Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia among older adults; it accounts for an estimated 60–80% of cases (Alzheimer’s Association, 2015). In addition to loss of memory and cognition, more than 90% of individuals with AD experience behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS), such as agitation, aggression, depression, hallucinations, and delusions, over the course of their illness (Alzheimer’s Society, 2011; Steinberg et al., Reference Steinberg2008). NPS, also referred to as behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, are associated with increased morbidity, mortality, healthcare use, earlier nursing home placement, and caregiver burden and distress (Porsteinsson et al., Reference Porsteinsson2014). While agitation is common among neuropsychiatric disorders, there was no consensus definition for it until recently—non-specific lay definitions were used (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings2015), making it difficult to compare studies and summarize existing evidence on the burden of agitation. Because of the lack of an accepted definition or assessment tool for agitation, there is a gap in the understanding of the burden of AD specific to agitation. A systematic review of the burden of agitation and NPS can help address this gap in knowledge.

The goal of this systematic literature review (SLR) was to map the existing evidence to better understand the total clinical, humanistic, and economic burden associated with agitation in adult patients with AD. The specific objective of this paper is to describe the results regarding agitation incidence and prevalence, and its association with disease progression and mortality, in adult patients with AD based on results from the broader SLR.

Patients and methods

A systematic literature search, based on a pre-approved Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol and consistent with the PRISMA statement, was conducted for studies published between 2006 and 2016. The search was conducted in MEDLINE (via PubMed) and Embase. In addition, conference proceedings (including websites, posters, and meeting abstracts) from the two most recent meetings (last two years or last two major meetings) were searched for five professional organizations (Alzheimer’s Association—International Conference on Alzheimer’s Disease; International Psychogeriatric Association [IPA]; Alzheimer’s Disease International [ADI]; American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry [AAGP]; International Society of Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research [ISPOR]).

Blocks of medical subject heading (MeSH) terms were used to identify the most relevant articles, research papers, and conference papers that described the clinical burden associated with agitation in AD. Agitation terms were based on the consensus definition of agitation issued by the IPA (Cummings et al., Reference Cummings2015), which includes behaviors that indicate severe emotional distress (e.g., irritability, rapid changes in mood), excessive motor activity (e.g., pacing, rocking, restlessness), physical aggression (e.g., pushing, hitting, kicking), and verbal aggression (e.g., shouting, cursing, yelling)—these behaviors must not be solely attributable to another psychiatric disorder (e.g., depression, psychosis). The focus of this review was specifically on agitation; however, studies that did not explicitly use the term agitation but reported on the behaviors noted above were included. Unless specifically stated otherwise, results are presented as a combination of agitation and related NPS in this report. The search strategy used is presented in Table S1 and Table S2 of the Supplementary Search Strategy Tables file and full list of references in presented in Supplementary Appendix, published as supplementary material online attached to the electronic version of this paper. SLRs were included in the initial search to review the reference list; this was to ensure all additional, relevant papers were included in the review.

All abstracts were reviewed using DistillerSR®, a literature review extraction software, which assists with the organization, extraction, and categorization of the literature. Screening was performed by three trained reviewers at two levels. At Level 1, titles and abstracts of identified records were screened for exclusion criteria (Table 1). Thirty percent of the excluded abstracts were screened by a second, independent reviewer to ensure agreement. At Level 2, full-text articles were screened, and those meeting the eligibility criteria were tabled. The inclusion of all papers into the review was confirmed by a second reviewer. Data abstraction was completed in table format as reported. Qualitative synthesis of the information was conducted. No quantitative summaries were planned.

Table 1. PICOS criteria for burden of agitation in AD

Abbreviations: AD = Alzheimer’s disease; PICOS = population, intervention, comparator, outcomes, study design.

