Introduction

Variation in parenting is an important risk or protective factor associated with the development of child psychopathology (McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Weisz and Wood2007). While shared genetic factors explain the association between parenting and psychopathology in part (Kendler, Reference Kendler1996), environmental influences of parenting have also been demonstrated in families in which parents and children are not genetically related (Bornovalova et al., Reference Bornovalova, Cummings, Hunt, Blazei, Malone and Iacono2014). We focus here on parental warmth (McLeod, Weisz, et al., Reference McLeod, Weisz and Wood2007), and aversive or inconsistent (Yap et al., Reference Yap, Pilkington, Ryan and Jorm2014) parenting, which are among the most widely investigated indicators of adaptive and maladaptive parenting, respectively (McLeod et al., Reference McLeod, Weisz and Wood2007; Yap et al., Reference Yap, Pilkington, Ryan and Jorm2014).

Most studies examining associations between parenting and child psychopathology focus on two dimensions of child psychopathology: internalizing (anxiety, depression, and sometimes somatic problems) and externalizing (disruptive and antisocial behavior; Achenbach & Edelbrock, Reference Achenbach and Edelbrock1978, Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017a; Reference Pinquart2017b). For example, in clinical and community samples, greater parental warmth is associated with less child externalizing and internalizing problems, whereas aversive and inconsistent parenting are associated with more child externalizing and internalizing problems (Pinquart, 2017a; 2017b; Rothenberg et al., Reference Rothenberg, Lansford, Alampay, Al-Hassan, Bacchini, Bornstein, … and Yotanyamaneewong2020). However, externalizing and internalizing problems are frequently comorbid (Boylan et al., Reference Boylan, Vaillancourt, Boyle and Szatmari2007; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Biederman, Zerwas, Monuteaux, Goring and Faraone2002); therefore, examining them separately may miss opportunities to identify the ways in which parenting is related to children’s overall liability for psychopathology.

Parenting is also associated with processes relevant across the spectrum of psychopathology (Wood et al., Reference Wood, McLeod, Sigman, Hwang and Chu2003), such as emotion regulation (Aldao et al., Reference Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema and Schweizer2010; Carver et al., Reference Carver, Johnson and Timpano2017). For example, when children show intense negative emotional responses to change or limits, they may evoke aversive parental reactions that intensify their negative emotions, and inconsistent parenting that negatively reinforces emotion dysregulation (Scaramella & Leve, Reference Scaramella and Leve2004). In contrast, warm parenting may support emotion regulation by reinforcing children seeking out parental support, contributing to the socialization of adaptive emotion regulation strategies (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Benson and Pérez-Escoda2014). Therefore, parenting may be associated with child psychopathology through unique processes related to externalizing and internalizing problems (Ballash et al., Reference Ballash, Leyfer, Buckley and Woodruff-Borden2006; Patterson, Reference Patterson1986), and through processes associated with broad liability for psychopathology (Fraire & Ollendick, Reference Fraire and Ollendick2013; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Moore, Kaczkurkin and Zald2021).

