Low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) face a dual epidemic of under- and over-nutrition in women of reproductive age. This has a direct impact on the immediate outcome for the mother and newborn, and long-term effects on the child through to adulthood(Reference Black, Victora and Walker1–Reference Victora, Adair and Fall3). In the context of this nutrition transition, the new trends in over-nutrition have been linked to greater access to and consumption of energy-dense diets high in fats, tobacco use and increasingly sedentary lifestyles(4–Reference Popkin6). Persistent problems with under-nutrition are now exacerbated by a rapid rise in overweight and obesity and concomitant rise in diet-related chronic disease(Reference Black, Victora and Walker1, Reference Dans, Ng and Varghese5, Reference Stevens, Singh and Lu7).

These problems are particularly felt in Asian populations that are at increased risk of diet-related non-communicable disease (CVD, stroke, hypertension and diabetes) for similar measures of nutritional status compared with Western populations(Reference Stevens, Singh and Lu7–Reference Woodward, Huxley and Ueshima9). Globally, and increasingly within Asia, trends in BMI and gestational weight gain (GWG) are important determinants of disease related to nutrition in pregnancy: overweight and excessive GWG can lead to gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes and macrosomia complicating delivery, while being underweight in pregnancy is associated with pre-eclampsia, intra-uterine growth restriction and low infant birth weight(Reference Aune, Saugstad and Henriksen10–Reference Wells16). Furthermore, we continue to learn how the nutritional status of the mother and its relation to the intra-uterine environment leads to intergenerational, long-term effects on non-communicable disease incidence in adulthood, perpetuating a cycle of risk(Reference Black, Victora and Walker1, Reference Hanson and Gluckman17).

The nutrition transition and epidemiological shift from infectious diseases such as malaria to a larger burden of diet-related non-communicable disease – a new development over the past 20 years – is well underway in Asia, including places such as Thailand(4, 8, Reference Aekplakorn18–Reference Saito, Keereevijit and San20). A 2011 study showed that 40·0 % of reproductive age women are estimated to be overweight and 11·1 % obese in Thailand, with women in neighbouring Myanmar approaching 47·0 % overweight and 11·3 % obese – likely underestimates as the BMI categories used were not adjusted for Asian populations(Reference Dans, Ng and Varghese5).

Although the nutrition transition is well underway in LMIC settings, there remains a paucity of data documenting trends in nutritional status of marginalised populations in these contexts, particularly for pregnant refugee and migrant women. Most of the published data on these populations come from refugee and migrant populations resettled in high-income countries(Reference Berkowitz, Fabreau and Raghavan21, Reference Dawson-Hahn, Pak-Gorstein and Matheson22). With a growing global need to address the health of refugees, displaced persons and migrant communities in both LMIC and high-income countries, we examine changes in nutritional status among pregnant women from the Thailand–Myanmar border: in the setting of a protracted refugee situation and among a large and growing migrant worker population from Myanmar. The objective of this manuscript is to describe trends in over- and under-nutrition using weight (1986–2016) and BMI at first antenatal presentation (2004–2016) and GWG (2004–2016) in these marginalised populations.

Methods

A brief history of the Shoklo Malaria Research Unit and populations along the Thailand–Myanmar border

Refugee populations

Mass movement of persons from Myanmar began in 1984 as ‘persons fleeing fighting’ amassing in informal shelters along the border region were permitted entry into neighbouring Thailand through formalised ‘temporary shelters’(Reference Huguet and Chamratrithirong23). The Border Consortium, tasked with providing basic services to refugees along the border, documented a peak in this population at 165 901 in 2006, housed in ten temporary shelters within Thailand(24). The Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU) began work in the Shoklo refugee camp in 1986, which was closed in 1998 and amalgamated to Mae La refugee camp where it is currently the most populous of the remaining nine refugee camps. As of December 2016, the Border Consortium aided 37 518 persons living in Mae La(25). More than 90 % of the refugee pregnant population in Mae La received antenatal care (ANC) services at the SMRU clinic and more than 75 % of women delivered at the SMRU birth centre(Reference Fellmeth, Plugge and Paw26–Reference Luxemburger, McGready and Kham28).

Karen are the predominant ethnic groups(24, Reference Luxemburger, McGready and Kham28), comprised primarily of Sgaw and Pwo Karen, and religious affiliations are predominantly Buddhist or Christian, but with a significant proportion of Muslims, who also generally self-report their ethnicity as ‘Muslim’. Literacy rates among the pregnant women in Mae La camp have remained stable around 50 %(Reference Carrara, Hogan and Pree29). Refugees from Myanmar have historically had poor access to maternal health services; however, once in Thailand refugees have access to food assistance and medical services within refugee camps but are barred from work(Reference Boel, Carrara and Rijken30–Reference Parker, Carrara and Pukrittayakamee32).

