The terms ‘clinical audit’ and ‘clinical governance’ elicit a variety of responses, including boredom, frustration, incomprehension and, rarely, enthusiasm. This paper sets out to persuade the reader that clinical audit, as an integral component of clinical governance, will be reborn as an activity that clinicians will find interesting, developmental and a useful part of their everyday clinical practice. Under clinical governance, clinical audit will at last be able to achieve important and measurable improvements in patient care as a matter of routine.

The paper begins with a brief history of the evolution of clinical audit and clinical governance in the National Health Service (NHS). It then argues that clinical governance will affect clinical audit by bringing about new accountability, increased organisational responsibility and support, a new, integrated approach to clinical quality improvement activities, improved ‘knowledge management’, and new responsibilities and support for individuals. Finally, the paper outlines some potential barriers to the future development of clinical audit and it challenges clinicians, managers and the Government to address these so that real improvements in patient care can be achieved.

Quality improvement initiatives in the NHS

Medical audit to clinical audit

Medical audit was introduced into the NHS as part of the White Paper, Working for Patients (Department of Health, 1989), which also introduced the NHS internal market. Medical audit is the process of setting explicit standards, measuring areas of medical practice against these standards and implementing any change necessary to improve patient care. The Thatcher Government believed that the combination of medical audit with the competition and contracting process introduced by the internal market would lead to improved standards of care throughout the NHS (Reference Donaldson and GrayDonaldson & Gray, 1998) and, by 1990, participation in medical audit was included in contracts for hospital doctors. In the early 1990s, it became increasingly apparent that it was nonsensical to exclude professions other than medicine from the audit process. Medical audit evolved into clinical audit and became a process undertaken by multi-disciplinary teams.

Quality in the new NHS

By the time the Government of John Major lost power in 1997, three separate approaches to quality improvement in the NHS could be observed: approaches by clinicians through clinical audit and clinical effectiveness; ‘quality’, which almost without exception referred to improvement in organisational quality (e.g. the Patients’ Charter and monitoring of waiting lists and waiting times); and initiatives to find out what service users think of quality, primarily through patient satisfaction surveys and complaints systems.

By 1997, a view had developed that the separate initiatives of clinical audit, patient satisfaction surveys, monitoring waiting times, guidelines for and sporadic attempts at total quality management and other quality initiatives were no longer sufficient for the NHS (Reference Donaldson and GrayDonaldson & Gray, 1998). Well-publicised scandals, now known simply as ‘Bristol’ and ‘Canterbury’, made the quality of clinical care an issue of widespread public concern:

‘The enormously negative public impact of recurrences of similar failures, [gives] an impression that health services are unable to correct problems reliably and [conveys] a sense of history repeating itself’ (Reference DonaldsonDonaldson, 1998).

When New Labour came to power in 1997, it was quick to produce four White Papers for the NHS (one for each UK country), each of which placed quality central to national health policy. The English White Paper illustrates this new emphasis:

‘Every part of the NHS, and everyone who works in it, must take responsibility for improving quality. This must be quality in its broadest sense: doing the right things, at the right time, for the right people, and doing them right – first time. And it must be the quality of the patient experience as well as the clinical result – quality measured in terms of prompt access, good relationships and efficient administration’ (Department of Health, 1997).

The Government set out three action areas to achieve this new ‘quality culture’. These were: national standards and guidelines (including National Service Frameworks); clinical governance; and a monitoring function to be provided by the new Commission for Health Improvement (CHI).

Clinical governance

Clinical governance has its roots in the commercial sector. In 1992, a number of high-profile misdemeanours led the Government to recommend standards for financial management to companies in the private sector, including duties, accountabilities and rules of conduct (Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance, 1992). Later, this ‘corporate governance’ also became a requirement for the NHS (Committee on Standards in Public Life, 1995).

Clinical governance aims to mirror the accountability and responsibilities of corporate governance in the area of health service quality and it is central to the Government's policy for the NHS. Clinical governance is defined as:

‘A framework through which NHS organisations are accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish’ (Department of Health, 1998: p. 33).

Chief executives of NHS trusts and primary care trusts have, for the first time, become directly accountable for the quality of service provided by their organisations. From April 1999, acute and community NHS trusts should have established structures and processes for effective clinical governance. The implementation and development of clinical governance will be monitored by the CHI.