Dimensional models of psychopathology

Consistent with the high rates of comorbidity across internalizing and externalizing disorders (Angold et al., Reference Angold, Costello and Erkanli1999; Boylan et al., Reference Boylan, Vaillancourt, Boyle and Szatmari2007; Greene et al., Reference Greene, Biederman, Zerwas, Monuteaux, Goring and Faraone2002), internalizing and externalizing problems appear to share underlying processes and risk factors, such as emotion dysregulation and negative emotionality (Beauchaine & Zisner, Reference Beauchaine and Zisner2017; Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poulton and Moffitt2014; Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt2018; Haltigan et al., Reference Haltigan, Aitken, Skilling, Henderson, Hawke, Battaglia, Strauss, Szatmari and Andrade2018; Pesenti-Gritti et al., Reference Pesenti-Gritti, Spatola, Fagnani, Ogliari, Patriarca, Stazi and Battaglia2008). A general psychopathology factor, which accounts for variance in symptoms across the spectrum of psychopathology (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poulton and Moffitt2014; Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt2018; Haltigan et al., Reference Haltigan, Aitken, Skilling, Henderson, Hawke, Battaglia, Strauss, Szatmari and Andrade2018; Kotov et al., Reference Kotov, Krueger, Watson, Achenbach, Althoff, Bagby, … and Zimmerman2017; Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015; Patalay et al., Reference Patalay, Fonagy, Deighton, Belsky, Vostanis and Wolpert2015) has been proposed in response to the high rates of co-occurrence among psychiatric disorders and the many shared factors underlying disorders across the spectrum of psychopathology. One way that such a general psychopathology factor has been represented is through bifactor models (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poulton and Moffitt2014). Bifactor models consist of a latent general psychopathology factor, on which all items/symptoms load, along with two or more specific factors reflecting variance in certain domains of psychopathology (e.g., internalizing and externalizing) once overall psychopathology has been taken into account (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poulton and Moffitt2014; Haltigan et al., Reference Haltigan, Aitken, Skilling, Henderson, Hawke, Battaglia, Strauss, Szatmari and Andrade2018). For clarity, we use the term “specific” throughout to describe these residual latent psychopathology factors that remain once variance due to the general psychopathology factor has been accounted for in a bifactor model.

Bifactor models may be useful for understanding associations between parenting and psychopathology because they separate general and specific dimensions of psychopathology, making it possible to parse general correlates of psychopathology from factors associated with the presence of symptoms in specific domains (Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Moore, Kaczkurkin and Zald2021). By examining how general and specific psychopathology dimensions are associated with risk and protective factors, such as parenting, in community samples, we may be able to identify the most salient targets to be tested in early intervention clinical trials (Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Rapee and Krueger2019). That is, future early intervention trials targeting those parenting dimensions associated with a general psychopathology factor may be the most efficient way to decrease children’s overall risk for mental health problems.

The few studies that have examined parenting in relation to the general psychopathology factor have reported small but significant negative longitudinal associations with observed positive parenting behaviors (Deutz et al., Reference Deutz, Geeraerts, Belsky, Deković, van Baar, Prinzie and Patalay2020). Significant, moderate associations between harsh parenting (a measure that goes beyond aversive parenting to also include physical discipline) and higher levels of child general psychopathology have been found in cross-sectional (Waldman et al., Reference Waldman, Poore, van Hulle, Rathouz and Lahey2016) but not longitudinal studies (Deutz et al., Reference Deutz, Geeraerts, Belsky, Deković, van Baar, Prinzie and Patalay2020). For the specific psychopathology factors, significant cross-sectional associations between harsh parenting and specific externalizing (moderate effect) and internalizing problems (small effect) have been reported (Waldman et al., Reference Waldman, Poore, van Hulle, Rathouz and Lahey2016), but longitudinal associations between overall positive or harsh parenting and specific internalizing and externalizing have been non-significant (Deutz et al., Reference Deutz, Geeraerts, Belsky, Deković, van Baar, Prinzie and Patalay2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Eisenberg, Valiente and Spinrad2016). Overall, the most consistent evidence suggests that harsher and less positive parenting are broad correlates of child psychopathology (Fraire & Ollendick, Reference Fraire and Ollendick2013; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Moore, Kaczkurkin and Zald2021), rather than being associated with specific internalizing or externalizing problems. However, previous studies have not examined associations between traditional measures of parental warmth, aversive, or inconsistent parenting and the general psychopathology factor.

