During the COVID-19 pandemic, pregnant women around the world are reporting increased levels of distress due to lack of access to healthcare, social isolation and sleep loss.Reference Lebel, MacKinnon, Bagshawe, Tomfohr-Madsen and Giesbrecht1–Reference Wu, Zhang, Liu, Duan, Li and Fan3 Rates of prenatal depression have significantly increased in pregnant women during the pandemic.Reference Sun, Wang, Lin, Li, Yang and Liu4,Reference Perzow, Hennessey, Hoffman, Grote, Davis and Hankin5 Prenatal psychological distress – in particular, maternal depression – is a key risk factor for adverse maternal and neonatal health outcomes.Reference Dunkel Schetter and Tanner6,Reference Howard, Molyneaux, Dennis, Rochat, Stein and Milgrom7

Recent evidence suggests that pregnant women with COVID-19, as a consequence of the virus, are more likely to develop more severe illness compared with age-matched women who are not pregnant.Reference Ellington, Strid, Tong, Woodworth, Galang and Zambrano8 For instance, pregnant women with COVID-19 are more likely to be admitted to hospital, to be admitted to intensive care and to be intubated,Reference Ellington, Strid, Tong, Woodworth, Galang and Zambrano8 which can create an even greater risk of pregnancy complications in this population. Pregnant women who test positive for COVID-19 may experience higher levels of depressive symptoms, putting them and their infants at higher risk of adverse outcomes.

In the present study, we conducted an international survey to examine prenatal depression from May to September 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pregnant women completed questionnaires to assess depressive symptoms and COVID-19 status, as well as demographic information. Our central hypothesis was that pregnant women who tested positive for COVID-19 would be at greater risk of depressive symptomatology in comparison with pregnant women without COVID-19, adjusting for demographic variables.

Method

A prospective online survey study of English-speaking pregnant women was conducted during May to September 2020. Women were recruited online using advertisements on social media from Canada, USA, UK, India and other countries. Women were asked whether they had been tested for COVID-19 and whether the test was positive or negative. Pregnant women were enrolled (N = 1185). Complete data were available for 869 women (73%); 18 women reported they had tested positive, 133 reported they had tested negative and 718 reported that they had not been tested for COVID-19 (Table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of pregnant women who tested positive or negative, or who were not tested for COVID-19

a. Other countries included South Africa, the Philippines, Brazil, Croatia, Italy, Fiji and 43 other countries.

b. Years of education: 18, graduate degree; 21, postgraduate/professional degree.

c. EPDS score ≥14; probability values provide results using one-way analysis of variance for continuous measures and χ2-test for categorical measures. Statistically significant results are shown in bold.

* Denotes significant result.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Research Ethics Board at Western University (REB #115810), which approved the study, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Self-reported data on COVID-19 status (positive, negative, never tested) were collected. Depressive symptomatology was assessed using the Edinburgh Perinatal/Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). The EPDS is a self-report questionnaire that includes ten items relating to common symptoms of depression.Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky9 Participants rate each item on a scale from 0 to 3 points to indicate the presence and frequency of their symptoms over the past 7 days.Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky9 The total score for the EPDS is a sum of the raw score of each item, where a higher score is indicative of more frequent and severe symptoms.Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky9 Scores greater than 13 on the EPDS are indicative of probable clinical depression.Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky9

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (v. 26, IBM Armonk, NY, USA). The prevalence of depression (i.e. EPDS scores <13 v. ≥14) based on COVID-19 status (positive [n = 18] v. negative [n = 133]; positive [n = 18] v. untested [n = 718]) was examined using logistic regression. Total EPDS scores among the pregnant women were examined using a general linear model based on COVID-19 test status (positive, negative, untested). Both logistic and linear regression models were adjusted for age, education level, gestational age, country and survey completion month.

Results

The prevalence of depression was significantly higher in women who reported testing positive for COVID-19 compared with women who tested negative (adjusted odds ratio[aOR] = 4.34, 95% CI = 1.18–15.90, P = 0.027), as well as compared with untested women (aOR = 5.31, 95% CI = 1.66–16.94, P = 0.005), adjusting for age, education level, gestational age, country and survey completion month.

