After Donald Trump lost the 2020 US presidential election, he and his allies made sweeping and unsupported claims that the election had been stolen. These unsubstantiated assertions ranged from familiar voter-fraud tropes (claims that illegitimate ballots were submitted by dead people) to the fanciful (voting machines were part of a complicated conspiracy involving the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chávez). Amid increasingly heated rhetoric, a January 6, 2021 “Stop the Steal” rally was followed by a violent insurrection at the US Capitol that sought to disrupt the certification of President-elect Biden’s victory, a tragic event many observers partially attributed to the false claims of fraud made by President Trump and his allies.

Claims of voter fraud like this are not uncommon, especially outside the USA. In early February 2021, the Myanmar military justified its coup against the civilian government by alleging voter fraud in the most recent election (Goodman Reference Goodman2021). In other cases, elites have made unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud in order to cast doubt on unfavorable or potentially damaging electoral results. For instance, Jair Bolsonaro, the president of Brazil, expressed fears of voter fraud during his presidential campaign in 2018 to pre-emptively cast doubt on an unfavorable electoral outcome (Savarese Reference Savarese2018). Prabowo Subianto, a presidential candidate who lost the 2019 Indonesian election, used this tactic even more aggressively, claiming that he had been the victim of voter fraud and refusing to concede (Paddock Reference Paddock2019).

Though accusations of misconduct are a frequent feature of electoral politics, the effects of this phenomenon on voter beliefs and attitudes have not been extensively studied. To date, research has largely focused on how actual irregularities or the presence of institutions intended to constrain malfeasance affect electoral confidence, particularly in less established democracies (e.g., Norris Reference Norris2014; Hyde Reference Hyde2011). Less is known about the effects of unfounded assertions of voter fraud on public faith in free and fair elections, especially in advanced democracies such as the USA. Can elites delegitimize a democratic outcome by asserting that electoral irregularities took place? Our motivating examples, particularly recent events in the USA, suggest reasons for concern. Given the centrality of voter fraud to Trump’s rhetoric in the weeks leading up the January 6 insurrection, it is essential to better understand whether and how baseless accusations of election-related illegalities affect citizens. Footnote 1

While recent events and the voluminous elite cues literature (e.g., Zaller Reference Zaller1992) lead us to expect that fraud claims would have a deleterious effect, several streams of previous research suggest that political leaders may have a limited ability to alter citizen’s attitudes about the legitimacy of foundational political institutions like elections by inventing accusations of fraud. First, previous work in this area suggests that unsubstantiated claims of widespread voter fraud may have little effect on public attitudes. Most notably, recent studies of the 2016 US presidential election using panel designs provide mixed evidence on the effect of voter-fraud claims. Despite Donald Trump’s frequent (and unsubstantiated) claims of voter fraud before that election, Trump voters’ confidence in elections did not measurably change and Democrats’ confidence in elections actually increased pre-election, possibly in response to Trump’s claims (Sinclair, Smith and Tucker Reference Sinclair, Smith and Tucker2018). After the election, confidence in elections actually increased and belief in illicit voting decreased among Trump supporters (a classic “winner effect”) while confidence of Clinton’s voters remained unchanged (Levy Reference Levy2020).

Second, there is a reason to be skeptical about claims that political leaders can alter citizens’ attitudes so easily by alleging fraud. Studies find, for instance, that presidents struggle to change public opinion on most topics despite extensive efforts to do so (Edwards Reference Edwards2006; Franco, Grimmer and Lim n.d.). Moreover, they may face electoral sanctions for challenging democratic norms. Reeves and Rogowski (Reference Reeves and Rogowski2016, Reference Reeves and Rogowski2018), for instance, argue that leaders are punished for acquiring or exercising power in norm-violating ways. Similarly, conjoint studies by Carey et al. (Reference Carey, Clayton, Helmke, Nyhan, Sanders and Stokes2020) and Graham and Svolik (Reference Graham and Svolik2020) show that voters punish candidates for democratic norm violations, though the magnitude of these punishments are modest and voters may be more willing to apply them to the opposition party.