Multilevel family models

Multilevel study designs, in which assessments are conducted across multiple children within the same family, offer two main benefits in the study of parenting and psychopathology. First, both the overall parenting children are exposed to in the family, as well as how they are parented relative to their siblings, are associated with differences in child psychopathology (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Jenkins, Georgiades, Cairney, Duku and Racine2004). The child-specific parenting a child receives and overall parenting in the family can be disaggregated in multilevel models by examining within- and between-family differences (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Cheung, Frampton, Rasbash, Boyle and Georgiades2009). Second, the study of parenting and child psychopathology is complicated by possible confounding variables in the family environment (McLeod, Wood, et al., Reference McLeod, Wood and Weisz2007). A confounding variable is a variable that is related to both the dependent variable (i.e., child psychopathology) and the independent variable (Tulchinsky & Varavikova, Reference Tulchinsky and Varavikova2014). For example, parents’ own psychopathology symptoms may affect their ability to respond adaptively to their child’s emotions (Breaux et al., Reference Breaux, Harvey and Lugo-Candelas2016; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson2007), increasing the likelihood that their child may develop internalizing and externalizing problems (Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Simmons, Whittle, Byrne, Yap, Sheeber and Allen2017). Parental psychopathology may also be transmitted genetically and through passive gene–environment correlations (Jaffee & Price, Reference Jaffee and Price2007). Other family-level factors, such as socioeconomic risk, are also associated with both parenting and child psychopathology (Mills-Koonce et al., Reference Mills-Koonce, Willoughby, Garrett-Peters, Wagner and Vernon-Feagans2016). Moreover, socioeconomic risk, parent psychopathology, and parenting are interrelated and interact in complex ways to influence children’s risk for psychopathology (Parra et al., Reference Parra, DuBois and Sher2006).

Multilevel analyses that include within-family parenting differences across siblings, as well as overall parenting differences between families, can reduce potential confounding effects of passive gene–environment correlations and other family-level variables, such as parental psychopathology and socioeconomic risk (D’Onofrio et al., Reference D’Onofrio, Lahey, Turkheimer and Lichtenstein2013; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Cheung, Frampton, Rasbash, Boyle and Georgiades2009; Lahey & D’Onofrio, Reference Lahey and D’Onofrio2010). Previous studies have identified differences in parenting and in child internalizing and externalizing within families based on children’s age and sex (Meunier et al., Reference Meunier, Bisceglia and Jenkins2012); therefore, it is important to include age and sex as child-level control variables when examining associations between parenting and child psychopathology (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Jenkins, Georgiades, Cairney, Duku and Racine2004).

In the current investigation, to determine the extent to which parenting has broad and specific associations with child psychopathology, we examined associations between parenting and child psychopathology in a representative community sample of children using bifactor modeling of psychopathology. We used a multilevel model including siblings in the same household, allowing us to test associations between parenting and child psychopathology after accounting for family-level differences. We expected that greater parental warmth and less aversive/inconsistent parenting would be associated with lower general psychopathology and specific externalizing and internalizing problems, with the strongest associations being with general psychopathology and specific externalizing problems.

Method

Participants

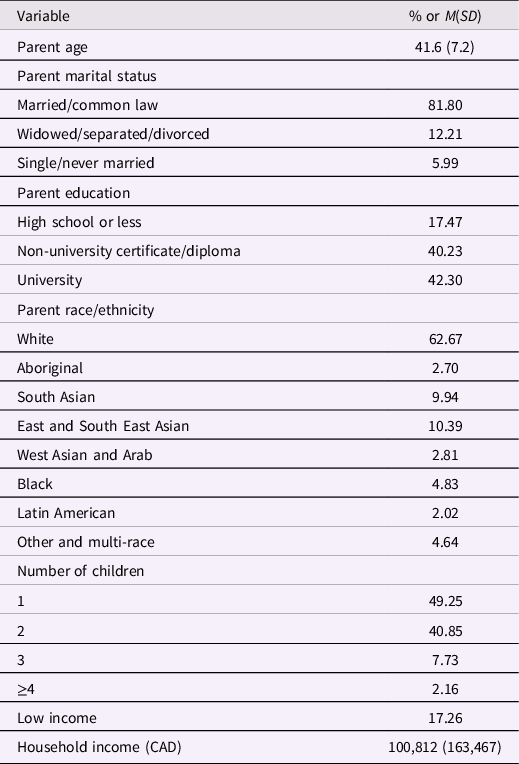

We analyzed data from the 2014 Ontario Child Health Study (OCHS), a cross-sectional epidemiological survey of children ages 4–17 (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Georgiades, Duncan, Comeau and Wang2019). In families with two or more children, a target child was randomly selected and up to three additional children in the household were included. We refer to children within the same household as siblings. The parent/caregiver most knowledgeable about the target child (referred to as parent) provided information about the household and children (see Table 1). Children (N = 10,605, Mage = 10.6 years, SD = 4.1; 51.4% male, in 6434 households) were included in the present study if they had data available on the parenting and child psychopathology measures. Excluded children (n = 197) were more likely to live in single-parent families, to have no siblings, and to have lower household income (see Supplementary Materials for details).

