Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a severe and heterogeneous mental disorder, characterized by a pervasive pattern of instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, affects, and a marked impulsivity (Chapman, Reference Chapman2019). Despite recent advances in treating BPD (Storebø et al., Reference Storebø, Stoffers-Winterling, Völlm, Kongerslev, Mattivi, Jørgensen and Simonsen2020), an analysis of the effectiveness in routine clinical care for BPD pointed to the need of improving the reduction of BPD-specific symptoms (Herzog et al., Reference Herzog, Feldmann, Voderholzer, Gärtner, Armbrust, Rauh and Brakemeier2020). To achieve this goal, a precise understanding of the psychobiological processes underlying BPD is required. Although a genetic vulnerability in BPD is unquestionable, genetics alone may have little influence on the development of BPD in a favorable environment as a large part of the explained variance is attributable to individually unique environmental factors (Skoglund et al., Reference Skoglund, Tiger, Rück, Petrovic, Asherson, Hellner and Kuja-Halkola2021). Hence, the genetic vulnerability may translate into disordered perceptions and cognitions in the presence of adverse environmental conditions (e.g. childhood maltreatment, CM), that, in turn, likely increase the risk for developing a BPD (Fontaine & Viding, Reference Fontaine and Viding2008). To improve the understanding of these psychobiological processes in BPD, the present article seeks to apply current theories from neuroscience to provide a novel mechanistic model of BPD. In particular, we use a predictive processing (PP) framework to explain how the experience of CM, which is common in many people with BPD (Kleindienst, Vonderlin, Bohus, & Lis, Reference Kleindienst, Vonderlin, Bohus and Lis2020; Porter et al., Reference Porter, Palmier-Claus, Branitsky, Mansell, Warwick and Varese2020), alters perception and cognition, resulting in distinct psychobiological dysfunctions.

Predictive processing – an impactful theory of how the brain works

Considering the brain as a ‘phantastic’, hypothesis-testing organ (Friston, Stephan, Montague, & Dolan, Reference Friston, Stephan, Montague and Dolan2014), PP has become a prominent theory of fundamental working principles of the human brain (Clark, Reference Clark2013, Reference Clark2016a; Friston, Reference Friston2005; Hohwy, Reference Hohwy and Hohwy2014). Specifically, it has been theorized that the brain relies on principles of Bayesian inference to minimize uncertainty by continuously testing hypotheses regarding the causes of sensory input. In doing so, a prior belief is combined with new information to compute a posterior belief. If new information critically deviates from the prior prediction, a prediction error (PE) is generated. The (healthy) brain seeks to refine its hypotheses and maximize evidence for its internal model of the world by minimizing PEs.

At the neurobiological level, PP has been conceived of in terms of cerebral hierarchies (Friston, Reference Friston2008). Specifically, in neural representations of higher levels of cortical hierarchies, predictions are generated (encoded by synaptic activity), which then descend to lower levels. In superficial pyramidal cells, such descending top-down predictions are compared with neural representations at lower levels of the cortical hierarchy to compute a PE (Bastos et al., Reference Bastos, Usrey, Adams, Mangun, Fries and Friston2012). The PE (i.e. a mismatch signal) is sent back up the hierarchy where it updates prior beliefs or expectations (that generate top-down predictions), associated with the activity of deep pyramidal cells (Kanai, Komura, Shipp, & Friston, Reference Kanai, Komura, Shipp and Friston2015). For a more detailed discussion of the neural architecture of PP, see Barrett and Simmons (Reference Barrett and Simmons2015), Parr and Friston (Reference Parr and Friston2018), and Shipp (Reference Shipp2016).

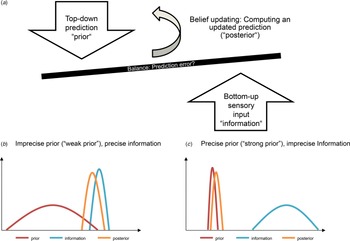

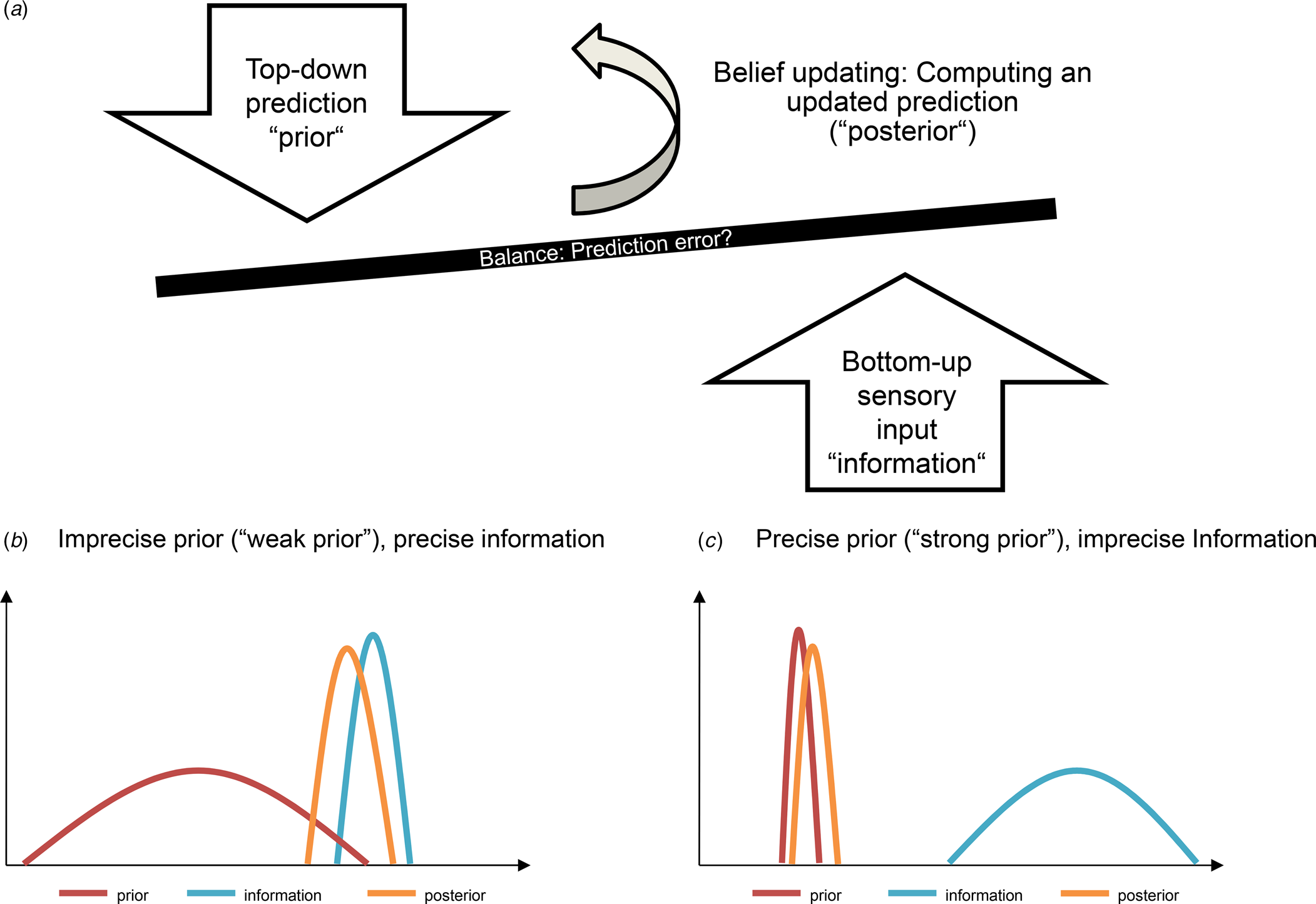

PP models also account for the outcomes of action, with the outcomes of actions being predicted based on causal knowledge (Heil, Kwisthout, van Pelt, van Rooij, & Bekkering, Reference Heil, Kwisthout, van Pelt, van Rooij and Bekkering2018). The human brain chooses the actions that are expected to produce the most preferred outcome or provides the most salient information. Briefly, this process suggests that such action-perception cycles operate to minimize uncertainty and optimize an individual's internal model of the world – a process referred to as active inference. Since perception in active inference is treated as a constructive process of hypothesis testing, where the brain aims to select the hypothesis that best explains sensory data, the brain must decide how much weight is given to new information relative to prior beliefs. This is referred to as precision-weighting, with precision being defined as ‘the certainty with which a model is believed to be true and the certainty of a particular afferent given an expectation’ (Paulus, Feinstein, & Khalsa, Reference Paulus, Feinstein and Khalsa2019). That is, precision can refer to both the reliability of new information and the confidence afforded to priors. Their balance critically determines the extent to which a prior is updated given new information. Put simply, if the prior is afforded low precision (referred to as ‘weak priors’), new information has more influence on the formation of the posterior, while the opposite is true for ‘strong priors’. In other words, if we are unsure about how much we can trust our beliefs, we prefer to rely on new information, provided that new information appears sufficiently valid. On the other hand, if priors are afforded overly much precision, they dominate perception such that information is consistent with prior predictions is prioritized and discrepant information is largely neglected (Powers, Mathys, & Corlett, Reference Powers, Mathys and Corlett2017).

