1. Introduction

This article contributes to understanding of Contemporary Art and of the temporality of contemporaneity, as well as to the philosophy of time more generally.Footnote 1 We talk of things or persons as contemporary when they share time ‘now’, in the past or future. ‘Contemporaneity’ usually implies the sharing of time during a shorter or longer extended period and only rarely a narrow sense of simultaneity as occurring at the same moment. I uncover insights into ‘contemporaneity’ as sharing time – along with the associated concepts of simultaneity and coexistence – in the Transcendental Aesthetic as well as in the Third Analogy. Examining the category of Contemporary Art will throw light on contemporaneity more generally, while discussions of Contemporary Art benefit from paying closer attention to its temporal character. The contemporaneity of Contemporary Art normally implies sharing time within ‘the present’ (however that may be defined). I show, however, that Contemporary Art is illuminated through the idea of an elective contemporaneity arising over a time-gap brought to light in artworks and suggested by Kant’s account of genius in the Critique of Judgment.

That Contemporary Art is a contestable category shows up in its relation to time. Minimally, it is ‘everything that is currently done’ (Naukkarinen Reference Naukkarinen2014).Footnote 2 Alternatively, its time-frame is merely a by-product of its paradigmatic status, identified through a series of categories radically distinguishing it from both modern and classical art (Heinich Reference Heinich2014: 38–40).Footnote 3

What is the connotation of ‘contemporary’ in ‘Contemporary Art’? The most obvious answers are:

-

(1) Occurring at the same time – i.e. sharing a chronologically defined time-frame understood as an extended present = Contemporary 1.

-

(2) Being ‘up to date’ or ‘where it’s at’ within a shared ‘now’ = Contemporary 2.

While the first definition is presupposed by the minimalist understanding of Contemporary Art as what is currently produced, the second reflects the view that it is defined by determining paradigms. In both senses contemporaneity implies temporality, but while the minimalist account is determined by chronology, the paradigmatic account diagnoses criteria currently prevalent.

A third sense of contemporaneity I propose is:

-

(3) Being contemporary in the sense of sharing time over a temporal gap = Contemporary 3.

This time relation, I will argue, is a form of recognition, no doubt influenced but not determined by current paradigmatic presuppositions.Footnote 4 Superimpositions of marks by the Chapman Brothers – contemporary artists not only in sense 1 but also in sense 2 – on prints from Goya’s The Disasters of War are, undoubtedly, transgressive, one of Heinich’s paradigmatic categories for Contemporary Art (2014: 98). They describe their The Disasters of Everyday Life (2017) as ‘rectification’ of Goya’s original works, thus intentionally ‘adding insult to injury’.Footnote 5 However, in the artwork do they not show recognition of something shared across time with Goya? Is it not plausible that they elected Goya as their contemporary in spirit, even while simultaneously differentiating their time (and their art) from his? Ignoring this complex relation results in the conclusion that they are merely artistically accredited vandals aiming to cause offence and brew up scandal. Perhaps, their artwork is subtler than their self-publicity, even though, for reasons associated with Contemporary 2, it would not be wise for them to admit as much!

Starting from Kant’s Transcendental Aesthetic, I examine his account of time as an undetermined framework presupposed in all empirical experience and establishing the precondition for simultaneity as a general form for instantaneous and extended sharing of time and, thus, for contemporaneity. I go on to argue that the Third Analogy’s account of coexistence as reciprocal causal following provides an ideal model of a stringent contemporaneity, whether in the past, present or future. In a new interpretation of a much disputed aspect of the Third Analogy, I show how reversibility among perceptions can be construed as a pre-cognitive intimation within experience of the transcendental principle of coexistence. The relevance of this for my discussion of Contemporary Art lies in the interdependence of transcendental and empirical levels of experience. I go on to argue that Kant’s account of genius, William Kentridge’s artistic deconstruction of time and his interactions with past artists, as well as what I call the ‘graphic respect’ for earlier art discoverable within superimpositions frequent in late Palaeolithic cave art, all – in interrelated but distinctive ways – bring to light an idea of ‘elective contemporaries’, i.e. Contemporary 3.Footnote 6

2. Kantian contemporaneity: simultaneity, coexistence and artistic following

Contemporary 1, 2 and 3 all imply sharing time, albeit in a variety of different ways. Is there a general structure of time that explains how contemporaneity as sharing time is possible? I examine Kant’s analysis of time in the Transcendental Aesthetic as a general temporal framework within which the determination of time as coexistence in the Third Analogy, as well as other less stringent forms of time-sharing, including over a time-gap by artistic geniuses, are possible modalities.

2.1 Time as framework for contemporaneity

For Kant time considered as a priori intuition is the presupposition of all temporal relations that arise (A30/B46, A32/B49).Footnote 7 According to this view time considered as an indeterminate but determinable and all-inclusive framework is the context for any sharing of time.Footnote 8 More specifically, time as framework is characterized by relations of both succession and simultaneity. I propose that simultaneity (zugleich sein) can, at this stage of Kant’s argument, only qualify as the most general possibility of occurring at the same time. This minimal condition of simultaneity may be determined either as ‘at the same moment’ or ‘within the same extended time’ – both of which qualify as contemporaneity.Footnote 9

Time and space conjointly operate as conditions for appearances (A34/B50). The Transcendental Aesthetic most obviously concerns temporal and spatial relations among ‘appearances’ understood as extra-mental objects knowable through the representations of a judging subject. However, everything (including artworks) entailing being affected through our senses qualifies as appearance. Appearances also include persons insofar as they are accessed through the senses. Within time we represent our selves ‘only as we are inwardly affected’ and thus ‘as appearance’ (B153, B68). In other words, we are aware of ourselves as sensory beings only within the medium of time as empirical inner sense. Our encounters with others insofar as we are sensibly affected by them must also operate at the level of appearances, with the proviso that while I affect myself through internal appearances, others affect me both in time and in space, that is, through externally appearing to me. For Kant, from a moral perspective we are capable of treating others as noumenal, i.e. as ‘ends in themselves’. Nonetheless, it is an implication of the Transcendental Aesthetic that our dealings with others cannot wholly escape the spatiotemporal world of appearances.