Table 1. Household characteristics (k = 6434)

Seventeen percent of households met criteria for low income. Most respondent parents (96%) were biological parents to the target child, female (87%), and married or living common-law (82%). Most children (72%) were living with two biological parents.

Measures

Child psychopathology

For each child in the household, the parent completed the OCHS Emotional Behavioural Scale (OCHS-EBS), measuring internalizing (27 items on generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, major depression, and social phobia) and externalizing (25 items on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder) problems in the past 6 months. Each item was rated on a 3-point scale. The OCHS-EBS has demonstrated construct validity for a 2-factor structure (internalizing and externalizing), measurement invariance across age and sex, internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and convergent validity with a diagnostic interview in the present sample (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Georgiades, Wang, Comeau, Ferro, Van Lieshout, Szatmari, Bennett, MacMillan, Lipman, Janus, Kata and Boyle2018).

Parenting

Parents completed two 5-item scales (Warmth and Aversive/Inconsistent Parenting) adapted from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (Statistics Canada, 1994) and the Parent Behavior Inventory (Lovejoy et al., Reference Lovejoy, Weis, O’Hare and Rubin1999), rating the frequency of behaviors toward each child (0 = never; 4 = always) in the past 6 months. Warmth included items such as: “I enjoy doing things with him/her” and “I listen to his/her ideas and opinions” (α = .84). Aversive/inconsistent parenting included items such as “I get angry and yell at him/her” and “I threaten punishment more often than I use it” (α = .72; r = −.24 between warmth and aversive/inconsistent parenting). Items were selected or adapted for administration in the OCHS following exploratory factor analysis across two general population surveys that included similar parenting items. For each scale (Warmth; Aversive/Inconsistent), the five items with the highest factor loadings and that showed adequate variability in responses were selected. Items were then tested by Statistics Canada in cognitive interviews with parents to ensure they were easily understandable. Any items found to be unclear were modified and retested with parents. A similar measure of parenting has previously shown significant associations with child externalizing and internalizing problems in a representative sample of Canadian children and parents (Sim & Georgiades, Reference Sim and Georgiades2022).

Covariates

Parents rated their own psychological distress in the past 30 days using the 6-item Kessler Screening Questionnaire. Each item was rated on a 5-point scale. The scale has demonstrated internal consistency and predicts mental disorder diagnoses in the general population (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Green, Gruber, Sampson, Bromet, Cuitan, … and Zaslavsky2010). Household composition and total income were reported by parents. Low income was defined as before-tax household income below the 2013 Canadian low-income level (Statistics Canada, 2015).

Procedure

Data were collected in the home from October 2014 to September 2015 (Boyle et al., 2019). Participants provided informed consent or assent. Procedures were approved by Statistics Canada. The present analysis was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Analysis

Analyses were performed using Stata 15 and Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017). Values of p < .05 were considered statistically significant. Sampling weights were applied in all analyses. We tested an orthogonal bifactor model, with a general psychopathology factor on which all items loaded, and uncorrelated specific internalizing and externalizing factors, using confirmatory factor analysis with the weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted estimator, which uses pairwise deletion for missing data (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017). Models accounted for clustering of children within households. Three competing factor models were also tested (see Supplementary Materials and Table S1). Models were evaluated by examining fit statistics and factor loadings. Reliability coefficients were calculated for factors in the orthogonal bifactor model (Dueber, Reference Dueber2017; Rodriguez et al., Reference Rodriguez, Reise and Haviland2016). Differences in the frequency of internalizing and externalizing problems have been identified across boys and girls and across childhood and adolescence (Bongers et al., Reference Bongers, Koot, Van der Ende and Verhulst2003); therefore, model fit was also tested separately by sex and age group (4–11 and 12–17 years; see Supplementary Materials).

