Introduction

Brachiopods are a group of marine benthic filter-feeding organisms using cilia aligned on the tentacles of the lophophore to capture food particles from seawater (James et al., Reference James, Ansell, Collins, Curry, Peck and Rhodes1992; Strathmann, Reference Strathmann2005). Studies of recent brachiopods have classified the shape of the lophophore into several types, such as ptycholophe, plectolophe, and spirolophe (Rudwick, Reference Rudwick1962, Reference Rudwick1970; Emig, Reference Emig1992; Williams et al., Reference Williams, James, Emig, Mackay, Rhodes and Kaesler1997a). The spirolophe, in which the tips of the brachia diverge from each other to form a pair of freely coiled spirals, occurs in many modern inarticulates, rhynchonellides, and possibly the terebratulide genus Leptothyrella Muir-Wood in Muir-Wood et al., Reference Muir-Wood, Elliott, Kotora and Moore1965 (Muir-Wood, Reference Muir-Wood and Moore1965; Emig, Reference Emig1992). This type of lophophore is also thought to have been present in fossil inarticulates, rhynchonellides, atrypides, athyridides, spiriferides, and spiriferinides (Rudwick, Reference Rudwick1970). In particular, the last four groups have calcareous spiralia to support their lophophore, perhaps dealing with a more complex feeding system.

The classification of the spire-bearing brachiopods (atrypides, athyridides, spiriferides, and spiriferinides) has been revised many times since Davidson's (Reference Davidson1882) first proposal, which emphasized the direction of spiralia and the presence/absence of jugal structures. Although the taxonomic ranks of spire-bearers have been modified several times, initially classified as families (Davidson, Reference Davidson1882; Waagen, Reference Waagen1883), then suborders (Boucot et al., Reference Boucot, Johnson, Pitrat, Staton and Moore1965; Ivanova, Reference Ivanova1972), and finally in the orders of modern classifications (Cooper and Grant, Reference Cooper and Grant1976b; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Johnson, Gourvennec and Hou1994, Reference Carter, Johnson, Gourvennec, Hou and Kaesler2006; Alvarez and Rong, Reference Alvarez, Rong and Kaesler2002; Copper, Reference Copper and Kaesler2002; Carter and Johnson, Reference Carter, Johnson and Kaesler2006), the diagnostic characteristics differentiating the groups have never changed. Other features of the brachidia, such as development of the jugal structures and number of coils within spiralia, are also of diagnostic significance within the suprageneric groups in Atrypida and Athyridida. However, the morphology of brachidia has never been considered significant in the intra-classification of Spiriferida. Instead, shell form, ornamentation, cardinalia, and other structures have been considered more important (Boucot et al., Reference Boucot, Johnson, Pitrat, Staton and Moore1965; Waterhouse, Reference Waterhouse1968, Reference Waterhouse1998; Havlíček, Reference Havlíček1971; Carter, Reference Carter1974; Archbold and Thomas, Reference Archbold and Thomas1986; Goldman and Mitchell, Reference Goldman and Mitchell1990).

By the time the punctate Spiriferinida was raised to the order level (Cooper and Grant, Reference Cooper and Grant1976b), the brachidium had wholly lost its taxonomic significance within the suprageneric groups in Spiriferida (Carter and Johnson, Reference Carter, Johnson and Kaesler2006) and was rarely taken into account. Thus, descriptions of the brachidia, especially for the primary lamellae and spiralia, were usually incomplete in numerous investigations (e.g., Campbell, Reference Campbell1961; Carter, Reference Carter1972, Reference Carter1974, Reference Carter1985; Cooper and Dutro, Reference Cooper and Dutro1982; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Kaiho, George and Tong2006; Zhang and Ma, Reference Zhang and Ma2019). One reason for neglecting brachidia may be attributed to their limited preservation because this calcareous support for the lophophores is very fragile and easily damaged or even completely destroyed by the post-mortem filling of shell interiors with coarse sediment and subsequent diagenetic processes. The techniques used to visualize the internal structures (e.g., acid etching of silicified specimens, serial sectioning) are also time-consuming and the results are sometimes hard to interpret, therefore many studies have been focused on the umbonal region of the specimens to investigate the morphologies of cardinalia and crura only.

Despite the difficulties in recognizing brachidial features, we describe the morphological variations in the spiralia that support the lophophore and its connection structure to the cardinalia (crura), suggesting several types of brachidium. The distribution of these types of brachidium within the suprageneric groups is examined and the possible phylogenic relationship between these brachidia is discussed.