Time as pure form may seem to make possible succession, not simultaneity: ‘It has only one dimension: different times are not simultaneous (zugleich) but successive (nach einander) (just as different spaces are not successive, but simultaneous)’ (A31/B47). If time were exclusively successive it would be difficult to see how it could be a condition for the possibility of contemporaneity among things or persons. Moreover, time is the form of inner sense, i.e. of relations among representations in our inner state (A33/B49–50). How, then, could the temporal framework contribute to appearances (including other persons) qua outer, as would be required for Contemporary Art? Indeed, these two questions have important implications for Kant’s philosophy of time more generally.

Taking these two potential objections to my account in reverse order: first, how is it that time as the form of inner sense plays a role in outer appearances? The key is that appearances – unlike things in themselves – are accessible to the subject only through representations. Time is ‘the immediate condition of the inner intuition (of our souls), and thereby also the mediate condition of outer appearances’ (A34/B50–1). How does time’s status as the immediate form of inner appearances qualify it as the mediate form of outer appearances? Only space is the immediate form of outer appearances: ‘Time can no more be intuited externally than space can be intuited as something in us’ (A23/B37). Space, while the condition of external objects, is our subjective access to extra-mental things, i.e. ‘only the relation of an object to the subject’ is concerned (B67). However, space alone cannot achieve the representation of outer objects. Time, while only intuitable internally, is the mediate condition of outer appearances because it is a condition of the possibility of the representation of external objects.

Why is space not sufficient for the representation of outer things? Kant argues that time ‘grounds the way in which we place them in the mind as a formal condition’ (B67). Time ‘posits’ external things in the mind as representations through its role in taking up anything that affects us. Indeed, time is ‘nothing other than the way in which the mind is affected by its own activity, namely, this positing of its representation, thus the way it is affected through itself’ (B67–8). If representation of outer things is to be possible, the mind must not only be affected by something external: this affection must be taken up as a form of self-affection, i.e. as a representation.

We can construe the reliance of outer appearances on time in the following way. While appearances of external objects require space, without temporal representation I could not attend to something as an intentional object for me so that representation of it can come to consciousness.Footnote 10 Space secures the objective pole of intentionality as affection by something external, while time secures the subjective pole of intentionality through internalizing affection as a form of self-relation. Thus, to have an empirical representation of something or someone as an appearance requires both immediate (spatial) affection by the object and mediate (temporal) affection by the self.

Does Kant’s claim that time achieves ‘positing’ necessary for representation entail that time qua pure form already qualifies as consciousness? This would be too quick. Self-affection in time ‘precedes the consciousness’ of representations in experience (B67). Thus apperception requires but is not identical to ‘inner perception of the manifold’ (B68). Time as sensible form is the intermediary between immediate spatial affection in intuition and spontaneous determination by concepts of the understanding. The intriguing consequence is that apperception as spontaneous is in some respect dependent on self-affection which, for Kant, is passive or, more precisely, receptive (B153–4, see also A19/B33).Footnote 11

The claim in the Transcendental Aesthetic that time is the mediate condition of outer appearances is the complement to the Refutation of Idealism where it is argued that internal temporal relations can only be experienced in relation to outer objects (B274–9). All appearances of the senses stand in time relations (A34/B51). But the necessity of time does not remove the limitation that it is the merely mediate condition of external objects. Time requires space just as space requires time.

All three senses of ‘contemporaneity’ I have proposed for Contemporary Art require time as framework. Any relations between persons affecting one another at least in part through the senses – including through the intermediary of artworks – presuppose the general framework of time as the condition of possibility for representation. To consider another person as contemporary is to position (‘posit’) myself in relation to them within time. Positing requires that I represent the relation in which I stand to another in the sense that I take up them or their productions (acts or works) as appearances affecting me. Artworks are a species of relating to others through representations within the framework of time.Footnote 12

The second potential problem can be cleared up more quickly. On closer examination time as framework is the presupposition not only for succession but also for simultaneity among things, persons or artworks within the field of appearances: ‘only under its presupposition can one represent that several things exist at one and the same time (simultaneously) or in different times (successively)’ (A30/B46). There is no contradiction between this claim and A31/B47 linking time to succession. Different times must be successive within the all-encompassing whole of time and, consequently, the same thing can only occupy different states over successive times (B48–9). However, different things (or, as I have argued, different persons and their empirical interactions) may share the same time. Time is, thus, the formal condition for both succession and simultaneity. To qualify as ‘contemporary’, artworks need not occur at the same moment. They must, however, fulfil the minimal condition of a weaker sense of simultaneity, that is, of sharing time over an extended present or, alternatively, as I will argue, diachronically.

2.2 Coexistence and its pre-cognitive expression within experience: a stringent model for contemporaneity

Time is not only an indeterminate framework establishing the general possibility of both succession and simultaneity, the Analogies establish the possibility of determinations of time within that framework (B160). I propose that the Third Analogy, as the principle of coexistence, establishes a stringent standard for contemporaneity at the transcendental level qua simultaneous (though not necessarily instantaneous), reciprocal and causal ‘following’ (Folge) (B256–7). I also argue that this principle requires, as its empirical correlate, reversibility among perceptions of objects as an intimation within experience of their coexistence as substances. Coexistence applies only to ‘substances in appearance’, among which artworks do not figure (A213/B260). However, despite setting the bar much higher than would be appropriate for the designation of ‘Contemporary Art’, I further argue that through a via negativa minimal conditions of artistic contemporaneity come to light.