We used multilevel modeling to estimate the association between parenting and psychopathology using saved factor scores from the orthogonal bifactor model. Separate models were run with saved factor scores for the general factor, and specific internalizing and externalizing factors, as dependent variables, including: 1) a null model with no predictors, to partition variance in psychopathology into within- and between-family components (Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Cheung, Frampton, Rasbash, Boyle and Georgiades2009); and 2) a model with average parenting at the family level, and child-specific parenting (mean centered within the family, allowing us to test the effects of the parenting a child receives relative to their family average). The robust maximum likelihood estimator was used, with full information maximum likelihood estimation to handle missing data. Models included, at the family level, parent psychological distress, number of siblings and low income, and, at the child level, age, sex, and number of biological parents at home. Continuous control variables were mean centered at the family level. Given that parenting differences and differences in the association between parenting and psychopathology have been reported across children and adolescents and boys and girls (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Dishion, Stormshak and Willett2011), interactions of parenting with child sex and age were tested. We report fully standardized beta coefficients, which are the recommended measure of effect size for multilevel models (Lorah, Reference Lorah2018).

Results

See Table S2 for descriptive statistics for continuous independent variables.

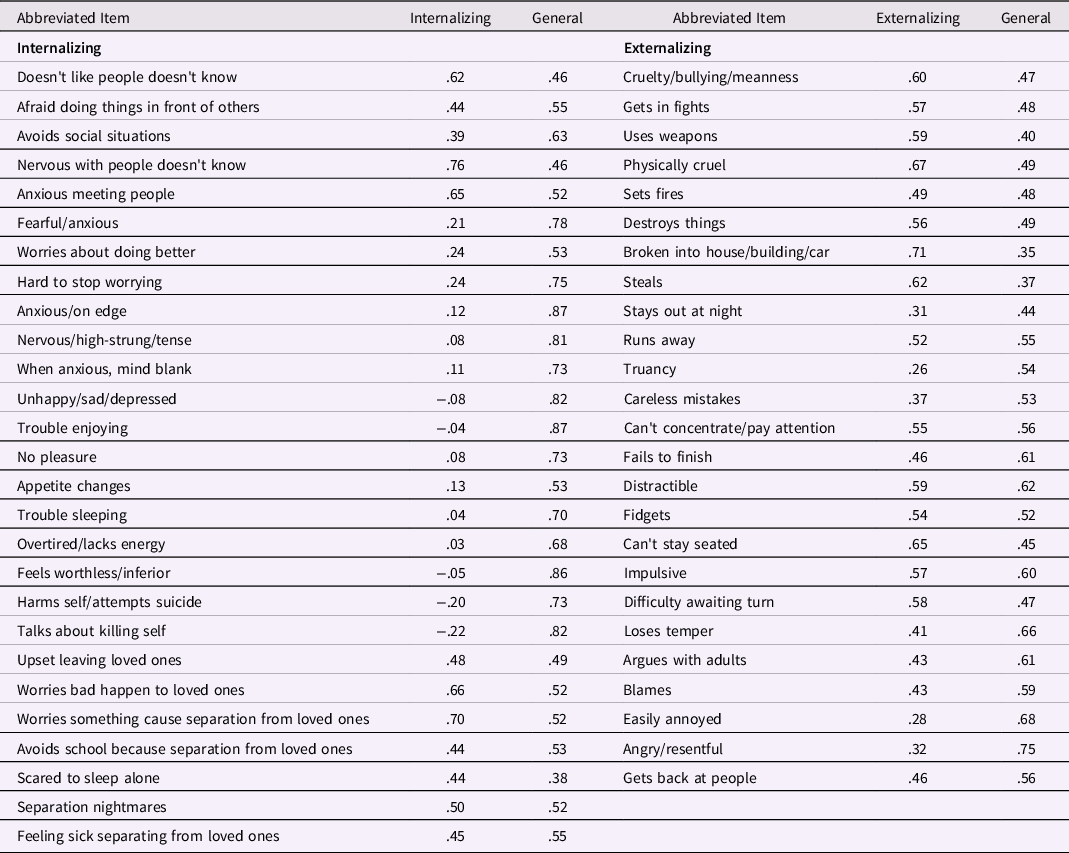

The orthogonal bifactor model fit the data well (CFI = .948, TLI = 0.943, RMSEA = .018; see Table 2). Model fit was similar in separate age and sex subgroups (see Supplementary Materials).

