Recent years have seen a troubling rise in reports of assault, intimidation, and abuse directed at female politicians (Krook Reference Krook2018a). Bolivia was the first state to respond with legal reforms, passing a law criminalizing political violence and harassment against women in 2012. In 2016 and 2017, global and regional organizations began to raise awareness and take action: the National Democratic Institute (NDI) launched the #NotTheCost campaign to stop violence against women in politics; the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) undertook a global study of sexism, violence, and harassment against female members of parliament (MPs); and the Inter-American Commission of Women published a model law to combat violence against women in political life. In 2018, the #MeToo movement led to the suspension or resignation of male MPs and cabinet ministers in North America, Western Europe, and beyond.

Available statistics indicate that violence against women in politics is not uncommon. The IPU finds that, globally, nearly all female MPs have experienced psychological violence in the course of their parliamentary work. Approximately one-third have suffered economic violence, one-quarter some type of physical violence, and one-fifth some form of sexual violence (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2016, 3). These patterns are confirmed at country and local levels. Of 425 women who ran for office in Malawi in 2009, 225 quit before the elections were over because of harassment and intimidation (Semu-Banda Reference Semu-Banda2008). In Afghanistan, nearly all female candidates interviewed in the 2010 elections had received threatening phone calls (National Democratic Institute 2010). In Peru, 41% of female mayors and local councilors had been subjected to violence (Quintanilla Reference Quintanilla2012). In Bolivia, 70% of women had been victims of violence more than once (Rojas Valverde Reference Rojas and Eugenia2012).

Despite emerging global attention, several conceptual ambiguities remain regarding the contours of this phenomenon. First, definitions used by NDI and the IPU focus on women, suggesting that these acts target women because of their gender—but without comparing their experiences to those of men (Krook Reference Krook2017). Second, terminology varies. UN Women and the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) highlight violence against women in elections, rather than in political life, whereas debates in Latin America distinguish between political violence and harassment. Finally, sources diverge in recognizing different forms of violence: the Bolivian law names two, IFES identifies three, and the IPU lists four.

This article seeks to resolve these ambiguities to lay the foundations for improved global research and programming. To make the concept of “violence against women in politics” more theoretically, empirically, and methodologically robust, we draw on literatures in multiple disciplines, a large collection of new stories and practitioner reports, and interviews we conducted in Asia, Latin America, North Africa, Western Europe, and sub-Saharan Africa between 2014 and 2018. In the first section, we propose that the presence of bias against women in political roles distinguishes this phenomenon from political violence and violence against politicians. We argue that violence against women in politics originates in structural violence, is carried out through cultural violence, and results in symbolic violence against women.

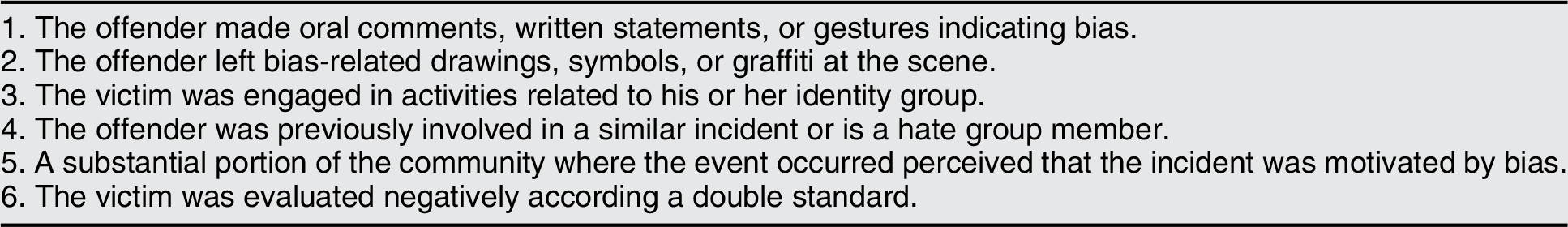

The second section maps empirical manifestations, emphasizing continuities across a broad range of behaviors falling under the umbrella of violence against women in politics. Recognizing that definitions of violence are contested, however, we introduce a distinction between violence, the use or threat of use of force, and harassment, the creation of a hostile work environment. We combine research and practitioner work on political violence and violence against women to identify four types: physical, psychological, sexual, and economic. Based on trends in women’s experiences emerging in our news and interview data, we theorize one additional form: semiotic.

The third section addresses methodological challenges in studying this phenomenon: the problem of underreporting, the value of comparing men’s and women’s experiences, and the need to take intersectionality into account. Seeking to resolve these issues, the fourth section considers how to identify cases of violence against women in politics. Inspired by the literature on hate crimes, we present six criteria to help ascertain whether an attack was potentially motivated by bias.

To illustrate how these elements might inform empirical analysis, the fifth section applies our framework to three cases: the assassination of Benazir Bhutto, the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff, and the murder of Jo Cox. These acts targeted female politicians performing their political roles and as such ultimately violated their political rights. Based on our framework, we determine that the Rousseff and Cox cases constitute examples of violence against women in politics, but the Bhutto case does not. Ambiguities in the Cox data, in particular, show why a bias event approach is crucial for judging the broader significance of a given case. The final section outlines the negative implications of violence against women in politics and discusses emerging solutions around the globe.

Theorizing the Phenomenon

Political scientists have long been troubled by political violence, defining it as the use of force— or threatened use of force—to achieve political ends (Della Porta Reference Della Porta1995). It poses a challenge to democracy when one side gets “its way through fear of injury or death,” rather than “through a process in which individuals or groups recognize each other… as rational interlocutors” (Schwarzmantel Reference Schwarzmantel2010, 222). Recent studies on violence against politicians and on violence against women in politics extend this agenda to consider threats and intimidation toward those who run for and hold political office. Similar to existing work on political violence, these literatures show how violent tactics seek to distort the collective will, with added impact when they specifically target members of particular groups.

Violence against Politicians

Violence against politicians has captured the attention of both practitioners and scholars working across disciplines. The IPU Committee on the Human Rights of Parliamentarians recently renewed its efforts to pressure governments to investigate murders and disappearances and achieve redress for MPs unduly excluded from their mandates (Inter-Parliamentary Union 2018). Governments have also taken a keener interest in this issue. In 2015, the Italian parliament commissioned a survey of murdered politicians. In 2017, British prime minister Theresa May called for a review of abuse and intimidation of candidates, and the Swedish government launched a plan to tackle threats and hate directed at officeholders.

Most academic research on this topic has been conducted by forensic psychiatrists studying “aggressive/intrusive” behaviors toward public figures, including physical attacks, threats, stalking, property damage, and inappropriate communications. Between 80% and 90% of MPs in New Zealand and the UK report experiencing at least one of these forms of harassment (Every-Palmer, Barry-Walsh, and Pathé Reference Every-Palmer, Barry-Walsh and Pathé2015; James et al. Reference James, Farnham, Sukhwal, Jones, Carlisle and Henley2016). More than one-quarter of Canadian politicians described these intrusions as “frightening” or “terrifying” (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Hazelwood, Pitre, Bedard and Landry2009, 807), and more than 40% of British MPs increased their security measures at home and work as a result (James et al. Reference James, Farnham, Sukhwal, Jones, Carlisle and Henley2016, 186). For these scholars, intrusive behaviors “stand apart from what might be seen as the MP’s working role” when they “interfere with his or her function, or cross the border into what is perceived as threatening” (178).

