In the spring of 1790, the naturalist Georg Forster, accompanied by the young Alexander von Humboldt, visited the celebrated range of natural history collections in London.Footnote 1 A main calling point was the library of the president of the Royal Society, Sir Joseph Banks, at 32 Soho Square, a meeting place for natural historians from across Europe.Footnote 2 Although Humboldt held good relations with Banks, Forster was less complimentary. In his published report of this journey, a work designed to draw attention to the political changes taking place across Europe,Footnote 3 Forster was scathing about Banks's natural history collection and British science. Forster commented that ‘Everything is in bad shape except for botany’, describing how there is ‘absolutely no understanding [Kenntniß]’ of natural history; implying the superficiality of Banks's expertise.Footnote 4 This correlated with Forster's impression of political stagnation in Britain, for he believed that political reform went hand in hand with advancements in natural history.

While there is a large literature on book production during the French Revolution, this concentrates on France and the effect of the Revolution on commercial book and newspaper production in Paris.Footnote 5 Many of these more general studies of the book trade have overlooked the field of natural history, a major part of which revolved around the production and distribution of expensive volumes compiled from text and copperplate illustrations designed to provide a systematic classification for species.Footnote 6 These systems took on new meanings during the Revolution. The 1780s had witnessed the birth of natural systems of classification, developed by the French botanists Antoine de Jussieu and Michel Adanson, which classified plants according to their general physiology and strived to map a continuous natural order between species, ideas which emanated from Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon.Footnote 7 This broke down the artificial hierarchic divisions of kingdoms, classes, orders, and genera that had been imposed on nature by the system developed by Carl Linnaeus from the 1730s which had dominated British natural history since the 1760s.Footnote 8 By the 1790s, natural systems were often associated with the erosion of aristocratic social hierarchies, championing the aims of French Jacobins.Footnote 9 This connection to revolutionary politics impacted the practice of natural history in Britain, where, unlike many European absolutisms or Revolutionary France, scientific practice remained decentralized and in the hands of a few self-funded practitioners. These included John Stuart, the earl of Bute; Sir William Hamilton; Edward Smith-Stanley, the earl of Derby; and Sir Joseph Banks, who used their powerful positions to patronize and practise natural history to extend their personal agendas.Footnote 10 In the light of political connotations attached to different systems of classification, it is also of crucial interest to determine how partisan views influenced the construction, production, and distribution of a natural history book during the revolutionary age.

Since Linnaeus's death in the late 1770s, there had been an upsurge in natural history publications reflecting the multitude of new species entering Europe.Footnote 11 Descriptions and specimens of new species were obtained from more frequent state-sponsored voyages of discovery, the most notable being those from France, Britain, and Russia commanded by Louis Antoine de Bougainville, James Cook, and Adam Johann von Krusenstern.Footnote 12 Cook's three Pacific voyages were the main source of this material entering Britain. Banks had been involved with these expeditions from his initial appointment as a self-funded naturalist on Cook's first voyage in 1768 and maintained a particular interest in the second and third voyages, becoming a kind of state-approved, although autonomous, custodian and adviser for the numerous natural history materials gathered during these expeditions.Footnote 13 From the mid-1770s, Banks mobilized his great wealth, derived from country estates that brought him an annual income of £16,000 by 1820, to build a vast natural history collection at his London mansion in Soho Square.Footnote 14 Banks's election to the presidency of the Royal Society in 1778 and baronetcy in 1783 swiftly gained him a sustained level of political power and influence.Footnote 15

While Banks was climbing the social ladder, the specimens and information collected during Pacific voyages stimulated ideas which threatened to undermine the fabric of European society. Amongst these was the perceived beauty of the South Seas islands, especially Tahiti, the charm of its peoples, and descriptions of the slight economic and social differences between the rulers and the ruled in Tahitian society.Footnote 16 In Britain, this bore a strong relation to the criticism of Anglican ethics by figures such as Erasmus Darwin who related the use of sexual organs to classify plants according to the Linnaean system to idealized views of Tahitians as naturalized beings who lived in a society free from the constraints of Christian doctrine.Footnote 17 Darwin's use of the botany of the South Seas to criticize established social and taxonomic hierarchies shows how the vision of an egalitarian society challenged the authority of the Linnaean system and the aristocratic system of government.Footnote 18 These revolutionary connotations were almost certainly connected to Banks's Pacific collection and influenced his approach to its publication.

Icones plantarum (c. 1800) was commissioned by Banks and made up from 129 expensive copperplate images of plants engraved in the 1790s and based on the botanical illustrations Georg Forster produced during Cook's second voyage to the Pacific between 1772 and 1775 that Banks had purchased for £420.Footnote 19 These surviving copperplates, a new discovery in terms of the vast Banks collections, were privately funded by Banks and engraved by Daniel Mackenzie (c. 1770–1800) in the room under the library at 32 Soho Square. Forster's illustrations were embroiled in revolutionary politics from the early 1790s. Forster's support for the Revolution, the threats this posed to established European social structures, and the Linnaean system intertwined the Pacific origins of these images with the general breakdown of society. As a result, Banks employed several important taxonomic strategies during the production of Icones plantarum and managed its distribution, enforcing a certain level of censorship over materials obtained from the South Seas. Although the effects of the Revolution on the movement of printed scientific material across European borders has received attention,Footnote 20 Icones plantarum shows how it shaped the decisions behind the production, interpretation, and distribution of a natural history book. By examining the case of Icones plantarum, this article reveals how independent British gentlemen-naturalists, such as Banks, intertwined their personal agendas with the production and distribution of an expensive copperplate publication, integrating scientific practice with political loyalism and the workings of a counter-revolutionary state.Footnote 21

With this in mind, this article surveys Forster's and Banks's divergent views on the French Revolution during the early 1790s and how this affected their standing in philosophical circles across Europe. It then moves onto Banks's management of the processes behind the production of the 129 copperplate engravings after Forster's death in 1794. The final section examines the problems behind publishing and distributing a work on the flora of the South Seas and how the Revolution shaped Banks's definition of intellectual property and means for distributing knowledge.

