NIH’s National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) aims “to turn biomedical research discoveries into health solutions…through the application of translational science (TS) [1].” NCATS recently developed TS Principles [1,Reference Faupel-Badger, Vogel, Austin and Rutter2] based on information from its Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Education Core Competency Working Group and a publication regarding “The Fundamental Characteristics of a Translational Scientist [Reference Gilliland, White and Gee3],” to guide its education and training initiatives and to describe the knowledge, skills, and abilities necessary to facilitate translation across the TS Continuum [1].

The Translational Science Training (TST) TL1 Program at the University of Texas Health San Antonio was established in 2009 in affiliation with the Institute for the Integration of Medicine and Science – home for the institution’s CTSA – and offers TL1 support for multidisciplinary research and education for predoctoral and postdoctoral scientists.

In 2018, the TST/TL1 Program implemented several new strategies to better include and encourage research more broadly across the TS Continuum, including the addition of postdoctoral scientists and a clinically trained Program Co-Director, expansion of team science and community engagement programing, and targeted trainee recruitment from schools of nursing, dentistry, and allied health, in addition to medicine. The objective of this bibliometric analysis was to categorize publications of TST/TL1 trainees according to Surkis’ TS “T-types” (T0–T4) [Reference Surkis, Hogle and Diaz-Granados4] and to determine if the TST/TL1 Program exhibited a more diverse mix of T-types after the programmatic adjustments made in 2018.

Bibliometric information was gathered for all TST/TL1 trainees who participated in the program from 7/1/2009 to 12/31/2021 using PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar searches. Original research articles qualified for inclusion in this analysis when a TST/TL1 trainee was listed as a coauthor in any position and when the work was published after they were appointed to the TL1 training grant. Editorials, commentaries, and errata were excluded. One trained investigator independently reviewed the title and abstract for each published article and classified the article based on the T-type criteria outlined by Surkis et al [Reference Surkis, Hogle and Diaz-Granados4]. T-types were categorized as T0 (preclinical), T1/T2 (clinical), and T3/T4 (implementation/public health). A second trained investigator independently repeated the process for each article. When the first two independent ratings differed, a third trained investigator independently repeated the process. Once two independent ratings were the same, the classification process was complete. Percentages of publications belonging to the different T-types were plotted by publication year to assess if diversification of research occurred as time progressed in the TST/TL1 Program. Percentages were plotted by publication year, rather than TL1 cohort year, because trainees were appointed to the TL1 training grant for different lengths of time (including one trainee who was appointed in both the pre- and post-periods). Also, many TST/TL1 Program activities were open to all predoctoral and postdoctoral scientists, and it was common for them to participate in TST/TL1 Program activities before and after they were officially appointed to the TL1 training grant. The TST/TL1 Program design at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio might differ from TL1 program designs at other institutions regarding how many program activities are open to all, even if they are not officially appointed to the TL1 grant.

Publications were subsequently divided into pre- (2009–2017) and post- (2018–2021) periods to assess differences in T-types before and after the program modifications. Groups were compared using chi-square and Fisher’s exact statistical tests.