Finally, even psychological factors and message effects that make people vulnerable to claims of fraud such as directionally motivated reasoning, framing, and elite cues face boundary conditions (Cotter, Lodge and Vidigal Reference Cotter, Lodge and Vidigal2020; Druckman Reference Druckman2001; Nicholson Reference Nicholson2011). For instance, fact-checking may help promote accurate beliefs and reduce the scope of misinformation effects (Nyhan and Reifler Reference Nyhan and Reifler2017; Wood and Porter Reference Wood and Porter2019), though the effect of corrections on broader attitudes and behavioral intentions is less clear (Nyhan et al. Reference Nyhan, Porter, Reifler and Wood2019, Reference Nyhan, Reifler, Richey and Freed2014). In addition, respondents may distrust the sources of these claims and in turn discount the messages they offer.

In short, while politicians undoubtedly make unfounded claims of voter fraud, available evidence is less clear about whether such claims affect citizens’ faith in elections. Our study addresses the limitations of prior panel studies and provides direct experimental evidence of the effects of unfounded accusations of voter fraud on citizens’ confidence in elections. This approach is most closely related to that of Albertson and Guiler (Reference Albertson and Guiler2020), who show that telling respondents that “experts” believe that the 2016 election was vulnerable to manipulation and fraud increased perceptions of fraud, lowered confidence in the electoral system, and reduced willingness to accept the outcome. However, our study differs in that the accusations we test come from political leaders, a more common source in practice (experts believe voter fraud is exceptionally rare in the USA).

We specifically evaluate the effects of exposure to voter-fraud claims from politicians in the context of the aftermath of the 2018 US midterm elections. Notably, we not only test the effects of such accusations in isolation, but also examine the effects of such exposure when fraud claims are paired with fact-checks from independent experts. This design approach is critical for evaluating potential real-world responses by, for example, social media companies that seek to mitigate harm from voter-fraud claims (Klar Reference Klar2020).

Our results show that exposure to unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud from prominent Republicans reduces confidence in elections, especially among Republicans and individuals who approve of Donald Trump’s performance in office. Worryingly, exposure to fact-checks that show these claims to be unfounded does not measurably reduce the damage from these accusations. The results suggest that unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud undermine the public’s confidence in elections, particularly when the claims are politically congenial, and that these effects cannot easily be ameliorated by fact-checks or counter-messaging. However, we find no evidence that exposure to these claims reduces support for democracy itself.

From this perspective, unfounded claims of voter fraud represent a dangerous attack on the legitimacy of democratic processes. Even when based on no evidence and countered by non-partisan experts, such claims can significantly diminish the legitimacy of election outcomes among allied partisans. As the Capitol insurrection suggests, diminished respect for electoral outcomes presents real dangers for democracy (e.g., Minnite Reference Minnite2010). If electoral results are not respected, democracies cannot function (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Blais, Bowler, Donovan and Listhaug2005). And even if losers step down, belief in widespread voter fraud threatens to undermine public trust in elections, delegitimize election results, and promote violence or other forms of unrest.

Experimental design

We conducted our experiment among 4,283 respondents in the USA who were surveyed online in December 2018/January 2019 by YouGov (see Online Appendix A for details on the demographic characteristics of the sample, response rate, and question wording). Footnote 2 This research was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Exeter, the University of Michigan, Princeton University, and Washington University in St. Louis. After a pre-treatment survey, respondents were randomly assigned to view either a series of non-political tweets (placebo); four tweets alleging voter fraud (low dose); the four tweets alleging voter fraud from the low-dose condition plus four additional tweets alleging voter fraud (high dose); or the four tweets from the low-dose condition alleging voter fraud plus four fact-check tweets (low dose + fact-check). Respondents then completed post-treatment survey questions measuring our outcome. Respondents were unaware of treatment condition. There was no missing data for our primary outcome, and minimal missing data for secondary outcomes (between 0.0% and 0.9%). A summary of missing data for outcome measures and moderators can be found in Table A3.

Immediately after the election, several prominent Republicans, including Florida Governor Rick Scott, Senators Lindsey Graham and Marco Rubio, and Trump himself, made unfounded allegations of voter fraud while counts were still ongoing (Lopez Reference Lopez2018). Tweets from these political elites and fact-checks of the claims were used as the treatment stimuli (see Figure 1 for an example). This design has high external validity, allowing us to show actual claims of voter fraud made by party elites to respondents in the original format in which they were seen by voters.

