Introduction

The emergency food aid landscape has been epitomised through the ‘food bank’, as a place of charitable food-redistribution within a welfare context of austerity, aggravated by the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown measures. Times of austerity-initiated food bank use at a grand scale and a year of the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns has elevated food bank use exponentially. This article argues that there have been substantial changes within the welfare landscape that have stimulated food bank growth as an inadequate response to rising levels of poverty in times of crisis and the failure of the welfare state to address the issue of Want. Demonstrating the extent of the geospatial growth and distribution of food banks, this article views their rise through the austerity years and their important role in the pandemic as demand soared. It is argued that these events have exposed the British welfare state as an inadequate safety-net for those who cannot afford to adequately feed themselves and their families.

Increased ‘need’ triggered the opening of food banks to provide emergency relief where social security failed to meet the post-war ideal of addressing Want, and familial support failed to cope under the strain. Consequently, the rise of food poverty has led to an embedding of the food bank as an ‘accepted’, ‘normalised’ and essential voluntary response to the inadequacy of the welfare state exposed by the Covid-19 crisis. The examples used in this article examine Riches’ (Reference Riches2002) acknowledgement of a process of normalisation within charitable food banking, drawing on evidence of the last ten years. Substantially, this evidence is used in reference to Wales and the UK. However, we also recognise a similar process in other countries, struggling with austerity and Covid-19.

Background: The ascent of the food bank

It is acknowledged that poverty and hunger have been on the rise in the UK as a result of welfare reform and austerity (Lambie-Mumford and Green, Reference Lambie-Mumford and Green2017; Loopstra et al., Reference Loopstra, Fledderjohann, Reeves and Stuckler2018, Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Tarasuk2019; Alston, Reference Alston2019; JRF, 2020a; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Aliabadi, Vamos, Taylor-Robinson, Wickham, Millett and Laverty2021), necessitating the use of food banks due to declining social security and increased conditionality and benefit delay and denial. Occurring over the last ten years, Farnsworth and Irving (Reference Farnsworth and Irving2020) have likened this period to a ‘hostile decade for social policy’, identifying it as moving from one social policy crisis to the next. Notably, key changes to the amount of welfare, and the mechanism by which it is delivered, were introduced by governments since 2010. Research conducted by Beck and Gwilym (Reference Beck and Gwilym2020) evidences how austerity policies have facilitated the increase of modern-day food poverty, exposing more people to food poverty during the Covid-19 crisis – moreover, facilitating changes in society’s understanding about food poverty and its response to the crisis of food insecurity (Beck, Reference Beck2018).

The UK food bank, as a provider of emergency food aid, has been discussed elsewhere (Lambie-Mumford, Reference Lambie-Mumford2013; Price et al., Reference Price, Barons, Garthwaite and Jolly2020; Beck and Gwilym, 2020). The focus of this article is to contextualise the establishment and growth of food banks as a consequence of failings in the welfare state, further illustrated by the Covid-19 crisis. With almost a quarter of its population living in poverty (JRF, 2020b), Wales is used as a typical example of the food poverty crisis and food bank growth in the UK. UK food banks are divided between two main providers; either the Trussell Trust, as the national provider (described here as ‘Foodbank’), or those that are independent of the Trust (described here as ‘food bank’). Founded in 1997, the Trussell Trust supports a nationwide network of food banks and campaigns for ending food poverty in the UK (Trussell Trust, n.d.). The independent food banks, on the other hand, are autonomous of the Trust – and are also, notably, independent of each other (Beck, Reference Beck2018). Since the independent food banks are more disparate, the effect of Covid-19 has hit them hardest with problems in sourcing food and older volunteers having to self-isolate (Power et al., Reference Power, Doherty, Pybus and Pickett2020).

Evidencing the early rise of emergency food provisioning in the UK, Perry et al. (Reference Perry, Williams, Sefton and Haddad2014) argued that increased visits to food banks occurred because of austerity policies – namely, the economic climate and tightening of public expenditure. Moreover, they argued that the rise in food bank use, following the 2008-2009 credit-crunch crisis, was accompanied by the decline in real incomes for the poorest in society and major changes in the way that welfare is provisioned. In 2014, Cooper et al. identified that the cost of both food and fuel had risen 43.5 per cent between 2005 and 2013, yet incomes had not risen accordingly, meaning that people were spending more on food and fuel, yet buying less (2014). Lambie-Mumford and Dowler (Reference Lambie-Mumford and Dowler2015) have attributed this to a period of change, whereby the combination of austerity and rising food and fuel prices forced people into seeking charitable food help. During this period no new welfare response was made to the emerging crisis of food poverty.

Elucidating the noticeable rise in food bank numbers, Lambie-Mumford (Reference Lambie-Mumford2013: 78) measured the growth of the Trussell Trust Foodbank network, and the development of the franchise during the Labour Government (1997-2010) and the first two years of the Coalition Government (2010-12). Arguing that the Trussell Trust Foodbank network grew out of welfare reforms, the number of Trussell Trust Foodbanks by 2010 stood at fifty-four UK-wide. Lambie-Mumford (Reference Lambie-Mumford2013) reasons that the expansion of the Trussell Trust Foodbank network during the first years of the Coalition Government was exponential, resulting in 201 Foodbank openings by April 2012.

