This article presents the results of our recent research into the Sertorian War (82–72 BCE) as part of a series of projects aimed at locating, analyzing, and contextualizing the archaeological evidence linked to different periods of conflict in northeastern Hispania during the Republican period.Footnote 1 Since 2006, we have systematically surveyed many archaeological sites in the lower Ebro basin area and their different military occupations related to the Second Punic War, as well as the indigenous rebellions from the beginning of the 2nd c. BCE and the Sertorian War. While the first two conflicts have been discussed in previous publications, the results pertaining to the Sertorian War appear here.Footnote 2 After summarizing the historical knowledge of the Sertorian War gleaned from the written sources and the most recent archaeological data from Hispania, we discuss the methodology applied during our archaeological research. Then we present the newly studied archaeological sites and their finds, before contextualizing our research within the broader archaeological corpus from northeastern Hispania and linking most of the archaeological evidence to a specific historical campaign.

Historical context

The Sertorian War was a secondary theater of the First Roman Civil War, involving a confrontation in Hispania between the populares, under the command of Quintus Sertorius, and the optimates, who sent several armies to oppose him.Footnote 3 It was a particularly bloody war. In the words that Sallust placed in the mouth of Pompey in a letter addressed to the Senate, “Hither Spain, so far as it is not in the possession of the enemy, either we or Sertorius have devastated to the point of ruin, except for the coast towns, so that it is actually an expense and a burden to us.”Footnote 4 Unlike the Second Punic War, which was mainly fought in open-field combat between large armies (at Cissa, Hibera, Baecula, Ilipa, etc.), the confrontations between Sertorius and the different commanders of the optimates were characterized above all by assaults and sieges of towns that habitually ended with them being burned to the ground or destroyed, and with severe punishments meted out to the populations.Footnote 5 The remarkable mobility of the Sertorian forces was complemented by attempts to control the territory, with the aim of sustaining the troops. This strategy also had a major impact on the optimates' forces. The distance and lack of support from the Senate obliged them to depend on local supplies. Each of Sertorius's successes wore down their resources. It is no surprise therefore that Pompey bemoaned the cost to his forces of holding the coastal towns, one of the few points via which he was able to receive provisions, as well as the important logistical role played by Gallia Transalpina, as we will discuss below.

Quite a few historical sources tell us about the conflict, although they also present certain problems, such as their discontinuity in time, a lack of geographical precision, and the existence of different historiographical trends.Footnote 6 To these we add the great influence of the interpretive tradition of Adolf Schulten, one of the researchers who has most influenced the analysis of the written sources referring to Hispania, sometimes erroneously.Footnote 7 Fortunately, archaeological developments, such as those presented here, can help nuance or even reinterpret aspects of the conflict.Footnote 8

Quintus Sertorius, who belonged to Marius's and Cinna's faction, was sent to Hispania as proconsul in 83 BCE to establish a base for the populares. However, Sulla sent an army under the command of G. Annius Luscus that managed to drive him out of Hispania in 82 BCE.Footnote 9 After a brief African expedition, Sertorius returned two years later and was able to defeat various optimate armies in the south of the Iberian Peninsula.Footnote 10 In 79 BCE, Sulla again sent two legions to Hispania Ulterior, now under the command of the proconsul Q. Caecilius Metellus Pius. However, Metellus remained practically isolated beyond the River Annas (the present-day Guadiana) and could do nothing to avoid the continual defeats of the optimates.Footnote 11 In that same year, Sertorius's legate, L. Hirtuleius, vanquished M. Domitius Calvinus, proconsul of Hispania Citerior, in the Tajo valley; and in 78 BCE, in the Ebro valley, he defeated L. Manlius, proconsul of Gallia Transalpina, who had come to the aid of Metellus.Footnote 12

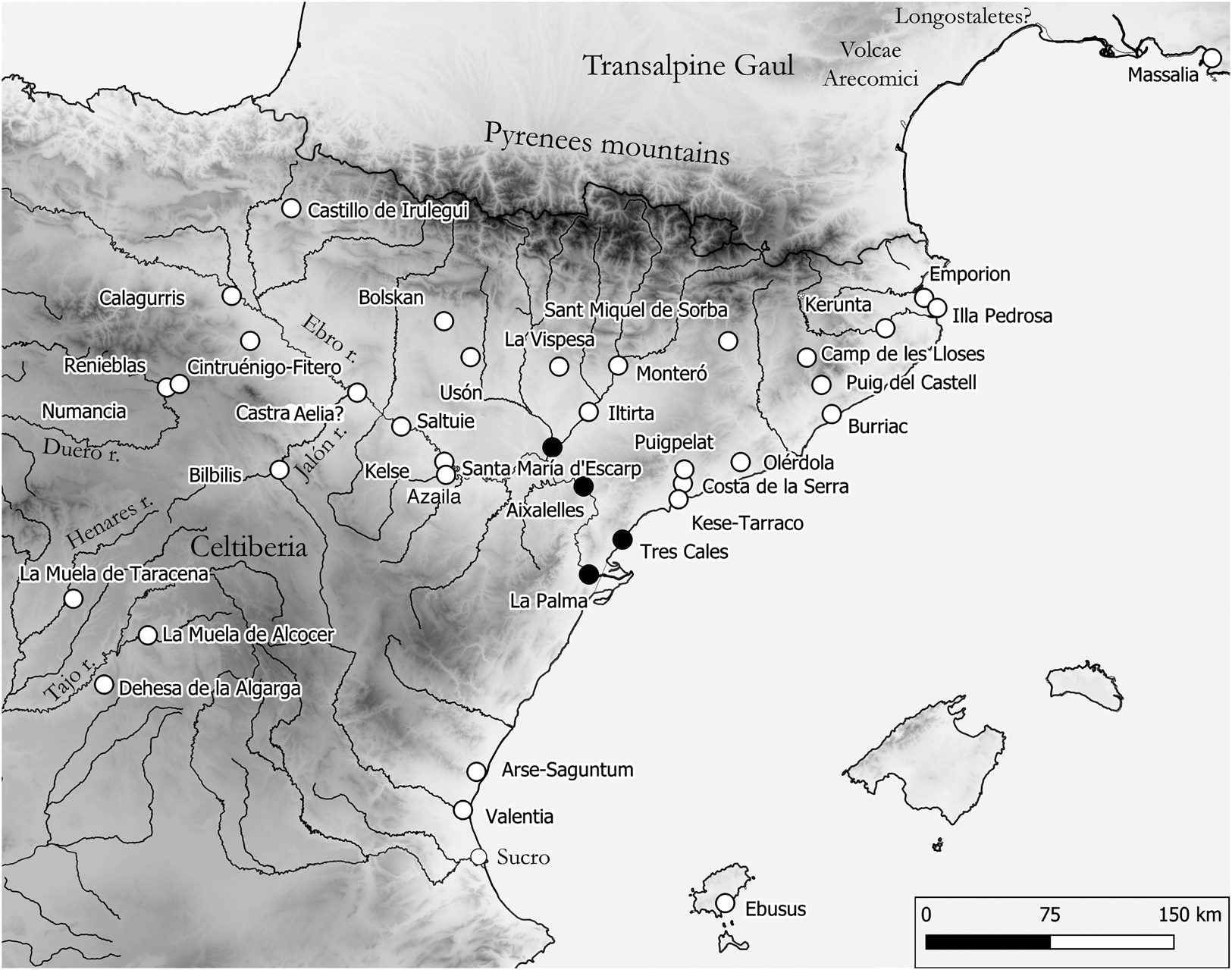

At that time Sertorius was at the height of his power in Hispania. In 77 BCE he ordered Hirtuleius to detain Metellus in the southeast while he marched toward the Ebro valley, following the natural corridor formed by the rivers Henares and Jalón through Celtiberia (Fig. 1).Footnote 13 He conquered the towns of Caraca and Contrebia and reached the River Ebro, where he set up camp at Castra Aelia.Footnote 14 Between 77 and 76 BCE, he deployed an intensive military and diplomatic campaign to control the main towns in the center and northeast of the Iberian Peninsula.Footnote 15 He also received reinforcements with the arrival of M. Perperna Vento and 20,000 legionaries.

Fig. 1. Map of the northeastern Iberian Peninsula, showing the locations of the place names cited in the text. (Map by the authors.)

Faced with the magnitude of the defeats and difficulties in Hispania, in 77 BCE the Roman Senate sent a large army under the command of Pompey that opened a way through Gallia Transalpina and crossed the Pyrenees in early 76 BCE. In the first confrontation in that same year, Sertorius defeated Pompey near the town of Lauro.Footnote 16 In the following year, however, the optimates managed to break the Sertorian military deployment.Footnote 17 In the south Metellus defeated Hirtuleius, while Pompey was able to cross the River Ebro and defeat Perperna near Valentia.Footnote 18 Sertorius went to Perperna's aid and attempted to counteract these setbacks with battles at Sucro and Mogontian.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, from that time on, the Mediterranean coast and the northeast were to a large extent controlled by the senatorial troops, who subsequently focused their attention on the Ebro and Duero river valleys, the last redoubts of Sertorius's followers.Footnote 20 By 74 BCE, the Sertorian faction's ability to react was diminished and they were unable to face the two optimate armies simultaneously. Metellus took important towns such as Bilbilis and Segobriga, while Pompey was defeated by Sertorius at Pallantia and forced to retreat from Calagurris.Footnote 21 These combats weakened the Sertorians, who were condemned to failure after the betrayal and assassination of Sertorius himself in the year 72 BCE. Perperna was finally defeated by Pompey, thus sealing the fate of the populares faction in Hispania.Footnote 22 The last Sertorian redoubts were conquered that year.

