Aims and Terminology (Nonbinary and Gender/Sex)

The binary female/male divide has been questioned by many scholars (Fausto-Sterling Reference Fausto-Sterling2000; Hird Reference Hird2000; Beemyn and Rankin Reference Beemyn and Rankin2011; Fausto-Sterling Reference Fausto-Sterling2000, Reference Fausto-Sterling2018); however, it also has recent defenders (Barnes Reference Barnes2019; Byrne Reference Byrne2020). My aim here is to argue against the binary model by referring to epistemic injustice (Fricker Reference Fricker2009; Reference Fricker, Kidd, Medina and Pohlhaus2017) and to sketch a nonbinary model of gender/sex traits.

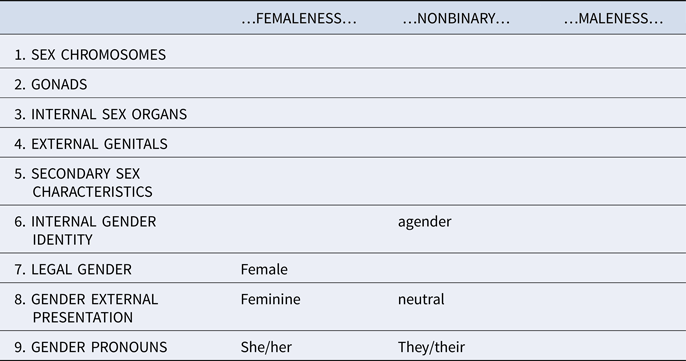

First, I present information about and by people with nonbinary gender identities (Valentine Reference Valentine2016; Bergman and Barker Reference Bergman, Barker, Richards, Bouman and Barker2017) and people with intersex traits (Davis Reference Davis2015; Viloria Reference Viloria2017a; Carpenter Reference Carpenter, Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2018). The groups are inadequately conceptualized and suffer from epistemic injustice. They also deliver counterexamples to the female/male divide. Second, I collect counterexamples on nine layers of gender/sex. The counterexamples create a multilayered, nonbinary model of gender/sex traits (Table 1). I apply the model to the description of some individuals. Third, I provide counterarguments to those of recent defenders of the binary. Finally, I focus on the concept of woman under the nonbinary model.

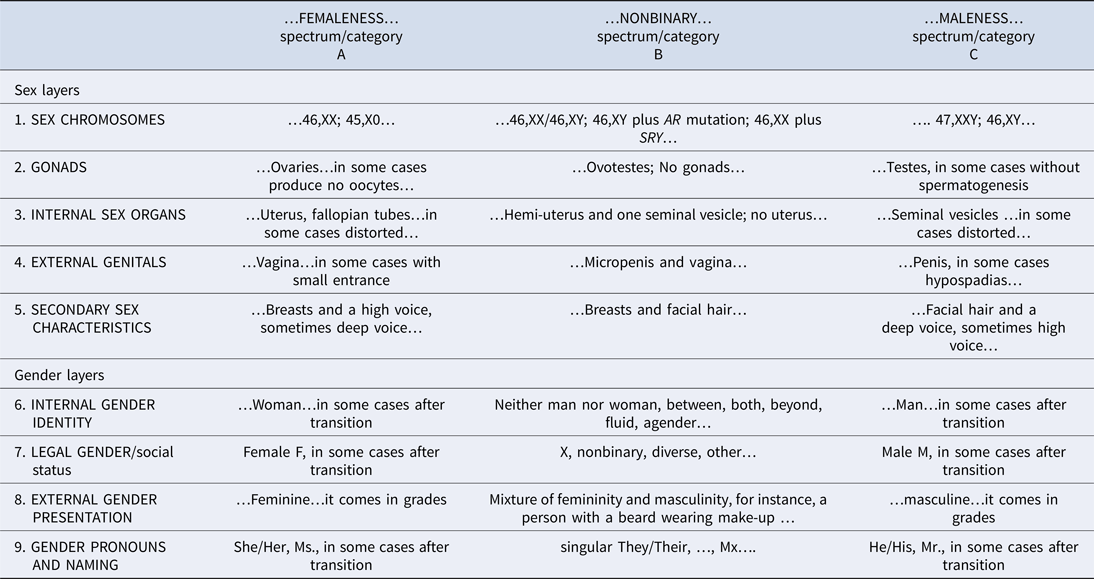

Table 1. Some examples of nonbinary traits

In this article, the nonbinary refers to “what is neither female nor male” or “the excluded by the binary female/male divide.” The term nonbinary gender is generally used as an identity category by some people who identify as neither a man nor a woman (Beemyn and Rankin Reference Beemyn and Rankin2011; Valentine Reference Valentine2016). However, bodily characteristics that are neither female nor male are usually referred to as intersex (Ghattas Reference Ghattas2015; Viloria Reference Viloria2017a).

In this article, the term nonbinary has two uses. First, I adopt general use and employ nonbinary in reference to gender identity (of gender, people, persons). Second, I create a technical meaning and apply nonbinary to any gender/sex trait that is neither female nor male. This technical version of nonbinary is further used to represent the category of such traits. To avoid accidentally blurring gender and sex, the sex traits from the category are referred to as intersex, and only the whole category, gender traits, and gender/sex clusters belonging to it are referred to as nonbinary.

I use the phrase gender/sex (similar to Van Anders Reference Van Anders2015) to talk about sex and gender as one cluster of traits. Of course, the divide between sex and gender is important in describing the situation of transgender and intersex people, for instance, to show that a person can have a body that is considered to be male but a female identity, or an intersex body but a female identity. However, for my purposes of arguing against the entire binary gender/sex system and to develop a nonbinary, multilayered model of gender/sex, in some contexts it is necessary to discuss sex and gender as one cluster. If being female is “a mixture of sex and gender” (Mikkola Reference Mikkola and Witt2011, 76), the model of gender/sex, binary or nonbinary, requires the analysis of sex and gender as one cluster.Footnote 1

In the term gender/sex, I put the term gender first to emphasize that one's declared gender identity deserves respect in any embodiment. Below, I begin my argument against the binary concept of gender/sex by presenting two groups of people.