Across the ensuing years of austerity, food bank numbers continued to expand in all the nations of the UK as levels of poverty increased (Weekes et al., Reference Weekes, Spoor and Weal2021). Trussell Trust data for the financial year ending in 2018 shows that the main driver behind Trussell Trust Foodbank use was associated with low incomes (28.49 per cent), followed by benefit delays (23.74 per cent) and benefit changes (17.73 per cent) (Trussell Trust, 2018a), and are indicative of structural factors of poverty. This is especially highlighted through the welfare reforms instigated by the Welfare Reform Act 2012, in which social security underwent root and branch reform, both in the way it is assessed and in how it is delivered (Shildrick et al., Reference Shildrick, MacDonald, Webster and Garthwaite2012). This same position has been updated by Jenkins et al. (Reference Jenkins, Aliabadi, Vamos, Taylor-Robinson, Wickham, Millett and Laverty2021) and their systematic review of evidence that supports the assertion that welfare reforms are associated with increased food insecurity. Further data obtained from the Trussell Trust (2020a) show that by 2020, coinciding with almost a decade of austerity, the number of networked Foodbanks stood at 1,393 (England: 1,107; Scotland: 129; NI: 40; and Wales: 117). Similarly, and additional to the Trust’s figures, the Independent Food Aid Network (IFAN) estimate that, over the same ten year period, independent food banks reached 961 nationally (Goodwin, Reference Goodwin2020). It is argued in this article that food banks have now become the safety-net for a residualised welfare state and that the food bank has become embedded and normalised. Riches (Reference Riches2002) has identified that this process constitutes a three-stage progression. Initially, he recognises that the embedding of food banks, as part of a social security system, entails the development of a strong charitable national food bank organisation. Following this, the second stage sees the expansion of corporate links with the national charity provider – namely, the formation of national partnerships with corporate food companies including supermarkets and receiving favourable support and coverage in the media. Finally, Riches (Reference Riches2002) argues that a link develops between the national food bank and the government formalising governmental support for a charitable safety-net in times of food insecurity, promoting welfare residualisation and reform.

The beginning of the austerity decade saw the Conservative-led Coalition Government strive to reduce the financial deficit at the heart of the Great Recession. As Shildrick et al. (Reference Shildrick, MacDonald, Webster and Garthwaite2012) identify, major cuts to public expenditure were intended and that at least £15 billion of savings would be made from the welfare budget. As Shildrick et al. (Reference Shildrick, MacDonald, Webster and Garthwaite2012) continue, this was a political decision, ideologically driven with the intention to tackle what the former Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne had considered to be a culture of welfare dependency as a lifestyle choice. The very notion of welfare dependency as a lifestyle choice was one that had been previously popularised in a series of articles in The Sunday Times, by American Sociologist Charles Murray (Reference Murray1990), manifestly as an ‘Underclass’. The Underclass discourse sees poverty being perpetuated by individual choice where the only escape is via ‘authentic self-governance’ (Murray, Reference Murray, McLaughlin, Muncie and Hughes2005: 140), thus perpetuating the desire for a smaller welfare state (Murray, Reference Murray1994).

This change is also seen as a ‘hardening’ of welfare policy (Jensen and Tyler, Reference Jensen and Tyler2015: 484), through punitive action, evidenced by policies of the Welfare Reform Act 2012 such as the introduction of The Work Programme, or the transferring of the Social Fund over to hard-pressed local authorities, and finally the Under-Occupancy Penalty (known as the ‘Bedroom Tax’). The most significant change was the introduction of a whole new system ‘Universal Credit’ (UC). This hardening of welfare policy via UC also saw a heightened sanctioning of benefits and payment delays, with new claimants having to wait a mandatory five-week period before receiving their first payment (Prayogo et al., Reference Prayogo, Chater, Chapman, Barker, Rahmawati, Waterfall and Grimble2018; Lambie-Mumford and Loopstra, Reference Lambie-Mumford, Loopstra, Lambie-Mumford and Silvastii2020). These changes have been highlighted by Cloke et al. (Reference Cloke, May and Williams2016: 703-704), who propose that ‘the very visible presence, and contested politics, of food banks in the UK has become iconic of social injustice and welfare failure’. Here, they argue that the existence of food banks has unwittingly expedited the roll back of the welfare state, as volunteers and food banks become the sticking plaster over the gaping wound. More so, in an attempt at increasing signposting, the movement of welfare advisors into food banks hints at welfare retrenchment and encourages their normalisation. The descriptive term of food banks as ‘sticking plasters’ has been used by academics and civil society as a way of illustrating how much of a temporary solution food banks were meant to be (Butler and Sherwood, Reference Butler and Sherwood2020). The years of austerity and the Covid-19 crisis have demonstrated that food banks are no longer a sticking plaster but are the new safety-net.

Methods

Data collection for this article occurred in two stages: first was a detailed project mapping all food banks in Wales from 1997 to 2015 and took place in 2015; the second stage was more recent and involved gathering secondary data on the use of food banks leading up to and including the Covid-19 pandemic. The first stage of data collection saw the gathering of information from the Trussell Trust website, making use of their interactive GIS data-mapping programme, illustrating the location of every Trussell Trust Foodbank distribution centre. Here, Foodbank postcode-data from the twenty-two Welsh local authorities was extracted and compiled into a database and applied to ArcGIS 10.5.1. Next, desk-based media research systematically verified their opening dates and allowed for both spatial and temporal data to be combined. The same method was applied to independent food banks, creating a full GIS representation of the Welsh food bank landscape. The database of geo-locational data illustrates a truer landscape of food bank distribution, delineating the geographical spread of both the Trussell Trust and the independent sector. This database also now allows for the distribution and growth of food banks to be illustrated on a year-by-year basis.