Results

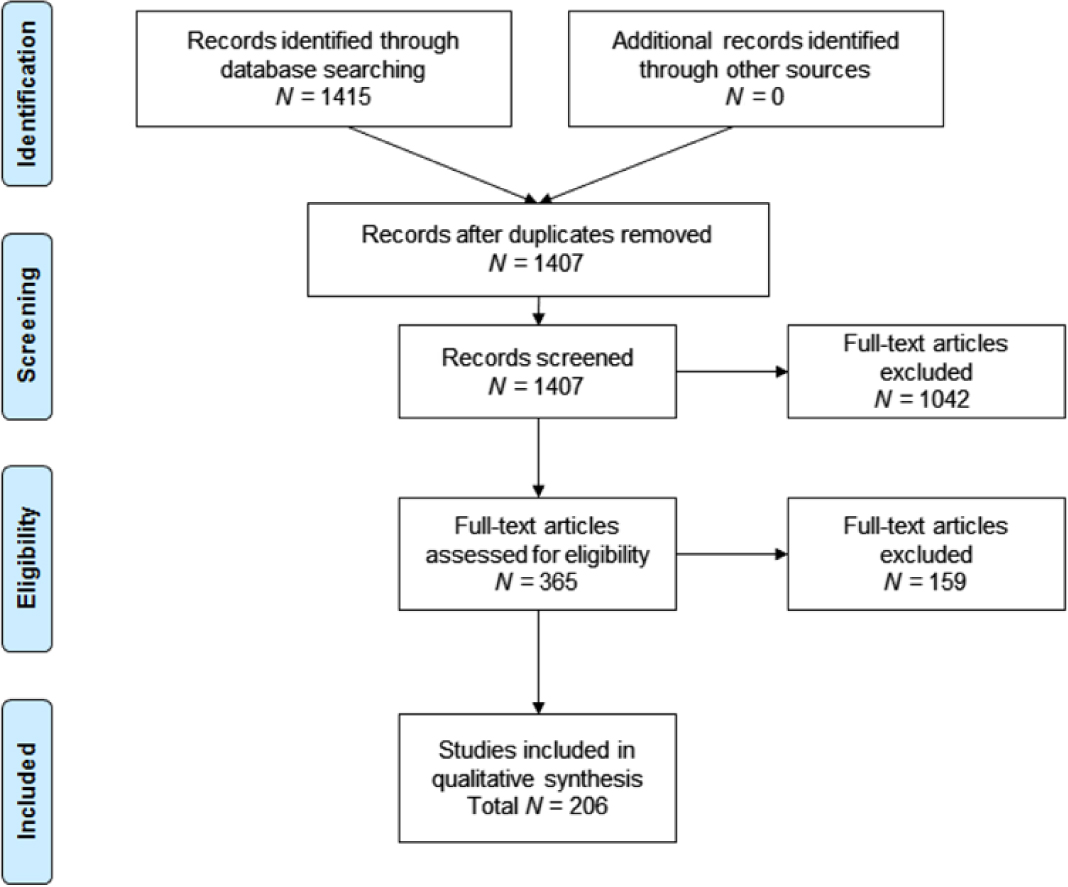

The database search yielded 1,415 references, of which 1,407 remained after duplicates were removed. All 1,407 records were screened based on the protocol-defined criteria—365 were accepted for full-text screening. Of these, 206 papers were included in the final qualitative review of AD agitation burden (Figure 1). Of the 206 studies included in the final qualitative review, those providing information on burden of agitation were summarized by protocol-defined groups. This paper summarizes findings related to incidence (4 papers), prevalence (55 papers), natural progression of agitation symptoms (17 papers), association of agitation and disease severity (34 papers and three conference abstracts), and association of agitation and mortality (5 studies). Publications related to humanistic, caregiver, and economic burden were also reviewed, but results are not reported in this paper (Anatchkova et al., Reference Anatchkova2017).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram: SLR burden of illness associated with agitation in Alzheimer’s disease.

Incidence of agitation/behavioral symptoms in AD

Four studies evaluating the incidence of agitation/behavioral symptoms in AD were identified; three from Norway and one from The Netherlands (Table 2). Incidence was defined in three studies as the proportion of participants who had no NPS at one timepoint but developed them at a later timepoint in the study. Cumulative incidence was defined as the proportion of patients who had no agitation/NPS at baseline, but developed these during the study. Of the three studies conducted in Norway, one identified the cumulative incidence of clinically significant agitation over a 2-year period to be 24.3% (Bergh et al., Reference Bergh, Engedal, Roen and Selbaek2011), the 12-month cohort study found the incidence rate to be 18.8% (Selbaek et al., Reference Selbaek, Kirkevold and Engedal2008), and the 4-year longitudinal study indicated a cumulative incidence rate of 36% (Selbaek et al., Reference Selbaek, Engedal, Benth and Bergh2014). The Netherlands study, which was longitudinal, assessed 2-year incidence of agitation, which ranged from 10.9% to 18.2% (Wetzels et al., Reference Wetzels, Zuidema, de Jonghe, Verhey and Koopmans2010b). All studies used a population sample of nursing home (NH) residents. Studies of incidence of agitation/behavioral symptoms in AD were only published in European countries; no studies of incidence were published in the North American, South American, or Asian regions. In addition, all studies presented findings for patients in nursing homes, while information on incidence of agitation for patients residing at home or seen as outpatients was lacking.

Table 2. Incidence of agitation in AD

Abbreviations: NH = nursing home; NPS = neuropsychiatric symptoms; NR = not reported.

Prevalence of agitation/behavioral symptoms in AD

Fifty-five studies reported the prevalence of agitation and or behavioral symptoms in AD (Table 3). Study types included cross-sectional (n = 31), longitudinal or retrospective longitudinal (n = 23), and before/after study/interrupted time series (n = 1).

