Introduction

In this article, I examine W. E. B. Du Bois’s global sociology by exploring his analysis of race and politics in Cuba. For Du Bois, the color line works to displace Black people from the human community. The Global color line points out how this condition is not limited to the United States but operates within colonialism and capitalism worldwide.

Beyond the prominence of works such as The Philadelphia Negro (1899), The Souls of Black Folk (1903), Black Reconstruction in America (1935), and Dusk of Dawn (1940) among his more than twenty-five books, speeches, and journalistic writings, the debate on the sociology of Du Bois has been crucial in returning to the discussion of racial segregation practices in the origins of sociology in the United States (McKnee Reference McKee1993; Morris Reference Morris2015; Rabaka Reference Rabaka2010).Footnote 1 Concepts such as double consciousness (membership in two different social worlds), color line (the division of people in racialized groups), and the veil (the manifestation of the color line in interpersonal relations) come from the work of Du Bois and are central to the development of theories of racial capitalism (Robinson Reference Robinson1983), the state of white supremacy (Jung Reference Jung2015a), and racialized modernity (Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020).Footnote 2, Footnote 3

I submit that Du Bois’s approach to Cuba is significant not only for confirming but also challenging the understanding of Du Bois’s global sociological project. In the 1930s and 1940s, while Du Bois was particularly interested in European colonialism in Africa, he also approached the racial situation in the Americas, particularly Brazil, Cuba, and Haiti. I refer to Du Bois’s connections with Cuban public intellectuals to explore how their analytical perspectives reinforce each other or establish differences within the socio-historical analysis of the global color line. Further, I state the contextualized difference of anti-racism in the criticism of national projects in Cuba and the United States from Du Bois’s writings in these decades. Finally, I show how the sources explored allow us to complexify the scope of Du Bois’s understanding of colonialism. I develop these points in five sections.

The first section sets the framework for discussing Du Bois’s sociology of the global color line. The literature on Du Bois as a global sociologist does not incorporate his writings on Latin America and the Caribbean. Therefore, this section addresses the relevance of Du Bois’s connection with Cuba in analyzing racism and colonialism in a global sociology that includes his encounter with the color line in Latin America. Further, in this section, I introduce how the narrative of Cuba as a raceless society preceded Du Bois’s vision of Cuba.

The second section refers to the methods used for this research. I chose to conduct documentary work in the U.S. and Cuba to discern “what kinds of archival evidence are amenable to historicized theorizing” (Lara-Millán et al., Reference Lara-Millán, Sargent and Kim2020, p. 346) and the construction of Du Bois’s global sociology. This article is based on the analysis of approximately six hundred primary documentary sources. The documents analyzed include 1) a selection of Du Bois’s correspondence referring to Cuba during the 1930s, especially with Cuban intellectuals; 2) Du Bois’s unpublished writings in which he refers to Cuba; 3) the analysis of Afro-Cuban or African American newspapers which debated racism in Cuba, and 4) Cuban magazines or periodicals in which the racial problem and the figure of Du Bois were discussed. I give special attention to the so far unexplored writings by Du Bois during his first visit to Cuba in 1941.Footnote 4

The third section explores the relationship between W. E. B. Du Bois and the Afro-Cuban journalist and public intellectual Gustavo Urrutia (1881-1958).Footnote 5 This relationship involved exchanging articles about racism in Cuba and the United States that both authors wrote and were interested in translating. This exchange took place especially between The Crisis magazine (United States) and Diario de la Marina (Cuba). While Du Bois maintained an interest in questioning the American imperialist project in Cuba, Urrutia established a comparative analysis of the configuration of racism in both Cuba and the United States. Unlike other Cuban authors of his time, Urrutia resorted to the case of the United States not to reinforce the image of Cuba as a raceless society but to explain the different paths that both countries took concerning the place of race in the national formation. Urrutia’s goal was not to refer to racism in the United States to reinforce the narrative of a raceless Cuba. Rather, he used the comparison to point to the reconfiguration of racial inequality. For his part, Du Bois used his knowledge of the Cuban independence process and its effects on the politics of the new republic to reinforce his critique of racism in the United States.

Du Bois’s connection with Urrutia allows us to see the points in which both authors refer to racism in the United States and Cuba to establish a global criticism. As we will see, even when Du Bois learned about Urrutia’s writings, Du Bois’s reading of Cuba does not go a long way toward an in-depth understanding of the racial conflict on the island. To a large extent, Du Bois shared the prevailing vision of Cuba as a society free from racism. However, his approach to Cuba was fundamental in two senses. First, it led him to consider the contradictions between cultural integration and social and economic equality in a setting other than the United States. Second, Du Bois developed the fundamental place assigned to the critique of U.S. imperialism within global sociology.

The fourth section refers to the confluences between Du Bois, Gustavo Urrutia, and Alberto Arredondo from the collective Adelante regarding the debate on race and nation. Du Bois’s advocacy for Black autonomy was one of the main points of debate when he left the National Association for the Advancement of the Colored People (NAACP) and resigned as the editor of The Crisis in 1934. In Cuba, Black collectives rejected any sort of Black nationalism. The idea of Black nationalism in Cuba was considered opposed to José Martí’s republican ideal and contradicted the Afro-Cuban political struggle for an integrated nationalism. Notwithstanding, I read how Du Bois framed his position about “a Negro nation within a nation” within a radical democracy and social justice project, similar to what Urrutia defended in the newspaper Adelante. The relevant point is that the discussion around race and nation allows deepening the questioning of a democracy that coexists in complicity with racial inequality.

The focus on Cuba is not neutral since the country played a unique role in the anti-racist struggle contributing to the construction of republicanism in the Caribbean. The foundational idea of the Cuban Republic as anti-racist and anti-colonial constituted the basis for political discourses on a raceless nation. Cuban rebellions integrated multiracial armies at all ranks and had outstanding anti-racism rhetoric. Often used as a synthesis of the Cuban raceless republican ideal is Martí’s sentence in his independentist speech in 1863: “There is no danger of war between the races in Cuba. Man means more than white man, mulatto, or black man. Cuban means more than white man, mulatto, or black man.” (Martí Reference Martí1968, p. 310).

Du Bois visited Cuba for the first time on June 5th, 1941.Footnote 6 The fifth section is based on the ethnographic notes Du Bois took during the ten days of this visit with sociologist Irene Diggs. Du Bois and Diggs toured several parts of the country and held meetings with various cultural circles. Du Bois’s ethnographic notes on Cuba reveal his approach to the racial relations outside the United States. Certainly, Du Bois was uncritical of the dominant ideology of the raceless nation, and some of his pieces are merely celebratory of cultural integration. However, his writings based on his experience in Cuba contributed to expanding the analysis of the global color line from an anti-imperialist approach. Cuba was significant for Du Bois’s perception of social and economic inequality as the basis of racial discrimination and how American neo-colonialism endured economic inequality.

In the conclusion, I reflect on how Du Bois’s connection with Cuba presents challenges for a Du Boisian sociology since Du Bois’s sociological principles did not always manifest in his understanding of particular situations.

Du Bois’s Global Sociology and the Analysis of Cuba

Going against and beyond other sociologists of his time, Du Bois worked on a sociology of the global color line. As José Itzigsohn and Karida Brown (Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020) argue, Du Bois’s books Color and Democracy (Reference Du Bois1945) and The World and Africa (Reference Du Bois1947) signified, on a theoretical level, the analysis of the global character of the color line, and how forms of neocolonialism would perpetuate global inequalities.

Research in the fields of history and political theory refers to Du Bois’s analysis of the global color line from his biographical, intellectual, and political engagement with Europe and Asia. Du Bois’s writings about Russia, China, Japan, and India have been analyzed by Bill Mullen (Reference Mullen2015). Michael Rothberg (Reference Rothberg2009) examined Du Bois’s visit to Warsaw in 1949, and Brandon R. Byrd (Reference Byrd2020) analyzed Du Bois’s stand against U.S. occupation in Haiti. Nahum D. Chandler (Reference Chandler2021) and the articles integrated within Phillip L. Sinitiere (Reference Sinitiere2019) refer to Du Bois’s global history of race. While this set of works contributes significantly to understanding Du Bois’s analysis of the global color line, none of them refers to Latin America or the Hispanic Caribbean.