Migrant populations

Informal networks of low-skilled, migrant labour developed along the Thailand–Myanmar border in the context of persistent economic hardship within Myanmar coupled with lax labour law enforcement in neighbouring Thailand(Reference Huguet and Chamratrithirong23). Migrants have limited access to health services within Thailand(Reference Huguet and Chamratrithirong23, Reference Mullany, Lee and Yone31–33). In the face of a growing migrant population with a significant burden of malaria, SMRU began ANC for migrants in Maw Ker Thai village in 1998, south of SMRU headquarters in Mae Sot, and subsequently in the north in Wang Pha village in 2004 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Map of Thailand–Myanmar border showing locations of Shoklo Malaria Research Unit (SMRU) antenatal care (ANC) clinic sites. Includes active sites as of December 2016 (Mae La, Wang Pha, Maw Ker Thai). Credit to Myochit Min.

As of December 2009, the Thailand Ministry of Interior counted nearly 1·1 million registered migrant workers from Myanmar, of which 45 % were women. SMRU estimates that its clinics serve a catchment of approximately 200 000 migrants that has remained relatively stable since the late 1990s(Reference Carrara, Lwin and Phyo34). The predominant ethnic groups among migrants are Burman and Karen (Sgaw and Pwo). They are predominantly Buddhist. Approximately 45 % of migrant women presenting for ANC are literate(Reference Carrara, Hogan and Pree29).

Shoklo Malaria Research Unit antenatal care and labour and delivery services

Home birth with traditional birth attendants remained widely practised in the refugee camps when SMRU began its ANC and obstetric programme, with SMRU promoting facility-based deliveries with trained midwives beginning in 1994(Reference McGready, Boel and Rijken35). Ultrasound was introduced in 2001 using Dynamic Imaging, Fukuda Denshi UF 4100 (since 2002) and Toshiba Powervision 7000 machine (Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan since 2006), all with a 3·75-MHz convex probe, with all women routinely offered two scans. The booking visit scan (between 8 and 14 weeks’ gestation) calculates estimated gestational age (EGA) by crown–rump length measurement using the British ultrasound guidelines and with regular quality control in place(Reference Rijken, De Livera and Lee36, Reference Rijken, Lee and Boel37). Labour and delivery wards were established in Wang Pha in 2008 and Maw Ker Thai in 2010. SMRU’s entire operation has grown to include locally trained medical assistants, nurses, midwives, sonographers, laboratory technicians, home-visitors and a small number of expatriate doctors, about half of whom are from Myanmar(Reference McGready, Boel and Rijken35).

Study design

Anonymous digital clinical records were available from a historical cohort of 72 622 pregnant women presenting to SMRU ANC between January 1986 and December 2016. A series of analyses were performed to assess: weight at first ANC, BMI in the first trimester (<14 weeks’ gestation) and GWG. We included women with appropriate EGA and delivery of live, term (37–41 completed weeks), congenitally normal, singleton newborns. All analyses excluded women with spontaneous abortions, lost to follow-up before pregnancy outcome was known and inaccurate EGA or weight measurements. BMI analysis included only those women with weight and height measurements at first ANC visit. GWG analysis included women with last weight measured between 34 and 41 completed weeks and Karen (Sgaw and Pwo Karen) and Burman ethnicity.

Variables available for analysis

Anthropometric variables

Trained midwives measured weight at first ANC consultation and at each follow-up visit by mechanical scale with 0·5 kg precision on Salter medical grade scales. Maternal weight at delivery was defined as the last weight taken between 34 + 0 and 41 + 6 weeks of gestation. Standing mechanical scales were available at the main clinic, but weight scales purchased locally in 2002 and 2003 were excluded from this analysis as they gave significantly higher weights (2–3 kg) compared with other years included in this analysis.

Height measurement at first ANC was introduced in 2004 using a portable, mechanical stadiometer with 0·5 cm precision, with newer digital, stationary stadiometers allowing for precision up to 1 mm since 2010, using the SECA brand. Both weight and height measurements were taken according to standard procedures(38).

BMI was calculated when both weight and height measurements were available, beginning in 2004. BMI for this analysis was categorised as defined by the WHO expert consultation on Asian populations: low (BMI <18·5 kg/m2), normal (BMI 18·5–22·9 kg/m2) and high (BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2)(8). Height and weight measurements from the first ANC visit for the first trimester were used to calculate BMI and categorise each woman. It has been shown that first trimester weight as a proxy for pre-pregnancy weight is accurate in up to 95 % of pregnant women(Reference Krukowski, West and DiCarlo39).

GWG was summarised in this cohort and compared with the Institute of Medicine recommendations for pre-pregnancy BMI and GWG(40). In addition, BMI and GWG in this cohort were also compared with a cohort of healthy pregnant Asian women in Vietnam using Asian WHO criteria, as this population was considered similar to the population analysed here(Reference Ota, Haruna and Suzuki15).