The key components of clinical governance

Clinical governance is a comprehensive approach which aims to be a framework for many of the quality-related initiatives already undertaken in the NHS, including clinical audit, evidence-based practice, risk management, continuing professional development, the setting of clinical standards, clinical guidelines, workforce planning, and research and development. It includes four key areas:

-

(1) clear lines of responsibility and acceptability for the overall quality of clinical care;

-

(2) a comprehensive programme of quality improvement activities – including clinical audit;

-

(3) clear policies aimed at managing risks;

-

(4) procedures for all professional groups to identify and remedy poor performance.

What are the implications for clinical audit?

‘Clinical audit is regarded as one of the cornerstones of clinical governance’ (Reference Oyebode, Brown and ParryOyebode et al, 1999a ). Clinical governance will have a significant impact on the way clinical audit is undertaken and managed within mental health and learning disability services.

New accountability

Clinical governance places a new accountability for quality management on chief executives. Just as they are accountable for the sound financial management of a trust, including effective financial audit structures, they are now also accountable for ensuring that the quality of care meets minimum standards and that this is monitored throughout the organisation. CHI visits trusts to inspect the systems established for quality management. Problem areas are raised with chief executives and action plans put into place to ensure that quality improves. Thus, quality monitoring and improvement has become a core component of routine trust management rather than an activity which has, in the past, been an ‘optional extra’ undertaken by a few enthusiasts, or one which is prioritised only following a public scandal.

Clinical audit is the principal method used to monitor clinical quality (in the same way as financial audit monitors financial activities). Clinical governance should, therefore, have the effect of raising the status of clinical audit within trusts. Evidence of this should include discussions of clinical audit priorities at trust board level, appropriate funding for clinical audit support teams and availability of protected time so that clinicians can participate in clinical audit.

Clinical audit committees will now report to the trust board's clinical governance subcommittee. The trust's clinical audit lead will be represented on this subcommittee and, usually for the first time, will have a direct line of communication to senior trust management structures and the trust board (Anonymous, 1999).