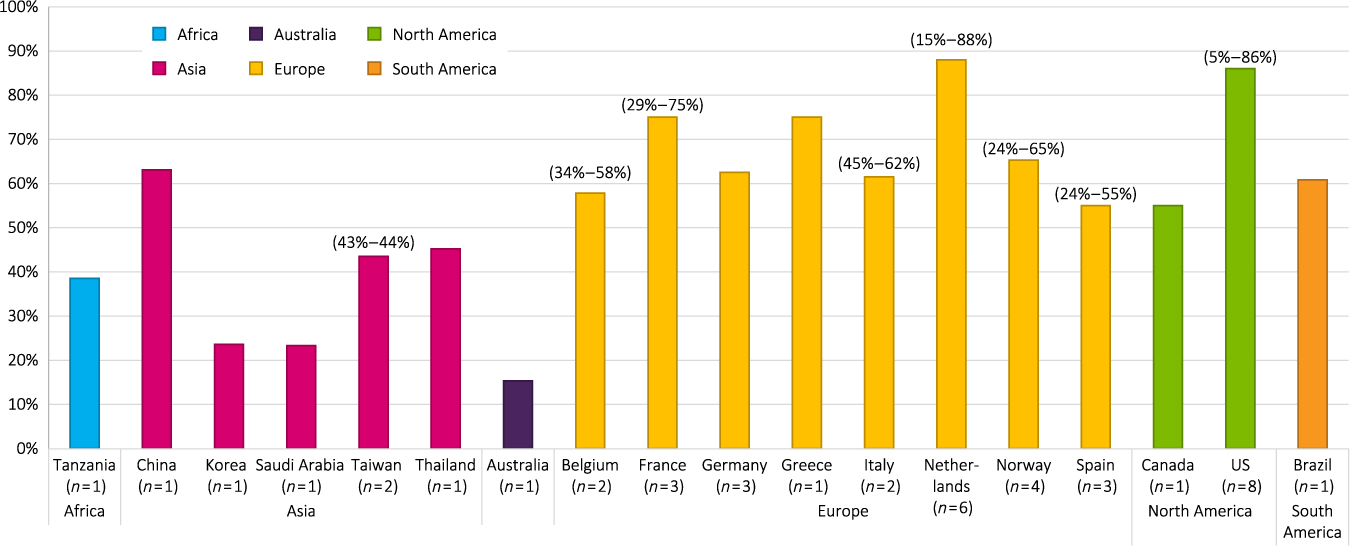

The overall prevalence of agitation ranged from 5% to 88% across all studies (Figure 2), with 21 (38%) showing a prevalence of agitation ≥50%. Twenty-three of the 55 studies (42%) reported prevalence of at least one neuropsychological symptom and reported a range of 40% to 100%. Community-dwelling or outpatient clinic participants were the primary population studied in 26 (47%) studies; NH or group home residents were the primary population in 16 (29%) studies; a combination of NH and community-dwelling participants were the primary population in five (9%) studies; hospital patients were the primary population in five (9%) studies, and three (5%) studies did not report the source of their primary population. Most studies screened participants only for AD (n = 28) or dementia (n = 25), while a couple screened for memory loss/cognitive impairment (n = 2).

Table 3. Agitation studies reporting prevalence, natural progression, and association with AD severity

* One study U.S./Europe.

Abbreviations: AD = Alzheimer’s disease; NPS = neuropsychiatric symptoms; U.S. = United States.

Figure 2. Prevalence of agitation by geographic region. Abbreviation: U.S. = United States.

Prevalence variations by geographical region

Europe

Participants specifically included in the 30 studies (55%) that originated from Europe included participants with AD (n = 14) and dementia (n = 15); one study recruited for cognitive impairment, looking at NPS prevalence rates (Gustafsson et al., Reference Gustafsson, Sandman, Karlsson, Gustafson and Lovheim2013). Of these 30 studies, 15 were cross-sectional (including one retrospective cross-sectional study) and 15 were longitudinal. The range of prevalence of agitation was reported to be 24 % to 88 %, with 14 studies (47%) showing an agitation prevalence rate ≥50%. Sixteen studies (53%) reported prevalence rates of at least one NPS, which ranged from 49.6% to 96.1%. Prevalence rates for agitation in European studies ranged from 24% to 88% for NH or geriatric facility participants (n = 13); 18.6% to 76% for community-dwelling participants (n = 13); 34.1% to 75.4% for NH plus community-dwelling participants (n = 2); and one study reported a prevalence rate for hospital participants of 44.8% (D’Onofrio et al., Reference D’Onofrio2012).

Asia

Participants in the 11 studies (20%) that originated from Asia included participants with AD (n = 7) and dementia (n = 4). The range of prevalence of agitation was reported as 23.3% to 78% in 10 studies, with two (17%) showing an agitation prevalence rate ≥50%. Four studies (33%) reported prevalence rates of at least one NPS, which ranged from 74.9% to 100%. Prevalence rates for agitation ranged from 23.3% to 63.1% for community-dwelling or outpatient participants (n = 7); 16.2% to 52.2% for NH plus community-dwelling participants (n = 3); and one study reported a prevalence rate for hospital participants of 52% for women and 78% for men (Kitamura et al., Reference Kitamura, Kitamura, Hino, Tanaka and Kurata2012).