People with Nonbinary Gender Identities

According to S. Bear Bergman and Meg-John Barker, a social movement of people with nonbinary gender identities has developed through “the trans, queer, and bisexual movements which have been challenging binaries of sex, gender, and sexuality for some decades now” (Bergman and Barker Reference Bergman, Barker, Richards, Bouman and Barker2017, 33). Transgender people who do not identify with the gender assigned to them at birth (Beemyn and Rankin Reference Beemyn and Rankin2011) created the environment in which identities beyond female/male emerged under many names (for example, nonbinary, genderqueer, genderfluid, agender, androgyne) and became a distinct identity (Hines Reference Hines2007; Bockting Reference Bockting2008; Beemyn and Rankin Reference Beemyn and Rankin2011; Rahilly Reference Rahilly2015; Valentine Reference Valentine2016). For instance, a study conducted in Poland estimated 29.7% nonbinary identities among transgender people (Świder and Winiewski Reference Świder, Winiewski and Ziemińska2017, 19). Nonbinary gender identities have also been discovered among people with intersex traits (Schweizer et al. Reference Schweizer, Brunner, Handford and Richter-Appelt2014) and in other contexts (Monro Reference Monro2015, 48).

In 2016, the Scottish Trans Alliance published the report “Non-Binary People's Experiences in the UK” using nonbinary as an umbrella term for all identities outside a female/male binary (Valentine Reference Valentine2016, 12). Earlier, Genny Beemyn and Susan Rankin used genderqueer as an umbrella term (Beemyn and Rankin Reference Beemyn and Rankin2011), and Christina Richards and colleagues used both terms for that function (Richards et al. Reference Richards, Bouman, Seal, Barker, Nieder and T'Sjoen2016). In my view, the meaning of nonbinary as a pure negation is easier to understand than genderqueer, and it is more universal than genderfluid or agender. I follow Vic Valentine's terminological decision. Additionally, by employing the terms nonbinary people or a nonbinary person, I intend to mean persons with nonbinary gender identities (expressed or felt).

In Valentine's report, nonbinary people are defined as people “identifying as either having a gender that is in-between or beyond the two categories ‘man’ and ‘woman,’ as fluctuating between ‘man’ and ‘woman,’ or as having no gender, either permanently or some of the time” (Valentine Reference Valentine2016, 6). It is important to note that a nonbinary identity can be fixed or fluid and that such fluidity is commonly found. Answering the question, “Would you describe your gender identity (or absence of gender identity) as constant and fixed; or, is it fluid and changing?” (13), most respondents (54%) described their identity as fluid, and 31% described their identity as fixed. This result explains why genderfluid is important but not a universal term for people outside of a female/male binary.

A person with a fluid, nonbinary gender identity says, “some days I feel more masculine, some days more feminine” (14), and a person with fixed nonbinary gender identity says, “How I choose to express that varies. Sometimes I wish to look more masculine or feminine” (15). In some cases, gender identity is fluid but external expression is fixed (“I normally stick with a more masculine expression” [13]).

Gender-neutral identity, that is, agender, is also either fixed or fluid. It is mysterious when individuals describe their identity as being completely genderless. “I feel it as an absence of gender, identifying with neither male nor female nor any of the other non-binary identities” (15). In our gendered culture, such identity is a paradox: gender-neutral identity is both a type of nonbinary gender identity, and it is not a gender identity at all. Agender identity belongs to nonbinary identity as the negation of the female/male divide; however, it goes further, and it is not a type of gender identity at all. “Gender as a model makes no sense of my experience at all—though I'm perfectly fine with it working for other people” (14). This binary approach to thinking about gender (Barnes Reference Barnes2019) will be addressed further below.

One respondent with a fixed agender identity says that their external gender presentation is inadequate to internal identity. “I have identified as agender/genderless for several years . . . those who I'm close to know I prefer neutral pronouns, but in day-to-day life I have to present as a woman and use she/her pronouns” (Valentine Reference Valentine2016, 14; see Table 5).

It is important to note that some nonbinary people do not identify as transgender (15%) because, as they say, they have no experience of having hormones and surgery, dysphoria and transition. “I still partly identify with the gender I was assigned . . . [I] feel like I'm not ‘trans enough’ to be trans” (17). They partly fit the definition (the experienced gender does not conform to the gender assigned at birth); however, they represent a distinct group of people, a specific community, by identifying outside of the female/male divide. The idea being beyond-the-binary is against the interests of the binary majority of transgender people because it can present them as “problematically positioned with regard to the binary” (Bettcher Reference Bettcher and Zalta2014, 16). Thus, the groups overlap (most trans people are binary, and some nonbinary people are not trans).

The Valentine report and other studies (Beemyn and Rankin Reference Beemyn and Rankin2011; Richards et al. Reference Richards, Bouman, Seal, Barker, Nieder and T'Sjoen2016; Richards, Bouman, and Barker Reference Richards, Bouman, Barker, Richards, Bouman and Barker2017) show that in the experience of nonbinary identities, gender is sometimes partial and fluid. Having a male legal gender does not contradict that a person also feels like a woman and, in some safe contexts, expresses this female identity through the use of make-up, clothing, and female pronouns. The two opposite genders can also coexist as a simultaneous combination: one identity is socially expressed, and the second identity is internally felt.

The Valentine report indicates that most people with a nonbinary identity (64%) want to be able to legally record their gender as something other than female/male. The reason for this desire is to have their identity and experience recognized and legitimized. Currently, such individuals feel that their existence is deniedFootnote 2 (the remaining people are concerned about their safety, health services, and traveling to other countries) (Valentine Reference Valentine2016, 69, 73). The next problem is the means of recording a nonbinary identity. Most of the respondents (72.5%), for the multiple-choice question, chose a third gender category (nonbinary, other) as the best option; however, a large group (41%) accepted that their gender is not recorded on their identity documents (73). The nonbinary respondents remarked that they are in a similar situation to that of intersex people: “intersex people have to pick a ‘sex’ where they do not fit one” (80).

People with Intersex Traits

People with intersex traits are described on the biological level and have all possible gender identities as in the general population. They are “born with a combination of characteristics (for example, genital, gonadal, and/or chromosomal) that are typically presumed to be exclusively male or female” (Davis Reference Davis2015, 2). Such characteristics can include a vagina with testes or, in other cases, genitals that can be described as both a micropenis and an enlarged clitoris. Thus, their bodies do not fall into the female/male binary divide. In medical terms, such people are designated by the pathologizing acronym DSD (disorders of sex development). The acronym is an umbrella term for known conditions such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Nordenström, Houk, Faisal Ahmed, Auchus, Baratz, Dalke, Liao, Lin-Su, Looijenga, Mazur, Meyer-Bahlburg, Mouriquand, Quigley, Sandberg, Vilain and Witchel2016).

