I was really excited to gather data because it made me feel like a real part of the democratic process.

–Student observer of polling places, Election Day 2016

Education in order to accomplish its ends both for the individual learner and for society must be based upon experience.

–John Dewey (1938, 89)

Good education requires student experiences that deliver lessons about practice as well as theory and that encourage students to work for the public good—especially in the operation of democratic institutions (Dewey Reference Dewey1923, Reference Dewey1938). Moreover, learning often is enriched when students undergo experiences that compel them to become active participants (Kolb Reference Kolb1984). To this end, political science courses often use active-learning techniques in the classroom including simulations, case studies, and role-play to engage students (Bromley Reference Bromley2013). These activities produce desirable outcomes: increased interest, knowledge, and involvement (Alberda Reference Alberda2016; Bridge Reference Bridge2015; Jimenex Reference Jimenex2015).

Experiential learning extends “learning by doing” beyond the classroom, bringing abstract concepts to life in powerful ways and fostering engagement in political processes. Experiential learning transcends abstract knowledge and leads to meaningful participation in real-world political activities, thereby enhancing the potential for both immediate value to students and contribution to society. Engagement in political processes with real outcomes is important: individuals learn best when their emotions are involved in their experiences and when connections are cemented via repeated exposure (Berger Reference Berger2015).

Existing studies show that experiential learning provides students with opportunities to develop and enhance characteristics of citizenship that are important in a democracy. To foster education’s individual purpose, experiential learning increases knowledge, raises interest in topics studied, and improves classroom engagement (Berry and Robinson Reference Berry and Robinson2012; Cole Reference Cole2003; Currin-Percival and Johnson Reference Currin-Percival and Johnson2010; Lelieveldt and Rossen Reference Lelieveldt and Rossen2009). To foster education’s social purpose, experiential learning develops citizenship skills and has a positive effect on civic engagement and efficacy (Delli Carpini and Keeter Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter2000; Maloyed Reference Maloyed2016; Mariani and Glenn Reference Mariani and Glenn2014).

Delli Carpini and Keeter (2000, 636) asserted that because engaging with real political processes increases students’ interest and opportunities to learn about politics, these experiences “could increase the likelihood of their continued engagement in public life.” An example is Gershtenson et al.’s (2013) experiential exercise in which students were tasked with registering to vote under scenarios that college students typically encounter. Their results indicated that students who sought to complete their voter-registration process found it more difficult than they originally believed and became more sympathetic to those facing registration problems. Thus, when students directly experience political processes—as opposed to simply reading, watching, or hearing about them—this firsthand experience fosters understanding and creates empathy for others who find political processes challenging. Research that focuses on the act of voting, as in our study, therefore should boost interest in citizen participation and concerns about seemingly mundane topics such as the nature and location of polling places.

Research that focuses on the act of voting, as in our study, therefore should boost interest in citizen participation and concerns about seemingly mundane topics such as the nature and location of polling places.

More generally, studies on undergraduate research conclude that it fosters students’ critical thinking, logic, and problem-solving skills (Knoll Reference Knoll2016). Herrick, Matthias, and Nielson (Reference Herrick, Matthias and Nielson2015) argued that student-executed research makes learning more tangible, reinforces lessons by repeated practice, and motivates learning.

This article reports results of a multi-campus experiential-learning project that meets both individual and societal elements of good eduation. On November 8, 2016, faculty from 23 colleges and universities across the country organized more than 500 students who observed the operation of polling places. Each pair of students spent two hours at randomly selected polling places to record the length of lines to vote; duration of each step of the process (i.e., voter check-in, filling out a ballot, and ballot submission); setup of the polling place; availability of instructions and assistance; and other details of the operation.

After Election Day, we surveyed students to assess the pedagogical impact of their experience. Our data indicated that student experiences were powerful and valuable, with positive impacts on both short-term learning and continued interest in election processes. The firsthand experience of the 2016 election increased student knowledge of election science topics, raised interest in learning, and stimulated interest in participating in future research. Moreover, the students’ participation in collecting important and previously unavailable data about voting processes demonstrated the capacity for research to improve democracy.

Experiental learning can be tricky in political science, especially when it involves elections, because instructors cannot ask students to engage in political advocacy. Our project avoided these issues by providing experiential immersion in the political process in an explicitly and thoroughly non-partisan manner. Although participating students did not turn election machinery themselves, the rigor, detail, and training in our research protocol prompted them to be broadly and deeply attentive to the 2016 election process, and this exposed them to locations, processes, and people whom they might not otherwise encounter. The project gave students opportunities to gain a better understanding of the research process, to interact with local communities, and to connect observable political phenomena with the production of original data to better understand voting experiences. “Any class that involves field work…or direct engagement with the world outside the campus can engage students’ imaginations, creativity, energy, and even emotions in ways that make learning expand and endure” (Berger Reference Berger2015).

