Personal recovery has been defined as ‘a deeply personal, unique process of changing one’s attitudes, values, feelings, goals, skills and/or roles… a way of living a satisfying, hopeful and contributing life even with the limitations caused by illness’. Reference Anthony1 A recovery orientation is mental health policy in most Anglophone countries. For example, the mental health plan for England 2009–2019 has the ‘expectation that services to treat and care for people with mental health problems will be… based on the best available evidence and focused on recovery, as defined in discussion with the service user’. Reference Government2 The implications of a recovery orientation for working practice are unclear, and guidelines for developing recovery-oriented services are only recently becoming available. Reference Davidson, Tondora, Lawless, O'Connell and Rowe3,Reference Slade4 Comprehensive reviews of the recovery literature have concluded that there is a need for conceptual clarity on recovery. Reference Silverstein and Bellack5,Reference Warner6 Current approaches to understanding personal recovery are primarily based on qualitative research Reference Davidson, Schmutte, Dinzeo and Andres-Hyman7 or consensus methods. 8 No systematic review and synthesis of personal recovery in mental illness has been undertaken.

The aims of this study were (a) to undertake the first systematic review of the available literature on personal recovery and (b) to use a modified narrative synthesis to develop a new conceptual framework for recovery. A conceptual framework, defined as ‘a network, or a plane, of interlinked concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon or phenomena’, Reference Jabareen9 provides an empirical basis for future recovery-oriented research and practice.

Method

Eligibility criteria

The review sought to identify papers that explicitly described or developed a conceptualisation of personal recovery from mental illness. A conceptualisation of recovery was defined as either a visual or narrative model of recovery, or themes of recovery, which emerged from a synthesis of secondary data or an analysis of primary data. Inclusion criteria for studies were:

-

(a) contains a conceptualisation of personal recovery from which a succinct summary could be extracted;

-

(b) presented an original model or framework of recovery;

-

(c) was based on either secondary research synthesising the available literature or primary research involving quantitative or qualitative data based on at least three participants;

-

(d) was available in printed or downloadable form;

-

(e) was available in English.

Exclusion criteria were:

-

(a) studies solely focusing on clinical recovery Reference Slade4 (i.e. using a predefined and invariant ‘getting back to normal’ definition of recovery through symptom remission and restoration of functioning);

-

(b) studies involving modelling of predictors of clinical recovery;

-

(c) studies defining remission criteria or recovery from substance misuse, addiction or eating disorders;

-

(d) dissertations and doctoral theses (because of availability).

Search strategy and data sources

Three search strategies were used to identify relevant studies: electronic database searching, hand-searching and web-based searching.

Electronic database searching

Twelve bibliographic databases were initially searched using three different interfaces: Applied and Complimentary Medicine Database (AMED); British Nursing Index; EMBASE; MEDLINE; PsycINFO; Social Science Policy (accessed via OVID SP); CINAHL; International Bibliography of Social Science (accessed via EBSCOhost); Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ASSIA); British Humanities Index; sociological abstracts; and Social Services abstracts (accessed via CSA Illumina). All databases were searched from inception to September 2009 using the following terms identified from the title, abstract, keywords or medical subject headings: (‘mental health’ OR ‘mental illness$’ OR ‘mental disorder’ OR mental disease’ OR ‘mental problem’) AND ‘recover$’ AND (‘theor$’ OR ‘framework’ OR ‘model’ OR ‘dimension’ OR ‘paradigm’ OR ‘concept$’). The search was adapted for the individual databases and interfaces as needed. For example, CSA Illumina only allows the combination of three ‘units’ each made up of three search terms at any one time, for example (‘mental health’ OR ‘mental illness*’ OR ‘mental disorder’) AND ‘recover*’ AND (‘theor$’ OR ‘framework’ OR ‘concept’). As a sensitivity check, ten papers were identified by the research team as highly influential, based on number of times cited and credibility of the authors (included papers 3, 9, 10, 19, 29, 34, 35, 40, 68 and 75 in online Table DS1). These papers were assessed for additional terms, subject headings and key words, with the aim of identifying relevant papers not retrieved using the original search strategy. This led to the use of the following additional search terms: (‘psychol$ health’ OR ‘psychol$ illness$’ OR ‘psychol$ disorder’ OR psychol$ problem’ OR ‘psychiatr$ health’, OR psychiatr$ illness$’ OR ‘psychiatr$ disorder’ OR ‘psychiatr$ problem’) AND ‘recover$’ AND (‘theme$’ OR ‘stages’ OR ‘processes’). Duplicate articles were removed within the original database interfaces using Reference Manager Software Version 11 for Windows.

