“Seeing is believing,” Sarah Hallowell decided, so one fall morning in 1879 the reporter for Philadelphia's Public Ledger stepped off a train in Quincy, Massachusetts to observe the alleged revolution sweeping its elementary schools. The unassuming town's so-called “Quincy Method”—a pedagogic reform focused on improving classroom teaching—was attracting great attention. Hallowell wanted to see the changes for herself. “Which [school] do you call the best?” she asked a teacher on the platform. This was an irrelevant question, as even the reform's staunchest critics would recognize its feat of instituting an ambitious, consistent instructional program across a network of otherwise ordinary schools. “There is no best,” the teacher told Hallowell, “they are all alike.”Footnote 1

Hallowell spent that morning at the Coddington School which tallied the most visitors each year because of its proximity to the train station. As she crossed the school yard where children played, Hallowell saw no textbooks tucked under their arms—a noteworthy detail given the rumors that Colonel Francis Wayland Parker, Quincy's pioneering superintendent, demanded all of the textbooks burned.Footnote 2 “You might have thought it was a holiday,” she reflected.Footnote 3

“I do not crush out errors in spelling, nor make a culprit of the child who makes mistakes,” a teacher named Lizzie Morse told Hallowell as she readied her blackboard.Footnote 4 Minutes later, Morse's class sprang into action with “the conversation exercise,” a spirited, unstructured deliberation among students. One boy stood up to begin: “On my way to school I saw two men digging. What do you suppose it was for?” For ten minutes, students issued responses “very much as if on the playground,” each “alert and at their ease, a correction only put in now and then, but entirely in a suggestive way by the teacher.”Footnote 5

In another classroom, students worked with clay on molding boards, “pinch[ing] up . . . mountain range[s] into peaks like so many small cocoa nut cakes.”Footnote 6 And in music lessons, students actually sang songs rather than simply commit notation to memory. “Remembering the unhappy children in some of our Philadelphia schools who are drilled in lines and spaces and rests as though their future salvation . . . depended on these,” reflected Hallowell, “I could not but give thanks for the Quincy method, that gets out the singing and the threads of voices without destroying the cocoons.”Footnote 7

A clear pattern resounded across Coddington's classrooms. Lively, child-centered lessons had supplanted the recitation drills, silent work, and overdependence on textbooks so common in public schools.Footnote 8 Quincy, Hallowell concluded, would “have to be rechristened” as “the Mecca of school teachers.”Footnote 9

But one year later, Quincy's system-wide cohesion was slipping from the school committee's fingers. Though an enhanced teacher corps may have improved Quincy's schools and transformed the town into a vaunted education mecca, an unintended consequence accompanied this change: failing to retain its esteemed pedagogues, Quincy began hemorrhaging teachers to higher-paying school systems and higher-status positions in the field.Footnote 10 Lizzie Morse counted 638 classroom visitors the year Hallowell watched her teach.Footnote 11 She would soon depart to a town that offered her a one hundred dollar salary increase.Footnote 12

“Perhaps only those familiar with schools can quite realize the amount and kind of injury which they suffer from changing teachers,” Quincy's school committee lamented in response to the turnover. “The continuity is broken, and no matter how competent the successor, the scattered threads can only be collected and re-arranged after vexatious waste of time and fruitless toil.”Footnote 13

Two histories on the Quincy Method, both published in 1967, discuss, if briefly, this instability its schools experienced. In Colonel Francis W. Parker: The Children's Crusader, a biography of Francis Parker, Jack Campbell suggests that the school committee's salary cuts precipitated teachers’ departures.Footnote 14 Similarly, Michael Katz discusses the committee's strategy to advance reform through “excellence” and “economy”—securing better instruction at low costs—and these dual aims’ eventual fissure.Footnote 15 On the whole, however, the historiography of progressive education overlooks these unintended consequences, presenting Quincy as a successful early school reform.Footnote 16

The Quincy reform story, typically told, concerns noble schoolmen who, discouraged with the poor state of their schools, embarked on an exhaustive search for an expert on teaching to turn them around. It is a story about a uniquely qualified superintendent, Francis Parker, who transformed a lackluster school system into a nerve center of child-centered instruction and became the darling of the “new education” movement. More recently, scholars have drawn on Quincy's example to distill relevant lessons for contemporary school leaders and instruction. Comparing the nascent scientific management theories Quincy resisted with present-day standardization efforts in schools, James Nehring highlighted the reform as a “case in point” of a superintendent who successfully held the “manufacturing metaphor at bay.”Footnote 17 Patrick Shannon used reading lessons from Quincy to frame his study of progressive literacy instruction, underscoring Quincy's innovative emphasis on student dialogue.Footnote 18

In this article, I revisit the Quincy Method, picking up on the instability Campbell and Katz raised to advance an additional explanation for why early progressive reforms often failed to take hold. I argue that the nineteenth-century teacher labor market in Massachusetts created conditions that led both teachers and systems to exploit Quincy's schools for their own advancement. Quincy's full-time and apprentice teachers, virtually all of whom were women, used the reform to secure higher-paying, higher-status positions elsewhere, while cities and towns used it to navigate the state's oversupply of teachers and capture experienced, learned applicants for their own schools. These trends made it difficult for Quincy's tidy system to maintain its novel instructional cohesion.Footnote 19 And while the resulting scatter of teachers should have helped Quincy's pedagogies penetrate more school systems, teachers frequently assumed positions in education outside public schools altogether or in systems poorly structured to sustain and scale what they had learned in Quincy. These market-influenced trends limited the Quincy Method's impact. While such trends were not necessarily unique to Quincy, they reveal central challenges nineteenth-century schools faced as they attempted to introduce instructional change across classrooms.

The case of Quincy, thus, instantiates an early reform's interaction with the teacher labor market, an interaction the historiography of progressive education has seldom considered. Its study bridges scholarship on progressive education with that of nineteenth-century teachers and labor markets. In probing teachers’ strategic negotiation of pedagogic innovation, it contributes to literature exploring how women teachers used the profession to advance themselves.Footnote 20 In addition, it offers a largely unexamined window into how municipalities engaged with innovation as they confronted market forces. Together, these contributions extend theories of school reform and invite a more comprehensive treatment of both teachers and school systems in assessing the success of early reforms.

To be sure, the story of teacher mobility recounted here did not hold for all American teachers. While no sources explicitly document their social characteristics, Quincy teachers likely reflected those of Massachusetts in general as overwhelmingly White and native-born. The 1890 federal census reported no African American public school teachers in Quincy's Norfolk County and just three in Boston's Suffolk County which employed 1,486 teachers.Footnote 21 Further, the Massachusetts 1880 census reported that about 95 percent of teachers in the state were native-born.Footnote 22 Historians have additionally demonstrated that Massachusetts teachers typically hailed from middle-class backgrounds.Footnote 23 Just a small fraction of the state's teachers in the mid-nineteenth century originated from families of unskilled laborers.Footnote 24 Although some portion of Quincy's teachers graduated from the town's high school and, therefore, came from local families, based on available data, they most likely did not represent the town's growing immigrant population. This picture of teachers’ social origins, though imperfect, suggests that seeking out and migrating to better employment opportunities—some of which were considerably farther away than neighboring cities or towns—was a luxury Quincy teachers enjoyed in part because of their privileged status as White and native-born.

