Contrary to the stereotypical image sometimes conveyed by banking agents, the Swiss financial centre is not impervious to crises or to recessionary phases resulting in restructuring (Breiding Reference Breiding2013, p. 137). The model of a stable and financially prudent Switzerland was established in the 1960s and 1970s, as the Swiss banking sector experienced strong growth, which paved the way for a teleological vision of its development. The Swiss banker became a figure strongly associated with characteristics such as security, discretion and stability, which became during the second half of the twentieth century cardinal values of the financial centre's success (Baumann and Rutsch Reference Baumann and Rutsch2008, p. 11). In 1964, Franz Ritzmann, a Zurich economist whose pioneering work on the development of the Swiss banking system served as the basis for the new statistical data in this article, stated that ‘in terms of size structure measured by the balance sheet total, … our banking system is extraordinarily stable’ (Ritzmann Reference Ritzmann1964, p. 256). Nine years later, in his habilitation thesis, Ritzmann painted a positive picture of the historical development of banks that, since the nineteenth century, have led the country towards monetary abundance, low interest rates and a strong export of capital (Ritzmann Reference Ritzmann1973, p. 119). At the turn of the 1970s, in the dual context of a period of strong international expansion of Swiss banks and the absence for three decades of major banking debacles, the portrayal of a very stable financial centre, unaffected by crises, took hold.

Since the 1990s and following the major revival of the issue of banking instability after the 2007–8 global financial crisis, this dominant narrative has been more and more challenged by scholars (Mazbouri, Guex and Lopez Reference Mazbouri, Guex, Lopez, Halbeisen, Müller and Veyrassat2012, pp. 499–510; Mazbouri Reference Mazbouri and Lescure2016; Straumann and Gabathuler Reference Straumann, Gabathuler, Jans, Lengwiler and Passardi2018, pp. 37–49). In line with this perspective, our article addresses the issue of Swiss banking institutions’ stability through an analysis of banking demography by a statistical approach focused on the census of individual firms. In doing so, this article contributes debates around three interrelated approaches and objects of research. In the field of business history, it contributes to the research on the longevity of companies and the historical restructuring of an economic sector, based on an approach founded on corporate demography (Carroll and Hannan Reference Carroll and Hannan2000). Secondly, it examines the relationship between the disappearance of an institution, a potential sectoral crisis and a possible social or political reaction. Finally, it forms part of the study of the revival of the history of the Swiss financial centre, and seeks to understand why bank failures in Switzerland have had relatively limited destabilising effects. By providing a new serial analysis of the exits of banks from the statistics for a period of 150 years, this article also offers a methodological innovation: the data collected shed light on several characteristics of the outgoing banks: their category, their age, their location and, for the period 1934–99, their size.

This article is divided into four parts. The introductory section addresses the issues raised by the definition of financial and banking crises, in order to specify the criteria from which we have built our census of banking demography in Switzerland. The second step first briefly discusses the different phases of banking crises identified by historiography dealing with the Swiss case for the period studied (1850–2000); then we present the sources that we have mobilised to develop our database. The third and central section presents the main research results. Six periods of ‘excess banking mortality’ (which are not necessarily periods of crisis) are identified, as well as, for each of them, the type of the institutions concerned. In conclusion, we offer some provisional reflections on the reasons why, despite obvious phases of imbalances or even crises, the Swiss financial centre was perceived and presented, from the 1960s and 1970s onwards, as an example of stability.

I

We know Charles Kindleberger's joke, that financial crises are like great love: ‘hard to define but recognizable when encountered’ (cited by Cassis Reference Cassis2011, p. 3). And if humour does indeed mark a form of distancing, Kindleberger's quip is a very timely reminder that in terms of definitions, a certain reflective vigilance is always required in history.

The same applies to the concept of both a banking crisis and a financial crisis. Both come together in the polysemy of the word ‘crisis’, which originates from the world of medicine and which designates both a crucial juncture (critical, dangerous, high point, etc.) and a process of transformation, a tipping point from one state to another. The most orthodox proponents of neoclassical economic theories deny the very possibility of this, while for others a crisis, whether economic, financial or banking, constitutes an intrinsic feature of the workings – in the Marxist tradition, of contradictions – of the capitalist system (Minsky Reference Minsky, Kindleberger and Laffargue1982; Kindleberger Reference Kindleberger1989, pp. 243–8 Appendix A to 2nd edition; Gorton Reference Gorton2012, pp. 29–44, 87–97; Sarkar Reference Sarkar2012, pp. 3–93). The general theories on banking crises that focus on banking structures struggle to explain historically the probability of crisis occurrences in different countries and in different periods (Calomiris and Haber Reference Calomiris and Haber2014, pp. 479–84).

There are so many issues involved that defining the nature of a banking crisis on a scientific level is not an easier exercise, nor is it a fortiori better removed from the risks of arbitrariness, anachronisms or instrumentalisation, than defining what we recognise as a financial crisis (Hansen Reference Hansen2012; Mazbouri and Giddey Reference Mazbouri and Giddey2020).

In this contribution we will focus exclusively on so-called banking crises, a particular form of financial crisis, knowing, however, that these categorisations are relative and questionable, as the different types of crisis (banking, foreign exchange, stock market, etc.) can indeed accumulate and interact with each other (Sundararajan and Baliño Reference Sundararajan, Baliño, Sundararajan and Baliño1991; Bordo et al. Reference Bordo, Eichengreen, Klingebiel, Martinez-Peria and Rose2001; Grossman Reference Grossman, Cassis, Grossman and Schenk2016).

The causes of these crises, often explained by psychological components (exaggerated enthusiasm for lucrative investments, delusions of grandeur, bias through overconfidence, hubris), technical-cognitive factors (poor distribution or anticipation of risks, false balance sheets, poorly supervised financial innovations, informational asymmetry) or organisational elements (failure of internal control, lack of prudent organisation), will not be addressed here. However, these types of microeconomic explanations tend to ignore possible structural determinants, the crises coming from errors of judgment (individual or collective) and organisational dysfunctionality (Calomiris Reference Calomiris2010; Casson Reference Casson, Hollow, Akinbami and Michie2016). In the same way, we will not discuss here the cyclical nature (or not) of these crises, which ‘punctuate the history of capitalism’ (Boyer Reference Boyer2013), nor their effects (aftermath), macroeconomic and political, which can be devastating (Friedman and Schwartz Reference Friedman and Schwartz1963, pp. 299ff.; Bernanke Reference Bernanke1983; Sundararajan and Baliño Reference Sundararajan, Baliño, Sundararajan and Baliño1991; Pecorari Reference Pecorari and Pecorari2006; Reinhart and Rogoff Reference Reinhart and Rogoff2009, pp. 466–72; Gorton Reference Gorton2012, pp. 165–80).