Social researchers use the term intersex and have interviewed many people with intersex traits (Schweizer et al. Reference Schweizer, Brunner, Handford and Richter-Appelt2014; Van Lisdonk Reference Van Lisdonk2014; Davis Reference Davis2015). Additionally, historians have described intersex people of the past (Reis Reference Reis2009; Mak Reference Mak2012). There are mentions of “congenital eunuchs” in the Bible (Matthew 19.12), and there is the Greek myth of Hermaphroditus (Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.285). Many people are familiar with problems of intersex female athletes in sports competitions (Amy-Chinn Reference Amy-Chinn2012).

Despite the evidence, “a binary model of sex as unequivocally male or female has remained an almost universal axiom” (Karkazis Reference Karkazis2008, 31). For example, Alex Byrne writes, “someone who is, simply, neither female nor male. Are there any such individuals?” (Byrne Reference Byrne2020, 11). Indeed, the evidence on people with intersex traits is, to a large extent, erased from public discussion, hidden behind hospital doors, or treated as family secrets.

The result of the erasure is the harm caused by “normalizing” surgery on newborns conducted to adapt intersex bodies to the binary norms. A substantial body of literature shows how harmful “normalizing” surgery is for intersex children (Karkazis Reference Karkazis2008; Feder Reference Feder2014; Monro et al. Reference Monro, Crocetti, Yeadon-Lee, Garland and Travis2017). “Normalizing” refers to surgery that is intended to make the genitals/body appear typically male or female. Most intersex children who undergo surgical modification are “emotionally and physically scarred” (Davis Reference Davis2015, 90). After “normalizing” surgery, intersex children are often subjected to a lifetime of recurring surgeries, chronic pain, or hormone supplementation. Clitoral reduction can eliminate sexual pleasure, and scarred genitals are a source of problems in intimate relationships. There is also the risk of an incorrect sex assignment with an irreversible loss of genitals and fertility. Nevertheless, these surgeries continue to occur (Creighton et al. Reference Creighton, Lina Michala and Yaron2014, 38; Monro et al. Reference Monro, Crocetti, Yeadon-Lee, Garland and Travis2017, 11).

Katinka Schweizer and colleagues conducted a study involving intersex people to explore the spectrum of gender identities. “Twenty-four percent reported an inclusive ‘mixed’ two-gender identity, including both male and female elements, and 3% reported a neither female nor male gender identity” (Schweizer et al. Reference Schweizer, Brunner, Handford and Richter-Appelt2014, 56). Thus, people with intersex traits can have all possible gender identities; most of them are intersex women and intersex men, and the minority have a nonbinary identity. Additionally, as I noted in the section above, people with a nonbinary gender identity can have all possible embodiments (intersexed or not, assigned female at birth or assigned male at birth, after medical transition or without any). That is why people with intersex traits and people with nonbinary gender identities constitute two distinct groups (with specific problems and interests) that only partly overlap. The two groups can be illustrated by two crossing circles.

There is a common part of the two groups, and the example of such a person is American intersex activist Hida Viloria who came out as intersex and as nonbinary: “I actually do feel like something other than male or female, or both male and female—a third gender, if you will—and my body looks like it, too” (Viloria Reference Viloria2017a, 195). Viloria is an intersex activist who describes the nonbinary category thus: “the emergence of people with non-binary gender identities is an important step for the acceptance of all intersex people. After all, the big fear driving ‘corrective’ treatments is that intersex babies won't grow up to be men or women. So, if we have a whole community of people voluntarily saying that they are not men or women and living voluntarily as neither . . . it creates a viable community that parents can see” (274). Viloria claims that gaining civil rights for nonbinary identities can help the parents of intersex children to postpone “normalizing” surgery and limit the number of such interventions.

Additionally, such people who are intersex and identify as nonbinary played an important role in the legislation process to introduce the nonbinary option in identity documents (such as Alex MacFarlane in Australia (Fenton-Glynn Reference Fenton-Glynn, Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2018), Vanja in Germany (Helms Reference Helms, Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2018), and Sara Kelly Keenan in California (Greenberg Reference Greenberg, Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2018)). Their neither female nor male sex characteristics were important reasons for legislators to introduce the third gender category on identity documents.

However, according to Australian intersex activist Morgan Carpenter, “the existence of intersex people is instrumentalized for the benefit of other, overlapping populations” (Carpenter Reference Carpenter, Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2018, 507). Carpenter also finds no link between the nonbinary category and “normalizing” surgeries and writes that nonbinary passports in Australia had no impact on the end of “normalizing” surgeries on intersex infants (484). According to him, as the binary model forces intersex bodies to be either female or male, the third category presents intersex people as neither female nor male when most of them have a female or male identity (507). Additionally, he refers to this situation as the “othering” of the intersex community (513). However, finally, Carpenter concedes that “access to binary and neutrally-termed ‘non-binary’ sex/gender markers should be available for any person (intersex or not) preferring such options on the basis of self-determination” (514).

The Australian intersex community is against any third-sex classifications at birth registration as an intersex child may grow up to identify with a binary gender. However, they believe that people who are able to consent should be able to choose a nonbinary gender marker (Darlington Reference Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2017, 13). Similarly, Organization Intersex International in Europe accepts only a particular version of the third-gender option in documents: “options other than ‘male’ and ‘female’ should be available for all individuals regardless whether they are intersex or not” (Ghattas Reference Ghattas2015, 22). Such a version, which is based on self-determination, does not link the whole intersex community with having a nonbinary identity. However, in Germany, only intersex people are eligible for the nonbinary category diverse, and such a version of legislation risks blurring being intersex and being nonbinary (Althoff Reference Althoff, Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2018), especially for women and men with some intersex traits.

Indeed, the existence of a nonbinary category in public space risks the inclusion of some intersex people in a third category against their will. A similar problem was described by Talia Bettcher for transgender women and men (Bettcher Reference Bettcher and Zalta2014). However, in my opinion, this risk should not silence a minority who fight for a third category. This conflict of interest makes the people with a nonbinary identity a distinct group other than the majority of the transgender community and the majority of the intersex community.