The findings were updated in February 2021 through a secondary analysis of new Trussell Trust and IFAN data. We were particularly interested in discovering what the effects of Covid-19 and lockdown had been on food bank use since the start of the first lockdown in March 2020.

Ethics

As part of a larger research project ethical approval for the first wave of data collection was granted from the School of History, Law and Social Sciences at Bangor University in February 2014. Ethical approval was further granted for the second stage of the research from the School of Health and Society at the University of Salford in November 2020.

Findings: A new safety-net in times of austerity

The geographical locale of all food banks across Wales, as a representation of food bank growth in the UK, evidences a steep rise in the number of food banks opening as austerity policies took hold following the Welfare Reform Act (2012), revealing that food bank growth peaked in 2013. Thus, the spread of food banks illustrated the changing landscape of welfare with welfare retrenchment in times of austerity and a dependency on the food bank as a safety-net.

The distribution of food banks January 1998-June 2010

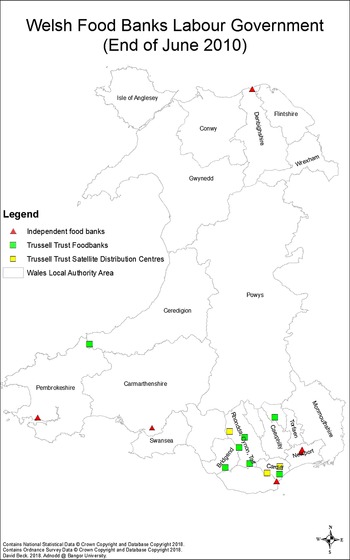

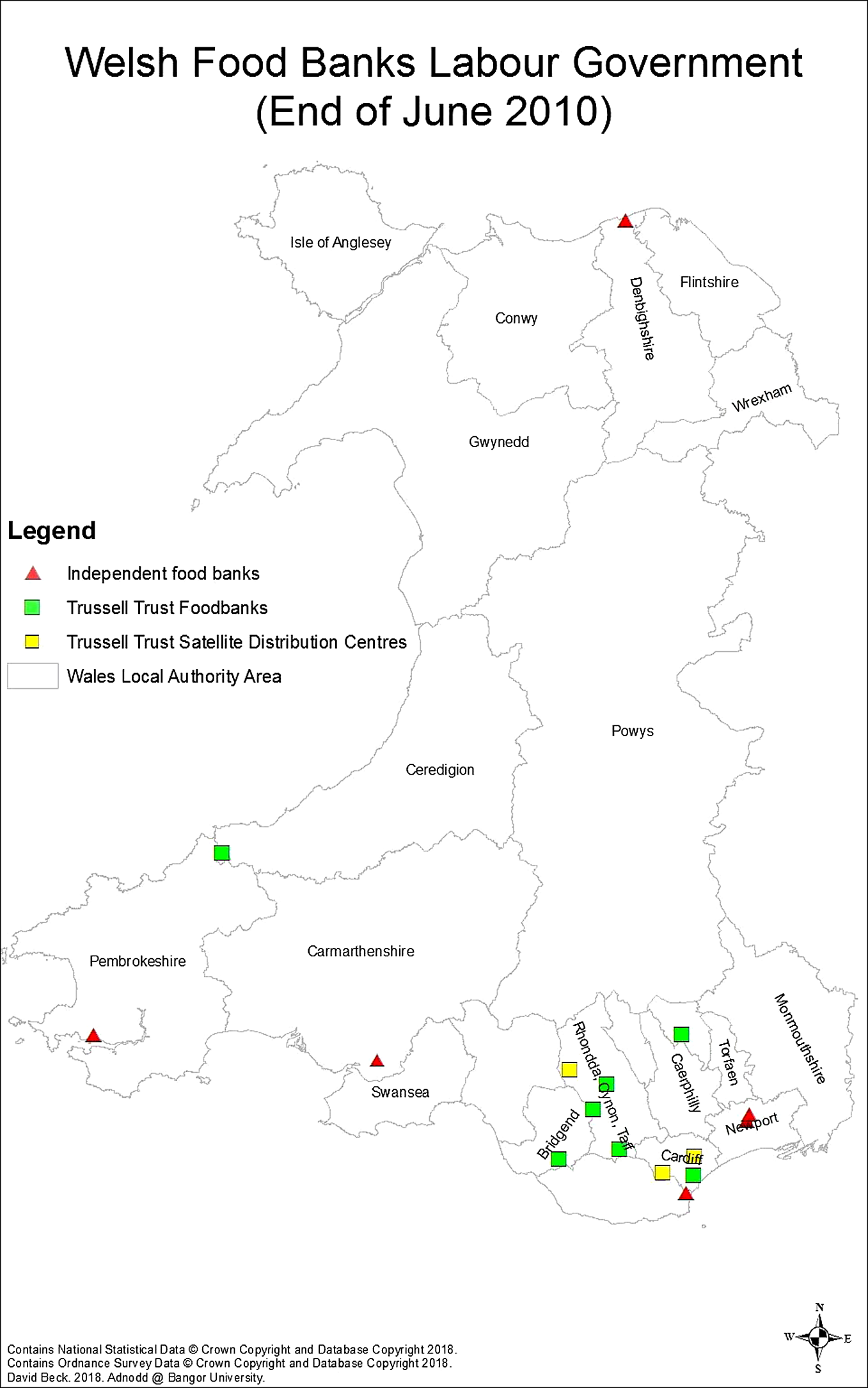

Table 1 above and Map 1 illustrate the number and geographic distribution of Welsh food banks 1997-2010. Following the opening of the first Welsh food bank in Newport in 1998 (Beck, Reference Beck2018), the number of food banks under the twelve years of New Labour rose to sixteen by 2010. As Map 1 illustrates, these were mainly in the post-industrial and deprived areas of South Wales, and one in the North. In addition to the Trussell Trust Network, independent food banks advanced across the Southeast and West of Wales operating in Newport (x2), Penarth, Llanelli, and Milford Haven, in addition to the only North Wales food bank in Prestatyn.