Kant asserts that ‘time itself’ (die Zeit selbst) cannot be perceived and thus we cannot derive from it that things follow each other reciprocally (B257, A215/B262). The bidirectional following characteristic of coexistence is identified as causal and, just as in his analysis of successive causal relations in the Second Analogy, Kant argues that knowledge of reciprocal interaction requires a category operating as a rule (B257). The category of community (Gemeinschaft) or reciprocity (Wechselwirkung) (B258) entails reciprocity between agent and patient (A80/B106). Determinations are established as reciprocal insofar as either element could be determining or determined – agent or patient – while, in fact, each determines the other bivalently at the same time.Footnote 13

Such reciprocal causal influence is a condition of objects of experience, i.e. as known. Coexistence is the condition of the possibility of things themselves – not things in themselves (Dinge an sich) but substantial appearances external to the mind (die Dinge selbst) (B258). Objective community among substances (commercium) is evident within experience in local and spatial community (communio spatii) as the ‘continuous influence (Einflüsse) in all places in space [that] can lead our sense from one object to another’ (A213/B260).Footnote 14 Without the capacity to make connections between substances qualifying as interactive, experience could never arise as a unified whole (A214/B261). This ‘thoroughgoing community of interaction’ (A213/B260) is, as Watkins (Reference Watkins1997: 436) argues, best understood as the weaker claim that such interaction is transitive, i.e. can be indirect.

An interpretative problem arises as to the construal of the relation between perceptions of empirical simultaneity and the principle of coexistence. Citing A211/B258 Strawson claims Kant answers the question as to how we know objects coexist ‘by invoking the reversibility or order-indifference of perceptions’, thus suggesting that (empirical) reversibility is the criterion for (transcendental) coexistence (Strawson Reference Strawson1989: 141). In fact, in this passage, Kant argues that cognition cannot be read off apprehension which is necessarily successive. Watkins (Reference Watkins1997: 419)Footnote 15 is thus surely right that reversibility among perceptions is not the criterion for, and is rather the consequence of, objective simultaneity among substances. And although Kant claims that the perception of one object as ground makes possible the perception of another, Guyer is correct to say this is misleading (A214/B261, Guyer Reference Guyer1987: 269).

Reversibility (empirical simultaneity) cannot be directly read off experience (Guyer Reference Guyer1987: 270). Nor, as we have seen, is the former the ground for coexistence. Nonetheless, Watkins remarks, without further explanation and as though nothing substantive were added, that reversibility plays the role of ‘clarification of our epistemic situation toward the objective coexistence of substances’ and that it is part of the meaning of coexistence thus must be included in a critical account of the latter (1997: 419). I propose a way to make sense of these various considerations, arguing that reversibility at the level of perception is a pre-cognitive intimation within experience of coexistence.

Kant’s introductory example in the second edition appears to offer an argument based on experiential grounds:

Thus I can direct my perception first to the moon and subsequently to the earth, or, conversely, first to the earth and then subsequently to the moon, and on this account, since (darum, weil) the perceptions of these objects can follow each other reciprocally, I say that they exist simultaneously. (B257)

The darum, weil clause could seem to make reversibility criterion not consequence, which, as Guyer and Watkins argue, is ruled out by the main direction of Kant’s argument. An alternative tack is to read the passage as implying the category is operative without entailing knowledge per se. This would preserve that reversibility cannot be grounded empirically, while leaving open that it can be epistemically relevant, not as ground but in revealing the empirical genesis of knowledge. Thus, like Molière’s aspirational bourgeois in The Bourgeois Gentleman who commissions a tutor to teach him to speak prose, our perceptions already stand in relation to a priori principles whether we are aware of this or not, otherwise our experience would be chaotic. However, this does not entail that all operations of categories within perceptions are already determining. If they were, all perception would qualify as knowledge. The latter conclusion may seem to be secured in the B Transcendental Deduction: ‘all synthesis, through which even perception itself becomes possible, stands under the categories’ (B161). However, arguably, there is a distinction between perceptions ‘standing under’ (stehen unter) – as opposed to their being determined by – the categories. According to my reading, perceptions always already stand in relation to the categories as their potentially determining form, but perceptions are not always already determined under the categories. Otherwise, Kant could not argue, apparently contrastively, that coexistence (which requires knowledge) is not to be found in apprehension. Admittedly, this can be read as the analytical and counterfactual claim that apprehension alone could not achieve knowledge without the introduction of a category. However, although the textual evidence is too complex to examine here, ruling out any distinction between perception and determinative judgement is surely too strong. I would argue that the categories are anticipated but not determining at the level of perception.Footnote 16

Seen in this way, even though perceptions operate successively, Kant’s example suggests we can find within them an intimation of simultaneity.Footnote 17 I can look at the moon and then the earth, gaining a sense of their coexistence, however I do not have knowledge of the latter until I employ the category of community in a determining judgement. This means that reversibility is not merely a consequence or ‘symptom’ (Guyer Reference Guyer1987: 271). Reversibility offers indirect experiential access to a principle that cannot be directly experienced any more than can time as framework: coexistence as transcendental condition requires an expression within experience. At the level of perception Kant’s presumptive conclusion (darum, weil) can only anticipate knowledge. However, if the category is exercised determinatively, perception will have been a first step to achieving knowledge.

How does coexistence as a stringent form of contemporaneity contribute to its empirical expression as contemporaneity? Whether reflected on or not, meaningful ascriptions of contemporaneity at the empirical level invoke some idea of sharing the same (extended) time, as well as possible (though often, in practice, failed) mutual interactions. Empirical contemporaneity thus relies – even if at a distance – on the transcendental idea of coexistence. Crucially, empirical contemporaneity’s debt to the Third Analogy is only viable because coexistence holds ‘throughout a common period of time’ and does not demand instantaneous co-presence (Allison Reference Allison2004: 261). The latter standard would set the bar too high for almost all claims to contemporaneity, even as an ideal criterion.

