The prevalence of self-harm, defined as any intentional self-poisoning or self-injury regardless of the degree of suicidal intent, Reference Hawton, Harriss and Zahl1 and the high rate of repetition and eventual suicide Reference Hawton, Zahl and Weatherall2,Reference Owens, Horrocks and House3 make self-harm a major healthcare problem in many parts of the world. Reference Claassen, Trivedi, Shimizu, Stewart, Larkin and Litovitz4–Reference Schmidtke, Bille Brahe, De Leo, Kerkhof, Bjerke, Crepet, Haring, Hawton, Lönnqvist, Michel, Pommereau, Querejeta, Phillipe, Salander Renberg, Temesvary, Wasserman, Fricke, Weinacker and Sampaio Faria6 Despite widespread variation in services and the general trend towards greater inclusion of consumer views in the evaluation of health service outcomes, Reference Eagar7–Reference Coulter and Ellins9 there appears to have been little attempt to draw together the available evidence on people's perceptions of self-harm services. Assembling such information is important in the design and successful implementation of better quality care. 10

We have conducted a systematic review of the international literature on people's attitudes to and satisfaction with health services (specifically medical management, in-hospital psychiatric management and post-discharge management) following self-harm in order to inform the development of improved services.

Method

We sought to identify all relevant qualitative and quantitative studies of participants of either gender or any age who had engaged in self-poisoning or self-injury and had contact with hospital services. We also included studies of patients' friends or relatives. Electronic databases (EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, AMED, British Nursing Index, CINAHL, Global Health, HMIC, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, Sociofile and SIGLE) were searched for any relevant international literature published until June 2006. Search terms relevant to the experiences of care of individuals who self-harm were those used in the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health 10 report on self-harm (see online supplement). Reference lists of relevant studies were also searched. There were no language restrictions. Experts in the field working in non-English speaking countries were consulted in order to determine whether they knew of any published or unpublished literature concerning attitudes to services among those who self-harm.

Research based on quantitative methods was used to provide evidence about the general experiences of a larger population of people who self-harm, with findings from qualitative studies used to extend understanding through the recounting of specific examples and incidents. Data were extracted independently by two reviewers. For studies using qualitative methodology, quotations and themes regarding attitudes and experiences of services were coded using a pen and paper method by a single reviewer (T.T.). The second reviewer (S.F.) extracted data to ensure all relevant quotations and topics were recorded and to reduce possible bias in reporting findings. Similarities and differences between participants' accounts were noted.

The quality of all included studies was assessed independently by at least two reviewers using a combination of the Social Care Institute for Excellence's quality assessment tool 11 and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme's ‘10 Questions to Help you Make Sense of Qualitative Research’. 12 Relevance was assessed using a dichotomous (strong or weak) rating scale. Ratings were only intended to determine relevance to the purpose of this review and do not reflect general relevance.

All studies were included in the review regardless of quality. However, in reporting the results, more weight was given to studies of stronger design. Relevance to the objectives of the review was also taken into consideration.