Hand-searching

The tables of contents of journals which published key articles (Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, British Journal of Psychiatry and American Journal of Psychiatry) and recent literature reviews of recovery (included papers 4, 37 and 89 in online Table DS1) were hand-searched.

Web-based searching

Web-based resources were identified by internet searches using Google and Google Scholar and through searching specific recovery-oriented websites (Scottish Recovery Network: www.scottishrecovery.net; Boston University Repository of Recovery Resources: www.bu.edu/cpr/repository/index.html; Recovery Devon: www.recoverydevon.co.uk; and Social Perspectives Network: www.spn.org.uk).

Data extraction and quality assessment

One rater (V.B.) extracted data and assessed the eligibility criteria for all retrieved papers, with a random subsample of 88 papers independently rated by a second rater (J.W. or C.L.B.). Disagreements between raters were resolved by a third rater (M.L.). Acceptable concordance was predefined as agreement on at least 90% of ratings. A concordance of 91% was achieved. Data were extracted and tabulated for all papers rated as eligible for the review.

Included qualitative papers were initially quality assessed by three raters (V.B., J.W. and C.L.B.) using the RATS (relevance, appropriateness, transparency, soundness) qualitative research review guidelines. Reference Clark, Godlee and Jefferson10 The RATS scale comprises 25 questions about the relevance of the study question, appropriateness of qualitative method, transparency of procedures, and soundness of interpretive approach. In order to make judgements about quality of papers, we dichotomised each question to yes (1 point) or no (0 points), giving a scale ranging from 0 (poor quality) to 25 (high quality). A random subsample of ten qualitative studies were independently rated using the RATS guidelines by a second rater (M.L.). The mean score from rating 1 was 14.8 and from rating 2 was 15.1, with a mean difference in ratings of 0.3 indicating acceptable concordance. The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) 11 quality assessment tool for quantitative studies was used to rate the two quantitative studies. Independent ratings were made by two reviewers (V.B. and M.L.) of Ellis & King Reference Ellis and King12 and Resnick et al, Reference Resnick, Fontana, Lehman and Rosenheck13 who agreed on rating both papers as moderate.

Data analysis

The conceptual framework was developed using a modified narrative synthesis approach. Reference Popay, Roberts, Sowden, Petticrew, Arai and Rodgers14 The three stages of the narrative synthesis comprised: (1) developing a preliminary synthesis; (2) exploring relationships within and between studies; and (3) assessing the robustness of the synthesis. For clarity, the development of the conceptual framework (Stages 1 and 3) is presented in the Results before the subgroup comparison (Stage 2).

Stage 1: developing a preliminary synthesis

A preliminary synthesis was developed using tabulation, translating data through thematic analysis of good-quality primary data, and vote counting of emergent themes. For each included paper, the following data were extracted and tabulated: type of paper, methodological approach, participant information and inclusion criteria, study location, and summary of main study findings. An initial coding framework was developed and used to thematically analyse a subsample of qualitative research studies with the highest RATS quality rating (i.e. RATS score of 15 or above), using NVIVO QSR International qualitative analysis software (Version 8) for Windows. The main overarching themes and related subthemes occurring across the tabulated data were identified, using inductive, open coding techniques. Additional codes were created by all analysts where needed and these new codes were regularly merged with the NVIVO master copy, and then this copy was shared with other analysts, so all new codes were applied to the entire subsample.

Finally, once the themes had been created, vote counting was used to identify the frequency with which themes appeared in all of the 97 included papers. The vote count for each category comprised the number of papers mentioning either the category itself or a subordinate category. On completion of the thematic analysis and vote counting, the draft conceptual framework was discussed and refined by all authors. Some new categories were created, and others were subsumed within existing categories, given less prominence or deleted. This process produced the preliminary conceptual framework.