North america

Participants in the 11 studies (20%) that originated from North America (nine in the United States [U.S.]) included participants with AD (n = 4), dementia (n = 4), the general geriatric population (n = 2), and participants with memory loss (n = 1). The range of prevalence of agitation was reported as 5% to 86% in 10 studies, with four (36%) showing an agitation prevalence rate ≥50%. Two studies (18%) reported prevalence rates of at least one NPS, which ranged from 50.9% to 89%. Prevalence rates for agitation ranged from: 6.9% to 86% for community-dwelling participants (n = 5), 50.4% for NH participants (n = 1), and 31% for NH plus community-dwelling participants (n = 1) (Orengo et al., Reference Orengo2008); three studies that did not report the source of their study sample reported a prevalence rate ranging from 5.3% to 40%.

Other countries

Participants in the three studies (5%) that originated from other countries (Australia, Tanzania, and Brazil) included participants with AD (n = 1) and dementia (n = 2). The range of reported prevalence of agitation/aggressiveness was 15.3% to 60.8%, with one study (33%) showing an agitation prevalence rate ≥50%. Two studies (67%) reported prevalence rates of at least one NPS, which ranged from 88.4% to 98%.

Natural progression of agitation/behavioral symptoms in AD

Seventeen studies that evaluated disease progression of agitation/behavioral symptoms in AD were identified. Studies presenting results on changes in severity of NPS or changes in prevalence rates over time were reviewed.

Of the 10 papers that evaluated changes in severity/frequency of agitation/NPS over time, six reported an increase (Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Connors, Xu, Woodward and Ames2015; Pan et al., Reference Pan2013; Selbaek et al., Reference Selbaek, Kirkevold and Engedal2008; Trzepacz et al., Reference Trzepacz2013; Vogel et al., Reference Vogel, Waldorff and Waldemar2015; Zahodne et al., Reference Zahodne, Ornstein, Cosentino, Devanand and Stern2015); one reported a decrease (Wolf-Ostermann et al., Reference Wolf-Ostermann, Worch, Fischer, Wulff and Graske2012); and one reported no change (Bergh et al., Reference Bergh, Engedal, Roen and Selbaek2011). Two studies had mixed results. Burgio and colleagues (Reference Burgio, Park, Hardin and Sun2007) reported little change in agitation over an 18-month period according to staff report; while direct observation showed a statistically significant (P value <0.05) trajectory of agitation with decreasing trend. In the study conducted by Fauth and colleagues (Reference Fauth, Zarit, Femia, Hofer and Stephens2006), using a mixed-model analyses, group-level analysis showed no change, while intra-individual results suggested an increase in prevalence of disruptive behavior. Evaluated timeframes ranged from 24 weeks to 6 years. The evidence suggests there is an increase in severity of agitation symptoms over time, although some studies provided mixed results.

Of the nine papers evaluating changes in prevalence of agitation/NPS over time, six reported an increase (Gonfrier et al., Reference Gonfrier, Andrieu, Renaud, Vellas and Robert2012; Lustenberger et al., Reference Lustenberger, Schupbach, von Gunten and Mosimann2011; Scarmeas et al., Reference Scarmeas2007; Selbaek et al., Reference Selbaek, Kirkevold and Engedal2008, Reference Selbaek, Engedal, Benth and Bergh2014; Wetzels et al., Reference Wetzels, Zuidema, de Jonghe, Verhey and Koopmans2010b); two reported no or little change (Bergh et al., Reference Bergh, Engedal, Roen and Selbaek2011; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell2009); and none reported a decrease. Of note, agitation persisted at most timepoints over 4 years in the study by Hendriks and colleagues (Reference Hendriks, Smalbrugge, Galindo-Garre, Hertogh and van der Steen2015) but decreased in the last week of life. Evaluated timeframes ranged from 1 to 14 years. The evidence suggests agitation/NPS becomes more prevalent over time.

The most common clinical outcome assessment (COA) used in the studies was the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). Of the studies that evaluated the change in overall NPS over time (n = 14), 11 used the NPI as the primary endpoint measure. Other measures used included the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI), the Disruptive Behavioral Symptoms measure (DBS), nurse or staff reports, direct observation, and the Columbia University Scale for Psychopathology in AD (CUSPAD). This variation in assessment methods can contribute to the variations in reported results.

Variations in natural progression by geographical region

Nearly half of the studies on natural progression were completed in Europe (n = 9/17); four studies were completed in the United States, one in Asia, and one in Australia, and two were a combined effort between Europe and the U.S. A greater percentage of European studies used a population sample of NH residents than U.S. studies (78% vs. 50%), and a greater percentage of U.S. studies used a population sample of community-dwelling residents than European studies (50% vs. 22%); the Asian study used a hospital population (Pan et al., Reference Pan2013) and the Australian study used a community-dwelling population (Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Connors, Xu, Woodward and Ames2015).