Included studies

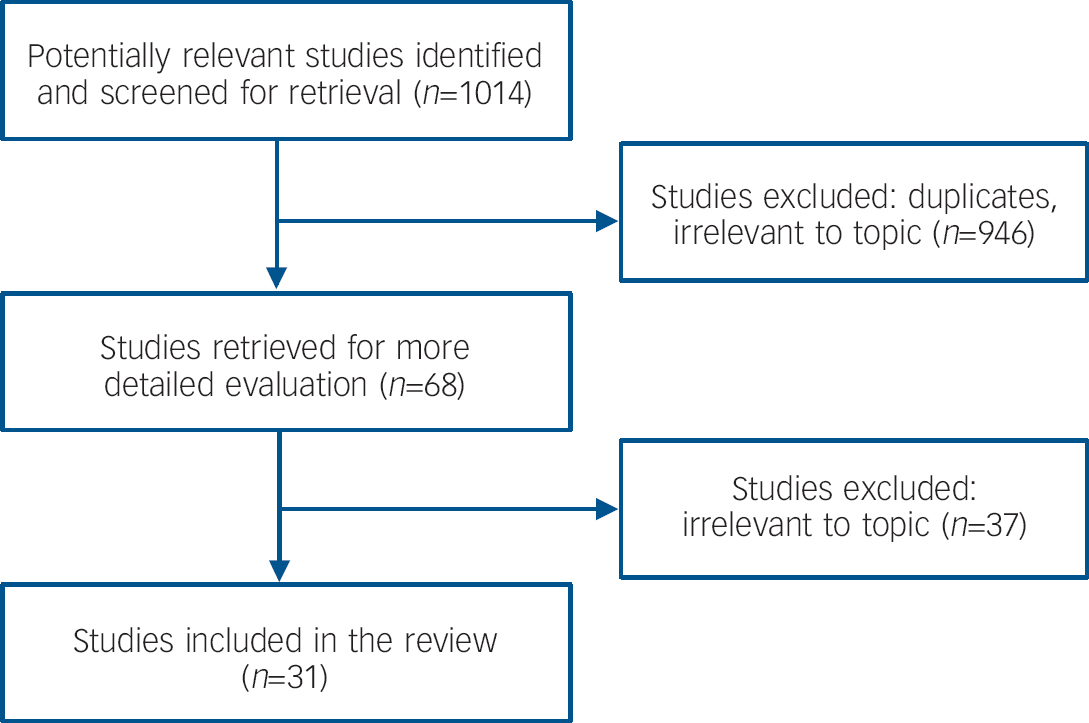

A total of 1014 potentially relevant studies were identified through electronic searches (Fig. 1). After further inspection of abstracts, 946 studies were excluded because of duplications, irrelevance to service users' experiences and study population (e.g. not all exhibited self-harm behaviour). Overall, 68 studies were retrieved for detailed evaluation of which a further 37 studies were excluded on the ground of irrelevance. Thirty-one studies met the inclusion criteria and were assessed for quality and relevance (Table 1 and online Table DS1). Fourteen studies (45%) were rated as having a ‘strong’ or ‘strong/acceptable’ design, nine (29%) as having an ‘acceptable’ design, and eight studies (26%) as having an ‘acceptable/weak or weak’ design. Sixteen studies were based upon service users' experiences in the UK. The other studies were based upon service users' experiences in North America (n=6), Sweden (n=3), New Zealand (n=2), Ireland (n=1), Australia (n=1), Finland (n=1) and The Netherlands (n=1). In spite of an international literature search, no non-English studies were found. Service users who had self-poisoned accounted for the majority of participants in 15 studies. This reflects the fact that most individuals who self-harm and present to hospital do so after a self-poisoning episode. Reference Hawton, Harriss and Zahl1,Reference Schmidtke, Bille Brahe, De Leo, Kerkhof, Bjerke, Crepet, Haring, Hawton, Lönnqvist, Michel, Pommereau, Querejeta, Phillipe, Salander Renberg, Temesvary, Wasserman, Fricke, Weinacker and Sampaio Faria6

Fig. 1 Study flow chart.

Table 1 Quality assessment and relevance ratings of included studies

| Study (country) | Quality assessment | Relevance to review |

|---|---|---|

| Arnold, 1995 (UK) Reference Arnold24 | Acceptable/weak | Strong |

| Bolger et al, 2004 (Ireland) Reference Bolger, O'Connor, Malone and Fitzpatrick31, a | Strong | Weak |

| Brophy, 2006 (UK) Reference Brophy23 | Acceptable/weak | Strong |

| Burgess et al, 1998 (UK) Reference Burgess, Hawton and Loveday38, a , b | Strong | Strong |

| Bywaters & Rolfe, 2002 (UK) Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33 | Acceptable/weak | Strong |

| Cardell & Pitula, 1999 (North America) Reference Cardell and Pitula43 | Weak | Strong |

| Carrigan, 1994 (UK) Reference Carrigan19, a | Acceptable | Strong |

| Cerel et al, 2006 (North America) Reference Cerel, Currier and Cooper25, a | Acceptable | Strong |

| Crockwell & Burford, 1995 (North America) Reference Crockwell and Burford32, a | Acceptable | Strong |

| Dorer et al, 1999 (UK) Reference Dorer, Feehan, Vostanis and Winkley40, a | Acceptable | Weak |

| Dower et al, 2000 (Australia) Reference Dower, Donald, Kelly and Raphael35, a | Strong | Strong |