Even thus defined, the object of our study continues to pose serious problems of identification. Some are inherent in any retrospective statistical enterprise, since the period we are dealing with here runs from 1850 to 2000 and the definition of what a bank is, let alone what a banking crisis is, varies in diachrony (Bond Reference Bond, Hollow, Akinbami and Michie2016, pp. 85–9). To illustrate this point, in 1850 the bulk of the Swiss banking sector was composed of some 150 savings banks, while in 2000, it was dominated by a duopoly of internationalised financial giants (UBS and Credit Suisse's combined assets amounting to 63 per cent of all the banks’ assets).Footnote 1 Other commentators have varying ideas as to what is meant, from a synchronic perspective, by a banking crisis. Indeed, although various definitions abound, there is no firm consensus on the variables to be considered in order to identify the threshold at which we move from specific and isolated difficulties to a real sectoral crisis, whether of a local, regional, national or international dimension (Romer and Romer Reference Romer and Romer2017).

Depending on the authors and the crises analysed, both quantitative and qualitative criteria are thus retained, individually or collectively, such as: the failure of a particularly important bank (Grossman Reference Grossman1993); the number of bank failures (Grossman Reference Grossman1994); the number of bank failures in relation to all banks or the amount of capital losses incurred, themselves measured by the change in the value of shares (share price) at market prices (Turner Reference Turner2014, p. 253); the nature of the impact of these failures on the evolution of GDP (Grossman Reference Grossman1993); the relationship between the mass of bank loans and GDP (Schularick and Taylor Reference Schularick and Taylor2012); the number of times that the OECD's periodic directories have mentioned the existence of financial distress affecting a given national economy (Romer and Romer Reference Romer and Romer2017); or a marked imbalance between the amount of bank liabilities and the market value of their assets (Sundararajan and Baliño Reference Sundararajan, Baliño, Sundararajan and Baliño1991). The very nature of our approach, which covers 150 years of Swiss banking history, has forced us to discard certain variables that are unfortunately unusable, due to the lack of quantitative data available in the long term.

Based on these definitions, we will favour a dual approach. On the one hand, a relevant quantitative dimension, which essentially concerns a study of banking demography (see Sections II and III of this article): we aim to identify, in the long term, the major phases of banking mortality in Switzerland. The corporate demography approach forms part of the perspective of organisational ecology, which seeks to study institutions in a manner analogous to other types of demographics, analysing in particular their form of organisation, their birth, their disappearance and their lifespan (Carroll and Hannan Reference Carroll and Hannan2000).

We then combine this with a more qualitative approach, in which the crisis is said to be defined ‘by events’, in the sense described by C. M. Reinhart and K. S. Rogoff. These authors thus retain two families of events that signal, according to them, the presence of a banking crisis. The first instance refers to massive withdrawals of deposits that led to the closure, merger or nationalisation, by the public authorities, of one or more financial institutions (the so-called ‘severe’ crisis: typically, in the case of Switzerland, the crash of the banks of Ticino in 1914). Secondly, in the absence of a run (a less severe crisis: typically, in the case of Switzerland, the large bank mergers occurring in the aftermath of World War II), the closure, merger, takeover or massive support, by the public authorities, of a major financial institution, marked the beginning of similar difficulties for other financial operators (Reinhart and Rogoff Reference Reinhart and Rogoff2009, pp. 11–12). R. S. Grossman adds, in an interesting perspective also adopted here, that the preventive action of public authorities or a group of actors to prevent a major bank or a series of financial institutions from going bankrupt is also a type of event indicative of a crisis situation (Grossman Reference Grossman, Cassis, Grossman and Schenk2016, pp. 441–2). The case of the reorganisation of Switzerland's oldest bank, Leu & Cie Bank in Zurich, in the 1930s, is a perfect illustration of this situation.