RESEARCH METHOD

Our research assessed the pedagogical impact on students participating in the Polling Place Lines Project coordinated by Charles Stewart III, Christopher Mann, and Michael Herron. The election science research questions of that project are described in Stein et al. (2017). Our research question focused on whether the experience of observing polling locations on Election Day as part of a data-collection process produced pedagogical value for the students.

Studies on student learning are usually singular in nature: one point in time, at one place, and focused on one type of student (Alberda Reference Alberda2016; Berry and Robinson Reference Berry and Robinson2012; Bridge Reference Bridge2015; Jimenex Reference Jimenex2015). Our study was distinct from previous research on experiential learning in political science in three ways. First, it encompassed learning experiences across 23 institutions ranging from small colleges to major research universities, producing a larger dataset than generally found in pedagogical research in political science. Second, our students ranged from first-year undergraduates to graduate students. Third, the students were in various locations across the entire country: in urban, suburban, and rural settings. Our study thus reflected greater heterogeneity in research locations and student participants than typical research settings.

For the polling-place observations, each student was trained on a detailed research protocol developed by Stewart, Mann, and Herron to measure polling-place lines, how long it took to vote, and other aspects of polling-place operations. Participating faculty organized and trained students to make observations at randomly selected polling locations in their areas. Many faculty used the research project as a platform for teaching research methods, election science, or other related topics; thus, students were prepared for and invested in the fieldwork in multiple ways.

Participating faculty organized and trained students to make observations at randomly selected polling locations in their areas. Many faculty used the research project as a platform for teaching research methods, election science, and other related topics; thus, students were prepared for and invested in the fieldwork in multiple ways.

Using students as field researchers provided multiple avenues for them to gain firsthand knowledge of the research process and the conduct of elections. “[H]ands-on experience in the field allow[s] students to synthesize acquired knowledge, practice it in the real-world setting, and reinforce the learning” (Herrick et al. Reference Herrick, Matthias and Nielson2015). Our project offered a tangible and repetitive experience for students as they visited multiple voting locations in the course of their field-research experiences. During their training, they learned about research design, how the voting experience can be affected by lines, and other aspects of election science. They then spent from two to 12 hours in the field, where their task of data collection repeated and the learning was reinforced.

Our assessment of the pedagogical value of polling-place observation used a postelection survey, thereby following established research on experiential and active learning. Surveys of participants comprise an effective and appropriate approach to quantify the experience of students in active or experiential learning. Past pedagogical research administered surveys after active or experiential-learning activity as a means to examine student outcomes (Alberda Reference Alberda2016; Gershtenson et al. Reference Gershtenson, Plane, Scacco and Thomas2013; Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Saunders, Rainsford and Thompson2014). Using survey measures is valuable because doing so moves beyond anecdotal evidence and allows researchers to measure empirically students’ reactions to their fieldwork experiences. A survey also was necessary for our study to measure quickly and consistently the impact on nearly 500 students across 23 campuses.Footnote 1

We asked faculty participating in the 2016 Polling Place Lines Project to administer a survey to their students after Election Day. Faculty at 23 institutions agreed to participate. The survey team at Skidmore College provided an anonymous link to each participating institution through the online survey platform Qualtrics. Faculty at each institution then sent the survey link to their students.

The surveys were completed between November 10 and 30, 2016; 92% were completed in the week after Election Day. Each institution received a unique instance of the survey in Qualtrics to track response rates by institution. Identifying information about individual respondents was not collected. However, to encourage survey completion, faculty followed up with students via mass emails, classroom announcements, and other means. We received 479 responses to the survey, resulting in a cooperation rate of more than 90% of eligible students.Footnote 2

The full survey instrument is in the Supplemental Online Materials (SOM) and key questions are detailed with corresponding results in the next section. The questions used in our survey are similar to those used by other scholars who previously evaluated experiential and active learning (Jackson Reference Jackson2013; Maloyed Reference Maloyed2016).

WHO PARTICIPATED IN THE POLLING-PLACE OBSERVATION EXPERIENCE?

Participants in the Polling Place Lines Project were almost evenly distributed across the four undergraduate classes and graduate students: first year (21%), sophomore (19%), junior (22%), senior (21%), and graduate students (17%). A majority of students (56%) participated because it was required for class, especially undergraduates (63%); 25% participated for extra credit; and 64% of volunteers and 58% of “other” participants were graduate students.

Overall, student participants reported being well prepared for their fieldwork on Election Day (figure 1): 52% said they were well prepared and 27% very well prepared; only 2% said they were not well prepared. This pattern is consistent for each of the four undergraduate cohorts and graduate students, indicating that perception of preparation was due to training and/or coursework provided during the fall of 2016.

Figure 1 How Well Prepared Were You Ahead of Time for the Activity on Election Day?