Performance management

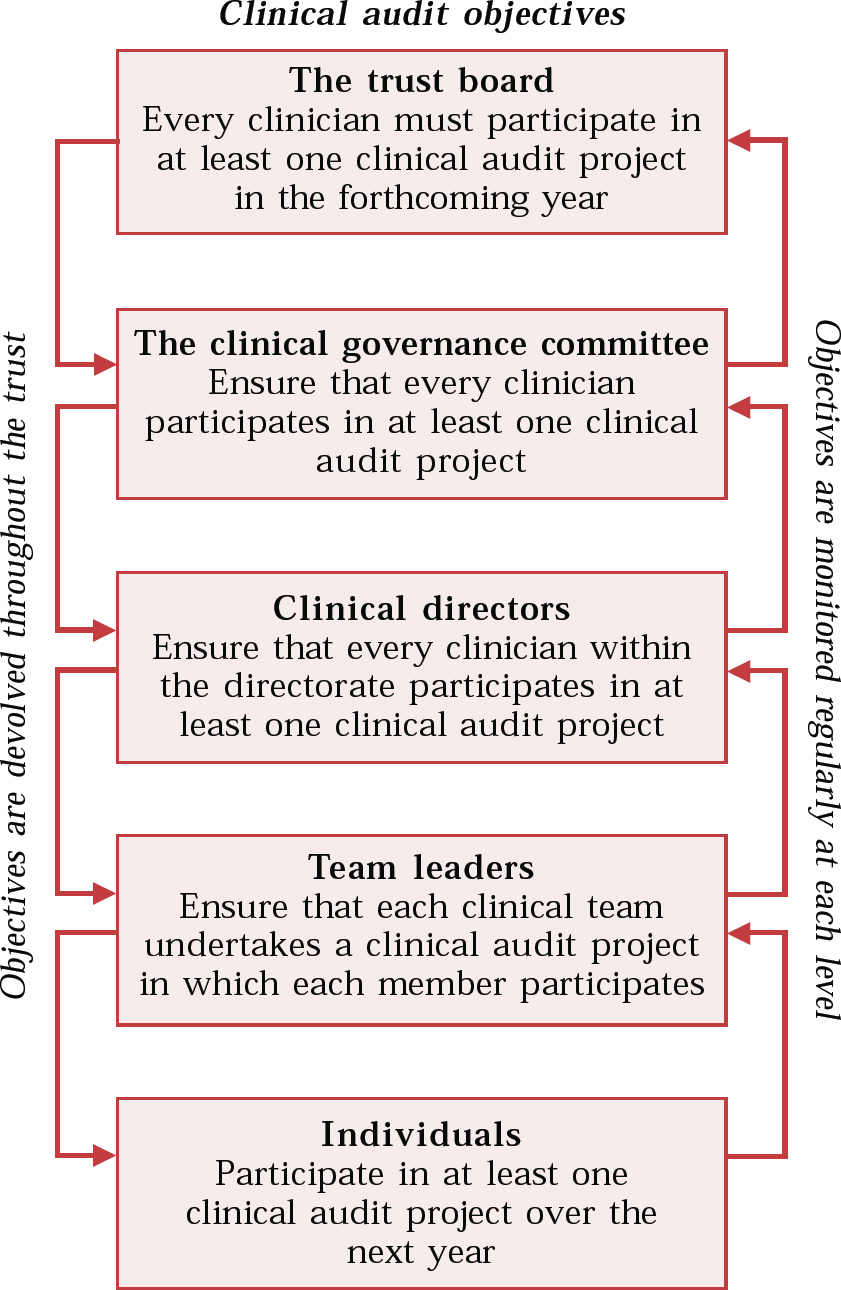

The term ‘performance management’ describes the process of devolving organisational objectives throughout a trust, ensuring that they are reflected in the objectives of each individual, team, department and directorate. How well individuals, teams and so on. meet the objectives will be systematically monitored, for example, through staff appraisal. Performance management is central to the implementation of clinical governance. For the first time, it will ensure that objectives for clinical audit are established and monitored throughout each mental health service, from the trust board to each individual clinician, service manager and appropriate member of the support staff. An example of how this might work is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Using performance management to implement and monitor an organisation-wide objective for clinical audit

Managers now have a clear role, working with clinicians to set priorities for clinical audit projects, ensure clinicians’ participation in clinical audit and ensure that action is taken, where possible, for any areas identified as needing improvement. Managers will also need to work with clinicians to identify and overcome barriers to effective audit such as lack of time for clinicians to participate in audit and organisational barriers to implemention of change. Performance management should, therefore, significantly increase the effectiveness of audit to achieve improvements in patient care.

New responsibility for individuals

As we have seen, clinical governance devolves accountability for continuous quality improvement throughout the organisation, making it the responsibility of every individual. For individual clinicians, clinical audit is one of the key ways in which this new responsibility can be discharged. Box 1 outlines the NHS Executive's expectations for individual learning in relation to clinical audit.

Box 1. Expectations for learning

During the course of professional development, health care professionals should:

Identify sources of good practice advice (including patient consent) for clinical audit

Demonstrate an understanding of the basic components of audit and outline the benefits to patients and practitioners

Define the principal components of the audit cycle

Identify the uses of data and information at various stages of the cycle and describe ways in which information technology may be used to facilitate the process

Identify the implications and risks of miscoding data

Discuss the practical impediments to audit in the working environment

Have used a range of sources (including the internet) to search for standards and evidence when designing and audit

Design and carry out an audit in the workplace that makes best use of the available information technology in that task

Demonstrate the attributes of a good audit proposal and report

Discuss the relationship between audit and clinical governance and the implications for audit

Carry out an evaluation of an audit project and audit programme and delineate the roles of the consumer (patient) in the audits and their management.

(from NHS Executive, 1999a )

Integrating clinical audit

In the past, many services carried out clinical audit in isolation from other related activities such as continuing professional development (CPD), evidence-based practice and research. Clinical governance aims to ensure ‘a comprehensive programme of quality improvement activities’ (Department of Health, 1997) and it brings together, under one framework, a wide range of initiatives which had previously been managed separately. Table 1 shows the integral relationships between clinical audit and the other components of clinical governance. The clinical governance committee will lead all these activities.