Estimation of gestational age

Different techniques were used to calculate EGA over the course of this historical cohort. Fundal height was used until 1992, followed by the Dubowitz method of neonatal assessment. Beginning in 2001, ultrasound became the preferred method of calculating EGA, with Dubowitz used for those women without a reliable dating ultrasound (e.g. late ANC attenders)(Reference Luxemburger, McGready and Kham28, Reference Rijken, Lee and Boel37, Reference Dubowitz and Dubowitz41). The variation in EGA between these methods in this population is minimal(Reference Moore, Simpson and Thomas42).

Demographic, malaria and haematocrit variables

Available demographic variables collected at first ANC were: length of residency at current address, refugee or migrant status, age, gravidity and parity. In 1999, self-report of smoking status (cigarettes or cheroots) was added as a dichotomous variable. Beginning in 2010, women self-reported literacy as ‘able to read’ and ‘able to write’. Clinical data included malaria infection (any species) and anaemia (haematocrit less than 30 %) at first ANC visit.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed according to data type (continuous or categorical) and distribution (normal or skewed). Univariate analysis determined associations between demographic variables and nutritional status indicators. Proportions were calculated as the number of refugee or migrant women with low, normal or high BMI that year, over the total number of refugee or migrant women with a BMI measurement in the first trimester that year. Patterns over time (unit = 1 year) were assessed using a non-parametric test for trend for ordered groups (an extension of the Wilcoxon rank-sum test) or using a 1-df test for trend. Average changes in weight or BMI per 5-year intervals were estimated using linear regression. Comparisons were made using the normal BMI group as the reference group against the low or high BMI group. To identify significant predictors of low or high BMI, factors significant on univariate analysis (P < 0·05) were included in multivariate logistic regression models: age (<20 years), length of residence (months), ethnicity (Karen, Muslim, Burman or others), refugee or migrant status, parity (gravidity 1 and parity 0 v. all others), malaria infection at any time during pregnancy, anaemia (yes/no), smoking status (yes/no) and literacy (can read or not). Associations were quantified as adjusted OR (AOR) with 95 % CI. Data were analysed using STATA, version 14.2 (StataCorp).

Ethical standards

The present study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee (OXTREC 28–09, amended 19 April 2012). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. This research also received ethical approval from the Tak Province Community Advisory Board, Thailand (reference: TCAB-9/2/2015).

Results

A total of 52 222 pregnant women had known gestational age and delivered a singleton, term, live newborn. There were 4160 (8·0 %) women excluded: 3341 with inaccurate weight measurements from 2002 to 2003 and 819 for whom first trimester weight was not measured. Of the 48 062 women included in the analysis, 32 507 (67·6 %) were refugees and 15 555 (32·4 %) migrants (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Study flow. ANC, antenatal care; GWG, gestational weight gain; wt, weight.