II

Swiss banking historiography, although generally not very detailed on the crises affecting the banking sector in Switzerland, nevertheless allows a first identification of banking crises, both by figures and aggregates, and ‘by events’. Thus, the economist F. Ritzmann, whose book published in 1973 is still referred to today, schematically distinguishes two major phases in the development of banks in Switzerland (Ritzmann Reference Ritzmann1973). Relying mainly on qualitative data, he first identifies a period of emergence and expansion, between 1850 and 1880. Marked by severe crises due to the ‘childhood diseases’ of the first banks of the Crédit Mobilier type, this sequence gave birth, not without pain (in particular the crises of 1870–2 and 1890–1), to the two pillars of the Swiss banking structure of the twentieth century: the large commercial banks and the cantonal banks (regional, by canton). The Sturm und Drang was followed, between 1890 and 1950, by a more tumultuous phase of concentration and consolidation. The author does not dwell on the 1930s crises, which have since been the subject of much research; however, he identifies a period of ‘high banking mortality’ between 1910 and 1914 (Ritzmann Reference Ritzmann1973, p. 105), the primary causes of which are linked to the consequences of the end of the era of free banking in Switzerland (Wetter Reference Wetter1918; Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann1987, p. 301; Weber Reference Weber and Dowd1992; on the banking crisis of the 1930s, see notably Perrenoud et al. Reference Perrenoud2002; Baumann Reference Baumann2007). Another more precise periodisation, with five phases, has been proposed for the historical development of the Swiss financial centre during the twentieth century (Mazbouri et al. Reference Mazbouri, Guex, Lopez, Halbeisen, Müller and Veyrassat2012, pp. 467–518). Among these five phases, identified in the light of the development of balance sheet totals, three periods of crises, restructuring and slowdowns have been identified. The first – which has its origins in the increased interbank competition caused by the creation of the central bank – is situated in the years that encompassed World War I (1913–19), the second extends from the Great Depression of the 1930s to the end of World War II (1931–45), and the third coincides with the economic difficulties of the early 1990s. Finally, a recent publication on the regulation of the financial sector in Switzerland devotes a few pages to a historical analysis of the occurrence of crises (Straumann and Gabathuler Reference Straumann, Gabathuler, Jans, Lengwiler and Passardi2018, pp. 65–71). The authors distinguish between classic banking crises, which manifest themselves in the depreciation of assets and the reduction of deposits, and ‘integrity’ crises, which centre around international criticisms of the activities of Swiss finance, and affect its reputational capital more than its economic performance. When considering both types of crises, only two phases of high propensity for crises are diagnosed: the interwar period and the last three decades of the twentieth century. These two periods were also marked by the introduction of regulatory legislation, which generally signals the presence of a pre-existing crisis. One can extend this brief bibliographic overview of international literature by citing C. M. Reinhart and K. S. Rogoff, who, in their study on the history of world financial crises, identify three phases of banking crises in Switzerland (1870–1, 1910–13, 1931–3) during the analysed period, covering the whole of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, right up to the subprime crisis (on Switzerland, Reinhart and Rogoff based their work on the contribution of the archivist at UBS, Vogler Reference Vogler2001; Reinhart and Rogoff Reference Reinhart and Rogoff2009, p. 384). Another recent paper by economists Junge and Kugler provides a quantitative view on the costs and benefits of capital requirements for financial stability (Junge and Kugler Reference Junge and Kugler2013). Their analysis, based on historical data on leverage levels between 1880 and 2010, shows how higher capital requirements significantly reduce the probability of banking crises. Finally, a 2009 PhD dissertation provides a quantitative exploration and identification of banking crises in Switzerland (Drechsel Reference Drechsel2009, pp. 77–119). Based on a banking distress measure constructed from balance sheet data, its author identifies, between 1906 and 2000, six periods of major distress for the Swiss banks: the bank consolidation 1911–14, the post-World War I inflation, the Great Depression of the 1930s, the post-World War II effects, the turbulent 1970s and the mortgage crisis of the 1990s (Drechsel Reference Drechsel2009, p. 101). This analysis is also conducted at the bank group level, showing that the regional and savings banks group has suffered during each banking crisis, while cantonal and large banks have only been affected in the 1990s and 1930s respectively.

The statistical series that we propose here confirms to a large extent these periodisations, but also complements them usefully, in particular in a long-term perspective (1850–2000). Like recent research on English banking demography, from which it takes its inspiration, it also makes it possible to refine the subject, and provides a clearer picture of the evolution of banking structures (Garnett, Mollan and Bentley Reference Garnett, Mollan and Bentley2015; Bond Reference Bond, Hollow, Akinbami and Michie2016). Admittedly, the enumeration of outgoing banks does not always make it possible to establish the causes of the banking disappearances observed, which, as J. D. Turner points out, do not necessarily imply a situation of systemic instability, while conversely, a crisis situation is not always marked by high banking mortality (Turner Reference Turner2014, p. 50). However, an ‘event-based’ approach can remedy these problems, at least in part.

The period we take under consideration in this article coincides, roughly, with two major events in the history of the evolution of Swiss banking structures. The opening event involved the creation of the modern federal state in 1848, which allowed the first decompartmentalisation of the market, hitherto considered compartmentalised between agents active internationally (private banks essentially) and those whose operations were either local or regional (savings banks essentially) (Bergier Reference Bergier1984, p. 310; Mazbouri Reference Mazbouri2005, pp. 158ff.). We end our investigation in 2000, which concluded a historic sequence, marked by a profound mortgage crisis, and an intense process of concentration that led, in 1998, to the merger between the Swiss Bank Corporation and the Union of Swiss Banks, which then formed UBS, one of the largest banks in the world (Mazbouri et al. Reference Mazbouri, Guex, Lopez, Halbeisen, Müller and Veyrassat2012, pp. 526–32).Footnote 2

We have produced this series using two main sources. Firstly, we consulted the ‘banking chronicle’ articulated by F. Ritzmann in the early 1970s. This remarkable work, given the state of primary sources for the ninteenth century, is a retrospective chronicle covering the period 1850–1967; as the author indicates, this inventory of the birth and disappearance of banks in Switzerland clearly suffers from certain approximations (Ritzmann Reference Ritzmann1973, pp. 257–373). Ritzmann's inventory takes as a statistical unit the company name of the firm and sets the date of disappearance of a bank as the beginning of the liquidation. Our own statistics therefore also record company names without taking account of any branches, which can introduce a bias, knowing that a branch closure is sometimes symptomatic of a crisis situation (Molteni Reference Molteni2021, pp. 244–51). For the more recent period (1968–2000), the official statistics of the Swiss National Bank were used (Schweizerische Nationalbank corresponding years, section Weglassungen und Neuaufnahmen von Instituten).

Like I. Bond, we have solved the problem of diachronic variations of definitions by considering that a bank is what contemporaries consider it to be, in their time (Bond Reference Bond, Hollow, Akinbami and Michie2016, p. 87). Thus, the savings banks, which dominated in terms of numbers and probably as regards the total of deposits in the Swiss banking architecture of the 1850s, are counted in this census, despite the fact that many of them, for example, did not grant loans to individuals or companies (on the particular trajectory of French savings banks in the 1930s, see the recent research by Monnet, Riva and Ungaro Reference Monnet, Riva and Ungaro2021). The question of the statistical categories used to identify, over time, the different types of banks presents greater difficulties. We have selected eight types of banks: cantonal (regional, by canton) banks, large banks, local banks, mortgage banks, savings banks, other banks, financial companies and private banks (Wermelinger and Rosenfellner Reference Wermelinger and Rosenfellner2009, pp. 12–13).Footnote 3 The classification by category of bank poses serious methodological difficulties, due to their evolution: the categories and the economic realities to which they correspond have shifted over time. A small cantonal bank can be very similar, in size and scope of activities, to a large local savings bank. Classifying banks, which makes it possible to have equivalent comparisons of categories over the long term, tends to produce continuity effects in cases where tumultuous changes actually led to major crises. The disappearance, for example, of issuing banks at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries thus passes under the radar, as the category under which they had been listed until then also disappeared, while the group of large banks, which are relatively recent in the nomenclature, appear, wrongly, to have actually existed since the 1850s.