Materials and methods

The brachidium data in this study included 63 spiriferide brachiopod species recorded in the literature and two spiriferide brachiopod species (Eochoristites neipentaiensis Chu, Reference Chu1933 and Weiningia ziyunensis Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Sun, Shen, Xing, Liu, Yang, Qin and Baliński2019; Fig. 1; Table 1) studied herein. The data selected from the literature are mainly based on whether a publication includes a restoration of the brachidium, figured serial sections, or figured specimens that clearly show or describe the crura and brachidium of the selected taxon. Unfortunately, many taxa that were described with spiralia in the literature are not compiled into the current dataset because most of their brachidial information is limited to the direction of the spiralia and coiling number, and the figured serial sections of specimens, if present, inadequately represent the complete brachidium. The serial sections of E. neipentaiensis and W. ziyunensis were recorded as both digital images and acetate peels and drawn from the digital images under the software CorelDRAW-X6. The images of the specimens and sections were taken using a Nikon SM1500 stereomicroscope equipped with a Nikon DS-Fi3 microscope camera and Nikon Eclipse Lv100pol microscope equipped with a Nikon DXM1200F camera, respectively. Sixty-five species belonging to 34 genera, 17 families, and eight superfamilies were analyzed (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 1. (1–8) Eochoristites neipentaiensis: (1–5) PKUM 02–0930, ventral, dorsal, lateral, anterior, and posterior views; (6, 7) PKUM 02–0929, dorsal view (6) and (7) enlargement of anterior region; arrow on the left side of (7) indicates the primary lamellae; arrow on the right side of (7) indicates the first whorl of spiralium; (8) PKUM 02–0931, ventral view showing posterolaterally directed spiralium on the left side. (9–15) Weiningia ziyunensis: (9–13) PKUM 02–0925, ventral, dorsal, lateral, anterior, and posterior views; (14, 15) transverse sections of PKUM 02–0850 (23.75 mm long); distances from the tip of ventral beak are 17.00 mm (14) and 20.20 mm (15); arrows indicate the change from rod-like crura to plate-like primary lamellae. Scale bars represent 10 mm.

Table 1. Information on the two spiriferide species sectioned in this study.

In this study, we followed Williams and Brunton's (Reference Williams, Brunton and Kaesler1997) definitions of crura, primary lamellae, and spiralia. The crura are paired rod- or plate-like processes extending from the cardinalia or septum that support the posterior end of the lophophores, and their distal ends are prolonged into the plate-like primary lamellae of the spires in the extinct spire-bearing stocks. The spiralia are a pair of spiral lamellae in the spire-bearing brachiopods (equal to the brachidia), representing outgrowths from the crura, extending well into the mantle cavity and supporting the lophophores, while the primary lamellae are the first half whorls of each spiralium distal from their attachment to the crura.

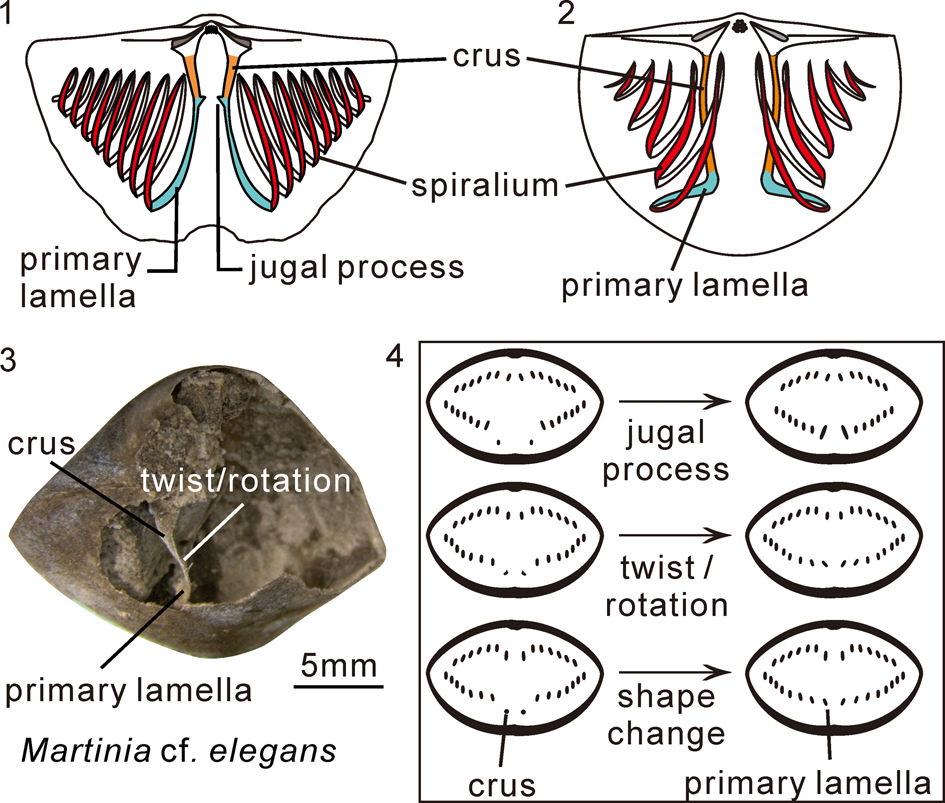

To investigate variations of the brachidia in Spiriferida, the morphological features of the crura, primary lamellae, and subsequent spires were examined for each of the selected taxa, including the direction (divergent/convergent/subparallel) and shape (rod-like/plate-like) of the crura and primary lamellae, the crura type (normal/prolonged), and the starting position and direction of the primary lamellae. The direction (posterolateral/lateral), spiral alignment, and coiling number of the spiralia were examined as well. Normal crura refer to those supporting the spiralia posterodorsally, while the prolonged crura refer to those extending to or even beyond the anterior margin of the spiralia (Fig. 2.1, 2.2).

Figure 2. Diagrammatic drawing showing generalized brachidial types and segments, as well as morphological changes at crura-primary lamellae junction. (1) Normal brachidium; (2) modified brachidium; (3) twist/rotation at crura-primary lamellae junction, photographed from the specimen (NIGP143574) used in Shen and Clapham, Reference Shen and Clapham2009; (4) morphological changes at crura-primary lamellae junction in succeeding serial sections.