Following my claim that the Third Analogy provides an ideal standard for the temporality of contemporaneity in general, I now turn to its implications for Contemporary Art. The transcendental standard of reciprocal causal influence between substances is clearly far beyond anything it would be reasonable to expect of relations within contemporary art understood in accordance with any of the senses of ‘contemporaneity’ distinguished in the Introduction. In particular, requiring continuous influence among artists or artworks operating simultaneously and reciprocally such that Contemporary Art constitutes a whole would be nonsense. Nonetheless, in addition to the general requirement that any empirical contemporaneity requires some determination of sharing time and degree of interaction, it is reasonable to expect that if the designation ‘Contemporary Art’ is to have meaningful content it should capture significant patterns of partially continuous influence (some of which would be reciprocal), as well as some idea of what does (and does not) qualify for inclusion within a whole, understood regulatively. In this way, the stringent standard for coexistence operates as a via negativa throwing light on what may be implied in calling art ‘contemporary’, while Contemporary Art is a testing ground for the meaningfulness of the transcendental criterion at the level of experience.

In the next section I examine Kant’s account of a different model of following whereby influence is exercised non-causally yet, hypothetically, may be considered as reciprocal. Whereas coexistence is a sharing of time over ‘a diachronic relation between substances that exist throughout a common period of time’ (Allison Reference Allison2004: 261), this alternative form of following arises diachronically over a time-gap.

2.3 ‘Following’ as sharing time across a time-gap: elective contemporaneity

In the Critique of Judgment Kant introduces a non-causal model of influence closely linked lexically to the ‘following’ (Folge) of the Third Analogy. Drawing out the temporal implications of this specifically artistic form of influence will reveal how it contributes to the idea of Contemporary 3 and its peculiar sense of sharing time.

Following (Nachfolge) by reference to a precedent (Vorgang), rather than imitating, is the right term for any influence (Einfluß) that products of an exemplary author may have on others; and this means no more than drawing on the same sources from which the predecessor (Vorgänger) himself drew, and learning from him only how to go about doing so. (CPJ, 5: 283)Footnote 18

‘Following’ in this artistic sense entails taking as a precedent the works of a forerunner who leads by example rather than by rote.Footnote 19 Following requires that the follower turns to the same sources as his or her predecessor. But, as the learning is not imitating, it must be the case that the predecessor’s role is one of inspiration, or showing qualitatively how to respond to these sources, rather than dictating that such and such a procedure must be followed. The artistic outcome is influenced, but not causally determined, by the predecessor’s production.

It is only later that Kant relates this non-causal, non-imitative following to genius:

genius is the exemplary originality of a subject’s natural endowment in the free use of his cognitive powers. Accordingly, the product of a genius … is an example that is meant not to be imitated (Nachahmung), but to be followed (Nachfolge) by another genius. … The other genius, who follows the example, is aroused by it to a feeling of his own originality … (CPJ, 5: 318)Footnote 20

One genius follows another as a feeling of her own originality and thus is influenced by the other genius while remaining free, i.e. creatively independent. Even though such following avoids imitation, genius is nonetheless compatible with a certain sort of schooling as methodical instruction. (CPJ, 5: 318). We can understand this as implying that the follower develops self-discipline and self-formation not despite but in part through being inspired by the first genius. The new genius takes on the principles of the first genius as her own, thus avoiding both mere imitation and dilettantism, that is, being different just for the sake of it. Looking at this more broadly, this could suggest a view of education as providing constraints that are not causally determining.

It goes almost without saying that Nachfolge (following), Vorgang (precedent) and Vorgänger (predecessor) are temporal terms, expressing relations to a preceding someone or something. One artist follows another in objective time: they are successive to one another even though the gap may be short or protracted. However, developing the idea of Contemporary 3, the artist who follows in this non-causal sense chooses the followed artist as her elective contemporary in that she enters into a relation with one who came before and with whom she shares principles and sources despite not being in the same time. From the point of view of objective time the influence is one-sided, because it is impossible to escape the determination of time as successive from an epistemic perspective. However, the emerging genius can open up an alternative dimension of temporal relations as a reflective relation to the past, where influence is distinct from both successive and reciprocal causal determination. In this way, the works of the earlier artist are treated as if they were contemporary within a shared time and not determined by objective time relations. One example would be Picasso’s Las Meninas (After Velasquez) taking up his predecessor as an interlocutor. Whereas objective coexistence arises within the same extended time, in aesthetic following artists relate over a time-gap. Nonetheless they share an elective time within which, in principle, the direction of influence could have been (but objectively is not) reversed.Footnote 21

Earlier we saw that time as self-affection is a condition of the possibility of external appearances, including the appearances of others. Aesthetic following requires that one genius is influenced within the field of appearances by another genius through being inspired by their artworks. Aesthetic influence is not merely phenomenal, for the noumenal is expressed in the phenomenal appearance of a genius’s artwork.Footnote 22 Elective contemporaries influence one another non-causally within the modality of time on the border between noumena and phenomena.

3. Kentridge: animated time and elective contemporaries

William Kentridge is an artist working in Johannesburg. He is often described as one of the most important contemporary South African artists. He clearly qualifies as ‘contemporary’ in the first sense. It is also arguable that he qualifies in the second sense because he works across a number of media: principally drawing in conjunction with film, but also installation, opera, puppet shows, theatre and tapestry.Footnote 23 Nonetheless, as we will see, Kentridge’s work stands in a problematic relation with both these senses of contemporaneity.