In addition to the classification by category, four other items of information have been inventoried: the number of failures and takeovers, the longevity of the banks that have disappeared, their location, and the size of their assets (only available for the period 1935–2000). Our census includes a total of 398 failures and 474 takeovers.

III

This new statistical series makes it possible to count the number of disappearances in the banking population (in other words the exits from the demographic series), and to identify phases of high mortality. In addition to failures and liquidations, forms of exit that involve the dissolution of a banking institution, we have chosen to also list takeovers, i.e. the integration of one or more companies into another (with one existing company name remaining). Indeed, a key issue in this contribution is the identification of a period prone to crises. Yet, in many cases, and this is more frequent when the size of the institution is an important factor, the collapse of a financial institution results in a restructuring programme that involves the acquisition of the company in difficulty by a healthy bank (Pohl and Tortella Reference Pohl and Tortella2001, p. 344; Carletti and Hartmann Reference Carletti, Hartmann and Mizen2003). The purpose of such transactions may be to avoid the systemic repercussions of ordinary bankruptcy proceedings, or to escape the constraints of using deposit insurance. The takeover of a failing bank – rather than its liquidation – also has a mitigating effect on the publicity of the event. Negotiations between sellers and buyers can take place away from media scrutiny, which is not necessarily the case when a liquidation takes place in the judicial arena. Similarly, any parties adversely affected by such events can be compensated amicably, cutting short the forming of any potential alliance of social groups and professional circles less directly concerned. Let us quote only one example of this phenomenon: in 1945, the end of World War II was marked in Switzerland by a profound restructuring of the group of large banks (Giddey Reference Giddey2019, pp. 345–54). The Federal Bank (Eidgenössische Bank) and the Commercial Bank of Basle (Basler Handelsbank), which had been financially bled dry after the crisis of the 1930s, were in a very precarious situation after the collapse of the economic structures of the Third Reich. Following intense negotiations sponsored by the federal authorities, their healthy assets were respectively taken over by two competitors, UBS and SBC (Perrenoud et al. Reference Perrenoud2002, pp. 262–72). These operations made it possible to avoid a state bailout and a possible crisis of systemic confidence.

Admittedly, any merger, takeover or disappearance does not necessarily signal a crisis situation: depending on the historical phase considered and the particular circumstances of the takeover, this type of event can at the same time have effects that are negative (and traumatic: for example, for regional actors, loss of independence or the disappearance of an establishment important for the local economy can ensue) and/or positive (for example, at the national level: consolidation/modernisation of the banking system, external expansion strategies, etc.). However, when viewed over the long term, periods during which mergers and takeovers intensify always mark cycles of less stability in the banking sector, or a phase of change and/or a break.

Figure 1 shows the number of bank failures and takeovers over a long-term period (1848–2000). The diagram also includes the evolution of the total banking population (right horizontal axis), which makes it possible to correlate the number of bank disappearances with the total number of institutes. On average, over the entire period considered, just under six banks disappeared each year. Beyond the averaged data – which is not very telling over the long term, as this representation gives an overview of particularly turbulent periods – the chart offers a seismography, admittedly partial and at times misleading, of the (in-)stability of banks in Switzerland. Figure 2 provides a more nuanced representation of the fluctuations in bank disappearances (failures and takeovers). Indeed, it reports the number of banks that fail or are taken over each year in relation to the total banking population.

Figure 1. Bank failures and takeovers in Switzerland (1848–2000)

Sources: Authors’ calculation. Failures and takeovers: 1848–1965: Ritzmann Reference Ritzmann1973, pp. 257–373; 1966–2000: Schweizerische Nationalbank corresponding years, section Weglassungen und Neuaufnahmen von Instituten. Banking population: 1848–1906: Ritzmann Reference Ritzmann1973, pp. 263–6 table 1; 1907–92: Ritzmann-Blickenstorfer Reference Ritzmann-Blickenstorfer1996, table O.13, completed for the categories branches of foreign banks and private bankers (1935–63) with Schweizerische Nationalbank 1993–2000. The increase from 398 to 480 units between 1934 and 1935 is explained by the introduction of the Banking Act in 1934, which implies an expansion of the number of institutions accounted for.

Figure 2. Ratio of bank failures and takeovers (proportion between the number of failures and takeovers respectively, and the total banking sphere), 1850–2000, five-year average

Sources: see Figure 1.

Taking into account both failures and takeovers, we note that four phases are clearly distinguished by a high bank mortality (with a ratio of failures and takeovers of more than 2 per cent): 1910–14, 1920–4, 1975–9, 1990–2000. In Figure 2, in distinguishing between failures and takeovers, it is necessary to highlight the significant difference between the two series during certain periods. At the end of the nineteenth century (1880–94), failures were relatively higher than takeovers. This same trend, with a higher ratio of failures than of recoveries, also characterises the great financial crisis of the 1930s. Conversely, the restructuring phases of the banking system in the late 1970s and 1990s were marked by a ratio of takeovers significantly higher than that of failures.

Without doubt, the 2 per cent ratio adopted dwarfs the crises of the nineteenth century: the very severe one that occurred in the mid 1870s, which reflects the close links between institutions such as Crédit Mobilier and railway companies, then in the midst of a structural crisis; or that of the 1890s, due to the international effects of the fall of Baring Brothers & Cie, to railway speculation, to the overheating of real estate and, for some institutes, to the difficulties posed by the incorporation, within their own structures, of entities taken over as a result of a crisis (Bouvier Reference Bouvier1956; Jöhr Reference Jöhr1956, pp. 161ff.; Bauer Reference Bauer1972, pp. 97ff.).