ASSESSMENT OF LEARNING

The survey asked students several questions to probe their self-assessment of individual learning. Overall, 65% of students said they learned a lot (13%) or a good amount (52%). Figure 2 shows that more advanced students—seniors (73%) and graduate students (74%)—appeared to report slightly more learning. However, variation across classes is not statistically significant (i.e., Pearson χ2(12) = 13.03, p = 0.367). More generally, 75% of participants considered the time they spent on the project to be very (24%) or somewhat (51%) valuable (SOM figure 2a). The fact that students frequently perceived engaging in the voting process as a valuable use of time is encouraging because this engagement might spill over into other aspects of political life.

Figure 2 How Much Would You Say You Learned from Your Election Day Experiences?

Among the 257 students who reported that they were required to participate as part of a course, 47% stated that the experience enhanced their understanding of course materials a lot (12%) or a good amount (35%) (SOM figure 2b). Another 39% reported that their experiences enhanced their understanding a small amount. Election science comprised only a small part of many broad courses that participated (e.g., Introduction to American Politics, Campaigns & Elections, Voting Behavior, and Research Methods). Therefore, our question that was aimed at participating students who were required to work in our study should have been worded more carefully. With this caveat, the overall contribution to enhanced understanding of course materials is encouraging.

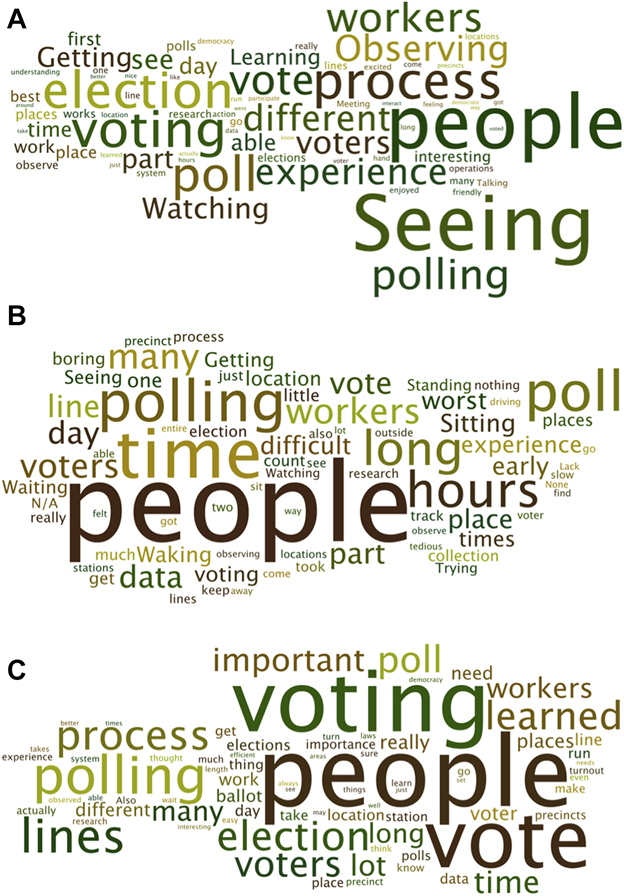

At the end of the survey, students were given open-ended prompts to report the best part of their experiences, the worst part, and the most important lesson learned. Figures 3a through 3c are word clouds that highlight the most prominent terms in corresponding responses. Interpretation of open-ended survey responses is ambiguous, especially when compliance varied widely and few covariates were available (Roberts et al. 2014).Footnote 3 However, the simple word-cloud analysis suggests that student experiences were consistent with our pedagogical goals. Reflecting the pervasive human element of polling-place operations and voting, the term “people” is highly prominent in responses to best, worst, and most important. As expected, terms related to the research project including “voting,” “election,” and “poll” also occurred frequently in all three sets of responses. In the best-part responses, the prominence of words such as “seeing,” “observing,” “watching,” “experience,” and “learning” indicated that students found the research task engaging. Unsurprisingly, the worst-part responses highlighted the downside of field research in terms including “time” and “long hours,” along with references to “waiting,” “waking,” “sitting,” “standing,” and—of course—“boring.” Because one of our pedagogical goals was to increase appreciation for the research process, these terms can be taken as evidence of learning (and not simply complaints). The most-important-lesson responses focused, as we had hoped, on terms such as “people,” “vote,” “voting,” “lines,” and “process,” which highlight the societal and administrative dynamics associated with voting.

Figure 3 Word Cloud from (a) “The Best Part of Your Experience” (b) “The Worst Part of Your Experience” (c) “The Most Important Lessons You Learned”

Created with wordle.net. Limited to 75 key words.