The contribution of archaeological surveys

From a methodological point of view, our project can be framed within the field of conflict archaeology, which involves above all the study of temporary military sites (marching camps, battlefields, and siegeworks).Footnote 23 The importance of conflict archaeology for the Roman period is confirmed by the study of battlefields such as the Teutoburg Forest (Kalkriese), Baecula (Santo Tomé), and Harzhorn (Northeim), as well as the marching camps at Lautagne (Valence), and siegeworks such as those at Alesia and Burnswark Hill.Footnote 24 These examples show how much information can be obtained with just surface surveys when a high volume of artifacts is found, even if they are not in their primary position. The distribution and concentration of weaponry, military equipment, coinage, and pottery is sufficient to reconstruct the different stages of these historical episodes (troop movements, firing of weapons, close combat, and subsequent looting). At the same time, the intensive analysis of aerial photography and remote sensing (especially LIDAR) in unplowed areas has uncovered tens of new temporary camps (some of them not yet confirmed by archaeological excavation) from the Gallic Wars and the Cantabrian Wars, or from different expeditions beyond the German limes or Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine Wall.Footnote 25 In these cases, even with scarce archaeological data, the density of sites and the regular distances between them allow a detailed reconstruction of entire campaigns.

The research presented here combines systematic visual surveys, metal detector surveys, aerial photography, and geophysical surveys. All the archaeological traces detected were checked afterward with sondages, and the resulting data were finally integrated with a geographic information system.Footnote 26 Specific methods will be noted in detail in the description of each site, but the starting point was usually vertical and oblique aerial photographs, using first balloons and later drones. The aim was to detect possible differences in vegetation growth or changes in the coloration of the terrain that could suggest the presence of structures in the subsoil, mainly ditches and pits, some of the most common and best-documented defensive structures in the camps. LIDAR images were also studied for the same purpose.

This was followed by fieldwalking using a previously configured surveying grid with sampling units of 10 × 30 m. We consider such relatively large surface areas optimal for the recovery of finds at Roman military settlements because these are usually characterized by a low density of pottery but a very high dispersion index. The surveying was intensive, with a separation of 1 m between the fieldwalkers. Subsequently, geophysical surveys were carried out in places with a greater potential for locating structures in the subsoil (as suggested by aerial photography or the density of surface pottery finds), including electrical resistivity tomography, magnetic surveys, and ground-penetrating radar. In general, the results were insignificant, although small test pits were dug (ca. 2 × 2 m) at places where anomalies were detected. None of these sondages provided positive results, but they were useful for verifying the stratigraphy of the settlement and confirming that in most cases we were dealing with contexts that had been much altered by modern farming.

In the absence of results, where possible we opted for the controlled removal of the topsoil in layers of less than 10 cm using a motor grader, allowing us to survey large areas quickly, safely, and efficiently. Thanks to this lowering of the surface level we accessed deeper layers not so affected by modern rubbish and clandestine metal detectorists, and were able to recover a large number of metallic finds, the vast majority (as we will see) clearly related to Roman-period military occupations. All these metallic objects were georeferenced by GPS and subsequently loaded into a geographic information system to manage aspects such as the distribution of the different objects by their chronology, type, functionality, etc.

The landscape of the lower Ebro basin has been greatly transformed in modern times by extensive agriculture, the construction of infrastructure (roads, railways), and recent conflicts such as the Spanish Civil War. This explains why neither the aerial photography nor the excavations have documented any archaeological structures.Footnote 27 Additionally, the continuous occupation in some areas makes it difficult to assign some of the artifacts (weaponry and military equipment) to a particular episode or conflict. Nevertheless, the number of datable artifacts collected is so large (especially coins, but also pottery and inscribed slingshots) that it is possible to reconstruct the diachronic evolution of the sites. Therefore, even without structural remains or archaeological contexts, we are able to determine occupation and abandonment phases and even to define the approximate area of the different settlements with a high degree of certainty.

The archaeological surveys carried out as part of the research project have yielded a very particular type of evidence resulting from the concentration of troops involved in a campaign. This type of military activity normally does not leave any built structures but does generate a large number of artifacts on the surface.Footnote 28 Their systematic recovery and meticulous georeferencing minimize, to a certain extent, one of the main challenges of this type of archaeological evidence: the lack of stratigraphic contexts. A well-georeferenced archaeological record allows us to characterize an archaeological site and define its chronology with a precision that could appear implausible based on the surface remains.

Nevertheless, we have to take into account that a superposition of occupation phases is documented at most of the studied archaeological sites, leading to a margin of uncertainty when dating or attributing certain artifacts to a specific military conflict. This is particularly significant in the case of finds without a well-defined chronology through seriation, including throwing weapons, arrowheads, and slingshot projectiles, as well as items of clothing and footwear such as buttons or hobnails.

New archaeological evidence

To date we have identified four sites with archaeological evidence related to the presence of troops during the Sertorian War: Les Aixalelles (Ascó), La Palma (L'Aldea), Les Tres Cales (L'Ametlla de Mar), and Santa Maria d'Escarp (Massalcoreig), the first three in the province of Tarragona and the fourth in the province of Lleida.

Les Aixalelles (Ascó, Tarragona)

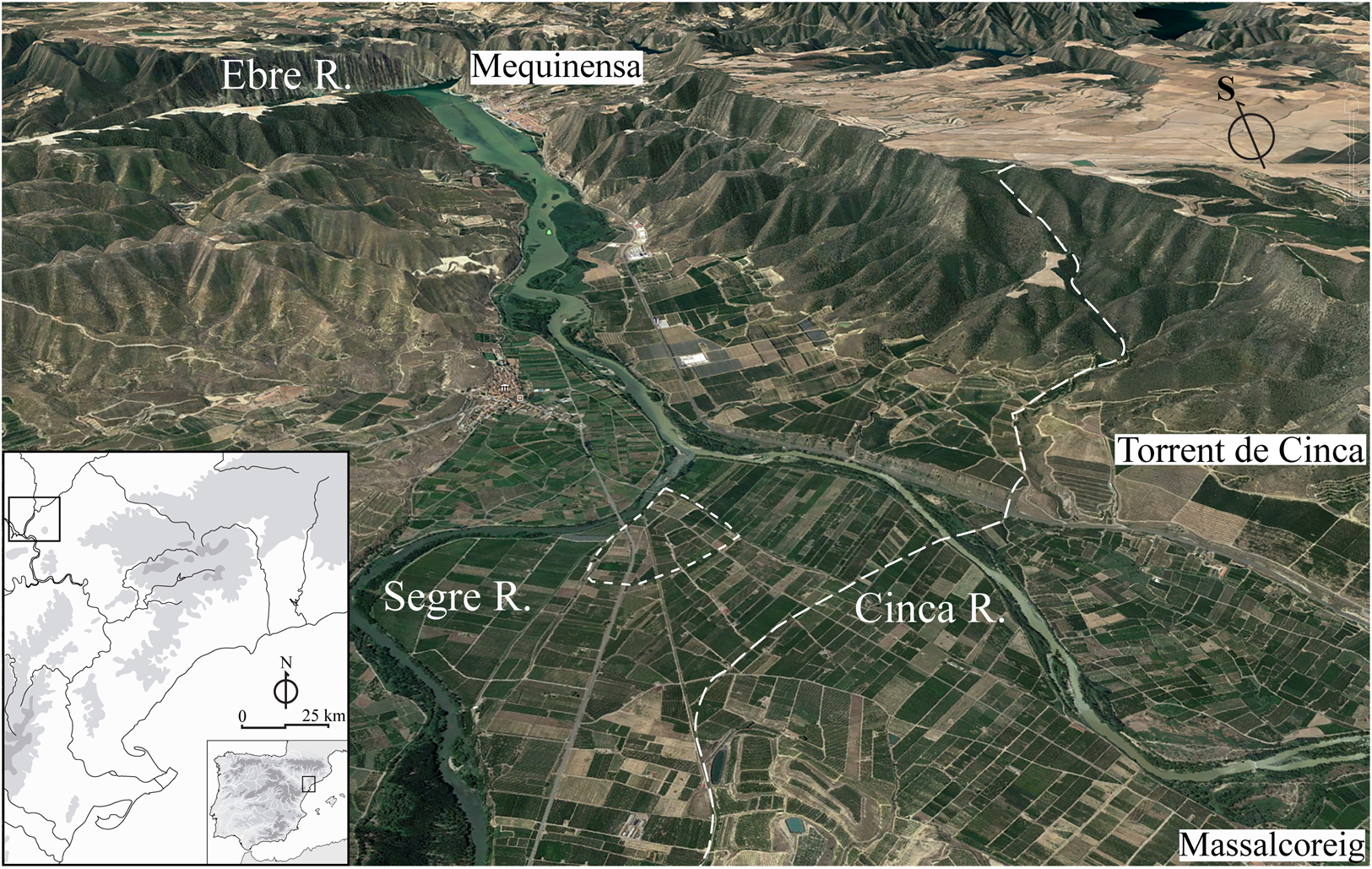

The archaeological site, investigated in 2012–13 and 2016, is located on the left bank of the Ebro, near a large meander in the river, where its course widens and slows down to offer a natural ford. It covers a completely flat area of some 70 ha that is protected to the north by a series of small elevations (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. View from the south of the River Ebro meanders in the Les Aixalelles area and the situation of the archaeological site. (Photo: Google Earth, earth.google.com/web/.)