It should also be noted that, in the great majority of cases, the international entanglement of Swiss finance meant that crises originated through a combination of internal and external factors. The spectacular bloodletting that marked the years 1910–14, with the disappearance of 76 banks in five years – a peak that would not be exceeded until 1993 – was mainly explained by an increased interbank competition under the effect of the opening of the central bank – the Swiss National Bank – in 1907 (Mazbouri Reference Mazbouri2005, pp. 217–18). The spillover effects of the international financial crisis of 1907 seem secondary to this consolidation period (Purchart Reference Purchart, David, Straumann and Teuscher2015). In 1920–3, 16 banks per year were liquidated or taken over, as a result of the major restructuring crisis affecting the Swiss economy. In addition to difficulties related to the recession affecting various economic sectors, banks were shaken by the losses suffered on foreign assets, with the collapse of some foreign currencies in the post-war period (Guex Reference Guex, Cassis and Tanner1993). However, both phases of high banking mortality of 1931–4 and 1970–8 were primarily caused by international factors. During the former, these factors were the German financial crisis of 1931 and the freezing of the assets of Swiss banks in the countries concerned by transfer restrictions, and for the latter, they were the end of the Bretton Woods era and the exchange rate losses they caused (on the early 1970s’ instability, see Schenk Reference Schenk2017). The last phase of strong instability identified in the banking sector, that of the 1990s, occurred under the combined and successive effects of two phenomena. Initially, a serious real estate crisis, combined with stronger competition resulting from the abandonment of cartel practices, inflicted heavy losses on the banking sector, particularly cantonal and regional banks (Eidgenössische Bankenkommission 1998, p. 14; Birchler Reference Birchler and Abegg2007). The collapse in October 1991 of the Spar + Leihkasse Thun, which, in the absence of a deposit insurance scheme, gave rise to gatherings of panicked small savers outside the closed doors of the headquarters of this important regional bank, is emblematic of this crisis (Hüpkes Reference Hüpkes and Mayes2004; Hablützel Reference Hablützel2010, pp. 56–9; Gava Reference Gava2014, pp. 193–9; Schipke Reference Schipke2015, pp. 52–3). The mortgage crisis of the early 1990s also had a larger economic impact, with firm bankruptcy rates reaching almost unprecedented high levels (1.3 per cent in 1993) (Cosandey Reference Cosandey2002, p. 355). As for the numerous occurrences of bank disappearances in Switzerland at the end of the 1990s, these were in fact repercussions from the Asian financial crisis in Switzerland: about 20 subsidiaries and branches of Japanese and Korean banks were liquidated between 1997 and 1999. As their presence in Zurich served as a bridgehead in various business niches but involved few local commercial connections, the withdrawal of the Far Eastern banks, decided on by their parent companies for questions of strategy and profitability, had only limited consequences in Switzerland (Eidgenössische Bankenkommission 1998, p. 14).

Table 1 summarises the main information provided by our data, which makes it possible to characterise and articulate the six phases of crises identified.

Table 1. Summary of the six phases of bank failures and takeovers in Switzerland, 1850–2000

However, it would be dangerous to overinterpret our figures on the exits from the banking population in an international perspective. Is the maximum ratio of bank disappearances indicated by our data, i.e. 6.8 per cent of banks (36 out of 529) for 1993, high or low in international comparison? First, it should be noted that there is a very limited amount of historical research that can provide points of comparison in the form of a bank mortality coefficient. Recent advances in banking demography in England, a new series on the importance of the banking crisis of the 1930s in France, or research on Italian bank failures during the interwar period, do not offer an equivalent index (Garnett et al. Reference Garnett, Mollan and Bentley2015; Bond Reference Bond, Hollow, Akinbami and Michie2016; Molteni Reference Molteni2020; Baubeau et al. Reference Baubeau, Monnet, Riva and Ungaro2021). Second, even if such ratios were estimated for other national configurations, it would be risky to place them in parallel with our data. Indeed, the particularities of expansion and entry requirements of each financial centre make comparisons difficult: we think in particular of the large variations in the definition of what constitutes a bank, or the legal restrictions on branch banking, as they exist in the United States, for example, between 1864 and 1994 (Carlson and Mitchener Reference Carlson and Mitchener2006). Despite these limitations, our new estimates of banking mortality in Switzerland remain of significant value in identifying internal phases of instability and interpreting them from a global perspective.

A significant restriction to the banking demographics approach lies in the fact that counting and analysing the number of bank failures and takeovers does not provide an indication of the relevance or the systemic importance of the disappearing banks. In order to bridge this gap, we constructed a weighted measure of bank demography. We collected the last available assets reported in the Swiss National Bank's publications for each individual disappearing bank between 1935 and 2000. Reliable data are lacking for the earlier period under consideration, 1850–1934. We then related the size of the failing or taken-over bank, measured by its assets, to the overall size of the market, measured as the total assets of banks in Switzerland. We compared the outgoing banks’ assets with the overall assets of the year following the exit of the bank.

