INTRODUCTION

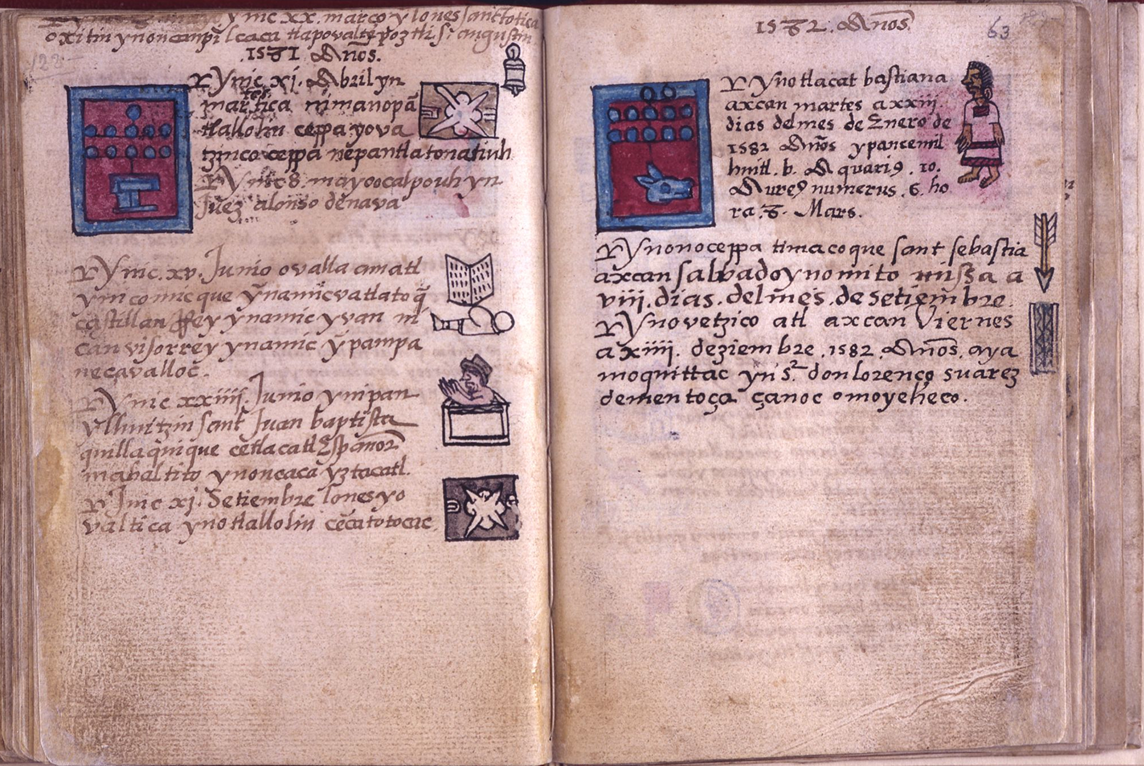

In Mexico City, in the last quarter of the sixteenth century, a painter, whose name is not yet known to us, set down the events of the year 1581, measured in the soon-to-be-replaced Julian calendar. Shortly if not immediately after, the scribe added an annotation in Nahuatl, the principal Indigenous language of New Spain, to describe the same event (fig. 1). “On the 15th of June, a document arrived: the wives of the great lord and Castilian king and of our viceroy here had died; for them, a fast was held.”Footnote 1 In the artist's rendering the dead woman appears as a shrouded corpse, the figure almost certainly representing Philip II of Spain's beloved third wife, Anna of Austria, who died on 26 October 1580 (fig. 2). Habsburg subjects learned of the death through a document called a cédula (a command issued by the monarch), sent to cities throughout the vast territories that Philip controlled. One was dispatched by boat to Mexico City, the capital of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and was received about eleven months later.Footnote 2 Well aware of such transmission, the painter of what is called the Codex Aubin included an image of the received cédula above the bundled corpse, capturing its folded folio format.

Figure 1. Creators whose names are not yet known. London, British Museum, Am2006, Drg. 31219, fols. 62v–63r. Ca. 1576–1609. Ink on European paper. Cited as Codex Aubin. This and other images of the Codex Aubin published under the terms of a CC BY-NC-SA license. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 2. Shrouded corpse of Queen Anna of Austria with royal cédula above. Codex Aubin, fol. 62v, detail. Author photo.

That sheet of paper was not just the bearer of news from far away: it resulted in a cascade of participatory happenings in Mexico City involving the city's inhabitants, both the grand and the low. Bells in churches across the city would have broadcast the news to the city's estimated ninety thousand residents. To pay homage to the queen, local officials would have gathered in the great main plaza of the city dressed in full mourning.Footnote 3 Then, as today, this plaza was one of the largest urban plazas in the world, and it is captured in a map created some two decades after the queen's death (fig. 3). It reveals the basic layout of the urban core, and some of the building details. Facing the plaza on the eastern side was the viceroy's palace, particularly distinguished in this rendering by the three coats of arms that decorate each of its three portals. The viceregal household may have witnessed some of the commemorations from the windows of the spacious building. The cathedral, where masses said for the queen would have taken place, stood at the north side of the plaza, with the map revealing its unusual north-south orientation.

Figure 3. Plaza Mayor of Mexico City and the buildings and adjacent streets, oriented with north at top. Spain, 1596. Ink on paper, 56 x 42 cm. Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte, Archivo General de Indias, MP-MEXICO, 47.

Over two generations of scholars have understood Habsburg festivals, like the one recorded in the Nahuatl annals, as the mechanism through which distant monarchs established their legitimacy in front of subjects, many of those peoples quite remote from royal courts.Footnote 4 When it comes to explaining the efficacy of such festivals, scholars have pointed to their visible effects, drawing on concepts of the spectacle and the simulacra.Footnote 5 These emerged in the late 1960s with Guy Debord, and were subsequently echoed in the work of Jean Baudrillard in the 1980s.Footnote 6 Most prominent among these scholars have been Victor Mínguez Cornelles and Alejandra Osorio, the latter arguing that “central to the cultural viability of the imperial political system was the presence of the king in the form of simulacra.”Footnote 7

But Habsburg legitimacy is often assumed as a given, rather than something that needed to be earned: presenting a public with a simulacra of a monarch does not necessarily mean a public accepts the authority of that simulacra, nor of the monarch it represents. And the collective participation that festivals demanded does not mean that those disparate peoples whom the Habsburgs claimed as subjects necessarily came to collectively define themselves as such. Given that Habsburg festivals may have been the most important way that the abstract idea of Habsburg sovereignty was presented to a vast multiethnic and multilingual public across its transatlantic and transpacific domain, the efficacy of their reception seems no small matter. To wit, the successful imposition of this particular political hierarchy, with a powerful distant European king sustained by the productive labor of his subjects, set up a basic relationship of power that determined a center and its relative periphery. Postcolonial theorists have underscored that the sixteenth century was the formative period of modernity, and its world ordering has led to current inequities across the globe, known in shorthand as the Global South. As Aníbal Quijano has argued, “America was constituted as the first space/time of a new model of power of global vocation, and both in this way and by it became the first identity of modernity.”Footnote 8

While the creation of racial classifications is central to Quijano's argument, I turn to the question of space/time that he also raises. In this vein, I center on the role of the festival, specifically during the reigns of Charles V and Philip II, to argue that its efficacy rested on two foundations. First, it occupied places already saturated with meanings, and, like a parasite, fed on these already established meanings. And second, it helped establish new temporal orders. Thus, this essay is set out along two broad axes—space and time. And these axes become the means to chart a much more restricted phenomena: the festival culture in the urban center of Mexico City from about 1500, when it was the capital of the Aztec empire, until about the time of the death of Queen Anna. I argue that the redeployment of particular spaces—charged with meaning by Indigenous residents of Mexico City long before the Spanish invasion of 1519–21—was crucial to the public legitimacy of the Habsburg festival. In looking at the spaces within which these festivals were first staged, I show that festival organizers could, and did, make use of an urban form that had been earlier designed by the city's Mexica founders to display the triumphal presence of the Indigenous ruler. During the first decades of the sixteenth century, when Spanish conquistadores and administrators were consolidating their hold over the city, they repurposed the streets and plazas used for ceremonies and redirected their former associations toward new ends.