Following aerial photography, a total area of 4.15 ha was intensively surveyed. In total, 1,497 pottery sherds were found, the vast majority Roman tableware and amphorae from the 1st and 2nd c. CE. Only three fragments of Campanian ware from the 2nd–1st c. BCE were found. Extensive surveying with metal detectors was carried out over an area of some 15 ha, at times facilitated by the plowing for crop rotation, which led to an exponential increase in the number of metal finds. The finds were concentrated in the plots closest to the River Ebro, but no specific distribution pattern could be identified. Geophysical surveying with electrical resistivity tomography and ground-penetrating radar did not provide any significant results and no building remains were found. However, the finds clearly define three periods of occupation: the passage of Carthaginian troops during the Second Punic War,Footnote 29 a military occupation during the Sertorian War, and, finally, the installation of a farming settlement in the Imperial Roman period.

The fieldwalking survey results allowed us to rule out stable occupation prior to the Roman agricultural exploitation, which began around the early 1st c. CE, as practically no Iberian pottery or 3rd- to 1st-c. BCE Italic imports were found. No tableware or transportation and storage pottery were found, as would have been expected in a campaign or marching camp. Therefore, the site appears to have been a temporary occupation, probably linked to controlling crossing points across the Ebro.

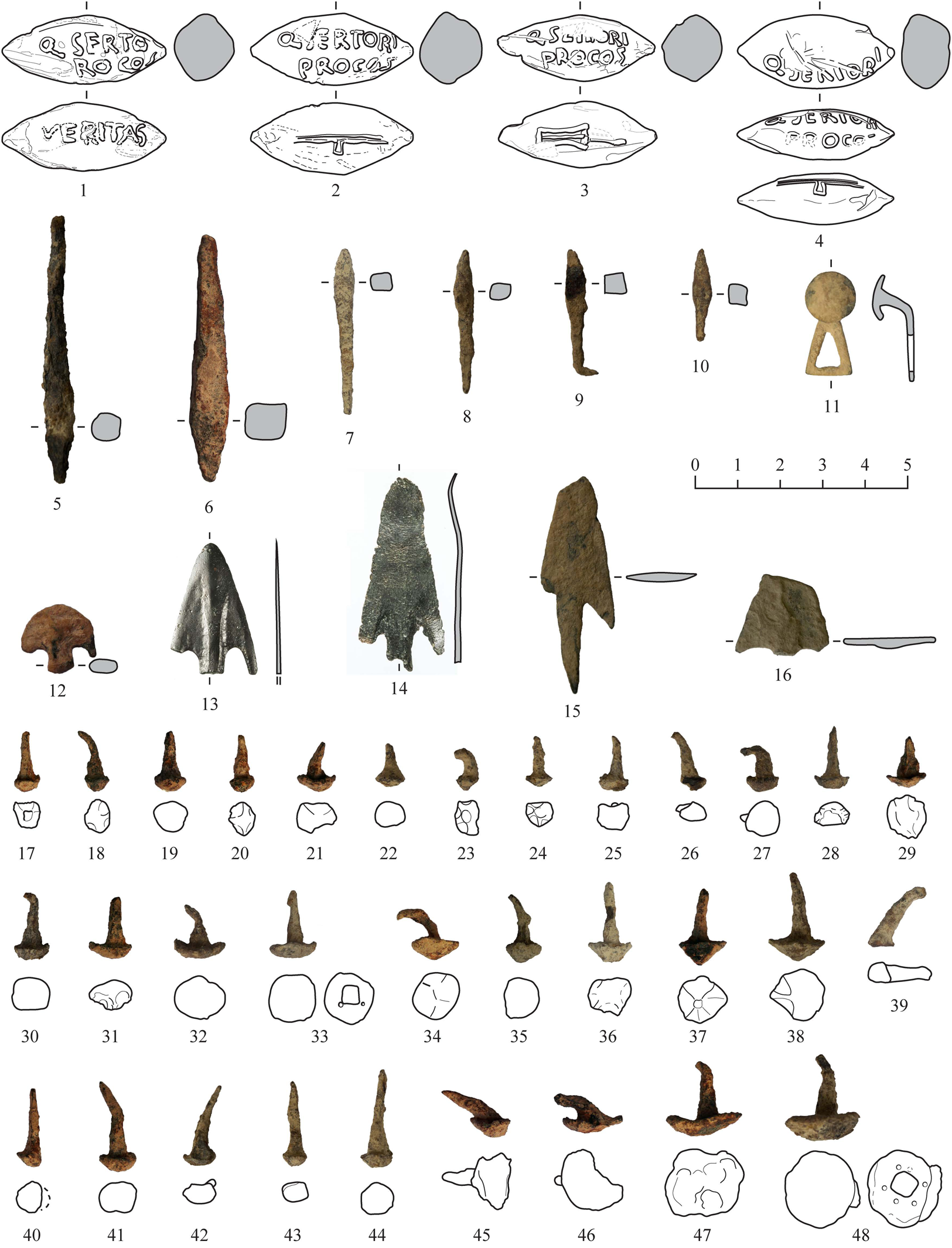

Regarding material related to the Sertorian military settlement, we can highlight the scattered finds of 14 lead sling bullets, 4 of them inscribed. Two bear the inscription Q.SERTORI / PROCOS on one side and the fasces symbol on the other, one the inscriptions Q.SERTO / PROCOS and VERITAS, and the last Q.SERTORI / PROCOS and the gubernaculum symbol (Fig. 3.1–4).

Fig. 3. Finds from the Les Aixalelles archaeological site: 1–4. Sertorian glandes inscriptae; 5–10. Bi-pyramidal iron arrowheads; 11. Button with triangular loop; 12–16. Local-tradition bronze arrowheads; 17–48. Clavi caligarii. (Photos and drawings by the authors.)

Other types of weaponry include six bi-pyramidal iron arrowheads (commonly known as darts) (Fig. 3.5–10). These have been interpreted as simply crafted arrowheads and are also found in other Republican-period conflict contexts, such as Baecula, Renieblas, the siege camps around Numantia, and La Cabeza del Cid.Footnote 30 In addition, we documented five bronze arrowheads belonging to a local tradition: two barbed and tanged Type B1, two Type C1 with a simple tongue, and an undetermined one, possibly belonging to Group C as defined by Ruiz Zapatero (Fig. 3.12–16).Footnote 31 Further military equipment is represented by 46 iron hobnails or clavi caligarii (Fig. 3.17–48), plus two more made of bronze, and a triangular button-and-loop fastener (Fig. 3.11).

Finally, the loss of 21 coins can be dated to the Sertorian conflict.Footnote 32 Three are Roman, specifically a denarius of M. Papirius Carbo dated 121 BCE (RRC 276/1), a quinarius of T. Cloulius from 98 BCE (RRC 332/1c), and a denarius of Caius Annius Luscus and Lucius Fabius Hispaniensis from 82–81 BCE (RRC 366/1) (Fig. 4.1–2).Footnote 33 However, the vast majority of the coins are indigenous asses: five from Kese, five from Iltirta, two from Bolskan, two from Kelse, one from Saltuie, and two that have yet to be determined (Fig. 4.3–5). There is also a Greek bronze coin from Leucas (Akarnania) dated after 167 BCE.

Fig. 4. Coin finds from the Les Aixalelles archaeological site: 1. Gens Papiria denarius (RRC 276/1); 2. C. Annius Luscus and L. Fabius Hispaniensis lined denarius (RRC 366/1a); 3. Coin from Bolskan (Villaronga and Benages Reference Villaronga and Benages2011, 1419); 4. Coin from Kelse (Villaronga and Benages Reference Villaronga and Benages2011, 1482); 5. Coin from Kese (Villaronga and Benages Reference Villaronga and Benages2011, 1218). Scale 1:1. (Photos by the authors.)