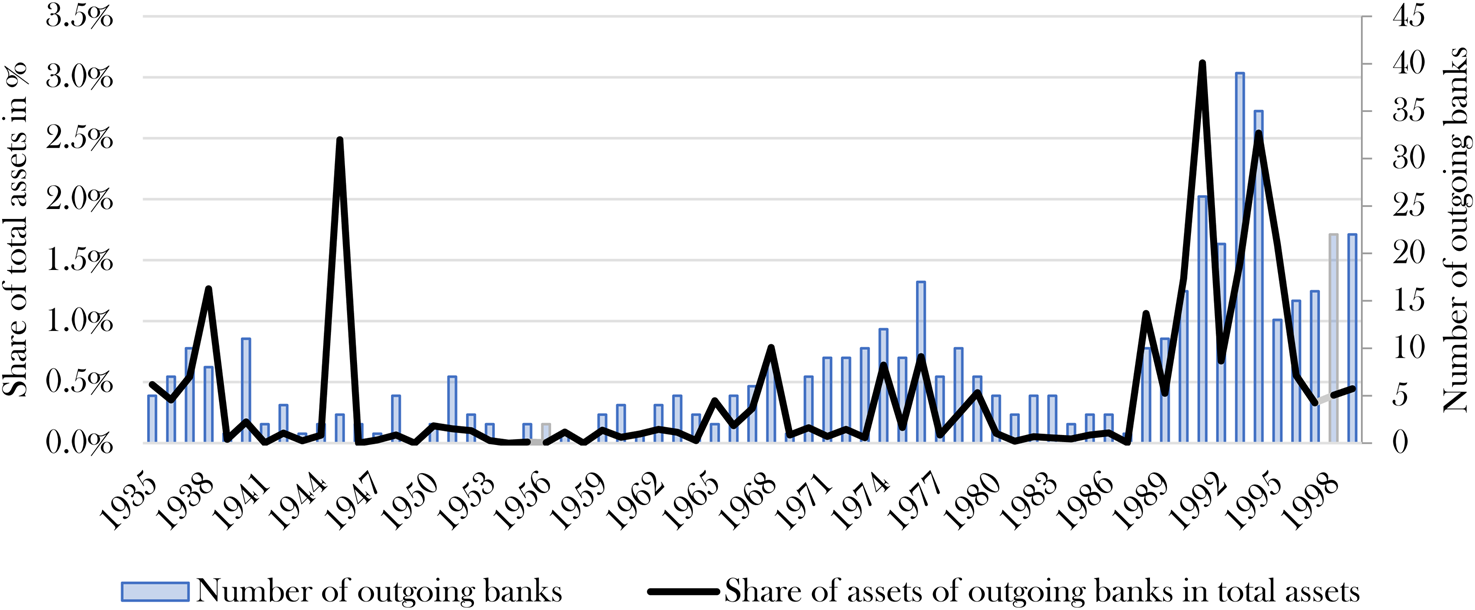

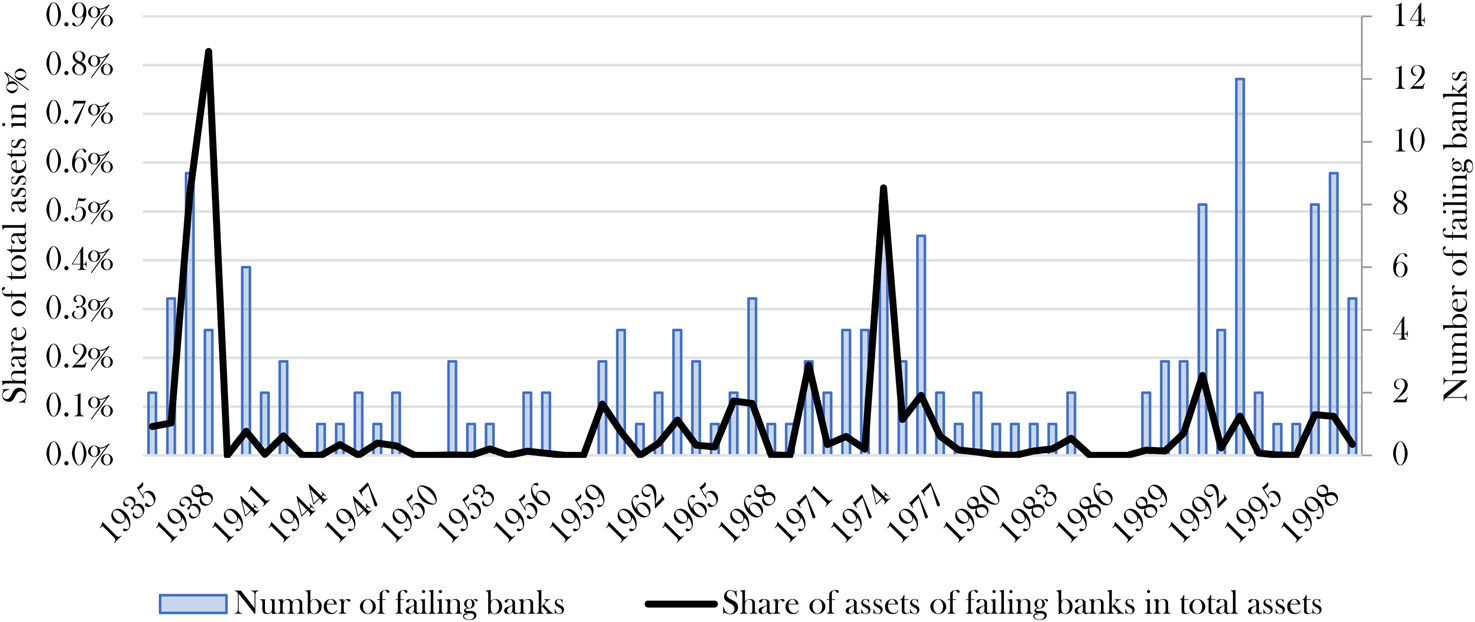

Figure 3 shows both the number of outgoing banks from the statistics (right axis) and the share of the same banks’ assets reported to the total banks’ assets. In Figure 4, we present the same data as in Figure 3 but only related to bank failures, thus excluding bank takeovers. Both visualisations, with respect to the shorter periodisation taken into account (1935–99), confirm the identification of the crisis phases highlighted in Figures 1 and 2. The severe financial crisis of the 1930s is actually visible on a longer time span. A first spike appears in 1938 caused by the liquidation of the Finanzierungsaktiengesellschaft in Glarus, an affiliate of the large bank Schweizerische Volksbank used to write off its bad foreign assets. In Figure 3, there is a second peak in 1945 (2.5 per cent of outgoing assets), which displays the takeovers of the Basler Handelsbank and of the Eidgenössische Bank by two major players in the banking system, SBC and UBS respectively. These takeovers are mainly due to the difficulties inherited from the crisis of the 1930s, and are therefore to be considered as a delayed consequence of the latter.

Figure 3. Assets of outgoing banks (failures and takeovers) as share of total assets of banks in Switzerland, 1935–99

Sources: see Figure 1. Assets of the outgoing banks (1934–99): Schweizerische Nationalbank. Total assets of Swiss banks: Wermelinger and Rosenfellner Reference Wermelinger and Rosenfellner2009, pp. 24–5. Balance sheet total (all banks and branches of foreign banks, excluding private bankers)). Note: in 1956, the planned liquidation of the Eidgenössische Darlehenskasse – a government-funded loan granting institution – was excluded from the count. In 1998, the mega-merger of UBS and SBC to form UBS AG was also excluded, because its inclusion, increasing the share of outgoing assets to over 18 per cent, would have made the graph difficult to read for the rest of the period.

Figure 4. Assets of failing banks (failures only) as share of total assets of banks in Switzerland, 1935–99

Sources: see Figure 3.