Stage 2: exploring relationships within and between studies

Papers were identified from the full review which reported data from people from Black and minority ethnic (BME) backgrounds. These papers were thematically analysed separately, and the emergent themes compared with the preliminary conceptual framework. The thematic analysis utilised a more fine-grained approach, in which a second analyst (V.B.) went through the papers in a detailed and line-by-line manner. The aim of the subgroup analysis was to specifically identify any additional themes as well as any difference in emphasis placed on areas of the preliminary framework. Thus, our purpose was to identify areas of different emphasis in this subgroup of studies, not to perform a validity check.

Stage 3: assessing robustness of the synthesis

Two approaches were used to assess the robustness of the synthesis. First, qualitative studies which were rated as moderate quality on the RATS scale (i.e. RATS score of 14) were thematically analysed until category saturation was achieved. The resulting themes were then compared with the preliminary conceptual framework developed in Stages 1 and 2. Second, the preliminary conceptual framework was sent to an expert consultation panel. The panel comprised 54 advisory committee members of the REFOCUS Programme (see www.researchintorecovery.com for further details) who had academic, clinical or personal expertise about recovery. They were asked to comment on the positioning of concepts within different hierarchical levels of the conceptual framework, identify any important areas of recovery which they felt had been omitted and make any general observations. The preliminary conceptual framework was modified in response to these comments, to produce the final conceptual framework.

Results

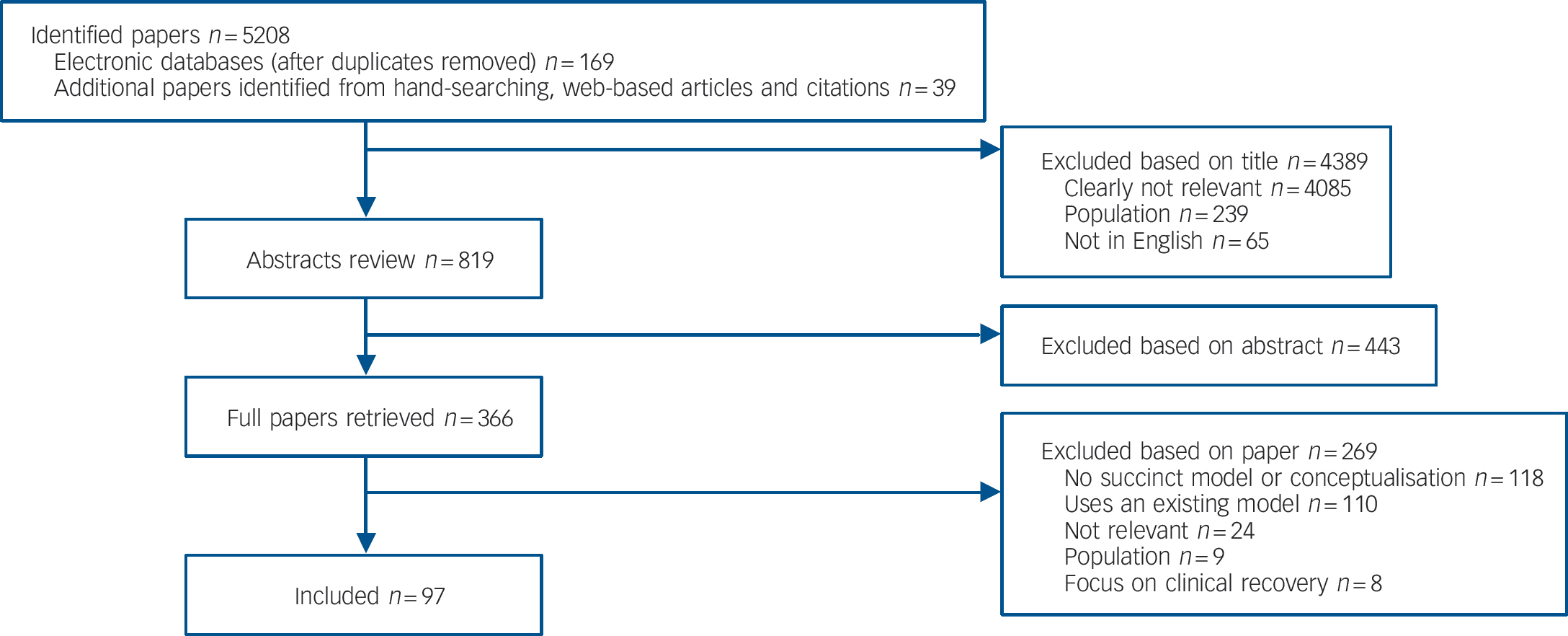

The flow diagram for the 97 included papers is shown in Fig. 1 and online Table DS1 lists those papers that were included.