Figure 1. Example stimulus tweet from the experiment.

To match this format’s external validity, we draw on actual corrections produced by the Associated Press, PBS NewsHour, and NYT Politics, again in the form of tweets (see Online Appendix A). Though these messages do not come from dedicated fact-checking outlets per se, these standalone articles fit within the larger diffusion of the format through the mainstream press (Graves, Nyhan and Reifler Reference Graves, Nyhan and Reifler2015) and follow prior work on journalistic corrections (Nyhan et al. Reference Nyhan, Porter, Reifler and Wood2019; Nyhan and Reifler Reference Nyhan and Reifler2010; Pingree et al. Reference Pingree, Watson, Sui, Searles, Kalmoe, Darr, Santia and Bryanov2018).

Hypotheses and research questions

We expect that exposure to unfounded voter-fraud claims reduces confidence in elections (e.g., Alvarez, Hall and Llewellyn Reference Alvarez, Hall and Llewellyn2008; Hall, Quin Monson and Patterson Reference Hall, Monson and Patterson2009), the immediate object of criticism, and potentially undermines support for democracy itself (Inglehart Reference Inglehart2003). This expectation leads to four preregistered hypotheses and two research questions. Footnote 3

Our first three preregistered hypotheses concern the effect of exposure to voter-fraud allegations. We expect that low (H1a) and high (H2a) doses of exposure to allegations of voter fraud will reduce confidence in elections and that a high dose will have a stronger effect (H3a). The idea that increased message dosage should lead to greater effects is long-standing and intuitive (Arendt Reference Arendt2015; Cacioppo and Petty Reference Cacioppo and Petty1979) and has received some empirical support (e.g., Ratcliff et al. Reference Ratcliff, Jensen, Scherr, Krakow and Crossley2019), but evidence is limited for this claim in the domain of politics (Arendt, Marquart and Matthes Reference Arendt, Marquart and Matthes2015; Baden and Lecheler Reference Baden and Lecheler2012; Lecheler and de Vreese Reference Lecheler and de Vreese2013; Miller and Krosnick Reference Miller and Krosnick1996). Higher doses may have diminishing returns in political messaging, with large initial effects among people who have not previously been exposed to similar messages but less additional influence as exposure increases (Markovich et al. Reference Markovich, Baum, Berinsky, de Benedictis-Kessner and Yamamoto2020).

We also expect the effects of exposure to be greater when the claims are politically congenial (H1b–H3b) given the way pre-existing attitudes affect the processing of new information (e.g., Kunda Reference Kunda1990; Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2006), including on election/voter fraud (Edelson et al. Reference Edelson, Alduncin, Krewson, Sieja and Uscinski2017; Udani, Kimball and Fogarty Reference Udani, Kimball and Fogarty2018).

Fact-checks can be effective in counteracting exposure to misinformation (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Jones, Jamieson and Albarracn2017; Fridkin, Kenney and Wintersieck Reference Fridkin, Kenney and Wintersieck2015). Our fourth hypothesis therefore predicts that fact-checks can reduce the effects of exposure to a low dose of voter-fraud misinformation on perceived electoral integrity (H4a). We also expect fact-checks will reduce the effects of voter-fraud misinformation more for audiences for whom the fraud messages are politically congenial simply because the initial effects are expected to be larger (H4b).

Finally, we also consider preregistered research questions. First, we ask whether exposure to both a low dose of allegations of voter fraud and fact-checks affects confidence in elections compared to the placebo condition baseline per Thorson (Reference Thorson2016) (RQ1a). Second, we test whether this result differs when the claims are politically congenial (RQ1b). Footnote 4 Finally, we examine whether these effects extend beyond attitudes toward electoral institutions and affect support for democracy itself (RQ2). Footnote 5

Methods

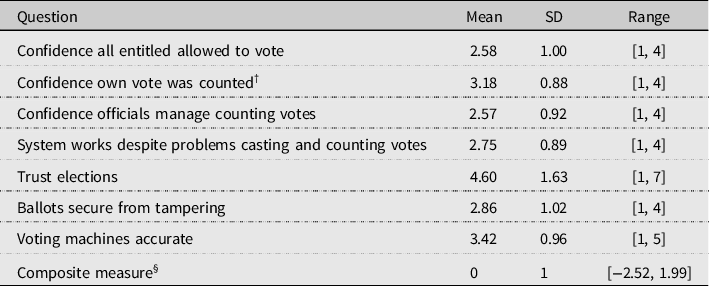

To test our main hypotheses, we examine seven survey items that tap into different aspects of election integrity (e.g., “How confident are you that election officials managed the counting of ballots fairly in the election this November?”). Descriptive statistics for all items are shown in Table 1 and complete question wording is shown in Online Appendix A. On average, respondents indicated modestly high levels of confidence in US electoral institutions and election integrity.