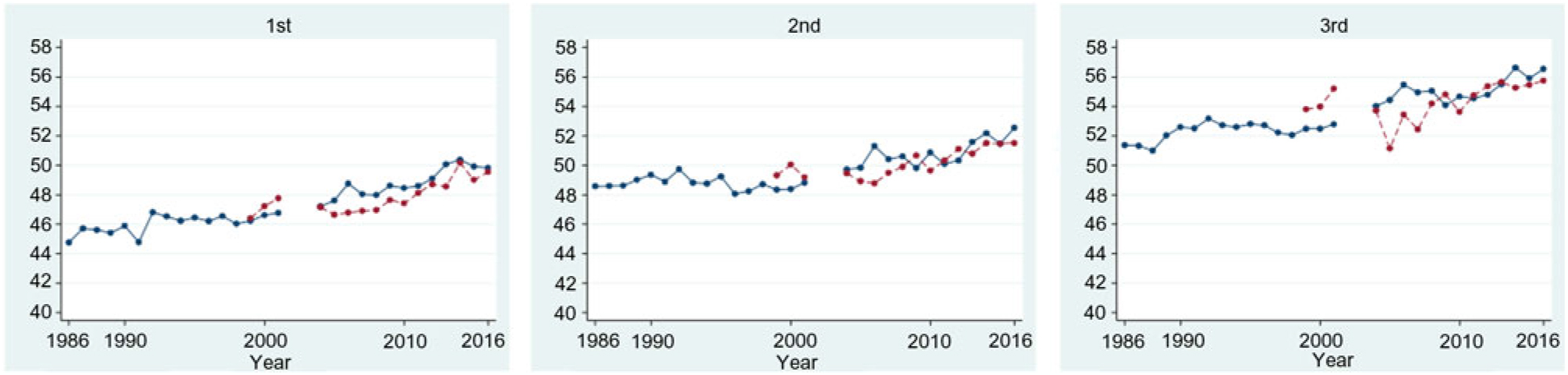

Weight at first antenatal care visit

Among women with first ANC weight available, the proportion of first ANC visits was highest in the first trimester (n 21 155, 44·0 %), followed by the second (n 19 307, 40·2 %) and third (n 7600, 15·8 %) trimesters. The difference in mean weight at first ANC visit increased over the 30-year study period (1986–2016) in refugees for first, second and third trimester by: 5·1 (se 2·2), 4·0 (se 1·2) and 5·2 (se 1·8) kg; and over the 18-year period (1998–2016) in migrants by: 3·2 (se 1·0), 2·2 (se 1·0) and 2·0 (se 1·3) kg (significant for trend P < 0·001, all six groups) (Fig. 3). Every 5 years, weight at first ANC visit increased by an average of 0·9 kg in refugees who presented in the first trimester (95 % CI 0·81, 0·99), by 0·5 kg (95 % CI 0·47, 0·62) and by 0·8 kg (95 % CI 0·65, 0·90) for those who first presented in the second and third trimesters. Trends were similar in migrants with an average increase every 5 years in women presenting in first, second or third trimesters of: 1·0 kg (95 % CI 0·79, 1·26), 0·90 kg (95 % CI 0·67, 1·12) and 0·90 kg (95 % CI 0·52, 1·28), respectively.

Fig. 3. Mean weight of refugee (blue, —) and migrant (red, ---) women, by trimester of first antenatal care presentation. Note: 2002–2003 data excluded due to inaccuracy in weight assessment. For a colour figure, see the online version of the paper.