The 97 papers comprised qualitative studies (n = 37), narrative literature reviews (n = 20), book chapters (n = 7), consultation documents reporting the use of consensus methods (n = 5), opinion pieces or editorials (n = 5), quantitative studies (n = 2), combining of a narrative literature review with personal opinion or where there is insufficient information on method for a judgement to be made (n = 11), and elaborations of other identified papers (n = 10). In summary, 87 distinct studies were identified. The ten elaborating papers included in the thematic analysis but not in the vote counting were papers 11, 15, 16, 19, 26, 48, 50, 53, 71 and 73 in online Table DS1.

The 97 papers described studies conducted in 13 countries, including the USA (n = 50), the UK (n = 20), Australia (n =8) and Canada (n = 6). Participants were recruited from a range of settings, including community mental health teams and facilities, self-help groups, consumer-operated mental health services and supported housing facilities. The majority of studies used inclusion criteria that covered any diagnosis of severe mental illness. A few studies only included participants who had been diagnosed with a specific mental illness (e.g. schizophrenia, depression). The sample sizes in qualitative data papers ranged from 4 to 90 participants, with a mean sample size of 27.

Fig. 1 Flow chart to show assessment of eligibility of identified studies.

The sample sizes in the two quantitative papers were 19 Reference Ellis and King12 and 1076. Reference Resnick, Fontana, Lehman and Rosenheck13 The former was a pilot study of 15 service users with experience of psychotic illness and 4 case managers using the Recovery Interventions Questionnaire, carried out in Australia. The latter study analysed data from two sources, the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey, which examined usual care in a random sample of people with schizophrenia in two US states, and an extension to this survey which provided a comparison group.

There were various approaches to determining the stage of recovery of participants. Most studies rated stage of recovery using criteria such as: the person defined themselves as ‘being in recovery’; not hospitalised during the previous 12 months; relatively well and symptom free; providing peer support to others; or working or living in semi-independent settings. Only a few studies specifically used professional opinion – clinical judgement or scores on clinical assessments – about whether people had recovered.

The mean RATS score for the 36 qualitative studies was 14.9 (range 8–20). One qualitative study was not rated using the RATS guidelines because there was insufficient information on methodology within this paper. A RATS score of 15 or above, indicating high quality, was obtained by 16 papers and used to develop a preliminary synthesis. A RATS score of 14, indicating moderate quality, was obtained by five papers. Independent ratings were made of the two quantitative papers, Ellis & King Reference Ellis and King12 and Resnick et al, Reference Resnick, Fontana, Lehman and Rosenheck13 which were rated as moderate by two reviewers (V.B. and M.L.). Given this quality assessment, no greater weight was put on the quantitative studies in developing the category structure.

Conceptual framework for personal recovery

A preliminary conceptual framework was developed, which comprised five superordinate categories: values of recovery, beliefs about recovery, recovery-promoting attitudes of staff, constituent processes of recovery, and stages of recovery.

The robustness of the synthesis underpinning the preliminary conceptual framework was assessed in two steps: by re-analysing a subsample of qualitative studies and through expert consultation.

Subsample re-analysis

In addition to the higher-quality qualitative studies analysed in the preliminary synthesis stage, an additional five moderate-quality (RATS score of 14) qualitative studies were analysed, which confirmed that category saturation had been achieved, indicating that the categories are robust.