There were noteworthy differences in results of the course of agitation over time between the United States and Europe. More European studies showed an increase in agitation prevalence over time than U.S. studies (67% vs. 25%), and more U.S. studies showed little or no change in prevalence or frequency over time than European studies (50% vs. 11%). One European study indicated no change in agitation severity (Bergh et al., Reference Bergh, Engedal, Roen and Selbaek2011), and one study showed mixed results—the NPI total score decreased over time but all domains of the CMAI showed an increase in agitation over time (Wolf-Ostermann et al., Reference Wolf-Ostermann, Worch, Fischer, Wulff and Graske2012). Of the combined U.S./European studies, mixed results were reported; one showed an increase in disruptive behavioral symptoms over time (Scarmeas et al., Reference Scarmeas2007), and the other demonstrated that the prevalence of agitation worsened over time, but was not significant when adjusting for cognitive decline (Zahodne et al., Reference Zahodne, Ornstein, Cosentino, Devanand and Stern2015). Both the Asian and Australian studies showed an overall increase in NPS severity (Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Connors, Xu, Woodward and Ames2015; Pan et al., Reference Pan2013), although only one found increases in agitation outcomes specifically. (Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Connors, Xu, Woodward and Ames2015)

Disease severity and agitation/behavioral symptoms in AD

Thirty-four studies assessed some association between AD severity and NPS/agitation. Of these, 25 (74%) established an association between NPS or agitation and disease severity, four (12%) established a trend towards an association between the two without establishing statistical significance or testing for it, one study (3%) reported mixed results, and four studies (12%) reported no association between agitation/NPS and AD.

Results were examined separately for studies that explicitly noted assessment of agitation and those that assessed related NPS, but did not focus explicitly on agitation. Of the 34 studies that investigated the relationship between disease severity and NPS, 25 (74%) evaluated the relationship between agitation and disease severity, nine studies (26%) evaluated the relationship between NPS and disease severity, and six studies (18%) evaluated both agitation and overall NPS by disease severity.

Of the 25 studies that evaluated the relationship between agitation and disease severity, 17 (68%) demonstrated a significant association between the two, four studies (16%) showed a trending association (de Oliveira et al., Reference de Oliveira, Wajman, Bertolucci, Chen and Smith2015; Ismail et al., Reference Ismail, Dagerman, Tariot, Abbott, Kavanagh and Schneider2007; Karttunen et al., Reference Karttunen2011; Park et al., Reference Park2015), and four studies (Fernandez-Martinez et al., Reference Fernandez-Martinez, Molano, Castro and Zarranz2010; Kim and Lee, Reference Kim and Lee2014; Pinidbunjerdkool et al., Reference Pinidbunjerdkool, Saengwanitch and Sithinamsuwan2014; Treiber et al., Reference Treiber2008) (16%) demonstrated that there was no significant relationship between agitation and disease severity.

Of the 17 studies that showed a significant relationship between agitation and disease severity, 11 (65%) were cross-sectional and six (35%) were longitudinal. Dementia severity in these 17 studies was evaluated by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (n = 4) (Burgio et al., Reference Burgio, Park, Hardin and Sun2007; Hamuro et al., Reference Hamuro2007; Kasai et al., Reference Kasai, Meguro, Akanuma and Yamaguchi2015; O’Donnell et al., Reference O’Donnell, Lewis, Dubois, Standish, Bédard and Molloy2007), the Global Deterioration Scale (GDS) (n = 2) (Mulders et al., Reference Mulders, Fick, Bor, Verhey, Zuidema and Koopmans2016; Steinberg et al., Reference Steinberg2006), the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR; n = 4) (Helvik et al., Reference Helvik2016; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Lin and Liu2007; Selbaek et al., Reference Selbaek, Engedal, Benth and Bergh2014; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka2015), both the MMSE and CDR (n = 2) (D’Onofrio et al., Reference D’Onofrio2012; Peters et al., Reference Peters2015), or studies did not specify (n = 5). Of these 17 studies showing significant results, agitation was reported as being measured by the NPI in four studies (Fernandez Martinez et al., Reference Fernandez Martinez, Flores, De Las Heras, Lekumberri, Menocal and Imirizaldu2008; Helvik et al., Reference Helvik2016; Peters et al., Reference Peters2015; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka2015), the CMAI in two studies (Mulders et al., Reference Mulders, Fick, Bor, Verhey, Zuidema and Koopmans2016; Steinberg et al., Reference Steinberg2008), and Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale (BEHAVE-AD) in one (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Wang, Lin and Liu2007). Other studies either did not specify or used a study-unique definition of agitation (n = 10).

Of the 11 cross-sectional studies (n = 11/17) that reported a significant relationship between agitation and disease severity, three used the CDR to define dementia severity and one study showed agitation to be significantly predictive of the severity of cognitive impairment (moderate-severe dementia: CDR = 2–3 and MMSE score <18) in AD patients (D’Onofrio et al., Reference D’Onofrio2012). A second study, by Helvik and colleagues (Reference Helvik2016), showed that some CDR groups (defined as CDR <1: none; CDR = 1: mild; CDR = 2: moderate, CDR = 3: severe) were significantly associated with agitation. Tanaka and colleagues (Reference Tanaka2015) compared NPI agitation scores by CDR groups (mild, moderate, and severe classifications); the association was significant between agitation and all CDR groups (P value <0.001).

