Graduate training in psychology is both an exciting and a challenging time for all students. However, there are both historical and contemporary elements that can make training in graduate programs in psychology particularly unique for students of color. The purpose of this chapter is to provide an overview of the realities but also the possibilities for graduate trainees of color in psychology. This chapter defines students/trainees of color using the US Bureau of the Census definition of color: African/American/Black, American Indian, Alaskan Native, Asian-American/Pacific Islander and Hispanic/Latino(a)/x. We also utilize the term Black Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) when referring to these trainees of color.

Who Are We?

Positionality concerns the description of one’s social location, privilege, and areas of marginalization. We feel that it is imperative to outline who the writers of this chapter are, as it informs why we decided to agree to pen this critical chapter. Notably, we are three current and former graduate trainees of color. We have all been trained at a bevy of Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs), which we note have provided both immense challenge and opportunity for us as Black psychologists. One of us (S. Jones) also now has the distinct privilege of training graduate students, both White and BIPOC, which has provided a full circle experience.

Who is the Intended Audience of This Chapter?

If there were only one demographic that were to read this chapter, it is our hope that BIPOC graduate trainees will find the contents herein useful. From that perspective, this chapter could be viewed as a FUBU (For Us By Us) offering, an homage to the 1990s Black-owned clothing line, or Solange’s (2016) R&B track of the same name from her award-winning album A Seat at the Table. However, we also believe that the experiences highlighted in this chapter and navigated by many BIPOC graduate trainees may serve as fruitful multicultural understanding for non-BIPOC graduate students in psychology who count themselves as allies or accomplices of BIPOC trainees of color. According to Reference AyvazianAyvazian (1995), allyship is “intentional, overt, consistent activity that challenges prevailing patterns of oppression, makes privileges that are so often invisible visible, and facilitates the empowerment of persons targeted by oppression” (p. 6). Being an accomplice (or co-conspirator) has been described as a developmental step forward in allyship, one that has been described as connoting more risk-taking on the part of the accomplice (Reference Suyemoto, Hochman, Donovan and RoemerSuyemoto et al., 2021). Simply put, we would implore White graduate trainees to not shy away from this content, as it could aid you in having some context for understanding and supporting your fellow cohort-, class-, or lab-mate.Footnote 1 Whether accomplice, ally, or BIPOC trainee, it is our hope that this chapter will be edifying.

Chapter Outline

In the sections that follow, we take up three principal aims. The first aim is “explaining the terrain.” In the immediate following section, we will provide a coarse overview of the most recent data on the representation and experiences of graduate trainees of color in psychology programs, with an emphasis on U.S.-based data. The second part of this section centers on briefly defining key challenges that have been identified as impacting the quality of life of graduate trainees of color. In addition to presenting these definitions, we also, where possible, provide examples of the manifestation of these challenges. Our second aim is devoted to “equipping the toolkit.” In this section, we focus on navigating the terrain of graduate school using culturally relevant relationally centered strategies, as a means of making sense of and maximizing one’s time in graduate school. We see our third aim as “embracing the thriving.” In this section, we consider how to embrace “small wins,” eschew feelings of impostor, and proverbially live your “best life” while in graduate training.

1. Explaining the Terrain

We see the sun. We feel the warmth. We see so much sand and we imagine the ocean. This painful wretched truth can wake us up to recognize that the warmth and sand surrounding our “semi-peaceful” existence does not mean that we are relaxing at the beach, but that we are parched and dehydrated horizontal and face-down in the desert.

We chose to begin this section with this quote from Black psychologist Howard Stevenson (Reference Stevenson and JonesStevenson & Jones, 2015). Stevenson’s words were initially applied to the realities of parents of Black children in predominately White schools, but we find them equally apt here. You have applied to, interviewed at, and been accepted to the program of your dreams. You excitedly find a place to live in your new city and show up to your graduate student orientation full of excitement and promise. We remember this excitement. Moreover, unfortunately, we each remember a moment when the place to which we had arrived began to look and feel a bit different than we had imagined. While this moment looked different for each of us, and will also look different for you, it is nevertheless important to “explain the terrain”: some of the potential realities for BIPOC trainees. Notably, many of these realities are not specific to graduate training in psychology per se, although they are nonetheless relevant. In the subsections that follow we outline the numerical (by the numbers) and narrative (beyond the numbers) experiences of graduate trainees of color in psychology programs.