To tell this story, I draw on a range of primary sources. Annual reports by Quincy's school committee and superintendents along with accounts from Parker, committee member Charles F. Adams, and Isaac Freeman Hall, a Quincy principal, offer the most extensive firsthand histories of the reform.Footnote 25 Since official reports were often political in nature, describing schools as favorably as possible, I often reference reports from the Massachusetts Board of Education to tell a more balanced story. Reports from other Massachusetts school systems further contextualize Quincy's changes and provide insight into the state's labor market. With its pleas to residents and school leaders, the local newspaper, The Quincy Patriot, added additional depth. Finally, education periodicals, usually stewarded by normal schools, produced several commentaries on Quincy, many based on firsthand visits, which I draw on throughout.Footnote 26

Parker, the charismatic leader John Dewey himself named the “father of progressive education,” overwhelms scholarship on the Quincy Method such that when Parker leaves Quincy for Boston in 1880, historians typically follow him.Footnote 27 By bringing together the abovementioned sources and considering the reform's life beyond Parker's tenure, I hope to shed greater light on teachers’ complex relationships with the Quincy Method than historians have done previously. Although a shortage of direct testimonials from teachers makes this difficult, considered together, the sources collected here paint a more multilayered portrait of Quincy's critical reform agents.

I begin this exploration with an overview of the Massachusetts teacher labor market between 1870 and 1890. This overview sets the stage for a study of of the Quincy context and Quincy Method, where I highlight teachers’ meetings as essential to facilitating the reform's system-wide reach. I then examine how the labor market and the Quincy Method interacted and consider the consequences this interaction held for the reform's sustainability. The article concludes with a discussion of the Quincy Method's broader impact and considers the article's contribution to scholarship on school reform.

“Ordinary Teachers” and “Educational Piracy”: The Late Nineteenth-Century Teacher Labor Market in Massachusetts

By 1870, nearly 90 percent of Massachusetts teachers were women.Footnote 28 This feminization of the profession began in the 1840s, when Horace Mann, the state's first education secretary, promoted the hiring of female teachers to expand public schooling. This promotion was two-edged: while Mann cast women as better suited than men to working with children, he also underscored their contentment to “never look forward, as young men almost invariably do” nor to seek “future honors or emoluments.”Footnote 29 There was economic incentive for hiring women as they would earn, on average, 60 percent less than their male counterparts.Footnote 30 Still, women found appeal in a profession that promised financial independence, the potential for social networking and intellectual nourishment,Footnote 31 and even the material prospect of their own physical space.Footnote 32 With few career alternatives open to them, young women attended school at high rates in Massachusetts with plans to eventually enter the profession.Footnote 33 Susan Carter observes that these factors produced an oversupply of teachers in the state. And while the educated workforce that resulted may have ultimately improved instructional quality in Massachusetts compared to other parts of the country, Carter indicates that the oversupply also depressed teachers’ already low wages.Footnote 34

A teacher surplus created challenges for school systems. Committees sifted through large applicant pools ranging widely in skill. This was especially true for wealthy systems. In Boston, for example, the supply of eligible candidates in 1880 was twice the demand.Footnote 35 While the higher salaries of these systems attracted more competent teachers, “good pay,” observed The Normal Teacher, “lures in, likewise, the moth.”Footnote 36 Across the state, there appeared no shortage of what committees called “ordinary teachers”; a shortage of “good teachers,” however, plagued committees.Footnote 37 School officials used different language to describe what made a good teacher. The skill set was often multifaceted, including qualities like experience, natural ability, enthusiasm, and self-control. But overall, they agreed that good teachers possessed robust knowledge of the subjects they taught and the pedagogic expertise to impart that knowledge to students. The latter required a deft understanding of teaching's principles and child development theories. Desirable teachers, therefore, required special training. Accordingly, quality instruction was often equated with “normal teaching”: formal training at a Massachusetts normal school.

The demand for normal teachers, however, far exceeded the supply. Though Massachusetts had more normal schools than most states, just 20 percent of teachers received this training.Footnote 38 Instead, most entered classrooms with minimal training as high schoolers. And though high schools and eventually training schools managed by school systems produced teacher crops well-acquainted with local schools, they did not always deliver competent candidates.Footnote 39 Some systems worried that depending too heavily on local supplies could insulate their classrooms from innovation. New Bedford, for example, complained that such “inbreeding” created “narrowness and lifelessness” in its schools.Footnote 40

One way systems appeared to navigate the oversupply and secure quality teachers was to place a premium on candidates who had accrued noteworthy classroom experience elsewhere.Footnote 41 Gambling on fledgling instructors, many decided, was too costly—as the school committee in Stoneham reasoned, “We cannot afford to employ those teachers who must grope their way to success and skill, if we can secure others whose work has been proved.”Footnote 42 In 1886, the Cambridge school committee boasted that it had “secured the services of several teachers who in other places have attained eminence in their profession.”Footnote 43 Prioritizing experience also let school committees observe candidates firsthand before hiring. Advising systems on teacher selection, the Board of Education called observation the most dependable means of vetting candidates and gauging quality. “Here,” it wrote, “can be observed everything that enters into good school teaching. The style of the teacher, and the relations he holds to his school, will appear at once.”Footnote 44

Given these priorities, larger, wealthier systems increasingly looked to smaller ones to replenish their ranks. Weymouth's committee complained of frequent visits its schools received, hastening the loss of capable teachers. Weymouth’s schools, it reasoned, were a “convenient and inexpensive” means for Boston's “teachers’ agencies” to seize verified talent.Footnote 45 Hyde Park's school committee similarly lamented how wealthier cities and towns made their schools a “foraging ground” to the same end.Footnote 46 A state report published in 1889 described the practice further. Calling it educational piracy, a committee member of a smaller, undisclosed municipality made the following entreaty to the report's author about a nearby school leader:

Now, cannot you influence him to leave us alone, to draw his supply of teachers from some other source? It does seem to me as though it was hardly necessary for him to send to this little village for teachers, when he has at his command time and money unlimited, has an acquaintance far and wide.Footnote 47

Just as school systems sought to gain purchase over the labor market, so too did teachers. Poor wages and working conditions in small towns and country schools precipitated greater turnover in these systems, with teachers departing often to pursue improved financial situations.Footnote 48 Responding to the value cities placed on experience, teachers appeared to use lower-paying school systems as stepping stones to wealthier ones. As a teacher of a small town confessed in the aforementioned report, “I am here for experience, not money.”Footnote 49 Though turnover remained high across the profession, these smaller systems were most impacted. Conversely, the competitive salaries of Boston, Brookline, Cambridge and Somerville helped retain teachers’ services for longer.Footnote 50 These systems also had the means to raise teachers’ earnings to keep them from pursuing outside offers.

It is against this backdrop that pedagogic change took root in Quincy. In a labor market characterized by ordinary teachers, high turnover, low wages, and an emphasis on experience and classroom visits in selection, Quincy introduced system-wide change in its schools. These market forces, however, made sustained change difficult. With Quincy surrounded by wealthier systems, its pedagogic feats ever on display, innovation further imperiled an already vulnerable system.