Du Bois wrote about Latin America and the Hispanic Caribbean, but his writings about this region have not been analyzed in depth. Exceptions are Juliet Hooker’s (Reference Hooker2017) and Juliana Góes’s (Reference Góes2022) analyses of Du Bois’s writings on Brazil. Hooker reviews Du Bois in the light of what she calls ‘mulatto fictions,’ a form of speculative mestizo futurism, arguing Du Bois implied a notion of mestizaje that questioned the binary model of eugenic racism of his time while raising an alternative to the racial problems of the United States (Hooker Reference Hooker2017). Góes (Reference Góes2022) points out how Du Bois framed Brazil as a racial paradise to promote different racial politics in his country. Du Bois contributed to disseminating the myth of Brazil’s racial harmony created by white intellectual elites in order to challenge anti-miscegenation discourses and biological conceptions of race.Footnote 7

The scholarship of Du Bois as a sociologist of the global brings to the core of the discipline his scholarship on African history and his political Pan-Africanism (Winant Reference Winant2017). Critical sociology of race (King Reference King2019), global historical sociology (Magubane Reference Magubane, Go and Lawson2017), and sociology of the racial state and white supremacy (Jung Reference Jung2015b) have drawn attention to how, in sociology, the aphorism “the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line” is frequently quoted without including the second instance of this quote which precisely describes the global character of the color line: “the relation of the darker to the lighter races of men in Asia and Africa, in America and the islands of the sea” (Du Bois [1903] Reference Du Bois2018, p. 13). Du Bois made sense of the color line “in [the] America[s] and the islands of the sea” from his connection with intellectuals on the island and his writings during his visit to Cuba. Both experiences developed amid anti-racist struggles for democracy on the island.

The global dimensions of Du Bois’s sociology are present from the beginning of his intellectual work. Du Bois’s 1896 dissertation “The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870” was significant in addressing how the global scope of the anti-slavery and anti-colonial revolution on the island of Saint Domingue, which allowed the formation of the Republic of Haiti in 1804, was crucial in the reconfiguration of capitalism as a global system (Du Bois [1896] Reference Du Bois2007). More significantly, Du Bois connected to how the United States was impacted and reconfigured its economic and political structure due to the Haitian revolution (Magubane Reference Magubane, Go and Lawson2017). Furthermore, analyzing Du Bois’s articles ‘Sociology Hesitant,’ (Reference Du Bois1905) ‘The Color line belts the World’ (Reference Du Bois and Lewis1906), and ‘On Our Spiritual Strivings’ (1903, first chapter in Souls of Black Folk), Zine Magubane states that “[a] Du Boisian approach to global historical sociology explores how processes of racial formation become the staging ground whereupon the interactions that produce the ‘national’ and the ‘international’ as seemingly separate realms occur” (Reference Magubane, Go and Lawson2017, p. 102).

Du Bois’s perspective on Cuba shows that the analysis of racism and colonialism during the 1930s and 1940s took place within national and international dialogs and interactions. In this regard, this article contributes to the construction of a contemporary Du Boisian Sociology since “[m]ethodologically, a contemporary Du Boisian global sociology should be guided by a theoretical understanding of racial and colonial capitalism, rooted in historical analysis” (Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020, p. 95). For Itzigsohn and Brown, ‘Du Boisian Sociology’ refers to “a sociological approach, a mode of inquiry, and a disposition toward the aims and practice of knowledge production” (Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020, p. 192). However, a Du Boisian sociology is also “an aspirational and collective endeavor” far from establishing any “Du Boisian orthodoxy” (Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020, p. 185).

In this collective undertaking, Du Bois’s sociology can be read both as a critique of the imperial standpoint (Go Reference Go2016), as an expression of ‘decolonial sociology’ (Weiner Reference Weiner2018), or as ‘connected sociology’ (Bhambra Reference Bhambra2014). Julian Go (Reference Go2016) states that both Du Bois and Frantz Fanon, based on the experience of French colonialism (Fanon), as well as that of racism in the United States Empire (Du Bois), adopted a ‘subaltern standpoint’ that allowed them to produce new knowledge, questioning the “metropolitan-imperial standpoint” (Go Reference Go2016, p. 167). In Du Bois’s historical context, the metropolitan standpoint consisted of functionalist approaches and social evolutionism. Questioning the imperial standpoint implied producing “new knowledge” starting “from the ground up,” evading the analytic categories constructed from the “Northern-metropolitan standpoint” (Go Reference Go2016, p. 23). For Melissa Weiner (Reference Weiner2018), Du Bois embodies the source for decolonial sociology that, unlike regions of the Global South, had not been sufficiently developed in the United States. For Gurminder Bhambra, Du Bois’s work, together with Fanon, works “to build up alternative histories and to establish connections across what has previously been presented as separate” (Reference Bhambra2014, p. 146).

Bhambra’s perspective allows framing the analysis of the connections between Du Bois and Cuban intellectuals and politicians within the exploration of alternative histories of the formation of the global sociology of race and colonialism. Rather than analyzing how Du Bois, by himself, adopted a subaltern standpoint (Go Reference Go2016) or how his sociology could be a precursor of decoloniality (Weiner Reference Weiner2018), I trace Du Bois’s approach to the formation of the global color line from his experience of encountering the history of Latin America and the Caribbean, particularly Cuba, and the experience of specific subjects who were his contemporaries. These are encounters crossed by the production of knowledge and the will to understand racism between the two nations. I also explore how some of Du Bois’ ideas resonated or not with some of the criticisms of the mechanisms of color line reinforcement in Cuba.

In “The Color Line Belts the World” (Reference Du Bois and Lewis1906), Du Bois stated that “the Negro problem in America is not but a local phase of a world problem.” Exploring the “global Du Bois” avoids presuming that the object of analysis is always nations or states and takes us to the study of the connections, understandings, interchanges, and mutual recreations among the African Diaspora, in this case, between the United States and Cuba. Thus, the histories of Afro-Cubans could challenge the nationalist approach or the imperial standpoint from which sociology refers to Latin America, the Caribbean, and the Global South in general. The analysis of the global color line means to get to the “epistemological, methodological, theoretical centrality of globally embedded and transnationally connected processes of boundary construction” (Magubane Reference Magubane, Go and Lawson2017, p. 105). In his analysis of Cuba, Du Bois emphasizes how producing racial boundaries was at the core of American interventionism and capitalist project.

Du Bois’s perception of Cuba was significant for his global sociology of race since Cuba had a critical role in the construction of the U.S. Imperial State. Together with Puerto Rico, Hawaii, the Philippines, Guam, Samoa, the Virgin Islands, the Panama Canal Zone, Cuba became part of the American Empire in the early Twentieth Century. Though not a formal colony, Cuba was occupied by the United States for the three years succeeding the War of Independence from Spain (1895–1898). Three rebellions lead to Cuban independence: The Ten Years War (1868–1878), the Guerra Chiquita (1879–1880), and the War of Independence. The United States fed its worldwide hegemony aspirations by controlling the Cuban constitution through the Platt Amendment.Footnote 8 Indeed, throughout the first half of the Twentieth Century, the United States actively pursued extending Jim Crow racist principles to the island.Footnote 9

However, Afro-Cubans reappropriated the nation’s foundational myth based on racial democracy as a political instrument to legitimize their participation and inclusion in society. While white elites manipulated José Martí’s discourse to accuse Afro-Cubans of being “racist” when they demanded racial equality, Afro-Cubans “presented Martí’s racially fraternal republic as a goal to be fulfilled, rather than an achievement” (de La Fuente Reference de la Fuente1999, p. 52). This appropriation allowed Afro-Cubans to demand equality in social, political, and economic life. In particular, Afro-Cubans challenged the narrative that Black freedom was a product of white generosity, emphasized the republic as a product of their creation, and insisted that the racially equal Nation should become a reality.