When the crura extend forward in level dorsal to the spiralia to merge with the primary lamellae, there will be jugal processes, twists or rotation, attenuation, ventral bending, and even shape changes in the cross-section. These morphological features and changes were used to determine the boundary of the two different elements in this paper (Fig. 2.3, 2.4).

As several previous studies have revealed, congeneric species, such as those of Crurithyris George, Reference George1931 (Cooper and Grant, Reference Cooper and Grant1976a; Brunton, Reference Brunton1984; Sun and Baliński, Reference Sun and Baliński2011), Eospirifer Schuchert, Reference Schuchert and von Zittel1913, and Striispirifer Cooper and Muir-Wood, Reference Cooper and Muir-Wood1951 (Rong and Zhan, Reference Rong and Zhan1996), basically share the same pattern of crura and brachidia (i.e., the type of crura and primary lamellae, configuration of jugal processes and spiral cones, and probably the direction of the spiralia). Here, E. minutus Rong and Yang, Reference Rong and Yang1978, is considered to have jugal processes similar to other species of Eospirifer because the weak geniculation at the junction between crura and primary lamellae (Rong and Zhan, Reference Rong and Zhan1996, fig. 9) may in fact represent the rudimentary jugal processes. Variation of the brachidia in the spririferides discussed in this paper is mainly concerned with the generic rather than specific level characteristics, although there are exceptions.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

All illustrated and sectioned specimens in this study are housed in the Geological Museum of Peking University (PKUM), Beijing, China.

Results

Crura and brachidium morphologies of Eochoristites neipentaiensis and Weiningia ziyunensis.—As the type species of Eochoristites Chu, Reference Chu1933, E. neipentaiensis is a characteristic and widely recognized index brachiopod species for the early Carboniferous (Tournaisian) deposits in South China (Jin, Reference Jin1961; Yang, Reference Yang1964; Yang et al., Reference Yang, Ni, Chang and Zhao1977; Tan, Reference Tan, Tan, Dong, Jin, Li and Yang1987; Sun and Baliński, Reference Sun and Baliński2011). Weathered and sectioned material (Figs. 1.6–1.8, 3.1) from the Guilin area reveals paired plate-like crura that are ventrolaterally inclined and sub-parallel, becoming slightly convergent to the anterior, and give rise to the primary lamellae near the mid-point of the dorsal valve (Fig. 3.1d–f). Very small and probably posteriorly pointed jugal processes are observed in the junction between the crura and primary lamellae (Fig. 3.1e). The primary lamellae are plate-like and divergent toward the anterior (Fig. 1.7). The spiralium is posterolaterally directed (Figs. 2.8, 3.1), containing 11–16 whorls. The brachidial restoration of this species is given in Figure 5.

Figure 3. Transverse serial sections of Eochoristites neipentaiensis (posterior view) and longitudinal serial sections of Weiningia ziyunensis (dorsal view): (1) Eochoristites neipentaiensis, PKUM 02–0929 (24 sections made and 9 selected herein). Distances measured in millimeters from the tip of ventral beak. Dash lines represent the symmetry planes of shell. (2) Weiningia ziyunensis, PKUM 02–0928 (27 sections made and 13 selected herein). Distances measured in millimeters from the most convex part of ventral valve. Dashed lines represent the symmetry planes of shell. Arrows indicate the changes from rod-like crura to plate-like primary lamellae (16.35–10.80 mm).

Weiningia ziyunensis is a newly named species of the family Martiniidae from the lower Carboniferous Baizuo Formation (Serpukhovian) of Ziyun County, Guizhou Province (Yuan et al., Reference Yuan, Sun, Shen, Xing, Liu, Yang, Qin and Baliński2019). The serial sections and restoration of its brachidium show that the crura are rod-like and very long, and exhibit a repetition of divergence and convergence from the crural bases to the front of the spiralia (Figs. 3.2d, 3.2e, 4, 5.3). The primary lamellae can be distinguished from the rod-like crura by their plate-like cross-sections (Figs. 3.2e–g, 4.1j–m, 4.2g–j, 4.3d–f). Starting from the distal end of the crura, the primary lamellae run some distance lateroventrally and then reversely flex towards the mid-line, forming semi-circular loops that are laterally convex and perpendicular to the commissural plane in front of the spiral cones (Figs. 3.2j–m, 4.1m, 4.1n, 4.2j, 4.2k, 4.3h. 5.3, 5.4), after which they turn posteriorly near the mid-line to produce the rest of the spires (Fig. 5.4). This is peculiar among the spiriferide brachidia. Spiralia are located relatively close to the anterior of the shell, with their posterior margins slightly behind the mid-valve. Spiral cones are directed posterolaterally, usually containing 10–14 whorls.

Figure 4. Transverse serial sections of Weiningia ziyunensis (posterior view): (1) PKUM 02–0850 (31 sections made and 14 selected herein); (2) PKUM 02–0926 (44 sections made and 11 selected herein); (3) PKUM 02–0927 (28 sections made and 8 selected herein). Distances measured in millimeters from the tip of the broken (1) and complete (2, 3) ventral beaks. Dashed lines represent the symmetry planes of shell. Arrows indicate the changes from rod-like crura to plate-like primary lamellae: 17.00–20.20 mm in (1), 25.25–29.35 mm in (2), 11.00–12.05 mm in (3).