Expert consultation

A response was received from 23 (43%) of the 54 consulted experts with international and national academic, clinical, and/or personal expertise and experiences of recovery, who are advisory committee members of the REFOCUS programme into recovery. Responses were themed under the following headings: conceptual (dangers of reductionism, separating processes from stages, confusing critical impetus for behaviours with actual behaviour, limitations of stage models); structural (complete omissions, lack of emphasis or overemphasis on specific areas of recovery); language (too technical); and bias (potential geographical bias). In response to this consultation, the preliminary conceptual framework was simplified, so the final conceptual framework now has three rather than five superordinate categories. Some subcategories were repositioned within recovery processes, and some category headings changed. Some responses identified areas of omission, such as the role of past trauma, hurt and physical health in recovery. However, no alteration was made to the conceptual framework as these did not emerge from the thematic analysis. Other points regarding the strengths and limitations of the framework are addressed in the Discussion. Overall, the expert consultation process provided a validity check on content of conceptual framework, although we were careful not to make radical changes which would have been unjustified, given the weight of evidence provided from preliminary analysis of the included papers.

The final conceptual framework comprises three interlinked, superordinate categories: characteristics of the recovery journey; recovery processes; and recovery stages.

Characteristics of the recovery journey were identified in all 87 studies, and vote-counting was used to indicate their frequency (Table 1).

The categories of recovery processes and their vote counts, indicating frequency of the process being identified, for the two highest category levels are shown in Table 2.

The full description of recovery processes categories and the vote counting results are shown in online Table DS2.

Table 1 Characteristics of the recovery journey

| Characteristics | Number (%) of 87 studies identifying the characteristics |

|---|---|

| Recovery is an active process | 44 (50) |

| Individual and unique process | 25 (29) |

| Non-linear process | 21 (24) |

| Recovery as a journey | 17 (20) |

| Recovery as stages or phases | 15 (17) |

| Recovery as a struggle | 14 (16) |

| Multidimensional process | 13 (15) |

| Recovery is a gradual process | 13 (15) |

| Recovery as a life-changing experience | 11 (13) |

| Recovery without cure | 9 (10) |

| Recovery is aided by supportive and healing environment | 6 (7) |

| Recovery can occur without professional intervention | 6 (7) |

| Trial and error process | 6 (7) |

Fifteen studies developed recovery stage models. The studies were organised using the transtheoretical model of change, Reference Prochaska and DiClemente15 as shown in Table 3.

Recovery in individuals of BME origin

As part of Stage 2 of the narrative synthesis process, six studies of recovery from the perspective of individuals of BME origin were identified within the 87 studies. These six studies were re-analysed by a second analyst (V.B.), using a more fine-grained, line-by-line approach to thematic analysis. These comprised a survey of 50 recipients of a community development project in Scotland, 16 a qualitative interview study of African Americans, Reference Armour, Bradshaw and Roseborough17 a narrative literature review, Reference Nicholls18 a qualitative study of 40 Maori and non-Maori New Zealanders, Reference Lapsley, Nikora and Black19 a pilot study to test whether the Recovery Star measure was applicable to Black and Asian ethnic minority populations 20 and a mixed method study of 91 males from African–Caribbean backgrounds. Reference Brown, Essien and Etim-Ubah21 These papers provide some preliminary insights into a small number of distinct ethnic minority perspectives, which do not represent a culturally homogeneous group, although some similarities in experience can be observed. Although these six papers were included in the vote-counting process, four of the six BME papers 16–Reference Nicholls18,20 were not used in the first-stage thematic analysis. The line-by-line secondary analysis allowed us to explore in greater detail any differences in emphasis and additional themes present in these papers.

The main finding of the subgroup analysis indicated that there was substantial similarity between studies focusing on ethnic minority communities and those focusing on ethnic majority populations. All of the themes of the conceptual framework were present in all six of the BME papers. Despite this overall similarity, there was a greater emphasis in the BME papers on two areas in the recovery processes: spirituality and stigma; and two additional