| Dunleavey, 1992 (UK) Reference Dunleavey36, a | Acceptable | Strong |

| Harris, 2000 (UK) Reference Harris22 | Strong/acceptable | Strong |

| Hengeveld et al, 1988 (The Netherlands) Reference Hengeveld, Kerkhof and van der Wal29 | Strong | Strong |

| Hood, 2006 (New Zealand) Reference Hood39, a | Strong | Strong |

| Horrocks et al, 2005 (UK) Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14, a | Strong | Strong |

| Hume & Platt, 2007 (UK) Reference Hume and Platt30, a | Strong | Strong |

| Kreitman & Chowdhury, 1973 (UK) Reference Kreitman and Chowdhury44 | Strong/acceptable | Strong |

| Nada-Raja et al, 2003 (New Zealand) Reference Nada-Raja, Morrison and Skegg21, a | Strong | Weak |

| National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2004 (UK) 10 | Acceptable | Strong |

| Palmer et al, 2006 (UK) Reference Palmer, Strevens and Blackwell26 | Acceptable | Strong |

| Perseius et al, 2003 (Sweden) Reference Perseius, Öjehagen, Ekdahl, Åsberg and Samuelsson34 | Weak | Strong |

| Pitula & Cardell, 1996 (North America) Reference Pitula and Cardell42 | Weak | Strong |

| Rotheram-Borus et al, 1999 (North America) Reference Rotheram-Borus, Piacentini, Van Rossen, Graae, Cantwell, Castro-Blanco and Feldman13, a , b | Acceptable | Weak |

| Smith, 2002 (UK) Reference Smith41 | Acceptable/weak | Weak |

| Suominen et al, 2004 (Finland) Reference Suominen, Isometsä, Henriksson, Ostamo and Lönnqvist16, a , b | Strong | Strong |

| Treloar & Pinfold, 1993 (UK) Reference Treloar and Pinfold15 | Strong | Strong |

| Warm et al, 2002 (North America) Reference Warm, Murray and Fox37 | Weak | Strong |

| Whitehead, 2002 (UK) Reference Whitehead17 | Acceptable | Strong |

| Wiklander et al, 2003 (Sweden) Reference Wiklander, Samuelsson and Asberg18 | Strong | Strong |

| Wolk-Wasserman, 1985 (Sweden) Reference Wolk-Wasserman20 | Strong | Strong |

a. Denotes majority self-poisoned

b. Denotes quantitative study

Results

General perceptions of management

Treatment received in hospital and satisfaction with that treatment varied greatly among study participants. However, many participants from different countries and health systems recounted similar hospital experiences. Patient involvement in treatment and treatment administration decisions was one of the most important aspects of hospital care for many participants. Provision of information led to improved outcomes. Reference Rotheram-Borus, Piacentini, Van Rossen, Graae, Cantwell, Castro-Blanco and Feldman13 Service users appreciated when ‘they [staff] tried to tell me what they could’ and ‘they explained everything that they were doing’ (p. 13). Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14 However, some participants reported that they were provided with very little information about their care and others said treatment was administered without explanation. Reference Treloar and Pinfold15–Reference Whitehead17 Clarity of communication appeared to be just as important, as several participants described an inability to understand the information staff gave them. Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14,Reference Wiklander, Samuelsson and Asberg18

Although some service users in studies from the UK 10,Reference Carrigan19 and Sweden (p. 568) Reference Wolk-Wasserman20 thought staff were ‘awfully competent’ and ‘well trained’, they also felt that staff often lacked knowledge about self-harm, which participants perceived as contributing to their negative attitudes about people who self-harm. When individuals felt staff did not know about or understand self-harm they were more likely to be perceived as operating on misconceptions about why people self-harm. 10,Reference Carrigan19 Participants also called for sensitivity to possible personal preferences such as the gender of staff providing treatment.

Accident and emergency department

Although 62% of adolescent patients in New Zealand reported a positive experience in one study, Reference Nada-Raja, Morrison and Skegg21 some service users in the UK felt that they were treated differently from other patients in accident and emergency (A&E: the term used by participants in the majority of studies) departments and attributed this to the fact that they had harmed themselves: Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14,Reference Harris22

‘They wouldn't touch me… they looked at me as if to say “I'm not touching you in case you flip on me”… they didn't actually say it, it was their attitude…’ (p. 12) Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14

Many service users interviewed complained that A&E staff were unconcerned with their mental health and concentrated entirely on their physical problems.