Notwithstanding, this political strategy does not mean that, effectively, Afro-Cubans achieved the historical production of a racially fraternal society, but it does mean that the narrative about race and nation was in dispute since the early Republic. In fact, in the 1901 Constituent Assembly, Afro-Cubans’ participation was crucial to defeating the United States’ interest in denying universal suffrage to the illiterate (and consequently excluding the majority of Black people). With the right to vote, Afro-Cubans gained an important influence in the country’s political life in the following decades, even though racist discourses, especially against Black political organizations, were not extinguished.

The manipulation of Martí’s rhetoric in the Cuban elites’ hands served to continue racial inequality. Nevertheless, Afro-Cubans continued to dispute what the Nation should mean in the following decades and made it a central issue in the political processes that led to the 1940 constitution (Guanche Reference Guanche2017). At the same time, African Americans’ participation in the 1898 war, and independent Cuban ideals of racelessness, impacted race relations within the United States.Footnote 10 In this regard, the Du Bois-Cuba relationships during the 1930s and early 1940s are preceded by a not infrequent African American vision of Cuba as a territory relieved of anti-Black racism. However, as we shall see, the use of archival material and unpublished sources advances the understanding of Du Bois’s thinking in a way that would not be possible if only published sources were used.

Methods

Du Boisian sociology has been associated with a critical social theory of racial oppression, exploitation, and violence (Rabaka Reference Rabaka and Meyns2021), as well as with the intersectional analysis of race, class, and gender (Hughey Reference Hughey and Romero2023). Itzigsohn and Brown (Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020) propose that Du Boisian sociology implies four analytical dimensions: examining the historical and contemporary forms of racial and colonial dispossession and exploitation; searching for the links between global structures and the phenomenology of lived experience; analyzing the historical and contemporary forms of the intersection of race, class, and gender; and the study of the historical and present forms of the racial state. The analysis of the relationship of Du Bois with Cuba focuses on the first and second dimensions indicated by Itzigsohn and Brown. It also traces the other dimensions since such analysis unravels how concrete manifestations of racial and colonial capitalism were read in different places in the Americas. These manifestations result from the political and economic interconnection between two territories, Cuba and the United States.

My method of documentary analysis included three phases. First, I traced and sampled the existing and available documents in the Du Bois Papers Special Collection at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst to determine their volume and importance. I then compiled and classified the documents in which Du Bois referred to Latin America, the Caribbean, and Cuba in particular.Footnote 11 My selection of primary sources was done according to their relevance to key categories in the sociology of race and racism, historical sociology, global sociology, sociology, and the sociology of W. E. B. Du Bois. Broad code categories were Color Line, Colonialism, U.S. Imperialism, Racism, and White Supremacy.

Second, I worked on data collection at the newspaper library of the José Martí National Library in Havana. In addition to these sources, I conducted semi-structured interviews with six Cuban scholars working on Black History. Some of these historians gave me access to their personal documentary archives. I worked with these interviews and secondary literature for the socio-historical contextualization of my primary sources and data analysis. I then determined the value of the primary sources by discerning those that would serve as support for the contextualization of data from those of analytical value. On the one hand, I selected correspondence insofar as it allows understanding how the actors involved in knowledge production processes understood the relationships and conditions that made such undertakings possible. On the other hand, I considered sources of analytical value those that allowed me to broaden the discussion established concerning a particular period or the debate on the racial question.

Finally, I conducted a comparative reading of the documents from the perspective of the preliminary findings. I related certain documents with others by the same author or other authors to interpret the racial dynamics articulating the production process of the critique of race and racism between Cuba and the United States. The second step consisted of relating the sources to the context of their production or the networks in which they circulated. This allowed me to develop the articulation of political meanings and relevant theoretical debates within the formation of the global sociology of race. I considered primary sources to have different intentions. On the one hand, published research has the explicit intentionality of contributing to developing knowledge on the racial question in the United States, Latin America, and Cuba in particular. On the other hand, I assumed that journalistic writings (in magazines or newspapers), as analyses of social life, have the implicit intention of supporting research processes and, therefore, knowledge construction. I identified primary sources to be included as textual citations that strengthen my analysis in each section. In the analysis, I seek to make explicit “how a researcher [i.e., myself] ‘sees through’ particular historical documents and develops an understanding of the historical context” (Lara-Millán et al., Reference Lara-Millán, Sargent and Kim2020, p. 348). My interpretive analysis consists of transcending the immediate intelligibility of the sources, unveiling aspects that are not directly intuitive but present in these sources.

The Anti-Racism of W. E. B. Du Bois and Gustavo Urrutia in Cuba and the United States

This section refers to the connections between Du Bois and Gustavo Urrutia and their analysis of racism. While Du Bois was an African American sociologist, Gustavo Urrutia was an Afro-Cuban architect and accountant who practiced journalism since 1928. For both, racism in Cuba and the United States could be read, despite differences, as a manifestation of structural order.

In December 1930, Mary McLeod Bethune, founder and former president of the National Association of Colored Women and president of the Bethune-Cookman College, wrote an open letter to Gustavo Urrutia, describing the racial discrimination she suffered at the hands of Port authorities upon her arrival in Cuba. Bethune was denied entry to the country and was only admitted after contacting the American embassy. In her letter, published in the magazine The Crisis (Vol. 17, No. 2), Bethune stated a clear case of racial discrimination:

My dear Mr. Urrutia:

With the fine setting of your beautiful city and the wonderful spirit of the Cuban people, I am at a complete loss to understand the discrimination and unjust treatment that was given to me on my arrival in Havana recently, by the immigration officers.

The members of my party and I attempted to purchase round-trip tickets from Miami to Havana, and were refused on the grounds that they were not sold to Negroes. When we asked the reason for this we were told that these were the instructions given to the officials because of a desire to discourage Negroes from going into Havana. (Bethune Reference Bethune1930, p. 412).

Urrutia wrote to The Crisis a response on the situation described by educator and civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune with the title “Negro Tourist in Cuba.”Footnote 12 W. E. B. Du Bois was the acting Editor of The Crisis since 1910 as director of publications and research for the NAACP.

As historian Frank Guridy (Reference Guridy2010) describes, the development of “Black tourism” between the United States and Cuba was fundamental when building the Afro-diasporic ties between these two countries. Though African Americans saw trips to Cuba as “a way to avoid the humiliation of racial segregation,” traveling to Cuba actually resulted in dealing with the global operation of the color line and exposing themselves, in a random sense, to harassment partly influenced by the predominance of white tourism to Cuba (Guridy Reference Guridy2010, p. 153).

Bethune wrote to Urrutia since he was the editor of the newspaper page Ideales de una raza and author of the opinion column “Armonías” in the newspaper Diario de La Marina. From 1928 to 1931, Urrutia covered current events by analyzing racism, colonialism, and inequality in Cuba. The historian and NAACP organizer William Pickens talked to Du Bois about Urrutia’s interest in a public reply to Bethune’s letter. Pickens wrote to Du Bois, stating: “I am simply telling you who Urrutia is: he is a Negro man who has charge of a section of the biggest paper in Cuba […] his material could be well edited and used by The Crisis. He is sane and aggressive.”Footnote 13

When Pickens referred to Urrutia as “aggressive,” Urrutia was writing in the “biggest paper in Cuba” Diario de la Marina, attacking the dictatorship of General Gerardo Machado. Machado was elected president for the 1925–1929 period; however, he extended his mandate for six years (1929–1935) through an illegal reform of the constitution in 1928.

Machado’s regime coexisted in a close relationship with American power and the Cuban bourgeoisie. His high level of repression was aimed to prevent activist social organizations and protests amid the adverse economic scenario in the late 1920s Cuba. The dictatorship then looked “to guarantee the profit rate and the imperialist exaction” (Martínez Heredia Reference Martínez Heredia2009, p. 163). In early 1927, “some 150 labor leaders and workers had been killed” (Pérez Reference Pérez2008, p. 179). Machado’s violence led moderate opposition factions to request the North American government’s intervention through the U.S. embassy in Havana. For instance, in 1927, the prominent intellectual Fernando Ortiz appealed to the “moral obligation” of the United States government to end the crisis. In 1929 leaders of the Nationalist Union, such as Octavio Siegle and Cosme de la Torrente, made similar appeals to the United States government. Indeed, the non-intervention of the United States was interpreted, by the moderate opposition, as the American government’s support for Machado (Pérez Reference Pérez2008, pp. 184-185).