Neurobiologically, the precision of sensory information is thought to be signaled by neuromodulators such as dopamine and encoded based on synaptic gain control mechanisms (Fiorillo, Newsome, & Schultz, Reference Fiorillo, Newsome and Schultz2008; Galea, Bestmann, Beigi, Jahanshahi, & Rothwell, Reference Galea, Bestmann, Beigi, Jahanshahi and Rothwell2012; Iglesias et al., Reference Iglesias, Mathys, Brodersen, Kasper, Piccirelli, denOuden and Stephan2013). Aberrations in precision-weighing have recently been related to a number of psychopathological dysfunctions and mental disorders, such as depression (Barrett, Quigley, & Hamilton, Reference Barrett, Quigley and Hamilton2016; Clark, Watson, & Friston, Reference Clark, Watson and Friston2018; Kube, Schwarting, Rozenkrantz, Glombiewski, & Rief, Reference Kube, Schwarting, Rozenkrantz, Glombiewski and Rief2020), stressors and psychological trauma (Krupnik, Reference Krupnik2020; Linson, Parr, & Friston, Reference Linson, Parr and Friston2020), PTSD (Kube, Berg, Kleim, & Herzog, Reference Kube, Berg, Kleim and Herzog2020a; Linson & Friston, Reference Linson and Friston2019; Wilkinson, Dodgson, & Meares, Reference Wilkinson, Dodgson and Meares2017), hallucinations in psychosis (Corlett et al., Reference Corlett, Horga, Fletcher, Alderson-Day, Schmack and Powers2019; Sterzer et al., Reference Sterzer, Adams, Fletcher, Frith, Lawrie, Muckli and Corlett2018) and in PTSD (Lyndon & Corlett, Reference Lyndon and Corlett2020), autism (Lawson, Rees, & Friston, Reference Lawson, Rees and Friston2014; Pellicano & Burr, Reference Pellicano and Burr2012), and somatization (Henningsen et al., Reference Henningsen, Gündel, Kop, Löwe, Martin, Rief and van den Bergh2018; Kube, Rozenkrantz, Rief, & Barsky, Reference Kube, Rozenkrantz, Rief and Barsky2020b; van den Bergh, Witthöft, Petersen, & Brown, Reference van den Bergh, Witthöft, Petersen and Brown2017).

The belief updating process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic illustration of the belief updating process. (a): Precision can refer to both the reliability of new information and the confidence afforded to priors. Their balance critically determines the extent to which a prior is updated given new information. Put simply, if the prior is afforded low precision (referred to as ‘weak priors’), new information has much influence on the formation of the posterior (b), while the opposite is true for ‘strong priors’ (c). In other words, if we are unsure about how much we can trust our beliefs, we prefer to rely on new information, provided that new information appears sufficiently valid. On the other hand, if priors are afforded overly much precision, they dominate perception such that information that is consistent with prior predictions is prioritized and discrepant information is largely neglected (Powers et al., Reference Powers, Mathys and Corlett2017).

In the present article, we apply this account to BPD, proposing that BPD is related to an imbalance of hierarchical priors – specifically, imprecise prior beliefs, relative to sensory evidence – based upon a learning history of CM. Before we will lay out the central tenets of this account, we first briefly review the literature on normal infant learning from a PP perspective to understand how adverse environmental conditions (that is, CM) perturbs the perceptual system, which can ultimately result in psychopathological dysfunctions as manifested in BPD.

Normal infant learning

Research has shown that PP may provide a unifying perspective on infant learning, including statistical learning principles, motor and proprioceptive learning, and developing a basic understanding of the self and their physical and social environment (Köster, Kayhan, Langeloh, & Hoehl, Reference Köster, Kayhan, Langeloh and Hoehl2020). Using Violation-of-Expectation paradigms (Sokolov, Reference Sokolov1963, Reference Sokolov1990), research has shown that infants use novel and unexpected experiences (i.e. PEs) to refine their predictive models of the world, as indicated e.g. in studies using event-related potential technique (Köster, Langeloh, & Hoehl, Reference Köster, Langeloh and Hoehl2019; Langeloh, Buttelmann, Pauen, & Hoehl, Reference Langeloh, Buttelmann, Pauen and Hoehl2020). Indeed, recent research has emphasized that infants build and update their predictive models of a changing environment early in their lives (Kayhan, Meyer, O'Reilly, Hunnius, & Bekkering, Reference Kayhan, Meyer, O'Reilly, Hunnius and Bekkering2019), suggesting that reducing uncertainty in a changing world is an important developmental goal.

Childhood maltreatment in BPD

Learning from PEs in infancy can be hindered or disrupted by a harmful environment. For instance, a longitudinal study revealed that the experience of attachment disorganization and parental hostility in early childhood was associated with dysfunctions in several domains (i.e. attention, emotion, behavior, relationship, and self-representation) in middle childhood/early adolescence and, ultimately, symptoms of BPD in adulthood (Carlson, Egeland, & Sroufe, Reference Carlson, Egeland and Sroufe2009). Harmful learning experiences in childhood, such as neglect and abuse, have been referred to as CM. CM constitutes as a transdiagnostic risk factor for mental disorders (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson2009; Struck et al., Reference Struck, Krug, Yuksel, Stein, Schmitt, Meller and Brakemeier2020) and plays an important role in the development of personality disorders in general (Afifi et al., Reference Afifi, Mather, Boman, Fleisher, Enns, MacMillan and Sareen2011; Battle et al., Reference Battle, Shea, Johnson, Yen, Zlotnick, Zanarini and Morey2004) and BPD in particular (Brakemeier et al., Reference Brakemeier, Dobias, Hertel, Bohus, Limberger, Schramm and Normann2018; Pietrek, Elbert, Weierstall, Müller, & Rockstroh, Reference Pietrek, Elbert, Weierstall, Müller and Rockstroh2013; Quenneville et al., Reference Quenneville, Kalogeropoulou, Küng, Hasler, Nicastro, Prada and Perroud2020; Wota et al., Reference Wota, Byrne, Murray, Ofuafor, Nisar, Neuner and Hallahan2014). The majority of patients with BPD experienced some sort of maltreatment in their childhood (Battle et al., Reference Battle, Shea, Johnson, Yen, Zlotnick, Zanarini and Morey2004; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Egeland and Sroufe2009): A recent study showed that patients with BPD were over 13 times more likely to report childhood adversity than non-clinical controls and other clinical populations (Kleindienst et al., Reference Kleindienst, Vonderlin, Bohus and Lis2020; Porter et al., Reference Porter, Palmier-Claus, Branitsky, Mansell, Warwick and Varese2020). Among the most frequent subtypes of CM in BPD are emotional abuse and neglect compared to controls (Scheffers, van Vugt, Lanctôt, & Lemieux, Reference Scheffers, van Vugt, Lanctôt and Lemieux2019). While studies showed that BPD was associated with higher scores on sexual abuse beside of emotional abuse and neglect (Bradley, Jenei, & Westen, Reference Bradley, Jenei and Westen2005; Hernandez, Arntz, Gaviria, Labad, & Gutiérrez-Zotes, Reference Hernandez, Arntz, Gaviria, Labad and Gutiérrez-Zotes2012; Igarashi et al., Reference Igarashi, Hasui, Uji, Shono, Nagata and Kitamura2010; Lobbestael, Arntz, & Bernstein, Reference Lobbestael, Arntz and Bernstein2010; Ogata et al., Reference Ogata, Silk, Goodrich, Lohr, Westen and Hill1990; Weaver & Clum, Reference Weaver and Clum1993; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chow, Wang, Yu, Dai, Lu and Xiao2013), particular in women (de Aquino Ferreira, Queiroz Pereira, Neri Benevides, & Aguiar Melo, Reference de Aquino Ferreira, Queiroz Pereira, Neri Benevides and Aguiar Melo2018), other studies indicated no independent relationship between sexual abuse and BPD (Cohen et al., Reference Cohen, Tanis, Bhattacharjee, Nesci, Halmi and Galynker2014; Widom, Czaja, & Paris, Reference Widom, Czaja and Paris2009) or reported small effect sizes for sexual abuse (Hengartner, Ajdacic-Gross, Rodgers, Müller, & Rössler, Reference Hengartner, Ajdacic-Gross, Rodgers, Müller and Rössler2013). In line, only emotional instability or vulnerability, impulsivity, and emotional abuse were found to be unique predictors of BPD (Bornovalova, Gratz, Delany-Brumsey, Paulson, & Lejuez, Reference Bornovalova, Gratz, Delany-Brumsey, Paulson and Lejuez2006). Moreover, social exclusion (ostracism) might be a psychosocial factor contributing to the development and persistence of BPD, in the sense of a vicious cycle where BPD increases the chance of being ostracized, and ostracism consolidates or even aggravates psychopathology (Reinhard et al., Reference Reinhard, Dewald-Kaufmann, Wüstenberg, Musil, Barton, Jobst and Padberg2020). For example, bullying and violence in schools and emotional abuse appear to be more salient markers of general personality pathology than other forms of childhood adversity (Hengartner et al., Reference Hengartner, Ajdacic-Gross, Rodgers, Müller and Rössler2013). Insights from a sibling design showed that both probands and sisters reported similar prevalence of intrafamilial abuse, although later BPD patients reported more severe intrafamilial physical and emotional abuse, and higher prevalence of physical abuse by peers (Laporte, Paris, Guttman, Russell, & Correa, Reference Laporte, Paris, Guttman, Russell and Correa2012). Furthermore, another study that prospectively followed a sample who had experienced childhood abuse showed an increase in risk for BPD primarily in children who experienced physical abuse and neglect (Widom et al., Reference Widom, Czaja and Paris2009). In particular, terrorizing predicted anxiety and somatic concerns, ignoring predicted depression scores and BPD features, and degradation predicted BPD features only (Allen, Reference Allen2008).