Political scientists and economists have taken a different approach, seeking to explain when, why, and how groups use violence against politicians—and with what effects. Evidence from Italy indicates that violence is most likely to occur after elections to influence policy, rather than being committed before elections to affect electoral outcomes. It is usually directed at local politicians and most often takes the form of arson and threatening letters (Daniele and Dipoppa Reference Daniele and Dipoppa2017). Its aim is generally to provoke their removal or render them less effective in pursuing agendas that the group dislikes (Dal Bó, Dal Bó, and Di Tella 2003). Country factors may facilitate such violence; for example, in Mexico the number of narco-assassinations has increased since 2005 as a result of growing criminal fragmentation and political pluralization (Blume Reference Blume2017).

Gender features in only a marginal way in these literatures, despite observations in passing that the majority of perpetrators are male (James et al. Reference James, Farnham, Sukhwal, Jones, Carlisle and Henley2016) and that murdered politicians also tend to be male (Daniele Reference Daniele2017). Yet incorporating a gender lens into the study of violence against politicians does more than just highlight the gendered identities of victims and perpetrators. It also points to a related but distinct phenomenon, whereby the origins, means, and effects of violent acts specifically aim to exclude women from the political sphere, disrupting the political process as a means of reinforcing gendered hierarchies.

Violence against Women in Politics

In September 2017, British MPs held a debate on the abuse and intimidation of political candidates, agreeing that the problem affected all parties and posed a serious problem for democracy. Yet, numerous interventions in the debate by both male and female MPs noted that women were often specifically targeted. Work on online abuse makes a similar observation: whereas “generic trolls” aim to annoy, upset, or anger people, “gender trolls” engage in harassing and threatening behaviors—often using graphic sexualized and gender-based insults—to inspire fear and drive women to withdraw from online discourse (Mantilla Reference Mantilla2015). Although the technology is new, maligning a woman’s character, often by reference to her sexuality, has been a recurring strategy historically to discredit women’s ideas and inhibit their participation in traditionally male-dominated spaces (Spender Reference Spender1982).

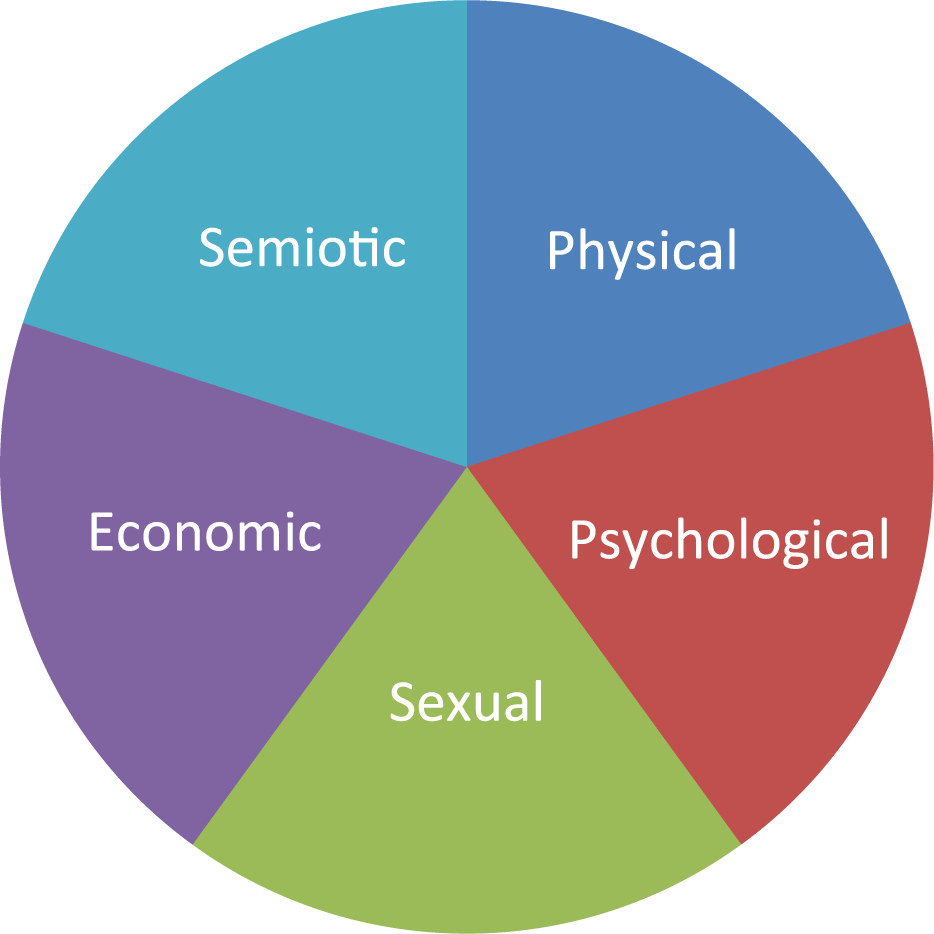

Violence against women in politics thus entails violations of both electoral and personal integrity (Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2018). It stems from misogyny, a system that polices and enforces patriarchal norms and expectations. Misogyny distinguishes between “good” and “bad” women, punishing the latter for perceived violations of appropriate gender roles (Manne Reference Manne2018). Political scientists have largely overlooked this phenomenon because they tend to define violence in a minimalistic way, as an act of force. Sociologists and many feminist theorists, in contrast, tend to define violence more comprehensively as an act of violation (Bufacchi Reference Bufacchi2005), thereby uncovering behaviors that otherwise remain hidden or “naturalized.” Inspired by this work, we propose that violence against women in politics originates in structural violence, is perpetrated through cultural violence, and results in symbolic violence against women (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Violence against women in politics

Violence against women in politics begins with structural violence, involving the stratification of access to basic human needs based on ascriptive group membership. Built into the social structure, this stratification enacts harm in the form of unequal life chances (Galtung Reference Galtung1969), “leav[ing] marks not only on the human body but also on the mind and the spirit” (Galtung Reference Galtung1990, 294). The structural origins of women’s political exclusion stem from ancient and modern political theories associating men with the public sphere and women with the private (Okin Reference Okin1979). This divide limits women’s mobility even in countries where women’s movement in public spaces is not legally restricted. Structural violence inspires and rationalizes hostility against women leaders stemming from their perceived status violations (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002).

Cultural violence provides the means for perpetrating violence against women in politics. It refers to cultural norms used to justify mistreatment, thereby “changing the moral color of an act from red/wrong to green/right or at least to yellow/acceptable” (Galtung Reference Galtung1990, 291). Rooted in dynamics of structural violence, cultural violence creates a double standard by tolerating violence when perpetrated against members of particular groups. Rape myths are one form: blaming survivors, they suggest that rapes are provoked by women’s personal choices in clothing and behavior (Suarez and Gadalla Reference Suarez and Gadalla2010). Sexist jokes are another form of cultural violence, expressing antagonistic attitudes toward women under the guise of “benign amusement” (Ford Reference Ford2000). Sexual objectification is a third common vehicle, reducing women to physical attributes and thereby denying their competence and full emotional and moral capacity (Heflick and Goldenberg Reference Heflick and Goldenberg2011).