In addition to taking place in spaces that themselves were rich with meaning, Habsburg festivals were also efficacious because they promoted a particular means of temporal orientation. Here, I draw on the work of the German-British sociologist Norbert Elias,Footnote 9 who underscores the social value of calendars in orienting human activities. In looking at calendars, I will center on the manuscript book that opened this essay, the Codex Aubin. This work sits at the confluence of two book traditions, Nahua and European.Footnote 10 Its hybrid nature is evident in its format and content, particularly the use of annals to structure the historic account, a kind of record-keeping found in both traditions. It documents over four hundred years of history across eighty-one folios, more than three-quarters of them transpiring before the arrival of Europeans. It sets events according to the Indigenous calendar, and prominently features this count on the opening bifolio (fig. 4). As the Codex Aubin will show us, the inescapable permeation of a new Habsburg calendar time scale led to the reorganization of urban life, a reorganization that was essential for the fashioning of Habsburg subjects. This Indigenous book offers rare evidence of how the imposition of Habsburg time scales meant the erasure of other possible calendar time scales, both Indigenous and European ones. This imposition was not without resistance, as the example of the Mexica calendar will show. And as we will see, time scales were in flux across the sixteenth century, and the viability of the Habsburg one depended upon the marginalization of others.

Figure 4. Opening bifolio showing Indigenous calendar of fifty-two years. Codex Aubin, fols. 1v–2r. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Coming to the Habsburg festival as an art historian who has studied urban Mesoamerica, the culture region encompassing Mexico and Central America, my starting and ending point will be Mexico-Tenochtitlan, the urban center founded by the Mexica, an ethnic group that historians would later call the Aztecs, which was refounded as Mexico City after the Spanish invasion led by Hernán Cortés in 1519–21. This urban center was a place of radical inventiveness, its impact felt both in the Americas and in Europe.Footnote 11 It had the resources, both material and intellectual, to be so. As a former center of an Indigenous empire, Mexico-Tenochtitlan had a highly developed bureaucracy and a stratified society that included an intellectual class. Its sophisticated urbanism, as well as the material wealth that the Mexica had amassed because of their tributary system, attracted the conquistadores and other immigrants as residents, and by 1535, the presence of the viceroy made it the capital city of the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The coincidence of great wealth, material resources, and human talent, in addition to the high value that Iberians placed on cities generally, made Mexico-Tenochtitlan a kind of testing ground for Habsburg imperialism. In the period that is the focus of this essay, the outcome of that European project, particularly the role of the monarch as the cynosure of a diffuse empire, was far from consolidated. Also in development was the role that urban form would play in that consolidation. Looking at Habsburg festivals from the vantage of Mexico-Tenochtitlan in this period allows new purchase on the role of Amerindian urbanism in the creation of empire.

MEXICO-TENOCHTITLAN AND EARLY FESTIVALS

On the heels of the capitulation of the Mexica monarch Cuauhtemoc in 1521, the local Spanish government, or cabildo, of Mexico-Tenochtitlan began organizing urban festivals to commemorate the European victories of Charles V (in 1524) and then their own on American soils (beginning 1528).Footnote 12 Initially, such public displays were acts of bravado, given that scope of the cabildo's power vis-a-vis the traditional authority of Indigenous lords was far from certain in this first decade after the capitulation, a situation reflected in nomenclature. Indeed, from the 1520s to 1540, members of the Spanish city government did not call their city “Mexico City” as it would later be known, and instead called it “Tenochtitlan Mexico” (both the spelling of Tenochtitlan and the order of the terms was variable).Footnote 13 The first part of the name, Tenochtitlan, was the name that the Mexica had given their city from the time of its foundation in the fourteenth century. The second part, “Mexico,” was a locative, meaning “place of the Mexica.” Across the sixteenth century, the majority of the city's residents would have identified as Mexica, and the vast majority of them would have spoken Nahuatl. When the name “Tenochtitlan Mexico” was used by the Spanish cabildo, it provided an acknowledgment, and often not a very confident one at first, that the space they occupied had belonged to others before they arrived.

The cabildo staged the first commemoration of Cuauhtemoc's capitulation in 1528, some seven years after the event, on August 13, the feast of San Hipólito.Footnote 14 They would reenact this every year for almost the next three centuries. What distinguished this festival was less its composition than its trajectory. A cavalcade, including cabildo members on horseback, would march from the Plaza Mayor, at the time the nucleus of the Spanish city, and then westward along one of the city's main axes. Its trajectory thus reprised the route of Hernán Cortés's badly beaten forces, who were ejected from the city during the so-called Noche Triste on 30 June 1520. By the mid-sixteenth century, the city's Indigenous residents would be corralled into the church set at the end of the processional route, also named for San Hipólito, to listen to sermons likening their forebears, some of whom died to protect their city and their political autonomy, to “the devil's men.”Footnote 15

The early date, and the known route of the procession of San Hipólito, reveals a key difference from coeval European processions. In one of the first volumes of essays dealing with European festivals, published in 1956, Henri Chastel pointed out that festivals did not take place in designated urban space, but rather, “their space is the quotidian space of a town, a street, a plaza, a courtyard . . . metamorphosed by decoration. Born of a provisional adaptation of the environment, the place of the festival is entirely imaginary.”Footnote 16 By contrast, certain spaces in the city of Mexico-Tenochtitlan were both embedded with historical meaning and engineered for ceremony. A low-slung island city in a seismic zone, the urban center had first been envisioned and then built as a great stage set by its original Mexica engineers.Footnote 17 Great raised causeways, functioning as both dikes and roads, connected the city to the lakeshore.Footnote 18 When the city was under Mexica rule before the invasion, the causeways allowed visibility to the monarch. Particularly after a successful campaign of conquest, he would parade into the city wearing an elaborate outfit that likened him to a deity, accompanied by his army and the defeated warriors destined for sacrifice.Footnote 19 The raised roadways upon which he marched led directly to ceremonial centers where stepped pyramidal temples offered elevated stages for public ritual; the open spaces in front of the pyramids allowed for many to congregate.Footnote 20 Unlike imperial processions in European cities, however, where participants clotted their narrow arteries, rarely reaching a moment of mutual visibility, Mexico-Tenochtitlan was designed as an urban frame to allow visibility for these events.

Far from being a blank screen on which to project an imagined festival, the Mexica city demanded a reckoning by the conquistadores and early immigrants. Impossible to ignore was the material presence of the pre-invasion city. For over two centuries, the Mexica had hauled dressed stone from quarries outside the capital to build the great ceremonial center at the heart of the city, which may have contained as many as seventy-eight structures within a walled precinct. The largest of these was the pyramid of the huei teocalli, now known as the Templo Mayor, which was enlarged periodically, reaching 45 meters high, with a base of 400 meters on each side by 1519.Footnote 21 At its top, two shrines were placed. These shrines, like the pyramid as a whole, faced west, and were carefully oriented along the solar axis. The sun, as it rose on the spring and fall equinoxes, appeared to rise directly from the cleft between the tops of the two shrines. Other ritual buildings, including the recently excavated ballcourt and tzompantli, or skull rack, were set to follow the axial planning established by the Templo Mayor, and among these buildings were low platforms, only a few meters high.Footnote 22 Such careful orientation was proof to the populace at large of the synchronicity of the city to the larger cosmic order.Footnote 23 Monolithic sculptural programs, some intricately carved works weighing as many as 24,000 kilos, were set on the outside of buildings, with older works carefully cached within.