Psychological consequences of childhood maltreatment

Co-regulation and social communication in infancy are thought to underpin emotional dysregulation and social cognition deficits across development and these mechanisms are further potentiated by maladaptive social experiences in a series of positive feedback loops (Winsper, Reference Winsper2018; Winsper et al., Reference Winsper, Marwaha, Lereya, Thompson, Eyden and Singh2016). Interestingly, studies suggest an association between CM, especially emotional abuse and neglect, and emotion regulation difficulties in a way that emotion regulation difficulties influence the association between emotional abuse and acute symptomatology in BPD (e.g. Carvalho Fernando et al., Reference Carvalho Fernando, Beblo, Schlosser, Terfehr, Otte, Löwe and Wingenfeld2014), supporting the Emotional Dysregulation theory (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993). While CM impacts impulsivity and anger (Quenneville et al., Reference Quenneville, Kalogeropoulou, Küng, Hasler, Nicastro, Prada and Perroud2020), one study showed that difficulties in emotion regulation statistically mediated the effect of CM on impulsivity in BPD (Krause-Utz et al., Reference Krause-Utz, Erol, Brousianou, Cackowski, Paret, Ende and Elzinga2019), further supporting this theory.

Consistent with these findings, a study showed a moderate relationship between low emotional awareness (EA) (especially difficulties in identifying and describing emotions) and BPD (Derks, Westerhof, & Bohlmeijer, Reference Derks, Westerhof and Bohlmeijer2017). Of note, EA has recently been conceptualized within an active inference model: the authors showed that it can successfully acquire a repertoire of emotion concepts in its ‘childhood’, as well as acquire new emotion concepts in synthetic ‘adulthood’, and that these learning processes depend on early experiences, environmental stability, and habitual patterns of selective attention (Smith, Parr, & Friston, Reference Smith, Parr and Friston2019b). Distinct neurocomputational processes underlying EA have further been developed, e.g. mechanisms that (either alone or in combination) can produce phenomena – such as somatic misattribution, coarse-grained emotion conceptualization, and constrained reflective capacity – characteristic of low EA (Smith, Lane, Parr, & Friston, Reference Smith, Lane, Parr and Friston2019a). Relatedly, while one study found no specific association between parenting style with BPD (Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez, Arntz, Gaviria, Labad and Gutiérrez-Zotes2012), a meta-synthesis study found that maladaptive parenting is a well-established psychosocial risk factor for the development of BPD (Steele, Townsend, & Grenyer, Reference Steele, Townsend and Grenyer2019). A prominent study showed that family environment, parental psychopathology, and history of abuse all independently predicted BPD (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Jenei and Westen2005).

Integrating the environmental factors from a lifespan perspective, literature suggests that vulnerability from mother to offspring may be partly transmitted via maladaptive parenting and maternal emotional dysfunction, i.e. mothers with BPD are more likely to engage in maladaptive interactions with their offspring characterized by insensitive, overprotective, and hostile parenting compared to mothers without BPD resulting in adverse offspring outcomes such as BPD symptoms, internalizing (e.g. depression) and externalizing problems, insecure attachment patterns, and emotional dysregulation (Eyden, Winsper, Wolke, Broome, & MacCallum, Reference Eyden, Winsper, Wolke, Broome and MacCallum2016). Importantly, CM and its link to BPD features exist already in children (Ibrahim, Cosgrave, & Woolgar, Reference Ibrahim, Cosgrave and Woolgar2018). One important factor might be negative emotional reactivity that seems to be a marker of vulnerability that increases the risk for the development of BPD (Stepp, Scott, Jones, Whalen, & Hipwell, Reference Stepp, Scott, Jones, Whalen and Hipwell2015). In the supplement, we also provide an extensive review of the psychological consequences of CM on social cognition and their implications for treatment (see online Supplemental Material 1). Here, we want to focus on how the effects of CM in individuals with BPD can be conceived of in PP terms.

Childhood maltreatment and predictive processing

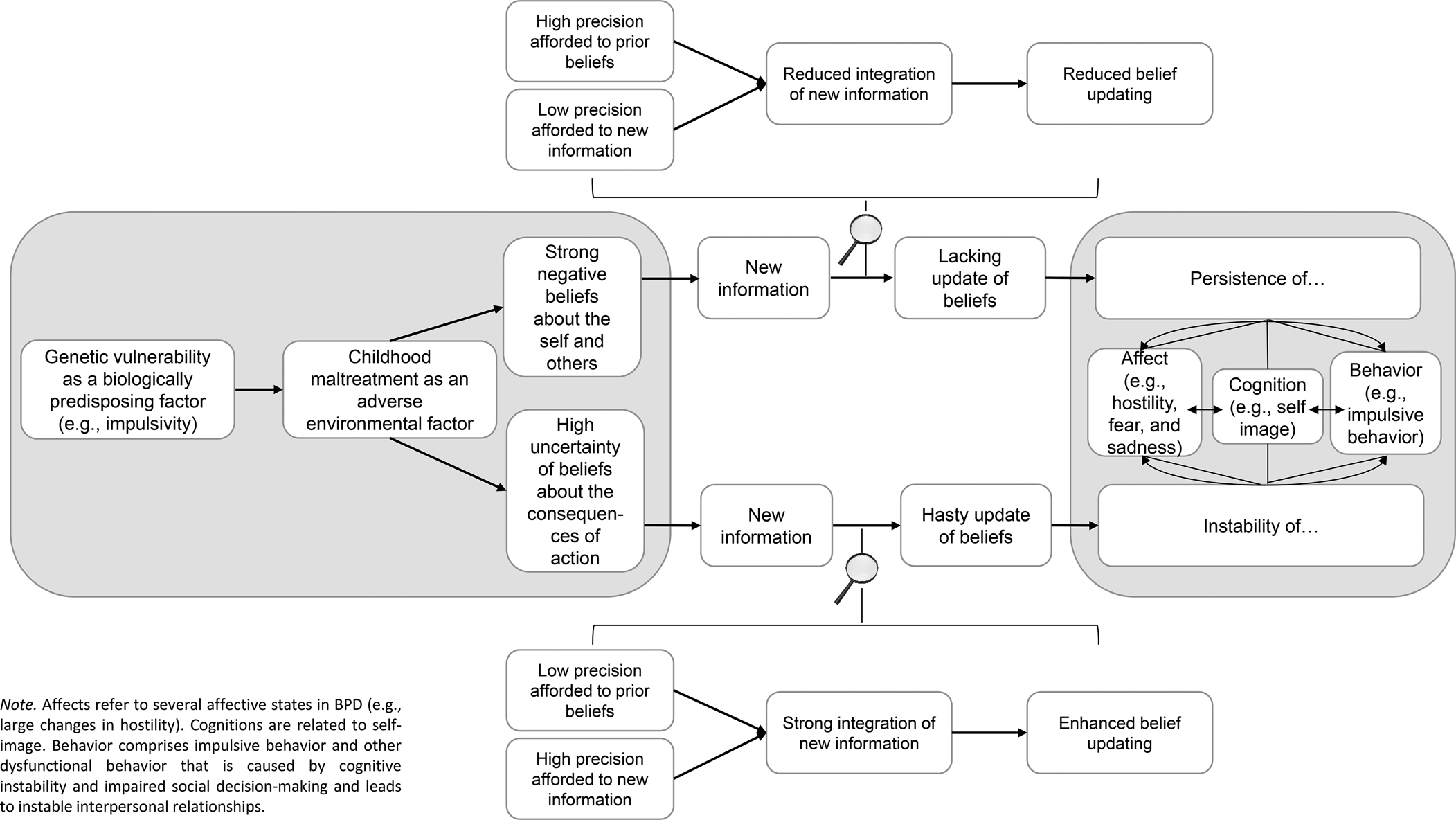

In brief, we are proposing a developmental active inference and learning account of BPD that can be summarized as follows: Early traumatic experiences (i.e. CM) – particularly those involving disorganized attachment or emotional abuse/neglect – lead to an impoverished model of self and others, under which the consequences of social behavior are unpredictable. This has two consequences:

First, a loss of confidence or precision when selecting the course of action in social exchanges. This irreducible uncertainty – about ‘what would happen if I did that?’ – underwrites the emotional lability and impulsivity, characteristic of BDP. The implicit loss of precision, afforded prior beliefs about social narratives, renders belief updating overly sensitive to sensory evidence and social feedback.

To illustrate this key aspect of our argument, consider the example of a child being sad and crying because it feels alone, with the mother invalidating the child's experience by saying there is no reason to be sad and leaving the room. In this case, the child experiences a lack of understanding and feel that their emotions and thoughts are called into question by their parents or significant others (Musser, Zalewski, Stepp, & Lewis, Reference Musser, Zalewski, Stepp and Lewis2018), resulting in an impoverished model of the self in form of low emotional awareness (especially difficulties in identifying and describing emotions) (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Parr and Friston2019b; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Steklis, Steklis, Weihs, Allen and Lane2022) that has been linked to BPD (Derks et al., Reference Derks, Westerhof and Bohlmeijer2017). Relatedly, early risk factors for BPD in adulthood include the maternal withdrawal in infancy and separation of 1 month or more from the mother in the first 5 years of life (Steele & Siever, Reference Steele and Siever2010). Furthermore, an interesting candidate for a specific parent-child-relationship risk factor for BPD is parental inconsistency (Boucher et al., Reference Boucher, Pugliese, Allard-Chapais, Lecours, Ahoundova, Chouinard and Gaham2017), leading to the child's perception that other people's behavior is unpredictable. If such invalidating situations are frequently experienced, it is understandable that the child does not learn to place confidence in their beliefs and thus remains uncertain about the causes of their sensations. Put another way, such repeated experiences leave the child with the interpretation that their thoughts and emotions are ‘wrong’, leading in turn to increased uncertainty about their beliefs and perceptions that results in dysfunctional behavior (e.g. ineffective emotion regulation strategies). Indeed, a recent study indicated that BPD, compared to other mental disorders, is associated with a less frequent use of effective emotion regulation strategies (i.e. cognitive reappraisal, problem solving, and acceptance) and a more frequent use of dysfunctional emotion regulation strategies (i.e. suppression, rumination, and avoidance) (Daros & Williams, Reference Daros and Williams2019).Footnote *Footnote 1

Second, the failure to learn a suitably expressive generative model, during neurodevelopment, leaves patients with BDP with impoverished, coarse-grained models of self and other. The ensuing interpersonal ‘alexithymia’ manifests as rigidity and inflexibility in social or affective interactions. In other words, everything is ‘black or white’, with no ‘shades of gray’ that would support a nuanced inference about the intention of others (and self). In the absence of an expressive social world model, the only explanations available – for unpredicted sensory or social outcomes – are ‘I am worthless’ (i.e. self-critical explanations) or ‘you are punitive’ (i.e. paranoid explanations).