The intersex community is divided into those who are interested in a nonbinary gender category and the majority who are not interested in it. The second group with a binary gender identity is interested in accepting the continuum of biological categories female/male for assurance that they have a right to belong to the categories and that their gender identity is respected in every embodiment. For the nonbinary group, the bodily continuum is not enough; they need a continuum on the level of identity. In Table 1, I try to capture the continuum of traits on both levels, and I assume the priority of gender identity over other traits.

Even if there is a tension within the intersex community with regard to how to step outside the binary, there is agreement that the source of “normalizing” surgeries is the binary model, and that the model is “upheld by structural violence” (Darlington 2018, 13). Those in the community report the experience that “sex is a spectrum and that people with variations of sex characteristics other than male or female do exist” (Ghattas Reference Ghattas2015, 9). Thus, both people with nonbinary gender identities and people with intersex traits suffer because of the oversimplification of the binary model of gender/sex. Their harm can be identified as epistemic injustice (Carpenter Reference Carpenter, Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2018, 467).

Epistemic Injustice of the Male/Female Divide

Miranda Fricker coined the term epistemic injustice to describe the phenomenon of epistemic dysfunction that becomes ethical dysfunction (Fricker Reference Fricker2009; Reference Fricker, Kidd, Medina and Pohlhaus2017). She described two forms: testimonial injustice and hermeneutical injustice. “Testimonial injustice occurs when prejudice causes a hearer to give a deflated level of credibility to a speaker's word” (Fricker Reference Fricker2009, 1). For instance, the old prejudice that women are irrational causes epistemic dysfunction (the hearer misses information) resulting in moral harm (a woman is degraded as a knower, and she can lose confidence in her beliefs). Hermeneutical injustice does not stem from a deficit of credibility; instead, such injustice stems from a gap in collective interpretive resources (the lack of a proper interpretation or the lack of a name for some experience). Hermeneutical injustice is not inflicted by any agent but by collective imagination (168). The users of public language transmit the hermeneutical gap and materialize the harm, and only the most sensitive people can stop the harm. According to Fricker, epistemic injustice is a form of unintentional discrimination that is easy to miss (Fricker Reference Fricker, Kidd, Medina and Pohlhaus2017, 53–54).

An important area where hermeneutical injustice can be identified is the social status of people with intersex traits. As mentioned above, there is enough medical and social evidence against the binary female/male divide; however, public language uses it. Consequently, knowledge about neither female nor male traits is erased from the public imagination. Medical experts use strategies to interpret such traits as rare and needing fixing. Parents are willing to exert all efforts to rescue their children from a status of being neither female nor male and request surgery. Such parents even ignore the risk of chronic pain because the surgery is their highest priority, and they seek erasure of their child's intersex traits at all costs. Children with intersex traits feel “the knife of the norm” on their bodies (Butler Reference Butler2004, 53).Footnote 3

People with nonbinary identities suffer from a credibility deficit, and there is no name for their sense of self in the collective social imagination; thus, their behavior is interpreted as a disorder. The result is exclusion from the legal system and stigmatization. The body or identity outside the conceptual system is invisible, erased, or interpreted as disordered. This status can easily cause social and physical harm; and, in such cases, the epistemic vice of the social imagination turns into the moral vice of a society.

There is no clear culprit here, and this situation is a structural dysfunction in which people sustain and transmit the hermeneutical gap and materialize the harm in nondeliberate ways. People with intersex traits or nonbinary identities are not properly understood and cannot understand their own experience because there is no hermeneutical resource. According to Fricker, the only way to stop the injustice is to properly pay attention to the evidence (Fricker Reference Fricker2009, 90) and to generate “new meanings to fill in the offending hermeneutical gaps” (174). My article follows this advice. I aim to present a list of counterexamples to the binary of male/female.

The Table of Counterexamples as a Nonbinary Model

In Table 1, the notions of sex and gender are separated into nine layers of traits to show that sex traits and gender traits can occur in different clusters and forms. I consider nine basic gender/sex layers (chromosomes, gonads, internal sex organs, external genitalia, secondary sex characteristics, internal gender identity, legal gender, gender external presentation, gender pronouns and naming). The list can be extended.

I presuppose that at every layer, there is a continuum of forms of traits that can cluster with traits from other layers in an “inconsistent” way. The continuum is not only between femaleness and maleness but also outside or beyond these categories (“no gonads,” “no gender identity”). To break the binary, I identify a third spectrum/category for traits that are neither female nor male. The dots between the spectra are signs of continuity. The columns are not prototypes of pure, consistent clusters because the continuum at the layers and the inconsistency between the layers refer to all people. The boundaries here are discursive cuts in Karen Barad's sense (Barad Reference Barad2003). I presuppose her processual ontology where concepts are boundary-making material practices. The categories are spectra with ragged, overlapping, and fluid boundaries, “categorical divides over continuous variability” (Ayala and Vasilyeva Reference Ayala and Vasilyeva2015, 729).

Table 1 presents counterexamples to the binary model of gender/sex, which are situated in the column nonbinary on each of the nine layers. In other columns are examples of spectra of femaleness and maleness. I emphasize that Table 1 provides only examples (and not an exhaustive list) and that the examples in the column are not causally connected in a deterministic way to one another as every layer is partially independent, and layers can be inconsistent (one female and another male or neither). As shown in medical reports (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Nordenström, Houk, Faisal Ahmed, Auchus, Baratz, Dalke, Liao, Lin-Su, Looijenga, Mazur, Meyer-Bahlburg, Mouriquand, Quigley, Sandberg, Vilain and Witchel2016), each sex layer is the result of a dynamic developmental process that produces various forms (continuum of forms). Similarly, as is shown in social studies (Richards et al. Reference Richards, Bouman, Seal, Barker, Nieder and T'Sjoen2016), there is a continuum of gender identities. The examples for every spectrum are described below in commentaries to Table 1.

I begin by showing that femaleness and maleness are spectra. At the chromosome layer (1A), femaleness manifests with 46,XX; however, the spectrum of femaleness includes 47,XXX or the karyotype 45,X0 in Turner syndrome (Bancroft Reference Bancroft2009). At the gonadal layer, femaleness manifests with ovaries; however, in some cases, they do not produce oocytes (2A). At the internal sex-organ layer, femaleness manifests with a uterus and fallopian tubes, and an example of the spectrum can be the inability to menstruate (Van Lisdonk Reference Van Lisdonk2014, 23) (3A). At the genital layer, femaleness manifests with a vagina; however, sometimes, in the case of Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome, the vagina has a small entrance (Harper Reference Harper2007, 23) (4A). At the layer of the secondary sex characteristics, femaleness can manifest with breasts and a high voice; however, sometimes, a woman has a deep voice (5A). At the gender identity layer, femininity is the internal feeling of being a woman that sometimes occurs after gender dysphoria during childhood (6A). At the legal-gender layer, femaleness is assigned at birth or as the result of a legal transition process (7A). There are patterns of feminine external presentation (8A) and pronouns used by women such as she/her (9A).