Beginning around 1524, work gangs of Indigenous laborers conscripted after the invasion would have been sent to dismantle the buildings. The stone was repurposed for new construction, like the cathedral, and sculptures were buried or cut up for building materials. A choice few were left on view.Footnote 24 Once leveled, the Templo Mayor was covered up to serve as the foundation for new buildings, a state in which modern archeology found it beginning in 1978. The subsequent unveiling of the Templo Mayor has provided a wealth of archeological information about the architecture, sculpture, and ritual practices in and around that building.Footnote 25 But given the construction of the modern city, there is limited evidence about the size of the larger ceremonial center and its appearance at the time of the Spanish invasion. Eyewitness accounts by conquistadores dwell on the sacrificial practices more than the architecture, but they are united in confirming that the city included large open spaces, although most of them would have been outside the ceremonial precinct.Footnote 26

The eventual plan of the city center makes clear that what developed after the invasion was the result of a policy of reuse and reinscription (fig. 5). A great east-west axis once extended from the base of the Templo Mayor, and this raised road, with an aqueduct at its center, was one of the three main entrances and exits from the prehispanic island city. Used as a ceremonial axis by victorious Mexica armies before the invasion, after 1528 it served the cabildo as they commemorated the fall of the last Mexica ruler on August 13. By marching to the outskirts of the city along this route, members of the cabildo recast the historical associations of one of the city's most important axes from that of Spanish defeat/Mexica victory to that of Spanish triumph. In other parts of the city, and outside of it, the mendicant orders often chose to build churches directly on the base of temple platforms; as these served Indigenous congregations, the friars meant to rechannel Indigenous devotion to a new Christian deity.Footnote 27 But the Spanish cabildo, in charge of assigning lots to a new caste of Spanish occupants within the city, clearly avoided this option. For them, Mexica sacred ground was something to be avoided, as new archaeology showing the intended erasure of the tzompantli has revealed. Resetting the principle axis from the east-west solar axis oriented to the Templo Mayor to a new north-south axis offered an opportunity to change the ceremonial pattern of the Mexica city.Footnote 28 Thus, the lot given to the church in 1527 backed up against the earlier Mexica axis, and the resultant cathedral was oriented with its main portal to the south, effectively turning its back to the city's earlier processional route.Footnote 29 Having awarded itself a site opposite that of the cathedral, the cabildo established the dominance of the north-south axis at the center of the city, leaving the former site of the Templo Mayor to be covered over by other buildings. At first, the former palaces of the Mexica lords served as the houses for conquistadores, and these would be rebuilt over time following the same footprint. The palace on the eastern side of the plaza was first occupied by the Cortés family and later served as the site of the viceregal palace.Footnote 30

Figure 5. Schematic map of the center of Mexico-Tenochtitlan, showing Mexica Templo Mayor in relation to Spanish constructions of the sixteenth century. Author drawing.

The large open spaces that were a feature of the Mexica city must have left an impression on the members of the cabildo. Faced with the relative emptiness of the city center left after Mexica religious buildings had been dismantled and Mexica elites killed or forced out, the cabildo preserved an open central plaza and made these forms enduring features of the Habsburg capital.Footnote 31 In the San Hipólito festival, for example, cabildo members made good use of the enormous main plaza, about the size of six soccer pitches, which allowed them to be seen as their cavalcade came together; the broad elevated causeway leading out from the plaza to the west raised the cavalcade above street level. When the cabildo marched, their procession could be viewed, and perhaps heard, across the city.

This carefully planned ceremonial center of the Mexica city, with its clear axes, sightlines, and open spaces, pushed the first generations of Spaniards to rethink, or perhaps think about for the first time, their own conceptions of urban space and its potential for enabling empire. When the cabildo named its first official historian, Francisco Cervantes de Salazar (1513/14–75), he expressed his vision of the city in a set of dialogues, written in Latin and published in Mexico City in 1554. In them, two characters, Alfaro and Zuazo, ambulate around the city, and while walking down the Tlacopan (later known as Tacuba) causeway, one of them proclaims: “How large and wide! How straight! How level! And all of it cobbled, so that in the rainy season it not turn to mud and be dirty. In the middle of the street, serving both as embellishment and for the convenience of the residents, water runs uncovered in a canal, so that it be more agreeable.”Footnote 32 As the characters enter the plaza, Zuazo declares: “We are now at the plaza. Consider carefully if you have seen another equal to it in greatness and majesty.” And Alfaro replies: “It is certain that I can recall no other, nor do I believe that one could find a similar one in either world. My God! How level and extensive! What happiness! What adornment on tall and magnificent buildings, arranged to the four winds! What regularity! What beauty! What organization and siting! It's true that if you would remove half of that arcade opposite, an entire army could fit within it.”Footnote 33

The text draws on an established contrast between the so-called New World of the Indies and the so-called Old World of Europe, clearly proclaiming the superiority of the former; at the same time, the specter of an “entire army” conjures the military operation that allowed Spanish occupation. Arriving to New Spain around 1550, Salazar may have well appreciated the advantages of his local plaza's size, as he may have had occasion to witness the entry of the second viceroy, Luis de Velasco, in 1550. The first such entry was enacted with the arrival of Antonio de Mendoza in 1535, and with his successor, the plaza's potential was again harnessed, inaugurating what would become the most expensive of all Habsburg rituals.Footnote 34 As cosponsor of the festival, along with the church, the cabildo could draw on its organizational experience. Because the viceroy arrived from the east, the chosen route into the plaza made use of another set of wide streets, a feature of the Mexica city, before culminating in the plaza, where the spectacle of the arriving viceroy could be witnessed by tens of thousands, a capacity that the plaza still enjoys today.Footnote 35

Such potentials inherent in the Mexica urban form were quickly conveyed to Charles V; he first read about them in letters sent by Cortés. He would also have first glimpsed this spectacular urban design in the map that Cortés sent to Europe in 1520 (fig. 6). We know of this map from a version printed in Nuremberg in 1524, where the city is shown as an island, ringed by a circular lake. Its prototype was likely by a Mexica mapmaker, who amplified certain features, like the size of the Templo Mayor and the large walled ceremonial precinct at the center.Footnote 36 On the prototype, as well as in the printed version, four broad causeways lead out from the ceremonial center and divide the city into four quadrants. These causeways were breached in order to regulate the flow of water around them, as explained in the texts, and then spanned by removable bridges.Footnote 37 The vertical one at the top of the map was the Tlacopan (later Tacuba) causeway, later used for the San Hipólito procession. The broad horizontal causeway to the left was the one on which Cortés first encountered the Mexica monarch, Moteuczoma; his letters describe a thousand people who stood upon it to witness the meeting, and the columns of lords who lined “the walls of the street, which is very wide and beautiful and so straight that you can see from one end to the other. It is two-thirds of a league long.”Footnote 38 The woodcut also shows a number of other causeways that lead out from the edges of the city to connect Tenochtitlan to other cities on the lakeshore, clearly conveying the systematic planning and integrated roadway system. One of them is described in the accompanying letter as “wide as two lances, and well built, so that eight horsemen can ride abreast.”Footnote 39

Figure 6. Map of Tenochtitlan with Gulf Coast at left. In Hernán Cortés, Praeclara Ferdina[n]di Cortesii de noua maris oceani Hyspania narratio (Nuremberg: Friedrich Peypus, 1524). Woodcut, ink on paper, 29.8 x 46.5 cm. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library.

In the years that followed Charles's reception of the letter, commemorations of signal events of his reign were staged in the vacant plaza in the center of the city, and included processions that followed broad avenues of the causeways into the city. The first recorded festival sponsored by the cabildo was to celebrate one of Charles's victories over France.Footnote 40 For the tens of thousands of Mexica residents of the city, the previous use of these same spaces in the center of the city, where the imperial rituals that were staged included the celebration of successful conquests of Mexica emperors and the taking of foreign rulers and their kingdoms, could hardly have been forgotten overnight. After Charles V abdicated in 1556, it was on the spot where Moteuczoma had undergone his consecration as huei tlatoani (great speaker) in 1502, that Indigenous elites, including Moteuczoma's great-nephew, gathered to swear an oath of loyalty to Philip II.Footnote 41 But the spatial coincidence of events alone would not have been enough to ensure the legitimacy of Habsburg rule. Instead, as I will explore in what follows, the Habsburg festival also imposed a new order on time; concurrently, Indigenous time scales were being contested and suppressed.