This developmental account rests upon the intimate relationship between learning and inference. Here, a failure to learn a sufficiently expressive model of interpersonal narratives precludes prosocial inference and planning that precludes subsequent learning or updating of self-other models. This is not unlike some accounts of severe autism and the failure to attain central coherence (Happé & Frith, Reference Happé and Frith2006; van de Cruys et al., Reference van de Cruys, Evers, van der Hallen, van Eylen, Boets, de-Wit and Wagemans2014). In autism, this developmental failure is sometimes attributed to failure of sensory attenuation (i.e. a failure to attenuate sensory precision in relation to prior precision). This suggests interesting parallels between self stimulation in autism and non-fatal self-harm in BPD.

In terms of the neurochemistry of uncertainty or precision encoding in the brain, our analysis speaks to the same kind of hyperdopaminergic state that may characterize certain forms of schizophrenia or delusional disorders. In our case, this can be read directly from the role of dopamine in active inference, as scoring the resolution of uncertainty about policies afforded by sensory evidence: in BPD, every piece of sensory (or social) information resolves uncertainty. This is because beliefs about the narrative currently being pursued are always uncertain or imprecise. The analogy with schizophrenia here may be useful in the sense that some people interpret delusions as an attempt to make sense of unattenuated sensory evidence (Sterzer et al., Reference Sterzer, Adams, Fletcher, Frith, Lawrie, Muckli and Corlett2018).

The predictive processing account of BPD

While most models of BPD take a lifespan approach and consider the complex interplay of biological vulnerabilities (e.g. genetics), psychological factors and social influences (Stepp, Lazarus, & Byrd, Reference Stepp, Lazarus and Byrd2016), BPD is currently viewed as a disorder of instability, i.e. instability of interpersonal relationships, self-image, affects, and, relatedly, a marked impulsivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Here, we recast these core clinical aspects of BPD through the lens of a PP model (see Fig. 2). In doing so, we build upon a few previous accounts offering computational perspectives on BPD (Fineberg, Reference Fineberg2019; Fineberg, Stahl, & Corlett, Reference Fineberg, Stahl and Corlett2017; Fineberg, Steinfeld, Brewer, & Corlett, Reference Fineberg, Steinfeld, Brewer and Corlett2014b). For example, in an elaborated approach, Fineberg et al. (Reference Fineberg, Stahl and Corlett2017) put emphasis on the association between early disruption of mothers' physical care and social dysfunction as a key feature in BPD, explained by social learning depending on reinforcement learning though embodied simulations.

Fig. 2. Portrayal of the basic assumptions of the predictive processing account of BPD.

Affective instability

BPD is characterized by an affective instability, in terms of rapid changes of mood, ranging from chronic feelings of emptinessFootnote 2 to intense anger, anxiety, or dysphoria – and difficulties in handling these mood fluctuations. From a PP point of view, emotional states have been theorized to be a consequence of acting in the world with the aim of minimizing expected free energy, that is, the uncertainty about the future consequences of actions (Kiverstein, Miller, & Rietveld, Reference Kiverstein, Miller and Rietveld2020). In other words, emotional states reflect changes in the uncertainty about the somatic consequences of action (Joffily & Coricelli, Reference Joffily and Coricelli2013; Seth & Friston, Reference Seth and Friston2016; Wager et al., Reference Wager, Kang, Johnson, Nichols, Satpute and Barrett2015), with uncertainty relating to the precision with which motor and physiological states are predicted and inferred (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Watson and Friston2018). By this view, painful emotions have been thought to accompany events that elicit beliefs of unpredictability, whereas pleasant emotions refer to events that resolve uncertainty and convey a sense of control and confidence (Barrett & Satpute, Reference Barrett and Satpute2013; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Watson and Friston2018; Gu, Hof, Friston, & Fan, Reference Gu, Hof, Friston and Fan2013). Thus, the valence of emotional states relates to the resolution of uncertainty and the precision with which the consequences of action are predicted (Brown & Friston, Reference Brown and Friston2012; Clark et al., Reference Clark, Watson and Friston2018). Interestingly, BPD features predicted specific patterns of bias with regard to forecasting future (negative) emotional states (Hughes & Rizvi, Reference Hughes and Rizvi2019).

Linking this account with the corollaries of CM as discussed above, we suggest that BPD is related to the failure to resolve uncertainty and the dominance of predictions of unpredictability, resulting in intense painful emotions. Relatedly, we propose that people with BPD afford their beliefs about the consequences of action little precision; as a result, interoceptive experience is largely influenced by sensory evidence. Hence, the exact emotional experience may vary greatly with respect to the nature and the source of sensory information. In other words, because people with BPD have learned to be uncertain about their consequences of action, their emotional experience fluctuates significantly depending on the (perceived) situational circumstances and other people's behavior. For example, as people with BPD have often grown up in an invalidating environment, they may have learnt that experiencing a certain emotion (e.g. sadness) and expressing a corresponding emotional need (e.g. being consoled by their parents) has no influence on their parents' actual response (e.g. neglect perceived as a negative consequence). Thus, they cannot resolve uncertainty and experience fluctuating intense emotions, by likewise generating a distorted internal model of emotions (e.g. no access to the concept of being consoled) and a reduced self-efficacy. In addition to the uncertainty inherent to beliefs of people with BPD, the experience of CM and the deficit in adaptive emotion regulation strategies may lead to the pervasive belief that emotions are uncontrollable. Due to the high precision afforded to it, this belief is difficult to be revised through new experiences.

Self-image instability

Besides affective instability, BPD is characterized by identity instability which leads to a markedly and persistently unstable, yet often negative, self-concept as well as a lack of a self-coherence. This cognitive instability is related to uncertainty in at least two of the following life domains: self-image, sexual orientation, long-term goals or career choice, type of friends desired, and values. From a PP point of view, this self-image instability manifests through low precision that is afforded to prior beliefs. As a result, beliefs are hastily updated in line with novel information. In other words, because the beliefs of people with BPD – about both the self and others – are fraught with uncertainty, they are often updated based on fairly thin evidence. This account is well in line with evidence from experimental studies, particularly research that has examined how people with BPD update their beliefs in response to social feedback. For instance, Korn, la Rosée, Heekeren, & Roepke (Reference Korn, la Rosée, Heekeren and Roepke2016a) found that people with BPD, in contrast to healthy people (Korn, Prehn, Park, Walter, & Heekeren, Reference Korn, Prehn, Park, Walter and Heekeren2012), adjusted their beliefs about themselves significantly in line with undesirable social feedback, that is, a single negative interpersonal experience (Korn et al., Reference Korn, Prehn, Park, Walter and Heekeren2012, Reference Korn, la Rosée, Heekeren and Roepke2016a). In line with that, Liebke et al. (Reference Liebke, Koppe, Bungert, Thome, Hauschild, Defiebre and Lis2018) showed in a virtual group-interaction paradigm (where participants interacted with a group of computer-controlled avatars, although they believed them to be real human co-players) that people with BPD updated their beliefs about being socially accepted in response to negative but not positive social feedback (Liebke et al., Reference Liebke, Koppe, Bungert, Thome, Hauschild, Defiebre and Lis2018). Interestingly, the authors demonstrated that people with BPD even behaved less cooperatively in a subsequent trust game if they had previously received positive social feedback. Similarly, another study found that whereas healthy people focus on the positive aspects of social feedback, people with BPD focus more on negative feedback, thereby maintaining negative self-views (Van Schie, Chiu, Rombouts, Heiser, & Elzinga, Reference Van Schie, Chiu, Rombouts, Heiser and Elzinga2020).

This volatility of belief updating – with more adjustments in response to negative feedback – can again be linked to the effects of early learning experiences and CM. In particular, children who experienced CM often receive negative social feedback, e.g. parents' scolding, which children seek to integrate in their attempt to satisfy their parents. When unexpectedly receiving positive feedback, children might be confused about how to interpret that, thus increasing the uncertainty in the children's perceptions and predictions. In computational terms, the world (i.e. the social feedback by significant others) seems unpredictable as the child is permanently exposed to PEs. Given the prevailing negative social feedback, though, people with CM learn to afford higher precision to negative than to positive feedback, while at the same time affording high precision to negative prior beliefs about the self. Both contributes to the above-described asymmetry in belief updating in BPD, with more rapid changes in line with novel negative information and the persistence of strong negative beliefs about the selfFootnote 3. This affects also social decision making and learning in a way that BPD patients expect higher volatility than control which underpins social and non-social belief updating in BPD (Fineberg et al., Reference Fineberg, Leavitt, Stahl, Kronemer, Landry, Alexander-Bloch and Corlett2018b).