‘On the occasions I have been admitted to an A&E department they have concentrated on medically patching me up and getting me out. Never have I been asked any questions regarding whether this is the first time I have self-harmed or if I was to do it again or how I intend to deal with it.’ (p. 50) Reference Brophy23

Waiting room

Wait times were perceived to be too long by many participants. 10,Reference Arnold24,Reference Cerel, Currier and Cooper25 Long waiting times coupled with a lack of information about their physical status made some service users anxious and frightened. Reference Cerel, Currier and Cooper25 Positive experiences were associated with being updated and provided with ‘regular check-ups’ while waiting (p. 16). Reference Palmer, Strevens and Blackwell26

‘All they have to say is, we're here if you need us, don't think you're on your own…’ (p. 9). Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14

Some service users also complained that waiting with an often large number of people increased their inability to soothe themselves after a self-harm episode. Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14 However, service user reactions to being placed in a separate waiting room were mixed.

Physical treatment

Service users' negative perceptions of interactions with staff centred upon perceived inappropriate behaviours and lack of sympathy (this is the term used by participants and is probably congruent with the term ‘empathy’ used by clinicians). Perceived threats and humiliation were common reasons for negative experiences of physical management. 10

‘The last time I had a blood transfusion the consultant said that I was wasting blood that was meant for patients after they'd had operations or accident victims. He asked whether I was proud of what I'd done…’ (p. 50) Reference Brophy23

Others felt staff threatened to withhold treatment (e.g. anaesthetic during suturing) because their injuries were self-inflicted and/or unless they promised not to self-harm again. Positive experiences of physical management were associated with staff's consideration of patients' psychological situations during physical treatment.

‘He… took great pains to suture very neatly – when I commented on this he said “I don't want it to leave any scars” to which I replied that I am covered in them. He said “not on my watch”.’ (p. 18) Reference Palmer, Strevens and Blackwell26

Psychosocial assessment

Although psychosocial assessment is part of recommended care for people presenting to hospitals after a self-harm episode, 10,27 many individuals are not assessed. Reference Bennewith, Gunnell, Peters, Hawton and House8,Reference Kapur, House, Creed, Feldman, Friedman and Guthrie28 Among those who received an assessment, experiences varied. More positive experiences were described when staff involved individuals in treatment decisions and explained the reasons for and goals of the assessment.

‘The nurse consultant who assessed me was very easy to talk to. She explained everything clearly in a non-threatening way. It felt like a friendly chat. She was great!’ (p. 21) Reference Palmer, Strevens and Blackwell26

When an assessor provided individuals with ‘every opportunity to speak and talk about problems’ respondents also reported more positive experiences (p. 21). Reference Palmer, Strevens and Blackwell26 However, several participants perceived the assessment to be superficial and rushed. Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14,Reference Hengeveld, Kerkhof and van der Wal29

‘I got the impression that [the psychiatrist] wanted to get it over and done with as quickly as he could and get on with whatever it is he had to do next. There was nothing personal about it.’ (p. 16) Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14

Discharge and referral

Discharge was often described as a negative experience for service users as many felt ill-prepared to leave hospital, for either physical or psychological reasons. One participant described being ‘… out the next morning walking to the bus stop thinking “what the hell's gone on’” (p. 20). Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14 Furthermore, many were unsure of what to expect once they returned home. Several service users said they had not received referrals for after-care and although contact numbers for helping organisations were often provided, some felt uncomfortable initiating their own after-care. Reference Hume and Platt30

Many service users interviewed said that at the time of discharge they were told they would be contacted to schedule after-care. 10 However, often they heard nothing further.