Although the most critical articles detailing Machado’s economic and political management, as well as the coverage of student protests, were in Bohemia magazine, as well as Carteles, and the weekly newspapers Karikato and La Semana, other publications, such as the Diario de la Marina, were not exempt from the illegal supervision of journalistic writings that the Machado government implemented in the second half of 1930.

This process, known as prior censorship, generated a confrontation between Machado and the Cuban press.Footnote 14 The previous censorship was suspended during October 1930 within the atmosphere generated by the upcoming elections in November. However, the press accused the government of electoral fraud, and to that end, the previous censorship was reinstated on November 12th, causing the leading newspapers to stop publishing. The Diario de la Marina was closed in December. The Italian citizen Aldo Baroni, technical director of Diario de la Marina, was arrested and expelled from the country (Lima Sarmiento Reference Lima Sarmiento2014).

Many have pointed out how Urrutia’s Ideales de una raza was the outstanding public forum for the debate about race in Cuba between 1928 and 1931 (Cubas Reference Du Bois2018, Fernández Robaina Reference Fernández Robaina2007, Schwartz Reference Schwartz, Brock and Fuertes1998). Here it is most relevant that “Urrutia’s page was a space where Afro-Cuban intellectuals articulated their understanding of their relationship to the broader African Diaspora” (Guridy Reference Guridy2010, p. 122). Ideales de una raza translated articles from the African American journals Chicago Defender, Pittsburg Courier, and Opportunity.

The article “Negro Tourists in Cuba” that Urrutia sent to The Crisis in December 1930 occurs amid the convulsion unleashed at that time between the Machado dictatorship and multiple social actors. However, Bethune’s letter and Urrutia’s reply to The Crisis were also published in Ideales de una raza. Footnote 15 Langston Hughes translated Urrutia’s response to The Crisis. The Cuban journalist raised the situation experienced by Bethune, not only as an example of how racism manifests the tensions around borders but also the effects racial discrimination in the United States has on Cuba.

In those years, the anti-mobility discourse in the United States pursued restraint on the right of African Americans to travel North within the country to “protect” white workers’ jobs. Thus, Urrutia’s response demonstrated how aware he was of the intersection between racism and anti-mobility sentiment in the U.S. and how such intersection was inscribed in a matrix of inequality: denying Black people of the South the right to mobility that Americans had.

In his piece, Urrutia affirmed that if anyone should be ashamed of such discriminatory treatment in Cuba, it should not be Bethune (who claimed that she would not allow any authority or government to shame her) but Cuba. For Urrutia, even with the rhetoric of racial equality managed by elites, their rulers were unable to discard ideas like those prevailing in the United States. His response was also published in Diario de la Marina and was part of Urrutia’s strategy in using the analysis of racism in the United States to confront a raceless nation’s discourse in Cuba.

Both The Crisis and Ideales de una Raza, responded to the desire to analyze the racial question within the political and cultural field in the frame of the African American and Afro-Cuban connection. During the 1930s, anti-racist groups in Cuba strategically used racial discrimination cases toward African American tourists to combat the elite’s usage of the myth of a raceless Cuba.Footnote 16 As Bethune’s case was not isolated, activists from the political-cultural field like Urrutia would insistently question the denial of racism in Cuban society.Footnote 17 Although racial discrimination against tourists especially mobilized Afro-Cuban intellectual elites, this visibility in high-circulation newspapers, such as Diario de La Marina, was crucial for pointing out the racial issue within the Machado regime’s political mismanagement.

In the United States, Du Bois received Urrutia’s writings within the first two weeks of December 1930.Footnote 18 It was in this same environment that Du Bois declared at the request of William English Walling, a founding member of the NAACP, that he was “[…] deeply sympathetic with the idea of our going on record concerning Cuba,” and he added, “I am venturing to enclose a tentative statement.”Footnote 19 The letters between Walling and Du Bois reveal how they discussed world politics within the NAACP. Knowing this, Walling asked Du Bois to revise his original writing on Cuba and make it stronger.Footnote 20 Hence, in late December, Du Bois wrote the NAACP final resolution:

AND WHEREAS, Cuba is struggling today against domestic tyranny and foreign intervention by the United States.

AND WHEREAS, because of treaty relations, the attitude of our State Department, and the great power of American financial interests, the people of the United States are especially responsible for Cuban conditions.

AND WHEREAS, the effect of interference into the domestic affairs of Latin American by this country has in practically every case operated against the interests of the colored people of those countries.

AND WHEREAS, at least one-third of the population of Cuba is colored, numbering more than a million people, with complete political and civil equality with the whites, enjoying every privilege and suffering from every oppression, as is evidenced by the eminence of Maceo, Gomez, and others.

RESOLVED THAT the Board of Directors of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People protests against any interference of any kind on the part of the United States in the domestic affairs of Cuba and extends its deep sympathy to the Cuban people regardless of race in their struggle for free popular government, uncoerced by domestic tyranny or foreign intervention.Footnote 21

Previously, in May 1930, Du Bois had signed “a protest against terrorism in Cuba”Footnote 22 and joined the American activist Roger Baldwin and the International Committee for Political Prisoners in a statement against Machado’s “repression of all oppositions […and] denial of freedom of press, meeting and propaganda,” emphasizing that “[w]hile we oppose interference, force of public opinion will be directed against present measures and in support of opposition pledged to a democratic regime.”Footnote 23 Clearly, the statement written on behalf of the NAACP in December 1930 reaffirms these stands.

Du Bois’s account incorporates anti-imperialist and anti-racist criticism. The starting point for analyzing Cuba’s situation is to make evident the neo-colonial power that capital and the United States have over the island. Therefore, it is not a neutral statement: what is happening in Cuba is an entrance to the question of how the empire expands power against the interests of people of color in Latin America. Both American imperialism and the oppression of the Cuban people are rejected because they are “against the interests of the colored people of those [Latin American] countries.” Concurrently, the rejection implies a demand for respect of “Cuban people regardless of race in their struggle for free popular government, uncoerced by domestic tyranny or foreign intervention.”

However, the words of Du Bois himself on the political and racial question in Cuba seem to reveal a paradox. On the one hand, Du Bois insists on questioning U.S. interventionism and condemns political persecution and repression of popular demonstrations. On the other hand, he seems not to integrate his knowledge of the race relations situation that he acquired through Bethune, Pickens, and Urrutia. Being a statement on behalf of the NAACP, Du Bois framed the statement to echo the African American community’s shared vision of Cuba: a country where colored people live “with complete political and civil equality within the whites, enjoying every privilege.”

Certainly, Du Bois denounces the domestic tyranny and the structural conditions that the United States seeks to impose on Cuba.Footnote 24 These conditions are not only to impede the economic functioning but also to restrict the exercise of the rights that the Black Cubans have. In Du Bois’s view, such rights are exalted at the national level in the figure of leaders who fought for Cuban independence and racial equality, like Antonio Maceo and Máximo Gómez. But was not Urrutia saying that in the 1930s, things seemed different from the Maceo and Gómez’s ideals? Was not precisely Urrutia’s claim that there were also internal ways in which racial discrimination was taking place amid the political conflict?

Like Du Bois, Urrutia was oriented towards the analysis of the global color line. However, during the 1930s, Urrutia went beyond Du Bois in unraveling the contextual configurations of race, especially between the United States and Cuba, regarding the strains of Spanish settler colonialism. Du Bois’s analysis always included the deep criticism of American Imperialism in Cuba; however, addressing Spanish settler colonialism and the color line in Latin America came almost a decade later for Du Bois with his stay in Cuba in 1941, which fed into his unpublished conference “The Future of Africa in America” in 1942.