I

The time Georg Forster spent in the Pacific and his observations of the relative equality between the three main social classes of Tahitian society set the seeds for his views on general social reform in Europe and later revolutionary writings.Footnote 22 Forster cautiously admired the level of equality in Tahitian society and believed this was essential for inspiring general harmony and a carefree, utopian lifestyle.Footnote 23 After their return to Britain, Georg and his father, Johann Reinhold Forster, found it difficult to extract the £4,000 they deemed due to them from the Admiralty for their participation in the voyage. This resulted in Georg Forster's publication of A letter to the right honourable earl of Sandwich (1778), a bitter complaint against their treatment by the Admiralty.Footnote 24 This public accusation inspired criticism of the Forsters. Sandwich exclaimed in a letter to Daines Barrington that ‘Soon after I became acquainted with Dr. Forster I found he was a person who could not keep a friend for any length of time.’Footnote 25 Johann Reinhold Forster's attitude was confirmed by the Warrington naturalist Anna Blackburne, who commented in a letter to the naturalist and traveller Thomas Pennant that ‘I am very sure if Doct. Forster has done any thing uncivil towards you he is highly to blame.’Footnote 26 The Forsters also clashed with William Wales, the astronomer on the Resolution, over the amount due to them from the Admiralty which was far more than that received by the other scientists.Footnote 27 Wales withheld vital geographical information from Georg Forster when he was preparing A voyage round the world (1777) and accused him of plagiarizing the research of others.Footnote 28

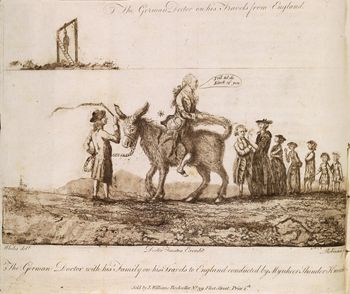

These conflicts culminated in the publication of a cartoon depicting Johann Reinhold Forster going through the public humiliation of parading on a donkey followed by his family, a ridicule traditionally reserved for husbands dominated by their wives (Figure 1). The original illustration has been attributed to ‘Whales’, probably William Wales, in addition to being printed by ‘Doctor Faustus’ referring to legends based on the fifteenth-century scholar Johann Faustus, who was associated with the plagiarism and theft of the original invention of the printing press.Footnote 29 This suggests that Forster had surrendered his moral integrity to obtain power and wealth. In 1778, Georg Forster returned to the German States and by 1790 was studying the relationship between plants and society with Alexander von Humboldt.Footnote 30 A result of consistent problems with securing payments from hierarchic European courts, Georg Forster began to see the egalitarian society he had experienced on Tahiti as a model.Footnote 31

Fig. 1. A cartoon which ridicules Johann Reinhold Forster and his family entitled ‘The German Doctor with his Family on his Travels to England conducted by Mynheer Shinder-Knecht’, c. 1775. Georg Forster is presented immediately after the donkey in this image. Supplied by Llyfrgell Genedlaethd Cymru / National Library of Wales.

A decade after he left England, Georg Forster accepted the position of director of the library of the elector of Mainz in April 1788.Footnote 32 Forster openly supported the French Revolution and became immersed in revolutionary politics after the principality of Mainz was occupied by the French army in 1792. He described this event as ‘when the French began to free the world from its tyrants’ in a speech before the Mainz Jacobin club on 15 November 1792.Footnote 33 In March 1793, Forster was sent to Paris to lay a request to unify Mainz and France before the French National Assembly. Forster's activities were viewed as little more than high treason by many European philosophers. Among these were Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, with whom Forster had edited the Göttingishes Magazin, and the Prussian statesman Wilhelm von Humboldt. Writing in December 1792, Humboldt exclaimed that ‘I can't forgive Forster for having at this moment and so openly, gone over to the French party…It strikes me as immoral and ignoble to the highest degree.’ The poet, philosopher, and physician Friederich Schiller wrote that ‘Forster's conduct will certainly be criticized by everyone, and I can see in advance that he will derive shame and regret out of this business.’Footnote 34 Forster differed in his beliefs from many of his contemporaries. He maintained that the Revolution was an unavoidable natural cycle and force of nature designed to erode the gulfs between European hierarchies and inspire a state of social and economic harmony similar to that in Tahiti.Footnote 35

In mid-1793, the counter-revolutionary powers reoccupied Mainz, leaving Forster in a state of exile in Paris. Forster came close to being guillotined after Adam Lux, a fellow member of the delegation responsible for uniting Mainz with the French Republic, was executed for circulating a pamphlet in support of Charlotte Corday, the Girondin assassin of Jean Paul Marat.Footnote 36 In spite of this, Forster maintained his revolutionary beliefs, commenting that the execution of Louis XVI was part of a natural progression, a position that earned him widespread criticism from philosophers.Footnote 37 However, in much of Europe (with the exception of France) natural history and the systems of ordering and classification it entailed had become integral to the counter-revolution.Footnote 38 Figures such as Banks saw Forster's ideas as direct threats to their own positions in society, heralding the collapse of governmental systems and the order of nature itself.Footnote 39 Shortly before his death, Forster witnessed the foundation of a national system of botanical gardens and museums across France, proving that the Revolution was responsible for distributing natural-historical and agricultural knowledge to the masses and improving society.Footnote 40 A result of the rejection of Forster by the majority of European intellectuals, he was distanced from correspondents in Britain and Germany. In a letter sent to his wife, Therese, on 21 August 1793, Forster exclaimed that:

I have no home, no fatherland, no kinsfolk anymore; everyone who was otherwise attached to me has gone on to form other connections…Had I been willing to act contrary to my convictions and feelings, I might now be a member of the Academy at Berlin, with a handsome salary.Footnote 41

In a similar manner to Forster, Banks developed his views on social freedoms and the Revolution when he arrived in Tahiti in 1769. However, Banks left with a very different interpretation to that of Forster who, while he appreciated Tahitian society for its social harmony, remained critical of its hierarchy. In comparison, Banks appreciated Tahitian society for its hierarchical structure. Shortly after he landed, Banks was eager to find the rulers of the island, likening the scene before him to ‘the truest picture of an Arcadia of which we were going to be kings’.Footnote 42 Banks formulated this view after he found that the people who greeted him were ‘only of the common sort’, believing his social status as a prominent English landowner gave him the right to preside over this utopian society as a kind of monarch.Footnote 43 After his return from the South Seas and rapid social elevation, Banks built a ‘learned empire’ of naturalists and by the 1790s he was commonly referred to as a ‘monarch’ of natural history. Banks's prominent position was not only threatened by but inspired his vehement opposition to the Revolution.Footnote 44