3.1 The past and its exacting contemporaries

Despite the use of multi-media, there is something about Kentridge’s works that doesn’t sit easily with Contemporary 2. His work is ‘purposefully old-fashioned’ in a number of ways (McCrickard Reference McCrickard2012: 17). The very choice of drawing as his principal medium is out of kilter with the speed of modern life. Drawing, especially the way he does it, takes time. And while animation is a modern idiom, Kentridge refers to his method as ‘stone age’ (McCrickard Reference McCrickard2012: 17). He has remarked that presenting something ‘modern in appearance’ is ‘of little consequence’ for him, going on to say that this is not because he is nostalgic about the past, which is, he says, ‘exacting’ (McCrickard Reference McCrickard2012: 116).

Kentridge’s decision to relate to the past rather than to Contemporary Art owes much to political considerations.Footnote 24 His formation in the arts (not only painting, but also theatre) in the 1960s and 1970s coincided with the high point of conceptual and abstract art in Europe and the USA. Such art, to which he had only limited access, seemed to him detached and apolitical (Christov-Bargaviev Reference Christov-Bargaviev1999: 10–19). He suggests he didn’t quite ‘get’ the power of that art, although he is clearly more receptive to it now. His response was to turn back to earlier art, for instance, to the German inter-war artist Max Beckmann, who combined expressionism with political engagement. Beckmann’s way of doing art seemed relevant within the political context of apartheid South Africa. Kentridge also reached back further to Goya and, to a lesser extent, Hogarth. Such artists set ‘exacting’ standards for art within Kentridge’s present, in contrast to abstract art which – even, or especially, when it tried to be political – missed the mark.Footnote 25 Moreover, although Kentridge shares with earlier twentieth-century artists (such as Picasso) an interest in African art, he nonetheless cannot share their insouciant incorporation of another culture when he is aware of being in a historical situation where, he says, ‘the race card’ is always relevant.

Kentridge’s relation to past artists is not nostalgic because of his active receptivity to the standards set by them, both for their own period and for his own. This sense of the past as exacting for the present illuminates the relationship in which his works stand to Contemporary 3: a past artwork can open up a shared time through the challenges and insights it offers to the current way of seeing things. In the terms of the third Critique Kentridge ‘follows’ past artists, while in my terms they are his elective contemporaries. These past voices do not simply speak of their present from our past: they speak to and within our present even though coming from the past. In this uncanny sense, they are our contemporaries.

The relationship is no doubt somewhat one-sided because earlier artists do not know nor can they, chronologically speaking, enter into our present. However, despite – or even perhaps because of this – their works are capable of intervening in our present in ways that would not be possible for mere contemporaries, i.e. those who inhabit the same objective time-frame as us. This is where the time-gap characteristic of Contemporary 3 is productive: time difference makes possible a disjunctive contribution to a complex relation of recognition. Being too close up can result in mere contemporaries struggling to recognize features better accessible from a distance, whereas elective contemporaries have an advantage insofar as they exercise their influence across a time-gap.

3.2 The deconstruction of simultaneity

Reflecting on Kentridge’s multi-media work The Refusal of Time (Figure 1) opens up a further perspective on Contemporary 3. The notion of ‘refusal’ is not equivalent to a simple denial or annihilation of time, implying rather, I would suggest, putting in question and resisting while at the same time accepting the unavoidability of negotiating time. The verb ‘to refuse’ can be traced back to the Latin verb refundere meaning literally to cause to flow back or overflow and figuratively to give back, restore or return (Harper Reference Harper2021). Strikingly, often in Kentridge’s works, time is presented flowing backwards through the reversal of the direction of projection. Time is thus restored or given back to us in a different register through an experience of the reversal of the causal order of time. In this way and others, The Refusal does not merely illustrate practical or theoretical negotiations of time: the artwork makes the viewer a participant in an experimental questioning of time.Footnote 26

Figure 1. Still from William Kentridge, The Refusal of Time, 2012. © William Kentridge, courtesy of the artist’s studio.

The Refusal of Time – the book associated with the artwork – draws attention to the pivotal date of 1905 when Einstein announced the end of the ‘universal tick-tock’ of Newtonian singular absolute time in favour of multiple times (Kentridge Reference Kentridge2012: 159). For Kentridge this new scientific understanding of time converges with a subjective sense of time as operating at a different pace in different situations. From the perspective of Einstein’s ‘twin paradox’, the twin who stays on earth ages more quickly than the twin who voyages far into the cosmos before returning to earth. While neither objectivity nor subjectivity can escape time, The Refusal is an experiment in pushing back against determination by time through complicating and multiplying temporal layers in relation to one another, thus not so much denying time as restoring to it a deeper structure than that of clock-time.

In The Refusal a seminal event in the history of time is deconstructed. In 1894 the French anarchist Martial Bourdin planned to blow up the Greenwich observatory housing the meridian determining Greenwich mean time as the absolute (though conventional) marker of all times throughout the world.Footnote 27

The work is a five-channel projection of images leading up to the moment of the (intended) explosion, which Kentridge and his collaborator Galison compare to entering into a black hole (Kentridge Reference Kentridge2012: 164).Footnote 28 Each channel partially repeats but also is distinctive from the others. The immediate precursor to the explosion is portrayed in the five channels as five different situations:

-

(1) The clock room at Greenwich

-

(2) An observatory where watches are coordinated with celestial events

-

(3) The room where the anarchists built the bomb – transposed to modern-day Dakar, Senegal

-

(4) A large, inflated man who both maps the world and marks the Greenwich meridian

-

(5) A machine room which represents both the machine room of the Empire and the pumping station of a huge set of bellows that (only) supposedly keeps the inflated man pumped up (i.e. within the artwork). (Kentridge Reference Kentridge2012: 249)

The five channels are sometimes shown successively progressing round the room, sometimes simultaneously and sometimes disjunctively. The relations between images within any one channel, as well as the relations between different channels are all reflections on time relations, showing up the complexity of both succession and simultaneity within what is portrayed as well as in its artistic portrayal.