Urrutia’s trans-American analysis is apparent in his “Race and Prejudice in Cuba” (Reference Urrutia and Cunrad1934), where he establishes comparisons and connections about racial prejudice between Cuba and the United States, pointing out the racial conflict differences.Footnote 25 Thus, while Anglo-Americans have no qualms about showing their “Negrophobia,” white Cubans (later referred to as Spanish Cubans), without confessing their feelings of rejection towards Blacks, attempt to “dissolve the black race in a torrent of Aryan blood, and aim at their extinction in every possible indirect way” (Urrutia Reference Urrutia and Cunrad1934, p. 474). Thus, although different, Urrutia points out that anti-Black racism in Cuba and the United States cannot have an end other than extermination because “[t]he ultimate aim in both cases is to exterminate the Negroes” (Urrutia Reference Urrutia and Cunrad1934, pp. 473-474). However, the difference between anti-Negro policy in the North and the Cuban republic “may be traced […] to the historical difference between the spirit of English colonization in the U.S. and that of Spanish colonization in the Great Antilles and a large part of America” (Urrutia Reference Urrutia and Cunrad1934, p. 474).

The difference between the North’s whiteness and that of the South is linked to colonialism and its legacy in the configuration of social relations. This legacy is expressed in the continuity of colonial patterns that persist in class inequality and the predominant forms of interaction. Thus, although different ways of operating, the colonial problem underlies the configuration of nations in the economic and socio-cultural plane.

There was a fusion of races in Spanish settler colonialism, but at the same time indigenous people were violated in the name of the accumulation of wealth and the empire’s expansion. Unlike in the United States, “when Indians suffered death at the hand of Spaniards, [in Latin America] it was not as enemies but as slaves” (Urrutia Reference Urrutia and Cunrad1934, p. 474). The Afro-Cuban author is interested in highlighting that the colonial difference between the two countries is also expressed during American Independence because the whites did not make concessions to the enslaved people to join the independence process.

Again, signaling the differences between the United States and Cuba allowed Urrutia to denounce racism in Cuba amid the myths of a raceless society:

But here we have the subtle and delicate part of the racial problem of Cuba. In private circles, and even in public life, anti-Negro prejudice finds its expression, not in open discriminations, as in the United States, but in quiet and surreptitious way. The Negro is not excluded, but some pretext is always found for not accepting him. He is not hated, but neither is he loved. He is not killed, he is not lynched, but he is left to die of starvation. The Negro population is not concentrated and driven away to a “Black belt” where it may perish through poor living conditions, but it is continually crossed with the white race, in order that it may become extinct. (Urrutia Reference Urrutia and Cunrad1934, pp. 475-476)

Although Urrutia initially conceived of Ideales de una raza with the purpose of “explaining the current ideology and feelings of the Black race [… and] the very important task of explaining to the white race our concept in each of our national problems” his thinking regarding the racial problem had changed over the years (Urrutia Reference Urrutia1928, p. 10). While Urrutia initially aimed to address the problem of “the white race’s lack of information on Black history and culture,” he later turned more to the analysis of the daily racial conflict, the denunciation of hypocrisy on racism, and the comparison of racism between Cuba and the United States.

Du Bois vis-à-vis Adelante: Critical Voices on Race and Nation in Democracy Building

The period from 1931 to 1941 covers Du Bois’s connection with Black intellectuals until his first visit to Cuba. The most significant exchange between Du Bois and Urrutia occurs in the 1930s. For Urrutia, the crisis in the early 1930s showed how Afro-Cubans participating in the protest against the Machado regime was indisputable proof of how integrated Black people were in the aspiration of a national democratic project. In this vein, he states “now, when least attention is paid to the Negro, as such, is precisely the time when he is giving the finest proof the disinterested patriotism […] It is the first occasion in which the Cuban Negro has not had a peculiar interest tied up in the political problem in which he is concerned” (Urrutia Reference Urrutia1931, p. 123). Langston Hughes’s translation work allowed Du Bois to include Urrutia’s piece about student protests against Machado in September 1930 and Du Bois decided to accompany Urrutia’s article with the Black hero’s image of the Cuban Independence, Antonio Maceo.Footnote 26

The political persecution unleashed by Machado as of January 1931 and the denunciations of the violent repression of the protests led to the suspension of Diario de La Marina along with eight other newspapers (Lima Sarmiento Reference Lima Sarmiento2014, pp. 60-61). The page Ideales de una raza, directed by Urrutia, was last published on January 4, 1931.Footnote 27 Nonetheless, it was not in vain that in July 1931, Langston Hughes asked Du Bois to grant the renewal of Urrutia’s subscription to The Crisis, pointing out that “[i]t is very important for Negro contacts that he continue to receive the magazine.”Footnote 28 Hughes gives relevance to Urrutia’s connections during Cuba’s economic depression due to the sugar disaster, provoked principally by the Hoover administration’s furious tariff protectionism.

Urrutia’s pieces in The Crisis referred not only to Black people’s central role in the nation’s formation but also to how, through political successions during the Republic, “the Negro found an absolute abstention, an inflexible policy of hands-off regarding all the vital economic and social problems whose solution would benefit his race alone, although injuring no one else” (Urrutia Reference Urrutia1931, p. 123). Amidst an economic crisis, Urrutia’s article in The Crisis could not but respond to the situation of economic damage to the Black population that was sustained through “racial prejudice.” Thus, the nation’s integration does not proceed harmoniously but is traversed by economic inequalities and a decisive racial conflict that did not seem to find a solution in the Machado regime. For this reason, Urrutia not only stated in his article for The Crisis that “there is no hope in traditional politics” (Urrutia Reference Urrutia1931, p. 123), but he continued to criticize the racial hierarchy in his column “Armonías.” In the texts written before the overthrow of Machado (August 1933), Urrutia appealed to the comparison between Cuba and the United States to denounce racism in both countries:

Of what value are the written laws, when the person for whom they were designed lacks the power to have them enforced? The racial problem of the American Negro and that of the Cuban Negro, though dissimilar in form, is essentially the same: the social and economic subordination of both groups to the white race and the danger of extinction. The North American kills the Negro. The Spanish Cuban leaves him to die. (Urrutia Reference Urrutia and Cunrad1934, p. 478)Footnote 29

Despite the idea of a raceless Cuba, Urrutia’s articles sent to Du Bois aimed at the trans-American form of anti-Black racism: the combination of subordination, the will of extinction, murder, and abandonment at the intersection of both slavery and colonialism’s aftermath. But Du Bois was not in the same line of argument as Urrutia regarding Cuba in the early 1930s. Though Du Bois was editing pieces about racial discrimination cases for The Crisis, his appreciation of the myth of a raceless society was more potent than his criticism of anti-Black racism in Cuba. As we shall see, this is consistent with his ethnographic writings when he visited Cuba. Indeed, racism in Cuba and the United States did not follow the same pattern. However, rather than comparing these two forms of racism as Urrutia did, Du Bois’s critique focused on the official American stance towards Cuba.

Notwithstanding, the Urrutia-Du Bois connection is valid for a trans-American critique on the distinct national forms in which imperialism, embedded in racism, condemns Black people to die. But Urrutia was not a lonely voice in Cuba. His ideas were anchored in various intellectual collectives. One of such collectives was the political-intellectual circle in the newspaper Adelante (1935–1939), which functioned as an expression of the anti-racist struggle. In this newspaper, the problem of Afro-Cubans was debated, and at the same time, economic justice was demanded in response to the political participation of Black people in the Cuban Nation.

In the monthly newspaper Adelante, Urrutia addressed the nation’s problem, as Du Bois did in his unpublished The Negro and Social Reconstruction from 1936.Footnote 30 Urrutia had a different stance on the so-called “Black nationalism” attributed to Du Bois, especially from his writings during his separation from the NAACP; however, both authors were concerned about the cynicism of a (failed) democratic society that embraced racial inequality. A possible connection in their thinking revolves around the intersection of the economic and political in addressing the racial question.