Six longitudinal studies demonstrated significant association between agitation and disease severity. One study reported disease severity using CDR scores (Selbaek et al., Reference Selbaek, Engedal, Benth and Bergh2014), showing that CDR scores of 2 (P value = 0.02) or 3 (P value <0.001) were significantly predictive of agitation. Another study compared GDS groups (defined as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7) against CMAI subdomains, demonstrating that agitation was significantly predictive of dementia severity in all CMAI subdomains (Steinberg et al., Reference Steinberg2008). A third study, by Morgan and colleagues (Reference Morgan, Sail, Snow, Davila, Fouladi and Kunik2013), communicated a significant association between agitation and dementia severity (r = –0.19, P value <0.001). Another study compared AD groups by mild, moderate, and severe AD, demonstrating that mild vs. moderate AD groups showed significantly significant differences in agitation levels (P value = 0.045) (Pink et al., Reference Pink2015). A study by Peters and colleagues (Reference Peters2015) demonstrated that agitation was significantly predictive of progression to severe dementia (hazard ratio: 2.946, P value = 0.004). Severe dementia was measured using the MMSE and CDR; severe AD was defined as an MMSE score of ≤10 or CDR score = 3. The sixth study reported that the severity of dementia increased the odds of agitation (odds ratio: 2.42, confidence interval: 1.81–3.23, P value < 0.01) (Steinberg et al., Reference Steinberg2006).

Papers investigating the association between AD severity and other NPS

Nine studies (n = 9/34) evaluated the relationship between NPS and disease severity, either using a total score for NPS or by evaluating the relationship by NPS type. Additionally, five studies that evaluated the relationship between agitation and disease severity also included results on other NPS, for a total of 14 studies. Of these 14 studies, 10 (Amoo et al., Reference Amoo2011; Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Connors, Xu, Woodward and Ames2015; Conde-Sala et al., Reference Conde-Sala2016; D’Onofrio et al., Reference D’Onofrio2012; Reference D’Onofrio2016; Karttunen et al., Reference Karttunen2011; Khoo et al., Reference Khoo, Chen, Ang and Yap2013; Koppitz et al., Reference Koppitz, Bosshard, Schuster, Hediger and Imhof2015; Spalletta et al., Reference Spalletta2010; Stella et al., Reference Stella, Laks, Govone, de Medeiros and Forlenza2016) demonstrated a statistically significant relationship between NPS and disease severity. Four (de Oliveira et al., Reference de Oliveira, Wajman, Bertolucci, Chen and Smith2015; Ismail et al., Reference Ismail, Dagerman, Tariot, Abbott, Kavanagh and Schneider2007; Karttunen et al., Reference Karttunen2011; Park et al., Reference Park2015) did not. Eight of the 10 statistically significant studies demonstrated significant associations between the degree of dementia severity and NPS, measured by total NPS score (Brodaty et al., Reference Brodaty, Connors, Xu, Woodward and Ames2015; Conde-Sala et al., Reference Conde-Sala2016; D’Onofrio et al., Reference D’Onofrio2012; Karttunen et al., Reference Karttunen2011; Khoo et al., Reference Khoo, Chen, Ang and Yap2013; Koppitz et al., Reference Koppitz, Bosshard, Schuster, Hediger and Imhof2015; Spalletta et al., Reference Spalletta2010; Stella et al., Reference Stella, Laks, Govone, de Medeiros and Forlenza2016). One study showed a significant relationship between specific NPS type and disease severity, including disinhibition and aberrant motor behavior (Amoo et al., Reference Amoo2011); another study, measuring both general and specific NPS, found a significant relationship between specific NPS type and disease severity, including irritability/lability and aberrant motor activity (D’Onofrio et al., Reference D’Onofrio2016).

Regional differences in associations of disease severity with agitation

Most studies evaluating the relationship between agitation/NPS and disease severity originated from Europe (n = 13/34); followed by North America (n = 9/34), Asia (n = 8/34), South America (n = 2/34), Africa (n = 1/34), and Australia (n = 1/34). Noteworthy regional differences included differences in population sample by region and residence of study population by region.

Studies originating in South America and Africa had the most studies that identified AD patients as their study population (100%), followed by Asia (63%, n = 5; Dementia = 12%, n = 1; Mixed = 25%, n = 2), Europe (38%, n = 5; Dementia = 38%, n = 5; Mixed = 23%, n = 3), and North America (22%, n = 2; Dementia = 44%, n = 5; Memory loss = 22%, n = 2).