THE TIME OF THE HABSBURG FESTIVAL IN MEXICO-TENOCHTITLAN

As seen in figure 2, the artist attaches Queen Anna's corpse to the cédula announcing her death. The copy sent to Mexico City was not singular: while it does not survive, the cédula sent to Valladolid does, revealing how festivals commemorating the same event were repeated across great distances. While participants may have been aware of the vast reach of concurrent festivals, they were most likely to remember resonances with earlier, coterminous commemorations. In the Valladolid cédula, Philip II wrote: “We desire to advise you that it is fitting that you would carry out acts of mourning and the other things that in similar occasions you are accustomed and typically do.”Footnote 42 Philip's gesture to customary commemorations reflects that he knew that cabildos had come to develop standard protocols for such events; since they paid for them, they had considerable leverage in their execution, and were often guided by earlier protocols. In Mexico City, for instance, members of the cabildo determined that Queen Anna's funerary rites should follow those of the preceding queen, Elisabeth of Valois, which in turn were modeled on those of Don Carlos, Prince of Asturias.Footnote 43 As I have described, festivals were colored by the valences of local spaces, which in turn accrued meanings from the events that unfolded within them. In addition, while happening (roughly) around the same time, and directed to the same distant happening (like the queen's death), they also synchronized the activities in Habsburg cities across the globe.

To understand the import of the synchronizing function of the festival, it is helpful to turn to the work of Elias. In An Essay on Time, Elias cautioned his reader against the presumption that time exists a priori, instead arguing that time is a set of symbols developed within a society that serve “as a means of orientation”—in its earliest form, he argues, orientation between humans and nonhuman nature, “an active synchronization of their own communal activities with other changes in the universe.”Footnote 44 “The slowness with which people succeeded, over the centuries, in working out a calendar time scale well-tailored in relation to the physical continuum, and capable of providing an articulated, unified synchronizing standard for human beings integrated in the form of states—and now, beyond this, for a global network of states—shows how difficult this task was.”Footnote 45 Elias located the formalization of a so-called developed calendar time scale in the early modern period, as Europe made a slow march toward the evolution of modern industrial nation-states.

While much of Elias's Essay on Time is colored, if not stained, by his presumption of the complexity of a European calendar time scale, as opposed to the allegedly simpler time scales of non-European groups (African villagers, Pueblo Indians), his key insight has cross-cultural applicability. To wit: calendar time scales are a technology that orients human beings to the nonhuman world and to each other. This will help us unpack the meaning and the effects of the far-flung Habsburg festival within its Mexica context.

Moving away from conceiving of a nebulous category of time and instead focusing on timing is a first step. Elias establishes that “timing is . . . based on people's capacity for connecting with each other two or more different sequences of continuous changes, one of which serves as a timing standard for the other (or others). . . . What we call ‘time’ is . . . a frame of reference used by people within a particular group . . . to set up milestones recognized by the group within a continuous sequence of changes, or to compare one phase in such a sequence with phases in another. . . . Sequences at all levels of the universe can be synchronized: at the physical, biological, social, and personal levels.”Footnote 46 For instance, when I state that I was born on October 25, I am simply putting two sequences into comparison—the first being the sequence of my individual life, and the second the sequence of the solar year as it was determined by Vatican astronomers and imposed in October of 1582.

Among the Mexica, calendars, and the culturally specific timing sequences they encoded, organized all aspects of human life.Footnote 47 There were two basic Indigenous time-scale calendars (to draw on Elias's vocabulary). One was the sequence of days in the solar year, beginning in March with the observed equinox.Footnote 48 As we saw above, the cleft between the two shrines at the top of the Templo Mayor was oriented so that it framed the equinox sunrise, and this orientation determined the layout of the ceremonial center. Another was a 260-day sequence whose origins are documented in the Americas as early as 600 BCE. One's birthday in this 260-day sequence (called the tonalpohualli) became one's name, and influenced, if not determined, one's fate in life.

We have seen that the Codex Aubin offers a chronicle of events, but the creators of the Codex Aubin emphasized first and foremost its timing standard. The book's opening bifolio introduces the reader to the native fifty-two-year cycle by lining the four edges of the pages with symbols of the years, identified with their names written in pictographic script (see fig. 4). Each year symbol pairs the name of the year (Rabbit, or in Nahuatl, Tochtli; Reed, or Acatl; Flint, or Tecpatl; and House, or Calli) with a numerical counter (1–13), resulting in fifty-two unique year names (as 13 x 4 = 52). On fols. 1v–2r of the Codex Aubin, the year symbols are grouped into four sets of thirteen years each, and begin with the date 1 Rabbit at the lower right. From there, the count continues counterclockwise. A similar calendar opens the Codex Mendoza, a more famous Nahua history written around 1545, as well as other manuscripts, suggesting that the marking out of the calendar was an important first step in historical narratives.

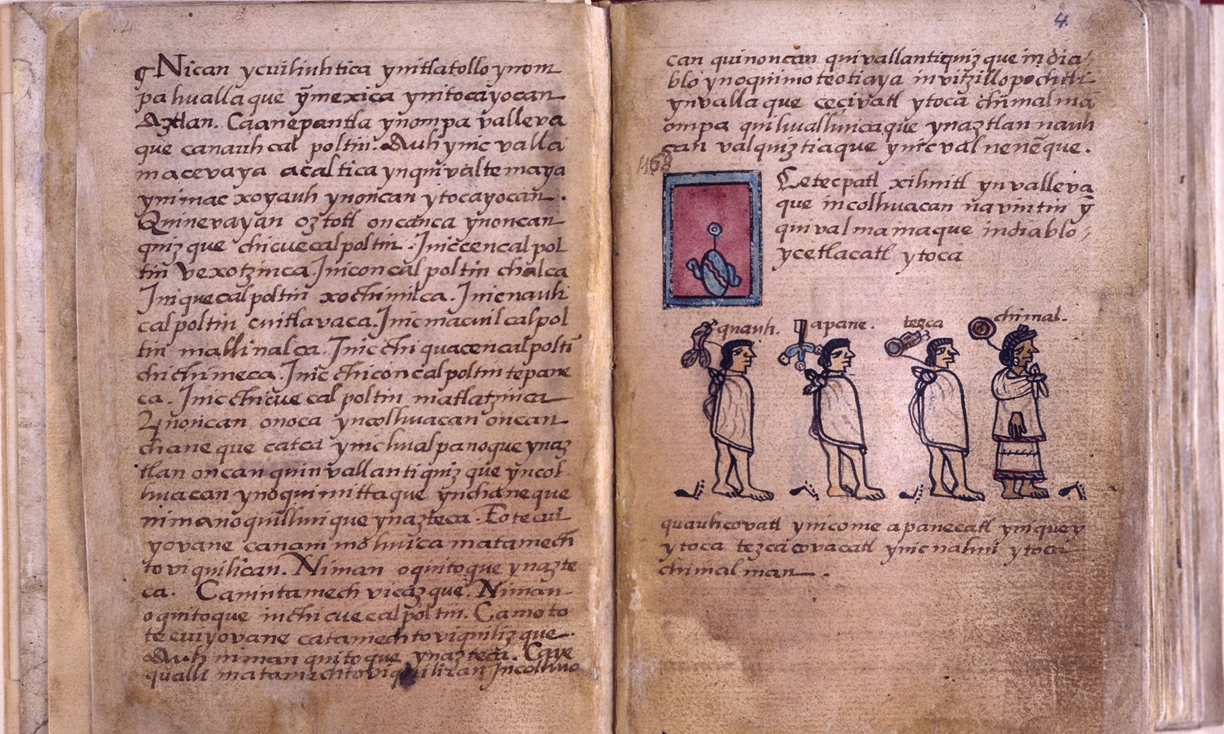

The pages that follow recount the history of the Mexica people, opening with their narrative of outmigration from a semi-mythical place called Aztlan (fig. 7). This narrative was set down in other manuscripts as well. For instance, as Angela Herren Rajagopalan has documented, the account found in the Codex Aubin closely resembles that of the Tira de la Peregrinación (Strip of the peregrination, called this for being painted across a continuous strip of native paper, or tira). The Tira de la Peregrinación probably dates to the 1540s, and its narrative is told with pictographs, rather than alphabetic texts.Footnote 49 Figure 7 shows the first two pages of the Tira, where events of the migration are recorded left to right across the page; at the center of page 1, the date glyph of 1 Flint appears. At right are the four teomamah (elders) bearing the sacred bundles on their backs. Comparing figures 7 and 8 shows that the Codex Aubin deploys many similar pictographic elements, like the date glyph of 1 Flint and the teomamah. However, in the Codex Aubin, many of the other elements are described in the accompanying alphabetic text, written in the Nahuatl language, rather than depicted pictographically.