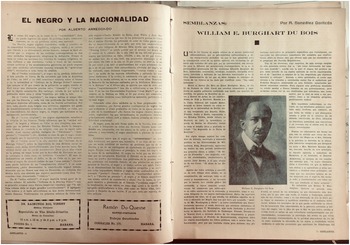

In the pages in Adelante (March 1936), Afro-Cuban journalist González Dorticós wrote a profile of W. E. B. Du Bois, in which the latter appears to be an analyst of the historical injustices against Black people in the United States, highlighting his intellectual conflict with Booker T. Washington and his research at Atlanta University (Fig. 1). Although in Adelante, the bibliographic work of Du Bois stands out, the reference to the knowledge of his work about the structural aspect of discrimination against Black people within national projects reveals a reading that this political-intellectual collective shared.

Figure 1. Du Bois in Adelante, March 1936. Photo by the author.

González Dorticós’ description of Du Bois is published next to journalist and anti-racist writer Alberto Arredondo’s piece “The Negro and the Problem of Nationality,” where he affirms that “the cause of the Negro is the cause of nationality” (Arredondo Reference Arredondo1936, p. 6). Arredondo represents the position that confronts the thesis of the communists who, in those years, raised the self-determination of Black people in a “Black belt” as resembling of communists in the United States (Guanche Reference Guanche2020).

In the early 1930s, the Cuban Communist Party (PCC) started to campaign for Black self-determination in the island’s Eastern region (i.e., Oriente Province) (Adi Reference Adi, West, Martin and Wilkins2009, Carr Reference Carr and Young2019). Founded in 1925, the PCC was initially dominated by European immigrants and showed some reluctance to recruit large numbers of Black members, especially Black workers from Jamaica and Haiti. However, under the influence of the Communist International and the U.S. communist party, in 1929, the PCC started to pay much more attention to the recruitment of Black members. By the time of the second congress of the party in 1934, the party exercised a public stance against racial discrimination and incorporated the struggle for Black workers’ rights. Congress also discussed “the need for greater clarification of the Negro Question as a national rather than ‘racial’ question typified in the slogan for self-determination of the Negros in the Black Belt of Oriente Province” (Adi Reference Adi, West, Martin and Wilkins2009, p. 167). Footnote 31

However, for the authors in Adelante, such as Arredondo, the idea of self-determination was an injustice since “the black, then, is not only part of the Nation, but also helped it to integrate into all its factors […] NATION AND NEGRO in Cuban society cannot dissociate themselves.” The emphasis on the nation as a community in the territorial, linguistic, religious, racial, and cultural order leads Arredondo to conclude that “the so-called negro problem is the location of its roots, not as something alien to the nation or artificially added to it, but rather as a vital factor, integrating and forging the nation” (Arredondo Reference Arredondo1936, p. 6).Footnote 32

Though Du Bois’s argument in The Negro and Social Reconstruction (1936) about the United States is different from Arredondo’s integrated nationalism in Cuba, for both, the debate about race and nation should not be considered in a separatist sense but insofar as it allowed for debate of the very concept of nation. I contend Du Bois’s famous statement of “a negro nation within the nation” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1935) indicated a specification of “double consciousness” in so far as it meant both Black autonomy and “the Negro” being vital to democratizing the larger nation. Du Bois always presented a frontal attack on the anti-statist liberalism that coexisted with segregation. As stated in The Negro and Social Reconstruction, for Du Bois, the task was clearly to produce public awareness that goes beyond the vision by which the Black population is seen only “in relation to the people of the United States”:

Of course, we believe in the ultimate uniting of mankind and in a unified American nation with economic classes and racial barriers leveled; but we believe that this ideal is to be realized only by such intensified class and race consciousness as will bring irresistible force rather than mere sentimental and moral appeal to bear on the motives and actions of men for justice and equality (Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Aptheker1936, p. 148).

According to Nikhil Pal Singh, when Du Bois, in the 1930s, described Black people as “a nation within a nation,” the term nation was, above all, a “mechanism of communication and common regulation that indicated the unique character of the density of the Black existence resulting from racial segregation” (Singh Reference Singh2004, p. 51). Therefore, Du Bois describes a response to the limitations of an exclusionary democracy that would not be so:

There was a time when the American Negroes thought of themselves simply in relation to the people of the United States and it was then that we argued that there could be but two methods of settling the Negro problem; either the Negro [would] be absorbed physically into the nation, or else he would die out by violence or neglect. Since the World War, this attitude has changed. Not only do we realize that the majority of the peoples of the world are colored, but we also realize that the unquestioned supremacy of the white race over these colored people has passed forever (Du Bois Reference Du Bois and Aptheker1936, p. 155).

Urrutia and Arredondo addressed the nation’s problem in a spirit that connects with Du Bois, in the times between the Great Depression and World War II which also was a moment of Black political thought reflected on the national question. Du Bois’s argument in The Negro and Social Reconstruction functioned as the basis for rejecting the assimilationist project (or Black assimilationism) of the United States Nation-State and demanded a political solution that allows the strengthening of common Black social interests. In the same phase, Du Bois (Reference Du Bois and Aptheker1936) considered that Black democratic participation in politics was a precondition for achieving social justice in the United States, not by avoiding the racial question or denying race, but by using the racial category to expand the field of the political debate.

In addition to Singh’s argument, where “a nation within a nation” points toward yet another dimension of “double consciousness,” Du Bois’s point toward the global color line transcends a narrow nationalist definition of the Black subject. Thus, Du Bois was neither an assimilationist nor was he a separatist. He framed his posture on Black autonomy within a project of radical democracy and social justice that became increasingly world-historical in understanding racialized modernity wherein the global color line was a pillar in the configuration of capitalism and imperialism. In concert with the previous Du Bois quote, this argument is not only valid for the United States, but furthermore for the pursuit of radical democracy and social justice in the Americas and the world.

Du Bois’s position was different from the Black belt argument of separatism, and in Adelante, Arredondo and Urrutia clearly opposed the thesis of a “Black belt” in Cuba. Like Du Bois, Urrutia in Adelante questioned the “demo-liberalism” and pointed out how to recreate the nation to resolve Afro-Cubans’ social and economic problems:

[I]f in spite of the fact that he aspires to erase all racial discrimination, the New Negro begins by locating himself as a Negro; by creating for himself a specific mental autonomy, of a group, this is not due to any regrettable lapse of logic or tactics. Such an attitude follows, on the contrary, from the fact that in reality the Negro is racially and injuriously differentiated in the economic and social aspects, and that he needs, in an unfailing way, to know in-depth and with his own conscience his position within the Cuban problematic […] When the New Negro forms his own values to mobilize them in favor of the community, he initiates this process of spiritual self-determination by defining for himself what the Negro means for the world and Cuba […] (Urrutia Reference Urrutia1937, p. 7).

Probably, Du Bois’s connection with Urrutia through The Crisis contributed to shoring up his position in favor of an existing and relatively autonomous public sphere, not only nationally but globally. Like Arredondo, Du Bois saw the Black people’s question vis-á-vis the configuration of the nation’s construction and the ability to see themselves as part of it but as a constitutive element for building democracy. Like Du Bois, Urrutia saw that such a democratic project could not set aside economic barriers. However, while for Arredondo “when speaking of an oppressed nation […] black and white symbolize the same unit of exploitation or abuse” (Reference Arredondo1936, p. 6), putting class differences above racial differences, Urrutia and Du Bois’s writings between 1931 and 1936 state racial disparities create oppression, inequality, and ultimately the failure of democracy. However, the three authors’ ideas are consistent in the belief that racial justice is necessary for true democracy.

Du Bois’s engagement with Cuba became especially significant in the 1940s. In general, it occurred within the effort to establish a global struggle against racism in the context of World War II, the struggles against fascism, and the New Deal. During this decade, Du Bois launched the journal Phylon which included a global project he called a “Chronicle of Race Relations” during his stay at Atlanta University. Within these conditions, researchers Du Bois and Irene Diggs decided on their first visit to Cuba on June 5th, 1941, where they encountered the Cuban color line.