Figure 5. Reconstruction of the brachidia of selected spiriferide taxa. (1, 2) Eochoristites niepentaiensis, dorsal and ventral views; (3, 4) Weiningia ziyunensis, dorsal and ventral views; (5) Eospirifer radiatus (Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1834), dorsal view, redrawn from Rong and Zhan (Reference Rong and Zhan1996, fig. 13); (6, 7) Emanuella plicata Grabau, Reference Grabau1931, dorsal and ventral views, based on serial sections in Zhang (Reference Zhang2016); (8) “Emanuella” meristoides, ventral view, based on serial sections in Caldwell (Reference Caldwell and Oswald1968, fig. 4); (9) Ladjia sp., ventral view, redrawn from Ma (Reference Ma2009); (10) Biconvexiella convexa, ventral view, redrawn from Armstrong (Reference Armstrong1968); (11, 12) Crurithyris urei (Fleming, Reference Fleming1828), ventral and lateral views, drawing from Brunton (Reference Brunton1984, fig. 90a, b); (13, 14) Orbicoelia speciosa (Wang, Reference Wang1956), dorsal and ventral views, based on serial sections in Jin and Sun (Reference Jin and Sun1981); (15, 16) Crurithyris tumibilis Cooper and Grant,Reference Cooper and Grant1976a, drawing from Cooper and Grant (Reference Cooper and Grant1976a, pl. 590, figs. 50, 52).

Variations of the crura and brachidium in the selected spiriferide brachiopods

Among the selected taxa, most possess normal crura that are generally restricted in the posterior part of the shell (e.g., Eospirifer, Eochoristites; Fig. 5.1, 5.5), but in Weiningia Jin and Liao, Reference Jin and Liao1974, Attenuatella Stehli, Reference Stehli1954, Biconvexiella Waterhouse, Reference Waterhouse1983, Cruricella Grant, Reference Grant1976, Crurithyris, and Orbicoelia Waterhouse and Piyasin, Reference Waterhouse and Piyasin1970, the crura are prolonged and can extend to the anterior part, or even in front of the spiralia (Fig. 5.3, 5.10–5.16). The crura can be rod- or plate-like in different taxa, but are exclusively rod-like when prolonged. The crura also can be divergent, convergent, or sub-parallel towards the anterior in different genera, and seem to be consistent among congeneric species. For example, the crura are divergent in Eospirifer and Striispirifer (Rong and Zhan, Reference Rong and Zhan1996) and sub-parallel in Crurithyris (Brunton and Champion, Reference Brunton and Champion1974; Cooper and Grant, Reference Cooper and Grant1976a; Brunton, Reference Brunton1984; Sun and Baliński, Reference Sun and Baliński2011; Fig. 5.11, 5.15). In W. ziyunensis, the crura display a repetition of divergence and convergence (Fig. 5.3). At the junction between the crura and primary lamellae, there is a twist or rotation in taxa such as Eochoristites, Spinocyrtia Frederiks, Reference Frederiks1916, Martinia M'Coy, Reference M'Coy1844, Neospirifer Frederiks, Reference Frederiks1924, and Gypospirifer Cooper and Grant, Reference Cooper and Grant1976a (Ager and Riggs, Reference Ager and Riggs1964; Fig. 2.3), evident jugal processes in Eospirifer, Striispirifer, and Anthracothyrina Legrand-Blain, Reference Legrand-Blain, Legrand-Blain, Devolvé and Perret1984 (Rong and Zhan, Reference Rong and Zhan1996; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Chen, Lee and Zhan2016), and a change from being rod-like to plate-like in Crurithyris, Ladjia Veevers, Reference Veevers1959, and Weiningia (Ma, Reference Ma2009; Figs. 3.2, 4, 5.9, 5.11).

Compared to the crura, the primary lamellae exhibit more variation in terms of the configuration of jugal processes and curvature types. The jugal processes are medioventrally or posteroventrally directed and have been described in some of the selected taxa, such as Eospirifer, Striispirifer, Martinia, and Lepidospirifer Cooper and Grant, Reference Cooper and Grant1969 (Cooper and Grant, Reference Cooper and Grant1976a; Rong and Zhan, Reference Rong and Zhan1996; Fig. 5.5). Among all superfamilies, only the genera belonging to Cyrtospiriferoidea, Ambocoelioidea, and Reticularioidea are not equipped with jugal processes, but this may reflect the limited number of taxa examined in detail. The cross angle between the paired jugal process, which was previously used to describe the angle between these structures in the cross-section (Rong and Zhan, Reference Rong and Zhan1996), is variable among different genera, such as Eospirifer, Striispirifer, Anthracothyrina, Costispirifer Cooper, Reference Cooper1942, and Johndearia Waterhouse, Reference Waterhouse1998 (Hall and Clarke, Reference Hall and Clarke1894; Campbell, Reference Campbell1961; Rong and Zhan, Reference Rong and Zhan1996; Shi et al., Reference Shi, Chen, Lee and Zhan2016). According to those species in Eospirifer recorded by Rong and Zhan (Reference Rong and Zhan1996), this angle could be variable among congeneric species as well.