Symbolic violence is the intended outcome of violence against women in politics. According to Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu2001), masculine domination is the quintessential form of symbolic violence, seeking to put women who deviate from prescribed norms back “in their place.” What makes symbolic violence so powerful is “misrecognition,” whereby the “dominated apply categories constructed from the point of view of the dominant to the relations of domination” (35). These dynamics can be seen in cases of sex-based harassment: men and women alike may punish individuals who deviate from gender norms to defend their own status in the existing system of gender hierarchy (Berdahl Reference Berdahl2007). Backlash against agentic women maintains stereotypes and rewards perpetrators psychologically, increasing their self-esteem (Rudman and Fairchild Reference Rudman and Fairchild.2004).

Mapping Empirical Manifestations

A minimalist conception of violence as force focuses on the deliberate infliction of physical injury, highlighting the intentions of agents who commit acts of violence at single moments in time. In contrast, a more comprehensive view of violence as violation recognizes a wider range of transgressions, privileging the experiences of victims and the temporally indeterminate “ripples of violence” affecting survivors, their families, and society (Bufacchi Reference Bufacchi2005; Bufacchi and Gilson Reference Bufacchi and Gilson2016). Reflecting the latter approach, research and activism on violence against women go beyond physical violence to emphasize a continuum of violent behaviors (Kelly Reference Kelly1988).

International and national frameworks thus enumerate various forms of violence against women. Article 2 of the 1993 UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women names physical, sexual, and psychological violence, to which Article 3 of the 2011 Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention adds economic violence. World Bank data from 189 countries indicate that all four forms appear in national laws, with varying degrees of recognition: physical violence is criminalized in 137 states, psychological violence in 134, sexual violence in 106, and economic violence in 86 (World Bank 2016).

We propose two modifications to these prevailing frameworks. First, recognizing that political scientists without a foundation in gender studies may hesitate to adopt a broad concept of violence, we propose retaining the umbrella concept of violence against women in politics, under which we can distinguish between acts of violence, involving the use of force, and harassment, actions creating a hostile work environment. Second, we theorize a fifth form of violence against women in politics, semiotic violence, which captures dynamics not reducible to the four other types. Figure 2 illustrates how the five types of violence form part of the same field of behaviors, but may nonetheless be distinguished from one another.

Figure 2 Types of violence against women in politics

Physical Violence and Harassment

Physical violence involves efforts to inflict bodily harm and injury. In 2004, a Mexican mayoral candidate, Guadalupe Ávila Salinas, was shot dead in broad daylight by the sitting mayor while holding a meeting with women from the community (Jarquín Edgar Reference Jarquín Edgar2004). Other women have been kidnapped, such as Afghan MP Fariba Ahmadi Kakar, who was abducted by Taliban rebels in 2013 (Graham-Harrison Reference Graham-Harrison2013), or severely beaten, as was Kenyan parliamentary candidate Flora Terah in 2007 (Terah Reference Terah2008).

Physical harassment entails touching, jostling, or other forms of unwelcome physical proximity, as experienced by an activist in Uganda who was stripped naked by police at a party rally in 2015. It might also involve involuntary confinement; for example, a candidate in Tunisia was locked in her home by her husband to prevent her from attending a campaign event.Footnote 1 The tangible nature of physical acts makes them the most widely recognized and least contested forms of violence against women. They tend to be relatively rare, however, with perpetrators opting for “less costly” means of violence and harassment before escalating to physical attacks.

Psychological Violence and Harassment

Psychological violence inflicts trauma on individuals’ mental state or emotional well-being. Examples include death and rape threats, carried out in person or online. Laura Boldrini, speaker of the Italian parliament, received bullets in the mail, saw “Death to Boldrini” scrawled on city walls, and was burned in effigy (Feder, Nardelli, and De Luca Reference Feder, Nardelli and De Luca2018). Rape threats against British MP Jess Phillips on Twitter became so common that she was forced to block her Twitter accounts and report the abuse to police.Footnote 2

Psychological harassment occurs inside and outside of official political settings. Malalai Joya, an Afghan MP, was called a prostitute and had water bottles thrown at her in parliament; in 2007 she was ejected by a show of hands, in violation of official procedures for suspending an MP (EqualityNow 2007). Ayaka Shiomura, a Japanese local councilor, was taunted by male colleagues, who yelled “Go and get married” and “Can’t you give birth?” at her while she was making a speech on increasing the number of women in the workforce (Lies Reference Lies2014). In Sierra Leone, men in secret societies have sought to scare off female candidates (Kellow Reference Kellow2010).

Sexual Violence and Harassment

Sexual violence comprises sexual acts and attempts at sexual acts by coercion. Stigma prevents many women from coming forward to report their experience of sexual violence. For example, it was only in 2014, during debates on sexual violence in Canadian politics, that former deputy prime minister Sheila Copps disclosed she had been sexually assaulted by a male provincial parliament colleague in 1980 (CBS News 2014). In 2016, Monique Pelletier revealed she was assaulted by a male senator in 1979 while serving as the French minister of women’s rights.Footnote 3

Sexual harassment entails unwelcome sexual comments or advances. In recent years, elected men who have lost their positions because of such allegations include Mbulelo Goniwe, chief whip for the African National Congress party in South Africa in 2006; Massimo Pacetti and Scott Andrews, Liberal MPs in Canada in 2014; Silvan Shalom, interior minister of Israel in 2015; and Denis Baupin, vice president of the French National Assembly in 2016 (Krook Reference Krook2018b). The rise of the #MeToo movement in 2017 has accelerated similar disclosures in countries as diverse as Britain, Canada, Korea, Russia, and the United States.

Economic Violence and Harassment

Feminists theorize economic violence as abuse seeking to deny or control women’s access to financial resources (UN Women/UNDP 2017, 17), whereas definitions of electoral violence include injuries inflicted on “person or property at any stage of the long electoral cycle” (Norris, Frank, and Martínez i Coma Reference Norris, Frank and i Coma2014, 9). We define economic violence as property damage, ranging from petty vandalism to attempts to undermine a woman’s economic livelihood. Extremists defaced and tore down women’s campaign posters in Iraq (Abdul-Hassan and Salaheddin Reference Abdul-Hassan and Salaheddin2018), and British MP Angela Eagle had a brick thrown through the window of her constituency office (Perraudin Reference Perraudin2016). In India, the land and crops of a local councilor were destroyed (Asian Human Rights Commission 2006).

Economic harassment involves withholding economic resources to reduce women’s capacity to perform their political responsibilities. In Bolivia, local officials refused to pay the salaries of elected women (Corz Reference Corz2012), and in Peru, the husband of a local councilor prevented her from having access to the family’s money after she was elected (Quintanilla Reference Quintanilla2012). In Costa Rica, El Salvador, Mexico, and Peru, locally elected women, but not their male colleagues, were denied offices, telephones, and even travel expenses (Krook and Restrepo Sanín Reference Krook and Restrepo Sanin2016).