La Palma (L'Aldea, Tarragona)

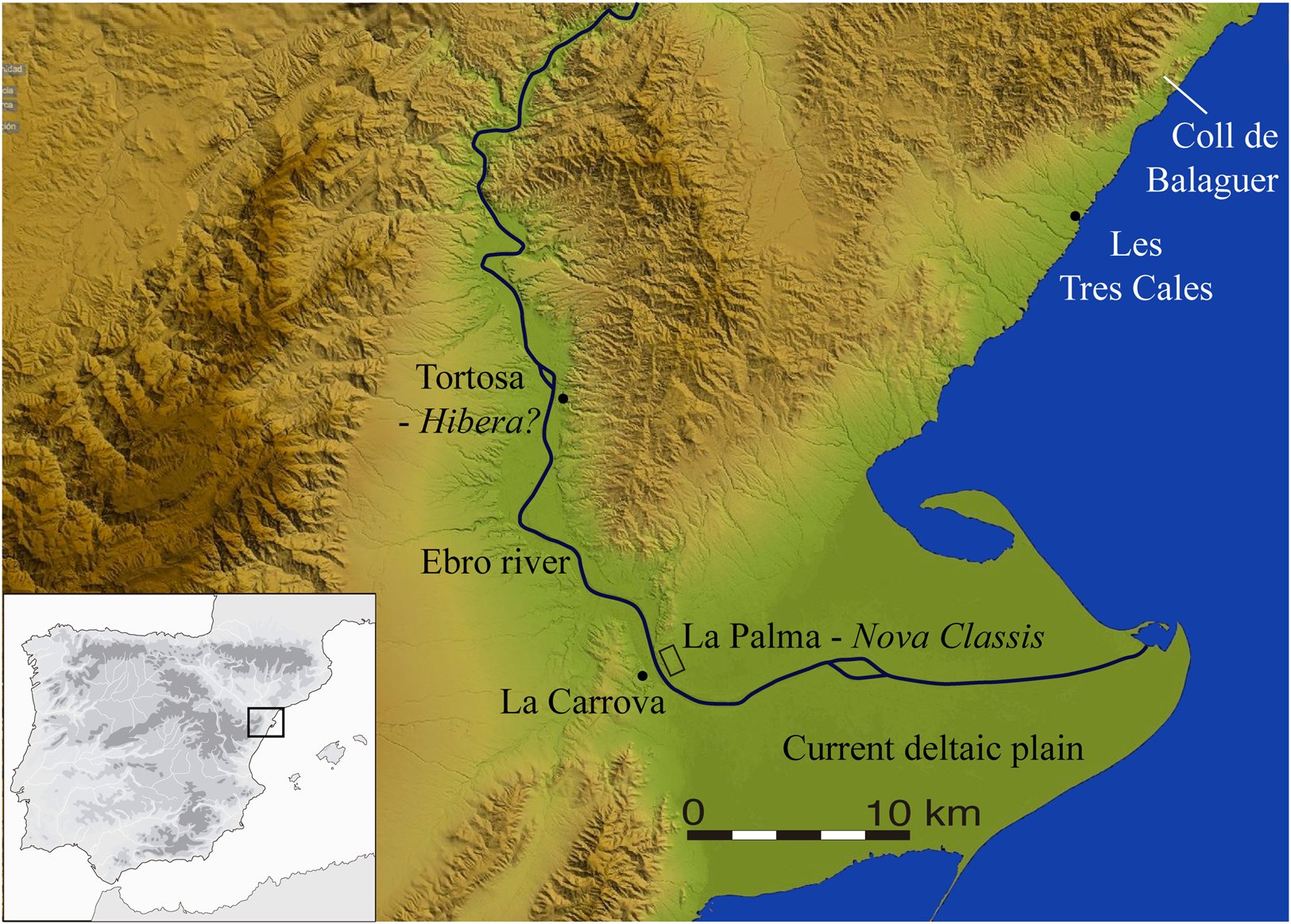

The La Palma archaeological site occupies one of the last fluvial terraces on the left bank of the Ebro before the river flows into the Mediterranean (Fig. 5). It covers an easily defensible area of some 30 ha, with a water supply and areas suitable for docking ships. It had an excellent strategic position, as all the overland communication routes that followed the coast, including the ancient Via Heraklea,Footnote 34 had to pass near the site, and it also controlled access to the River Ebro on this navigable stretch.

Fig. 5. The area around the mouth of the River Ebro, showing the locations of the La Palma and Les Tres Cales archaeological sites that controlled the coastal routes and the River Ebro crossing. (Map by the authors.)

The archaeological site was systematically surveyed between 2006 and 2011. La Palma has undergone enormous anthropic alteration. It is crossed by a railway line and a highway, and a motocross circuit and a new housing estate have been built on the site. It has also suffered from continuous looting for more than 20 years, as well as the effects of decades of farming. Therefore, our survey was only able to focus on an area of a little under 7 ha. Aerial photographs were taken during all the campaigns but it was not possible to detect any anomalies. In 2006, a first fieldwalking survey combining two methods was carried out over 5 ha. The first part covered 4 ha with a 10 × 30 m grid, and the second 1 ha, in which each ceramic sherd was located using a total station. Both methods resulted in a very low pottery density – around 125 sherds per hectare – of which 70% were Greco-Italic amphorae from the late 3rd c. BCE, 25% were Iberian ware, and 5% were indeterminate.Footnote 35

In the area with the highest pottery density, a geophysical survey (magnetic and ground-penetrating radar) was carried out on 1.5 ha, but with sparse results. Nevertheless, a series of test pits was dug that served to confirm the absence of stratigraphy, with only a thin layer of soil, often less than 50 cm, covering the natural rock. Finally, during the last campaigns it was decided to carry out a series of controlled removals of topsoil using a motor grader over 5 ha of land. No built structures were identified, but the systematic use of metal detectors made it possible to recover a large number of objects from different periods, the positions of which were recorded using GPS. The results indicate that this was the site of Scipio's Nova Classis camp during the Second Punic War.Footnote 36 However, some of the finds, a small but significant assemblage, can be related to the presence of Roman military contingents in the early 1st c. BCE.

Some of the surface archaeological finds could be from either the late 3rd c. BCE or the early 1st c. BCE. Thus, for example, judging by their shape and weight, we inferred that the majority of the lead sling bullets were from the Second Punic War, although some of them could have been from a subsequent period.Footnote 37 The same could be said of the arrowheads of indigenous tradition that were used over a long period, or the clavi caligarii from the soles of the Roman footwear. Likewise, some of the La Tène I-type fibulae could be later. Therefore, we will only describe the finds that can be securely dated to the 1st c. BCE. Among the most obvious are an appliqué from the handle of a Piatra Neamț-type jug and another Ornavasso-Ruvo-type appliqué (Fig. 6.24–25); two horizontal simpula handles (Fig. 6.22–23), one of the 1A type and another of the 1B type;Footnote 38 a bowl; and a fragment from the foot of a bronze winged Mercury.

Fig. 6. Archaeological finds from La Palma: 1. Socketed pilum head with pointed shaft prolongation; 2. Socketed pyramidal iron arrowhead; 3–8. Local-tradition bronze arrowheads; 9–20. Clavi caligarii; 21. Button with triangular loop; 22–24. Horizontal simpula handles; 24–25. Ornavasso-Ruvo- and Piatra Neamț-type jug handles; 26. C. Reni denarius (RRC 231/1); 27. M. Herenni denarius (RRC 308/1a); 28. Bolskan denarius (Villaronga and Benages Reference Villaronga and Benages2011, 1413); 29. As (RRC 159/3); 30. Massalia bronze (PBM 45-2/Mau.110); 31. Bronze divisor from Longostaletes (Villaronga and Benages Reference Villaronga and Benages2011, 2677?); 32. Volcae Arecomici bronze (VLC-2677). Coins on a scale of 1:1. (Photos and drawings by the authors.)

However, it is the numismatic evidence that can provide us with greater chronological precision.Footnote 39 An assemblage of relatively early Roman bronze coins was identified, specifically an anonymous uncia (RRC 56/7) dating to after 211 BCE that is so worn that we believe it was discarded many years after the Second Punic War. Three asses date between 206 and 158 BCE (RRC 113/2, 159/3, and 194/1) and a triens from 157–156 BCE (RRC 197–198B/3). The other Roman bronze coins are difficult to classify due to their poor condition after having been in use and circulation for a long time. However, precisely for that reason, they are firm candidates for having been used in the early 1st c. BCE, as the Roman bronze coins linked to Scipio's camp in the late 3rd c. BCE are exceptionally well preserved. In addition, two denarii date to the late 2nd c. BCE, one of C. Renius (RRC 231/1) from 138 BCE and another of M. Herennius (RRC 308/1) from 108–107 BCE.

Iberian Peninsula mints are represented by Iberian coins from Untikesken, Arse, and two indeterminate asses (one of them, judging by the style of the male head, could be from Arse or Saiti; the other is very worn), together with two denarii from Bolskan. Undoubtedly, some of the 14 bronze coins from Ebusus could also have been discarded during that time, although their prolonged period of emission and deplorable state of preservation make this difficult to confirm. Also attested are a bronze coin from Longostaletes in the Narbonne area, four small bronze pieces from Massalia, and two Volcae Arecomici coins, all dated, with certain difficulties, to between the 2nd c. and middle of the 1st c. BCE (Fig. 6.26–32).Footnote 40

All this evidence allows us to hypothesize the presence of military contingents between 82 and 72 BCE, whether Sertorian or Pompeiian, in this strategic zone at the mouth of the Ebro. In fact, some years ago, on the opposite bank of the river, in the La Carrova area, an early 1st-c. tomb was excavated.Footnote 41 It contained Iberian pottery, a Montefortino-type helmet, another handle appliqué from a Piatra Neamț-type jug, small bells (tintinnabula), and other finds characteristic of Sertorian conflict contexts.Footnote 42

Les Tres Cales (L'Ametlla de Mar, Tarragona)

The Les Tres Cales area is 7 km to the south of the Coll de Balaguer, a pass through the mountain spurs that reach down to the sea and which in ancient times was difficult to negotiate (see Fig. 5). A stretch of the Via Augusta was found in its environs, as well as one of the earliest milestones (mid-2nd-c. BCE) found to date on the Iberian Peninsula.Footnote 43 The archaeological site covers some 25 ha of a maritime terrace situated approximately 10 masl. It is near the Sant Jordi gully, the mouth of which creates a natural port, one of the few in the area that is protected from the hazardous east winds. In the gully bed there is a spring with fresh water, a very scarce resource in this dry, rocky territory.