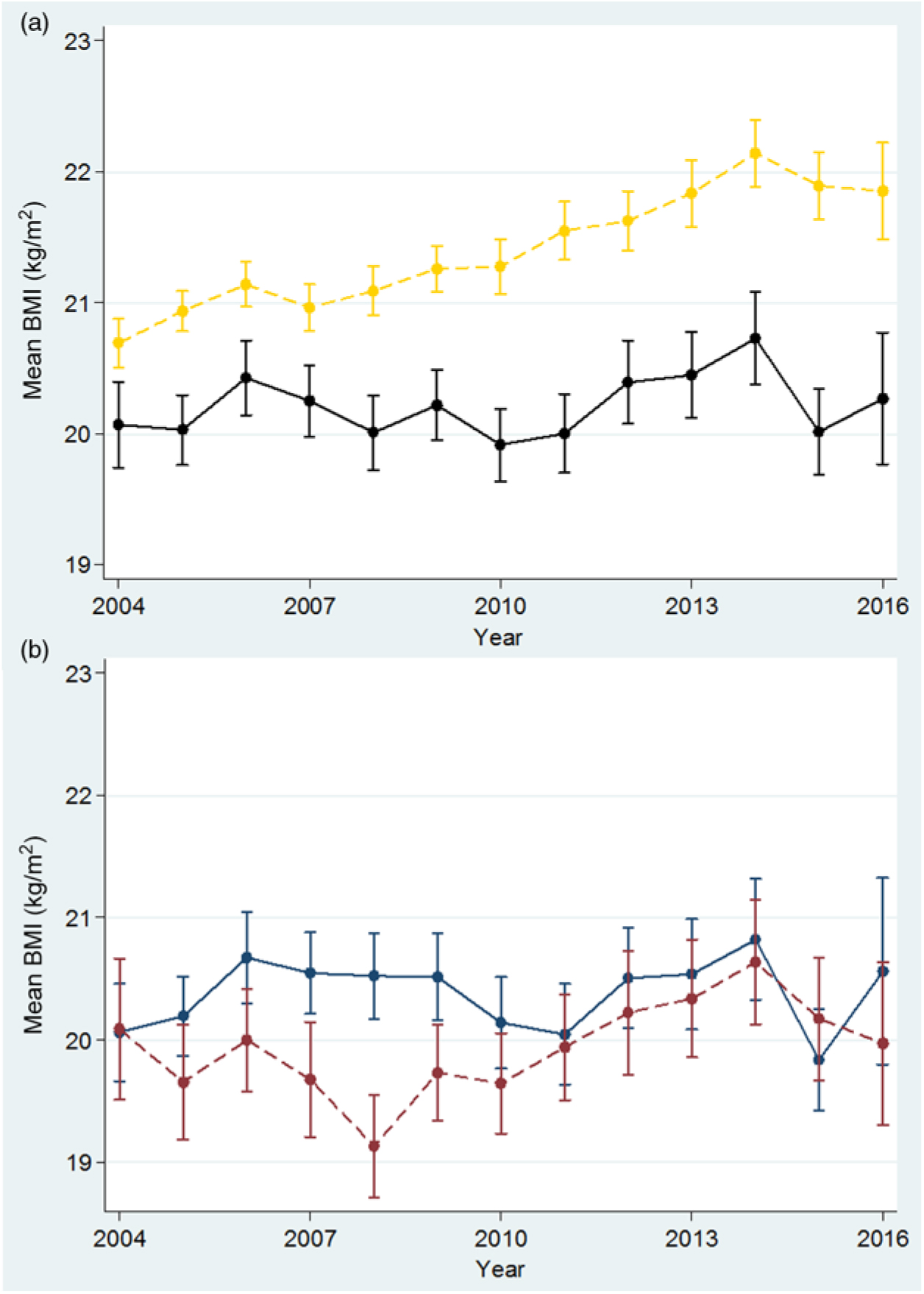

Mean BMI

For BMI data (n 31 243 women) from 2004 onwards, the proportion of first ANC visits was also highest in the first trimester (14 646, 46·9 %), followed by the second (11 537, 36·9 %) and third trimesters (5060, 16·2 %). BMI data were analysed for 9022 (61·6 %) refugees and 5624 (38·4 %) migrants who presented in the first trimester. Mean first trimester BMI (n 14 646) showed a similarly increasing trend over the years for both refugees and migrants (P < 0·001, for both) (Fig. 4). First trimester BMI increased by an average of 0·5 kg/m2 (95 % CI 0·38, 0·57) for refugees and 0·6 kg/m2 (95 % CI 0·50, 0·72) for migrants every 5 years over the 13-year period.

Fig. 4. Mean BMI in first trimester among pregnant refugees (blue, —) and migrants (red, ---). For a colour figure, see the online version of the paper.

From 2004 to 2016, the mean BMI increased significantly in adults (n 12 070, P < 0·001) but not in teenagers (<20 years) (n 2576, P = 0·256), whose BMI was lower than in adults and showed minimal variation from 2004 to 2016 (Fig. 5(a)). Amongst teenagers (1543 refugees and 1033 migrants), the mean BMI (Fig. 5(b)) fluctuated around 20 kg/m2, demonstrating a significant increase for migrants (P = 0·006) but not for refugees (P = 0·936).

Fig. 5. Mean BMI in first trimester among adult (≥20 years) and teenage (<20 years) women. (a) Adults: yellow, ---; teens: black, —. (b) Refugee teens: blue, —; migrant teens: red, ---. For a colour figure, see the online version of the paper.