Semiotic Violence and Harassment

Semiotic violence is perpetrated through degrading images and sexist language (Krook Reference Krook2019). Sexual objectification is one strategy of semiotic violence. After the election of Croatian president Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović in 2015, national news outlets published stills from an alleged sex tape of her; in 2016, photos supposedly of her wearing a bikini went viral (“OK Ladies” 2016).

Symbolic annihilation is another strategy. This concept, which was developed in media studies, proposes that excluding or trivializing particular groups transmits a message about the societal value of the members of those groups (Klein and Shiffman Reference Klein and Shiffman2009). Symbolic annihilation occurs in politics in at least two ways. First, opponents seek to erase women as actors in the political imagination. In 2009, ultra-Orthodox newspapers in Israel altered photos of the cabinet to exclude its female members (Huffington Post Reference Huffington Post2009). Second, rules of language and grammar are deployed to resist gendered transformations. In 2014, a conservative male MP in France repeatedly addressed the president of the National Assembly as Madame le Président (using the masculine form of “president”), despite her telling him multiple times to use Madame la Présidente, the feminine form (Cotteret Reference Cotteret2014).

A third strategy is to employ highly negative gendered language to characterize female politicians and their behaviors. Misogynistic merchandise featuring slogans like “Trump That Bitch!” was widely sold at Donald Trump rallies during the 2016 U.S. presidential elections (Bellstrom Reference Bellstrom2016), and Trump famously called Hillary Clinton “a nasty woman” during the final presidential debate. In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte described Senator Leila de Lima as “immoral” and an “adulterer” when she challenged his leadership, actions that female colleagues condemned as “slut-shaming” (Sherwell Reference Sherwell2016).

Interrelated Violence

Analytically distinguishing between these five types does not mean that they are clearly distinct in practice. Sexual assault, for example, may have both physical and psychological components. Similarly, when distributed to a larger public, photoshopped images constitute semiotic violence; when sent to the woman in question, they entail psychological and sexual harassment. These overlaps do not undermine our classification, we argue, but rather bolster the case for thinking about these acts as part of a shared field of practices. Interrelations are perhaps best illustrated, however, by cases where different forms of violence appear in an escalating pattern over time.

For Juana Quispe, a local councilor in Bolivia, psychological and economic harassment culminated in physical violence. Even though Quispe and her male party colleagues were critical of the mayor, she was singled out for mistreatment. The mayor, his supporters, and various local councilors first pressured her to resign. When she did not do so, they changed the council’s meeting times and refused her entrance to the sessions. They then falsely accused her of corruption, suspending her from her position. She waged a seven-month legal battle that resulted in her being reinstated, but the council then denied her a salary for those seven months, arguing that she had not attended its sessions. One month later, she was murdered (Corz Reference Corz2012).Footnote 4

Tackling Methodological Challenges

Documenting violence against women is notoriously difficult. Many women are reluctant to report violence because of feelings of shame and stigma, fear of retaliation, and perceived impunity for perpetrators (Palermo, Bleck, and Peterman 2014). Normalized in many societies, violence against women is rarely seen as a problem in need of intervention. In the case of violence against women in politics, political dynamics further disincentivize speaking out. Additionally, calls to incorporate gender and intersectionality raise questions about the robustness of research if men are not included as subjects and how diversity among women should be recognized and taken into account.

Reporting Instances of Violence

Perhaps the number one barrier to studying this phenomenon is the tendency to dismiss violence as “the cost of doing politics.” While some of this resistance appears to stem from a hesitance to be viewed as “victims,” many elected women acknowledge that female colleagues have been targeted for gender-based violence (Cerva Cerna Reference Cerva Cerna2014).Footnote 5 A best practice strategy for collecting statistics on violence against women is to avoid the word “violence,” giving rise to varied subjective interpretations, in favor of asking a list of questions about specific acts (United Nations 2014). Using this approach, the IPU (2016) finds that violence and harassment against women parliamentarians is widespread.

Silence on these issues is not merely a cognitive question, however. It may also be a strategic decision. In interviews, women admit frankly that speaking out would be a form of “political suicide.”Footnote 6 One reason is that most perpetrators are members of the woman’s own political party (National Democratic Institute 2018; UN Women 2014). Insiders may justify suppressing women’s accounts out of concerns about negative publicity that could be exploited at election time. Another concern is that women may believe that it will reflect badly on themselves, as in Tanzania where demanding sexual favors for political positions is widespread.Footnote 7 Silence may also be the result of staff decisions to read and delete abusive correspondence, so that MPs are not fully aware of the extent of harassment (Committee on Standards in Public Life 2017).

In cases where women are willing to speak out, moreover, it is rarely clear to whom they should report. In 2014, sexual harassment allegations against Canadian MPs from different parties led to the discovery that there were no procedures in place to handle such claims.Footnote 8 In the wake of the #MeToo movement, women in several countries have created anonymous reporting mechanisms to fill this gap.Footnote 9 In Mexico, where the problem is well recognized but no legal framework yet exists, women have lodged complaints with diverse state institutions.Footnote 10 Opening up about sexual violence or harassment may backfire, however, causing female politicians to be portrayed as overly emotional, as occurred after Australian prime minister Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech in parliament in 2012 (Wright and Holland Reference Wright and Holland.2014). Women may also simply not be believed: when Kim Weaver stood down as a candidate in an Iowa congressional race against incumbent Steve King, citing “very alarming acts of intimidation, including death threats,” he tweeted in response, “Death threats likely didn’t happen but a fabrication” (Fang Reference Fang2017).

Comparing Men’s and Women’s Experiences

A second challenge in studying this topic stems from calls to take “gender” seriously in political research. Some scholars argue that it is vital to study men and women together, recognizing that men are gendered beings and that comparison is essential for ascertaining whether or not gender plays a role (Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2018). Bolstering the case for this approach, a review by IFES of its electoral violence data finds that men are more often victims of physical violence, whereas women are more likely to face psychological violence (Bardall Reference Bardall2011). Some male politicians have also been targeted for gender-based attacks: Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man to hold public office in the United States, was assassinated in 1978 by an antigay colleague.

Emphasizing that men also experience gender-based political violence, however, risks theorizing a false symmetry between men’s and women’s experiences. Within the broader field of violence against women, emphasis on the fact that most victims of gender-based violence are women gave rise to a counternarrative—based not on facts but driven by broader political agendas—claiming that men and women were equally victims and perpetrators of domestic violence. This equivalence perspective, however, is easily disproved when types and severity of violence are taken into account (Berns Reference Berns2001).

In the political world, some male politicians do claim to be equally or more abused than their female counterparts.Footnote 11 Yet many male MPs reject the notion of equivalence; for example, British MP Martin Whitfield stated, “I fully accept that my experience… is but a mere toe in the water compared with the vile abuse received by other…Members, especially women.”Footnote 12 Focusing on mere numbers also can distort perceptions of gender and political violence. A study of mafia assassinations of Italian mayors observes that all victims were male, without noting that women are severely underrepresented in these positions.