All these characteristics explain the strategic importance of the site, which, until recent times, was an obligatory stop on the road between Tarraco and the mouth of the River Ebro. In fact, in addition to the military presence during the Republican period, the site was occupied by military contingents in subsequent periods: for example, during the Julio-Claudian era by troops probably involved in the intensive road network reform and improvement program.Footnote 44 The site continued to be occupied by a mansio or mutatio until the Late Imperial periodFootnote 45 and even beyond, to judge by the find of a hoard of gold and silver Visigothic coins from the second half of the 6th c. CE.Footnote 46 The first archaeological investigations attested to the military nature of the settlement based on a high percentage of Republican-period amphorae from the Italian peninsula.Footnote 47 Successive surveys motivated by the imminent urban development of the area reached the same conclusion. They detected a higher percentage of amphora sherds (87%) than Italic black gloss ware (13%), while the multiple test trenches dug confirmed that no building remains had been preserved.

As part of our project we undertook two intensive survey campaigns in 2014 and 2015. Owing to the nature of the terrain, aerial photography did not provide any results, and geophysical surveys were ruled out. The archaeological investigation took place in two different areas. The first, covering 5 ha, was a development area where the roads and pavements had already been laid out and several houses were due to be built. Visual surveys had already been conducted and the stratigraphy had been checked with test trenches. Therefore, given the steep, rocky terrain, we focused on surveying with metal detectors and on recovering diagnostic pottery (rims, bases, handles, etc.), recording their exact location with GPS. The second area covered 0.7 ha and was a ravine with a lot of vegetation. As this area had long been inaccessible, the survey of the surface layer yielded significant results. In both areas we proceeded to remove layers of 5–10 cm until we reached the bedrock. In the ravine area, the work was halted when a more compacted stratigraphic level appeared with a higher concentration of rocks and large fragments of tegulae, undoubtedly the remains of a Roman-period building. A total of 2,181 metal and pottery objects were recovered during the surveys, the vast majority dated between the 3rd c. BCE and the 6th c. CE.

Finds dated to the Republican period constitute the second most numerous assemblage on the site, surpassed only by Early Imperial Roman finds. Among the pottery shapes, Dressel 1A and 1B and Lamboglia 2 amphorae predominate. There is also a small percentage of black gloss tableware and Italic cookware, difficult to classify as the finds are very weathered.

In terms of metal objects, of particular note are the 58 lead sling bullets, 2 with Sertorian inscriptions (Fig. 7.1–2). One of the projectiles bears the inscription Q.SERTORI / PROCOS on one side and on the other the single letter V situated to the left of the field, which we propose corresponds to VERITAS, as is common in other Sertorian contexts. Another sling bullet has the inscription …TORI on the far right, while the other face only preserves the end of a legend, …DES, which could stand for FIDES, another common inscription.

Fig. 7. Finds from Les Tres Cales (II) archaeological site: 1–2. Sertorian glandes inscriptae; 3–4. D-shaped belt buckles; 5–6. La Tène III or late-type fibulae; 7–24. Clavi caligarii; 25–28. Buttons with triangular loop; 29. Glans inscripta from Santa María d'Escarp; 30. Massalia hemiobol (Mau.103); 31. Denarius from Bolskan (Villaronga and Benages Reference Villaronga and Benages2011, 1417); 32. As (RRC 201/2); 33. Unit from Kese (Villaronga and Benages Reference Villaronga and Benages2011, 1187); 34. Gens Cloulia quinarius (RRC 332/1); 35. P. Crepusius denarius (RRC 361-1C); 36. Q. Caecilius Metellus denarius (RRC 374/2). Coins on a scale of 1:1. (Photos and drawings by the authors.)

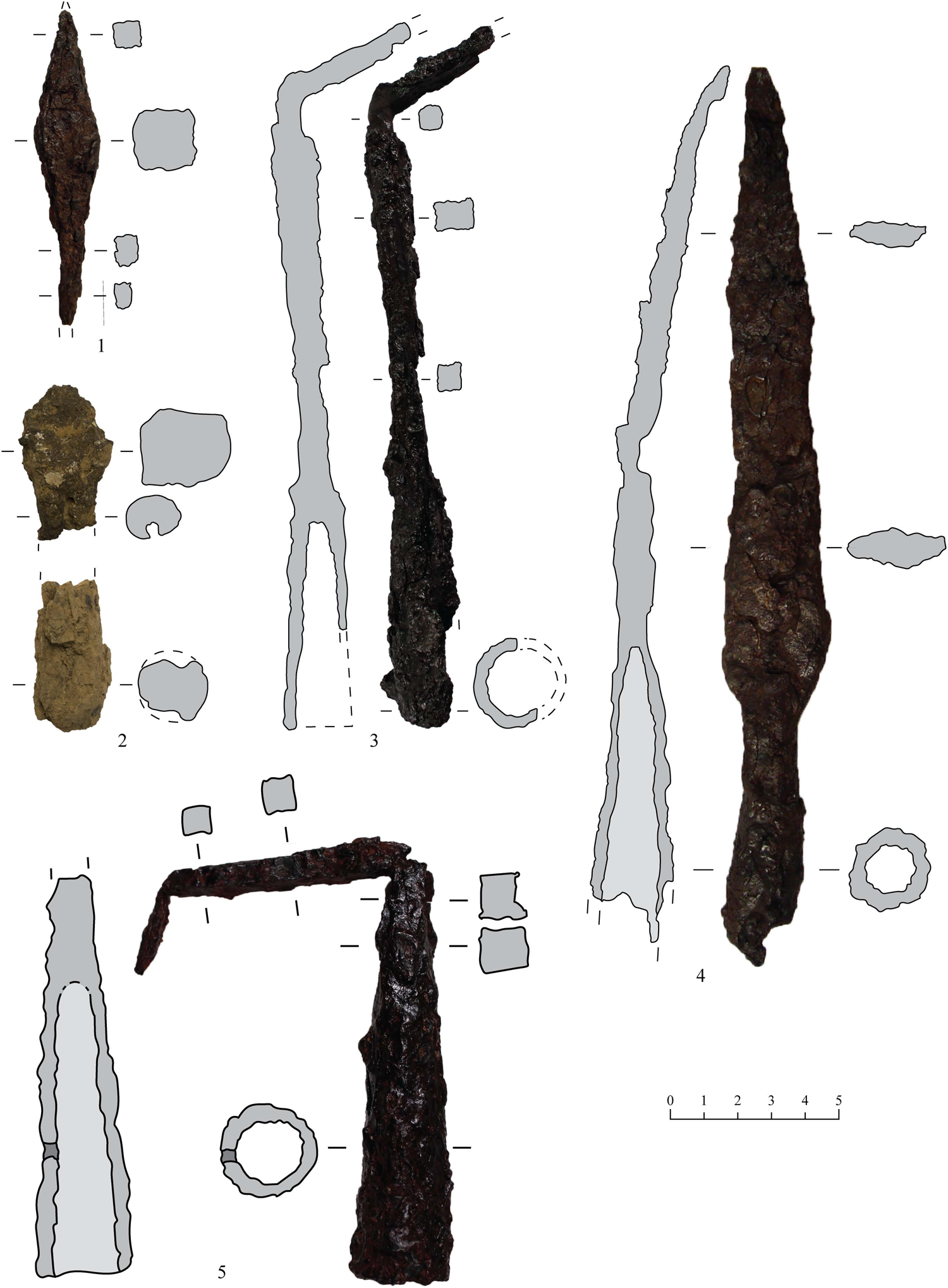

Documented weaponry includes a shaft with socket and the pyramidal head of a pilum, perhaps from the same weapon (Fig. 8.1 and 3). This type of head is not documented until the last third of the 2nd c. BCE and is particularly common from the 1st c. BCE at archaeological sites such as Valentia and Cáceres el Viejo.Footnote 48 There is also a socketed javelin head with a tip made by prolonging the point of the shaft (Fig. 8.5). Its shape and length of ca. 15.5 cm are similar to examples from other Roman military contexts such as Baecula, Es Soumâa, and Šmihel.Footnote 49 A Quesada Vc-type spear head has a very extensive chronology that does not allow a precise dating of the phase to which it would have belonged (Fig. 8.4).Footnote 50 Three tanged bronze arrowheads include one of the C1 type and two of the C3 type.Footnote 51 Finally, there is a possible catapult bolt or pilum catapultarium similar to those found at Emporion and Šmihel (Fig. 8.2).Footnote 52

Fig. 8. Weaponry recovered at Les Tres Cales (I) archaeological site: 1. Pyramidal pilum head; 2. Fragments of a pyramidal head and haft socket belonging to a catapult bolt; 3. Pilum with haft socket and square-section shaft; 4. Spear head with a flat rhomboidal-section blade and shaft socket; 5. Javelin head with pointed shaft prolongation and shaft socket. (Photos and drawings by the authors.)

We documented 26 fibula fragments (bows and pins), only 2 of which could belong to the Sertorian context: an Erice Nauheim type 7.1, very common during the Sertorian War, although unusually this one is made of iron; and a rare example that is difficult to classify (Fig. 7.5–6).Footnote 53 The latter has an unpierced foot and an appendix and can be compared to Erice type 13, although with a laminar bow decorated with linear molding that resembles the Alesia type.Footnote 54 It also has a spring with six coils and an unusual cord connecting system that is only documented in the unguiform fibulae of the 11.b variant.Footnote 55 All these characteristics make a 1st-c. BCE dating the most plausible.