Most strikingly for the current discussion, the five situations detailed above qualify as contemporary insofar as each immediately precedes the ‘same’ explosion, thus, logically, should occur ‘at the same time’, yet they are not objectively contemporary. Their contemporaneity is elective and established only through the temporality of the artwork, which exhibits the possible disjunction within any simultaneity.

3.3 Contemporaneity as both intensification of time and recognition over time

Kentridge contributes to a deeper understanding of contemporaneity both by intensifying the experience of time and by enacting the experience of time as a form of recognition.

In his method of working with art from the past, as well as in the thematic content of his works, Kentridge combines being out-of-step as well as in-step with the present.Footnote 29 Contemporary 3 tolerates temporal continuities across gaps, and indeed flourishes in the interference patterns across times. The five channels of The Refusal of Time – repeating, converging and diverging – exhibit the absence of pure contemporaneity, while opening up alternative modes of contemporaneity. The work shows how being ‘in time’ with something or someone requires negotiation as an act of synchronization. In this way, our insight into contemporaneity is deepened through an intensification of temporal experience as multi-layered relations, in which simultaneities are both constructed and deconstructed.

To share time – whether in the present or across a gap – is a form of recognition, just as to deny sharing time is a rejection of recognition. Kentridge’s elective contemporaries are not selected by chance any more than their election is predetermined. Sharing time across a gap, even when not in fact reciprocal, may be as if reversible. If there were a time machine available, Goya could, I think, grasp what Kentridge is up to, even though Goya would not, we can only assume, understand the specificity of the context of Kentridge’s art. In this hypothetical time experiment, Goya would be likely to see things we – and perhaps also Kentridge – cannot see. Divergence in time can give rise to recognition because of and not despite a time-gap.

A parallel with the Kantian idea of Nachfolge shows up in Kentridge’s production of Shostakovitch’s opera The Nose, which is based on a story by Gogol, in turn inspired by Tristram Shandy looking back to Don Quixote (Kentridge Reference Kentridge2010). None of these artists simply copied what came before: but they did follow (in a Kantian sense) their forebears whom they adopted as collaborators within a shared time where interrelated artworks communicate with one another as elective contemporaries.

4. Cave art: graphic respect across a time-gap

Late Palaeolithic cave art could be considered to contribute to the idea of Contemporary 3 insofar as these paintings, engravings, bas-reliefs and, occasionally, sculptures speak to those who experience them now – experts and non-experts coming from many cultures, both adults and children. In this way cave art makes possible a sharing of time across millennia. Moreover, the experience of cave art can lead to an intensification of our own awareness of time through an encounter with unknown persons present only through their artworks. However, the persuasiveness of these claims rests on the acceptance of the possibility of such affects operating across millennia. Consequently, I will focus on a phenomenon of sharing time discoverable and available for examination in the material record of cave art.

4.1 Superimpositions over a time-gap

A phenomenon widespread throughout late Palaeolithic cave art is the practice of superimposing one figure or form on another. Superimpositions have been found across a wide range of caves ranging from Sulawesi in Indonesia approximately 40,000 years ago up until, for instance, Las Monedas in Cantabria, northern Spain around 12,000 years ago. It is thus safe to say that there was an extended tradition of superimpositions. While not always straightforward, it is often possible for archaeologists to establish the time-order of superimpositions. However, it is usually extremely difficult to establish accurate dating, as well as whether or not there was a time-gap and if so its extent.

Recent research has argued on the basis of chemical, superimposition and stylistic studies that superimpositions on the ‘Great Ceiling’ at Rouffignac (Dordogne, France) were carried out by a small group of artists in a short period of time (Gay et al. Reference Gay, Plassard, Müller and Reiche2020). This and other current research establish that some superimpositions were carried out within singular temporal episodes. Other cases where contemporaneity is likely include those where near-identical animals belonging to the same species are superimposed recessively, giving rise to a version of perspective. A striking example is the frieze of horses in the Hillaire Chamber North at Chauvet (Ardèche, France) dating from roughly 36,000 years ago, where multiple distinct profiles are combined in what appears to be a stylistically unified composition.Footnote 30 A compressed use of multiple lines shadowing the outlines of animals is often used in later cave art. This device has been interpreted as representing herds or implying movement (Azéma Reference Azéma2010: 421–36).

It is, nonetheless, probable that many superimpositions were added after a time-gap. This claim is indirectly supported by the fact that superimpositions are still widely used by archaeologists, alongside stylistic typology and more recent dating methods, to establish relative dating of time periods within cave art.Footnote 31 While it might be natural for an archaeologist to understand ‘chronology’ when she hears ‘superimposition’, my intent is to read this notion against the temporal grain, showing how it has relational or qualitative, as well as quantitative, significance.Footnote 32 While a broad range of superimpositions in cave art have, I believe, implications that are not simply chronological, only those made over a time-gap are significant for Contemporary 3.