‘They said they'd get me to see a psychiatrist but I haven't heard nothing from them at all you know, so it's like I've had to cope by myself and I ain't seen no psychiatrist or nothing, no counsellor… I'm still waiting to this day to hear from them, I know I should get on the phone to them but it's not my job really it's their job as well… I do feel let down in a big way, because it feels like all the information now that I've given, that they've just put it to one side and left it.’ (p. 21) Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14

Participants that did receive after-care often faced long waits for psychotherapy. 10,Reference Hume and Platt30 Half of service users in a Scottish study complained about the delay between discharge and their appointments. Reference Hume and Platt30

‘I had to wait 12 weeks. A lot can happen in 12 weeks. When the appointment came I was, like, I didn't really see the point.’ (p. 5) Reference Hume and Platt30

Some individuals interviewed were concerned about how A&E staff determine the need for after-care. 10 Overall, the feelings of many people who self-harm are best conveyed by one participant who remarked:

‘I was going back to where I started, I felt confused, I thought “what were the point of coming to hospital”.’ (p. 20) Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14

Although the majority of people were generally satisfied with their overall treatment, some service users said they would not return to hospital if they experienced another self-harm episode in the future. Reference Bolger, O'Connor, Malone and Fitzpatrick31

Post-hospitalisation management

The majority of people indicated a willingness to engage in services to help them minimise self-harm. Reference Hume and Platt30 In a Canadian study, some individuals welcomed referrals to out-patient care because they felt they received no support while in hospital. Reference Crockwell and Burford32

‘Yea, I thought that was good because I didn't like the way it was left. I wouldn't like to think that other people are just left hanging. They just sent me off, “are you fine?” “Yes, I'm fine, O.K.” and they let me go. I wouldn't have wanted to be admitted because it wouldn't have made things better but you're kind of… left hanging… He was absolutely no good to me… um… the only good thing I got out of that was the social worker so I wouldn't say I minded that my name had been given to somebody because usually if you end up in the hospital like that you're at the end of your rope so I'd think you'd be kind of grateful to get something back.’ (p. 9) Reference Crockwell and Burford32

The opportunity to talk about the issues that contributed to their self-harm episode was described by many adult service users as a positive result of after-care. Reference Crockwell and Burford32 Among adults, satisfaction was connected to perceptions of staff behaviour towards patients. Service users were more satisfied with their treatment when they felt their therapist was genuinely concerned about them, respected them and did not try to belittle them. Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33 In a study examining dialectical behavioural therapy, people were found to be satisfied with their treatment. Reference Perseius, Öjehagen, Ekdahl, Åsberg and Samuelsson34

‘It has been very, very useful, because there are lots of things that I never really talked about that happened in my past that I'd never been able to face before, and we're actually in the process of starting to work through those things, which I never thought I'd be able to do.’ (p. 30) Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33

Participants who did not attend after-care appointments gave a variety of reasons for their non-adherence. Some participants cited difficulty in understanding referral instructions as a reason for not attending appointments. Reference Dower, Donald, Kelly and Raphael35 Several did not believe therapy would be beneficial Reference Hume and Platt30 and others feared the stigma of seeing a therapist. Reference Dunleavey36

‘I hated it. Couldn't stand the psychiatrist… just thought “I must be crazy”, that's all that came into my head. That's what I thought, “if you see one of them, you're crazy”.’ (p. 10) Reference Crockwell and Burford32

One UK study found that individuals unwilling to use after-care services were more likely to have a history of repeated self-harm or feel that they were ‘beyond help’ (p. 4). Reference Hume and Platt30

Service users who ended treatment early cited difficulties with therapists (e.g. feeling uncomfortable with the therapist) or feeling uncomfortable with the location of the sessions, that the sessions did not help or that they had got all they could out of therapy. Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33,Reference Dower, Donald, Kelly and Raphael35,Reference Warm, Murray and Fox37 Respondents' perceptions of staff were important to their engagement with care. Crockwell & Burford found that Canadian service users they interviewed placed a lot of responsibility upon professionals, expecting their clinician to ‘fix them’. Reference Crockwell and Burford32 Therefore, the relationship between client and clinician was an important measure of the quality of care.

Although many service users said after-care had helped them, some individuals had negative reactions to their therapists. Several respondents in an American study complained that their psychiatrist did not help them. One participant described a psychiatrist as ‘cold, clinical, [and] impersonal’ (p. 18). Reference Arnold24 Some respondents in a Canadian study said they thought their after-care appointments did not last long enough.