1.1 Behind the Numbers: Graduate Trainees’ Representation in Psychology Programs

The numerical representation of BIPOC students in graduate training in psychology in the United States is a tale of “low and grow.” This is perhaps not surprising, as it mirrors the field at each stage of the pipeline. For example, the most recent American Community Survey reported that about 84 percent of the active psychology workforce was White, an over-representation given that only 76 percent of the nation is White (APA Center for Workforce Studies, 2018). The American Psychological Association’s (APA) Center for Workforce Studies (CWS) also provides annual information on graduate degrees awarded in the field by race/ethnicity. According to these data, across the 2010s (2010–2019), 72 percent of doctoral degrees were awarded to White trainees, meaning 27 percent of doctoral degrees were awarded to groups defined as trainees of color (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Bi- and multiracial; www.apa.org/workforce). Notably, the most recent available data (2019) suggest a slight improvement, with only 66 percent of degrees being awarded to White trainees. These racial/ethnic data are similar at the master’s level, with 66 percent of degrees awarded to White students from 2010 to 2019 (61 percent in 2019). While it is clear that the number of BIPOC trainees getting doctorates has been low, the data also suggest growth in representation for these groups collectively, as well as for most at the subgroup level. Overall, BIPOC trainees’ awarded doctoral degrees increased by 64 percent over this time frame. Moreover, with the exception of American Indian/Alaska Native trainees, a group that has frequently vacillated year over year, each racial/ethnic minoritized group saw at least a 20 percent increase in degree obtainment.

Continuing down the pipeline, it is important to understand the data for current graduate trainees of color. According to the most recent demographics from the APA’s Graduate Study in Psychology, 63 percent of doctoral and 59 percent of master’s students were White (per academic year 2019). Based on these data, there is a slightly higher number of BIPOC trainees in programs than those who ultimately receive degrees. However, much like the degree data, recent trends suggest that the representation of most racial/ethnic subgroups is growing: Compared to 2014–2015 data, there appear to be increases for every BIPOC trainee group. A final important quantitative marker, particularly as we consider the qualitative, lived experience of BIPOC trainees, concerns attrition. Although these data are not as robustly kept as those on degree earning and enrollment, a December 2017 report on diversity in health service psychology doctoral programs (i.e., clinical, counseling, school) indicated an attrition rate for BIPOC students of 3 percent in 2015 (noted as a decrease of 2 percent from 2012 data; Reference PagePage et al., 2017). The White student attrition was noted to hold steady at 2 percent across these time points (Reference PagePage et al., 2017). In addition to these numerical data, a 2012 study by Proctor and Truscott specifically assessed the attrition experiences of seven Black school psychology trainees. Of note, these students identified a number of contributing factors, including those ideological in nature (e.g., misalignment with career goals), but also, importantly those that were relational (e.g., relatedness with peers and faculty). Notably, with regard to the latter, racial aspects of connection with faculty and peers emerged from the data. These experiences, and others, are elevated in our next section.

1.2 Beyond the Numbers: Qualitative Experiences of Graduate Trainees of Color

One of the racialized elements that trainees in the Reference Proctor and TruscottProctor and Truscott (2012) study alluded to concerns a result of the aforementioned data we presented: the issue of being a numerical minority. Indeed, while the growth of BIPOC trainees in psychology programs is notable, these data are at the national level. In any given program, BIPOC students as a collective may represent a small number of students, with the representation of any one racial/ethnic group even smaller. To illustrate this, the most recent available data from the Graduate Study in Psychology database (academia year 2019) suggested that the median number of Asian graduate students was two, with the median number of Black and Latinx graduate trainees at one, and all other groups too infrequent to provide meaningful measures of central tendency. Feeling like “one of the only” in a given program may lead you as a BIPOC student to wonder if tokenism is at play. Tokenism has been defined as psychological experience among persons from demographic groups that are rare within a setting, in this case, graduate school (Reference Niemann, Bernal, Trimble, Burlew and LeongNiemann, 2003). Of importance for the experience of graduate school for BIPOC trainees, a tokenism experience may leave one: feeling a sense of isolation and loneliness; feeling overly visible or distinctive; feeling like the “poster child” (representativeness) or trapped to engage in a limited manner (role encapsulation); exposed to stereotypes and racism; and being uncertain how to maneuver to interpret certain interpersonal interactions (attributional ambiguity) (Reference Niemann, Bernal, Trimble, Burlew and LeongNiemann, 2003, Reference Niemann2011, Reference Niemann and Naples2016). Moreover, these experiences may lead BIPOC trainees to contribute disproportionately to any diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in their program, department, or even university. Although a more extensive discussion of the effects of tokenism is beyond the purpose of this chapter, we recommend the work of Yolanda Flores Niemann to unpack these experiences.