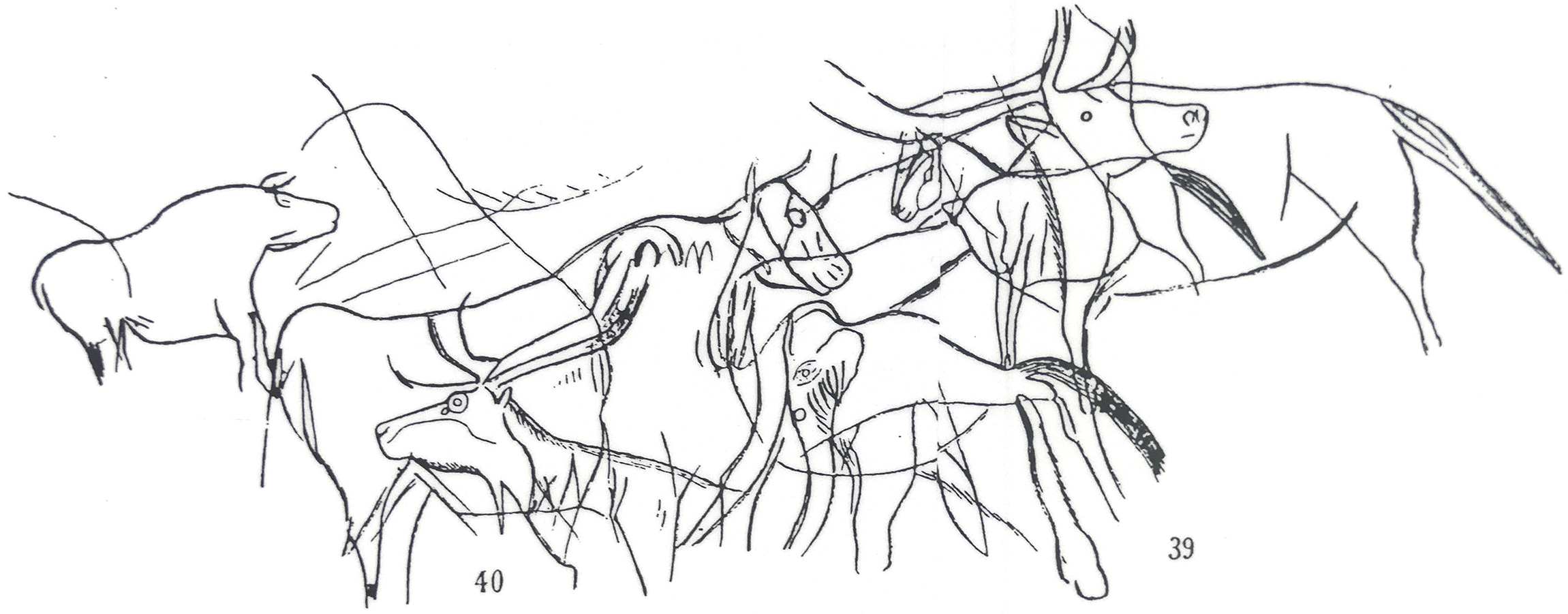

One hint of a time-gap discoverable in the phenomena themselves arises from the sheer density of superimpositions concentrated in some restricted spaces, for instance, the ‘Sanctuary’ at Les Trois Frères in the French Pyrenees and the ‘Apse’ at Lascaux in the Dordogne. The quantity of superimpositions makes it unlikely they were carried out within a single temporal episode. Combarelles (in the Dordogne) especially stands out for its intricate superimpositions extended over ninety metres. It seems likely that, in these cases at least, superimpositions were the result of a practice operating across time-gaps and carried out by successive groups of people.

Paul Bahn, a leading expert in late Palaeolithic cave art, sums up the overall phenomenon of superimpositions thus:

Theoretically, of course, all the layers could have been produced within a very short space of time – a superimposition could represent half an hour! – but it is perhaps more likely that they span a few years, at least, and the timespan could be decades, centuries, or even millennia. (Bahn and Vertut Reference Bahn and Vertut1997: 65)

In particular, Bahn argues that superimpositions at the important caves of Altamira, Marsoulas, Tito Bustillo and Lascaux are likely to have been constructed over extended periods of time.

4.2 Superimposition and graphic respect

Superimpositions that could have arisen over time-gaps include those where animal figures are placed on top of other figures from the same or different species, without the recession mentioned at Chauvet. A second relevant class arises where abstract marks are superimposed on animal figures. Such ‘signs’ are numerous in form, including, for instance, club-shaped ‘claviforms’, as well as shaded and subdivided rectangles called ‘shields’, but also series of lines. Both these classes of superimposition are frequent in late Palaeolithic cave art and it is likely that a significant proportion arose over a time-gap, as Bahn argues.

Strikingly, it is often the case that in such superimpositions the underlying figure is not simply cancelled out. Many superimpositions are of complete figures and, significantly for this discussion, the overlying figure is positioned so that the underlying figure in its integrity is, at least in principle, identifiable. While only those extremely familiar with a particular cave over many years – often guides – are able to ‘read’ a wide range of figures and their relations to the rock face, tracings – as well as more modern forms of recording – support the view that many superimposed figures overlap with one another so as to be still distinguishable, and thus, graphically speaking, are not simply indifferent to one another.Footnote 33 Nonetheless, not only the experts but also tracings and other methods capture only some of the plethora of superimpositions, especially when they are as dense as those at Combarelles (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Tracings by Abbé Breuil of superimposed animals at Combarelles, Dordogne. Courtesy of Centre des Monuments Nationaux, France.

While there are cases, such as at Les Trois Frères and Lascaux’s ‘Apse’ where it is tempting to describe superimpositions as ‘chaotic’, these are limit cases and, even then, we should not simply assume that figures stand in no relation to one another in such constellations. Returning to the more frequent somewhat less dense superimpositions, it is as though figures were meant to be seen together in the complexity of their relations or, when conditions suggest vision of underlying layers would have been restricted, as if the superimposing forms were constructed so as to leave the underlying figure intact whether it was seen or not. While it is impossible to prove this thesis definitively, if the superimpositions were simply indifferent to what went before, one would not expect palimpsests to be readable even to the extent they are.