Figure 7. Migration from Aztlan on the day 1 Flint. Codex Aubin, fols. 3v–4r. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 8. Creators whose names are not yet known. Tira de la Peregrinación, pages 1 and 2, ca. 1540. Biblioteca del Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico City. Author drawing.

When the creators of the Codex Aubin compiled their book in the third quarter of the sixteenth century, instead of using a tira of native paper, they chose to write on European paper to create an octavo size codex, or butterfly book, a format carried across the Atlantic by European books imported into New Spain. A number of hands worked on the book over time. In addition to the scribes who created the alphabetic texts, there appear to have been two main painters who worked on the majority of the book. One set down the icons that represent years in the Indigenous calendar system of central Mexico, deploying a conventional format for the signs that stood for the solar year: bright red cartouches, framed in brilliant turquoise, with year glyph and numerical counters inside; in figure 9, these appear on the left sides of the pages. A second painter created the figures and icons to stand for events that transpired during those years, seen along the right side of each page in figure 9. This second painter exercised considerable inventiveness in designing new images and adapting older ones to express novel phenomena that Habsburg rule brought, as we will see below. On any one page, dates were set down first, and then the images. The opening folio bears a date of 1578, and this seems to mark the date that the main scribe made a clean copy of the book. However, this scribe seems to have continued to add entries, making the last entry in the year 1591 (fol. 67v). The principal artist continued to add images through 1596. In the last three pages of the book (fols. 68r–69r), entries were added by at least three different hands and a different artist.

Figure 9. Events of the years 1559 and 1560. Codex Aubin, fols. 51v–52r. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The choices of language and format strongly suggest that the Codex Aubin was penned by a group of elite bicultural Indigenous scribes, well schooled in alphabetic writing, conversant with conventions of European books, and perceptive observers of the urban life of Mexico-Tenochtitlan. After the invasion, the male children of elite families were often educated in schools run by mendicant friars, where they were taught alphabetic writing as well as other skills. As adults, these men often became the political leadership class, and it was among their number that the book's creators and patrons were likely to have been found. The Codex Aubin offers internal evidence to this point: at some moment in the past, this annals was bound together with a shorter manuscript, also an annals, that offers a stripped down version of the same city's history from the mid-fourteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth century (fols. 70r–78r), mostly documenting the city's Indigenous rulers.Footnote 50 This pairing, and the first set of annals’ focus on public events, suggests that the patrons of both parts of the manuscript were members of the city's Indigenous cabildo, which exercised governance in the city alongside the Spanish cabildo—a body who continued to employ the name “Mexico-Tenochtitlan” long after the Spanish cabildo relegated it to disuse.Footnote 51 The Codex Aubin therefore offers an official Indigenous or Mexica history of the city—that is, the perspective of the elites who controlled the collection of tribute, the organization of labor for public works and ceremonies, and the functioning of markets in the large city.Footnote 52

The second half of the book, particularly the part documenting the events beginning in 1553, provides a rich chronicle of public events in the city, including the festivals marking the lives of the Habsburgs that were celebrated in Mexico-Tenochtitlan. One instance appears on folio 50v, corresponding to the year 1557. On it, the folded cédula appears, held by a gray-clothed royal official and received by a group of four Indigenous lords of the city (fig. 10). They are presented by the book's second artist as heads wearing a distinctive blue headdress made of turquoise mosaic, tied in the back with a red leather strap. Other documents make clear that the cédula called for the jura, or oath of loyalty to Philip II, which took place with an enormous celebration on the Plaza Mayor in 1557. This irregular public festival had less elaborate, but more regular, echoes in the oath of allegiance to the Habsburg monarch that Indigenous elites proclaimed at the beginning of every year when they were confirmed, or reconfirmed, to their offices. On a weekly or even daily basis, they acknowledged the Habsburg ruler in the official documents in Nahuatl that they penned, as these typically would include mixed language phrases such as “governor because of our great lord, on behalf of his Majesty” (“gobernador yn ipampatzinco in tohueytlatocatzin por Su Magestad”), or might include loquacious statements of loyalty in Nahuatl to the Spanish monarch.Footnote 53

Figure 10. The jura, or oath of loyalty to Philip II. Codex Aubin, fol. 50v, detail. Author photo.

In framing a history that ran from the origins of the Mexica as a people to the present, the creators of the Codex set Habsburg events into a much longer span of trans-imperial history, one that the Nahua elite were quite familiar with.Footnote 54 The turquoise mosaic headdress that Indigenous rulers showed themselves wearing during Philip II's jura was that of prehispanic rulers. And the book's artists developed new imagery to align the history of the Habsburgs to that of Mexica rulers. For instance, to convey the death of Queen Anna, the artist used the image of a shrouded corpse (see fig. 1). It is similar to one that appears elsewhere in the text to mark the deaths of prehispanic rulers: among the events of the year of 1520, a similar bundle appears to mark the body of the last autonomous Mexica emperor, Moteuczoma, upon his death (fig. 11). A thin black line attaches the bundle to a small glyph representing a turquoise headdress that served as part of his name glyph. The compact shape of the bundle reflects the pattern of Mexica burials, where the body was flexed, and tied with ropes before cremation. In the Codex Magliabechiano, a manuscript created in the Basin of Mexico in the mid-sixteenth century, one page pictures the white mortuary bundle of a Mexica ruler, whose flexed body is shrouded and wrapped with a rope, placed on a red and orange textile, with rich grave goods around it (fig. 12).Footnote 55 The image, like others in the book, is meant to document Mexica ceremonialism of the past, including mortuary practices, as both flexing and burning were prohibited as part of evangelization efforts in the 1530s, when friars demanded bodies be extended for burial. Taking this into account, the Codex Aubin artist adjusts the image to depict Anna of Austria by rotating the once-standard bundle 90 degrees clockwise, setting the defined head at right, and attaching small stiff legs to the torso, making abundantly clear that this Christian queen was buried in extended fashion (see fig. 2). The evangelization of elites notwithstanding, when post-invasion Mexica rulers are depicted upon their deaths in the Codex Aubin, they appear as flexed bundles.

Figure 11. The mortuary bundle of the Mexica emperor Moteuczoma. Codex Aubin, fol. 41v, detail. Author photo.

Figure 12. Creators whose names are not yet known, flexed mortuary bundle of Mexica lord being prepared for cremation. Codex Magliabechiano, fol. 68r, mid-sixteenth century. Banco Rari 232. By concession of the Ministero della Cultura - Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze. Any further reproduction by any means is prohibited.

It has been well documented how Habsburg monarchs deployed the classical tropes founded in Renaissance humanism to display and legitimize their claims to a universal monarchy across their far-flung realms; the Codex Aubin offers something of a reception history. Upon the death of Charles V, the device of the catafalque, an empty tomb, was deployed in cities across his realm, including in Mexico City. Cervantes de Salazar published a description and a woodcut of the ninety-foot temporary structure, a rare product of the local printing press (fig. 13). The image shows an open-sided, two-storied structure, with twelve Doric columns supporting the entablature, frieze, and pediment of the first story, and four Ionic capitals supporting the domed structure that comprises the second level. At the top of the steps that lead to the raised platform of the first level is the empty coffin, draped in a cloth bearing the coat of arms of Castile and León and the Habsburg eagle. On the second level, a version of Charles V's coat of arms appears as if a three-dimensional sculpture, supported by the Imperial eagle and flanked by the Pillars of Hercules. The adjacent text both describes the elaborate allegorical paintings that adorned it, as well as framing an exegesis for the reader. In rendering the same catafalque on the pages of the Codex Aubin, the painter recreates its two-level open-sided structure and crowning cross (fig. 14). But the complex columnar arrangement is missing, as is much of the classicized vocabulary. Instead, the painter emphasizes the materials—the columns appear to be made of cut blocks, and the span a wide beam of wood, and small dashes of red paint mark the foundation. Given that the catafalque was erected in the open plaza of the Indigenous parish church, San José de los Naturales, headed by the Franciscans, it was very likely sponsored by Indigenous lords, among them cabildo members, who attended the ceremony, and it was certainly built by Indigenous labor.Footnote 56 The rendering by the Codex Aubin artist avoids the classical references and instead emphasizes the building's careful and likely laborious facture—codes more intelligible to a broad Indigenous public than the language of allegory.