Table 2. Factor loadings for orthogonal bifactor model

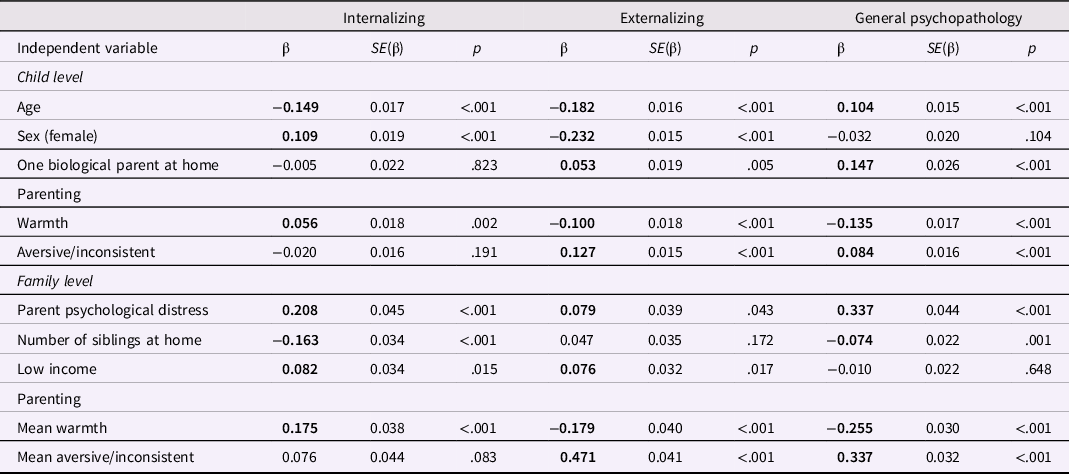

Intraclass correlation coefficients from the null models indicated the following proportions of variance at the family level: general psychopathology = .50; internalizing = .22; externalizing = .12. When family- and child-level predictors were added (see Table 3), at the family level, greater overall aversive/inconsistent parenting was associated with significantly higher general psychopathology (β = 0.34) and specific externalizing (β = 0.47), and greater overall warmth was associated with significantly lower general psychopathology (β = −0.26) and specific externalizing (β = −0.18) but higher specific internalizing (β = 0.18).

Table 3. Multilevel regressions with psychopathology factors as dependent variables (N = 10,605, K = 6434)

Note. Bold values significant at p < .05.

At the child level (see Table 3), more aversive/inconsistent parenting toward a specific child, relative to family average, was associated with significantly higher general psychopathology (β = 0.08) and specific externalizing (β = 0.13), and greater overall warmth was associated with significantly lower general psychopathology (β = −0.14) and specific externalizing (β = −0.10) but higher specific internalizing (β = 0.06). Effect sizes (standardized regression coefficients) for both warmth and aversive/inconsistent parenting at the child level were in the small range after accounting for family-level parenting and other family- and child-level control variables.

Some associations were significantly stronger in 4–11-year-olds than 12–17-year-olds (family-level warmth and aversive/inconsistent parenting with internalizing) and in girls than in boys (child-level warmth with general psychopathology and specific externalizing; and aversive/inconsistent parenting with specific externalizing; see Supplementary Materials and Tables S3–S4).

Discussion

Estimating associations between parenting and child psychopathology in cross-sectional and longitudinal studies is complicated by the presence of many potential confounding variables at the individual and at the family level (Lahey, Reference Lahey2011) and high rates of comorbidity in psychopathology symptoms (Angold et al., Reference Angold, Costello and Erkanli1999). To address these challenges, we used multilevel modeling to isolate associations at the family and at the child level separately, along with a bifactor model with a general psychopathology factor consisting of symptoms across the spectrum of psychopathology.