Table 2 Recovery processes

| Recovery processes | Number (%) of 87 studies identifying the process |

|---|---|

| Category 1: Connectedness | 75 (86) |

| Peer support and support groups | 39 (45) |

| Relationships | 33 (38) |

| Support from others | 53 (61) |

| Being part of the community | 35 (40) |

| Category 2: Hope and optimism about the future | 69 (79) |

| Belief in possibility of recovery | 30 (34) |

| Motivation to change | 15 (17) |

| Hope-inspiring relationships | 12 (14) |

| Positive thinking and valuing success | 10 (11) |

| Having dreams and aspirations | 7 (8) |

| Category 3: Identity | 65 (75) |

| Dimensions of identity | 8 (9) |

| Rebuilding/redefining positive sense of identity | 57 (66) |

| Overcoming stigma | 40 (46) |

| Category 4: Meaning in life | 59 (66) |

| Meaning of mental illness experiences | 30 (34) |

| Spirituality | 6 (41) |

| Quality of life | 57 (65) |

| Meaningful life and social roles | 40 (46) |

| Meaningful life and social goals | 15 (17) |

| Rebuilding life | 19 (22) |

| Category 5: Empowerment | 79 (91) |

| Personal responsibility | 79 (91) |

| Control over life | 78 (90) |

| Focusing upon strengths | 14 (16) |

Table 3 Recovery stages mapped onto the transtheoretical model of change

| Table DS1 study number | Precontemplation | Contemplation | Preparation | Action | Maintenance and growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32 | Novitiate recovery – struggling with disability | Semi-recovery – living with disability | Full recovery – living beyond disability | ||

| 73 | Stuck | Accepting help | Believing | Learning | Self-reliant |

| 3 | Descent into hell | Igniting a spark of hope | Developing insight/activating instinct to fight back | Discovering keys to well-being | Maintaining equilibrium between internal and external forces |

| 44 | Demoralisation | Developing and establishing independence | Efforts towards community integration | ||

| 36 | Occupational dependence | Supported occupational performance | Active engagement in meaningful occupations | Successful occupational performance | |

| 14 | Dependent/unaware | Dependent/aware | Independent/aware | Interdependent/aware | |

| 29 | Moratorium | Awareness | Preparation | Rebuilding | Growth |

| 78 | Glimpses of recovery | Turning points | Road to recovery | ||

| 61 | Reawakening of hope after despair | No longer viewing self as primarily person with psychiatric disorder | Moving from withdrawal to engagement | Active coping rather than passive adjustment | |

| 40 | Overwhelmed by the disability | Struggling with the disability | Living with the disability | Living beyond the disability | |

| 35 | Initiating recovery | Regaining what was lost/moving forward | Improving quality of life | ||

| 59 | Crisis (recuperation) | Decision (rebuilding independence) | Awakening (building healthy interdependence) | ||

| 43 | Turning point | Determination | Self-esteem |

categories: culture-specific factors and collectivist notions of recovery.

In relation to spirituality, being part of a faith community and having a religious affiliation was seen as an important component of an individual’s recovery. People from ethnic minority groups more often described spirituality in terms of religion and a belief in God as a higher power, whereas participants in the non-BME studies tended to conceptualise spirituality as encompassing a wider range of beliefs and activities.

In relation to stigma, BME studies emphasised the stigma associated with race, culture and ethnicity, in addition to the stigma associated with having a mental illness. Furthermore, being an individual from a minority ethnic group seemed to accentuate the stigma of mental illness, as the person often viewed themselves as belonging to multiple stigmatised and disadvantaged groups. Individuals from ethnic minority groups saw themselves as recovering from racial discrimination, stigma and violence, and not just from a period of mental illness.

The new category of culture-specific factors included the use of traditional therapies and faith healers, and belonging to a particular cultural group or community. Finally, collectivist notions of recovery were emphasised as both positive and negative factors. Many individuals discussed the hope and support they received from their collectivist identity, but for others the community added to the pressures of mental illness. This was particularly true where communities lacked information and awareness regarding mental illness. Furthermore, the negative impact of the community was felt not only at the level of the individual, but also at the collectivist level, with the whole family being adversely affected by stigma.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review and narrative synthesis of personal recovery. A conceptual framework was developed using a narrative synthesis which identified three superordinate categories: characteristics of the recovery journey, recovery processes and recovery stages. For each superordinate category, key dimensions were synthesised. The recovery processes that have the most proximal relevance to clinical research and practice are: connectedness; hope and optimism about the future; identity; meaning in life; and empowerment (giving the acronym CHIME). The robustness of the category structure was enhanced by the systematic nature of the review, the quality assessment of included studies, the category saturation reached in the analysis, and the content validity of the expert consultation. Heterogeneity between studies was explored descriptively. A subgroup comparison between the experiences of recovery from the perspective of individuals of BME origin identified similar themes, with a greater emphasis on spirituality and stigma, and two additional themes: culture-specific factors, and collectivist notions of recovery.