We also asked students to compare their knowledge of 11 topics before and after their experiences.Footnote 4 Although retrospective self-reporting of change is an imperfect measurement of knowledge gain, this method also was used in previous studies (Alberda Reference Alberda2016; Endersby and Weber 1995; Pappas and Peaden Reference Pappas and Peaden2004). We believe the retrospective report is indicative of Dewey’s social purpose for education: engagement and increased efficacy. Moreover, our findings suggest greater perceived knowledge. These are valuable pedagogical outcomes even if self-reporting is less than ideal for capturing true knowledge gain. Figure 4 compares students’ knowledge before Election Day (gray bars) to their knowledge after the observation experience (black bars) on 11 topics. In every case, the post-experience distribution shifts to the right, from knowing “very little” toward knowing “a lot.” After their experiences, students felt more knowledgeable about election science topics including lines of voters, Election Day operations, poll workers, poll watchers from candidates and parties, election law, and how elections are administered. Moreover, they reported more knowledge about why voters do or do not vote and about methodological issues such as research design, research ethics, data collection, and fieldwork challenges. Insight on these topics is valuable because they are not limited to a particular course; indeed, they are useful across courses and disciplines.

We believe the retrospective report is indicative of Dewey’s social purpose for education: engagement and increased efficacy.

Figure 4 Knowledge Before and After Election Day Observation Experience

ASSESSMENT OF FUTURE INTEREST

Our survey also measured students’ engagement with election science and research. Despite recently experiencing the grind of data collection in the field, 52% said they were extremely (21%) or very (30%) likely to participate in a similar research project (figure 5). Only 11% said they were not at all likely to do so. When asked if they would recommend that a friend participate in a similar project, 58% said they were extremely (24%) or very (34%) likely to do so (SOM figure 5). Only 8% said that they were not at all likely to recommend the experience to others.

Figure 5 How Likely Would You Be to Participate in a Similar Research Project about Voting Activity?

We also asked students whether they would like to learn more about several election science topics (figure 6). (Asking whether they would like to do more research about these topics produced highly similar responses; see SOM figure 6.) Narrow election science topics of lines and poll workers did not prompt high levels interest for learning or research. However, it is probably safe to assert that the levels among these students were still dramatically higher than among the public. Students reported more interest in future work on Election Day operations, perhaps because the broader term encompassed more aspects of their experience. Election law, election science generally, and reasons for voter participation drew high levels of interest for future work. Whereas faculty may immediately think of course-enrollment implications, the more important aspect of this interest is the engagement of these students with democratic processes.

Figure 6 How Interested Are You in Learning More about the Following Topics?

DISCUSSION

Experiential-learning opportunities such as our project provide students a chance to learn about political processes outside of the classroom and in a concrete, tangible manner. Instructors who tap into these opportunities create a space for students to learn and foster important societal values, such as various qualities of citizenship. Our findings indicate that the Polling Place Lines Project was a valuable learning experience in the short and long terms. With respect to the short term, students found their experiences to be valuable and reported learning generally and specifically related to course material; postelection, they also felt more knowledgeable about election science topics, voting behavior, and research methods. They reported interest in participating in similar research in the future, would recommend other students to do so, and expressed interest in more learning and research about the topics central to their experience. Our results suggest that participants appreciated the importance and the study of elections. Collectively, the participating students were engaged and efficacious—essential qualities of citizens in a democracy.

Furthermore, it is worth noting that this article assesses only the common denominator of the students’ Election Day experiences. Many participating faculty enriched the Election Day experience with attention in their courses to election science, voting behavior, public policy, public administration, and more. Several participating faculty used the data collected by their students to teach empirical analysis. This article provides a conservative estimate of the pedagogical value of our 2016 polling-place-observation project.

The project highlights the multifaceted importance of and potential for collaboration. First, nearly all participating faculty found local election administrators to be cooperative. Many of these public officials were enthusiastic about engaging students with the election process. Second, the collaboration among faculty at different colleges and universities worked well. For research on polling-place operations, this collaboration provided a dataset heretofore unavailable about polling-place lines and other characteristics in different jurisdictions during a single election. Pedagogically, the collaboration was limited to participation in the learning-assessment survey. Greater collaboration could further bolster the pedagogical value with activities such as videoconference presentations and discussions among students observing different jurisdictions.

The 2016 Polling Place Lines Project is the genesis of our ongoing project. We invite faculty members at other institutions to join the 2018 Polling Place Lines Project for the pedagogical opportunity for their students as well as supporting the research. If interested, please contact Christopher Mann ([email protected]), Charles Stewart III ([email protected]), or Michael Herron ([email protected]).

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096518000550

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support for this project was partially provided by the Democracy Fund, which bears no responsibility for the analysis. This article was presented at the 2017 Midwest Political Science Association Annual Meeting. We thank the anonymous reviewers and Barry Burden, Paul Gronke, Kathleen Hale, and Thad Hall for helpful comments on previous versions.