Table 1 The Number of New Food Banks in Wales under the Labour Government (1997-2010)

Map 1. The Welsh food bank landscape and the Labour Government

Cumulative count of food banks under labour

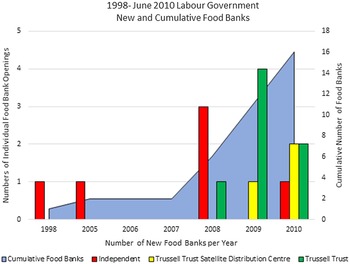

The development of the Welsh food bank landscape remained fairly static between the opening of the first food bank in Newport (1998), and the start of the financial crisis in 2008. Between 2008 and 2009, Wales saw the addition of a small amount of food banks, both organised by the independent sector and Trussell Trust Network. Cumulatively, Figure 1 shows an increase in new food banks through an eighteen-month period from January 2008 to the General Election in May 2010, from two to sixteen food banks.

Figure 1. Individual and cumulative count of the new openings of food banks in Wales under the Labour Government

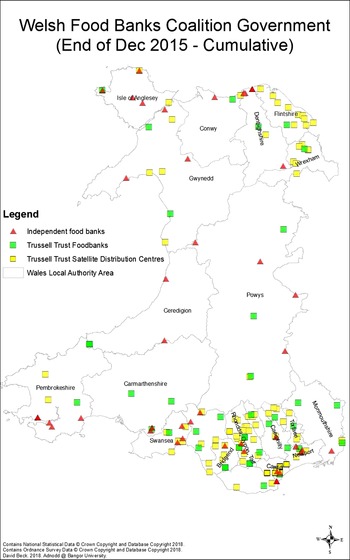

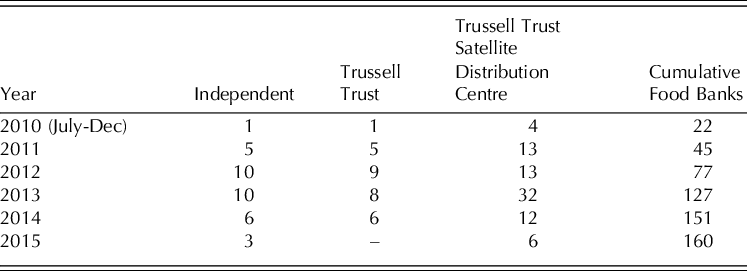

Rising from sixteen food banks in June 2010, Table 2 and Map 2 below illustrate the development of food banks across Wales, between the start of the Coalition Government in May 2010 and the end of the first stage of data collection in December 2015. The figures show how food bank numbers during the Coalition Government’s austerity years, ended with a total of 160 food banks in Wales. An additional 144 food banks across both the independent and the Trussell Trust Network had been added in Wales during the austerity years as a response to the crisis of food poverty: with welfare conditionality and benefit sanctions a major driver of food bank growth in times of austerity (Loopstra et al., Reference Loopstra, Fledderjohann, Reeves and Stuckler2018). Voluntary community groups responded to the rising demand of food insecurity by opening more food banks, highlighting the inadequacy of the welfare state to deal with food poverty.

Table 2 The Number of New Food Banks in Wales under the Coalition Government (2010-2015)