Table 1 The relationship between clinical audit and other components of clinical governance

| Evidence-based practice | Clinical audit standards describe ‘what should be done’ in a particular clinical situation. is up to date and, where possible, based on sound research. They should therefore be based on the best available evidence to ensure that practice |

| User/patient involvement | Clinicians and service users may differ in their opinion about what constitutes best practice and a good outcome. It is therefore important to involve service users in identifying priority topics for clinical audit, setting audit standards, monitoring practice and identifying areas which need to be improved. |

| Risk management | Clinical audit can be used to implement and monitor risk management standards and identify areas for improvement. A good example is the national clinical audit of the management of violence by the Research Unit of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (Reference Wing, Marriott and PalmerWing et al, 1998). |

| Complaints | Complaints can provide a valuable means of identifying areas within which service users are dissatisfied and which are therefore priority areas for standard-setting and clinical audit. |

| Research and development | Clinical audit will often generate questions for research, e.g. an audit of antipsychotic medication may find that a high percentage of patients stop taking their medication without consulting their psychiatrist or general practitioner. Why? Conversely, clinical audit can be used to implement and monitor the take-up of research findings (see evidence-based practice, above). |

| Workforce planning | Clinical audit projects often identify areas in which a change in the workforce can improve patient care, e.g. by providing weekend cover, by changing skills mix. Ensuring that clinicians have protected time to enable them to participate in clinical audit also, in itself, requires workforce planning. |

| The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide | Under clinical governance, it is now compulsory for mental health services to participate in the National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness (http://www.confidentialinquiry.man.ac.uk). Mental health services can use the recommendations arising from the Inquiry as a basis for local clinical audit standards. |

| Continuing professional development (CPD) | Clinical audit is a useful method whereby clinicians can measure the extent to which they have met CPD objectives. In addition, the results of clinical audit projects often identify areas in which further development or training is needed. |

| Implementation of guidelines, national service frameworks and National Insitute for Clinical Excellence recommendations | The incorporation of guidelines and national recommendations into local clinical audit standards can assist in their implementation (by raising awareness and by providing reminders of the guidelines) and enables collection of information about the extent to which they have been implemented, together with the identification of barriers to implementation. |

| Ensuring the quality of clinical record systems | Standards for clinical record-keeping form the basis of many clinical audit projects. Even where it is not the central purpose of the exercise, many projects reveal information about the standard of clinical record systems, e.g. by quantifying the number of sets of clinical notes not available, information missing from records (such as test results) and the illegibility of notes. |

| Ensuring confidentiality and implementation of the Caldicott Report | Standards for confidentiality and the recommendations arising from the Caldicott Report (NHS Executive, 1999b ) can form the basis of a clinical audit project. (A support pack (Reference PalmerPalmer, 1999) on the Caldicott Report containing audit tools has been produced by the College Research Unit.) |

This new integrated framework for quality improvement activities will enable better communication and working between the different initiatives, adding value to each. It will now be easier for organisational priorities such as the implementation of the National Service Frameworks (NSFs), to be integrated into each initiative, thus ensuring that all the different support mechanisms share the same aims and facilitating teamworking and skills-sharing. So, for example:

-

(a) continuing professional development programmes can be used to inform clinicians about NSFs and provide opportunities for discussion and feedback about their implementation;

-

(b) human resources departments will need to consider the staffing implications of meeting NSF standards;

-

(c) information departments will need to ensure that their systems provide the information needed by clinicians, managers and service users to ensure NSF implementation;

-

(d) clinical audit will be used to measure the extent to which NSF standards have been implemented.

Re-addressing information requirements

The whole clinical governance agenda depends on accurate clinical information being available to clinicians, managers, service users and the public:

‘Continual improvement of clinical service quality across the NHS must be supported by information on current comparative effectiveness and outcomes. It also requires a culture among clinical staff where the obligation on individuals to assess personal performance on a continuous basis is accepted as a natural and important element of being a professional’ (NHS Executive, 1998).

This information will come from a variety of sources, which may include internal information management systems (e.g. a patient administration system), focus groups, surveys, specific internal databases (e.g. risk management databases), routine audit, the National electronic Library for Mental Health and national centres (e.g. the National Institute for Clinical Excellence and the Royal College of Psychiatrists). The task of assessing information needs, identifying information sources and developing systems of providing information to clinicians in a way which makes it useful in practice and in audit is known as ‘knowledge management’ (Reference Wattis and McGinnisWattis & McGinnis, 1999). The mental health information strategy currently in development promises to improve the availability of information for clinical audit and clinical governance.

Barriers

In this paper I have intentionally taken a very positive stance on the future of clinical audit under clinical governance. Many things may, of course, create barriers to the further development of clinical audit, including organisational culture, low prioritisation and lack of support.