The second phase of turmoil partly overlaps with the one already mentioned in the 1970s, but has certain distinctive features. In Figure 3, the 1968 peak (outgoing assets = 0.8 per cent of total balance sheets) is a result of the internal expansion and consolidation in the domestic market of one large bank that amalgamated three local institutions that were already affiliated to it. For the following decade, however, it is interesting to compare the two graphs. It is noteworthy that the total number of exits is mainly due to the high number of failures and liquidations (as opposed to takeovers) that occurred during this period. Most of the institutions concerned are in fact banks of foreign origin (United California Bank, Banque de Crédit International, Amincor-Bank, Finabank, Weisscredit), whose reputation and/or business have been compromised, particularly as a result of the difficulties arising from the end of Bretton Woods, and whose senior managers were also facing legal action for fraudulent conduct (Schmid Reference Schmid1980, pp. 30–5, 131–3, 154–6). The fact that the difficulties of these institutions eventually led to their bankruptcy suggests that the Swiss banking community let them disappear without attempting takeovers because of high economic, legal and reputational risks.

The scenario unfolded quite differently in the 1990s crisis. This phase was marked by a strong concentration trend and a consolidation of the banking system. On the one hand, the difficulties of the regional banking fabric, partly fuelled by a real estate crisis, and, on the other, international mergers and acquisitions resulted in a significant number of exits from the statistics. Figures 3 and 4 show that this phenomenon was mainly reflected in takeovers. Apart from the Spar- und Leihkasse Thun (1991), the rare failures (30 failures vs 120 takeovers between 1990 and 1995) mainly concern branches of international groups established in Switzerland or small local establishments, whose takeover seemed of little interest to the major players in the system. In Figure 4, the small size of the failing banks is expressed by the wide discrepancy between the share of assets and the number of banks reported during the period. It should also be noted that the 1990s crisis strongly affected some cantonal banks that were restructured, taken over or privatised following severe difficulties.Footnote 4

Analysing a weighted measure of the banking demography approach, as in Figure 3, thus suggests that the 1930s and 1990s crises affect institutions of a comparatively larger size. Our analysis shows that in the 1930s the large banks were mainly responsible for outgoing assets, while in the 1990s it was the cantonal banks. This confirms the centrality of these institutions in the Swiss banking architecture.

We use eight categories of banks based on the classification employed by F. Ritzmann. Like any classification, this taxonomy poses certain methodological difficulties, since both the categories and the economic realities to which they correspond have evolved over time (Wermelinger and Rosenfellner Reference Wermelinger and Rosenfellner2009, pp. 12–13). Nevertheless, such a typology makes it possible to better understand which groups of banks are affected by high mortality.

Breaking down the statistical series on banking mortality according to the categories of banks, it appears that a very large majority of occurrences of failures or takeovers concern smaller institutions, mainly classified in the groups of local banks, mortgage banks and savings banks (37 per cent over the whole period) and in the very heterogeneous group of the ‘other banks’ (43 per cent over the whole period), which in fact is mainly made up of foreign banks in the second half of the twentieth century.

Figure 5 shows the chronological evolution, by decades and by total number of occurrences, of the categories of banks that were affected by a failure or takeover. Savings banks, local banks and mortgage banks – three categories that make up the fabric of small and medium-made regional institutes – were the main victims of failure and takeover phenomena during the second half of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth century. The appearance and development of institutions classified as ‘other banks’, first during the 1920s, then in a greater way during the second half of the twentieth century, drove them to become the most unstable category of banks. These were mainly foreign-owned banks. The political and monetary authorities, as well as their competitors already in place, sought to curb their expansion in Switzerland (Giddey Reference Giddey and Aspey2013). Their alleged greater fragility, and what were perceived as commercial practices not appropriate to Swiss practice, together with sensational media reporting on the advantages of banking secrecy, then served as arguments to impose stricter regulatory requirements on the foreign banks.

Figure 5. Bank failures and takeovers, 1850–2000, broken down by type of bank

Sources: see Figure 1.

It is also of relevance to focus our attention on the category of foreign banks, because of their growing importance in the Swiss banking fabric from the second half of the twentieth century and their role in the international entanglement of Swiss finance. It was not until 1972, following the revision of the Banking Act in 1971, that the SNB's official statistics created a new category of ‘foreign-owned banks’. The period from the 1960s to the 1990s was marked by a tremendous growth of foreign financial institutions in Switzerland, both in terms of numbers and of market share. Between 1969 and 1990, the number of foreign banking subsidiaries grew from 76 to 126, while the number of non-public finance companies grew from 19 to 103 between 1972 and 1990 (Helbling Reference Helbling, Blattner, Genberg and Swoboda1993, pp. 194–5). The market share in foreign assets and fiduciary accounts of foreign banks increased from 16 per cent in 1972 to 25 per cent in 1990.

Figure 6 shows that the period from the 1970s to the 1990s was characterised by both numerous arrivals of new foreign banks and the disappearance of foreign institutions. Between 1972 and 2000, 94 foreign banks were removed from the list of banks, including 37 failures and 57 takeovers. These banks were significantly younger, since they left the Swiss financial centre after 22 years on average (compared to 50 years for all the banks in our database). They were hugely concentrated in financial centres, predominantly in Geneva and Zurich (80 out of 94).

Figure 6. Evolution of foreign banks admitted and excluded in Switzerland, 1972–2000

Sources: Schweizerische Nationalbank categories 5.20 (ausländisch beherrschte Banken) and 7.00 (Filialen ausländischer Banken), Neuaufnahmen von Instituten, without taking into account the changes of categories.