Table 1. Measures of Confidence in Elections

Notes: Complete question wordings for all items are provided in Online Appendix A.

†Indicates that the item was only asked of respondents who indicated they voted.

§Indicates a composite measure of election confidence that was created using confirmatory factor analysis (see Online Appendix B for estimation details).

Table 2. Effect of Exposure to Voter Fraud Allegations on Election Confidence

Notes: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005 (two-sided). Ordinary least-squares regression models with robust standard errors. The outcome variable is a composite measure of election confidence created using confirmatory factor analysis (see Online Appendix B for estimation details).

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) showed that these items scaled together; we therefore created a standardized outcome measure of confidence in the electoral system. All seven items loaded onto a single factor; the absolute value of the factor loadings was greater than 0.6 for all cases and typically larger than 0.8. To identify the latent space, we set the variance of the latent factor to one, allowing all treatment effects to be interpreted as sample standard deviations (SDs). A full discussion of this process is presented in Online Appendix B. Footnote 6

We estimate linear regression models that include only main effects for experimental conditions as well as models that interact treatment indicators with measures for whether voter-fraud misinformation was congenial for respondents. In our original preregistration, we stated we would test the hypotheses related to congeniality by including an interaction term with an indicator for whether or not a respondent is a Republican, which implicitly combines Democrats and independents into a single category. We found that Democrats and independents actually responded quite differently to the treatments and therefore deviate from our preregistration to estimate results separately using all three categories below (the preregistered analysis is provided in Table C3 in the Online Appendix). In addition, we also conducted exploratory analyses using approval of President Trump as an alternative moderator of whether the fraud messages were congenial.

Finally, for RQ2, we relied on a separate five-item battery measuring commitment to democratic governance reported in Online Appendix A. We analyze both the individual items and two composite scales suggested by our EFA (see Footnote 1).

Deviations from preregistered analysis plan

For transparency, we provide a summary of the deviations from our preregistration here. First, per above, we now examine potential congeniality effects for Republicans, Democrats, and independents separately rather than examining differences between Republicans and all others. Online Appendix C contains the preregistered specification in which Democrats and independents are analyzed together. Second, we present an additional, exploratory test of congeniality using Trump approval as a moderator. Third, we present main effects below for individual items from our outcome measure of election confidence in addition to the composite measure; our preregistration stated that we would report results separately for each dependent variable included in the composite measure in the Online Appendix, but we have included these models in the main text. Fourth, RQ2 deviates from our preregistration in that effects on both election confidence and support for democracy were included as outcomes of interest for H1–H4 and RQ1 pending a preregistered factor analysis of the individual items. As this factor analysis distinguished between these outcomes (see Online Appendix B), we conduct separate analyses for support for democracy. These results are discussed briefly below, but are reported in full in Online Appendix C. A complete discussion of our preregistered analyses as well as deviations are shown in Online Appendix E.

Results

We focus our presentation below on estimated treatment effects for our composite measure of election confidence. However, we present treatment effects for each component outcome measure (exploratory) as well as the composite measure of election confidence (preregistered) in Table 2. Figure 2 shows the effects for the composite measure. Since the composite measure is standardized, the effects can be directly interpreted in terms of SDs.

We find that exposure to the low-dose condition significantly reduced confidence in elections compared to the placebo condition (H1a: β = −0.147 SD, p < 0.005). This pattern also held in the high-dose condition (H2a: β = −0.168 SD, p < 0.005). Footnote 7 However, we fail to reject the null hypothesis of no difference in effects (H3a); the effects of exposure to low versus high doses of tweets alleging voter fraud are not measurably different. This result, which we calculate as the difference in treatment effects between the low-dose and high-dose conditions, is reported in the row in Table 1 labeled “Effect of higher dosage.” Footnote 8

A crucial question in this study is whether the effect of fact-check tweets can offset the effect of the tweets alleging fraud. We find that exposure to fact-checks after a low dose of unfounded voter-fraud claims did not measurably increase election confidence relative to the low-dose condition. As a result, the negative effects of exposure remain relative to the placebo condition.