From “Schoolkeeping” to “Artist Teaching”: The Transformation of Quincy's Public Schools

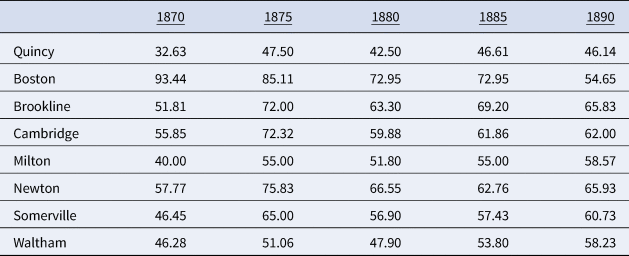

During its early industrial period (1840–1870), Quincy saw significant demographic changes. Opened in 1846, the Old Colony Railroad further established the town as a bedroom community for the wealthy, but it also brought newcomers looking for work in Quincy's granite quarries.Footnote 51 First came New Hampshirites, followed by Irish and Scottish immigrants.Footnote 52 In 1870, the town's population was 7,500; by 1885, it had grown to 12,000.Footnote 53 Though Quincy's school system expanded and introduced larger, graded schools to accommodate these changes, the school committee continually judged it “out of the question . . . to measure purses” with neighbors like Boston or similarly sized Brookline, as its wealth per capita was considerably lower.Footnote 54 Additionally, the town's growing laboring class proved resistant to increased school spending.Footnote 55 To illustrate spending differences, Table 1 compares the wages female teachers earned in Quincy to the wages female teachers earned in nearby cities and towns.Footnote 56

Table 1. Average Monthly Wages of Female Teachers in Quincy, Massachusetts and Surrounding Communities

Sources: Board of Education reports.

Despite these demographic changes, instruction in Quincy's schools was characterized by inertia.Footnote 57 It had escaped criticism from the Quincy school committee as schools conducted their own annual evaluations. When Charles F. Adams joined the committee in 1872, he proposed it evaluate the schools themselves. “The schools went to pieces,” wrote Adams.Footnote 58 Students demonstrated fluency in rules and formulas but could not usefully apply them. They knew grammar but could not pen letters, could decode rehearsed passages flawlessly but stumbled when shown new texts.Footnote 59

Something had to be done, and in a growing town, keeping costs low was imperative. Excellence and economy hence became the committee's dual aims.Footnote 60 But knowing little about teaching beyond their instincts, committee members found themselves ill-equipped to steward the cures they envisioned.Footnote 61 After a discouraging superintendent search, Colonel Francis Parker entered the committee's offices. A New Hampshire native, seasoned teacher from Ohio's schools, and Civil War veteran, Parker had recently returned from Europe studying the teachings of Friedrich Froebel and Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi.Footnote 62 Parker shared the committee's disdain for rote instruction, enlightened them with object lessons he learned overseas, maintained that children learned best through doing, and argued that play and discovery ought to precede rules and formulas. Mesmerized, the committee hired him.Footnote 63

Reforming teaching in Quincy, Parker distinguished between “schoolkeepers”—he called them a “dreadful incubus” to educational progress—and “artist teachers.”Footnote 64 Whereas schoolkeepers merely managed classrooms, the lowest standard for work in schools, artist teachers engaged in the grander work of “mind and soul-building.”Footnote 65 They possessed “a deep and abiding love for children, and a thorough training . . . in the laws and methods under which the faculties develop.” And the work of the artist teacher was never done, their methods “ever changing, ever improving.”Footnote 66 Parker similarly distinguished between training and teaching. Training meant imparting “correct and skillful habits of mechanical execution”; teaching meant leading students to think for themselves and developing their “senses, reason, imagination, [and] will.”Footnote 67 While both were important, Parker argued that “the great mass of teachers train but do not teach.”Footnote 68

Recent state and local reforms in Massachusetts also sought to improve teacher quality, though less directly. The elimination of the district system which fragmented municipalities and produced unequal, inconsistent education across them, helped standardize selection practices.Footnote 69 Committees also now administered written examinations to prospective teachers to gauge their qualifications.Footnote 70 A wider, system-level overhaul that focused on uniting teachers under a common instructional framework and sustained professional development, however, was comparatively unique.Footnote 71

Beginning in 1875, Parker immersed Quincy's teachers in “long, careful, patient, persevering study.”Footnote 72 From the start, he downplayed the changes.Footnote 73 He repeatedly averred that there was “no peculiar Quincy System,” that he was “simply trying to apply well-established principles of teaching.”Footnote 74 He went as far to assure one bitter critic they would “learn nothing in Quincy.”Footnote 75 Adams, conversely, played up the Quincy Method and packaged it as something entirely new. His widely circulated pamphlet The New Departure in the Common Schools of Quincy thrust the reform into the national spotlight.Footnote 76 Such promotion garnered attention for Quincy's schools, affording its teachers distinction, but it also earned Adams foes.Footnote 77 Boston superintendent John Philbrick called Adams's treatise “a declaration of war” that mocked superintendents’ work while extolling Quincy as the “only luminous spot on the educational chart of the State.”Footnote 78

Though Philbrick's arguments against Quincy's reform were largely personal, his rejection of Quincy's pedagogies as brand-new held merit.Footnote 79 Indeed, several other luminous spots existed.Footnote 80 For nearly two decades, the kindergarten movement had employed similar child-centered practices.Footnote 81 Before Parker, pioneers of early childhood education like Elizabeth Peabody and Susan Blow traveled to Europe to absorb Froebel's and Pestalozzi's teachings. Horace Mann had done so as early as 1844.Footnote 82 Meanwhile, normal schools had long trained students in related pedagogies.Footnote 83 Since the 1860s, students at the Oswego State Normal School learned the “Oswego Method” under Edward Sheldon's leadership—an object teaching method to which, one Oswego normal school graduate insisted, Quincy's practices were “directly traceable.”Footnote 84 Some school systems even claimed they had already been practicing an equivalent of the Quincy Method, albeit “on a limited scale and in a [sic] unostentatious manner.”Footnote 85

Given this context, the Quincy Method must be understood as one instance of progressive education in a period of wider pedagogical ferment. What set it apart was that it flourished within the formal confines of an ordinary public school system rather than in teachers’ institutions, private schools, or spaces beyond the mainstream. Even the reform's fiercest critics admired this triumph. One, who dismissed Hallowell's reporting as naïve, described the reform as “the first distinct recognition of the full force and value of these principles by the entire school authority of an important municipality.”Footnote 86

Quincy achieved this cohesion across its schools by introducing training structures in which teachers could professionally thrive. Though Parker cited a lack of trained teachers as the foremost obstacle in improving Quincy's schools, he argued that the schools’ poor state was “not the fault of the teachers, but of the methods and the system,—or, rather, the lack of a system.”Footnote 87 By “system,” Parker was referring to a “science of teaching.” Like other prominent educators at the time, Parker used the term to describe instruction that ventured beyond discrete “methods” to leverage scientific principles, particularly “mental laws” derived from psychology and philosophy.Footnote 88 This science was unknown to most teachers, and in Parker's estimation, failure to inculcate it produced teachers who “simply follow[ed] tradition, without questioning whether it be right or wrong.”Footnote 89 Moreover, cloistered in isolated classrooms, deprived of opportunities to work together toward common purpose, Quincy's teachers lacked understanding of what good teaching looked like, which only fortified rote teaching.Footnote 90 To combat these familiar aspects of teachers’ work, Parker made weekly teachers’ meetings central to the reform.