Map 2. The Welsh food bank landscape and the Coalition Government

The distribution of food banks July 2010-December 2015

Cumulative count of food banks under the coalition government

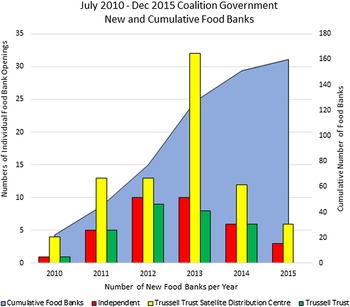

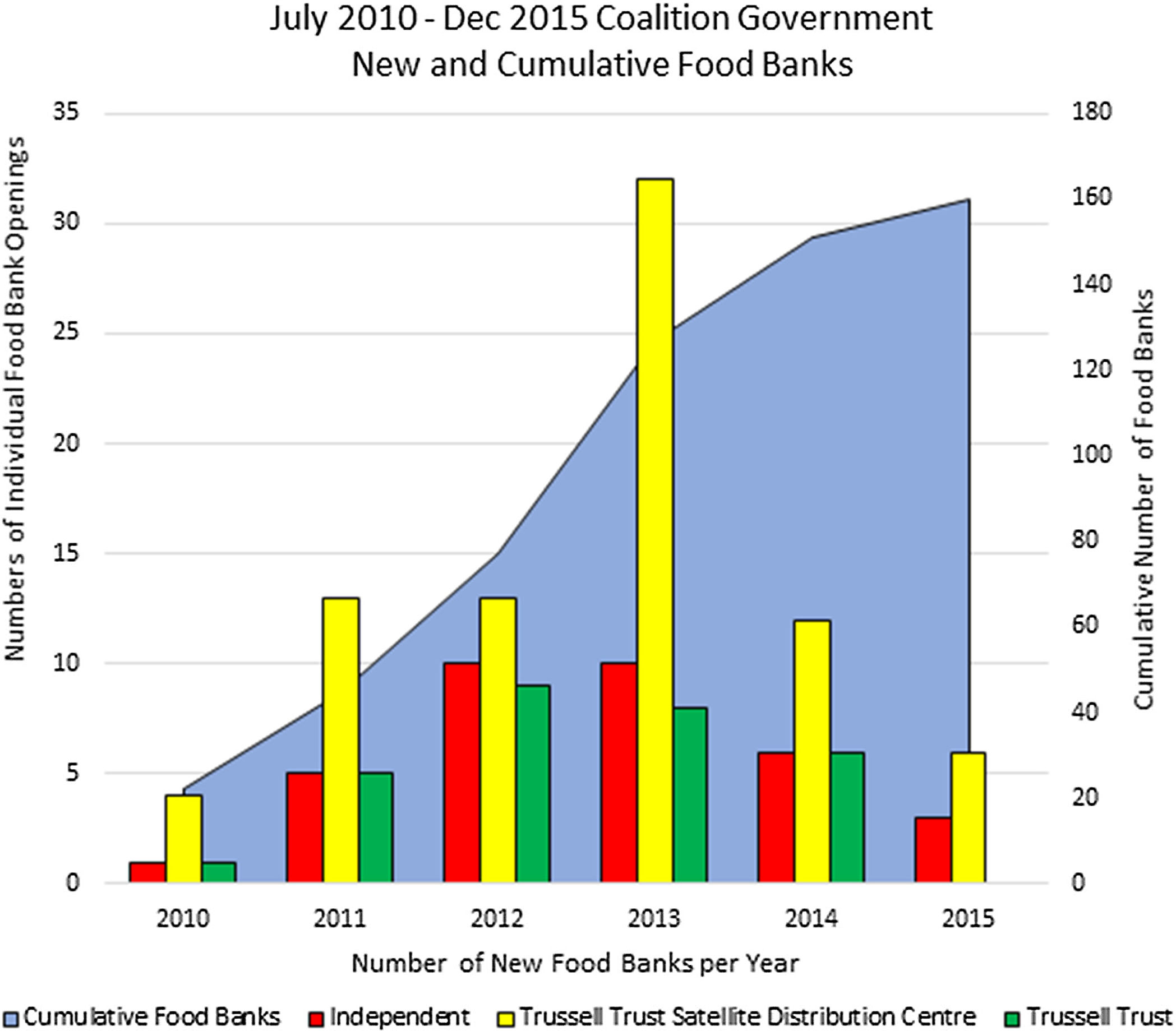

Welfare reform was a flag-ship policy of the Coalition Government, spearheaded by Iain Duncan–Smith as Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, and by 2013 it was taking its toll (Lammasniemi, Reference Lammasniemi2019). As Figure 2 below illustrates, the opening of the highest number of food banks came in 2013 as a surge of new Trussell Trust Satellite Distribution Centres were opened in the wake of the Welfare Reform Act 2012 and increased welfare conditionality.

Figure 2. Individual and cumulative count of the new openings of food banks in Wales under the Coalition Government

Thus, there was an astonishing rise in the number of food banks operating under the Coalition Government during the years of austerity. As Figure 2 shows, the growth of food banks has a strong correlation with welfare reform, significantly the Welfare Reform Act 2012, as the increase of people detrimentally affected by welfare retrenchment and austerity triggered an increase in those seeking emergency food assistance (Caplan, Reference Caplan2016; Garratt et al., Reference Garratt, Spencer and Ogden2016; Prayogo et al., Reference Prayogo, Chater, Chapman, Barker, Rahmawati, Waterfall and Grimble2018). We argue that the rise in food banks has been a safety-net response by volunteers plugging the gap of welfare state provision during the austerity years. Evidence also highlights that the introduction of the ‘Big Society’ allowed for an easing of the effects of welfare retrenchment – with community groups and voluntary organisations filling the void left by austerity (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Goodwin and Cloke2014). Highlighting the significance of the ‘Big Society’ approach regarding food banks, findings from Price et al. (Reference Price, Barons, Garthwaite and Jolly2020) show that it is this ‘Big Society’ thinking that leads local citizens to donate to food banks as an act of active participation within their local community. Owing to the rise in food bank numbers, the food bank has become a vital provision that referral organisations have come to depend upon, as a means of helping people within their communities to bridge the financial gap caused by a rapidly retrenched social security system (Beck and Gwilym, Reference Beck and Gwilym2020). Evidence from The Trussell Trust on the numbers of people requesting help from their Foodbanks shows an increase year on year, as visits to Foodbanks have risen from 113,264 in 2012, up to 586,907 in 2017 (Trussell Trust, 2017). This 2017 figure also highlights that there were 67,565 more people making use of the Trussell Trust Foodbanks than in the year 2016. Data from the Trussell Trust in Wales have similarly shown an intensification of people requiring emergency food assistance from their Foodbank network. In their end of year figures (April 1st, 2017-March 31st, 2018), the Trussell Trust report that 98,350 meals were given out from their Foodbanks in Wales alone and that this had risen to 174,816 meals in 2019 and 211,179 meals by 2020 (Trussell Trust, 2020b).