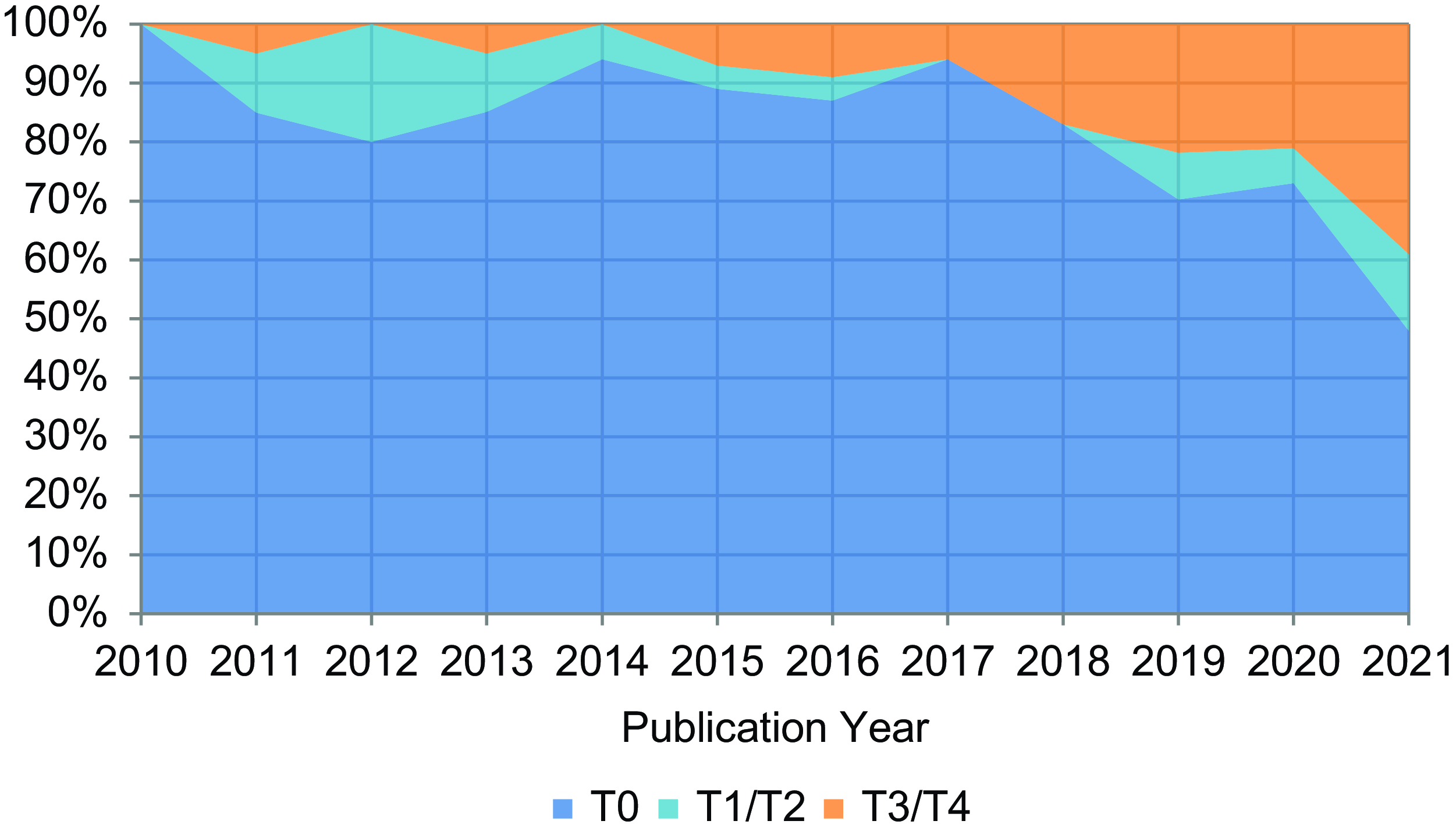

Overall, 494 publications from 77 TST/TL1 trainees were included in this analysis. In 2010, 100% of publications by trainees were T0; however, by 2021, over half of the publications by trainees were other T-types (Fig. 1): T0 (48%), T1/T2 (13%), and T3/T4 (39%). When comparing T-types for the publications in the pre- (2009–2017) and post- (2018–2021) periods, the percentage of T0 publications was significantly lower in the post-period (89% vs 66%, p < 0.01), the percentage of T1/T2 was similar in both periods (6% vs 8%, p = 0.48), and the percentage of T3/T4 publications was higher in the post-period (5% vs 27%, p < 0.01).

Figure 1. Annual distribution of TST/TL1 trainee publications by T-type.

The Translational Science Training (TST)/TL1 Program experienced a shift in T-type, from mostly T0 (preclinical) to more T3/T4 (clinical implementation/public health) research, after new strategies were implemented. A 2019 survey of TL1 programs by Sancheznieto et al [Reference Sancheznieto, Sorkness and Attia5] reported that predoctoral programs were more likely to have trainees engaged in basic (51% vs 43%) and T0 (preclinical) (76% vs 65%) research, but less likely to have trainees engaged in T1/T2 (clinical) (76% vs 89%), T3 (implementation) (61% vs 68%), and T4 (public health) (61% vs 65%) research, as compared to postdoctoral programs. This suggests that the inclusion of postdoctoral trainees in the TST/TL1 Program (0% in the pre-period and 31% in the post-period) contributed to the greater diversity of T-types in the post-period. These two studies underscore the need for NCATS to continue supporting TL1/T32 postdoctoral training programs if these programs are to produce trainees who work along the TS Continuum.

The findings of this analysis suggest that strategic programmatic adjustments, such as the inclusion of postdoctoral trainees, were associated with a more diverse mix of TS activity in the post-period, thereby helping the TST/TL1 Program at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio to better reflect research along the TS Continuum.

Acknowledgments

The TST/TL1 program directors wish to thank all trainees for their participation.

Competing interests

All others declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding statement

This work was funded in part by NIH NCATS through Grant Awards Numbers TL1TR002647 and UL1TR002645 (McManus, Frei, Chun). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Institutes of Health, or the authors’ affiliated institutions.