Every Monday afternoon, Quincy teachers congregated for lectures, demonstration lessons, and discussions of pedagogy. These meetings held a Socratic orientation, as Parker engaged teachers in fundamental questions: “Education, what is it? What is education for? Why is it necessary?”Footnote 91 Isaac Freeman Hall, a Quincy principal, described the meetings as also deeply practical, equipping teachers with model lessons they could, with practice, adapt to their own classrooms. Still, the aim was “unity instead of uniformity.” Though a unified culture would be crucial for enacting extensive changes, Parker did not constrain teachers’ autonomy.

“How unhampered we really were!” reflected teacher Lizzie Morse. “If we defied [Colonel Parker] openly and boldly and used our own methods instead of his,” she explained, “if we could show him good results, it was all he asked; and we were patted on the back and told that he honored us for our independence and originality and to go on working out our own salvation.”Footnote 92 Julia Underwood, another teacher at the Coddington School, transformed her craft under this in-service training model: “I had ‘kept school’ many years previously to 1875,” she reflected, “but thanks to Colonel Parker's wonderful inspiration, since that time my work has been teaching.”Footnote 93 After Parker left Quincy for Boston in 1880, seasoned teachers like Morse and Underwood gradually played more authoritative roles in teachers’ meetings. Discussing the meetings, Superintendent George Aldrich praised teachers’ helpfulness and desire to improve: “The best teachers have contributed to these meetings by papers, talks and teaching exercises. In this way teachers have become acquainted with each other and have been strengthened by the sympathy always existing between those of the same occupation.”Footnote 94

Here, the teacher labored “not as an isolated and solitary individual, toiling in an unknown and narrow sphere; but as a member of a great company working for a common end.”Footnote 95 And yet, despite Quincy teachers’ growing expertise, their salaries remained low compared to those of nearby systems. The committee even trimmed salaries as the reform progressed and grew in popularity. As early as 1877, a subcommittee formed at residents’ behest to devise salary “readjustments” that would apply to incoming teachers. The committee defended these spending cuts as alleviating the “public burden” and “get[ting] good enough schools for less money.”Footnote 96 But by creating a system for teachers to flourish while flattening wages, Quincy cultivated a class of teachers it could soon no longer afford. Before long, Adams's term “the new departure” would assume an entirely different meaning.

“First-Class Intelligence Offices”: Reform Meets the Teacher Labor Market

When the noon bell rang at Quincy's Coddington School, reporter Sarah Hallowell marveled at how “fresh” everyone seemed, herself included. After all, handing considerable control of the learning process over to students demanded more expertise and preparation from instructors. “Does it exhaust you to be giving out so much to your classes instead of hearing recitations?” she asked teachers. “On the contrary,” they replied. “It is not half so wearing as keeping up the attention to the printed book and going over the recitations by rote. The children are fresh all the time, and that keeps us so.”Footnote 97

Hallowell's columns roused readers in Pennsylvania. The Pennsylvania School Journal urged they “be read by every school director and teacher in Philadelphia and elsewhere.”Footnote 98 While the journal's editor indicated that similar practices existed in Pennsylvania, these cases, he noted, were typically the result of individual teachers here or there, not an entire school system. Other educators concurred.Footnote 99 Soon, more curious parties began making pilgrimages to Quincy. Visitors were “males and females, representing the greatest variety of intellect, culture, and social position as well as places of residence,” wrote The Boston Herald. “The time of visitation was not restricted to certain seasons of the year, or to any particular portions of the school terms.”Footnote 100 These visits produced columns in newspapers and exposés in periodicals, further broadcasting Quincy teachers’ work, and their names were “constantly on the lips of the public.”Footnote 101 For those who “could not go to Quincy to see and hear for themselves,” there was Lelia Patridge's “Quincy Methods” Illustrated, a 600-page volume of observations documenting the town's classrooms.Footnote 102 Figure 1 is a School Journal advertisement for Patridge's book.

Figure 1. Advertisement for Lelia Patridge's “Quincy Methods” Illustrated, The School Journal 29, no. 19 (May 1885), 301.

In 1880, when Parker left for Boston, visitation numbers apparently broke 10,000.Footnote 103 That year, The New York Tribune hailed Quincy as a “starting-point in the reorganization of the deplorable American system.”Footnote 104 The school committee reported that 1881 saw as many as 13,276 visitors.Footnote 105 In 1882, Julia Underwood tallied seventy-eight to her classroom in the first two weeks of the school year alone.Footnote 106 Visitors had become such a fixture of classrooms that the local newspaper, The Quincy Patriot, printed a warning:

Beware, Teachers! One of the leading features of excellence at Quincy is said to be the improved methods in teaching language and grammar. Great, therefore, was the surprise of one of these out-of-town visitors the other day on hearing a Quincy teacher say to one of her pupils: “Yes, you was,” and “Don't copy from the girl side of you.”Footnote 107

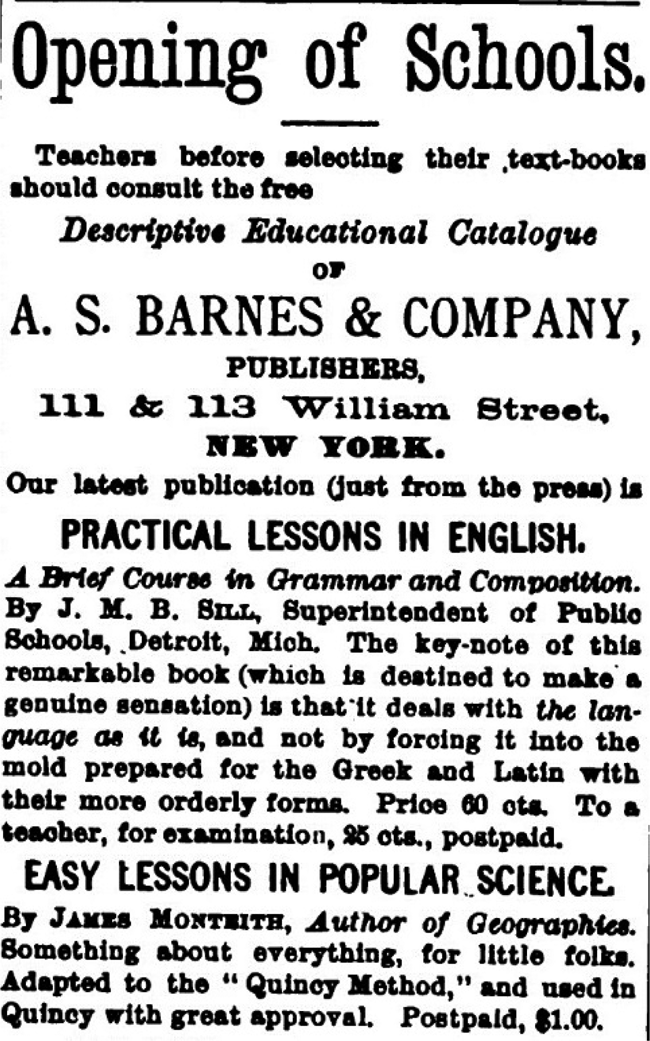

“Quincy” quickly became a buzzword, what one magazine called “a synonyme for something universally acknowledged as excellent.”Footnote 108 Textbook publishers flaunted their products’ use and endorsement by Quincy insiders.Footnote 109 Figure 2 provides an example of this marketing practice. A stamp of approval, the descriptor “of Quincy fame” often trailed the names of teachers and administrators who had worked there. Meanwhile, an evaluation from the Board of Education that compared student outcomes on an examination administered across Norfolk County revealed that Quincy's were “superior to those obtained in any of the other towns,” further bolstering the town's reputation.Footnote 110

Figure 2. Textbook advertisements used the Quincy name to help sell books. The Christian Union 22, no. 11 (Sept. 1880), 211.