Figure 13. Catafalque of Charles V. Woodcut from Francisco Cervantes de Salazar, Tumulo Imperial de la gran ciudad de Mexico (Mexico: Antonio de Espinosa, 1560). Courtesy of the Biblioteca Histórica de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. BH FLL 29563.

Figure 14. The catafalque of Charles V. Codex Aubin, fol 51v, detail. Author photo.

Considered so far, the Codex Aubin provides clear documentation that Habsburg festivals in the viceregal capital were registered by Indigenous population of the city. Moreover, Indigenous elites, who were the probable patrons of the Codex, used the book to document their participation in those rituals. To historians of sixteenth-century New Spain, that Indigenous elites should underscore their cooperation with the new regime may be unsurprising. From the 1520s onward, Indigenous elites looked to Habsburg monarchs to confirm their status and confer new perquisites, some of them traveling to the courts of Charles, and later Philip, to make their appeals directly to the king. Displaced by the invasion, Indigenous elites scrambled for new berths within the Habsburg imperium. Such was the case in other parts of Habsburg realms, and in other colonial empires.

CALENDARS AND DISTEMPORALITY

However, elites were only a small sector of the population, and in the Codex Aubin we can discern another narrative of displacement—perhaps better termed as distemporality—that would impact a much larger segment of the Indigenous populace. This manuscript shows the disruption of the essential order that the time scales of the Indigenous calendar had provided as they coordinated the activities of almost all sectors of society. Such disruption of the temporal order allowed the Habsburgs, through their time-setting festivals, to root themselves into the lives of the peoples who would come to consider themselves their subjects.

To return to Elias's insights, calendars provide “an articulated, unified synchronizing standard for human beings”; in the case of the Mexica and other Indigenous groups, the synchronization was not just to the activities of each other, but also to the earlier patterns established by the actions of deities, as Emily Umberger has extensively documented.Footnote 57 We can see a template for this patterning in the Codex Borbonicus, a Mexica manuscript that postdates the Spanish invasion but conforms closely to prehispanic prototypes of sacred calendars (fig. 15). Across two pages, it shows the same year count as that which opens the Codex Aubin, with each page showing half the cycle—that is, twenty-six years, set to the same beginning and midpoint, and counted counterclockwise. Both begin with the year of 1 Rabbit, and the symbol for this year appears at the lower left of page 19 of the Borbonicus. Unlike the Aubin, however, the Borbonicus makes clear what was transpiring during this time through the images that are set on the center of each of the two pages. On page 19, ancient creator deities perform sacrifices and determine fates. On the second page of the bifolio, page 20, the midpoint of the fifty-two-year cycle falls on the year 1 Flint, appearing in the lower left. In the center of this page, the deities Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca, whose coordinated actions created the habitable earth, are depicted, their two facing figures appearing like a yin-yang inscribed in a circle.

Figure 15. Creators whose names are not yet known, fifty-two-year calendar. Codex Borbonicus, ca. 1525, pages 19–20. Ink and colored pigment on Indigenous amatl paper. Bibliothèque de l'Assemblée nationale, Paris.

Because of the importance of time-scale calendars, calendrical books were the mainstay of the Indigenous tradition. They entered the lives of many more peoples than elites, as they were principally used in a way suggested by the aged deities in the Codex Borbonicus—that is, to prognosticate fates. Such correspondences were not obvious: it took native specialists to divine them, and they did so for a broad public. In another manuscript of the era that recalls the prehispanic past, known as the Florentine Codex, one illustration shows a native priest holding a calendrical book in his hands and a speech scroll emanates from his mouth to represent his breath, one of the animating forces of the Mexica body (fig. 16). Behind him is a sun, shown with a face, another animating force of the Mexica cosmos. The book the priest holds was probably the time-scale calendar known as the tonalpohualli, one that would allow him to augur the fate of the small child being presented by its mother who sits in front of him—that is, to discover ways that the child, as a sequence of biological events beginning with conception and followed by birth, coordinated with the time scale expressed in the calendar. The image emphasizes the role of the prehispanic book as a kind of script for performance, fully realized only when articulated by those knowledgeable enough to do so, and also put to the service of a broad public.

Figure 16. Bernardino de Sahagún and others. The day keeper and newborn child. The Florentine Codex, ca. 1575, book 6, chapter 36, fol. 168v. Ink and pigment on European paper. Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Med. Palat. 219. Image published under the terms of a CC BY-NC-ND license.

The Codex Aubin's creators would have been aware that within the time scale of the Indigenous calendar, human temporal rhythms were aligned to divine ones. For instance, 1 Rabbit, the date of the earth's creation by deities, was also the first year of the fifty-two-year calendar cycle, during which time human beings carried out their own rituals to renew the world. Mexica rulers before the invasion had used the calendar as a tool of empire, and they synchronized cosmic events to events of Mexica history.Footnote 58 This phenomena is clearly seen with the choice of the year 1 Flint to mark the start of the Mexicas’ journey out of an earlier homeland of Aztlan, as it was also the year that the deities Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca had created the earth. Such synchronicity added to the legitimacy of the empire built by the Mexica, and was also carried into the Codex Aubin, where the 1 Flint start date is set prominently at the center of a page (see fig. 7).

As readers turned the pages of the Codex Aubin, they would have encountered three sequences. The first was the sequences of events beginning with the Mexica migration and shown with the figures and texts on the pages. The second was the sequence of solar revolutions as expressed by the blue-and-red year glyphs in cartouches, and the third was the sequence of the pages themselves. These sequences, and the changing rhythm across the span of the book's eighty-one folios, are made visible in a visualization, part of a digital humanities project I developed with my Fordham University colleague Katherina Fostano (fig. 17). When the pages in the first part of the book are set out together, the changing time scales become clear. In the first section of the book, chronicling the great migration after leaving Aztlan, the length that the Mexica stopped at any one place determines the number of years per page. Visualized this way, the book shows the subordination of one sequence, the year count, to another, the events of the Mexica migration—that is, the story of the migration organizes the count of the solar year, not the other way around.

Figure 17. Visualization of the pages of the Codex Aubin, by the author and Katherina Fostano.

At the same time, the visualization of all the pages also makes clear the importance of three events to the Aubin's creators. Three times the march of time across the pages, conveyed by the year-glyphs, is arrested by full-page images devoted to singular events. The first is the moment that the Mexica were called out of Aztlan on fol. 3r, the second when they found Tenochtitlan on fol. 25v (a somewhat problematic page in that the present one seems to be a replacement of a missing folio with the same or similar imagery), and the third the great massacre of elite celebrants by forces under Spanish command during the feast of Toxcatl at the Templo Mayor on 20 May 1520 (fig. 18). It was at this moment that the Invaders’ intention to usurp Mexica rulers and their terrible barbarity became an inescapable fact. The image depicts the same space shown at the center of Cortés's map of the city (see fig. 6), at the moment before the massacre would begin: a harmless musician plays his large drum, and an elegantly dressed lord dances and signs, shown by the blue and red speech scroll emerging from his mouth. But he will be no match for the facing Spaniard, his torso encased in blue steel armor, who wields a steel-tipped spear. Memories of the violence that ensued are confined to the Nahuatl text. No such whole-page image is used to mark anything beyond 1520.

Figure 18. The massacre on the feast of Toxcatl. Codex Aubin, fol. 42r. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

For a 150-year period after the foundation of Tenochtitlan (a period that includes the Spanish invasion)—that is, from 1364 to 1550—five years appear to a page. After 1553, one year appears per page—a pattern that holds through 1591. At this point, a different set of scribes take over, and the year pattern is irregular. The last entry is for the year 1608. The pattern of one year per page was certainly closer in time to the creation of the book, and it may have been that the creators felt they needed sufficient space to record what they may have witnessed. But we also see the solar year emerging as the dominant sequence.