Organisational culture

Despite the rhetoric of the ‘no-blame culture’ which appears throughout clinical governance policy documents, many clinicians and managers feel that the blame culture in the NHS is stronger than ever. There are real fears that participation in clinical audit will lead to punishment of poor performers (Reference Buetow and RolandBuetow & Roland, 1999) and possibly even result in litigation (Reference Beresford and EvansBeresford & Evans, 1999). Until the NHS becomes an organisation in which it really is safe to reveal mistakes and lessons are learnt from them, the aim of clinical audit will not be achieved.

Low prioritisation

Clinical audit has traditionally had a low priority within the NHS in comparison with, for example, research. Individuals have regarded it as time-consuming, not useful and tedious (Reference Buetow and RolandBuetow & Roland, 1999) and the rewards of participation in research (e.g. journal papers, allocated time) have not been available for audit. Chief executives and trust boards have taken very little interest in clinical audit and it has rarely been included in organisational priorities (Reference BergerBerger, 1998). Topics for audit have been identified largely on the basis of clinical preference and personal interest rather than organisational priority (Reference McErlain-Burns and ThomsonMcErlain-Burns & Thomson, 1999). This low prioritisation has been exacerbated by the huge amount of organisational change imposed on the NHS over the past 10 years and the mergers currently taking place between a number of mental health services.

Lack of support

The low priority given to clinical audit by organisations and individuals has led to a lack of practical support. This is manifest in the poor information support systems, lack of allocated time and paucity of training in audit methods. These should all now be addressed by clinical governance committees to ensure that audit becomes an integral component of clinical governance (Reference JamesJames, 1999).

Conclusions

The greatest culture change that the Government intends to achieve through clinical governance is to ensure that NHS trusts focus all their efforts, structures and processes on the provision of high-quality clinical services and care. This sounds obvious, but it has been argued that the health service has, in the past, been managed as though clinical matters were peripheral to its main concern (Reference Oyebode, Brown and ParryOyebode, Brown & Parry, 1999b ). Clinical governance returns clinical care to its position of central priority for mental health services. The role of services such as central administration, information, finance, human resources and training must prioritise support for clinicians so that they can provide high-quality clinical care. These services must play a more supportive role and ensure that clinicians have the resources they need to participate in audit (information, time, training, etc.) and to implement necessary change through the clinical audit process. This refocusing will allow clinical audit to achieve the potential which its supporters have always believed possible. As well as direct improvement in patient care, this includes motivation of staff, improvement in teamworking, contribution to personal development and, thereby, the retention of valuable staff.

There are a number of barriers to clinical audit that must be addressed if clinical governance is to have a chance of achieving its ambitious aims. Informatics, clinical audit and clinical governance are inextricably linked, and good quality, accessible clinical information is essential. Individuals, trusts and the Government need to ensure that effective support (practical, cultural and leadership) is forthcoming if the ‘New NHS’ is really to bring about improvements in patient care and outcomes.

Multiple choice questions

-

1. Clinical governance means that quality monitoring and improvement are:

-

a the responsibility of the trust board

-

b mainly undertaken by management consultants

-

c the responsibility of every clinician

-

d an optional activity

-

e the sole responsibility of NHS managers.

-

-

2. Clinical audit is more likely to lead to improvements in patient care if:

-

a it has support from senior trust managers

-

b it is done by multi-disciplinary clinical teams

-

c managers are not involved

-

d it is used to identify and punish poorly performing doctors

-

e it receives practical support from trust information departments.

-

-

3. During the course of professional development, psychiatrists should:

-

a identify sources of good practice advice (including patient consent) for clinical audit

-

b participate in clinical audit projects that aim to identify mistakes in clinical practice

-

c identify the implications and risks of miscoding data

-

d design and carry out an audit in the workplace that makes best use of the available information technology

-

e only participate in clinical audit projects that involve only other psychiatrists.

-

-

4. Clinical governance includes:

-

a research and development

-

b evidence-based practice

-

c risk management

-

d financial management

-

e clinical audit.

-

-

5. The aim of clinical audit is to:

-

a save money

-

b obtain evidence for use in disciplinary procedures

-

c improve patient care and outcomes

-

d gather information

-

e ensure clinical practice is based on the best available evidence.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | T | a | T | a | T | a | a |

| b | F | b | T | b | F | b | b |

| c | T | c | F | c | T | c | c |

| d | F | d | F | d | T | d | d |

| e | F | e | T | e | F | e | e |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.