Outsiders’ interest in Quincy's transformation suggests that public schools were becoming relatively fertile ground for progressive pedagogies. With classroom observations championed as a new way for teachers to learn, school systems sent young teachers to Quincy to stockpile innovative practices.Footnote 111 Several systems reported efforts to implement in their own schools what they observed in Quincy's.Footnote 112 But not all visitors were making the trip just to collect teaching practices; some were there to collect Quincy teachers. Such unfettered access to the town's classrooms introduced a worrying trend: “an unfavorable incident of the attention which our remodeled school has attracted,” the committee wrote, “is the frequent loss of good teachers, who are eagerly sought for by other towns to try there the methods learned or perfected here.”Footnote 113

Though committee members relished their schools’ visibility, they conceded that putting their teachers on display had unintended consequences. They admitted to “occasionally hav[ing] a visit from a neighboring superintendent in search of a good teacher.”Footnote 114 Later on, a history of Quincy framed visits like these less politely, writing that “other communities were watching out to annex Quincy-trained educators.”Footnote 115 Brookline, for instance, had applauded Parker's efforts in Quincy “to clear away the rubbish of dead formalities, useless requirements, and pernicious methods.” Brookline's schools, too, its committee decided, would endeavor toward principles over methods and take “especial pains to secure the best teachers to embody these ideals.”Footnote 116 Meanwhile, Principal Hall wrote of Francis Cogswell, Cambridge's popular superintendent, who visited Quincy to observe its teachers and debrief with some of them for an hour after dismissal.Footnote 117 One wonders what was discussed during that meeting. In Quincy's transformation, more affluent systems like these found a mechanism for improving teacher selection in a crowded market. Quincy's teachers were tested, their classrooms could be visited with ease, and myriad publications consistently vouched for their competence.

Although school reports in Massachusetts suggest teacher poaching by wealthier systems was becoming commonplace, Quincy felt it acutely. For a system that relied on stability and experienced teacher leaders to maintain its broad instructional program, regular turnover proved detrimental. School reports fretted over the “incubus of change.”Footnote 118 While other towns also confronted turnover, they seldom framed it in such existential terms. Quincy's school leaders, however, saw the instability as a threat to the orderly system they had created. Superintendents observed that in schools hit hardest by it, instructional quality had diminished.Footnote 119 Superintendent Sylvester Brown bemoaned the time lost “in changing teachers, even if an equally good one is secured, which is rarely the case. Months will be required to bring some of our schools where they would have been to-day but for a change in instructors.”Footnote 120

The resulting transient class of instructors, The Quincy Patriot argued, could hardly get to know the whole child, an intimate knowledge central to child-centered teaching.Footnote 121 Parents fatigued of the changes. Seeing their children fail to advance in recent years, those who sent their children to Wollaston School attributed the academic stagnation to the school's churn of instructors. They estimated that over the few short years they lived in that part of Quincy, eighteen different teachers had been employed at Wollaston, a school which typically held just five teaching posts.Footnote 122 In 1880, Brown observed, “Not a single teacher remains who was there ten months ago”Footnote 123

At times, individual teacher losses made the turnover expressly apparent to school communities. In 1884, Superintendent Aldrich mourned those of Lydia Follett of Coddington and Mary Spear of Willard:

These two ladies were so completely identified with the distinctive features of the Quincy primary schools, had both occupied positions of unusual responsibility with such entire success, that their withdrawal affords a striking illustration of the gravity of the evil now under discussion.Footnote 124

Importantly, as Quincy's notoriety grew, it also became routine for principals—nearly all of them men—to pursue higher-paying leadership positions. Before returning to Quincy as superintendent in 1882, George Aldrich left a principalship at the Adams School to manage Canton's schools. In 1880, Isaac Freeman Hall was paid a visit by four of Dedham's committee members hoping to fill a superintendent position which Hall soon took. Interestingly, Parker himself orchestrated that visit.Footnote 125 Though there were far fewer administrators than teachers, reports did not grieve their departures in the same forbidding terms as they did teachers, suggesting that exploiting Quincy's fame for professional gain was considered a more acceptable practice for men than for women.

To stem the turnover, raising teachers’ salaries was critical. After all, poor compensation was a leading reason teachers in smaller school systems left their posts so frequently, and Quincy's poor salaries had become incommensurate with its teachers’ growing value in the field. As education critic Joseph Mayer Rice explained it, “Quincy teachers are so much in demand that the mere fact of having taught for a year or two at Quincy raises the teachers above the Quincy salaries.”Footnote 126 Given the value neighboring systems placed on this experience, however brief, new teachers appeared willing to tolerate meager salaries if it earned them footholds in those settings. Even after the committee introduced salary cuts in 1877, the town's supply of candidates had scarcely changed. If anything, with Quincy's growing visibility, applicant numbers increased. In 1879, Parker reported that “a single advertisement for a teacher” yielded “hundreds of applications.”Footnote 127 The pattern was clear: just as in other towns, Quincy teachers were gathering experience there, then redeeming it for higher-paying positions elsewhere. The difference was that by gaining experience in Quincy specifically—a famous hub of innovation—teachers could market themselves more competitively in the teacher oversupply.Footnote 128

In response, The Quincy Patriot continually made the case for raising teachers’ salaries. In the summer of 1880, the schools reeling from exits by Parker and a cadre of teachers, a sobering column read:

Unless Quincy pays higher salaries than it does at present we must expect to lose all our best teachers, for it is a fact that the schools of Quincy have now come to be first-class intelligence offices, toward which the eyes of educationalists throughout the land are turned when they wish to secure good teachers who are conversant with the system which has given Quincy such a deserved notoriety.Footnote 129

Though both committee and superintendent reports agonized over the drain of talent, superintendents, by contrast, used their reports in part to advocate for raising wages. In his final superintendent report, Aldrich wrote unequivocally: “These teachers are underpaid.” In a seeming rebuke of Adams's untenable coupling of excellence and economy, he noted that Quincy's reputation hinged on “cheap teachers”—on “excellent teachers . . . inadequately paid.”Footnote 130

Parker, too, weighed in. On a hot Wednesday in June 1882, Quincy residents packed into the town hall for grammar school graduate exercises. There, before this captive audience, the former superintendent broached the teacher exodus in his keynote address. “The earnest, competent teacher is not and should not be willing to settle down for life on the salaries paid here,” he warned townsfolk, “and until better salaries are paid . . . your teachers will be constantly going to other places.”Footnote 131 While this view of self-interested teachers deviated from a longstanding “separate sphere” discourse about women teachers, it spoke in plain terms to their economic circumstances.Footnote 132 By the 1880s, calls to improve women teachers’ compensation were intensifying. That same month, writer Clara Jennison warned readers in The Journal of Education of a changing culture, of “new and more remunerative avenues . . . rapidly opening to women.” Only higher salaries, she warned, “will save to the teaching profession the best feminine talent of the country; and the city which pays most liberal salaries will command the services of the best educators.”Footnote 133