A major concern Banks and his correspondents had with the developments in continental politics was the slowing of progress in the sciences. This was expressed to Banks in 1788 by the French traveller and geologist Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond, who commented in a letter dated 18 May, just after the initial demands by the Paris parlement to call the Estates General, that ‘The malady of politics, which is becoming an epidemic in Europe and is starting to take hold of us too, will also affect the sciences with which it has little to do.’Footnote 45 By 1791, the abbot and botanist Pierre André Pourret commented that the Revolution had ‘overturned my fortune and my hopes in quick succession, had deprived me of the means of corresponding with people who honoured me with their kindness’.Footnote 46 In his response, sent shortly after the disillusion of the French Legislative Assembly, Banks offered Pourret sanctuary in Britain, commenting that France was descending ‘into troubles which She will not Extricate herself from without bloodshed during the terrible Calamity if it should befall you a peaceable & scientific return with us Could not fail to be agreeable with you’.Footnote 47 However, Pouret emigrated to Spain where he remained until his death in 1818.

Banks's home at 32 Soho Square soon became a haven for French émigrés from the 1790s. When he visited Banks in 1805, the American chemist Benjamin Silliman described how ‘I may not perhaps make so much use of the breakfasts as a French loyalist is said to have done’, adding that ‘this man having fled from the guillotine in France, found access at Sir Joseph Banks's, and met that liberal reception which is known to characterize the house’.Footnote 48 The emigration of European natural historians and philosophers to London and their congregation at Banks's home increased his deep fear and hatred of the Revolution. This was solidified by first-hand accounts of the executions of several French philosophers.Footnote 49 For example, in a letter sent in 1792, Banks's friend and secretary of the Royal Society, Sir Charles Blagden, described his departure from Paris:

two of our carriages, of which mine was one, being a little behind the other as we went from Paris, the mob rose upon us, threatened to hang us, to tear the children in pieces, & really appeared so perfectly mad that it was impossible to say what violence they might commit.Footnote 50

These early reports of the Terror generated absolute fear in the hearts of many British aristocrats and were exacerbated by political events in Britain. Banks described to the Neapolitan ambassador, William Hamilton, how ‘We are here in some sort of terror from the active pains those who wish for a scramble are taking to raise the lower orders into a wish for Equality’, a reference to radicals such as the chemist and preacher Joseph Priestley.Footnote 51

The combination of revolutionary ideals, a French invasion, and a potential revolt of the English lower classes caused Banks, as one of the most prominent landlords in Lincolnshire, significant concern. When Banks held the office of high sheriff of Lincolnshire in 1794, he published a pamphlet entitled Outlines of a plan of defence against a French invasion intended for the county of Lincoln and expressed that ‘the probability of the French very soon invading this island, with a force infinitely superior to that at present provided for its defence, is very great’.Footnote 52 This pamphlet presents an unusual foray into publishing in the public sphere for Banks, who wished to make his views on the Revolution and the threat posed by a French invasion known to the ‘gentlemen, yeomanry and farmers’ of Lincolnshire. Banks believed this sector of society had the power to reform the domestic military, put ‘his native county in a state of defence’, and ‘defend it from the whole French army’.Footnote 53 This widely distributed pamphlet, in which Banks presented an enumeration of the men available to defend the county and a breakdown of the annual expenditure for maintaining troops, ensured that Banks's views were well known, placing his support behind William Pitt's government and strengthening his position at court.

By disrupting Banks's international patronage and correspondence networks, the Revolution hindered his regime at the Royal Society and natural historical programme. By 1798, the Dutch lawyer and politician Pieter Hieronymus van Westrenen (1768–1845) explained to Banks that another correspondent did not forward books and letters because ‘he deared not Send them to me, fearing they wood be taken in the passage [sic]’.Footnote 54 Banks repeated these views in a letter to the Austrian physician Nicolaus Thomas Host in 1812; ‘I have not for Some years Received any thing from Germany, the French permit us to have Some but not many books from France but they Effectually prevent all Literary intercourse with Germany.’Footnote 55 These comments reflect the disruption in the book trade, which Jonathan Topham has shown to have slowed the import of publications from the German States more than those from France.Footnote 56 Book exchange was central to Banks's means for integrating himself with continental European naturalists and its hindrance slowed the communication of natural knowledge and reduced Banks's authority.

II

Georg Forster's death in January 1794 was a major incentive for Banks to produce Icones plantarum; 129 plates based on the botanical illustrations Banks had purchased from Forster in 1776 and engraved during the mid-1790s by Banks's live-in engraver, Daniel Mackenzie (d. 1799/1800).Footnote 57 By producing this great work after Forster's death, Banks distanced it from any association with the latter's revolutionary ideals. This section shows how the Revolution shaped the production of Icones plantarum, from acquiring the physical materials to natural-historical practices employed when producing the plates. The 129 engravings were produced on sixty-five double-sided copperplates, one of which was engraved on the verso of the last plate from Banks's book on Japanese plants, Icones selectæ plantarum (1791).Footnote 58 It seems these plates were purchased and engraved after 1791 to form a continuation from Banks's previous work.

Perhaps the most obvious impact of the war and Revolution on Banks's natural history work exhibited through the case of the plates for Icones plantarum was the rise in costs associated with materials. For example, the copperplates for Icones plantarum were engraved on both sides, thereby halving the expenditure on the copper. Banks previously paid Mackenzie four guineas per engraving for William Aiton's Delineations of exotick plants (1796), a price that did not take the initial costs of the copper sheets into account.Footnote 59 Mackenzie probably received a similar rate to engrave Forster's illustrations which would have totalled approximately £541. Reducing the expenditure on the copper was essential given that the Revolutionary Wars caused the price of raw copper to almost double from 1788 to 1799. This escalation led to a parliamentary inquiry in 1799.Footnote 60 The Birmingham industrialist Matthew Boulton, a friend of Banks with particular interests in copper manufacturing, became markedly hostile towards the Revolution due to the problems it posed for sourcing materials.Footnote 61 In 1801, the British government abolished the duties on copper destined for domestic markets to reduce the price for objects such as printing plates. In spite of this, copper remained expensive until the fall of Napoleon in 1815.