The general psychopathology factor has been described as measuring emotion dysregulation, negative emotionality, and unwanted irrational thoughts (Carver et al., Reference Carver, Johnson and Timpano2017; Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel, Meier, Ramrakha, Shalev, Poulton and Moffitt2014; Caspi & Moffitt, Reference Caspi and Moffitt2018; Deutz et al., Reference Deutz, Geeraerts, Belsky, Deković, van Baar, Prinzie and Patalay2020), each of which is associated with increased liability for psychopathology (Aldao et al., Reference Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema and Schweizer2010; Eisenberg et al., Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland, Spinrad, Fabes, Shepard, Reiser, Murphy, Losoya and Guthrie2001). Our analysis demonstrates that lower parental warmth and more aversive/inconsistent parenting overall in the family, and toward an individual child relative to their siblings, have broad associations with child psychopathology, as measured by the general psychopathology factor. Variance in the general psychopathology factor was equally distributed between family and child levels, suggesting that children within families show considerable similarities, as well as important differences, in general psychopathology. Family- and child-level associations between parenting and general psychopathology were significant after controlling for family-level variables, such as parent mental health, family composition, and low income.

It is important to contextualize our findings in the broader literature showing that associations between parenting and child psychopathology are bidirectional (Allmann et al., Reference Allmann, Klein and Kopala-Sibley2021; Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Rha and Park2000; Kendler, Reference Kendler1996; Lengua & Kovacs, Reference Lengua and Kovacs2005; Li et al., Reference Li, Willems, Stok, Deković, Bartels and Finkenauer2019; Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017a). Parenting may contribute to increased risk for psychopathology through behavioral, social, and relational processes (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Criss, Silk and Houltberg2017; Rothenberg et al., Reference Rothenberg, Lansford, Alampay, Al-Hassan, Bacchini, Bornstein, … and Yotanyamaneewong2020). At the same time, children’s temperament (Rothbart, Reference Rothbart2007) and behavior influence parenting (Lengua & Kovacs, Reference Lengua and Kovacs2005; Li et al., Reference Li, Willems, Stok, Deković, Bartels and Finkenauer2019; Rothenberg et al., Reference Rothenberg, Lansford, Alampay, Al-Hassan, Bacchini, Bornstein, … and Yotanyamaneewong2020; Scaramella & Leve, Reference Scaramella and Leve2004). For example, in experimental manipulations, parents behave more negatively toward children displaying more disruptive behavior (Wymbs, Reference Wymbs2011), consistent with evocative effects, in which child characteristics elicit certain parenting behaviors (Neiderhiser et al., Reference Neiderhiser, Reiss, Pedersen, Lichtenstein, Spotts, Hansson, … and Elthammer2004). Our results are cross-sectional, and longitudinal and behavior-genetic studies testing bidirectional associations between parenting and child general psychopathology are needed; however, our findings of associations between child-specific parenting and child psychopathology suggest potential evocative effects on parenting. In addition, our results should be interpreted considering the shared method variance, which may have inflated associations between parenting and child psychopathology.

We also found that higher child general psychopathology was associated with greater parent psychological distress, consistent with evidence that parental depression is related to child general psychopathology (Deutz et al., Reference Deutz, Geeraerts, Belsky, Deković, van Baar, Prinzie and Patalay2020; Wade et al., Reference Wade, Plamondon and Jenkins2021). Psychopathology is moderately to highly heritable (Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman and Rathouz2011). However, genetic and environmental influences are not easily separable because children inherit an overall genetic risk for psychopathology from their parents, and the same genetic factors may predict less adaptive parenting, or may evoke different parenting behaviors (Jaffee & Price, Reference Jaffee and Price2007; McAdams et al., Reference McAdams, Neiderhiser, Rijsdijk, Narusyte, Lichtenstein and Eley2014). We therefore emphasize the importance of not interpreting our findings as evidence of parenting causing child psychopathology and that further research using genetically informed designs is needed.

For the specific internalizing and externalizing factors, children within families showed little similarity, with most of the variance being at the individual level. Higher specific child externalizing was associated with less warmth and more aversive/inconsistent parenting on average toward children in the family, as well as toward an individual child relative to their siblings (Deutz et al., Reference Deutz, Geeraerts, Belsky, Deković, van Baar, Prinzie and Patalay2020; Waldman et al., Reference Waldman, Poore, van Hulle, Rathouz and Lahey2016). Our findings support results of previous studies that have used standard, non-bifactor, definitions of externalizing problems (Meunier et al., Reference Meunier, Bisceglia and Jenkins2012) and suggest that the warmth and aversiveness/inconsistency children are exposed to, both in the overall family, and the individual parenting they receive relative to their siblings, are associated with differences in specific externalizing, net of overall psychopathology.