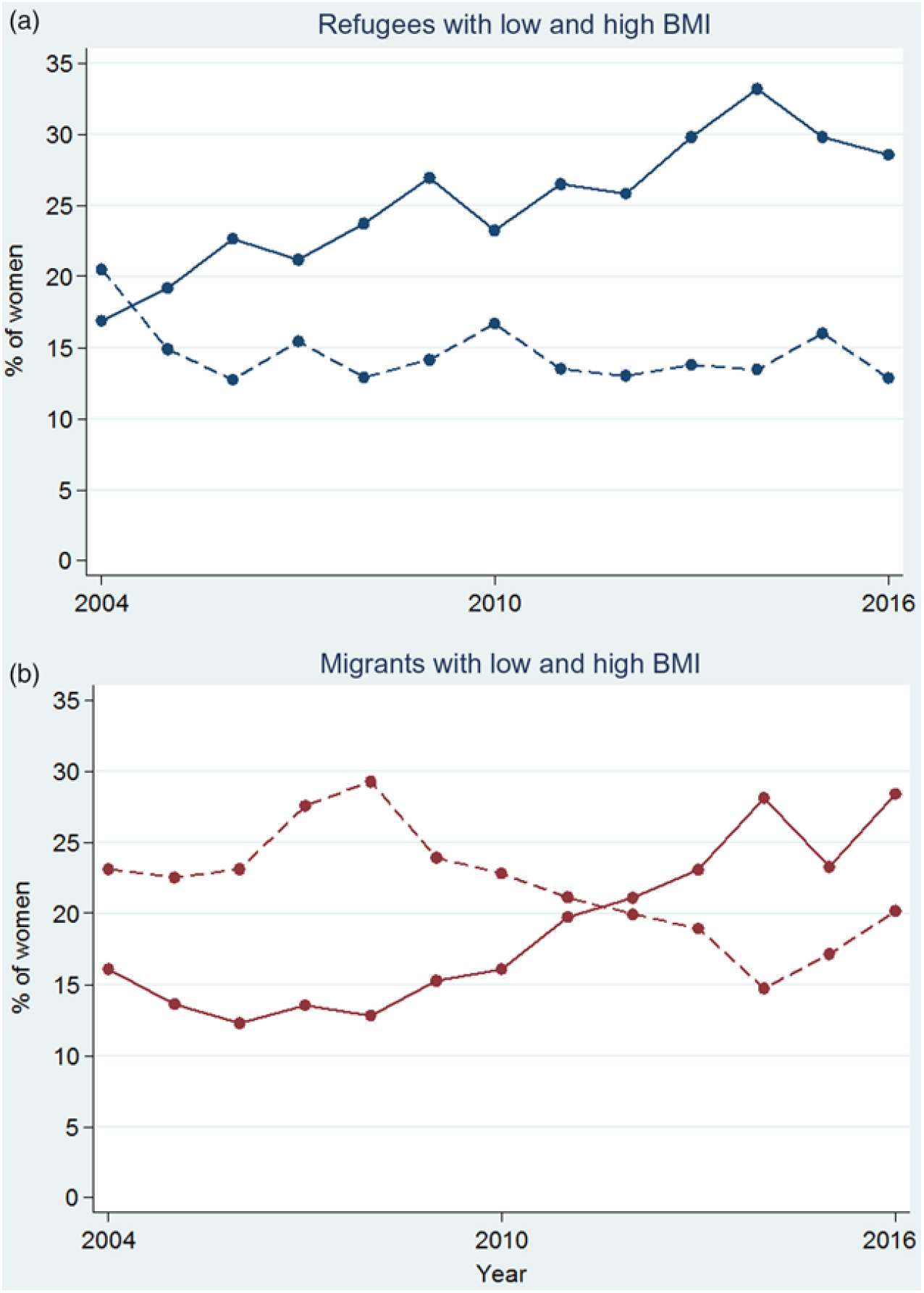

Comparisons of low, normal and high BMI

Overall, there were 17·5 % (2568), 60·6 % (8870) and 21·9 % (3208) of women in the Asian BMI categories of low, normal and high BMI, respectively. The proportion of women with low BMI decreased over time in both refugees and migrants (Fig. 6). Although there was an overall decreasing trend in the proportion of refugee women with low BMI (P = 0·020), it appeared to be driven by a peak in low BMI in 2004 (Fig. 6(a)). From 2005 to 2016, the proportion of refugee women with low BMI varied from 16·7 % to 12·7 %, with no discernible increasing or decreasing trend (P = 0·945). The proportion of migrant women with low BMI decreased from 23·1 % to 20·2 % (P < 0·001, trend from 2004 to 2016). In both refugees and migrants, there was a 2-fold increase in the proportion of pregnant women with high BMI in the first trimester in 13 years: from a low of 16·9 % to a high of 33·2 % in refugees (Fig. 6(a)) and from a low of 12·3 % to a high of 28·4 % for migrants (Fig. 6(b)) (P < 0·001 for both trends from 2004 to 2016).

Fig. 6. Proportion of low (---) and high (—) BMI for refugee (a) and migrant (b) women presenting at first antenatal care visit in the first trimester. For a colour figure, see the online version of the paper.

Using normal BMI as the referent group, maternal characteristics associated with low and high BMI were evaluated in univariate and multivariate analysis (Table 1). Variations in BMI and ethnicity were significant by univariate analysis (Table 1), and this was maintained in multivariate analysis (Table 2). Burman women (AOR 1·49, 95 % CI 1·23, 1·81), Muslim women (AOR 1·64, 95 % CI 1·26, 2·13), primigravid women (AOR 1·28, 95 % CI 1·10, 1·49), malaria infection during pregnancy (AOR 1·55, 95 % CI 1·01, 2·37) and smoking (AOR 1·38, 95 % CI 1·12, 1·71) demonstrated increased odds of low BMI when compared with the normal BMI group (Table 2). Refugee women were less likely to have low BMI (AOR 0·82, 95 % 0·70, 0·97). Muslim women (AOR 1·94, 95 % CI 1·58, 2·39), literate women (AOR 1·19, 95 % CI 1·05, 1·35) and those with longer residency (AOR 1·02, 95 % CI 1·01, 1·03) were at increased odds for high BMI. Teenage women (AOR 0·42, 95 % CI 0·34, 0·52), primigravid women (AOR 0·47, 95 % CI 0·40, 0·56), malaria infection during pregnancy (AOR 0·35, 95 % CI 0·17, 0·74), anaemia during pregnancy (AOR 0·54, 95 % CI 0·30, 0·97) and smoking (AOR 0·60, 95 % CI 0·48, 0·73) had decreased odds of high BMI when compared with the normal BMI group.

Table 1. Maternal characteristics and association with low and high BMI (normal BMI as referent) for a total of 14 646 pregnant women from 2004 to 2016

(Numbers of participants and percentages; medians and interquartile ranges (IQR))

Table 2. Multivariate logistic regression for maternal characteristics and association with low and high BMI (normal BMI as referent with 4989 and 5520 women included in low and high BMI models, respectively) for pregnant women from 2004 to 2016* (Adjusted odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals)

* All variables listed in the table were included in the models, with models stratified by year.

† Karen ethnicity used as referent, as this is the predominant ethnic group over the duration of the study period.

‡ Migrants used as referent.