The high price of copper was coupled with a government duty on paper. In 1803, this cost three pence for every pound in weight of printing paper, adding to the total outlay on production for every publication.Footnote 62 These additional expenses are reflected in Banks's comments to William Roxburgh in 1796: ‘just now no Books can sell on account of the pressure of Taxes & voluntary contributions’.Footnote 63 By the mid-1790s, the entire domestic economy was set against the production and publication of large natural history images. Problems with the production processes combined with the steep increase in copper prices made Icones plantarum expensive to produce. These problems were apparent throughout Europe. In a letter sent to Banks in 1798, van Westrenen commented ‘Times of wars and revolutions are not favourable to literary productions, it makes that few books are coming out worth of any notice.’Footnote 64

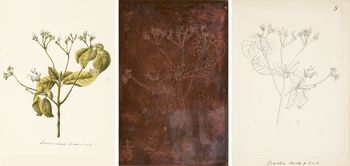

Many of the plates engraved for Icones plantarum depict plants Forster collected and illustrated on the shores of the islands of the Pacific, such as Tahiti, which he visited between 17 August and 16 September 1773. A typical example is a species Forster ascribed the binomial Dianthera clavata Forst., of which he produced a pen and ink illustration that was later painted over in watercolour. The main purpose of the illustration was to preserve vestiges of the plant's original physical structure before Forster placed it in paper wrappings to dry it for his herbarium (Figure 2). Forster's image of Dianthera clavata was located towards the front of the illustrations Banks purchased and then had ordered and bound according to the Linnaean system. The Linnaean approach to ordering species revolved around detailed instructions for the classification and depiction of plants which Linnaeus had initially laid out in Critica botanica (1737) and reaffirmed in Philosophia botanica (1751). Linnaeus emphasized the importance of ensuring that published illustrations were produced to the same scale as the living plant, omitting features which varied between different specimens of the same species, such as colour.Footnote 65 Linnaeus also stated that the flowers and fruit, which contained essential taxonomic properties used to define the genus and species according to his system, had to be represented.Footnote 66 Forster also applied colour and shadow to the leaves, conventions used to situate an observation in a particular time or locality.Footnote 67 However, Forster only employed this practice sparingly, as described by Daniel Solander shortly after Banks purchased these illustrations; ‘the Drawings of Plants [are] Mere sketches, not one has a grain of colour laid in’.Footnote 68

Fig. 2. (Left) The illustration of Dianthera clavata Forster produced in 1773. (Centre) The copperplate engraved by Daniel Mackenzie based on Forster's illustration, produced between c. 1794 and 1800 (31.9 × 21.6cm). (Right) The original impression taken from the copperplate. The annotations are in the hand of Jonas Dryander, Banks's librarian from 1782 to 1810. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

When it came to producing the copperplates for Forster's illustrations in the 1790s, Banks went to great lengths to erase features which held their basis in a particular specimen or observation. For example, the plate produced for Dianthera clavata has several marked differences when compared with the original illustration (Figure 2).Footnote 69 The most noticeable is Mackenzie's removal of shadows and colour from the engraving, an omission he applied to standardize all of the 129 images produced for Icones plantarum. This produced a series of archetypal images that avoided features particular to any single member of a species.Footnote 70 These standardized images were of particular importance to botanists in the 1790s as the emphasis of particular physical features conveyed the relevant taxonomic properties of a plant and reduced synonymy.Footnote 71 In both Forster's image and the copperplate engraving, the flowers of Dianthera clavata have been illustrated in detail. Properties such as the single stigma and two stamens in the flowers, essential features for ascribing this species a Linnaean class and order, are easily identifiable and secure the placement of this species within the Linnaean hierarchy.

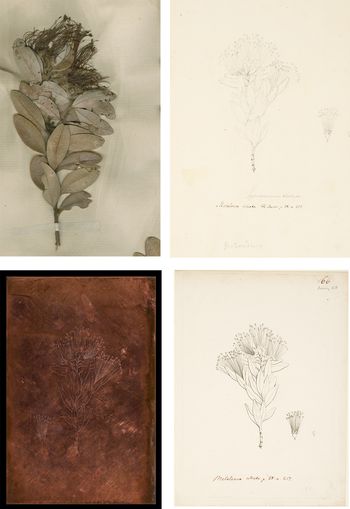

Throughout his career, Banks emphasized the importance of images over textual descriptions for communicating information. In 1789, he commended the Scottish explorer of Ethiopia, James Bruce, for publishing images without descriptions as botanists could ‘learn from them without any assistance’.Footnote 72 To ensure that the images published in Icones plantarum communicated accurate information on the physical structure of a species, Banks was careful to conform to the rules stipulated by Linnaeus. A major point Linnaeus stressed in Philosophia botanica was that images of plants ‘should be drawn in the natural size and position’, going on to comment that ‘The ancients’ pictures present the tallest trees and the smallest Alsines as of the same size…this should be carefully avoided.’Footnote 73 This represents a significant change in standards of botanical illustration. For instance, in Robert Morison's Plantarum historiae universalis Oxoniensis (1672–99), illustrations of multiple species were often crammed onto the plates and reduced in size to cut costs. This resulted in many plant species being difficult to identify from the illustrations and they bore little resemblance to Morison's herbarium specimens.Footnote 74 In contrast, many of the images Banks purchased from Forster resemble a set of herbarium specimens Johann Reinhold Forster gifted to Banks in 1775.Footnote 75 Amongst these, Forster listed a species he collected in New Caledonia and named Leptospermum ciliatum, the original specimen of which continues to share similarities with the finished engraving (Figure 3).Footnote 76

Fig. 3. An example of the similarities between the specimen Forster collected, the original drawing, copper plate, and copper plate impression for the species Forster ascribed the name Melaleuca ciliata in Flora Australis (1786), now re-named to Purpureostemon ciliates (G. Forst.) Gugerli. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