Underlying a number of the tokenized experiences noted above are the realities of racism and microaggressions that, unfortunately, are present in the institutional and interpersonal dynamics of some graduate departments and/or programs. Briefly, racism is defined as a system propped up by the belief in the superiority of one’s race combined with the power to act out that believed superiority, either at the individual, institutional, or cultural level (Reference JonesJones, 1997). Microaggressions are defined as covert (or at least not overt) insults, assaults, and slights experienced by BIPOC individuals (Reference Sue, Capodilupo, Torino, Bucceri, Holder, Nadal and EsquilinSue et al., 2007). Lest we respond too defensively within our field about the presence of these systems, structures, and in-vivo and vicarious experiences, it is worth noting the first guideline related to the APA’s most recent Guidelines for Race and Ethnicity notes: Psychologists strive to recognize and engage the influence of race and ethnicity in all aspects of professional activities as an ongoing process (APA, 2019, p. 10). Moreover, the APA’s Graduate Student Guide for Ethnic Minority Graduate Students (www.apa.org/apags/resources/ethnic-minority-guide.pdf) devotes an entire section to these two topics, replete with real-life examples. BIPOC trainees have indicated that these racist experiences can emerge in research, clinical, and teaching aspects of their graduate school experience (e.g., Reference Jernigan, Green, Helms, Perez-Gualdron and HenzeJernigan et al., 2010).

Although not unique to BIPOC trainees, a third phenomenon that may impact the graduate training experience is feelings of Imposterism. Initially conceptualized for White women in corporate America (Reference Clance and ImesClance & Imes, 1978), Impostor Phenomenon has been defined as an internalization of unhelpful thoughts related to one’s intellectual competence and has been outlined as perhaps a particularly relevant experience for BIPOC emerging adults (e.g., Reference Cokley, McClain, Enciso and MartinezCokley et al., 2013). Of note, Reference Cokley, McClain, Enciso and MartinezCokley and colleagues (2013) have highlighted that such cognitions may be present among BIPOC individuals as they move through many of the aforementioned experiences in the academic environment, including racial discrimination and several of the sequelae associated with tokenism (e.g., isolation, marginalization, stereotyped exchanges). It manifests as feelings of being “out of place” or seeing our achievements as due to “luck” rather than ability. Germane to this chapter’s title, it is feeling that one neither belongs nor fits in. Our dear colleague Dr. Donte Bernard has an entire chapter in this volume devoted to this topic, which we see as required reading for understanding the psychological outcomes of feelings of impostorism more fully.

In a recent investigation, Reference Bernard, Jones and VolpeBernard, Jones, and Volpe (2020) elucidated that one way in which BIPOC trainees may attempt to cope with feelings of Impostorism is through the use of high-effort coping strategies such as John Henryism Active Coping (JHAC). Named after the Black American folk hero and “steel driving man” who famously bested a drilling machine in building a railroad only to die of exhaustion, JHAC has been defined as “efficacious mental and physical vigor; a strong commitment to hard work; and a single-minded determination to succeed” (Reference Bennett, Merritt, Sollers III, Edwards, Whitfield, Brandon and TuckerBennett et al., 2004, p. 371). Breaking down this definition in lay terms, we would define John Henryism as “going above and beyond” or “doing the most” as a means of navigating a difficult environment that does not seem inviting. Interestingly, the research on JHAC has been mixed: in the short term, some research has suggested that this type of coping can be effective; however, other research has suggested that over time JHAC contributes to negative physical health outcomes and potentially worsened psychological well-being (Reference Bronder, Speight, Witherspoon and ThomasBronder et al., 2014; Reference Volpe, Rahal, Holmes and Zelaya RiveraVolpe et al., 2020). From our perspective, this high-effort coping is harmful over time; another contributor to what is an added burden that can befall many BIPOC trainees. This burden has been referred to as an “emotional tax”: experiences that threaten the health, well-being, and thriving of these trainees (Reference TravisTravis et al., 2016). This tax, we would argue, can make graduate training in psychology an “expensive” proposition, and one that may leave BIPOC trainees counting the costs and benefits.

2. Equipping the (Relational) Toolkit

The combination of the factors we have discussed (i.e., tokenism, racism, microaggressions, impostor syndrome) have the potential to individually and synergistically leave BIPOC trainees feeling a long way from the proverbial day at the beach. At times, in fact, these stressors may resemble the desert experience we highlighted in the previous section, with even occasional wins feeling like a mirage. That said, we find it critical to note that graduate school does not inherently have to be an arid journey. In fact, even if some graduate programs may be more desert than beach for BIPOC trainees, we believe in the ability to find the oasis: a fertile, lush, hydrating place, even in the midst of the desert. In this section, our goal is to identify tangible tools that you can use to navigate the terrain of graduate school, creating a veritable culturally informed relational toolkit. In particular, we focus on the importance of relationships, which we feel is generally congruent with the communalistic cultural orientation of many BIPOC trainees.

2.1 Relationship Building 101: How Can I Get Myself Through Graduate School?

As BIPOC graduate students and early career faculty, we have learned firsthand that relationship building and maintenance is the key to our success and happiness in graduate school. We realize that there are many ways to approach relationships in graduate school, and we include a few that have worked for us along our journeys to the PhD.