What is even more noteworthy in the compiled statistical series – and results from the methodology adopted – is the absence of the two categories of banks that have dominated the Swiss financial centre since the beginning of the twentieth century: the cantonal banks – semi-public institutes, generally close to the political authorities of their cantonal state – and the large commercial banks. The former appear only twice (the liquidation of the Banque Cantonale du Valais in 1870 and the takeover by UBS of the Appenzell-Ausserrhodische Kantonalbank in 1996),Footnote 5 while the latter have been thus affected only four times (in addition to the two cases of 1945 mentioned above, the liquidation of the Banque Générale Suisse in Geneva in 1869 (Jöhr Reference Jöhr1915, pp. 152–68), and that of the Comptoir d'Escompte Suisse in 1934). In other words, the vast majority of cases identified in our failures and takeovers statistical series involve institutions of regional or local importance. This also explains why the serious crisis of the 1930s, although rightly recognised as a decisive crisis phase in the literature (Halbeisen Reference Halbeisen, Pohl, Tortella and van der Wee2001), does not appear as obvious in our data: the bailout interventions (Schweizerische Volksbank in 1933) and the important restructuring measures (share buybacks and capital reduction at UBS in 1933 and 1936) have often made it possible to avoid the collapse of first-rate establishments (Baumann Reference Baumann2007). In addition, the special status of the cantonal banks – which are traditionally funded, organised and regulated by cantonal authorities and cantonal laws and benefit from a state guarantee – often favours rescue operations of a political nature, without which several of these institutes would probably have collapsed, such as the exemplary and not isolated case of the Neuchâtel Cantonal Bank in the interwar period (Perrenoud Reference Perrenoud, Cassis and Tanner1993; on the early history of cantonal banks, see Guex Reference Guex and Fontaine1997; Froidevaux Reference Froidevaux, Kuijlaars, Prudon and Visser2000).

This absence of the dominant players, more than being a sign of their solidity (Mazbouri Reference Mazbouri and Lescure2016), also attests to the historical reality of the idea of too big (or too political) to fail, well before the recent imbalances of 2008. The larger a bank, the greater the likelihood of external intervention to prevent the spread of a crisis. In contrast, moreover, it is also very noteworthy that the cantonal banks and the large commercial banks are the banks that are the most active in takeovers. In 21 per cent of cases for the former and 27 per cent for the latter, over the entire period envisaged, they are the ones who absorbed the establishments that were the subject of a buyout. They therefore play a role in both stabilising the banking market and continuing to expand regionally or nationally through these acquisitions.

IV

At the end of this research, which we hope will stimulate other research on the analysis of banking crises, what can we learn from the contributions of our essay on banking demography? Let us first point out that our census of failures and takeovers makes it possible to identify a periodisation punctuated by six phases of excess banking mortality (1882–91, 1910–14, 1920–2, 1934–40, 1970–8 and 1990–9). Certain trends, already known or identified internationally, such as the remarkable stability of the phase of ‘financial repression’ that extended from the end of World War II to the break-up of the Bretton Woods system, are confirmed. On the other hand, our study shows more clearly the vigour of certain phases of crises that are still little studied by historical research, such as the period of 1910–14. The detailed data have given us the following sketch of the failing bank: aged on average about 50 years, it was more often (63 per cent) located outside the main financial centres of the country and belonged mainly to the groups of local banks, savings banks and mortgage banks (37 per cent), or to the very heterogeneous group of ‘other’ banks (43 per cent). These indications invite researchers to look more closely at the regional or cantonal level in order to understand the reactions and responses to the phenomena of bank disappearances; the canton – as opposed to the federal or national level – remains the most relevant political and media space for a long part of the period studied.

These few elements, which should be put into an international perspective, ultimately confirm the claim that Swiss banking structures are particularly stable needs to be revisited. This stereotypical image, forged during the (short) period when, like the picture of other financial centres, the Swiss banking architecture seems to have escaped the crisis, certainly reflects what contemporaries of this ‘golden age’ (Cassis Reference Cassis2010, pp. 232–5) of the 1950s and 1960s could perceive to be the fundamentals of a financial centre that was then emerging as a world-class giant of the banking sector. This prism, however, is clearly out of step with what previous generations experienced at the local, cantonal or national level of the life of Swiss banking institutions, and what subsequent generations, to which the two authors of this article belong, would experience in their turn (on the role of memory in financial crises, see Cassis and Schenk Reference Cassis and Schenk2021). The evolution of literature which, at the beginning of the twentieth century, developed a perspective of analysis strongly integrating the question of crises into a reassuring narrative insisting more and more, especially after World War II, that banking structures had great stability, is significant in this respect. This evolution in tone and content, sometimes perceptible in the title of the work itself, is substantial; compare, for example, the vitriolic portraits drawn up by some authors (Jöhr Reference Jöhr1915; Landmann Reference Landmann1916; Wetter Reference Wetter1918) and the sometimes apologetic paintings by others (Kurz and Bachmann Reference Kurz and Bachmann1928; Schweizer, Ackermann and Viret Reference Schweizer, Ackermann and Viret1940; Hess Reference Hess1963; Iklé Reference Iklé1972; Emmenegger Reference Emmenegger1992). Inconsistent with reporting on the actual turbulent history of banking structures in Switzerland, this golden legend, including other clichés dating from the same period (that of the Gnomes of Zurich, for example (Iklé Reference Iklé1972, pp. 1–2; Guex and Haver Reference Guex, Haver, Hache-Bissette, Boully and Chenille2007)) is still widespread today. In a way, it is part of the business card, the projected identity of this international banking centre, despite the crisis situations that the Swiss financial centre has gone through throughout its history.

Certainly, compared to the financial and banking history of other countries, especially that of its immediate neighbours, Switzerland's banking and financial history could be compared to that of a long, quiet river. It is also true that, despite the late appearance of a central bank, opened only in 1907, certain organisational elements (in particular related to the highly corporatist and cartel functioning of the sector), structural elements (in particular related to the polycentrism of the Swiss financial sector), institutional elements (in particular related to federalism and the Swiss political system) and ideologies (notably, a social and political consensus in favour of banks as early as the 1930s) probably contributed to equipping this banking and financial centre with a particular capacity for resilience to crises. It should also be noted that, in the case of Switzerland, the banking model combining universal banking activities with an early specialisation in wealth management (private banking) played a strong stabilising role during crises (Mazbouri et al. Reference Mazbouri, Guex, Lopez, Halbeisen, Müller and Veyrassat2012, pp. 476–8; Guex and Mazbouri Reference Guex, Mazbouri, Fraboulet, Margairaz and Vernus2016; Mazbouri Reference Mazbouri and Lescure2016). This is suggested, among other things, by the lack of destabilising effects produced not only by the crises but also by the scandals that have regularly tainted the history of Swiss banking. In conclusion, we may even venture the hypothesis that in this field, the management of banking crises is like that of financial scandals, with the same factors explaining, in part, that both produce effects that are ultimately limited, to the point where they tend to quickly fade from memory but also, which is perhaps even more significant, from the reference horizon of researchers. Until the next crisis?