A typical pencil sketch Forster produced on Cook's second voyage depicts Thalia cannæformis Forst., one of two new species Forster and the Swedish naturalist Anders Sparrman collected in the Vanuatu archipelago on 22 July 1774.Footnote 77 The size of this illustration presented problems for Banks and his engraver, Daniel Mackenzie, when transferring these images onto copperplates during the 1790s. Banks intended to comply with the rules in Philosophia botanica, although a major difficulty was posed by the sizes of the available copperplates. Throughout his career, Banks purchased copper printing plates from a company founded by Richard Jones based in Shoe Lane, that had been taken over by William Pontifex after Jones's death in 1788. Banks's consistent purchases from Jones & Pontifex in the 1780s and 1790s are represented by the trade cards and copperplate receipts Banks's sister, Sarah Sophia Banks, collected over the period when her brother had contact with the firm.Footnote 78 The large copperplates Jones supplied for the images of plants produced on the Endeavour voyage were the same size as the larger plates used to engrave Forster's illustrations.Footnote 79 The smaller plates used for Forster's botanical drawings are 50 per cent of the size of the larger plates.Footnote 80 It seems the largest plates Jones & Pontifex supplied to private buyers were somewhat shorter and narrower than Forster's original illustration of Thalia cannæfornis.

The size difference between Forster's drawing and the available copperplate meant the image had to be adapted when it was engraved. Rather than reducing it in size, a common practice before the Linnaean reforms of the mid-eighteenth century, Banks and Mackenzie chose to create an incision in the image of the specimen itself. This is apparent at the base of the stalk where Mackenzie severed the branch containing the leaves from that which bears the flowers and fruits (Figure 4).Footnote 81 The splitting of Forster's image ensured the major constituent parts conformed to the Linnaean description of Thalia cannæfornis and were not reduced in size. Rather, they were moved around to accommodate the size of the copperplate. The branch that bears the flower and fruit was then superimposed over that which depicts the leaves. This was a common practice of late eighteenth-century botanical illustration and is apparent in publications such as William Curtis's Botanical Magazine and reflects the manner Banks expected botanists to interpret the printed image. According to the Linnaean system, the sexual organs were of paramount importance for constructing a diagnosis for a species, which started with the calyx and then moved onto the corona, stamens, pistils, and fruit before ending with the seeds.Footnote 82 Of the next level of importance were the number, shape, and position of parts such as the leaves.Footnote 83 The secondary importance of the leaves influenced the decision to obscure them with the more important characters.

Fig. 4. (Left) Forster's illustration of the species Thalia cannæfornis Forst. (48.7 × 34.8cm). (Centre) the copper plate engraved by Daniel Mackenzie (d. c. 1800) (46.4 × 30cm). (Right) The copperplate impression for Thalia cannæfornis Forst., the first in the series Banks had produced for Icones plantarum. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

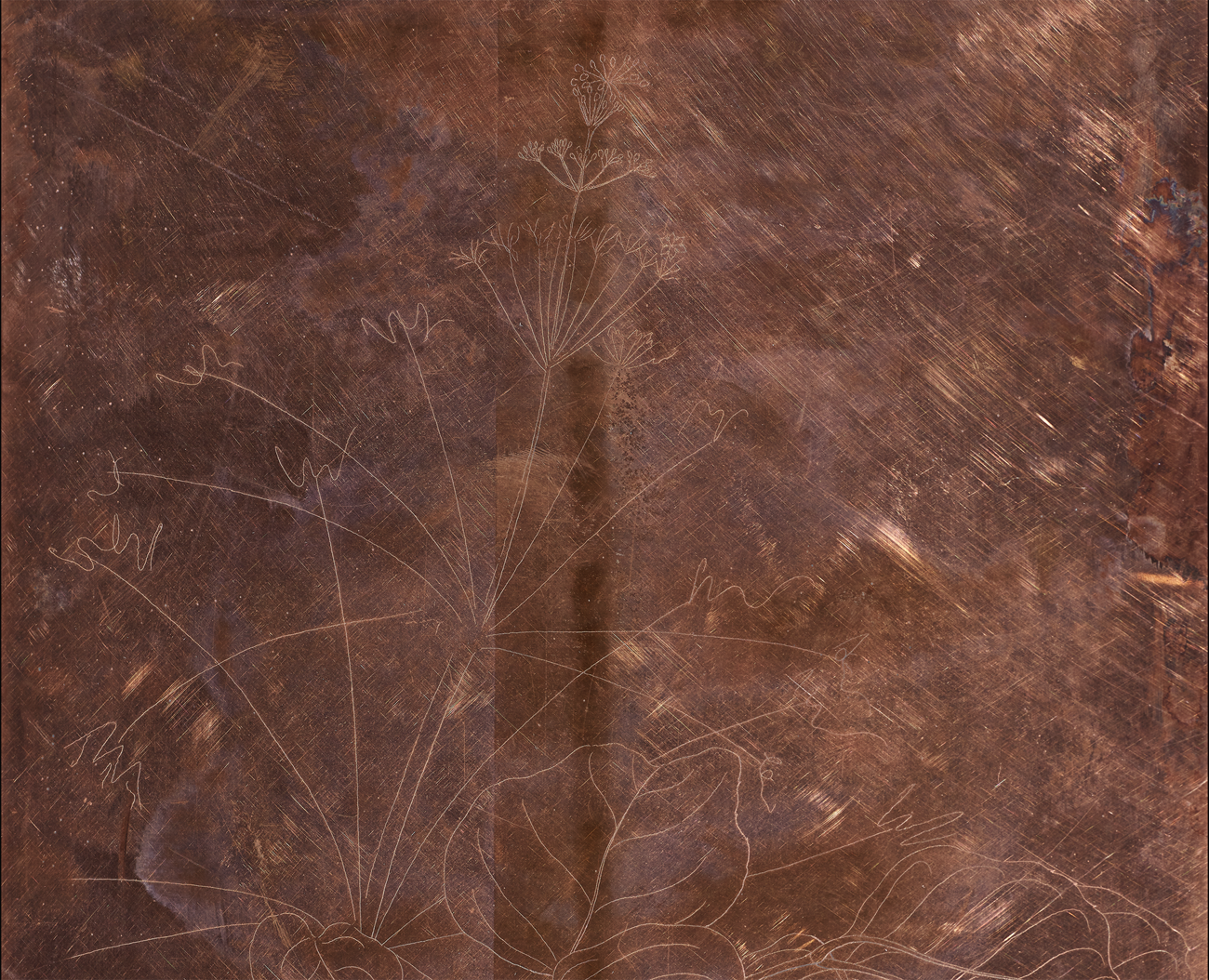

Mackenzie's death around 1800 resulted in the last of these plates remaining incomplete. An example can be found in the case of plate 126 that depicts the species Ployscias pinnata G. Forst., on which Mackenzie has not finished engraving the flowers and fruits, leaving etched outlines which he intended to go over with a burin at a later date (Figure 5). The combination of the death of the engraver and the problems caused by the war contributed to the incompletion of Forster's Icones plantarum, although this was not the only factor which influenced the extraordinarily limited distribution of this work.