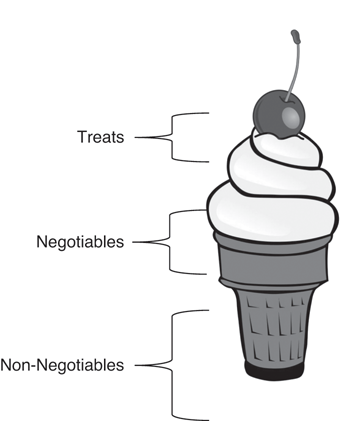

First, determine your non-negotiables. Dr. Hailey tweeted, “Passing along some good advice: When entering grad school, a friend told me to write down the non-negotiable things that sustained my well-being and joy. She said no matter how difficult and hard things get, never negotiate on your list. That list kept me going all six years” (Reference HaileyHailey, 2021). Importantly, she added that this list can be crafted at any point in your journey as a psychologist (i.e., applying to graduate school, during graduate school, post-doctoral fellowship, or in your early or mid-career) and should be frequently assessed, reflected upon, and amended (Reference HaileyHailey, 2021). This advice can be applied to all parts of your life, even outside of school. For example, our therapist colleagues and I (A. Parks) often utilize values exploration and identification activities in our sessions with our own clients, who may be struggling with boundary setting or experiencing distress in their interpersonal relationships or with choosing a career path. There are several ways to approach creating this list. Figure 7.1 outlines one activity that my colleagues and I have found to be successful in our own priority setting in graduate school.

Figure 7.1 Activity for assessing priorities and values.

Figure 7.1 depicts an ice-cream cone. There are three pieces highlighted: the cone, the ice cream, and the cherry. The cone represents your non-negotiables; these are values, activities, categories, or items that you believe to be essential to your success as a person and a graduate student. The ice cream cone represents your negotiables; these are important to your success and happiness, but you are willing to compromise the frequency or intensity in which they exist in your life. Lastly, the cherry (or your favorite topping) represents the activities, items, or categories that you consider to be a treat. They are not required for your daily success and happiness, but when present, they add a little more joy or pleasure to your life. Importantly, these non-negotiables may look very different from what your colleagues or your institution may deem essential. The work in academia does not stop; however, that does not mean you should not take time to slow down or even go at your own pace. Our “embracing the thriving” section will further describe the importance of authenticity and how, through trial and error, to quiet the outside noise and learn to distinguish your own values from the values of others.

Keeping our ice cream cones in mind, relationships are a non-negotiable that will be vital to your success in graduate school as a BIPOC student. As people of color, traditionally, our communities sustain us. Communalism, familismo, and filial piety are similar yet unique values of BIPOC communities that reflect a shared collectivistic nature, harmony, and appreciation of interconnectedness among people (Reference Boykin, Jagers, Ellison and AlburyBoykin et al., 1997; Reference Kim, Atkinson and UmemotoKim et al., 2001; Reference Rivera, Guarnaccia, Mulvaney-Day, Lin, Torres and AlegríaRivera et al., 2008). Extant research has demonstrated that academia and many institutions were not designed for BIPOC students and currently perpetuate oppressive practices and inequities for students (and faculty, staff) of color. Many of us will serve as activists and advocates during our graduate school journey and try to dismantle a number of those oppressive practices and systems. However, we must first focus our energy and time on our humanity. There may be nothing more human than our ability to feel, empathize, and relate with others. Given this, we describe how to nurture your relationships, including the one with self, and to find your people, your family, your community, or your tribe while in graduate school.

2.2 Nourish Your Relationship with Yourself

In order to endure the oft traumatic experience of graduate school as a BIPOC student, you must first advocate for and prioritize your wellness. As a result of having to cope with discrimination, systemic racism, and racism-related stress, BIPOC folks often develop many chronic health conditions and mental health concerns. If your graduate school and/or department does not include health insurance with your funding, and you have the emotional and mental energy, try to advocate with other students and faculty for them to provide it. Unfortunately, this may take several years. In the interim, as much as possible, prioritize your own therapy and other medical appointments. Ironically, graduate students training to be therapists often neglect their own mental health while supporting the mental health of so many others. One hour a week or every other week is vital to your self-preservation as a person of color and should not be compromised. If possible, place these appointments in your schedule before scheduling your other commitments. We must always remind ourselves that we are humans, not machines. Our bodies and minds are to be treasured, nourished, and treated with respect and kindness.

Additionally, nourish your relationship with yourself, by paying yourself first! I (A. Parks) received this advice in my fifth year, and it has slowly improved how I navigate my graduate program. At the beginning of every year, semester, month, and day, pay yourself first. Outline what you need to complete your milestones and goals in the program and your personal life, and work on those items first every morning. In your physical or electronic calendar, schedule a recurring time for your own work and writing, as you would a class or a meeting with your advisor. Days fly by and tasks pile up; often we do not get to our work until very late in the evening, when all of our energy has been depleted. Paying yourself first is one way you can practice radical self-care, and it will guarantee that by the time you graduate, you will be as excited and hopeful as you are now reading this chapter. Our “embracing the thriving” section will expand upon the definition of radical self-care and additional strategies for its prioritization.