The 2020 mid-year statistics from the Trussell Trust include partial data obtainable from the impact of the first wave of UK Covid-19 lockdown. More recently, the exacerbated Covid-19 crisis and rolling-lockdowns have only served to perpetuate this situation even further for many. Nationally, the latest data from the Trussell Trust shows that 1.9 million parcels were distributed from Trussell Trust Foodbanks during the fiscal year 2019-2020 (Trussell Trust, 2020a). Independent food banks paint a similar picture, with the UK’s approximately 961 autonomous food banks distributing 354,613 three-day food parcels between February and November 2020 (Goodwin, Reference Goodwin2020). In addition, Edmiston et al. (Reference Edmiston, Robertshaw, Gibbons, Ingold, Baumberg Geiger, Scullion, Summers and Young2021) highlight that support is received in multiple ways, be this either from friends, family, or local charities, showing that food poverty is not always experienced via the food bank. Many more people will have managed via other coping strategies, including skipping meals and receiving familial support (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Farag and Baines2016). Therefore, our data only shows a fraction of the true numbers of food insecure people, as we acknowledge that not everyone who is food insecure uses a food bank, but it is clear that everyone who uses a food bank is food insecure.

Lockdowns, the temporary closure of many low-wage industries introduced as a Covid-19 transmission prevention policy, aggravated levels of poverty. For example, between July and October 2020 the ONS recorded a rise in 370,000 additional redundancies (ONS, 2020). Those from the low-wage economy who were not laid-off were provided with a temporary reprieve with the introduction of the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (Furlough). This was intended as short-term support offering up to 80 per cent of actual wages, a substantial reduction for those on the breadline. Employees on low pay were far more likely to be placed on furlough; 28 per cent compared to 17 per cent of top earners (Tinson, 2020). It was estimated that about 800,000 people would lose their jobs in hospitality and retail as a result of furloughing (Barker and Russell, Reference Barker and Russell2020). Moreover, there is concern for some whether their jobs will continue beyond the period when furlough is paid (Tinson, 2020). In their recent research on the impact of Covid-19, unemployment, and food insecurity, Loopstra et al. (Reference Loopstra, Reeves and Lambie-Mumford2020: 10) find that levels of food insecurity were high for both furloughed workers and the unemployed, especially when compared to those still engaged in employment. Moreover, Trussell Trust data (2020c) evidences that, during the start of the pandemic, visits to the Foodbank increased by 81 per cent with around half of all Trussell Trust Foodbank visits in this period being made by people who had never used the service before. Given the rise in food bank use over this period, we consider that furlough may have provided some financial insulation for some, but overall it was a deficient poverty prevention measure.

As sample data from the independent sector show, the impact of Covid-19 on the numbers of people seeking assistance from food banks has been almost overwhelming. From eighty-three sampled food banks in the UK, Goodwin (Reference Goodwin2020), highlights comparisons between February 2019 and February 2020 showing that there was an 18 per cent increase in the number of three-day emergency food parcels distributed. However, and in line with the start of the first national lockdown in March 2020, comparisons between April 2019 and April 2020 show a substantial increase of 171 per cent in three-day emergency food parcels distributed. Indicative of the lack of formal support available from the state, data from the same sample also compared May 2019 with May 2020, this time showing that the high increase acknowledged in April 2020 had increased further to 190 per cent (Goodwin, Reference Goodwin2020).

These numbers speak volumes about the rise in food insecurity during the decade of austerity and highlight that precarity was amplified during the national lockdown with food banks forming a significant safety-net for the most vulnerable. At the same time shoppers in UK supermarkets also faced rising precarity and insecurity in purchasing food, as stockpiling and panic-buying took hold (Benker, Reference Benker2021). Research conducted by the Food Foundation (2021) also evidenced the impact that panic buying had on the ‘just-in-time’ supply chains used by supermarkets, identifying them as a contributor to food insecurity. Corresponding evidence from the British Retail Consortium (2020) also confirms that almost £1 billion of additional food was purchased at the start of lockdown. This had a compounding effect on food banks and their ability to be able to procure enough food during lockdown, as people competed to gather enough food for themselves. Donations into food bank baskets reduced at the same time as numbers using food banks increased (Church Action on Poverty, 2020).

It is clear from this data that the food bank has become the replacement safety-net for the welfare state as the welfare state failed to protect people from destitution. In the following discussion section, we argue that the findings from our research highlight the inadequacy of the current social security system as a means of support, and that this has been eroded through failed welfare policy. The lack of state support during the last ten years of austerity has both caused the need for food banks and driven their increase.