Two D-shaped belt buckles (Fig. 7.3–4), three Type V button-and-loop fasteners, and a fragment of a triangular loop (Fig. 7.25–28) could be linked to a gladius suspension system.Footnote 56 While the Type V had a considerable longevity and was even manufactured into the Imperial period, it would fit into a Sertorian context, with parallels known from Cáceres el Viejo, Camp de les Lloses, and Sant Miquel de Sorba.Footnote 57 Sandal hobnails (clavi caligarii) included 17 of iron and one of bronze (Fig. 7.7–24), and were generally small (around 6–7 mm in diameter) with conical heads, making them similar to examples from the Julio-Claudian era.Footnote 58 Only two have somewhat larger-diameter heads (13 mm), which could correspond either to a different type or to an earlier chronology, linkable to a Sertorian War context. The flat circular heads of another 10 bronze hobnails suggest they were used not on shoes but on other leather items or furniture.

Finally, the study of the 463 coins found at Les Tres Cales has allowed us to define the three most important phases of occupation in terms of the number of coins: the Sertorian War, the Julio-Claudian era, and the Constantinian dynasty.Footnote 59 A total of 133 of the coins were minted between the Second Punic War and the first quarter of the 1st c. BCE. We do not doubt that the settlement was occupied during the war against the Carthaginians, but many of the coins from that period and also from the first half of the 2nd c. BCE are very worn, suggesting that the majority were deposited many years later. Most Republican-period coins are Iberian bronzes from the 2nd or early 1st c. BCE, mainly from Kese (46) and Arse-Saguntum (9), although some were minted in the south of the Iberian Peninsula (4) or the Ebro valley (7) (Fig. 7.31 and 33). Early Roman bronze coins included eight extremely worn asses from 211–206 BCE and five asses (Fig. 7.32), two quadrants, a triens, and four semis from the 2nd c. BCE, also very worn.Footnote 60 In contrast, most of the silver coins date to the late 2nd c. or the first years of the 1st c. BCE: a C. Renius denarius from 138 BCE (RRC 231/1), a Q. Minucius Rufus denarius from 122 BCE (RRC 277/1), a L. Appuleius Saturninus denarius from 104 BCE (RRC 317/3a), a T. Cloulius quinarius from 98 BCE (RRC 332/1c) (Fig. 7.34), a Q. Titius denarius from 90 BCE (RRC 341/2), three M. Porcius Cato quinarii from 89 BCE (343/2b), an anonymous denarius from 86 BCE (RRC 350 A/2), two denarii from 82 BCE, one a L. Manlius Torquatus (RRC 367/3) and the other a P. Crepusius (RRC 361/1c) (Fig. 7.35), and finally three denarii from 81 BCE, two Q. Caecilius Metellus (RRC 374/2) (Fig. 7.36) and one L. Cornelius Sulla (RRC 375/2). Finally, issues from southern Gaul date to the late 2nd c. and the first half of the 1st c. BCE, including eight small bronze coins from Massalia (Fig. 7.30), an imitation DIKOI drachma, and two Gallic potins.

Santa Maria d'Escarp (Massalcoreig, Lleida)

The archaeological site is located on river terraces that constitute a triangular-shaped spur of some 15 ha between the confluence of the Segre and Cinca rivers, 8 km to the north of where the Segre flows into the Ebro at Mequinensa (Fig. 9). To date we have only been able to carry out one survey campaign (in 2016), which yielded sherds of Iberian and Campanian A (Lamb. 7) and B (Lamb. 1) pottery. Coins included two semis from Castulo, two asses from Kelse, an as from Iltirta, and a semis from Ebusus. More significantly, two lead projectiles were found, one with the inscription Q.SERTORI / PROCOS on one side and PIETAS on the other (Fig. 7.29).

Fig. 9. View from the north of the confluence of the Segre and Cinca rivers. (Photo: Google Earth, earth.google.com/web/.)

The site is clearly strategically placed to control communications, not only because it overlooks the confluence of the two rivers, but also because it is situated at an intersection of ancient and modern roads between the plain of Lleida, the gorge of the River Ebro, and the high plateau of Aragon. It is therefore no coincidence that two milestones from the second half of the 2nd c. BCE have been located in its vicinity, at Massalcoreig (Lleida) and Torrent de Cinca (Huesca).Footnote 61 They were erected on the orders of Q. Fabius Labeo, proconsul between 118 and 114 BCE, and attest to the fact that this was the route of a road between the coast and the Ebro valley.

Analysis: archaeological indications of military activity during the Sertorian War

The documentation from the settlements described above allows us to integrate the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula into the general framework of the Sertorian War, and adds to recent research carried out in other territories, such as the coastal zones of Contestania, Carpetania, and the Vascon and Vaccaean territories.Footnote 62 Taken together, this new archaeological research paints a picture of a complex, large-scale conflict that affected the whole of the Iberian Peninsula.Footnote 63

The four archaeological sites discussed here share important characteristics. First, they are located in strategic places on important communications routes, as is shown by their proximity to Roman milestones and roads or fords across the River Ebro. Second, they occupy large areas of several dozen hectares, with low and widely dispersed finds densities. Likewise, despite geophysical surveys and archaeological sondages, in none of them have we been able to document built structures. All four sites were reoccupied in various periods for an identical military purpose (from the Second Punic War to the Battle of the Ebro in 1938), obviously because of their high strategic value. Finally, they all yielded relatively homogeneous assemblages of weapons, coins, and Roman Republican military equipment. Therefore, we believe that these were short-term military establishments: campaign camps or small garrisons stationed there for a specific purpose and time. The surface archaeological finds date these enclaves to the period of the Sertorian War.

The numismatic assemblages are defined by the majority presence of indigenous bronze coins from the 2nd and early 1st c. BCE, a lower number of 2nd-c. BCE Roman Republican bronze coins with a long period of use, and Roman denarii from immediately prior to the conflict. The presence of indigenous coins is directly related to their proximity to the issuing mint. In other words, their distribution was mainly local or regional, and they cannot be attributed to one side of the conflict or another, even if some researchers propose that the optimate faction received more resources from the metropolis, while the populares used more indigenous coinage.Footnote 64 Recent studies link Iberian coin issues with the payment of indigenous auxiliary cavalry contingents who served in the Roman army in the late 2nd c. BCE.Footnote 65 In any case, their presence is constant in the military contexts of the time and they were without doubt used by both Roman and indigenous troops as fractional currency. Likewise, the prolonged use of Roman Republican bronze coins is a characteristic feature of the monetary circulation of the time and is widely attested at military camps such as Cáceres el Viejo, or in violently destroyed towns such as La Caridad.Footnote 66 Of particular note is the scarcity of Roman denarii minted after the year 80 BCE in hoards clearly linked to this conflict, such as that deposited in Valentia before its destruction, or in Emporion.Footnote 67 Two explanations can be put forward. First, these might be lost or misplaced coins and not hoards, meaning that both their loss and their subsequent find would have been fortuitous. Second, the denarii might have been mainly brought in by the armies sent from Rome, reaching northeastern Iberia with the troops of A. Luscus in 82 BCE and later with those of Perperna and Pompey in 77/76 BCE.

It is important to highlight the presence of coins from Gallia Transalpina, the majority of them small bronze examples from Massalia, but also coins from Longostaletes and the Volcae Arecomici, and Gallic potins.Footnote 68 These coins are rarely found on the Iberian Peninsula and are often linked to the presence of optimate troops, as in the case of the 56 small Massalia bronze coins found in Alcohuajate (Cuenca).Footnote 69 The presence of these coins in coastal settlements such as Les Tres Cales and La Palma could be interpreted simply as a consequence of maritime trade. However, following the historical account of the conflict and taking into consideration the military presence suggested by other archaeological indicators, we link them to the flow of supplies that arrived from north of the Pyrenees in a military context. The find of the two Massaliot hemioboloi among the coins belonging to the attackers of the Sertorian town of Azaila can be understood in the same context.Footnote 70

Metal tableware assemblages specific to the Sertorian context in a broad sense (125–75 BCE) often include Piatra Neamț- and Ornavasso-Ruvo-type jugs, Gallarate-type cups, the horizontal handles of Types 1A, 1B, and 1C simpula, and the vertical handles of Types 2, 3, and 4.Footnote 71 Many of these pieces have been documented in key contexts, such as the Cáceres el Viejo camp, the Spargi shipwreck dated to around 100 BCE, and the destruction levels of Delos from 69 BCE.Footnote 72 In our study area, the most numerous ensemble was found at Camp de les Lloses.Footnote 73 However, the archaeological site that has yielded the largest number of wholly preserved examples is Libisosa.Footnote 74

The presence of La Tène III or late-type fibulae is of note, especially the simplest varieties of the Nauheim type (Erice 7.1.a and 7.1.b) that are frequently found in military contexts linked to the Sertorian conflict. Of particular note are the finds of the Cáceres el Viejo camp, the Camp de les Lloses vicus, and Libisosa itself.Footnote 75 Other documented forms include: Erice Type 6, also known as developed Nauheim with D section, at Camp de les Lloses and Sant Miquel de Sorba;Footnote 76 and Erice Type 13 with a raised foot, a rectangular transversal element, and a terminal adornment, found at Les Tres Cales and Cáceres el Viejo.