2.3 Maintain Relationships that Began Before Graduate School

Community is central to the successful transition to graduate school for BIPOC students. However, too often the focus is placed on the new community you will encounter. It is important to also pour into the people and relationships that contributed to your journey and helped to make you the person you are today. In graduate school, it can become very easy to unintentionally neglect your friends and family. There is no course on how to balance work and our personal relationships while in graduate school. We must fight the urge to succumb to the outside pressure to devote all our time to our graduate work. The more we engage our communal nature, and attempt to reject individualism and its friendly associate, competitiveness, the more we will succeed.

Some suggestions for engaging your community that were present before graduate school include to first communicate, frequently and intensely, with them. Share your wins with them as much as possible! You may begin to unintentionally neglect your friends and family because of the outside pressure to devote all of your time to your school work. Upon reflecting on my time in graduate school, I realized I habitually avoided talking about my school work with my friends and family. I quickly shut down questions about important projects that took up most of my energy on a weekly basis. I began to realize this as a symptom of being disconnected from my purpose. When I began to open up more about my wins and smaller accomplishments with my tribe, my creativity and motivation was reignited. Our close friends and family know us well and can serve as important reminders for our purpose when we begin to use avoidant coping, feel numb, or have thoughts of giving up altogether. They can provide insight into problems and barriers we have experienced with our clients and research ideas and can help us to avoid retreating to the ivory tower. They can also assist us with accountability and can help reinforce us when we notice that our cup is rapidly draining. Disengaging with our tribe can lead to isolation, increased anxiety, burdensomeness, depression, and maybe the most underemphasized, inauthenticity.

Questions you may consider asking yourself to assess your maintenance of “pre-graduate school” relationships: How often do you check in with your loved ones? When you talk to them, do you find yourself asking them more questions about their lives? Do you find yourself avoiding bringing up your graduate school projects? If so, why do you think that may be? Are you worried they won’t understand? Are you worried that they may judge or criticize your progress? Do you find yourself growing disinterested in your own work?

If you answered “no” to most of these, then great job! You seem to be navigating your “pre-graduate school” relationships with harmony and reciprocity. If you answered “yes” to most of these, then we gon’ figure it out together! Our first recommendation would be to begin to reflect on why you may be more disconnected from these relationships. This reflection can also occur in collaboration with your support system. Additionally, it may be helpful to begin weaving your pre-graduate school relationships into your graduate life, in moderation of course, as many find that keeping school and personal life separate serves them best. One way to involve your pre-graduate school folks in your accountability could be to schedule half-hour check-ins, biweekly or monthly, where the time is spent solely on explaining your research to them and receiving feedback on its accessibility. Many BIPOC students feel encouraged by inviting their pre-graduate school folks to their thesis and dissertation proposals and defenses or introducing them to their graduate school mentor and friends. Regardless of what works best for you, the crucial piece is to ensure you are utilizing your community in a way that feels authentic to you, as you cannot make it through graduate school alone.

2.4 Find and Build Relationships Within Your Graduate Community

Finally, we cannot forget the relationships that we will create while on our journey to the PhD. These relationships are diverse and can include other doctoral students in your program, psychology department, your university institution, and even on a national scale (e.g., APAGS, APA division special interest groups, or social media). For example, @blackwomenphds on Twitter features Black women graduate students and PhDs and hosts space for reflection and writing. Ideally, your program or department may have a student-led initiative with an aim for peer mentoring and event curation, which may more easily allow you to meet and get to know your cohort on a personal level. For BIPOC students, finding your people will be essential to thriving in graduate school. These people may or may not always share your racial and ethnic identities, but must share your values and priorities. One way that BIPOC graduate students in our program helped to create community was through hosting parties or kickbacks where the new BIPOC students could meet current students and learn more about the culture of the department. Further, graduate students created a GroupMe, titled Black Girls Matter, to sustain our relationships, discuss our gripes with the program, process microaggressive interactions, or most importantly, to laugh with each other about the latest viral thread on Twitter or plan outings together to focus on our wellness. Below, we have included additional concrete tips for sustaining your relationships with your graduate school tribe. These can also be applied to all relationships you develop along the way.

Tips for Sustaining Relationships

Engaging each other for accountability and support. Start a weekly writing group with other BIPOC students where you can prioritize your work and provide feedback to each other throughout the writing process. Expand upon this weekly time by considering attending or creating writing retreats with each other for a weekend or two throughout the semester.

◦ Working on fellowship, scholarship, and internship applications together.

◦ Taking trips out of the city and developing boundaries about school. For example, only discussing school for 15 minutes and ensuring the remainder of the trip is a school-free zone.

Using our strengths to help each other. For example, if you are very disciplined when it comes to sleep, but you have a friend who struggles with insomnia, consider developing an accountability plan wherein you text the friend every night an hour before bed and remind them to wind down and check in on them in the morning.

Sharing cultural celebrations and traditions with each other. Family dinners, book clubs, watch parties, and group chats, or celebrating cultural holidays together.