A similar list of examples can be created for the spectrum of maleness (column C). At the chromosomes layer (1C), maleness has 46,XY chromosomes but also 47,XXY chromosomes, which is known as Klinefelter syndrome (Bancroft Reference Bancroft2009). At the gonadal layer (2C), maleness manifests with testes (sometimes without spermatogenesis). Seminal vesicles belong to layer 3C, and, in some cases, they can be distorted. At the genital layer (4C), maleness manifests with a penis and scrotum; however, in some cases, there is hypospadias (the opening of the urethra is not at the tip of the penis but along it or in the scrotum, which makes it difficult to urinate standing [Van Lisdonk Reference Van Lisdonk2014, 22]). A deep voice and facial hair are male secondary sex characteristics; however, these characteristics can manifest in grades, and there are men with high voices and sparse facial hair (5C). At the gender identity layer (6C), in addition to permanent male identity, the male identity can be adopted after gender dysphoria in childhood (Rahilly Reference Rahilly2015). At the legal-gender layer, a person may legally become a man at birth or as a result of a transition process after some years of legally being a woman (7C). In (8C) and (9C), there are patterns of masculine fashion, naming, and the use of pronouns (he, his, and him).

The nonbinary category (B) in Table 1 embraces gender/sex traits that belong to an overlapping area or extend beyond the male and female spectra. At the chromosome layer (1B), an example is mosaicism 46,XX/46,XY (Souter et al. Reference Souter, Parisi, Nyholt, Kapur, Henders, Opheim, Gunther, Mitchell, Glass and Montgomery2007); 46,XX chromosomes with an additional chain of SRY (sex-determining-region Y) with the gene SRY translocated to the X chromosome, leading to the development of testes and other male sex traits in a 46,XX person; or the chromosomes 46,XY plus an AR gene mutation, resulting in androgen insensitivity syndrome (Bancroft Reference Bancroft2009). At the layer of the gonads, an example is one ovotestis or two ovotestes, each of which contains both ovarian and testicular tissue (2B). At the internal sex organ layer (3B), an example is one-half of a uterus and one vas deferens. At the genital layer (4B), the nonbinary traits are a micropenis and a vagina in one body (Souter et al. Reference Souter, Parisi, Nyholt, Kapur, Henders, Opheim, Gunther, Mitchell, Glass and Montgomery2007; Table 3). At the layer of the secondary sex characteristics (5B), the nonbinary cluster is a composition of developed breasts and facial hair (Greenberg Reference Greenberg2012, 94). At the gender identity layer (6B), the nonbinary characteristics include the feeling of being neither a woman nor a man (Bergman and Barker Reference Bergman, Barker, Richards, Bouman and Barker2017). A person with a nonbinary gender identity can request the third-gender option on documents (7B). The community of nonbinary persons creates its own fashion style as neither feminine nor masculine (8B) and creates a language with special pronouns such as the singular use of they/their (9B).

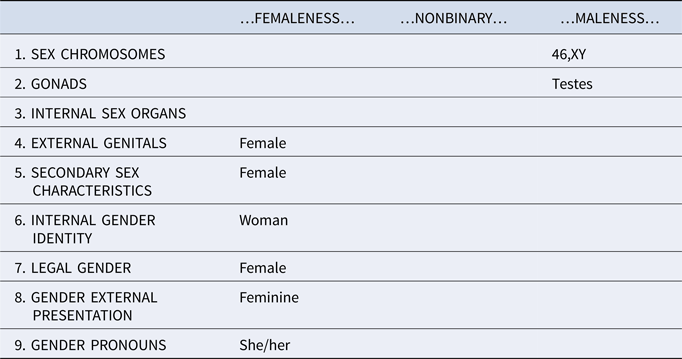

Having neither female nor male sex characteristics also creates a clash among the sex layers. I use tables below to clearly show how the sex and gender traits are inconsistent between the layers. The examples are taken from the existing literature. Table 2 includes an example of an XY woman with testes, no uterus, and no ovaries but with female genitals, a female gender identity, and female secondary sex characteristics. This description is of the Spanish athlete Maria Patiño, who was disqualified from sports based on a chromosomal test. Her medical records were published in Patiño Reference Patiño2005. The boxes representing the nonbinary traits within particular layers are empty here; however, the cluster of sex characteristics is neither female nor male due to their cross-layer inconsistency.

Table 2. An example of a woman with intersex traits

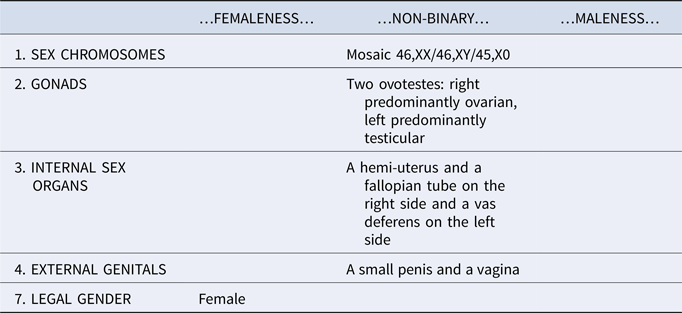

The tables below aim to apply the model to other individuals. Table 3 presents an example of a baby with many traits that belong to the nonbinary category that are neither female nor male: mosaic sex chromosomes 46,XX/46,XY/45,X0, two ovotestes, the right of which was predominantly ovarian and the left of which was predominantly testicular, a hemi-uterus and a fallopian tube on the right side and a vas deferens on the left side, and both a micropenis and a vagina. The baby was designated female (Souter et al. Reference Souter, Parisi, Nyholt, Kapur, Henders, Opheim, Gunther, Mitchell, Glass and Montgomery2007).