Nevertheless, Quincy's school committee continued to argue that it could not afford “to bid against richer competitors in a constantly rising scale of salaries.”Footnote 134 In some cases, adopting a strategy of wealthier systems, it rewarded raises to teachers who, “refusing tempting offers,” chose to remain in Quincy.Footnote 135 Between the tumultuous years of 1881 and 1882, for instance, Lydia Follett and Julia Underwood saw their annual salaries increase from $450 to $490. By and large, however, the committee responded to turnover in other ways, such as by enforcing stricter visitation limits and relying more heavily on the training class to build its teaching force. Both responses were fairly ineffectual. The committee eventually decided to allow visits to only one school at a time, which it justified as respecting the focus of teachers and students.Footnote 136 But reports also suggest that anxiety about Quincy teachers’ growing status motivated the decision. The committee had long felt that having guests in and out of classrooms instilled in teachers added incentive for improving their instruction and what seemed a harmless pride in their work.Footnote 137 Now they wrote about how the enlarged sense of self-worth among teachers could compromise Quincy's system. Walking back their enthusiasm for the adulation, calling the streams of visitors “embarrassing,” the committee wrote:

The number of visitors from abroad, indeed, has sometimes suggested an apprehension that we might be fostering a tendency to show and display, and that teacher and scholar alike might be injured by coming to consider themselves phenomenal exemplars.Footnote 138

The warning against vanity seemed calculated to put teachers in their place, or maybe, keep them in place. Still, the effort to protect its schools from visiting school leaders appeared inconsistent. Facing charges from Quincy residents of making a circus of their schools—of luring in crowds from afar who, in turn, lured out valuable teachers—committee members grew defensive, underscoring the schools’ public nature and calling it rude to turn admirers away.Footnote 139

The committee also looked to its training class to cultivate a more permanent workforce. Parker had established the class to build a supply of local teachers familiar with Quincy's system who could seamlessly fill vacancies.Footnote 140 The committee also hoped a locally grown teacher corps might furnish them with teachers willing to settle for “a smaller pay at home to a higher pay abroad.”Footnote 141 Other economic reasons likely underpinned this priority as well. As Joel Perlmann and Robert Margo explain, women teachers who entered the profession from city training schools “qualified for initial employment at the lowest rung—and lowest pay—of the occupational ladder.”Footnote 142 The authors observe,

Almost by definition, women progressing along such a track were less mobile than women entering a system with experience elsewhere—a fact that school boards were obviously aware of and could easily exploit by paying less for the same total years of experience or, equivalently, a negative return to tenure.Footnote 143

But in this, too, school leaders appeared conflicted. At times, they expressed reservations about depending so much on the class. Considering trainers’ youth and lack of experience, Aldrich wrote, “It is the exception, rather than the rule, to find a young woman who is competent, after a few months of training, to assume the management of one of our schools.”Footnote 144 Though the dependency on local teachers may have aligned with the Quincy Method's child-centered approach, supplying schools with teachers familiar with students’ circumstances, it is possible that, for a system which had attracted national recognition, it smacked of provincialism.

Regardless, trainers proved an unreliable supply. With demand for Quincy teachers growing, fewer pupil teachers were staying in the town's schools after their apprenticeships. This undermined the very purpose of the class.Footnote 145 Moreover, Quincy's training class was no longer a stronghold for local women. Just as wealthier systems exploited Quincy's schools to improve selection, the state's teachers similarly exploited Quincy's training class to secure an edge in the market. Class enrollment had grown considerably: in 1877, the class contained only nine students; one year later that number rose to thirty-four.Footnote 146 Over time, nonresidents increasingly enrolled, some of them already normal school graduates, “glad to serve without pay, that they might gain a thorough practical acquaintance with [Quincy's] principles and processes.”Footnote 147

A Board of Education report providing statistics on local training schools revealed that more trainers entered Quincy's class from other municipalities than from Quincy's own high school. Based on figures recorded for other training schools, this was unusual. Springfield was the only other system where this was true, and that city employed twice as many teachers as Quincy.Footnote 148 This trend likely reflected the reputation Quincy's class had earned in Massachusetts. Though other cities and towns had established their own training classes in the late nineteenth century with similar objectives, the Board of Education cited Quincy's as an exemplar.Footnote 149 Too often, the Board observed, training schools emphasized “forms of communicating information rather than . . . conditions of knowledge and mental development” and training “without constant reference to the principles of teaching.”Footnote 150 By contrast, Quincy's training class acclimated trainers to a science of teaching. Trainers became apprentices in classrooms, worked closely with full-time teachers, and gained practice applying scientific principles in context. They were often treated as full-time teachers.Footnote 151 During Hallowell's visit, the reporter watched Lizzie Morse hand her apprentice a note, which she permitted Hallowell to peruse. “Watch the children,” it read. “They are as much yours as mine to-day. Speak to them if they do anything you do not like to see. Look over their slates during the exercises. Find out their names.”Footnote 152 With the growing presence of visitors in classrooms, apprentices frequently filled in for teachers when they attended to guests.Footnote 153 In some cases, trainers may have been those observed by visiting superintendents, then subsequently lured out of Quincy.

Quincy's school leaders insisted that attending normal school after completing the training class would make “the better teacher and command a higher salary,” but trainers frequently used it as a “short cut” to the profession.Footnote 154 Since relatively few normal-trained teachers entered schools to begin with, Quincy trainers sidestepped normal training expenses, opting instead for applied experience in an acclaimed system. Here they would, Superintendent Herbert Lull observed, “get without price a practical knowledge that very few Normal Schools can give.”Footnote 155

These trends continued unabated for years. Of the twenty resignations in 1892, fourteen teachers reportedly left for “financial reasons.”Footnote 156 Although structures like teachers’ meetings and the training class may have saved the Quincy Method from completely unraveling, the town had become “a training school for the suburbs of Boston,” a mere stopover in many teachers’ careers, and a recruitment site for more powerful school systems.Footnote 157 As Parker reasoned, Quincy paid “for the training of teachers” while “outside schools reaped the benefit.”Footnote 158