Celebrating and promoting each other. Attending proposals and defenses, nominating each other for appropriate scholarships or awards, and sharing research and fellowship opportunities with each other. Finding a weekly time to celebrate all wins with each other.

Outside of the people you meet in graduate school, who are also pursuing a graduate degree, you will also find community in the people of the city or town of your graduate institution. Recalling our activity in Figure 7.1, where you elect to spend your time, and subsequently build your relationships, will be dependent on your values. For example, you may hold existing spiritual or religious identities you want to feed, and you may find home and support in local churches, temples, synagogues, or other religious organizations. The people you meet at these places will undoubtedly connect you with additional supports and organizations or areas of the city that may further align or expand upon your interests. Additionally, for BIPOC students, engaging with cultural organizations may help you to feel at home, away from home, and nourish your cultural values even further. One way to find cultural organizations and events will be to follow local social media accounts and connect with university student-led cultural organizations or university centers. These organizations or centers will be more knowledgeable about how to get involved in your racial/ethnic community, outside of or within the institution. At the end of your graduate journey, when you walk across the stage and your degree is conferred, these relationships will be what you remember, what will persist, and what will matter.

2.5 A Brief Word on Jegnaship

As we close out our section on the toolkit, we would be remiss if we did not briefly discuss a relational approach to mentorship that we find is critical. We did not provide an exhaustive discussion of mentorship, advising, and sponsorship because we feel that the aforementioned APAGS Resource Guide provides a fantastic overview of these vital relationships. Nevertheless, there is a form of advisement rooted in Afrocentric perspectives which we feel has benefited each of us, and is worthy of excavation: jegnaship. Black psychologist Reference Nobles and JonesWade Nobles (2002) describes the jegna as one who has shown determination and courage in protecting their peoples, land, and culture; produced an exceptionally high quality of work; and dedicated themselves to the protection, defense, nurturance, and development of future generations. The Association of Black Psychologists has long recognized the importance of jegnaship as a transformative experience that goes beyond what is typically considered in a mentor/mentee relationship. It invokes community, family, village, many of the elements we have described before. Although jegnaship is considered a pillar of Black psychology and thus highly applicable to Black trainees in psychology, we would encourage you all to find your version of a Jegna, someone who will pour into you holistically, providing the nourishment needed to traverse the sands of graduate school.

3. Embrace the Thriving

In our first two sections, we have made the case for understanding what the landscape may be for BIPOC graduate trainees in psychology and have provided some tools for such a journey, centered on the critical role of meaningful self- and other-relationships. However, despite our extended desert/beach metaphor, and the realities that graduate school can be an exhausting experience for BIPOC students, we reject that graduate school for BIPOC students should merely be a time of surviving (mere existence). Rather, we proclaim and affirm that your experience can be a time of thriving (growth and flourishing). This is the focus of our final section.

3.1 Rise and Thrive: Using Healing Justice to Thrive and Resist Oppression

Attention BIPOC trainees: we absolutely can live our best lives during graduate school and enjoy the ample experiences and lessons along the way. We can and we deserve to flourish and enjoy the unique opportunities to grow personally and professionally and to develop meaningful and lasting connections with colleagues, mentors, and friends. More importantly, we each can contribute to changing the racially oppressive culture that remains rampant within psychology graduate programs. Our thriving and resistance can pave the way for more supportive and equitable experiences for BIPOC graduate students to come. One critical strategy towards promoting our thriving and resistance against oppression in academic settings is adopting an ethic and practice of healing justice. Reference PylesPyles (2018) defines healing justice as “a framework that identifies how we can holistically respond to and intervene on generational trauma and violence and bring collective practices that can impact and transform the consequences of oppression on our bodies, hearts and minds” (pp. xviii–xix). The principle of healing justice offers a pathway toward addressing and mitigating the traumas and stressors uniquely imposed upon racially and/or ethnically marginalized communities in higher education. Prioritizing your healing and wellness not only contributes to individual and collective emotional, cognitive, and physical preservation, but also serves as a form of resistance against the racially oppressive impositions of “grind culture,” inauthenticity, and perfectionism that have historically plagued BIPOC graduate students. Healing justice can provide us with an opportunity to partake in the facilitation of systemic change. When you care for yourself, you care for others, especially those with whom you share common identities. Similarly, when you care for yourself, you challenge racist ideals that render BIPOC students undeserving of grace, compassion, rest, and pleasure. Furthermore, we believe that we can maintain a culture of healing justice in graduate school by (1) embracing mediocrity; (2) showing up as our authentic selves; and (3) celebrating your achievements and promoting yourself.