Table 3. An example of a baby with intersex traits

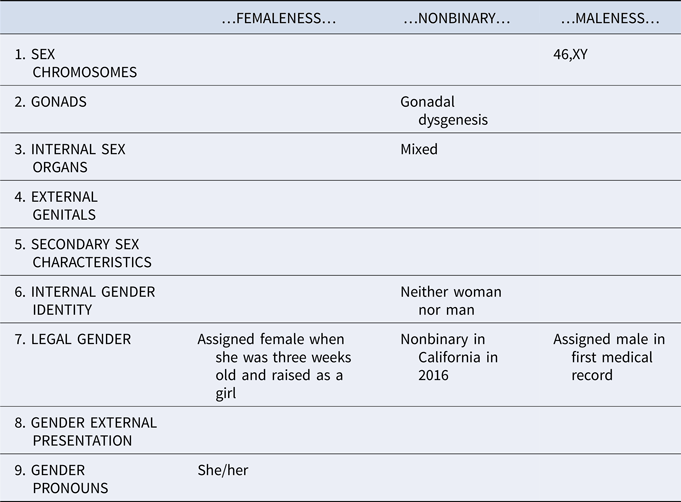

Table 4 provides an example of a person with intersex characteristics and a nonbinary identity, activist Sara Kelly Keenan, who presented her medical data in an interview (see Viloria Reference Viloria2017b). She describes herself as having 46,XY chromosomes, born with Swyer's syndrome (gonads are neither testes nor ovaries [Conway Reference Conway2014, 30]) and mixed reproductive organs. Her gender identity is neither male nor female. She has been recognized as nonbinary by the state of California, and New York City issued her a new birth certificate with the sex assignment intersex. She uses she/her pronouns.

Table 4. An example of a person with intersex traits and nonbinary identity

Table 5 presents a person with a nonbinary gender identity (from Valentine Reference Valentine2016, 14). In everyday life, they present as a woman; however, they feel agender and in safe contexts use neutral pronouns.

Table 5. An example of a person with nonbinary identity

Source: Tables 1–5 are my own elaboration. My earlier version (here modified) of Tables 1–4 was published in Polish (Ziemińska Reference Ziemińska2018).

The model presented in Table 1 is about traits, not about people. However, it is applicable to people, as I have shown in Tables 2–5. Gender/sex traits are important for gender identification. In the recent philosophical literature, there are two main theories of gender identification: social-position theory (Witt Reference Witt2011; Haslanger Reference Haslanger and Haslanger2012; Barnes Reference Barnes2019) and identity-based theory (Bettcher Reference Bettcher and Zalta2014; Jenkins Reference Jenkins2016). The first considers gender in terms of a class, and the second considers gender in terms of identity (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2016). The first is externalist: “[an] individual's gender is determined by social factors external to that individual—how they are perceived, what roles they are expected to occupy” (Barnes Reference Barnes2019, 3). According to this view, to be a woman is to be classed as a woman based on perceived bodily features. Such a theory has exclusion problems concerning some trans people; it cannot explain the misgendering phenomenon, and it undervalues internal gender identity. The second approach is internalist; gender is a matter of self-identification. The weakness of the second approach is the difficulty of defining the internally felt sense of gender identity (it is dependent on social norms and is embodied [Jenkins Reference Jenkins2018]); some people (with aphasia or Alzheimer's) cannot self-determine their gender (Barnes Reference Barnes2019).

On the one hand, expressed gender identity has priority over how a person is classed externally; it is an assumption based on knowledge of the experience of transgender people (Beemyn and Rankin Reference Beemyn and Rankin2011) and about the importance of gender identity in social life for all persons (Witt Reference Witt2011). On the other hand, in the case of newborns and in the case of other persons whose gender identity is not known, the embodiment (or assumptions about sex characteristics) is the basis of gender assignment (see my definition in the last section of being a woman [W]). To assign gender/sex at birth, external genitals (layer 4 in Table 1) are treated as signifiers and are inspected from third-person perspective. When deeper medical diagnosis is conducted, chromosomes, gonads, and internal sex organs are also examined (layers 1–4). When a person on the street attempts to identify the gender of an approaching stranger, the external gender presentation (layer 8) and secondary sex characteristics (layer 5) are usually considered. However, one's legal gender (layer 7) that was assigned at birth can be corrected based on first-person gender identification (layer 6).

My technical nonbinary category is based on traits and not people. Only gender identity is such a special trait for which the term nonbinary person can be used to express having a nonbinary gender identity; for example, the term woman can be used to express having a female gender identity, and the term man can be used to express having a male gender identity (see Jenkins Reference Jenkins2016, 421).

Of course, the nonbinary model is easy to defend when we prefer the identity-based theory (there are nonbinary gender identities). However, there are important objections from the externalist theories. According to Barnes, the social structure of gender is binary, and, according to Byrne, biological sexes are binary (Barnes Reference Barnes2019; Byrne Reference Byrne2020).

Recent Defenders of the Binary Model of Gender/Sex

Elizabeth Barnes writes, “our social world is structured in a way that codes bodies as male or female . . . the social structure of masculinization and feminization is the ultimate metaphysical explanation of gender” (Barnes Reference Barnes2019, 12) The structure is binary: being perceived as male (being masculinized) or female (being feminized). “The underlying structure of gender is binary” (14).

Barnes assumes that gender identity is an internal response to this basic social division and concedes that people have first-person authority about their own gender identity. She acknowledges that gender identity can be nonbinary and that biological traits can be intersex: “[the] research increasingly shows a spectrum of sex variation between the male and female binaries” (16). According to her, there are also additional genders as social positions: the gender outlier (when perceived biological traits are inconsistent with perceived attempts to occupy a gender role) and the gender confounder (when perceived biological traits are both/neither male and/or female and people cannot figure out any gender role). However, according to her, nonbinary gender identities and additional genders as social positions are explained by the basic binary structure that is oppressive but real.

Barnes thinks that the structure is based on assumptions about reproductive roles. “We assume that there are two ways that bodies can be (based on assumptions about reproductive role), and then mandate that there are ways you ought to behave, things you ought to identify with, ways you ought to express yourself based on being sorted into one of those two categories” (14).

Reproductive roles can be the deepest source of gender perception. Other scholars remark that a woman is a person who is perceived as being able to conceive, gestate, give birth, and breastfeed and that a man is perceived as being able to fertilize (Stone Reference Stone2007, 44). Gender is defined in terms of socially mediated (expected) reproductive functions (Witt Reference Witt2011, 31). Indeed, female traits are traits connected with female reproductive roles.