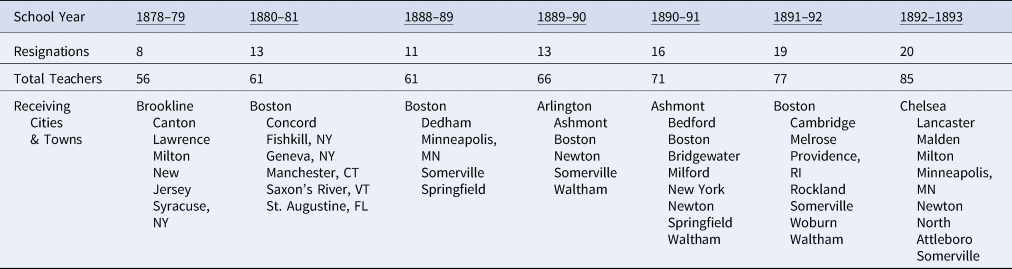

Table 2 provides detail about where resigning teachers migrated, though reporting on this data was often incomplete and recorded only certain years. For some teachers, destinations were not indicated; however, given that reports noted when a resignation was due to marriage or illness, it is possible these teachers migrated to higher-paying systems as well. On average, Quincy lost one-fifth of its teachers annually. School report data, paired with that of newspapers and periodicals, indicate that most resigning teachers drifted to wealthier Massachusetts cities and towns such as Boston, Brookline, Cambridge, Milton, Newton, Somerville, and Waltham. Others went much farther, to other Northeastern states and to the Midwest. This trend was not unique to Quincy. Throughout the nineteenth century teachers often traveled far for work. Teachers of the Northeast were most likely to do so.Footnote 159 However, evidence suggests the positions Quincy teachers journeyed to were often directly related to their Quincy experience. The New York School Journal wrote of Quincy-trained Nora Baldwin who was recruited to implement Quincy's practices in a Long Island school. The school gave her “absolute control of it in all matters save the employment of teachers.”Footnote 160 Later on, with Kate Raycroft who had moved on to teach in Boston, Baldwin led summer teacher institutes in Glens Falls, New York. The School Journal wrote of Summit, New Jersey where “any price has been offered for a ‘Quincy’ teacher.”Footnote 161

Table 2. Quincy's Teacher Resignations and Cities and Towns Receiving Quincy Teachers

Sources: Data from Quincy's annual school reports. Resignation numbers reflect only teachers, not administrators.

In certain cases, teachers advanced within Quincy before departing. Some women had occasionally become principals at their placements, an “experiment” Parker judged successful, as he found in Coddington in 1880 under Mary Dearborn's leadership—“without disparaging former principals,” he insisted—never “so well managed.”Footnote 162 These higher-status appointments often led to leadership positions elsewhere. Wollaston School principal Lillie Hicks, for example, was offered $800 annually, nearly double what Quincy's seasoned instructors earned, to lead a school in one of Boston's neighboring towns.Footnote 163 Others left public school systems altogether, entering private schools or training schools. Carrie Morse, Lizzie Morse's sister, first accepted a position at a private school in Florida, then “was promptly summoned to the charge of high-grade private schools in Louisville and Chicago.”Footnote 164 After a brief stint in Brookline's schools, she oversaw the creation of a school of observation at Bridgewater State Normal School and served as one of its early principals.Footnote 165 Mary Spear became principal of the primary teaching department in the Cook County Normal School in Chicago, where her “fund of suggestions” was “never exhausted.”Footnote 166 Later, she became principal of the model school at West Chester, Pennsylvania's State Normal School.Footnote 167

Importantly, not all of Quincy's most talented teachers left their posts. Julia Underwood was a notable exception. When Parker first arrived in Quincy, he found her “in the basement room of the Coddington School—surrounded by nearly eighty little ones.” A twenty-year veteran in the town's school system, she held her classes back then in a “half-cellar.”Footnote 168 Soon thereafter, visitors from near and far paraded to Coddington each year to see her teach. Her classroom became “a shrine for worshippers.”Footnote 169 She apparently turned down flattering offers from “nearly every State in the Union, and from the famous school for the blind in London.”Footnote 170

“Broken Lights of the New Education”: The Broader Impact of Quincy Turnover

“My year in Quincy has been a year of pleasure and profit to me,” reflected a teacher in her resignation letter. “I feel I have grown. Wherever I may teach hereafter, I shall try to keep the Quincy spirit alive within me.”Footnote 171 Come fall, she would earn a higher salary, but whether she or Quincy's other departing teachers could realistically keep alive the Quincy spirit in their new posts remained another question.

Though turnover created instability in Quincy, the scattering of Quincy teachers should have helped the town's progressive pedagogies permeate other systems. More often, however, these teachers were entering systems poorly structured to sustain and circulate their expertise.Footnote 172 In “annexing” Quincy instructors, cities and towns may have been securing more competent teachers for their classrooms, but lacking their own sustained training mechanisms or unified cultures of improvement, Quincy teachers saw their expertise fade in their new contexts.

For starters, the larger scale of some receiving systems made sweeping instructional programs difficult. Studying Quincy's through detailed observations, Lelia Patridge had underscored the broad cooperation that was required to usher instructional change across schools—that teachers, regardless of grade level, must understand “every particle” of each other's work.Footnote 173 This requisite proved a high bar in cities where, superintendents noted, “more pupils were grouped in a school, and the area of supervision was considerably larger.”Footnote 174 These systems also often lacked training structures to unite teachers under a common instructional framework. In Quincy, Aldrich called teachers’ meetings “one of the most effective agencies in promoting the life of” the schools. “Where you find a dead-and-alive school system,” he had asserted, “you will find no teachers’ meetings.”Footnote 175 Although some school systems employed variations of this structure, reports suggest that, at least in Massachusetts, they tended to be inconsistent and infrequent.Footnote 176 To illustrate, each year Quincy teachers left to teach in Boston. Examining the schools there, however, Joseph Mayer Rice found striking “unevenness” in instruction. Despite the advantages Boston's schools enjoyed, teaching varied dramatically from one classroom to the next.Footnote 177 Rice concluded that this inconsistency could be “traced largely to the fact that the instructive and inspiring teachers’ meetings are wanting.”Footnote 178

Implementations of the Quincy Method beyond Quincy shed further light on the landscape the town's teachers entered and how their expertise was practically received. Some systems applied the reform to a single subject; Fairhaven wrote of its “new system of writing, known as the Quincy method,” while Westboro boasted of a “Quincy Method of reading.”Footnote 179 Others were less successful even in this regard: Braintree's attempt to implement Quincy's hands-on approach to geography was met with resistance from teachers who found it bothersome, while Watertown merely distributed to teachers’ desks a pamphlet titled The Arithmetic Form of Course of Study in Quincy Schools.Footnote 180 Inspecting schools for the Board of Education in 1883, George Martin found that molding boards—instruments Quincy's children used in geography lessons—had become “receptacles for rubbish” in schools across the state. Martin compared the piecemeal adoptions he observed to “when new wine is put into old bottles,—the bottles have been injured and the wine has disappeared.”Footnote 181 In an 1896 article titled “The Psychology of Educational Fads,” educator Jacques Redway added the Quincy Method to a long list of pedagogical reforms that had failed to generate the extensive, lasting change promised. Redway meant no harm to these reforms’ creators or to systems that enacted them faithfully. Rather, he argued, each reform had become “a fad because it was misunderstood, misapplied, and unskillfully used.”Footnote 182

Perhaps if Quincy's visitors had spent time in teachers’ meetings in addition to the solitary classroom they would have afforded this key feature greater weight in their own systems. Absent such continuous in-service training mechanisms, there would be no science of teaching. Without that, methods divorced from principles predominated. Thus, in exploiting their Quincy experience, Quincy teachers and trainers may have been achieving better financial and professional standings, exercising agency in a relatively flat line of work, but upon entering new systems they were seldom joining focused “facult[ies] for the study of education” like the one they left behind.Footnote 183

Teachers likely confronted the differences between Quincy and their new contexts quickly. Educators compared the phenomenon to the disorientation normal school graduates often experienced, moving from progressive teaching institutions to systems rarely organized for continuous improvement, much less supervised by teaching experts. “If this graduate falls into a school where a competent principal carries the new theory into practice,” observed one journal editor, “all well. Otherwise, the young teacher succumbs, after a brief struggle, and, at best, becomes one of the numerous ‘broken lights’ of the new education.”Footnote 184 Another wrote about the status quo “superintendence—or what passes for such” that Quincy teachers would soon encounter, claiming it would “quench the beginnings of the intelligent work in the schoolroom, and sink them into mere workers at a machine.”Footnote 185

Considering this hard terrain beyond Quincy, William Reese's observation about progressive education leaders remains relevant: “It is not coincidental that the most famous American theorists of the new education were not teachers or if so left the classroom quickly.”Footnote 186 On the whole, ventured Redway, their efforts “left the [educational] superstructure a trifle firmer.”Footnote 187 Although Boston appeared interested in reforming instruction, Parker faced myriad roadblocks there and felt “tied hand and foot with Lilliputian threads of convention.”Footnote 188 Shortly into his second term there, he ultimately set his sights on Chicago, believing “the West afford[ed] the best theatre for the development of his educational theories.”Footnote 189 There he would lead the city's normal school, effectively withdrawing from public school leadership altogether.