‘… when I left he gave me a prescription for antidepressants so we hadn't talked, he didn't once say “it's O.K.” or give me any bit of feedback. He just wrote me out a prescription. I'd say I was only in there about 15 min, 20 at the most, and he wrote me out a prescription for antidepressants and sent me on my way.’ (p. 9) Reference Crockwell and Burford32

Although service users who completed post-hospital treatment said that the ability to talk to someone about their problems was a valuable aspect of care, many service users in studies from the UK Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33 and Australia Reference Dower, Donald, Kelly and Raphael35 found opening up difficult and anxiety-provoking. Several service users found it difficult to open up to someone they did not know. Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33 Others were frightened that discussing their problems would intensify their distress by bringing back repressed memories.

‘… they want to know about my past, and the more I talk about it, the more the flashbacks come back, and the more I cut into my arms. It felt like the counselling was making the self-harm worse, because they want to know every niggly detail to get a full picture. I don't want to go through that again. I've been through it once. I don't need to go through it twice.’ (p. 31) Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33

Adolescents

Adolescents were more positive about after-care. Most welcomed the opportunity to talk. Reference Bolger, O'Connor, Malone and Fitzpatrick31,Reference Burgess, Hawton and Loveday38–Reference Dorer, Feehan, Vostanis and Winkley40 Both adolescents and their parents appreciated ‘talking to someone on the outside’ with whom the family had ‘no emotional attachment’ (p. 84). Reference Hood39 However, not all were as positive.

‘I've talked and stuff and I still don't really feel a hell of a lot better…’ Cause, you know, sometimes even just talking about it doesn't really help, sometimes just a hug or something would be cool, more helpful than sitting here talking about it… the talking and things didn't really help me too much. I don't feel that it changes anything… It just seems to scare a person, that's about it.' (p. 85) Reference Hood39

The success of family involvement in therapy or aspects of the treatment approach was often dependent on the relationship between the adolescent and his or her family. Adolescents acknowledged that having a therapist to mediate the discussion allowed them to talk to their parents about issues they found difficult to bring up on their own.

‘… it is helpful because there's some stuff you can't really talk about or just having the psychologist there, like having someone else there, there's some stuff that I could talk to my mum about that I couldn't talk to her one on one.’ (p. ) Reference Hood39

However, not all adolescents welcomed family therapy. This was because the presence of parents ‘inhibits me from fully unleashing’ or because they did not want to disclose information to their parents (p. ). Reference Hood39

‘I wanted to be more by myself because there were things I couldn't say in front of my parents… I just wouldn't be able to say that whole thing because I didn't want my parents to know or something.’ (p. ) Reference Hood39

Family therapy also caused some adolescents' anxiety to rise when divorced or separated parents and family members were in attendance. These adolescents found it difficult to participate while worrying about family tensions, although these would often be common goals or material for therapy.

Psychiatric hospitalisation

Generally, individuals admitted to in-patient care discussed feeling a lack of control. Several individuals in the UK who received in-patient care felt that they were merely being watched and did not receive any sort of therapy for their self-harm. Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33 Others viewed hospitalisation as a punishment. Several respondents said that staff confiscated any object that could be used to self-harm, which increased their feelings of a lack of control and contributed to the desire to self-harm again. Reference Brophy23,Reference Smith41 In order to counteract this feeling, some suggested that staff give individuals more responsibility for preventing their self-harm. Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33

Participants placed under constant observation while on ward had positive experiences when staff kept them occupied and engaged. Reference Pitula and Cardell42,Reference Cardell and Pitula43 However, the lack of privacy was an important issue and limited the perceived effectiveness of this form of management.

Service improvement

The majority of studies included respondents' suggestions for improving services for individuals after a self-harm episode which spanned all stages of care. Five key areas for service improvement emerged.