Gestational weight gain

Of the 14 646 women with BMI measured in the first trimester, 7098 were included in the GWG analysis. Mean GWG was 10·0 (sd 3·4, range −1·0 to 24·0), 9·5 (sd 3·6, range −6·0 to 24·1) and 8·3 (sd 4·3, range −4·8 to 25·0) kg for low, normal and high BMI, respectively, with some women losing weight over the course of their pregnancy. GWG was compared with international recommendations from Institute of Medicine for appropriate GWG ranges determined by pre-pregnancy BMI(40). Women with low or normal BMI in this cohort fell short of Institute of Medicine recommendations for GWG (Table 3). In addition, GWG in this cohort was compared with population means from a Vietnamese cohort of healthy pregnant women, which were analysed based on Asian BMI categories (Table 3). GWG for women in the present study was lower for each Asian BMI category than the Vietnamese cohort(Reference Ota, Haruna and Suzuki15).

Table 3. Comparison of gestational weight gain (GWG) and first trimester BMI with Institute of Medicine (USA) (IOM) recommendations and Asian BMI categories as reported from an Asian population (Vietnam)

IQR, interquartile range; SMRU, Shoklo Malaria Research Unit.

* WHO BMI categories consistent with IOM comparison(40).

† WHO BMI categories for Asian populations(8) and consistent with Ota et al. (Reference Ota, Haruna and Suzuki15).

Discussion

The present study offers a unique perspective: it documents trends in nutritional status of marginalised populations of pregnant women in a protracted refugee situation and among migrants in a socially, politically and economically turbulent region in Southeast Asia. Taken from over 40 000 women and with data spanning 30 years in refugees and 19 years in migrants along the Thailand–Myanmar border, the present study adds to the literature due to its size and scope. It adds to the dearth of literature highlighted by a study of thirty-seven LMIC, by summarising important trends in nutritional status of pregnant women within a marginalised population in an LMIC context(Reference Razak, Corsi and Subramanian43), against the backdrop of a nutrition and epidemiological transition.

The trends toward overweight in these marginalised communities of refugees and migrants along the Thailand–Myanmar border reflect global trends(Reference Black, Victora and Walker1) and present significant challenges. In 2004, 16·6 % of refugee and migrant women had a high BMI (≥23 kg/m2). By 2016, over one-fourth (28·5 %) had BMI ≥23 kg/m2 and 6 % of the women included in the present study had BMI ≥27 kg/m2, putting them at higher risk of pregnancy and delivery complications and poor perinatal outcomes as demonstrated elsewhere in Asia(Reference Ee, Allen and Malhotra11, Reference Liu, Dai and Dai13, Reference Ota, Haruna and Suzuki15, Reference Koh, Ee and Malhotra44, Reference Koyanagi, Zhang and Dagvadorj45). We observed this increase in overweight and obesity among both refugees and migrants, with an earlier and more pronounced trend among refugees. Here, we briefly outline a few considerations for these trends, including underlying biology, access to foods of varying nutritional quality, and the social, economic and political context along the border within which we observe these nutritional trends. The ‘Developmental Origins of Adult Disease’ may help explain this trend(Reference Gluckman, Hanson and Cooper46, Reference Hales and Barker47). This hypothesis posits that under-nutrition in early life leads to increased risk of diet-related chronic disease later in life. As we cover a generation by study end, we may be witnessing this ‘programming’ effect among pregnant women with high BMI linked to malnutrition in early life. However, these trends would not be possible without being enhanced by environmental and behavioural factors(Reference Li, Ley and Tobias48, Reference Wells, Pomeroy and Walimbe49). The ‘nutrition transition’ documented in Thailand and in Asian populations elsewhere provides evidence of overweight and obesity and their association with increasingly sedentary lifestyles and diets high in animal and saturated fats, sweetened beverages and industrially and locally processed foods(4, Reference Dans, Ng and Varghese5, Reference Popkin6, Reference Kosulwat19). A recent study in this population links sweetened beverage consumption within the prior 24 h with high BMI in pregnancy(Reference Hashmi, Paw and Nosten50), with more controlled studies needed to understand the effects of other processed foods on maternal nutrition and pregnancy outcomes in this population. With the nutrition transition well underway in Thailand and its effects more pronounced among the marginalised, the introduction of and easier access to unhealthy, processed foods is compounded by limited access to health information through media; language barriers; low literacy and health literacy among pregnant women; and a lack of awareness among health workers and the communities as to the ill effects of poor nutrition(Reference Hashmi, Paw and Nosten50, Reference Aung, Lorga and Srikrajang51–Reference Lorga, Srithong and Manokulanan53).

