There are two issues defining the current debate on the provision of secure services for women: women patients in mixed-gender units are vulnerable; and women in special hospitals do not require high secure care. Both the Department of Health and Women in Secure Hospitals (WISH) are eager to see the services for women improved. There is strong support for the development of single-gender units, but this has not been incorporated into a National Women's Mental Health Strategy nor clearly promoted by appropriate resource attention. The authors conducted a telephone survey, as part of a wider study, of medium secure units in England and Wales to determine the distribution of women patients and to explore the impact of the current debate on the provision of secure services for women. This paper presents results from the survey and discusses the implications of the findings.

The study

The authors wrote to all 39 NHS and private medium secure units listed in the Forensic Directory (Rampton Hospital, 1998), and one additional private unit that was not open when the directory was published, indicating that they would be contacted as part of a telephone survey. Clinical managers and ward managers were contacted initially but other members of staff were also contacted, as deemed appropriate by managers.

The telephone survey was conducted during a 6-month period (October 1999-March 2000). The contact people were asked four questions: the number of women patients on their unit; the total number of beds on the unit; the patient mix of the unit (single-gender v. mixed-gender; diagnosis of the patients — mental illness, learning disabilities and personality disorder; and the amount of contact with WISH. Spontaneous comments from respondents were recorded.

Findings

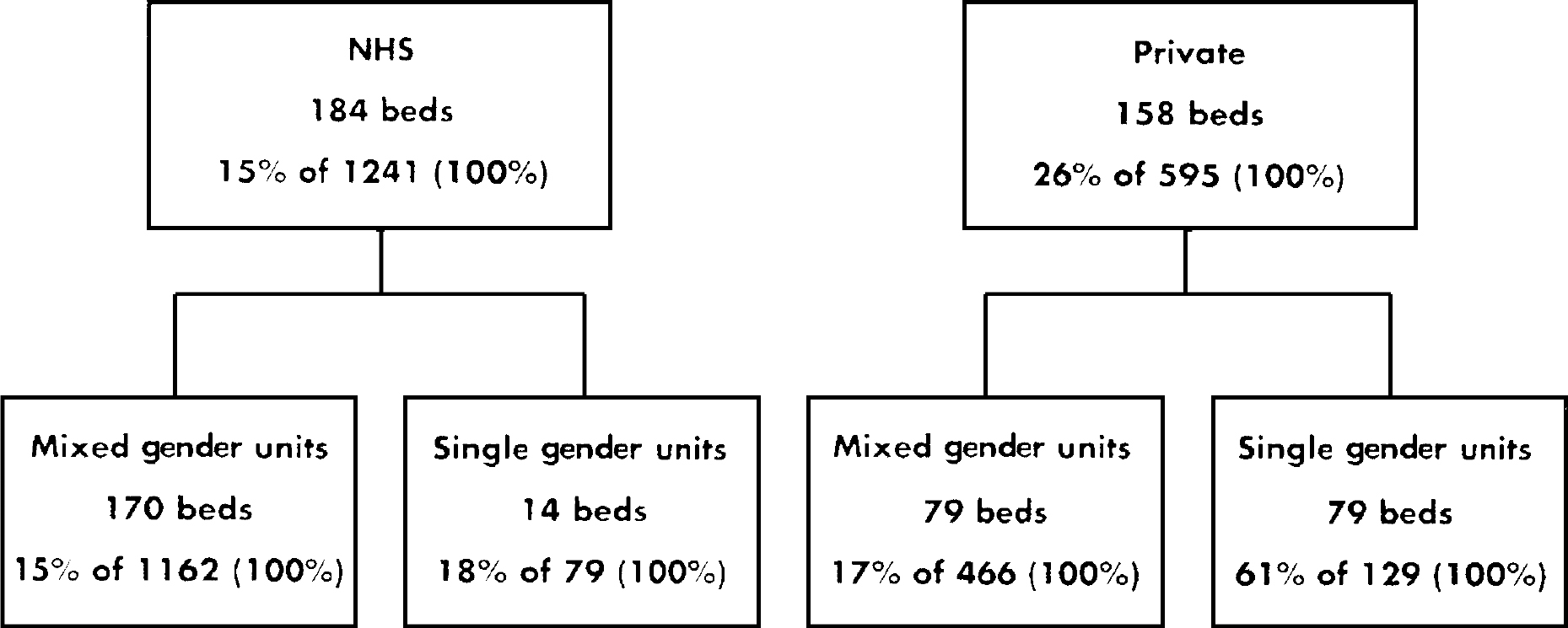

The telephone survey identified 1836 medium secure beds, 1628 beds in mixed-gender units and 208 beds in single-gender units. The Department of Health does not routinely publish figures on the number of medium secure beds, so a comparison was not possible. Three hundred and forty-two women patients were resident in the units at some point during the 6-month period. Despite the NHS providing twice as many beds as the private sector, women patients were distributed quite evenly across the NHS (184 women, 54%) and private units (158 women, 46%). Almost all women in the NHS were in mixed-gender units (170 women, 94%), most in adult mixed-gender units (134 women). Most NHS beds in single-gender units were for men (56 beds, 71%). There were 23 NHS beds for women in single-gender units, with most (78%, 18 beds) in personality disorder units. In contrast, the 158 women in the private sector were evenly distributed between mixed (79 women, 50%) and single-gender units (79 women, 50%). Sixty-eight of these 79 women were in mixed-diagnosis single-gender units (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 NHS and private medium secure beds occupied by women patients in mixed- and single-gender units (October 1999-March 2000). Those beds not occupied by women were either occupied by men or empty.