Specifically, we can reject the null hypothesis of no difference in election confidence between participants exposed to the low dose + fact-check tweets versus those in the placebo condition (RQ1a: β = −0.092. SD, p < 0.05). This effect is negative, indicating the fact-check tweets do not eliminate the harmful effects of exposure to unfounded allegations of fraud on election confidence. Substantively, the effect estimate is smaller than the effect for the low-dose condition with no fact-check tweets described above (H1a: β = −0.147 SD, p < 0.005) but the difference is not reliably distinguishable from zero (H4a: β low dose + fact-check − β low dose = −0.055 SD, p > 0.05).

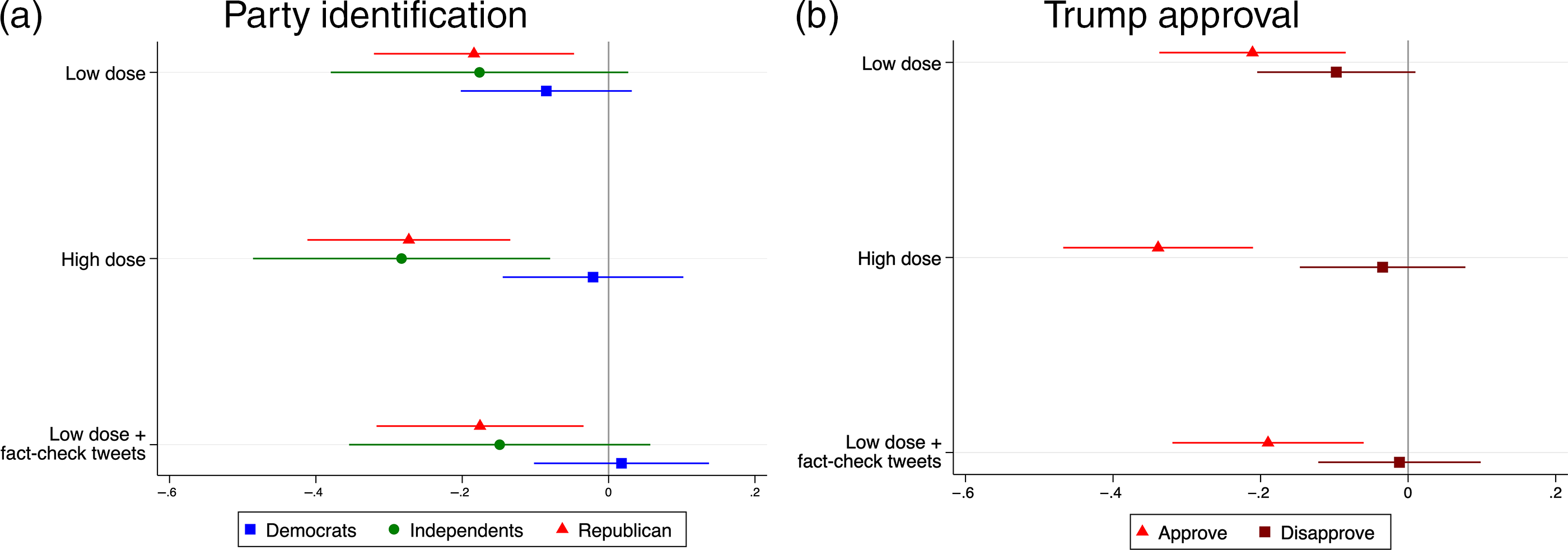

Next, we examined the effect of voter-fraud messages on respondents for whom the content of those messages (and the sources who endorse them) would be congenial – the Republican identifiers and leaners whose party was seen as losing the 2018 midterm elections. We estimate how our treatment effects vary by party and by approval of President Trump in Tables C1 and C2 in Online Appendix C. The resulting marginal effect estimates are presented in Figure 3. Footnote 9

Figure 2. Marginal effect of exposure to claims of voter fraud on confidence in elections.