Instability of interpersonal relationships

As a consequence of self-image instability and impaired social decision making, BPD is also associated with a pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships, while alternating between extremes in the perception of other people, i.e. idealization and devaluation. For example, patients' perceptions of their therapist can change rapidly, from beliefs such as ‘My therapist is the only person who has ever understood me’ to ‘My therapist wants to get rid of me’. From a PP perspective, idealization and devaluation is related to hasty changes of beliefs about other people, resulting from weak priors and high precision afforded to new information. This instability likely leads to difficulties in interpersonal relationships, with rapid alternations of desperate efforts to avoid abandonment and a premature relationship termination. In line with this notion, research has shown that BPD patients exhibit less trust during interpersonal interactions (Unoka, Seres, Áspán, Bódi, & Kéri, Reference Unoka, Seres, Áspán, Bódi and Kéri2009), reflecting the high degree of uncertainty people with BPD experience in social interactions. In a transdiagnostic clinical sample, it has been shown that a reduced confidence in how to act, rather than increased emotional conflicts, explains maladaptive approach-avoidance behaviors, i.e. a greater decision uncertainty during approach-avoidance conflicts (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Kirlic, Stewart, Touthang, Kuplicki, Khalsa and Aupperle2020). Consistent with that, a recent study found a 2-fold larger preferred interpersonal distance in BPD patients than in healthy people (Fineberg et al., Reference Fineberg, Leavitt, Landry, Neustadter, Lesser, Stahl and Corlett2018a).

In addition to instability in their relationships, people with BPD also form strong negative beliefs about relations to other people in their attempt to reduce uncertainty, as touched upon above. This rigidity in beliefs about other people may underlie another symptom cluster of BPD: transient, stress-related paranoid ideation (i.e. the belief that harm is intended by others). In line with this account, a recent study found that paranoia may make it harder to update beliefs and it is linked with an increased risk of violence towards oneself (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Uddenberg, Suthaharan, Mathys, Taylor, Groman and Corlett2020). More precisely, this study showed that uncertainty may be sufficient to elicit learning differences in paranoid individuals, even without social threat; and paranoia is associated with a stronger prior on volatility, accompanied by elevated sensitivity to perceived changes in the task environment (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Uddenberg, Suthaharan, Mathys, Taylor, Groman and Corlett2020). In other words, people with paranoia expect the world to change frequently, change their minds repeatedly, and have a harder time learning in response to changing circumstances. This finding is in line with the general high uncertainty of BPD patients and may explain paranoid ideation in BPD, further highlighting the interdependence between inference and learning in BPD. That is, BPD patients with higher scores on paranoid ideations might have more difficulty updating their beliefs in interpersonal situations (i.e. learning difficulties in response to changing circumstances), leading to more interpersonal problems. In fact, difficulties with trusting others and volatile impressions of others' moral character are often problems that result in the premature termination of a relationship. Of note, the moral inference differed: In patients with BPD, beliefs about harmful agents were more certain and less amenable to updating relative to healthy controls (Siegel, Curwell-Parry, Pearce, Saunders, & Crockett, Reference Siegel, Curwell-Parry, Pearce, Saunders and Crockett2020). For instance, when interacting with therapists within a mental health care setting, one specific focus is to build a strong therapeutic alliance. Conceivably, there are two possible outcomes: a weak therapeutic alliance will probably lead to premature treatment discontinuation – a common problem in the treatment of BPD (Barnicot, Katsakou, Marougka, & Priebe, Reference Barnicot, Katsakou, Marougka and Priebe2011). On the other hand, in the case of a strong therapeutic alliance, patients strive to avoid changes in the therapeutic setting (e.g. changing therapists due to leaves) as they often distrust other therapists – despite previous positive experiences and the fact that other therapists will probably also be kind to them. As such, this example highlights once more the lack of a suitably expressive social world model and the use of an impoverished, coarse-grained model of self and other that leads to rigidity and inflexibility in social interactions preventing a more nuanced inference about the intention of others. In line with that notion, interpersonal functioning was found to predict non-delusional paranoia in BPD (Oliva, Dalmotto, Pirfo, Furlan, & Picci, Reference Oliva, Dalmotto, Pirfo, Furlan and Picci2014) – some type of non-delusional paranoia was reported by 87% in a BPD sample (Zanarini, Frankenburg, Wedig, & Fitzmaurice, Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg, Wedig and Fitzmaurice2013).

Impulsivity

BPD is also characterized by a variety of impulsive behaviors, such as promiscuity and substance abuse. The most prominent example of such behaviors, which aim at reducing emotional tension, is non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). According to PP, such impulsive behaviors may seek to resolve uncertainty: if intense aversive emotions reflect the prediction of unpredictability (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Watson and Friston2018), any behavior aimed at reducing such intense aversive emotional states may convey a sense of control. In other words, people with BPD have learnt that certain behaviors, such as NSSI, lower their emotional tension, thereby increasing the certainty of the consequences of action.

In our account, impulsive behavior (such as NSSI) is considered more as a consequence of affective instability. In fact, NSSI may be reinforced by its affect stabilization function (Vansteelandt et al., Reference Vansteelandt, Houben, Claes, Berens, Sleuwaegen, Sienaert and Kuppens2017). In line, a recent study showed that affective instability was significantly greater in adolescents engaging in NSSI, and the number of BPD criteria met was positively correlated with affective instability in the NSSI group (Santangelo et al., Reference Santangelo, Koenig, Funke, Parzer, Resch, Ebner-Priemer and Kaess2017). Particularly, higher levels of momentary negative affect predicted greater subsequent urges to self-injure, but only when self-concept clarity was low, supporting interactive effects (Scala et al., Reference Scala, Levy, Johnson, Kivity, Ellison, Pincus and Newman2018). Remarkably, impulsivity as a personality trait per se is genetically influenced and heritable (Balestri, Calati, Serretti, & de Ronchi, Reference Balestri, Calati, Serretti and de Ronchi2014; Bevilacqua & Goldman, Reference Bevilacqua and Goldman2013; Bezdjian, Baker, & Tuvblad, Reference Bezdjian, Baker and Tuvblad2011; Fineberg et al., Reference Fineberg, Chamberlain, Goudriaan, Stein, Vanderschuren, Gillan and Potenza2014a; Khadka et al., Reference Khadka, Narayanan, Meda, Gelernter, Han, Sawyer and Pearlson2014).

The basic assumptions of the PP account of BPD are displayed in Fig. 2.

Neural specification of this account

Contemporary etiological theories of BPD assume that biological predispositions (i.e. genetic factors) are potentiated by environmental risk factors (i.e. CM). Studies estimating the heritability of the basic dimensions of personality disorders report approximately between 35% and 56% (Jang, Livesley, Vernon, & Jackson, Reference Jang, Livesley, Vernon and Jackson1996; Livesley, Jang, Jackson, & Vernon, Reference Livesley, Jang, Jackson and Vernon1993). Twin and family studies estimated a moderate to high heritability in BPD indicating a general genetic risk factor, but highlight also individually unique environmental influences (Distel et al., Reference Distel, Trull, Derom, Thiery, Grimmer, Martin and Boomsma2008, Reference Distel, Willemsen, Ligthart, Derom, Martin, Neale and Boomsma2010; Skoglund et al., Reference Skoglund, Tiger, Rück, Petrovic, Asherson, Hellner and Kuja-Halkola2021). Indeed, results from a longitudinal discordant twin design show that there might be a genetic influence underlying the association of traumatic events with BPD, rather than BPD being directly caused by a trauma (Bornovalova et al., Reference Bornovalova, Huibregtse, Hicks, Keyes, McGue and Iacono2013). Likely contributing biological factors include genes linked to dopamine, serotonin, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and neuropeptides (Steele & Siever, Reference Steele and Siever2010). Research points to abnormalities in the dopamine system in people with BPD (Friedel, Reference Friedel2004; Oquendo & Mann, Reference Oquendo and Mann2000). The efficacy of dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) blocking antipsychotic drugs in BPD treatment also suggests the involvement of the dopamine system in the neurobiology of BPD (Nemoda et al., Reference Nemoda, Lyons-Ruth, Szekely, Bertha, Faludi and Sasvari-Szekely2010). Moreover, dopamine transporter (DAT1) gene variants increase the risk of BPD (Amad, Ramoz, Thomas, Jardri, & Gorwood, Reference Amad, Ramoz, Thomas, Jardri and Gorwood2014; Joyce, Stephenson, Kennedy, Mulder, & McHugh, Reference Joyce, Stephenson, Kennedy, Mulder and McHugh2013). This crucial role of dopamine is well in line with the PP account of BPD, because in PP dopamine is thought to encode the precision of beliefs that underwrite choices and behavior (Schwartenbeck, FitzGerald, Mathys, Dolan, & Friston, Reference Schwartenbeck, FitzGerald, Mathys, Dolan and Friston2015), and dopamine has been shown to modulate belief updating (Sharot et al., Reference Sharot, Guitart-Masip, Korn, Chowdhury and Dolan2012). Drawing on this previous work, we suggest that the increased integration of negative social feedback in BPD corresponds to enhanced levels of dopamine in the respective synaptic gains, accounting for the increased use of that information to update the prior prediction. Computationally, this is associated with high precision with which new information is encoded.