Taking Intersectionality into Account

The emphasis on violence against women in politics, finally, seems to suggest that gender is the only source of abuse. However, the concept of intersectionality theorizes that different facets of identity interact to shape life opportunities and experiences (McCall Reference McCall2005). Although intersectionality has not yet been incorporated widely into theorizing about violence against women in politics (Kuperberg Reference Kuperberg2018), it is present in news coverage and emerging data on this phenomenon. An analysis of Twitter abuse against female MPs in the United Kingdom finds that nearly half of the abusive tweets were directed at Diane Abbott, the first black woman to be elected to the British parliament; when Abbott was taken out of the sample, black and Asian women still received 30% more abuse than their white counterparts (Amnesty International UK 2017).

These interactions are not limited to gender and race. In the United Kingdom, sexism combined with anti-Semitism against Luciana Berger, a Jewish MP, and homophobic slurs were made against Angela Eagle, the first openly lesbian MP.Footnote 13 Poor and lower-caste women are more vulnerable than other groups in India, Nepal, and Pakistan (UN Women 2014, 64-65), whereas younger women are more prone to violence and harassment according to global data from the IPU (2016). Women who challenge gender roles in multiple ways—being outspoken feministsFootnote 14 or ascending to prominent leadership positions (Davies Reference Davies2014)—also seem to experience more numerous and more vitriolic attacks. The intersectional nature of this violence, however, does not undermine bias against women as a key driver. Rather, it substantiates the intuition that structural, cultural, and symbolic violence against women and members of other marginalized groups lie at the heart of this phenomenon.

Identifying Bias Events

Due to dynamics of structural, cultural, and symbolic violence, bias against particular groups is often highly naturalized. As a result, perpetrators may not be aware of their prejudice, and targets may accept mistreatment as simply the normal course of affairs. This creates serious challenges to identifying acts of violence against women in politics. To move beyond this impasse, we draw on the hate crimes literature to conceptualize violence against women in politics as “bias events.” Translating this into a strategy for empirical research, we pull from existing legal guidance to create six indicators for identifying cases of violence against women in politics. Consistent with legal applications, this holistic approach does not require that all six criteria be met. Rather, it calls for pieces of evidence to be weighed in relation to one another to determine whether, on balance, they would support a finding of bias against women in political roles.

The Concept of Hate Crimes

Hate crime laws impose a higher class of penalties when a violent crime targets victims because of their perceived social group membership. These crimes are deemed to be more severe because they also involve group-based discrimination. Used to reassert privilege on the part of dominant groups, their impact “goes far beyond physical or financial damages. It reaches into the community to create fear, hostility, and suspicion” (Perry Reference Perry2001, 10). These “message crimes” thus aim to deny equal rights to group members and heighten a sense of vulnerability among other members of the community (Iganski Reference Iganski2001).

One critique of hate crime legislation is that it punishes “improper thinking,” violating the right to free speech (Jacobs and Potter Reference Jacobs and Potter1997). Yet the aim of these laws is to ensure that all members of society are free to exercise their civil rights without public or private interference (Weisburd and Levin Reference Weisburd and Levin1994). Perpetrators’ actions seek to diminish free speech on the part of the harassed and other members of their group (Mantilla Reference Mantilla2015).

Women have not fully benefited from existing hate crime laws because of the frequent exclusion of gender as a category (McPhail Reference McPhail2002). This stems not only from structural and cultural violence naturalizing the mistreatment of women but also from the existence of other laws on violence against women (Walters and Tumath Reference Walters and Tumath2014). A further challenge relates to the word “hate,” given that perpetrators rarely, in fact, hate all women. Manne critiques this “naïve conception” of misogyny in favor of thinking about it as a property of social systems, in which women face hostility “because they are women in a man’s world” (2018, 33; emphasis in original).

Weisburd and Levin advocate using the term “bias crime,” arguing that it more accurately captures this discriminatory, group-based hierarchical component. As civil rights violations, the hateful intent of the perpetrator is less important than the discriminatory use of violence against those who are seen as “transgressors” against their “proper role” in society (1994, 36). Focusing only on “crimes,” we argue, is also too limited. We expand our focus, therefore, to include what police in England and Wales label “hate incidents” or “any non-crime perceived by the victim or any other person, as being motivated by prejudice or hate” (Ask the Police 2018). With these modifications, we propose the umbrella concept of “bias events” as the broader category drawing lines around what does and does not constitute an act of violence against women in politics.

A bias event approach has numerous advantages over a hate crime framework for analyzing violence against women in politics. First, it avoids unduly restricting the focus to criminal behaviors, recognizing that legal standards vary across countries, as does state capacity to enforce laws. Second, this approach decenters the state and the police as the only actors relevant to tackling violence against women in politics, opening up opportunities for other actors, such as international organizations, political parties, and civil society, to be active on this issue. Third, it displaces a focus on perpetrator intentions, which can be misunderstood or denied, in favor of the perspectives and experiences of victims and society at large.

Criteria for Ascertaining Bias

To develop criteria for identifying bias events, we start with the guidelines in the FBI’s Hate Crime Data Collection Guidelines and Training Manual. The FBI notes that because it is difficult to ascertain an offender’s subjective motivation, a crime should be deemed to be motivated by bias “only if investigation reveals sufficient objective facts to lead a reasonable and prudent person to conclude that the offender’s actions were motivated, in whole or in part, by bias” (2015, 4).

These guidelines list various types of evidence that—particularly when combined—might support a finding of bias. We focus on five of these, fleshing out how they might be used to analyze potential acts of violence against women in politics and establish the presence of bias against women in political roles (see Table 1). First, the offender made oral comments, written statements, or gestures indicating bias. This might include using sexist or sexualized language—in-person, in print, or online—objectifying or otherwise denigrating women. Second, the offender left bias-related drawings, symbols, or graffiti at the scene. Perpetrators, in this case, might post degrading images of female politicians, or paint sexist insults on campaign posters, homes, or constituency offices.

Table 1 Six criteria for detecting bias

Note: All six criteria need not be met to reach a conclusion of bias.

Third, the victim was engaged in activities related to his or her identity group. Political women in this scenario might be outspoken feminists, but they may also simply have sought to speak up for women. Fourth, the offender was previously involved in a similar incident or is a hate group member. The perpetrator might have harassed other female politicians, or might participate in men’s rights networks or other groups seeking to defend patriarchy. Fifth, a substantial portion of the community where the event occurred perceived that the incident was motivated by bias.Footnote 15 Evidence for this might include speeches, opinion pieces, or demonstrations —especially by other women—which explicitly attribute the attack to a woman’s gender.

Not all acts of bias are so transparent, however. In cases of unconscious bias, people believe that they are not prejudiced, but nonetheless think or act in biased ways. Unconscious bias may appear in the form of microaggressions: everyday indignities that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative views toward members of certain groups (Sue Reference Sue2010). A more purposive approach masks prejudiced views by claiming other forms of wrongdoing, for example through “judicial harassment,” whereby individuals are targeted with baseless legal charges that divert time, energy, and resources away from their work (Frontline Defenders 2018). To detect these forms of bias, we propose a final criterion: the victim was evaluated negatively according a double standard. This might include attacking female politicians in ways and for reasons not used for male politicians.