Other elements common in early 1st-c. BCE Roman Republican military contexts include caliga hobnails, fasteners, buckles, spurs, tintinnabula, rings, and surgical instruments, such as, for example, those documented in the small Sertorian forts on the Alicante coast, Cáceres el Viejo, and Camp de les Lloses.Footnote 77

The presence of weapons is another key element for identifying a Roman military occupation. However, if we exclude some pieces with a large typological variation, such as the gladii hispanienses that begin to appear in the 1st c. BCE, the shield umbos, or the helmets, other weapons are not chronologically diagnostic. For example, while the first examples of pila with pyramidal heads, narrower tangs, and longer shafts date to the 1st c. BCE, these were in use until the Julio-Claudian era and coexisted with socketed pila and simpler heads with a pointed shaft. Arrowheads were scarce, particularly compared with the preceding and subsequent conflict periods, and appear to have been a mixture of iron and bronze pieces of varying types. Thus, we find both local-tradition bronze heads with flat tang (Monteró, Camp de les Lloses) and Italic-tradition examples of iron with a simple elongated or trilobate head and a spiked tang (Numantia), or even pyramidal heads with sockets that can only be differentiated from the pila catapultaria by their size.

We have argued elsewhere that at least two metrological models for lead sling bullets would have coexisted in Hispania in the Republican period, one based on the Attic mina and the other on the Roman libra.Footnote 78 The first would have been the most widely used during the 3rd and 2nd c. BCE and had two calibers: the most common being 35 gm, equivalent to 8 drachmai, and another twice the weight, 70 gm or 16 drachmai. The second appeared during the Sertorian War and eventually completely replaced the previous model during the Second Roman Civil War, also with at least two different calibers: one of 55 gm, equivalent to 2 unciae or 1 sextans, and another of around 41 gm, equivalent to one-eighth of a libra or 1 sescunx. Interestingly, the projectiles from Les Aixalelles and Les Tres Cales, regardless of whether or not they bear the Sertorius inscription, are based on the earlier Attic mina model. However, other projectiles from northeastern Iberia without inscriptions but dated to the time of this conflict follow the Roman model, as do projectiles attributed to the Sertorian War elsewhere. Those from the Ebro valley weigh around 40 gm (i.e., based on the sescunx) and those from Encinasola (Huelva) 55 gm, matching a sextans.Footnote 79 The same is true of the set of projectiles bearing the inscription Q.MET (Quintus Caecilius Metelus) from El Castillo de Miramontes (Azuaga).Footnote 80 Out of almost 2,000 projectiles, the three published examples weigh around 50 gm and are therefore close to the sextans.

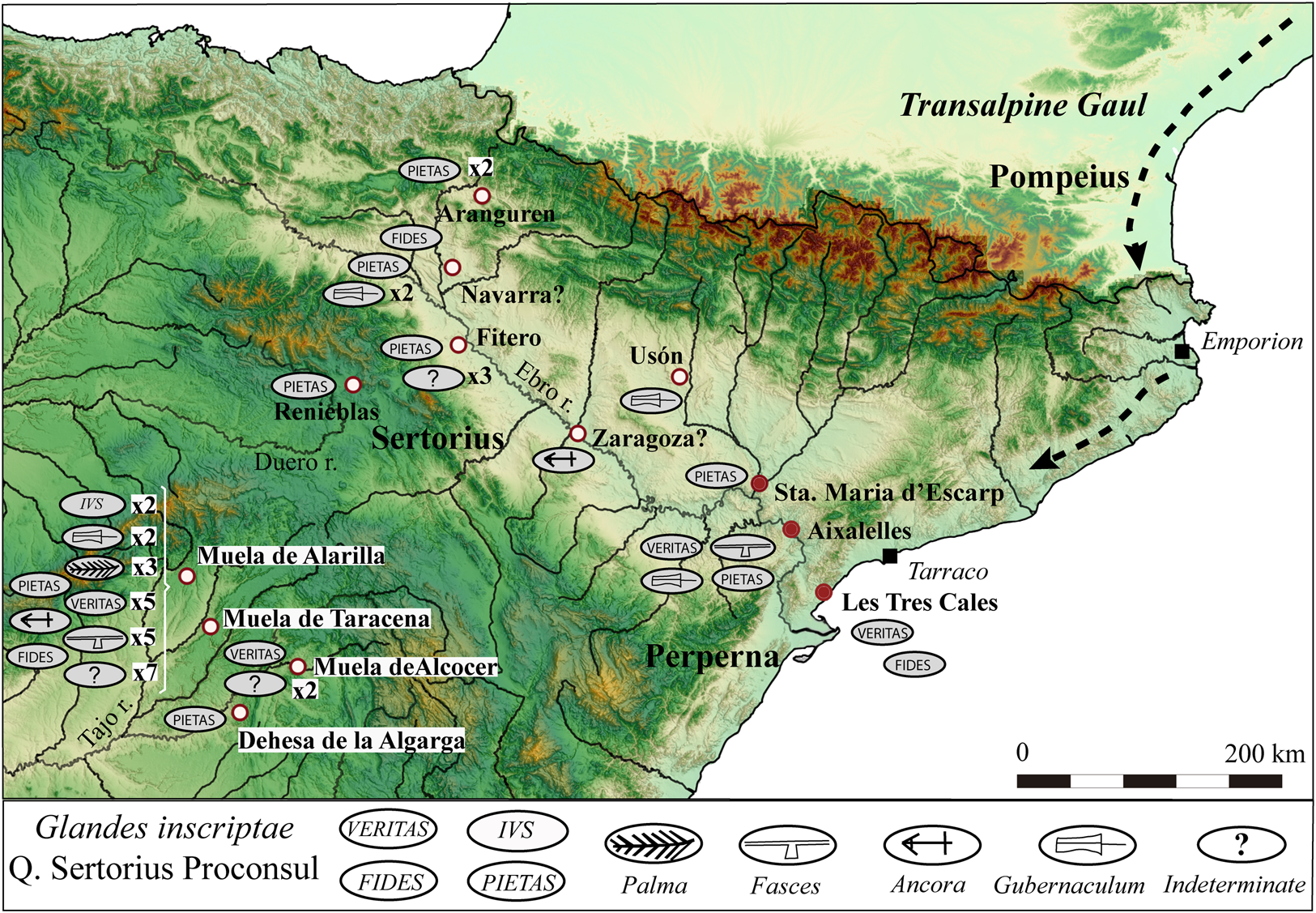

Without a doubt, what best characterizes the historical context of the settlements along the lower reaches of the River Ebro are sling bullets with the inscriptions Q.SERTO or Q.SERTORI / PROCOS (Fig. 10). In total we have found seven projectiles of this type, with the formulations VERITAS, FIDES, and PIETAS and the fasces and gubernacula symbols on the opposite side. The finding of these projectiles fits perfectly with the distribution of the rest of the Sertorian glandes inscriptae documented along the length of the Ebro axis.Footnote 81 Most of these were isolated finds, although sometimes they were discovered along with militaria, Roman Republican coins, or the remains of weapons. This is the case, for example, for the finds from the possible Sertorian camp of Cintruénigo-Fitero in Navarra, which include coins, stone ballista balls, a pilum catapultarium head, and dozens of lead slingshot projectiles, among which were four with the inscription Q.SERT, one with PIETAS on the other side.Footnote 82 Another two projectiles with the inscription PIETAS were found at Irulegui Castle in Aranguren (Navarra); a projectile from Gabarda in Usón (Huesca) bears the gubernaculum symbol; a projectile with the ancora symbol was found in an unspecified place in the province of Zaragoza; and another four projectiles from Navarra include two with the inscriptions PIETAS and FIDES and two more with the gubernaculum symbol.Footnote 83

Fig. 10. Map of the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula showing the distribution of the projectiles with inscriptions referring to Q. Sertorius. (Map by the authors.)

However, the finds of this type of projectile also describe a second distribution pattern, following an axis perpendicular to the Ebro valley between Soria and Guadalajara (Fig. 10). A projectile with the inscription PIETAS comes from the Roman camp of Renieblas.Footnote 84 More than half of the Sertorian projectiles on the Iberian Peninsula have been documented in the province of Guadalajara: a total of 32 examples from the localities of La Muela de Alarilla (Alarilla), La Muela de Taracena (Taracena), Dehesa de la Algarga (Illana), and La Muela de Alcocer (Alcocer), along the courses of the rivers Tajo and Henares and relatively close to each other.Footnote 85 Six of the examples have the inscription VERITAS, one FIDES, and two PIETAS. The ancora symbol is documented once, the fasces symbol five times, and the gubernaculum symbol twice. There were also two projectiles with the legend IVS and three with the palma symbol, motifs that have not been found anywhere else on the Iberian Peninsula. In the case of Dehesa de la Algarga, the projectiles have been linked to the ancient Carpetanian town of Caraca (probably Virgen de la Muela, Driebes), whereas for La Muela de Alcocer a link with a Roman camp has been proposed.Footnote 86

There is a noteworthy absence of projectiles of this type on the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula, despite the intensive military activity in that area, above all during the campaign of 75 BCE, when Valentia was destroyed and Pompey and Sertorius clashed in Sucro, an area that also had several Sertorian garrisons.Footnote 87