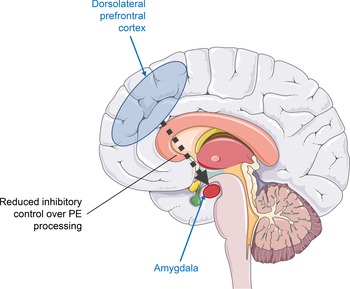

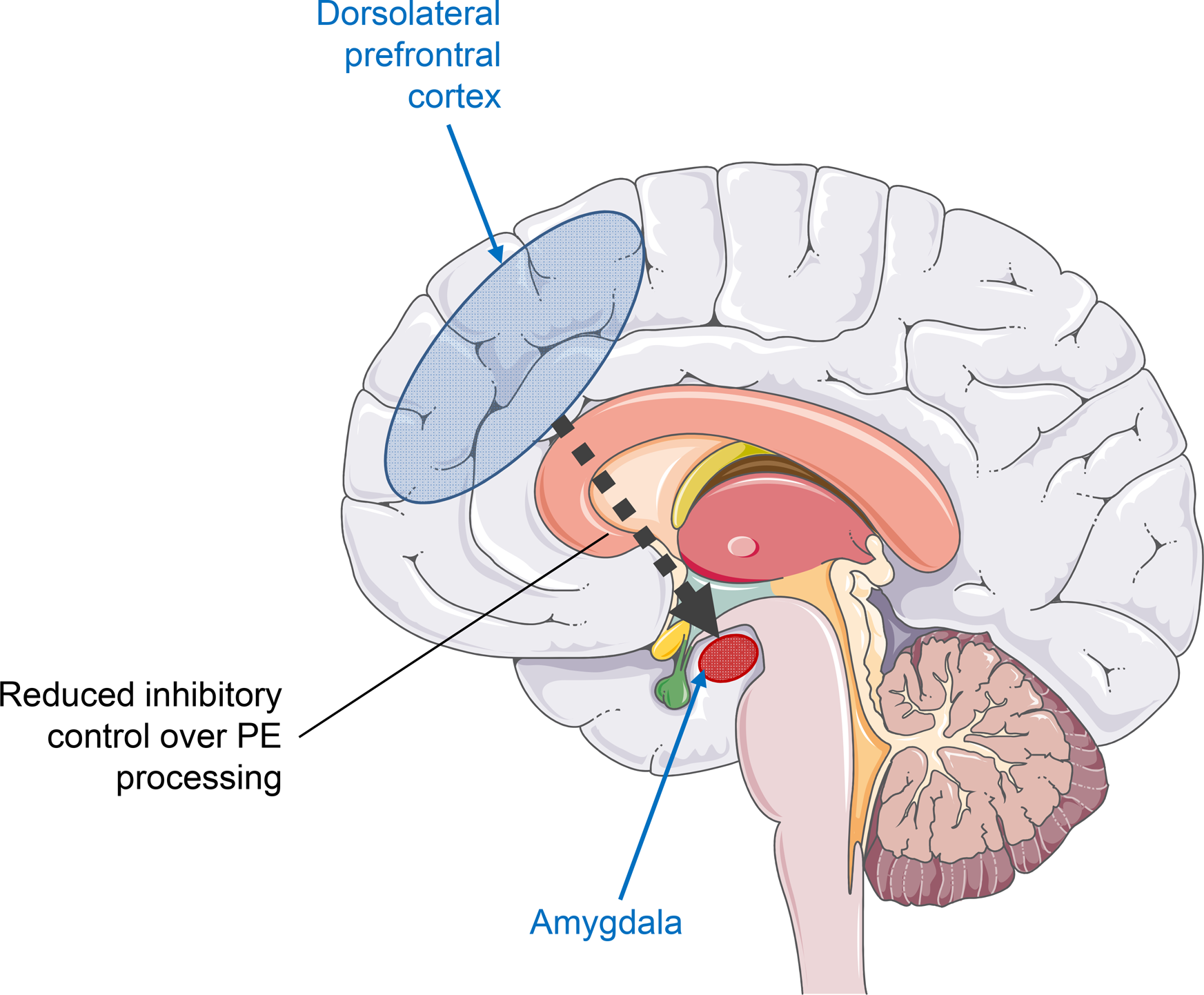

Another psychobiological mechanism that might be involved in the psychopathology of BPD refers to the connectivity of different brain areas. Specifically, the increased integration of negative social feedback in BPD might be related to a reduced inhibitory control of the prefrontal cortex (PFC) in PE processing. In particular, previous research has shown that PE processing in the reward system (i.e. ventral striatum) can be suppressed by the PFC, resulting in a lack of belief updating, as demonstrated for pain perception (Schenk, Sprenger, Onat, Colloca, & Büchel, Reference Schenk, Sprenger, Onat, Colloca and Büchel2017) and reward processing in depression (Greenberg et al., Reference Greenberg, Chase, Almeida, Stiffler, Zevallos, Aslam and Phillips2015). More specifically, research in the neuronal coding of PE (Schultz & Dickinson, Reference Schultz and Dickinson2000) has indicated that neurons in the dorsolateral prefrontal, orbitofrontal, and anterior cingulate cortex are activated in relation to errors in the prediction of reward (Niki & Watanabe, Reference Niki and Watanabe1979; Watanabe, Reference Watanabe1989), and these PEs are processed in combination with neurons in the striatum that code rewards relative to their unpredictability (Apicella, Legallet, & Trouche, Reference Apicella, Legallet and Trouche1997) and neurons in the amygdala signaling reward-predicting stimuli (Nishijo, Ono, & Nishino, Reference Nishijo, Ono and Nishino1988). Drawing on this work, we suggest that in BPD, the PFC might fail to execute inhibitory control over the processing of PEs from social feedback, thereby contributing to its increased integration.

Furthermore, research has focused on the neural base of distorted affective processing in BPD as supported by five meta-analytic reviews (de-Almeida et al., Reference de-Almeida, Wenzel, de-Carvalho, Powell, Araújo-Neto, Quarantini and de-Oliveira2012; Mitchell, Dickens, & Picchioni, Reference Mitchell, Dickens and Picchioni2014; Rodrigues et al., Reference Rodrigues, Wenzel, Ribeiro, Quarantini, Miranda-Scippa, de Sena and De Oliveira2011; Ruocco, Amirthavasagam, & Zakzanis, Reference Ruocco, Amirthavasagam and Zakzanis2012; Ruocco, Amirthavasagam, Choi-Kain, & McMain, Reference Ruocco, Amirthavasagam, Choi-Kain and McMain2013). In this line of (mostly fMRI) research, investigators have examined how people with BPD and healthy participants process negative emotional stimuli relative to neutral stimuli. Taken together, such neuroimaging studies suggest that dysfunctional fronto-limbic brain regions underlie the emotional dysregulation in BPD (Krause-Utz, Winter, Niedtfeld, & Schmahl, Reference Krause-Utz, Winter, Niedtfeld and Schmahl2014). Specifically, individuals with BPD showed structural and functional abnormalities in a fronto-limbic network including regions involved in emotion processing (e.g. amygdala, insula) and frontal brain regions implicated in regulatory control processes (e.g. anterior cingulate cortex, medial frontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and dorsolateral PFC) (Krause-Utz et al., Reference Krause-Utz, Winter, Niedtfeld and Schmahl2014).

In line with the assumption of BPD as an emotion dysregulation disorder, a more recent multimodal meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies synthesized that BPD is related to abnormal activation of dorsolateral prefrontal and limbic brain regions (Hazlett, Reference Hazlett2016; Schulze, Schmahl, & Niedtfeld, Reference Schulze, Schmahl and Niedtfeld2016). In particular, BPD patients showed an increased activation of the left amygdala and posterior cingulate cortex, along with debilitated responses of the bilateral dorsolateral PFC while processing negative emotional stimuli. Interestingly, the functional corticolimbic connectivity, in particular between the right amygdala and right dorsolateral PFC, mediates the relationship between childhood adversities and symptom severity in BPD (Vai et al., Reference Vai, Sforzini, Visintini, Riberto, Bulgarelli, Ghiglino and Benedetti2018). Another fMRI study (Scherpiet et al., Reference Scherpiet, Brühl, Opialla, Roth, Jäncke and Herwig2014) found abnormalities not only in the perception but also in the anticipation of negative emotional stimuli. Collectively, this line of research is well in line with the PP account of BPD in that it provides neural evidence for the hypothesis BPD is related to the anticipation of negative events and experiences, increasing the likelihood of actually experiencing intense negative emotions, which is reflected by abnormal activity in fronto-limbic networks.

Although depending on the type, frequency and timing of exposure, CM has an influence on the child brain development with functional and structural changes observed even decades later in adulthood (Jedd et al., Reference Jedd, Hunt, Cicchetti, Hunt, Cowell, Rogosch and Thomas2015): Associations between CM and brain structures have been widely documented with the most frequent alterations related to CM in the function and structure of lateral and ventromedial fronto-limbic brain areas and neural networks (i.e. deficits in structural interregional connectivity) that mediate behavioral, cognitive and affect control (Hart & Rubia, Reference Hart and Rubia2012; Lim, Radua, & Rubia, Reference Lim, Radua and Rubia2014). In particular, CM is related to a reduced volume of the (adult) hippocampus (Paquola, Bennett, & Lagopoulos, Reference Paquola, Bennett and Lagopoulos2016; Teicher, Anderson, & Polcari, Reference Teicher, Anderson and Polcari2012), anterior cingulate and ventromedial and dorsallateral prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortices, as well as to the development of the corpus callosum (Teicher & Samson, Reference Teicher and Samson2016; Teicher, Samson, Anderson, & Ohashi, Reference Teicher, Samson, Anderson and Ohashi2016). Moreover, a review of fMRI studies found that CM is associated with altered functioning in a range of neurocognitive systems (i.e. threat processing, reward processing, emotion regulation and executive control) (McCrory, Gerin, & Viding, Reference McCrory, Gerin and Viding2017). In fact, an association was found with an enhanced amygdala response to threatening stimuli (Dannlowski et al., Reference Dannlowski, Stuhrmann, Beutelmann, Zwanzger, Lenzen, Grotegerd and Kugel2012), reduced ventral striatal response to the anticipation or receipt of reward, decreased connectivity between prefrontal regions and the amygdala, and increased volume and network centrality of the precuneus (Teicher et al., Reference Teicher, Samson, Anderson and Ohashi2016). In line with research on CM and brain alterations, a PET study showed a correlation between a dysfunction of the dorsolateral and medial PFC (including anterior cingulate) with the recall of CM specifically in BPD (Schmahl, Vermetten, Elzinga, & Bremner, Reference Schmahl, Vermetten, Elzinga and Bremner2004). Indeed, CM is associated with structural impairment in the (right) ventrolateral PFC and aggressiveness in patients with BPD (Morandotti et al., Reference Morandotti, Dima, Jogia, Frangou, Sala, de Vidovich and Brambilla2013). Further, some researchers found a hypoconnectivity between structures associated with emotion regulation and structures associated with social cognitive responses in BPD: Higher levels of CM were associated with reduced levels of brain connectivity, with different types of CM having differential effects on connectivity in BPD patients (Duque-Alarcón, Alcalá-Lozano, González-Olvera, Garza-Villarreal, & Pellicer, Reference Duque-Alarcón, Alcalá-Lozano, González-Olvera, Garza-Villarreal and Pellicer2019). In support of our account of CM, there is some evidence for complex gene-environment interactions involving CM that determine the risk or protection against BPD pathology (Goodman, New, & Siever, Reference Goodman, New and Siever2004). Indeed, CM impacts biological processes epigenetically (Prados et al., Reference Prados, Stenz, Courtet, Prada, Nicastro, Adouan and Perroud2015). Providing evidence of epigenome × environment interactions, epigenetic modifications of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (i.e. hGR methylation) were strongly associated with an increased vulnerability to psychopathology in CM (Radtke et al., Reference Radtke, Schauer, Gunter, Ruf-Leuschner, Sill, Meyer and Elbert2015). More and more evidence points to a severe relationship dysfunction being the core epigenetic expression of BPD (Steele & Siever, Reference Steele and Siever2010).