This hate-crimes-inspired approach goes far in resolving the three methodological challenges described earlier. First, the analysis does not require that the perpetrator or victim recognize the act as an instance of violence against women in politics. Second, this approach is case based and thus does not require comparisons with other populations to establish that sexism and misogyny played a role. Third, attention to bias as a larger category enables intersectional experiences to be taken into account, while also presenting a framework for ascertaining bias against members of other marginalized groups. By emphasizing the need for analysis, finally, this approach opens up the possibility that some incidents against female politicians may not be attributable to bias.

Applying the Framework

According to a bias event approach, ascertaining the meaning of particular acts requires placing them in their broader context, using information about their content, targets, perpetrators, and impact. Consistent with the FBI handbook, this approach does not require that all six criteria be met in full. Recognizing that many cases will be ambiguous, with potentially conflicting or competing sources of information, our framework uses these criteria as guidance to explore whether, on balance, the available data would support a finding of bias. Illustrating how to gather and weigh evidence through this lens, we analyze three cases from different parts of the world to determine whether – or not – they constitute violence against women in politics.

Benazir Bhutto

Benazir Bhutto served as prime minister of Pakistan from 1988 to 1990 and 1993 to 1996. After years living abroad, she returned in October 2007 to contest parliamentary elections. Upon her homecoming, she survived an assassination attempt when her motorcade was bombed on its way to a campaign rally in Karachi, killing hundreds of bystanders. On December 27, after months of a tense political and security situation, she was killed as she stood up in her car, waving from the open sunroof, while leaving a rally at Liaquat Bagh park in Rawalpindi. The next day, the Ministry of the Interior announced the cause of death and identified who was responsible for the attack. This quick resolution raised more questions than it answered. In 2008, her widower, Asif Ali Zardari, the new Pakistani president, requested support from the UN for a fact-finding mission to establish the circumstances surrounding her assassination.

Conducting more than 250 interviews over the course of nine months, the UN team noted the lack of data available for evaluation: the crime scene was hosed down within an hour of the attack, only 23 pieces of evidence were collected, and an autopsy on the body was not permitted. The team ultimately concluded that these failures were deliberate (United Nations Committee of Inquiry 2010). After the initial arrests, police abandoned their efforts to identify the suicide bomber, leaving his motives unclear. As a result, there is no evidence regarding (1) comments, statements, or gestures and (2) drawings, symbols, and graffiti that might support a finding of gender bias. Evidence that is available, however, strongly points to political motivations for the attack: Bhutto was placed under house arrest before the assassination, there were curious security lapses on the day of her assassination, and government officials behaved suspiciously in the wake of the attacks (Farwell Reference Farwell2011; Hussain Reference Hussain2008; United Nations Commission of Inquiry 2010).

The longer trajectory of Bhutto’s career, nonetheless, provides ample testimony of hostility to her leadership due to the fact that she was a woman. When she returned to Pakistan in the late 1980s, she was constantly asked in media interviews why she was not married, leading her to consent to an arranged marriage so she could continue her political activities. In 1988, her party won the elections, but religious leaders opposed her leadership, arguing that a woman could not serve as head of an Islamic state (Zakaria Reference Zakaria1990). Empowerment of women formed a key part of her party’s manifesto, and one of her first actions as prime minister was to free many female prisoners, symbolically releasing women from the “social prisons” they had suffered during the military dictatorship (Weiss Reference Weiss1990). While this suggests she (3) was engaged in activities related to her identity group, her government subsequently failed to overturn some of the most discriminatory laws against women (Suvorova Reference Suvorova2015). By 2007, her focus on women’s issues was much reduced, appearing in the second half of her party manifesto in a mere half-page of a 22-page document (Pakistan Peoples Party 2008).

Because of the botched police investigation, many theories flourished regarding her assassins and their potential motivations. Government officials attributed the attack to Al-Qaeda. The UN team noted that Bhutto did worry that Al-Qaeda and the Pakistani Taliban might seek to harm her because of her strong stance against religious extremism. During her last few months in Pakistan, however, she came to believe that then-president Pervez Musharraf was the main threat to her safety (United Nations Commission of Inquiry 2010). She was also deeply suspicious of the military and intelligence communities, calling out by name three senior Musharraf allies whom she believed were planning to murder her (Farwell Reference Farwell2011). While she believed that the dangers were real, Bhutto was convinced that threat warnings passed to her by the government were intended to intimidate her to stop campaigning (Muñoz Reference Muñoz2014). Although Al-Qaeda and the Taliban were (4) previously involved in similar violent incidents, these additional considerations indicate that all potential suspects were driven overwhelmingly by questions of policy and political power.

In terms of (5) reactions of the community to the question of gender bias, commentary to this effect was relatively minimal. The Al-Qaeda leader accused of planning the assassination strongly denied assassinating Bhutto, explaining: “Tribal people have their own customs. We certainly don’t strike women” (Lamb Reference Lamb2010). Similarly, in an otherwise extremely detailed, single-spaced, 65-page report, the UN team devoted only one line to gendered motivations, stating that “Ms. Bhutto’s gender was also an issue with the religious extremists who believed that a woman should not lead an Islamic country” (United Nations Commission of Inquiry 2010, 49). Among the three Musharraf allies identified by Bhutto, only one was explicitly said to “not like women meddling in politics” (Farwell Reference Farwell2011, 217). Finally, the response of international leaders largely focused on violence as a threat to democracy, with gendered content restricted to noting she was a woman or calling her Ms. Bhutto (Hussain Reference Hussain2008).

Regarding whether Bhutto (6) was punished according to a negative double standard, evidence again points to a lack of gender bias. She was not the first political figure in Pakistan to die in an untimely fashion. Her father, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, who served as president and as prime minister, was executed in 1979. Even more tellingly, Pakistan’s first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, was assassinated in 1951, in the same park Bhutto was leaving as she was killed. When she arrived at the hospital after the October suicide bombing, the staff was busy treating victims of a shooting at a rival candidate’s rally earlier that day. The only discriminatory treatment uncovered by the UN team was a letter in which the Interior Ministry instructed provincial governments to provide stringent and specific security measures for two male ex-prime ministers; no similar directive was issued for Bhutto, also an ex-prime minister. The reason, however, appears to be political: both men were members of the ruling party and close allies of Musharraf (United Nations Commission of Inquiry 2010). Based on this analysis, we conclude that Bhutto’s assassination entailed political violence and violence against politicians, not violence against women in politics.

Dilma Rousseff

Dilma Rousseff was elected as the first female president of Brazil in 2011 and reelected in 2014. Her reelection was challenged by the main opposition party, and in May 2015, opposition groups presented the party with a petition to impeach Rousseff. Senior leaders did not accept this petition, although they made clear their intention to search for grounds of alleged wrongdoing (Chalhoub et al. Reference Chalhoub, Collins, Llanos, Pachón and Perry2017). In December 2015, the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Eduardo Cunha, accepted a formal denunciation claiming that Rousseff had committed administrative infractions in the presentation of government accounts and budgeting practices. The Chamber voted in April 2016 to move ahead with impeachment proceedings. Four weeks later, the Senate voted to suspend Rousseff’s powers during the trial, and her vice president, Michel Temer, became the acting president. In August 2016, the Senate removed Rousseff from office, finding her guilty of breaking the budget law.