Increased and improved communication between service staff and those who self-harm

The majority of people called for some responsibility in deciding their care. Treating individuals with respect, allowing them to participate in treatment decisions and keeping them informed of their status was very important to those interviewed in studies in the UK, Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33 the USA Reference Rotheram-Borus, Piacentini, Van Rossen, Graae, Cantwell, Castro-Blanco and Feldman13 and Australia. Reference Dower, Donald, Kelly and Raphael35

Greater staff knowledge of self-harm and how to deal with people after a self-harm episode

Some service users acknowledged that better information and specific training on how to deal with people who self-harm might increase professionals' understanding and interactions with them. It was important that nurses were ‘more aware that there's a certain way to deal with people who self-harm, it's not enough to just be a good nurse’ (p. 11). Reference Horrocks, Hughes, Martin, House and Owens14

Increased sympathy towards those who self-harm

Many service users felt that people who did not self-harm could not truly understand their experiences. Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33 Participants explained that they did not always want understanding but wanted to be listened to and not judged. They hoped that staff would ‘… listen and respond in a natural way – showing concern and wanting to support you’ (p. 69). Reference Brophy23

Improved access to local services and after-care

The need for more mental health professionals working in hospitals and local facilities to decrease waiting times was highlighted by respondents. Many study participants were unaware of local services that provide support to individuals who self-harm. Reference Kreitman and Chowdhury44 They often urged professionals to provide people with more information about local formal support services and how to contact them. Reference Brophy23,Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33

‘Having arrived at A&E late at night, I had to wait until early the following morning before seeing a psychiatrist.’ (p. 21) Reference Palmer, Strevens and Blackwell26

Participants felt it was essential that services be as accessible as possible by being staffed 24 h a day and providing walk-in services. Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33 It was also suggested that services offer alternatives to hospital such as having nurses who can treat self-inflicted wounds working in the community. Reference Brophy23,Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33

Provision of better information about self-harm for patients, carers and the general public

Individuals who self-harm do not always understand what is happening to them or why they do it. Furthermore, because self-harm is shrouded in stigma, many people may feel they are alone. Many service users suggested that more information be provided to them about self-harm and its prevalence.

‘Information on how common self-injury is would be helpful. I used to feel abnormal and weird as I thought I was the only person to do this. Information could have helped reduce the shame and isolation this caused me.’ (p. 27) Reference Arnold24

Support and information for carers was also suggested by individuals who self-harm and their friends and families. Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33 Better information for the general public was also called for to help alleviate some of the stigmatisation faced by individuals who self-harm. Reference Bywaters and Rolfe33

Adolescents

Recommendations for improvement from youth with a history of self-harm were similar to those from adults. However, specific needs were identified such as the inclusion of adolescents in planning services, walk-in and telephone services, central location of facilities and specialised training for staff working with this population. Reference Bolger, O'Connor, Malone and Fitzpatrick31,Reference Dower, Donald, Kelly and Raphael35

Discussion

This systematic review of the international literature about the attitudes towards clinical services of individuals who self-harm following an episode of self-harm has shown that in spite of differences in country and healthcare systems, many participants' reactions to and perceptions of their management were negative. Participants associated negative experiences of management with perceived lack of patient involvement in management decisions, inappropriate staff behaviour and lack of staff knowledge, problems with the format of psychological assessments and issues with access to after-care. Positive experiences of care were associated with greater participation in care and care decisions and the perception of staff as sympathetic. Service user suggestions for the improvement of services for individuals presenting to hospital after a self-harm episode included the provision of more information to individuals regarding their management and increased engagement in treatment decisions, better provision of information about self-harm for patients, families and the general public, better training for clinical and non-clinical staff about self-harm, and improved access to local services and after-care.

The findings should be considered in the light of several potential limitations. First, the included studies used a variety of methodologies which make it somewhat difficult to compare studies. For example, some qualitative studies included open-ended or semi-structured interviews that make it difficult to say precisely how many people experienced a particular event or had specific attitudes or perceptions about services as interview questions may have evoked different memories from respondents and caused some to leave out particular details. Second, publication bias may also contribute to greater emphasis on negative findings and limit generalisability. We have attempted to get around this by searching the unpublished literature. Unfortunately, only one study was found using this strategy. Reference Hood39 The possibility of researcher bias also exists. In synthesising already synthesised findings, unintended consequences that may be influenced by the background of the reviewers can occur. This review has been undertaken by four authors from both clinical and non-clinical backgrounds with varying experience in the clinical management of individuals who self-harm and conducting qualitative research. We believe that the heterogeneity of the authors' experiences has limited the potential biases in the interpretation of the findings. Lastly, the quality of the studies included in this review (Table 1) may also limit the generalisability of the results. Although in presenting the results we gave more weight to the studies of stronger design, the inclusion of all the studies could have influenced the findings.