The most common place of residence from which participants were drawn was community-dwelling residents, and the highest sample draw of community-dwelling residents came from South American studies (100%, n = 2), followed by Asian (63%, n = 5), North American (63%, n = 5), and European (46%, n = 6). NH resident study populations were more common in European (46%, n = 6) and North American studies (25%, n = 2) than Asian (22%, n = 2) or South American (0%, n = 0).

Significant findings associated with agitation/NPS and disease severity were found more often in studies originating in North America (89%, n = 8), followed by Europe (77%, n = 10), Asia (63%, n = 5), and South America (50%, n = 1). The single studies from Australia and Africa also reported significant association. Non-significant findings of this association were most common in Asia (22%, n = 2; trending findings 11%, n = 1), followed by European studies (8%, n = 1; trending findings 8%, n = 1). Two regions had no non-significant results, but had one study each with trending findings (South America n = 1, 50%; North America n = 1, 11%).

Mortality associated with agitation in AD

There were five studies that provided information on the association between agitation and mortality, and issues around death, which were included in the review (Table 4). The studies were from different settings, including nursing homes (n = 2), an outpatient clinic (n = 1), and mixed settings (n = 1); one setting was not reported.

Table 4. Studies on agitation and mortality

Abbreviations: AD = Alzheimer’s disease; AP = antipsychotic; BEHAVE-AD = Behavioral Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease Rating Scale; CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; LR = last-reported; NH = nursing home; NPI-A/A = Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Agitation/Aggression domain NPS = neuropsychiatric symptoms; NR = not reported; NS = not significant; OR = odds ratio; SD = standard deviation; UK = United Kingdom; US = United States.

Most studies provided estimates of association of agitation with mortality (n = 3). Two studies (Peters and colleagues, 2015; Sampson and colleagues, Reference Sampson2015) reported a significant association of agitation-related symptoms and mortality. Peters and colleagues (Reference Peters2015) reported results of a longitudinal population-based study, using data from 1995–2009, and reported that agitation is a significant predictor of death, controlling for age of dementia onset, gender, education level, general health rating, and apolipoprotein E epsilon 4 (APOE-ε4) genotype status. Results of a longitudinal cohort study of people with dementia admitted to an acute care hospital also reported significant association between severity of NPS and mortality. (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson2015) In a retrospective cohort study with NH AD patients, while reduction in behavioral symptoms as a result of treatment was associated with reduced risk of mortality, this association did not reach statistical significance. (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Wei, Moyo, Harris, Lucas and Simoni-Wastila2015)

The study by Koyama and colleagues (Reference Koyama, Fujise, Matsushita, Ishikawa, Hashimoto and Ikeda2015) did not directly assess the association between mortality and agitation in dementia patients. Instead, it provided information on the relationship between suicidal ideation of dementia patients and NPS. Ten percent of the dementia patients in the sample had suicidal thoughts. NPI-Agitation/Aggression (NPI-A/A) scores were statistically different for patients with and without suicidal thoughts (P value = 0.004)

The Vandervoort and colleagues (Reference Vandervoort2013) study investigated palliative quality of life in dementia patients. Patients that were included in this research were patients that had died in the previous 3 months. In the last month of life, pain, fear, anxiety, resistance to care, and agitation were the most frequently reported symptoms of dementia.

A few studies directly examined the association between agitation in dementia and mortality risk, and provided some evidence supporting a positive relationship. However, there is minimal research in this area. Further research exploring the relationship between dementia agitation and risk of death, and providing an understanding of the interaction of that relationship, would be beneficial.

Discussion

In this systematic review, a wide range of agitation prevalence rates were reported (5% to 88%), with rates varying somewhat by geographic region (lower ranges were reported for Asia). Most studies, however, reported prevalence rates that were under 50%. Few estimates were based on large samples. The years for which estimates were provided varied, patients from both outpatient and clinical settings were used, and many agitation assessments were used. These variations in study design make it difficult to provide a reliable estimate on the true prevalence rate of agitation symptoms in AD patients.

Seventeen studies reported on the natural progression of agitation/NPS in AD. Results suggested agitation severity ratings increase over time, while the proportion of patients with symptoms increase slightly or remain stable over time. While some geographic variations were detected in prevalence rates and the course of agitation and associations reported between AD severity and agitation, the heterogeneity of the included studies on multiple dimensions suggests that such differences should be examined tentatively and with caution.

The relationship between AD severity and agitation was evaluated in a substantial number of studies and was supported by most of them, providing one of the most robust findings of the review.

Overall, this review was broad in scope, and the results on agitation prevalence align with findings from earlier reviews that focused on prevalence and progression of NPS in patients with AD and/or dementia. Borsje and colleagues (Reference Borsje, Wetzels, Lucassen, Pot and Koopmans2015) conducted a systematic review of studies reporting the course of NPS in community-dwelling adults with dementia, including 23 studies in the data synthesis. Overall, the authors concluded that NPS are highly prevalent and persistent, but frequency parameters varied considerably across studies. Data on agitation was provided by nine of the included studies, and agitation was noted as one of the symptoms, with high prevalence an increasing trend over time. Reported point prevalence rates for wandering or agitation were 18% to 62%, while cumulative prevalence rate ranged between 40% to 100%. These wide ranges are consistent with the findings from our review. Another point of consistency for our review is the large number of NPS measures used for assessment of NPS, which was also noted in a review by Wetzels and colleagues (Reference Wetzels, Zuidema, de Jonghe, Verhey and Koopmans2010a); this review identified 12 measures used across 18 publications.