However, some people do not participate in reproduction at all, and social roles in reproduction are changing with in vitro fertilization (IVF) technology. Reproduction was binary in the pretechnological area, and now the reproductive roles can be fragmented and divided among many people. With the support of the technology, three biological parents are possible (an egg donor, a sperm donor, a gestational surrogate mother) and two genetic mothers (an egg nucleus can be fused with healthy cytoplasm containing mitochondria with genetic material from another egg [Appleby, Scott, and Wilkinson Reference Appleby, Scott and Wilkinson2017, 3]). A trans man with a uterus can play the role of gestational mother (Light et al. Reference Light, Obedin-Maliver, Sevelius and Kerns2014; Hafford-Letchfield et al. Reference Hafford-Letchfield, Christine Cocker, Moreblessing Tinarwo and Manning2019). A woman with a vagina and testes can be a sperm donor, a person with ovotestes (gonads with ovarian and testicular tissue) can be both a sperm donor and an egg donor due to the in vitro maturation of gametes (Creighton et al. Reference Creighton, Lina Michala and Yaron2014, 37), and some women with 46,XY have had successful pregnancies (Conway Reference Conway2014, 30). Thus the idea of reproductive roles can be inconsistent with perceived gender and perceived sex characteristics. IVF technology fragmented the reproductive roles into more than two (egg donor, sperm donor, gestational surrogate mother, two genetic mothers, trans man as gestational mother, a woman as sperm donor, one person as egg and sperm donor).

The binary structure of gender in terms of reproductive roles was constructed in the past, before IVF was developed. I agree with Barnes that it exists as a social reality. However, the structure is not a mystery; it is derived from the social imagination, customs, and cultural patterns. Such sources change more slowly than medical technology and psychology; however, recently, the binary structure of gender has been challenged by new legislation and pronouns. In Australia, Germany, and in some states in the US, the law recognizes that a citizen may be neither female nor male (Althoff Reference Althoff, Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2018; Fenton-Glynn Reference Fenton-Glynn, Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2018; Greenberg Reference Greenberg, Scherpe, Dutta and Helms2018). People with a nonbinary identity are in the process of creating their own pronouns that are neither female nor male. The use of the singular they/their is popular and accepted in formal writing by the Chicago Manual of Style. Thus, I disagree with Barnes that “there is a social reality of gender that is independent our how we talk about and think about gender” (Barnes Reference Barnes2019, 20). Some social and cultural phenomena are evidence that the binary model of gender is going away. In the past, it was unimaginable that the earth could revolve around the sun or that women could have the right to vote; however, such changes in our thinking have occurred.

Alex Byrne presupposes the binary model when he defends the view that being a woman is a biological category that is equivalent to being an adult human female (AHF) and that the same holds true for being a man. He defends the following theses:

(AHF) S is a woman iff S is an adult human female

(AHM) S is a man iff S is an adult human male

Let me focus on the category of woman. Byrne defends the thesis that if a person is a woman, she is also an adult human female, and if an individual is an adult human female, they are a woman. My first worry is the lack of definition of being a human female. Byrne treats it as an obvious biological category and avoids “entering the empirical weeds” (Byrne Reference Byrne2020, 11). However, there is an idea that the prototype of the (human) female is linked to “reproductive organs” (12). The question is what type of reproductive organs are enough to constitute a human female. As we know from the section above, female traits occur in various clusters—sometimes mixed with male traits. What about a person with testicles and vagina? (Table 2). Is having ovotestes a male or female characteristic? Is having a hemi-uterus, one seminal vesicle and two ovotestes a female characteristic? (Table 3). Sometimes, “there is no determinate answer to the question of whether one is female or male” (Stone Reference Stone2007, 44). That is why the class of human females in AHF is not well determined, and the problem is how this class can help us to determine the class of woman.

Byrne claims that even if there are some intersex persons, all human females are nevertheless women (right-to-left AHF). He concedes that the real problem would be if there are some adult human females who are not women. Of course, such counterexamples are trans men, persons with biological female traits (sometime with a uterus and ovaries) and a male identity. This is where my second worry arises. Byrne undervalues the felt identity of transgender people. To defend his theory, he gives as examples that some trans people are not sure about their gender identity or change the meaning of woman and man. For him, the testimony of trans women is not impressive. After that, he claims that trans women are not females (NF) and says, “NF is no doubt true” (17). I can guess that he means that trans women have no female reproductive organs.

For the sake of argument, let us assume that being a human female means having female reproductive organs, at least a uterus and ovaries. When Byrne claims that being a woman equals being an adult human female/having a uterus and ovaries (left-to-right AHF), counterexamples are some intersex women with mixed reproductive organs and trans women without female reproductive organs. When he claims that being an adult human female equals being a woman (right-to-left AHF), counterexamples are trans men, nonbinary people, and some intersex men (CAH) with a uterus and ovaries. Thus a serious problem of extension exists.

For the reasons listed above, I cannot agree that “women are adult human females—nothing more, and nothing less” (19). I claim that even for Byrne's idea of “bio women,” as on the level of biological sex characteristics, there is no clear boundary between female and male traits (examples in Table 1–4). The whole material world is processual; it is difficult to identify any dichotomy, even between human/nonhuman; why must the notion of gender/sex be binary? Byrne's argument is an attempt to make our categories simple when they are not, and this oversimplification results in epistemic injustice. Neither social structure nor biological description is the basis for an exclusive binary female/male divide. As the nonbinary continuum is on biological, psychological, and social levels, the binary model is inadequate, and it is a source of epistemic injustice. However, under the nonbinary model, the basic gender concepts do not disappear. To show this, I focus on the concept of woman.

The Concept of Woman and Femaleness under this Nonbinary Model

Feminism is based on a binary divide between women and men; however, Myra Hird warns that if feminist theory operates on a binary model, it is unjust to intersex women and transgender women (Hird Reference Hird2000). Feminist scholars have made famous mistakes about trans women (see Stryker and Bettcher Reference Stryker and Bettcher2016). The problems with the concept of woman and other gender categories are the problems of extension and unity.