In most studied taxa, the primary lamellae run anteroventrally from the distal ends of the crura, and keep a consistent course and morphological trend with the subsequent spires (Fig. 5). This kind of primary lamellae is called the normal type herein. In some ambocoeliines and Weiningia, the primary lamellae initiate anterior to the spiral cones and display different forms. From the distal ends of the crura, they run lateroventrally in Crurithyris and Weiningia, and medioventally in Attenuatella, Biconvexiella, Cruricella, and Orbicoelia, representing two modified types of primary lamellae—lateral- and medial-convex, respectively. After extending into the ventral valve, the primary lamellae in Crurithyris gradually go posteriorly into the spires (Fig. 5.11, 5.16), while those in Weiningia reversely flex towards the mid-line to form semi-circular loops in front of the spires (Fig. 5.3, 5.4). This may suggest that the primary lamellae in Weiningia are more complex than those in Crurithyris, although the primary lamellae in both genera are regarded as lateral-convex type. As for Attenuatella, Biconvexiella, Cruricella, and Orbicoelia, the primary lamellae in Cruricella run into spires medioventrally (Grant, Reference Grant1976), whereas those in Attenuatella, Biconvexiella, and Orbicoelia exhibit S-shaped curvatures (Waterhouse, Reference Waterhouse1964; Fig. 5.10, 5.14), indicating the simple medial-convex primary lamellae in Cruricella and the complex ones in the other three ambocoeliines. In addition, the well-preserved specimens of Crurithyris in Cooper and Grant (Reference Cooper and Grant1976a), Brunton (Reference Brunton1984), and Sun and Baliński (Reference Sun and Baliński2011) clearly show that the primary lamellae in this genus are evidently wider than the subsequent spiral lamellae (Fig. 5.11, 5.12, 5.15). Similar widening primary lamellae are also observed in Attenuatella, Biconvexiella, Cruricella, and Orbicoelia (Waterhouse, Reference Waterhouse1964; Armstrong, Reference Armstrong1968; Cooper and Grant, Reference Cooper and Grant1976a, Reference Cooper and Grantb; Grant, Reference Grant1976; Jin and Sun, Reference Jin and Sun1981; Fig. 5.10–5.16). Thus, widening of the primary lamellae can be considered an important synapomorphy of these ambocoeliines.

In Spiriferida, the coil number of spiralia is highly variable, ranging from a few to >20. For example, Ager and Riggs (Reference Ager and Riggs1964) recorded at least 25 whorls of the spiralium in Spinocyrtia. This feature is generally dependent on the growth stage, shell size, and shape. Although the coil number of spiralia is expected to vary from one species to another, the spiral coil is nearly absent in Attenuatella and Biconvexiella. This was shown in some specimens that were carefully examined by Armstrong (B. convexa Armstrong, Reference Armstrong1968) and Cooper and Grant (Reference Cooper and Grant1976a, A. attenuata Cloud, Reference Cloud, King, Dunbar, Cloud and Miller1944); thus the absence of spiral coil in the two genera should be attributed to reduced spiralia, possibly reflecting paedomorphosis rather than aplasia in ontogenetic growth.

The spiralia are directed posterolaterally toward the cardinal extremities in most of the studied taxa, such as those in Eochoristites and Eospirifer (Fig. 5.1, 5.5), and laterally directed in some smooth spiriferides with subovate-to-round shell outline (e.g., Weiningia and Emanuella Grabau, Reference Grabau1923) (Fig. 5.3, 5.6). Lee et al. (Reference Lee, Shi, Jung and Kim2019a) recently reported ventrally directed spiralia in the Permian spiriferellide brachiopod Spiriferella protodraschei Lee and Shi in Lee et al., Reference Lee, Shi, Woo, Park, Oh, Kim, Nakrem and Tazawa2019b. Their reconstruction revealed that each spiralium in the specimen is almost uniform in diameter and does not show the apically tapering pattern, and they appear to have directly developed from strong and anteriorly extended crura. Based on the extraordinary orientation and form of the spiralia, the authors suggested that this species likely had developed a considerably modified feeding pattern similar to that of the living rhynchonellides. However, the direction of the spiralia in this species probably needs further study because the possibility of a degree of post-mortem distortion could not be completely ruled out due to the constraints posed by the single specimen. For this reason, its crura and brachidium are not considered in our discussion.

Discussion

Types of brachidium in Spiriferida

Given the variations of the primary lamellae and spiralia discussed above, the brachidia in Spiriferida can be assigned to the normal and modified groups according to the configuration of the jugal processes and spires, as well as types of the crura and primary lamellae (Fig. 5). The number of spiral coils, which varies not only within species during ontogeny (Rong and Zhan, Reference Rong and Zhan1996) but also among species (Table 2), is not considered significant. Similarly, the direction of the spiralia is also of little importance for its low variability. The normal group dominates in the studied taxa and is represented by shells with the normal primary lamellae that are supported by the normal crura, with or without the jugal processes. The modified group is less common and characterized by the absence of jugal processes and the modified (lateral- and medial-convex) primary lamellae that are supported by the prolonged crura.

Table 2. Brachidium structure of the selected taxa in Spiriferida Waagen, Reference Waagen1883. TS = transverse shape, JCP = junction between crus and primary lamella, JP = jugal process, TPL = type of primary lamella, CNS = coil number of spiralium, TB = type of brachidium, SR = stratigraphic range.