A separate review examined the prevalence and course of NPS in patients with dementia, including population-based studies, outpatient, and long-term patient populations (Bergh and Selbæk, Reference Bergh and Selbæk2012). Only studies using the NPI were reviewed; prevalence rates were examined for persons with dementia included in population-based studies, attending outpatient clinics, or living in long-term care facilities. Agitation was among the symptoms with the highest prevalence rates reported—a median of 27% for population-based studies and long-term care patients, and 37% for outpatients. The course of agitation was persistent for outpatient populations, while resolution rates were reported for long-term facilities. On the other hand, Wetzels and colleagues (Reference Wetzels, Zuidema, de Jonghe, Verhey and Koopmans2010a) reported increasing trends for agitation, suggesting that population setting may be an important variable to consider when the course of agitation is examined.

Van Der Linde and colleagues (Reference van der Linde, Stephan, Savva, Dening and Brayne2012) conducted a systematic review to give a broad overview of the prevalence, course, biological and psychosocial associations, care, and outcomes of behavioral and psychological symptoms in an older population with dementia. The authors examined 36 reviews, but none focused specifically on agitation in AD. Agitation was noted as one of the most prevalent symptoms identified by reviews in people with dementia. Consistent with our results, the authors noted that behavioral and psychological prevalence vary widely across reviews, but no specifics on agitation prevalence rates were provided.

Findings from our review are aligned with previously reported findings on agitation prevalence and natural progression. This review concluded that information is particularly scarce in areas including incidence rates of agitation and studies specifically examining the relationship between agitation symptoms and mortality. No U.S. study on incidence rates was identified. A possible reason for the low number of studies on incidence of agitation is the challenge of defining, measuring, and differentiating agitation incidence versus agitation prevalence for a symptom that is not constantly present. Finally, information from studies conducted with community-dwelling patients is relatively scarce.

The results of this systematic review suggest a need to clearly establish a unified understanding of the commonalities surrounding agitation in the context of AD, which should be built on a foundation of quality standardized methodology. Only by clearly understanding the incidence of agitation and its burden on AD patients can the medical community help identify the most appropriate treatment.

The key findings of this study need to be considered in the context of its limitations and study design. This systematic review was conceptualized as a broad review of information related to agitation burden for AD, and all study designs were accepted. In addition, a definition of agitation consistent with the IPA definition was used, including specific behaviors and related NPS; this could have possibly introduced some noise in the key findings as there is variability in how agitation is defined and measured in the literature. The target population was also broadly defined as patients with AD or dementia. These factors may contribute to the wide variability of papers included in the systematic review and lead to challenges in consistently summarizing and interpreting all information, in addition to bringing inherent variability in results.

This review summarized available evidence on incidence, prevalence, and course of agitation, as well as studies on the association of agitation with AD severity and mortality. Consistent with earlier reports, agitation is highly prevalent, but the course of the symptoms over time seems to depend on multiple factors. Evidence for the association of agitation with AD appears to be strong, as most studies identified reported significant association despite heterogeneity in measures and designs used. There is limited information on the specific association of agitation symptoms and mortality; lack of existing evidence suggests additional studies to better understand possible associations is warranted.

Conflict of interest

Ruth A. Duffy, Ross A. Baker, and Myrlene Sanon Aigbogun are employed by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Development and Commercialization, Inc. Ann Hartry and Lene Hammer-Helmich are employed by Lundbeck LLC. Milena Anatchkova, Anne Brooks, and Laura Swett are employed by Evidera, which provides consulting and other research services to pharmaceutical, medical device, and related organizations. In their salaried positions, they work with a variety of companies and organizations, and are precluded from receiving payment or honoraria directly from these organizations for services rendered. Evidera received funding from Otsuka and Lundbeck to participate in the study and the development of this manuscript.

All authors participated in study design, data analysis and interpretation, and contributed to the development of the manuscript. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Description of authors’ roles

M. Anatchkova participated in the study design, supervised data collection and analyses, and drafted the paper. L. Swett and A. Brooks supervised data collection, conducted data analysis, and prepared tables for the manuscript. M. Sanon Aigbogun and A. Hartry participated in the study design, protocol review, review of analyses, interpretation of findings, and review of the manuscript. R. Duffy, R. Baker, and L. Hammer-Helmich participated in the protocol review, review of analyses, interpretation of findings, and review of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Grossi of the Evidera Editorial and Design Services team for his assistance in editing and preparing the manuscript for submission.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610218001898.