Conclusion

Scholars have proposed several reasons for why attempts to change how teachers teach so often fall short.Footnote 190 Perhaps most notably, Larry Cuban has demonstrated that despite continued efforts to transform instruction into a student-centered affair, teacher-centered instruction stubbornly persists across the country. Examining reforms from 1880 to 1990, Cuban found that when would-be fundamental reforms entered schools, they typically became shoehorned into existing school structures, resulting in incremental changes.Footnote 191 Reflecting on this durable “grammar of schooling,” Cuban and David Tyack reframed an age-old question: “How have schools changed reforms, as opposed to reforms changing schools?”Footnote 192

Cuban has also used the case of kindergarten—once a private school innovation, now inseparable from public schooling—to consider the criteria of successful reforms. Reforms that “stick,” he concludes, oftentimes keep existing structures of schools intact, are “easy to monitor,” and engender robust constituencies that help them survive.Footnote 193 These conditions partially explain why the Quincy Method eventually faded from the limelight. The reform challenged teachers’ characteristic isolation and required careful training in the science of teaching—a major change systems were ill-prepared to make. Its effective monitoring required experts in that science of teaching, which assumed too much of superintendents at the time. Finally, the reform never gained the full-throated support of a vital constituency: taxpayers. Looking back, Principal Hall called “conservative and prejudiced parents” an enduring obstruction.Footnote 194 For all the outside interest Quincy had attracted, its committee regularly complained that parents seldom visited or showed interest in their children's schools. If they were so adamant on shaving teachers’ salaries, the committee argued, they might at least “visit the schools and see for themselves the amount of work accomplished” in them.Footnote 195

While the history presented here provides an additional case to support reform scholars’ conclusions, it also extends them. The Quincy Method's interaction with the teacher labor market reveals another complicating layer to the challenges school leaders faced when creating and sustaining system-wide innovation. This interaction is significant for a few reasons. First, it illustrates how some teachers negotiated pedagogic innovations as they became popularized in mainstream public education. A rich literature explores how nineteenth-century women teachers used teaching and public schools to advance themselves professionally. Jo Anne Preston examined women teachers’ use of the schoolhouse as a pathway toward financial independence and educational development as they rejected the narrow, maternalistic functions of teaching that reformers imposed on them.Footnote 196 Studying late nineteenth-century teachers in Providence, Rhode Island, Victoria-María MacDonald demonstrated how bureaucratization, long associated with de-skilling teachers’ work, inadvertently created social networks among women that allowed them to further their careers.Footnote 197 Other scholars have observed how women leveraged their work in classrooms to achieve greater job security and make inroads into school leadership.Footnote 198 How these advancement efforts manifested insofar as pedagogic innovations, however, is less clear. Showcasing the ways teachers used Quincy's innovations to further themselves professionally and economically helps address this gap.

Second, the Quincy case sheds light on school committees’ teacher selection. In particular, it shows how pedagogies touted in education periodicals and at conferences may have informed selection practices and illuminates the resulting dynamics between school systems as they vied for competent instructors in a market characterized by congested applicant pools and relatively limited training structures. Within this landscape, Quincy's system became a proxy for normal training. It fulfilled committees’ penchant for tested teachers. Its geographic location, situated near larger, wealthier cities and towns, only intensified the detriments of these practices.

Consequently, the Quincy case delivers a complicated answer to Tyack and Cuban's question of how schools change reforms. Certainly, implementations of the Quincy Method elsewhere concretize what these authors described as schools’ “hybridization” of reforms—of reducing them to isolated methods and jamming them into their settings such that the grammar of schooling remained untouched. But the reform-market interaction Quincy animates also suggests that understanding how schools change reforms requires closer attention to broader phenomena that play critical roles in the stability of schools and, in turn, shape the nature of classroom instruction within them. Understanding reforms like Quincy's, which asked far more of teachers in public schools, demands fuller consideration of teachers’ lives, in particular their financial circumstances. This is especially important given that many nineteenth-century White, native-born teachers were motivated by economics and relocated often in pursuit of better situations. The Quincy Method afforded them a competitive advantage in this process.

In 1879, a piece in The New-England Journal of Education called the typical arrangement of female teachers’ work “a high crime and misdemeanor.” That arrangement demanded that teachers spend most of their energy teaching students, and then “use the balance in solving the problem of how to make the week's wages meet next week's necessary expenses.”Footnote 199 It was an unsustainable arrangement, and one that teachers of relatively privileged status appeared unwilling to passively accept. School reformers’ discourse had long exalted teaching as godly work, positioning it as somehow “above money.”Footnote 200 But the Quincy Method became a cautionary tale for nineteenth-century school systems. The expectation that teachers would choose self-sacrifice over financial stability was unrealistic. Compensating their enhanced services with mere praise was not enough. Thus, in transforming teachers’ work, Quincy's school committee, as Preston found true of other New England school committees during this period, “got both more than they had bargained for and less.”Footnote 201

These unintended consequences open a new path of inquiry in the historiography of progressive education, which has largely examined classroom reform as independent from labor market forces. In evaluating whether particular reforms succeeded or failed, historians generally place greater emphasis on the groups of constituencies that influenced those reforms and the capacities of teachers and institutions to deliver on them. Scholarship on progressive reforms is additionally dominated by the pioneering figures behind them. Giants like Parker, Dewey, and Maria Montessori loom large. This is an understandable tendency, but one which can obscure how reforms were practically negotiated at the street level by teachers and schools alike. It risks distancing us from the more immediate forces on which school systems rested and that motivated how teachers were hired, which teachers stayed or left, and how school systems grappled with instability in their ranks—all patterns that held serious implications for the maintenance of coherent instructional programs and partially determined whether those reforms thrived or withered.

In the end, for many educators, Quincy's teacher mecca became a stepping stone to bigger and better things. Women teachers used it as their male counterparts frequently used the profession at large—as a brief stop along their professional trajectories. It was a place to gain not only experience, as but also expertise in innovative pedagogies that school committees increasingly saw as evidence of competence in a market stuffed with “ordinary teachers.” The Quincy Method had become influential, just not as its reformers had hoped. And though Quincy's scattered teachers would endeavor to preach the “new educational gospel” from their more prosperous pulpits, the reform's progressive example would remain an individual observance, not a structural conversion.Footnote 202