On their face, impeachment proceedings do not appear to constitute a form of “violence,” nor do they seem like a particularly gendered form of attack. A deeper probe into this case, however, reveals patterns consistent with a bias event seeking to violate women’s political rights. Those who promoted the process and voted in favor of impeachment made numerous (1) comments, statements, or gestures indicating bias. Soon after being elected in 2010, Rousseff indicated her preference to be referred to as presidenta (the feminine form). Latin American news outlets overwhelmingly called her presidenta, as did female politicians and members of her own party. In contrast, those voting for impeachment, as well as conservative media outlets, persisted in calling her presidente, the masculine form (Dos Santos Reference Dos Santos2017). This semiotic violence was accompanied by less gendered but clearly violent language. Deputy Jair Bolsonaro notably dedicated his vote for impeachment to Colonel Carlos Brilhante Ustra, who tortured political prisoners, including Rousseff, during the military dictatorship (Chalhoub et al. Reference Chalhoub, Collins, Llanos, Pachón and Perry2017).

From the time that she first entered the political scene, Rousseff’s appearance—her age, short hair, and professional attire— were seen as an affront to traditional Brazilian standards of femininity (Encarnación Reference Encarnación2017). Emphasizing these differences, the magazine Veja published an article a day after the Chamber vote, praising Marcela Temer, the 33-year-old wife of the vice president, as “beautiful, maidenlike, and ‘of the home.’” A cover story in Isto É! magazine portrayed Rousseff as hysterical, drawing parallels with Queen Mary I of Portugal and Brazil, known as Maria a Louca (Mary the Crazy; Cardoso and de Souza Reference Cardoso, Gatto, Bellan and de Souza2016). In July 2015, members of the general public began to place stickers showing Rousseff with her legs spread apart around their gas tank openings, sexually violating her image every time they filled up (Saliba and Santiago Reference Saliba and Santiago2016). A final set of (2) bias-related drawings and symbols include signs reading Tchau, Querida! (Bye-Bye, Sweetheart!) held up on the Chamber floor by mainly male legislators, taunting Rousseff as they voted for her impeachment.

On the day she was inaugurated, Rousseff (Reference Rousseff2011) proclaimed, “My greatest commitment, I repeat, is to honoring our women, protecting our most vulnerable people, and governing for everyone.” Actions during her presidency confirm that she (3) was engaged in activities related to her identity group. She continued to advance policies for women implemented under her predecessor and expanded the government’s work to end violence against women and support women’s financial autonomy. She appointed far more women to cabinet positions than previous presidents and elevated the Secretariat on Policies for Women to the status of a full-fledged ministry (Jalalzai and Dos Santos Reference Jalalzai and Dos Santos2015). After her removal, the interim government moved immediately to reverse these gains. Temer appointed the first all-white, all-male cabinet since the military dictatorship. He collapsed the work of the women’s ministry into the Ministry of Justice, and between 2016 and 2017, he discontinued the majority of policies for women initiated under Rousseff and her predecessor (Rubim and Argolo Reference Rubim and Argolo2018).

The two other main protagonists of impeachment, Cunha and Bolsonaro, are well known for (4) their sexism and misogyny. Cunha sponsored a bill in 2013 to restrict access to abortion in cases of rape and to increase penalties for abortion. In 2015, he criticized the inclusion of “gender ideology” in the national plan of education, seeking to prohibit the use of terms like “gender” and “sexual orientation” in the classroom in favor of emphasizing “natural sexual roles” and the “natural family” (Biroli Reference Biroli2016). Bolsonaro was described by journalists in 2014 as “the most misogynistic, hateful, elected official in the democratic world” (Greenwald and Fishman Reference Greenwald and Fishman2014). In response to Congresswoman Maria do Rosário, who denounced the military dictatorship for using sexual violence against dissidents, he took the floor and stated, “I would not rape you. You don’t merit that.” The Supreme Court ruled in her favor when she filed a complaint for libel and slander, which she argued was tantamount to promoting rape culture (Carta Capital Reference Carta Capital2016).

The reaction of women suggests that (5) a substantial portion believed the impeachment was motivated by bias. In an article published in the Guardian in July 2016, one activist wrote, “Almost all feminists agree that her impeachment was sexist and discriminatory,” observing that thousands of women had come together to express solidarity with Rousseff in a “confrontation with the patriarchy, with male chauvinists” (Hao Reference Hao2016). Female politicians echoed this message. Senator Gleisi Hoffman stated that it was undeniable that misogyny played a role in the impeachment process (Chalhoub et al. Reference Chalhoub, Collins, Llanos, Pachón and Perry2017), whereas Senator Regina Sousa remarked during the trial, “The message they are sending in this process is also directed at all women. With their blocking actions they are telling us: women cannot” (Amorim Reference Amorim2016). Rousseff acknowledged this support during her speech in the Senate: “Brazilian women have been, during this time, a fundamental pillar for my resistance.… Tireless companions in a battle in which misogyny and prejudice showed their claws” (Rousseff Reference Rousseff2016).

Finally, ample evidence indicates that Rousseff (6) was punished according to a negative double standard. Her stated offense was using funds from the central bank to conceal a budget deficit before the 2014 elections, which she later reimbursed. This budgetary practice, known in pedaladas fiscais, was made illegal in 2000, but had been employed by two previous presidents without penalty. Moreover, many legal experts agreed that it did not amount to a “crime of responsibility,” the only type of crime that justifies removing an elected president (Encarnación Reference Encarnación2017). In addition, most governors and many mayors engage in pedaladas, including a former governor who served as the rapporteur for the Senate’s special commission on impeachment. Further, more than 100 of the 513 deputies themselves were under formal investigation for some kind of criminal activity at the time of the impeachment vote, including Cunha (Chalhoub et al. Reference Chalhoub, Collins, Llanos, Pachón and Perry2017). Corruption probes were eventually ordered against more than one-third of the members of Temer’s cabinet (Democracy Now 2017). Rousseff, in contrast, stands out as one of the cleanest politicians in Brazil (Chalhoub et al. Reference Chalhoub, Collins, Llanos, Pachón and Perry2017). Together with the other evidence, this leads us to classify her impeachment as an instance of violence against women in politics, with psychological, sexual, and semiotic components.

Jo Cox

Jo Cox became a member of the British House of Commons in 2015, representing the Labour Party. On June 16, 2016, she was fatally shot and stabbed while arriving at a routine constituency surgery (a weekly walk-in session for constituents to meet with their MPs) in Birstall, West Yorkshire. The last sitting British MP to be killed was Conservative MP Ian Gow, who was assassinated by the Provisional Irish Republican Army in 1990; the last politician to die in an attack was county councilor Andrew Pennington in 2000. Cox’s murder occurred one week before the contested Brexit referendum, in which she was a vocal advocate for Britain to remain in the European Union. She also spoke positively about immigration and campaigned on behalf of refugees from Syria.