Fig. 5. The detail from the unfinished plate 126 based on Forster's illustration of Ployscias pinnata G. Forst. On the left are the roughly etched lines which form a preparatory guide for Mackenzie to engrave over with a burin. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

III

After Banks purchased the natural history illustrations from Forster, the relationship between these naturalists had been fraught. This becomes apparent from a letter Forster received from Sparrman on 15 September 1776:

What did Mr. Banks pay you for your Drawings and the other things he got? I would not make an offer of any thing to this gentleman if he does not make first advances and proposals, and than he would get nothing but duplicates…For my part however, I would prefer to send somebody less avaricious of collections and the merit of them than he is.Footnote 84

Banks believed that anything in his personal possession remained his private property and after he had purchased these illustrations Forster lost all rights to their further use. Banks expressed this view in 1782 after Forster proposed to publish several zoological prints based on illustrations he had sold to Banks in 1776. Banks commented that Forster's ‘Spicilegia’, a publication designed to form a series of miscellaneous images of plants and animals encountered in the Pacific,

Contain some Drawings which were or ought to have been included in my purchase: you will not wonder if I am a little jealous of that for which I pay'd as I thought a generous price: of course you will not be surprised at any steps which I may take in consequence of such publication.Footnote 85

These problems with copyright resurfaced again in 1785 when Forster published several plates that he had received from the Admiralty which related to the account of Cook's last voyage.Footnote 86

Banks saw Forster's attempts to publish material from his collection without consent as an attack on fundamental concepts of personal property. Britain had just finished fighting the American Revolutionary War, which had been concluded with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. As Adrian Johns has suggested, the piracy of printed books was a major sign of defiance and insurrection that the American Revolutionaries used against British forces in the New World.Footnote 87 Another centre for pirated publications was Dublin, where print and booksellers consistently disregarded the copyright provisions laid down by the statute of Queen Anne in 1710.Footnote 88 Ireland, like North America, was seen as a hive of insurrection by the 1790s. The Irish Rebellion of 1798 drew many ideals from the revolutions in Europe and North America and culminated in the Act of Union of 1800, which decimated the Irish re-printing industry.Footnote 89 As a result, Banks presumably saw Forster's publication of materials without his permission as an act of defiance and insurrection against the British Admiralty and his own authority. Forster's actions associated aspects of Banks's collection and the broader practice of natural history with the undermining of the established social order.

A continual concern with copyright and the association of commercial publishing with political insurrection reinforced Banks's views that natural history books should be reserved for a select audience who would benefit from the information they contained. For Banks, a prominent English landowner by the 1790s, this practice continued an aristocratic gift economy that had emerged in the sixteenth century and mirrored the approaches to distributing publications used by his contemporaries.Footnote 90 For example, John Stuart, the third earl of Bute, ensured that only twelve copies of his Botanical tables (1785) were published and then gifted to naturalists and aristocrats who had interests in natural history.Footnote 91 Recipients included King George III and Queen Charlotte, some of the major patrons of natural history during this period, in addition to Banks.Footnote 92 Similar ideas influenced the publications Banks managed from the mid-1780s. For example, during the production of Roxburgh's Plants of the coast of Coromandel (1795–1819), Banks explained that ‘The publication at present goes on but slowly, the Court find it expensive because they give away a great number of colord copies.’Footnote 93 Although this book was nominally published by a commercial bookseller, Banks used his influence to ensure the East India Company gave the majority of copies away to practitioners or patrons of natural history. Gifting lavish publications secured Banks's reputation as a patron of natural history and a gentleman who did not need to rely on profits from commerce or government grants for his income.Footnote 94

Banks created a similar network of exchange when circulating and editing the Philosophical Transactions, which was given to Fellows of the Royal Society and made financially viable, at least in theory, by membership fees.Footnote 95 Banks had a huge amount of power over the content and, although he sometimes sought an informal alternative opinion when reviewing articles, he had the final decision on acceptance.Footnote 96 As a result, Banks made sure his personal network and that of the Royal Society were not being used to circulate anything which could be associated with the Revolution. By the 1790s, the Society was governed by a range of carefully selected individuals who were able to defend its interests during the political unrest.Footnote 97 Gifting publications solidified this complex network of naturalists, institutions, and members of the government that formed the Banksian Learned Empire.Footnote 98

As the Revolution accelerated towards the Terror, Banks ensured that the audience for materials collected from the South Seas was even more specific than that of the journals of scientific societies. This is made clear by Forster, who, when writing to the historian Christian Wilhelm von Dohm in 1792, described the manner of accessing materials Banks and Solander had collected on Cook's first voyage to the Pacific between 1768 and 1771:

Banks is a Monopolist of everything that comes from the South Seas, he hates my father, envies me, publishes nothing, but leaves behind his enormous work of 1700 copperplates as Opus posthumum, because nobody can complete the text after Solander's death, and enjoys for the rest of his life to have this great work in his possession, so that people can always ask him if and when it will come out.Footnote 99

Forster's comments show that Banks never intended to circulate these illustrations or descriptions; those who wished to use them were forced to visit his home at 32 Soho Square. Banks could now limit access to this material to a select group who shared his political views. This was by no means the first time Banks had received criticism from continental European naturalists for his attitude towards publication. In the 1780s, the French Académie, who typically elected members on the basis of the merit of their publications, refused to elect Banks as a foreign associate because of his lack of published work.Footnote 100 Banks, however, maintained that he had avoided the ‘Reputation of an Author’ throughout his career, which he did ‘not consider a gentlemanly vocation’,Footnote 101 a view he shared with Bute, Henry Cavendish, and others among the elite. Authorship was, indeed, secondary to patronage when it came to elevation within the London-based scientific community, showing a distinct difference between British and continental practices.