3.2 Embracing Mediocrity

“You have to work twice as hard to get half as far” – sound familiar? I (K. Allen), like most BIPOC students, grew up hearing and living by this expression. I believed that I needed to be excellent at every step of my academic journey to reach the spaces and positions I desired. I thought that achieving consistent perfection would give me a sense of vindication and liberation in white-dominated academic settings; however, graduate school taught me otherwise. By my third year, I had begun to seriously question whether I had enough energy to make it through the remainder of my doctoral program. My relentless pursuit of excellence and perfection had propelled me onto a fast track to burnout. I realized that I would likely not make it through to the finish line if I were to continue to overextend myself. This prompted my interrogation of my and other BIPOC students’ tendencies to “do the most” for every single assignment, task, and role. Oftentimes, BIPOC graduate students feel pressured to demonstrate effort, intellect, and creativity that exceed well beyond that of White students, just to be considered for “equal” opportunities and recognition. To be clear, this pressure is not derived from mere perception. It is true that White people are rewarded more opportunities and accolades than racially marginalized people for the same or lesser effort, and they receive less penalization for mistakes and shortcomings. This is just one of many ways institutional racism manifests in academia. However, succumbing to this expectation often leads BIPOC to overwork to the point of near exhaustion. Furthermore, many of us find ourselves spiraling into a perpetual struggle with perfectionism.

Graduate school will be one of the most challenging and demanding life experiences that you will likely encounter. Psychology graduate programs, in particular, will stretch you to inconceivable lengths. Your schedule will be jam-packed with research projects, assistantship tasks, clinical work, preliminary exams, dissertation writing, class attendance and assignments, and a host of other responsibilities. In addition, as a BIPOC student, you will likely expend much time, as well as emotional and mental energy, processing and battling incidences of racial discrimination within your department and beyond. Given the demands on your time, energy, and effort, it is inevitable that you will have to aim for completion, rather than perfection, at times. It is impossible to read every article and book chapter, submit an “A”-quality paper each time, attend every club meeting, take on every available leadership position, and so forth, while sustaining sound physical and emotional wellness. Your work will need to be mediocre, at times. This is not just okay, but necessary for self-preservation. Embracing mediocrity can be especially difficult for BIPOC students to accept and practice, as we have long used perfectionism and overexertion to cope with discrimination and bias. However, these coping mechanisms are not sustainable, especially within psychology graduate programs. To thrive and resist academic racism, you must grant yourself the grace and compassion to be imperfect. Reclaim the energy you might otherwise expend in pursuit of perfection and invest that into yourself. Not every task requires your best effort and thought. Observe and learn what tasks truly require your best work, and limit the time and energy you expend on the rest. Your weekly reflection papers for courses do not need to contain your most profound questions and commentary. You need not thoroughly read every assigned book chapter. Furthermore, we have discovered that more often than not, our “mediocre” performance was actually far better than we give ourselves credit. Our grades did not change when we committed ourselves to unlearning the habit of overworking, but our overall happiness and well-being most certainly did.

When we embrace mediocrity, we reject the racist ideologies that have denigrated the intellectual capabilities and value of BIPOC in the field of psychology and elsewhere. We transcend, rather than accept, the White supremacist falsehood that the value of our work, skills, and effort is lessened by our racial identities. Remember, you do not have to prove your worthiness of existing in a psychology graduate school program. You are already excellent and deserving as you are. Be mediocre when you need to. Reinvest your energy into yourself and your community. This simple yet profound act of resistance and radical self-compassion can contribute to genuine, meaningful transformation of psychology training programs.

3.3 Authenticity

Self-altering is an age-old coping mechanism that many BIPOC have adopted to navigate racially hostile terrain within collegiate settings. We may “put our heads down and get through,” a strategy that is sometimes even advised by well-meaning BIPOC faculty for whom this approach was adaptive during graduate training. Thus, each day, we negotiate which parts of ourselves we will leave at home and which parts we will bring with us into our academic spaces. We may silence our voices, suppress our valid and real emotional responses to racism, alter our hair and clothing, and even change our voices and dialect to meet the Eurocentric standards that are deemed acceptable in the academy. Truthfully, suppressing your authentic self will not protect you from experiencing racism, but it will almost certainly drain your spirit. Indeed, behaving in manners incongruent with your values, beliefs, and genuine interests can negatively impact your overall well-being (Reference Harter, Leary and TangneyHarter, 2012). On the other hand, embracing authenticity can reduce your risk of burnout, contingent self-esteem, and psychological distress.

Challenge whitewashed standards of “professionalism” that have historically been used to denigrate, exclude, and silence BIPOC students and faculty. Showing up authentically will not only support our overall well-being, but in doing so, we can shift the racist tradition of professionalism in graduate school. The following are some ways in which you can persist as your authentic self in graduate programs:

Speak in your native language(s) and dialect. Do not feel pressured to “code switch.”

Dress in a way that is congruent with your personal and cultural identity, especially during presentations and conferences.

Wear your hair in its natural state.

Integrate your genuine values and customs into your research and clinical practice.