A less obvious sequence is the fifty-two-year cycle. On years named 2 Reed/Ome Acatl, the previous fifty-two years would be bundled, as if they were a set of reeds. Figure 19 shows the way this cycle was represented as bundled reeds. The year glyph 2 Reed/Ome Acatl is a conventional foliate reed symbol, and it is topped by the two dots used as counters. At the base of the reed symbol is a twisted cord, with a prominent knot at the center, the conceptual rope used for tying the years. While eight cycles/reed bundling events fell during the 440 years covered, only one year-bundling year fell within the post-invasion period, in 1559. The book ends in 1608, before the next scheduled century-end of 1611.

Figure 19. The 2 Reed/Ome Acatl year sign. Codex Aubin, fol. 10r. Author photo.

The book's creators (and perhaps patrons) were uncertain about this particular year bundling of 1559, perhaps because it was out of sync with a time scale that was introduced by a Christian calendar, where years were gathered into centuries after every hundred years. The uncertainty registers visually. In setting out the brilliant year glyph for 2 Reed (1559), the first painter omitted the bundling rope that distinguished the other 2 Reed years (see figs. 9 and 19 and fig. 20). Realizing the omission, the second painter addressed the mistake by setting a slightly different symbol of bundled reeds in March of 1560, the date that marked the end of the 2 Reed/Ome Acatl year, when traditional year-bundling ceremonies would have occurred (fig. 21). To emphasize the role of the calendrical book in timekeeping, the painter attached the reed symbol to an image of a book, whose pages are marked with black lines of text and red spots. It bears no small visual resemblance to the Aubin itself, where bifolios carry lines of text and are distinguished by the primarily red cartouches of the year glyphs. The second painter, then, seems to have wanted to underscore the Aubin's coordinating function to the native year count with this meta-book.

Figure 20. The year 1559 and the 2 Reed/Ome Acatl glyph, lacking the bundling rope at its base. Codex Aubin, fol. 51v, detail. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 21. The year 1560, showing the 2 Reed/Ome Acatl glyph, with the prominent knotted rope at its base and the spotted calendrical book above. Codex Aubin, fol. 52r, detail. Author photo.

Outside of Indigenous circles during the late sixteenth century, the coordinating functions of the native calendar were not well understood, and neither was the enormous importance the calendar played in regulating social life, be it ceremonial or quotidian. The closest parallel that Europeans could offer was to judiciary astrology, part of a long medieval tradition with classical roots, whereby the position of the stars and constellations were carefully studied and charted to determine their effects on human constitutions and action. In New Spain, the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún would devote two of the twelve books of his Florentine Codex to astrology, giving book 4 the title “De la astrologia judiciara, ò arte adivinaria indiana” (On judicial astrology, or the practice of Indian divination) and calling book 5 “Las agüeros, y prenosticos” (Auguries and predictions). Sahagún would describe judiciary astrology as “common among us, [and] . . . founded upon natural astrology, which is in the signs and planets of the heavens and in their courses and aspects.”Footnote 59 “Judiciary astrology” would be the same self-descriptor used on the opening folio of the Codex Aubin, where the fifty-two-year calendar is introduced. Unusual for this book, though, is that the scribe writes in Spanish, the only time they do so in the manuscript, as if making an address to a different reader, one who might open just the first page to gauge the book's contents. Within the frame of the Indigenous calendar, the principal scribe describes the count of the calendar thus:

Second judición of the house that is called 1 Reed, which has thirteen years and three Olympiads. In the first house when [?] this land was discovered; in the second house, the Spaniards entered into it; in the third, they won Mexico; in the fourth, they began to build Mexico; in the sixth, the twelve friars arrived.Footnote 60

The gloss makes clear that the writer is attempting to correlate the native time scale with those provided by the astrological houses, used within judiciary astrology to determine the character of events, and, at times, to predict those of the future. Included later in the annals section, the scribe describes the birth of two girls, presumably family members, and sets out the coordinates of their horoscopes (fols. 63r and 64v). While the native calendar was coordinated to the sequence of solar, rather than sidereal movements, a basic commonality between the two systems is clear: Nahuatl speakers held that temporal cycles exerted a determining force on the course of human history and individual lives; Europeans who ascribed to judicial astrology did much the same, with the influences extracted from the movement of the stars rather than the cycles of the sun. The opening page of the Codex Aubin, then, where the Indigenous calendar is presented at the same time that the events of the invasion are aligned to the planetary positions of judicial astrology, speaks to the ways that its creator was trying to synchronize native and European time scales. It also attests to the multiplicity of calendar time scales that coexisted during the sixteenth century.

HABSBURG TIME

In the first decades after the invasion, the imposition of a Christian time scale was highly disruptive: the imposition of a seven-day week forced itself upon the five-day market cycle, and the irregular cadence of saints’ days and commemorations of the events of Christ's life overrode the pattern of the native veintena feasts, celebrated every twenty days. Lunar irregularity was introduced by Easter and subsequent celebrations (Corpus Christi, Pentecost). The sequences of Christian feast days across the solar year were promoted in missals, which were among the first books published in New Spain. But Christian festivals were at least fairly regular within the interval of the solar year. By contrast, Habsburg festivals were irregular, centered around the life cycles of the Habsburg monarch or the movements of his body double, the viceroy. Given that urban life flourishes under predictable conditions, irregular events (out-of-season hail, plagues of grasshoppers, epidemics) were most often unwelcome ones.

The Codex Aubin, in contrast, pays less attention to the cadence of regular feasts, and instead reports upon the irregular intrusions of a Habsburg time scale, one that measured time according to the events of the ruler's life. As befits a book whose patrons were likely the native cabildo and whose legitimacy was, by the time the book was created, part of a symbiotic relationship with Habsburg monarchs, the book is extraordinarily sensitive to local stagings of imperial events. These include those involving the church, given that the Habsburgs oversaw the church in the Americas under the terms of the Patronato Real.Footnote 61 The Codex Aubin most often records events that impacted the Indigenous population, or involving Franciscans, the mendicant order with strongest links to Indigenous urban elites. Of equal importance are those mandated by royal fiat, which the artist marks with the image of the cédula—seen attached to the body of Queen Anna—to record royal commands that demanded a response from the Indigenous government—ignoring the host of cédulas that had no such impact (see figs. 1 and 2). It was a cédula that drew Indigenous lords to make their oath of loyalty to Philip II (see fig. 10), and cédulas that called for new census counts in the 1560s, where they are shown carried by a royal official dressed in gray. With each of these events, the residents of Mexico City were pulled more strongly into the currents of Habsburg time scales, as urban residents were called to participate in marking the life events of the monarch and members of his family. These commemorations replaced those that some Mexica residents of the city would have remembered from before the invasion: the triumph of the military victories of the Mexica monarch, with the parades of captives headed for sacrifice, and the great festivals keyed to solar events and carried out in the name of earlier deities.

As new Habsburg time scales became ascendant, the native calendar time scale to coordinate events gradually unspooled, a phenomena also registered in the Codex Aubin. The concerted effort to coordinate Mexica years with Christian years grows stronger over the sequence of pages. In the earlier part of the book, up to 1540, Christian years were added in the margins of the book, in fainter ink, as if an afterthought to the dominant count. But beginning in the year 1541, subsequent to the artist's setting out of the pictographic years and events, the dominant scribe correlated the Mexica years to those in the Julian, and then Gregorian, calendars at the top of the page (see fig. 9). By this point, the sequence of pages, the sequence of native years, the sequence of Christian years, and the sequence of events in the city are all in sync. And within these pages, the events of the lives of distant monarchs found their place.

