us to distill particular policy promises to cross reference them against specific bills. Furthermore, with respect to endogeneity, a more detailed empirical analysis, potentially one that parses out time more precisely, is needed to deal with the underlying causal mechanisms driving pledge fulfillment.

We also hope to have initiated a focus on the conditions that allow for the translation of parties’ campaign pledges into governmental policies. We have focused on immigration policies, in the context of political rights and economic growth (and controlled for institutional checks such as veto players). Yet, there are several future studies of pledge fulfillment that follow from the analyses presented here. For example, parties with democratic organizations may be more likely to follow through on campaign promises (Lehrer Reference Lehrer2012; Schumacher et al. Reference Schumacher, De Vries and Vis2013), because the activists who select leadership are committed to seeing their parties’ election manifesto policies implemented. Furthermore, it is largely assumed that there are electoral consequences for failing to implement campaign pledge commitments, and these effects may indeed be stronger with respect to immigration.

To summarise, our results support the finding that pledge fulfillment occurs as it relates to the salience of immigration. Additionally, immigration pledge fulfillment occurs more readily in countries that restrict political rights and that exhibit strong economic performance. This study thus contributes to our understanding of how the salience of immigration in parties’ election pledges translates into policies on immigration.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X20000331

Data availability

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DPWXQG