Although Du Bois did not explore how racism persisted in Cuba, he pointed out how social and economic inequality was linked to racial discrimination. To some extent, Du Bois admitted to the myth of the raceless society in his writings aimed at a North American audience. Based on Du Bois’s ethnographic notes during his first stay in Cuba, the following section will show Du Bois’s two special observations about the Cuban color line. First, Du Bois emphasized how despite ideals for exterminating the Black race through miscegenation, cultural integration in Cuba prevailed. In this sense, Du Bois always considered Cuba as a non-white country and drew from here much of his perceptions of actual social life scenarios on the island. The other focus was the role of American imperialism in promoting the upsurge of racial divisions through economic domination.

The Cuban Color Line

What Du Bois initially conceived as ten days of “a quiet rest in a colored country” turned into space to expand his reflection on and connections with the Cuban color line.Footnote 33 Following the advice of the Puerto Rican historian Richard Pattee, Du Bois wrote to Fernando Ortiz, chair and founding member of the Afro-Cuban Studies Society,Footnote 34 to comment on his upcoming visit to Cuba.Footnote 35 Du Bois knew about the journal Estudios Afrocubanos through the communications Rayford Logan established with Ortiz around the Encyclopedia of the Negro project in 1937. Ortiz designed a schedule that included social events, a visit to the University of Havana, and a meeting with President Fulgencio Batista that did not happen.Footnote 36

Although prominent Du Bois biographer David Levering Lewis (Reference Lewis2000) mentions that Du Bois and Diggs’s stay in Havana “was certainly pleasant, but was less full than Du Bois would have wished” due to the unrealized plans to meet “the famed mulatto poet who had been enchanted by Langston Hughes ten years earlier, Nicolás Guillén,” Du Bois’s letters to friends and colleagues and also his agenda in Cuba seem to prove the contrary (p. 485).

During their two weeks in Cuba,Footnote 37 Du Bois and Diggs not only participated in an event at the Club Atenas, a venue of the Afro-Cuban intellectual elite,Footnote 38 but also toured the island of Cuba from its capital to the Oriente province, stopping in Santa Clara, Trinidad, and Camagüey, until reaching Santiago de Cuba. Miguel Ángel Céspedes, president of Club Atenas, addressed communications to authorities and associations “of color” in the provincial capitals announcing Du Bois and Diggs’ visit.Footnote 39 Therefore, Du Bois learned about the solid Cuban “colored” associations, especially those of the elite, but also those not in Havana.

“Cuba has a history which I have known in theory and now see partially in fact,” Du Bois affirmed after his tour of Cuba.Footnote 40 He was aware that his sociological view of places and people was necessarily limited but nevertheless could be significant for his understanding of the global color line. From the beginning, he intended to visit the different regions of the island and not only focus on the city of Havana but traveled to Oriente (East Region): a trip “that more colored Americans have not made.”Footnote 41 Du Bois wrote his first observations after his trip to the west of the island (from Havana to Pinar del Río),Footnote 42 however, they became more detailed and thoughtful when he traveled to Oriente.

The three brief writings of Du Bois in Cuba include “The Cuban Color Line,” “Color in Cuba,” “Economics and Politics,” as well as descriptions of daily life that were later printed in New York’s Black newspaper, Amsterdam News. In the section entitled “The Cuban Color line,” Du Bois recognizes the difficulties in capturing the variation of the color line when it is framed in a global sense:

It is difficult to sense and set down with any degree of accuracy so curiously vague a conception as ‘the color line.’[…] Yet here are certain facts which I give provisionally based on previous study and observation and on long conversation with people, white, brown and black in Cuba.Footnote 43

In their analysis of the sociology of Du Bois, Itzigsohn and Brown (Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020) demonstrate how for Du Bois, the “color line” is at the center of his understanding of modernity and subjectivity. At the same time, this understanding changes throughout his life. According to the authors, during the 1930s and 1940s, Du Bois’s knowledge of Karl Marx’s theories was vital for his analysis of racism and racial inequalities as “resulting from the need to justify a global system of exploitation and dispossession of people of color, based on colonialism” (Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020, p. 21). This perspective analyzes the global color line that runs through the books that Du Bois wrote in those years, especially Black Reconstruction (1935) and The World and Africa (1946). Thus, without neglecting the analysis of subjectivity, as shown especially in Dusk of Dawn of 1940, for Du Bois, the global color line is “the product of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade that led to the invention of whiteness, and the denial of humanity of racialized groups and the multiple forms of exclusion, oppression, exploitation, and inequality constructed along racial lines” (Itzigsohn and Brown, Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020, p. 218).

Du Bois’s writing on “The Cuban Color Line” in 1941 is part of this process of analytical re-elaboration of the global color line when, in this brief text, he refers to slavery and migration in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Cuba. Du Bois’s observation and previous studies feed his own reading in which the configuration of the color line in Cuba is understood within a cultural integration that has more relevance, in analytical terms, than physical miscegenation. In this regard, Du Bois says, “the result has been an intermingling of blood which makes Cuba on the whole a country of octoroons”Footnote 44 while pointing out a cultural integration with economic inequality reproduction:

Physical miscegenation is less significant than the culture integration. More than most countries of mixed Negro and white blood Cuba is culturally unified […] the culture contacts between black, brown, yellow, and white are interrupted only by economic differences.Footnote 45

Du Bois did point out that the unification of culture (i.e., Afro-Cubans’ participation in all spheres of social activity) is traversed by economic inequality. He says that “the Cuban racial situation is quite different from that in Jamaica, Haiti, and the United States,” since it is a unification that exists, but in coexistence with the inequity that significantly affects the population of color—an inequality constructed along racial lines.

Du Bois’s words about “The Cuban Color line” resonate with Urrutia’s. It is not difficult to assume that the Afro-Cuban intellectual Gustavo Urrutia was among the interlocutors with whom Du Bois had “long conversations.”Footnote 46 However, it seems that, instead of following Urrutia’s perspective, which clearly emphasized the place of “racial prejudice” among Cubans in the reproduction of social inequality, Du Bois reframed such a critique in a manner that would take the criticism toward how racism is the basis of American imperialism:

Wealth and riotous wealth is only manifest in the great white capitals of the world. White Americans in a country like Cuba represent [a] color caste which they can force upon Cubans by their economic power. But more than this and the cause of this is that America has control of all powerful capital and capital Cuba needs and begs for it on its knees. Cuba alone knows no color caste. It has no race segregation or race discrimination but it does have social patterns along the color line enforced only by general consent except when America puts behind it [a] color caste, discrimination in wage and military force.Footnote 47

There are some critical aspects derived from this quote in which terms like “color caste,” “race discrimination,” “social patterns,” and “general consent” are connected. Du Bois does not explicitly point to the way racism operates within the Cuban population. Instead, he states that “Cuba alone” has “no color caste” and “no race discrimination.” Here, Du Bois aligns with the shared African American vision of Cuba during the 1930s and 1940s. However, unlike the Afro-Cuban authors’ description of social reality, Du Bois mistakenly says no racial discrimination exists in Cuba. Indeed, Du Bois’s words were reproducing a narrative challenged by groups such as Adelante and other leftist organizations during the 1930s (see Guanche Reference Guanche2017).

In his writings on Cuba, Du Bois’s apparent contradiction comes from how he implicitly assumed that “no color caste” (as exists in the United States) necessarily meant “no race discrimination.” In 1933, Du Bois used “color caste” to refer to a set of constraints against Black people through restrictions on interracial marriage, poor living conditions, restrictions to commerce and education, precarious working conditions, barriers to organizing or participating in the workers’ unions, denial of political representation, illegal disfranchisement, and inadequate heatlh care. In short, color caste expresses how “it is practically impossible for any Negro in the United States, no matter how small his heritage of Negro blood may be, to meet his fellow citizens on terms of equality without being made a subject of all sorts of discriminations, embarrassments, and insults” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1933, p. 60). Though Du Bois acknowledges “it would, of course, be untrue to say that of all these restrictions happen to all Negroes at all times,” his description is “a true picture of the caste situation in the United States” (Reference Du Bois1933, p. 60).