Implications for research and practice

Key knowledge gaps have been identified as the need for clarity about the underpinning philosophy of recovery, Reference Dinniss22 better understanding of the stages and processes of recovery, Reference Silverstein and Bellack5 and valid measurement tools. 23 This study can inform each of these gaps.

Recovery has been conceptualised as a vision, a philosophy, a process, an attitude, a life orientation, an outcome and a set of outcomes. Reference Silverstein and Bellack5 This has led to the concern that ‘its scope can make a cow-catcher on the front of a road train look discriminating’. Reference Brunskill24 An empirically based conceptual framework can bring some order to this potential chaos. Characteristics of the recovery journey provide conceptual clarity about the philosophy. Recovery processes can be understood as measurable dimensions of change, which typically occur during recovery and provide a taxonomy of recovery outcomes. Reference Slade25 Finally, recovery stages provide a framework for guiding stage-specific clinical interventions and evaluation strategies.

The framework contributes to the understanding about stages and processes of recovery in two ways. First, it allows available evidence to be more easily identified. A recovery orientation has overlap with the literature on well-being, Reference Hanlon and Carlisle26 positive psychology Reference Slade27 and self-management, Reference Sterling, von Esenwein, Tucker, Fricks and Druss28 and systematic reviewing is hampered by the absence of relevant MeSH (Medical Sub-Headings) headings relating to recovery concepts. The coding framework provides keywords for use when undertaking secondary research, and the identification of related terms provides a taxonomy which will be useable in reviews.

Second, the framework provides a structure around which research and clinical efforts can be oriented. The relative contribution of each recovery process, investigating interventions which can support these processes, and the synchrony between recovery processes and stages are all testable research questions. For clinical practice, the CHIME recovery processes support reflective practice. If the goal of mental health professionals is to support recovery then one possible way forward is for each working practice to be evaluated in relation to its impact on these processes. This has the potential to contribute to current debates about recovery and, for example, assertive outreach, Reference Drake and Deegan29 risk Reference Young, Green and Estroff30 and community psychiatry. Reference Rosen31

Finally, the conceptual framework can contribute to the development of measures of personal recovery. Compendia of existing measures have been developed, Reference Campbell-Orde, Chamberlin, Carpenter and Leff32,33 showing that the conceptual basis of measures is diverse. The conceptual framework provides a foundation for developing standardised recovery measures, and is the basis for a new measure currently being developed by the authors to evaluate the contribution of mental health services to an individual’s recovery. The challenge will then be to incorporate a focus on recovery outcomes and associated concepts such as well-being Reference Slade27 into routine clinical practice. Reference Slade34

Limitations

The study has three methodological and two conceptual limitations. The first methodological limitation is that the narrative synthesis approach was modified, and could have been widened. For example, the exploration in Stage 2 of relationships between studies could have considered the subgroup of studies which had higher levels of consumer involvement in their design, but it proved impossible to reliably rate identified studies in this dimension. The second technical limitation is that the emergent categories were only one way of grouping the findings, and the categories changed as a result of expert consultation. In particular, the three superordinate categories are not separate, since processes clearly occur within the identified stages, and the characteristics of recovery describe an overall movement through stages of recovery. Our categorical separation brings structure, but a replication study may not arrive at the same overall thematic structure. The final technical limitation is that analysis synthesised the interpretation of the primary data in each paper rather than considering the primary data directly. Future research could compare papers generated by different stakeholder groups, such as consumer researchers, clinical researchers and policy makers.

The first conceptual limitation is that this review, although synthesising the current literature on personal recovery, should not be seen as definitive. A key scientific challenge is that the philosophy of recovery gives primacy to individual experience and meaning (‘idiographic’ knowledge), whereas mental health systems and current dominant scientific paradigms give prominence to group-level aggregated data (‘nomothetic’ knowledge). Reference Slade4 The practical impact is that current recovery research is primarily focused at the bottom of the hierarchy of evidence. Reference Onken, Craig, Ridgway, Ralph and Cook35 This was our finding, with qualitative, case study and expert opinion methodologies dominating. A motivator for the current study was to provide evidence of the form viewed as high quality within the current scientific paradigm, but several of our expert consultants highlighted the dangers of closing down discourse. Since recovery is individual, idiosyncratic and complex, this review is not intended to be a rigid model of what recovery ‘is’. Rather, it is better understood as a resource to inform future research and clinical practice. The second conceptual limitation relates to the subgroup analysis looking at papers focusing on non-majority populations. Owing to a lack of research, it was not possible to look at the experience and perspectives of individuals from different ethnic minority groups. Therefore, the BME subgroup represents a heterogeneous and incredibly diverse set of populations. However, it was felt that all the populations included in these papers shared a common experience of belonging to an ethnic minority group, and that this experience may have important implications for the meaning of personal recovery, and for the experience of mental health services in general. The lack of data, coupled with the areas of difference found in the present review, highlights a need for further work to be conducted with people from ethnic minority communities.