Banks frequently advised Jonas Dryander, his librarian, to monitor the behaviour of naturalists who used the library at Soho Square to make sure they were not copying images for potential publication.Footnote 102 This concern partly came from many of the plants illustrated by Sydney Parkinson on Cook's first voyage originating in Tahiti. From the early 1790s, Tahiti and its association with an egalitarian and plentiful society – a representation inspired by the publication of the journals of Cook, Forster, and Bougainville – had contributed to the destruction of the ancien régime and threatened the long-standing European social order.Footnote 103 The reality of these threats to established social structures, including those of the Navy, became immediate to Banks after the mutiny of HMS Bounty in 1789, an event inspired by the beauty of Tahiti.Footnote 104

For Banks, the illustrations he had commissioned to represent plants from Tahiti retained vestiges of the island's original beauty and had the potential to inspire revolutionary thought. This was in spite of the various taxonomic conventions Banks and his engravers employed when producing the plates to represent the botanical discoveries of Cook's first voyage and Icones plantarum. Features such as colour, which were omitted from all of the printed images in Icones plantarum, had the potential to associate Banks's South Seas collections with ideas of ‘Jacobin plants’.Footnote 105 These were commonly associated with liberty and sexual freedom in Britain by figures such as Erasmus Darwin who was criticized by anti-Jacobins for his lack of respect for Linnaean taxonomic doctrine.Footnote 106 The images Banks commissioned are very different to the plates published in works such as Robert John Thornton's Temple of flora (1799–1807), a book compiled from large, colour botanical illustrations, the main subjects in which were superimposed in front of an intricate landscape background. Thornton's images were designed to integrate botanical practice into a new revolutionary art form, combining the science of botany with critiques of established social and taxonomic structures and were intended to be expensive, popular, and mass produced to turn Thornton a large profit.Footnote 107 Thornton's combination of commercial publishing and mass distribution with a lack of respect for Linnaean conventions associated these practices with the radical thought of the Revolution. As a result of the revolutionary connotations associated with botany, the Pacific, and commercial publishing, Banks sought to remove information on the natural history of the Society Islands from the public sphere and make sure it was restricted to a select social group who would use it to add to botanical knowledge and not provoke revolutionary ideals.

Forster held very different views on publishing his findings from the South Seas. Like many continental natural philosophers and historians, he believed that publishing was central to advancing his reputation as a naturalist; he thus sought to utilize the commercial publishing industry to maximize his income and ensure the wide distribution of his ideas. This is apparent from a letter to Banks dated 11 December 1785 in which Forster described how he ‘took an early opportunity’ to introduce the German ‘public’ to the results of Cook's second voyage through an article in the Göttingisches Magazin.Footnote 108 This is a somewhat similar strategy to that used by Voltaire, whose major motivation for publishing was to use booksellers’ desire for profits to improve the quality of his books and spread enlightenment.Footnote 109 Another incentive for authors to maximize the circulation of publications was the potential of payments and profits.Footnote 110 This was of use to Forster, allowing him to add to his own reputation and generate income to alleviate the numerous debts he had incurred since the mid-1770s.Footnote 111

Banks's and Forster's contrasting approaches to publishing led to direct conflict after the latter's move to Mainz. On 24 May 1790, Forster wrote to his father-in-law, the Göttingen-based classicist Christian Gottlob Heyne, commenting that ‘Sir Joseph Banks is polite and cold, like he is against every scholar; but in his heart he is the enemy of everyone who knows something of the southern sea’, adding that William Hodges and John Webber, the artists who had travelled on Cook's second and third voyages, held ‘bitter complaints against’ Banks.Footnote 112 Forster believed Banks's interpretation of copyright, methods of distributing publications, and attempts to prevent Hodges and Webber from publishing images, was not a model naturalists should follow. After visiting Soho Square in 1790, Forster held Banks and his means for disseminating the most recent research on natural history in distain. Banks used his ‘breakfast meetings’, which were held at Soho Square and attended by naturalists and philosophers who discussed the most recent publications and discoveries, as a major forum to discuss and distribute information. When describing these gatherings to Heyne, Forster commented on the reception of James Bruce's Travels to discover the source of the Nile (1790), describing how ‘Bruce's travels in Abyssinia are even less respected in London than they deserve’, adding that ‘At Banks's [house], where one judges sharply in general, they spoke such damming judgements that they even made him [Bruce] suspicious from the side of his credibility.’Footnote 113 Forster's observation of the reception of Bruce's publication reflects the power Banks and his circle had over the reputation of new books that related to the fields of natural history and exploration. The source of Banks's dissatisfaction with Bruce's work was that, according to Forster, ‘the greedy audience devoured in a short time a monstrous amount of copies’.Footnote 114 Bruce had utilized the Scottish commercial publishing markets and followed a similar publication plan to that Forster had in mind for the plants he had collected from the South Seas.

When Forster attempted during his visit to London in 1790 to publish the images of plants he had collected in the Pacific, Banks utilized his private wealth and institutional power to stop this publication. Forster described his efforts to publish to the German philosopher Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi in November 1791:

I wished to move the book sellers to publishing my plant descriptions from the Southern Sea. The fear to offend a man like Sir Joseph Banks, who believes to have a monopoly on southern sea plants, and to bring his damning judgement down on my book held them back. In Germany I may well find a publisher but not one who will pay me.Footnote 115

As this letter shows, Banks's power over London booksellers was so far advanced that he could stop publications: Banks believed the marketing of books exposed information to potential copyists, showing the relative volatility of the commercial publishing industry induced by the Revolution. This attitude was reinforced after Pitt's government passed the Treasonable Practices Act of 1795, which was designed to reduce the spread of radicalism in the popular press.Footnote 116 Banks did not wish for the images of Forster's South Seas plants to be published commercially, connecting it with the general circulation of radical literature.Footnote 117