The normal group can be divided into Type-I and Type-II based on the presence or absence of the jugal processes. The former possesses jugal processes, normal primary lamellae, and spiral coils (Fig. 5.1). This type is found in Eospirifer, Striispirifer, Eochoristites, Martinia, Anthracothyrina, Neospirifer, Gypospirifer, Lepidospirifer, Spiriferella Chernyshev, Reference Chernyshev1902, and Costispirifer (Table 2). Type-II, with normal primary lamellae and spiral coils, is distinguished from Type-I by the absence of the jugal processes. This type includes a large proportion of taxa not only within the normal group but also in all studied taxa, including Spinocyrtia, Orthospirifer Pitrat, Reference Pitrat1975, Ambocoelia Hall, Reference Hall1860, Ambothyris George, Reference George1931, Emanuella, Ladjia, Xiangia Lü and Ma, Reference Lü and Ma2017, Elythyna Rzhonsnitskaia, Reference Rzhonsnitskaya1952, Martiniopsis Waagen, Reference Waagen1883, Crassispirifer Archbold and Thomas, Reference Archbold and Thomas1985, Timaniella Barkhatova, Reference Barkhatova and Markowskii1968, Quiringites Struve, Reference Struve1992, Intermedites Struve, Reference Struve1995, Rostrospirifer Grabau, Reference Grabau1931, Otospirifer Hou and Xian, Reference Hou and Xian1975, Leonispirifer Schemm-Gregory, Reference Schemm-Gregory2010a, Thomasaria Stainbrook, Reference Stainbrook1945, and Phricodothyris George, Reference George1932 (Table 2).

Similarly, the modified group can be divided into Type-III and Type-IV according to the curvature of the modified primary lamellae. Type-III is characterized by lateral-convex primary lamellae and appears in Crurithyris and Weiningia (Table 2; Fig. 5.3, 5.15). Type-IV, having medial-convex primary lamellae, is confined to Attenuatella, Biconvexiella, Cruricella, and Orbicoelia (Table 2; Fig. 5.10, 5.13). Spiral coils are developed in Cruricella and Orbicoelia, but are reduced in Attenuatella and Biconvexiella.

Distributions and significance of brachidium

The distribution of the selected genera bearing different types of brachidium shows that more than one type of brachidium appears within the same superfamilies (Ambocoelioidea, Martinioidea, Spiriferoidea, Delthyridoidea; Fig. 6), families (Trigonotretidae, Spiriferellidae; Supplemental Table 1), and even subfamilies (Ambocoeliinae, Martiniinae, Neospiriferinae; Supplemental Table 1). Because the brachidium is a significant structure that reflects the phylogenetic relationship between and within the spire-bearing brachiopods (Copper and Gourvennec, Reference Copper, Gourvennec, Copper and Jin1996; Rong and Zhan, Reference Rong and Zhan1996; Gourvennec, Reference Gourvennec2000), spiriferides equipped with the same types of brachidium may share a close phylogenetic relationship. Some taxa may be rearranged under the current taxonomic ranks or reclassified under new taxonomic groupings, such as those in Atrypida (Copper, Reference Copper and Kaesler2002) and Athyridida (Alvarez and Rong, Reference Alvarez, Rong and Kaesler2002) in which the brachidial morphology serves as a diagnostic character within the suprageneric groups. For example, Type-II (Ambocoelia), Type-III (Crurithyris), and Type-IV (Orbicoelia, Attenuatella, Biconvexiella, Cruricella) are present in the Ambocoeliinae. Zhang and Ma (Reference Zhang and Ma2019) described several types of cardinal process and cruralium in the Ambocoeliidae and considered them as typical features of this family. These authors also mentioned that Crurithyris lacks dorsal adminicula and its cardinalia is identical to that of many other spiriferides belonging to the Martinioidea and Reticularioidea, implying that Crurithyris may not be an ambocoelioid. Having a similar cardinalia and shell morphology to that of Crurithyris, Attenuatella, Biconvexiella, Cruricella, and Orbicoelia may also be excluded from the Ambocoeliidae and exhibit a different evolutionary lineage (Zhang and Ma, Reference Zhang and Ma2019). The different brachidia in Attenuatella, Biconvexiella, Crurithyris, Cruricella, and Orbicoelia compared to Ambocoelia again bring the taxonomic positions of these taxa within the Ambocoeliidae into question. The Martiniinae is another noteworthy example for bearing Type-I (Martinia) and Type-III brachidia (Weiningia), which display significant differences from each other in terms of the configuration of the jugal processes and types of primary lamellae. However, it is difficult to determine whether the difference in brachidial morphology is of phylogenetic significance at the current time because the examined taxa only make up a small part of this order, even within the selected superfamilies.

Figure 6. Stratigraphic ranges and types of brachidium of the selected taxa. Note that more than one type of brachidium appears in Ambocoelioidea, Martinioidea, Spiriferoidea, and Delthyridoidea, and that only one type in Cyrtioidea, Theodossioidea, Cyrtospiriferoidea, and Reticularioidea may result from limited taxa considered.

Evolutionary relationship between brachidia

The similarities between different types of brachidia, especially Type-I and Type-II, and Type-III and Type-IV, make it possible to investigate their evolutionary relationship. Type-I represents the oldest type of brachidium and first appeared in Eospirifer praecursor Rong, Zhan, and Han, Reference Rong, Zhan and Han1994 in the late Katian of the Ordovician (Rong et al., Reference Rong, Zhan and Han1994; Zhan et al., Reference Zhan, Liang, Meng, Gutiérrez-Marco, Rábano and García-Bellido2011, Reference Zhan, Jin, Liang and Meng2012). According to Rong and Zhan (Reference Rong and Zhan1996), the morphologies of the crura and brachidium of E. praecursor (i.e., short crura, jugal processes, posterolaterally directed spiralia with few whorls) are similar to those of the early atrypide Cyclospira Hall and Clark, Reference Hall and Clarke1893, which bears ventrally arched crura, and small spiralia with few whorls and no jugum (Copper, Reference Copper1986), indicate that Eospirifer may have a close phylogenetic relationship with early atrypides. Type-I did not undergo considerable change from the Late Ordovician through to the end of the Permian (Fig. 7). The lack of Type-I in the interval from the Givetian to the early Famennian of the Devonian may be the result of the limited taxa considered (Fig. 6).