Food banks: A normalised safety-net in times of crisis

We argue in this article that the food bank exists as a safety-net for the failure of the welfare state to address the issue of ‘Want’, one of the five giants to be tackled by Beveridge and the post-war government. Beveridge wanted to address Want, or poverty, through social security benefits and allowances to keep the household standard of living above the national minimum. The inadequacy of the welfare state’s response to the issue of Want – in this instance, food poverty – left a gap which has been filled by the food bank as a response to the crisis of food insecurity, driven by austerity policies and the pandemic. The evidence presented in the previous section illustrates how the years of austerity had a profound effect on the ability of individuals to manage financially. Significant development of emergency food banks reached a pinnacle in 2013, when, in a single year, as our evidence from Wales identifies, fifty new food banks opened their doors. This simultaneous rise in both independent and Trussell Trust food banks was a response to benefit restrictions and welfare spending cuts across the UK (Beck, Reference Beck2018). These problems were exacerbated significantly later with the introduction of UC with benefit delays, sanctions and denial.

The surge in people experiencing food poverty, and thus food bank use, we argue follows the pattern set by the USA and Canada where food banks are embedded in the welfare landscape. As our data makes clear, the position of the Trussell Trust as a national charitable food banking organisation meets the first stage of Riches’ (Reference Riches2002) three stage process of food bank embeddedness. Riches (Reference Riches2002) notes that the rapid emergence and embedding of charitable food aid provision is a significant indicator of the failure of the welfare state for first-world societies, and that they are an inadequate response to issues of social exclusion and the government’s responsibility over food rights.

Second, and confirming Riches’ analysis (2002), our research also highlighted that the next stage of embedding food banks in the UK has been achieved via the Trussell Trust during the last decade, establishing national corporate links with several of the UKs largest supermarkets: Tesco, Waitrose, Morrisons and Asda, combined with partnership links with the UK’s main food redistribution charity Fareshare. This three-year partnership established in 2018 saw the Trussell Trust, Asda and Fareshare enter a £20m deal, that secures financial aid to develop a ‘Fight Hunger Create Change’ programme. This programme also aims to develop the Trussell Trust’s ‘More Than Food’ project that includes the development of anti-hunger courses and strategies. However, what it also does is establish a delivery structure of redistributed fresh food into the Trussell Trust Foodbank network (Trussell Trust, 2018b).

Fisher (Reference Fisher2017) argued that in an approach to tackling food poverty, and not addressing its root causes, hunger becomes open to this form of corporate philanthropy. Corporations now appear as a solution to tackling food poverty and thus absolve the state of its responsibility. Yet crucially, the state has a responsibility to protect its citizens from hunger and acknowledge peoples’ ‘right to food’ through its ratification of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) agreed upon as far back as 1976 (End Hunger UK, Reference End Hunger2019).

Further, as the state neglects such responsibility, it simultaneously ignores any association with the root causes of poverty such as a failing minimum wage and low-income levels not meeting the cost of living. It is this failure to address the root causes of hunger that is facilitating the embedding of food banks into our social welfare landscape, and expediates the corporate response to hunger, or, as described by Fisher (Reference Fisher2017: 8), the ‘anti-hunger industrial complex’. Within this complex, food providers, such as large supermarkets, are encouraged to be involved in demonstrating ‘corporate social responsibility’ towards communities and have been supported to take an active role in the plight of the food poor. Fisher (Reference Fisher2017) further contends that the process of addressing hunger through a societal response (such as through a food bank) also works to shift the blame of what causes food poverty in the first place.

Finally, in achieving Riches’ (Reference Riches2002) third stage of food bank embedding, our evidence shows that the UK government has now formalised this final phase. Encouraged by the Covid-19 pandemic and the increasing numbers of people resorting to food banks, the government has announced a package of support available for local authorities through the Covid Winter Grant Scheme. This scheme promises local authorities a share of £170m paid via the Department for Work and Pensions to provide localised support to the most in need across England (Gov.UK, 2021), with equivalent monies made available for Wales, Northern Ireland, and Scotland (for example, Gov. Wales, 2021). The £170m includes £16m diverted to fund local charities who work with frontline organisations delivering food aid. This portion of money is being used by Fareshare and Wrap (Waste and Resources Action Programme) to redistribute food into food banks (Gov.UK, 2020). As is clear from Riches’ (Reference Riches2002) established stages, this marks the formation of definitive links between the structures of UK social security and charitable redistribution, further marginalising the role of the welfare state.

Food banks have, therefore, become the answer to the problem of rising food poverty as the state retreats in times of austerity. The UK government has been criticised for allowing the embeddedness of food banks (Riches, Reference Riches2014), as has happened in both Canada and the USA, and for the depoliticisation of hunger (Beck, Reference Beck2018). For Fisher (Reference Fisher2017) in the USA, the depoliticisation of food poverty only served to entrench the hunger problem further into society, simultaneously shifting the burden of responsibility over to society. The same situation can be observed in the UK with the establishment of austerity-driven emergency food providers – emblematic of a small welfare state in neoliberal times (Mirowski, Reference Mirowski2014). For Fisher (Reference Fisher2017), the non-profit role as a public response to food poverty alleviation becomes a ‘double-edged sword’, as the public become accepting of this responsibility, resulting in pushing further away any chance of the state meeting its responsibility, as envisaged by Beveridge.