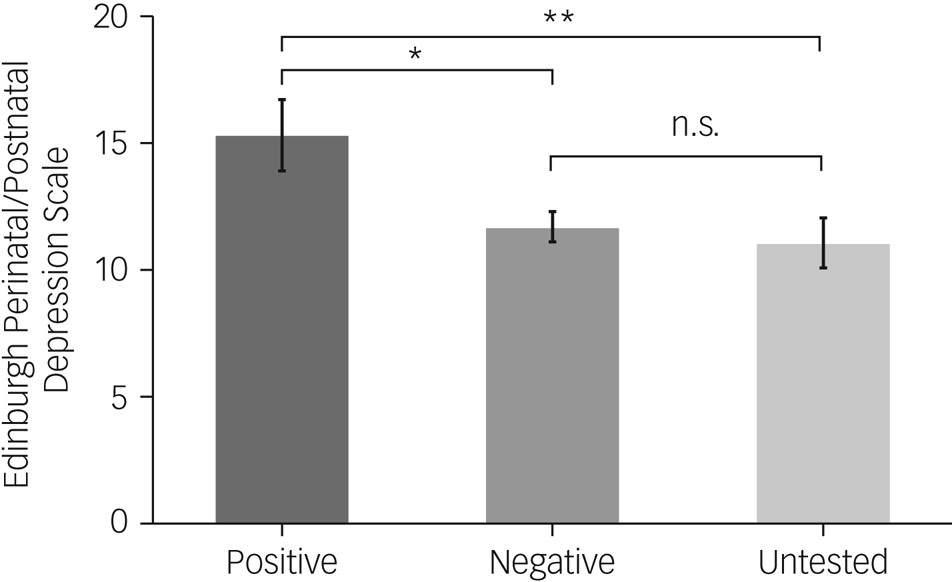

COVID-19-positive women had higher total scores on the EPDS compared with women who tested negative (B = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.14–1.13, P = 0.01) and compared with the group of women who were not tested for COVID-19 (B = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.26–1.21, P = 0.002), both after adjustment for covariates. Results were maintained after a pairwise Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. The associations of COVID-19 test status with EPDS scores are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 COVID-19 status and EPDS scores in pregnant women. EPDS scores for pregnant women who reported testing positive or negative, or who were not tested for COVID-19. Women who reported testing positive for COVID-19 had higher EPDS scores than women who reported testing negative (P = 0.038, 95% CI 0.02–1.24) or untested women (P = 0.007, 95% CI 0.16–1.32). No statistically significant differences between pregnant women who reported testing negative for COVID-19 and untested women (P = 0.81, 95% CI −0.34–0.13) were evident. Values represent the estimated marginal means of EPDS scores, adjusted for age, country of residence, education, survey completion month and gestational age at survey completion. P-values are Bonferroni corrected (pairwise) for multiple comparisons. Error bars reflect s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n.s. (not significant).

Discussion

Mental health is a key predictor of maternal health during pregnancy, neonatal outcomes and offspring development.Reference Davenport, Meyer, Meah, Strynadka and Khurana10 Pregnant women who reported testing positive for COVID-19 had significantly higher rates of depression compared with untested women and those who reported testing negative. Although analyses were adjusted for gestational age, women who reported testing positive for COVID-19, were assessed early in their pregnancies, and they indicated they experienced greater depressive symptoms, given the potential unknown outcomes associated with maternal illness and fetal outcomes.

Limitations of the current study included that COVID-19 diagnosis status was based on self-report, women were not recruited based on COVID-19 test outcome status, the study only assessed depression and no other mental health indicators, the data were collected at one time point during pregnancy, and the sample size of women who reported testing positive for COVID-19 was small. Data were obtained from a large heterogenous population of pregnant women, and although we adjusted for demographic and perinatal factors, the groups based on COVID-19 status were unbalanced with respect to the women's country of origin; therefore, our results may be limited in terms of their generalisability. An additional consideration for our online study is that access to the internet and computers may have limited our sample to mainly include individuals from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. Future case–control studies are needed to further explore maternal depression and COVID-19 status. These studies would permit the comparison of women with a positive diagnosis with women who tested negative or were not tested who were from the same environment and faced comparable restrictions, as well as comparable access to antenatal care, given that these practices have differed internationally.Reference Chmielewska, Barratt, Townsend, Kalafat, van der Meulen and Gurol-Urganci11

Pregnant women who test positive for COVID-19 are in need of screening and monitoring for depression, as well as timely treatment in order to optimise outcomes for them and their families. Future research examining other mental health indicators in pregnant women with COVID-19 are needed to inform treatment options for this vulnerable group.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (E.G.D.) upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rachel Thorburn for her assistance with developing and implementing the study questionnaires.

Author contributions

E.G.D. had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Concept and design: E.G.D., M.F.M., R.J.V.L., I.G., E.S.N. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: all authors. Drafting of the manuscript: E.G.D., A.P., E.S.N. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors. Statistical analysis: E.G.D., A.P. Obtained funding: E.S.N., E.G.D., M.F.M. Administrative, technical or material support: A.P., E.G.D. Supervision: E.G.D., M.F.M.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (grant number R5853A14). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.