Figure 7. Speculative evolutionary pattern of brachidia in Order Spiriferida.

With the first appearance at the beginning of the Devonian, Type-II, which existed until the end of the Permian (Figs. 6, 7), was likely derived from Type-I by loss of the jugal processes during the Late Ordovician to the beginning of the Devonian. In subsequent periods, Type-II may revert to Type-I by regaining the jugal processes if the jugal process development could occur independently in different superfamilies (Fig. 6). As a vestigial trace of the jugum in the ancestries of Spiriferida, the subdivision of the normal group into Type-I and Type-II is subjective merely based on the presence/absence of the jugal process, which is probably of very limited phylogenetic value.

The modified group exhibits more significant brachidial innovation. Type-III appears in Crurithyris and Weiningia, with the former ranging from the Late Devonian to the Permian and the latter restricted to the late Early Carboniferous (Fig. 6). Type-IV is found in Attenuatella, Biconvexiella, Cruricella, and Orbicoelia, among which Cruricella first appeared in the Late Carboniferous and existed until the Early Triassic, whereas the others are confined to the Permian (Fig. 6). Although some taxa bearing the same brachidial type are not phylogenetically related, the morphology and stratigraphic distribution of different brachidial types clearly show a temporal trend from the normal brachidia to the modified ones (Fig. 7), suggesting that the latter was derived from the former. Because the modified brachidia are closely associated with the prolongation of crura, it is necessary for Type-II to achieve two prerequisites before evolving the modified brachidia, namely elongation of the crura and enlargement of the first whorls of the spiralia. These features already appeared independently in some Middle Devonian ambocoeliides, such as the prolonged crura in Echinocoelia Cooper and Williams, Reference Cooper and Williams1935, and the disproportionately enlarged first whorls of spiralia in Ladjia sp. and “Emanuella” meristoides Meek, Reference Meek1867 (Caldwell, Reference Caldwell and Oswald1968; Ma, Reference Ma2009; Fig. 5.8, 5.9). Crurithyris is the oldest genus with the Type-III brachidium, which likely originated from Type-II by simple lateroventral bending of the primary lamellae. The brachidium of Weiningia, on the other hand, could have evolved from one morphologically similar to that of Crurithyris by developing the more complex lateral-convex primary lamellae. The similarity in brachidial morphology between Crurithyris and Weiningia does not indicate their phylogenetic relationship, but rather a similar ecological adaptation on the feeding mechanism.

Type-IV originated either from Type-II by evolving the medial-convex primary lamellae and placing them anteriorly to the spiral cones, or from Type-III similar to that in Crurithyris through the change of primary lamellae from lateral-convex type to medial-convex type only (Fig. 7). The latter seems more convincing because these genera bearing Type-IV brachidia are phylogenetically closely related to Crurithyris, and the brachidial morphology of Cruricella is very similar to that of Crurithyris except for the initial direction or course of the primary lamellae. Such morphological change can be achieved in the secretion and resorption processes controlled by the sheathed outer epithelium during growth of the brachidia (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Brunton, MacKinnon and Kaesler1997b) to produce the simplest Type-IV brachidium, as in Cruricella from that in Crurithyris.

The complex medial-convex primary lamellae, appearing as S-shaped curvatures in Attenuatella, Biconvexiella, and Orbicoelia, were derived from those of Cruricella subsequently. In this case, the similarity in brachidial morphology among these ambocoeliines reflects not only a similar ecological adaptation on the feeding mechanism, but also their phylogenetic relationship. The brachidia in Orbicoelia, Attenuatella, and Biconvexiella represent two evolutionary lineages from Cruricella, with the spires maintained in Orbicoelia and reduced or lost in Attenuatella and Biconvexiella (Fig. 7).

The possible evolutionary lineage between different brachidia within Spiriferida may, in part, reflect the modification in the feeding system by improving the flexibility of the lophophores (through poorly developed/loss of jugal processes, loss of spiral coils) and a change in the mouth location (as shown by prolonged crura). In contrast to atrypides and athyridides, which have complex evolutionary modifications of the jugal structures (Alvarez and Rong, Reference Alvarez, Rong and Kaesler2002; Copper, Reference Copper and Kaesler2002; Guo et al., Reference Guo, Sun and Baliński2015), the jugal processes in Spiriferida exhibit a trend of stagnant development or complete loss. Although the function of the jugal structure in the lophophore remains uncertain, Copper (Reference Copper and Kaesler2002) inferred that the absence of the jugum in large atrypides of Siluro-Devonian age may suggest that a complete jugum was vulnerable and liable to breakage in the case of growing sizes of spiralia, while separate jugal processes allowed greater flexibility in the spiralia. This may suggest an analogous evolutionary trend of losing jugal processes in Spiriferida to improve the mobility and flexibility of the spiralia. As a vestigial feature, the presence/absence of the jugal process could be less important in improving the feeding system because Type-I and Type-II brachidia in the normal group are very similar in morphology.