CONTESTS OVER TIME SCALES

While the Aubin shows the slow creep of Christian time scales and intrusive Habsburg events, the Indigenous calendar was just one of the alternate calendar time scales that operated within Habsburg domains, as we have seen with the invocations of judiciary astrology to explain the Indigenous calendar. In the first part of this essay, we saw how urban space offered a way to orient human activity and layer meanings through spatial coincidence; in offering attractive spaces for Habsburg rituals, the Mexica city also colored their meaning. Calendars offered a way of coordinating human action in the world, as well, but alternate calendars were threatening. Some, like the Indigenous calendar, synchronized human activities to a sequence—beginning with the creation of the earth by the deities Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca—that bore little relation to a Christian cosmology. As a result, Indigenous books that contained the calendar were the target of one well-known 1562 auto-da-fé organized by Bishop Diego de Landa in the city of Maní, in the Yucatan peninsula. Here, he burned Indigenous calendrical books, along with sculptures he took to be idols.Footnote 62

But it was not just Indigenous time-scale calendars that were suspect in the era, and the widening target is signaled by the page in the Codex Aubin that depicts the bundling of the year in 1559, described above, on which a second artist added a bundled reed symbol to compensate for a lack in the main symbol (see figs. 9, 20, and 21). But the scribe, adding the texts subsequently, misread the symbol of the calendrical book. Instead of recognizing that it was attached to the symbol of reeds, to denote 2 Reed/Ome Acatl, the scribe thought these were tongues of fire. The scribe added an annotation in Nahuatl to read “17 March: the books were burned.”Footnote 63 (Realizing the mistake, a third writer tried to correct this misreading, squeezing in another image with text that not only identifies the tying up of “our years” but also specifies that this is the eighth cycle—that is, 416 years—since the exodus from Aztlan, and writes, “Now our years were tied, tied for the eighth time” [see fig. 9]).Footnote 64

The principal scribe's misreading of the event of the 2 Reed/Ome Acatl year as a book burning can be interpreted against a number of horizons. The first, most local, was the campaign of the local archbishop of Mexico, Alonso de Montúfar, a Dominican, against books published by Franciscans that were suspect because of the Erasmian leanings of one author (Juan de Zumárraga), or the use of native languages by others.Footnote 65 While both entailed the seizure of books, neither seem to have led to book burnings, which, other than Landa's conflagration, were quite rare in New Spain.Footnote 66 Set against a European horizon, the year 2 Reed/Ome Acatl coincided with the publication of two indexes of prohibited books, one issued by the Spanish Inquisition, and therefore deployed in New Spain, and the other issued by the Roman Inquisition. While the Roman Inquisition had been attempting to control the circulation of books perceived to be heretical, and in 1553 mandated that the Talmud be burned,Footnote 67 this particular list of 1559 was notable for its extensiveness and its broad codification.Footnote 68 Rushing the book off the press, the compositors paid little attention to uniform typefaces; its organization reflects the still loose standardization in the book trade—some authors are listed by first name, some banned books appear as titles alone, others are banned by virtue of their publisher. This hastily produced bookgifted Inquisitors and royal bureaucrats alike with the power to quickly identify heretical books. Once seized from publishers or booksellers, books deemed heretical were more likely to be burned in Europe as part of urban public rituals than in New Spain. Indeed, while Landa's auto-da-fé is notorious, it does not seem to have been widely repeated in New Spain, and Landa himself was recalled back to Spain because of the excesses of his zeal.Footnote 69

Included on both Valladolid and Roman lists were those alternate calendar time scales that had enjoyed great popularity in Europe—that is, works of judiciary astrology, used to cast horoscopes. The Roman list, for instance, includes the Tractatus Astrologicus by the popular astrologer Luca Gaurico, a favorite of Pope Paul III.Footnote 70 If the function of calendar time scales is to allow for “an active synchronization of their own communal activities with other changes in the universe,”Footnote 71 at issue for the Inquisition was not the nonhuman time scale used by astrologers (the position of the stars). Rather, it was the synchronizing function drawn between sidereal positions and human activity, as astrologers sought to determine the effect, both in the past and in the future, of the position of stars and other astral bodies on human lives. While the complex history of judiciary astrology is beyond the scope of this essay, suffice it to say that at times judiciary astrology was embraced by the church: in the early part of the sixteenth century, it was used by Pope Paul III to determine an auspicious time for laying the foundation of the new St. Peter's Basilica.Footnote 72 But even in the late fifteenth century, opposition to this and other forms of prognostication was coalescing. Barbara Mahlmann-Bauer summarizes the views of its opponents, which included Giovanni Pico della Miradola and Girolamo Savonarola: “the assumption of sidereal necessity threatened God's omnipotence and providence, as well as human freedom of action.”Footnote 73

The shifting currents around judiciary astrology are no better revealed than in book 4 of the Florentine Codex, which treats the Indigenous time-scale calendar of 260 days, the tonalpohualli, used to augur fates. The title page of the book equates it to judiciary astrology, and within the Nahuatl text, its Nahuatl authors write positively about the calendar itself.Footnote 74 But in 1576, during the late stages of the book's redaction, when Franciscan policies were under attack and the Florentine Codex was faced with seizure (it eventually was seized), Sahagún added an appendix to book 4, writing only in Spanish.Footnote 75 In it, he both reproduced, and then denounced, the writings of an earlier Franciscan, Toribio de Benavente (also known as Motolínia), on the calendar. Although Sahagún defended judiciary astrology as being based on observation of the “natural” (that is, divinely created world), he used this appendix to reject native calendars as “an artifice made by the devil himself.”Footnote 76 The split in rhetoric within the book suggests that while Indigenous intellectuals may have cultivated the native calendar as being similar to judiciary astrology in both the Florentine Codex and the Codex Aubin, Sahagún's expressed attitudes were changing, perhaps in response to the growing royal censure of his project.

A related widening of prohibitions against alternate calendar time scales is reflected in the 1559 edition of the Roman Index held today at the Library of Congress. Its original owner and provenance are unknown, but at least one sixteenth-century custodian of the book revealed an intense engagement with its contents, suggesting that this was a working manual of an inquisitor: each page has been heavily annotated in Latin, principally to cross-index first names and last names of authors, and authors and titles. Its custodian added more and more entries reflecting the number of books added to the list, including books published in 1580, suggesting that he (or less likely, she) needed this manual as a working document. And this custodian seems also to have continued to track the expanding number of prohibited books through the 1580s. Bound with the book today is a single-sheet papal bull issued in 1586, contemporaneous with the last entries in the book. Printed on heavy stock paper, it is titled Constitutio S. D. N. D. Sixti Papae Quinti contra Exercentes Astrologiae Iudiciariae Artem (Ruling of our holy lord, the lord Pope Sixtus V against practitioners of the arts of judicial astrology)—the definitive sanction against books on judiciary astrology and its practice.Footnote 77 The book literalizes the shifts over the second half of the sixteenth century: backing away from the possibility of human beings foreseeing the future because of their ability to read the signs of nature, the Catholic Church asserted that it was only God who possessed such foresight. Human events followed an order of time that was singular, and unpredictable to any other being but the divine.

CONCLUSION

This essay has set out how Habsburg monarchs established their legitimacy among the large urban Indigenous population of Mexico-Tenochtitlan. I've grappled with a problem that the historian Teófilo F. Ruiz has pointed out: while the messages that local cabildos meant to convey about their loyalty to the monarchy through the festival were clear to their members, how they were received has always been difficult to discern, dependent on “archival data and ‘counter’ propaganda.”Footnote 78 In tracing the Habsburg festival in Mexico City, where events and processions occurred in spaces both designed for and previously consecrated by the acts of Mexica rulers, I have argued that the spatial valences of the city exerted their own legitimizing force. But perhaps the most effective vehicles for legitimizing the Habsburg monarchs were the new calendrical time scales their festivals introduced, by which urban life was recalibrated around the life events of the monarch and his family. In the Americas, the imposition of Habsburg time depended on both soft power (the invitation to the urban festival) and strong-arm tactics (the seizure and destruction of calendrical books recording different orders of time). In addition, the manuscripts examined within this essay—particularly the Codex Aubin and the Florentine Codex—show us the growing intolerance toward other modes of orientation provided by alternative calendar time scales, on both sides of the Atlantic. This suggests that Habsburg time was more easily implanted because of the foreclosure of other alternatives.

The royal cédula with which this essay began no longer exists, but its effects can still be felt. Produced in multiple, it called for the celebration of a Habsburg life event in cities across the realm, thereby orienting the lives of urban residents to a distant, and insistent, centralized chronometer. It thereby constructed and naturalized the relationship of a European center to an American periphery, one that also undergirded an emergent political and economic hierarchy, with a distant European king sustained by the productive labor of his subjects. Taking a broad view of the processes of colonization reveals that one of its features, beyond the threat of violence, was its intervention into the fundamental ways that human societies oriented themselves in time. Such an awareness, in turn, calls for more attention to the role of time scales in the processes of cultural domination, and the cultural disordering that their erasure causes.