The different political connotations associated with Tahiti, and especially that which increasingly related the island to radical politics as the Revolution progressed, ensured that Banks monitored those who viewed the images of plants Forster had produced in the South Seas. As a result, only two copies of Icones plantarum were printed in Banks's lifetime, one of which he kept in close proximity to the original drawings and herbarium specimens at 32 Soho Square. Banks gave the other copy to the botanist Aylmer Bourke Lambert (1761–1842), who had purchased Forster's herbarium after the death of Johann Reinhold Forster in 1798.Footnote 118 Although Banks only envisaged a limited distribution for Icones plantarum, printing around ten copies, there were few opportunities to circulate this book to continental European naturalists due to the disruption of his network and patronage system. On 27 September 1798, Lambert wrote to James Edward Smith, president of the Linnean Society, exclaiming that

I have the pleasure to inform you Forster's Herbarium is at last arrived in London & is now at Mr Plantas for me. It is the original Herbarium of the Flor: Insul: aust Prod: each specimen names & answering to the numbers in that work & all the original specimens of Plants described by him in the Gott: Comments.Footnote 119

Banks's gift of Icones plantarum at around the time Lambert purchased Forster's herbarium reflects Banks's desire to integrate these collections. Lambert had a similar social standing to Banks, owning substantial estates in Wiltshire, Ireland, and Jamaica, in addition to holding somewhat similar political views, coming from one of the more prominent Whig families of Wiltshire who remained staunch supporters of Pitt's government during the 1790s.Footnote 120 Lambert kept his library and herbarium in a large London house at 26 Lower Grosvenor Street. These were managed by several botanists over the years and followed a similar model to that used by Banks who hired a succession of librarians to work at Soho Square.Footnote 121

The gifting of Icones plantarum was essential for connecting Banks's collection to Lambert's, extending Banks's influence over botanical practice. This was reinforced by their simultaneous use of the Linnaean system to manage their collections and standardize botanical information. The closeness of Lambert's and Banks's relationship is evidenced by the amount of time Lambert spent at 32 Soho Square. Correspondents, such as the German botanist Carl Friedrich Gaertner (1772–1850), addressed letters to Lambert at Soho Square, in which he asked for access to Banks and his resources.Footnote 122 This close association explains why Lambert received a copy of Icones plantarum. When Lambert lent this book to Richard Pulteney in around 1800, the latter acknowledged its scarcity in his response: ‘Forster's Icones. You are in high luck here!’Footnote 123 Lambert's possession of this publication aligned his collection with Banks's at Soho Square, since many of the plants depicted in the copperplates held their basis in the specimens Lambert had purchased from Forster's heirs.Footnote 124 Aside from these two copies, the Icones plantarum copperplates never left the basement rooms of Soho Square during Banks's lifetime. Many of the plates were wrapped in the offprints of a pamphlet Banks wrote on financing a statue of the late duke of Bedford. These continue to encase several plates for Icones plantarum to this day (Figure 6).Footnote 125

Fig. 6. The original paper wrapper used by Banks's librarians to encase the plate used to print figures 43 and 52 for Forster's Icones plantarum. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London.

IV

The case of Icones plantarum shows how Banks interwove the practice of producing and disseminating a natural history publication with gentlemanly etiquette and the counter-revolutionary agendas of the British government. A result of the momentum attached to materials collected from the Pacific by the French Revolution, Banks created a closed system for producing and distributing publications. This involved censoring Icones plantarum and any attempt Forster made to publish materials from the South Seas, preventing these images from being obtained by any who might use them to further the revolutionary cause which threatened the hierarchical structures Banks held in such high esteem.

Banks's standpoint on the production and dissemination of knowledge defines the place natural history held in broader British society during the 1790s. Similar views on the usefulness of natural history to induce stability were held by other opponents to the Revolution. Perhaps the most vocal was Edmund Burke, who, in his Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) compared established social and religious hierarchies to the ‘ample collection of known classes, genera and species, which at present beautify the Hortus Siccus’.Footnote 126 This is very different to Burke's views on the physical sciences. For example, Burke rejected chemistry due to its association with Joseph Priestley and the fact that chemists could create their own classes for the multiple phenomena of nature rather than follow a prescribed set of rules.Footnote 127 Thus, figures such as Burke and Banks believed the close study of nature and its incorporation within hierarchic systems of classification brought order and structure to British society in the face of the political unrest caused by the Revolution.

This was central to contemporary defenders of the Linnaean system, who maintained that natural systems were intertwined with revolutionary politics which simultaneously threatened the social makeup of British society and the established order of nature. Banks mobilized his patronage network to defend the Linnaean system against the revolutionary natural systems, a similar standpoint to his views on the metric system of weights and measures.Footnote 128 It was not until the second decade of the nineteenth century that Robert Brown was able to introduce natural systems of classification in Britain, a feat he justified by anglicizing the new classificatory models by aligning them with the system developed by John Ray over a century before.Footnote 129 Banks's creation of a solid powerbase and patronage network maintained the dominance of Linnaean systematics in Britain until the 1820s, long after it had been superseded by natural systems on the continent. In 1831, the botanist John Lindley, who was determined to redefine botany as a new science, described how the decade approaching 1800 was dominated by a Linnaean ‘clique of English botanists’ that formed a ‘botanical aristocracy’ which claimed any who used natural systems were ‘misled by revolutionary motives’.Footnote 130

Icones plantarum reflects a larger scheme Banks initiated to induce stability in the sciences which was integrated with the intentions of Pitt's government and the counter-revolutionary state. The Linnaean system proved essential for imposing order on nature and aligned with Banks's interests in maintaining social order. Order in nature and society enabled Banks to grow his income from country estates. The stability in Banks's position throughout the revolutionary period allowed him to consolidate his station as an independent gentleman and ‘monarch’ of natural history, bringing the flora of the South Seas under the fold of the hierarchic structures Banks held in such high esteem. Icones plantarum combined the natural history of the Pacific with British, or more importantly English, gentlemanly etiquette, setting Banks aside from individuals such as Forster who combined the utopian vision of the South Seas islands with the egalitarian ideologies of the Revolution and commercial publishing. Unlike radicals such as Joseph Priestley or John Wilkes, whose homes were attacked by church and king crowds in the 1790s, Banks maintained political stability in his affairs throughout the revolutionary period. Only in 1815 did a mob, objecting to Banks's support for the Corn Laws, force their way into 32 Soho Square causing ‘boxes of valuable papers to be scattered in the street’.Footnote 131