Trends and differences in nutritional status in refugees and migrants – namely in relation to risk factors for low and high BMI – can also be considered in the context of fluctuating political and civil stability along the border. Periods of stability are marked by more consistent access to health care services, education and greater food security, more clearly documented for refugees compared with migrants(Reference Carrara, Hogan and Pree29, Reference Parker, Carrara and Pukrittayakamee32, Reference Parmar, Barina and Low54, Reference Srikanok, Parker and Parker55). As far as the authors are aware, this is the largest cohort demonstrating a significant association with low BMI and malaria among pregnant women(Reference Cates, Unger and Briand56) and, therefore, the history of malaria control efforts along the border over the present study period bears mentioning. Between 2004 and 2008, the higher incidence of malaria among migrants and its association with the nutritional status of pregnant women occurred over a period marked by a fraught ceasefire process in Eastern Myanmar and continued political and civil instability leading to greater disruption of access to health services. Active malaria programmes could be established more easily in refugee camps, leading to greater malaria reduction and its concomitant reduction in risk of low BMI among refugees, while less effective programming allowed malaria to persist in the more mobile migrant communities over the same time period(Reference Parker, Landier and Thu57). Occupational and behavioural risk factors and inadequate housing conditions common among seasonal migrants in the border region likely exacerbated these trends(Reference Mullany, Lee and Yone31, Reference Parker, Carrara and Pukrittayakamee32, Reference Luxemburger, Ricci and Nosten58). Although recognising that this is not a complete explanation for trends in nutrition among these marginalised groups, the authors view fluctuating political and civil stability as contributing to the observed trends.

Therefore, alongside the relative political and civil stability seen in the refugee camps beginning in 1998, we observe an increase in the proportion of refugee women with high BMI. Earlier studies on nutritional status in this refugee population implicate limited dietary diversity and poor food security as risks for low BMI(Reference Banjong, Menefee and Sranacharoenpong59–Reference Stuetz, Carrara and McGready61). However, with greater food security through provided rations, studies have demonstrated trends in improved maternal micronutrient status among refugees and improved birth outcomes(Reference Carrara, Stuetz and Lee60, Reference Stuetz, Carrara and Mc Gready62). Stuetz et al. demonstrated that ownership of livestock and gardens in addition to food rations was significantly associated with improved refugee maternal micronutrient status(Reference Stuetz, Carrara and Mc Gready62). These findings reflect greater stability in living and livelihood in the refugee communities. In addition, restrictions on field work outside the camps and an accompanying decrease in physical activity lend risk for sedentary lifestyles associated with over-nutrition in this population. The relative risks for poor nutrition attributable to long-standing armed conflict, occupational and behavioural risk factors, unstable residency, food insecurity and limited health care access are far from clear. However, the suggestion that nutritional trends follow fluctuations in stability in this region over time may shed light on similar dynamics in areas of conflict elsewhere in developing contexts.

However, even as malaria, anaemia and smoking during pregnancy as risk factors for low BMI have decreased over time, the overall rates of low BMI still persist. Therefore, the present study adds to the literature on the double burden of malnutrition in LMIC settings. Although the present study did not find an association between teenage pregnancy and low BMI (likely due to the small sample size), we note that teen pregnancy hovers consistently around 20 % over the study period and has been demonstrated to be associated with low BMI and under-nutrition in a larger cohort in this same population(Reference Parker, Parker and Zan63). Therefore, as a risk factor for low BMI, programming around maternal nutrition in communities along the Thailand–Myanmar border may do well to pay specific attention to teen pregnancy for the reduction in the burden of maternal underweight.

The present study is not without limitations. Given that this analysis takes place over a long period of time, the variables analysed have been assessed through different methods over the course of SMRU’s work in the region, reflecting the most accurate methods of anthropometric data collection given logistical constraints and changes in appropriate assessments over time. For example, missing data from 2002 to 2003 are due to problems with weight scales that were corrected in 2004. Despite these challenges, the large sample size allows for a robust characterisation of changes in nutritional status among these refugee and migrant populations. The authors note that the present study may have limited generalisability as this is specific to Myanmar refugees and migrants, but hope that the basic indicators of weight and BMI presented here will prove useful for other crisis situations globally. In addition, these findings may help inform the care of pregnant women in high-income countries receiving refugees and migrants from LMIC by providing a plausible context for understanding nutritional status of refugee and migrant women and targeting care to ameliorate the effects of poor nutrition on pregnancy outcomes.

As the double burden of underweight and over-nutrition has been linked to complications in pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes in Asian populations, future analyses will assess optimal BMI and GWG in relation to pregnancy outcomes among refugee and migrant populations along the Thailand–Myanmar border.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the pregnant women who voluntary agreed to have their data collected over the past 30 years and the SMRU ANC and midwifery staff responsible for the care of these pregnant women over the years.

This study was funded as part of the Wellcome-Trust Major Overseas Programme in Southeast Asia (grant number: 106698/Z/14/Z). Supplementary funds were also provided by the John Fell Oxford University Press (OUP) Fund, UK (project code: B9D00030). The funders had no role in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the article or in submission of the paper for publication. The views expressed in the paper are those of the authors and do not represent the positions of their respective institutions or that of the funding agencies.

A. H., N. S., R. M., V. I. C., F. N., A. M. M. and M. E. G.: conceived and designed the protocol; N. S., S. L. and J. W.: prepared databases and performed statistical analysis; A. H. and N. S.: first draft of the manuscript; E. P., K. W., C. A. and P. C.: provided feedback on the protocol and design, and supported funding applications. All the authors read, contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.