On a hormone level, early CM was associated with reduced plasma oxytocin (Kluczniok et al., Reference Kluczniok, Dittrich, Hindi Attar, Bödeker, Roth, Jaite and Bermpohl2019), highlighting the role of oxytocin in BPD (Herpertz & Bertsch, Reference Herpertz and Bertsch2015). In the pathogenesis of BPD, a beneficial effect of oxytocin on threat processing and stress responsiveness was found (Bertsch & Herpertz, Reference Bertsch, Herpertz, Hurlemann and Grinevich2018), despite considerable heterogeneity in the literature (Amad, Thomas, & Perez-Rodriguez, Reference Amad, Thomas and Perez-Rodriguez2015; Bertsch & Herpertz, Reference Bertsch, Herpertz, Hurlemann and Grinevich2018).

The neural specification of our PP account of BPD is displayed in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Neural specification of the predictive processing account of BPD.

Novelty of this account

The present article is the first to apply current thinking in neuroscience and computational psychiatry to provide a novel mechanistic model of BPD. Specifically, by highlighting how the experience of CM is thought to alter perception, our account provides a coherent explanation as to why people with BPD show rapid fluctuations of intense emotions, cognitions, and inconsistent behaviors. Moreover, proposing that CM leads to a dysbalance between the precision of prior beliefs and data, our account can also explain why people with BPD are highly sensitive to negative social feedback, whereas information processing in other domains is intact. Thus, in contrast to previous cognitive theories of BPD (Arntz, Reference Arntz1994; Arntz, Dietzel, & Dreessen, Reference Arntz, Dietzel and Dreessen1999; Arntz, Dreessen, Schouten, & Weertman, Reference Arntz, Dreessen, Schouten and Weertman2004; Baer, Peters, Eisenlohr-Moul, Geiger, & Sauer, Reference Baer, Peters, Eisenlohr-Moul, Geiger and Sauer2012; Beck, Davis, & Freeman, Reference Beck, Davis and Freeman2015; Butler, Brown, Beck, & Grisham, Reference Butler, Brown, Beck and Grisham2002), we suggest that BPD may not primarily be related to the presence of dysfunctional beliefs per se (i.e. their contents), but to aberrant precision afforded to them. This is consistent with recent theories from computational psychiatry (Kube & Rozenkrantz, Reference Kube and Rozenkrantz2021; Paulus et al., Reference Paulus, Feinstein and Khalsa2019). Moreover, our account goes beyond previous theories of BPD as a disorder of emotion regulation (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993) by assuming that the instability of affect, cognition, and behavior has one underlying pathology, that is, overly weak prior predictions. At the same time, our model can also account for the rigidity (or: lack of flexibility) of BPD patients by conceiving of it as an expression of the patients' impoverished generative model resulting from CM.

Implications for the treatment and prevention of BPD

On the basis of our review, two major clinical implications can be drawn. First, the crucial role of CM on the perception and cognition of a child and its emotional development. People generate a model of its environment (including the external world and the body) which predicts future sensory inputs and is updated by PEs, depending on how precise these error signals are. Expectation and attention increase the integration of top-down and bottom-up signals in perception (Gordon, Tsuchiya, Koenig-Robert, & Hohwy, Reference Gordon, Tsuchiya, Koenig-Robert and Hohwy2019). Interventions focusing on both enhancing sensitivity to the validity of sensory input/evidence and therefore PE; and attention on expectations v. sensory input to disentangle imbalance might be promising treatment approaches. In general, individuals tend to have an optimism bias, processing desirable information more frequently than undesirable information. Findings suggest that BPD patients appear initially more pessimistic about their personal future than healthy people but they might be able to overcome their pessimism when provided with relevant information (Korn et al., Reference Korn, la Rosée, Heekeren and Roepke2016b). Indeed, optimism training has potential to change individuals with mild dysphoria perceptions about the future (Yoshimura & Hashimoto, Reference Yoshimura and Hashimoto2020). By sampling precise empirical evidence, BPD patients might enhance their predictability of the world and reduce uncertainty in their beliefs. Before, traditional cognitive techniques such as the, Downward Arrow‘-technique – sometimes referred to as Vertical Descent (Leahy, Reference Leahy2017) – might be useful to identify relevant expectations (‘predictions’). Individual treatment should then focus on techniques to increase the attention of BPD patients to PEs by an elevated propensity to counterbalance and weight perceptual beliefs (priors) over sensory evidence and interventions to empirically examine the credibility of one's beliefs in order to strengthen the precision of one's priors and enhance belief updating. Attention alters PP indicating that there are top-down effects of attention on perception (Clark, Reference Clark2016b). Some researchers have proposed that salience is something that is afforded to actions that realize epistemic affordance, while attention per se is afforded to precise sensory evidence – or beliefs about the causes of sensations (Parr & Friston, Reference Parr and Friston2017). Indeed, attention and PE suggest that information sought by top-down-attention is prioritized (Ramamoorthy, Parker, Plaisted-Grant, Muhl-Richardson, & Davis, Reference Ramamoorthy, Parker, Plaisted-Grant, Muhl-Richardson and Davis2020). Attention optimizes the expected precision of predictions by modulating the synaptic gain of PE units, that is, attention increases the selectivity for mismatch information in the neural response to a surprising stimulus indicating that attention optimizes precision expectations during hierarchical inference by increasing the gain of PEs (Smout, Tang, Garrido, & Mattingley, Reference Smout, Tang, Garrido and Mattingley2019). Furthermore, it is widely accepted that predictions across different stimulus attributes (e.g. time and content) facilitate sensory processing. Content (‘what’) and temporal (‘when’) predictions engage complementary neural mechanisms in different brain regions, suggesting domain-specific prediction signaling along the cortical hierarchy (Auksztulewicz et al., Reference Auksztulewicz, Schwiedrzik, Thesen, Doyle, Devinsky, Nobre and Melloni2018). Moreover, as BPD patients perceive the world as ambiguous, building new expectations should be based on repetitions and hints which have been shown to facilitate perceptual experience of ambiguous images (Hertz, Blakemore, & Frith, Reference Hertz, Blakemore and Frith2020). Yet, people have two main pathways to determine the veracity of the sensory input: the perceived credibility of the source and direct-evaluation via first-hand evidence, i.e. testing the advice against observation. Beliefs are interpreted in light of the perceived credibility of the source in form of credibility-led biased interpretations of evidence (whether belief or suspicion confirming) that lead to further polarization of the perceived credibility highlighting the crucial role of credibility in belief updating (Pilditch, Madsen, & Custers, Reference Pilditch, Madsen and Custers2020), while cues including valence and relevance influence these credibility judgments suggesting a utility and credibility trade off during decision making (Gugerty & Link, Reference Gugerty and Link2020). Therefore, creating a more nuanced credibility picture in BPD patients might also be promising treatment target. By providing the brain with an intense inflow of salient and unambiguous bottom-up sensory input to shift the brains mapping of the observed body state, interoceptive interventions might provide a base for more directly targeting and manipulating those (attentional) processes regarding the interoceptive system and correcting somatic errors (Paulus et al., Reference Paulus, Feinstein and Khalsa2019) that also might foster ‘mineness’ (also called ‘subjective presence’ or ‘personalization’) as the feeling that experiences belong to a continuing self (Gerrans, Reference Gerrans2020). As such, exposure-based interventions (including exteroceptive as well as interoceptive exposure techniques) are useful to exacerbate somatic errors and therefore to adaptively adjust their prior expectations with new sensory input (evidence). As a slightly different approach to process aversive interoceptive sensations, mindfulness techniques as used as a central part in DBT might help minimize somatic errors by shifting attention away from the predicted body state and toward the observed body state (Farb et al., Reference Farb, Daubenmier, Price, Gard, Kerr, Dunn and Mehling2015), i.e. predictions of the body state and somatic error might naturally vanish as the mind attempts to function with low-precision priors triggering fewer regulatory responses and that allows the entire predictive model to be driven by incoming sensory input from the present moment in time. Traditionally not a standard tool in psychotherapy, new interventions such as the floatation-REST (Reduced Environmental Stimulation Therapy)Footnote 4 might be able to enrich current state-of-the-art treatments such as DBT (Feinstein et al., Reference Feinstein, Khalsa, Yeh, al Zoubi, Arevian, Wohlrab and Paulus2018). Furthermore, whole body hyperthermia (WBH) (Janssen et al., Reference Janssen, Lowry, Mehl, Allen, Kelly, Gartner and Raison2016), modulation of muscle tension via Swedish massage (Rapaport et al., Reference Rapaport, Schettler, Larson, Edwards, Dunlop, Rakofsky and Kinkead2016), yoga (Jeter, Slutsky, Singh, & Khalsa, Reference Jeter, Slutsky, Singh and Khalsa2015), and exercise (Smits, Berry, Tart, & Powers, Reference Smits, Berry, Tart and Powers2008); repeated brief exposures to high doses of CO2 (Wolpe, Reference Wolpe1987); and cyclic activation of the sympathetic nervous system and suppression of the immune response through cold immersion and CO2-modulation using alternating cycles of hyperventilation followed by breath holding (Kox et al., Reference Kox, Van Eijk, Zwaag, Van Den Wildenberg, Sweep, Van Der Hoeven and Pickkers2014) might also yield a future potential in this regard (Paulus et al., Reference Paulus, Feinstein and Khalsa2019).