Witnesses reported that the assailant, Thomas Mair, yelled during the attack, “Britain first, keep Britain independent, Britain will always come first. This is for Britain” (Cobain, Parveen, and Taylor Reference Cobain, Parveen and Taylor2016). The UK Independence Party leader, Nigel Farage, among other politicians, had made immigration one of the central issues of the Brexit campaign. Adding to these tensions, in May 2016 the extremist Britain First political party pledged that it would target Muslims holding elected office in the United Kingdom, not stopping until all the “Islamist occupiers” were driven out of politics (York Reference York2016). This context indicates that Mair (1) made comments, statements, or gestures indicating bias. However, the bias in this case appears to be driven by race rather than gender. Mair’s “death to traitors” outburst during his first court appearance further shows that he viewed Cox as betraying her own race through her policy stances.

A search of Mair’s house and computer records following the attack uncovered (2) bias-related drawings and symbols. He had books on the Nazis, German military history, and white supremacy. He also kept newspaper clippings about Anders Breivik, who murdered 77 members of the Norwegian Labour Party in 2011. Mair’s internet searches included information on the British National Party, apartheid, the Ku Klux Klan, white supremacy, and Nazism (Cobain, Parveen, and Taylor Reference Cobain, Parveen and Taylor2016). These clues, again, point to racial prejudice, rather than gender bias, as a motivating factor. In his sentencing, however, the judge did make brief mention of a potential gender element when addressing Mair: “You even researched matricide, knowing that Jo Cox was the mother of young children” (Wilkie Reference Wilkie2016, 2).

Cox herself was (3) was clearly engaged in activities related to her identity group. On Twitter, she had shared a picture of herself and a group of Labour MPs holding up signs saying #Imafeminist. She disclosed to friends that she was concerned about the “increasing nature of hostility and aggression” toward female MPs (Hughes, Riley-Smith, and Swinford Reference Hughes, Riley-Smith and Swinford2016). She had personally contacted police after receiving a stream of malicious messages over the course of three months, which led to the arrest of a man who was given a warning in connection with his conduct in March 2016. Because of this online harassment, at the time of her death police were considering implementing additional security both at her constituency surgery in Birstall and at her houseboat in London. They found no links between this harasser and Mair, however. Based on the first three criteria of the bias event approach, it thus appears that Cox’s murder is best understood as a case of violence against politicians.

Considering the next two criteria shifts the picture somewhat. Mair was (4) a supporter of hate groups who attended gatherings of far-right political groups like the National Front and the English Defence League and purchased publications written by extremist groups in the United States and South Africa. Ideas about white supremacy and male supremacy are inextricably linked, according to prominent antihate organizations (ADL 2018). Within the white male supremacist worldview of “naturalized and hierarchized differences” (Ferber Reference Ferber1998), elements of misogyny are as integral as racist beliefs, with intense rage being generated by the prospect of a white woman challenging racism (Shaw Reference Shaw2016).

Following the attack, (5) a substantial portion of the community perceived that the incident was motivated by gender bias. Female MPs in particular viewed the murder through a gender lens. Diane Abbott stated, “It is hard to escape the conclusion that the vitriolic misogyny that so many women politicians endure framed the murderous attack on Jo” (Hughes, Riley-Smith, and Swinford Reference Hughes, Riley-Smith and Swinford2016). Cox’s friend, Jess Phillips, published numerous editorials in the ensuing months, writing at the time of Mair’s sentencing that “for me and for many of my colleagues—particularly female MPs—fear has also become real and present” (Phillips Reference Phillips2016). These perceptions were echoed by male politicians. Labour MP Chris Bryant, vocal in calling for these threats to be taken more seriously, remarked, “I think women MPs, gay MPs, ethnic minority MPs get the brunt of it” (Mason Reference Mason2016).

These perceptions are borne out by data: while women make up 32% of MPs, the Parliamentary Liaison and Investigation Team, established after Cox’s murder, estimates that approximately 60% of the cases it received concerned female MPs.Footnote 16 Viewing her murder in terms of challenges to women’s political presence, the Labour Party launched the Jo Cox Women in Leadership Programme. Drawing parallels with suffragettes who “had to contend with open hostility and abuse to win their right to vote,” Prime Minister Theresa May, a Conservative, opted to make her first public statement on a review of abuse and intimidation of candidates on February 6, 2018, the centenary of women’s suffrage (May Reference May2018).

Evidence that (6) the victim was evaluated negatively according a double standard is less clear. The police review of Mair’s internet search history revealed that he had looked at the Wikipedia page of William Hague (Cobain, Parveen, and Taylor Reference Cobain, Parveen and Taylor2016), a Conservative politician also from Yorkshire who had served as an MP, party leader, and leader of the opposition before being appointed to the House of Lords in 2015. Like Cox, Hague was a supporter of the Remain campaign. The work of the Fixated Threat Assessment Centre (FTAC), which assesses and manages risks from mentally ill individuals who harass, stalk, or threaten public figures, suggests that Mair most likely targeted Cox because she was his local MP. According to FTAC staff, every MP has a group of resentful constituents who channel their frustrations toward their local MP.17 It thus may have been a mere coincidence that Mair’s local MP was a young woman with pro-immigration views.

Given this mixed evidence, we find classification of this case to be the most challenging of the three. A bias event approach does not require that all six criteria be met, however: each simply provides potential clues as to the presence and significance of the bias that informs the commission of the event. Weighing each piece of information and how they fit together as a whole, we determine that the discussion in relation to criteria (4) gives new meaning to the evidence considered under criteria (1) and (2), indicating that the racist language and symbols also have an underlying misogynistic component. The reactions mapped under criteria (5) also lend greater substance to the evidence presented under criteria (3), and vice versa, by explaining why female politicians, particularly feminist ones, may experience a heightened sense of vulnerability to violence and harassment. On this basis, we argue that the murder of Jo Cox is a case of violence against women in politics, with physical and psychological elements.

Conclusions

Violence against women in politics is increasingly recognized around the world as a significant barrier to women’s political participation. This article seeks to strengthen its theoretical, empirical, and methodological foundations, recognizing that shared concepts and language are vital for building a cumulative research agenda. Conceptualizing this phenomenon in terms of structural, cultural, and symbolic violence, moreover, lays bare what is at stake by allowing violence against women in politics to continue. First, accepting abuse as “the cost of doing politics” raises questions about the robustness of democracy. Even without equality concerns, interfering with election campaigns or preventing officials from fulfilling their mandates violates the political rights of candidates as well as voters. Second, tolerating mistreatment due to individuals’ ascriptive characteristics infringes on their human rights, undermining their personal integrity and sense of social value. Third, normalizing women’s exclusion from political participation relegates them to second-class citizenship, threatening principles of gender equality.

Acknowledging the varied manifestations of violence against women in politics, in turn, points to the importance of developing multifaceted solutions. Adopting new legislation or revising existing laws is one approach that has been used extensively in Latin America to combat physical, psychological, and economic violence. Providing guidance for electoral observers in detecting and reporting violence against women during elections, especially physical, psychological, and sexual, has been piloted in Africa and Latin America. In North America and Western Europe, parliaments are developing stronger codes of conduct and procedures for reporting sexual harassment. To track and respond to the online abuse of politically active women, social media companies are partnering with civil society organizations to address psychological, sexual, and semiotic violence. The effectiveness of these strategies is not yet known, highlighting the need for further research and the continued development of countermeasures. A crucial first step for academics and practitioners, however, is to begin raising awareness that violence and harassment should not be the cost of women’s engagement in the political sphere.