It is difficult to determine the precise chronology of the 57 projectiles with the inscription Q.SERTO, given that none has a stratigraphic context. Nor does there appear to be a clear pattern in the distribution of the inscriptions or symbols. Dates have been proposed that coincide with conflict activity in the area of the finds. For example, Miguel Beltrán proposes that they should be dated between 77 and 74 BCE, as they are found in areas of Sertorian activity at a time when that faction enjoyed a more consolidated position.Footnote 88 Armin Stylow dates the projectiles between the beginning of the conflict and approximately 76 BCE, as does Borja Díaz Ariño.Footnote 89 In the case of the projectiles found in Navarra, Javier Armendáriz considers they are from between 76 and 74 BCE.Footnote 90 The presence of these glandes inscriptae in the present-day province of Guadalajara has been interpreted as a consequence of Hirtuleius's or Sertorius's campaigns in 77 BCE, as they advanced toward the Ebro valley, or at a later date during the optimates' offensive in the final years of the conflict. Emilio Gamo proposes an earlier chronology of 78–77 BCE, whereas María José Bernárdez and Juan Carlos Guisado link the projectiles to the optimates' campaigns of 75 and 74 BCE.Footnote 91

Discussion: reconstructing the Sertorian War

Sertorius reached the height of his military power during the autumn and winter of 77–76 BCE, when he enjoyed his greatest control over Hispanic territory and had just received 20,000 legionaries from Italy under the command of Perperna. He clearly expounded the strategic proposals of the following campaign as reported by Livy.Footnote 92 The main objective was to prevent Pompey, who was situated in the Pyrenees, from joining up with Q. Caecilius Metellus. Thus, while Hirtuleius was charged with slowing down Metellus in the south of Hispania, Perperna was doing the same with Pompey in the northeast, stationing his troops in the lower reaches of the River Ebro while continuing to avoid open field combat (Fig. 11). Sertorius's own troops occupied the middle and upper course of the Ebro to prevent a possible Pompeian incursion.

Fig. 11. Map of the Iberian Peninsula, showing the locations of the main actions in the conflict between 76 and 75 BCE. (Map by the authors.)

Control of the center of the Iberian Peninsula was fundamental to this strategy, allowing Sertorius to quickly relocate his armies, precisely to the area in which the largest number of inscribed projectiles has been found. Moreover, the movement of the armies and of their supplies during the conflict is testimony to the multiple connections that existed between them. In this sense, military activity on one site could have results in other theaters of the conflict, as demonstrated by the numerous signs of destruction, abandonment, or major transformation in northeastern Hispania. The military sites and roads, the majority of which predate the Sertorian War, facilitated this connectivity, reinforced by new strategic installations.Footnote 93 Without offering an exhaustive list, following the southern slopes of the Pre-Pyrenees, we can mention the castella of La Vispesa (Tamarite de Litera, Huesca), Monteró (Camarasa, Lleida), and Sant Miquel (Sorba, Barcelona), and the logistics cantonment of Camp de les Lloses (Tona, Barcelona).Footnote 94

The sites presented in this article correspond to the specific needs of the Sertorian strategy. Les Aixalelles and Santa Maria d'Escarp can be understood as related to the defense of the access to the Ebro valley and Iltirta/Ilerda. It seems reasonable to assume that the town, which was where Manlius concentrated his troops in 79 BCE, was by that time under Sertorian control. Furthermore, Ilerda was one of the last towns to surrender to the optimates. It is significant that both sites, Les Aixalelles and Santa Maria d'Escarp, control the access to Ilerda from the south and also the crossing of the River Ebro. La Palma and Les Tres Cales had a similar role: they controlled the Via Heraklea, the most important road along the coast between Gallia and the Levante region. Several fortifications in use during the conflict are spread along the Via Heraklea, including the oppida of Kerunta (Sant Julià de Ramis, Girona) and Olérdola (Tarragona), and the castella of Puigpelat (Tarragona) and Costa de la Serra (La Secuita, Tarragona).Footnote 95 The last three sites surround Tarraco, highlighting its importance as a communications hub, both for the Sertorians and for the optimates, that offered an easy connection to Ilerda and the Ebro valley.

In the spring of 76 BCE,Footnote 96 Pompey began to march southward following the Mediterranean coast, where the Indiketes and Lacetani were his allies,Footnote 97 while Sertorius was able to count on the Ilergetes, Ilercavones, and Contestani, among other peoples (see Fig. 11). In this context, Pompey came to the assistance of the town of Lauro, which was under siege by Sertorius.Footnote 98 Contrary to general opinion, we propose a new location for this town north of the Ebro and not to the south.Footnote 99 If we follow the traditional opinion, it would imply a very large retreat for Pompey and his army. In fact, after the defeat at Lauro, Pompey once again took refuge in the Pyrenees, rather than to the north of the River Ebro, which would have been the logical option had he been in control of that area.Footnote 100

During the following campaign in 75 BCE, Pompey was able to cross the River Ebro, defeat Perperna's and Herennius's troops and conquer Valentia, but he was brought to a halt by Sertorius a little further to the south, at Sucro. Nevertheless, the real turning point in the conflict was Metellus's victory over Hirtuleius, as it allowed the optimate armies to unite. That signaled the beginning of the slow decline of the Sertorian armies. In 74 BCE, Sertorius retreated toward Celtiberia and continually had to assist towns that were being besieged by Pompey and Metellus in the north and in the Ebro valley. In 73 BCE, Pompey took possession of a large part of the Mediterranean coast and Celtiberia. Amid defeats of the populares faction, Sertorius was betrayed and assassinated in 72 BCE and shortly afterward Perperna was defeated and killed. In this historical context it seems obvious that the archaeological footprint of the conflict in the far northeast of the Iberian Peninsula would have to be dated to between 77 and 74 BCE, during which time there were multiple confrontations in the area.

As highlighted previously, the connections between Hispania and Transalpine Gaul were developed during the 2nd c. BCE, as underscored by Manlius's expedition.Footnote 101 Control of the northeast was paramount to the optimate strategy, as it connected its rearguard, Gaul, with the main theaters of conflict, the Ebro valley and the Mediterranean coast.Footnote 102 Not only was Transalpine Gaul a passage through which to move troops and resources but, after Pompey's campaigns and reorganization in 77 BCE, it provided the logistic support required by the armies operating in Hispania.Footnote 103 However, two years after crossing the Pyrenees Pompey had already exhausted his resources. The letter he wrote to the Senate in the winter of 75 BCE appealing for more financial resources reveals the logistical difficulties the optimates were experiencing.Footnote 104 In response to his request, Pompey received two new legions, and a new governor, M. Fonteius, was appointed for Gallia Transalpina for the period 74–72 BCE.Footnote 105 He provided the supplies needed, recruited cavalry units, reconditioned the Via Domitia, and provided shelter for part of the army during the winter.Footnote 106 The accusations of corruption faced by Fonteius at the end of his governorship, probably the product of ad hoc requisitions, point to the massive pressure placed on the province to sustain the armies. The presence of auxiliary troops and supplies from Gaul appears to be reflected in the finds on the Iberian Peninsula of coins from Massalia and issues from different towns in southern Gaul.

The distribution of sling projectiles with inscriptions alluding to the virtues and attributes of Q. Sertorius along more than 300 km of the Ebro valley, from the Pyrenees in Navarra to the river mouth on the Mediterranean, corresponds to the strategy proposed by Sertorius in the winter of 77–76 BCE, when he was readying troops, distributing provisions, and organizing the manufacture of weapons.Footnote 107 This logistical effort, with its complex and structured deployment over a considerable distance, could only be maintained during 76 and 75 BCE, precisely the years in which Sertorius controlled a large part of Hispania Citerior and was at the peak of his prestige and support among the indigenous peoples. Therefore, we believe that the archaeological sites of Santa Maria d'Escarp, Les Aixalelles, Les Tres Cales, La Palma, and many others along this axis were occupied by detachments of Sertorian troops during that period. When Perperna found himself outflanked on the River Ebro during the campaign of 75 BCE, the deployment lost its raison d’être.

Conclusions

The research presented in this article shows the possibilities of a detailed analysis of sites such as Roman marching camps that were not only temporary but have also been extensively altered by postdepositional processes. In these extreme cases, the absence of structural remains and the lack of archaeological context for the artifactual evidence is somewhat compensated for by the absolute dating deduced from some of the finds, in particular coins and inscribed slingshot bullets. This study has proposed that particular artifact types are indicative of military occupation during the Sertorian War: Iberian coins, Nauheim fibulae, Piatra Neamț jars, and glandes inscriptae. All the sites mentioned share various concentrations of these artifacts and a privileged geographical location on the banks of the River Ebro or the Mediterranean coast. Further comparison of the similarities and differences in the record between these and other known archaeological sites allows us to understand a historical conflict such as the Sertorian War on a regional scale. The combination of the chronological information from the artifacts and the historical account from written sources allows attribution of the whole military deployment to a particular campaign between 76 and 75 BCE.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for their thoughtful comments, which have contributed greatly to improving this article. Research for this article was funded by the quadrennial projects of the Catalan Regional Government Department of Culture 2014–17 (2014/100775) and 2018–21 (CLT009-18-00031), War and conflict in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula in the Roman Republican period (3rd–1st c. BCE). Support was received from the University of Barcelona Faculty of Geography and History Research Committee.

Supplementary Materials

The Supplementary Materials contain tables documenting the Roman, Iberian, and other coinage found at La Palma, Les Aixalellas, and Les Tres Cales. To view the Supplementary Materials for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047759422000010.