However, we argue for a fourth stage of food bank embeddedness – namely, that food banks become both normalised and accepted by society, identifying that they are emblematic of the ‘Big Society’ writ-large. For Slater (Reference Slater2014) the Big Society is indicative of the belief that the welfare state has run its course and that volunteerism and donations are being politically encouraged as a new obligation. A position supported by Price et al. (Reference Price, Barons, Garthwaite and Jolly2020), that the motivation to donate to food banks centres on the desire for citizens to play an active role in supporting their society. This level of social acceptance of food banks was illustrated in 2016 by an argument between the supermarket chain Asda and its customers following the removal of food bank collection baskets. Asda’s policy saw the removal of all unmanned charity collection baskets in stores across the country (Harris, Reference Harris2016a) signalling the end of Asda customers’ donations. However, following a social media uproar, and a challenge put forward by the charities affected, including the Trussell Trust, Asda decided to reinstate the collection baskets (Harris, Reference Harris2016b).

The siting of food bank collection baskets at the end of supermarket tills and elsewhere are now commonplace. They represent a shift away from addressing ‘Want’ through social security and a shift towards voluntary giving (Slater, Reference Slater2014). Their removal and the subsequent public disquiet only served to show the growth of social acceptability of charitable food as donors realised their value for those in need. Thus, confirming a new final stage of food banks becoming embedded: not just within society, but also within our social conscience in parallel with acceptance of lower financial levels of social security. Yet, it is important to understand that the social acceptance of charitable food is mostly one-sided. As many academics have shown (for example, van der Horst et al., Reference Van der Horst, Pascucci and Bol2014; Purdam et al., Reference Purdam, Garratt and Esmail2016), receiving food from a food bank is loaded with the emotional responses of shame and stigma.

Ronson and Caraher (Reference Ronson, Caraher, Caraher and Coveney2016) argued that food banks act as no more than a charitable attempt to solve socio-political problems which they cannot solve (Seibel, Reference Seibel and James1989). This serves, in effect, to deflect from the real issue, that of welfare reform as the main cause of food bank growth (Beatty and Fothergill, Reference Beatty and Fothergill2016; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Aliabadi, Vamos, Taylor-Robinson, Wickham, Millett and Laverty2021). In discussing the role of the non-profit sector (of which food banks operate within) Seibel (Reference Seibel and James1989), identifies that there exists an inherent failure within the non-profit organisations, especially where they are performing a role once occupied by a statutory body. Describing them as ‘shunting-yards’ providing ‘organisational slack’, charities (such as food banks) enable the government to off-load their responsibilities onto the non-profit sector during austere times (1989: 188). The level of involvement from the non-profit organisations reflects the illusion that help is at hand, as food becomes increasingly supplied by the emergency food aid providers.

The fourth stage (normalisation and acceptance) necessary for the effective embedding of food banks acknowledges that there has already been a wider public acceptance of food banks as a substitute for welfare. This fourth stage, highlights that the food bank has become the new welfare safety-net, catching those who fall through the official social welfare system. Acceptance of food banks in society means that they become recognised as a legitimate method of food sourcing in times of austere need, and they reflect changes made to the welfare state. Acceptance of food banks has also been ‘normalised’, perhaps even ‘encouraged’, through the changing language of ‘welfare’, ‘culture of benefit dependency’; and the demise of concepts such as ‘social security’ (Lister, Reference Lister2021). What this has sought to do is to shift the responsibility for addressing food poverty away from the state.

As we have shown, food banks fit well with a neoliberal politic that ideologically seeks to combine austerity and welfare state retrenchment. As Farnsworth and Irving (Reference Farnsworth and Irving2020) argued, 2010-2020 was marked as a decade of austerity and our research here underpins this position empirically highlighting a move to a reduced state welfare provision. We have also argued that the situation has been significantly compounded by the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown measures. All the indications are that austerity measures will continue throughout the third decade of this century as the government seeks to reduce the growing national deficit made worse by the pandemic.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article has argued how welfare reform and retrenchment has encouraged the development of a charitable food banking landscape in response to food poverty in times of austerity and the Covid-19 pandemic. The role of the food bank has increased where the welfare state has reduced. We have argued that the intensification of new food banks in 2012 and 2013 across Wales coincided with the start of UK wide welfare changes under the Welfare Reform Act 2012. We have presented the results of a mapping exercise of food bank growth within the context of the changing face of food poverty in the UK, with a focus on Wales. This article has evidenced that the growth of food banks was driven by a policy to restrict welfare through increasing conditionality and reform. Welfare changes illustrate how people become more vulnerable due to social welfare legislation and policies as communities began to provide an emergency safety-net and support for the most defenceless. The article has thus argued that, as food banks become more visible throughout society, they also become more embedded as a result. Normalisation of food banks is evident in the presence of the Trussell Trust Foodbank Network; coupled with their association with supermarkets and Fareshare. Familiarity with the Trussell Trust Foodbank Network as a ‘brand’ of food banks has been propelled through the media representation of the Trussell Trust, as being the food bank: it has become the recognised embedded provider. Embedding of food banks, as a community driven response, instead of universal social security provision, has positioned food banks, and the Trussell Trust, predominantly as a charitable safety-net at times of crisis and welfare state retreat.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support and guidence of Dr Eifiona Thomas Lane (Bangor University) and Mr Ian Harris (Bangor University) in both the supervison and data visualisation of this work.