The survey also identified differences in the NHS and private sector's provision of services to adolescents (ages 15-21 years), aged (over 60 years old) and women patients with learning disabilities in mixed-gender units. Most beds (75%) in the NHS adolescent mixed-gender units were occupied by women, but only one-third (36%) in private adolescent mixed-gender units. In the NHS mixed-gender units for people with learning disabilities, women only occupied 18% of the beds compared with 46% of the beds in the private mixed-gender units for people with learning disabilities. A further difference was that in the private sector a separate mixed-gender unit was allocated to older adults, where women occupied 15% of the beds. The NHS units did not report a separate mixed-gender unit for older adults.

There were four units (two NHS and two private) that identified that they were either no longer accepting women patients or never did. Our NHS contacts noted that they”… were no longer accepting women patients because their unit was not considered a suitable environment”. One of the private units had a similar comment, but noted that they”… had plans to open a single-sex women's unit in 2001”. The other three spontaneous comments were about the rationale for where women patients had been housed in the unit and future plans for services. One contact at a NHS mixed-gender unit noted “that it was staff policy to keep women patients separated to minimise stress for staff, as women patients seem to copy each other's self-harm behaviour. The problem escalates when they are in a group”. The result was that this unit deliberately housed each of its four women patients on a separate ward. Two other mixed-gender units, one NHS and one private, hoped to open a single-gender women's unit in 2000.

Discussion

Any discussion of medium secure units must first acknowledge the current and historical problem in defining the term. The Home Office and Department of Mental Health and Social Security (1975) defined regional secure units in terms of the type of patients they should serve, and 20 years later medium secure units were defined by the length of care and treatment needed to alleviate the patients' condition (Special Hospitals Service Authority, 1995). It was unclear to the authors, and at times to the units involved in the survey, what criteria the units used to define them as medium secure. Eastman et al (Reference Eastman, Ghandi and Bellamy2001) are currently investigating low, medium and high secure units in terms of structural, functional and operational characteristics. In the interim, it would seem that the term ‘medium secure unit’ is a historical one that encompasses units and patients with different designations.

Concern about the distribution patterns of women in secure psychiatric units is well documented (Reference MadenMaden, 1996), with previous studies citing female/male ratios of 1:4 to 1:7 in medium secure units (Reference Higgo and ShettyHiggo & Shetty, 1991; Reference Milne, Barron and FraserMilne et al, 1995; Reference MurrayMurray, 1996). Our figures (342 women) suggest that there are four times as many women in medium secure units now as there were in 1995 (Special Hospitals Service Authority, 1995). However, due to inconsistencies in defining medium secure units, the authors are sceptical about the validity in comparing ‘real numbers’ of women; some of the increase may be due to the exodus of women from special hospitals. However, what is clearer is that women currently occupy 19% of the beds in medium secure units, which suggests a 1:5 female/male ratio consistent with that of the special hospitals (Reference Jameson, Butwell and TaylorJamieson et al, 2000). The lack of clear governmental reporting of the ‘real numbers’ and distribution of women in medium secure units has an impact on the management of these patients and the delegation of limited resources.

The relatively higher numbers of beds for women in private single-gender units and for men in NHS single-gender units present different implications. The comments obtained suggest that, as units become increasingly aware of the inadequate and often inappropriate provision of services for women in mixed-gender medium secure units, they are deciding not to admit women patients. This has inadvertently resulted in more single-gender beds for men in NHS units than for women. The NHS units have to rely on the private sector to provide beds in single-gender units for women, perhaps at the expense of effective continuity of care and rehabilitation. The absence of a local service can be detrimental to women's social networks, and women may be sent to higher secure facilities than is merited because there is no appropriate single-gender medium secure unit within their region. The struggle to find medium secure units able to provide specific and sensitive services for women is further complicated by a growing body of research (Department of Health, 2000) suggesting that a large proportion of women in medium secure units require a different type of security from that which is currently offered. This research recommends less emphasis on physical security; tall walls and fences, and more on relational security; staff facilitating women patients' containment; and reframing of their emotional distress. Whether the newly developed and proposed single-gender women's units address these issues is yet to be studied. The wider study in which the authors are involved over the next 2 years seeks to address some of these questions.

A final issue is the often-neglected small pockets of women with multiple vulnerabilities. These are the women who fall outside of the adult and average intelligence patient population located in predominantly male mixed-gender units. The higher risk of vulnerability for those women who are under 21 years or over 60 years or who have learning disabilities is still to be considered, and as we move towards redistributing adult women patients into single-gender units we must be careful not to neglect these ‘minority’ groups within the women's secure population.

Limitations of the study

The telephone survey was chosen as the least disruptive and most efficient method of collecting the data. The data may have some inconsistencies because it was up to our contact person's discretion to check the accuracy of the data that they provided. Also, the survey spans a 6-month period: there may be a few women patients who were either discharged or admitted during the course of the survey. However, because the average length of stay in a medium secure unit is 18-24 months, it is unlikely that there was much patient turnover.

The authors acknowledge the limitations in this form of collecting data but note that there are few data in this area. The future reporting of Department of Health, Home Office and institutional survey statistics by gender would be most useful.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all of the units that participated in the telephone survey and the High Security Psychiatric Services Commissioning Board for funding the study, of which this survey is a small part. They also extend thanks to Liz Mayne, Director of WISH, for her comments on a draft of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.