A strength of this review is that we were able to pool the findings from 31 studies from several countries. The range of countries included provides an international understanding of the experiences of individuals who self-harm. This review has also allowed for an examination of many aspects of care and the different services used by individuals after a self-harm episode. This enables us to provide recommendations regarding management in general, specific services and the transition from one service to another (e.g. between discharge from the general hospital and after-care).

This review has focused on user attitudes and perceptions, a fuller picture of what happens in patient–staff interactions would be provided by a similar study of staff attitudes and reaction to individuals who self-harm. Such a review is currently in progress.

Implications

Investigating service users' experiences of care is integral to improving the management of people who self-harm and to the possible prevention of self-harm and suicide. Self-harm service users' suggestions need to be considered in the context of government and professional recommendations regarding the management of people who self-harm in order to provide suggestions for how management can be improved for individuals presenting to hospital after a self-harm episode. The findings of this review should further influence national and other guidelines.

Suggestions for clinical practice and service improvement

Services for individuals following a self-harm episode should be accessible, personal and effective. Improved access to emergency and local services might include better advertisement for services aimed at individuals who self-harm and the development of an after-care plan upon discharge from hospital to ease the transition from hospital to out-patient care. Increased operating hours and a location easily accessible by public transport might also improve access to local services.

The therapeutic relationship is an important tool in improving treatment adherence and patient outcomes. Due to the nature of the treatment, establishing rapport with the client could have a significant impact on individuals' perceptions of the quality of their care. Additional steps to personalise care could include engaging people in treatment decisions and considering their personal preferences. Maximising the therapeutic benefits of the psychosocial assessment and ensuring individuals are well enough for discharge could increase treatment adherence.

There is marked variation in the type and quality of services available to people presenting to A&E after a self-harm episode. Reference Bennewith, Gunnell, Peters, Hawton and House8 Many issues including a chronic shortage of doctors and nurses and high staff turnover may have an impact on the quality of care. In order to decrease the variety and increase the quality of care provided, hospitals might establish a self-harm planning group to address issues such as staff training and management protocols. Regular assessment of patient outcomes may increase the effectiveness of services.

In designing services for adolescents presenting at A&E, attention should be paid to the recommendations discussed above. However, services might consider implementing a protocol specific to adolescents and the inclusion of carers in management (but accounting for the age-appropriate consent issues). It is important that professionals providing therapy to adolescents either individually or as a family are sensitive to possible tensions that may undermine engagement or the success of therapy.

Older adults generally show greater suicidal intent when compared with younger populations and risk of death by suicide following self-harm is highest among this group. Reference Hawton, Zahl and Weatherall2 There should be specific guidelines for service provision and clinical management of this group.

Future research

Future research might include the development of a standard interview schedule to assess service users' perceptions of care and would help make studies more easily comparable and could be used for regular audit of services. The schedule should include: individual's satisfaction with physical treatment, psychosocial management (including psychosocial assessment), discharge, referral and after-care, and perceptions of and satisfaction with staff. This interview schedule may also be used in conjunction with open-ended or semi-structured interviews to allow for a more client-centred discussion. Studies evaluating the impact of psychosocial assessment and service users' attitudes towards specific treatments are required. Further research might address the large gap in the literature regarding the experiences of older adults and minority groups. Evaluation of training for staff and of the impact of training on individual's perceptions of services is needed. Finally, in order to better assist those caring for people who self-harm, larger studies examining the impact of self-harm on relatives, and their role in management and its effects, might be conducted.

This review provides some indication of how services might be improved to better meet people's needs following a self-harm episode. Although more research is needed to strengthen our understanding of service users' needs and address the issues of specific subgroups, the findings of this review provide some clear directions for service improvement.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the following for assistance with identifying relevant studies: Shozo Aoki, Diego de Leo, Simon Hatcher, Ad Kerkhof, Esther Lim, Lucy Palmer, Louise Pembroke, Carlos Perez-Avila, Keren Skegg, and Lakshmi Vijayakumar. The authors would also like to acknowledge Rachel Burbeck and the Service Delivery and Organisation team for their assistance during the project. This project was supported by the National Co-ordinating Centre for NHS Service Delivery and Organisation R&D (NCCSDO). K.H. is funded by Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Foundation Trust.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.