Under this nonbinary model, there is no extension problem because the model is inclusive of women existing at the borderlines. Female gender identity—the sufficient but not necessary condition for being a woman—can be connected with many versions of embodiment. Often, such embodiment includes a set of female traits; however, sometimes, the traits are inconsistently female—some traits can be male (a woman with 46,XY chromosomes and testes) or neither female nor male (a woman with ovotestes). An intersex woman is a person with a female gender identity but some sex characteristics that are nonfemale, for instance, testes or ovotestes. A transgender woman is a person with a female gender identity but with some sex characteristics that can be male or medically changed. Conversely, a female body or a body with some female traits can be the embodiment of a male or nonbinary gender identity.

Alison Stone described it on a biological level. According to her cluster theory of the sexes, no single property is both necessary and sufficient for the female sex; however, the idea of a cluster is helpful as sex characteristics form a cluster. “To be female is to have enough of a cluster of properties (ovaries, breasts, vagina, etc.), which cluster because they encourage one another's presence” (Stone Reference Stone2007, 45). Even if having a uterus seems to be the distinctive female trait, there are women without a uterus and men with a uterus, or a person can have a hemi-uterus. The same is the case with ovaries and ovotestes. Therefore, being female is a matter of the degree to which one has a sufficient number of female traits that often co-occur but do not always occur together.

There are at least two sources for a female spectrum. First, the number of female traits in a cluster and, second, the grade of femaleness of a particular trait. A cluster of gender/sex traits belongs to a female spectrum if it has enough female traits. A particular gender/sex trait belongs to a female spectrum if its form is sufficiently similar to the culture patterns of the female trait.

There is also reason to perceive the spectrum on an identity level. Gender identity is sometimes fluid and complex; the same is true for external gender presentation. Additionally, nonbinary persons with diverse identities can be closer to or further from a female identity. For instance, Bettcher gives example of a thin line between a butch female identity (masculine-presenting, female-assigned-at-birth individual) and a trans man identity (female-to-male individual without legal and medical transition) (Bettcher Reference Bettcher and Zalta2014). Additionally, as we know from Valentine, place and time are important factors as they bring changes not only in body but also in gender identity or gender expression (Valentine Reference Valentine2016). Female gender expression or female pronouns can be used in a particular time and place (context) only. Thus there is a type of female identity that is limited to a particular space/context, and a partly female identity that can exist simultaneously with a partly male or partly agender identity. This type of temporary, contextual, and partial femaleness is a viable form of female identity. Nonbinary persons reveal such an identity.

The model brings about the fragmentation of the category “woman”; however, fragmentation can be progressive (Hemmings Reference Hemmings2011, 4), as it was progress when intersectionality as a hermeneutic tool was implemented and an elusive unity of women was shown. This model extends such fragmentation to embodiment and identity, and its positive result is to include intersex women, transgender women, and temporary female identities. The theoretically fragmented members of the class woman are unified as clusters and/or identities; a good metaphor for it is the idea of family resemblance in Wittgenstein's sense (Stoljar Reference Stoljar and Witt2011, 41).

(W) S is a woman iff S is a human being with enough female traits, and the trait of having a self-determined female gender identity is sufficient but not necessary.

A trans woman identifies as a woman and satisfies (W) even if she has many male traits. Additionally, an intersex woman who identifies as female, with some female and some male traits, satisfies (W). Some nonbinary persons who identify temporarily as female satisfy (W) at a particular time t. A self-determined female gender identity is a super trait that is sufficient for being a woman but is not necessary (newborns and other people are unable to express their gender identity), and it does not fully explain the idea of being a woman. A kind of hermeneutical circularity occurs between the notion of female gender identity and the notion of a female trait. Female identity gets its content from social patterns of being a woman with female traits, but a female trait is the trait that frequently occurs within the group of people identifying as women. The notion of female gender identity (first-person perspective) and the notion of female traits (third-person perspective) are complementary, and both are needed to define the notion of a woman.

Challenging the Binary Model of Gender/Sex

This article challenges the binary model of gender/sex. The reason to reject the binary model of gender/sex is the epistemic injustice suffered by people with intersex traits or nonbinary identities who are inadequately conceptualized and to deliver counterexamples to that model.

The gender/sex concept is fragmented into nine layers, and examples of nonbinary traits (neither female nor male) on every layer are listed. The examples create a nonbinary category across all layers and a nonbinary model of gender/sex (Table 1). Additionally, the application of the model to individuals provides examples of clusters of traits for which one layer is female and another is male.

The nonbinary category takes its name from the existing category of nonbinary gender identity; however, here, it has a technical meaning and refers to any trait or cluster of traits that is neither female nor male. The nonbinary category in this model is a category of traits and not of people. It is not a simple, third gender/sex but a challenge to the binary model that is considered to be a step toward a continuum model.

I responded to the thesis that social gender structure is binary (Barnes Reference Barnes2019) and that the biological divide between females and males is binary (Byrne Reference Byrne2020). In both cases, the female and male reproductive roles were considered to be the source of the binary model. I answered that with IVF technology, reproduction is fragmented into more than two roles (egg donor, sperm donor, gestational surrogate mother, two genetic mothers, trans man as gestational mother, a woman as sperm donor, one intersex person as egg and sperm donor). I claim that nonbinary language and legislation following knowledge about a biological and psychological continuum are signs that the binary gender structure is changing into a nonbinary one. I have rejected Byrne's idea of the “bio woman,” as on the level of biological sex characteristics, there is no clear boundary between female and male traits (examples in Tables 2–4).

Under this model, being a woman, a man, or a nonbinary person can be conceptualized as a cluster of traits. A woman is a human being with enough female traits, and female gender identity is a female trait of such importance that it is sufficient for being a woman. Trans women and intersex women meet the condition, and nonbinary identities reveal temporary female identities.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Center, Poland (grant number 2014/15/B/HS1/03672)]. I wrote this article during my stay as a visiting research fellow at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Gender Studies, University of Leeds, UK (February–May 2016) and as a visiting scholar in the Department of Philosophy and the Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality, University of Chicago (April–May 2017). I am grateful for the remarks and suggestions from Sally Hines, Benjamin Vincent, Danya Lagos, Simone Emmert, Maren Behrensen, Surya Monro, Marzena Adamiak, and others, especially the anonymous referees of Hypatia.

Renata Ziemińska is Professor of Philosophy at the University of Szczecin, Poland. Her research includes questions of epistemology, feminist philosophy, and gender studies. Recently, she published “Argumentative Strategies of Pyrrhonian and Academic Skeptics” and “The Epistemic Injustice Expressed in ‘Normalizing’ Surgery on Children with Intersex Traits.”