Notes: Difference in means (with 95% CIs) for composite measure of election confidence relative to the placebo condition.

Figure 3. Effect of exposure to claims of voter fraud on election confidence by predispositions.

Notes: Figure 3(a) shows the marginal effect by party of exposure to claims of voter fraud on composite measure of election confidence relative to the placebo condition (Table C1), while Figure 3(b) shows the marginal effect by Trump approval (Table C2). All marginal effect estimates include 95% CIs.

We first analyze the results based on party identification. We find that the effects of exposure to a high dose of voter-fraud misinformation vary significantly by party (H2b; p < 0.01), decreasing voter confidence significantly only among Republicans. By contrast, the effect of the low dosage of four tweets of voter-fraud misinformation is not measurably different between Democrats and Republicans (H1b), though the message’s marginal effect is significant for Republicans (p < 0.01) and not for Democrats. Similarly, the effect of greater dosage of fraud allegations (i.e., high versus low dosage) does not vary measurably by party (H3b).

Results are similar when we consider attitudes toward President Trump as a moderator. The effects of exposure to tweets varies significantly by approval in the high-dose condition (p < 0.005), significantly reducing election confidence only among respondents who approve of Trump. The interaction is not significant for the low-dose condition, though again the effect of the treatment is only significant among Trump approvers. Further, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that the additional effect of exposure to fact-check tweets (versus just the low dose of fraud tweets) varied by Trump approval. However, the dosage effect (low versus high dosage) varied significantly by approval (β = −0.191 SD, p < 0.05). Among disapprovers, additional dosage had no significant effect, but it reduced election confidence significantly among approvers (β = −0.128 SD, p < 0.05).

The size of the effects reported in Figure 3 are worth emphasizing. The high-dose condition, which exposed respondents to just eight tweets, reduced confidence in the electoral system by 0.27 SDs among Republicans and 0.34 SDs among Trump approvers. Even if these treatment effects diminish over time, these results indicate that a sustained diet of exposure to such unfounded accusations could substantially reduce faith in the electoral system.

We also consider whether the effects of fact-check exposure vary between Democrats and Republicans. We find the marginal effect of exposure to fact-checks (comparing the low-dose + fact-check condition to the low-dose condition) does not vary significantly by party (H4b). As a result, the negative effects of the low-dose condition on trust and confidence in elections among Republicans (β = −0.184 SD, p < 0.01) persist if they are also exposed to fact-checks in the low-dose + fact-check condition (β = −0.176 SD, p < 0.05). This pattern replicates when we instead disaggregate by Trump support. We find no measurable difference in the effects of the fact-checks by Trump approval, but the low dose + fact-check reduces election confidence among Trump supporters (β = −0.190 SD, p < 0.005) despite the presence of corrective information, mirroring the effect in the low-dose condition (β = −0.211 SD, p < 0.005). Footnote 10

Finally, we explore whether these treatments affect broader attitudes toward democracy itself. Table C4 in Online Appendix C shows that the effects of the low and high dosage voter-fraud treatments were overwhelmingly null on “Having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Congress and elections,” “Having experts, not government, make decisions,” “Having the army rule,” “Having a democratic political system,” and the perceived importance of living in a country that is governed democratically. Footnote 11 These null effects were mirrored in analyses of heterogeneous treatment effects by party and Trump approval in Online Appendix C.

Conclusion

This study presents novel experimental evidence of the effect of unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud on public confidence in elections. Using a large, nationally representative sample collected after the 2018 US elections, we show that respondents exposed to either low or high doses of voter-fraud claims reported less confidence in elections than those in a placebo condition, though there was no evidence that the treatments affected attitudes toward democracy more generally. These effects varied somewhat by party. Exposure significantly reduced confidence in elections only among Republicans and Trump supporters, though these effects only differed measurably by party or Trump approval in the high-dosage condition.