3.4 Self-Promoting and Celebrating

Many BIPOC trainees come from collectivist cultures. As we stated earlier, many of these cultures emphasize the community over the individual. Although we all have a healthy appreciation for this perspective, we nevertheless want to highlight the importance of effective self-promotion. At a minimum, this includes having and distributing business cards. However, beyond this traditional tool, we also advocate for creating blogsites, websites, and social media profiles as relevant as a means of networking and sharing your research and accomplishments. If your program or department has some sort of newsletter or blast for recognizing graduate student awards, consider letting the proper administrative personnel know. If this feels too misaligned with your values, this may be a great ask of your mentors or jegnas, or even your fellow colleagues.

Closely related to the notion of self-promotion is celebrating. Perhaps also eschewed by some cultures represented among BIPOC trainees, we feel that it is impossible to thrive in graduate school without frequent celebration and joy. Researchers have found that some of the greatest minds have been able to endure because they took stock to identify “small wins,” and then, upon recognizing that a small win, some progress toward a more protracted goal had arrived, they took time to celebrate (Reference Amabile and KramerAmabile & Kramer, 2011). In the same way that we reject the lies of hyper-productivity and inauthenticity, we similarly rail against notions that the only moments in graduate school worth celebrating are “major” milestones. Yes, please celebrate passing your thesis, comprehensive or qualifying examinations, and dissertations. But also: finally figured out that stats syntax? Celebrate! Submitted that fellowship application? Celebrate! Got through year one of your program as whole as possible? Celebrate! Got an e-mail from a student sharing how much your help as a Teaching Assistant helped them figure out their major? Celebrate! I (S. Jones) personally encourage you to craft a celebration playlist that you have queued up for just such an auspicious occasion. Perhaps it’s Cake By the Ocean or Vamos a La Playa or Soak Up the Sun or Beach Chair (are you catching our beach theme here?). Celebrating sustains us; the joy it produces is the nectar of BIPOC thriving in graduate school.

4. Conclusion

As we close out this chapter, we wish to draw attention back to the post-colon portion of our title. This supplication is a play on the words of Brene Brown. In her book, The Gifts of Imperfection, Reference BrownBrown (2010) distinguishes “fitting in” versus “belonging” in the following light: whereas fitting in is described as “becoming who you need to be to be accepted,” belonging simply requires us to “be who we are.” This is our hope for every BIPOC trainee at every program in the country. As you understand the terrain that is your school and unit, take up core strategies for traversing, and embrace a spirit of thriving rather than simply surviving, we trust that it will lead you to a feeling that you belong at your program as your authentic self, without needing to conform, transform, or assimilate. Indeed, whether the sand between your toes is beach or desert, you belong at your graduate school program.

Nevertheless, in the immortal words of Levar Burton on Reading Rainbow “don’t just take [our] word for it.” We invite you to read the following list of affirmations provided by trainees of color (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1 Affirmations from current trainees of color in psychology programs

| Change is the only consistent thing in life. Be yourself and you are enough. You have your own timeline and journey; no need to compare yourself to others. Your time will come. It’s a marathon, not a sprint. Take care of yourself first before others. You’re not going to do everything and that’s okay. |

| Finding a community that can help you thrive is essential. |

| I advise you to take deep breaths when you feel frustrated or discouraged and recite that internal phrase that motivates you or has motivated you to get to that program. I always think of the people that have inspired and supported me. Celebrate every little victory because that makes the slow process of a PhD feel like there has been progression. Finally, remember that self-care helps get you through your program because that is what re-energizes you and growing in self-care along with your PhD knowledge makes you a more whole person (in my opinion). |

| Just because others do not understand your ideas or consistently criticize your reasoning for studying a particular topic, does not mean that your work is not important. Sometimes, just showing up is enough! Your presence is enough! |

| Please know that rest is important. If you are lacking this as a graduate student, you won’t magically get it as a faculty member or professional. |

| Protect your magic. I would pass that on to students of color generally. You are a hot commodity in these spaces. Don’t let everyone take your energy. |

| Remember that you deserve to be where you are. A lot of people feel like impostor syndrome can be endearing but that mindset can be detrimental to developing the confidence and competence you need to be successful in these settings. |

| Some of your greatest sources of support in the difficult times will be your family, friends, and colleagues that affirm the challenges associated with the journey you are embarking on. Lean on this support and hold fast to it when things get overwhelming. In the moments where you get lost in the difficulty these are the individuals that remind you of who you are and give you the support and encouragement to press on. |

| Take care of yourself physically and mentally. Say no and stick with it. You don’t need to deal with the academia trauma. |

| You are much smarter and more capable than you give yourself credit for! I promise, you wrote enough (for that assignment)! |

| You are human. You are more than a student. There will always be work. Please rest. Please call your family and friends. Your future self says thank you. |

| You are worthy. Those who have come before you will guide you, just as you will be there to guide those who come after you. Your voice matters, even in spaces that are invalidating or seemingly inhospitable. There’s a community out there for everyone – find one that values you for YOU! |