Future research

This systematic review and narrative synthesis has highlighted the dominance of recovery literature emanating from the USA. Culturally, the USA neglects character strengths such as patience and tolerance, Reference Henry, Haworth and Hart36 and favours individualistic over collectivist understandings of identity. Although there were very few studies which looked at recovery experiences of individuals from BME backgrounds, the subsample of BME studies indicated that there are important differences in emphasis. There is a need for research involving more diverse samples of people from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds, at differing stages of recovery and experiencing different types of mental illness.

The complexity of personal recovery requires a range of theoretical inquiry positions. This review focused on research into first-person accounts of recovery, where individual meanings of recovery have dominated. This has led to a framework which may underemphasise the importance of the wider socioenvironmental context, including important aspects such as stigma and discrimination. Viewing recovery within an ecological framework, as suggested by Onken and colleagues, Reference Onken, Craig, Ridgway, Ralph and Cook35 encompasses an individual’s life context (characteristics of the individual such as hope and identity) as well as environmental factors (such as opportunities for employment and community integration) and the interaction between the two (such as choice). A more complete understanding of recovery requires greater attention to all these levels of understanding, for instance, how power is related to characteristics of individuals or groups (e.g. race and culture), how clinicians and patients interact at different stages of recovery and how these interactions change over time. There is also a need for future research to increase our understanding of how subtle micro-processes of recovery are operating, such as how hope is reawakened and sustained.

Supporting recovery processes may be the future mental health research priority. The 13 dimensions identified as characteristics of the recovery journey capture much of the experience and complexities of recovery, and further research may not have a high scientific pay-off. Similarly, although the recovery stages could be mapped onto the transtheoretical model of change, Reference Prochaska and DiClemente15 there was little consensus about the number of recovery phases. It may therefore be more helpful to undertake evaluative research addressing specific service-level questions (such as whether people using a service are making recovery gains over time Reference Miller, Brown, Pilon, Scheffler and Davis37 or in different service settings Reference Johnson, Gilburt, Lloyd-Evans, Osborn, Boardman and Leese38 ), rather than further studies seeking conceptual clarity. Overall, the emergent priority is the development and evaluation of interventions to support the five CHIME recovery processes. The subordinate categories point to the need for a greater emphasis on assessment of strengths and support for self-narrative development, promoting the role of mental health systems in developing inclusive communities enabling access to peer support as well as providing retreats, and clinical interaction styles which promote empowerment and self-management. The CHIME categories are potential clinical end-points for interventions, in contrast to the current dominance of clinical recovery end-points such as symptomatology or hospitalisation rates. They also provide a framework for empirical investigation of the relationship between recovery outcomes, using methodologies developed in relation to clinical outcomes. Reference Salvi, Leese and Slade39 This area of enquiry is currently small Reference Andresen, Caputi and Oades40 but an important priority if potential trade-offs between desirable outcomes are to be identified. Reference Slade and Hayward41

Orienting mental health services towards recovery will involve system transformation. Reference Shepherd, Boardman and Burns42 The research challenge is to develop an evidence base which simultaneously helps mental health professionals to support recovery and respects the understanding that recovery is a unique and individual experience rather than something the mental health system does to a person. This conceptual framework for personal recovery, which has been developed through a systematic review and narrative synthesis, provides a useful starting point for meeting this challenge.

Funding

This study was funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grant for Applied Research () awarded to the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, and in relation to the NIHR Specialist Mental Health Biomedical Research Centre at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Popay et al for giving us the unpublished guidance on narrative synthesis.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.