There has been much debate about the significance of some abstract signs superimposed either within or across the outlines of animals. For instance, it has been argued that ‘barbed’ lines on bison in the Salon Noir at Niaux (in the French Pyrenees) denote arrows, with the further extrapolation that the image was intended as a symbolic contribution to successful outcomes in hunting. If marks on top of animals are interpreted as portraying weapons, the act of superimposition could qualify as a symbolic gesture of annihilation or cancelling. But even if this were true, the underlying animal figure is shown graphic respect in the delicacy and expressiveness with which it is portrayed. The figure is not simply scribbled out: its form is there in all its glory and integrity. Despite the compatibility of the ‘hunting scene’ interpretation with graphic respect for the figure of the animal, however, it is less evident that it is consistent with the time-gap required for Contemporary 3. While it is possible that the supposed weapons were added significantly later than the animals, it is more likely – under this reading – they would have belonged to the same artistic time-frame.

If, on the other hand, such marks are read as abstract rather than figurative – as current archaeology would have it – there is no necessity to conclude that they were produced simultaneously with the animal figures.Footnote 34 Certainly, they could have belonged to the same episode, for particular claims in favour of a time-gap are defeasible given the current state of dating techniques, nonetheless, not all such claims can be wrong for the reasons argued above. Moreover, such abstract signs – while looking like arrows to us – might have had any of a range of meanings, such as preserving, emphasizing or enhancing, as well as cancelling, or indeed some combination of these. They may have operated symbolically – perhaps as a form of graphic incantation – without any representational intention whatsoever. Indeed, the intention may have been to express something, even the structure of which is impossible for us to recognize. While ethnographic analogies can be instructive, it is not possible to definitively identify intentions motivating these marks.Footnote 35 However, if we restrict analysis to what remains in the material record, the superimposing animal or sign frequently preserves the integrity of the figure that was already there. This is the restrictive sense in which I claim there is evidence for ‘graphic respect’.

Another phenomenon in cave art is relevant to graphic respect across a time-gap, although it goes beyond my principal concern with superimpositions. This frequent trope arises either when later figures are left incomplete and do not interfere with figures already there, or, when earlier incomplete figures are accommodated by later figures. One example is a partial horse in the Hall of Bulls at Lascaux. This striking and carefully executed figure was left incomplete and then was complemented, indeed, ‘framed’ by a later monumental arrangement of two aurochs facing one another and accompanied by a number of little stags.Footnote 36

While there is good reason not to conclude that the purpose of the superimposing marks was simply to cancel, the complexity of superimpositions also suggests something more than simple preservation. A later figure adds to what was already there, transforming the previous layer within a complex graphic ensemble: the visual effect of the partial horse is transformed by the addition of the surrounding bulls. This material evidence shows that something earlier has both been graphically respected and, at the same time, augmented in its presentation. This is also true of forms superimposed on one another.

4.3 Superimpositions in cave art as a distinctive form of elective contemporaneity

The graphic respect displayed in cave art is a specific form of elective contemporaneity. It would surely be inappropriate to attribute Kant’s notion of originality from late eighteenth-century Europe to a culture – both inside and beyond Europe – commencing over 40,000 years ago. This is especially true, as late Palaeolithic art appears to have been relatively unmarked by innovation and diversity of style over a span of about 30,000 years. Where there was innovation it seems to have been very slow.

Nonetheless, we should not conclude that slowness in development of style entails they were only capable of ‘copying’ in Kant’s sense. It is highly unlikely that late Palaeolithic artists simply lacked the technical capacity to develop their repertoire, for instance, deploying figurative skills evidenced in depiction of animals so as to portray human figures other than schematically. They almost certainly had reasons for not doing so.Footnote 37 Prizing what we in the modern West call ‘originality’, if by this we mean prioritizing ‘the new’ over what went before, does not seem to show up as an aesthetic category in cave art, any more than it would be appropriate to assume it as defining in the analysis of classical oriental art.

Despite the dangers of imposing recent ideas of copying and originality onto the late Palaeolithic, it is not, I think, impossible to build some interpretative bridges. At the end of the last section I suggested that superimpositions were transformative while respecting something already there. This suggests a sharing of time that introduces additional layers of meaning (even though we cannot know the content of such meanings). While what was already there may have been experienced as part of their heritage – not only cultural but also natural (Descola Reference Descola2013) – it is striking that something already there and carried out by persons or forces unknown seems to have been considered an extension of their own activity. Rather than concluding that this implies a merely indifferent repetition of the same, arguably this suggests a heightened relation between what is other and what is one’s own, as well as between the present and the past. Transformations didn’t have to cancel the past, but nor did the past have to be seamlessly continuous with the present. This suggests a complex relation to time, where the past is re-enacted in the present and not merely copied.

5. Conclusion

I have argued that the Transcendental Aesthetic establishes the general possibility of contemporaneity. I have further argued that the Third Analogy provides an ideal principle for empirical contemporaneity necessary for the latter’s meaningfulness, while arguing that Contemporary Art is an expression of that principle at the empirical level. I have unearthed an alternative to synchronic contemporaneity discoverable in the third Critique, namely, diachronic contemporaneity over a time-gap, going on to argue that elective contemporaneity is exhibited in works by Kentridge and in cave art.

The implication of these insights for the category of Contemporary Art is that it is questionable whether the latter can be defined either by a specific time period or through a determining paradigm. If it is allowed that Contemporary Art is compatible with elective contemporaneity, not only are its temporal boundaries porous to the past, but neither its relations to the past nor its self-understanding in the present can be paradigmatically determined once and for all.

My position is not that Kant’s notion of following offers a theoretical explication of superimpositions in cave art nor of Kentridge’s multi-media art. Rather, all three converge in illuminating elective contemporaneity. Kant, Kentridge and cave art not only reveal Contemporary 3: willy-nilly they are elective contemporaries.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the following for invaluable help: Anne McIlleron and Natalie Dembo at William Kentridge’s studio; Monique Veyret and Marc Martinez at Combarelles; as well as the editors of this Special Issue of The Kantian Review for their insightful suggestions.