We did not find consistent associations between specific internalizing and what is generally considered maladaptive parenting (less warmth, more aversive/inconsistent parenting). Instead, greater parental warmth overall in the family and toward an individual child relative to their siblings was associated with more specific internalizing problems, although follow-up analyses indicated these associations were significant in younger (4–11-year-old) but not older (12–17-year-old) children. An examination of item loadings shows that, after accounting for variance associated with the general psychopathology factor, items related to separation anxiety and social phobia continued to have relatively strong loadings on the specific internalizing factor. While unexpected, our findings are consistent with evidence that parents may show greater warmth and encouragement toward children who are more inhibited or who exhibit separation anxiety or social anxiety (Belsky et al., Reference Belsky, Rha and Park2000; Muris & Merckelbach, Reference Muris and Merckelbach1998). Previous findings of associations between aversive/inconsistent parenting and child internalizing (Pinquart, Reference Pinquart2017b) may have been driven primarily by associations with children’s overall psychopathology.

Effect sizes for associations between parenting variables and both general and specific psychopathology factors were small at the child level, after family level parenting was taken into account. However, these effect sizes were consistently stronger at the family level, ranging from small to medium. Our results are similar to those reported in a previous study of associations between differential parenting and child internalizing and externalizing problems (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Jenkins, Georgiades, Cairney, Duku and Racine2004), supporting the relatively greater importance of overall parenting within the family compared to child-specific parenting in non-clinical samples. Preventive interventions that focus on family-level parenting may therefore have the greatest potential to interrupt bidirectional associations between maladaptive parenting and overall child psychopathology at the population level, though interventions targeting within-family parenting differences may provide a small additional benefit.

Limitations, strengths, and future research directions

We relied on parent report (primarily mothers), which may have inflated associations between parenting and psychopathology due to informant effects. Relatedly, parenting ratings were skewed, suggesting potential under/over-rating. We also used a brief measure of parenting, and further studies using more detailed and established questionnaire measures of parenting, along with observationally coded parenting measures would provide stronger evidence. Our study is cross-sectional and cannot determine the direction of the association between parenting and psychopathology. We did not have information on the relatedness of siblings and were unable to test genetic contributions to the association between parenting and psychopathology. Caution must be used when interpreting the meaning of the specific psychopathology factors given the relatively small proportion of variance attributable to them in our sample and that specific factors have not consistently demonstrated external validity (Deutz et al., Reference Deutz, Geeraerts, Belsky, Deković, van Baar, Prinzie and Patalay2020). Strengths include the use of a large, epidemiological sample, reducing sampling bias; and measuring multiple children within a household, allowing us to separate family- and child-level differences. Further research in clinical samples is needed to determine whether similar patterns of results are seen among youth with higher levels of psychopathology symptoms. Future research using longitudinal designs, observationally coded- and/or multi-informant measures of parenting, and information on genetic relatedness is needed to further understand associations between parenting and general psychopathology.

Conclusion

Less parental warmth and more aversive and inconsistent parenting each had broad associations with overall liability for child psychopathology in our representative epidemiological sample of Ontario children. Additional research testing bidirectional associations between parenting and general psychopathology using genetically informed designs would help to understand the nature of these associations. The development and evaluation of preventive interventions focused on reducing maladaptive parenting may have important protective effects on children’s overall liability for psychopathology, notwithstanding the bidirectional and genetically mediated associations between parenting and psychopathology (Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Wright, Markon and Krueger2019; Lahey, Reference Lahey2011; McAdams et al., Reference McAdams, Neiderhiser, Rijsdijk, Narusyte, Lichtenstein and Eley2014). Such interventions may have the greatest benefit by primarily targeting overall parenting within the family.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579423000202.

Funding statement

Funding for this study was provided by the Cundill Centre for Child and Youth Depression at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Conflicts of interest

None.