On the other hand, Type-III and Type-IV brachidia are closely associated with prolongation of the crura, indicating not only a change in morphology of the brachidia but also a possible change in the position of the esophagus. The crura grow forward on either side of the esophagus to connect with the anterior body wall and posterior part of the lophophore on either side of the mouth in living brachiopods, therefore all processes so named in fossil rhynchonellides, terebratulides, and many spire-bearing brachiopods are thought to perform a similar function (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Brunton, MacKinnon and Kaesler1997b). If so, the prolongation of crura in the modified group would indicate a displacement of the mouth to the anterior part of mantle cavity, accompanied by the forward extension of the esophagus along the dorsal mantle lobe (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Relationship between the supposed mouth position and brachidial types in the spiriferides. (1, 2) Mouth opened in body wall posterior to the mantle cavity in taxa with normal brachidium (Type-I and Type-II); (3, 4) mouth opened at anterior part of the mantle cavity through the dorsal mantle lobe in taxa with modified brachidium (Type-III and Type-IV); (5, 6) restoration of the lophophore on the modified primary lamellae (lateral-convex and medial-convex) of the spiralia in relation to the feeding current system in modified group.

Modification of the brachidia (as in Type-III and Type-IV brachidia) may be fossil evidence of evolutionary change in the soft body of the brachiopod. Since many studies and experimental models strongly suggested that the feeding current systems in the fossil spire-bearing brachiopods with laterally tapered spiralia consisted of medially inhalant current and laterally exhalant currents (Manceñido and Gourvennec, Reference Manceñido and Gourvennec2008; Shiino et al., Reference Shiino, Kuwazuru and Yoshikawa2009; Shiino and Kuwazuru, Reference Shiino and Kuwazuru2011), the anterior-positioned mouth would get food particles quickly from the inhalant current at the anterior gape. The modified primary lamellae with the ciliated tentacles would serve as a pair of almost vertical, face-to-face, or semicircular loops to adjust or regulate the feeding currents delicately. Thus, Type-III and Type-IV brachidia represent an innovative modification of their feeding apparatus. As for the brachidia of Attenuatella and Biconvexiella, the loss of spiral coils probably reflects the presence of a flexible lophophore similar to that in the extant spirolophe-bearers, assuming that the lophophore was not restricted to this reduced brachidium. The brachidia of Attenuatella and Biconvexiella may represent an evolutionary trend towards mobile feeding organs without the support of spiralia. This unsupported lophophore may have extended out of the shell and captured food particles like the modern rhynchonellides Notosaria nigricans Sowerby, Reference Sowerby1846 (Hoverd, Reference Hoverd1985).

Conclusions

The variations of each component of brachidia in Spiriferida, namely the primary lamellae and the subsequent spires, are similar to the degree of variation in the other spire-bearers. Based on the configuration of the jugal processes (presence/absence), spiral coils (presence/absence), and types of primary lamellae (normal/lateral-convex/medial-convex), two groups composed of four types of brachidium are recognized. The normal group dominates in the studied taxa and is featured by normal primary lamellae and the presence of spiral coils, whereas the modified group occurs in a small number of taxa and is characterized by modified primary lamellae and the absence of jugal processes. In terms of the configuration of the jugal processes, the normal group is divided into Type-I (with jugal processes) and Type-II (without jugal processes). The modified group also consists of two types of brachidium, characterized by the presence of lateral-convex primary lamellae in Type-III and medial-convex ones in Type-IV.

The distributions of these types of brachidia within Spiriferida are variable, with more than one type present within the same suprageneric groups. Although it is worth considering the taxonomic significance of the brachidium within Spiriferida, given that this structure is regarded as an important diagnostic characteristic in the other spire-bearing brachiopods, it is challenging to incorporate a phylogenetic analysis to discuss this issue in detail due to limited taxa. Therefore, more detailed brachidial information in different taxa is needed. In addition, the similarities between different types of brachidia also make it possible to investigate their phylogenetic relationships. Type-II was probably derived from Type-I through loss of the jugal processes, and it could conversely give rise to Type-I by re-evolving the jugal processes in subsequent periods. Type-III may have evolved from Type-II through forming lateral-convex primary lamellae. The brachidium of Cruricella, one of the Type-IV brachidia, possibly originated from the brachidium of Crurithyris, one of the Type-III brachidia, through changing the orientation of primary lamellae during development. This simplest brachidium among Type-IV evolved into more complex forms in Orbicoelia (with spires) and Attenuatella and Biconvexiella (without spires).

The modified brachidia, closely associated with the prolongation of crura, represents an innovative modification of their feeding apparatus, possibly corresponding to the mouth shifting towards the anterior. The anterior-positioned mouth could help the creatures ingest food particles more rapidly and efficiently from the inhalant current at the anterior gape, and the modified primary lamellae could adjust/regulate the feeding currents and gather the food particles through the ciliated tentacles on these structures. The loss of the spires in Attenuatella and Biconvexiella probably suggests the evolution of a flexible lophophore without the support of spiralia, similar to extant spirolophe-bearing taxa. This unsupported lophophore could have extended out of the shell and captured food particles.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to M.A. Torres-Martínez and S. Lee for their careful reviews and constructive comments, which greatly improved the manuscript. The authors also thank A. Baliński for improving the manuscript. This research was supported by a National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) grant (No. 41772015).

Accessibility of supplemental data

Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.2fqz612n5.