Second, this account highlights the role of prevention of CM in risk populations with low educational skills, and in parents suffering also from mental disorders, in particular emotion regulation deficits (such as in the case of mothers with BPD). Both, parenting programs as well as mother-child-interventions might serve as important preventive strategies to reduce the occurrence of CM. For example, in some clinics there exist group psychotherapy for mothers suffering from BPD, and evidence-based parenting programs such as the Triple p – Positive Parenting Program (Bodenmann, Cina, Ledermann, & Sanders, Reference Bodenmann, Cina, Ledermann and Sanders2008; Sanders, Reference Sanders1999, Reference Sanders2008, Reference Sanders2012). In a critical and sensitive phase in child development, children must be encouraged to build appropriate confidence (i.e. precision) in their expectations and beliefs (i.e. priors) by a validating environment that see their emotions and fulfill their needs appropriately leading to fewer PEs (i.e. minimizing uncertainty and surprise in the environment to make the world and behavior of others more predictable to them).

Limitations and future directions

Although the majority of patients with BPD report maltreatment in their childhood (Battle et al., Reference Battle, Shea, Johnson, Yen, Zlotnick, Zanarini and Morey2004; Carlson et al., Reference Carlson, Egeland and Sroufe2009) and patients with BPD were over 13 times more likely to report childhood adversity than non-clinical controls and other clinical populations (Kleindienst et al., Reference Kleindienst, Vonderlin, Bohus and Lis2020; Porter et al., Reference Porter, Palmier-Claus, Branitsky, Mansell, Warwick and Varese2020), a major limitation of our model is that it only explains aberrant belief updating in patients with BPD that have experienced some sort of CM. For BPD patients without CM in the past, genetics might be a more relevant risk factor in the pathogenesis of BPD as studies found a moderate to high heritability in BPD (Distel et al., Reference Distel, Trull, Derom, Thiery, Grimmer, Martin and Boomsma2008, Reference Distel, Willemsen, Ligthart, Derom, Martin, Neale and Boomsma2010; Skoglund et al., Reference Skoglund, Tiger, Rück, Petrovic, Asherson, Hellner and Kuja-Halkola2021). However, despite the potentially different etiology, we believe that a similar psychobiological pathology in the sense of PP (i.e. the role of priors, precision and likelihood) underlies also in those patients with BPD. Furthermore, although particularly relevant in BPD (Brakemeier et al., Reference Brakemeier, Dobias, Hertel, Bohus, Limberger, Schramm and Normann2018; Pietrek et al., Reference Pietrek, Elbert, Weierstall, Müller and Rockstroh2013; Quenneville et al., Reference Quenneville, Kalogeropoulou, Küng, Hasler, Nicastro, Prada and Perroud2020; Wota et al., Reference Wota, Byrne, Murray, Ofuafor, Nisar, Neuner and Hallahan2014), CM is considered as a transdiagnostic factor (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson2009; Struck et al., Reference Struck, Krug, Yuksel, Stein, Schmitt, Meller and Brakemeier2020) and future studies should investigate the specific causal contribution of CM to the pathogenesis of BPD. Though our account can build upon the wealth of literature on childhood adversities, no consensus has been reached about how to measure poor parenting or the invalidating environment to quantify the extent to which these types of specific factors contribute to BPD (Musser et al., Reference Musser, Zalewski, Stepp and Lewis2018). Also, different forms of CM may have different consequences. Similarly, there is a lack of assessment tools to measure a key element of our account: the precision of prior beliefs and new information. Therefore, much of what we proposed here as conceptually-based evidence still needs to be empirically tested in future work using rigorous experimental designs and computational modeling to generate data-based evidence.

Despite strong arguments in favor of PP (Seth, Millidge, Buckley, & Tschantz, Reference Seth, Millidge, Buckley and Tschantz2020; van de Cruys, Friston, & Clark, Reference van de Cruys, Friston and Clark2020), it should be noted there have also been some critical voices regarding PP as a ‘theory-of-everything’ (Hutto, Reference Hutto2020; Litwin & Miłkowski, Reference Litwin and Miłkowski2020; Sun & Firestone, Reference Sun and Firestone2020). Indeed, there seem overlapping features and similarities to traditional theories (F.A. França, Reference F.A. França2020) and some researchers urge for refinements of the PP theory in order to increase its explanatory power (Gilead, Trope, & Liberman, Reference Gilead, Trope and Liberman2020; Vilas, Melloni, & Melloni, Reference Vilas, Melloni and Melloni2020). This critique is in part also relevant to the present article as it applies one set of theoretical assumptions to explain a fairly heterogeneous disorder. Yet, we believe that PP has the potential to inspire future research and allows to derive some novel hypotheses about the psychopathology of BPD that may contribute to a more nuanced understanding of this complex disorder, particularly in view of the developmental psychopathology perspective PP offers.

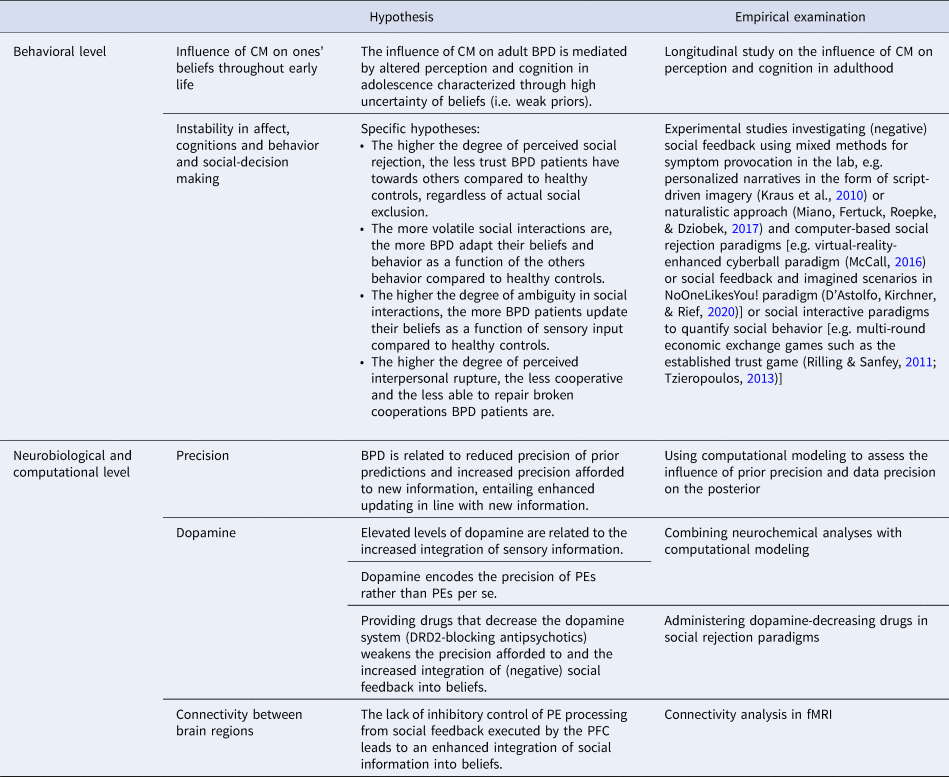

For an overview of specific hypotheses that can be derived from our account, see Table 1.

Table 1. Testable hypotheses for future research

Note: BPD, Borderline personality disorder; CM, Childhood maltreatment; PE, prediction error; PFC, prefrontral cortex.

Conclusions

In this article, we proposed a Bayesian account of BPD that relies on the observation that many people with BPD experienced some sort of maltreatment in childhood. We argued that such adverse experiences lead to pervasive alterations in perception. In essence, we suggested that CM impairs the continuous refinement of predictive models of the world and precipitates the formation of weak and strong prior predictions, relative to sensory information. This entails a distorted belief updating in response to novel information, resulting in a marked instability of affect, cognitions, and behavior – that is, the core features of BPD.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722002458.

Acknowledgements

Figure 3 was created using a template from Servier Medical Art by Servier (http://smart.servier.com/), licensed under a Creative Common Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Author contributions

P. H. conceived the main original ideas. All authors contributed to the development of the theoretical concept and design of the model. P. H. drafted the paper, and T. K. and E. F. provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final version of the paper for submission.

Financial support

E. F. obtained funding from the Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (2018_A152). This research did not receive any other specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

E. F. has provided trainings, presentations and published books/chapters on the treatment of BPD. P. H. and T. K. have no conflicts of interest to declare.