Thus, Du Bois denounced the existence of a de-facto “color caste” in the United States to argue against those “well-meaning citizens […] who seem to be under the impression that the main lines of the Negro problem are settled, and […] that the average Negro who is not too impatient should be willing to proceed toward his ultimate goal by quiet progress and unemotional appeal” (Du Bois Reference Du Bois1933, p. 59). However, understanding Cuba would precisely imply getting to how racial discrimination, despite the absence of segregation or other signs of the “caste situation” he saw in the United States persists. It is the “social patterns along the color line enforced only by general consent” that explain how anti-Black racism continued in Cuba after Independence.

Yet, Du Bois’s approach to Cuba never separated from his constant struggle against racism in the United States. Du Bois’s writings clarified that the Cuban color line’s configuration does not occur like in the Jim Crow United States. As Itzigsohn and Brown (Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020) point out, the dimensions of the global color line, analytically speaking, imply considering the racial divisions in the configuration of colonialism. Thus, Du Bois pointed to a complex reconfiguration of colonialism through the presence of a global color caste (i.e., “white Americans in a country like Cuba represent color caste,” “the white capitals of the world”), military force, and economic power.

Thus, in Du Bois’s approach to Cuba, he lays out U.S. White imperial racism against Cubans. Both Du Bois and Urrutia succeed in pointing out this element, as Urrutia wrote in his comparative analysis:

Despite the essential difference between the anti-Negro tradition of the United States and that of Cuba, we feel more and more every day the influence of the prejudice à la américane. The economic pressure of that country over ours counts for as much as intellectual influence (Urrutia Reference Urrutia and Cunrad1934, p. 478).

Urrutia’s texts emphasize the limitations of the Cuban political class in promoting an egalitarian project beyond cultural integration. At the same time, Du Bois emphasizes how North American interventionism constitutes not only a barrier but a structural element in the impossibility of an egalitarian society in Cuba. Thus, for Du Bois, the color line is not only constituted from the dimension resulting from the legacy of slavery and colonialism, but its current expressions are also the result of neo-colonialism. Both dimensions are global.

At the same time, for Du Bois, the cultural integration that Urrutia had pointed out is essential in terms of recognition. His observations on different cities in Cuba describe everyday scenarios that, as ethnographic notes, serve to support his appreciation of cultural integration. Du Bois says:

I have spent a week motoring between Havana and Santiago de Cuba, twelve hundred miles […] I have seen the city square and its meaning. I know the New England Common and the public squares of the continent, but I had never seen anything quite like the Cuban city squares.Footnote 48

Du Bois traveled through regions of the country in search of different expressions of the color line:

[T]he village is there or the city is there represented on the whole according to its social strata: there are white people, yellow people, browns and blacks. The blacks are less often represented but they are always there. Sometimes but not always there are servants […] It is a lovely social occasion […] this keeps up until midnight; in some cities until early morning.Footnote 49

In addition to the description of public squares, Du Bois sees the monuments of people of color in Cuba, without anything similar in the United States, as signs of “prestige and honor.” “Maceo and Gomez, brown and white, have the most magnificent statues in the city,” remarked Du Bois. He maintains the same impression in describing his encounters with personalities and spaces for socialization in eastern Cuba.Footnote 50

Du Bois’s approach to these urban settings is certainly celebratory. But his brief writings in Cuba are also traversed by understanding the play of forces between cultural integration and the historical conditions of the color line’s formation. Thus, the value of such cultural integration lies in constituting itself before the purposes of whitening by way of miscegenation, since for Du Bois there is “[n]o doubt in miscegenation the tendency has been deliberately to breed white but on the other hand the black element stands and not without prestige and honor.”Footnote 51

In conclusion, Du Bois points out that in Cuba, there would be no discrimination as in the United States, but that the Color line in Cuba manifests itself as an effect of economic exclusion. In this sense, racism in Cuba would be an expression of how the color line is reinforced, not only from internal economic dynamics but also from the imposition of the colonial agenda of the United States on Cuba. In this regard, Du Bois’s reading of Cuba as a raceless society might seem idealistic. Still, it is also clear that there is no possible analysis of the Cuban Color Line without considering the American colonial interests.

Concluding Remarks

This paper shows how, on the one hand, Du Bois only partially grasped how racism worked in Cuba. Probably, his mistaken vision about Cuba as a raceless society came from the fact that racial barriers were not legally established in Cuba and that cultural integration made the country a particular “darker” place of the world.Footnote 52 On the other hand, Du Bois always envisaged the color line as an effect of global conditions, colonialism, and economic inequality. His understanding of the conflict between racism and the political projects for Black liberation in Cuba was continually subjected to his political stand against U.S. Imperialism.

Du Bois’s many references to racial relations in Cuba were important in his criticism of racism and nationalism within the United States. Although there have been cultural and social integration processes in Cuba, the economic inequality that mainly affects the Black population constitutes the basis for the reconfiguration of racial barriers. The separation between the economic problem and the racial issue does not constitute an analytical input for Du Bois. Incorporating the color line analysis as an ordering of economic relations precisely prevents such separation. The analysis of racism in Cuba goes through investigating how the color line is reinforced or reconstructed in the political and economic fields.

In this regard, Du Bois’ writings about Cuba advance the literature on Du Boisian global sociology. Indeed, the relationship between Du Bois and Cuba confirmed the understanding of the color line in global terms. However, Du Bois sees Cuba as culturally integrated, and if there is racism, it is based on economic exclusion resulting from U.S. imperialism. Thus, in tracing race and class conflicts in Cuba to U.S. corporations, military power, and policies of control over the Cuban local economy, Du Bois did not look at the social sources of racism on the island. In this sense, the findings about Cuba not only mark a similar pattern to the case of Brazil, in which Du Bois appears to reproduce the myth of racial harmony (Góes Reference Góes2022) but also takes the critique further. Even though the U.S. had not yet entered World War II by the time of Du Bois’s first visit to Cuba, he emphasized American imperialism as a global menace. At the same time, he neglected the local configuration of racial barriers at the national level.

As argued in his two 1940s historical sociology books about European colonialism in Africa (Color and Democracy and The World and Africa), Du Bois sees that the problem of race and class in Cuba does not escape the global politics of imperialism. In this regard, Du Bois surpassed the problem of the ‘national line’ (Jung Reference Jung2015b, p. 193) from a perspective of racism intrinsically connected to colonialism and imperialism. This makes Du Bois a sociologist of a global system of white supremacy (King Reference King2019, pp. 20-21). Hence, what Du Bois’s analysis of the Cuban color line is missing are the mechanisms, the connections leading from global imperialism to local racism and from the local back to the global. If Du Bois had engaged with Urrutia’s perceptive analysis of racism in Cuba and his trans-American critique, Du Bois’s global sociology would have developed further a perspective on the interactions of racial and class systems in the Americas.

As in the literature I discussed in the first section, articulating a Du Boisian sociology affirms the critical value of Du Bois’s perspective on race and colonialism. While there are elements of Du Bois’s writings about Cuba that should be praised, especially for developing an analysis of the Latin American color line from a Du Boisian perspective, we should consider Du Bois’s inability to appreciate the nature of racism in Cuba as a tension undermining his ability to understand colonialism and coloniality. This tension seems to be critical for a Du Boisian sociology, or, in other words, it reveals how Du Bois was not fully Du Boisian regarding Cuba, since rather than “a contrast and comparison of local and historical contexts,”Footnote 53 he affirmed the determination of imperialism, assuming that the abolition of imperialism would free Cuba from racism. Notwithstanding, since a Du Boisian sociology “begins with Du Bois’s work but ultimately transcends it” while “incorporating the work of other scholars denied” (Itzigsohn and Brown Reference Itzigsohn and Brown2020, pp. 191-192), the analysis of Du Bois and Cuba contributes to a Du Boisian Sociology. A Du Boisian sociology which is global, anti-racist, and anti-colonial needs to analyze Du Bois’s sociology developing along perspectives such as those of the Adelante collective, Urrutia, or other intellectual activists committed to racial justice across the Americas.