Worryingly, we found little evidence that fact-check tweets measurably reduced the effects of exposure to unfounded voter-fraud allegations. Adding corrections to the low-dose condition did not measurably reduce the effects of exposure. As a result, both Republicans and Trump approvers reported significantly lower confidence in elections after exposure to a low dose of voter-fraud allegations even when those claims were countered by fact-checks (compared to those in a placebo condition). These findings reinforce previous research on the potential lasting effects of exposure to misinformation even after it is discredited (e.g., Thorson Reference Thorson2016). Our findings also contribute to the growing understanding of the seemingly powerful role of elites in promoting misinformation (Weeks and Gil de Zúñiga Reference Weeks and Gil de Zúñiga2019) and other potentially damaging outcomes such as conspiracy beliefs (Enders and Smallpage Reference Enders and Smallpage2019) and affective polarization (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019).

Future work could address a number of limitations in our study and build on our findings in several important ways. First, our treatment and dosage designs were solely based on social media posts. Additional research could explore whether media reports or editorials echoing accusations from political elites have greater effects (e.g., Coppock et al. Reference Coppock, Ekins and Kirby2018). Second, journalistic corrections could likewise be strengthened. Corrections from in-group media may be more influential; in the present case, dismissal of fraud claims by outlets like The Weekly Standard or The Daily Caller could be more credible among Republican respondents. Similarly, dismissals from prominent Republican officials themselves might be more influential as they signal intra-party disagreement (Lyons Reference Lyons2018) – a costly signal, particularly for those who have shifted positions on the issue (Baum and Groeling Reference Baum and Groeling2009; Benegal and Scruggs Reference Benegal and Scruggs2018; Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Hasell, Tallapragada and Jamieson2019). However, such messengers may alternatively be subject to negative evaluation by way of a “black sheep effect” (Matthews and Dietz-Uhler Reference Matthews and Dietz-Uhler1998) and could be less effective for Republicans in particular (Agadjanian Reference Agadjanian2020). Third, our study examines messages that were congenial for Republicans. Though we sought to test the effects of fraud claims from the sources who have most frequently made them, a future study should also test the congeniality hypotheses we develop using Democrats as well.

While our data focuses on the US case, we strongly encourage future work to examine both the prevalence of electoral fraud claims and the effects of such claims comparatively. We suspect that there is important cross-national variation in how frequently illegitimate electoral fraud claims are made. While we would expect our central finding – exposure to elite messages alleging voter fraud undermines confidence in elections – would be replicated in other locales, there may be important nuance or scope conditions that additional cases would help reveal. For instance, variation in electoral rules and candidates’ resulting relative dependence on the media to communicate with voters may shape the nature of fraud claims themselves (Amsalem et al. Reference Amsalem, Sheafer, Walgrave, Loewen and Soroka2017). Journalistic fact-checking may be generally more effective in countries with less polarized attitudes toward the media (Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Mérola, Reifler and Stoeckel2020). Moreover, variation in party systems may affect the consequences to party elites face for making fraudulent claims; when parties control ballot access, it may be easier to constrain problematic rhetoric in the first place (Carson and Williamson Reference Carson and Williamson2018). In addition, proportional representation (PR) systems may change the strategic calculus of using rhetoric that attacks election legitimacy because losing parties still may have access to power through coalition bargaining (and voters in PR systems may be able to more easily punish norm violations by defecting to ideologically similar parties). Finally, many countries have dramatically more fluid party attachments than the USA; when party attachment is consistently weaker (Huddy, Bankert and Davies Reference Huddy, Bankert and Davies2018), fraud claims may simply carry less weight.

It is also important to consider the potential for expressive responding (Schaffner and Luks Reference Schaffner and Luks2018) (but see Berinsky Reference Berinsky2018), which future work might rule out by soliciting higher stakes outcomes of interest (e.g., willingness to pay additional taxes to improve election security). Future research could also test the effects of allegations in a pre-election context and possibly examine effects on turnout or participation intentions. Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the importance of considering the effect of fraud allegations directed at mail voting and ballot counting, which may be especially vulnerable to unfounded allegations.

Still, our study provides new insight into the effects of unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud. We demonstrate that these allegations can undermine confidence in elections, particularly when the claims are politically congenial, and may not be effectively mitigated by fact-checking. In this way, the proliferation of unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud threatens to undermine confidence in electoral integrity and contribute to the erosion of US democracy.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2021.18

Data availability

The data, code, and any additional materials required to replicate all analyses in this article are available at the Journal of Experimental Political Science Dataverse within the Harvard Dataverse Network, at: doi: 10.7910/DVN/530JGJ.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.